Abstract

During the first period of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, the lack of specific therapeutic treatments led to the provisional use of a number of drugs, with a continuous review of health protocols when new scientific evidence emerged. The management of this emergency sanitary situation could not take care of the possible indirect adverse effects on the environment, such as the release of a large amount of pharmaceuticals from wastewater treatment plants. The massive use of drugs, which were never used so widely until then, implied new risks for the aquatic environment. In this study, a suspect screening approach using Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry techniques, allowed us to survey the presence of pharmaceuticals used for COVID-19 treatment in three WWTPs of Lombardy region, where the first European cluster of SARS-CoV-2 cases was detected. Starting from a list of sixty-three suspect compounds used against COVID-19 (including some metabolites and transformation products), six compounds were fully identified and monitored together with other target analytes, mainly pharmaceuticals of common use. A monthly monitoring campaign was conducted in a WWTP from April to December 2020 and the temporal trends of some anti-COVID-19 drugs were positively correlated with those of COVID-19 cases and deaths. The comparison of the average emission loads among the three WWTPs evidenced that the highest loads of hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin and ciprofloxacin were measured in the WWTP which received the sewages from a hospital specializing in the treatment of COVID-19 patients. The monitoring of the receiving water bodies evidenced the presence of eight compounds of high ecological concern, whose risk was assessed in terms of toxicity and the possibility of inducing antibiotic and viral resistance. The results clearly showed that the enhanced, but not completely justified, use of ciprofloxacin and azithromycin represented a risk for antibiotic resistance in the aquatic ecosystems.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, Drugs consumption, Antiviral drugs, Antibiotics, Suspect screening, Wastewater-based epidemiology

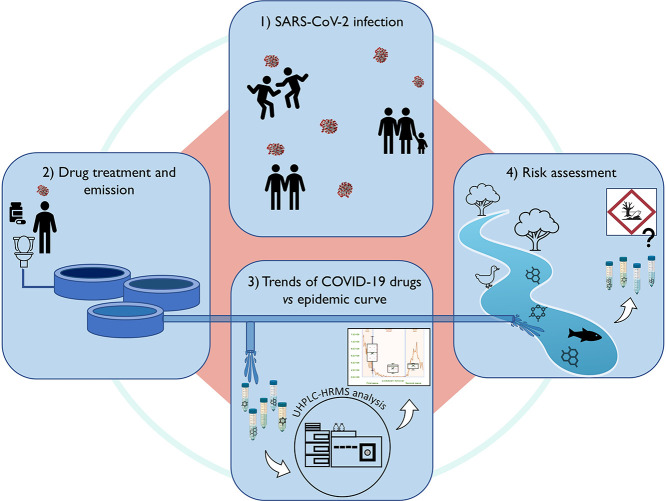

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Since the first months of 2020, the pandemic of SARS-CoV-2 has been deeply impacting the health, the economy and the social life of most of the citizens all over the world. The spreading of the global disease had also a significant impact on the environment (Barcelo, 2020; Zambrano-Monserrate et al., 2020). Both positive and negative effects were observed, from the reduction of human footprint on the environment to the disposal of the plastic waste from personal protective clothing and equipment, and the increased emissions of disinfectants, antimicrobials and pharmaceuticals employed to fight against COVID-19 (Binda et al., 2021; Race et al., 2020). Reduction of transport, journeys and economical activities had the positive effects of reducing the atmospheric pollution at global (Lal et al., 2020) and urban scales (Bao and Zhang, 2020; Collivignarelli et al., 2020) as well as improving the surface water quality thanks to the reduced deposition from nonpoint sources of pollution (Hallema et al., 2020) and the reduced emission of suspended particulate matter in the lagoon (Braga et al., 2020) and lake waters (Yunus et al., 2020).

On the contrary, since the beginning of the pandemic, many studies reviewed the role of urban wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) in spreading the virus excreted from the human body of infected people (Godini et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2021; Naddeo and Liu, 2020), which was early detected in wastewaters (La Rosa et al., 2020; Medema et al., 2020; Randazzo et al., 2020) and even in the receptor water bodies (Haramoto et al., 2020; Rimoldi et al., 2020). Furthermore, wastewaters are known sources of chemical pollutants which mainly originate from human activities. In the case of pharmaceuticals, the private consumption results in a continuous emission of parent and metabolized molecules that flow into wastewaters and, once in the WWTP, end up in the effluent without being degraded. During the epidemic peak, a massive use of pharmaceuticals, most of which had never been used before in such amount, has occurred, causing a sudden increase in the concentrations of these drugs in surface waters (Bandala et al., 2021). This positive trend has been also documented for hand sanitizers (Mahmood et al., 2020) and quaternary amines (Hora et al., 2020), which may imply an increased chance of antimicrobial resistance emergence (Alygizakis et al., 2021). The wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) approach has also been used to study the change in drug consumption or even abuse along with the emergency of pandemic and the beginning of the lockdown measure (Choi et al., 2018). Patterns of changes in consumption of drugs of abuse and psychoactive substances during lockdowns were highly heterogeneous across Europe (Been et al., 2021; Reinstadler et al., 2021) and USA (Nason et al., 2021a). Changes in consumption of different classes of pharmaceuticals between 2019 and 2020 have been highlighted in wastewaters of Athens, Greece (Galani et al., 2021) while the trend of consumption of pharmaceuticals during the pandemic has been studied in the wastewaters of New York, USA (Wang et al., 2020), in environmental surface waters around Wuhan, China (Chen et al., 2021) and in the sewage sludges in Connecticut, USA (Nason et al., 2021a). According to the One Health perspective, a key point is to track the potential increase in discharge of antimicrobials (Alygizakis et al., 2021), including antibiotics and antivirals, which might develop and spread the environmental antimicrobial resistance (Knight et al., 2021) as well as the less studied antiviral resistance (Kuroda et al., 2021; Nannou et al., 2020).

Giving that consolidated therapeutical protocols were still not available during the first pandemic period, a wide range of therapies has been tested during the clinical progression of the disease: the main administered classes ranged from anti-retroviral medicines used for AIDS, to antimalarial drugs (chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine), from antibiotics, like azithromycin, to analgesic drugs, like acetaminophen useful for treating minor symptoms; in most cases, a combination of them was used, as in the case of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin. The present paper aims to study the emission of pharmaceuticals employed against SARS-CoV-2 infection in wastewaters and their impact on receiving water bodies in an area of Northern Italy (counties of Milano and Monza) which was severely affected by the disease during the first epidemic wave (Castiglioni et al., 2021). The lockdown and the restriction of the research activities, together with the possible sanitary risk connected with the sample handling of wastewater samples (Rimoldi et al., 2020), induced us to adopt a straightforward analytical method which includes only sample filtration and injection as preparation steps, without sample extraction and enrichment. Because shared clinical guidelines and care protocols had not been established in the first phase of the outbreak, it was necessary to carry out a wide analytical screening of suspected pharmaceuticals by using Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography, hyphenated with High Resolution Mass Spectrometry (UHPLC-HRMS). This is the first work that apply suspect screening techniques with HRMS to investigate the legal and illegal use of pharmaceuticals against COVID-19. The monitoring campaign started in April 2020, in parallel with some measurements of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewaters of three WWTPs and streams flowing in the same area (Rimoldi et al., 2020). The monitoring period continued till December 2020 in order to study the qualitative and quantitative trend of drug consumption along with the evolution of the pandemic, according to the sewage epidemiology approach (Vitale et al., 2021; Ort et al., 2018). Among the anti-COVID drugs, a special focus has been devoted to the temporal trend of therapies based on hydroxychloroquine, whose off-label use in combination with azithromycin was authorized in the first pandemic phase and then suspended on May 26th, 2020 by the Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA), since an increase in risk for adverse reactions in face of poor or absent benefits was observed (AIFA, 2020a). Furthermore, the set of pharmaceuticals selected by suspect analysis in wastewaters were also quantitatively monitored in different wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) in the same area and in their receiving surface water bodies, in order to assess the potential increase in ecological risk.

The data collected in the present work allowed us to: a) identify the consumption trend of pharmaceuticals against COVID-19 in the first eight months of the pandemic by using the suspect screening approach; b) estimate the per capita emission loads of pharmaceuticals in order to highlight the change of use during the pandemic; c) compare the emission load of hydroxychloroquine with the official purchase data in order to highlight any possible illegal purchases; d) estimate the removal capabilities of the wastewater treatment plants; e) assess the risk of the increased release of pharmaceuticals into the aquatic environment, evaluating also specific risks of developing antibiotic and antiviral resistance.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Sampling area: WWTPs characteristics and receiving water bodies

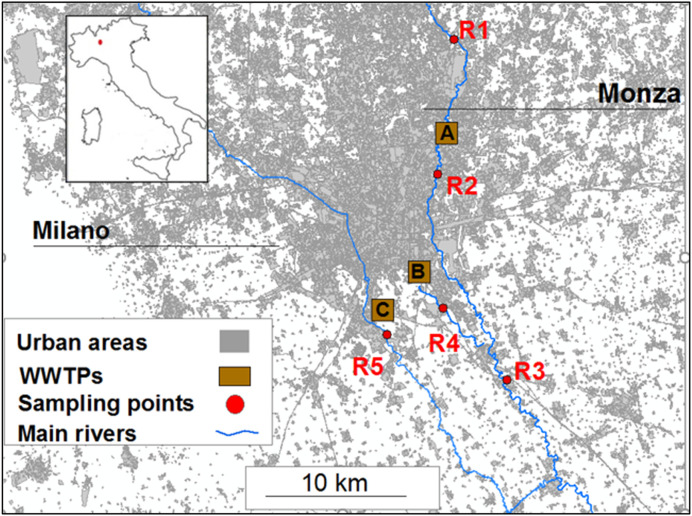

Wastewater samples of WWTP inlets and outlets were collected in three different plants located in the urban conglomeration of Milano and Monza (Lombardy region, Northern Italy), serving a population equivalent (p.e.) of more than 2 million persons (Rimoldi et al., 2020). WWTP-A is located in Monza, only 12 km far from Milano, which is the biggest town of Northern Italy. WWTP-B is located in the south-east area of Milano, while WWTP-C collects sewages from the south-west area of Milano. All WWTPs employ similar conventional treatment processes: the primary treatment for particles removal, the secondary biological treatment based on activated sludge process and the final process of disinfection. WWTP-A and C are equipped with UV lamps and WWTP-B performed disinfection with the use of peracetic acid. Additional information about the studied WWTPs and the chemical characteristics of the influents are reported in Table S10. Furthermore, the water bodies (Lambro River, Vettabbia Canal and Lambro Meridionale River, respectively indicated as R2, R4 and R5 sampling points), which receive outlet waters from the monitored WWTPs, were also sampled. Further monitoring sites on Lambro river have been located at Villasanta, upstream of the WWTP-A (R1), and at Melegnano (R3), south of Milano, which can be considered the closure point of the northern sub-basin of that river (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Map of the sampling sites located in Lombardy region. The colored squares indicate the studied WWTPs and the red dots the sampling points of the surface waters.

2.2. Sample collection and pre-treatment

All the samples were collected between April and December 2020. The influents and the effluents of WWTP-A were collected from April 9th to August 5th and then the sampling of influents weekly continued until mid-December. In the same period, upstream river (R1, two samples) and downstream river (R2, sixteen samples) were collected. WWTP-B and WWTP-C influents, effluents and their receiving water bodies (R3, R4 and R5) were collected between April and May 2020.

River and wastewater grab samples were collected with stainless steel buckets and transported in amber glass bottles to laboratory in less than two hours. Rivers were sampled from the bridges at the middle of the riverbed. Each sample was immediately filtered into a glass LC-vial with a 0.45 μm cellulose acetate membrane syringe filter (Ghiaroni & C, Milan, Italy). Filtered samples were stored at 4 °C and analyzed within three days otherwise they were frozen (−20 °C) till analysis. Background samples were prepared with the initial elution phase of the chromatographic gradient. The procedural blanks were prepared as the samples using ultrapure water.

2.3. Sample analysis

2.3.1. Chemicals and reagents

All the reagents and solvents were analytical reagent grade or LC–MS grade. Ultrapure water was produced by a Millipore Direct-QUV water purification system (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA).

The stable isotope-labeled atrazine and the reference standards (purity >98%) for target analytes and confirmed suspects were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany) and stored under recommended conditions until use. Stock solutions of the reference standards (100 mg/L) were prepared in methanol and stored in the dark at −20 °C. Internal standard solution containing the isotope-labeled atrazine was prepared in methanol at a concentration of 10 μg/L.

The mixture for Retention Time Index (RTI) calibration was kindly dispatched by Laboratory of Analytical Chemistry, Department of Chemistry, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens and supported by NORMAN network (Aalizadeh et al., 2021; Dulio et al., 2020).

2.3.2. UHPLC-Orbitrap-MS analysis

All samples were analyzed by Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled to Orbitrap High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry analyser (UHPLC-Orbitrap-MS). The mass spectrometer was a Q Exactive™ UHMR Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap™ Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, USA) equipped with a heated electrospray ionization (HESI) source and coupled to Ultimate 3000 UHPLC system (Thermo Scientific, USA). A reversed-phase Raptor C18 (2.1 mm × 150 mm; particle size of 1.8 μm; Restek Corporation, Bellefonte, PA, USA) was used with a binary mobile phase gradient consisting of (A) 5 mM aqueous ammonium formate, adjusted to pH 3.0 with formic acid and (B) acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid. Eluent flow and gradient are reported in Fig. S1.

The injection volume was 95 μL of sample and 5 μL of internal standard solution. Throughout the whole separation, the sampler compartment temperature was 10 °C, and the column temperature was 30 °C. The HESI operated in positive ionization mode with the probe position set to C (Fig. S2). The Orbitrap-MS detector acquired data in the full scan/data-dependent mode (top 5) using 214.08963 as lock mass (Fig. S3).

2.4. HRMS data processing

2.4.1. Selection of the anti-COVID-19 drugs for the suspect screening list

The list of anti-COVID-19 drugs, including their possible human metabolites and transformation products for suspect screening, was compiled following the prescriptions of the Italian Medicines Agency and the Regional Health Protection Agency of Lombardy (AIFA, 2020b), and then was integrated by literature research and monitoring on https://www.covid19-trials.com/ website, provided by Cytel company, which tracks worldwide study trials focused on medicines tested for COVID-19, including the Italian ones.

The initial suspect list (n = 63), including 40 compounds, 22 related human metabolites and 1 transformation product, is reported in the Table S1a. From this list, a further selection had been applied in order to generate the final inclusion list (n = 58) of compounds to be investigated in the samples. Compounds with a molecular weight higher than 950 Da, therefore exceeding the mass range set on the instrument (e.g. enoxaparin sodium and antibodies) and compounds not detectable in positive ionization mode (e.g. acetylsalicylic acid) were excluded. The Orbitrap inclusion list is reported in the Table S1b.

2.4.2. Suspect workflow: automated screening

HRMS raw files were processed using Compound Discoverer 3.1 (CD 3.1; Thermo Scientific, USA) in order to identify the presence of anti-COVID-19 drugs, their possible human metabolites and transformation products.

The automated screening procedure consisted of peak picking and integration, retention time alignment, detection of isotope peaks and adduct peaks, isotope and adduct peak grouping, compound grouping across samples, a signal to noise ratio of 3, background subtraction (five times the maximum peak area in the background samples), and database searching. Additional filters were set: retention time (RT) greater than 2 min, a coefficient of variation of the signal intensity in the three replicates <30% and suspect compound's peak area at least five-times that of procedural blanks.

2.4.3. Prioritization and identification: manual screening

Subsequently the automatic procedure, the remnant suspect compounds were visually screened and manually excluded if extracted from a very noisy ion chromatogram and if the predicted RT obtained from the Retention Time Indices Platform was unrealistic (Aalizadeh et al., 2021; Retention Time Indices Platform). The Retention Time Index (RTI) approach, which is based on a quantitative structure-retention relationship model (QSRR), can automatically assess the plausibility of the experimental (Exp) RT of the suspect candidate compared to that predicted (Pred) by the model. Entering the chemical structure information of each suspect candidate, with SMILES script, and the RT obtained from the analysis, the system can predict the expected RT by comparing RTs of a calibrant mixture (14 molecules of different polarity injected during the same analysis) with the RTs of the suspect candidates. The output is a four-category classification (from box 1 to box 4) that ranges from “Exp. & Pred. RT are accepted for this candidate” to “Pred./Exp. RT are not reliable” and only candidates belonging to category 1 or 2 were considered (Table S4).

After the exclusion procedure, suspect hits were tentatively identified assigning an interim confidence level (Schymanski et al., 2014) according to the following criteria:

-

1)

mass accuracy: candidates must have a neutral mass error <±5 ppm;

-

2)

isotopic pattern: presence of at least the m0 isotope since we expected peaks with low intensity, and the distinction of isotopic pattern for chlorinated candidate structures;

-

3)

predicted composition: match of the molecular formula between the top 10 results;

Confidence level 2A was assigned by matching MS and MS2 experimental data with mass spectral fragment libraries. Two different online databases which feature a searchable collection of high resolution and accurate mass spectral databases were used: the first one (Thermo Scientific mzCloud) was included in Compound Discoverer 3.1 and runs in automatic mode. A minimum mzCloud score was set to >50%; whereas visually observation of the fragment fit was performed with the second one, MassBank Europe.

In the absence of experimental mass spectra in libraries, the spectra were compared with in silico fragments generated by FISh (Fragment Ion Search), in silico fragmentation algorithm embedded in Compound Discoverer 3.1 which provides a score in terms of percentage of theoretical fragments that matched those in the MS2 spectra, and with Thermo Scientific mzLogic algorithm which compares several structures proposed by ChemSpider.

If only the match with the in silico fragments was available, confidence level 3 was assigned. Finally, when no MS2 spectra could be acquired, caused by too low intensity, confidence level 4 was assigned (Table S3).

For the most promising and remarkable suspect candidates (confidence level ≤ 3), the reference standards were purchased if available. The confirmed suspect compounds were quantified in the water samples.

2.5. Quantification of target analytes and confirmed suspects

TraceFinder 3.3 (Thermo Scientific, USA) was used for quantification of the target analytes and confirmed (level 1) suspects. The calibration solutions of target analytes were included in each analytical sequence. Standard mixture solutions of the confirmed (level 1) suspects were injected after identification and the quantification has been carried out on the archived raw data files. Standard mixture solutions were daily prepared by diluting the standard stock solutions in ultrapure water to obtain six calibration points, ranging from 50 to 3000 ng/L.

2.6. Quality assurance and quality control

Orbitrap-MS detector was calibrated before each sequence and the systematic mass drift was controlled by using the lock mass mode. Matrix effects were kept at minimum by direct injection of the filtered samples (Li et al., 2018), without any pretreatment. The performances of the instrument (injection volume, instrument sensitivity and ionization efficiency) were continuously controlled by checking the variability of the peak areas and the retention times of the internal standard (isotope-labeled atrazine; number of replicates = 339) which resulted less than 18% and 2%, respectively (no retention time drift or sensitivity loss were observed). All suspect identifications were verified manually to reduce the possibility of false positive.

The procedural blanks were prepared like the samples using ultrapure water and included in each analytical sequence before and after calibration solutions and samples. No contamination originating from solvents and laboratory conditions were detected.

Quantification was performed by isotopic dilution method and calibration curves were acquired before each analytical run. In the considered concentration range, the response of the mass spectrometer was linear with a coefficient of determination (R2) higher than 0.98 for all the target compounds. Each sample was injected three times.

For the data analysis, the limit of quantification (LOQ) was set as the lowest point of the calibration curve obtained from the reference standard of the quantified compound (50 ng/L).

2.7. Risk assessment in surface waters

The assessment of the environmental risk was done considering the ecotoxicological risk and the potential development of antibiotic and antiviral drug-resistance. For the ecotoxicological risk, Risk quotients (RQs) were calculated as the ratio between the Measured Environmental Concentration (MEC) and the Predicted No-Effect Concentration (PNEC). The PNECs of the studied compounds were all derived from the NORMAN Ecotoxicology Database (Dulio et al., 2020), except for ofloxacin (Zhang et al., 2020). The lowest freshwater PNECs were selected considering both the experimentally-based values and the QSAR predicted values, and are reported in the Table S2. Furthermore, the PNECs for the selection of Antibiotic Resistance (PNECs-AR) were used to determine a potential risk derived from the environmental antibiotic concentration that select for resistant bacteria. PNECs-AR are obtained from the Minimal Inhibitory Concentrations (MICs), which are the lowest concentrations of antibiotic that inhibit the growth of a pathogenic bacteria. The antibiotic resistance usually occurs at sub-inhibitory concentration (sub-MIC) and PNECs-AR are extrapolated applying an assessment factor to the MIC (Bengtsson-Palme and Larsson, 2016; Andersson and Hughes, 2012; Gullberg et al., 2011). All the PNECs-AR were obtained from Bengtsson-Palme and Larsson, 2016 and used to calculate the risk quotients (RQs-AR).

For the RQs calculation (RQs and RQs-AR) of each compound, the 95th percentile of all the surface water measured concentrations (MEC 95th perc) was used. Below it is reported the equation:

The RQs were classified using this criterion: RQ < 0.1, negligible risk; 0.1 < RQ < 1, low risk; 1 < R < 10, medium risk; RQ > 10, high risk (Villa et al., 2020).

Additionally, the risk for the development of antiviral drug resistance was assessed using the calculation reported by Kuroda and co-workers, to obtain the Environmentally acquired antiviral Drug Resistance Potential (EDRP) (Kuroda et al., 2021):

where vEC50 is the antiviral agent concentration that determines 50% of the growth inhibition effect against SARS-CoV-2. vEC50s of hydroxychloroquine and darunavir were retrieved from Kuroda et al., 2021 and De Meyer et al., 2020, respectively.

EDRP is obtained as the minimum value between the ratio of MEC 95th percentile and vEC50, and its reciprocal. Since the risk of developing drug-resistant viral strains is greatest when the environmental concentrations are close to the vEC50 (Pillay and Zambon, 1998), the maximum risk occurs when EDRP is equal to 1, and minimum at 0.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed by using Excel Data Analysis Toolpack (version 16.43) and R Studio (version 1.1.463). The Spearman rank-order correlation, that can be used for non-normal data, was applied to assess the significance of the association between the chemical results and two COVID-19 metrics, such as the number of positive cases and the number of deaths, respectively (https://github.com/pcm-dpc/COVID-19/blob/master/dati-province/dpc-covid19-ita-province.csv). The significance level was set-up at p-value < 0.05. The Pearson's Correlation Coefficient (r) was used to evaluate the association between the purchase data of hydroxychloroquine and the emission loads from the influent samples. r values above 0.8 and below −0.8 were considered representative of a strong association. For the elaboration of the results, censored values were substituted with 1/2 LOQ.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Suspect screening of anti-COVID-19 drugs in wastewater samples

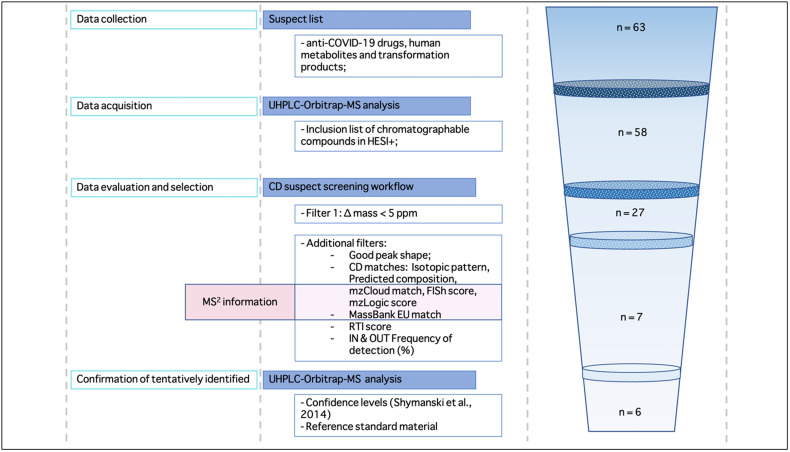

The suspect screening procedure consisted of three different steps: the data acquisition of chromatographic peaks, the evaluation phase based on MS and MS2 information and finally, a selection of the suspect compounds to be confirmed (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Schematic workflow of the suspect screening approach. The sequential reduction of number of suspect compounds (n) on the right side of the graph, shows the increasing confidence in the identification of suspects, until the final confirmation with the reference standards.

After CD automated processing, only 27 out of 58 suspect list masses have matched the experimental hits with a mass error lower than 5 ppm. Then, additional filters were applied (Table S3): all the selected features were visually judged based on the shape of the peaks and assuring they were different from background noise and from the procedural blanks; then, the MS information, such as the match with the isotopic pattern and the predicted compositions, which rank the possible chemical formulas of the detected compounds, were taken in consideration.

For 16 out of 27 suspect compounds, the MS2 spectra were not acquired because of their very low intensity, so a level of confidence of 4 was assigned. For the others 11 suspect compounds, the MS2 fragmentation spectra were available and compared with mzCloud and MassBank spectra libraries. For 4 out of them, positive matches with mass spectra libraries were found, because they meet the set requirement of ≥50% of similarity between the mzCloud spectra and the candidate, and/or positive matches with the experimental fragments in MassBank (only fragments with mass error <5 ppm were positively considered). For those four candidates a level of confidence of 2A was assigned, because the probable structure was elucidated by library spectrum matches. The remaining candidates with the MS2 information were classified as level 4 when their acquired mass spectra did not match with those collected in experimental or in silico libraries. Only two candidates (oseltamivir and oseltamivir carboxylate), which had a FISh score match greater than 50%, were identified with level 3 of confidence, meaning that a molecular formula was assigned but no sufficient information for one exact structure was available.

Then the RTI approach was applied, and only suspect compounds (19 out of the 27 suspect candidates) whose RTs fell into the first (box 1) or second (box 2) category were considered (Table S4).

The final choice of tentatively identified compounds was done selecting those complying a level of confidence of 2 or 3, satisfying the RTI score (category 1 or 2) and taking in consideration the frequency of detection of the suspect compounds in both influent and effluent samples, in order to focus the identification procedure on compounds effectively present in the real samples. 6 compounds (acetaminophen, darunavir, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir and oseltamivir) were selected as anti-COVID-19 drugs to be confirmed by the use of reference standards and a second run of analysis was done in order to retrospectively quantify these compounds in all the water samples.

An additional pharmaceutical compound, clavulanate, was investigated with the use of the available reference standard. Although this compound did not meet all the requirements (MS2 spectra was not available and a level of confidence of 4 was assigned), the suspect feature had the highest RTI score (box 1), it was present in all the influent samples (detection frequency: 100%) and its chromatographic peak had a maximum area value around 3.5 · 108 arbitrary units (a.u.) and an average of 2.8 · 107 a.u. in the influent sample group.

Retrospective analysis with pure standards confirmed all the 6 suspect candidates with confidence levels of 2 or 3 but not clavulanate, supporting the idea that the applied workflow successfully works only when all the requirements are fulfilled.

3.2. Quantification results of WWTP-A and correlations with COVID-19 metrics

The suspect screening led to the identification of 6 anti-COVID-19 drugs at level 1 of confidence, according to Schymanski et al. (2014). Thanks to the standard availability, we added some compounds to the already on-going routine target monitoring of wastewaters which included one urban tracer (caffeine), one industrial chemical (methyl-benzotriazole) and 20 pharmaceuticals (among them 13 antibiotics and one antiviral). One antibiotic (azithromycin) and the antiviral compound ritonavir, usually prescribed in combination with lopinavir for the treatment of HIV (DrugBank Online, Ritonavir), were also used for COVID-19 treatment. The final list of 29 target analytes is reported in the Table S2.

The results of the quantified compounds in the WWTP-A samples are reported in detail in Table S5, where the averages and the standard deviations of three sample injections are shown. Among all the investigated analytes, 12 compounds were detected in all the samples but below the LOQ, and they included three antivirals used for COVID-19, lopinavir, oseltamivir (these two identified by the suspect screening) and ritonavir.

Table 1 summarizes the results divided into the three phases of pandemic characterized by different levels of restrictions in Italy.

Table 1.

Concentrations of target analytes in the influents of WWTP-A collected during the three different phases of pandemic (April–December 2020).

| Sample group |

1) First wave |

2) Reopening phase |

3) Second wave |

Spearman's rank-order correlation fρ |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound class | Compound | Used for COVID-19 treatment | aMin (ng/L) | bMax (ng/L) | Mean (ng/L) | ± cSD (ng/L) | dFreq (%) | aMin (ng/L) | bMax (ng/L) | Mean (ng/L) | ± cSD (ng/L) | dFreq (%) | aMin (ng/L) | bMax (ng/L) | Mean (ng/L) | ± cSD (ng/L) | dFreq (%) | eDLnorm vs COVID-19 cases | eDLnorm vs COVID-19 deaths |

| Analgesic | Acetaminophen | ✓ | 5113 | 94,790 | 37,694 | 20,461 | 100 | 1276 | 25,772 | 10,882 | 7940 | 100 | <LOQ | 24,489 | 13,293 | 10,172 | 75 | 0,58 | 0,57 |

| Antipsychotic | Amisulpride | x | 189 | 62,278 | 16,793 | 20,019 | 100 | 197 | 51,946 | 7897 | 16,083 | 100 | 357 | 31,688 | 12,969 | 14,321 | 100 | −0,39 | −0,40 |

| Anticonvulsant | Carbamazepine | x | <LOQ | 477 | 225 | 133 | 96 | <LOQ | 135 | 85 | <LOQ | 70 | 65 | 207 | 127 | 64 | 100 | 0,69 | 0,67 |

| Antiretroviral | Darunavir | ✓ | 67 | 867 | 435 | 218 | 100 | <LOQ | 233 | 129 | 78 | 80 | 103 | 255 | 175 | 67 | 100 | 0,73 | 0,72 |

| Antimalarial | Hydroxychloroquine | ✓ | <LOQ | 1777 | 588 | 512 | 91 | 52 | 250 | 162 | 76 | 100 | <LOQ | 231 | 121 | 84 | 75 | 0,45 | 0,45 |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker | Irbesartan | x | 282 | 3080 | 1639 | 781 | 100 | 116 | 960 | 471 | 274 | 100 | 391 | 972 | 663 | 255 | 100 | 0,71 | 0,70 |

| Beta blocker | Metoprolol | x | <LOQ | 181 | 108 | <LOQ | 96 | <LOQ | 89 | 62 | <LOQ | 80 | 56 | 112 | 75 | <LOQ | 100 | − | − |

| Antibiotic | Azithromycin | ✓ | 71 | 13,065 | 3342 | 3240 | 100 | 327 | 3522 | 1577 | 1134 | 100 | 2249 | 13,202 | 7107 | 5452 | 100 | 0,36 | 0,37 |

| Ciprofloxacin | x | 130 | 18,929 | 4602 | 5540 | 100 | 1839 | 16,927 | 9625 | 4641 | 100 | 1650 | 16,691 | 10,178 | 6386 | 100 | −0,47 | −0,46 | |

| Clarithromycin | x | <LOQ | 806 | 309 | 183 | 91 | 96 | 307 | 164 | 62 | 100 | 154 | 364 | 245 | 99 | 100 | 0,54 | 0,53 | |

| Erythromycin | x | <LOQ | 262 | 94 | 73 | 64 | <LOQ | 459 | 80 | 138 | 20 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ | 0 | − | − | |

| Lincomycin | x | <LOQ | 332 | <LOQ | 72 | 14 | <LOQ | 1085 | 393 | 398 | 60 | <LOQ | 727 | 361 | 297 | 75 | − | − | |

| Norfloxacin | x | <LOQ | 5330 | 614 | 1208 | 59 | 106 | 3430 | 789 | 994 | 100 | 680 | 2735 | 1376 | 946 | 100 | − | − | |

| Ofloxacin | x | 84 | 2295 | 1024 | 514 | 100 | 186 | 694 | 432 | 162 | 100 | 119 | 859 | 526 | 319 | 100 | 0,59 | 0,59 | |

| Trimethoprim | x | <LOQ | 140 | 93 | <LOQ | 91 | 51 | 106 | 81 | <LOQ | 100 | 75 | 127 | 100 | <LOQ | 100 | − | − | |

| Alkaloid | Caffeine | x | 5153 | 43,046 | 21,134 | 8114 | 100 | 2477 | 24,066 | 11,906 | 7784 | 100 | <LOQ | 19,032 | 11,770 | 8922 | 75 | − | − |

| Industrial compound | Methyl-benzotriazole | x | 303 | 5425 | 1955 | 1449 | 100 | 203 | 3114 | 1439 | 1083 | 100 | 252 | 1544 | 873 | 557 | 100 | − | − |

Min: minimum concentration in the sample group.

Max: maximum concentration in the sample group.

SD: standard deviation.

Freq: frequency of detection of the compound in the sample group.

DLnorm: daily loads normalized for the population equivalent; it is expressed as mg/day/1000 inhabitants.

ρ: only statistically significant values (p-value < 0.05) were reported. Dashes represent non-significant values or compounds whose correlation was not derived because >30% of the data were below LOQ.

The first group included samples collected during the earliest spread of the infections, between April and May 2020, during which Lombardy region was exceptionally upset by the first unexpected outbreak in Europe. At national level, the most stringent lockdown was announced by the Italian government in early March and the end of the quarantine was declared on May 18th, given that the epidemic curve was consistently decreasing. From that day until the end of September, the country had lived a reopening phase, with a strong mitigation of restrictive measures. All the samples collected during this period belong to the group identified as “reopening phase”. From October of the same year, the epidemiological situation started to get worse again, leading to a new wave of cases and to new closures. This further phase of new restrictions and targeted regional lockdowns was imposed until mid-December and all the samples collected in these months are gathered in the “second wave” group.

We used the Spearman's rank-order correlation to verify the correlations between the compound concentrations in the influents and the epidemic curve. This tool was already used to correlate chemical results and COVID-19 metrics (Nason et al., 2021b; Wang et al., 2020). The influent daily loads, normalized for the WWTP-A population equivalent (DLnorm), were tested against two different metrics, used as indicators of epidemic curve trend: the number of positive cases and the number of deaths every 1000 inhabitants of Lombardy region, calculated as weekly averages.

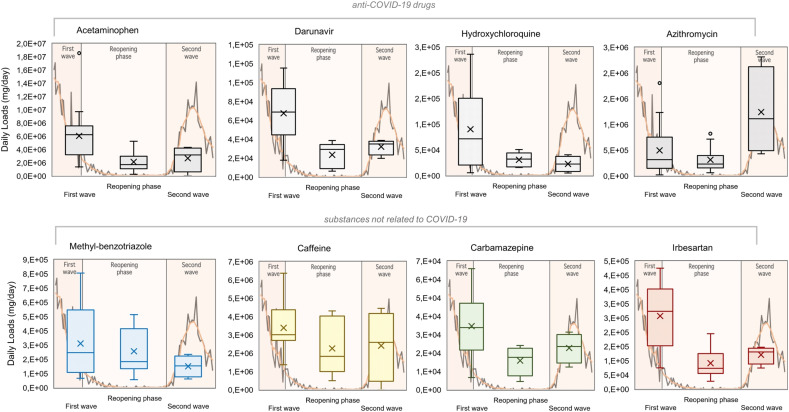

Table 1 reports the results of Spearman's correlations. Compounds with >30% of censored data (i.e. erythromycin and lincomycin) and non-statistically significant results (p-value > 0.05) were not included. The Spearman's ρ correlations with the two COVID-19 metrics gave similar results and showed that all the anti-COVID-19 drugs positively correlated with the trend of the epidemic curve (Fig. 3 ), and the highest significance level was obtained for darunavir (p = 8 · 10−7).

Fig. 3.

Boxplots of WWTP-A influents daily loads of target compounds during the three epidemic phases. In the background is reported the trend of COVID-19 deaths in Lombardy region (black line) and the weekly average (orange line). The anti-COVID-19 pharmaceuticals have a significant correlation (p-value < 0.05) with the COVID-19 metrics (number of deaths and number of cases); methyl-benzotriazole and caffeine do not statistically correlate with the epidemic curve; carbamazepine and irbesartan (not used for COVID-19 treatment) correlate with the epidemic curve.

This antiretroviral compound is usually prescribed in combination with other antiviral agents, such as ritonavir or cobicistat, as effective HIV infection therapy (DrugBank Online, Darunavir). In the early phase of pandemic, the off-label use of darunavir/cobicistat was allowed by the Italian Medicine Agency, but then, in light of new scientific evidence, the Italian Medicine Agency revoked the authorization with a statement published on July,17th (AIFA, 2020b). Nevertheless, darunavir was detected in the influents also during the second wave (“second wave” sample group: mean ± SD = 175 ± 67 ng/L; median = 118 ng/L), suggesting that its prescription against COVID-19 continued also during the second wave, despite the legally-binding indication of the Agency. Since the main authorized therapeutical use of darunavir was the daily treatment of HIV, its concentration in the wastewaters should not follow a seasonal trend. On the contrary our results are consistent with the purchase data published by the Agency itself, which show a further increase in the purchase of darunavir packs by the National Health System from September 2020, in synchrony with the beginning of the second pandemic wave (AIFA, 2020c).

A different trend has been evidenced for caffeine and methyl-benzotriazole which do not correlate with the epidemic curve (Fig. 3). Caffeine is usually correlated with the number of inhabitants (Senta et al., 2015), and its consumption did not change during the pandemic. Methyl-benzotriazole is principally used as a corrosion inhibitor (Cantwell et al., 2015) and the tendency of the industrial production had probably affected the measured concentrations. During the first weeks of emergency, 45% of Italian companies with three and more employees suspended the activities (except for the essential businesses). After the initial closure phase, 22.5% of companies declared to be able to reopen before May 4th, by requesting a derogation or by a voluntary decision (Binda et al., 2021; ISTAT, 2021). In fact, a significant increase in the concentrations of methyl-benzotriazole was observed from mid-April (Table S5).

It is interesting to note that amisulpride is negatively correlated with the epidemic curve and, looking at the data (Table S5), we noticed that an important increase in the concentrations of this antipsychotic compound started from the end of April, with the highest peak on May 13 (62.3 μg/L). On the contrary, for carbamazepine, an anticonvulsant that it is also used in the treatment of psychiatric diseases, a positive correlation with the epidemic curve was highlighted. The latter result is in line with Wang et al. (2020), who demonstrated a positive correlation of antiepileptics with both the virus RNA frequency of detection in the influents samples and the rate of positive cases, and with Alygizakis et al. (2021), who measured an increase in benzodiazepine emission during the pandemic. This correlation could be explained by considering that more than two months of isolation led to a worsening in patients with psychological problems, a known indirect adverse effect of pandemic on human health (Rossi et al., 2020).

Even the antihypertensive irbesartan and the two antibiotics ofloxacin and clarithromycin were positively correlated with the COVID-19 metrics. In general, the positive correlation might be explained as a consequence of the pandemic but also of seasonal changes that might result in a bias of the correlations. In fact, the decreasing of the curve exactly matched with the warmer seasons usually characterized by a lower incidence of infectious diseases and the hump of the second wave has risen again with the arrival of colder seasons. The positive correlation of antibiotics can be explained with the increase of seasonal diseases, but in the case of chronically used pharmaceuticals, like irbesartan, we can also hypothesize that patients with medical comorbidity could pay more attention to medical prescriptions during the lockdown phases than the reopening phase. Unlike what emerged for the other studied antibiotics, ciprofloxacin has a negative correlation with the epidemic trend. Previous studies on the relationship between the consumption of this fluoroquinolone antibiotic and the seasons were contrasting, showing both a strong seasonality (Coutu et al., 2013; Younes et al., 2019) and a weaker one (Durkin et al., 2018; Soucy et al., 2020). For sure, the pandemic had a strong impact on the antibiotic consumption. In Italy, the global consumption decreased in the first half of 2020 compared to 2019, with a reduction of purchased antibiotics in the pharmacies (−26.3%), in the hospitals (−1,3%) (AIFA, 2020d) and in the elderly population (−22.9%) (AIFA, 2020e). Despite this global negative trend of consumption, some classes of antibiotics were massively used at the beginning of pandemic in Italy, causing a peak in the purchase of macrolides (+77%), especially azithromycin (+160%) in March 2020, when no shared protocols to treat the SARS-CoV-2 infection were available (AIFA, 2020d). This phenomenon has already been reported in Europe (Galani et al., 2021) and in the rest of the world. Taking into consideration 24 studies from China, Spain, USA, Thailand and Singapore, it was calculated that more than 70% of patients received antibiotics although the overall proportion of COVID-19 patients with bacterial co-infections was only 7% (Langford et al., 2020). In Europe the proportion raised to 78% (Moretto et al., 2021) and different prescription patterns between countries were showed, reporting the use of heterogenous categories such as fluoroquinolones, third-generation cephalosporins and macrolides (Ghosh et al., 2021). These results might explain the impressive concentrations of both azithromycin and ciprofloxacin that were measured in the samples during the pandemic period. In order to confirm the occurrence of these amounts of pharmaceuticals, a short-term monitoring of other WWTPs, covering a larger population, together with a hospital outlet, were also carried out.

3.3. Per capita daily emissions for the different WWTPs

Averaged per capita daily emissions of the monitored compounds in the different WWTPs were calculated by multiplying measured concentrations by the daily averaged flow rates (Table S11), divided for the served population of each plant, as detailed in the Supplementary material (Section S1). WWTP-A daily emissions were compared to those measured in a limited monitoring campaign in two WWTPs of Milano. In this way, we compared the pharmaceutical loads of Monza and its county, served by the WWTP-A, with those of Milano, a larger neighboring city, with a special focus on COVID-19-related substances. The comparison of the averaged daily emissions for 1000 inhabitants in the three WWTPs showed that for 9 out of 16 substances the coefficients of variation (CVs) in the three plants were within 30% (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Averaged daily emissions per capita (mg/day/1000 inhabitants) of the quantified compounds, the mean and the coefficient of variation (CV%) of the three WWTPs.

| Compound | WWTP-A |

WWTP-B |

WWTP-C |

Mean |

CV% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg/d/1000 inh | mg/d/1000 inh | mg/d/1000 inh | mg/d/1000 inh | ||

| Acetaminophen | 6877 | 6843 | 10,450 | 8056 | 26 |

| Amisulpride | 4003 | 52 | 58 | 1371 | 166 |

| Carbamazepine | 42 | 50 | 60 | 50 | 18 |

| Darunavir | 77 | 125 | 168 | 123 | 37 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 100 | 34 | 31 | 55 | 70 |

| Irbesartan | 295 | 252 | 318 | 288 | 12 |

| Metoprolol | 23 | 16 | 777 | 272 | 161 |

| Azithromycin | 793 | 295 | 345 | 478 | 57 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1749 | 922 | 920 | 1196 | 40 |

| Clarithromycin | 65 | 84 | 73 | 73 | 13 |

| Erythromycin | 21 | 17 | 16 | 18 | 14 |

| Norfloxacin | 185 | 141 | 223 | 182 | 23 |

| Ofloxacin | 199 | 217 | 172 | 195 | 12 |

| Trimethoprim | 23 | 36 | 34 | 31 | 22 |

| Caffeine | 4458 | 5051 | 5575 | 5027 | 11 |

| Methyl-benzotriazole | 418 | 79 | 90 | 195 | 99 |

Among them, there were caffeine, irbesartan, carbamazepine, which are molecules of daily use and excretion, correlated with the number of people served by the plants. Furthermore, five antibiotics (clarithromycin, erythromycin, norfloxacin, ofloxacin, trimethoprim) together with acetaminophen, had similar emission rates in the monitored WWTPs.

Leaving out the case of methyl-benzotriazole, probably influenced by differences in the dynamics of vehicular traffic and/or the industrial activities, the largest CVs were evidenced for amisulpride and metoprolol, suggesting that in the county of Monza there were sources other than the human excretion. In this case we hypothesize discharges from pharmaceutical industrial plants.

It is interesting to note that some COVID-19-related pharmaceuticals (darunavir, hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin) together with ciprofloxacin showed a marked variability between Monza and Milano (Table 2), which could be explained by a different trend of positive cases even in adjacent geographical areas during the first epidemic peak. Apart from darunavir, which was slightly higher in WWTP-C, the remaining pharmaceuticals were all higher in WWTP-A. In that period the Monza hospital, which discharges its sewage in WWTP-A, mainly admitted patients from the province of Bergamo, one of the most affected areas in Europe, and this fact might explain the higher consumption of certain anti-COVID-19 pharmaceuticals, such as azithromycin and hydroxychloroquine. In order to confirm the hospital contribution, its outlet was monitored every hour in a single day (03/06/2020), collecting four instantaneous samples (from 7 to 10 a.m.) (Table S9). The monitoring results evidenced that hydroxychloroquine had a mean concentration per hour of 0.51 μg/L, with a peak of emission at 8:00 a.m. of 1 μg/L and a decrease in the following hours, confirming that the hospital contributed to WWTP-A influents concentrations (median = 0.22 μg/L). Similarly, azithromycin showed a concentration peak at 8:00 a.m. of 14.8 μg/L and a decrease in the following hours, with a mean concentration per hours of 8.7 μg/L. Ciprofloxacin had noteworthy concentrations too, with an average of 13.1 μg/L within the 4 h, again with a peak at 8:00 a.m. (23.9 μg/L), confirming that hospital was a significant source of this kind of antibiotic, even if it was never recommended in the sanitary protocols as an effective COVID-19 treatment.

The data also confirmed that amisulpride was almost absent in the hospital wastewaters (the highest concentration was 0.20 μg/L, significantly below the detected concentrations in the influents of WWTP-A), supporting the idea that other contamination sources, not related to human consumption, might have affected the emission pattern in WWTP-A.

3.3.1. The hydroxychloroquine case in Italy

From the early stages of the pandemic, the combination of the antibiotic azithromycin and the antimalarial agent hydroxychloroquine, the latter used also as a treatment in some autoimmune diseases, was introduced as a possible treatment for COVID-19 (Gautret et al., 2020; Million et al., 2020). Following the first promising results, at first the Italian Medicines Agency gave the authorization for the off-label use of hydroxychloroquine on March 17th, 2020 but then revoked it on May 26th, 2020 (AIFA, 2020a), in the light of new scientific evidence that demonstrated an increased risk for adverse reactions in the face of little or no benefit (Cavalcanti et al., 2020).

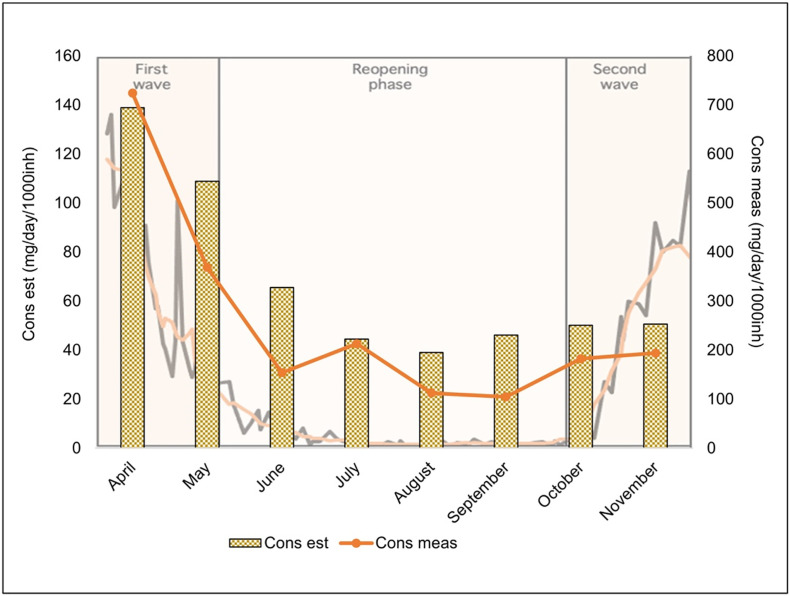

This decision, in line with other international Agencies, such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the European Medicines Agency and the British Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, had immediately animated some controversies, both in Italy and abroad, also as a result of political polarization of this scientific issue (Sanders et al., 2020). Furthermore, the anxiety for the arrival of a second wave has fueled the risk of an improper use of hydroxychloroquine and some cross-border passages finalized to the purchase of hydroxychloroquine abroad were conjectured, especially in our study area which is located only 50 km from the national border. These events have never been ascertained but illegal purchases on websites have been documented. Starting from this scenario and in particular, from the results that we obtained monitoring the WWTP-A during the second wave, we investigated whether there was a correspondence between the influent concentrations and the known hydroxychloroquine consumption. The latter was calculated by the purchase data provided by the Italian Medicines Agency (Table S12), as explained in the Supplementary material (Section S2). Because this is a medicine subjected to a mandatory medical prescription, we estimated the consumption based on the reported purchased packs. The influent concentrations were converted to daily loads normalized for the population (mg/day/1000 inhabitants) and then, the monthly averages were calculated and corrected for the excretion rate of hydroxychloroquine (Browning, 2014). Fig. 4 shows the comparison between the temporal trend of the hydroxychloroquine consumption estimated from the purchase data (Consest) and that estimated from the average loads of the influent samples in WWTP-A (Consmeas). The statistical correlation between the two consumption trends resulted strongly significant (Pearson correlation r = 0.94).

Fig. 4.

Temporal trends of the hydroxychloroquine consumption estimated from the purchase data (Consest) and that estimated from the average loads of the influent samples (Consmeas). In the background it is reported the trend of COVID-19 deaths in Lombardy region (black line) and the weekly average (orange line).

It is interesting to note that during the second wave small peaks in the consumption data as well as in the measured one have been evidenced even if the off-label use was no more authorized.

Our experimental data followed the trend of the buying data but the measured values were 5-fold higher than those estimated from purchase data, so that the illegal purchase of hydroxychloroquine outside the Italian National Health System cannot be excluded. A further partial explanation is that we compared the purchase data of the whole Lombardy region with the chemical results of the county of Monza, which had a higher incidence of infections than the Lombardy. More infected people means a higher consumption of pharmaceuticals used for COVID-19 therapy. Furthermore, as already mentioned, WWTP-A collected the sewage from a hospital that received COVID-19 patients from other highly impacted provinces, where hospitals were already full, and that might have contributed to a higher rate of drug consumption than the whole region.

3.4. Environmental fate and risks of studied substances in the surface waters

As shown in Table 1, some of the monitored pharmaceuticals were statistically correlated with the SARS-CoV-2 disease along the first year of the epidemic. For some of them, such as acetaminophen and amisulpride, the inlet concentrations reached concentrations up to tens of micrograms for liter.

In order to assess the possible impacts on the environment it was necessary to investigate the removal efficiency of the treatment plant by collecting the WWTP-A outlets in the same days.

Since we were not able to carry out a 24-h composite sampling due to the constraints of limited personnel presence in the plant in the lockdown period, we could not rigorously estimate the actual removal efficiency of the plant for those substances. Nevertheless, by simply comparing the inlet and the outlet collected on the same days, as detailed in the Supplementary material (Section S3), we roughly classified the substances in three classes, as removable (class 1), partially removable (class 2) and persistent or recalcitrant compounds (class 3), that is an important information to interpret the environmental fate (Table S13). Persistent compounds (class 3) included amisulpride, metoprolol, carbamazepine, irbesartan and methyl-benzotriazole. Most of the investigated pharmaceuticals, including hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin and darunavir, were partially removed together with other antibiotics (Fig. S5), while few compounds (acetaminophen, caffeine, norfloxacin, lincomycin and ciprofloxacin) were almost completely removed. Nevertheless, acetaminophen and caffeine were present in the inlets at so high concentrations (in the range of tens of micrograms for liter) that the emission from the outlets reached average concentrations of 0.4 and 0.2 μg/L respectively (Table S5), even if the percentage of removal was higher than 99%.

As already shown in Section 3.3 and Table 2 (emission loads), we carried out some short-term sampling campaigns in other two WWTPs of the town of Milano (Fig. 1), in order to get a wider picture on the environmental diffusion of these COVID-19-related pharmaceuticals in the studied area. The removal efficiencies of the three WWTPs were comparable (Tables S6 and S7). On the same samples we determined the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA, as already published (Rimoldi et al., 2020).

The water streams, which receive the discharges of the three plants, were also sampled and analyzed (Fig. 1). The average discharges of these water courses are usually low, being 34 m3/s at R3 and 11 m3/s at R2 sampling stations for Lambro, 1.5 m3/s for Vettabbia Canal at R4 and 23 m3/s for Lambro Meridionale at R5 (Castiglioni et al., 2015); the low dilution of the WWTP outflows increases the vulnerability of the surface waters in the case of an increased load of pharmaceutical during the COVID-19 peak of infections. Furthermore, the presence of caffeine in all samples along the course of river Lambro was a tracer of the inflow of untreated discharges into the surface waters, probably coming from uncollected sewages (Viviano et al., 2017).

We compared our concentrations of eight pharmaceuticals in river Lambro with those determined in the same river in previous studies before the pandemic (Castiglioni et al., 2018; Riva et al., 2019), in order to highlight the differences between the two periods. Average concentrations of clarithromycin, lincomycin, ofloxacin, erythromycin and carbamazepine were within a factor of two compared to the pre-pandemic measurements, while we measured four-times less caffeine, but twenty-times more ciprofloxacin and acetaminophen in the pandemic period respect to the previous data (806 vs 31 ng/L, and 533 vs 24 ng/L for ciprofloxacin and acetaminophen respectively) (Riva et al., 2019).

In order to carry out a preliminary and conservative risk assessment of the presence of pharmaceuticals during the epidemic, we compared the 95th percentile of the concentrations measured in all the surface water dataset (Table S8) with the PNECs and with additional threshold concentrations (PNEC-AR and vEC50) which are informative of a potential risk for the occurrence of antibiotic and antiviral drug resistance (Section 2.7).

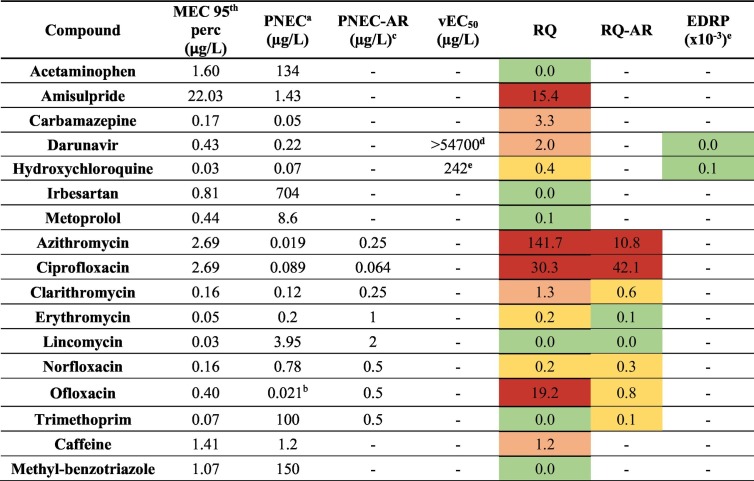

Table 3 shows that, overlooking amisulpride whose source should be better investigated, the highest RQs have been found for the three antibiotics ofloxacin, azithromycin and ciprofloxacin, the last two of which have been used in the COVID-19 treatment; furthermore, carbamazepine, darunavir, clarithromycin and caffeine had RQ > 1.

Table 3.

Risk assessment calculated considering the 95th percentile of the MECs of all the surface waters to obtain different hazard indexes: environmental (RQ = MEC/PNEC), antibiotic resistance (RQ-AR = MEC/PNEC-AR) and antiviral resistance (EDRP) hazards. The colors from green to red are assigned on the basis of increasing risk.

a NORMAN Ecotoxicology Database.

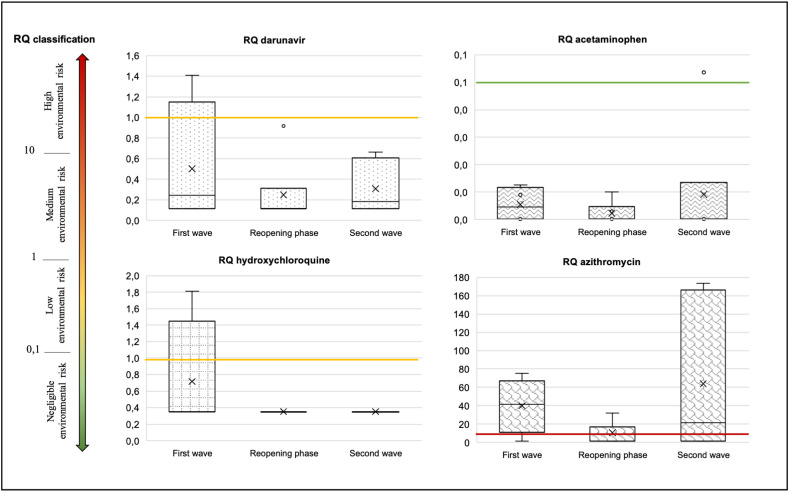

It is interesting to look at the RQs in the different phases of the epidemic calculated in river Lambro downstream (R2) of WWTP-A (Fig. 5 ).

Fig. 5.

Risk quotients (RQs) of the anti-COVID-19 drugs calculated for river samples collected downstream the WWTP-A and grouped on the basis of the three phases of pandemic (from April to December 2020).

It is evident that RQ for acetaminophen was always lower than 0.02, while RQ for azithromycin was always higher than 20, but with a maximum of 170 during the second epidemic peak in the third phase. On the contrary, darunavir and hydroxychloroquine sporadically reached concentrations of ecological risk (RQ > 1), but only in the first phase when tentative treatment protocols for COVID-19 were adopted. Azithromycin and ciprofloxacin reached concentrations of concern also for the development of antibiotic resistance in the natural environments, with RQ-AR > 10, while no risk (RQ-AR < 1) was evidenced for all the other antibiotics determined in this study.

The antiviral agent resistance for SARS-CoV-2 was evaluated for both darunavir and hydroxychloroquine, although the latter is not properly an antiviral compound, exerting only inhibitory activities against the virus. The results of the risk indices (EDRPs) were extremely low, in the order of 10−4–10−6, meaning that the antiviral resistance risk referred to SARS-CoV-2 was extremely low, confirming what Kuroda et al., 2021 had already reported.

4. Conclusions

The sewage surveillance is a powerful tool to complement the monitoring campaigns and to highlight social behaviors and environmental impacts which are often not easily predictable, especially in an emergency period like this related to the COVID-19. The combination with a suspect screening methodology allowed to prioritize and identify drugs in the collected water samples, only by using the exact mass search and then by processing the data on a devoted software for substance identification.

The study of the emission loads of the three WWTPs has evidenced the impressive concentrations of some pharmaceuticals known to be used during the first wave (azithromycin and acetaminophen) as well as ciprofloxacin, which is a fluoroquinolone antibiotic never recommended for COVID-19. In addition, the different emission patterns of the three WWTPs, located in a restricted area, prompted to investigate the impact of the hospital outlet, demonstrating its high contribute to the WWTP inflow of some antibiotics (azithromycin and ciprofloxacin) and hydroxychloroquine, particularly during the first wave. On the contrary, as regards amisulpride, we can exclude a significant contribution from hospital and the dozens of μg/L detected in the influent samples of WWTP-A could be attributed to a presumed industrial source which should be investigated by water managers. This activity is urgent because from the environmental risk assessment of the surface waters, it emerged that this compound is of high environmental concern (RQ = 15). The risk assessment also highlighted that the highest RQs were determined for three antibiotics (azithromycin, ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin) as a result of their release into water bodies after a partial removal by conventional secondary treatments. During the early phase of pandemic there was a significant increase in antibiotic consumption, mainly attributable to improper uses. Surely, in the first pandemic phase the urgency to manage a novel and unknown disease, and to save lives have had the priority over other concerns; nevertheless, now it is strictly necessary to minimize the consumption and even more the abuse of antibiotics and to inform healthcare personnel and consumers about the future risk of developing environmental antibiotic resistance connected with their release into surface waters. In this study, we assessed the risk for the occurrence of antibiotic resistant bacteria under the pressure of high concentrations of azithromycin and ciprofloxacin, demonstrating that it is necessary to include all the biotic components of the aquatic ecosystem in an effective risk assessment scheme.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Francesca Cappelli: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing-original draft preparation, Writing-Reviewing and Editing.

Orietta Longoni: Resources, Supervision.

Jacopo Rigato: Investigation, Methodology, Software.

Michele Rusconi: Investigation, Methodology, Software.

Alberto Sala: Resources, Supervision.

Igor Fochi: Software, Methodology, Data curation, Resources.

Maria Teresa Palumbo: Investigation, Writing-Reviewing and Editing.

Stefano Polesello: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing-original draft preparation, Writing-Reviewing and Editing, Supervision.

Claudio Roscioli: Software, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis.

Franco Salerno: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision.

Fabrizio Stefani: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing-Reviewing and Editing.

Roberta Bettinetti: Supervision, Writing-Reviewing and Editing.

Sara Valsecchi: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing-original draft preparation, Writing-Reviewing and Editing, Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

These activities are part of the Ph.D thesis of Francesca Cappelli in the framework of the collaboration between the Italian Water Research Institute (CNR-IRSA) and the University of Insubria.

We thank all the managers and operators in the studied WWTPs that helped us in the sampling activities notwithstanding the very difficult period.

This work has been carried out under the project CN_00198 “SWaRM-Net – Rete per la gestione intelligente delle risorse idriche”, Program: “Smart Cities and Communities and Social innovation” (D.D.391/Ric del 05/07/2012), funded by Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research (MIUR).

Editor: Damia Barcelo

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153756.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

Supplementary tables

References

- Aalizadeh R., Alygizakis N.A., Schymanski E.L., Krauss M., Schulze T., Ibáñez M., McEachran A.D., Chao A., Williams A.J., Gago-Ferrero P., Covaci A., Moschet C., Young T.M., Hollender J., Slobodnik J., Thomaidis N.S. Development and application of liquid chromatographic retention time indices in HRMS-based suspect and nontarget screening. Anal. Chem. 2021;93:11601–11611. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.1c02348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AIFA Italian Medicines Agency. 2020. https://www.aifa.gov.it/it/-/aifa-sospende-l-autorizzazione-all-utilizzo-di-idrossiclorochina-per-il-trattamento-del-covid-19-al-di-fuori-degli-studi-clinici May 26. (accessed 11.28.21)

- AIFA Italian Medicines Agency. 2020. https://aifa.gov.it/aggiornamento-sui-farmaci-utilizzabili-per-il-trattamento-della-malattia-covid19 (accessed 11.28.21)

- AIFA Italian Medicines Agency. Monitoring of medicinal products used during the COVID-19 epidemic. 2020. https://aifa.gov.it/monitoraggio-uso-farmaci-durante-epidemia-covid-19 (accessed 11.28.21)

- AIFA Italian Medicines Agency. OsMed 2020 National Report on medicines use in Italy. 2020. https://www.aifa.gov.it/en/-/rapporto-nazionale-osmed-2020-sull-uso-dei-farmaci-in-italia (accessed 11.28.21)

- AIFA Italian Medicines Agency. Report “Medicines use in the elderly population in Italy”. 2020. https://www.aifa.gov.it/en/-/presentato-rapporto-uso-farmaci-popolazione-anziana (accessed 11.28.21)

- Alygizakis N., Galani A., Rousis N.I., Aalizadeh R., Dimopoulos M.-A., Thomaidis N.S. Change in the chemical content of untreated wastewater of Athens, Greece under COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;799 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson D.I., Hughes D. Evolution of antibiotic resistance at non-lethal drug concentrations. Drug Resist. Updat. 2012;15:162–172. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandala E.R., Kruger B.R., Cesarino I., Leao A.L., Wijesiri B., Goonetilleke A. Impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on the wastewater pathway into surface water: a review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;774 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao R., Zhang A. Does lockdown reduce air pollution? Evidence from 44 cities in northern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;731 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcelo D. An environmental and health perspective for COVID-19 outbreak: meteorology and air quality influence, sewage epidemiology indicator, hospitals disinfection, drug therapies and recommendations. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020;8 doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2020.104006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Been F., Emke E., Matias J., Baz-Lomba J.A., Boogaerts T., Castiglioni S., Campos-Mañas M., Celma A., Covaci A., de Voogt P., Hernández F., Kasprzyk-Hordern B., ter Laak T., Reid M., Salgueiro-González N., Steenbeek R., van Nuijs A.L.N., Zuccato E., Bijlsma L. Changes in drug use in european cities during early COVID-19 lockdowns – a snapshot from wastewater analysis. Environ. Int. 2021;153 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson-Palme J., Larsson D.G.J. Concentrations of antibiotics predicted to select for resistant bacteria: proposed limits for environmental regulation. Environ. Int. 2016;86:140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binda G., Bellasi A., Spanu D., Pozzi A., Cavallo D., Bettinetti R. Evaluating the environmental impacts of personal protective equipment use by the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a case study of Lombardy (Northern Italy) Environments. 2021;8:33. doi: 10.3390/environments8040033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braga F., Scarpa G.M., Brando V.E., Manfè G., Zaggia L. COVID-19 lockdown measures reveal human impact on water transparency in the Venice Lagoon. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;736 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning D.J. Hydroxychloroquine and Chloroquine Retinopathy. Springer New York; New York, NY: 2014. Pharmacology of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine; pp. 35–63. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cantwell M.G., Sullivan J.C., Burgess R.M. Comprehensive Analytical Chemistry. Elsevier; 2015. Benzotriazoles; pp. 513–545. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castiglioni S., Valsecchi S., Polesello S., Rusconi M., Melis M., Palmiotto M., Manenti A., Davoli E., Zuccato E. Sources and fate of perfluorinated compounds in the aqueous environment and in drinking water of a highly urbanized and industrialized area in Italy. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015;282:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castiglioni S., Davoli E., Riva F., Palmiotto M., Camporini P., Manenti A., Zuccato E. Mass balance of emerging contaminants in the water cycle of a highly urbanized and industrialized area of Italy. Water Res. 2018;131:287–298. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castiglioni S., Schiarea S., Pellegrinelli L., Primache V., Galli C., Bubba L., Mancinelli F., Marinelli M., Cereda D., Ammoni E., Pariani E., Zuccato E., Binda S. SARS-CoV-2 RNA in urban wastewater samples to monitor the COVID-19 pandemic in Lombardy, Italy (March–June 2020) Sci. Total Environ. 2021;150816 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcanti A.B., Zampieri F.G., Rosa R.G., Azevedo L.C.P., Veiga V.C., Avezum A., Damiani L.P., Marcadenti A., Kawano-Dourado L., Lisboa T., Junqueira D.L.M., de Barros e Silva P.G.M., Tramujas L., Abreu-Silva E.O., Laranjeira L.N., Soares A.T., Echenique L.S., Pereira A.J., Freitas F.G.R., Gebara O.C.E., Dantas V.C.S., Furtado R.H.M., Milan E.P., Golin N.A., Cardoso F.F., Maia I.S., Hoffmann Filho C.R., Kormann A.P.M., Amazonas R.B., Bocchi de Oliveira M.F., Serpa-Neto A., Falavigna M., Lopes R.D., Machado F.R., Berwanger O. Hydroxychloroquine with or without azithromycin in mild-to-moderate Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:2041–2052. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2019014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Lei L., Liu S., Han J., Li R., Men J., Li L., Wei L., Sheng Y., Yang L., Zhou B., Zhu L. Occurrence and risk assessment of pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) against COVID-19 in lakes and WWTP-river-estuary system in Wuhan,China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;792 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi P.M., Tscharke B.J., Donner E., O’Brien J.W., Grant S.C., Kaserzon S.L., Mackie R., O’Malley E., Crosbie N.D., Thomas K.V., Mueller J.F. Wastewater-based epidemiology biomarkers: past, present and future. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2018;105:453–469. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2018.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collivignarelli M.C., Abbà A., Bertanza G., Pedrazzani R., Ricciardi P., Carnevale Miino M. Lockdown for CoViD-2019 in Milan: what are the effects on air quality? Sci. Total Environ. 2020;732 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutu S., Rossi L., Barry D.A., Rudaz S., Vernaz N. Temporal variability of antibiotics fluxes in wastewater and contribution from hospitals. PLoS ONE. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cytel Global Coronavirus COVID-19 Clinical Trial Tracker. https://www.covid19-trials.com/ (accessed 12.2.21)

- De Meyer S., Bojkova D., Cinatl J., Van Damme E., Buyck C., Van Loock M., Woodfall B., Ciesek S. Lack of antiviral activity of darunavir against SARS-CoV-2. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;97:7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DrugBank Online Darunavir. https://go.drugbank.com/drugs/DB01264 (accessed 11.25.21)

- DrugBank Online Ritonavir. https://go.drugbank.com/drugs/DB00503 (accessed 11.28.21)

- Dulio V., Koschorreck J., van Bavel B., van den Brink P., Hollender J., Munthe J., Schlabach M., Aalizadeh R., Agerstrand M., Ahrens L., Allan I., Alygizakis N., Barcelo’ D., Bohlin-Nizzetto P., Boutroup S., Brack W., Bressy A., Christensen J.H., Cirka L., Covaci A., Derksen A., Deviller G., Dingemans M.M.L., Engwall M., Fatta-Kassinos D., Gago-Ferrero P., Hernández F., Herzke D., Hilscherová K., Hollert H., Junghans M., Kasprzyk-Hordern B., Keiter S., Kools S.A.E., Kruve A., Lambropoulou D., Lamoree M., Leonards P., Lopez B., López de Alda M., Lundy L., Makovinská J., Marigómez I., Martin J.W., McHugh B., Miège C., O'Toole S., Perkola N., Polesello S., Posthuma L., Rodriguez-Mozaz S., Roessink I., Rostkowski P., Ruedel H., Samanipour S., Schulze T., Schymanski E.L., Sengl M., Tarábek P., Ten Hulscher D., Thomaidis N., Togola A., Valsecchi S., van Leeuwen S., von der Ohe P., Vorkamp K., Vrana B., Slobodnik J. The NORMAN Association and the European Partnership for Chemicals Risk Assessment (PARC): let's cooperate! Environ. Sci. Eur. 2020;32:100. doi: 10.1186/s12302-020-00375-w. (accessed 11.28.21) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durkin M.J., Jafarzadeh S.R., Hsueh K., Sallah Y.H., Munshi K.D., Henderson R.R., Fraser V.J. Outpatient antibiotic prescription trends in the United States: a national cohort study. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2018;39:584–589. doi: 10.1017/ice.2018.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galani A., Alygizakis N., Aalizadeh R., Kastritis E., Dimopoulos M.-A., Thomaidis N.S. Patterns of pharmaceuticals use during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic in Athens, Greece as revealed by wastewater-based epidemiology. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;798 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautret P., Lagier J.-C., Parola P., Hoang V.T., Meddeb L., Sevestre J., Mailhe M., Doudier B., Aubry C., Amrane S., Seng P., Hocquart M., Eldin C., Finance J., Vieira V.E., Tissot-Dupont H.T., Honoré S., Stein A., Million M., Colson P., La Scola B., Veit V., Jacquier A., Deharo J.-C., Drancourt M., Fournier P.E., Rolain J.-M., Brouqui P., Raoult D. Clinical and microbiological effect of a combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in 80 COVID-19 patients with at least a six-day follow up: a pilot observational study. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2020;34 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S., Bornman C., Zafer M.M. Antimicrobial resistance threats in the emerging COVID-19 pandemic: where do we stand? J. Infect. Public Health. 2021;14:555–560. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2021.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godini H., Hoseinzadeh E., Hossini H. Water and wastewater as potential sources of SARS-CoV-2 transmission: a systematic review. Rev. Environ. Health. 2021;36:309–317. doi: 10.1515/reveh-2020-0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullberg E., Cao S., Berg O.G., Ilbäck C., Sandegren L., Hughes D., Andersson D.I. Selection of resistant bacteria at very low antibiotic concentrations. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallema D.W., Robinne F.-N., McNulty S.G. Pandemic spotlight on urban water quality. Ecol. Process. 2020;9:22. doi: 10.1186/s13717-020-00231-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haramoto E., Malla B., Thakali O., Kitajima M. First environmental surveillance for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater and river water in Japan. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;737 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hora P.I., Pati S.G., McNamara P.J., Arnold W.A. Increased use of quaternary ammonium compounds during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and beyond: consideration of environmental implications. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020;7:622–631. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISTAT Rapporto sulla competitività dei settori produttivi - Edizione 2021. 2021;2021 https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/255558 (accessed 11.28.21) [Google Scholar]

- Knight G.M., Glover R.E., McQuaid C.F., Olaru I.D., Gallandat K., Leclerc Q.J., Fuller N.M., Willcocks S.J., Hasan R., van Kleef E., Chandler C.I. Antimicrobial resistance and COVID-19: intersections and implications. eLife. 2021;10 doi: 10.7554/eLife.64139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M., Alamin Md., Kuroda K., Dhangar K., Hata A., Yamaguchi H., Honda R. Potential discharge, attenuation and exposure risk of SARS-CoV-2 in natural water bodies receiving treated wastewater. Npj CleanWater. 2021;4:8. doi: 10.1038/s41545-021-00098-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda K., Li C., Dhangar K., Kumar M. Predicted occurrence, ecotoxicological risk and environmentally acquired resistance of antiviral drugs associated with COVID-19 in environmental waters. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;776 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rosa G., Iaconelli M., Mancini P., Bonanno Ferraro G., Veneri C., Bonadonna L., Lucentini L., Suffredini E. First detection of SARS-CoV-2 in untreated wastewaters in Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;736 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal P., Kumar A., Kumar S., Kumari S., Saikia P., Dayanandan A., Adhikari D., Khan M.L. The dark cloud with a silver lining: assessing the impact of the SARS COVID-19 pandemic on the global environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;732 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langford B.J., So M., Raybardhan S., Leung V., Westwood D., MacFadden D.R., Soucy J.-P.R., Daneman N. Bacterial co-infection and secondary infection in patients with COVID-19: a living rapid review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020;26:1622–1629. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Undeman E., Papa E., McLachlan M.S. High-throughput evaluation of organic contaminant removal efficiency in a wastewater treatment plant using direct injection UHPLC-Orbitrap-MS/MS. Environ. Sci.: Process. Impacts. 2018;20:561–571. doi: 10.1039/C7EM00552K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood A., Eqan M., Pervez S., Alghamdi H.A., Tabinda A.B., Yasar A., Brindhadevi K., Pugazhendhi A. COVID-19 and frequent use of hand sanitizers; human health and environmental hazards by exposure pathways. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;742 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MassBank Europe-Consortium And Its Contributors . Zenodo; 2021. MassBank/MassBank-data: Release Version 2021.03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Medema G., Heijnen L., Elsinga G., Italiaander R., Brouwer A. Presence of SARS-Coronavirus-2 RNA in sewage and correlation with reported COVID-19 prevalence in the early stage of the epidemic in the Netherlands. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020;7:511–516. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]