Abstract

This meta-analysis aims to evaluate the trend, methodological quality and completeness of studies on intracellular delivery of antimicrobial agents. PubMed, Embase, and reference lists of related reviews were searched to identify original articles that evaluated carrier-mediated intracellular delivery and pharmacodynamics (PD) of antimicrobial therapeutics against intracellular pathogens in vitro and/or in vivo. A total of 99 studies were included in the analysis. The most commonly targeted intracellular pathogens were bacteria (62.6%), followed by viruses (16.2%) and parasites (15.2%). Twenty-one out of 99 (21.2%) studies performed neither microscopic imaging nor flow cytometric analysis to verify that the carrier particles are present in the infected cells. Only 31.3% of studies provided comparative inhibitory concentrations against a free drug control. Approximately 8% of studies, albeit claimed for intracellular delivery of antimicrobial therapeutics, did not provide any experimental data such as microscopic imaging, flow cytometry, and in vitro PD. Future research on intracellular delivery of antimicrobial agents needs to improve the methodological quality and completeness of supporting data in order to facilitate clinical translation of intracellular delivery platforms for antimicrobial therapeutics.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11095-022-03188-z.

Keywords: Antimicrobials, Drug carriers, Intracellular drug delivery, Intracellular pathogens

Introduction

Infectious disease and antimicrobial resistance remain a major threat to the public health (1). Of many causative organisms, intracellular pathogens have become a source of great concern worldwide. Intracellular pathogens have developed immune evasion strategies over evolution (2). For example, some pathogens infect macrophages, which are responsible for the eradication of invading pathogens from the host, and rather turn them to their sanctuaries to evade the host immunity (3, 4). Consequently, intracellular infection caused by these organisms can often incur chronic, recurrent, or disseminated infections (5). Repeated and prolonged exposure to antimicrobials also increases the risk of turning these pathogens into multidrug resistant (MDR) or extensively drug resistant (XDR) organisms (6). Given the limited therapeutic options available and the paucity of novel antimicrobial agents in the pipeline, we face dire prospects in the global fight against intracellular infections.

To kill these pathogens, it is necessary to develop new strategies to deliver antimicrobial agents intracellularly. Ideally, antimicrobial therapeutics should selectively enter the infected cells, traffic in the cells to the desired intracellular niche (e.g., cytoplasm or vacuole) harboring pathogens, and kill the pathogens in a timely manner. The drug delivery field has a unique opportunity here, based on the knowledge obtained from the intracellular delivery of anti-cancer drugs or gene therapeutics (e.g., lipid nanoparticles of messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) encoding spike proteins for Coronavirus disease (COVID) vaccines (7)). In particular, gene therapeutics can contribute significantly to the therapy of intracellular infections. For example, viral infections pose further challenges to public health due to the capacity of viruses to spread and rapidly mutate rendering existing antiviral agents ineffective (7, 8). Small interfering ribonucleic acids (siRNAs) are potentially useful for the development of antiviral therapy as they can be designed to adapt to genetic changes in microorganisms and address the affected populations in a timely manner (9). With the approval of mRNA COVID vaccines, we foresee accelerated development of novel products based on advanced antimicrobial agents such as siRNA for therapy of intracellular infections. Therefore, it is a prime time to review current drug carriers targeted to intracellular pathogens and understand the achievements, limitations, and opportunities.

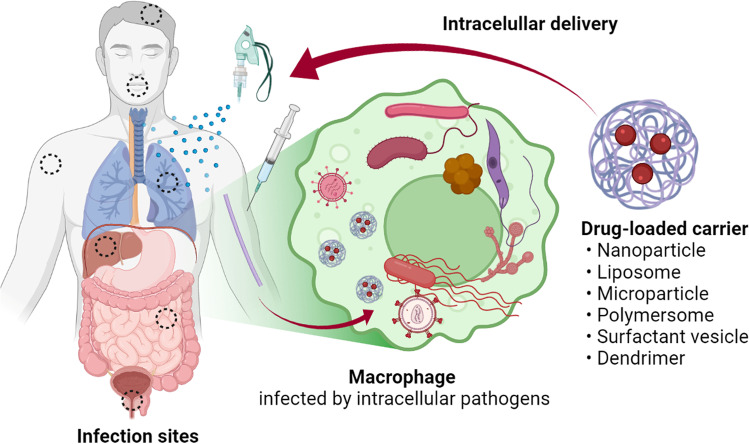

A wide variety of carrier systems have been investigated in the literature, ranging from nanoparticles, microparticles, live cell derivatives, prodrugs, or drug conjugates. Many studies employ particles as a carrier of antimicrobial agents, exploiting the ability of host cells (mostly macrophages) to endocytose them. The particles are made of organic or inorganic compounds that can encapsulate antimicrobial agents, in a size conducive to cellular uptake. Since mammalian cells take up particles via dedicated endocytosis pathways, the encapsulated drugs may bypass diffusional barrier imposed by the cell membrane (10) (Fig. 1). Ninety-nine papers on this topic were published in the past decade, with 89.9% of them in the last 10 years. However, there are only a limited number of commercial products based on the intracellular drug delivery approach, with silver nanoparticles being the most widely studied nanoparticles (11).

Fig. 1.

Intracellular delivery of antimicrobial-loaded carriers. Created with BioRender.com

In this study, we aim to better understand the current landscape of drug delivery systems targeted to intracellular pathogens and potential barriers in their clinical translation. We performed a meta-analysis of literature concerning drug-loaded platforms targeting intracellular pathogens and reviewed study methodologies for evaluating their intracellular delivery and antimicrobial efficacy. Previous meta-analyses on drug-loaded platforms have primarily focused on anticancer therapy (12, 13). To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first meta-analysis on carrier-mediated delivery of antimicrobial therapeutics against intracellular pathogens.

Materials and Methods

Data Source and Search Strategy

A literature search of PubMed and Embase was performed to identify original articles that evaluated carrier-mediated intracellular delivery and/or antimicrobial efficacy of antimicrobial therapeutics against intracellular pathogens in vitro or in vivo. Here, antimicrobial therapeutics are defined broadly to include antiviral, antibacterial, antifungal, and antiparasitic agents. The initial database search strategies were prespecified as follows: search terms consisted of a combination of key words, (intracellular) in title/abstract AND (infection) in title/abstract AND (delivery) in title/abstract; no publication date restrictions were applied; the search filter for language was set as “English.” Reference lists of related research were additionally screened to identify eligible studies. Ethics committee review was waived as this study conducted by pooling existing data extracted from published primary research.

Study Selection and Data Collection

Those studies identified though initial search were screened for eligibility using the following inclusion criteria: (i) experimental data are provided to demonstrate the efficacy of intracellular delivery of antimicrobial therapeutics and/or their antimicrobial efficacy against intracellular pathogens in vitro or in vivo; (ii) carrier systems are used to deliver active drugs; (iii) sufficient raw data can be obtained from primary research. Review articles and duplicate studies were excluded from the meta-analysis. Studies that applied metals or microorganisms for preparation of intracellular delivery platforms were included. Study attributes, including the first author and year of publication, host cells, etiologic organisms, characteristics of carrier, types of materials (organic, inorganic, live cell derivative), active drug, intracellular delivery study methodology, in vitro and/or in vivo pharmacodynamic (PD) markers, antimicrobial efficacy results, and free drug control were extracted utilizing a predefined summary format. Authors resolved difference in opinion or study interpretation through discussion.

Data Analysis and Statistical Methods

The efficacy of intracellular carriers for antimicrobial therapeutics was evaluated qualitatively and quantitatively by pooling data from individual studies, and the results were presented with descriptive statistics. The parameters of intracellular delivery investigation assessed in this meta-analysis included what type of study methodologies were used for evaluation of intracellular delivery (microscopy, flow cytometry), whether in vitro and/or in vivo PD responses were evaluated, and whether the effects were compared against those of free drug counterparts. The primary in vitro PD markers investigated are: intracellular microbial burdens such as colony forming units (CFUs), viral plagues or titers, optical density, and microbial growth or inhibition rates; inhibitory concentrations including minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50), and half maximal effective concentration (EC50). As for in vivo PD markers, survival rates and pathogen burden at specific times were assessed in animal models of related infection.

Results

Selection of Relevant Original Studies

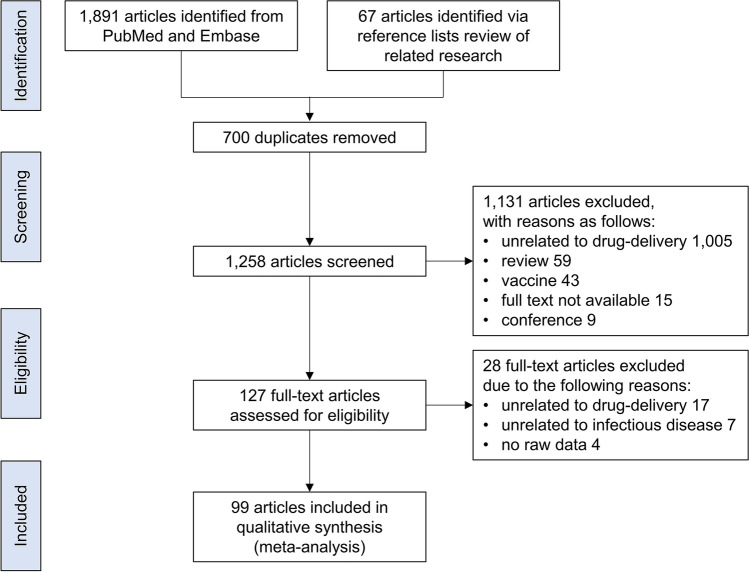

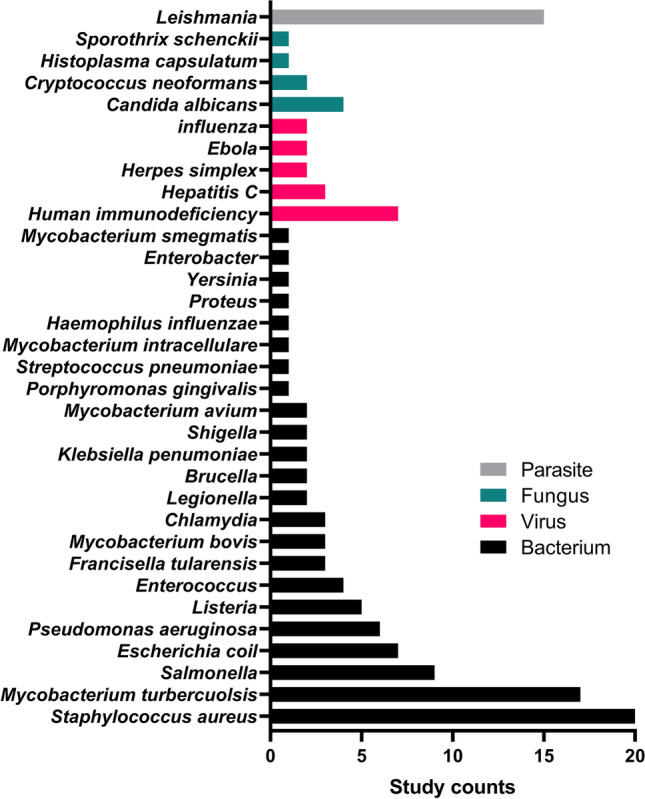

The process of searching and identifying relevant studies is presented as Fig. 2. The initial search from PubMed and Embase yielded 1,891 citations and 67 additional articles were identified via reference lists in reviews of related research (14–17). Of those, 700 duplicates were excluded. Of the remaining 1,258 articles that underwent further screening of titles and abstracts, a total of 1,131 articles were excluded due to the reasons listed in Fig. 2. After full-text review, 28 additional articles were further removed, resulting in 99 studies satisfying the inclusion criteria for qualitative analysis: Bacterial 62 (62.6%), viral 16 (16.2%), fungal 8 (8.1%), and parasitic 15 (15.2%; 2 articles on both bacterial and parasitic pathogens).

Fig. 2.

Study selection flow diagram

Characteristics of Included Studies

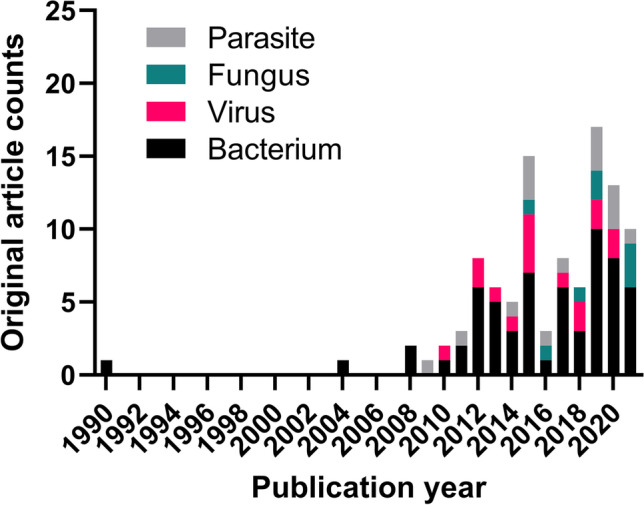

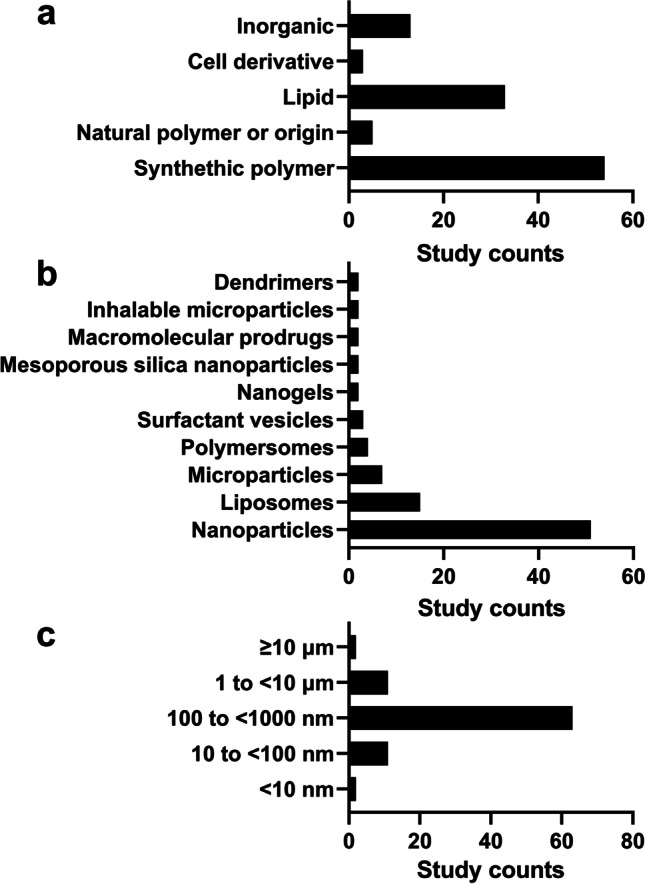

The yearly publication patterns of intracellular delivery of antimicrobial therapeutics show near-zero publications until the late 2000s and a sharp uptake in publication volume in the 2010s and thereafter (Fig. 3). The most commonly targeted intracellular pathogens were bacterial organisms throughout the study screening period, with the first study on Salmonella published in 1990 followed by scarce research until a sharp rise in publication volume in the late 2000s. None of the studies targeted parasitic, viral, or fungal intracellular pathogens until 2009, 2010, and 2015, respectively, with the first studied organism being Leishmania, Ebola, and Cryptococcus, respectively. The most dominant type of materials for delivery platforms was organic compounds, of which 54.5% of studies (54/99) employed synthetic polymers and 33.3% (33/99) lipid particles (Fig. 4a). The most-commonly used carrier type was nanoparticles (in 51 out of 99 studies), followed by liposomes (in 15 out of 99 studies) (Fig. 4b). The particle size in the majority of studies (63.6%) falls in the range of 100 to < 1000 nm (Fig. 4c). We have further analyzed the included studies by host cell types, carrier types, particle size ranges, and administration routes. Detailed results are summarized in Tables S1 to S8 in supplementary materials.

Fig. 3.

Publication trends of the literature focusing on drug delivery systems for the treatment of intracellular infections, subdivided by etiologic organisms

Fig. 4.

Drug carriers used for intracellular delivery of antimicrobials by (a) material types, (b) formulation types, and (c) particle sizes

Bacterial Intracellular Pathogens

The 62 eligible studies on bacterial intracellular pathogens are summarized in Table I. The most commonly studied intracellular bacteria were Staphylococcus aureus (n = 20), followed by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (n = 17) and Salmonella (n = 9) (Fig. 5). There were two studies by Lueth (2019) (18) and by Omolo (2021) (19), which provided the most comprehensive data supporting intracellular delivery and antimicrobial efficacy of drug-loaded carriers both in vitro and in vivo. In the former, a polymer-based nanoparticle was developed to encapsulate doxycycline and rifampicin to eradicate Brucella melitensis or Escherichia coli (18). Intracellular delivery was confirmed by microscopic imaging. In the latter, pH-responsive liposomes were produced to load vancomycin to kill methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (19). Here, intracellular delivery was confirmed by flow cytometry. In both studies, antibacterial activity (changes in MIC and CFU of intracellular bacteria) was compared against those of a free drug control in vitro, where the encapsulated drug showed more efficient bacterial killing than the free drug counterpart. The in vitro results were further validated in mouse models of systemic or topical bacterial infection (CFU changes). The distribution of particles in the main organs of interest (liver and spleen) were determined only in the former study.

Table I.

Characteristics of Intracellular Delivery Studies on Bacterial Pathogens (n = 62)

| Study | Host cell | Etiologic organism | Active drug | Carrier | Carrier material | Size | In vitro PD | In vivo PD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free drug control | Efficacy vs free drug control |

Route | Examined organs | Efficacy vs control |

|||||||

| Afinjuomo 2019 (20) | alveolar macrophages | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | pyrazinamide | microparticles | semicrystalline delta inulin | 1–2 μm | - | - | - | - | - |

| Akbari 2013 (21) | macrophages | Staphylococcus aureus | ciprofloxacin | surfactant vesicles | Span 40, Tween 40, cholesterol | 300–600 nm | + | MIC, 2- to eightfold reduction; intracellular CFU, 3 log reduction | - | - | - |

| Ardekani 2019 (22) | epithelial cell line derived from a human oral squamous cell carcinoma | Porphyromonas gingivalis | metronidazole | nanoparticles | carbon quantum dot derived from chlorophyll | 1–5 nm | + | IC50, 0.33 μM vs 1.02 μM; intracellular CFU, 3 times more reduction | - | - | - |

| Arshad 2021 (23) | macrophages | Salmonella typhi | ciprofloxacin | nanoemulsions | Ciprofloxacin-hyaluronic acid conjugate, oil, surfactant | 40–50 nm | + | sterilization rate based on free CFU, 99.55 ± 0.5% vs 9 ± 3.25% | oral | - | survival, 100% vs 40% |

| Brockman 2017 (24) | cystic fibrosis lung epithelial cells | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | cysteamine | dendrimers | PAMAM-DEN | 4 nm | + |

bacterial growth in free culture, decrease by 15% |

- | - | - |

| Chokshi 2021 (25) | alveolar macrophages | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | rifampicin | lipid nanoparticles | Mannose coating, compritol, stearylamine | 479 ± 13 nm | - | - | oral | lung, spleen, liver | - |

| Chono 2008a (26) | alveolar macrophages |

Chlamydia pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila Pseudomonas aeruginosa Haemophilus influenza |

ciprofloxacin | liposomes | HSPC, cholesterol, DCP | 989.1 ± 94.4 nm | - | - | pulmonary | - | PK/PD analysis for antibacterial effects, increases in AUC/MIC, Cmax/MIC |

| Chono 2008b (27) | alveolar macrophages |

Mycobacterium tuberculsosis, Mycobacterium avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Listeria monocytogenes, Legionella pneumophila, Francisella tularensis |

ciprofloxacin | liposomes |

Mannose coating, HSPC, DOPC, cholesterol, DCP |

1,000 nm | - | - | pulmonary | - | PK/PD analysis for antibacterial effects, increases in AUC/MIC, Cmax/MIC; reduced risk of appearance of resistant bacteria |

| Chuan 2013 (28) | alveolar macrophages | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | rifampicin | lipid nanoparticles |

soybean lecithin, stearic acid, palmic acid |

829.6 ± 16.1 nm | - | - | endotracheal aerosolization | lung | - |

| Clemens 2012 (29) | alveolar macrophages | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | isoniazid, rifampin, moxifloxacin | mesoporous silica nanoparticles | PEG-PEI-coated mesoporous silica nanoparticles | 100 nm | + | free CFU, reduction by 1.5–1.7 log | - | - | - |

| Croitoru 2015 (30) | HeLa cells | Listeria, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli | gentamicin | microcapsules |

exopolysaccharidic fraction from K. pneumoniae and P. aeruginosa strains |

≤ 30 μm | + | intracellular CFU, from increase by 10 logs to reduction by 2–4 logs | - | - | - |

| Das 2017 (31) |

alveolar macrophages |

Franciscella tularensis | ciprofloxacin | macromolecular polymeric prodrugs | PEG methacrylate | - | - | - | endotracheal aerosolization | lung, blood | survival, 75% vs 0% of free drug in lethal aerosol infection model |

| de Faria 2012 (32) |

alveolar macrophages |

Mycobacterium tuberculosis | isoniazid | nanoparticles | PLGA | 180 nm | + | intracellular CFU, reduction by > 1 log | - | - | - |

| Dube 2014 (33) |

alveolar macrophages |

Mycobacterium tuberculosis | rifampicin | nanoparticles | 1,3-β-glucan functionalized chitosan shell, PLGA | 280 nm | + |

fourfold increase in intracellular rifampicin; stimulation of ROS/RNS, pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion (ligand effect) |

- | - | - |

| Ellis 2018 (34) |

alveolar macrophages |

Mycobacterium tuberculosis | rifampicin | multimetallic microparticles (MMPs) | silver, zinc oxide, PLGA | < 4 μm | - |

Intracellular CFU, MMP(Zn), MMP(Ag), or MMP(Ag + Zn) led to a 68 to 76% increase in rifampicin potency (vs blank MMP) |

- | - | - |

| Elnaggar 2020 (35) | macrophages | Shigella flexneri, Salmonella typhimurium, Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus | pexiganan | nanoparticles | silver, PLGA | 603.2 ± 37.3 nm | + | intracellular CFU, reduction by < 3 logs | IV | liver, spleen | - |

| Fahimmunisha 2020 (36) | urothelial cells | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Proteus vulgaris, Klebsiella pneumonia, Escherichia coli urinary tract infection | zinc oxide, Aloe socotrina | nanoparticles | zinc oxide, Aloe socotrina | 15–50 nm | + | zone of inhibition, increase by 10–56% | - | - | - |

| Fenaroli 2020 (37) | macrophages | Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium bovis-BCG, Staphylococcus aureus | vancomycin, gentamicin, lysostaphin, rifampicin, isoniazid | polymersomes | PMPC-PDPA | 100 nm | + | intracellular CFU, reduction by 1 log or complete eradication | IV | Zebrafish macrophage, granuloma | CFU, reduction by 1 log; |

| Fierer 1990 (38) | macrophages | Salmonella dublin | gentamicin | liposomes | partially hydrogenated egg PC, egg PG, cholesterol, α-tocopherol | < 1 μm | - | - | IV | spleen | survival, 80% vs 0% (free drug control) |

| Franch 2020 (39) | macrophages | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | - | nanoparticles | DNA | 300 nm | - | - | - | - | - |

| Gao 2019 (40) | macrophages | Staphylococcus aureus | vancomycin, rifampicin | nanoparticles | PLGA, membrane of S. aureus extracellular vesicle coat | 104.2 nm | + | intracellular CFU, with vancomycin, comparable reduction; with rifampicin, > 1 log reduction | IV | liver, spleen, lung, kidney | CFU, with vancomycin, > 1 log reduction in kidney and lung; with rifampicin, > 1 log reduction in kidney and lung |

| Gaspar 2015 (41) | macrophages | Mycobacterium avium | paromomycin | liposomes | PC, PEG, DMPC, DMPG, DPPC, DPPG, SA | 0.09–0.25 μm | - | - | IV | liver, spleen, lung | bacterial growth index, reduction by 0.5 to 1.75 in lung, liver, spleen |

| Gnanadhas 2013 (42) | macrophages | Salmonella typhimurium, Salmonella typhi | ciprofloxacin, ceftriaxone | nanocapsules | chitosan-dextran sulphate | 180 ± 20 nm | + | intracellular bacterial counts, comparable reduction | IV | liver, spleen | survival, with ceftriaxone 100% vs 50%; with ciprofloxacin 100% vs 40% |

| Heck 2018 (43) | macrophages | Staphylococcus aureus | clindamycin | nanoparticles | zirconyl clindamycin phosphate inorganic–organic hybrid | 73 ± 14 nm | + | intracellular bacterial counts, reduction by 50% in 4 h | - | - | - |

| Hlaka 2017 (44) | macrophages | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | minor groove binders | surfactant vesicles | distamycin template | - | + | intracellular CFU, 1.6- and 2.1-fold increase in anti-mycobacterial activity | - | - | - |

| Horsley 2019 (45) | urothelial cells |

Enterococcus faecalis urinary tract infection |

gentamicin | lipid microbubbles | ultrasound-activated | 5.79 ± 1.53 μm | + | intracellular CFU, reduction by 20% at 15–380 fold lower doses | - | - | - |

|

Hsu 2018 (46) |

alveolar macrophages | Staphylococcus aureus | ciprofloxacin | nanovesicles | Span 60, cholesterol, soybean PC, DSPE-PEG | 114.4 ± 0.9 nm | + | intracellular CFU, reduction by < 1 log | IV | lung | bacterial burden in the lung, decrease by eightfold |

| Imbuluzqueta 2012 (47) | macrophages | Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus | gentamicin as bis(2-ethylhexyl) sulfosuccinate sodium salt | nanoparticles | PLGA | 263 + 10 nm | + | intracellular CFU, reduction by < 1 log with s. aureus; 1–1.5 log with l. monocytogenes | - | - | - |

| Imbuluzqueta 2013 (48) | macrophages | Brucella melitensis | gentamicin as bis(2-ethylhexyl) sulfosuccinate sodium salt | nanoparticles | PLGA | 289–299 nm | + | intracellular CFU, reduction by > 1 log | IV | liver, spleen, kidney | CFU, reduction in splenic infection by 3.13 logs |

| Jankie 2015 (49) | - | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | levofloxacin | surfactant vesicles | cholesterol, sorbitan monostearate, dicetylphosphate | 8–15 μm | - | - | IV | liver, spleen, kidney | CFU/1 μL tissue, reduction by 21.8–4.47; survival, 100% vs 83.3% |

| Kiruthika 2015 (50) | macrophages | Salmonella paratyphi A | chloramphenicol | nanoparticles | Chitosan, dextran sulfate | 100–200 nm | + | MIC, 80 μg/mL vs 3 μg/mL; intracellular CFU, 1 log reduction | - | - | - |

| Labbaf 2013 (51) | urothelial cells | Enterococcus faecalis urinary tract infection | gentamicin | polymeric capsules | polymethylsilsesquioxane | 850 ± 100 nm | + | free CFU, comparable reduction | - | - | - |

| Labouta 2015 (52) | epithelial cells | Yersinia pseudotuberculosis | gentamicin | liposomes | invasin fragment coating, DPPC, cholesterol, other lipid | 143.0 ± 0.4 nm | - | intracellular infection load, reduction by 30% (vs untreated control) | - | - | - |

| Lacoma 2020 (53) | macrophages | Staphylococcus aureus | cloxacillin | nanoparticles | PLGA | 106.5 ± 24 nm | + | MIC, 2- to fourfold reduction; intracellular CFU, reduction by < 1 log | - | - | - |

| Lau 2020 (54) | urothelial cells | Urinary tract infection-related bacteria | nitrofurantoin | microparticles | PLGA | 2.8 μm | + | intracellular CFU, reduction by < 1 log | - | - | - |

| Lee 2016 (55) | macrophages |

Francisella tularensis pneumonia |

moxifloxacin | nanoparticles | mesoporous silica nanoparticles with β-cyclodextrin-adamantyl snap tops | 90 nm | + | intracellular CFU, comparable antibacterial effects | IV | liver, lung, spleen | CFU, reduction by 1 log |

| Lueth 2019 (18) | macrophages | Brucella melitensis, Escherichia coli | doxycycline, rifampicin | nanoparticles | polyanhydrides | 160–330 nm | + | MIC, comparable; intracellular CFU, reduction by > 4 logs | IP | liver, spleen | CFU, reduction by 1–3 logs in spleen |

| Lunn 2021 (56) | alveolar macrophages | Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium bovis-BCG | isoniazid | nanoparticles | P(ManAm-co-DAAm-hydrazone-INH-co-DPAEMA) | 131–280 nm | + | intracellular CFU, reduction by < 1 log | - | - | - |

| Maji 2019 (57) | human embryonic kidney 293 cells as a model | Staphylococcus aureus | vancomycin | nanoparticles | oleylamine, PAMAM-DEN | 124.4 ± 2.01 nm | + | MIC, eightfold reduction; intracellular CFU, reduction by 6 logs | - | - | - |

| Maya 2012 (58) | macrophages, epithelial cells | Staphylococcus aureus | tetracycline | nanoparticles | O-carboxymethyl chitosan | 200 nm | + | MIC, 0.3–0.6 μg/mL vs 0.2–0.4 μg/m; intracellular bacterial killing, sixfold increase in antibacterial effects | - | - | - |

| Mishra 2011 (59) | Hep-2 as model epithelial cells | Chlamydia trachomatis genital infection | azithromycin | nanodevices | PAMAM-DEN | - | + | bacterial inclusion size in cells, 50% reduction vs no measurable reduction | - | - | - |

| Monsel 2015 (60) | monocytes, alveolar epithelial type 2 cells |

Escherichia coli pneumonia |

cell components | microvesicles | mesenchymal stem cell microvesicles | 50–200 nm | - | intracellular CFU, reduction by 25% compared to phosphate-buffered saline | IV | lung | survival, 88% versus 40% with phosphate-buffered saline |

| Montanari 2014 (61) | epithelial cells | Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa | levofloxacin | nanoparticles | hyaluronic acid-cholesterol conjugate | 170 ± 10 nm | + | MIC, 1.7-fold reduction; intracellular CFU, reduction by 80–90% | - | - | - |

| Omolo 2021 (19) | Macrophages, model epithelial cells | Staphylococcus aureus | vancomycin | liposomes | phospholipid, cholesterol, oleic acid, quaternary lipid | 98.88 ± 1.92 nm | + | MIC, 4- to 16-fold reduction; intracellular CFU, reduction by 1–2 logs | IV | - | CFU, 6.33-fold decrease |

| Pei 2017 (62) | macrophages |

Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocytogenes, Enterococcus fecalis, Enterococcus faecium, Streptococcus pneumoniae |

vancomycin | nanoparticles | PEG-PLGA, chitosan derivative | 837 ± 103 nm | + | intracellular CFU, reduction by 0.5–1.5 log | IV | liver, spleen | - |

| Pi 2019 (63) | alveolar macrophages | Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium bovis-BCG | rifampin | nanoparticles | mannosylated and PEGylated graphene oxide | 120 nm | + | intracellular CFU, reduction by 10–50% | - | - | - |

| Prabhu 2021 (64) | macrophages |

Mycobacterium tuberculosis osteoarticular tuberculosis |

rifampicin | nanoparticles | mannose-conjugated chitosan | 130–140 nm | + | MIC, 0.009 μg/mL vs 0.0078 μg/mL | - | - | - |

| Pumerantz 2011 (65) | alveolar macrophages | Staphylococcus aureus | vancomycin | liposomes | DSPC, cholesterol | 254 nm | + | intracellular CFU, reduction by 65% | - | - | - |

| Ranjan 2010 (66) | macrophages | Salmonella typhimurium | gentamicin | nanoparticles | PEO-b-PAA− Na+, PEO-b-PMA− Na+ | 90–120 nm | - | - | IP | liver, spleen | CFU, reduction by -0.15–0.87 log (free drug control) |

| Rodrigues 2021 (67) | alveolar macrophages | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | isoniazid, rifabutin | inhalable polymeric microparticles | chondroitin sulfate | 3.9 μm | - | - | - | - | - |

| Sava Gallis 2019 (68) | macrophages, lung epithelial cells | Escherichia coli | ceftazidime | metal–organic framework particles | zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 | - | - | bacterial growth (optical density), 0 vs 0.4 (untreated control) | - | - | - |

| Smitha 2015 (69) | polymorphonuclear leukocytes | Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella paratyphi A, Enterobacter sp., Klebsiella pneumoniae, Shigella sonnei, Enterococcus faecalis | rifampicin | nanoparticles | amorphous chitin | 350 ± 50 nm | + | MIC, decrease by 0–43% | - | - | - |

| Subramaniam 2019 (70) | macrophages | Staphylococcus aureus | rifampicin | mesoporous silica nanoparticles | mesoporous silica nanoparticles | 40 or 100 nm | + | intracellular CFU, reduction by 30% | - | - | - |

| Uskoković 2014 (71) | osteoblasts |

Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis |

clindamycin | nanoparticles | calcium phosphate | 61.8–83.8 nm | + | intracellular CFU, reduction by 70–100% | - | - | - |

| Vaghasiya 2019 (72) | macrophages | Escherichia coli | no drug | inhalable microspheres | sodium alginate | 5.64–31.51 μm | - | intracellular CFU, reduction by 1 log (vs untreated control) | - | - | - |

| Vieira 2017 (73) | alveolar macrophages | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | rifampicin | lipid nanoparticles | stearylamine, Aerosil, D-( +)-mannose | 302–327 nm | + | intracellular CFU, reduction by < 1 log | - | - | - |

| Vyas 2004 (74) | alveolar macrophages | Mycobacterium smegmatis | rifampicin | liposomes |

egg PC, cholesterol, dicetylphosphate, maleylated BSA, O-steroyl amylopectin |

2.32–3.85 μm | + | intracellular bacterial viability, reduction by 31–84% | pulmonary | lung | - |

| Xiong 2021 (75) | macrophages | Staphylococcus aureus | vancomycin | nanogels | PEG, PCL, polyphosphoester | 429 ± 31 nm | + | intracellular CFU, reduction by 1 log | - | - | - |

| Yang 2015 (76) | macrophages | Staphylococcus aureus | rifapentine | hen egg lipoprotein conjugates | hen egg LDL | 33 ± 6.8 nm | + | intracellular CFU, reduction by 0.5 log | - | - | - |

| Yu 2020 (77) | lung epithelial cells | - | ciprofloxacin, colistin | liposomal powder formulations |

HSPC, DSPG, DSPE-PEG-OMe, cholesterol |

97.1–102.8 nm | - | - | - | - | - |

| Zaki 2012 (78) | enterocytes, macrophages | Salmonella typhimurium | ceftriaxone | nanoparticles | chitosan tripolyphosphate | 202–221 nm | + | intracellular bacterial count, reduction by 99% vs 33–49% | - | - | - |

| Zhang 2017 (79) | osteoblasts | Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis | vancomycin | nanoparticles | N-trimethyl chitosan | 200–325 nm | + | intracellular bacterial count, reduction by > 50% | implanted | - | relative colony count, reduction by 75% (free drug control) |

Intracellular CFU: CFU of intracellular bacteria; free CFU: CFU of free bacteria; free culture: free bacterial culture (no intracellular infection)

Abbreviations: MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; IC50, 50% inhibitory concentration; PAMAM-DEN, polyamidoamine dendrimer; PEG, poly(ethylene glycol); PEI, polyethyleneimine; CFU, colony forming unit; IV, intravenous; HSPC, hydrogenated soybean phosphatidylcholine; DCP, dicetylphosphate; DOPC, dioleoyl phosphatidylcholine; PK/PD, pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamics; AUC, area under the curve; Cmax, maximum concentration; PLGA, poly (lactic acid-co-glycolic acid); MMP, multimetallic microparticle; PMPC-PDPA, poly(2-(methacryloyloxy)ethylphosphorylcholine)-co-poly(2-(diisopropylamino)ethyl methacrylate); PC, phosphatidylcholine; PG, phosphatidylglycerol; DMPC, dimiristoyl phosphatidylcholine; DMPG, dimiristoyl phosphatidylglycerol; DPPC, dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine; DPPG, dipalmitoyl phosphatidylglycerol; SA, stearylamine; ManAm, mannopyran-1-oxyethyl acrylamide; DPAEMA, diisopropylamino ethyl methacrylate; PEGA, poly(ethylene glycol)methyl ether acrylate; IP, intraperitoneal; DSPC, 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; MPEG-2000-DSPE, methylpolyethyleneglycol–1,2-distearoyl-phosphatidyl ethanolamine conjugate; PEO-b-PAA− +Na, poly(ethylene oxide-b-sodium acrylate); PEO-b-PMA− +Na, poly(ethylene oxide-b-sodium methacrylate); CTAB, cetyltrimethylammonium bromide; TEOS, tetraethyl orthosilicate; BSA, bovine serum albumin; PCL, poly(ε-caprolactone); LDL, low-density lipoprotein; DSPG, 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol; DSPE-PEG-OMe, N-(methylpolyyoxyethylene oxycarbonyl)-1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine

Fig. 5.

Commonly studied intracellular pathogens

Viral Intracellular Pathogens

Table II summarizes the 16 intracellular delivery studies of antimicrobial therapeutics targeting viral pathogens. The most commonly studied intracellular viruses were human immunodeficiency virus (n = 7), followed by hepatitis C virus (n = 3) (Fig. 5). A 2018 study by Hu et al. (80) showed the most comprehensive data for intracellular delivery of diphyllin or bafilomycin and their antimicrobial efficacy. The drug was encapsulated in nanoparticles prepared with poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PEG-PLGA) copolymers. Intracellular delivery of the nanoparticles was confirmed microscopically. For in vitro antiviral effects against influenza virus, IC50 and viral titers were compared with those of free drug controls. In an in vivo mouse model of influenza infection, survival rates and viral RNA copies were measured as PD markers. The delivery of intravenously injected particles to the lungs, the organ of interest, was demonstrated based on the reduction of viral loads, but nanoparticle distribution in other organs was not examined.

Table II.

Characteristics of Intracellular Delivery Studies on Viral Pathogens (n = 16)

| Study | Host cell | Etiologic organism | Active drug | Carrier | Carrier material | Size | In vitro PD | In vivo PD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free drug control | Efficacy study vs free drug control |

Route | Examined organs | Efficacy study vs control |

|||||||

| Chandra 2012 (81) | macrophages, liver cells | HCV | siRNA mixture | lipid nanoparticles | cholesterol, DOTAP | 100 nm | - | HCV replication, reduction by 4–6 logs (vs untreated control) | intratumoral, IV | liver tumor xenograft | HCV-RNA levels, reduction by > 2 logs |

| Creighton 2019 (82) | macrophages, lymphocytes | HIV | raltegravir prodrug | nanoparticles | PLGA | - | + | IC50, 2.9–27 nM vs 3.2 nM | - | - | - |

| das Neves 2012 (83) | macrophages, lymphocytes | HIV | dapivirine | nanoparticles | PCL with PEO, SLS, or CTAB as a surface modifier | 182–204 nm | + | EC50, comparable or 4- to 13-fold decrease | - | - | - |

| Donalisio 2020 (84) | Infected cells | HSV | acyclovir | nanodroplets |

chitosan, sulfobutyl ether-β-cyclodextrin |

395.4 ± 12.6 nm | + | IC50, 0.32 μM vs 0.89 μM | - | - | - |

| Geisbert 2010 (85) | Infected cells | EBOV | siRNA | lipid nanoparticles |

cholesterol, dipalmitoyl PC, 3-N-[(ω-methoxy poly(ethylene glycol)2000)carbamoyl]-1,2-dimyrestyloxypropylamine, cationic 1,2-dilinoleyloxy-3-N,Ndimethylamino propane |

81–85 nm | - | - | IV | Liver (mice) | survival, 66–100% vs 0% (untreated control) (rhesus macaques) |

| Gong 2020 (86) | macrophages, lymphocytes | HIV | elvitegravir | nanoparticles | poloxamer-PLGA | 135.7 ± 1.5 nm | + | viral replication, reduction by 80% | - | - | - |

| Guedj 2015 (87) | macrophages, lymphocytes | HIV | protein | nanoparticles | PLGA | 126.30 ± 2.48 nm | - | - | SC | - | - |

| Hillaireau 2013 (88) | macrophages, lymphocytes | HIV | NRTI prodrugs | nanoassemblies | squalene-drug conjugate, cholesterol-PEG, squalene-PEG | 217 ± 47 nm; 204 ± 22 nm | + | ED50, 2- to threefold decrease | oral | liver, spleen, bone marrow | - |

| Hu 2018 (80) | influenza virus | Influenza | diphyllin, bafilomycin | nanoparticles | PEG-PLGA | 178 nm; 197 nm | + | IC50, reduction by 10–43% | IV | lung | survival, 33% vs 0% (empty NP); viral RNA copies, reduction by 1 log |

| Jiang 2015 (89) | macrophages, lymphocytes | HIV | maraviroc, etravirine, raltegravir | nanoparticles | PLGA | 311.2–371.4 nm | + | IC50, 0.40 nM vs 3.2 nM | - | - | - |

| Mandal 2019 (90) | macrophages, lymphocytes | HIV | bictegravir | nanoparticles | PLGA | 189.2 ± 3.2 nm | + | EC50, 0.0038 μM vs 0.604 μM | - | - | - |

| Mazzaglia 2018 (91) | infected cells | HSV | cidofovir | carbon nanotubes | carbon nanotube, cyclodextrin, PEI | 100–300 nm | + | viral plaques, comparable reduction | - | - | - |

| Thi 2015 (92) | infected cells | EBOV | siRNA | lipid nanoparticles | lipid | - | - | Viral RNA copies, reduction by < 1 log (vs untreated control) | IV | - | survival, 100% vs 0% (untreated control); viral load, reduction by 8 logs |

| Timin 2017 (93) | infected cells | Influenza | siRNA | inorganic–organic hybrid capsules | PARG, DEXS, SiO2, CaCO3 | - | - | virus titer, reduction by 50–85% (vs untreated control) | - | - | - |

| Wohl 2014 (94) | macrophages, liver cells | HCV | ribavirin | macromolecular prodrugs | Polymeric drug conjugated to PVP, PHPMA, PAA, or PMAA | - | + | Therapeutic index (IC50/EC50), 4- to eightfold increase | - | - | - |

| Zhang 2015 (95) | macrophages, liver cells | HCV | cationic peptide p41 | peptide-polymer complexes | Gal-terminated PEG-block-poly(L-glutamic acid) copolymer | 108 nm | - | HCV RNA, reduction by 80% (vs untreated control) | IV | liver | - |

Abbreviations: HCV, hepatitis C virus; siRNA, small interfering RNA; DOTAP, 1,2 dioleoyl-3-trymethylammonium-propane; SC, subcutaneous; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PLGA, poly (lactic acid-co-glycolic acid); IC50, 50% inhibitory concentration; PCL, poly(ε-caprolactone); PEO, poloxamer 338 NF; SLS, sodium lauryl sulfate; CTAB, cetyl trimethylammonium bromide; EC50, 50% effective concentration; HSV, herpes simplex virus; EBOV, Ebola virus; PC, phosphatidylcholine; IV, intravenous; NRTIs, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; PEG, polyethylene glycol; ED50, 50% effective dose; Neu2en, 2,3-Didehydro-2-deoxyneuraminic acid; PARG, poly-L-arginine hydrochloride; DEXS, dextran sulfate; TEOS, tetraethyl orthosilicate; NP, nanoparticle; PEI, polyethylenimine; PVP, poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone); PHPMA, poly(N-(2-hydroxypropyl) methacrylamide); PAA, poly(acrylic acid); PMAA, poly(methacrylic acid); APN, antiviral peptide nanocomplex

Fungal Intracellular Pathogens

The 8 studies on fungal intracellular infection are summarized in Table III. The most commonly studied intracellular fungi were Candida albicans (n = 4) (Fig. 5). In an exemplary study by Batista-Duharte (96), a needle-like lipid assembly was prepared to deliver amphotericin B intracellularly to kill Sporothrix schenckii. Microscopic imaging data were provided to confirm intracellular delivery. The in vitro antifungal activity, in terms of CFU and MIC changes, of the carrier-mediated delivery was superior to that of a free drug. The antifungal effects were validated in a mouse model of systemic fungal infection with CFUs as a PD marker. The liver and spleen of the treated animals were examined to evaluate the fungal load.

Table III.

Characteristics of Intracellular Delivery Studies on Fungal Pathogens (n = 8)

| Study | Host cell | Etiologic organism | Active drug | Carrier | Carrier material | Size | In vitro PD | In vivo PD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free drug control | Efficacy study vs free drug control |

Route | Examined organs | Efficacy study vs control |

|||||||

| Batista-Duharte 2016 (96) | macrophages | Sporothrix schenckii | amphotericin B | needle-like lipid assemblies | detoxified LPS-containing lipid | 5–10 μm in length | + | MIC, 0.25 μg/mL vs 1 μg/mL; MFC 0.5 μg/mL vs 2 μg/mL | IP | liver, spleen | CFU, comparable or reduction by < 1 log |

| Cheng 2021 (97) | macrophages | Cryptococcus neoformans | amphotericin B | micro-to-nano systems | BSA-binding MMP-3-responsive peptides, PEG | 115 nm to 7 μm | + | concentration for effective inhibition, 1 μg/mL vs 2 μg/mL | IV | liver, spleen, lung | survival, 70% vs 0% (untreated control); CFU, reduction by 2–3 logs (vs untreated control) |

| Diez-Orejas 2018 (98) | macrophages | Candida albicans | - | nanosheets | PEGylated graphene oxide | 200–600 nm | - | Intracellular CFU inhibition, increase by 5–25% (vs untreated control) | - | - | - |

|

Diez-Orejas 2021 (99) |

macrophages | Candida albicans | - | inorganic nanoparticles |

mesoporous SiO2- CaO |

250 nm | - | - | - | - | - |

| Li 2019 (100) | oral epithelia |

Candida albicans oral candidiasis |

amphotericin B | carbon dots | carbon dots with positively charged guanidine groups | 4.72 ± 1.25 nm | + | MIC, 31.25 μg/mL vs 2.50 μg/mL; biofilm CFU, comparable reduction | - | - | - |

| Mejía 2021 (101) | macrophages | Histoplasma capsulatum | itraconazole | nanoparticles | PLGA core, TPGS coating | 147.3–188.5 nm | + | MIC, 0.061 μg/mL vs 0.031 μg/mL; IC50, comparable: 0.031 μg/mL | - | - | - |

| Shao 2015 (102) | brain capillary endothelial cells |

Cryptococcus neoformans meningitis |

itraconazole | polymeric micelles |

DHA-PEG- pLys-pPhe |

- | - | - | IV | brain | survival, 30% vs 0% (free drug control); CFU, reduction by 2 logs (vs free drug control) |

| Xie 2019 (103) | macrophages | Candida albicans | amphotericin B | cell membrane-coated liposomes | RBC membranes, cationic liposomes, P4.2-derived peptides | 100 nm | + | Fungal growth, comparable | IV | lung | survival, 75% vs 10% (LIP-AmB control); CFU, reduction by > 1 log (vs LIP-AmB control) |

Abbreviations: LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; MFC, minimum fungicidal concentration; IP, intraperitoneal; CFU, colony forming unit; BSA, bovine serum albumin; MMP-3, matrix metalloproteinase 3; PEG, polyethylene glycol; IV, intravenous; PLGA, poly (lactic acid-co-glycolic acid); IC50, 50% inhibitory concentration; DHA, dehydroascorbic acid; RBC, red blood cell; OD630, optical density at 630 nm; LIP-AmB, liposomal amphotericin B

Parasitic Intracellular Pathogens

Table IV summarizes the 15 intracellular drug delivery studies targeting parasitic pathogens. Here, all studies chose Leishmania species as their target pathogen (Fig. 5). Three studies (104–106) incorporated the most comprehensive supporting data. Intracellular delivery of particles was confirmed by microscopy and flow cytometry in all three studies. In vitro killing effects (parasitic burden and IC50 changes) were compared with those of free drug controls. All three studies demonstrated enhanced in vivo parasite inhibition effects of the carrier-mediated delivery versus a free drug. The biodistribution of intravenously injected carrier particles was investigated in two studies, based on drugs delivered to major organs, showing that the liver and spleen were common targets (104, 105).

Table IV.

Characteristics of Intracellular Delivery Studies on Parasitic Pathogens (n = 15)

| Study | Host cell | Etiologic organism | Active drug | Carrier | Carrier material | Size | In vitro PD | In vivo PD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free drug control | Efficacy study vs free drug control |

Route | Examined organs | Efficacy study vs control |

|||||||

| Borborema 2011 (107) | macrophages | Leishmania | meglumine antimoniate | liposomes |

PC, cholesterol, phosphatidylserine |

141.0–142.3 nm | + | IC50, tenfold reduction | - | - | - |

| de Oliveira 2020 (108) | macrophages |

Leishmania cutaneous infection |

quinoxaline derivative | liposomes | hyaluronic acid coating, cholesterol, DOPC, DOPE | 214.1–238.1 nm | + | IC50 on intracellular amastigotes, comparable | IV, topical | liver, spleen | - |

| Fernandes Stefanello 2014 (109) | macrophages | Leishmania | pentenoate derivative | nanogels | hyaluronic acid- poly(DEGMA-co-OEGMA) conjugate | 150–214 nm | - | - | IV | liver, spleen | - |

| Franch 2020 (39) | macrophages, myoblast cells | Leishmania | - | nanoparticles | DNA | 300 nm | - | - | - | - | - |

| Gaspar 2015 (41) | macrophages | Leishmania | paromomycin | liposomes | PC, PEG, DMPC, DMPG, DPPC, DPPG, SA | 90–250 nm | - | - | IV | liver, spleen, lung | parasite burden, 7 log reduction (liver); 2 log reduction (spleen) |

| Gupta 2015 (104) | macrophages | Leishmania | amphotericin B | lipo-polymerosomes | glycol chitosan-stearic acid copolymer, cholesterol, lipoteichoic acid coating | 443.1 ± 17.6 nm | + | IC50 on intracellular amastigotes, 0.082 μg/mL vs 0.295 μg/mL | IV | liver, spleen, lung | parasite inhibition 89.25% vs 56.54% |

| Heidari-Kharaji 2016 (110) | macrophages | Leishmania | Paromomycin | lipid nanoparticles | stearic acid | 120 nm | - | - | IM | lymph node | parasite burden, reduction by > 6 logs (vs free drug control) |

| Jain 2015 (105) | macrophages | Leishmania | amphotericin B | dendrimeric nanoconjugates | mannose-conjugated PPI | - | + | IC50 on intracellular amastigotes, 0.0385 μM vs 0.24 μM; inhibition of parasite, increase by 15% | IV | spleen | inhibition of parasites, 80.16% vs 43.51% |

| Kumar 2019 (111) |

macrophages, neutrophils |

Leishmania | amphotericin B | nanovesicles | macrophage membrane | 100 nm | + | LD50 on intracellular amastigotes, 3- to fourfold reduction | - | - | - |

| Nahar 2009 (112) | macrophages | Leishmania | amphotericin B | nanoparticles | mannose-PEG-PLGA | 157–198 nm | + | percent inhibition of intracellular amastigotes, 87.50% vs 61.77% | - | liver, spleen, lymph nodes | - |

|

Ortega 2021 (113) |

macrophages | Leishmania | maglumine antimoniate | liposomes | EPC, cholesterol, POPS, α-tocopherol | 339.4 ± 10.9 nm | + | infection index on intracellular amastigotes, reduction by 78% vs 43% (at 48 h); 85% vs 56% (at 96 h) | - | - | - |

| Rebouças-Silva 2020 (114) | macrophages | Leishmania | amphotericin B | nanostructured lipid carriers | lipid | 242.0 ± 18.3 nm | + | IC50 on intracellular amastigotes, 11.7 ng/mL vs. 5.3 ng/mL | IP | - | parasite load in infected ears, reduction by 3 logs (vs. liposomal AmB control) |

| Romanelli 2019 (115) | macrophages | Leishmania | sertraline | liposomes | PS, PC, cholesterol | 128 nm | + | EC50 on intracellular amastigotes, 2.5 μM vs 4.2 μM | SC | liver, spleen | parasite burden, reduction by 72–89% (vs untreated control) |

| Sousa-Batista 2019 (116) | macrophages | Leishmania | amphotericin B | microparticles | PLGA | 5.5 μm, 10.3 μm | + | IC50 on intracellular amastigotes, 0.05 μg/mL vs 0.08 μg/mL | SC | - | parasite burden, reduction by 97% (vs free drug control) |

| Want 2017 (106) | macrophages | Leishmania | artemisinin | liposomes | PC, cholesterol | 83 ± 16 nm | + | IC50 on intracellular amastigotes, 6.0 μg/mL vs 15.2 μg/mL; percent infected macrophages, reduction by 10–20% | IP | liver, spleen | percentage inhibition, 82.4% vs 68.3% (liver); 77.6% vs 62.7% (spleen) |

Abbreviations: PC, phosphatidylcholine; IC50, 50% inhibitory concentration; DOPC, 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; DOPE, 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine; IV, intravenous; DEGMA, di(ethylene glycol) methacrylate; OEGMA, oligo(ethylene glycol) methacrylate; PEG, poly(ethylene glycol); DMPC, dimiristoyl phosphatidylcholine; DMPG, dimiristoyl phosphatidylglycerol; DPPC, dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine; DPPG, dipalmitoyl phosphatidylglycerol; SA, stearylamine; SDS, sodium dodecyl sulphate; IM, intramuscular; PPI, poly(propylene imine); LD50, 50% lethal dose; PLGA, poly(lactide-co-glycolide acid); EPC, egg phosphatidylcholine; POPS, palmitoyl oleoyl phosphatidyl serine; IP, intraperitoneal; PS, phosphatidylserine; EC50, 50% effective concentration; SC, subcutaneous; LIP-AmB, liposomal amphotericin B

Study Methodologies: Intracellular Delivery and Antimicrobial Efficacy

We investigated how intracellular drug delivery was evaluated in each study: imaging and flow cytometric analysis of labeled carriers, in vitro PD (e.g., killing of intracellular bacteria or counting viral plaques), or in vivo PD. Table V summarizes study methodologies employed in the analyzed studies. Due to the lack of common readouts and the non-linear relationship of dye concentration versus fluorescence intensity, it was difficult to compare the studies with respect to the intracellular delivery efficiencies of different carriers. As for the intracellular delivery of carriers, 73.7% (73/99) and 37.4% (37/99) of studies performed microscopy and flow cytometry, respectively, and 78.8% (78/99) of them incorporated either of the two methodologies. Twenty-one out of 99 (21.2%) performed neither study to support the intracellular delivery. For the antimicrobial efficacy, 80.8% (80/99) of studies investigated differential effects of drug-loaded carriers on in vitro PD markers as compared to either untreated, empty carrier, or free drug controls. Of those, 69.7% (69/99) of studies compared antimicrobial effects against a free drug control, utilizing either microbial burdens (55/99) or inhibitory concentrations (31/99) or both (17/99) as PD markers. Thirty-three out of 99 (33.3%) studies conducted in vivo PD studies with pathogen burdens or survival as readouts. Eight studies (8.1%) did not show any evidence of intracellular delivery of antimicrobial therapeutics (no microscopic imaging, no flow cytometry, and no in vitro PD study).

Table V.

Study Methodologies Used to Assess Intracellular Delivery and Antimicrobial Efficacy

| Study methodologies | Bacteria (n = 62) |

Virus (n = 16) |

Fungus (n = 8) |

Parasite (n = 15) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intracellular delivery study | ||||

| Microscopy, n (%) | 45 (72.6) | 11 (68.8) | 8 (100.0) | 11 (73.3) |

| Flow cytometry, n (%) | 20 (32.3) | 6 (37.5) | 5 (62.5) | 8 (53.3) |

| Antimicrobial efficacy study | ||||

| In vitro PD, n (%) | 49 (79.0) | 14 (87.5) | 6 (75.0) | 11 (73.3) |

| Microbial burden vs. free drug control, n (%) | 40 (64.5) | 5 (31.3) | 3 (37.5) | 7 (46.7) |

| MIC, IC50 or EC50 vs. free drug control, n (%) | 12 (19.4) | 7 (43.8) | 4 (50.0) | 8 (53.3) |

| Both vs. free drug control, n (%) | 9 (14.5) | 2 (12.5) | 2 (25.0) | |

| In vivo PD, n (%) | 18 (29.0) | 4 (25.0) | 4 (50.0) | 8 (53.3) |

| No evidence of intracellular delivery, n (%) | 7 (11.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (6.7) |

Note: No evidence of intracellular delivery is defined when a study was conducted with neither microscopy/flow cytometry nor in vitro PD

Abbreviations: PD, pharmacodynamics; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; IC50, 50% inhibitory concentration; EC50, 50% effective concentration

Discussion

Intracellular pathogens have evolved to counterbalance the host immunity to survive or multiplicate within macrophages, otherwise hostile environments. In order to treat intracellular infections, it is important to develop an effective intracellular delivery system that helps antimicrobial therapeutics to enter the infected cells, traffic in the cells to the desired intracellular niche harboring pathogens, and kill the pathogens in a timely manner. In this meta-analysis, we performed a descriptive and qualitative evaluation of the studies focused on carrier development for the intracellular delivery of antimicrobial agents. Unlike drug delivery studies in the cancer arena, most intracellular pathogens-targeting studies do not report intracellular drug concentrations, percentage injected dose (%ID) or mg/kg from infected cells or target organs following drug administration. Therefore, not enough raw data were available to perform physiological and pharmacokinetic model-based analyses. Of all the bacterial, viral, fungal, and parasitic intracellular pathogens, bacteria were the most common microbes studied, with Staphylococcus aureus and Mycobacterium tuberculosis being the top two etiologic organisms. They are well known for their ability to acquire antibiotic resistance, and one of the mechanisms behind the resistance is to parasitize macrophages. Notably, Leishmania were the sole species that were chosen as a target pathogen in the parasite category. Leishmaniasis is one of the deadliest infections caused by the obligate intracellular protozoa, by which more than 1.5 million people are newly affected and about 70,000 deaths occur each year (117). It can be transmitted via sand flies, and about 70 animals including humans are known hosts of Leishmania (118). There are other protozoan parasites, such as Toxoplasma gondii and Trypanosoma cruzi, which take advantage of phagocytes to grow, replicate, and evade the host immune system. However, Leishmania species differ from other protozoan parasites in that they predominantly exploit macrophages as host cells (119). Pentavalent antimonial compounds, for example meglumine antimoniate, are the mainstay of treatment but with severe side effects, such as hepatotoxicity and cardiotoxicity (120). Due to the severity of the disease and many challenges that it poses against mammalian populations, there have been a steady and increasing number of studies targeting Leishmania.

Our analysis shows that seventy-four (74.7%) out of 99 studies are done with macrophages (Table S1). The predominance of macrophages as the host cells is attributed to their role in innate immunity as the first defense to the invading bacteria (121). The most common administration route used in in vivo PD studies was intravenous injection (in 25 (58.1%) out of 43 studies) (Table S5). Upon administration, drug-loaded nanocarriers undergo opsonization, distribution in the reticuloendothelial system (RES) organs, and subsequent phagocytic uptake predominantly by macrophages. The particle size in the majority of studies (63.6%) falls in the range of 100 to < 1000 nm (Fig. 4c, Table S3), which is likely driven by the administration route (intravenous injection) and biodistribution in the RES organs where the most infected phagocytes are located (14, 35). The most commonly used carrier type was nanoparticles followed by liposomes, in 51 (51.5%) and 15 (15.2%) out of 99 studies, respectively (Fig. 4b, Table S7), some of which contained mannose or β-glucan ligands to target receptors (e.g., CD206 or Dectin 1) expressed on macrophages.

Most studies (78.8%) provided some proof of intracellular delivery based on microscopic imaging of labeled carriers in the cells or flow cytometric quantitation of cellular fluorescence after incubation with the carriers, but not to the organelle levels: how the carriers traffic in the cells and escape endosomes to finally reach the intracellular niche where the pathogens are hiding. We found that only 31 out of 99 studies provided comparative inhibitory concentrations (MIC, IC50, or EC50) against a free drug control. There were 8 studies that claimed their carrier system was for intracellular delivery of antimicrobial therapeutics but did not provide any experimental evidence supporting such claims, such as microscopic imaging, flow cytometry, and in vitro PD.

While microscopy and flow cytometry are dominant tools to investigate intracellular delivery of carriers, the following limitations need to be considered in interpreting the results. To enable microscopic or flow cytometric detection of carriers, fluorescent dyes are incorporated in the carriers by chemical conjugation or physical encapsulation (122). In the former, the fluorescent signals indicate the carriers (provided that the conjugation is stable throughout the experiment). In the latter, the fluorescent dye is considered a proxy of the delivered drug. Both cases have caveats. It is often assumed that the intracellular delivery of a carrier is synonymous to intracellular delivery of a drug. It is not always the case if the drug is prematurely released before the carrier enters the cells. Drug release profile measured in buffered saline does not warrant stable drug encapsulation since serum proteins can accelerate the drug release (123); therefore, one may not exclude the possibility of premature drug release in vivo on the basis of in vitro release kinetics. On the other hand, when a dye is physically encapsulated in the delivery platform, intracellular fluorescent signal only indicates that the dye can be delivered or released into the cell. While this result may provide a reasonable anticipation that a drug may be able to enter the cells likewise, it cannot be taken for granted since the dye does not always represent physical and chemical properties of the therapeutic agents. Moreover, some of the lipophilic dyes may leach out of carriers and partition to the cell membrane upon the carrier-to-membrane contact, without the carrier entering the cells (122). In this case, the fluorescence-based methods can produce a misleading conclusion about the carrier. Therefore, the results from both methods may not be used as sole evidence for intracellular delivery of drugs. If these methods indicate intracellular delivery of carriers and drug surrogates, additional studies need to be performed with drug-loaded carriers to confirm the intracellular delivery of a drug. For example, drug concentration can be measured in vitro after treating the cells with the drug-loaded carriers. Nevertheless, the entry of drug into cells via the designed carrier does not warrant intracellular trafficking to the target organelles such as endoplasmic reticulum-like vacuoles, late endosomal compartments, and macrophage phagosomes. Therefore, it is preferable to complement with in vitro PD tests, such as intracellular CFU.

To understand the contribution of carriers to intracellular delivery of a drug, control groups need to be selected carefully. When we surveyed the published reports, 69.7% have compared the in vitro antimicrobial efficacy of encapsulated therapeutic agents to the free control. Of these, only 31.3% provided comparative MIC, IC50, or EC50 versus that of the free drug control. Given the potential bioactivity of carriers, it is desirable to include a drug-free carrier and a mixture of drug and drug-free carrier as additional controls. For example, chitosan or fucoidan, one of the commonly used carrier materials, have shown to induce antibacterial activity (124, 125). Without a comparison with an unformulated drug, drug-free carrier, and their mixture, it is difficult to determine whether the enhanced therapeutic efficacy of a carrier-loaded drug is due to the encapsulation and intracellular delivery of the drug or to the additive/synergistic activities of the drug and carrier. Although the blank delivery platform control was not employed as a quality evaluation criterion in this meta-analysis, it would be ideal to include not only free drugs but also drug-free carriers when comparing the PD in future studies.

Our analysis also reveals an access barrier that formulation scientists may face in entering the antimicrobial delivery field. Many organisms of clinical significance require a laboratory with the biosafety level 3 or higher and biocontainment facilities due to the infectious nature of microorganisms (Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Francisella tularensis, Brucella, Ebola, etc.) (126). Non-pathogenic models that share the intracellular residence and drug sensitivity as pathogens of interest will be extremely valuable to drug delivery scientists who intend to assess the effectiveness of delivery systems. For instance, Mycobacterium smegmatis was once considered as a non-pathogenic, fast-growing surrogate of M. tuberculosis (127, 128). Although M. smegmatis was criticized for the differential sensitivity to drugs and stresses and the inability to persist in phagocytes (129), a new strain similar to M. tuberculosis in drug sensitivity has been reported in recent literature (130). We expect that growing availability of such non-pathogenic model organisms will help introduce more investigators into the antimicrobial drug delivery field. Animal models are another bottleneck to the translation of new technology. M. tuberculosis has been studied in various preclinical models, including zebrafish, mice, rabbits, guinea pigs, and nonhuman primates, infected with model organisms (37, 131–136). The sensitivity to infection, immune responses to the pathogens, and the type of lesions vary with animal models; thus, the choice of animal models depends on the purpose of research (131). In the evaluation of new carriers, mouse models are dominantly used for locating the carriers in organ- and cell levels. However, a recent study shows an example using zebrafish to observe in vivo trafficking of polymersomes to M. marinum-infected macrophages and granulomas with the convenience of optical transparency and fluorescent transgenic lines (37). To determine the effectiveness of new delivery technology in cost- and time-efficient manner, it will be important for drug delivery scientists to develop broader understanding of available animal models and their utility and limitations.

Conclusions

Substantial advancements have been made in nanotechnology and precision medicine over the last few decades. The present meta-analysis reviewed the quality of carrier-medicated antimicrobial delivery studies against intracellular pathogens and revealed that several studies lack essential components of PD efficacy studies. To facilitate the clinical translation of antimicrobial products for intracellular targets, future drug delivery research on intracellular pathogens need to consider the utility and limitations of dominant experimental methodologies and improve the rigor of carrier evaluation.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND DISCLOUSURES

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 CA232419, R01 CA258737), Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (No. 2021R1C1C1003735) and by Ajou University re-search fund (S-2021-G0001-00310). The authors report no conflicts of interest in this research.

Abbreviations

- MDR

Multidrug resistant

- XDR

Extensively drug resistant

- mRNA

Messenger ribonucleic acid

- COVID

Coronavirus disease

- siRNA

Small interfering ribonucleic acid

- PD

Pharmacodynamic

- CFUs

Colony forming units

- MIC

Minimum inhibitory concentration

- IC50

Half maximal inhibitory concentration

- EC50

Half maximal effective concentration

- MRSA

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- PEG-PLGA

Poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(lactide-co-glycolide)

- %ID

Percentage injected dose

- RES

Reticuloendothelial system

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sooyoung Shin, Email: syshin@ajou.ac.kr.

Yoon Yeo, Email: yyeo@purdue.edu.

References

- 1.Prestinaci F, Pezzotti P, Pantosti A. Antimicrobial resistance: a global multifaceted phenomenon. Pathog Glob Health. 2015;109(7):309–318. doi: 10.1179/2047773215Y.0000000030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thakur A, Mikkelsen H, Jungersen G. Intracellular Pathogens: Host Immunity and Microbial Persistence Strategies. J Immunol Res. 2019;2019:1356540. doi: 10.1155/2019/1356540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Price JV, Vance RE. The macrophage paradox. Immunity. 2014;41(5):685–693. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell G, Chen C, Portnoy DA. Strategies Used by Bacteria to Grow in Macrophages. Microbiol Spectr. 2016;4(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Price LB, Hungate BA, Koch BJ, Davis GS, Liu CM. Colonizing opportunistic pathogens (COPs): The beasts in all of us. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13(8):e1006369. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Llor C, Bjerrum L. Antimicrobial resistance: risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2014;5(6):229–241. doi: 10.1177/2042098614554919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaudhary N, Weissman D, Whitehead KA. mRNA vaccines for infectious diseases: principles, delivery and clinical translation. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2021;20(11):817–838. doi: 10.1038/s41573-021-00283-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu Z, Li T. Nanoparticle-Mediated Cytoplasmic Delivery of Messenger RNA Vaccines: Challenges and Future Perspectives. Pharm Res. 2021;38(3):473–478. doi: 10.1007/s11095-021-03015-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehta A, Michler T, Merkel OM. siRNA Therapeutics against Respiratory Viral Infections-What Have We Learned for Potential COVID-19 Therapies? Adv Healthc Mater. 2021;10(7):e2001650. doi: 10.1002/adhm.202001650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akinc A, Battaglia G. Exploiting endocytosis for nanomedicines. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5(11):a016980. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mba IE, Nweze EI. Nanoparticles as therapeutic options for treating multidrug-resistant bacteria: research progress, challenges, and prospects. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2021;37(6):108. doi: 10.1007/s11274-021-03070-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng YH, He C, Riviere JE, Monteiro-Riviere NA, Lin Z. Meta-Analysis of Nanoparticle Delivery to Tumors Using a Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling and Simulation Approach. ACS Nano. 2020;14(3):3075–3095. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b08142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barabadi H, Alizadeh A, Ovais M, Ahmadi A, Shinwari ZK, Saravanan M. Efficacy of green nanoparticles against cancerous and normal cell lines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2018;12(4):377–391. doi: 10.1049/iet-nbt.2017.0120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pei Y, Yeo Y. Drug delivery to macrophages: Challenges and opportunities. J Control Release. 2016;240:202–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hussain A, Singh S, Das SS, Anjireddy K, Karpagam S, Shakeel F. Nanomedicines as Drug Delivery Carriers of Anti-Tubercular Drugs: From Pathogenesis to Infection Control. Curr Drug Deliv. 2019;16(5):400–429. doi: 10.2174/1567201816666190201144815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dahanayake MH, Jayasundera ACA. Nano-based drug delivery optimization for tuberculosis treatment: A review. J Microbiol Methods. 2021;181:106127. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2020.106127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Subramaniam S, Joyce P, Thomas N, Prestidge CA. Bioinspired drug delivery strategies for repurposing conventional antibiotics against intracellular infections. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021;177:113948. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2021.113948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lueth P, Haughney SL, Binnebose AM, Mullis AS, Peroutka-Bigus N, Narasimhan B, Bellaire BH. Nanotherapeutic provides dose sparing and improved antimicrobial activity against Brucella melitensis infections. J Control Release. 2019;294:288–297. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Omolo CA, Megrab NA, Kalhapure RS, Agrawal N, Jadhav M, Mocktar C, Rambharose S, Maduray K, Nkambule B, Govender T. Liposomes with pH responsive 'on and off' switches for targeted and intracellular delivery of antibiotics. J Liposome Res. 2021;31(1):45–63. doi: 10.1080/08982104.2019.1686517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Afinjuomo F, Barclay TG, Parikh A, Song Y, Chung R, Wang L, Liu L, Hayball JD, Petrovsky N, Garg S. Design and Characterization of Inulin Conjugate for Improved Intracellular and Targeted Delivery of Pyrazinoic Acid to Monocytes. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Akbari V, Abedi D, Pardakhty A, Sadeghi-Aliabadi H. Ciprofloxacin nano-niosomes for targeting intracellular infections: an in vitro evaluation. J Nanoparticle Res. 2013;15(4).

- 22.Ardekani SM, Dehghani A, Ye P, Nguyen KA, Gomes VG. Conjugated carbon quantum dots: Potent nano-antibiotic for intracellular pathogens. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2019;552:378–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2019.05.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arshad R, Tabish TA, Kiani MH, Ibrahim IM, Shahnaz G, Rahdar A, Kang M, Pandey S. A Hyaluronic Acid Functionalized Self-Nano-Emulsifying Drug Delivery System (SNEDDS) for Enhancement in Ciprofloxacin Targeted Delivery against Intracellular Infection. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2021;11(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Brockman SM, Bodas M, Silverberg D, Sharma A, Vij N. Dendrimer-based selective autophagy-induction rescues DeltaF508-CFTR and inhibits Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0184793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chokshi NV, Rawal S, Solanki D, Gajjar S, Bora V, Patel BM, Patel MM. Fabrication and Characterization of Surface Engineered Rifampicin Loaded Lipid Nanoparticulate Systems for the Potential Treatment of Tuberculosis: An In vitro and In vivo Evaluation. J Pharm Sci. 2021;110(5):2221–2232. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2021.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chono S, Tanino T, Seki T, Morimoto K. Efficient drug delivery to alveolar macrophages and lung epithelial lining fluid following pulmonary administration of liposomal ciprofloxacin in rats with pneumonia and estimation of its antibacterial effects. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2008;34(10):1090–1096. doi: 10.1080/03639040801958421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chono S, Tanino T, Seki T, Morimoto K. Efficient drug targeting to rat alveolar macrophages by pulmonary administration of ciprofloxacin incorporated into mannosylated liposomes for treatment of respiratory intracellular parasitic infections. J Control Release. 2008;127(1):50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chuan J, Li Y, Yang L, Sun X, Zhang Q, Gong T, Zhang Z. Enhanced rifampicin delivery to alveolar macrophages by solid lipid nanoparticles. J Nanoparticle Res. 2013;15(5).

- 29.Clemens DL, Lee BY, Xue M, Thomas CR, Meng H, Ferris D, Nel AE, Zink JI, Horwitz MA. Targeted intracellular delivery of antituberculosis drugs to Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected macrophages via functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(5):2535–2545. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06049-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Croitoru CD, Mihaiescu DE, Chifiriuc MC, Bolocan A, Bleotu C, Grumezescu AM, Saviuc CM, Lazar V, Curutiu C. Efficiency of gentamicin loaded in bacterial polysaccharides microcapsules against intracellular Gram-positive and Gram-negative invasive pathogens. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2015;56(4):1417–1421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Das D, Chen J, Srinivasan S, Kelly AM, Lee B, Son HN, Radella F, West TE, Ratner DM, Convertine AJ, Skerrett SJ, Stayton PS. Synthetic Macromolecular Antibiotic Platform for Inhalable Therapy against Aerosolized Intracellular Alveolar Infections. Mol Pharm. 2017;14(6):1988–1997. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.7b00093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Faria TJ, Roman M, de Souza NM, De Vecchi R, de Assis JV, dos Santos AL, Bechtold IH, Winter N, Soares MJ, Silva LP, De Almeida MV, Bafica A. An isoniazid analogue promotes Mycobacterium tuberculosis-nanoparticle interactions and enhances bacterial killing by macrophages. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(5):2259–2267. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05993-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dube A, Reynolds JL, Law WC, Maponga CC, Prasad PN, Morse GD. Multimodal nanoparticles that provide immunomodulation and intracellular drug delivery for infectious diseases. Nanomedicine. 2014;10(4):831–838. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2013.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ellis T, Chiappi M, Garcia-Trenco A, Al-Ejji M, Sarkar S, Georgiou TK, Shaffer MSP, Tetley TD, Schwander S, Ryan MP, Porter AE. Multimetallic Microparticles Increase the Potency of Rifampicin against Intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis. ACS Nano. 2018;12(6):5228–5240. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b08264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elnaggar MG, Jiang K, Eldesouky HE, Pei Y, Park J, Yuk SA, Meng F, Dieterly AM, Mohammad HT, Hegazy YA, Tawfeek HM, Abdel-Rahman AA, Aboutaleb AE, Seleem MN, Yeo Y. Antibacterial nanotruffles for treatment of intracellular bacterial infection. Biomaterials. 2020;262:120344. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fahimmunisha BA, Ishwarya R, AlSalhi MS, Devanesan S, Govindarajan M, Vaseeharan B. Green fabrication, characterization and antibacterial potential of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Aloe socotrina leaf extract: A novel drug delivery approach. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2020;55.

- 37.Fenaroli F, Robertson JD, Scarpa E, Gouveia VM, Di Guglielmo C, De Pace C, Elks PM, Poma A, Evangelopoulos D, Canseco JO, Prajsnar TK, Marriott HM, Dockrell DH, Foster SJ, McHugh TD, Renshaw SA, Marti JS, Battaglia G, Rizzello L. Polymersomes Eradicating Intracellular Bacteria. ACS Nano. 2020;14(7):8287–8298. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c01870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fierer J, Hatlen L, Lin JP, Estrella D, Mihalko P, Yau-Young A. Successful treatment using gentamicin liposomes of Salmonella dublin infections in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34(2):343–348. doi: 10.1128/AAC.34.2.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Franch O, Gutierrez-Corbo C, Dominguez-Asenjo B, Boesen T, Jensen PB, Nejsum LN, Keller JG, Nielsen SP, Singh PR, Jha RK, Nagaraja V, Balana-Fouce R, Ho YP, Reguera RM, Knudsen BR. DNA flowerstructure co-localizes with human pathogens in infected macrophages. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(11):6081–6091. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao F, Xu L, Yang B, Fan F, Yang L. Kill the Real with the Fake: Eliminate Intracellular Staphylococcus aureus Using Nanoparticle Coated with Its Extracellular Vesicle Membrane as Active-Targeting Drug Carrier. ACS Infect Dis. 2019;5(2):218–227. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.8b00212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gaspar MM, Calado S, Pereira J, Ferronha H, Correia I, Castro H, Tomas AM, Cruz ME. Targeted delivery of paromomycin in murine infectious diseases through association to nano lipid systems. Nanomedicine. 2015;11(7):1851–1860. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2015.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gnanadhas DP, Ben Thomas M, Elango M, Raichur AM, Chakravortty D. Chitosan-dextran sulphate nanocapsule drug delivery system as an effective therapeutic against intraphagosomal pathogen Salmonella. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(11):2576–2586. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heck JG, Rox K, Lunsdorf H, Luckerath T, Klaassen N, Medina E, Goldmann O, Feldmann C. Zirconyl Clindamycinphosphate Antibiotic Nanocarriers for Targeting Intracellular Persisting Staphylococcus aureus. ACS Omega. 2018;3(8):8589–8594. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.8b00637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hlaka L, Rosslee MJ, Ozturk M, Kumar S, Parihar SP, Brombacher F, Khalaf AI, Carter KC, Scott FJ, Suckling CJ, Guler R. Evaluation of minor groove binders (MGBs) as novel anti-mycobacterial agents and the effect of using non-ionic surfactant vesicles as a delivery system to improve their efficacy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72(12):3334–3341. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horsley H, Owen J, Browning R, Carugo D, Malone-Lee J, Stride E, Rohn JL. Ultrasound-activated microbubbles as a novel intracellular drug delivery system for urinary tract infection. J Control Release. 2019;301:166–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hsu CY, Sung CT, Aljuffali IA, Chen CH, Hu KY, Fang JY. Intravenous anti-MRSA phosphatiosomes mediate enhanced affinity to pulmonary surfactants for effective treatment of infectious pneumonia. Nanomedicine. 2018;14(2):215–225. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Imbuluzqueta E, Lemaire S, Gamazo C, Elizondo E, Ventosa N, Veciana J, Van Bambeke F, Blanco-Prieto MJ. Cellular pharmacokinetics and intracellular activity against Listeria monocytogenes and Staphylococcus aureus of chemically modified and nanoencapsulated gentamicin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(9):2158–2164. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Imbuluzqueta E, Gamazo C, Lana H, Campanero MA, Salas D, Gil AG, Elizondo E, Ventosa N, Veciana J, Blanco-Prieto MJ. Hydrophobic gentamicin-loaded nanoparticles are effective against Brucella melitensis infection in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(7):3326–3333. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00378-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jankie S, Johnson J, Adebayo AS, Pillai GK, Pinto Pereira LM. Efficacy of Levofloxacin Loaded Nonionic Surfactant Vesicles (Niosomes) in a Model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infected Sprague Dawley Rats. Adv Pharmacol Pharm Sci. 2020;2020:8815969. doi: 10.1155/2020/8815969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kiruthika V, Maya S, Suresh MK, Kumar VA, Jayakumar R, Biswas R. Comparative efficacy of chloramphenicol loaded chondroitin sulfate and dextran sulfate nanoparticles to treat intracellular Salmonella infections. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2015;127:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Labbaf S, Horsley H, Chang MW, Stride E, Malone-Lee J, Edirisinghe M, Rohn JL. An encapsulated drug delivery system for recalcitrant urinary tract infection. J R Soc Interface. 2013;10(89):20130747. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2013.0747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Labouta HI, Menina S, Kochut A, Gordon S, Geyer R, Dersch P, Lehr CM. Bacteriomimetic invasin-functionalized nanocarriers for intracellular delivery. J Control Release. 2015;220(Pt A):414–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lacoma A, Uson L, Mendoza G, Sebastian V, Garcia-Garcia E, Muriel-Moreno B, Dominguez J, Arruebo M, Prat C. Novel intracellular antibiotic delivery system against Staphylococcus aureus: cloxacillin-loaded poly(d, l-lactide-co-glycolide) acid nanoparticles. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2020;15(12):1189–1203. doi: 10.2217/nnm-2019-0371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lau WK, Dharmasena D, Horsley H, Jafari NV, Malone-Lee J, Stride E, Edirisinghe M, Rohn JL. Novel antibiotic-loaded particles conferring eradication of deep tissue bacterial reservoirs for the treatment of chronic urinary tract infection. J Control Release. 2020;328:490–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee BY, Li Z, Clemens DL, Dillon BJ, Hwang AA, Zink JI, Horwitz MA. Redox-Triggered Release of Moxifloxacin from Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles Functionalized with Disulfide Snap-Tops Enhances Efficacy Against Pneumonic Tularemia in Mice. Small. 2016;12(27):3690–3702. doi: 10.1002/smll.201600892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lunn AM, Unnikrishnan M, Perrier S. Dual pH-Responsive Macrophage-Targeted Isoniazid Glycoparticles for Intracellular Tuberculosis Therapy. Biomacromolecules. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Maji R, Omolo CA, Agrawal N, Maduray K, Hassan D, Mokhtar C, Mackhraj I, Govender T. pH-Responsive Lipid-Dendrimer Hybrid Nanoparticles: An Approach To Target and Eliminate Intracellular Pathogens. Mol Pharm. 2019;16(11):4594–4609. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.9b00713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maya S, Indulekha S, Sukhithasri V, Smitha KT, Nair SV, Jayakumar R, Biswas R. Efficacy of tetracycline encapsulated O-carboxymethyl chitosan nanoparticles against intracellular infections of Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Biol Macromol. 2012;51(4):392–399. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]