Abstract

Background

C reactive protein (CRP) levels are suggested as serum biomarkers in the diagnosis and prognosis of psoriatic arthritis (PsA). However, increased CRP levels are found in less than 50% of PsA patients even in the presence of active disease.

Objectives

To evaluate the role of CRP levels in interventional clinical trials in PsA patients to better understand the trial generalisability, relationship with disease activity and predictive value for treatment response and decision making.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted via PubMed, Cochrane and Embase. We focused on phase III trials in PsA.

Results

Eight of 22 studies applied minimum baseline CRP levels for inclusion. Baseline CRP levels were wide-ranging (0.1–238 mg/L) and lower in studies without CRP in the enrolment criteria. All 22 studies used the American College of Rheumatology (ACR20) response and other endpoints that integrated CRP levels. One of seven studies that evaluated individual ACR-score components revealed a decrease in CRP levels along with improvement of other endpoints. Subanalyses show conflicting evidence on CRP levels as predictor of disease course.

Conclusion

CRP levels were inconsistently used as inclusion criterion in clinical trials, often limiting generalisability of the data. The use of composite scores such as ACR20 or Disease Activity Score-28-CRP is also limited since baseline levels of CRP affects their sensitivity to change. High CRP levels may be an individual predictor for disease progression and response to treatment, but the current conflicting findings and selective patient trial inclusions, do not allow CRP to play a very prominent role in treatment decision making.

Keywords: psoriatic arthritis, disease activity, biological therapy

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

C reactive protein (CRP) levels in patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) are not consistently elevated even in patients with clinically active disease.

Data from interventional clinical trials in PsA and other forms of chronic arthritis cannot always be translated directly into daily clinical practice.

CRP levels are easy to obtain in routine clinical practice across different forms of chronic arthritis, and are often incorporated in clinical decision making.

What does this study add?

We used a systematic approach towards documenting the role and impact of CRP in the pivotal clinical trials for new treatments in PsA.

CRP is regularly but not always used in the study inclusion criteria.

CRP does feature in the composite outcome measures for clinical trials in PsA suggesting potential issues with the generalisability of the data.

How might this impact on clinical practice or further developments?

While the use of CRP as a measure of disease activity or as an outcome measure in clinical trials and practice is not challenged, physicians and patients should remain aware of the associated limitations.

Phase III trials in PsA have strongly different inclusion criteria and may therefore be very difficult to compare, in particular with regard to generalisability.

Real-life data and extension of clinical trials into different subpopulations of PsA patients are suggested to ensure that all patients that will benefit from new therapies also can get access to the treatments.

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic inflammatory joint disease associated with the skin disorder psoriasis. PsA patients can present a wide spectrum of clinical phenotypes, including oligoarthritis, symmetrical polyarthritis, axial disease, specific inflammation of the distal interphalangeal joints and arthritis mutilans, dactylitis and enthesitis.1–5 Common non-musculoskeletal comorbidities of PsA are uveitis, bowel inflammation, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease.1 3–5

Current treatment options include conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), such as methotrexate, biological DMARDs (bDMARDs) such as antitumour necrosis factor, anti-interleukin (IL)12/23, anti-IL23 and anti-IL17, or targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs), such as Janus kinase inhibitors and phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors.6 7

There is no specific diagnostic test for PsA. Hence, a diagnosis is mainly made based on clinical presentation.1–5 8 Laboratory tests assessing inflammation and imaging can support the diagnostic process.1 3 5 Laboratory tests can also be considered useful to closely follow disease activity and support treatment decision making.1–3 5 9 Traditionally, non-specific markers of active inflammation such as elevated levels of C reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) are suggested as laboratory markers for PsA.1–3 5 9

However, increased CRP levels occur in less than 50% of PsA patients despite clinically active psoriatic disease with joint involvement.1–3 5 9 Yet, CRP is included in the most frequently used response criteria for PsA such as the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) response and the Disease Activity Score-28 with CRP (DAS28-CRP).2 7 10 These response criteria and disease activity measures have also found their way into clinical practice, for instance in treat-to-target algorithms or in third-party payers criteria to reimburse costs for bDMARD and tsDMARDs.

CRP is a readily performed routine laboratory test, which makes it a practical parameter to use. Accurate detection of CRP levels may be clinically relevant, given that CRP is one of the laboratory markers proposed as a predictor for clinical disease course and progression of structural damage.2 Joint damage is highly variable in PsA, but high CRP levels have a predictive value for worse disease outcomes.2–5 CRP levels can be measured with different methods.9 Traditional testing measures CRP levels within the range of 10 to 1000 mg/L.9 Recently, high-sensitivity assays (hs-CRP) have also been developed.9 These can measure lower levels of CRP with a sensitivity range of 0.1–10 mg/L.9 Hs-CRP is not determined routinely and is mostly used to predict the individual risk of cardiovascular disease.9

The objective of this study is to gain better insight into the importance of CRP levels as a laboratory marker for PsA in the context of key clinical trials for this disorder, and the potential impact thereof on daily clinical practice. The use of CRP levels in clinical trials testing new drugs for PsA may affect the generalisability of the trial data for the complete patient population, and inadvertedly limit access to drugs that patients need. We performed a systematic literature review to shed more light on the use of CRP in pivotal clinical trials for PsA, and discuss the potential impact on daily patient care.

Methods

For this systematic review, we concentrated specifically on data about CRP levels in published phase III studies for the treatment of PsA, using the databases PubMed, Cochrane Library and Embase. The following inclusion criteria were used for the initial literature search: phase III double-blind randomised controlled trial (RCT) as study design, patients with PsA as study population, CRP as inclusion and/or outcome parameter, text written in English and fully available online. Databases were scanned using the search terms (“Psoriatic arthritis” OR “arthritic psoriasis” OR “psoriatic arthritides” OR “psoriatic arthropathy”) AND (“CRP” OR “C-reactive protein”). Next, phase III clinical trials were selected. Abstracts, full texts, and referenced articles were not independently reviewed for relevance by two reviewers (CH and RL). Duplicates, unpublished trials, articles concerning open-label (extension phases of) studies, non-placebo-controlled (phases of) studies and irrelevant subanalyses were excluded. Relevant referenced articles, defined as studies that fulfilled our inclusion criteria, were added. All previously mentioned databases were last searched on 22 December 2020. The finally selected articles were subsequently mined for any data on CRP. Risk of bias was not assessed. The review was initiated as part of a Master’s degree in Medicine and was therefore registered on KU Leuven platform SCONE.

Results

Study identification and selection

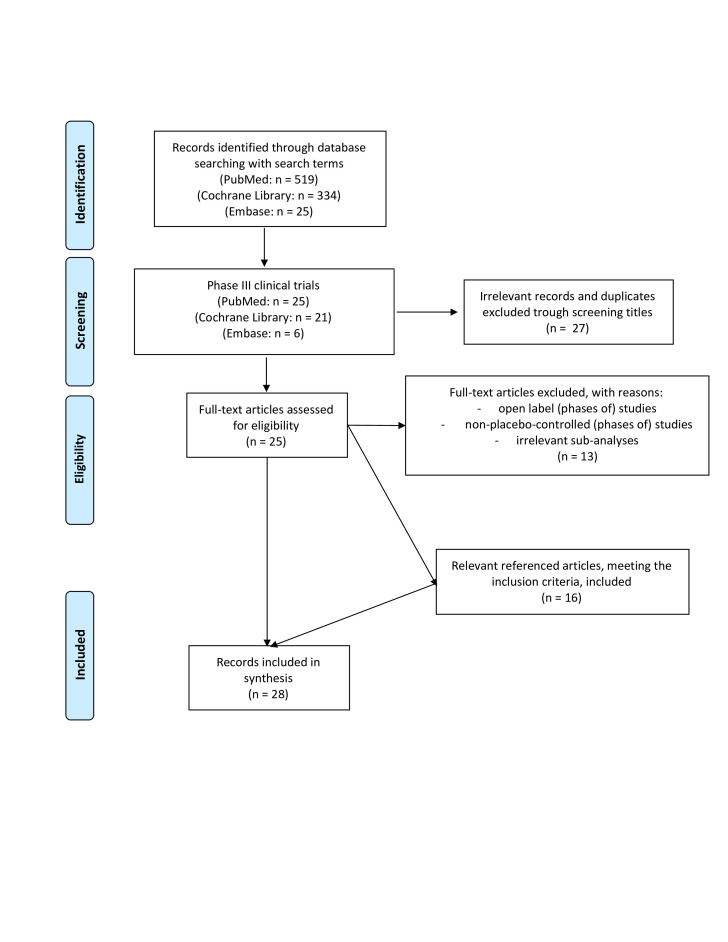

Twenty-eight papers reporting on 22 different trials and 6 subanalyses, conducted between 2002 and 2020, met our inclusion criteria and were selected for in-depth analysis.11–38 (figure 1, table 1). Taken together, more than 10 000 patients with PsA were studied in these phase III studies that involved 11 new interventions.11–38

Figure 1.

Flow diagram: study identification and selection.

Table 1.

Studies included in the data review and analysis

| Study acronym | Study period | Study size | Interventions compared | Primary endpoint | |

| Infliximab bDMARD TNFα inhibitor |

IMPACT211 12* | 2002–2004 | 200 | Infliximab Placebo | ACR20 response at week 14 and 24 |

| Golimumab bDMARD TNFα inhibitor |

GO-REVEAL13 | 2005–2012 | 405 | Golimumab Placebo | ACR 20 response at week 14, change in SvH score at week 24 |

| Adalimumab bDMARD TNFα inhibitor |

ADEPT14 15 | 2003–2004 | 315 | Adalimumab Placebo | ACR 20 response at week 12, change in mTSS at week 24 |

| SPIRIT-P116* | 2012–2017 | 417 | Adalimumab Ixekizumab Placebo | ACR20 response at week 24 | |

| OPAL BROADEN17 18 | 2014–2015 | 422 | Tofacitinib Adalimumab Placebo | ACR20 response and HAQ DI at months 3 and 12 | |

| Certolizumab pegol bDMARD TNFα inhibitor |

RAPID-PsA19 20* | 2010–2011 | 409 | Certolizumab pegol Placebo | ACR20 response at week 12, mTSS at week 24 |

| Ixekizumab bDMARD IL-17A inhibitor |

SPIRIT-P116* | 2012–2017 | 417 | Adalimumab Ixekizumab Placebo | ACR20 response at week 24 |

| Secukinumab bDMARD IL-17A inhibitor |

FUTURE 121 | 2011–2014 | 606 | Secukinumab Placebo | ACR20 response at week 24 |

| FUTURE 222 | 2013–2019 | 397 | Secukinumab Placebo | ACR20 response at week 24 | |

| FUTURE 323 | 2014–2018 | 414 | Secukinumab Placebo | ACR20 response at week 24 | |

| FUTURE 424 | 2015–2017 | 341 | Secukinumab Placebo | ACR20 response at week 16 | |

| FUTURE 525 | 2015–2019 | 996 | Secukinumab Placebo | ACR20 response at week 16 | |

| Ustekinumab bDMARD IL-12/23 inhibitor |

PSUMMIT126 27* | 2009–2013 | 615 | Ustekinumab Placebo | ACR20 response at week 24 |

| PSUMMIT 227 28* | 2010–2012 | 312 | Ustekinumab Placebo | ACR20 response at week 24 | |

| Guselkumab bDMARD IL-23 inhibitor |

DISCOVER 129* | 2017–2019 | 381 | Guselkumab Placebo | ACR20 response at week 24 |

| DISCOVER 230* | 2017–2020 | 741 | Guselkumab Placebo | ACR20 response at week 24 | |

| Abatacept bDMARD T-cell modulator |

ASTRAEA31 32 | 2013–2020 | 424 | Abatacept Placebo | ACR20 response at week 24 |

| Tofacitinib tsDMARD JAK inhibitor |

OPAL BROADEN17 18 | 2014–2015 | 422 | Tofacitinib Adalimumab Placebo | ACR20 response and HAQ-DI at month 3 and month 12 |

| OPAL BEYOND33 | 2013–2016 | 395 | Tofacitinib Placebo | ACR20 response and HAQ-DI at month 3 and month 6 | |

| Apremilast tsDMARD PDE4 inhibitor |

PALACE 134 | 2010–2016 | 504 | Apremilast Placebo | ACR20 response modified for PsA at week 16 |

| PALACE 235 | 2010–2017 | 484 | Apremilast Placebo | ACR20 response modified for PsA at week 16 | |

| PALACE 336 | 2010–2017 | 505 | Apremilast Placebo | ACR20 response modified for PsA at week 16 | |

| PALACE 437 | 2010–2017 | 527 | Apremilast Placebo | ACR20 response modified for PsA at week 16 | |

| ACTIVE38* | 2013–2016 | 219 | Apremilast Placebo | ACR20 response at week 16 and 24 |

PASI: Psoriasis Area and Severity Index - BSA: Body Surface Area

*Studies using a minimum level of baseline CRP as inclusion criterion (table 2).

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; bDMARD, biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; CRP, C reactive protein; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index; IL, interleukin; JAK, Janus kinase; mTSS, modified Total Sharp/van der Heijde score; PDE4, phosphodiesterase-4; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; SvH score, Sharp/van der Heijde score; TNFα, tumour necrosis factor α; tsDMARD, targeted synthetic DMARD.

CRP as inclusion criterium

Eight of the 22 studies used a minimum level of baseline CRP as an inclusion criterion.11 16 19 26 28–30 38 Levels of CRP were used as a parameter to define active disease, combined with the swollen and tender joint count ranging between 3 and 5. To facilitate comparisons, we converted all values found for this review into the same unit of measurement (mg/L). The eight studies used different cut-off points (table 2). In the other 14 studies, active joint disease was only defined as ≥3 tender joints and ≥3 swollen joints.13 14 17 21–25 31 33–37

Table 2.

Baseline CRP levels in the different studies

| Study acronym | Study group | Baseline CRP (mg/L) | CRP inclusion criteria | |

| IMPACT 211 | Infliximab | Mean 19 | SD 24 | Either CRP ≥15 mg/L and/or morning stiffness ≥45 min |

| Placebo | Mean 23 | SD 34 | ||

| GO-REVEAL13 | Golimumab 50 mg | Mean 13 | SD 16 | / |

| Golimumab 100 mg | Mean 14 | SD 18 | ||

| Placebo | Mean 13 | SD 16 | ||

| ADEPT14 | Adalimumab | Mean 14 | SD 21 | / |

| Placebo | Mean 14 | SD 17 | ||

| SPIRIT-P116 | Adalimumab | Mean 13.2 | SD 19.1 | Either ≥1 PsA-related hand or foot joint erosion on centrally read X-rays or CRP >6 mg/L |

| Ixekizumab every 2 weeks | Mean 15.1 | SD 25.9 | ||

| Ixekizumab every 4 weeks | Mean 12.8 | SD 16.4 | ||

| Placebo | Mean 15.1 | SD 23.6 | ||

| OPAL BROADEN17 | Tofacitinib 5 mg | Median 4.8 | Range 0.2–115 | / |

| Tofacitinib 10 mg | Median 5.1 | Range 0.2–92.9 | ||

| Adalimumab | Median 4.3 | Range 0.2–131.0 | ||

| Placebo | Median 5.0 | Range 0.2–113.0 | ||

| RAPID-PsA19 | Certolizumab every 2 weeks | Median 7.0 | Min 0.2 – Max 238.0 | Either ESR ≥28 mm/hour or CRP >7.9 mg/L |

| Certolizumab every 4 weeks | Median 8.7 | Min 0.1 – Max 131.0 | ||

| PSUMMIT 126 | Ustekinumab 45 mg | Median 10.0 | IQR 5.9–21.1 | CRP ≥3 mg/L |

| Ustekinumab 90 mg | Median 12.3 | IQR 6.5–21.7 | ||

| Placebo | Median 9.6 | IQR 6.0–18.6 | ||

| PSUMMIT 228 | Ustekinumab 45 mg | Median 13.0 | IQR 4.5–36.3 | Screening CRP ≥6 mg/L, modified to ≥3 mg/L after study start |

| Ustekinumab 90 mg | Median 10.1 | IQR 4.8–19.8 | ||

| Placebo | Median 8.5 | IQR 4.6–22.0 | ||

| DISCOVER 129 | Guselkumab every 4 weeks | Median 6 | IQR 3–13 | CRP ≥3 mg/L |

| Guselkumab every 8 weeks | Median 7 | IQR 4–19 | ||

| Placebo | Median 8 | IQR 3–15 | ||

| DISCOVER 230 | Guselkumab every 4 weeks | Median 12 | IQR 6–23 | CRP ≥6 mg/L |

| Guselkumab every 8 weeks | Median 13 | IQR 7–25 | ||

| Placebo | Median 12 | IQR 2–26 | ||

| ASTRAEA31 | Abatacept | Mean 14.0 | SD 20.9 | / |

| Placebo | Mean 14.3 | SD 30.3 | ||

| OPAL BEYOND33 | Tofacitinib 5 mg | Median 5.7 | Range 0.2–126.0 | / |

| Tofacitinib 10 mg | Median 4.9 | Range 0.2–163.0 | ||

| Placebo | Median 4.4 | Range 0.2–164.0 | ||

| PALACE 134 | Apremilast 20 mg | Mean 9.0 | SD 14.09 | / |

| Apremilast 30 mg | Mean 8.4 | SD 10.24 | ||

| Placebo | Mean 11 | SD 14.36 | ||

| PALACE 336 | Apremilast 20 mg | Mean 9.7 | SD 15.1 | / |

| Apremilast 30 mg | Mean 11.5 | SD 18.8 | ||

| Placebo | Mean 10 | SD 13.5 | ||

| PALACE 437 | Apremilast 20 mg | Mean 9 | SD 11 | / |

| Apremilast 30 mg | Mean 8 | SD 11 | ||

| Placebo | Mean 11 | SD 27 | ||

| ACTIVE38 | Apremilast 30 mg | Mean 14.4 | SD 16 | CRP ≥2 mg/L |

| Placebo | Mean 12.5 | SD16 | ||

CRP, C reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; max, maximum; PsA, psoriatic arthritis.

The differences in the use of CRP levels in the trial inclusion criteria have several implications. For the PSUMMIT trial, 559 of 1774 patients who were screened were not randomised, mostly because they did not meet the inclusion criteria of both ≥5 tender and ≥5 swollen joints and CRP ≥3 mg/L.26 Among 624 patients screened for the DISCOVER 1 trial, 241 did not meet the study entrance criteria, most commonly (135 of 241) because their baseline CRP was less than 3 mg/L.29 A similar situation arose while collecting patients for the DISCOVER 2 trial.30 Out of 1153 patients screened, 412 were not eligible, of whom 272 for having serum CRP levels lower than 6 mg/L.30

CRP levels at baseline

Baseline CRP levels were described in 16 of the 22 studies.11 13 14 16 17 19 26 28–31 33 34 36–38 (table 2) CRP levels were perceived in three different ways: as median CRP, mean CRP and as percentage of patients with elevated CRP levels.11 13 14 16 17 19 26 28–31 33 34 36–38 Regardless of the way of perceiving CRP levels, none of the 16 studies reported a significant difference in baseline CRP levels between their treatment groups.11 13 14 16 17 19 26 28–31 33 34 36–38

Nine out of 16 studies reported mean CRP levels at baseline, 3 out of these 9 studies used a minimum level of baseline CRP as inclusion criterion.11 13 14 16 31 34 36–38 Mean baseline CRP tended to be higher in studies who used CRP as inclusion criterion, ranging from 12.5 mg/L to 23 mg/L, in comparison to studies who didn’t, with mean baseline CRP ranging from 8.4 mg/L to 14.3 mg/L.11 13 14 16 31 34 36–38

Seven out of 16 studies used median baseline CRP levels instead of mean baseline CRP values, 4 out of these 7 studies used a minimum level of baseline CRP as inclusion criterion.17 19 26 28 30 33 Median baseline CRP tended to be higher in those studies that used CRP as an inclusion criterion, ranging from 7.0 mg/L to 13.0 mg/L, in comparison to studies that did not, with median baseline CRP ranging from 4.3 mg/L to 8 mg/L.17 19 26 28 30 33 None of the studies that used median baseline CRP levels mentioned the reason why they used they used median instead of mean baseline CRP.17 19 26 28 30 33 One possible reason is that they anticipated a non-parametric distribution. Since none of the 16 studies reported both mean and median baseline CRP levels, this could not be compared.11 13 14 16 17 19 26 28–31 33 34 36–38

Thus, 8 of 16 studies in total used a minimum level of baseline CRP as an inclusion criterion.11 16 19 26 28–30 38 CRP levels at baseline tended to be remarkably lower in studies without enrolment requirement criteria for CRP than in studies including CRP elevation within the inclusion criteria.34

The wide range of CRP values, ranging from 0.1 mg/L up to 238 mg/L, highlights the heterogeneity of systemic inflammation in patients with PsA.19

Furthermore, three clinical trials reported on the percentage of patients with elevated CRP levels within different treatment groups.17 31 33 The OPAL BROADEN trial defined elevated hs-CRP as >2.87 mg/L, with elevated hs-CRP in 64%, 63%, 60%, and 60% in the tofacitinib 5 mg, tofacitinib 10 mg, adalimumab and placebo groups, respectively.17 In the OPAL BEYOND trial, elevated hs-CRP was also defined as >2.87 mg/L with 65%, 62%, and 61% in the tofacitinib 5 mg, tofacitinib 10 mg and placebo group, respectively.33 Third, in the ASTRAEA trial, elevated CRP was similarly defined as >3 mg/L, with 68.9% and 62.7% in the abatacept and placebo group, respectively.31 These findings support the previous statement that CRP levels are by no means elevated in all patients with active PsA.

Of note, the different studies did not apply a consistent cut-off for the so-called normal CRP range with values from ≤2.87 mg/L (ADEPT, OPAL BROADEN, OPAL BEYOND), ≤3 mg/L (ASTRAEA), <5 mg/L (PALACE 1, 2 and 3), ≤7.9 mg/L (RAPID-PsA), to ≤10 mg/L (PSUMMIT 1 and 2).14 17 19 26 28 32 33 35–37

CRP as a component of the composite score: DAS28-CRP at baseline

In the six studies that did not assess CRP individually as baseline characteristic, DAS28-CRP was evaluated instead.21–25 35 (table 3) The DAS28-CRP combines a tender joint count based on a 28-joint assessment, swollen joint count based on a 28-joint assessment, in addition to the general health patient global Visual Analogue Scale (VAS in mm) domains and CRP (in mg/L).39 In total, 14 of the 22 studies evaluated baseline DAS28-CRP.13 17 21–26 28 31 33–36 Only 2 out of those 14 studies used a minimum baseline CRP level as an inclusion criterion and these 2 reported median baseline DAS28-CRP, in contrast to the other 12 studies that reported mean baseline DAS28-CRP.13 17 21–26 28 31 33–36 This makes it difficult to draw a conclusion about the correlation between the use of CRP as inclusion criteria and baseline DAS28-CRP score. The median baseline DAS28-CRP in studies that used CRP as an inclusion criterion tended to be higher, ranging from 5.2 to 5.6, than the mean baseline DAS28-CRP in studies that did not use CRP as an inclusion criterion, ranging from 4.4 to 5.0.13 17 21–26 28 31 33–36 None of the 22 studies used a minimum DAS28-CRP value as an inclusion criterion.11 13 14 16 17 19 21–26 28–31 33–38

Table 3.

Baseline DAS28-CRP

| Study acronym | Study group | Baseline DAS28-CRP* | |

| GO-REVEAL13 | Golimumab 50 mg | Mean 5.0 | SD 1.1 |

| Golimumab 100 mg | Mean 4.9 | SD 1.1 | |

| Placebo | Mean 4.9 | SD 1.0 | |

| OPAL BROADEN17 | Tofacitinib 5 mg | Mean 4.6 | SD 0.9 |

| Tofacitinib 10 mg | Mean 4.5 | SD 1.0 | |

| Adalimumab | Mean 4.4 | SD 1.0 | |

| Placebo | Mean 4.5 | SD 1.0 | |

| FUTURE 121 | Secukinumab 150 mg | Mean 4.8 | SD 1.1 |

| Secukinumab 75 mg | Mean 4.9 | SD 1.2 | |

| Placebo | Mean 4.9 | SD 1.1 | |

| FUTURE 222 | Secukinumab 300 mg | Mean 4.8 | SD 1.0 |

| Secukinumab 150 mg | Mean 4.9 | SD 1.1 | |

| Secukinumab 75 mg | Mean 4.7 | SD 1.0 | |

| Placebo | Mean 4.7 | SD 1.0 | |

| FUTURE 323 | Secukinumab 300 mg | Mean 4.5 | SD 1.0 |

| Secukinumab 150 mg | Mean 4.6 | SD 1.1 | |

| Placebo | Mean 4.7 | SD 1.1 | |

| FUTURE 424 | Secukinumab 150 mg with loading regimen | Mean 4.5 | SD 1.0 |

| Secukinumab 150 mg without loading regimen | Mean 4.5 | SD 1.1 | |

| Placebo | Mean 4.6 | SD 1.0 | |

| FUTURE 525 | Secukinumab 300 mg | Mean 4.5 | SD 1.0 |

| Secukinumab 150 mg with loading dose | Mean 4.7 | SD 1.0 | |

| Secukinumab 150 mg without loading dose | Mean 4.6 | SD 1.1 | |

| Placebo | Mean 4.6 | SD 1.1 | |

| PSUMMIT 126 | Ustekinumab 45 mg | Median 5.2 | IQR 4.6–5.7 |

| Ustekinumab 90 mg | Median 5.2 | IQR 4.6–5.8 | |

| Placebo | Median 5.2 | IQR 4.4–6.0 | |

| PSUMMIT 228 | Ustekinumab 45 mg | Median 5.6 | IQR 4.9–6.3 |

| Ustekinumab 90 mg | Median 5.3 | IQR 4.7–6.0 | |

| Placebo | Median 5.2 | IQR 4.4–5.9 | |

| ASTRAEA31 | Abatacept | Mean 5.0 | SD 1.1 |

| Placebo | Mean 4.9 | SD 1.1 | |

| OPAL BEYOND33 | Tofacitinib 5 mg | Mean 4.5 | SD 1.0 |

| Tofacitinib 10 mg | Mean 4.7 | SD 1.2 | |

| Placebo | Mean 4.4 | SD 1.0 | |

| PALACE 134 | Apremilast 20 mg | Mean 4.8 | SD 1.1 |

| Apremilast 30 mg | Mean 4.9 | SD 1.0 | |

| Placebo | Mean 4.9 | SD 1.0 | |

| PALACE 235 | Apremilast 20 mg | Mean 4.6 | SD 1.0 |

| Apremilast 30 mg | Mean 4.7 | SD 1.0 | |

| Apremilast 30 mg | Mean 4.5 | SD 1.1 | |

| PALACE 336 | Apremilast 20 mg | Mean 4.6 | SD 1.1 |

| Apremilast 30 mg | Mean 4.6 | SD 1.0 | |

| Placebo | Mean 4.5 | SD 1.1 | |

| PALACE 437 | Apremilast 20 mg | Mean 4.7 | SD 1.1 |

| Apremilast 30 mg | Mean 4.5 | SD 1.0 | |

| Placebo | Mean 4.6 | SD 1.1 | |

*The DAS28-CRP combines a tender joint count based on a 28-joint assessment, swollen joint count based on a 28-joint assessment, in addition to the general health patient global Visual Analogue Scale (in mm) domains and CRP (in mg/L).40

DAS28-CRP, Disease Activity Score 28 using C reactive protein.

CRP as a component of the composite score as responder tool

Different composite scores including CRP were used in the different studies as responder tools: ACR response score and DAS28-CRP. ACR20 is mandatory as a primary outcome, while ACR50 and ACR70 are usually secondary outcomes.

ACR20 was the primary endpoint for all 22 studies, in which CRP levels are integrated.11 13 14 16 17 19 21–26 28–31 33–38 (tables 1 and 4) The ACR20 response criteria require ≥20% improvement in both total joint counts and swollen joint counts, as well as a 20% improvement in 3 of the following five items: patient and physician global assessments of disease activity (VAS), physician global assessment (VAS), patient-reported pain score (VAS), Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ), and either ESR or CRP.10 To achieve an ACR50 or ACR70, the level of response should be 50% or 70% improvement, respectively.10 Additionally radiographic progression according to change in modified Sharp/van der Heijde score and the HAQ Disability Index (HAQ DI) were used as coprimary endpoints in some studies13 14 17 19 33 (table 1).

Table 4.

Study endpoints: ACR20 response—DAS28-CRP—MDA

| Study acronym | Study group | Timing of evaluation | ACR20 response* | DAS28-CRP† (mean change, unless otherwise stated) |

MDA‡ |

| IMPACT 2 §11 | Infliximab | Week 14 | 58% | / | / |

| Week 24 | 54% | / | / | ||

| Placebo | Week 14 | 11% | / | / | |

| Week 24 | 16% | / | / | ||

| GO-REVEAL13 | Golimumab 50 mg | Week 14 | 51% | −1.38 | / |

| Week 24 | 52% | −1.43 | / | ||

| Golimumab 100 mg | Week 14 | 45% | −1.29 | / | |

| Week 24 | 61% | −1.56 | / | ||

| Placebo | Week 14 | 9% | −0.18 | / | |

| Week 24 | 12% | −0.12 | / | ||

| ADEPT14 | Adalimumab 40 mg every 2 weeks | Week 12 | 58% | / | / |

| Week 24 | 57% | / | / | ||

| Placebo | Week 12 | 14% | / | / | |

| Week 24 | 15% | / | / | ||

| SPIRIT-P1 ¶16 | Adalimumab 40 mg every 2 weeks | Week 24 | 57.4% | −1.74 | / |

| Ixekizumab every 2 weeks | Week 24 | 62.1% | −2.04 | / | |

| Ixekizumab every 4 weeks | Week 24 | 57.9% | −1.96 | / | |

| Placebo | Week 24 | 30.2% | −0.84 | / | |

| OPAL BROADEN17 | Tofacitinib 5 mg | Month 3 | 50% | −1.3 | 26% |

| Month 12 | 68% | −1.9 | 37% | ||

| Tofacitinib 10 mg | Month 3 | 61% | −1.6 | 26% | |

| Month 12 | 70% | −2.0 | 43% | ||

| Adalimumab 40 mg every 2 weeks | Month 3 | 52% | −1.5 | 25% | |

| Month 12 | 60% | −1.9 | 40% | ||

| Placebo | Month 3 | 33% | −0.8 | 7% | |

| Month 12 | 58% | −2.0 | 34% | ||

| RAPID-PsA °°19 | Certolizumab pegol every 2 weeks | Week 12 | 58% | / | / |

| Week 24 | 63.8% | / | 33.3% | ||

| Certolizumab pegol every 4 weeks | Week 12 | 51.9% | / | / | |

| Week 24 | 56.3% | / | 34.1% | ||

| Placebo | Week 12 | 24.3% | / | / | |

| Week 24 | 23.5% | / | 5.9% | ||

| FUTURE 121 | Secukinumab 150 mg | Week 24 | 50% | −1.62 | / |

| Secukinumab 75 mg | Week 24 | 50.5% | −1.67 | / | |

| Placebo | Week 24 | 17.3% | −0.77 | / | |

| FUTURE 222 | Secukinumab 300 mg | Week 24 | 54% | −1.61 | / |

| Secukinumab 150 mg | Week 24 | 51% | −1.58 | / | |

| Secukinumab 75 mg | Week 24 | 29% | −1.12 | / | |

| Placebo | Week 24 | 15% | −0.96 | / | |

| FUTURE 323 | Secukinumab 300 mg | Week 24 | 48.2% | −1.56 | / |

| Secukinumab 150 mg | Week 24 | 42% | −1.24 | / | |

| Placebo | Week 24 | 16.1% | −0.64 | / | |

| FUTURE 424 | Secukinumab 150 mg with loading regimen | Week 16 | 41.2% | −0.98 | / |

| Secukinumab 150 mg without loading regimen | Week 16 | 39.8% | −0.84 | / | |

| Placebo | Week 16 | 18.4% | −0.21 | / | |

| FUTURE 525 | Secukinumab 300 mg | Week 16 | 62.6% | −1.49 | / |

| Secukinumab 150 mg with loading dose | Week 16 | 55.5% | −1.29 | 14% | |

| Secukinumab 150 mg without loading dose | Week 16 | 59.5% | −1.29 | 10.6% | |

| Placebo | Week 16 | 27.4% | −0.63 | 2.6% | |

| PSUMMIT 1§26 | Ustekinumab 45 mg | Week 24 | 42.4% | 65.9% EULAR response** | / |

| Ustekinumab 90 mg | Week 24 | 49.5% | 67.6% EULAR response** | / | |

| Placebo | Week 24 | 22.8% | 34.5% EULAR response** | / | |

| PSUMMIT 2§28 | Ustekinumab 45 mg | Week 24 | 43.7% | 54.4% EULAR response** | / |

| Ustekinumab 90 mg | Week 24 | 43.8% | 53.3% EULAR response** | / | |

| Placebo | Week 24 | 20.2% | 29.8% EULAR response** | / | |

| DISCOVER 1 §29 | Guselkumab every 4 weeks | Week 24 | 59% | −1.61 | 30% |

| Guselkumab every 8 weeks | Week 24 | 52% | −1.43 | 23% | |

| Placebo | Week 24 | 52% | −0.70 | 11% | |

| DISCOVER 2¶30 | Guselkumab every 4 weeks | Week 24 | 64% | −1.62 | 19% |

| Guselkumab every 8 weeks | Week 24 | 64% | −1.59 | 25% | |

| Placebo | Week 24 | 33% | −0.97 | 6% | |

| ASTRAEA31 | Abatacept | Week 24 | 39.4% | / | 11.7% |

| Placebo | Week 24 | 22.3% | / | 8.1% | |

| OPAL BEYOND33 | Tofacitinib 5 mg | Month 3 | 50% | −1.4 | 22.9% |

| Month 6 | 60% | −1.6 | 23.7% | ||

| Tofacitinib 10 mg | Month 3 | 47% | −1.2 | 21.2% | |

| Month 6 | 49% | −1.4 | 23.5% | ||

| Placebo | Month 3 | 24% | −0.6 | 14.5% | |

| Month 6 | 51.9% | −1.5 | 18.2% | ||

| PALACE 134 | Apremilast 20 mg two times per day | Week 16 | 30.4% | / | / |

| Week 24 | 26.4% | −0.66 | / | ||

| Apremilast 30 mg two times per day | Week 16 | 38.1% | / | / | |

| Week 24 | 36.6% | −0.91 | / | ||

| Placebo | Week 16 | 19.0% | / | / | |

| Week 24 | 13.3% | −0.20 | / | ||

| PALACE 235 | Apremilast 20 mg two times per day | Week 16 | 37.4% | −0.8 | / |

| Week 52 | 52.9%% | −1.1 | / | ||

| Apremilast 30 mg two times per day | Week 16 | 32.1% | −0.7 | / | |

| Week 52 | 52.6% | −1.3 | / | ||

| Placebo | Week 16 | 18.9% | −0.3 | / | |

| Week 52 | 50.4% | −1.2 | / | ||

| PALACE 336 | Apremilast 20 mg two times per day | Week 16 | 28% | −0.57 | / |

| Week 52 | 56% | −1.2 | / | ||

| Apremilast 30 mg two times per day | Week 16 | 41% | −0.77 | / | |

| Week 52 | 63% | −1.4 | / | ||

| Placebo | Week 16 | 18% | −0.28 | / | |

| Week 52 | 58.5% | −1.3 | / | ||

| PALACE 437 | Apremilast 20 mg two times per day | Week 16 | 28.0% | −0.62 | / |

| Week 52 | 53.4% | −1.4 | / | ||

| Apremilast 30 mg two times per day | Week 16 | 30.7% | −0.67 | / | |

| Week 52 | 58.7% | −1.4 | / | ||

| Placebo | Week 16 | 15.9% | −0.16 | / | |

| Week 52 | 58.2% | −1.2 | / | ||

| ACTIVE §38 | Apremilast 30 mg two times per day | Week 16 | 38.2% | −1.07 | / |

| Week 24 | 43.6% | −1.26 | / | ||

| Placebo | Week 16 | 20.2% | −0.39 | / | |

| Week 24 | 24.8% | −0.76 | / |

*Composite measure defined as both improvement of 20% in the number of tender and number of swollen joints, and a 20% improvement in three of the following five criteria: patient global assessment, physician global assessment, functional ability measure (most often Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ)), Visual Analogue Pain Scale and erythrocyte sedimentation rate or CRP.

†The DAS28-CRP combines a tender joint count based on a 28-joint assessment, swollen joint count based on a 28-joint assessment, in addition to the general health patient global Visual Analogue Scale (VAS in mm) domains and CRP (in mg/L).

‡A good or moderate EULAR DAS28-CRP response.

§Studies using a minimum level of baseline CRP as inclusion criterion, also including a radiographic outcome measure.39 40

¶Studies using a minimum level of baseline CRP as inclusion criterion (table 2).

**A patient is classified as achieving MDA when fulfilling at least five of the following seven criteria: tender joint count 1 or less, swollen joint count 1 or less, PASI score 1 or less or BSA 3 or less, patient pain VAS score 15 or less, patient global disease activity VAS score 20 or less, HAQ-Disability Index score 0.5 or less and tender entheseal points 1 or less.

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; CRP, C reactive protein; DAS-28, Disease Activity Score-28; MDA, minimal disease activity; SPIRIT, Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials.

In 7 out of 22 studies the individual components of the ACR criteria were evaluated as secondary endpoints, of whom only the IMPACT 2 trial could reveal a significant decrease in CRP levels along with significant improvement of other endpoints.11 17 33–37 This could be explained by the fact that the IMPACT 2 trial is the only one out of those seven studies with CRP enrolment requirement criteria and higher baseline CRP levels.11 17 33–37

CRP levels were also integrated into other generally used main secondary endpoints such as ACR50, ACR70 and DAS28-CRP. (table 4)

None of the studies reported remission as secondary outcome. Seven studies reported Minimal Disease Activity (MDA) as a secondary outcome.17 19 25 29–31 33 40 (table 4)

CRP as a predictor of therapy response

Given the heterogeneity in the timing of endpoint evaluations, the choice of secondary endpoints and the influence of the treatment itself, it is difficult to evaluate the impact of the use of CRP levels in the trial inclusion criteria on the response to therapy and the achievement of important treatment targets.

The ADEPT trial and Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) P1 trial both had a treatment group that received adalimumab 40 mg every 2 weeks.14 16 These treatment groups both had a similar ACR20 response at week 24, respectively in 57% and 57.4% of patients, despite the fact that inclusion in the SPIRIT P1 trial required either ≥1 PsA-related hand or foot joint erosion on centrally read X-rays or CRP >6 mg/L.14 16 Mean baseline CRP was 13.2 mg/L in the previously mentioned ADEPT treatment group, baseline CRP levels were not reported in the SPIRIT P1 trial.14 16

The ACTIVE trial and PALACE 1, 2, 3 and 4 trials, all had a treatment group that received apremilast 30 mg two times per day.34–38 In the ACTIVE trial, which used a limit of CRP ≥2 mg/L, 38.2% of patients of this treatment group had an ACR20 response at week 16.38 In the PALACE 1, 2, 3 and 4 trials, which did not use a minimum value for CRP, respectively 38.1%, 32.1%, 41% and 30.7% of patients had an ACR20 response within the same treatment group.34–37 Mean baseline CRP was 14.4 mg/L in the previously mentioned ACTIVE treatment group, while mean baseline CRP in the PALACE 1, 3 and 4 trials was, respectively, 8.4 mg/L, 11.5 mg/L and 8 mg/L.34 36–38 Baseline CRP levels were not reported in the PALACE 2 trial.35 Thus despite the numerical difference of baseline CRP levels in the ACTIVE trial and PALACE 1, 3 and 4 trials, their outcome is comparable.34–38 These limited observations do not demonstrate a significant impact of CRP levels on ACR20 response. However, as mentioned earlier, further investigations with correction for covariates are required for more clearer conclusions.

Several subanalyses investigated the correlations between baseline CRP levels, the evolution of CRP levels and clinical outcomes within the studies.12 15 18 20 27 30 32

A significant difference, between levels of CRP at week 52 in patients who achieved MDA criteria and those who did not, was found in the IMPACT two trial: median CRP 4 mg/L (IQR, IQR 4–6) vs median CRP 5 mg/L (IQR 4–13), respectively.12 CRP may thus be a valid predictor for radiographic progression and elements of clinical outcome, which may implicate that elevated levels of CRP could imply a better chance for response to therapy.

On the other hand, some observations challenge the predictive value of CRP levels. In the DISCOVER 2 trial, patients were stratified by their most recent high-sensitivity serum CRP value before randomisation: <20 mg/dL vs ≥20 mg/L.30 Similar ACR20 response patterns were observed for both guselkumab dosing administrations across patient subgroups.30 Also Furthermore, in the 2 PSUMMIT trials, no significant correlation between CRP levels and baseline joint disease activity, or CRP and therapeutic response to ustekinumab in either the skin or joints were observed, despite rapid reductions in CRP levels following ustekinumab therapy.27 In the ASTRAEA trial, improvements in patient-reported outcomes in patients who received abatacept were numerically but not significantly greater in patients with elevated baseline CRP levels.32 These contradictory findings indicate the need for further research regarding the predictive value of CRP.

CRP as a predictor of structural progression

Three of eight studies using a minimum level of baseline CRP as inclusion criterion included a radiographic outcome measure.16 19 30 Some subanalyses suggest a predictive value for CRP.15 18 For example, a subanalysis of the ADEPT trial, identified elevated baseline CRP as a strong independent predictor of radiographic progression for placebo-treated but not for adalimumab-treated patients.15 The difference in benefit from treatment with adalimumab versus placebo was most clear for patients with the highest CRP levels at baseline (CRP ≥20 mg/L).15 Subanalyses of the OPAL BROADEN trial also showed an association between CRP levels at baseline and greater structural progression, but changes in radiographic outcome were minimal regardless of CRP levels in patients treated with tofacitinib or adalimumab.18

CRP as a criterion for early escape

None of the studies used CRP levels as a criterion for early escape. Early escape criteria were mainly based on percentage of improvement in both swollen and tender joint counts at different stages in time, with required percentages for continuation of intervention varying from 5% to 20%.11 13 14 16 19 21–26 28–31 34–38

Discussion

CRP and ESR are traditionally suggested as easy point-of-care laboratory markers of systemic inflammation to support diagnosis and measure disease activity in PsA.1–3 5 9 However, in PsA CRP levels have shown to not increase consistently with disease activity.1–3 5 9 Nevertheless, CRP is regularly used individually in RCTs as part of the evaluation of disease activity and as a prognostic factor for long-term outcomes. In addition, CRP is included in different composite measures for monitoring disease activity in PsA, like ACR-20, –50, −70 response, DAS-28 CRP, DAPSA, and PASDAS.

In the studied phase 3 studies with biologicals in PsA, CRP levels within the PsA study population tend to be very heterogeneous.11 13 14 16 17 19 26 28–31 33 34 36–38 In general, baseline CRP levels are lower in those studies without enrolment requirement criteria for CRP.34 Although CRP levels are often normal in PsA, one-third of the studies used CRP as a way of identifying active disease.11 16 19 26 28–30 38 Using CRP levels as inclusion criterion possibly reduces the representativeness of the study population for the global patient population. In the DISCOVER 2 study for example, which used CRP as an inclusion criterion, the randomised study population had a high average of swollen and tender joints along with substantial systemic inflammation.30 This may possibly reduce the applicability of conclusions to patients who, despite lower CRP levels, also suffer from active disease and clearly require therapy.30 Lack of awareness among non-experts about the limitations of generalisability in these specific clinical trials carries some risks for patient care: underestimation of disease severity in patients with normal CRP levels, too strict criteria for reimbursement of advanced therapies by third party private or governmental organisations.

All 22 studies used response criteria or disease activity tools including CRP levels in the composite measure, such as the ACR response and the DAS28-CRP.10 11 13 14 16 17 19 21–26 28–31 33–39

Measuring CRP levels thus indirectly has an influence on the perceptions of response and disease activity potentially guiding clinical decisions. But only one out of seven studies that evaluated the individual components of the ACR response could reveal a significant decrease in CRP levels along with significant improvement of other endpoints.11 17 33–37 First, this demonstrates that CRP response might not be sensitive to change in this particular situation because the levels at baseline are too low and do not reflect active disease. Second, CRP is less useful for measuring treatment response in PsA in contrast to rheumatoid arthritis. Especially in the DAS28-CRP, CRP is not an ideal component because it will not, or to a lesser extent contribute to the decrease of the obtained score. It will also make the tool less valid because each component in the DAS28 is weighted, based on the original studies in rheumatoid arthritis, characterised by much higher levels of CRP.41 Other tools as DAPSA and PASDAS also use CRP but with a different weighting.42 43 DAPSA was developed based on the data of the IMPACT trial and PASDAS was developed specifically for PsA based on a real-world clinical cohort in more than 30 different centres.42 43 In both populations, the CRP at baseline or inclusion is substantially lower than what is found in RA patients.42 43 Therefore, our review indirectly supports the use of PsA specific scores such as DAPSA and PASDAS in the clinical trial setting, and by extension in clinical practice when considering treat-to-target approaches.

On the other hand, a CRP threshold might be used to enrich the cohort for patients likely to achieve important treatment targets, such as radiographic progression or remission. For example, almost half of the studies using a CRP threshold also included an individual radiographic outcome measure.16 19 30 None of the studies reported remission as outcome and study designs of studies reporting MDA were very heterogeneous, thus no conclusion could be drawn.

Various subanalyses suggest and support high baseline CRP levels as a predictor of radiographic progression.2 5 12 15 18 20 27 30 32 Taking into account, the importance of radiographic progression in the long-term impact of disease, this is a valid strategy to position the advance treatment options available and their long-term value. Impact of therapy on long-term outcomes, in particular disability, has been an important factor in securing third party reimbursement support for relatively expensive drugs.

Yet, the disease burden of PsA can also be high in patients with low CRP levels and potentially lower risk for radiographic progression. Elevated levels of CRP may predict a better response to therapy, but some studies contradict this statement.27 30 32 Our limited comparable data did not suggest a numerical difference in ACR response between studies that used elevated CRP levels as inclusion criteria and studies that did not.14 16 34–38 In daily practice, physicians should remain aware that CRP may not be elevated in a large group of the patients limiting support to allow CRP by itself to play a prominent role in treatment decision making.

The exact aetiology of PsA remains to be understood, but many immune system markers other than CRP have been suggested to quantify systemic inflammation in PsA even when CRP is normal.2–5 9 Low or absent CRP levels in PsA are considered to be explained by the fact that IL-6 plays no critical role in PsA.9 IL-6 is an important stimulator of CRP, by inducing hepatic synthesis of CRP.3 Several other laboratory markers such as beta-defensin 2, lipocalin-2, calprotectin, IL-8 and IL-22 are being investigated.9 Further investigations to determine their accuracy and the contribution of PsA phenotype to alteration of serum markers are required.9 The discrepancy between CRP levels and joint involvement also raises the question whether PsA disease processes mainly take place at a local instead of at a systemic level.

In conclusion, CRP levels cannot be considered as an individual criterion for evaluating disease activity or measuring treatment response in the large group of PsA patients. Hence, the usability of CRP in composite scores such as ACR20 or DAS28-CRP in daily clinical practice is also limited since this affects their sensitivity to change. High CRP levels are useful as individual predictor for disease progression, response to treatment and cardiovascular comorbidities, but the current conflicting findings are insufficient to allow CRP to play a key role in treatment decision making yet. This is an interesting research track to explore in the future. For the scientific community as well as for reimbursement policy-makers, it remains important to understand that limitations of generalisability of clinical trial data are a common problem. Hence, our strategies to demonstrate the value of new treatments to find market access and reimbursement must be complemented by extending pivotal clinical trial data with real-life observations and strategies. Whereas noise reduction is essential in the complex and expensive clinical trial setting to detect the clear signal and make good drugs available, a different approach towards generalisability is essential in the long term to ensure that all those that will benefit get the drugs that they need.

Footnotes

Twitter: @TissueHomandDis

Contributors: CH and RL conceived the study, acquired and analysed the data. CH, RL, BN, KdV wrote the manuscript. RL acts as guarantor for this work.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: Leuven Research and Development, the technology transfer office of KU Leuven, has received consultancy, speaker fees and research grants on behalf of Rik Lories from AbbVie, Amgen (formerly Celgene), Boehringer-Ingelheim, Eli-Lilly, Galapagos, Janssen, Kabi-Fresenius, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Biosplice Therapeutic (formerly Samumed), Sandoz and UCB.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information. Data were extracted from existing literature and are therefore available to all.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study does not involve human participants.

References

- 1.Ritchlin CT, Colbert RA, Gladman DD. Psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2017;376:957–70. 10.1056/NEJMra1505557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Punzi L, Podswiadek M, Oliviero F, et al. Laboratory findings in psoriatic arthritis. Reumatismo 2007;59 Suppl 1:52–5. 10.4081/reumatismo.2007.1s.52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Girolomoni G, Gisondi P. Psoriasis and systemic inflammation: underdiagnosed enthesopathy. JEADV 2009;23:3–8. 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03361.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menter A. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis overview. Am J Manag Care 2016;22:s216–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coates LC, Helliwell PS. Psoriatic arthritis: state of the art review. Clin Med 2017;17:65–70. 10.7861/clinmedicine.17-1-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor W, Gladman D, Helliwell P, et al. Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2665–73. 10.1002/art.21972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raychaudhuri SP, Wilken R, Sukhov AC, et al. Management of psoriatic arthritis: early diagnosis, monitoring of disease severity and cutting edge therapies. J Autoimmun 2017;76:21–37. 10.1016/j.jaut.2016.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gossec L, Baraliakos X, Kerschbaumer A, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:700.1–12. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sokolova MV, Simon D, Nas K, et al. A set of serum markers detecting systemic inflammation in psoriatic skin, entheseal, and joint disease in the absence of C-reactive protein and its link to clinical disease manifestations. Arthritis Res Ther 2020;22. 10.1186/s13075-020-2111-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gladman DD, Mease PJ, Healy P, et al. Outcome measures in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2007;34:1159–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antoni C, Krueger GG, de Vlam K, et al. Infliximab improves signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis: results of the impact 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:1150–7. 10.1136/ard.2004.032268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coates LC, Helliwell PS. Validation of minimal disease activity criteria for psoriatic arthritis using interventional trial data. Arthritis Care Res 2010;62:965–9. 10.1002/acr.20155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kavanaugh A, McInnes I, Mease P. Golimumab, a new human tumor necrosis factor α antibody, administered every four weeks as a subcutaneous injection in psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:976–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mease PJ, Gladman DD, Ritchlin CT, et al. Adalimumab for the treatment of patients with moderately to severely active psoriatic arthritis: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:3279–89. 10.1002/art.21306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gladman DD, Mease PJ, Choy EHS, et al. Risk factors for radiographic progression in psoriatic arthritis: subanalysis of the randomized controlled trial ADEPT. Arthritis Res Ther 2010;12:R113. 10.1186/ar3049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mease PJ, van der Heijde D, Ritchlin CT, et al. Ixekizumab, an interleukin-17A specific monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results from the 24-week randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled and active (adalimumab)-controlled period of the phase III trial SPIRIT-P1. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:79–87. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mease P, Hall S, FitzGerald O, et al. Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo for psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1537–50. 10.1056/NEJMoa1615975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Heijde D, Gladman DD, FitzGerald O, et al. Radiographic progression according to baseline C-reactive protein levels and other risk factors in psoriatic arthritis treated with tofacitinib or adalimumab. J Rheumatol 2019;46:1089–96. 10.3899/jrheum.180971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mease PJ, Fleischmann R, Deodhar AA, et al. Effect of certolizumab pegol on signs and symptoms in patients with psoriatic arthritis: 24-week results of a phase 3 double-blind randomised placebo-controlled study (RAPID-PsA). Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:48–55. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Heijde D, Deodhar A, Fleischmann R, et al. Early disease activity or clinical response as predictors of long-term outcomes with Certolizumab pegol in axial spondyloarthritis or psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2017;69:1030–9. 10.1002/acr.23092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mease PJ, McInnes IB, Kirkham B, et al. Secukinumab inhibition of interleukin-17A in patients with psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1329–39. 10.1056/NEJMoa1412679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McInnes IB, Mease PJ, Kirkham B, et al. Secukinumab, a human anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriatic arthritis (future 2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2015;386:1137–46. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61134-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nash P, Mease PJ, McInnes IB, et al. Efficacy and safety of secukinumab administration by autoinjector in patients with psoriatic arthritis: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled trial (future 3). Arthritis Res Ther 2018;20:47. 10.1186/s13075-018-1551-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kivitz AJ, Nash P, Tahir H, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Subcutaneous Secukinumab 150 mg with or Without Loading Regimen in Psoriatic Arthritis: Results from the FUTURE 4 Study. Rheumatol Ther 2019;6:393–407. 10.1007/s40744-019-0163-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mease P, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, et al. Secukinumab improves active psoriatic arthritis symptoms and inhibits radiographic progression: primary results from the randomised, double-blind, phase III future 5 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:890–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McInnes IB, Kavanaugh A, Gottlieb AB, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: 1 year results of the phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled PSUMMIT 1 trial. The Lancet 2013;382:780–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60594-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siebert S, Sweet K, Dasgupta B, et al. Responsiveness of serum C‐Reactive protein, Interleukin‐17A, and Interleukin‐17F levels to ustekinumab in psoriatic arthritis: lessons from two phase III, multicenter, Double‐Blind, Placebo‐Controlled trials. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:1660–9. 10.1002/art.40921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ritchlin C, Rahman P, Kavanaugh A, et al. Efficacy and safety of the anti-IL-12/23 p40 monoclonal antibody, ustekinumab, in patients with active psoriatic arthritis despite conventional non-biological and biological anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy: 6-month and 1-year results of the phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised PSUMMIT 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:990–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deodhar A, Helliwell PS, Boehncke W-H, et al. Guselkumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis who were biologic-naive or had previously received TNFα inhibitor treatment (DISCOVER-1): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2020;395:1115–25. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30265-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mease PJ, Rahman P, Gottlieb AB, et al. Guselkumab in biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis (DISCOVER-2): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. The Lancet 2020;395:1126–36. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30263-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mease PJ, Gottlieb AB, van der Heijde D, et al. Efficacy and safety of abatacept, a T-cell modulator, in a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III study in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1550–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strand V, Alemao E, Lehman T, et al. Improved patient-reported outcomes in patients with psoriatic arthritis treated with abatacept: results from a phase 3 trial. Arthritis Res Ther 2018;20:269. 10.1186/s13075-018-1769-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gladman D, Rigby W, Azevedo VF, et al. Tofacitinib for psoriatic arthritis in patients with an inadequate response to TNF inhibitors. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1525–36. 10.1056/NEJMoa1615977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, Gomez-Reino JJ, et al. Treatment of psoriatic arthritis in a phase 3 randomised, placebo-controlled trial with apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1020–6. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-205056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cutolo M, Myerson GE, Fleischmann RM, et al. A phase III, randomized, controlled trial of apremilast in patients with psoriatic arthritis: results of the PALACE 2 trial. J Rheumatol 2016;43:1724–34. 10.3899/jrheum.151376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edwards CJ, Blanco FJ, Crowley J, et al. Apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, in patients with psoriatic arthritis and current skin involvement: a phase III, randomised, controlled trial (PALACE 3). Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:1065–73. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wells AF, Edwards CJ, Kivitz AJ, et al. Apremilast monotherapy in DMARD-naive psoriatic arthritis patients: results of the randomized, placebo-controlled PALACE 4 trial. Rheumatology 2018;57:1253–63. 10.1093/rheumatology/key032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nash P, Ohson K, Walsh J, et al. Early and sustained efficacy with apremilast monotherapy in biological-naïve patients with psoriatic arthritis: a phase IIIB, randomised controlled trial (active). Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:690–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eissa M, El Shafey A, Hammad M. Comparison between different disease activity scores in rheumatoid arthritis: an Egyptian multicenter study. Clin Rheumatol 2017;36:2217–24. 10.1007/s10067-017-3674-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coates LC, Fransen J, Helliwell PS. Defining minimal disease activity in psoriatic arthritis: a proposed objective target for treatment. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:48–53. 10.1136/ard.2008.102053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wells G, Becker J-C, Teng J, et al. Validation of the 28-joint disease activity score (DAS28) and European League against rheumatism response criteria based on C-reactive protein against disease progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and comparison with the DAS28 based on erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:954–60. 10.1136/ard.2007.084459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schoels M, Aletaha D, Funovits J, et al. Application of the DAREA/DAPSA score for assessment of disease activity in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1441–7. 10.1136/ard.2009.122259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Helliwell PS, FitzGerald O, Fransen J, et al. The development of candidate composite disease activity and Responder indices for psoriatic arthritis (grace project). Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:986–91. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information. Data were extracted from existing literature and are therefore available to all.