Abstract

Background:

Pregnant women with a substance-related diagnosis, such as an alcohol use disorder, are a vulnerable population that may experience higher rates of severe maternal morbidity, such as hemorrhage and eclampsia, than pregnant women with no substance-related diagnosis.

Methods:

This retrospective cross-sectional study reviewed electronic health record data on women (aged 18–44 years) who delivered a single live birth or stillbirth at ≥ 20 weeks of gestation from March 1, 2016, to August 30, 2019. Women with and without a substance-related diagnosis were matched on key demographic characteristics, such as age, at a 1:1 ratio. Adjusting for these covariates, odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

Results:

A total of 10,125 deliveries met the eligibility criteria for this study. In the matched cohort of 1,346 deliveries, 673 (50.0%) had a substance-related diagnosis, and 94 (7.0%) had severe maternal morbidity. The most common indicators in women with a substance-related diagnosis included hysterectomy (17.7%), eclampsia (15.8%), air and thrombotic embolism (11.1%), and conversion of cardiac rhythm (11.1%). Having a substance-related diagnosis was associated with severe maternal morbidity (adjusted odds ratio = 1.81 [95% CI, 1.14–2.88], p-value = 0.0126). In the independent matched cohorts by substance type, an alcohol-related diagnosis was significantly associated with severe maternal morbidity (adjusted odds ratio = 3.07 [95% CI, 1.58–5.95], p-value = 0.0009), while the patterns for stimulant- and nicotine-related diagnoses were not as well resolved with severe maternal morbidity and opioid- and cannabis-related diagnoses were not associated with severe maternal morbidity.

Conclusion:

We found that an alcohol-related diagnosis, although lowest in prevalence of the substance-related diagnoses, had the highest odds of severe maternal morbidity of any substance-related diagnosis assessed in this study. These findings reinforce the need to identify alcohol-related diagnoses in pregnant women early to minimize potential harm through intervention and treatment.

Keywords: alcohol use, hemorrhage, pregnancy, severe maternal morbidity, substance-related diagnosis

INTRODUCTION

Pregnant women with a substance-related diagnosis (SRD; i.e., use, misuse, abuse, or dependence on substances) are a vulnerable population who may be experiencing disproportionate rates of severe maternal morbidity (SMM) compared with pregnant women without an SRD. An SRD is an increasingly used term designed to evaluate substance exposure and problematic substance use in electronic health record (EHR) population samples (Penzenstadler et al., 2020). SMM is a term that refers to 21 life-threatening labor and delivery outcomes that result in significant consequences to a woman's health (e.g., blood transfusion/hemorrhage, hysterectomy, eclampsia; Center for Disease Control & Prevention [CDC], 2017). The center reported a 200% increase of SMM in the United States from 1993 to 2014 (49.5 to 144.0 per 10,000 delivery hospitalizations; CDC, 2017). In 2014, SMM affected more than 50,000 women nationally (CDC, 2017). This large increase was mostly driven by blood transfusions, which increased 399% (24.5 to 122.3 per 10,000 delivery hospitalizations). The most common SMM after blood transfusions were hysterectomies, ventilation, or temporary tracheostomy resulting in nearly a 20% overall increase in SMM (28.6 to 35.0 per 10,000 delivery hospitalizations; CDC, 2017). Increasing rates of SMM lead to higher medical costs and longer hospital stays (Callaghan et al., 2012).

Increasing maternal age (CDC, 2018), chronic medical conditions (e.g., hypertension; Campbell et al., 2013; Small et al., 2012]), obesity (Fisher et al., 2013; Hinkle et al., 2012), and cesarean delivery (Barber et al., 2011; CDC, 2018) are well-documented predictors of SMM. Studies that have examined the relationship between maternal substance use during pregnancy and SMM found mixed results (e.g., significant associations between opioid and stimulant use with SMM [Jarlenski et al., 2020] and tobacco use with maternal bleeding [Pereira et al., 2018]). National rates of past month alcohol and cannabis use during pregnancy increased from 2016 to 2019 (8.3% and 4.9% to 9.5% and 5.4%, respectively; Center for Behavioral Health Statistics & Quality, 2018). Past month tobacco use during pregnancy decreased from 10.6% to 8.3%, and opioid use decreased from 1.2% to 0.4%. Cocaine use increased slightly from 0.1% to 0.2%. As cannabis legalization continues across the United States, cannabis use is expected to increase. As national reports of maternal substance use continue to fluctuate, updated prevalence and correlates of SMM in pregnant women with an SRD are warranted.

To contribute to the newly growing literature on maternal substance use and SMM, we conducted a retrospective cohort study to evaluate whether there are independent associations between an SRD and SMM among women who presented for delivery in a healthcare system that provides tertiary care and is a referral system for other providers in the community in Southern California. This healthcare system averages 3,000 deliveries per year. It was hypothesized that women who presented for delivery with an SRD during pregnancy would have higher prevalence of SMM and blood transfusions (the most common SMM) compared to women who presented for delivery without an SRD during pregnancy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and participants

This retrospective cohort study used de-identified electronic health record (EHR) data on women (aged 18–44) who delivered a single live birth or stillbirth at ≥ 20 weeks of gestation from March 1, 2016 (42 weeks after the billing codes for blood transfusions became available) through August 30, 2019 (the date the data were requested; 3 years and 6 months). Due to the potential differences in SMM related to the number of fetuses, deliveries of multiple gestation were excluded.

Only women with an International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition (ICD-10) code for delivery for a single live or stillbirth after ≥ 20 weeks of gestation were selected (Table A in the supplemental material; Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, National Center for Health Statistics, 2019). Data were collected from the antepartum (up to 42 weeks before the delivery date) through the postpartum (4 weeks from delivery) periods (total 46 weeks). Because we used the CDC's definition of SMM, we also modeled their data collection time frame and requested data for the 4 weeks after delivery to capture maternal morbidity-related ICD-10 codes (Center for Disease Control & Prevention, 2017). Each patient identification number and the delivery date represented 1 subject. If an individual had more than one delivery carried to a gestational age of ≥ 20 weeks over the 3.5 years of data or an ICD-10 code for a previous pregnancy, the number of previous pregnancies for each delivery was identified and reported. As such, for an individual woman who has had multiple pregnancies in the EHR during the study period, each pregnancy would be counted as an individual delivery event.

The ICD-10 Clinical Modification (CM) and Procedure Coding System (PCS) codes used to identify an SRD, other mental illness (e.g., depression), or other preexisting health condition (e.g., cardiovascular disease) are defined in detail in the Measures section below, and a full list of the ICD-10 codes used in this study can be found in the supplemental material (Tables A-B). The codes used to identify SRDs and other mental illness diagnoses corresponded to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5), which provides a more detailed description of each diagnosis (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; World Health Organization, 2004). Codes were collected from all outpatient visits (e.g., prenatal visit), inpatient visits (e.g., hospitalization), and emergency department visits (e.g., acute care).

This study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). Deidentified health record data were provided by the health center's biomedical informatics team in a secured Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-approved Virtual Research Desktop (VRD). All of the data were electronic, were not accessible through the Internet, were protected by multifactor authentication, and were monitored by the VRD biomedical informatics team.

Measures

The primary outcome SMM (yes/no) was defined by any of the CDC’s 21 SMM indicators identified by ICD-10 CM and PCS codes during the perinatal period (Table B). The secondary outcome was blood transfusion (yes/no) during the perinatal period.

The primary predictor variable was any SRD (yes/no; Table A) during the antepartum and intrapartum period. To prevent potential cofounding associated with substance use after delivery, SRDs that were identified during the postpartum period were excluded from the analysis. The secondary predictor variables included an SRD for alcohol (yes/no), opioids (yes/no), cannabis (yes/no), stimulants (i.e., cocaine, other stimulants [e.g., methamphetamines]; yes/no), and nicotine (yes/no; Table A).

Covariates included age (18–44) and race/ethnicity (Hispanic/Latina, non-Hispanic/Latina Black, non-Hispanic/Latina White, and other race/ethnicity [American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian/Pacific Islander, and other race or mixed]) at delivery. At initial registration in the EHR (e.g., primary outpatient visit, prenatal visit), patients were asked to report their race (e.g., Black, White) and ethnicity (e.g., Hispanic/Latina, African American, Caucasian) as separate categories. Those who did not select Hispanic/Latina, non-Hispanic/Latina Black, or non-Hispanic/Latina White were grouped into the “other” category to address small cell sizes in the other categories. Other covariate variables included marital status (single, divorced/separated/widowed, or married), and body mass index (BMI; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) at delivery. One or more previous pregnancies at ≥ 20 weeks and ending in a live birth or stillbirth (yes/no) was identified to assess and control for the impact of previous pregnancies on SMM. Health insurance types at delivery were private (e.g., commercial, managed care), public (e.g., Medicaid), and no insurance. Those who were grouped in the private insurance category could also have public insurance. Those grouped in the public insurance category did not have private insurance.

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) defines serious mental illness (SMI) as a mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder that results in serious functional impairment (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder; National Institute of Mental Health, 2019). SMIs significantly impedes one or more major life activities. In order to identify severe and nonsevere mental illness, a variable for SMI (yes/no) and non-SMI (any other mental illness [e.g., anxiety], which is not included in the SMI category; yes/no) was created using ICD-10 codes. A summary variable for preexisting health condition included anemia, cardiovascular disease, diabetes (nongestational), cancer, kidney failure, hypertension, lupus erythematosus, epilepsy, pulmonary disease, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and tuberculosis (TB; Hirshberg & Srinivas, 2017). ICD-10 codes are available upon request.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to identify the number and type of the CDC’s 21 SMM indicators during the perinatal period. Summary variables for SMM (yes/no), blood transfusion (yes/no), SRD (yes/no), and the other covariates were then created.

Propensity score matching yielding a matched 1:1 sample using predictors of SMM (i.e., age at delivery, BMI at delivery, one or more previous pregnancies at ≥ 20 weeks and ending in a live birth or stillbirth [yes/no], preexisting health condition [yes/no], and delivery year; Blanc et al., 2019; Creanga et al., 2014; Gouin et al., 2011) was used to measure imbalance in maternal sociodemographic and obstetrical characteristics between those with and without an SRD (Ho et al., 2007; Iacus et al., 2012). The balance of covariate distribution between the two groups was examined using standardized mean differences.

Unadjusted and adjusted analyses of the covariate variables and SMM were conducted in the unmatched and matched cohorts using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous data and the chi-square (χ2) tests of significance for categorical data. To determine the effect/magnitude of the associations, odds ratios (ORs) were calculated and reported. Two-sided tests with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) that cross 1, indicating that there was no significant difference, and p-values ≥ 0.05 were used to determine whether a covariate would be included in the final adjusted regression model in both the unmatched and the matched cohorts.

Multivariable logistic regression models were conducted to determine the covariate variables that were associated with having SMM compared with those without SMM. Standardized betas (β), standard errors (SE [β]), adjusted odds ratios (aOR), and the respective CIs and p-values were reported. All analyses were conducted with SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute).

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

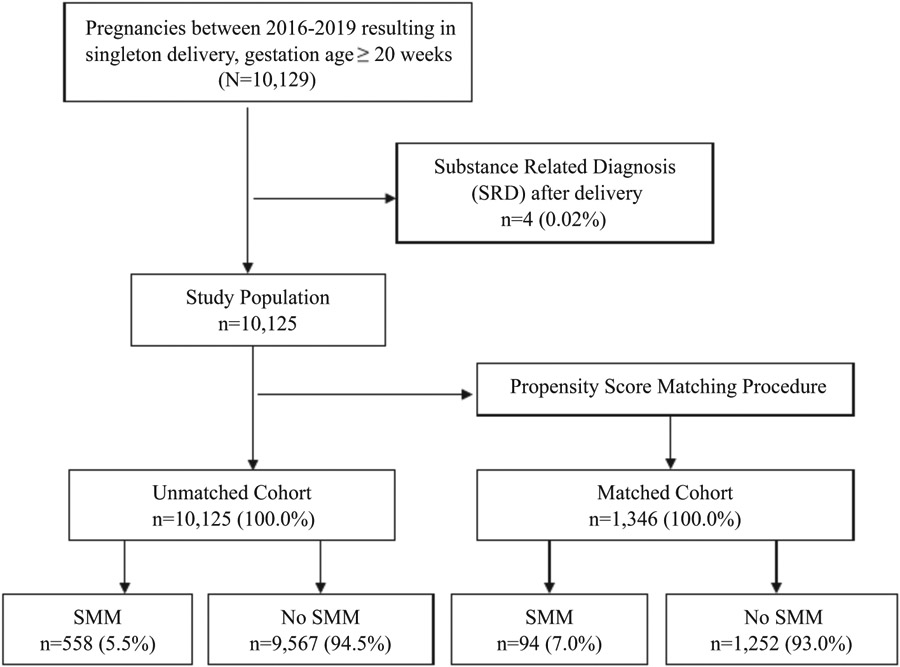

There were a total of 10,129 deliveries with an ICD-10 code for a single delivery at ≥20 weeks’ gestation from March 1, 2016, to August 30, 2019 (Figure 1). Four individuals with an SRD after delivery were eliminated from the dataset resulting in an unmatched cohort of 10,125. Of the 10,125 deliveries in the unmatched cohort, an SRD was identified in 673 (6.6%) women with a documented delivery (Table 1). SMM was identified in 558 (5.5%) women with a documented delivery. The most common SMM included blood transfusions (40.7%), sepsis (19.9%), acute renal failure (15.1%), and disseminated intravascular coagulation (14.2%). The most common SMM indicators in those with an SRD included hysterectomy (17.7%), eclampsia (15.8%), air and thrombotic embolism (11.1%), conversion of cardiac rhythm (11.1%), cardiac arrest/ventricular fibrillation (10.0%), and pulmonary edema/acute heart failure (10.0%).

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of the study population for severe maternal morbidity (SMM) in pregnant women in a large healthcare system from March 1, 2016, to August 30, 2019

TABLE 1.

Severe maternal morbidity indicators identified in unmatched cohort of women with a documented delivery from a large healthcare system's electronic health record from March 1, 2016, to August 30, 2019 (n = 10,125)

| All women with SMM by SMM type n (%) |

Only women with SMM by SMM type n (%) |

All women with an SRD and SMM by SMM type n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Severe maternal morbidity (SMM) | 558 (5.5) | 558 (100.0) | 64 (11.5) |

| Blood transfusion | 226 (2.2) | 226 (40.7) | 14 (6.2) |

| Sepsis | 111 (1.1) | 111 (19.9) | 4 (3.6) |

| Acute renal failure | 84 (0.8) | 84 (15.1) | 5 (5.9) |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | 79 (0.8) | 79 (14.2) | 3 (3.8) |

| Pulmonary edema/acute heart failure | 40 (0.4) | 40 (7.2) | 4 (10.0) |

| Puerperal cerebrovascular disorders | 38 (0.4) | 38 (6.8) | 2 (5.3) |

| Air and thrombotic embolism | 36 (0.4) | 36 (6.5) | 4 (11.1) |

| Shock | 29 (0.3) | 29 (5.2) | 2 (6.9) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 24 (0.2) | 24 (4.3) | 2 (8.3) |

| Eclampsia | 19 (0.2) | 19 (3.4) | 3 (15.8) |

| Hysterectomy | 17 (0.2) | 17 (3.1) | 3 (17.7) |

| Adult respiratory distress syndrome | 13 (0.1) | 13 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Ventilation | 13 (0.1) | 13 (2.3) | 1 (7.7) |

| Cardiac arrest/ventricular fibrillation | 10 (0.1) | 10 (1.8) | 1 (10.0) |

| Conversion of cardiac rhythm | 9 (0.1) | 9 (1.6) | 1 (11.1) |

| Aneurysm | 4 (0.0) | 4 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Amniotic fluid embolism | 2 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Sickle cell disease with crisis | 1 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Heart failure/arrest during surgery or procedure | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Severe anesthesia complications | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Temporary tracheostomy | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

Abbreviation: SRD, substance-related diagnosis (i.e., alcohol, stimulants, nicotine, opioids, and nicotine).

Due to the large sample size, almost all of the comparisons in the unadjusted analyses revealed differences that were found to be significantly associated with SMM (yes/no; Table C in the supplemental material). In the matched cohort of 1,346 deliveries, most were non-Hispanic/Latina White (42.6%) or other race/ethnicity (36.5%) with a mean age of 29.9 (standard deviation [SD] = 5.6, range 18–44 years of age; Table 2). The majority of the sample were married (48.8%) or single (46.6%), had a mean BMI of 32.3 (SD = 7.2, range = 17.2–83.5), had no previous pregnancies (90.2%), and had private health insurance (71.9%). SMI and non-SMIs were documented for 8.5% and 36.4%, respectively (Table 2). Preexisting health conditions were documented for 51.9% due to matching.

TABLE 2.

Matched unadjusted analysis of factors associated with severe maternal morbidity among women with a documented delivery from a large healthcare system's electronic health record from March 1, 2016, to August 30, 2019 (n = 1,346)

| Parameter | Total n (%)/mean (SD) |

Severe maternal morbidity n (%)/Mean (SD) |

No severe maternal morbidity n (%)/Mean (SD) |

Odds ratio 95% (CI) |

χ 2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 1,346 (100.0) | 94 (7.0) | 1,252 (93.0) | |||

| Age at delivery (range 18–44) | 29.9 ± 5.6 | 29.9 ± 5.0 | 29.9 ± 5.7 | 1.00 (0.96–1.04) | 0.00 | 0.9675 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic/Latina | 148 (11.2) | 7 (7.5) | 141 (11.5) | 0.73 (0.31–1.67) | 1.76 | 0.1841 |

| Non-Hispanic/Latina Black | 128 (9.7) | 12 (12.8) | 116 (9.45) | 1.51 (0.76–3.00) | 1.66 | 0.1977 |

| Other* | 482 (36.5) | 39 (41.5) | 443 (36.1) | 1.29 (0.81–2.06) | 0.85 | 0.3575 |

| Non-Hispanic/Latina White | 563 (42.6) | 36 (38.3) | 527 (93.6) | -- | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 625 (46.6) | 50 (53.2) | 575 (46.1) | 1.49 (0.96–2.32) | 0.07 | 0.7952 |

| Divorced, separated, widowed | 62 (4.6) | 8 (8.5) | 54 (4.3) | 2.54 (1.13–5.75) | 3.44 | 0.0636 |

| Married | 654 (48.8) | 36 (38.3) | 618 (49.6) | -- | ||

| BMI at delivery (range 17.2–83.5) | 32.3 ± 7.2 | 33.2 ± 8.6 | 32.2 ± 7.1 | 1.01 (1.00–1.04) | 0.79 | 0.3750 |

| ≥1 previous pregnancy at ≥20 weeks | ||||||

| No | 1214 (90.2) | 85 (90.4) | 1129 (90.2) | 1.03 (0.50–2.01) | 0.01 | 0.9380 |

| Yes | 132 (9.8) | 9 (5.6) | 123 (9.8) | -- | ||

| Health insurance | ||||||

| Public | 330 (24.5) | 18 (19.2) | 312 (24.9) | 1.22 (0.37–4.03) | 0.63 | 0.4262 |

| No insurance | 48 (3.6) | 3 (3.2) | 45 (3.6) | 0.87 (0.25–3.06) | 0.37 | 0.5287 |

| Private | 968 (71.9) | 73 (77.7) | 895 (71.5) | -- | ||

| Substance-related diagnosis | ||||||

| Yes | 673 (50.0) | 61 (64.9) | 612 (48.9) | 1.93 (1.26–3.00) | 8.71 | 0.0032 |

| No | 673 (50.0) | 33 (35.1) | 640 (51.1) | -- | ||

| Serious mental illness | ||||||

| Yes | 114 (8.5) | 11 (11.7) | 103 (8.2) | 1.48 (0.76–2.86) | 1.35 | 0.2459 |

| No | 1232 (91.5) | 83 (88.3) | 1149 (91.8) | -- | ||

| Non-serious mental illness | ||||||

| Yes | 490 (36.4) | 45 (47.9) | 445 (35.5) | 1.67 (1.09–2.54) | 5.64 | 0.0175 |

| No | 856 (63.6) | 49 (52.1) | 807 (64.5) | |||

| Preexisting health condition | ||||||

| Yes | 698 (51.9) | 72 (76.6) | 626 (50.0) | 3.27 (2.00–5.34) | 22.47 | <0.0001 |

| No | 648 (48.1) | 22 (23.4) | 626 (50.0) | |||

Note: Women (n = 10,125) with and without a substance-related diagnosis were matched on age at delivery, body mass index (BMI) at delivery, one or more previous pregnancies at ≥ 20 weeks and ending in a live birth or stillbirth (yes/no), preexisting health condition (yes/no), and delivery year. Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Other race/ethnicity includes American Indian/Alaskan Native (n = 8), Asian/Pacific Islander (n = 88), and other race or mixed race/ethnicity (n = 386). Age at delivery by SMM: n = 94, median = 30, range = 19–42. Age at delivery by non-SMM: n = 1,252, median = 30, range = 19–42. BMI at delivery by SMM: n = 94, median = 31, range = 20.4–71.5. BMI at delivery by non-SMM: n = 1,252, median = 30.8, range = 18.8–66.5. p-values based on the chi-square (X2) tests of significance for categorical data or F for continuous data.

Prevalence and correlates of SMM in the matched cohort

In the matched unadjusted analysis (n = 1,346), SMM was associated with SRD (OR = 1.93 [95% CI, 1.26–3.00], p-value = 0.0032), non-SMI (OR = 1.67 [95% CI, 1.09–2.54], p-value = 0.0175), and preexisting health conditions (OR = 3.27 [95% CI, 2.00–5.34], p-value = < 0.0001; Table 2). An SRD was not significantly associated with blood transfusion (OR = 1.29 [95% CI, 0.64–2.62], p-value = 0.4753; Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Matched unadjusted analysis of factors associated with a blood transfusion among women with a documented delivery from a large healthcare system's electronic health record from March 1, 2016, to August 30, 2019 (n = 1,346)

| Parameter | Total n (%) |

Blood transfusion Yes, n (%) |

Blood transfusion No, n (%) |

Odds ratio 95% (CI) |

χ 2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 1,346 (100.0) | 32 (2.4) | 1,314 (97.6) | |||

| Substance-related diagnosis | ||||||

| Yes | 673 (50.0) | 18 (56.3) | 655 (49.9) | 1.29 (0.64–2.62) | 0.51 | 0.4753 |

| No | 673 (50.0) | 14 (43.8) | 659 (50.2) | -- | ||

Note: Women with and without a substance-related diagnosis were matched on age at delivery, body mass index (BMI) at delivery, one or more previous pregnancies at ≥ 20 weeks and ending in a live birth or stillbirth (yes/no), preexisting health condition (yes/no), and delivery year. p-values based on the chi-square (χ2) tests of significance for categorical data or F for continuous data.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

In the matched adjusted regression (n = 1,346), having an SRD (aOR = 1.81 [95% CI, 1.14–2.88], p-value = 0.0126) and preexisting health condition (aOR = 3.21 [95% CI, 1.96–5.26], p-value = < 0.0001) was significantly associated with SMM (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Matched adjusted logistic regression analysis of factors associated with severe maternal morbidity among women with a documented delivery from a large healthcare system's electronic health record from March 1, 2016, to August 30, 2019 (n = 1,346)

| Parameter | B | SE (β) | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

χ 2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substance-related diagnosis | |||||

| Yes | 0.30 | 0.12 | 1.81 (1.14–2.88) | 6.22 | 0.0126 |

| No | |||||

| Non-serious mental illness | |||||

| Yes | 0.12 | 0.11 | 1.28 (0.82–2.01) | 1.19 | 0.2747 |

| No | |||||

| Preexisting health condition | |||||

| Yes | 0.58 | 0.13 | 3.21 (1.96–5.26) | 21.71 | <0.0001 |

| No |

Note: Women with and without a substance-related diagnosis were matched on age at delivery, body mass index (BMI) at delivery, one or more previous pregnancies at ≥20 weeks and ending in a live birth or stillbirth (yes/no), preexisting health condition (yes/no), and delivery year.

β = standardized betas, SE(β) = standard errors, CI = confidence interval, p-values based on the chi-square (χ2) tests of significance for categorical data.

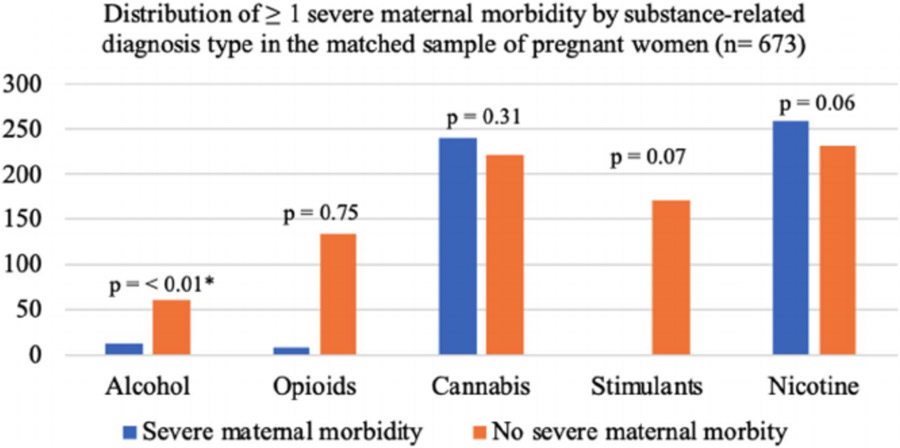

When grouped by SRD type in the matched adjusted regression analyses, alcohol-related diagnosis was associated with SMM (aOR = 3.07 [95% CI, 1.58–5.95], p-value = 0.0009; Table 5 and Figure 2). The patterns for stimulant- and nicotine-related diagnoses were not as well resolved, with p-values of 0.0687 and 0.0581 for stimulant- and nicotine-related diagnoses, respectively. The interval estimates for the association between these diagnoses ranged from no association to over 2.5 times the odds of SMM (stimulants aOR = 1.62 [95% CI, 1.00–2.72], and nicotine aOR = 1.60 [95% CI, 1.00–2.60]). An opioid- or cannabis-related diagnosis was not significantly associated with SMM (aOR = 0.68 [95% CI, 0.33–1.42], p-value = 0.3074 and aOR = 1.09 [95% CI, 0.64–1.87], p-value = 0.7495).

TABLE 5.

Matched adjusted logistic regression analysis of substance-related diagnosis types and severe maternal morbidity among women with a documented delivery from a large healthcare system's electronic health record from March 1, 2016, to August 30, 2019 (n = 1,346)

| Parameter | Total n (%) |

Severe maternal morbidity n (%) |

No severe maternal morbidity n (%) |

Adjusted odds ratio 95% (CI) |

χ 2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol-related diagnosis | ||||||

| Yes | 75 (5.6) | 13 (13.8) | 62 (5.0) | 3.07 (1.58–5.95) | 10.93 | 0.0009 |

| No | 1,271 (94.4) | 81 (86.2) | 1,190 (95.0) | -- | ||

| Opioid-related diagnosis | ||||||

| Yes | 142 (10.6) | 9 (9.6) | 133 (10.6) | 0.68 (0.33–1.42) | 1.04 | 0.3074 |

| No | 1,204 (89.5) | 85 (90.4) | 1,119 (89.4) | -- | ||

| Cannabis-related diagnosis | ||||||

| Yes | 241 (17.9) | 19 (20.2) | 222 (17.7) | 1.09 (0.64–1.87) | 0.10 | 0.7495 |

| No | 1,105 (82.1) | 75 (79.8) | 1,030 (82.3) | -- | ||

| Stimulant-related diagnosis | ||||||

| Yes | 193 (14.3) | 22 (23.4) | 171 (13.7) | 1.62 (1.00–2.72) | 3.31 | 0.0687 |

| No | 1,153 (85.7) | 72 (76.6) | 1,081 (86.3) | -- | ||

| Nicotine-related diagnosis | ||||||

| Yes | 258 (19.2) | 27 (28.7) | 231 (18.5) | 1.60 (1.00–2.60) | 3.59 | 0.0581 |

| No | 1,088 (80.8) | 67 (71.3) | 1,021 (81.6) | -- | ||

Note: Women with and without a substance-related diagnosis were matched on age at delivery, body mass index (BMI) at delivery, one or more previous pregnancies at ≥20 weeks and ending in a live birth or stillbirth (yes/no), preexisting health condition (yes/no), and delivery year. Each adjusted model by substance type controls for the other covariates that were found to be significantly associated with SMM in the unadjusted analyses (i.e., preexisting health condition and nonserious mental illness). The results for preexisting health condition and nonserious mental illness by substance type are available upon request. p-values based on the chi-square (χ2) tests of significance for categorical data. Variable totals may not sum to column totals due to missing data.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation.

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of ≥1 severe maternal morbidity (SMM) by substance-related diagnosis type in a matched 1:1 sample of pregnant women in a large healthcare system from March 1, 2016, to August 30, 2019 (n = 673). *Having an alcohol-related diagnosis was associated with SMM (adjusted odds ratio = 3.07 [95% CI, 1.58–5.95], p-value = 0.0009). Women without a substance-related diagnosis (n = 1,252) are not included in this graph due to the unbalanced distribution of women without a substance-related diagnosis and SMM, which makes the figure difficult to interpret. However, the sample size and percentage for each substance by those with and without SMM can be found in Table 5. Note: The graph appears to visually present a significant difference between an opioid-related diagnosis and SMM. However, due to the large difference in sample size in women with and without SMM and the small sample size of women with an opioid-related diagnosis with SMM (n = 9), no significant association was observed

DISCUSSION

Principal findings

Within a large matched pregnancy cohort in a healthcare system that provides tertiary care and is a referral system for other providers in the community from 2016 to 2019, having an SRD and preexisting health condition was significantly associated with SMM during the perinatal period. The most common SMM included blood transfusions, sepsis, acute renal failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. The most common SMM indicators in those with an SRD included hysterectomy, eclampsia, air and thrombotic embolism, conversion of cardiac rhythm, cardiac arrest/ventricular fibrillation, and pulmonary edema/acute heart failure. In the matched cohorts by substance type, an alcohol-related diagnosis was significantly associated with SMM. The patterns for stimulant- and nicotine-related diagnoses were not as well resolved with SMM. Opioid- and cannabis-related diagnoses were not associated with SMM.

The findings from this study are consistent with a study investigating SMM hospitalizations in the United States, England, and Australia from 2008 to 2013, which found that advanced maternal age, substance use, hypertension, and diabetes were strongly associated with SMM in all three countries (Lipkind et al., 2019). Rates of women with chronic health conditions such as hypertension, cardiac disease, and diabetes in the United States are increasing (Hirshberg & Srinivas, 2017). These types of conditions can be exacerbated during pregnancy. As such, pregnant women with an SRD and preexisting health conditions should be identified early and monitored closely by healthcare providers.

Alcohol is one of the most commonly used substances in pregnant women, and it is often used in conjunction with other substances such as tobacco and cannabis (Huizink, 2009). Our data showed that an alcohol-related diagnosis had the lowest prevalence and the highest odds of SMM during the perinatal period compared with any other substance assessed in this study (i.e., opioids, cannabis, stimulants, and nicotine). This is likely due to underreporting of alcohol use in this clinical setting. Nevertheless, these results show that alcohol use, misuse, abuse, or dependence during pregnancy is a strong predictor of SMM. Currently, there is limited research on the impact of prenatal alcohol use and SMM. Prenatal alcohol use has been found to decrease uteroplacental perfusion, which results in intrauterine growth restriction (Ramadoss & Magness, 2012). Chronic alcohol use puts women at risk for hepatic dysfunction (Edelson & Bernstein, 2019). Studies have also found associations between prenatal alcohol consumption and vaginal bleeding in the first trimester (Hasan et al., 2010), smaller placenta-to-birthweight ratio, placental weight, and increased risk of hemorrhage, and plate vessel congestion (Carter et al., 2016). A study in Ethiopia identified prenatal alcohol use as significant risk factor for preeclampsia/eclampsia (Grum et al., 2017). Alcohol is a known teratogen, which operates under a dose–response mechanism. Additional research on the dose–response relationship between prenatal alcohol consumption and SMM is needed to minimize potential harm through intervention and treatment.

The pattern for stimulant-related diagnosis was not as well resolved in this study (Cummins j Marks, 2020; Kraemer, 2019). This is not consistent with the relationship between stimulant use and SMM observed in previous research, which identified an increased risk of SMM and maternal mortality after delivery (Hser et al., 2012; Jarlenski et al., 2020; Wolfe et al., 2005). A recent retrospective analysis of 53.4 million delivery hospitalizations from 2006 to 2016 identified a significant relationship between stimulant and opioid use disorders and SMM, but not cannabis (Jarlenski et al., 2020). The relationship between alcohol use and SMM was not assessed in the aforementioned study. In another study, a higher incidence of SMM, preterm delivery, preeclampsia, and mortality was observed in stimulant-related deliveries compared with the opioid-related deliveries from 2005 to 2015 (Admon et al., 2019).

Unlike the study previously mentioned, the current study did not find a significant association between an opioid-related diagnosis and SMM. The differences observed in our study may be related to how substance use disorders (a subgroup of an SRD) and SRDs are documented in the EHR. For example, the ICD-10 codes used to identify an opioid-related diagnosis may better represent opioid use during pregnancy than the opioid use disorder category, which requires a formal DSM-5 diagnosis. Our study also did not account for medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD; e.g., buprenorphine and methadone), as seen in the same study mentioned previously (Jarlenski et al., 2020).

Early and ongoing studies have shown adverse fetal and delivery outcomes associated with tobacco use in the perinatal period (McEvoy & Spindel, 2017). Smoking tobacco may be associated with placental abruption, which increases the risk of obstetric hemorrhage, blood transfusions, hysterectomy, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, and renal failure (Bodelon et al., 2009; Tikkanen, 2011; Tikkanen et al., 2009). As the popularity of electronic cigarettes continues to increase nationally, additional research on the direct effects of maternal nicotine use and SMM is needed (Mark et al., 2015).

As observed in the recent analysis of 53.4 million deliveries mentioned previously, the current study did not find a significant association between a cannabis-related diagnosis and SMM (Jarlenski et al., 2020). Previous research has found an association between cannabis use and low birthweight (El Marroun et al., 2009; National Academy of Medicine Committee on the Health Effects of Marijuana, 2017). Although there are conflicting data surrounding pregnancy outcomes and cannabis use (Jarlenski et al., 2020; Metz et al., 2017), major regulatory bodies, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), recommend against cannabis use during pregnancy. In contrast to substances such as alcohol and stimulants that function on the central nervous system, cannabis functions through the endocannabinoid system (Behnke & Smith, 2013; Metz & Stickrath, 2015). Cannabis use is not significantly associated with the activities that could precipitate higher risks such as sepsis, endocarditis, and cardiovascular and pulmonary failure such as injection drug use and overdose (Jarlenski et al., 2020; Smid et al., 2019).

The results from this study show a high prevalence and odds of SMM in pregnant women with an SRD and alcohol-related diagnosis, which reinforces a rationale for robust and continuous screening measures in all clinical settings. Questions regarding alcohol and other substance use should be posed often and in different capacitates (e.g., prenatal and other outpatient visits), to identify pregnant women with an SRD early. Screening through questions related to alcohol and other substance use should be posed sensitively with attention to reducing the stigma that women may feel in disclosing use (Courchesne & Meyers, 2020; Meyers et al., 2021) and should include questions specifically related to different types of substances such as alcohol, stimulants, and nicotine.

The results of this study also support the need to design, implement, and test robust screening and monitoring interventions in all types of clinical encounters including prenatal, primary care, and psychiatry visits to manage and treat substance use during pregnancy. Future studies should investigate how prenatal alcohol use dose–responses, biological and environmental impact of substance use, polysubstance use, and treatment (e.g., MOUD) impact SMM risk and differentiate between differences in substance exposure (e.g., alcohol) and lifestyle factors (e.g., homelessness).

Strengths and limitations

This study is strengthened by a large sample size of women who presented for delivery over 3.5 years, and the utilization of robust methodology (e.g., propensity score matching to control for confounding in the unstructured EHR data). These methods eliminated a greater portion of potential bias when the effects of SRD were estimated. This study is limited by using ICD-10 codes for health-related diagnoses, which could have involved misclassification bias, unmeasured confounding (e.g., current treatment for SRD, MOUD), eligibility changes over time (e.g., discontinued substance use after a SRD), and missing data (e.g., polysubstance substance use that is not accounted for; Benchimol et al., 2015; Utter, Atolagbe & Cooke, 2019). In an effort to mitigate these concerns, we used robust matching techniques, only selected women with an SRD from conception to ≤ 42 weeks, and eliminated anyone with an SRD after delivery. Compared with other studies, an inconsistent distribution of ≥ 1 previous pregnancy was observed in this study due to matching on this variable (Corsi et al., 2019). To confirm that this variable did not impact the results of this study, the analysis was repeated without matching on this variable, and again for primigravida women. The relationship between an SRD, the other covariates (e.g., age), and the outcome variables remained significant in both analyses, confirming that our decision to match on ≥ 1 previous pregnancy did not impact the final results. Because we do not have universal screening for substance use in our health system, we recognize that the SRDs, such as alcohol use and misuse, are likely an underreporting of the prevalence in the community. However, those who receive an ICD-10 diagnostic code for an SRD in the EHR are likely identified due to self-report or problematic symptoms that are presenting due to their substance use. Therefore, these diagnostic codes are likely a marker that the patient's presentation is significant enough to code for an SRD in the EHR and may in fact be impacting other outcomes such as SMM. An SRD was not significantly associated with blood transfusions, the most common SMM. This observation may be related to data misclassification. For example, ICD-10 codes are used to classify obstetrical hemorrhage and blood transfusions as clinical diagnoses vs. procedures, respectively. The procedure codes used in the CDC’s 21 SMM indicators were not made available in this particular EHR until 3 years after its inception. As such, there may be some discrepancies in the classification of blood transfusions and the subsequent SMM grouping variable. Despite this potential limitation, an association between SRD and SMM was still observed. The generalizability of the relationship between SRD and SMM in this study is limited by the restriction to Southern California, one healthcare system, and the low proportion of non-White (e.g., Black) subjects in this region.

CONCLUSION

This study contributes important information to an understudied field toward supporting maternal health. Substance- and alcohol-related diagnoses were significantly associated with SMM. An alcohol-related diagnosis had the lowest prevalence and the highest odds of SMM compared with any other substance assessed in this study. The patterns for stimulant- and nicotine-related diagnoses were not as well resolved with SMM. Opioid- and cannabis-related diagnoses were not associated with SMM. This shows that alcohol use, misuse, abuse, or dependence during pregnancy may be a strong predictor of SMM. The results from this study reinforce the need to identify SRDs in pregnant women early to minimize potential harm through intervention and treatment. Interventions designed to screen and monitor pregnant women with an SRD should be developed and implemented in all types of clinical encounters including prenatal, primary care, and psychiatry visits. Additional research on the relationships between the prenatal alcohol use dose–response, the biological and environmental impact on maternal substance use, polysubstance use, and MOUD have on SMM is also needed.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions to this research by the Altman Clinical and Translational Research Institute's Virtual Research Desktop (VRD) analytics team and collaborators at the University of California San Diego (supported by the National Institute of Health, Grant UL1TR001442 of CTSA Funding).

Funding information

This research was funded by Dr. Carla Marienfeld's research funds through the Department of Psychiatry at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine. Dr. Laramie R. Smith's contributions to this work were facilitated by the National Institute on Drug Abuse Career Development Award (K01 DA039767).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflict of interest.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section.

REFERENCES

- Admon LK, Bart G, Kozhimannil KB, Richardson CR, Dalton VK & Winkelman TNA (2019) Amphetamine- and opioid-affected births: incidence, outcomes, and costs, United States, 2004–2015. American Journal of Public Health, 109, 148–154. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Barber EL, Lundsberg LS, Belanger K, Pettker CM, Funai EF & Illuzzi JL (2011) Indications contributing to the increasing cesarean delivery rate. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 118, 29–38. 10.10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821e5f65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke M & Smith VC (2013) Prenatal substance abuse: short- and long-term effects on the exposed fetus. Pediatrics, 131, e1009–e1024. 10.10.1542/peds.2012-3931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, Harron K, Moher D, Petersen I et al. (2015) The reporting of studies conducted using observational routinely-collected health data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med, 12, e1001885. 10.10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc J, Resseguier N, Goffinet F, Lorthe E, Kayem G, Delorme P et al. (2019) Association between gestational age and severe maternal morbidity and mortality of preterm cesarean delivery: a population-based cohort study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 220, 399.e1–399.e9. 10.10.1016/J.AJOG.2019.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodelon C, Bernabe-Ortiz A, Schiff MA & Reed SD (2009) Factors associated with peripartum hysterectomy. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 114, 115–123. 10.10.1097/AOG.0B013E3181A81CDD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan WM, Creanga AA & Kuklina EV (2012) Severe maternal morbidity among delivery and postpartum hospitalizations in the United States. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 120, 1029–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KH, Savitz D, Werner EF, Pettker CM, Goffman D, Chazotte C et al. (2013) Maternal morbidity and risk of death at delivery hospitalization. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 122, 627–633. 10.10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182a06f4e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RC, Wainwright H, Molteno CD, Georgieff MK, Dodge NC, Warton F et al. (2016) Alcohol, methamphetamine, and marijuana exposure have distinct effects on the human placenta. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 40, 753–764. 10.10.1111/acer.13022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (2018) National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed tables. Substance abuse and mental health services administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHDetailedTabs2018R2/NSDUHDetailedTabs2018.pdf [Accessed May 9, 2020] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2017) Severe maternal morbidity in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/severematernalmorbidity.html#anchor_References [Accessed May 9, 2020]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Driscoll AK & Rossen LM (2018) Births: provisional data for 2017. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/55172

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, National Center for Health Statistics (2019) ICD-10-CM: Official guidelines for coding and reporting FY. 2019 (October 1, 2018–September 30, 2019). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/icd/10cmguidelines-FY2020_final.pdf

- Corsi DJ, Walsh L, Weiss D, Hsu H, El-Chaar D, Hawken S et al. (2019) Association between self-reported prenatal cannabis use and maternal, perinatal, and neonatal outcomes. Journal of the American Medical Association, 322, 145. 10.10.1001/jama.2019.8734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courchesne NS & Meyers SA (2020) Women and pregnancy. In: Marienfeld C (Ed.) Absolute addiction psychiatry review. Springer International Publishing, pp. 259–275. 10.10.1007/978-3-030-33404-8_16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Creanga AA, Berg CJ, Ko JY, Farr SL, Tong VT, Bruce FC et al. (2014) Maternal mortality and morbidity in the United States: where are we now? Journal of Women’s Health, 23, 3–9. 10.10.1089/jwh.2013.4617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins KM & Marks C (2020) Farewell to bright-line: a guide to reporting quantitative results without the s-word. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. 10.10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelson PK & Bernstein SN (2019) Management of the cardiovascular complications of substance use disorders during pregnancy. Current Treatment Options in Cardiovascular Medicine, 21, 1–13. 10.10.1007/s11936-019-0777-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Marroun H, Tiemeier H, Steegers EA, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, Verhulst FC et al. (2009) Intrauterine cannabis exposure affects fetal growth trajectories: the Generation R Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 48, 1173–1181. 10.10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181bfa8ee [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher SC, Kim SY, Sharma AJ, Rochat R & Morrow B (2013) Is obesity still increasing among pregnant women? Prepregnancy obesity trends in 20 states, 2003–2009. Preventive Medicine, 56, 372–378. 10.10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.02.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouin K, Murphy K & Shah PS (2011) Effects of cocaine use during pregnancy on low birthweight and preterm birth: systematic review and metaanalyses. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 204, 340.e1–340.e12. 10.10.1016/J.AJOG.2010.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grum T, Seifu A, Abay M, Angesom T& Tsegay L (2017) Determinants of pre-eclampsia/eclampsia among women attending delivery services in selected public hospitals of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a case control study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17, 1–7. 10.10.1186/s12884-017-1507-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan R, Baird DD, Herring AH, Olshan AF, Funk MLJ & Hartmann KE (2010) Patterns and predictors of vaginal bleeding in the first trimester of pregnancy. Annals of Epidemiology, 20, 524–531. 10.10.1016/J.ANNEPIDEM.2010.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkle SN, Sharma AJ, Kim SY, Park S, Dalenius K, Brindley PL et al. (2012) Prepregnancy obesity trends among low-income women, United States, 1999–2008. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16, 1339–1348. 10.10.1007/s10995-011-0898-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshberg A & Srinivas SK (2017) Epidemiology of maternal morbidity and mortality. Seminars in Perinatology, 41, 332–337. 10.10.1053/J.SEMPERI.2017.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho DE, Imai K, King G & Stuart EA (2007) Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Political Analysis, 15, 199–236. 10.10.1093/pan/mpl013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Kagihara J, Huang D, Evans E & Messina N (2012) Mortality among substance-using mothers in California: a 10-year prospective study. Addiction, 107, 215–222. 10.10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03613.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizink AC (2009) Moderate use of alcohol, tobacco and cannabis during pregnancy: new approaches and update on research findings. Reproductive Toxicology, 28, 143–151. 10.10.1016/J.REPROTOX.2009.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacus SM, King G & Porro G (2012) Causal inference without balance checking: coarsened exact matching. Political Analysis, 20, 1–24. 10.10.1093/pan/mpr013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jarlenski M, Krans EE, Chen Q, Rothenberger SD, Cartus A, Zivin K et al. (2020) Substance use disorders and risk of severe maternal morbidity in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 216, 108–236. 10.10.1016/J.DRUGALCDEP.2020.108236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC (2019) Is it time to ban the p value? Journal of the American Medical Association Psychiatry, 76, 1219–1220. 10.10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.1965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipkind H, Zuckerwise L, Turner E, Collins J, Campbell K, Reddy U et al. (2019) Severe maternal morbidity during delivery hospitalisation in a large international administrative database, 2008–2013: a retrospective cohort. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 126(10), 1223–1230. 10.10.1111/1471-0528.15818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark KS, Farquhar B, Chisolm MS, Coleman-Cowger VH & Terplan M (2015) Knowledge, attitudes, and practice of electronic cigarette use among pregnant women. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 9, 266–272. 10.10.1097/ADM.0000000000000128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy CT & Spindel ER (2017) Pulmonary effects of maternal smoking on the fetus and child: effects on lung development, respiratory morbidities, and life long lung health. Paediatric Respiratory Reviews, 21, 27–33. 10.10.1016/J.PRRV.2016.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz TD, Allshouse AA, Hogue CJ, Goldenberg RL, Dudley DJ, Varner MW et al. (2017) Maternal marijuana use, adverse pregnancy outcomes, and neonatal morbidity. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 217, 478.e1–478.e8. 10.10.1016/j.ajog.2017.05.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz TD & Stickrath EH (2015) Marijuana use in pregnancy and lactation: a review of the evidence. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 213, 761–778. 10.10.1016/J.AJOG.2015.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers SA, Earnshaw VA, D’Ambrosio B, Courchesne N, Werb D & Smith LR (2021) The intersection of gender and drug use-related stigma: a mixed methods systematic review and synthesis of the literature. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 223, 108706. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academy of Medicine Committee on the Health Effects of Marijuana (2017) The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: the current state of evidence and recommendations for research. Washington, DC: District of Columbia. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health (2019) Mental Illness. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness [Accessed May 10, 2020]

- Penzenstadler L, Gentil L, Huýnh C, Grenier G & Fleury MJ (2020) Variables associated with low, moderate and high emergency department use among patients with substance-related disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 207, 107817. 10.10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira C, Pacagnella R, Parpinelli M, Andreucci C, Zanardi D, Souza R et al. (2018) Drug use during pregnancy and its consequences: a nested case control study on severe maternal morbidity. Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia/RBGO Gynecology and Obstetrics, 40, 518–526. 10.10.1055/s-0038-1667291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadoss J & Magness RR (2012) Vascular effects of maternal alcohol consumption. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 303, H414–H421. 10.10.1152/ajpheart.00127.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small MJ, James AH, Kershaw T, Thames B, Gunatilake R & Brown H (2012) Near-miss maternal mortality: cardiac dysfunction as the principal cause of obstetric intensive care unit admissions. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 119, 250–255. 10.10.1097/AOG.0b013e31824265c7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smid MC, Metz TD & Gordon AJ (2019) Stimulant use in pregnancy: an under-recognized epidemic among pregnant women. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology, 62, 168–184. 10.10.1097/GRF.0000000000000418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikkanen M (2011) Placental abruption: epidemiology, risk factors and consequences. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 90, 140–149. 10.10.1111/j.1600-0412.2010.01030.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikkanen M, Gissler M, Metsäranta M, Luukkaala T, Hiilesmaa V, Andersson S et al. (2009) Maternal deaths in Finland: Focus on placental abruption. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 88, 1124–1127. 10.10.1080/00016340903214940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utter GH, Atolagbe OO & Cooke DT (2019) The use of the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, clinical modification and procedure classification system in clinical and health services research. Journal of American Medical Association, 154, 1089. 10.10.1001/jamasurg.2019.2899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe EL, Davis T, Guydish J & Delucchi KL (2005) Mortality risk associated with perinatal drug and alcohol use in California. Journal of Perinatology, 25, 93–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2004) International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision: international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems: tenth revision, 2nd ed. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.