Abstract

What effects do international crises have on the public legitimacy of International Organizations (IOs)? Deviating from previous research, we argue that such crises make those international organizations more salient that are mandated to solve the respective crisis. This results in two main effects. First, the public legitimacy of those IOs becomes more dependent on citizens’ crisis-induced worries, leading to a more positive view of those IOs. Second, as the higher salience also leads to higher levels of elite communication regarding IOs, elite blaming of the IOs during crises results in direct negative effects on public legitimacy beliefs on IOs. Finally, both the valence and content of the elite discourse additionally moderate the positive effects of crisis-induced worries. Implementing survey experiments on public legitimacy beliefs on the WHO during the COVID-19 crisis with about 4400 respondents in Austria, Germany and Turkey, we find preliminary evidence for the expectations derived from our salience argument. In the conclusion, we discuss the implications of these findings for future research on IO legitimacy and IO legitimation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11558-021-09452-y.

Keywords: IO legitimacy, Public legitimacy, International crisis, Elite cues, Survey experiment, Public opinion

Introduction

Over the last twenty years, the world has repeatedly seen international crises of all kinds, such as economic crises – like the Asian and Latin American crises in the early 2000s or the global financial crisis 2007–2008 –, an increasing number of (military) peace interventions led by international and regional organizations since 2001 (Jetschke & Schlipphak, 2020), crises related to increasing numbers of refugees – especially in Europe starting in 2015 –, and finally, the COVID-19 pandemic starting in late 2019 / early 2020. As an effect, not only have the respective international organizations (IOs) become more aware to elites and masses alike – with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) having played an (in)famous role in the financial crises or the World Health Organization (WHO) becoming more strongly known during the COVID-19 pandemic –, but also has the pressure for these IOs to legitimize themselves seemingly increased. The perceived inability of several of these organizations to pursue their tasks has led to a decreasing level of public legitimacy among elites and masses, understood as the degree of an IO “being believed to have the right to rule” (Keohane, 2011, p. 99). Hence, the main effect of an international crisis on IO public legitimacy seems to be that IOs come under more pressure to legitimize themselves (for IO self-legitimation, see Ecker-Ehrhardt, 2018a, b). But is this the only effect that such crises may have on IO legitimacy?

In this article, we argue that international crises have another important influence on IO legitimacy. In increasing the salience of an IO and making the IO a matter of increased public debate, international crises have two connected effects: First, the increasing salience should make citizens more aware of the respective IO and hence enable them to more easily connect – the worries of – their everyday life with what an IO does, hence making an IO’s public legitimacy among the masses much more resting on linking the IO’s (perceived) mandate in a crisis to citizens’ (perceived) affectedness by that crisis. However, and second, increasing public debates also open windows of opportunities for political elites to blame the IO to gain domestic support. This increasing level of elite blaming may also influence citizens’ attitudes toward the IO (for the concept, see Dellmuth & Tallberg, 2020a; Heinkelmann-Wild & Zangl, 2020), which may further reduce the effectiveness of global responses to crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Fazal, 2020).

In the remainder, after shortly reviewing the literature on IO public legitimacy, we discuss both of these potential effects in detail and develop a causal mechanism that combines both of these arguments. Under the scope condition of an IO becoming more publicly salient within an international crisis and this leading to an increased level of citizens’ awareness of the IO, we expect, first, that citizens’ levels of IO legitimacy beliefs are more positively influenced by their crisis-induced worries (direct effect of individual affectedness). Second, we expect that political elites can use the international crisis to undermine the public legitimacy of an IO (direct effect of elite blaming). Third, the influence of crisis-induced worries on IO legitimacy beliefs is moderated by political elites’ communication about the crisis. While elite blaming of the IO in handling the crisis reduces the impact of crisis-induced worries on increased legitimacy beliefs (moderating blaming effect), elite frames underlining the effectiveness of the IO increase the impact (moderating framing effect).

We test these expectations with a self-administered survey experiment on COVID-19 and the public legitimacy of the WHO in Germany, Austria and Turkey. Our findings demonstrate that in all three country contexts, citizens who perceive COVID-19 as a greater threat to themselves have more favorable attitudes toward the WHO. The results also show that those exposed to negative elite cues on the WHO’s management of the crisis demonstrate much weaker support for the WHO. Finally, as hypothesized, the direct effect of individual affectedness is substantially moderated by both the valence and content of the elite discourse on WHO’s performance.

In the remainder, we will first outline how previous literature on the topic of IO attitudes has seemingly neglected political opportunity structures – in our case: the consequences of global crises – before developing our own three-fold argument and the hypotheses derived out of it (De Vries et al., 2021). After clarifying the role of public salience and citizens’ awareness as scope conditions, subsequently, we present our research design and specifically our experimental setting in more detail before moving on to the discussion of our empirical findings and our robustness checks. Finally, in our conclusion, we discuss these findings and point to the implications for future research, specifically highlighting the need to both include political circumstances and their individually varying affectedness into the research on IO legitimacy.

Literature review

Despite an extensive history of the topic in the International Relations (IR) literature (Franck, 1990; Held, 1995), the legitimacy of IOs has gained traction within the IR debate only recently (Buchanan & Keohane, 2006; Hurd, 2007; Keohane, 2011). Starting with Keohane’s distinction between normative and sociological – or what we call: public – legitimacy (Keohane, 2011) research, especially regarding the latter branch, has systematically increased over the last ten years (see, e.g., Dellmuth & Tallberg, 2015, 2020a, b; Binder & Heupel, 2015; Schmidtke, 2019; Tallberg & Zürn, 2019). The research on the public legitimacy of IOs, understood as citizens’ acceptance of or trust toward international and regional organizations, has been informed by thematically closely related research on public opinion toward the European Union and European integration in general on the one hand, and toward free trade and trade agreements on the other hand. Both research on citizens’ attitudes toward the EU and free trade has followed three quite similar lines of argumentation (Hooghe & Marks, 2005; see also Hobolt & De Vries, 2016).

First, especially older research has highlighted the relevance of utilitarian factors in explaining attitudes toward international cooperation. Citizens favor the EU or free trade if they personally profit (egotropic) or if they perceive their country to profit from European integration or trade cooperation (sociotropic motivation) (Fordham & Kleinberg, 2012; Gabel, 1998; Scheve & Slaughter, 2001).

Second, this utilitarian research has been challenged on theoretical and empirical grounds by a more psychological perspective, highlighting either identity-related factors – such as national pride, ideological and psychological predispositions (Mansfield & Mutz, 2009), threat perceptions (McLaren, 2002), or cosmopolitanism (Ecker-Ehrhardt, 2016) – or the effects of transferring more long-term predispositions – such as general trust in others or trust in domestic actors– onto the international level (Harteveld et al., 2013; Kaltenthaler & Miller, 2014). For international organizations, Dellmuth and Tallberg (2020b) as well as Schlipphak (2015) find that social and political trust crucially shapes citizens’ attitudes toward international organizations such as the UN or regional organizations such as the African Union or UNASUR. In the same vein, Kiratli (2020) has posited that individuals’ perception of national economic conditions is an important determinant of their support for the UN and NATO. Similarly, Johnson (2011) has shown that citizens transfer their attitudes toward more well-known international actors such as the US onto their general feelings toward the organization (see also Genna, 2017; Steiner, 2018).

Third, and finally, research has examined the effects of citizens taking cues from elites when making up their minds about policies and institutions at the international level. Such research has indicated that positive / negative cues communicated by trusted elites make citizens more / less favorable toward the EU (De Vries & Edwards, 2009; Gabel & Scheve, 2007; Steenbergen et al., 2007) or trade agreements (Dür & Schlipphak, 2020). Regarding international organizations, Dellmuth and Tallberg (2020a) have also demonstrated that governmental cues may influence citizens’ attitudes toward the UN.

A common assumption in the extant research on IO legitimacy is that most citizens do not know much about the IOs they are to evaluate and often have limited information about what precisely the IO is or its work (Dellmuth, 2016). While this is plausible as long as IOs are only marginally politicized – that is, citizens perceiving IOs as not particularly important (Wlezien, 2005) – this may change if IOs become suddenly more contested, increasing public salience and – in consequence – citizens’ awareness (see for similar arguments, De Vries et al., 2021; Hobolt & Wratil, 2015; Arceneaux, 2008). However, little to no research on this topic has considered the dimension of global crises which provide such a sudden boost in IO salience and increase elite communication about the IO.

Theoretical argument

In this article, we assume that international crises increase the salience of IOs in public debates and argue that this results in three effects. First, the crisis-related increased salience of IOs in public debates makes citizens more aware of an IO (awareness argument). Second, the greater level of awareness enables citizens to connect more easily their (perceived) affectedness of the crisis to the (perceived) mandate of IOs, making crisis-inspired worries influence the public legitimacy of IOs positively (affectedness argument). Third, domestic elites’ blaming of the IO decreases public legitimacy of IOs (elite blaming argument). Fourth, the effect of individual affectedness is moderated by political elites’ communication regarding the IO’s role in the crisis (interaction argument).

The mechanism behind our first (awareness) argument is straightforward: In times of crisis, IOs with the mandate to combat or support in combatting the crisis become more salient in public debates. As a consequence of the IOs becoming increasingly mentioned and politicized in public debates, citizens become more aware of them and their communicated mandate. While the latter does not need to be fully convergent with the actual mandate of the respective IO, the increased communication about the IO should result in an increased awareness among citizens that the IO exists and that the IO is connected to the crisis.

Our second (affectedness) argument builds on the first one. With citizens becoming increasingly aware of international organizations as actors within a respective crisis – such as the IMF during financial crises, the WTO during trade crises, the UN during crises regarding war and peace, or the WHO during pandemic crises –, citizens become increasingly (cognitively) able to link their own crisis-induced (perceived) affectedness to the (perceived) mandate of an IO.

In essence, we then expect citizens that perceived themselves to be more affected by the crisis compared to others to perceive the IO more positively. The mechanism behind this expectation assumes more crisis-affected citizens to be in need for – and hence, to actively search for – actors seemingly being able to reduce the crisis’ impact on their lives. As a result, these citizens become more favorable toward any actor who can be perceived as being mandated to combat or to support in combatting the crisis – in other words, any actor who can be perceived to decrease the crisis-induced affectedness. We argue that this is the case regardless of whether this actor has already demonstrated that s/he actually is of help but simply because the actor seems to care.1 Stated in a formal way, we empirically expect that:

H1: The more citizens perceive themselves to be affected by a crisis, the more legitimate they perceive an IO being mandated to solve or to support in solving the crisis.

As a baseline assumption, we stated that an IO whose mandate is connected to a certain type of crisis becomes increasingly salient in times of such a crisis actually taking place. Empirically, however, increasing public salience also means that there is more elite discourse and media coverage regarding that IO. This may have two effects, a direct and a moderating effect.

In most of the aforementioned crises so far, we have witnessed domestic governments to focus on solving the crisis on the domestic levels, mostly trying to avoid being intervened in their crisis management by IOs. As a result, they have aimed to increase the shifting of blame to the external or international level, hence challenging the capability of the IOs mandated to solve the crisis (see, e.g., Vasilopolou et al., 2014; Schlipphak & Treib, 2017; Heinkelmann-Wild & Zangl, 2020). We argue that such a challenge of IOs should result in a direct elite blaming effect. A negative statement about an actor – that is, blaming an actor – has been shown repeatedly to decrease citizens’ attitudes toward that actor. This is mostly due because citizens react more strongly to and follow negative cues than positive ones (see for a recent overview Avdagic & Savage, 2019).

H2: In the presence of an elite cue challenging the IO, citizens perceive an IO being mandated to solve the crisis to be less legitimate (direct blaming effect)

What is even more important is that in times of crisis-induced high levels of public salience of an IO, citizens’ linkage of their crisis affectedness to an IO – the core of our second argument – may be moderated by political elites’ blaming but also by elites’ framing of the respective IO.

Starting with the potential effect of elite blaming, the moderating effect might be even more interesting than the direct effect that we outlined before in H2. If political elites actively challenge the IO for not pursuing its mandate in managing the crisis, citizens should still link their affectedness by the crisis to the mandated IO, but the IO should then be perceived as less of a solution to the crisis-induced worries. Hence, the positive effect that we expect in H1 to be the result of that linkage should somewhat become less effective or even diametral in influencing citizens’ attitudes toward that IO if elites are blaming the IO in regard to the (enduring) crisis.

H3: The effect expected in H1 becomes weaker in the presence of an elite cue challenging the IO (moderating blaming effect).

Moving to the framing argument, research on IO legitimacy and IO legitimation discourses among domestic elites has indicated that the classic distinction between input and output legitimacy can still be observed (for the distinction, see Scharpf, 1999). Binder and Heupel (2015) demonstrate for the UN Security Council that legitimation discourses among the national representatives in the UN General Assembly in normal times are shaped by both procedural – that is, input-oriented – legitimacy criteria and performance – that is, output-oriented – criteria (Binder & Heupel, 2015). Subsequent research also confirmed that IOs’ procedures and performance matter equally in evoking public legitimacy beliefs (e.g. Anderson et al., 2019; Dellmuth et al., 2019). While this may be true in normal times, in times of crisis, we expect the performance criteria to affect citizens’ evaluations heterogeneously depending on their perceived affectedness. Because citizens worrying about a crisis should tend to demand immediate results, they would react more eagerly to the frame of IO effectiveness – that is, output criteria – used by political elites compared to the frame of IO impartiality – that is, input criteria (for the concept of impartiality, see Heinzel et al., 2020).

H4: The effect expected in H1 becomes stronger in the presence of an elite frame highlighting the effectiveness of the IO (moderating framing effect).

Research design

In the remainder, we first outline why we chose the COVID-19 pandemic and the WHO as the background for our survey experiment. Then, we discuss our case selection and sampling in more detail before moving to the setup of our experiment and the conditions included. Finally, we elaborate on the operationalization of the variables used in our models.

Experimental design – background

The COVID-19 pandemic is an example of a major transformative crisis that made the modern global interconnectedness particularly salient. Faced with a new challenge in their daily lives, many citizens are now directly affected by a problem whose dimensions exceed those of national politics. Yet, it is clear that not all citizens perceive this threat the same way, as the degree of worry about COVID-19 is different across sub-populations (Maaravi & Heller, 2020). Therefore, we expect to find a high degree of variation in COVID-19 related worries in our study, allowing us to study the complex effects of salience on individual legitimacy beliefs. Furthermore, the COVID-19 crisis is also an example where elite blame-shifting has been prevalent (Jaworsky & Qiaoan, 2020; Zahariadis et al., 2020). Since most countries were unable to contain the spread of the pandemic, many governments are still seeking to shift blame to other countries or international actors. Such blame-shifting was especially pronounced towards the WHO at the beginning of the pandemic. These strategies even led to the temporary stop of funding by the USA, threatening the existence of the WHO. This described combination of individually varying worries and real-world blame strategies allows us to create realistic experimental treatments to study our expectations in a controlled manner.

The WHO is the IO most affected by the COVID-19 crisis. However, there is no clear evidence if previous elite blaming strategies have been effective in the case of the WHO. Before the COVID-19 crisis, the WHO scored higher on public legitimacy than most other IOs (Dellmuth et al., 2021). Second, the WHO has been criticized for its actions during the Ebola and H2N2 pandemics in the past, without losing its high degrees of public legitimacy. Third, the WHO is an expert body, which means it is not necessarily associated with “politics” in the same way as other IOs. Consequently, one could consider the WHO case a difficult test for the argument that elites can use salient crises to undermine the legitimacy of an IO.

Experimental design – case selection

To test our expectations, we fielded a survey experiment in three countries: Austria, Germany and Turkey. The survey measures citizens’ attitudes toward the WHO in the three countries with a sample size of 1442 for Austria, 1418 for Germany, and 1512 for Turkey. We chose to use these three countries because although all three have experienced adverse shocks from the pandemic to relatively moderate degrees thanks to their efficient health systems and a high number of ICU units, they differ in several key characteristics especially in the aggregate favorability toward international organizations (from high to low: Germany > Austria > Turkey), their level of democracy (from high to low: Germany = Austria > Turkey), and the degree of incumbent’s populism (from high to low: Turkey > Austria > Germany). This, in turn, provides us with the opportunity to analyze the effects of our experimental set-up across varying levels of IO (un)favorability among the respective population as well as to control for potential interacting effects of context conditions such as elite’ degree of populism or a country’s level of democracy.

The empirical data for German and Austrian surveys were collected by Respondi between October 30 and November 09, 2020, using quota sampling based on gender, age and education. The Turkish survey was fielded by Twentify between October 20 and November 15, 2020, adopting quotas based on gender, age, and city to match the statistics of the general population.2 To increase data quality and minimize fraudulent response frequency, several attention-check questions were included, and data on those who failed them were not included in the analyses. For all three surveys, ethical approvals were granted, and respondents were briefly debriefed at the end of the experiments.

Table 1 demonstrates that, on average, our respondents are not only perceiving the WHO to be rather legitimate, they also demonstrate rather favorable attitudes toward their government and the United Nations. The Turkish sample contains relatively younger, slightly more educated respondents and respondents that perceive themselves to be more personally affected compared to the German and also the Austrian sample.3 Compared to pure convenience samples often used in experimental research, our samples are much closer to the actual population distribution of sociodemographic factors – such as age, gender, and education. Hence, while we are unable to and therefore do not generalize point estimates, our survey experiment data provides substantive variation in our key dependent, explanatory, and control variables that is needed to generalize the effects that a given variable has on another one.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Austria | Germany | Turkey | Total | |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | N | ||

| WHO Legitimacy | 0.60 | 0.22 | 0.64 | 0.21 | 0.63 | 0.23 | 4372 | |

| Covid: Personally Affected | 0.50 | 0.24 | 0.56 | 0.23 | 0.88 | 0.16 | 4372 | |

| Generalized Trust | 0.49 | 0.22 | 0.49 | 0.22 | 0.54 | 0.13 | 4372 | |

| Trust in Government | 0.55 | 0.25 | 0.57 | 0.25 | 0.64 | 0.26 | 4372 | |

| Trust in the UN | 0.52 | 0.23 | 0.53 | 0.22 | 0.60 | 0.22 | 4372 | |

| Age (years) | 43.68 | 14.20 | 44.59 | 14.27 | 33.90 | 11.04 | 4372 | |

| Austria | Germany | Turkey | ||||||

| N | Percent | N | Percent | N | Percent | |||

| Education | Low | 173 | 12 | 428 | 30.18 | 274 | 18.12 | |

| Medium | 755 | 52.36 | 476 | 33.57 | 616 | 40.74 | ||

| High | 514 | 35.64 | 514 | 36.25 | 622 | 41.14 | ||

| Gender | Female | 704 | 48.82 | 711 | 50.14 | 774 | 51.19 | |

| Male | 738 | 51.18 | 707 | 49.86 | 738 | 48.81 | ||

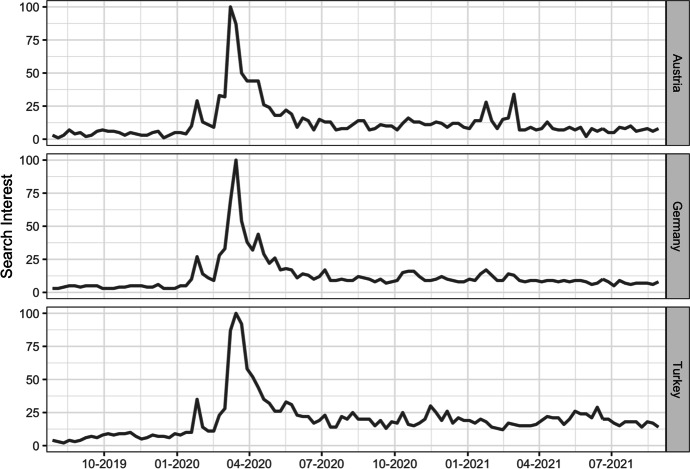

While we outline below how our experimental setting secures a high level of WHO awareness among all respondents – independent of them being politically interested or knowledgeable or not –, we also provide a quick look on whether our scope condition – the increasing level of public salience of the WHO during the pandemic – holds. Figure 1 demonstrates the Google searches for the topic World Health Organization in the respective language of the country in Austria (upper part), Germany (middle part) and Turkey (lower part). In all three countries, we observe a marked increase in Google searches for the WHO, around the time when the virus first emerged in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, and then peaked around March and April 2020, after the virus spread across European countries.4 Though the search numbers have declined in the following months, the average monthly searches continue to be well-above than the pre-pandemic period, despite the rising increase in the general public awareness about the WHO.

Fig. 1.

WHO salience during the COVID-19 pandemic

Experimental design – setup

Turning now to the specific setup of our experimental design, respondents first answered questions related to the demographic covariates used within our analyses below. Then, we asked respondents to read a short introductory statement presenting the WHO and its tasks focusing on its mandate in fighting pandemics such as COVID-19.

The statement reads as follows:

“The World Health Organization (WHO) is an international organization that supports member countries on health issues and helps the coordination of global activities against the spread of communicable diseases. The WHO is a sub-organization of the United Nations, and [Germany/Austria/Turkey] and most other countries in the world are members of the WHO and contribute to its budget.”

By doing so, we aimed to secure a high level of awareness of the WHO as being the IO mandated to solve or to support in solving the COVID-19 pandemic among all respondents. While this strategy reduces the variance in the awareness of the WHO across survey respondents, hence preventing us from testing the assumed correlation between the public salience of IOs and individual awareness about them.5 However, by increasing respondents’ awareness – and knowledge – to at least a basic level, this provides us the groundwork to test the three subsequent arguments (affectedness argument [H1], elite blaming argument [H2], interaction argument [H3, H4]).6 After his introduction to the WHO, respondents were exposed to an experimental treatment and the question measuring the dependent variable.

Experimental design – conditions

For the experiment, respondents were randomly assigned to one of eight experimental conditions (see Table 2). Three treatments were fully crossed to form the eight conditions, resulting in a 2 × 2 × 2 factorial design.

Table 2.

Overview over experimental manipulation (eight experimental groups)

| Domestic Government vs. the EU (Sponsor) | Blame vs. Praise (Blame) | Effectiveness vs. Impartiality (Frame) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Recently, the WHO and its role in combatting the COVID19 pandemic has become a matter of public debate. In this debate, … | ||||

| …the domestic government | has | criticized the WHO | for | being unable to effectively support its member states during the COVID-19-crisis” |

| …the domestic government | has | criticized the WHO | for | pursuing the specific interests of larger member states such as China, thereby not remaining neutral during the COVID-19-crisis” |

| …the domestic government | has | applauded the WHO | for | being able to effectively support its member states during the COVID-19-crisis” |

| …the domestic government | has | applauded the WHO | for | not just pursuing the specific interests of larger member states such as China, thereby remaining neutral during the COVID-19-crisis” |

| …the European Union | has | criticized the WHO | for | being unable to effectively support its member states during the COVID-19-crisis” |

| …the European Union | has | criticized the WHO | for | pursuing the specific interests of larger member states such as China, thereby not remaining neutral during the COVID-19-crisis” |

| …the European Union | has | applauded the WHO | for | being able to effectively support its member states during the COVID-19-crisis” |

| …the European Union | has | applauded the WHO | for | not just pursuing the specific interests of larger member states such as China, thereby remaining neutral during the COVID-19-crisis” |

First, we either treated respondents with an elite cue that either blames or praises the WHO for its role during the COVID-19 pandemic (blame). In the blame condition, the sponsor (see below) criticizes the WHO, while the WHO is applauded in the praise condition.

With the different frames of effectiveness versus impartiality we differentiate between an output versus input-oriented legitimacy framing of the WHO different sponsors (frame). The frame condition then provides the argument based on which the WHO is criticized or applauded for by the sponsor. Within the effectiveness frame, we take up the straightforward argument in public debates and the literature about IO being effective in fulfilling their mandates. In effect, then the WHO is either criticized for being unable to effectively support its member states or being applauded for being able to effectively support its member states. Within the impartiality frame, we take into account the public debates about the WHO being too soft on China (during the COVID-19 pandemic) or just prioritizing the interests of its most powerful members (see, e.g., Kirby, 2020). In essence, these accusations reflect doubts about the impartiality of the WHO. Yet, as Heinzel et al. (2020) convincingly argued, IOs need to be perceived as impartial to being able to efficiently implement their policies. In the combination of the impartiality frame and blame condition, the WHO is hence criticized for “pursuing the specific interests of larger member states such as China, thereby not remaining neutral during the COVID-19-crisis”, while the contrary frame of the WHO “not pursuing the specific interests of larger member states such as China, thereby remaining neutral during the COVID-19-crisis” is included in the praise condition.

Finally, previous research has shown that the potency of elite cues in shaping public opinion on IOs is closely influenced by the identity of the cue provider (e.g. Dellmuth & Tallberg, 2020a; Morse & Keohane, 2014). While we do not have theoretical expectations in the theoretical framework set out in this article, our experimental setting additionally included a third experimental dimension, sponsor. This dimension refers to the domestic government versus the EU as the cue sponsor. We report its direct effects to provide a full and transparent picture of the findings for the overall experimental setup.7

Dependent and independent variables

For our main dependent variable – respondents’ perception of WHO legitimacy – we asked respondents in Austria and Germany whether they consider the WHO to have a positive or negative influence on combatting the COVID-19 pandemic, with answer options ranging from 1 = “a very negative influence” to 11 = “a very positive influence”. In Turkey, we also asked citizens whether they consider the WHO to positively or negatively influence combatting the COVID-19 pandemic. In contrast to the fielding in Germany and Austria, the response could be given on a scale from 1 = “rather negative” to 5 = “rather positive”. This change is due to restrictions that we encountered in fielding our modules as part of a larger survey framework.

We consider both variables to come rather close to measuring legitimacy as they contain the explicit evaluation of whether or not the WHO fulfils its mandate – that is, supporting its member states in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic. While this is not a perfect measure of public IO legitimacy as it neglects the moral dimension of legitimacy – that is, whether a citizen is willing to follow the rulings of the WHO or not –, it certainly mirrors what Dellmuth and Schlipphak (2020) have recently called the rational dimension of legitimacy. Therewith, it is close to other concepts that have been used as proxies for measuring IO legitimacy, such as confidence in, satisfaction with or trust in IOs (for an overview, see Dellmuth & Schlipphak, 2020).

As our primary independent variable – the perception of being affected by the COVID-19 pandemic – we asked citizens whether they consider the COVID-19 pandemic as a threat to themselves, with answer options ranging from 1 = “no threat at all” to 6 = “a great threat”. In contrast to the sample in Germany and Austria, we asked respondents in Turkey, more specifically, whether citizens perceived COVID-19 as a potential threat to their own health, with answer options ranging from 1 = “do not feel threatened” to 5 = “feel rather threatened”.

We decided to use an egotropic variable here, in contrast to including a sociotropic variable, such as asking for the COVID-19 pandemic being a threat to the respondent’s country. We consider the COVID-19 pandemic to be a specific kind of threat because it is perceived to have a much more direct and intense effect on individual citizens’ well-being and life satisfaction compared to other threats. To test H3 and H4, we then interacted the frame and the blame treatment with the egotropic variable COVID-19 affectedness.

Furthermore, we used various control variables to estimate treatment effects more precisely. First, we used country fixed effects, distinguishing between respondents from Austria, Germany, and Turkey. Second, we control for the usual sociodemographics: age, education and gender. Third, taking most recent literature into account, we control for two additional variables that have been shown to strongly influence attitudes toward IOs: generalized trust (Dellmuth & Tallberg, 2020b) and governmental trust (Dellmuth & Tallberg, 2015; Harteveld et al., 2013; Schlipphak, 2015). We operationalized governmental trust by asking: “How much do you trust the [survey country] government?” and generalized trust by asking: “Do you think most people can be trusted?”. Respondents could answer on a scale of 1 to 6 (in Turkey: 1 and 2), with higher values indicating higher levels of trust.

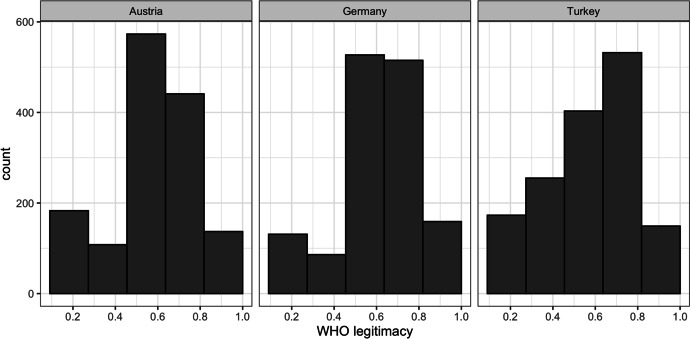

To test our hypotheses, we pool the samples of Germany, Austria and Turkey. Therefore, variables measured on different outcome scales had to be combined. To do so, we normalized egotropic affectedness, governmental and generalized trust, and the perceived influence of the WHO on combatting the pandemic to range from 0 to 1 (see Fig. 2). This transformation also allows us to directly compare regression coefficients and evaluate their strength in explaining our outcome variable. To estimate our treatment effects, we use OLS regression with covariate adjustment and country fixed effects.

Fig. 2.

Histogram of the dependent variable by country

Empirical findings

In Table 3,8 we report the models necessary to test our four hypotheses based on the data in all countries.9 In H1, we expected the perceived affectedness by COVID-19 to increase respondents’ perceived legitimacy of the WHO. This is indeed what we find in the first model, which only reports direct effects. The coefficient of 0.182 means that a respondent considering the COVID-19 pandemic to be a serious threat to oneself (1) demonstrates – on average – a 0.182-point higher value regarding WHO legitimacy than a respondent that considers COVID-19 to not at all being a threat to oneself (0).

Table 3.

Explaining WHO legitimacy by COVID-19 affectedness and elite challenge

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.393 (0.021)*** | 0.359 (0.023)*** | 0.418 (0.023)*** |

| Effectiveness (1) vs. Impartiality (0) | 0.004 (0.006) | 0.004 (0.006) | -0.044 (0.016)*** |

| Blame (1) vs. Praise (0) | -0.048 (0.006)*** | 0.016 (0.016) | -0.048 (0.006)*** |

| Domestic Government (1) vs. EU (0) | 0.001 (0.006) | 0.001 (0.006) | 0.001 (0.006) |

| COVID-19 Affectedness | 0.182 (0.015)*** | 0.232 (0.019)*** | 0.145 (0.019)*** |

| Blame vs. Praise × COVID-19 Affectedness | -0.098 (0.023)*** | ||

| Effectiveness vs. Impartiality × COVID-19 Affectedness | 0.073 (0.023)*** | ||

| Trust in Government | 0.251 (0.013)*** | 0.251 (0.013)*** | 0.251 (0.013)*** |

| Generalized Trust | 0.136 (0.017)*** | 0.135 (0.017)*** | 0.135 (0.017)*** |

| Num.Obs | 4372 | 4372 | 4372 |

| R2 | 0.173 | 0.177 | 0.175 |

| R2 Adj | 0.171 | 0.174 | 0.173 |

| Controls | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Country dummies | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Source: Self-administered survey experiment in Austria, Germany and Turkey

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.01, standard errors in parentheses

Regarding the experimental treatments, the blame vs. praise cue has a substantive and significant negative effect on WHO legitimacy: in the blame condition, respondents show significantly lower mean values of WHO legitimacy compared to the praise condition. This lends credence to our expectation formalized in H2. Neither the frame treatment nor the sponsor treatment demonstrate a significant effect on our dependent variable.10

In the second model, we test H3 that expects an interaction effect between the blame vs. praise treatment and COVID-19 affectedness. If H3 is to be confirmed by empirical reality, we should observe a negative effect of the interaction term. And indeed, we find a negative and significant coefficient of the interaction term in the Model 2 and a respective slight increase in strength for the direct effect of COVID-19 affectedness in the case of praising elite cues. Hence, H3 should also be considered to be corroborated by our data.

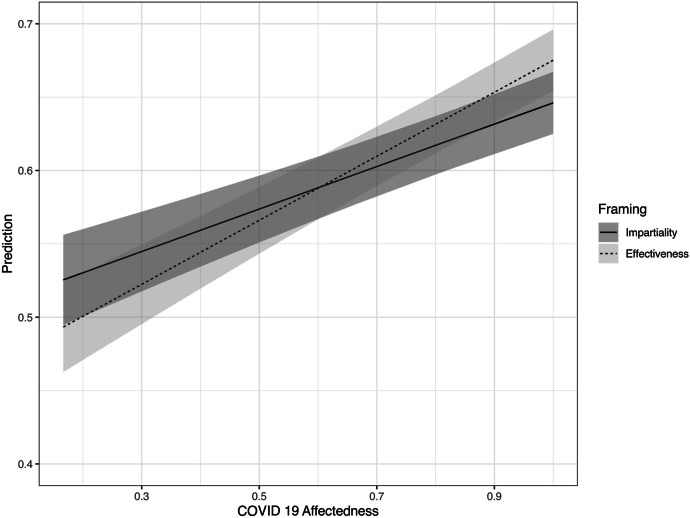

In the third model, we analyze whether our H4 – expecting an interaction effect between the frame treatment and COVID-19 affectedness – holds in reality. If so, we should expect a significant positive effect of the interaction term, indicating that the impact of citizens’ perceived affectedness on WHO attitudes becomes stronger when the WHO is framed in terms of effectiveness (compared to impartiality). Model 3 demonstrates such an effect, providing a first confirmation of our last theoretical argument.

These findings also become apparent in their visualization. Figure 3 shows the predicted values of WHO legitimacy across all values of COVID-19 affectedness, separately for the effectiveness and the impartiality frame treatments. Being less affected by COVID-19 leads citizens to become more sensitive toward the WHO in the impartiality frame compared to the effectiveness condition in their evaluations of the WHO. This relationship is reversed for citizens feeling more strongly affected by COVID-19. That is, for groups of citizens that vary in their perceived COVID-19 affectedness, different legitimacy criteria seem to be important.

Fig. 3.

Interaction of the frame treatment and COVID-19 Affectedness (95% Confidence intervals)

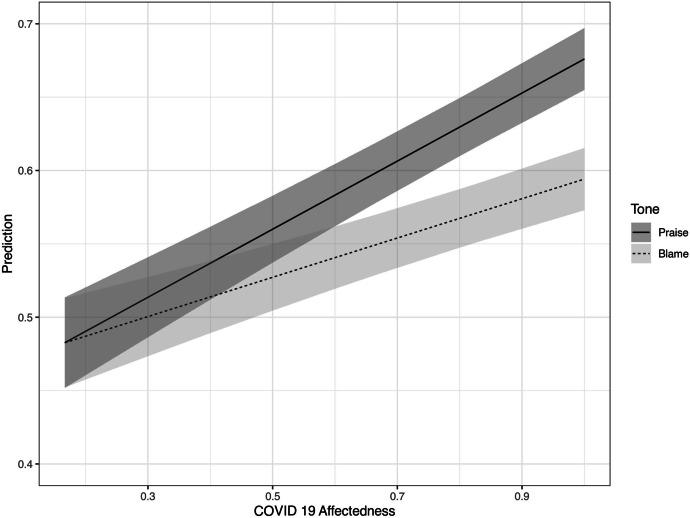

Figure 4 demonstrates the predicted values of WHO legitimacy across all values of COVID-19 affectedness, separately for the blame v. praise treatments. Note that the predicted values across the treatments diverge only at the higher level of COVID-19 affectedness – that is, the effect of the treatment makes a difference only for those respondents who consider themselves highly affected by COVID-19.

Fig. 4.

Interaction of the tone treatment and COVID-19 Affectedness (95% Confidence intervals)

Given that we only report the direct effects for each experimental dimension, we investigated whether there are any interactions between the different experimental treatments. Using an analysis of variance (ANOVA), we find no statistically significant interactions (see Table A6 in the appendix). We analyzed whether changing our dependent variable from the WHO legitimacy to a feeling that the WHO is personally beneficial results in changes to our main findings (see Table A7 in the appendix). We also changed the dependent variable to the judgment of whether or not the respondent’s country should leave the WHO (see Table A8 in the appendix). In both cases, our H1 – that COVID-19 affectedness lead to a substantially and significantly higher level of IO legitimacy – is supported by the data. Also, for both dependent variables we find a direct effect of the blame vs. praise treatments, strengthening our belief in H2. We also observe significant moderation effects (H3 and H4) using the dependent variable measuring the feeling of personal benefit (see Table A7 in the appendix). However, we do not find these effects when looking at the favorability of leaving the WHO. Hence, the relationship described above only seems to hold evaluations of the WHO, but not for the willingness to change the respondent’s country diplomatic stance (see Table A8 in the appendix).

Discussion and conclusion

Do international crises affect IO public legitimacy besides seemingly exerting pressure on the IO to legitimize themselves? In this article, we argue that international crises make those IOs with the mandate to – participate in – solving the crisis more salient in public debates elites and hence more aware to citizens. This should have three effects. First, citizens should be more likely to link their – crisis-induced – affectedness directly to the IO that is mandated to solve – or support in solving – the crisis and, hence, demonstrate higher levels of IO public legitimacy (H1). However, as the increased salience of the IO in public debates also opens the floor to its politicization and contestation by domestic actors – that is, an increasingly visible fight between political actors praising or blaming the respective IO. Therefore, we expect, second, that political elites blaming IOs in times of crisis decreases IOs’ public legitimacy (H2). And, third, political elite cues with regard to the effectiveness of the IOs in crisis management (frame) and negative assessments on IO performance (blame) should moderate the effect of citizens’ crisis affectedness (H3, H4).

Using self-administered data, including survey experiments with close to 4400 respondents in Austria, Germany and Turkey, the empirical findings corroborate our theoretical expectations. Citizens that perceive themselves to being more strongly affected by COVID-19 consider the WHO to be more legitimate (= H1), but the effect of citizens’ affectedness on WHO legitimacy is moderated by framing (frame condition) and blaming (blame condition) as part of elite communication. Framing the WHO in terms of effectiveness compared to impartiality makes citizens feeling more affected by COVID-19 even more favorable toward the WHO (= H3), while the opposite is true for citizens feeling less to not at all affected. In contrast, in a condition with a blaming treatment, the positive effect of citizens’ COVID-19 induced worries becomes significantly weaker compared to a condition with a praising treatment (= H3). Additionally, such a blaming treatment makes citizens generally more skeptical toward the WHO (= H2).

Yet, as our findings are the first to shed more light on the effects of crisis on these aspects of IO legitimacy, they come with several caveats that need to be addressed by future research. First, while we did not expect and did not find significant effects of the sponsor of the WHO praise or blaming in our experimental setting, this factor may still play a role in other settings, theoretically as well as empirically.11 Second, our research design is based on stimulating the IO awareness to a similar degree among all respondents. Future research may analyze whether a) IO awareness among citizens is influenced by increasing IO salience in public debate – as we showed that the latter becomes actually visible using Google search trends – and if b) varying levels of IO awareness among citizens may result in different effects for these divergent groups of citizens. This calls for linkage of content and survey data which has so far been seldomly used in the realm of IO research (De Vreese et al., 2017). Third, though our experiments demonstrated robust evidence for the proposed association between crisis affectedness and legitimacy beliefs on IOs in all three country contexts, given that our samples were not representative, the question of the extent to which these results are generalizable remains. Further research with large-N cross-national data with representative samples could alleviate such concerns.

Finally, and fourth, future research should also delve further into the moderating effect of time in conditioning legitimacy beliefs over the course of crises, possibly utilizing panel data. As a crisis evolves, citizens may learn more about the IO’s actual mandate, capabilities, and limitations. Consequently, they may revise their expectations and legitimacy beliefs. The timing of our survey was right before the beginning of the second wave in the countries with relatively declining death figures and relative easing of restrictions following the first wave. Despite such relatively benign conditions during the survey period, we were able to identify significant effects of COVID-induced worries on legitimacy beliefs toward the WHO. Hence, tentatively we would expect to observe even greater treatment effects at the peak of the crisis. One should note, however, that a necessary condition for this outcome, we posit, is the increased salience of IOs during the crises within their mandates, which causes citizens to rely on crisis-induced worries in developing legitimacy beliefs on IOs.

Following this, critics may wonder what our results tell us about the IO legitimacy in ‘regular’ times? For us, there is a definite answer to this. Global crises seem to be here to stay (for a similar point, see Lipscy, 2020). In our view, given especially the great potential for conflict that financial shocks, climate change and its effects, but also viruses – both biological and algorithmic – may have on the economic, financial, and political interconnectedness of states, we should expect more global crises to come over the following years. As a consequence, the level of public salience and citizens’ awareness of global governance, multilateralism and its organizations should also be expected to increase further rather than decrease.

Some may raise the question whether different crises have the same effect on public attitudes toward IO – that is, whether a financial crisis may lead to higher levels of attitudes toward the IMF. We argue that the mechanisms outlined here – those of citizens’ level of perceived affectedness and of elite communication – should be the same regardless of the type of global crisis. Nevertheless, and this is one of the cores of our argument, the actual size of effects would vary across crises depending on the degree of citizens’ affectedness as well as the frame and tone the governmental actors –are able to- raise in different contexts.

When it comes to transferring our findings to other country contexts, such as in poorer and more autocratic countries of the Global South, our argument would be similar. Arguably, because poorer countries’ host populations are potentially more vulnerable to health and similar types of crises, IOs can garner even greater public legitimacy in these geographies in times of crisis. As an additional mechanism, the perceived threats such crises invoke among the local populations may disproportionally raise public discontent toward the national governments that failed to effectively cope with the detrimental effects. The perception of weak governance at home may lead to higher confidence in IOs, which are perceived to be mandated in solving the crisis. As an example of this mechanism, Arpino and Obydenkova (2020) found that while the public trust in national parliaments considerably declined among the least democratic European countries following the 2008 Economic Crisis, trust in the EU, meanwhile, increased. On the other hand, in autocracies, political elites have a firmer grip on the mass media and communication channels (but see Isani and Schlipphak (2020). Hence, given the different role that political elites play in framing public attitudes in such contexts, to what extent and in which direction the elite communication on IOs would moderate the hypothesized positive effects of crisis-induced worries in autocratic countries should be explored in future research on the topic.

In conclusion, we shed some first light on the correlation between the public salience of IOs and their public legitimacy, and we consider this correlation to be of ever-increasing relevance for the scientific community and practitioners alike. This makes our findings interesting to researchers working on exploring the effect of individual predispositions on IO attitudes and researchers focusing on institutional and strategic reforms of IOs and, more generally, any attempt of IO self-legitimation.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Declarations

Competing interests

This work was supported by Tubitak, Grant no. 120K600. The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Footnotes

In fact, this seems to be one of the mechanisms why previously unthinkably large portions of citizens vote for populist parties. It is not because they consider them to be able to solve the problems perceived by citizens, but because these parties seem to care.

For the Turkish sample, there was moderate deviation from the national averages on the education variable, as 40 percent of our respondents were university graduates, 41 percent high-school graduates and 19 percent had education levels below high school.

This slightly different sample structure may also explain the fact that trust in the UN is comparatively high among Turkish respondents.

Google Trends data from July 2019 to August 2021 for the topic “World Health Organization”, plotted by country. The Google Trends data has been scaled on a range of 0 to 100, with 100 being the highest number of searches on the topic by Google users within the respective country in the selected time frame.

We chose this strategy to assure that our experimental variation only influences the desired aspects and does not affect respondent’s understanding of the WHO, which could also change attitudes towards it (Dafoe et al., 2018).

For respondents in Germany and Austria, an additional factual manipulation check was used to exclude highly inattentive participants who did not read the introduction. Respondents were asked to read the introductory statement carefully. On a new screen, they were asked: “The WHO is a sub-organization of which international organization?”. Respondents who did not choose “The United Nations” as an answer were excluded from the survey.

For an overview, see Table A1 in the appendix that is available on The Review of International Organizations’ website.

For the sake of brevity, we do not report the effects of our control variables here, since they are not of substantive interest. The full regression table is reported in Table A2 in the appendix.

The interactions between treatments are also not statistically significant (see Table A6 in the appendix).

E.g., previous research on public opinion and foreign policy establishes that particularly on policy issues where voter polarization is high, the identity of the elite messenger and its partisan position affect the way its message is perceived (e.g. Guisinger & Saunders, 2017).

Author contributions to literature review and theoretical argument: BS (50%), PM (20%), OSK (30%); research design and conceptualization: BS (50%), PM (30%), OSK (20%); statistical analysis: BS (25%), PM (55%), OSK (20%), writing: BS (55%), PM (15%), OSK (30%).

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Anderson B, Bernauer T, Kachi A. Does international pooling of authority affect the perceived legitimacy of global governance? Review of International Organizations. 2019;14(4):661–683. doi: 10.1007/s11558-018-9341-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arceneaux K. Can Partisan cues diminish democratic accountability? Political Behavior. 2008;30(2):139–160. doi: 10.1007/s11109-007-9044-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arpino, B., & Obydenkova, A. V. (2020). Democracy and political trust before and after the great recession 2008: The European Union and the United Nations. Social Indicators Research, 148(2), 395–415. 10.1007/s11205-019-02204-x

- Avdagic S, Savage L. Negativity bias: The impact of framing of immigration on welfare state support in Germany, Sweden and the UK. British Journal of Political Science. 2019;51(2):624–645. doi: 10.1017/S0007123419000395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Binder, M., & Heupel, M. (2015). The legitimacy of the UN Security Council: evidence from recent general assembly debates. International Studies Quarterly,59(2), 238–250. 10.1111/isqu.12134

- Buchanan A, Keohane RO. The legitimacy of global governance institutions. Ethics & International Affairs. 2006;20(4):405–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7093.2006.00043.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dafoe A, Zhang B, Caughey D. Information equivalence in survey experiments. Political Analysis. 2018;26(4):399–416. doi: 10.1017/pan.2018.9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries C, Hobolt S, Walter S. Politicizing international cooperation: the mass public, political entrepreneurs, and political opportunity structures. International Organization. 2021;75(2):306–332. doi: 10.1017/S0020818320000491. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Vreese CH, Boukes M, Schuck A, Vliegenthart R, Bos L, Lelkes Y. Linking survey and media content data: opportunities, considerations, and pitfalls. Communication Methods and Measures. 2017;11(4):221–244 . doi: 10.1080/19312458.2017.1380175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries CE, Edwards EE. Taking Europe to its extremes: extremist parties and public euroscepticism. Party Politics. 2009;15(1):5–28. doi: 10.1177/1354068808097889. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dellmuth L, Schlipphak B. Legitimacy beliefs towards global governance institutions: A research agenda. Journal of European Public Policy. 2020;27(6):931–943. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2019.1604788. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dellmuth L. The knowledge gap in world politics: Assessing the sources of citizen awareness of the United Nations Security Council. Review of International Studies. 2016;42(4):673–700. doi: 10.1017/S0260210515000467. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dellmuth L, Tallberg J. The social legitimacy of international organizations: Interest representation, institutional performance, and confidence extrapolation in the United Nations. Review of International Studies. 2015;41(3):451–475. doi: 10.1017/S0260210514000230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dellmuth, L., & Tallberg, J. (2020a). Elite Communication and the Popular Legitimacy of International Organizations. British Journal of Political Science, 1-22. 10.1017/S0007123419000620

- Dellmuth L, Tallberg J. Why national and international legitimacy beliefs are linked: Social trust as an antecedent factor. Review of International Organizations. 2020;15(2):311–337. doi: 10.1007/s11558-018-9339-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dellmuth L, Scholte JA, Tallberg J. Institutional sources of legitimacy for international organisations: Beyond procedure versus performance. Review of International Studies. 2019;45(4):627–646. doi: 10.1017/S026021051900007X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dellmuth, L., Scholte, J. A., & Tallberg, J., & Verhaegen, S. (2021). The elite–citizen gap in international organization legitimacy. American Political Science Review, 1–18. 10.1017/S0003055421000824

- Dür, A., & Schlipphak, B. (2020). Elite cueing and attitudes towards trade agreements: The case of TTIP. European Political Science Review, 13(1), 41–57. 10.1017/S175577392000034X

- Ecker-Ehrhardt, M. (2016). Why do Citizens Want the UN to Decide? Cosmopolitan Ideas, Particularism and Global Authority. International Political Science Review, 37(1), 99–114. 10.1177/0192512114540189

- Ecker-Ehrhardt M. International organizations ‘Going Public’? An event-history analysis of public communication reforms from 1950 to 2015. International Studies Quarterly. 2018;62(4):723–736. doi: 10.1093/isq/sqy025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ecker-Ehrhardt M. Self-legitimation in the face of politicization: Why international organizations centralized public communication. Review of International Organizations. 2018;13(4):519–546. doi: 10.1007/s11558-017-9287-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fazal, T. M. (2020). Health Diplomacy in Pandemical Times. International Organization, 1–20. 10.1017/S0020818320000326

- Fordham B, Kleinberg K. How Can Economic Interests Influence Support for Free Trade? International Organization. 2012;66(2):311–328. doi: 10.1017/S0020818312000057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Franck T. The power of legitimacy among nations. Oxford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gabel M. Interests and integration: Market liberalization, public opinion, and European Union. University of Michigan Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gabel, M., & Scheve, K. (2007). Mixed messages: Party dissent and mass opinion on European integration. European Union Politics, 8(1), 37–59. 10.1177/1465116507073285

- Genna G. Images of Europeans: Transnational trust and support for European integration. Journal of International Relations Development. 2017;20(2):358–380. doi: 10.1057/jird.2015.9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guisinger A, Saunders EN. Mapping the boundaries of elite cues: How elites shape mass opinion across international issues. International Studies Quarterly. 2017;61(2):425–441. doi: 10.1093/isq/sqx022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harteveld, E., van der Meer, T., & De Vries, C. E. (2013). In Europe we trust? Exploring three logics of trust in the European Union. European Union Politics, 14(4), 542–565. 10.1177/1465116513491018

- Heinkelmann-Wild T, Zangl B. Multilevel blame games: Blame-shifting in the European Union. Governance. 2020;33(4):953–969. doi: 10.1111/gove.12459. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heinzel, M., Richter, J., Busch, P.-O., Feil, H., Herold, J. & Liese, A. (2020). Birds of a feather? The determinants of impartiality perceptions of the IMF and the World Bank. Review of International Political Economy. 10.1080/09692290.2020.1749711

- Held D. Democracy and the Global Order. Cambridge University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hobolt SB, Wratil C. Public opinion and the crisis: The dynamics of support for the euro. Journal of European Public Policy. 2015;22(2):238–256. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2014.994022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hobolt SB, De Vries CE. Public support for European integration. Annual Review of Political Science. 2016;19:413–432. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-042214-044157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hooghe L, Marks G. Calculation, community and cues: Public opinion on European integration. European Union Politics. 2005;6(4):419–443. doi: 10.1177/1465116505057816. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd, I. (2007). After anarchy: Legitimacy and power in the United Nations Security Council. Princeton University Press.

- Isani, M., & Schlipphak, B. (2020). The role of societal cues in explaining attitudes toward international organizations: the least likely case of authoritarian contexts. Political Research Exchange, 2(1). 10.1080/2474736X.2020.1771189

- Jaworsky BN, Qiaoan R. The politics of blaming: The narrative battle between China and the US over COVID-19. Journal of Chinese Political Science. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11366-020-09690-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jetschke, A., & Schlipphak, B. (2020). MILINDA: A new dataset on United Nations-led and non-united Nations-led peace operations. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 37(5), 605–629. 10.1177/0738894218821044

- Johnson T. Guilt by association: The link between states’ influence and the legitimacy of intergovernmental organizations. Review of International Organizations. 2011;6(1):57–84. doi: 10.1007/s11558-010-9088-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenthaler K, Miller WJ. Social psychology and public support for trade liberalization. International Studies Quarterly. 2014;57(4):784–790. doi: 10.1111/isqu.12083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keohane RO. Global governance and legitimacy. Review of International Political Economy. 2011;18(1):99–109. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2011.545222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, J. (2020). How to fix the WHO, according to an expert. Vox, May 29, 2020. Available at https://www.vox.com/2020/4/19/21224305/world-health-organization-trump-reform-q-a. Accessed 9 Sep 2021.

- Kiratli, O. S. (2020). Together or not? Dynamics of public attitudes on UN and NATO. Political Studies, 1-22. 10.1177/0032321720956326

- Lipscy, P. Y. (2020). COVID-19 and the politics of crisis. International Organization, 1–30. 10.1017/S0020818320000375

- Maaravi Y, Heller B. Not all worries were created equal: The case of COVID-19 anxiety. Public Health. 2020;185:243–245. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield E, Mutz D. Support for free trade: Self-interest, sociotropic politics, and out-group anxiety. International Organization. 2009;63(3):425–457. doi: 10.1017/S0020818309090158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLaren LM. Public support for the European union: Cost/benefit analysis or perceived cultural threat? Journal of Politics. 2002;64(2):551–566. doi: 10.1111/1468-2508.00139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morse, J. C., & Keohane, R. O. (2014). Contested multilateralism. Review of International Organizations,9(4), 385–412.

- Scharpf FW. Governing in Europe: Effective and Democratic? Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Scheve KF, Slaughter MJ. What determines individual trade-policy preferences? Journal of International Economics. 2001;54(2):267–292. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1996(00)00094-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schlipphak B. Measuring attitudes toward regional organizations outside Europe. Review of International Organizations. 2015;10(3):351–375. doi: 10.1007/s11558-014-9205-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schlipphak B, Treib O. Playing the blame game on Brussels: The domestic political effects of EU interventions against democratic backsliding. Journal of European Public Policy. 2017;24(3):352–365. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2016.1229359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidtke H. Elite legitimation and delegitimation of international organizations in the media: Patterns and explanations. Review of International Organizations. 2019;14(4):633–659. doi: 10.1007/s11558-018-9320-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steenbergen, M. R., Edwards, E. E., & De Vries, C. E. (2007). Who’s Cueing Whom? Mass-Elite Linkages and the Future of European Integration. European Union Politics, 8(1), 13–35. 10.1177/1465116507073284

- Steiner ND. Attitudes towards the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership in the European Union: The treaty partner heuristic and issue attention. European Union Politics. 2018;19(2):255–277. doi: 10.1177/1465116518755953. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tallberg J, Zürn M. The legitimacy and legitimation of international organizations: Introduction and framework. Review of International Organizations. 2019;14(4):581–606. doi: 10.1007/s11558-018-9330-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilopoulou S, Halikiopoulou D, Exadaktylos T. Greece in crisis: austerity, populism and the politics of blame. Journal of Common Market Studies. 2014;52(2):388–402. doi: 10.1111/jcms.12093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wlezien, C. (2005). On the salience of political issues: The problem with ‘most important problem.’ Electoral Studies,24(4), 555–579. 10.1016/j.electstud.2005.01.009

- Zahariadis N, Petridou E, Oztig LI. Claiming credit and avoiding blame: Political accountability in Greek and Turkish responses to the COVID-19 crisis. European Policy Analysis. 2020;6(2):159–169. doi: 10.1002/epa2.1089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.