Abstract

Francisella tularensis, the etiological agent of tularemia, is found throughout the Northern hemisphere. After analyzing the F. tularensis genomic sequence for potential variable-number tandem repeats (VNTRs), we developed a multilocus VNTR analysis (MLVA) typing system for this pathogen. Variation was detected at six VNTR loci in a set of 56 isolates from California, Oklahoma, Arizona, and Oregon and the F. tularensis live vaccine strain. PCR assays revealed diversity at these loci with total allele numbers ranging from 2 to 20, and Nei's diversity index values ranging from 0.36 to 0.93. Cluster analysis identified two genetically distinct groups consistent with the current biovar classification system of F. tularensis. These findings suggest that these VNTR markers are useful for identifying F. tularensis isolates at this taxonomic level. In this study, biovar B isolates were less diverse than those in biovar A, possibly reflecting the history of tularemia in North America. Seven isolates from a recent epizootic in Maricopa County, Ariz., were identical at all VNTR marker loci. Their identity, even at a hypervariable VNTR locus, indicates a common source of infection. This demonstrates the applicability of MLVA for rapid characterization and identification of outbreak isolates. Future construction of reference databases will allow faster outbreak tracking as well as providing a foundation for deciphering global genetic relationships.

Tularemia is a disease with extensive geographic occurrence throughout North America, Asia, and Europe and is caused by the bacterium Francisella tularensis. F. tularensis is a small (0.2 to 0.7 μm), highly virulent, gram-negative intracellular pathogen. Tularemia occurs in over 250 mammalian species, including humans (13). Although Francisella is found in arthropod vectors and infected mammal reservoirs, the bacterium can also be isolated from water, animal feces, and mud (10). The disease has been associated with outbreaks in Spain (1997), the Smolensk Province of Russia (1997), and South Dakota (1984), among others. Clinically, tularemia presents in two major forms: ulceroglandular and respiratory. Ulceroglandular tularemia is primarily contracted from arthropod vectors and direct contact with contaminated animals (10). Respiratory tularemia is associated with the inhalation of contaminated aerosols or dust (10).

The genus Francisella has two species, F. tularensis and F. philomiragia. Of these, F. philomiragia is relatively rare, less virulent, and most often associated with water (5). The more common, F. tularensis, has four subspecies, two of which are sometimes referred to as biovars. F. tularensis subsp. tularensis (nearctica, biovar type A) is found primarily in mammalian hosts and arthropod vectors of North America and has also recently been isolated in Europe (4). This subspecies exhibits the highest virulence of the four subspecies. The more moderately pathogenic F. tularensis subsp. palaearctica (holoarctica, biovar type B) is mainly waterborne in Europe and Asia and to a lesser degree in North America (12). F. tularensis subsp. mediaasiatica has only been isolated from locations in the post-Soviet republics of Central Asia (11). Finally, the F. tularensis subsp. novicida type strain was isolated from a Utah water sample in 1950.

The identification of F. tularensis and its subspecies differentiation has traditionally been accomplished by growth characteristics and biochemical analysis (6). F. tularensis subsp. tularensis (biovar A) ferments glycerol and glucose and produces citrulline ureidase (4). F. tularensis subsp. palaearctica (biovar B) ferments only glucose and does not produce citrulline ureidase (4). Recently the capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay has been applied in the detection of human F. tularensis using lipopolysaccharide-specific monoclonal antibodies (3). Studies of the 16S rRNA gene have demonstrated a sequence similarity of at least 98% between the two observed species of Francisella, F. tularensis and F. philomiragia (2), revealing their close phylogenetic relationship and allowing their discrimination. Repetitive extragenic palindromic, enterobacterial repetitive intergenic, and random amplified polymorphic DNA analyses have all proven useful for subspecies discrimination (12). Although these methods provide rapid species and subspecies differentiation, they do not appear applicable to individual strain discrimination (6). A strain-typing tool with greater resolving power would enhance our abilities to differentiate individual strains, detect transmission parameters, and assist in the control of tularemia outbreaks.

Simple sequence repeats or variable-number tandem repeats (VNTRs) have been shown to provide high-level discriminatory power for strain identification (14). This stems from the high mutability of repeat copy number in tandem arrays. Most genomes examined contain numerous VNTRs and, in combination, can be used to develop a robust PCR-based marker typing system. When multiple-locus VNTR analysis (MLVA) is used, great discriminatory capacity and accurate estimation of genetic relationships can be obtained (1, 8, 9). We report here the successful application of MLVA for strain discrimination among a group of 55 North American F. tularensis isolates from locations including California, Oklahoma, Arizona, and Oregon. We have also included the F. tularensis live vaccine strain (LVS) as a reference strain in this analysis. Six novel VNTR loci were identified from genome sequences in this study. In addition, we have used a seventh locus described previously by Johansson et al. (7). Polymorphisms at these loci were then used to resolve the 56 isolates into 39 unique types, which demonstrated higher-level relationships consistent with the current biovar classification.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genomic analysis.

The F. tularensis strain SHU S4 (biovar A) partial genomic sequence was downloaded from the Francisella tularensis website (http://www.medmicro.mds.qmw.ac.uk/ft) and used to identify potential VNTR loci. We screened approximately 120 contigs of available sequences for the presence of tandem repeats (9) by using the DNAstar software program Genequest (Lasergene, Inc., Madison, Wis.). This program locates and displays tandem and nontandemly repeated arrays. Confirmation of the repeated sequence structure was performed using dot plot similarity analysis with the software program Megalign (Lasergene, Inc.).

PCR amplification of VNTR loci.

MLVA primers were developed around 33 potential VNTR loci using the DNAstar program PrimerSelect. However, only six primer sets ultimately amplified polymorphic VNTR loci (Table 1). Reagents used in the PCRs were obtained from Life Technologies. Primers were designed with annealing temperatures from 65 to 61°C, though they were used under annealing conditions of 4°C lower. While shorter primers would work, these high temperatures were chosen for more rapid thermocycling and because of constraints of the AT-rich sequence. The sequence of the seventh primer set was obtained from Johansson et al. (7). An annealing temperature of 64°C was used for the C1-C4 primer set (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

VNTR PCR primer sequences

| Primer name | Forward sequence | Reverse sequence |

|---|---|---|

| FT-V1 | GATTTTTGGGGTTTTCTCTAAACATTTCTAAAATCTGCTTATC | GCAAAACATTATTACCTTATACAGGTTATGGTAGTGGAATC |

| FT-V2 | GTCATACCTTCTTCATGTTTATTAATTACGATGTCTC | GTTCAGGTTAAAACTTTTCTATTGCCCATAGC |

| FT-V3 | GCGGTTTAGCTATTTTCAATATAATTTAAGTTTTTTGTGC | GTTGGTAAGGTTTTTTATTTCTAGTGCTTTTTGATTATCC |

| FT-V4 | GAAATTCACTTACTCAACTGGGAGAATATAGCAAGGC | GCAAATTTATTTTTAGGAGTCCACGTGGATCATC |

| FT-V5 | GTGGTCTTTTAAGCGTCTTAGCAAGCTCGAC | GGGTACCCATCCCATATGTAAGTACAAATGTAGC |

| FT-V6 | GGACCAGAATACTCATACCAAAGTCTATATAATGGTGAAG | GCTCCATATTATTACTCAAAATAAATACCCTGAATATAAAAATATCATC |

| C1-C4 | TCCGGTTGGATAGGTGTTGGATT | CGCGGATAATTTAAATTTCTCATA |

PCR amplification of the seven variable loci from 55 F. tularensis isolates was carried out in the following mixture: 2 mM MgCl2, 1× PCR buffer, 0.1 mM concentrations of deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 1 μM concentrations of R110, R6G, or Tamra phosphoramide fluorescence-labeled dUTPs (Perkin-Elmer Biosystems), 0.5 U of Taq polymerase, 1.0 μl of template DNA, 0.5 μM forward primer, 0.5 μM reverse primer, and filtered sterile water to a volume of 12.5 μl. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 94°C for 5 min and then cycled at 94°C for 30 s, 61 or 56°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s, and 94°C for 30 s for 35 cycles, with a final incubation at 72°C for 5 min.

Isolate DNA.

DNA isolated by heat lysis (8) from a total of 55 F. tularemia strains was obtained from the California Department of Health (32 of the 55 strains), the Oklahoma Department of Health (10 of the 55 strains), and the Arizona Department of Health (7 of the 55 strains) (Table 2). The F. tularensis LVS culture strain was obtained as a gift from John Wright, U.S. Army, Dugway, Utah.

TABLE 2.

F. tularensis strains

| Strain name | Statea-county | Sample information | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| CA-ALA-1 | CA-Alameda | Isolated by animal passage from live ticks | 1981 |

| CA-ALA-2 | CA-Alameda | Human, cutaneous ulcer | 1985 |

| CA-ALP | CA-Alpine | Spermophilus lateralis | 1985 |

| CA-BUT-1 | CA-Butte | Human, type B, blood isolate | 1983 |

| CA-BUT-2 | CA-Butte | Human, node aspirate | 1982 |

| CA-COC-1 | CA-Contra Costa | Human, infected insect bite | 1995 |

| CA-COC-2 | CA-Contra Costa | Human, type B, cervical abscess, Pinote | 1999 |

| CA-COC-3 | CA-Contra Costa | Human, type B, empyema fluid, San Pablo | 1999 |

| CA-ELD | CA-El Dorado | Cat, V940395 | 1994 |

| OR-BND | OR-Bend | Human, sputum | 1991 |

| CA-INY-1 | CA-Inyo | Human, neck node, Bishop | 1984 |

| CA-INY-2 | CA-Inyo | Human, infected insect bite, Bishop | 1985 |

| CA-KRN-1 | CA-Kern | Spermophilus beecheyi, Frazier Park, Camp Tecuya | 1996 |

| CA-KRN-2 | CA-Kern | Gopher, V988 | 1999 |

| CA-LAS | CA-Lassen | Human, epitrochlear node, hunted rabbits | 1984 |

| CA-MAR-1 | CA-Marin | Human, axillary mass | 1998 |

| CA-MAR-2 | CA-Marin | Human, pleural fluid, San Rafael | 1999 |

| CA-PLU | CA-Plumas | Eutamius quadrimaculatus, V96-2017 | 1986 |

| CA-SDI | CA-San Diego | Ground squirrel, V940370 | 1994 |

| CA-SFR | CA-San Francisco | Human, type B, neck mass | 1999 |

| CA-SLO-1 | CA-San Luis Obispo | Microtus californicus, V98-1492 | 1998 |

| CA-SLO-2 | CA-San Luis Obispo | Microtus californicus | 1998 |

| CA-SLO-3 | CA-San Luis Obispo | Human, lymph node aspirate | 1982 |

| CA-SC/SM | CA-Santa Clara or San Mateo | Squirrel, San Mateo or Santa Clara county | 1997 |

| CA-SCL-1 | CA-Santa Clara | Squirrel monkey, Stanford | 1993 |

| CA-SCL-2 | CA-Santa Clara | Human, sputum | 1994 |

| CA-SCR-1 | CA-Santa Cruz | Human, neck lymph node, Watsonville | 1984 |

| CA-SCR-2 | CA-Santa Cruz | Human, blood, has roaming house cat | 1991 |

| CA-SCR-3 | CA-Santa Cruz | Human, cat scratch on finger | 1983 |

| CA-TUL | CA-Tulare | Spermophilus lateralis, V84-1197 | 1984 |

| CA-3245 | CA-Unknown | Unknown | 1997 |

| CA-3603 | CA-Unknown | Cat, V92-451 | 1992 |

| CA-VEN | CA-Ventura | Human, pleural fluid, handled dead rabbit | 1993 |

| CA-YOL-1 | CA-Yolo | Capuchin monkey, type B, UC Davis | 1999 |

| CA-YOL-2 | CA-Yolo | Squirrel monkey, Sacramento Zoo, type B | 1989 |

| CA-YOL-3 | CA-Yolo | Rhesus monkey subman, UC Davis, type B | 1989 |

| CA-YOL-4 | CA-Yolo | Rhesus monkey isolate, UC Davis, type B | 1990 |

| CA-YOL-5 | CA-Yolo | Monkey, Sacramento City Zoo | 1988 |

| AZ-MAR-1 | AZ-Maricopa | Sylvilagus arizonae (cotton rat), spleen | 2000 |

| AZ-MAR-2 | AZ-Maricopa | Sylvilagus auduboni (cottontail rabbit), liver | 2000 |

| AZ-MAR-3 | AZ-Maricopa | Spermophilus variegatus (rock squirrel) | 2000 |

| AZ-MAR-4 | AZ-Maricopa | Tamarin monkey, spleen | 2000 |

| AZ-MAR-5 | AZ-Maricopa | Spermophilus beecheyi, Frazier Park, Camp Tecuya | 2000 |

| AZ-MAR-6 | AZ-Maricopa | Sigmodon arizonae (cotton rat) | 2000 |

| AZ-MAR-7 | AZ-Maricopa | Tamarin monkey, liver | 2000 |

| OK-ADA | OK-Adair | Human | 2000 |

| OK-CAN | OK-Canadian | Human, ulceroglandular, wound culture | 1993 |

| OK-CHK | OK-Cherokee | Human, blood culture, deceased | 2000 |

| OK-HUG | OK-Hughes | Human, blood culture, hunting exposure | 1993 |

| OK-OKL-1 | OK-Oklahoma | Human | 1994 |

| OK-OKL-2 | OK-Oklahoma | Human, blood culture, deceased | 2000 |

| OK-OTW | OK-Ottawa | Human | 1992 |

| OK-TUL-1 | OK-Tulsa | Human, wound culture | 1994 |

| OK-TUL-2 | OK-Tulsa | Human, ulceroglandular, wound culture | 1996 |

| OK-TUL-3 | OK-Tulsa | Human, wound culture | 1993 |

| LVS | LVS, type B, ATCC 29629 |

CA, California; OR, Oregon; AZ, Arizona; OK, Oklahoma.

Automated genotyping.

Fluorescently labeled amplicons were sized by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on an ABI 377 DNA Sequencer. Analysis was accomplished using the Genescan and Genotyper software (9). The PCR product was diluted threefold and mixed 1:1 with equal parts of a 5:1 formamide-dextran blue dye mixture and a size standard prior to electrophoresis. Bioventures ROX 1000 size standards were used for estimating amplicon sizes. Because amplicon sizes determined by migration relative to standards do not always agree with the sizes predicted by direct nucleotide sequence determination, at least one allele for each locus was completely sequenced. All gels were analyzed using ABI filter set A.

Statistical analysis.

Pairwise genetic differences among isolates were estimated using a simple matching coefficient. The clustering method used to evaluate genetic relationships was the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) of the software package PAUP4a (D. Swofford, Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sunderland, Mass.). The diversity (D) for each marker was calculated as D = [1 − Σ(allele frequencies)2] (15).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification and diversity of VNTR markers.

We identified 33 repeated sequence motifs as potential VNTRs from the 1.84 Mb of the available F. tularensis genomic sequence. Five primer pairs failed to support PCR amplification and 22 were amplified but no variation was detected. These failures may be due to the preliminary nature of the available F. tularensis genome sequence. Ultimately, we observed six polymorphic VNTR loci (Table 3) among 55 F. tularensis isolates from California, Oklahoma, Arizona, and Oregon (Table 2) and the LVS.

TABLE 3.

VNTR marker attributes

| Marker locus | Repeat motif | GenBank accession no. | Repeat size (nt)b | SHU S4 strain array size (nt) | Largest array size (nt) | Smallest array size (nt) | No. of alleles | Diversitya |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ft-V1 | TTGGTGAACTTTCTTGCTCTT | AY037288 | 21 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 0.7 |

| Ft-V2 | TTTCTACAAATATCTT | AY037290 | 16 | 18 | 14 | 2 | 10 | 0.53 |

| Ft-V3 | TTAATG | AY037289 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 0.36 |

| Ft-V4 | AATAAGGAT | AY037287 | 9 | 25 | 27 | 3 | 20 | 0.93 |

| Ft-V5 | GT | AY037291 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 0.53 |

| Ft-V6 | TA | AY037286 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0.51 |

| Avg value | 0.53 |

Diversity was determined by the equation D = 1 − Σ(allele frequency)2.

nt, nucleotides.

The allele number in these six loci ranged from two alleles for Ft-V5 and Ft-V6 to 20 alleles for the hypervariable marker FT-V4 (Table 3). This variation may be due to genomic restraints on the production of large repeat arrays, which could confer more flexibility in the variation of small repeats. Previous studies in Yersinia pestis (9) indicate higher copy number repeats exhibit higher allelic variability than lower copy repeats. Likewise, in our study we observed greater variability in loci with higher repeat copy numbers. For example, marker Ft-V2 (Table 3) has a repeat copy number of 18 in the SHU S4 strain and exhibits 10 alleles, while marker Ft-V5 with a copy number of 5 exhibits only 4 alleles (Table 3). In general, we found small repeat motifs were less variable than larger repeat motifs. Marker Ft-V6, with a 2-bp repeat motif, displayed only 2 alleles, while 10 alleles were observed for the 16-bp repeat motif of marker Ft-V2 (Table 3). The repeat motifs displayed a range from 2 to 21 bp in length (Table 3). The smallest array size ranged from 2 bp for marker Ft-V2 to 5 bp for Ft-V3 (Table 3). The largest array size ranged from 6 bp for markers Ft-V5 and Ft-V6 to 27 bp for the hypervariable marker Ft-V4 (Table 3). Whether these observations are generalizable is difficult to discern, given that only six loci have been characterized.

Marker utility is partially determined by observed diversity. Diversity values ranged from 0.36 to 0.96, with an overall average diversity index of 0.53 (Table 3). Markers with high diversity values, such as Ft-V4 with a D of 0.96 (Table 3), may have high mutation rates or be under environmental pressure to diversify. Diverse markers have the greatest discriminatory power for the identification of genetically similar strains, but their capacity would be compromised if selection were important. VNTR marker loci that exhibit relatively low diversity values, such as Ft-V3 with a D of 0.36 (Table 3), may have utility for species, subspecies, and biovar identification.

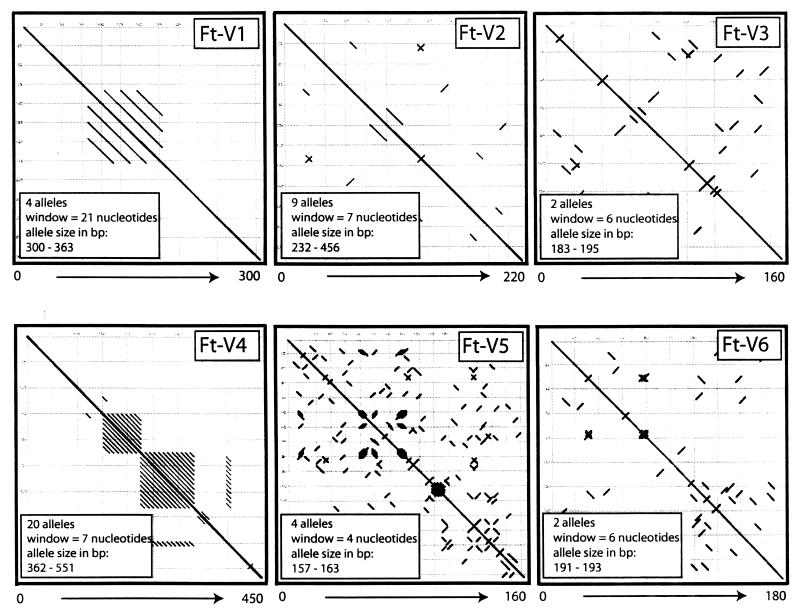

The nucleotide sequence structure of the VNTR loci is well illustrated by dot plot analysis (Fig. 1). The center diagonal line in each panel of Fig. 1 represents the identity of the sequence with itself, while parallel diagonals indicate directly repeated sequences. For example, the nucleotide structure in Ft-V1 has four 21-bp repeats represented by the one diagonal and three parallel lines (Fig. 1). The Ft-V4 marker locus shows a compound repeat structure, where the 9-nucleotide repeat sequence differs within the array. The allele presented in Fig. 1 has eight repeats of AACAAAGAC and 12 repeats of AATAAGGAT. Although three nucleotide differences separate these repeats now, they doubtlessly are derived from a common ancestor. Mutations must have arisen and spread to adjacent repeats until differentiation occurred to create the current mixed-sequence array. Repeat copy number variation among our strain collection is present in both sides of this array, which has been documented by direct DNA sequence analysis (data not presented). Because the repeat size on both sides of the array is the same, such variation is detectable only by nucleotide sequence determination.

FIG. 1.

Dot plot homology at individual marker loci. Dot plot homology analysis was performed using self comparison of each VNTR locus's nucleotide sequence. The panels represent the entire amplicon generated with primers from Table 1. All analyses used a 100% similarity requirement as indicated in each panel. The allele sizes presented in this figure are 321, 248, 183, 479, 159, and 191 bp (Ft-V1 through Ft-V6, respectively).

Genetic relationships among isolates.

In order to understand the genetic relationships among samples, genetic distances among the F. tularensis isolates were calculated using the seven marker loci and then subjected to UPGMA cluster analysis.

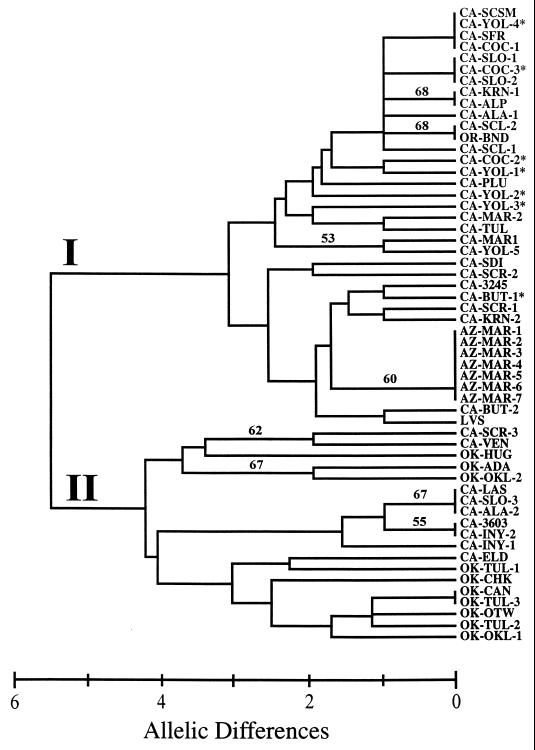

Thirty-nine unique marker allele-size combinations (genotypes) were observed among the 56 isolates. Two major clusters were apparent and subdivisions also occurred within these groups (Fig. 2). These genetic clusters are primarily due to distinct allele frequencies, since no absolute fixed allelic difference exists between cluster I and cluster II (Table 4). The average genetic distance is approximately 5.8 allelic differences (out of 7 possible) between cluster I and cluster II (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Dendrogram based upon six MLVA markers. This dendrogram was generated using UPGMA analysis based upon allele differences among isolates. Letters to the right of each branch correspond to geographical origin: California isolates are identified by a county-specific three letter code, Arizona county isolates are designated by AZ, and Oklahoma isolates are listed as OK. Numbers associated with branch lengths represent bootstrap values using 1,000 simulations. An asterisk designates strains of known F. tularensis biovar B classification.

TABLE 4.

F. tularensis allele size

| Cluster and strain | Allele size (bp)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ft-V1 | Ft-V2 | Ft-V3 | Ft-V4 | Ft-V5 | Ft-V6 | C1-C4a | |

| Cluster I | |||||||

| CA-SC/SM | 303 | 230 | 183 | 434 | 157 | 191 | 300 |

| CA-YOL-4 | 303 | 230 | 183 | 434 | 157 | 191 | 300 |

| CA-SFR | 303 | 230 | 183 | 434 | 157 | 191 | 300 |

| CA-COC-1 | 303 | 230 | 183 | 434 | 157 | 191 | 300 |

| CA-SLO-1 | 303 | 230 | 183 | 425 | 157 | 191 | 300 |

| CA-COC-3 | 303 | 230 | 183 | 425 | 157 | 191 | 300 |

| CA-SLO-2 | 303 | 230 | 183 | 425 | 157 | 191 | 300 |

| CA-KRN-1 | 303 | 230 | 183 | 389 | 157 | 191 | 300 |

| CA-ALP | 303 | 230 | 183 | 389 | 157 | 191 | 300 |

| CA-ALA-1 | 303 | 230 | 183 | 407 | 157 | 191 | 300 |

| CA-SCL-2 | 303 | 230 | 183 | 416 | 157 | 191 | 300 |

| OR-BND | 303 | 230 | 183 | 416 | 157 | 191 | 300 |

| CA-SCL-1 | 303 | 230 | 183 | 443 | 157 | 191 | 300 |

| CA-COC-2 | 303 | 230 | 183 | 425 | 159 | 191 | 300 |

| CA-YOL-1 | 303 | 230 | 183 | 434 | 159 | 191 | 300 |

| CA-PLU | 345 | 230 | 183 | 425 | 157 | 191 | 300 |

| CA-YOL-2 | 303 | 230 | 183 | 407 | 155 | 191 | 300 |

| CA-YOL-3 | 282 | 230 | 183 | 407 | 159 | 191 | 300 |

| CA-MAR-2 | 282 | 230 | 183 | 452 | 157 | 191 | 300 |

| CA-TUL | 282 | 230 | 183 | 470 | 157 | 191 | 300 |

| CA-MAR-1 | 324 | 230 | 183 | 461 | 159 | 191 | 300 |

| CA-YOL-5 | 324 | 230 | 183 | 461 | 157 | 191 | 300 |

| CA-SDI | 324 | 230 | 183 | 551 | 159 | 193 | 300 |

| CA-SCR-2 | 345 | 230 | 183 | 488 | 159 | 193 | 300 |

| CA-3245 | 324 | 230 | 183 | 443 | 157 | 193 | 300 |

| CA-BUT-1 | 324 | 230 | 183 | 479 | 157 | 193 | 300 |

| CA-SCR-1 | 345 | 230 | 183 | 479 | 157 | 193 | 300 |

| CA-KRN-2 | 303 | 230 | 183 | 479 | 157 | 193 | 300 |

| AZ-MAR-1 | 345 | 230 | 183 | 470 | 157 | 193 | 300 |

| AZ-MAR-2 | 345 | 230 | 183 | 470 | 157 | 193 | 300 |

| AZ-MAR-3 | 345 | 230 | 183 | 470 | 157 | 193 | 300 |

| AZ-MAR-4 | 345 | 230 | 183 | 470 | 157 | 193 | 300 |

| AZ-MAR-5 | 345 | 230 | 183 | 470 | 157 | 193 | 300 |

| AZ-MAR-6 | 345 | 230 | 183 | 470 | 157 | 193 | 300 |

| AZ-MAR-7 | 345 | 230 | 183 | 470 | 157 | 193 | 300 |

| CA-BUT-2 | 282 | 230 | 183 | 371 | 157 | 193 | 300 |

| LVS | 282 | 230 | 183 | 443 | 157 | 193 | 300 |

| Cluster II | |||||||

| CA-SCR-3 | 282 | 342 | 195 | 497 | 161 | 193 | 330 |

| CA-VEN | 282 | 327 | 195 | 506 | 161 | 193 | 330 |

| OK-HUG | 282 | 342 | 195 | 434 | 157 | 193 | ? |

| OK-ADA | 282 | 358 | 195 | 443 | 157 | 191 | 330 |

| OK-OKL-2 | 282 | 230 | 195 | 461 | 157 | 191 | 330 |

| CA-LAS | 282 | 214 | 183 | 362 | 159 | 193 | 330 |

| CA-SLO-3 | 282 | 214 | 183 | 362 | 159 | 193 | 330 |

| CA-ALA-2 | 282 | 214 | 183 | 362 | 159 | 193 | 330 |

| CA-3603 | 282 | 214 | 183 | 371 | 159 | 193 | 330 |

| CA-INY-2 | 282 | 214 | 183 | 371 | 159 | 193 | 330 |

| CA-INY-1 | 282 | 214 | 183 | 371 | 163 | 195 | 330 |

| CA-ELD | 282 | 423 | 195 | 524 | 159 | 193 | 330 |

| OK-TUL-1 | 282 | 408 | 195 | 533 | 159 | 193 | ? |

| OK-CHK | 324 | 374 | 195 | 452 | 159 | 193 | 330 |

| OK-CAN | 303 | 374 | 195 | 398 | 159 | 193 | ? |

| OK-TUL-3 | 303 | 358/342b | 195 | 434/452b | 159 | 193 | ? |

| OK-OTW | 303 | 358 | 195 | 515 | 159 | 193 | ? |

| OK-TUL-2 | 303 | 358 | 195 | 452 | 159 | 193 | ? |

| OK-OKL-1 | 303 | 390 | 195 | 461 | 159 | 193 | 330 |

As reported in Johansson et al. (7). ?, amplicon size data absent due to PCR amplification failure.

Markers displayed two allele sizes in this strain.

The 38 California isolates were found clustered in both of the two major subdivisions: clusters I and II (Fig. 2). California strains CA-YOL-5, CA-YOL-2, CA-YOL-3, CA-YOL-1, CA-YOL-4, CA-SFR, and CA-BUT-1 were previously identified as F. tularensis subsp. tularensis biovar B (Table 1) and are all found in cluster I (Fig. 2). The F. tularensis LVS also grouped within cluster I (Fig. 2) and is of known biovar B classification. The 37 strains within cluster I assembled into three discernible though weakly supported groups (Fig. 2). The average distance among these cluster I subgroups is approximately three markers. California isolates CA-SC/SM, CA-YOL-4, CA-SFR, and CA-COC-1 showed 100% identity, as did CA-SLO-1, CA-COC-3, and CA-SLO-2 (Fig. 2). Within cluster I, the Oregon isolate (OR-BND) showed 100% identity (Fig. 2) with the isolate from Santa Clara County (CA-SCL-2); both strains were isolated from sputum collections (Table 1).

Cluster II includes 9 California strains of unknown biovar type and 10 Oklahoma strains (biovar A), which assembled into three apparent groups (Fig. 2). Examination of the California spatial distribution within both major clusters reveals completely overlapping geographic locations (Fig. 2). For example, isolates from San Luis Obispo County are found in both major clusters (CA-SLO-1 and CA-SLO-3), as are samples from Alameda County (CA-ALA-1 and CA-ALA-2).

The tularemia cases represented by the California isolates group into two separate clusters (I and II), suggesting the presence of a very subdivided reservoir of F. tularensis biovars in this region. Temporal overlap is evident as both major clusters contain samples obtained throughout the 1980s and 1990s, ruling out a separation in time (Table 1). Although the samples are well separated in collection date, there appear to be few genetic changes occurring over this period. These casual observations were combined with a formal statistical analysis using a Mantel test (significance level of P > 0.05; data not shown) and indicated that geographic and temporal data are not correlated with the genetic type. The great diversity and nongeographic partitioning of this diversity suggest a complex disease cycle in California involving both biovars A and B. Either the pathogen is frequently transported into the regions or a highly diverse reservoir exists to generate distinctive outbreaks, biovars notwithstanding.

In contrast to the California strains, the year 2000 tularemia cases clustered in Maricopa County, Ariz., are related, indeed identical, to each other when analyzed using our methods. Seven isolates of F. tularensis subsp. haloaretica (biovar B) from this epizootic showed 100% identity and assembled within the third group of cluster I (Fig. 2). The identity is apparent even with marker Ft-V4, which is highly diverse. The lack of any Ft-V4 allelic difference is consistent with a recent common clonal ancestor. The absence of allelic variation among the Arizona strains strongly supports a point-source epidemiological model (where the infection spreads from a single origin) rather than a model with multiple sources. Host victims were a mixture of captive and wild animals, but these data do not indicate whether the disease spread from captive to wild animals or vice versa. However, further characterization of the resident animal reservoir could provide evidence to evaluate these two alternate hypotheses.

Historically, Oklahoma represents one of the three largest F. tularensis reservoirs in the United States. The 10 Oklahoma strains and 9 California strains clustered together into two minor groups within cluster II (Fig. 2). California strains CA-LAS, CA-SLO-3, and CA-ALA-2 appeared identical within the second minor group of cluster II, as did strains CA-3603 and CA-INY-2 (Fig. 2). Of the Oklahoma strains, only OK-CAN and OK-TUL-3 showed 100% identity (Fig. 2). It should be noted that markers Ft-V2 and Ft-V4 each displayed two allele sizes in the aforementioned strains (Table 4). It is possible that this result is due to strain contamination; this result is reported in Table 4 but was not used for the phylogenetic analysis shown in Fig. 2. All Oklahoma isolates appear loosely affiliated with the nine California strains found in cluster II (Fig. 2). While all 10 of the Oklahoma isolates are F. tularensis subsp. tularensis (biovar A), the VNTRs easily divided them into nine unique genotypes. The observed marker differences among Oklahoma samples are most consistent with a model of multiple emergences from an animal reservoir. A somewhat diverse reservoir is likely to exist in Oklahoma, given these unique types.

Previous studies identified a marker (C1-C4) that allows discrimination between F. tularensis biovars A and B (7). Analysis of our strains at this locus revealed two alleles, which was consistent with the previous study and our knowledge of the biovar classification of F. tularensis (Table 4). The allelic variation that we observed in this marker clearly supports our cluster I and cluster II categories and validates that they represent biovar A (cluster II) and biovar B (cluster I).

In our study we found that cluster II isolates are much more diverse than cluster I isolates (Fig. 2). Because all of our isolates are from North America, this difference may reflect the history of tularemia on this continent rather the inherent diversity of the two types. Biovar B may be a historically recent import to North America and, hence, its isolates are less diverse due to a colonization bottleneck. Future comparative studies of European and Asian F. tularensis isolates will be a test of this hypothesis.

The application of MLVA to the genetic characterization of F. tularensis isolates has provided significant strain discriminatory power. Using relatively few markers against these North American isolates, our data reflect the successful application of MLVA in discriminating between major Francisella groups consistent with the current biovar classifications (Fig. 2). Although subspecies classification appears possible with MLVA, this approach is most powerful when applied to the rapid discrimination between individual outbreak strains for epidemiological analysis. The contrast between the Arizona and the Oklahoma or California isolates illustrates this well. Because MLVA data can be standardized (Table 4), they are easily compared to data generated at dispersed laboratories, unlike other methods commonly employed. In this regard, these data are similar to nucleotide sequence data. Future studies across multiple laboratories will be able to directly compare MLVA data with the results reported here. A multilaboratory electronic database will allow for fast characterization and identification of F. tularensis isolates from outbreaks and provide the foundation for deciphering global genetic relationships.

It is known that VNTRs provide a potential mechanism for metabolic regulation as well as offering great potential for antigenic variation and environmental adaptation (14). While these studies do not address such issues, our identification and characterization of VNTR variation provides a starting point for such research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Department of Energy NN20-CBNP program, the National Institutes of Health, and the Cowden Endowment in Microbiology.

We thank Powell Gammill for providing DNA from the Maricopa County cases, Kristy Bradley for providing DNA from the Oklahoma State Health Department, and May Chu for information concerning the biovar classifications. We also thank Anders Sjöstedt for prepublication discussions of VNTR strain typing in F. tularensis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adair D M, Worsham P L, Hill K K, Klevytska A M, Jackson P J, Friedlander A M, Keim P. Diversity in a variable-number tandem repeat from Yersinia pestis. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1516–1519. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.4.1516-1519.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forsman M, Kuoppa K, Sjostedt A, Tarnvik A. Use of RNA hybridization in the diagnosis of a case of ulceroglandular tularemia. Eur J Microbiol Infect Dis. 1990;9:784–785. doi: 10.1007/BF02184697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grunow R, Splettstoesser W, McDonald S, Otterbein C, O'Brian T, Morgan C, Aldrich J, Hofer E, Finke E-J, Meyer H. Detection of Francisella tularensis in biological specimens using a capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, an immunochromatographic handheld assay, and a PCR. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2000;7:86–90. doi: 10.1128/cdli.7.1.86-90.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gurycova D. First isolation of Francisella tularensis subsp. tularensis in Europe. Eur J Epidemiol. 1998;14:797–802. doi: 10.1023/a:1007537405242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hollis D G, Weaver R E, Steigerwalt A G, Wenger J D, Moss C W, Brenner D J. Francisella philomiragia comb. nov. (formerly Yersinia philomiragia) and Francisella tularensis biogroup novicida (formerly Francisella novicida) associated with human disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1601–1608. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.7.1601-1608.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johansson A, Berglund L, Eriksson U, Goransson I, Wollin R, Forsman M, Tarnvik A, Sjostedt A. Comparative analysis of PCR versus culture for diagnosis of ulceroglandular tularemia. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:22–26. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.1.22-26.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johansson A, Ibrahim A, Goransson I, Eriksson U, Gurycova D, Clarridge III J E, Sjostedt A. Evaluation of PCR-based methods for discrimination of Francisella species and subspecies and development of a specific PCR that distinguishes the two major subspecies of Francisella tularensis. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:4180–4185. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.11.4180-4185.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keim P, Price L B, Klevytska A M, Smith K L, Schupp J M, Okinaka R, Jackson P J, Hugh-Jones M E. Multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis reveals genetic relationships within Bacillus anthracis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2928–2936. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.10.2928-2936.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klevytska A M, Price L B, Schupp J M, Worsham P L, Wong J, Keim P. Identification and characterization of variable-number tandem repeats in the Yersinia pestis genome. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:3179–3185. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.9.3179-3185.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H. Manual of clinical microbiology. 7th ed. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olsufjev N G, Meshcheryakova I S. Subspecific taxonomy of Francisella tularensis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1983;33:872–874. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Puente-Redondo V A, Garcia del Blanco N, Gutierrez-Martin C B, Garcia-Pena F J, Rodriguez Ferri E F. Comparison of different PCR approaches for typing of Francisella tularensis strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1016–1022. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.3.1016-1022.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sjostedt, A. Family XVII. Francisellacae, genus I. Francisella. In D. J. Brenner (ed.), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, 2nd ed., vol. 2. Springer-Verlag, New York, N.Y., in press.

- 14.van Belkum A, Scherer S, van Alphen L, Verbrugh H. Short-sequence DNA repeats in prokaryotic genomes. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:275–293. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.275-293.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weir B S. Genetic data analysis: methods for discrete population genetic data analysis. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates, Inc.; 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]