Abstract

Members of the genus Francisella and the species F. tularensis appear to be genetically very similar despite pronounced differences in virulence and geographic localization, and currently used typing methods do not allow discrimination of individual strains. Here we show that a number of short-sequence tandem repeat (SSTR) loci are present in F. tularensis genomes and that two of these loci, SSTR9 and SSTR16, are together highly discriminatory. Labeled PCR amplification products from the loci were identified by an automated DNA sequencer for size determination, and each allelic variant was sequenced. Simpson's index of diversity was 0.97 based on an analysis of 39 nonrelated F. tularensis isolates. The locus showing the highest discrimination, SSTR9, gave an index of diversity of 0.95. Thirty-two strains isolated from humans during five outbreaks of tularemia showed much less variation. For example, 11 of 12 strains isolated in the Ljusdal area, Sweden in 1995 and 1998 had identical allelic variants. Phenotypic variants of strains and extensively cultured replicates within strains did not differ, and, for example, the same allelic combination was present in 55 isolates of the live-vaccine strain of F. tularensis and another one was present in all 13 isolates of a strain passaged in animals. The analysis of short-sequence repeats of F. tularensis strains appears to be a powerful tool for discrimination of individual strains and may be useful for a detailed analysis of the epidemiology of this potent pathogen.

Francisella tularensis is the etiological agent of tularemia, a disease affecting many mammalian species including humans, rodents, and lagomorphs. Rodents and lagomorphs are highly susceptible to the disease and often die from the infection. These animals are believed to be a source of infection for other mammals, and the disease is transmitted to humans via vectors such as ticks or mosquitoes. F. tularensis isolates are highly infectious, and a bite by a vector may be sufficient to establish human infection (4).

Tularemia occurs over the whole Northern Hemisphere, and areas with a rather high incidence of the disease exist in Scandinavia, Russia, and United States. The most virulent F. tularensis isolates belong to the subspecies tularensis, and before the introduction of effective antibiotic treatment, human infections caused by such strains resulted in a mortality rate of up to 30% (5, 14). Although this subspecies was formerly believed confined to the United States, recent studies have reported its occurrence in Europe as well (9). Virtually all European isolates belong to the subspecies holarctica, and although such isolates may cause severe disease and are highly infectious, they rarely result in human mortality. F. tularensis subsp. holarctica strains exist in North America as well. Japanese F. tularensis strains belong to the subspecies holarctica, while those from Central Asia constitute a separate subspecies, F. tularensis subsp. mediaasiatica (25). There are only a few known isolates of the fourth subspecies, F. tularensis subsp. novicida (25). All have been linked to water and may cause disease in compromised individuals (3).

Although its subspecies differ dramatically in virulence, F. tularensis appears to be a genetically homogenous species. Recent taxonomic work has aimed to develop molecular tools for discrimination of the four recognized subspecies and individual strains. This work has been successful insofar as it has allowed discrimination between the two most important subspecies from a clinical standpoint, subspecies tularensis and holarctica, but none of the developed methods allow high discrimination of individual strains (6, 11, 15). Thus, there is a need for better methods for the studies of the relationships of F. tularensis strains.

An ongoing project is aimed to sequence the genome of a prototypical isolate of F. tularensis subsp. tularensis, Schu S4. This work is more than 98% complete, and a thorough analysis of the genome is therefore possible. We used the sequence information to identify short-sequence repeats. Such repeats appear to exist in variable numbers in many prokaryotic genomes and, since they are rapidly evolving, have shown promise for discrimination of individual strains (29). We identified eight short-sequence tandem repeats in the F. tularensis genome. Two loci, each containing a unique repeat, showed high allelic variation. A typing method based on the allelic variation of the two loci is shown to be superior for discrimination of F. tularensis isolates compared to previously used methods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria, media, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains (Table 1) all belong to the Francisella strain collection of approximately 250 Francisella strains and have been tested for specific agglutination and examined by PCR specific for a gene encoding an Francisella-specific 17-kDa lipoprotein (24). In addition, they have been biochemically characterized, with the exception of a few recently isolated Swedish strains. The strains included in the study encompassed 39 nonrelated F. tularensis isolates representing each of the four subspecies, 32 isolates from five human tularemia epidemics, 55 replicates of a strain serially passaged on solid media, and 13 replicates of a strain isolated after passages in mice, guinea pigs, or alpine hare (21) (Table 1). All strains were characterized also by use of a PCR assay based on primers C1 and C4, which identifies F. tularensis subsp. holarctica strains (15). Bacteria were grown for 2 days on modified Thayer-Martin agar plates (23) at 37°C under 5% CO2, harvested by scraping, suspended in saline at a concentration of 109/ml, and heat killed at 65°C for 2 h. The cell suspensions were stored at −20°C until used.

TABLE 1.

F. tularensis strains used in this study

| Species and origin (no. of strains) | FSC no. | Alternative strain designation | Size (bp) of:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9-bp SSTR | 16-bp SSTR | |||

| F. tularensis subsp. holarctica | ||||

| Human, Aänekoski, Finland | 249 | 1468 | 288 | 361 |

| Tick, 1949, Moscow area, Russia | 257 | 503/840 | 360 | 361 |

| Human outbreak, 1997, Oulu, Finland (6) | 396–414 | 361 | ||

| Human ulcer, 1984, Norway | 097 | 83933/84 | 288 | 361 |

| Hare, 1984, Finland | 080 | SVA T13 | 288 | 361 |

| Tick, 1953, Norway | 032 | Norway | 288 | 361 |

| Human, 1996, Piteå, Sweden | 188 | 288 | 361 | |

| Human outbreak 1998, Ljusdal, Sweden (6) | 297–306 | 361 | ||

| Hare, 1952, France | 025 | Chateauroux | 297 | 361 |

| Human, 1993, Vosges, France | 247 | SVA T20 | 297 | 361 |

| Human outbreak, 1995, Ljusdal, Sweden | 297 | 361 | ||

| Ticks, 1995, Czech Republic | 180 | T-17 | 306 | 361 |

| Human outbreak, 1981, Ljusdal, Sweden (7) | 297–351 | 361 | ||

| Norway rat, 1988, Rostov, Russia | 150 | 250 | 333 | 361 |

| Live vaccine strain, Russia | 155 | ATCC 29684 | 351 | 361 |

| Water, 1990, Odessa region, Ukraine | 124 | 14588 | 360 | 361 |

| Human blood, 1989, Norway | 089 | 45F2 | 360 | 361 |

| Tick, 1941, Montana | 012 | 425F4G | 369 | 361 |

| Beaver, 1976, Hamilton, Mont. | 035 | B423A | 378 | 361 |

| Hare, 1974, Västerdalälven, Sweden | 074 | SVAT7 | 315 | 361 |

| Human blood, 1994, Örebro, Sweden | 157 | CCUG 33270 | 387 | 361 |

| Human, 1999, Karlstad, Sweden | 236 | 396 | 361 | |

| Human epidemic, 1995, Västerdal River, Sweden (6) | 315–414 | 361 | ||

| Human lymph node, 1926, Japan | 017 | Jap-S2 | 234 | 393 |

| Human, 1950, Japan | 022 | Ebina | 234 | 393 |

| Tick, 1957, Japan | 075 | Jama | 234 | 393 |

| Human, 1958, Japan | 021 | Tsuchiya | 234 | 457 |

| F. tularensis subsp. mediaasiatica | ||||

| Tick, 1982, Central Asia, former USSR | 148 | 240 | 432 | 361 |

| Miday gerbil (Meriones meridianus), 1965, Kazakhstan | 147 | 543 | 459 | 361 |

| Hare, 1965, Central Asia, former USSR | 149 | 120 | 450 | 361 |

| F. tularensis subsp. tularensis | ||||

| Squirrel, Georgia “CDC standard” | 033 | SnMF | 360 | 425 |

| Tick, 1935, British Columbia, Canada | 041 | Vavenby | 378 | 489 |

| Human pleural fluid, 1940, Ohio | 046 | Fox Downs | 459 | 409 |

| Mite, 1988, Slovakia | 198 | SE-219/38 | 369 | 505 |

| Mite, 1988, Slovakia | 199 | SE-221-38 | 468 | 505 |

| Human ulcer, 1941, Ohio (2 variants) | 043, 237 | Schu, Schu S4 | 432 | 617 |

| Canada | 042 | Utter | 279 | 345 |

| Human lymph node, 1920, Utah | 230 | ATCC 6223 | 279 | 345 |

| Hare, 1953, Nevada | 054 | Nevada 14 | 351 | 345 |

| Human ulcer, laboratory acquired when handling Nevada 14 | 053 | F. tul AC | 351 | 345 |

| F. tularensis subsp. novicida | ||||

| Water, 1950, Utah | 040 | ATCC 15482 | 486 | NAa |

| Human blood, 1991, Texas | 156 | Fx1 | 585 | NA |

| F. philomiragia Muscrat, 1959, Utah | 144 | ATCC 25015 | NA | NA |

NA, no amplicons were generated under the conditions used.

Tularemia epidemics.

Strains from epidemics occurring in areas along the rivers Ljusnan and Västerdalälven in central Sweden in 1981, 1995, and 1998 and from an area surrounding the city of Oulu in northern Finland in 1997 were received from laboratories which had performed the primary isolation. The isolation had been performed by (i) the Swedish Defense Research Agency; (ii) the Swedish Institute for Infectious Disease Control, Stockholm, Sweden; or (iii) the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory, Oulu University Hospital, Oulu, Finland. All strains were further characterized by our laboratory to ascertain the species to which they belonged. For each epidemic, the suspected locations where infection had been contracted were at most 50 km apart. Cases associated with the same epidemic occurred within a period of at most 2 months, with the exception of the Oulu outbreak, where isolation dates encompassed 1 year. The area of Västerdalälven is located at latitude 60.5° and longitude 14.5°, Ljusdal is located at latitude 61.8° and longitude 16.1°, and Oulu is located at latitude 65.2° and longitude 25.5°. The distance from Ljusdal to Västerdalälven is 180 km, and the distance from Ljusdal to Oulu is 650 km.

Identification of repetitive elements.

At present, the genome of the Schu S4 strain of F. tularensis subsp. tularensis is being sequenced. Our analysis was based on a total of 1.9 million bases, estimated to represent >98% of the total genome. By use of the REPuter Program developed at the University of Bielefeld, Bielefeld, Germany, we searched for regions with repeated sequences of a total length of more than 15 bp (18).

Primers and PCR amplifications.

Primers were designed to allow amplification of eight regions with short-sequence tandem repeats (SSTR). After an initial evaluation of 10 strains, representing each of the four F. tularensis subspecies, the two SSTR regions with the highest discriminatory ability were further analyzed. The following primer pairs were used: 5′-GTTTTCACGCTTGTCTCCTATCA-3′ (SSTR9F) plus 5′-CAAAAGCAACAGCAAAATTCACAAA-3′ (SSTR9R), and 5′-GTTGGCGAACCTAAAATAATAGC-3′ (SSTR16F), plus 5′-CAGCTCGAACTCCGTCATAC-3′ (SSTR16R). PCR was performed in a total volume of 25 μl. The PCR mixture contained 1 μl of bacterial supernatant, an 0.8 μM concentration of (each) forward and reverse primer (MWG-Biotech AG, Ebersberg, Germany), 1 U of DyNAzyme DNA polymerase (Finnzymes OY, Espoo, Finland), and a 200 μM concentration of (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphate in the buffer provided by the polymerase manufacturer. An initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min was followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 62°C (SSTR9) or 60°C (SSTR16) for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 30 s, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were stained with ethidium bromide and visualized on 3% NuSieve 3:1 agarose gels (FMC BioProducts, Rockland, Maine) in an initial evaluation of allele variability.

Allele size determination and sequencing.

The SSTR9 and SSTR16 regions of the F. tularensis strains were amplified as described above, with a 5′-end labeling of one primer using 6-FAM (MWG Biotech AG). Size determination was performed on an ABI 377XL DNA Sequencer (PE Applied Biosystems, Stockholm, Sweden). PCR products were diluted 1:5, and 1 μl was loaded plus 1.5 μl of GeneScan-1000 size standard and loading buffer, on a nondenaturating 6.5% polyacrylamide gel. Separation was performed at 30°C for 8 h. Data collection and analysis were done using filter set D and GeneScan analysis software (PE Applied Biosystems). Unlabeled PCR products of the SSTR9 (29 strains) and SSTR16 (12 strains) regions were purified by MicroSpin S-400HR columns (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) and sequenced using the amplification primers and the Big Dye terminator cycle-sequencing ready reaction kit (PE Applied Biosystems).

Statistical analysis.

Discriminatory power, i.e., the average probability of the typing system to assign a different type to two randomly selected unrelated strains, was assessed by use of Simpson's index of diversity as proposed by Hunter and Gaston (10).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The SSTR9 and SSTR16 regions of F. tularensis subsp. tularensis strain Schu S4 have been assigned GenBank accession no. AF356777 and AF357005, respectively.

RESULTS

Allelic variation of repetitive elements.

The analysis of 1.9 million bases of the Schu S4 genome revealed eight discrete loci of short-sequence tandem repeats that occurred in at least four copies. Primers were constructed that annealed to conserved sequences upstream and downstream of selected repeats, thereby allowing the determination of the total size of the region and providing an indirect estimate of the number of repeats. This analysis was performed for eight loci of 10 F. tularensis strains, with all subspecies represented among the strains. Most of these loci showed limited or no variation among strains of the subspecies holarctica, mediaasiatica, and novicida. Only one analyzed element showed good discrimination of strains of all subspecies, and this 9-bp repeat appeared in highly variable numbers in the genomes. The Schu S4 strain contained 25 copies. Within 10 F. tularensis subsp. tularensis strains, besides the 9-bp repeat, a 16-bp repeat showed the highest variation, and 18 copies were present in the Schu S4 strain.

Analysis of the region containing the SSTR9 element.

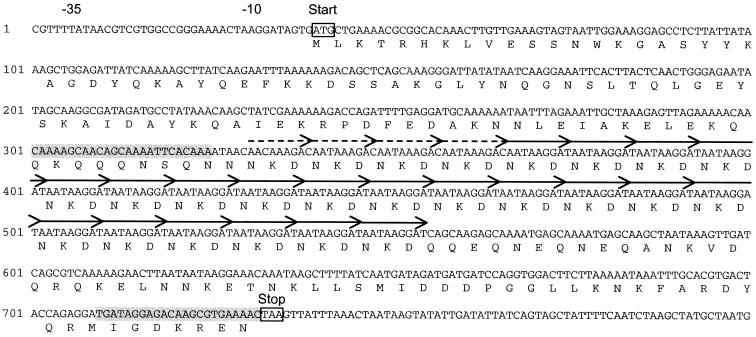

A region containing the 9-bp SSTR was sequenced (Fig. 1). It was localized within an open reading frame (ORF) encoding a putative protein of 231 amino acids in the Schu S4 strain (F. tularensis subsp. tularensis). A GenBank Blastx search identified homology to a putative protein of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (GenBank accession no. AE004731; E value, 7 × 10−11; 33 of 78 identical amino acids). PCR amplification of the region containing the repetitive element in different F. tularensis strains showed that its size ranged from 234 to 585 bp. Sequencing of the region from 29 strains showed that four sequence variants of the 9-bp repeat existed and that the repeats were always localized in tandem, hence the designation SSTR9 (short-sequence tandem repeat with 9 nucleotides). Interestingly, the variability did not affect the encoded amino acid (Table 2). In the sequenced SSTR9 alleles of the 29 strains, there were correlations between repeat variants and subspecies; i.e., some repeats were found only in some subspecies but in all sequenced alleles of the subspecies. Moreover, the sequencing revealed that each of the variants of the 9-bp repeats were arranged in tandem and that the tandem regions were always arranged in the order A, B, C, D, and E (designations as indicated in Table 2).

FIG. 1.

DNA sequence of the SSTR9 locus. The locus is located in an ORF of the Schu S4 strain. The putative start and stop codons are boxed. Locations of PCR primers are shaded. The 9-bp tandem repeats are indicated by arrows; broken lines indicate sequence heterogeneity of the 9-bp SSTR.

TABLE 2.

Sequence heterogeneity of the 9-bp SSTR does not alter the encoded amino acidsa

| Variants of 9-bp tandem repeats encoding amino acids Asn-Lys-Asp | Designationb | No. of tandem repeats found in the 9-bp locus | Presence in all strains of subspecies: |

|---|---|---|---|

| AACAAAGAC | SSTR9A | 1–6 | tularensis, holarctica, and novicida |

| AATAAAGAC | SSTR9B | 1–3 | tularensis and novicida |

| AACAAAGAT | SSTR9C | 1 | mediaasiatica |

| AATAAAGAT | SSTR9D | 1–24 | mediaasiatica and novicida |

| AATAAGGAT | SSTR9E | 2–26 | All |

The alleles were sequenced in strains belonging to subspecies tularensis (n = 6), holarctica (n = 19), mediaasiatica (n = 2), and novicida (n = 2).

Designations SSTR9A to SSTR9E refer to the sequence variants of the 9-bp repeat. The variants were each arranged in tandem, and these tandem regions always appeared in the order A, B, C, D, and E.

Analysis of the region containing the SSTR16 element.

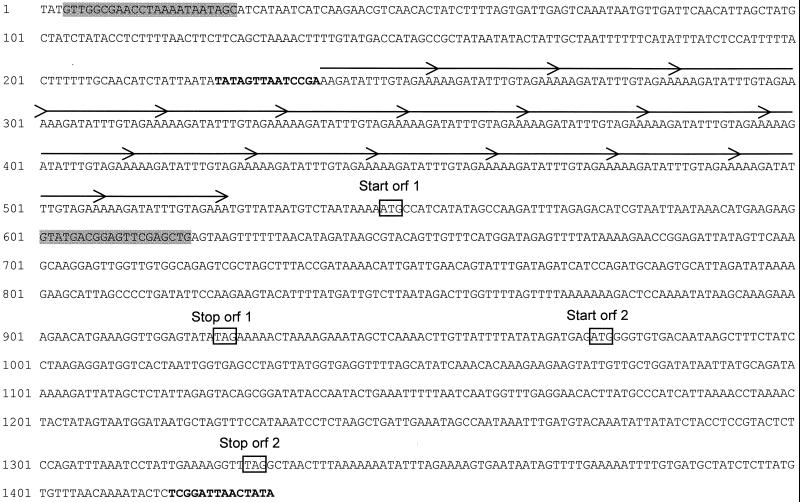

A 16-bp SSTR was identified in multiple loci of the genome sequence, and each 16-bp repeat was part of a larger repetitive element resembling an IS element. In the current assembly of the Schu S4 genome, 35 identical IS elements containing 2 to 18 copies of the 16-bp repeat were found. After an initial evaluation of 10 loci (data not shown), a locus containing 18 copies in tandem, designated SSTR16, was found to be the most discriminatory and was selected for further analysis (Fig. 2). The 1,208-bp IS element of this locus contained two open reading frames encoding putative proteins of 126 (ORF1) and 118 (ORF2) amino acids. A GenBank Blastx search identified homology of ORF2 to a transposase of Aspergillus niger (GenBank accession no. AAB50684; E value, 1 × 10−15; 48 of 120 identical amino acids).

FIG. 2.

Sequence of the SSTR16 region in the Schu S4 strain. The 16-bp direct repeats are marked by arrows and are present in 18 copies. Primer positions are shaded. The direct repeats are located inside an IS element; terminal inverted repeats of the IS element are shown in boldface. Thirty-five copies of the IS elements have been identified in the current assembly of the Schu S4 genome, each containing 2 to 18 copies of the 16-bp tandem repeat.

The 16-bp tandem repeats were located in a noncoding region adjacent to a 14-bp inverted repeat at one end of the putative F. tularensis transposon. PCR amplification of the SSTR16 region from different F. tularensis strains showed that its size ranged from 345 to 617 bp. No sequence heterogeneity of the 16-bp direct repeat was observed by sequencing of PCR products from 12 strains.

Variability of the SSTR9 and SSTR16 loci among F. tularensis strains.

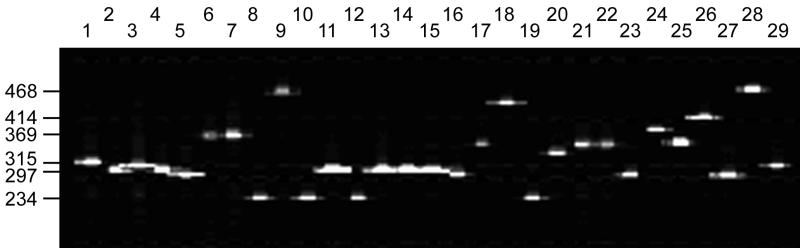

PCR amplification was performed on samples from each strain by using labeled primers, and amplicons were analyzed for size by electrophoresis on nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels. A representative electrophoretic analysis of the SSTR9 PCR amplicons is shown in Fig. 3. The size range and sequencing of the SSTR9 locus showed that it contained a minimum of 3 and a maximum of 43 copies whereas the SSTR16 locus contained a minimum of 1 and a maximum of 18 copies of the respective SSTR. The amplicon sizes are summarized in Table 1. The SSTR9 locus showed a high allelic variation, and if the strains listed in Table 3 are excluded from the calculation because of their epidemiological relationship, Simpson's index of diversity was 0.95 based on results from 39 unrelated strains.

FIG. 3.

Representative electrophoretic analysis of PCR fragments of the SSTR9 loci from different isolates of F. tularensis. Fragments were detected by fluorescence on an ABI 377XL DNA sequencer. Strains of each of the four subspecies are represented; F. tularensis subsp. tularensis in lanes 7 (FSC198), 9 (FSC199), and 17 (FSC054); F. tularensis subsp. holarctica nonrelated European and North American isolates in lanes 1 (FSC176), 3 (FSC180), 4 (FSC247), 5 (FSC188), 6 (FSC012), 14 (FSC025), 16 (FSC032), 20 (FSC150), 21 (FSC076), 22 (FSC155), 23 (FSC080), 24 (FSC157), 25 (FSC089), 26 (FSC161), and 27 (FSC097), isolates from Ljusdal, Sweden, 1995 and 1998 in lanes 2 (FSC245), 11 (FSC200), 13 (FSC201), 15 (FSC202), and 29 (FSC102), and nonrelated Japanese isolates in lanes 8 (FSC017), 10 (FSC021), 12 (FSC022), and 19 (FSC075); F. tularensis subsp. mediasiatica in lane 18 (FSC149); and F. tularensis subsp. novicida in lane 28 (FSC040). Allele sizes (in base pairs) are indicated to the left.

TABLE 3.

Variation of the SSTR9 types in epidemic or passages of F. tularensis strainsa

| Origin | Yr of isolation | No. of isolates | Source | SSTR9 allele sizes (bp) | No. of allelic variants of SSTR9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human epidemic, Oulu area, Finland | 1996–1997 | 7 | Ulcer, pleural fluid, blood | 396–414 | 3 |

| Human epidemic, Ljusdal area, Sweden | 1981 | 7 | Ulcer | 297–351 | 3 |

| Epizootic in hares, Ljusdal area, Sweden | 1981 | 1 | Autopsy | 351 | 1 |

| Human epidemic, Ljusdal area, Sweden | 1995 | 6 | Ulcer | 297 | 1 |

| Human epidemic, Ljusdal area, Sweden | 1998 | 6 | Ulcer | 297–306 | 2 |

| Human epidemic along the river Västerdalälven, Sweden | 1995 | 6 | Ulcer | 315–414 | 3 |

| Phenotypic variants of Schu strain (Schu and Schu S4), originally a human isolate | 1941 | 2 | Ulcer | 432 | 1 |

| Rabbit isolate (Nevada 14) and laboratory-acquired infection (F. tul. AC) from handling the isolate | 1953 and 1954 | 2 | Autopsy of hare and human ulcer | 351 | 1 |

| Passages of LVS (ATCC 29684) on agar medium | 55 | 351 | 1 | ||

| Passages of hare isolate (FSC074) in small mammals | 1974 | 13 | Autopsy | 315 | 1 |

Schu strain, Nevada 14, and F. tul. AC belong to F. tularensis subsp. tularensis; all other isolates belong to F. tularensis subsp. holarctica.

The SSTR16 region was present in only two allelic variants in the F. tularensis subsp. holarctica and mediaasiatica strains, whereas it was highly discriminatory among F. tularensis subsp. tularensis strains. Simpson's index of diversity for this locus was 0.42. If the discriminatory power of the two loci was combined, the index of diversity was 0.97.

No allelic variation was observed in extensively cultured replicates within strains (Table 3). Of 55 replicates of the live-vaccine strain of F. tularensis subjected to repeated passages on agar medium over a period of 3 months, all had identical allelic variants of SSTR9 and SSTR16 (Table 3). Analysis of 13 isolates from 7 passages of strain FSC074 in mice, guinea pigs, and hares showed no allelic variation and no sequence heterogeneity. The strain was originally isolated in Sweden from a hare. Similarly, the prototypical F. tularensis subsp. tularensis strain, Schu, and the laboratory-derived smooth variant, Schu S4, contained the same allelic combination (Table 3). Moreover, a rabbit isolate of F. tularensis subsp tularensis and an isolate subsequently cultured from a laboratory worker infected with the same strain (2) had an identical allelic combination that was not present in any other analyzed strain (Table 3).

The analysis of strains from outbreaks that occurred in the Ljusdal area of Sweden in 1981, 1995, and 1998 showed that only three allelic variants were represented among the 18 strains and at most two variants were present in each outbreak (Tables 3 and 4). The presumed location where infection had been contracted was within an area of 10 km along the river Ljusnan. A detailed summary of the allelic variants is shown in Table 4. All except one strain showed an identical allelic combination from the outbreaks in 1995 and 1998. The only aberrant strain contained an allelic variant identical to the one found in most strains from the 1981 outbreak. During the latter outbreak, one strain was isolated with an allelic variant different from that in all other human isolates from Ljusdal but identical to that in an isolate from a dead hare found in the Ljusdal area the same year.

TABLE 4.

Allelic variation of SSTR9 of F. tularensis strains from Ljusdal, Sweden, isolated at different times

| Allele size (bp) | Allelic variation for strains

isolated ina:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1981 | 1995 | 1998 | |

| 297 | ● | ●●●●●● | ●●●●● |

| 306 | ●●●●● | ● | |

| 351 | ●○ | ||

Each human isolates is shown as a solid circle, and an isolate from a hare is shown as an open circle.

Isolates from Ljusdal showed a closer relationship than did isolates from an area along the river Västerdalälven in Sweden. In the latter case, the allele sizes were 315, 315, 405, 414, 414, and 414 bp (Table 3). The cases occurred in locations up to 50 km apart. The six isolates from the Oulu area in Finland showed three allelic variants (Table 3). In this case, the times of isolation varied over a period of more than 1 year. The size of the allelic variants varied from 396 to 414 bp. The cases occurred in locations to 50 km apart.

DISCUSSION

Our previous work showed that F. tularensis strains display a very limited genetic diversity, despite their varied geographical origin and wide variation in virulence, and this has hampered the development of useful tools for studies of the epidemiology of the pathogen. Restriction enzyme cleavage or sequence analysis of 16S rRNA genes demonstrated that the four subspecies could be discriminated, but individual strains could not be (6, 11). A recent study evaluated the application of PCR based on the use of various arbitrary primers or primers specific to repetitive extragenic palindromic or enterobacterial repetitive intragenic consensus sequences (15). It was concluded that the methods were useful for rapid analysis and may be a technically simple strategy for discrimination of subspecies but not of individual strains. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis has become the standard for typing of many bacterial species (27). The method has, however, not allowed much discrimination of F. tularensis strains within the same subspecies (A. Johansson and A. Sjöstedt, unpublished data). Thus, there is a need for methods that allow discrimination of individual strains.

A recent development in molecular typing is based on the analysis of short-sequence repeats in prokaryotic genomes. The repeats may be a result of replication slippage and, although they are more infrequent in prokaryotic than in eukaryotic genomes, appear to be present in variable and often relatively large numbers (31). In many cases their role is obsolete, but recent studies show that they may regulate antigenic variation of, for example, virulence-associated genes and that their presence within genes may contribute to the coding potential of the messenger or the level of translation efficiency (29). Amplification of regions containing variable numbers of repeat elements has formed a basis for successful typing of individual strains from a variety of pathogens such as Escherichia coli (20), Haemophilus influenzae (30), Staphylococcus aureus (28), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (7, 17), Mycobacterium africanum (8), Helicobacter pylori (19), Yersinia pestis (1), and Bacillus anthracis (12, 16, 22).

Our findings show that typing of Francisella strains based on the analysis of SSTR is the method with the highest resolution tested so far. The repeats differ between strains of the same subspecies, and when the combined variability of the repeats was assessed, Simpson's index of diversity was 0.97. Therefore, it is the first method used for typing of F. tularensis strains that fulfills the recommended criterion, ≥0.95, for routine typing of individual isolates (26). The relevance of the index requires that the test population reflect the diversity of the investigated species. We consider that our strain collection fulfills this criterion since the isolates originated from all relevant regions of the Northern Hemisphere and all four subspecies of F. tularensis are represented. The usefulness of the markers for epidemiological analyses of strains is supported by the finding that the allelic variants were not affected by extensive culturing in vitro or by passages in laboratory animals.

Despite the high discriminatory power of the method, we observed that epidemiologically related Scandinavian strains, i.e., strains isolated from a relatively confined area during a period of 2 months, contained the same or a few alleles of SSTR9. Moreover, the size variation of the SSTR9 allele was small in the related strains, only 9 bp in a majority of the strains from Ljusdal and at most 18 bp in the strains from Oulu. This may indicate that the strains from each epidemic, although containing distinct SSTR9 alleles, were genetically closely related. Moreover, it indicates that the same or similar clones of F. tularensis may persist in a geographically confined area, as supported by the finding that 18 of 20 strains from Ljusdal isolated during a period of 17 years differed in allele sizes by at most 9 bp. In Scandinavia, transmission to humans occurs predominantly in late summer or early autumn. If there is a persistence of clones of bacteria for years in various regions, this indicates that the seasonal outbreaks of tularemia occurring in Scandinavia are due to specific climatic conditions.

The copy number polymorphism of the SSTR9 locus, in particular; indicates that repeated insertions and deletions of repeats occur among F. tularensis isolates and is suggestive of a slipped-strand mispairing that create and maintain directly repeated sequences (31). A functional role of the repeat is implied by the conservation present at the first and second codon positions in all of the sequenced strains, whereas the point mutations that obviously occur in the third codon position may be allowed due to their minor effect on protein structure.

Despite a limited diversity within the genomes of various bacterial species, several recent studies on, for example, Y. pestis (1) and B. anthracis (13, 16) show that even in such genomes, variable numbers of repetitive elements exist that evolve rapidly and thus show great discriminatory power. In this respect, the results of the studies are analogous to our findings with Francisella. The discrimination of F. tularensis strains was, however, considerably higher than that for Y. pestis or B. anthracis strains. With regard to B. anthracis isolates, Keim et al. suggested that strains of different geographical origins may show identical allelic variants since clones have been dispersed worldwide due to human activities (16). In the case of Y. pestis, typing based on a tetranucleotide repetitive element appear to yield a more limited discrimination since the same allelic variant was present in strains of different biovars.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that the analysis of short-sequence repeats is a powerful tool to understand the relationship of F. tularensis strains and may become an important tool for a detailed analysis of the epidemiology of the pathogen. The role of the Francisella short-sequence repeats is not understood, and it will be important to determine their biological significance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Grant support was obtained from the Swedish Medical Research Council, Samverkansnämnden Norra Sjukvårdsregionen, Umeå, Sweden, and the Medical Faculty, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden.

We thank Pentti Koskela, Irma Ikäheimo, Ralfh Wollin, Roland Matsson, Lennart Berglund, Jill Clarridge, Darina Gurycova, and Gunnar Sandström for providing strains and/or epidemiological information; Ulla Eriksson for maintaining the Francisella strain collection; and Jan Karlsson for helping with sequence analyses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adair D M, Worsham P L, Hill K K, Klevytska A M, Jackson P J, Friedlander A M, Keim P. Diversity in a variable-number tandem repeat from Yersinia pestis. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1516–1519. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.4.1516-1519.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell J F, Owen C R, Larson C L. Virulence of bacterium tularense. 1. A study of the virulence of bacterium tularense in mice, guinea pigs, and rabbits. J Infect Dis. 1955;97:162–166. doi: 10.1093/infdis/97.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarridge J E, III, Raich T J, Sjöstedt A, Sandström G, Darouiche R O, Shawar R M, Georghiou P R, Osting C, Vo L. Characterization of two unusual clinically significant Francisellastrains. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1995–2000. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.8.1995-2000.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cross J T, Penn R L. Francisella tularensis (tularemia) In: Mandell G L, Bennet J E, Dolin R, editors. Mandell, Douglas and Bennet's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 5th ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, Pa: Churcill Livingstone, Inc.; 2000. pp. 2393–2402. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dienst F T. Tularemia. A perusal of three hundred thirty-nine cases. J Louisiana State Med Soc. 1963;115:114–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forsman M, Sandström G, Sjöstedt A. Analysis of 16S ribosomal DNA sequences of Francisellastrains and utilization for determination of the phylogeny of the genus and for identification of strains by PCR. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:38–46. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-1-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frothingham R, Meeker-O'Connell W A. Genetic diversity in the Mycobacterium tuberculosiscomplex based on variable numbers of tandem DNA repeats. Microbiology. 1998;144:1189–1196. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-5-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frothingham R, Strickland P L, Bretzel G, Ramaswamy S, Musser J M, Williams D L. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of Mycobacterium africanumisolates from West Africa. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1921–1926. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1921-1926.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gurycova D. First isolation of Francisella tularensis subsp. tularensisin Europe. Eur J Epidemiol. 1998;14:797–802. doi: 10.1023/a:1007537405242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunter P R, Gaston M A. Numerical index of the discriminatory ability of typing systems: an application of Simpson's index of diversity. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:2465–2466. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.11.2465-2466.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ibrahim A, Gerner-Smidt P, Sjöstedt A. Amplification and restriction endonuclease digestion of a large fragment of genes coding for rRNA as a rapid method for discrimination of closely related pathogenic bacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2894–2896. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.2894-2896.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jackson P J, Hugh-Jones M E, Adair D M, Green G, Hill K K, Kuske C R, Grinberg L M, Abramova F A, Keim P. PCR analysis of tissue samples from the 1979 Sverdlovsk anthrax victims: the presence of multiple Bacillus anthracisstrains in different victims. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1224–1229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson P J, Walthers E A, Kalif A S, Richmond K L, Adair D M, Hill K K, Kuske C R, Andersen G L, Wilson K H, Hugh-Jones M, Keim P. Characterization of the variable-number tandem repeats in vrrA from different Bacillus anthracisisolates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1400–1405. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.4.1400-1405.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jellison W L. Tularemia In North America, 1929–1974. Missoula: University Of Montana; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johansson A, Ibrahim A, Göransson I, Eriksson U, Gurycova D, Clarridge J E, Sjöstedt A. Evaluation of PCR-based methods for discrimination of Francisella species and subspecies and development of a specific PCR that distinguishes the two major subspecies of Francisella tularensis. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:4180–4185. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.11.4180-4185.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keim P, Price L B, Klevytska A M, Smith K L, Schupp J M, Okinaka R, Jackson P J, Hugh-Jones M E. Multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis reveals genetic relationships within Bacillus anthracis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2928–2936. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.10.2928-2936.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kremer K, van Soolingen D, Frothingham R, Haas W H, Hermans P W, Martin C, Palittapongarnpim P, Plikaytis B B, Riley L W, Yakrus M A, Musser J M, van Embden J D. Comparison of methods based on different molecular epidemiological markers for typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosiscomplex strains: interlaboratory study of discriminatory power and reproducibility. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2607–2618. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2607-2618.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurtz S, Schleiermacher C. REPuter: fast computation of maximal repeats in complete genomes. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:426–427. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.5.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marshall D G, Coleman D C, Sullivan D J, Xia H, O'Morain C A, Smyth C J. Genomic DNA fingerprinting of clinical isolates of Helicobacter pyloriusing short oligonucleotide probes containing repetitive sequences. J Appl Bacteriol. 1996;81:509–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1996.tb03540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Metzgar D, Thomas E, Davis C, Field D, Wills C. The microsatellites of Escherichia coli: rapidly evolving repetitive DNAs in a non-pathogenic prokaryote. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39:183–190. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mörner T. Ph.D. thesis. Uppsala, Sweden: Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences and the Division of Wildlife the National Veterinary Institute; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patra G, Vaissaire J, Weber-Levy M, Le Doujet C, Mock M. Molecular characterization of Bacillusstrains involved in outbreaks of anthrax in France in 1997. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3412–3414. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3412-3414.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandström G, Tärnvik A, Wolf-Watz H, Löfgren S. Antigen from Francisella tularensis: nonidentity between determinants participating in cell-mediated and humoral reactions. Infect Immun. 1984;45:101–106. doi: 10.1128/iai.45.1.101-106.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sjöstedt A, Kuoppa K, Johansson T, Sandström G. The 17 kDa lipoprotein and encoding gene of Francisella tularensis LVS are conserved in strains of Francisella tularensis. Microb Pathog. 1992;13:243–249. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(92)90025-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sjöstedt, A. Family XVII. Francisellaceae, genus I. Francisella. In D. J. Brenner (ed.), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, in press. Springer-Verlag, New York, N.Y.

- 26.Struelens M J the Members of the European Study Group on Epidemiological Markers (ESGEM), of the European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) Consensus guidelines for appropriate use and evaluation of microbial epidemiologic typing systems. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1996;2:2–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1996.tb00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tenover F C, Arbeit R D, Goering R V. How to select and interpret molecular strain typing methods for epidemiological studies of bacterial infections: a review for healthcare epidemiologists. Molecular Typing Working Group of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1997;18:426–39. doi: 10.1086/647644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tohda S, Maruyama M, Nara N. Molecular typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureusby polymerase chain reaction: distribution of the typed strains in hospitals. Intern Med. 1997;36:694–699. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.36.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Belkum A. The role of short sequence repeats in epidemiologic typing. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:306–311. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)80053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Belkum A, Melchers W J, Ijsseldijk C, Nohlmans L, Verbrugh H, Meis J F. Outbreak of amoxicillin-resistant Haemophilus influenzaetype b: variable number of tandem repeats as novel molecular markers. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1517–1520. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1517-1520.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Belkum A, Scherer S, van Alphen L, Verbrugh H. Short-sequence DNA repeats in prokaryotic genomes. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:275–293. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.275-293.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]