Abstract

Microphysiological systems (MPS) or tissue chips/organs-on-chips (OoCs) are novel in vitro models that emulate human physiology at the most basic functional level. In this review, we discuss various hurdles to widespread adoption of MPS technology focusing on issues from multiple stakeholder sectors – e.g., academic MPS developers, commercial suppliers of platforms, the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries, and regulatory organizations. Broad adoption of MPS technology has thus far been limited by a gap in translation between platform developers, end-users, regulatory agencies, and the pharmaceutical industry. In this brief review we offer a perspective on the existing barriers and how end-users may help surmount these obstacles to achieve broader adoption of MPS technology.

Keywords: microphysiological systems, microfluidics, bioengineering, induced pluripotent stem cells, drug development

Introduction

Drug discovery and development involves translating fundamental biomedical scientific research into the development of diagnostics and therapeutics for patients struggling under the burden of disease. Preclinical drug development and design has long relied on data from conventional in vitro models such as two-dimensional (2D) cell culture systems, and in vivo animal models such as rodents (mice and rats). 2D cell culture systems, while easily manipulated and rapidly scalable, generally lack natural tissue and organ 3D structure and organization, perfusion, and necessary microenvironmental cues. This has led many to doubt the physiological and clinical relevance of findings obtained from simplified 2D cellular models (Ingber 2020).

In addition to in vitro cell culture systems, the drug discovery and evaluation process has also relied heavily on preclinical data obtained from in vivo animal models such as mice, rats, non-human primates, pigs, and dogs. Animal models, such as mice, have been used to study drug toxicity, drug pharmacokinetic (PK) studies i.e., how drug levels change over time in flowing blood, as well as drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) profiling. While some animal models have been useful in understanding disease (Friese, Montalban et al. 2006), it has become increasingly clear that animal models may not accurately replicate human-specific drug toxicities(Watanabe, Furukawa et al. 2000) and specific off-target effects due to fundamental species differences in immune response, metabolism, pathophysiology, and the microbiome (Tagle 2019). The deficiencies of current in vivo and in vitro models to accurately predict human drug response is illustrated by the cost (roughly $2.6 billion dollars) and timeframe (over 10 years) by which it takes to develop a single drug from initial lead compound discovery to successful approval by the FDA (Alex, Harris et al. 2016, DiMasi, Grabowski et al. 2016, Wagner, Dahlem et al. 2018, Wagner, Dahlem et al. 2018). The extensive cost and timeframe to develop drugs and therapeutics is largely due to high attrition rate of candidate therapies due to compound toxicity in early preclinical stages and lack of efficacy in later clinical stages (Arrowsmith 2011, Arrowsmith 2011, Arrowsmith and Miller 2013, Jardim, Groves et al. 2017, Parasrampuria, Benet et al. 2018). Indeed, it is estimated that 60% of these failures are due to lack of efficacy, while 30% are due to toxicity (Waring, Arrowsmith et al. 2015). The 80% clinical attrition rate (Waring, Arrowsmith et al. 2015) of potentially valuable therapeutics is even higher for diseases affecting the central nervous system (Gribkoff and Kaczmarek 2017), diseases affecting pediatric populations (Blumenrath, Lee et al. 2020), and rare diseases (Low and Tagle 2016, Blumenrath, Lee et al. 2020).

It is apparent that the drug development field needs alternative models to circumvent the extensive attrition in drug development so that safe and effective therapies are able to quickly reach more patients. Microphysiological systems (MPS), also called ‘tissue-chips’ or organs-on-chips (OoCs), are a technology developed over the last decade that could offer a promising solution to the current challenges. MPS are defined by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s Alternative Methods Working Group as in vitro platforms containing human or animal cells, organ/tissue-derived explants, and/or self-assembling organoids within microenvironmental niches capable of facilitating physiologically meaningful biochemical, mechanical and electrical tissue/organ level responses. MPS are small (some are the size of a USB thumb drive) biomimetic devices containing functionally modeled organ/tissue units. They have three main features that separate them from other in vitro models including a 3D tissue architecture (rather than 2D cell layers); multiple cell type composition; and the inclusion of biomechanical forces such as stretch forces on lung tissues during the breathing process or the hemodynamic shear forces present in vascularized tissues (Low, Mummery et al. 2020). These attributes allow MPS to accurately recapitulate many key aspects of human organ structure and function, including biochemical and physiochemical microenvironmental cues, vascular perfusion, microfluidic flow, human organ innervation, and proper establishment of growth hormone gradients, cytokines and other signaling molecules and pathways (Ronaldson-Bouchard and Vunjak-Novakovic 2018).

MPS systems are now known to accurately replicate pathophysiological drug responses observed in humans that were not detected in preclinical animal studies (Ingber 2020). For example, a human blood vessel MPS was able to reproduce the thrombotic toxicities noted in patients treated with a novel monoclonal antibody therapeutic even though such toxicity was never noted in preclinical animal models (Barrile, van der Meer et al. 2018). In addition, a human kidney proximal tubule MPS model was able to accurately replicate cisplatin toxicities, as cisplatin is metabolized through a human-specific Pgp efflux transporter not expressed in animals and had not previously been replicated in animal models (Jang, Mehr et al. 2013). MPS systems are not only able to accurately replicate pathophysiological human drug responses; they are also able to faithfully recapitulate species-specific drug responses. Researchers have developed rat, dog, and human liver tissue chips with species-specific liver cells under physiologically relevant flow, capable of detecting species-specific hepatotoxicity of several known hepatotoxic drugs and experimental compounds (Jang, Otieno et al. 2019). Multispecies chips could serve as a useful platform for prediction of species-specific liver toxicity, as well as help identify species-specific differences in drug metabolism (Jang, Otieno et al. 2019) Additionally, MPS are also highly responsive to the 3R principles of animal use in biomedical research – reduction, refinement, replacement – whereby the use of animal models in preclinical studies might be significantly reduced (Curzer, Perry et al. 2016, Low, Sutherland et al. 2020).

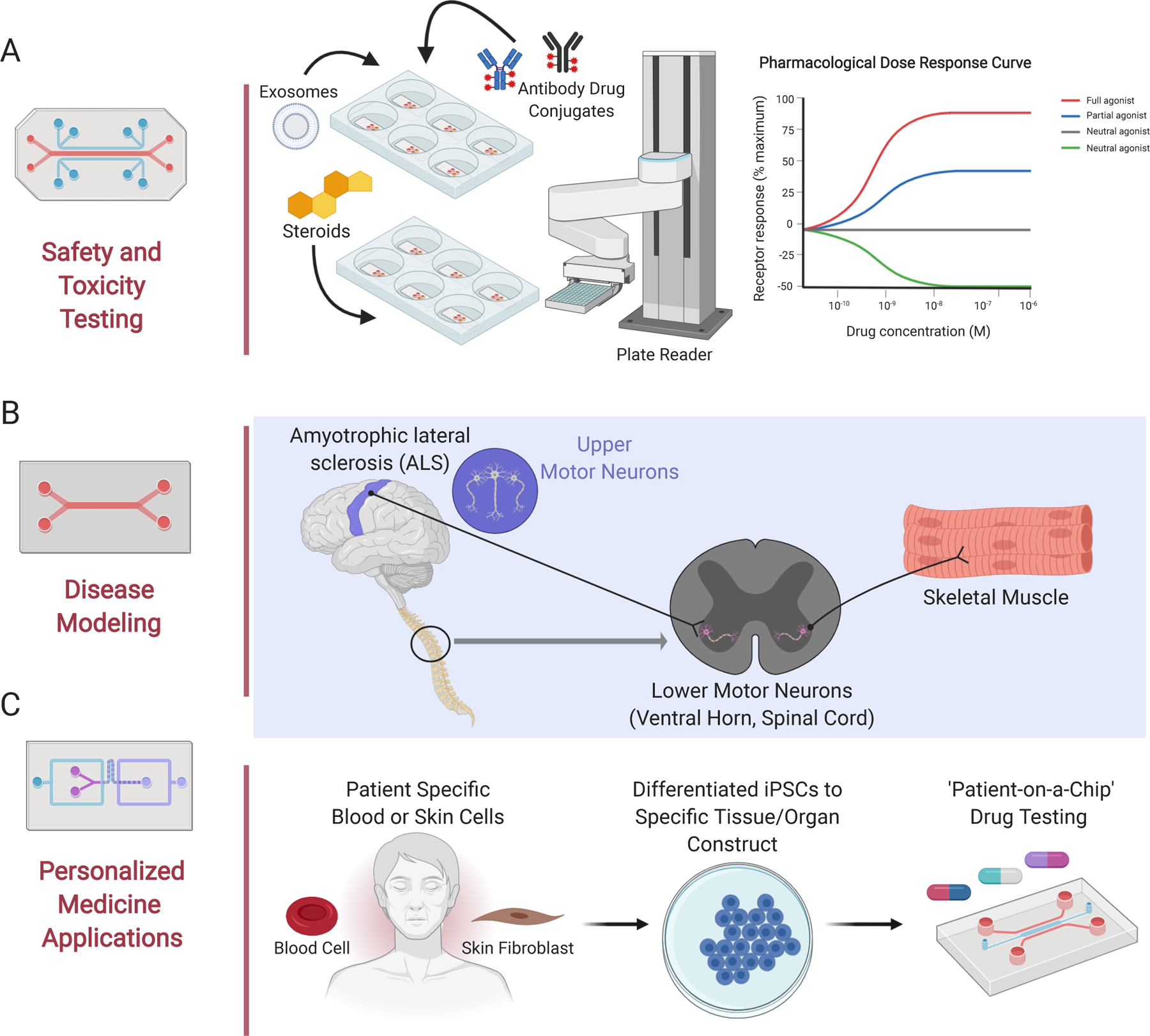

With many significant advantages over current in vitro and in vivo models, MPS platforms are poised as better predictive in vitro tools to expedite the drug development process (Ekert, Deakyne et al. 2020, Low, Mummery et al. 2020), including their use in the preclinical phase for early lead compound target validation and therapeutic safety and toxicity testing (shown in Fig. 1a) (Apati, Varga et al. 2019, Rudmann 2019, Tagle 2019, Heringa, Park et al. 2020). In addition to their potential role in preclinical drug development, MPS can be used for modeling of both common and rare diseases (shown in Fig. 1b) (Blumenrath, Lee et al. 2020). Currently, many common and rare diseases have been successfully modeled including diseases such as Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (a progressive neurodegenerative disease) (shown in Fig. 1b) (Osaki, Uzel et al. 2018), Barth syndrome (a rare pediatric cardiomyopathy) (Wang, McCain et al. 2014), and Hutchinson Gilford Progeria Syndrome (rare and rapid progressive aging disorder) (Atchison, Zhang et al. 2017, Ribas, Zhang et al. 2017). In addition to disease modeling, MPS systems have also been employed to assess environmental exposures (Chang, Weber et al. 2017, Truskey 2018, Liu, Koo et al. 2019), study infectious diseases such as those caused by viruses (Tang, Abouleila et al. 2020), and probe the role of the microbiome’s interaction within the gut-liver-brain axis (Hawkins, Casolaro et al. 2020). Currently, MPS are being tested for their potential to inform stratification of patient subpopulations in clinical trials, based on drug response (Blumenrath, Lee et al. 2020), as well as for additional personalized medicine applications (shown in Fig. 1c) (van den Berg, Mummery et al. 2019).

Fig. 1. Organ-on-Chip End Uses.

Organs-on-chips (MPS, Tissue Chips) have a variety of end uses, including (A) safety and toxicity testing*, (B) disease modeling of both common and rare diseases, and (C) applications for personalized medicine such as ‘you-on-a-chip’ made with patient specific stem blood or skin cells that can be reprogrammed into induced pluripotent stem cells, and further differentiated into a variety of tissue and organ constructs. *NB. the robot arm depicted in Fig 1A is typically used in high throughput screens. MPS platforms are currently employed in low-to-moderate throughput applications (Created using BioRender).

Within the last 10 years of MPS technological innovation, there has been development of MPS models of nearly every major human organ (Ronaldson-Bouchard and Vunjak-Novakovic 2018) including the brain (Pamies, Barreras et al. 2017, Liu, Koo et al. 2019), blood-brain-barrier (BBB) (Ahn, Sei et al. 2020, Brown, Faley et al. 2020, Lee and Leong 2020), skeletal (Truskey 2018, Zhang, Hong et al. 2018, Davis, Yen et al. 2019) and cardiac muscle (Lind, Busbee et al. 2017, Lind, Yadid et al. 2017, Stein, Mummery et al. 2020), liver (Li, George et al. 2018, Ribeiro, Yang et al. 2019), vasculature (Herron, Hansen et al. 2019, Paek, Park et al. 2019), kidney (Maass, Sorensen et al. 2019, Chapron, Chapron et al. 2020, Phillips, Grandhi et al. 2020, Sakolish, Chen et al. 2020), skin (Hardwick, Betts et al. 2020, Kim, Jeon et al. 2020, Kwak, Jin et al. 2020), gut, intestine and colon (Kim, Li et al. 2016, Hawkins, Casolaro et al. 2020, Sontheimer-Phelps, Chou et al. 2020), and bone (Romero-Lopez, Li et al. 2020). MPS platforms have also been linked to form multi-organ systems to more accurately understand and mechanistically dissect drug and therapeutic human systemic response (Vernetti, Gough et al. 2017, Xiao, Coppeta et al. 2017, Edington, Chen et al. 2018, Herland, Maoz et al. 2020, Novak, Ingram et al. 2020).

An evaluation of the field in 2019 predicted a 10–26% reduction in pharmaceutical research and development (R&D) costs upon adoption of MPS technology (Franzen, van Harten et al. 2019). However, despite their disruptive technological potential, there are still many hurdles that remain towards widespread MPS adoption. A recent t4 (Transatlantic think tank for toxicology) report from a variety of experts in different stakeholder areas suggests that the MPS field is still in its infancy (Marx, Akabane et al. 2020). The authors of the report describe the life cycle of MPS as consisting of four major elements 1) academic invention and model development, 2) model qualification by supplier industries, 3) ‘fit for purpose’ assay qualification and adoption by pharmaceutical industries for candidate drug testing, and 4) regulatory acceptance of validated MPS drug candidate assays based on specific context of use (CoU) (Marx, Akabane et al. 2020). In order to push the maturity of MPS technologies, defining the CoU for MPS is becoming increasingly critical. CoU is defined by the FDA-NIH BEST (Biomarkers, EndpointS, and other Tools) resource as a “A statement that fully and clearly describes the way the medical product development tool will be used and the medical product development-related purpose of use” (2016). Therefore, clearly defining the CoU of each MPS platform identifies where it can provide the most informative data. Current contexts of use for microphysiological systems include toxicology screening, ADME applications, pharmacodynamic modeling, and drug safety and efficacy testing (Marx, Akabane et al. 2020).

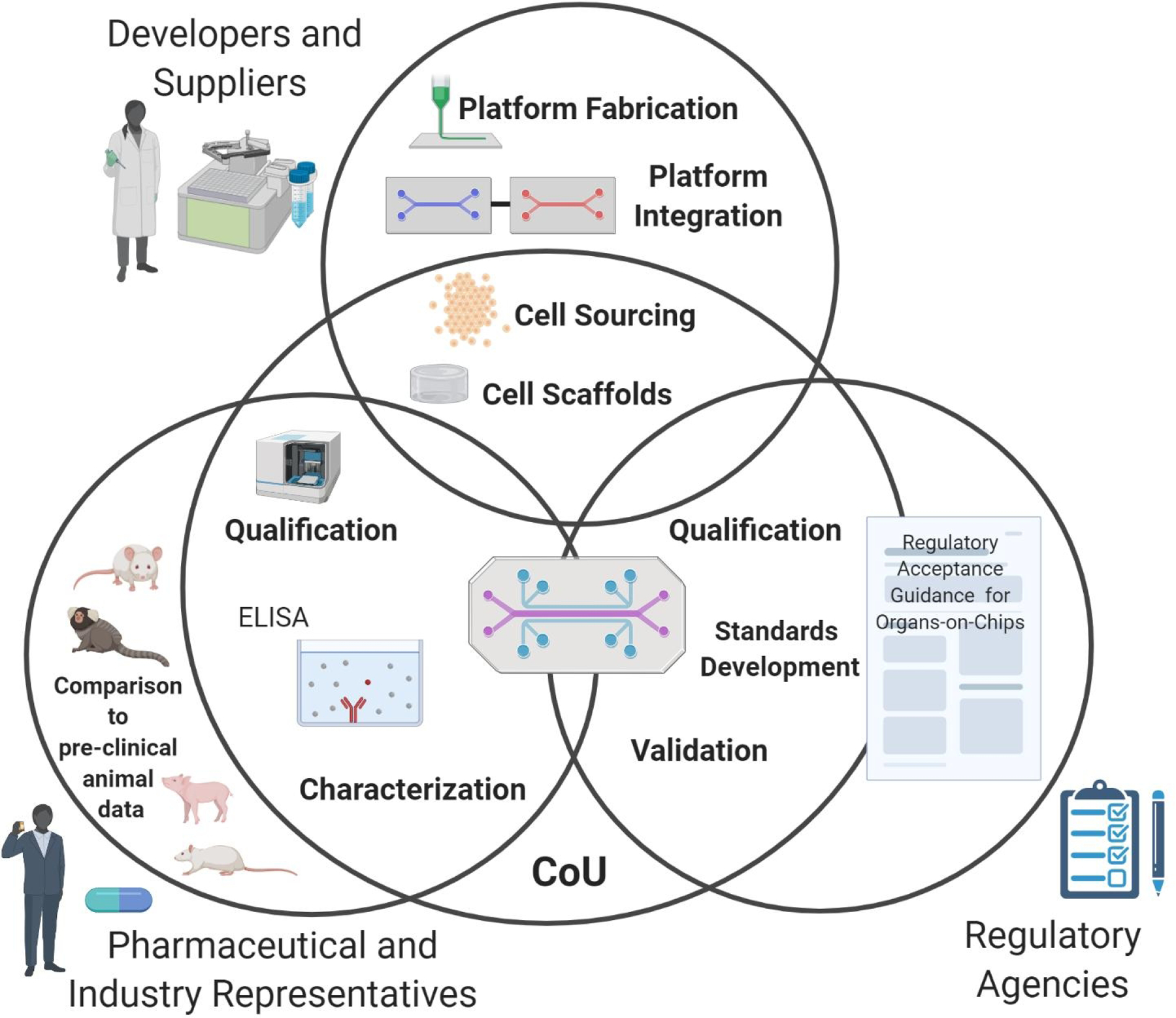

In this review, we highlight some of the most pressing hurdles to the adoption of MPS technology based on the stakeholder sectors described in the t4 report including developers and suppliers, the pharmaceutical industry, and regulatory bodies (shown in Fig. 2) (Marx, Akabane et al. 2020). For the purpose of this review, we denote suppliers to comprise of commercial MPS vendors and providers of MPS devices, biological models and cell sources, methods, and/or assays (Marx, Akabane et al. 2020). Ultimately, end-users and stakeholders must collaborate closely to address these challenges as a community and advance MPS platform adoption and acceptance across the field (Marx, Akabane et al. 2020).

Fig. 2. Hurdles to Adoption of Organ-on-Chip Systems Based on Stakeholder Group.

There are a variety of stakeholder groups that must communicate effectively to advance adoption of MPS technology. The hurdles to adoption of this technology vary depending on stakeholder sector. For example, developers and suppliers face hurdles such as proper cell sourcing, which cell scaffolds to use, platform fabrication and how to integrate different tissue and organ-construct platforms (section 1). The pharmaceutical industry faces different hurdles including the need to qualify MPS systems for specific contexts of use (CoU) and specific assays. The pharma industry is also interested in cross comparison of pre-clinical animal data, clinical human data, and tissue chip data (detailed in section 2). Similarly, regulatory agencies are also interested in qualifying MPS platforms for specific CoU. Regulatory bodies also require additional validation and standards development to surmount adoption hurdles (detailed in section 3). (Created using BioRender).

1). MPS Developer and Supplier Hurdles

Over the last 15 years, MPS models plus their methodology, and analytical tests have progressed rapidly from proof-of-concept studies in academic laboratories to implementation and use of commercially available platforms in a myriad of research areas and global commercial enterprises. Global examples of MPS spin-out companies from universities include Emulate from the Wyss Institute at Harvard University, Mimetas from Leiden University, TissUse from the Technishe Universität Berlin, and Nortis from the University of Washington (Zhang and Radisic 2017, Marx, Akabane et al. 2020). Additionally, a number of MPS companies have licensed MPS technology from academic research, including Hesperos MPS(from Cornell University and the University of Central Florida), CN Bio (licensing the PhysioMimix platform from MIT), and InSphero (licensing a multi-tissue plate-based platform from the ETH Zurich) (Marx, Akabane et al. 2020). A 2017 survey identified 28 MPS suppliers within various market segments (Zhang and Radisic 2017). A dozen more companies have since entered the arena, with the MPS market anticipated to grow by 38% yearly to a total of US $117 million per year by 2022 (market analysis prediction by Yole Développement). However, despite their disruptive potential, MPS developers and suppliers are still facing a variety of scientific and technological challenges, including standardization.

Cell Sourcing.

To create robust, reliable, and reproducible MPS platforms, the cells seeded onto MPS devices must meet the same quality metrics as the platforms themselves. Currently, three main types of cells are used within MPS devices - primary cells taken from the human donor organs; human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) differentiated from skin fibroblasts or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (Takahashi and Yamanaka 2006, Takahashi, Okita et al. 2007, Takahashi, Tanabe et al. 2007), and commercially available cell lines, which can be both primary and stem cell progenitors (Low, Mummery et al. 2020). There are advantages and disadvantages to each cell source. Primary cells, collected from patient organ biopsies, are functionally and phenotypically mature, unlike stem cell sources. However, primary cells are often difficult to collect, finite in amount and cannot be expanded in culture. Additionally, primary cell sampling variabilities between collection sites can alter the corresponding data.

To surmount these barriers, many researchers have turned to the use of human induced pluripotent stem cells (hIPSCs), derived from patient skin or blood samples (which are less invasive than organ biopsies). hIPSCs provide a potentially unlimited and renewable patient-specific cell source, and can be specifically differentiated into multiple cellular lineages, tissue types and organ constructs (Takahashi and Yamanaka 2006, Takahashi, Okita et al. 2007, Takahashi, Tanabe et al. 2007). hIPSCs can be taken from both healthy and diseased populations, providing a way to create MPSs modeling unique/patient-specific tissue and disease phenotypes (Low, Mummery et al. 2020). In addition, hIPSC technology is amenable to gene editing and the creation of patient-specific isogenic (genetically identical) cell lines, with or without specific disease-modifying mutations to allow modeling of monogenic diseases. The use of isogenic cell lines permits mechanistic analyses of disease process and promotes target-specific development of new therapeutics (Fabre, Delsing et al. 2019). However, hIPSC technology is relatively novel and still a topic of extensive research, with drawbacks such as variability in differentiation protocols and potentials (Nishizawa, Chonabayashi et al. 2016), the finding that certain resulting cells retain ‘epigenetic memory’ of donor tissues (Kim, Doi et al. 2010), and the limitations of phenotypic and functional maturity of some cell types (Rajamohan, Matsa et al. 2013). In addition, the derivation of hPSCs can be expensive and time consuming ; for example, differentiation of forebrain interneurons from hPSCs takes up to 7 months, mimicking human neural development (Nicholas, Chen et al. 2013).

To circumvent some of these issues, researchers have relied on commercially available cell lines (such as the American Type Culture Collection) that have clear, reliable, and reproducible cell culture protocols and are easy to culture, transfect and genetically manipulate. However, commercial cell lines are often immortalized, whereby the line has been genetically manipulated to proliferate indefinitely through evasion of cellular senescence mechanisms, which can lead to biologically inaccurate or incomplete data. Clearly, the cellular source within the MPS platform is an important factor of consideration for tissue chip developers (Sakolish, Weber et al. 2018, Liu, Sakolish et al. 2020, Marx, Akabane et al. 2020).

Cell Scaffolds & Platform Fabrication.

Cells require structure in the form of scaffolds or extracellular matrices (ECM) (Verhulsel, Vignes et al. 2014, Terrell, Jones et al. 2020) for proper cellular architecture, support, and function. The scaffolds may be decellularized (such as electrospun fibers), or cells may be seeded into synthetic or natural hydrogels (Caliari and Burdick 2016, Terrell, Jones et al. 2020) (polymer networks that swell with the addition of water) to mimic a physiologically relevant cellular microenvironment capable of ensuring proper cellular morphology, polarity and ultimately survival (19–21). Hydrogels are commonly used due to their biocompatibility, similarities to native in vivo ECM, and wide support for cell adhesion (Caliari and Burdick 2016). However, hydrogels can be difficult to engineer and may be highly variable due to a lack of standardized production protocols (Low, Mummery et al. 2020).

In addition to cellular scaffolds, the materials used to fabricate the chips themselves are extremely important and must be considered carefully. Platform fabrication materials have unique surface chemistries that affect the binding or absorption of cells, compounds, and liquids into the material. One of the most commonly used elastomeric replica materials is polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) due to its excellent biocompatibility, elasticity, optical transparency, and amenability to rapid prototyping (Duffy, McDonald et al. 1998). Despite its advantages, PDMS is able to absorb small hydrophobic molecules (drugs), which can affect the concentration of drug able to reach the tissue. Some research groups have provided data indicating that PDMS devices can be used to quantitatively predict drug pharmacokinetics, and that the drug absorption can be quantified and considered in experiments (Shirure and George 2017, Herland, Maoz et al. 2020). Additionally, researchers have developed novel chemical methods to improve PDMS qualities, such as development of coatings to reduce the surface permeability (van Meer, de Vries et al. 2017). However, some developers and suppliers are replacing PDMS with alternative chip fabrication materials including thermoplastics such as poly(methyl methacrylate) and elastomers such as tetrafluoroethylene-propylene (FEPM) (Bale, Manoppo et al. 2019, Sano, Mori et al. 2019). The material used is often a trade-off between the affordability, availability, and the requirements of the platform (Low, Mummery et al. 2020).

Platform Integration.

Individual ‘organs’ (MPS platforms) can be linked to assess human systemic responses to a drug, compound, and/or associated metabolite. Linked organ system integration provides new ways to profile the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics (PK/PD) of a drug, as well as allowing modeling of cytokine, immune, and hormone responses to compound exposure. The easiest way to integrate individuals MPS systems is through functional coupling, i.e., the transfer of effluent from one MPS module to the next sequentially (Vernetti, Gough et al. 2017). Functional coupling is advantageous due to technical flexibility and ease of platform integration; however, this approach does not mimic native physiological flow between organ systems (Ronaldson-Bouchard and Vunjak-Novakovic 2018). To circumvent this issue, physical linkage can be employed instead, whereby the media stream outflow from one organ module is directly coupled into the inflow of the next through tubing or a connecting channel (Vernetti, Gough et al. 2017). The physical linkage approach requires careful attention to maintenance of sterility during coupling, use of a common medium or blood mimetic and consideration of organ scaling e.g., the relative sizes or functionality of the tissues being connected. Although a blood mimetic has yet to be commercialized, some researchers have addressed the common media requirement through combining tissue/organ-specific media within integrated platforms. For example, researchers at Columbia University developed an integrated two-tissue MPS platform, containing bone cancer tumor and heart muscle, whereby the separated but integrated tissues were perfused with a combined culture media (1:1 mixture of bone tumor and cardiac media) (Chramiec, Teles et al. 2020). The platform has been used to study anti-tumor efficacy and cardiac safety and provides evidence that combination of tissue-specific medias may help circumvent the need for a common blood surrogate in physically linked platforms. In addition to these issues, organ scaling continues to be a hurdle for developers of multi-organ systems, with some investigators proposing that MPSs should be based on relative human organ sizes (respective mass) (Wikswo, Curtis et al. 2013) , while others have proposed the use of functional scaling based on metabolic or blood flow rates (Wikswo, Curtis et al. 2013).

The platform developed by Columbia researchers described above, is modular, allowing serial connections that are optimized for proper tissue scaling (Chramiec, Teles et al. 2020). Modular MPS designs will help facilitate the development of more physiologically relevant in vitro models.

Currently, a number of researchers are using functional coupling approaches. Recently, researchers at Harvard developed a fluidically-coupled human multi-organ-chip first-pass drug ADME model using computationally scaled data (Herland, Maoz et al. 2020). The chips in this model are linked through robotic sequential liquid transfers of a blood mimetic through endothelium-lined channels (Novak, Ingram et al. 2020) and were able to accurately predict PK results for both nicotine and cisplatin (Herland, Maoz et al. 2020). Although there has clearly been major progress in MPS coupling, there remain many challenges, such as how to inhibit and control for air bubble formation, how to maintain sterility during physical linkage of platforms cultured separately, how to prevent leakage of fluid during MPS integration and how to control flow rate and oxygenation levels among differing organ systems (Low, Sutherland et al. 2020).

MPS Developers have also been tasked with ways to miniaturize MPS systems, as large systems with great quantities of pumps, valves and tubing are difficult to ship and often require highly trained personnel to set up. The NIH Tissue Chips in Space program is helping address this challenge by funding the development of robust automated MPS platforms with small laboratory benchtop footprints (Yeung, Koenig et al. 2020). Miniaturization of the chip’s supporting instrumentation combined with more turn-key (user-friendly) MPS platforms is expected to help catalyze the adoption of MPS technology with the reduced need for highly skilled users (Yeung, Koenig et al. 2020). Additionally, more automated, miniaturized MPS platforms help increase throughput and content of platforms, which has potential advantages for early stages of drug development.

In addition to developers, the MPS supplier industry also faces commercial challenges. The business case of each supplier differs depending on which stage of the drug development process is being targeted and therefore what ‘solution’ or ‘niche’ the supplier can offer (Marx, Akabane et al. 2020). Clearly, the perceived solution must line up with the CoU required by regulators and the pharmaceutical industry. Ultimately, there will be differing needs from the customer regarding the need for flexibility, physiological relevance, reliability and robustness, and throughput (low, medium, or high) of each system (Marx, Akabane et al. 2020). For example, simplistic and comparatively-cheaper tissue constructs utilized in high-throughput plate-based systems may be useful in the preclinical target identification, lead selection or lead optimization phases of drug development(Low, Mummery et al. 2020), whereas medium throughput platforms modeling more complex tissue-tissue interactions may be useful in efficacy and toxicity studies within the preclinical phase (Low, Mummery et al. 2020). MPS system developers need to weigh the investment to validate their MPS technology against the market size that has been defined and may need to limit MPS platform development(s) to that which is likely to result in a viable business proposition (Marx, Akabane et al. 2020). Early engagement with biotechnology industry members and end-users is critical to assess open fields of application so as to avoid development of technology when there is no specific area of need (no identified gap) (Marx, Akabane et al. 2020).

2). Pharmaceutical and Industrial Hurdles

The pharmaceutical industry is increasingly focusing on developing and validating physiologically and disease-relevant human cellular models, such as MPS, that may be implemented in the early discovery stage of drug development (Ekert, Deakyne et al. 2020). In fact, a recent survey of 15 pharmaceutical companies forecast that MPS could ultimately save companies 10 – 26% in R&D costs, particularly during the lead optimization process (Franzen, van Harten et al. 2019). The ultimate goal is to identify risks early and focus on molecules and drug targets less likely to fail due to lack of efficacy or safety. Additionally, there is a growing trend in pharma to shift from development of small molecules to macromolecules (Urquhart 2020). These are larger proteins, peptides, nucleic acids, or cell-based therapies that are human target-specific; are derived or manufactured from a living source; and work by targeting specific chemicals or cells involved in the body’s immune system response (e.g., CAR-T and CRISPR/CA-9 genome editing techniques. Biologics differ from small molecules from a safety perspective, as they have the ability to be immunogenic, and thus present risk to patients who may experience moderate to severe immune reactions (Peterson, Mahalingaiah et al. 2020) (Kloks, Berger et al. 2015). Ultimately, these larger, biologically-complex molecules will require human-specific models, ideally placing tissue chips as tools for evaluation of these biologics.

Traditionally, the lead discovery and optimization phases of drug discovery are lengthy and costly, and often focus on poorly validated targets in overly simplistic cellular models with little translational relevance to actual human disease(s). Due to the major time and monetary commitment required to develop a drug, there are limited incentives for the pharmaceutical industry to implement new or experimental models that may not provide obvious value (Marx, Akabane et al. 2020). Therefore, qualification of MPS models, just like any other complex in vitro model, is critical to ensure end-user confidence in the data generated from the model (Ekert, Deakyne et al. 2020). Once models are qualified their translatability can be benchmarked against various ‘omics’ analyses (transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic) (Ekert, Deakyne et al. 2020).

It is unlikely that a single model will be able to recapitulate all disease aspects, but qualification of models will help clarify their ability to describe specific aspects of biology (Ekert, Deakyne et al. 2020) (Ewart, Fabre et al. 2017).

An illustrative example is that GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) has recently begun qualifying specific EpiIntestinal models that may be of use in the preclinical safety phase (Ekert, Deakyne et al. 2020). GSK has compiled a checklist of requirements, which include investigation of specific biological questions as well as defining key endpoint assay parameters (Ekert, Deakyne et al. 2020). They have generated tissue- and organ-specific qualification and characterization checklists to ensure scientists are able to properly qualify models and that these models can be compared across the company (Ekert, Deakyne et al. 2020). While not all criteria outlined in these checklists will be satisfied in any single model, appropriate criterion need to be selected for model qualification as the complexity of the model can be a limiting factor (Ekert, Deakyne et al. 2020). However, an example of the criteria is such that specific cell types within a model should be evaluated for appropriate morphology/phenotype, molecular architecture, functionality, and survival in the system (Ekert, Deakyne et al. 2020) (Ewart, Fabre et al. 2017). Additionally, gene and protein expression levels should be confirmed for models selected to investigate a specific biochemical pathway’s modulation, or to validate specific biological targets (Ekert, Deakyne et al. 2020). Ultimately, industry recognizes the promise of novel MPS technologies but understands that MPS’s must be extensively characterized and tested to more fully understand their potential limitations, value, and ‘context of use’ (Ekert, Deakyne et al. 2020) (Ewart, Fabre et al. 2017). Members of the International Consortium for Innovation and Quality in Pharmaceutical Development (the IQ Consortium MPS Affiliate) have contributed suggestions to the challenges in adoption of MPS by recently publishing a series of organotypic manuscripts a variety of key tissues of interest for drug safety including the kidney, liver, skin, lung, cardiovascular, blood-brain barrier, and gastrointestinal systems, as well as for ADME applications (Ainslie, Davis et al. 2019, Baudy, Otieno et al. 2020, Fabre, Berridge et al. 2020, Fowler, Chen et al. 2020, Hardwick, Betts et al. 2020, Peters, Choy et al. 2020, Peterson, Mahalingaiah et al. 2020, Phillips, Grandhi et al. 2020). The series of white papers provides insight into which types of data and experimental evidence might help expedite successful technological adoption of MPS within drug development, and in particular safety assessments and drug disposition applications (Fabre, Berridge et al. 2020). They highlight the importance of CoU for MPS in safety applications and explain that initial CoU for MPS safety applications may include compound testing during lead and candidate optimization phases, ADME applications, and toxicity testing in all clinical stages, particularly in Phase 1 clinical trials when adverse events in humans are first reported (Ewart, Fabre et al. 2017, Fabre, Berridge et al. 2020).

Ultimately, the importance of articulating the context of use, will help increase confidence in the technology and ultimately reduce the time it will take to prove the value of each microphysiological model (Ewart, Fabre et al. 2017). Direct proof of concept examples where a concept of use has been demonstrated may help increase adoption of the technology within the pharmaceutical industry (Ewart and Roth 2020). Additionally, extinguishing the competitive mindset in pharma, and increasing the amount of data sharing and additional pre-competitive activities, will help promote technological adoption (Ewart and Roth 2020).

The importance of characterization of organ systems, particularly specific drug disposition target organs, is also outlined in these papers. For example, general guidelines on use of a kidney MPS by the pharmaceutical industry should include proper kidney phenotype, kidney functionality, and xenobiotics response (Phillips, Grandhi et al. 2020). Additionally, to demonstrate the physiological relevance of a kidney MPS model they recommend characterizing the mechanical environment, metabolic and transport function, and kidney-specific biochemical markers (Phillips, Grandhi et al. 2020). Another example of guidelines for any liver MPS model for safety risk assessment applications (e.g. drug-induced liver injury (DILI) should have an assessment of the fidelity of liver MPS models to include measuring biomarkers such as albumin and urea, examine gene expression analyses of key phase I/II enzymes and transporters involved in drug metabolism, and assess cellular morphology, cytokine stability, and hepatobiliary network integrity (Baudy, Otieno et al. 2020). Ultimately, the IQ MPS Affiliate has identified many impediments to MPS adoption besides characterization, including the need for standards development, providing adequate amounts of robust and reproducible data to increase technological confidence, and increasing throughput for selected MPS applications (Ekert, Deakyne et al. 2020, Fabre, Berridge et al. 2020). The IQ MPS affiliate also stress the importance in development of animal MPS models of relevant preclinical species currently used in tox analyses (rat, dog, rhesus), which will help bolster end-user confidence in the fidelity of each platform (Baudy, Otieno et al. 2020).

3). Regulatory Hurdles

Validation and qualification of all novel technologies are critical for acceptance by any regulatory agency. However, there are currently no agreed upon ‘gold standard’ validation metrics for MPS systems or the cells and tissues that reside within them. To help address issues with validation, NCATS (NIH) funded independent Tissue Chip Testing Centers and tasked them with onboarding a number of MPS platforms to validate, monitor assay reproducibility, and investigate research parameters agreed upon by the stakeholder community (Low, Sutherland et al. 2020). These Tissue Chip Testing Centers, similar to the entire NIH Tissue Chip Program, have collaborated with the US FDA from the initiative’s inception. Indeed, involvement of regulatory experts from the very beginning is critical for advancing dissemination of any drug development tool. The Testing Centers have also received input from the IQ Consortium in order to validate assays and outcomes from MPS platforms under investigation (Low and Tagle 2017, Low and Tagle 2017, Sakolish, Weber et al. 2018, Sakolish, Chen et al. 2020). The data obtained from the developers and the Testing Centers is deposited into a publicly accessible Microphysiological Systems Database, where users can access assay data and are able to compare on-chip data with both pre-clinical and clinical data sets (Gough, Vernetti et al. 2016, Schurdak, Vernetti et al. 2020). Ultimately, databases such as this provide additional data to help inform regulatory bodies on the technology. It has recently been suggested that suppliers of MPS technologies, such as contract research organizations (CROs), test pharmaceutical compounds on chip to provide evidence (and therefore additional independent validation) that the chip devices produce relevant data (Marx, Akabane et al. 2020).

However, in the US, caution remains amongst those considering Investigational New Drug (IND) applications to the FDA that there may be approvals delays for data packages containing MPS data. The concept of a ‘safe harbor’ for data submission has been under discussion amongst the community, although regulators have noted that IND-submission applicants have submitted very little to no MPS assay data so far (Marx, Akabane et al. 2020). This is not unexpected given that mature MPS-based assays have existed for less than a decade. Currently, MPS are only being used by a few early adopters, while pharmaceutical companies are currently considered mid to later-term followers of the technology (Marx, Akabane et al. 2020). Of note, the FDA has been proactive in understanding MPS technology through signed collaborative agreements with various MPS companies to assess their utility in house, which signals their recognition of the potential of this technology. In addition to the FDA’s collaborations with MPS companies, they recently announced a new pilot program, ‘Innovative Science and Technology Approaches for New Drugs (ISTAND)’, with the goal of expanding the types of Drug Development Tools (DDTs) currently out of scope for current qualification but that may prove ultimately beneficial for drug development. Organs-on-chips are cited as examples of submissions to be considered for ISTAND qualification as a DDT for assessing regulatory safety (Heringa, Park et al. 2020) or efficacy of drugs. Additionally, some of the outcomes from the recent t4 workshop which included regulatory representation was the consensus that increased open communication between regulators, developers, end-users, academic scientists, and MPS suppliers is crucial to advance mainstream MPS adoption (Marx, Akabane et al. 2020). The workshop report also suggested that regulators produce a position paper on regulatory acceptance aspects to guide sponsors on how to include MPS data in approvals packages, based on case study examples (Marx, Akabane et al. 2020). Regulators were also called on to establish annual meetings convening global regulatory agencies in the food, drug, and biologics space to help track and analyze MPS-based data at a regulatory level (Marx, Akabane et al. 2020).

Conclusion

Future Perspectives and Conclusion

Organs-on-chips have clear potential in improving the drug development process, particularly within preclinical safety assessment and ADME applications (Ewart, Dehne et al. 2018, Fabre, Berridge et al. 2020, Fowler, Chen et al. 2020, Heringa, Park et al. 2020, Marx, Akabane et al. 2020). There now exist multiple stakeholder groups that include MPS developers and suppliers pharmaceutical and industrial representatives, and regulatory experts - all interested in advancement and adoption of MPS technology (Marx, Akabane et al. 2020). One way to increase stakeholder networking opportunities - and help bridge the ‘Valley of Death’ of this new technology - is the founding of a comprehensive international MPS conference representing global stakeholder activities. This would provide a way for current stakeholders to communicate as well as provide opportunities for involving new stakeholder groups such as patient-advocacy groups. It would also help push MPS development of recognized international standards for MPS platforms and establish training programs and workshops for young researchers in the MPS field (Marx, Akabane et al. 2020). In recognition of the current gap, the NIH recently issued a funding opportunity announcement (NOT-TR-21–005) to meet this need. It is the goal that such a global MPS conference could be the ‘go-to’ meeting for international MPS stakeholders and help progress towards the goal of overcoming the challenges detailed in this paper, building confidence and trust in this exciting technology along the way.

Ultimately, confidence in MPS technology will only come from increased standardization - of cells, platform fabrication, and platform integration to name a few. Increased standardization efforts will lead to accumulation of sufficient providing evidence that the platforms are reliable, robust, and reproducible. MPS technology must be fit for purpose and utilized for specific context(s) of use. In the foreseeable future, MPS platforms could be qualified as drug development tools (DDT) by the US FDA and other global regulatory agencies. Once qualified as a DDT, MPS platforms will be subject to scale-up and manufacturing, leading to reduced acquisition and operational costs. These changes should help push adoption by both pharmaceutical representatives, as well as regulatory agencies.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

This work was funded by the Cures Acceleration Network, through the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

Footnotes

Statements

Conflict of Interest Statement

“The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.”

References

- (2016). BEST (Biomarkers, EndpointS, and other Tools) Resource Silver Spring (MD). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn SI, Sei YJ, Park HJ, Kim J, Ryu Y, Choi JJ, Sung HJ, MacDonald TJ, Levey AI and Kim Y (2020). “Microengineered human blood-brain barrier platform for understanding nanoparticle transport mechanisms.” Nat Commun 11(1): 175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainslie GR, Davis M, Ewart L, Lieberman LA, Rowlands DJ, Thorley AJ, Yoder G and Ryan AM (2019). “Microphysiological lung models to evaluate the safety of new pharmaceutical modalities: a biopharmaceutical perspective.” Lab Chip 19(19): 3152–3161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alex A, Harris J and Smith DA (2016). “Attrition in the Pharmaceutical Industry Reasons, Implications, and Pathways Forward Introduction.” Attrition in the Pharmaceutical Industry: Reasons, Implications, and Pathways Forward: 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Apati A, Varga N, Berecz T, Erdei Z, Homolya L and Sarkadi B (2019). “Application of human pluripotent stem cells and pluripotent stem cell-derived cellular models for assessing drug toxicity.” Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 15(1): 61–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrowsmith J (2011). “Trial watch: Phase II failures: 2008–2010.” Nat Rev Drug Discov 10(5): 328–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrowsmith J (2011). “Trial watch: phase III and submission failures: 2007–2010.” Nat Rev Drug Discov 10(2): 87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrowsmith J and Miller P (2013). “Trial watch: phase II and phase III attrition rates 2011–2012.” Nat Rev Drug Discov 12(8): 569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atchison L, Zhang H, Cao K and Truskey GA (2017). “A Tissue Engineered Blood Vessel Model of Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome Using Human iPSC-derived Smooth Muscle Cells.” Sci Rep 7(1): 8168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bale SS, Manoppo A, Thompson R, Markoski A, Coppeta J, Cain B, Haroutunian N, Newlin V, Spencer A, Azizgolshani H, Lu M, Gosset J, Keegan P and Charest JL (2019). “A thermoplastic microfluidic microphysiological system to recapitulate hepatic function and multicellular interactions.” Biotechnol Bioeng 116(12): 3409–3420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrile R, van der Meer AD, Park H, Fraser JP, Simic D, Teng F, Conegliano D, Nguyen J, Jain A, Zhou M, Karalis K, Ingber DE, Hamilton GA and Otieno MA (2018). “Organ-on-Chip Recapitulates Thrombosis Induced by an anti-CD154 Monoclonal Antibody: Translational Potential of Advanced Microengineered Systems.” Clin Pharmacol Ther 104(6): 1240–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudy AR, Otieno MA, Hewitt P, Gan J, Roth A, Keller D, Sura R, Van Vleet TR and Proctor WR (2020). “Liver microphysiological systems development guidelines for safety risk assessment in the pharmaceutical industry.” Lab Chip 20(2): 215–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenrath SH, Lee BY, Low L, Prithviraj R and Tagle D (2020). “Tackling rare diseases: Clinical trials on chips.” Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 245(13): 1155–1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JA, Faley SL, Shi Y, Hillgren KM, Sawada GA, Baker TK, Wikswo JP and Lippmann ES (2020). “Advances in blood-brain barrier modeling in microphysiological systems highlight critical differences in opioid transport due to cortisol exposure.” Fluids Barriers CNS 17(1): 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caliari SR and Burdick JA (2016). “A practical guide to hydrogels for cell culture.” Nat Methods 13(5): 405–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang SY, Weber EJ, Sidorenko VS, Chapron A, Yeung CK, Gao C, Mao Q, Shen D, Wang J, Rosenquist TA, Dickman KG, Neumann T, Grollman AP, Kelly EJ, Himmelfarb J and Eaton DL (2017). “Human liver-kidney model elucidates the mechanisms of aristolochic acid nephrotoxicity.” JCI Insight 2(22). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapron A, Chapron BD, Hailey DW, Chang SY, Imaoka T, Thummel KE, Kelly E, Himmelfarb J, Shen D and Yeung CK (2020). “An Improved Vascularized, Dual-Channel Microphysiological System Facilitates Modeling of Proximal Tubular Solute Secretion.” ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci 3(3): 496–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chramiec A, Teles D, Yeager K, Marturano-Kruik A, Pak J, Chen T, Hao L, Wang M, Lock R, Tavakol DN, Lee MB, Kim J, Ronaldson-Bouchard K and Vunjak-Novakovic G (2020). “Integrated human organ-on-a-chip model for predictive studies of anti-tumor drug efficacy and cardiac safety.” Lab Chip. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curzer HJ, Perry G, Wallace MC and Perry D (2016). “The Three Rs of Animal Research: What they Mean for the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and Why.” Sci Eng Ethics 22(2): 549–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis BN, Yen R, Prasad V and Truskey GA (2019). “Oxygen consumption in human, tissue-engineered myobundles during basal and electrical stimulation conditions.” APL Bioeng 3(2): 026103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMasi JA, Grabowski HG and Hansen RW (2016). “Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: New estimates of R&D costs.” J Health Econ 47: 20–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy DC, McDonald JC, Schueller OJ and Whitesides GM (1998). “Rapid Prototyping of Microfluidic Systems in Poly(dimethylsiloxane).” Anal Chem 70(23): 4974–4984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edington CD, Chen WLK, Geishecker E, Kassis T, Soenksen LR, Bhushan BM, Freake D, Kirschner J, Maass C, Tsamandouras N, Valdez J, Cook CD, Parent T, Snyder S, Yu J, Suter E, Shockley M, Velazquez J, Velazquez JJ, Stockdale L, Papps JP, Lee I, Vann N, Gamboa M, LaBarge ME, Zhong Z, Wang X, Boyer LA, Lauffenburger DA, Carrier RL, Communal C, Tannenbaum SR, Stokes CL, Hughes DJ, Rohatgi G, Trumper DL, Cirit M and Griffith LG (2018). “Interconnected Microphysiological Systems for Quantitative Biology and Pharmacology Studies.” Sci Rep 8(1): 4530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekert JE, Deakyne J, Pribul-Allen P, Terry R, Schofield C, Jeong CG, Storey J, Mohamet L, Francis J, Naidoo A, Amador A, Klein JL and Rowan W (2020). “Recommended Guidelines for Developing, Qualifying, and Implementing Complex In Vitro Models (CIVMs) for Drug Discovery.” SLAS Discov: 2472555220923332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewart L, Dehne EM, Fabre K, Gibbs S, Hickman J, Hornberg E, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Jang KJ, Jones DR, Lauschke VM, Marx U, Mettetal JT, Pointon A, Williams D, Zimmermann WH and Newham P (2018). “Application of Microphysiological Systems to Enhance Safety Assessment in Drug Discovery.” Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 58: 65–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewart L, Fabre K, Chakilam A, Dragan Y, Duignan DB, Eswaraka J, Gan J, Guzzie-Peck P, Otieno M, Jeong CG, Keller DA, de Morais SM, Phillips JA, Proctor W, Sura R, Van Vleet T, Watson D, Will Y, Tagle D and Berridge B (2017). “Navigating tissue chips from development to dissemination: A pharmaceutical industry perspective.” Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 242(16): 1579–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewart L and Roth A (2020). “Opportunities and challenges with microphysiological systems: a pharma end-user perspective.” Nat Rev Drug Discov. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabre K, Berridge B, Proctor WR, Ralston S, Will Y, Baran SW, Yoder G and Van Vleet TR (2020). “Introduction to a manuscript series on the characterization and use of microphysiological systems (MPS) in pharmaceutical safety and ADME applications.” Lab Chip 20(6): 1049–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabre KM, Delsing L, Hicks R, Colclough N, Crowther DC and Ewart L (2019). “Utilizing microphysiological systems and induced pluripotent stem cells for disease modeling: a case study for blood brain barrier research in a pharmaceutical setting.” Adv Drug Deliv Rev 140: 129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler S, Chen WLK, Duignan DB, Gupta A, Hariparsad N, Kenny JR, Lai WG, Liras J, Phillips JA and Gan J (2020). “Microphysiological systems for ADME-related applications: current status and recommendations for system development and characterization.” Lab Chip 20(3): 446–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzen N, van Harten WH, Retel VP, Loskill P, van J den Eijnden-van Raaij and I. J. M (2019). “Impact of organ-on-a-chip technology on pharmaceutical R&D costs.” Drug Discov Today 24(9): 1720–1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friese MA, Montalban X, Willcox N, Bell JI, Martin R and Fugger L (2006). “The value of animal models for drug development in multiple sclerosis.” Brain 129(Pt 8): 1940–1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough A, Vernetti L, Bergenthal L, Shun TY and Taylor DL (2016). “The Microphysiology Systems Database for Analyzing and Modeling Compound Interactions with Human and Animal Organ Models.” Appl In Vitro Toxicol 2(2): 103–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribkoff VK and Kaczmarek LK (2017). “The need for new approaches in CNS drug discovery: Why drugs have failed, and what can be done to improve outcomes.” Neuropharmacology 120: 11–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardwick RN, Betts CJ, Whritenour J, Sura R, Thamsen M, Kaufman EH and Fabre K (2020). “Drug-induced skin toxicity: gaps in preclinical testing cascade as opportunities for complex in vitro models and assays.” Lab Chip 20(2): 199–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins KG, Casolaro C, Brown JA, Edwards DA and Wikswo JP (2020). “The Microbiome and the Gut-Liver-Brain Axis for Central Nervous System Clinical Pharmacology: Challenges in Specifying and Integrating In Vitro and In Silico Models.” Clin Pharmacol Ther. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heringa MB, Park M, Kienhuis AS and Vandebriel RJ (2020). “The value of organs-on-chip for regulatory safety assessment.” ALTEX 37(2): 208–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herland A, Maoz BM, Das D, Somayaji MR, Prantil-Baun R, Novak R, Cronce M, Huffstater T, Jeanty SSF, Ingram M, Chalkiadaki A, Benson Chou D, Marquez S, Delahanty A, Jalili-Firoozinezhad S, Milton Y, Sontheimer-Phelps A, Swenor B, Levy O, Parker KK, Przekwas A and Ingber DE (2020). “Quantitative prediction of human pharmacokinetic responses to drugs via fluidically coupled vascularized organ chips.” Nat Biomed Eng 4(4): 421–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herron LA, Hansen CS and Abaci HE (2019). “Engineering tissue-specific blood vessels.” Bioeng Transl Med 4(3): e10139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingber DE (2020). “Is it Time for Reviewer 3 to Request Human Organ Chip Experiments Instead of Animal Validation Studies?” Adv Sci (Weinh) 7(22): 2002030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang KJ, Mehr AP, Hamilton GA, McPartlin LA, Chung S, Suh KY and Ingber DE (2013). “Human kidney proximal tubule-on-a-chip for drug transport and nephrotoxicity assessment.” Integr Biol (Camb) 5(9): 1119–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang KJ, Otieno MA, Ronxhi J, Lim HK, Ewart L, Kodella KR, Petropolis DB, Kulkarni G, Rubins JE, Conegliano D, Nawroth J, Simic D, Lam W, Singer M, Barale E, Singh B, Sonee M, Streeter AJ, Manthey C, Jones B, Srivastava A, Andersson LC, Williams D, Park H, Barrile R, Sliz J, Herland A, Haney S, Karalis K, Ingber DE and Hamilton GA (2019). “Reproducing human and cross-species drug toxicities using a Liver-Chip.” Sci Transl Med 11(517). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardim DL, Groves ES, Breitfeld PP and Kurzrock R (2017). “Factors associated with failure of oncology drugs in late-stage clinical development: A systematic review.” Cancer Treat Rev 52: 12–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Li H, Collins JJ and Ingber DE (2016). “Contributions of microbiome and mechanical deformation to intestinal bacterial overgrowth and inflammation in a human gut-on-a-chip.” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113(1): E7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Doi A, Wen B, Ng K, Zhao R, Cahan P, Kim J, Aryee MJ, Ji H, Ehrlich LI, Yabuuchi A, Takeuchi A, Cunniff KC, Hongguang H, McKinney-Freeman S, Naveiras O, Yoon TJ, Irizarry RA, Jung N, Seita J, Hanna J, Murakami P, Jaenisch R, Weissleder R, Orkin SH, Weissman IL, Feinberg AP and Daley GQ (2010). “Epigenetic memory in induced pluripotent stem cells.” Nature 467(7313): 285–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Jeon HM, Choi KC and Sung GY (2020). “Testing the Effectiveness of Curcuma longa Leaf Extract on a Skin Equivalent Using a Pumpless Skin-on-a-Chip Model.” Int J Mol Sci 21(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloks C, Berger C, Cortez P, Dean Y, Heinrich J, Bjerring Jensen L, Koppenburg V, Kostense S, Kramer D, Spindeldreher S and Kirby H (2015). “A fit-for-purpose strategy for the risk-based immunogenicity testing of biotherapeutics: a European industry perspective.” J Immunol Methods 417: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak BS, Jin SP, Kim SJ, Kim EJ, Chung JH and Sung JH (2020). “Microfluidic skin chip with vasculature for recapitulating the immune response of the skin tissue.” Biotechnol Bioeng 117(6): 1853–1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CS and Leong KW (2020). “Advances in microphysiological blood-brain barrier (BBB) models towards drug delivery.” Curr Opin Biotechnol 66: 78–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, George SM, Vernetti L, Gough AH and Taylor DL (2018). “A glass-based, continuously zonated and vascularized human liver acinus microphysiological system (vLAMPS) designed for experimental modeling of diseases and ADME/TOX.” Lab Chip 18(17): 2614–2631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind JU, Busbee TA, Valentine AD, Pasqualini FS, Yuan H, Yadid M, Park SJ, Kotikian A, Nesmith AP, Campbell PH, Vlassak JJ, Lewis JA and Parker KK (2017). “Instrumented cardiac microphysiological devices via multimaterial three-dimensional printing.” Nat Mater 16(3): 303–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind JU, Yadid M, Perkins I, O’Connor BB, Eweje F, Chantre CO, Hemphill MA, Yuan H, Campbell PH, Vlassak JJ and Parker KK (2017). “Cardiac microphysiological devices with flexible thin-film sensors for higher-throughput drug screening.” Lab Chip 17(21): 3692–3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Koo Y, Akwitti C, Russell T, Gay E, Laskowitz DT and Yun Y (2019). “Three-dimensional (3D) brain microphysiological system for organophosphates and neurochemical agent toxicity screening.” PLoS One 14(11): e0224657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Sakolish C, Chen Z, Phan DTT, Bender RHF, Hughes CCW and Rusyn I (2020). “Human in vitro vascularized micro-organ and micro-tumor models are reproducible organ-on-a-chip platforms for studies of anticancer drugs.” Toxicology 445: 152601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low LA, Mummery C, Berridge BR, Austin CP and Tagle DA (2020). “Organs-on-chips: into the next decade.” Nat Rev Drug Discov. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low LA, Sutherland M, Lumelsky N, Selimovic S, Lundberg MS and Tagle DA (2020). “Organs-on-a-Chip.” Adv Exp Med Biol 1230: 27–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low LA and Tagle DA (2016). “Tissue Chips to aid drug development and modeling for rare diseases.” Expert Opin Orphan Drugs 4(11): 1113–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low LA and Tagle DA (2017). “Organs-on-chips: Progress, challenges, and future directions.” Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 242(16): 1573–1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low LA and Tagle DA (2017). “Tissue chips - innovative tools for drug development and disease modeling.” Lab Chip 17(18): 3026–3036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maass C, Sorensen NB, Himmelfarb J, Kelly EJ, Stokes CL and Cirit M (2019). “Translational Assessment of Drug-Induced Proximal Tubule Injury Using a Kidney Microphysiological System.” CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol 8(5): 316–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx U, Akabane T, Andersson TB, Baker E, Beilmann M, Beken S, Brendler-Schwaab S, Cirit M, David R, Dehne EM, Durieux I, Ewart L, Fitzpatrick SC, Frey O, Fuchs F, Griffith LG, Hamilton GA, Hartung T, Hoeng J, Hogberg H, Hughes DJ, Ingber DE, Iskandar A, Kanamori T, Kojima H, Kuehnl J, Leist M, Li B, Loskill P, Mendrick DL, Neumann T, Pallocca G, Rusyn I, Smirnova L, Steger-Hartmann T, Tagle DA, Tonevitsky A, Tsyb S, Trapecar M, Van de Water B, Van J Raaij den Eijnden-van, Vulto P, Watanabe K, Wolf A, Zhou X and Roth A (2020). “Biology-inspired microphysiological systems to advance patient benefit and animal welfare in drug development.” ALTEX 37(3): 364–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas CR, Chen J, Tang Y, Southwell DG, Chalmers N, Vogt D, Arnold CM, Chen YJ, Stanley EG, Elefanty AG, Sasai Y, Alvarez-Buylla A, Rubenstein JL and Kriegstein AR (2013). “Functional maturation of hPSC-derived forebrain interneurons requires an extended timeline and mimics human neural development.” Cell Stem Cell 12(5): 573–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizawa M, Chonabayashi K, Nomura M, Tanaka A, Nakamura M, Inagaki A, Nishikawa M, Takei I, Oishi A, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Yokota H, Koyanagi-Aoi M, Okita K, Watanabe A, Takaori-Kondo A, Yamanaka S and Yoshida Y (2016). “Epigenetic Variation between Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Lines Is an Indicator of Differentiation Capacity.” Cell Stem Cell 19(3): 341–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak R, Ingram M, Marquez S, Das D, Delahanty A, Herland A, Maoz BM, Jeanty SSF, Somayaji MR, Burt M, Calamari E, Chalkiadaki A, Cho A, Choe Y, Chou DB, Cronce M, Dauth S, Divic T, Fernandez-Alcon J, Ferrante T, Ferrier J, FitzGerald EA, Fleming R, Jalili-Firoozinezhad S, Grevesse T, Goss JA, Hamkins-Indik T, Henry O, Hinojosa C, Huffstater T, Jang KJ, Kujala V, Leng L, Mannix R, Milton Y, Nawroth J, Nestor BA, Ng CF, O’Connor B, Park TE, Sanchez H, Sliz J, Sontheimer-Phelps A, Swenor B, Thompson G 2nd, Touloumes GJ, Tranchemontagne Z, Wen N, Yadid M, Bahinski A, Hamilton GA, Levner D, Levy O, Przekwas A, Prantil-Baun R, Parker KK and Ingber DE (2020). “Robotic fluidic coupling and interrogation of multiple vascularized organ chips.” Nat Biomed Eng 4(4): 407–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osaki T, Uzel SGM and Kamm RD (2018). “Microphysiological 3D model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) from human iPS-derived muscle cells and optogenetic motor neurons.” Sci Adv 4(10): eaat5847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paek J, Park SE, Lu Q, Park KT, Cho M, Oh JM, Kwon KW, Yi YS, Song JW, Edelstein HI, Ishibashi J, Yang W, Myerson JW, Kiseleva RY, Aprelev P, Hood ED, Stambolian D, Seale P, Muzykantov VR and Huh D (2019). “Microphysiological Engineering of Self-Assembled and Perfusable Microvascular Beds for the Production of Vascularized Three-Dimensional Human Microtissues.” ACS Nano 13(7): 7627–7643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamies D, Barreras P, Block K, Makri G, Kumar A, Wiersma D, Smirnova L, Zang C, Bressler J, Christian KM, Harris G, Ming GL, Berlinicke CJ, Kyro K, Song H, Pardo CA, Hartung T and Hogberg HT (2017). “A human brain microphysiological system derived from induced pluripotent stem cells to study neurological diseases and toxicity.” ALTEX 34(3): 362–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parasrampuria DA, Benet LZ and Sharma A (2018). “Why Drugs Fail in Late Stages of Development: Case Study Analyses from the Last Decade and Recommendations.” AAPS J 20(3): 46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters MF, Choy AL, Pin C, Leishman DJ, Moisan A, Ewart L, Guzzie-Peck PJ, Sura R, Keller DA, Scott CW and Kolaja KL (2020). “Developing in vitro assays to transform gastrointestinal safety assessment: potential for microphysiological systems.” Lab Chip 20(7): 1177–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson NC, Mahalingaiah PK, Fullerton A and Di Piazza M (2020). “Application of microphysiological systems in biopharmaceutical research and development.” Lab Chip 20(4): 697–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JA, Grandhi TSP, Davis M, Gautier JC, Hariparsad N, Keller D, Sura R and Van Vleet TR (2020). “A pharmaceutical industry perspective on microphysiological kidney systems for evaluation of safety for new therapies.” Lab Chip 20(3): 468–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajamohan D, Matsa E, Kalra S, Crutchley J, Patel A, George V and Denning C (2013). “Current status of drug screening and disease modelling in human pluripotent stem cells.” Bioessays 35(3): 281–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribas J, Zhang YS, Pitrez PR, Leijten J, Miscuglio M, Rouwkema J, Dokmeci MR, Nissan X, Ferreira L and Khademhosseini A (2017). “Biomechanical Strain Exacerbates Inflammation on a Progeria-on-a-Chip Model.” Small 13(15). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro AJS, Yang X, Patel V, Madabushi R and Strauss DG (2019). “Liver Microphysiological Systems for Predicting and Evaluating Drug Effects.” Clin Pharmacol Ther 106(1): 139–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Lopez M, Li Z, Rhee C, Maruyama M, Pajarinen J, O’Donnell B, Lin TH, Lo CW, Hanlon J, Dubowitz R, Yao Z, Bunnell BA, Lin H, Tuan RS and Goodman SB (2020). “Macrophage Effects on Mesenchymal Stem Cell Osteogenesis in a Three-Dimensional In Vitro Bone Model.” Tissue Eng Part A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronaldson-Bouchard K and Vunjak-Novakovic G (2018). “Organs-on-a-Chip: A Fast Track for Engineered Human Tissues in Drug Development.” Cell Stem Cell 22(3): 310–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudmann DG (2019). “The Emergence of Microphysiological Systems (Organs-on-chips) as Paradigm-changing Tools for Toxicologic Pathology.” Toxicol Pathol 47(1): 4–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakolish C, Chen Z, Dalaijamts C, Mitra K, Liu Y, Fulton T, Wade TL, Kelly EJ, Rusyn I and Chiu WA (2020). “Predicting tubular reabsorption with a human kidney proximal tubule tissue-on-a-chip and physiologically-based modeling.” Toxicol In Vitro 63: 104752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakolish C, Weber EJ, Kelly EJ, Himmelfarb J, Mouneimne R, Grimm FA, House JS, Wade T, Han A, Chiu WA and Rusyn I (2018). “Technology Transfer of the Microphysiological Systems: A Case Study of the Human Proximal Tubule Tissue Chip.” Sci Rep 8(1): 14882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano E, Mori C, Matsuoka N, Ozaki Y, Yagi K, Wada A, Tashima K, Yamasaki S, Tanabe K, Yano K and Torisawa YS (2019). “Tetrafluoroethylene-Propylene Elastomer for Fabrication of Microfluidic Organs-on-Chips Resistant to Drug Absorption.” Micromachines (Basel) 10(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schurdak M, Vernetti L, Bergenthal L, Wolter QK, Shun TY, Karcher S, Taylor DL and Gough A (2020). “Applications of the microphysiology systems database for experimental ADME-Tox and disease models.” Lab Chip 20(8): 1472–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirure VS and George SC (2017). “Design considerations to minimize the impact of drug absorption in polymer-based organ-on-a-chip platforms.” Lab Chip 17(4): 681–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontheimer-Phelps A, Chou DB, Tovaglieri A, Ferrante TC, Duckworth T, Fadel C, Frismantas V, Sutherland AD, Jalili-Firoozinezhad S, Kasendra M, Stas E, Weaver JC, Richmond CA, Levy O, Prantil-Baun R, Breault DT and Ingber DE (2020). “Human Colon-on-a-Chip Enables Continuous In Vitro Analysis of Colon Mucus Layer Accumulation and Physiology.” Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 9(3): 507–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein JM, Mummery CL and Bellin M (2020). “Engineered models of the human heart: directions and challenges.” Stem Cell Reports. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagle DA (2019). “The NIH microphysiological systems program: developing in vitro tools for safety and efficacy in drug development.” Curr Opin Pharmacol 48: 146–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Okita K, Nakagawa M and Yamanaka S (2007). “Induction of pluripotent stem cells from fibroblast cultures.” Nat Protoc 2(12): 3081–3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K and Yamanaka S (2007). “Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors.” Cell 131(5): 861–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K and Yamanaka S (2006). “Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors.” Cell 126(4): 663–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H, Abouleila Y, Si L, Ortega-Prieto AM, Mummery CL, Ingber DE and Mashaghi A (2020). “Human Organs-on-Chips for Virology.” Trends Microbiol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrell JA, Jones CG, Kabandana GKM and Chen C (2020). “From cells-on-a-chip to organs-on-a-chip: scaffolding materials for 3D cell culture in microfluidics.” J Mater Chem B 8(31): 6667–6685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truskey GA (2018). “Development and application of human skeletal muscle microphysiological systems.” Lab Chip 18(20): 3061–3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truskey GA (2018). “Human Microphysiological Systems and Organoids as in Vitro Models for Toxicological Studies.” Front Public Health 6: 185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart L (2020). “Top companies and drugs by sales in 2019.” Nat Rev Drug Discov 19(4): 228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg A, Mummery CL, Passier R and van der Meer AD (2019). “Personalised organs-on-chips: functional testing for precision medicine.” Lab Chip 19(2): 198–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Meer BJ, de Vries H, Firth KSA, van Weerd J, Tertoolen LGJ, Karperien HBJ, Jonkheijm P, Denning C, AP IJ and Mummery CL (2017). “Small molecule absorption by PDMS in the context of drug response bioassays.” Biochem Biophys Res Commun 482(2): 323–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhulsel M, Vignes M, Descroix S, Malaquin L, Vignjevic DM and Viovy JL (2014). “A review of microfabrication and hydrogel engineering for micro-organs on chips.” Biomaterials 35(6): 1816–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernetti L, Gough A, Baetz N, Blutt S, Broughman JR, Brown JA, Foulke-Abel J, Hasan N, In J, Kelly E, Kovbasnjuk O, Repper J, Senutovitch N, Stabb J, Yeung C, Zachos NC, Donowitz M, Estes M, Himmelfarb J, Truskey G, Wikswo JP and Taylor DL (2017). “Functional Coupling of Human Microphysiology Systems: Intestine, Liver, Kidney Proximal Tubule, Blood-Brain Barrier and Skeletal Muscle.” Sci Rep 7: 42296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner J, Dahlem AM, Hudson LD, Terry SF, Altman RB, Gilliland CT, DeFeo C and Austin CP (2018). “A dynamic map for learning, communicating, navigating and improving therapeutic development.” Nat Rev Drug Discov 17(2): 150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner JA, Dahlem AM, Hudson LD, Terry SF, Altman RB, Gilliland CT, DeFeo C and Austin CP (2018). “Application of a Dynamic Map for Learning, Communicating, Navigating, and Improving Therapeutic Development.” Clin Transl Sci 11(2): 166–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, McCain ML, Yang L, He A, Pasqualini FS, Agarwal A, Yuan H, Jiang D, Zhang D, Zangi L, Geva J, Roberts AE, Ma Q, Ding J, Chen J, Wang DZ, Li K, Wang J, Wanders RJ, Kulik W, Vaz FM, Laflamme MA, Murry CE, Chien KR, Kelley RI, Church GM, Parker KK and Pu WT (2014). “Modeling the mitochondrial cardiomyopathy of Barth syndrome with induced pluripotent stem cell and heart-on-chip technologies.” Nat Med 20(6): 616–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waring MJ, Arrowsmith J, Leach AR, Leeson PD, Mandrell S, Owen RM, Pairaudeau G, Pennie WD, Pickett SD, Wang J, Wallace O and Weir A (2015). “An analysis of the attrition of drug candidates from four major pharmaceutical companies.” Nat Rev Drug Discov 14(7): 475–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Furukawa T, Sharyo S, Ohashi Y, Yasuda M, Takaoka M and Manabe S (2000). “Effect of troglitazone on the liver of a Gunn rat model of genetic enzyme polymorphism.” J Toxicol Sci 25(5): 423–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikswo JP, Curtis EL, Eagleton ZE, Evans BC, Kole A, Hofmeister LH and Matloff WJ (2013). “Scaling and systems biology for integrating multiple organs-on-a-chip.” Lab Chip 13(18): 3496–3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao S, Coppeta JR, Rogers HB, Isenberg BC, Zhu J, Olalekan SA, McKinnon KE, Dokic D, Rashedi AS, Haisenleder DJ, Malpani SS, Arnold-Murray CA, Chen K, Jiang M, Bai L, Nguyen CT, Zhang J, Laronda MM, Hope TJ, Maniar KP, Pavone ME, Avram MJ, Sefton EC, Getsios S, Burdette JE, Kim JJ, Borenstein JT and Woodruff TK (2017). “A microfluidic culture model of the human reproductive tract and 28-day menstrual cycle.” Nat Commun 8: 14584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung CK, Koenig P, Countryman S, Thummel KE, Himmelfarb J and Kelly EJ (2020). “Tissue Chips in Space-Challenges and Opportunities.” Clin Transl Sci 13(1): 8–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B and Radisic M (2017). “Organ-on-a-chip devices advance to market.” Lab Chip 17(14): 2395–2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Hong S, Yen R, Kondash M, Fernandez CE and Truskey GA (2018). “A system to monitor statin-induced myopathy in individual engineered skeletal muscle myobundles.” Lab Chip 18(18): 2787–2796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]