Summary

Background

We aimed to describe pre-existing factors associated with severe disease, primarily admission to critical care, and death secondary to SARS-CoV-2 infection in hospitalised children and young people (CYP), within a systematic review and individual patient meta-analysis.

Methods

We searched Pubmed, European PMC, Medline and Embase for case series and cohort studies published between 1st January 2020 and 21st May 2021 which included all CYP admitted to hospital with ≥ 30 CYP with SARS-CoV-2 or ≥ 5 CYP with PIMS-TS or MIS-C. Eligible studies contained (1) details of age, sex, ethnicity or co-morbidities, and (2) an outcome which included admission to critical care, mechanical invasive ventilation, cardiovascular support, or death. Studies reporting outcomes in more restricted groupings of co-morbidities were eligible for narrative review. We used random effects meta-analyses for aggregate study-level data and multilevel mixed effect models for IPD data to examine risk factors (age, sex, comorbidities) associated with admission to critical care and death. Data shown are odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

PROSPERO: CRD42021235338

Findings

83 studies were included, 57 (21,549 patients) in the meta-analysis (of which 22 provided IPD) and 26 in the narrative synthesis. Most studies had an element of bias in their design or reporting. Sex was not associated with critical care or death. Compared with CYP aged 1–4 years (reference group), infants (aged <1 year) had increased odds of admission to critical care (OR 1.63 (95% CI 1.40–1.90)) and death (OR 2.08 (1.57–2.86)). Odds of death were increased amongst CYP over 10 years (10–14 years OR 2.15 (1.54–2.98); >14 years OR 2.15 (1.61–2.88)).

The number of comorbid conditions was associated with increased odds of admission to critical care and death for COVID-19 in a step-wise fashion. Compared with CYP without comorbidity, odds ratios for critical care admission were: 1.49 (1.45–1.53) for 1 comorbidity; 2.58 (2.41–2.75) for 2 comorbidities; 2.97 (2.04–4.32) for ≥3 comorbidities. Corresponding odds ratios for death were: 2.15 (1.98–2.34) for 1 comorbidity; 4.63 (4.54–4.74) for 2 comorbidities and 4.98 (3.78–6.65) for ≥3 comorbidities. Odds of admission to critical care were increased for all co-morbidities apart from asthma (0.92 (0.91–0.94)) and malignancy (0.85 (0.17–4.21)) with an increased odds of death in all co-morbidities considered apart from asthma. Neurological and cardiac comorbidities were associated with the greatest increase in odds of severe disease or death. Obesity increased the odds of severe disease and death independently of other comorbidities. IPD analysis demonstrated that, compared to children without co-morbidity, the risk difference of admission to critical care was increased in those with 1 comorbidity by 3.61% (1.87–5.36); 2 comorbidities by 9.26% (4.87–13.65); ≥3 comorbidities 10.83% (4.39–17.28), and for death: 1 comorbidity 1.50% (0.00–3.10); 2 comorbidities 4.40% (-0.10–8.80) and ≥3 co-morbidities 4.70 (0.50–8.90).

Interpretation

Hospitalised CYP at greatest vulnerability of severe disease or death with SARS-CoV-2 infection are infants, teenagers, those with cardiac or neurological conditions, or 2 or more comorbid conditions, and those who are obese. These groups should be considered higher priority for vaccination and for protective shielding when appropriate. Whilst odds ratios were high, the absolute increase in risk for most comorbidities was small compared to children without underlying conditions.

Funding

RH is in receipt of a fellowship from Kidney Research UK (grant no. TF_010_20171124). JW is in receipt of a Medical Research Council Fellowship (Grant No. MR/R00160X/1). LF is in receipt of funding from Martin House Children's Hospice (there is no specific grant number for this). RV is in receipt of a grant from the National Institute of Health Research to support this work (grant no NIHR202322). Funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Keywords: Child, Adolescent, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Meta-analysis, Systematic review, Mortality, Severity, Hospitalisation, Intensive care, Chronic condition, Risk factor

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and young people (CYP) very rarely causes severe disease and death. Recent publications describe the risk factors for severe disease in specific populations but the global experience has not been described. Pubmed, European PubMed Central (PMC), Medline and Embase were searched including key search concepts relating to COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR PIMS-TS OR MIS-C AND Child OR Young person OR neonate from the 1st January 2020 to 21st May 2021. Studies with ≥30 children admitted to hospital with reverse transcriptase-PCR confirmed SARS-CoV-2 or ≥5 CYP defined as having paediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporally associated with COVID-19 (PIMS-TS) or multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) were included. 57 studies (21,549 children) met the eligibility criteria for meta-analysis and 22 studies provided data (10,022 patients) for individual patient data meta-analysis.

Added value of this study

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to use individual patient data to compare the odds and risk of critical care admission and death in CYP with COVID-19 and PIMS-TS. We find that the odds of severe disease in hospitalised CYP is increased in those with multiple co-morbidities, cardiac and neurological co-morbidities and those who are obese. However, the additional risk compared to CYP without co-morbidity is small.

Implications of all the available evidence

Severe COVID-19 and PIMS-TS, whilst rare, can occur in CYP. We have identified pre-existing risk factors for severe disease after SARS-CoV-2 and recommend that those with co-morbidities which place them in the highest risk groups are prioritised for vaccination.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

Children and young people (CYP) have suffered fewer direct effects of the COVID-19 pandemic than adults, and the vast majority experience mild symptoms following SARS-CoV-2 infection.1, 2, 3 However a small minority experience more severe disease4 and small numbers of deaths have been documented.5,6 As severe outcomes amongst CYP are uncommon, our understanding of which are at risk from SARS-CoV-2 is limited, in contrast to adults. Yet identification of CYP at the highest risk of critical illness or death from infection and its sequelae is essential for guiding clinicians, families and policymakers to identify groups to be prioritised for vaccination, and other protective interventions.

SARS-CoV-2 infection in hospitalised CYP has two primary manifestations. The first is acute COVID-19 disease, an acute illness caused by current infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus and often characterised by respiratory symptoms. The second is a delayed inflammatory condition referred to as Paediatric Inflammatory Multisystem Syndrome Temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 (PIMS-TS) or Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C).7, 8–9 Postulated risk factors for developing more severe COVID-19 or PIMS-TS / MIS-C include existing co-morbid conditions, age, sex, ethnicity, socio-economic group, and geographical location.10, 11, 12, 13 Existing systematic evaluations are not useful for guiding policy as reviews were undertaken early in the pandemic,14, 15, 16 included highly heterogeneous groups and a wide range of outcomes from very small studies,17 and failed to distinguish between acute COVID-19 and PIMS-TS/MIS-C. Rapid growth in the literature over the past year provides an opportunity to synthesize findings, and better inform policy decisions about vaccination and protective shielding of vulnerable CYP.

We undertook a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature from the first pandemic year with the aim of identifying which CYP were at increased risk of severe disease or death in CYP admitted to hospital with SARS-CoV-2 infection or PIMS-TS / MIS-C.

Methods

The protocol for this systematic review and meta-analysis was published on PROSPERO (CRD42021235338) on the 5th February 2021. We report findings according to the PRISMA 2020 guidelines18 (Supplementary information 1). The systematic review was limited to hospitalised CYP to enable the baseline denominator characteristics to be more accurately defined, particularly co-morbidities, and because in itself, hospital admission is an indicator of severity. We limited our review to pre-specified potential risk-factors (co-morbidities, age, sex, ethnicity and socioeconomic deprivation), plus a limited number of outcomes denoting severe disease (critical care admission, need for mechanical invasive ventilation or cardiovascular support) and death.

Search strategy and selection criteria

We performed a systematic search of four major databases: PubMed, European PubMed Central (PMC), Scopus and Embase for relevant studies on COVID-19 in CYP aged 0–21 years of age, published between the 1st January 2020 and the 29th January 2021 and updated the search on the 21st May 2021. Searches were limited to English only and included key search concepts relating to COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR PIMS-TS OR MIS-C AND Child OR Young person OR neonate (full search strategy in supplementary information (1). References of published systematic reviews and included studies were checked for additional studies.

Two reviewers selected studies using a two-stage process. All titles and abstracts were reviewed independently in duplicate by a team of five reviewers to determine eligibility. Full texts of articles were reviewed if inclusion was not clear in the abstract. Disagreements were discussed between the two reviewers and a decision made about inclusion or exclusion of the study. We excluded studies if the data were duplicated elsewhere, as reported by the study authors, and prioritised the studies which gave comparative data on the risk factors and outcomes of interest; if both did so, we used the larger study.

Inclusion criteria were as follows:

-

1

Observational studies of any type of CYP under 21 years of age who had been admitted to hospital with a finding of COVID-19 infection at or during admission OR who had been identified clinically as having PIMS-TS or MIS-C. All patients included in the IPD analysis with a diagnosis of COVID-19 had reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) confirmed SARS-CoV-2.

-

2

Data were provided on any of the following potential risk factors: age, sex, ethnicity, co-morbidity and socioeconomic deprivation.

-

3

Studies that included all admitted CYP in a population or institution regardless of co-morbidity were eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis if they included ≥30 children with COVID-19 or ≥5 children with PIMS-TS or MIS-C. Thirty or more children with COVID-19 was selected as the minimum a-priori to account for the outcomes of admission to critical care and death being rare, with previous systematic reviews suggesting severe COVID-19 occurs in approximately 2.5% of children.19 Studies of a single pre-existing co-morbidity were included in the systematic review if they included ≥5 children but not included in the meta-analysis.

-

4

Studies which reported one of the following outcomes as a proxy for severe disease:

-

(1)

Need for invasive ventilation during hospital stay (not including during anaesthesia for surgical procedures).

-

(2)

Need for cardiovascular support (vasopressors, inotropes +/- extracorporal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)).

-

(3)

Need for critical/intensive care.

-

(4)

Death after diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection or PIMS-TS/MIS-C.

We initially intended to include other identifiers indicative of severe disease including use of pharmacological therapy and length of stay in critical care, but were unable to reliably capture these as they were rarely and inconsistently reported. In analyses, CYP who did not have an indicator of severe disease but had COVID-19 or PIMS-TS/MIS-C and were admitted to hospital were used as the comparator group.

Data on risk factors and outcome variables were extracted from individual studies by one reviewer using a pre-designed data collection form and extraction was cross-checked by a second reviewer in 10% of studies. Authors of studies from the first search (to January 2021) were contacted by email and asked to provide either additional aggregated data demonstrating the relationship between predictor and outcome variables or IPD. Time did not allow these to be requested for studies identified in the second search (to May 2021). IPD were shared by authors using a standardised data collection form and checked for consistency with the original publication. Any queries from sharing authors or the study team were discussed over email or by a video call. Eligible studies not supplying IPD in a way that enabled the relationship between risk factors and outcomes to be analysed or that did not provide aggregate or individual patient data were excluded from the meta-analysis.

We assessed the studies for bias using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale20 to assess the quality of observational studies. Studies were scored according to selection of participants, comparability, and outcome. The description of comparator cohorts was deemed present when analyses comparing two groups of outcomes were described within the publication.

Data analysis

Meta-analyses were undertaken separately for COVID-19 and PIMS-TS/MIS-C to examine the association of each clinical outcome with sex (female sex was the reference group), age-group (1–4 years as reference group) and comorbidities (CYP without any comorbidity were the reference group). CYP who were RT-PCR positive for SARS-CoV-2 but met the criteria for PIMS-TS or MIS-C were included in the latter group.

Meta-analyses were conducted in two ways. First, we undertook a random-effects meta-analysis of reported study-level data using RevMan 5 software21 to estimate pooled odds-ratios for each outcome (death, intensive care admission, mechanical invasive ventilation and cardiovascular support). We refer to this analysis as the aggregate meta-analysis. Age categories were described as < 1 year, 1–4 years, 5–9 years, 10–14 years and 15–21 years. When studies reported a different age grouping, the group was used in the range which had the greatest cross-over of years. Co-morbidity data were compared using the presence and absence of individual co-morbidities. We calculated the I2 statistic as a measure of heterogeneity and report prediction intervals. Funnel plots were examined to assess the evidence for publication bias. We then performed a sensitivity analysis by excluding the largest study of patients with COVID-19. The second set of meta-analyses were undertaken on the IPD, using multi-level logistic mixed-effects models in Stata 16 (StataCorp. College Station, TX) including a random effect for study, with models for co-morbidities adjusted for age and sex. After each model we calculated the predicted probability for each outcome amongst those with and without each comorbidity using the margins post estimation command. We did this to estimate risk difference for admission to critical care or death amongst CYP with comorbidities compared to those without. As a sensitivity analysis, a two-stage meta-analysis was conducted using study-level estimates calculated from the IPD data. A further sensitivity analysis for both the aggregate and IPD meta-analyses was performed by excluding one very large study.22 Eligible studies which included only CYP with specific comorbidities were not included in the meta-analyses but included in a narrative synthesis. Data displayed are odds ratio (95% confidence interval) and absolute risk difference (95% confidence interval).

Role of the funding source

RH is in receipt of a fellowship from Kidney Research UK, JW is in receipt of a Medical Research Council Fellowship, LF is in receipt of funding from Martin House Children's Hospice and RV is in receipt of a grant from the National Institute of Health Research to support this work. Funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Results

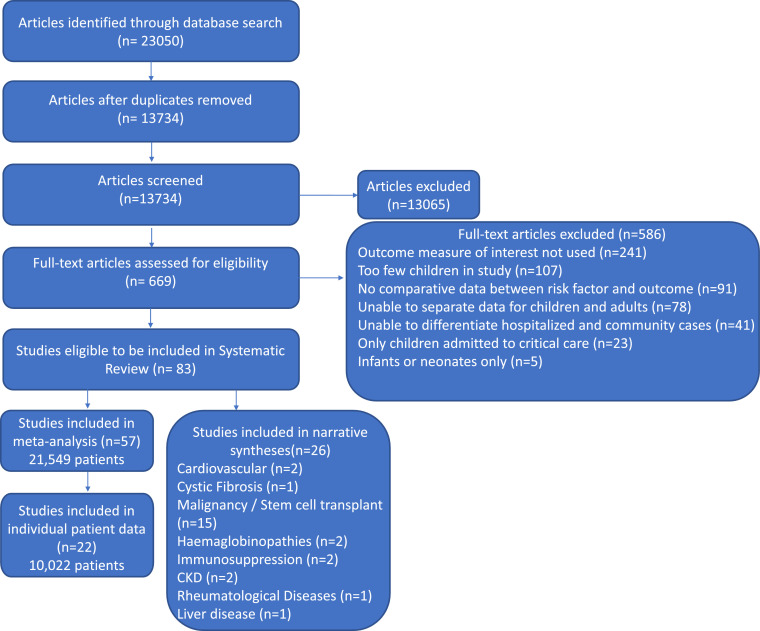

Figure 1 shows the search flow, 23,050 reports were identified. After excluding duplicates and ineligible studies, 83 studies were included in the review. Fifty-seven studies were included in the meta-analysis, including a total of 21,549 children (see Table 1). Ten studies were from Asia, fifteen from Europe, one from Africa, twenty-one from North America and nine from South America. One study had global recruitment.

Figure 1.

Description of the study search and selection process.

Table 1.

Study characteristics of ‘All comer’ studies for children and young people with COVID-19, paediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporally associative with COVID-19 (PIMS-TS) or multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) included in meta-analyses, grouped by region of origin

Data Source: / if extracted from paper; * if individual patient data shared, ** if individual patient data shared and includes unpublished data due to ongoing data collection, $ if individual patient data extracted from paper, @ if aggregate data shared by authors. Admission to critical care - CC, Required mechanical invasive ventilation - mIV, Required cardiovascular support - CVS. Systematic Review - SR. uk - unknown.

| Study |

Population |

Exposure | Risk Factors used in MA | Outcomes used in MA | Comparator Group(s) | CC n(%) | Death n(%) | Data Source | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, Date, Country | Study Design | No of admitted children | Inclusion and Exclusion criteria | Criteria for diagnosis | ||||||

| Asia | ||||||||||

| COVID-19 | ||||||||||

| Du,36 May 2020, China | Retrospective Observational | 182 | <16 years Admitted |

RT-PCR pos | Age | mIV n = 3 Death n = 1 |

Allergic vs non-allergic patients Pneumonia vs no pneumonia |

uk | 1 (0.5%) | / |

| Qian,37 July 2020, China | Retrospective Observational | 127 | 1month - 16 years Patients admitted to hospital |

RT-PCR pos | Age, sex, comorbidity, coinfection | CC n = 7 Death n = 0 |

Critical Disease (admission to CC/need for mIV/CVS) - only admission to CC analysed. | 7 (5.5%) |

0 | / |

| Sung,38 July 2020, South Korea | National prospective registry | 101 | All ages collected, only children <19 years inc | RT-PCR pos | Age, sex, comorbidities | CC n = 0 mIV n = 0 Death n = 0 |

Comparison of disease severity | 0 | 0 | * |

| Alharbi,39 Dec 2020, Saudi Arabia | Retrospective Observational | 65 - C-19 6 - MIS-C |

<15 years Community and hospitalised |

RT-PCR pos MIS-C (CDC) |

Sex, comorbidity | CC n = 12 mIV n = 5 CVS n = 8 Death n = 3 |

Community vs hospitalised, hospitalised vs critical care | 12 (17%) |

3 (4%) |

/ |

| Bayesheva,40 Dec 2020, Kazakhstan | Retrospective Observational | 549 | <19 years | RT-PCR pos | Comorbidity, age, sex Obesity not defined |

CC n = 4 mIV n = 1 Death n = 0 |

Mild, moderate and severe disease | 4 (0.7%) |

0 | * |

| Qian,41 April 2021, China | Retrospective Observational | 127 | 1 month - 16 years | RT-PCR pos | Co-morbidities | Death | Mild, moderate, severe and critical | uk | 2 (1.6%) | / |

| PIMS-TS / MIS-C | ||||||||||

| Almoussa,42 Oct 2020, Saudi Arabia | Retrospective Observational |

10 | <14 years Admitted to hospital |

MIS-C (CDC) | Age, sex comorbidity | CC n = 9 mIV n = 1 CVS n = 5 Death n = 2 |

None | 9 (90%) |

2 (20%) |

$ |

| Jain,43 Aug 2020, India | Retrospective and prospective Observational |

23 | <15 years Hospitalised |

MIS-C (WHO) | Sex, age | mIV n = 9 CVS n = 15 Death n = 1 |

MIS-C with shock vs MIS-C without shock | uk | 1 (4%) |

* |

| Shahbaznejad,44 Oct 2020, Iran | Retrospective Observational | 10 | Patients admitted to hospital | PIMS-TS | Sex, Age | CC n = 9 mIV n = 3 CVS n = 4 Death n = 1 |

None | 9 (90%) |

1 (10%) |

$ |

| Hasan,45 Feb 2021, Qatar | Retrospective Observational | 7 | Patients admitted to hospital | MIS-C (WHO) | Sex, Age | CC n = 5 mIV n = 1 |

None | 5 (71%) |

uk | $ |

| Europe | ||||||||||

| COVID-19 | ||||||||||

| Armann,46 May 2020, Germany | Prospective Observational Registry | 102 | <20 years | RT-PCR pos | Age, sex, comorbidities Obesity not defined |

CC n = 15 mIV n = 6 CVS n = 8 Death n = 1 |

None | 15 (14%) |

1 (0.9%) |

* |

| Bellino,47 July 2020, Italy | Routine surveillance system | 511 | <18 years Admitted |

RT-PCR pos | Age, sex, comorbidity | CC n = 18 Death n = 4 |

Outcomes compared by age. Multivariable logistic regression comparing predictor variables and outcomes | 18 (6%) |

4 (0.8%) |

/ |

| Giacomet,48 Oct 2020, Italy | Retrospective Observational | 127 | <18 years Admitted |

RT-PCR pos | Sex, comorbidity, ethnicity Obesity not defined |

CC n = 8 mIV, n = 1 |

Asymptomatic, mild or moderate vs severe or critical. Admission to ICU/no ICU. | 8 (6%) |

0 | * |

| Gazzarino,49 May 2020, Italy | Retrospective Observational | 168 | 1 day - <18 years Admitted |

RT-PCR pos | Age | mIV n = 2 | None | uk | uk | / |

| Ceano-Vivas,50 May 2020, Spain | Retrospective Observational | 33 | <18 years Presenting to hospital |

RT-PCR pos | Sex, comorbidity, age Obesity: not defined |

CC n = 5 mIV n = 1 CVS n = 1 Death n = 1 |

Admission to hospital | 5 (15%) |

1 (3%) |

* |

| Storch de Gracia,51 Oct 2020, Spain | Retrospective Observational | 39 | < 18 years requiring hospital admission. Includes patients with MIS-C. Exclusion: pre-existing oncological disease, incidental or nosocomial SARS-CoV-2 |

RT-PCR pos or IgG antibodies | Age | CC n = 14 | Uncomplicated vs complicated (fluids or vasopressors, high flow nasal cannulae / non-invasive ventilation / invasive ventilation, encephalopathy). | 14 (36%) |

uk | / |

| M Korkmaz,52 June 2020, Turkey | Retrospective Observational | 44 | <18 years All patients attending ED |

RT-PCR pos | Age | CC n = 2 | Admission to hospital vs discharge from ED, ≤5 years, >5 years |

2 (5%) |

uk | / |

| Yayla,53 March 2021, Turkey | Retrospective Observational | 77 | <18 years Admitted |

RT-PCR pos or antibodies | Comorbidity | CC n = 1 mIV n = 1 CVS n = 1 Death n = 1 |

Asymptomatic, mild, moderate, critical/severe | 1 (1%) |

1 (1%) |

/ |

| O Swann,10 Aug 2020, UK | Prospective Observational | 579 | < 19 years Admitted to hospital. (Patients with MIS-C were excluded from SR) |

RT-PCR pos | Age, sex, comorbidities Obesity not defined |

CC n = 78 Death n = 6 |

Admission to critical care, in-hospital mortality. Details about patients with MIS-C could not be extracted and were excluded. |

78 (13%) |

6 (1%) |

/ |

| Gotzinger,11 June 2020, Europe | Retrospective and prospective Observational | 582 | <19 years Admitted and community |

RT-PCR pos | Sex, comorbidity, age Obesity not defined |

CC n = 48 mIV n = 25 CVS n = 19 Death n = 4 |

Admission to CC / no CC | 48 (8.2%) | 4 (0.7%) |

@ |

| Moraleda,54 July 2020, Spain | Retrospective Observational | 31 | <18 years Admitted to hospital |

RT-PCR, IgM or IgG positive or clinical MIS-C | Comorbidities | Death n = 1 | None | 20 (65%) |

1 (3%) |

/ |

| PIMS-TS / MIS-C | ||||||||||

| Whittaker,7 June 2020, UK | Retrospective Observational | 58 | Patients admitted to hospital <18 years |

PIMS-TS | Sex, comorbidity | CC n = 32 mIV n = 26 CVS n = 27 Death n = 1 |

Comparison with other childhood inflammatory disorders | 32 (55%) |

1 (1.7%) |

@ |

| Pang,55 UK | Retrospective selected cohort | 5 | Patients admitted to hospital <16 years |

PIMS-TS | Sex, age, comorbidity, race | CC n = 4 mIV n = 4 |

Viral polymorphisms in admitted patients with and without PIMS-TS compared to community SARS-CoV-2 individuals | 4 (80%) |

4 (80%) |

$ |

| Carbajal,56 Nov 2020, France | Retrospective Observational | 7 | Hospitalised <18 years |

MIS-C (CDC) | Sex, age | CC n = 7 mIV n = 3 CVS n = 5 Death n = 0 |

Kawasaki disease compared to MIS-C Comparison of MIS-C (CDC) vs MIS-C (WHO) vs PIMS-TS |

7 (100%) |

0 |

$ |

| Alkan,57 March 2021, Turkey | Retrospective Observational | 36 | Hospitalised <18 years |

MIS-C (CDC) |

Age | CC | Mild, moderate and severe MIS-C | 4 (11%) |

0 | / |

| Africa | ||||||||||

| COVID-19 | ||||||||||

| van der Zalm,58 Nov 2020, South Africa | Retrospective Observational | 62 | <13 years Exclusion: MIS-C |

RT-PCR pos | Age | CC n = 11 mIV n = 4 Death n = 1 |

Outcomes compared based on age | 11 (18%) |

1 (1.6%) |

/ |

| North America | ||||||||||

| COVID-19 | ||||||||||

| CDC,59 April 2020, USA | Voluntary national reporting | 147 | <18 years | RT-PCR pos | Age | CC n = 15 | Comparison with adults | 15 (10%) |

uk | / |

| Chao,60 Aug 2020, USA | Retrospective Observational | 46 | 1 month - <22 years Admitted |

RT-PCR pos | Sex, comorbidity Obesity: BMI >30 kg/m2 |

CC n = 13 | Admission to critical care | 13 (28%) |

uk | / |

| Desai,61 Dec 2020, USA | Retrospective Observational | 293 | <18 years Presenting to hospital |

RT-PCR pos | Sex, comorbidity | mIV n = 27 | Admission to hospital Admission to critical care |

28 (9.5%) |

Uk | / |

| Fisler,62 Dec 2020, USA | Retrospective Observational | 77 | <21 years Admitted |

RT-PCR pos | Sex, comorbidity Obesity: BMI ≥95th percentile |

CC n = 30 | Admission to critical care | 30 (39%) |

1 (1.2%) |

/ |

| Kainth,63 July 2020, USA | Retrospective Observational | 65 | <22 years Admitted Symptomatic |

RT-PCR pos | Sex, age, comorbidity | CC n = 23 | Subcategories of healthy infants, healthy children, immunocompromised children, chronically ill children and mild, moderate or severe disease. | 23 (35%) |

1 (1.5%) |

/ |

| Marcello,64 Dec 2020, USA | Retrospective Observational | 32 | All ages included, data provided on children < 19 years | RT-PCR pos | Sex, comorbidity | Death n = 1 | Hospitalisation and death | uk | 1 (3.1%) |

* |

| Kim,65 Aug 2020, USA | Population surveillance database | 208 (completed data) | <18 years Hospitalised |

RT-PCR pos | Age | CC n = 69 mIV n = 12 CVS n = 10 Death n = 1 |

Outcomes compared by age. | 69 (33%) |

1 (0.5%) |

/ |

| Moreira,13 Jan 2021, USA | Routinely collected data | 445 | All data complete <20 years All patients attending ED |

RT-PCR pos | Age (0–9 years, 10–19 years), Gender, Race & ethnicity, comorbidity | CC n = 69 Death n = 12 |

Admission to hospital vs discharge from ED, Death | 69 (16%) |

12 (2.7%) |

* |

| Richardson,66 April 2020, USA | Prospective Observational | 110 | Patients admitted to hospital No age restriction (patients included <19 years) |

RT-PCR pos | Sex, comorbidities, Age, Race | CC n = 37 mIV n = 14 CVS n = 0 Death n = 1 |

Survival vs death | 37 (34%) |

1 (0.9%) |

* |

| Verma,67 Jan 2021, USA | Retrospective Observational | 82 | <22 years Admitted |

RT-PCR pos | Age, comorbidity Obesity: BMI ≥30 or ≥95th percentile |

CC n = 23 mIV n = 7 Death n = 0 |

Admission to critical care | 23 (28%) |

0 | / |

| Zachariah,68 June 2020, USA | Retrospective Observational | 50 | <22 years Admitted |

RT-PCR pos | Sex, comorbidity | mIV n = 9 | Non-severe vs severe | uk | uk | / |

| Graff,69 April 2021, USA | Retrospective Observational | 85 | <21 years, all patients (admitted only in MA) | RT-PCR pos | Age, sex, race, comorbidity Obesity: BMI ≥95th percentile |

CC n = 11 | Non-severe vs severe | 11 (13%) |

1 (1.2%) |

/ |

| Preston,70 April 2021, USA | Routinely collected data | 2430 | <19 years, all patients (admitted only in MA) | Coded discharge with COVID-19 | Age, sex, race, comorbidity | CC n = 747 mIV n = 172 |

Non-severe vs severe | 747 (31%) |

uk | / |

| PIMS-TS / MIS-C | ||||||||||

| Abdel-Haq,71 Jan 2021, USA | Retrospective Observational | 33 | <18 years Hospitalised |

MIS-C (CDC) | Comorbidity Obesity not defined |

CC n = 22 | Admission to critical care | 22 (67%) |

Uk | / |

| Capone,72 June 2020, USA | Retrospective Observational | 33 | Hospitalised <18 years |

MIS-C (CDC) | Sex | Death n = 0 | None | 26 (79%) |

0 | / |

| Crawford,73 Feb 2021, USA | Retrospective Observational | 5 | <19 years Hospitalised |

MIS-C (CDC) | Sex, comorbidity, age Obesity not defined |

CC n = 4 mIV n = 0 CVS n = 5 Death n = 0 |

None | 4 (80%) |

0 | $ |

| Dufort,74 June 2020, USA | Emergency state reporting system | 99 | <21 years Hospitalised |

MIS-C (NYSDOH) | Age | CC n = 79 mIV n = 10 CVS n = 61 Death n = 2 |

Clinical features and outcomes compared by age | 79 (80%) |

2 (2%) |

/ |

| Riollano-Cruz,75 USA | Retrospective Observational | 15 | Patients admitted to hospital <21 years |

MIS-C (CDC) | Sex, comorbidity, age, Race | CC n = 1 mIV,n = 3 CVS n = 1 Death n = 1 |

None | 1 (6.7%) |

1 (6.7%) |

* |

| Rekhtman,76 Feb 2021, USA | Prospective Observational | 19 | Hospitalised <16 years |

MIS-C (CDC) | Age, race, sex | CC n = 12 mIV n = 5 Death n = 1 |

COVID-19 cohort compared to MIS-C cohort (with and without mucocutaneous disease) | 12 (63%) |

1 (5.3%) |

* |

| Belay,77 April 2021, USA | Standardised reporting and retrospective Observational | 1816 | Hospitalised <21 years | MIS-C (CDC) | Age | CC n = 1009 Death n = 24 |

Outcomes compared based on age | 1009 (56%) |

24 (1.3%) |

/ |

| Abrams,78 May 2021, USA | Retrospective Observational | 1080 | Hospitilised <22 years |

MIS-C (CDC) |

Sex, comorbidity, Age, Race Obesity either documented by physician or BMI ≥95th percentile for age and sex |

CC | Admission to ICU vs no ICU | 648 (60%) |

18 (2%) |

/ |

| South America | ||||||||||

| COVID-19 | ||||||||||

| OY Antunez-Montes,12 Jan 2021, Latin America | Prospective Observational | 96 - C-19 67 - MIS-C |

≤18 years All patients attending ED |

RT-PCR pos MIS-C (CDC) |

Sex, comorbidity, age, socioeconomic status, viral co-infections | CC n = 43 mIV n = 23 Death n = 16 |

Admission to hospital, admission to PICU | 43 (26%) |

16 (10%) |

/ |

| Araujo da Silva,79 Jan 2021, Brazil | Retrospective Observational | 50 - C-19 14 - MIS-C |

Patients admitted to hospital. Clinical symptoms consistent with COVID-19. |

RT-PCR pos MIS-C (WHO) |

Age, gender, comorbidity Obesity not defined |

CC n = 38 | Predominant vs non-predominant respiratory symptoms | 38 (59%) |

1 (1.6%) |

* |

| Sousa,22 Oct 2020, Brazil | Routinely collected dataset | 6948 | <20 years, admission to hospital, Severe acute respiratory infection symptoms |

RT-PCR pos | Sex, comorbidities, Age Obesity not defined |

CC n = 1867 mIV n = 755 Death n = 564 |

Outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 with other viral illnesses including influenza. | 1867 (27%) |

564 (8.1%) |

** |

| Hillesheim,80 Oct 2020, Brazil | Prospective reporting to national surveillance system | 6989 | <20 years Admitted Excluded if incomplete information |

Age, ethnicity, sex | mIV n = 610 Death n = 661 |

Survival vs death | 610 (8.7%) |

661 (9.5%) |

/ | |

| Bolanos-Almeida,81 Jan 2021, Colombia | Retrospective Observational | 597 | <18 years | RT-PCR pos | Age, Sex | CC n = 17 Death n = 5 |

Mild, moderate and severe disease and death | 17 (2.8%) |

5 (0.8%) |

* |

| Cairoli,82 Aug 2020, Argentina | Retrospective Observational | 578 | <21 years | RT-PCR pos | Age, sex, comorbidity Obesity: not defined |

CC n = 3 mIV n = 1 CVS n = 3 Death n = 1 |

None | 3 (0.5%) |

1 (0.2%) |

* |

| Sena,83 Feb 2021, Brazil | National Registry | 315 | <20 years | RT-PCR pos | Age | Death n = 38 | Outcomes compared by age and co-morbidity (hospitalised and community). | uk | 38 (5.6%) |

/ |

| PIMS-TS / MIS-C | ||||||||||

| Torres,84 Aug 2020, Chile | Retrospective and prospective Observational |

27 | Patients admitted to hospital <15 years |

MIS-C (CDC) | Sex | CC n = 16 | Ward vs critical care admission | 16 (59%) |

0 | / |

| Luna-Muñoz, 2021, Peru | Retrospective Observational | 10 | <13 years Hospitalised |

MIS-C (CDC) | Age, Sex, co-morbidity | mIV n = 3 Death n = 0 |

None | uk | 0 | / |

| Clark,85 Sept 2020, Global | Retrospective Observational | 55 | <19 years Hospitalised |

MIS-C (WHO) | Age, ethnicity | CC n = 27 | Comparison of cardiac abnormalities | 27 (49%) |

2 (3.6%) |

$ |

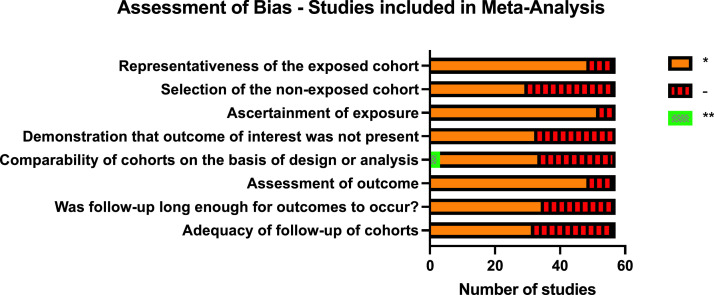

Data from 22 studies (40% of those in the meta-analysis) was included in the IPD meta-analyses, totalling 10,022 children. 26 studies reporting individual co-morbidities were eligible for inclusion in the narrative synthesis. Most studies eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis were at considerable risk of bias (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Risk of Bias assessment for studies included in meta-analysis. Representativeness of the exposed cohort: * indicates truly or somewhat representative of exposed cohort. Selection of non-exposed cohort: * indicates drawn from same community as the exposed cohort. Ascertainment of exposure: * indicates taken from secure record or structured interview. Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of the study: * indicates yes. Comparability of cohorts * if the study controls for one factor and ** if it controls for two factors in analysis. Assessment of outcome: * if independently blinded assessment of outcome or using record linkage. Was follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur: * indicates all included patients were followed-up until discharge from hospital. Adequacy of follow-up: * if description of patients who were not followed up.

We discuss findings from the aggregate and IPD meta-analyses for each set of risk factors and clinical outcomes below. Detailed data from included studies and pooled estimates from the aggregate meta-analyses are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Supplementary Figures 1 and 2 show the sensitivity analysis with the largest study excluded. A two-stage meta-analysis using study-level estimates calculated from the IPD data is shown in supplementary Figures 3 and 4.

Proportions of hospitalised children with COVID-19 admitted to critical care and who died in the aggregate analysis were 21.8% and 5.9% respectively and for PIMS-TS/MIS-C were 60.4% and 5.2%. In the IPD analysis, the proportion admitted to critical care with COVID-19 was 16.5% (6.7, 26.3) with death reported in 2.1% (−0.1, 4.3). For PIMS-TS/MIS-C, 72.6% (54.4, 90.7) were admitted to critical care and 7.41% (4.0, 10.8) died.

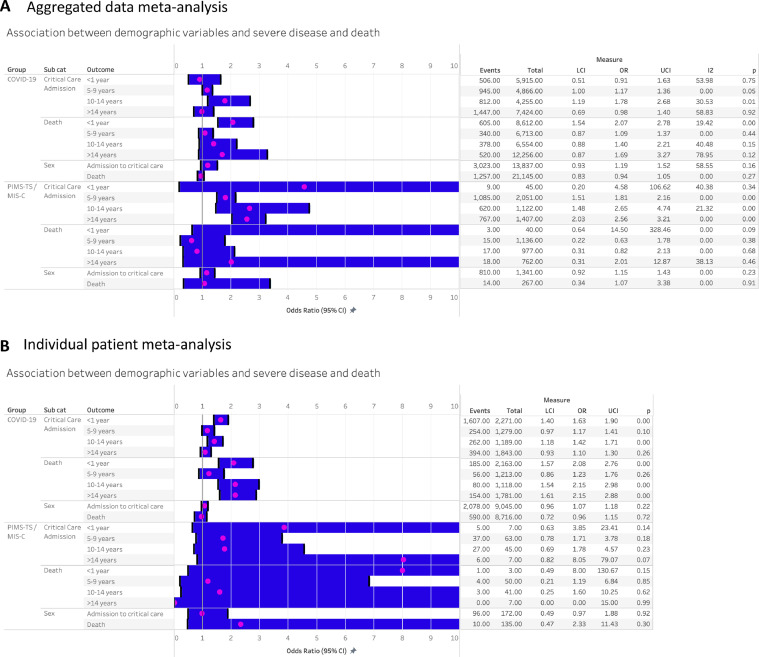

Demographic risk factors for admission to critical care and death

Sex was not associated with pooled risk of admission to critical care or death in either COVID-19 or PIMS-TS in either the aggregate or IPD analyses (Figure 3A and B). Compared with 1–4 year olds, the aggregate analysis found a higher pooled risk of critical care admission amongst 10–14 year olds and a higher risk of death amongst infants (children aged < 1 year) for COVID-19. In contrast, the IPD analysis found higher risk of critical care and death amongst both infants and 10–14 year olds, plus a higher odds of death amongst those >14 years for COVID-19. For PIMS-TS/MIS-C, the aggregate analysis found higher odds of critical care admission in all age-groups over 5 years, but no age-effects on risk of death. Numbers in the IPD analysis for PIMS-TS/MIS-C were very small, with no association of age-group with risk of death or critical care admission.

Figure 3.

Association between demographic features and severe disease following SARS-CoV-2 infection in children. A: Aggregate meta-analysis. B: Individual patient data meta-analysis.

LCI- Lower confidence interval, UCI – upper confidence interval. Age ref group: 1–4 years. Sex ref group: female.

We were unable to assess the impact of ethnicity and socioeconomic position on clinical outcomes. The reporting of ethnicity data was highly variable and groupings were insufficiently similar across studies to allow meta-analysis. Socioeconomic position was reported by very few studies.

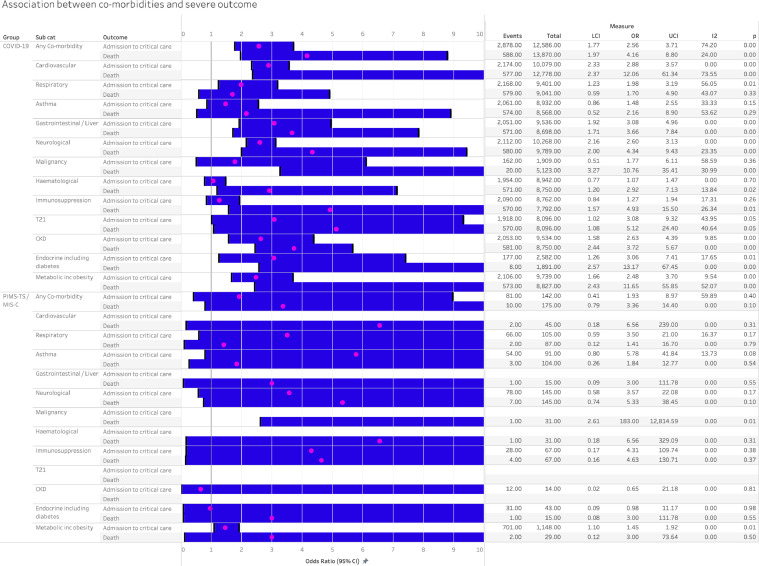

Association of co-morbidities and critical care and death in aggregate meta-analysis

The aggregate meta-analysis compared those with any or specific comorbidities with all other CYP in each study (Figure 4). The presence of any comorbidity increased odds of critical care and death in COVID-19, with pooled odds ratios of 2.56 (1.77, 3.71) for critical care and 4.16 (1.97, 8.80) for death, both with moderate to high heterogeneity. Pooled odds ratios for PIMS-TS/MIS-C were of a similar order but with wide confidence intervals (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Association between co-morbidity and severe disease in COVID-19 and PIMS-TS, analysed using aggregated extracted data from published studies. UCI- Upper confidence interval, LCI – lower confidence interval. P 0.00 indicates p<0.01.

Pooled odds of both critical care admission and death in COVID-19 were increased in CYP with the following co-morbidities: cardiovascular; gastrointestinal or hepatic; neurological; chronic kidney disease; endocrine conditions, including diabetes; and metabolic conditions, including obesity (Figure 4). Odds ratios for critical care ranged from 2.5 to 3.1 and for death from 2.9 to 13. The presence of asthma or trisomy 21 (Down's Syndrome) was not associated with either outcome, while respiratory conditions were associated with increased odds of critical care but not death. There was an increased odds of death but not of critical care admission in those with malignancy, haematological conditions and immunosuppression for non-malignant reasons.

Few individual comorbidities were associated with odds of critical care or death in PIMS-TS / MIS-C, with the exception of malignancy (OR for death 183 (2.61, 12,815) and metabolic diseases including obesity (OR for critical care 1.45 (1.10, 1.92)).

Association between co-morbidities and critical care and death in IPD meta-analysis

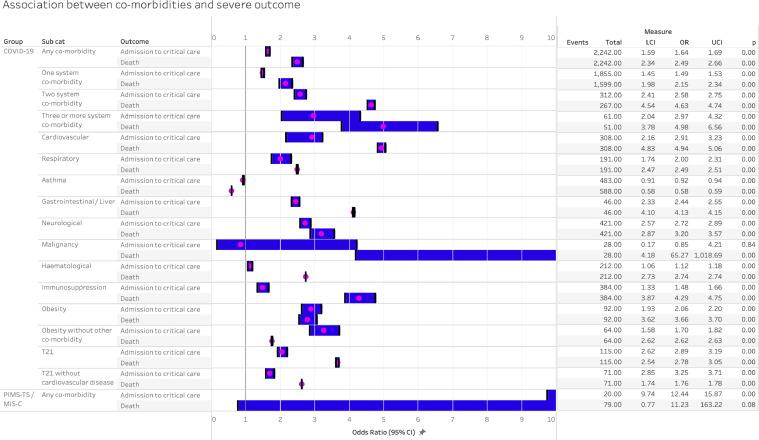

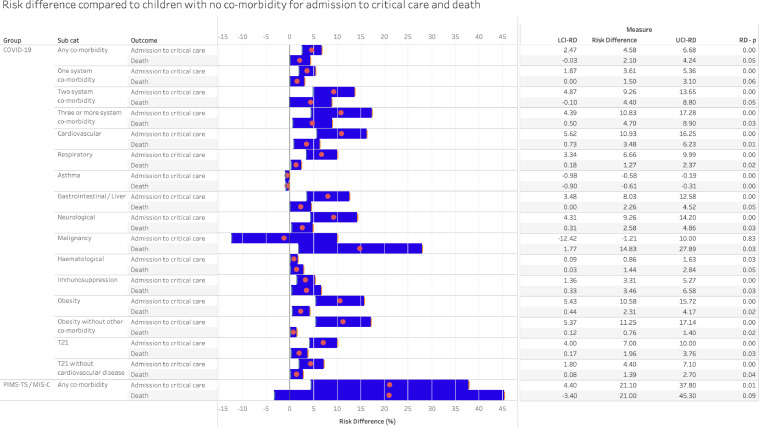

The IPD analysis compared those with each co-morbidity with children without any co-morbidity and additionally enabled analysis of risk associated with multiple comorbidities, obesity without other comorbidity, and trisomy 21 without cardiovascular disease. Figure 5 shows pooled OR for critical care and death for each comorbidity, and Figure 6 shows the risk difference estimated from the same models compared with children without comorbidities.

Figure 5.

Association between co-morbidity and severe disease in COVID-19 and PIMS-TS, analysed using individual patient data with adjustment for age and sex and clustered by study. LCI – lower confidence interval, UCI – upper confidence interval.

Figure 6.

The risk difference for developing severe disease in children with co-morbidities compared to children without co-morbidity, calculated using individual patient data corrected for age and sex. The absolute risk of critical care admission for COVID-19 in children admitted to hospital with no co-morbidity being admitted to critical care is 16.2% and of death is 1.69%. The risk of admission to critical care with paediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporally associated with COVID-19 (PIMS-TS) is 74.5% and the risk of death is 3.09%. LCI-RD – lower confidence interval of the risk difference. UCI-RD – lower confidence interval of the risk difference. RD-p – statistical significance of the risk difference compared to no co-morbidity.

In IPD analysis, the presence of any comorbidity increased odds of critical care and death in COVID-19. The pooled odds ratio for admission to critical care was 1.64 (1.59, 1.69), with risk difference being 4.6% (2.5, 6.7) greater than the 16.2% prevalence of critical care admission in those without comorbidities. The pooled odds of death from COVID-19 in those with any comorbidity was 2.49 (2.34, 2.66), with a risk difference of 2.1% (−0.03, 4.2) above the 1.69% risk in those without comorbidity. For PIMS-TS/MIS-C, pooled odds of critical care was 12.44 (9.74–15.87) and risk difference 21.1% (4.4, 37.8) above baseline risk of 74.5%, and pooled odds of death was 11.23 (0.77, 163.22) with risk difference 21.0% (−3.4, 45.3) above baseline risk of death of 3.1%.

Increasing numbers of comorbidities increased the odds of critical care and death in COVID-19, with those with ≥3 comorbidities having a odds ratio of death of 4.98 (3.78, 6.56), twice that of the odds with one comorbidity. Small numbers with PIMS-TS / MIS-C meant that further analysis of co-morbidities could not be undertaken.

All individual comorbidities increased odds of admission to critical care except for malignancy and asthma, the latter associated with reduced odds (0.92 (0.91, 0.94). Risk differences for critical care above the risk for the no comorbidities group were highest for cardiovascular, neurological, and gastrointestinal conditions, as well as for obesity. Obesity alone, without other conditions, increased risk difference to the same level as cardiovascular or neurological conditions, although numbers were small in the obesity analyses.

Odds of death in COVID-19 in the IPD analyses was elevated in all comorbidity groups except for asthma, where there was a reduced risk (−0.6% (−0.9, −0.3)). Risk difference additional to the no comorbidity group was highest for malignancy. Trisomy 21 increased risk of death in those with or without comorbid cardiovascular disease.

Narrative findings from studies of specific comorbidities

Twenty-six papers met the inclusion criteria for the narrative synthesis (Table 2), all reporting on the association of co-morbidity with acute COVID-19. Malignancy was the focus of sixteen of the studies, with rates of critical care admission in hospitalised patients ranging from 0 to 45% and of death in 0–47%. Six of the ten studies reporting deaths in this group of patients noted that some or all of the reported deaths were due to the underlying condition rather than SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Table 2.

Study characteristics of comorbidity studies for CYP with COVID-19 and PIMS-TS or MIS-C. Admission to critical care - CC.

| Study |

Population |

Exposure | Comparator Group(s) | CC n(%) | Deathn(%) | Other | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, Date, Country | Study Design | No of admitted children | Inclusion and Exclusion criteria | Criteria for diagnosis | ||||

| Cystic Fibrosis | ||||||||

| COVID-19 | ||||||||

| Bain,86 Dec 2020, Europe | Retrospective and prospective registry | 24 | <18 years | RT-PCR pos or clinical diagnosis | None | 1 (4.2%) |

0 | |

| Heart Disease | ||||||||

| COVID-19 | ||||||||

| Simpson,87 July 2020, USA | Case Series | 7 | <20 years | RT-PCR pos | None | 3 (43%) |

1 (14%) |

Atrioventricular Septal Defect (AVSD) (n = 2) Anomalous left coronary artery from pulmonary artery (n = 1) Tetralogy of fallot (n = 1) Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (n = 1) Dilated cardiomyopathy (n = 1) Cardiac transplant (n = 1) Comorbidities: Trisomy 21 (n = 3), Obesity (n = 2), Diabetes (n = 1), Chronic Kidney Disease (n = 1), Asthma (n = 1) |

| Esmaeeli,88 April 2021, Iran | Case Series | 7 | <19 years Hospitalised |

RT-PCR pos | None | 5 (71%) |

2 (29%) |

Hypoplastic Left Heart (n = 1) Truncus Arteriosus (n = 1) Aortic Regurgitation (n = 1) Ventricular Septal Defect (n = 1) AVSD (n = 1) Pulmonary Atresia (n = 1) Unknown (n = 1) |

| Cancer +/- stem cell transplant | ||||||||

| COVID-19 | ||||||||

| Bisogno,89 July 2020, Italy | Retrospective and prospective case series | 15 | <18 years | RT-PCR pos | None | 0 | 0 | |

| De Rojas,90 April 2020, Spain | Retrospective case series | 11 | <19 years | RT-PCR pos | None | 0 | 0 | Leukaemia (n = 8) Lymphoma (n = 1) Bone / soft tissue (n = 1) Solid organ (n = 1) |

| Ebeid,91 Dec 2020, Egypt | Prospective observational study | 15 | u/k | RT-PCR pos | None | 0 | 2 (13%) |

Leukaemia (n = 12) Lymphoma (n = 1) Other (n = 2) 5 symptomatic, 10 asymptomatic Deaths not due to COVID-19 |

| Ferrari,92 April 2020, Italy | Retrospective and prospective case series | 21 | <18 years | RT-PCR pos | None | u/k | 0 | Leukaemia (n = 10) Lymphoma (n = 2) Other (n = 9) |

| Gampel,93 June 2020, USA | Retrospective observational study | 11 | <18 years | RT-PCR pos | None | 5 (45%) |

0 |

Inpatient and outpatient Leukaemia/Lymphoma (n = 6) Solid Tumour (n = 8) Haematological diagnosis (n = 3) Hematopoietic stem cell transplant (n = 2) |

| Millen,94 Nov 2020, UK | Retrospective and prospective observational study | 40 | <16 years | RT-PCR pos | None | 3 (8%) |

1 (3%) |

Inpatient and outpatient Leukaemia (n = 28) Lymphoma (n = 2) Soft tissue tumour (n = 4) Solid organ tumour (n = 10) CNS tumour (n = 5) Other (n = 5) 11/40 (28%) nosocomial infection Death not due to COVID-19 |

| Montoya,35 July 2020, Peru | Case Series | 33 | <17 years | RT-PCR pos | None | 3 (9%) |

7 (21%) |

Inpatient and outpatient Leukaemia (n = 39) Lymphoma (n = 5) CNS tumour (n = 5) Other (n = 27) 20/33 (61%) due to nosocomial infection 4/7 (57%) deaths not due to COVID-19 |

| Palomo Colli,95 Dec 2020, Mexico | Case Series | 30 | <18 years | RT-PCR pos | None | 2 (7%) |

3 (10%) |

Inpatient and Outpatient Leukaemia (n = 24) Other (n = 14) All deaths due to underlying condition |

| Radhakrishna,96 Sept 2020, India | Case Series | 16 | <18 years | RT-PCR pos | None | 1 (6%) |

0 | Leukaemia (n = 12) Other (n = 3) 15/16 (94%) nosocominal infections |

| Sanchez-Jara,97 Nov 2020, Mexico | Retrospective observational study | 15 | <16 years | RT-PCR pos | None | u/k | 7 (47%) |

Leukaemia (n = 15) |

| Madhusoodhan,98 April 2020, USA | Retrospective cohort study | 28 | <22 years | RT-PCR pos | None | u/k | 4 (14%) |

Inpatient and Outpatient Leukaemia (n = 61) Lymphoma (n = 3) Other (n = 34) No deaths solely due to COVID-19 |

| Kebudi,99 Jan 2021, Turkey | Retrospective cross-sectional study | 38 | <18 years | RT-PCR pos | None | 9 (24%) |

1 (3%) |

Inpatient and Outpatient Leukaemia (n = 26) Lymphoma (n = 5) Other (n = 20) No deaths solely due to COVID-19 |

| Lima,100 Nov 2020, Brazil | Retrospective cohort study | 35 | <19 years | RT-PCR pos | None | 10 (29%) |

8 (23%) |

5 deaths within 30 days, 8 within 60 days |

| Fonseca,101 Feb 2021, Colombia | Observational retrospective study | 33 | <18 years | RT-PCR pos | Comparison of diagnoses and admission to CC | 7 (21%) |

5 (15%) |

2 deaths due to COVID-19 Leukaemia (n = 14, 5 admitted CC) Lymphoma (n = 4, 1 admitted CC) Other (n = 9, 1 admitted CC) |

| Vincet,102 June 2020, Spain | Retrospective case series | 5 | <13 years | RT-PCR pos | None | 2 (40%) |

1 (20%) |

3/5 (60%) nosocomial infections |

| Haematological | ||||||||

| COVID-19 | ||||||||

| Arlet,103 June 2020, France | Prospective case series | 12 | <15 years | RT-PCR pos | Compared by age | 2 (17%) |

0 | Sickle Cell Disease |

| Telfer,104 Nov 2020, England | Prospective case series | 10 | <20 years | RT-PCR pos | Compared by age | uk | 1 (10%) |

Sickle Cell Disease |

| Immunosuppression | ||||||||

| COVID-19 | ||||||||

| Dannan,105 Oct 2020, United Arab Emirates | Case Series | 5 | <13 years | RT-PCR pos | None | 0 | 0 | Common Variable Immunodeficiency (n = 1) Chemotherapy (n = 1) Pyruvate kinase deficiency and splenectomy (n = 1) Nephrotic Syndrome on Prednisione (n = 1) Systemic Lupus Erythematosus on Prednisiolone and Mycofenolate (n = 1) |

| Perez-Martinez,106 August 2020, Spain | Retrospective case series | 5 | <15 years | RT-PCR pos | None | 0 | 0 | Hematopoietic stem cell transplant (n = 1) Leukaemia (n = 1) Liver Transplant (n = 1) Kidney Transplant (n = 1) C-ANCA vasculitis (n = 1) |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | ||||||||

| COVID-19 | ||||||||

| Melgosa,107 May 2020, Spain | Retrospective case series | 8 | <18 years | RT-PCR pos | None | 0 | 0 |

Inpatient and Outpatient Renal Dysplasia (n = 5) Nephrotic Syndrome (n = 5) Uropathy (n = 2) Other (n = 4) |

| Malaris,108 Nov 2020, Global | Retrospective and prospective observational study | 68 | <20 years Under Paediatric Services CKD on immunosuppression |

RT-PCR pos | None | 6 (9%) |

4 (6%) |

Inpatient and Outpatient Kidney transplantation (n = 53) Nephrotic Syndrome (n = 30) Other (n = 30) |

| Rheumatic Diseases | ||||||||

| COVID-19 | ||||||||

| Villacis-Nunez,109 Jan 2021, USA | Retrospective case series | 8 | <22 years | RT-PCR pos | Need for hospitalisation | 3 (38%) |

0 | Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (n = 1) Systemic Lupus Erythematosis (n = 5) Other (n = 2) |

| Liver Disease and transplant | ||||||||

| COVID-19 | ||||||||

| Kehar,110 Feb 2021, International | Retrospective observational study | 21 | Community and hospitalised <21 years |

RT-PCR or antibody | Native liver disease vs liver transplant recipient | 2 (9.5%) |

1 (4.2%) |

Native liver disease (n = 44) Liver transplant recipient (n = 47) |

Two studies focussed on hospitalised patients with sickle cell disease. There were fewer than fifteen patients in each study, with 17% of patients being admitted to critical care in one study and reported deaths in 0–10%. Two studies looking at non-malignant immunosuppression described no children requiring critical care admission or death and a study of children with Rheumatic diseases found a rate of critical care admission of 38%.

Chronic kidney disease was examined in two studies with small numbers of hospitalised patients, which describe a rate of critical care admission between 0 and 9% and of death between 0 and 6%. A study of CYP with cystic fibrosis found that 1 in 24 (4%) of those hospitalised were admitted to critical care and no deaths were described. Finally, two studies describe the association between pre-existing cardiac co-morbidity and outcome, which show a high proportion of children are admitted to critical care (43–71%) and that 14–29% are reported to die.

Discussion

We present the first individual patient meta-analysis of risk factors for severe disease and death in CYP hospitalised from both COVID-19 and PIMS-TS/MIS-C, nested within a broad systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies from the first pandemic year. Studies were of mixed quality and most were open to substantial bias; yet our meta-analyses included data from 57 studies from 19 countries, including 8 low or middle-income countries (LMIC).

Across both the aggregate and IPD analyses, no association was found between sex and odds of severe disease or death for either COVID-19 or PIMS-TS/MIS-C. The odds of poor outcomes was 1.6 to 2-fold higher for infants than 1–4 year olds for COVID-19 alone, but teenagers had elevated odds of severe COVID-19 (1.4 to 2.2-fold higher odds) and particularly PIMS-TS/MIS-C (2.5 to 8-fold greater odds).

The presence of underlying comorbid conditions had the strongest association between critical care admission and death. The presence of any comorbidity increased odds of severe COVID-19 for both the aggregate and IPD analyses (OR 2.56 (1.77, 3.71) and 1.64 (1.59, 1.69) respectively for critical care admission), increasing absolute risk of critical care admission by 4.5% (a relative increase of 28%) and risk of death by 2.5% (125% relative increase), with an even greater 21% increase in risk of death for PIMS-TS/MIS-C (6.8-fold increase in risk). Whilst one comorbidity increased absolute risk of critical care by 3.6% and death by 1.5% in COVID-19, 2 or more comorbidities dramatically increased the absolute risk.

All comorbidities were associated with increased risk across the two analyses, with the exception of asthma. Increase in odds of poor outcomes in COVID-19 was highest amongst those with cardiovascular, respiratory, neurological, and gastrointestinal comorbidities, each increasing absolute risk of critical care by 8–11% and risk of death by 1–3.5%. Malignancy was associated with increased risk of death from COVID-19, but not critical care admission in both analyses, which is counter-intuitive and raises the possibility that this reflects the high mortality rate amongst cancer survivors who may have died with incidental SARS-CoV-2 positivity. The aggregated analysis did not suggest increased risk in those with immunosuppression (outside malignancy) or with haematological conditions when compared to CYP without those comorbidities, but these groups were at increased risk of severe disease in the IPD analysis.

The associations identified for more severe COVID-19 are highly similar to those risk factors now well described for adults and described in a subsequently published large US study in children.23,24 This suggests that risk factors for severe COVID-19 are consistent across the life-course, but previously not well understood in CYP because of the rarity of severe disease. These findings relate to risk factors for severe disease rather than risk factors for infection, as only hospitalised CYP were included. It is likely that these findings may over-estimate risks of critical care and death for CYP in high income countries, as the mortality rate in these analyses (2.1% of children with COVID and 7.41% of those with PIMS-TS/MIS-C) are very much higher than national mortality rates reported from these settings.25, 26, 27 This likely reflects inclusion of studies from LMIC, publication bias towards more severe cases and potentially an increased likelihood of presentation to and admission to hospital or critical care in CYP with co-morbidities. Despite this, the additional absolute risks related to all comorbidities was small compared with those without comorbidities.

The finding of no difference of severity by sex is contrary to a large literature showing that males are more vulnerable to severe illness and death in childhood.28,29 Whilst male sex is a known risk factor for more severe COVID-19 in adults, this excess risk arises only after middle age.30 Obesity, whether alone or with other conditions, was found to markedly increased risk of critical care admission and death in the IPD analysis. Whilst numbers with obesity were very small, these findings are consistent with adult data showing obesity to be one of the strongest risk factors for severe disease in adults.31 The finding that CYP with trisomy 21 were at increased risk of critical care admission and death has not been described before, although it is consistent with previous adult data.32 This risk appears to operate both through and independently of cardiovascular anomalies, indicating that all CYP with trisomy 21 are at some increased risk of severe disease.

Previous reviews have not provided a systematic understanding of the associations of paediatric comorbidities and severe outcomes in CYP. Systematic reviews which were undertaken early in the pandemic highlighted some of the challenges around identifying comorbidities which were associated with severe disease, including pooled reporting of even common conditions such as asthma33 and a focus on individual comorbidities without a comparator group.34

The presented data are subject to a number of limitations. The risk of bias assessment demonstrates that the studies included within this systematic review are of low quality. Twenty-two of 57 studies (39%) provided individual patient data; systematic differences between these groups may have introduced bias. There were very small numbers with PIMS-TS/MIS-C in some analyses, particularly the IPD analyses. It was not possible to examine ethnicity and socioeconomic position as risk factors due to lack of data in included studies and further study is required to examine the impact of these variables on the severity of disease. The review was potentially limited by the ability to identify unpublished data and data in the grey literature.

Included studies were highly heterogenous and from a wide range of resource settings, and it is likely that findings were influenced by differing national approaches to hospitalisation of infected CYP and by differences in availability and use of resources including intensive care beds. Institutions undertaking systemic testing for SARS-CoV-2 on admission to hospital may include patients who were admitted for another reason and incidentally tested positive. A number of East Asian countries hospitalised all children who were SARS-CoV-2 positive, regardless of symptoms, whilst other countries limited hospitalisation to symptomatic children or those with significant illness. Policies on admission to and access to critical care likely also differed between countries.35 The novel nature of PIMS-TS/MIS-C also likely influenced critical care admission thresholds for this condition. Definitions of comorbidities were also heterogenous across studies and some of our comorbidity groups may be subject to misclassification bias. The definition of obesity in most studies related to severe or extreme obesity rather than the more common condition of being overweight, yet obesity was undefined in a number of studies.

The influence of variants on the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection has not been studied as the majority of data relate to the original virus and further work examining the impact of variants on the severity of disease in CYP is required.

It was not possible to separate the increased risk for severe disease related to comorbidities from the underlying risks of illness and death seen in these comorbidities in uninfected CYP, as all included cases had SARS-CoV-2. Case controlled studies are required to understand how rare congenital or acquired comorbidities may influence risk of severe disease or death from SARS-CoV-2 and enable better distinction between severe disease or death from SARS-CoV-2 and with SARS-CoV-2.

Whilst this review examined comorbidities as risk factors in more detail than previous studies, there were limited data on sub-types of comorbidities, e.g. whether neurological problems were epilepsy or more complex neurodisability, and on combinations of comorbidities. The finding that cardiovascular, neurological, and gastrointestinal conditions were associated with the highest risk of poor outcome, a risk similar to having 2 or more comorbidities, may reflect that these conditions were more likely to be comorbid with others. Given the low risk to CYP requiring hospital admission or critical care as a direct consequence of SARS-CoV-2 infection, it is likely that a significant number of reported cases were coincidental cases of SARS-CoV-2 positivity reflecting population prevalence. Furthermore, the impact of long COVID in CYP as an indicator of severe disease is not described in this manuscript.

When children are admitted to hospital with SARS-CoV-2 infection, those with the strongest association between critical care admission or death are infants, teenagers, those with cardiac or neurological conditions, or 2 or more comorbid conditions, and those who are significantly obese. These groups should be considered higher priority for vaccination and for protective shielding when appropriate. Whilst odd ratios for poor outcomes were increased for nearly all comorbidities, the absolute increase in risk for most comorbidities was small compared to CYP without underlying conditions. This emphasises that our findings should be understood within the broader context that risk of severe disease and death from COVID-19 and PIMS-TS/MIS-C in hospitalised CYP is very low compared with adults.

This study quantifies the additional risk related to comorbidities in infected children, however it is possible that some or all of this risk relates to the underlying condition rather than SARS-CoV-2 infection. Further population-based research using comparator groups which identify the risk of severe disease due to COVID-19 and the underlying risk due to comorbidity is required to develop a safe approach to vaccination for children.

Contributors

Study Design: RH, NT, CS, JW, C T-S, ML, MC, EW, PJD, KL, ESD, SK, LF and RMV, Literature search, identification of papers and data extraction: RH, HY, NT, CS, JW, SK and LF, Data analysis: RH, CT-S and RV, First Draft: RH, Review and editing: All authors

Funding

RH is in receipt of a fellowship from Kidney Research UK (grant no. TF_010_20171124). JW is in receipt of a Medical Research Council Fellowship (Grant No. MR/R00160X/1). LF is in receipt of funding from Martin House Children's Hospice (there is no specific grant number for this). RV is in receipt of a grant from the National Institute of Health Research to support this work (grant no NIHR202322). Funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

KL is the Programme Lead for the National Child Mortality Database. SK is the National Clinical Director for Children and Young People, NHS England and Improvement. ED is the Co-Principle Investigator for the Paediatric Intensive Care Audit Network.

Acknowledgments

Data sharing statement

Individual patient data will not be available to share, in-keeping with the data sharing agreement between authors providing data and the study team.

Acknowledgements

We thank the authors who shared patient level data to enable their inclusion in this study (Supplementary Information 1) and the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101287.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Davies N.G., Klepac P., Liu Y., Prem K., Jit M., group CC-w Age-dependent effects in the transmission and control of COVID-19 epidemics. Nat Med. 2020;26(8):1205–1211. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0962-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Molteni E., Sudre C.H., Canas L.S., et al. Illness duration and symptom profile in symptomatic UK school-aged children tested for SARS-CoV-2. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5(10):708–718. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00198-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Say D., Crawford N., McNab S., Wurzel D., Steer A., Tosif S. Post-acute COVID-19 outcomes in children with mild and asymptomatic disease. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5(6):e22–ee3. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00124-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Docherty A., Harrison E., Green C., et al. Features of 20133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;22(369):m1985. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhopal S.S., Bagaria J., Olabi B., Bhopal R. Children and young people remain at low risk of COVID-19 mortality. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5(5):e12–ee3. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00066-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith C., Odd D., Harwood R., et al. Deaths in children and young people in England after SARS-CoV-2 infection during the first pandemic year. Nat Med. 2022;28(1):185–192. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01578-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whittaker E., Bamford A., Kenny J., et al. Clinical characteristics of 58 children with a pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. 2020;324(3):259–269. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riollano-Cruz M., Akkoyun E., Briceno-Brito E., et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) related to COVID-19: a New York City experience. J Med Virol. 2021;93(1):424–433. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.RCPCH. Guidance: paediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporally associated with COVID-19 2020. Available from: https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-05/COVID-19-Paediatric-multisystem-%20inflammatory%20syndrome-20200501.pdf. [PubMed]

- 10.Swann O.V., Holden K.A., et al. Clinical characteristics of children and young people admitted to hospital with covid-19 in United Kingdom: prospective multicentre observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;370:m3249. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Götzinger F., Santiago-García B., Noguera-Julián A., et al. COVID-19 in children and adolescents in Europe: a multinational, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(9):653–661. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30177-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antunez-Montes O.Y., Escamilla M.I., Figueroa-Uribe A.F., et al. COVID-19 and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in Latin American Children: a multinational study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2021;40(1):e1–e6. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moreira A., Chorath K., Rajasekaran K., Burmeister F., Ahmed M., Moreira A. Demographic predictors of hospitalization and mortality in US children with COVID-19. Eur J Pediatr. 2021;180(5):1659–1663. doi: 10.1007/s00431-021-03955-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leeb R.T., Price S., Sliwa S., et al. COVID-19 trends among school-aged children - United States, March 1-September 19, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(39):1410–1415. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6939e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ludvigsson J.F. Systematic review of COVID-19 in children shows milder cases and a better prognosis than adults. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109(6):1088–1095. doi: 10.1111/apa.15270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel N.A. Pediatric COVID-19: systematic review of the literature. Am J Otolaryngol. 2020;41(5) doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stilwell P.A., Munro A.P.S., Basatemur E., Talawila Da Camara N., Harwood R., Roland D. Bibliography of published COVID-19 in children literature. Arch Dis Child. 2022;107(2):168–172. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2021-321751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Page M.J., Moher D., Bossuyt P.M., et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n160. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehta N.S., Mytton O.T., Mullins E.W.S., et al. SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19): what do we know about children? A systematic review. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2020;71(9):2469–2479. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wells G., editor Proceedings of the Third Symposium on Systematic Reviews beyond the Basics. Improving Quality and Impact; The Newcastle-Owwawa Scale for Assessing the Quality of non-randomised Studies in Meta-Analysis.2000; Oxford.

- 21.Collaboration TC. Review Manager. 5.4 ed 2020.

- 22.Sousa B.L.A., Sampaio-Carneiro M., de Carvalho W.B., Silva C.A., Ferraro A.A. Differences among severe cases of Sars-CoV-2, influenza, and other respiratory viral infections in pediatric patients: symptoms, outcomes and preexisting comorbidities. Clin (Sao Paulo) 2020;75:e2273. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2020/e2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williamson E.J., Walker A.J., Bhaskaran K., et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584(7821):430–436. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kompaniyets L., Agathis N.T., Nelson J.M., et al. Underlying medical conditions associated with severe COVID-19 illness among children. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhopal S.S., Bagaria J., Olabi B., Bhopal R. Children and young people remain at low risk of COVID-19 mortality. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5(5):e12–ee3. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00066-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leidman E., Duca L.M., Omura J.D., Proia K., Stephens J.W. Sauber-Schatz EK. COVID-19 trends among persons aged 0-24 Years - United States, March 1-December 12, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(3):88–94. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7003e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flood J., Shingleton J., Bennett E., et al. Paediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 (PIMS-TS): prospective, national surveillance, United Kingdom and Ireland, 2020. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;3 doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.PICANet. Paediatric intensive care audit network, annual report 2020. 2020.

- 29.NCMD. Second annual report, national child mortality database programme. 2021.

- 30.Ancochea J., Izquierdo J.L., Soriano J.B. Evidence of gender differences in the diagnosis and management of coronavirus disease 2019 patients: an analysis of electronic health records using natural language processing and machine learning. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2021;30(3):393–404. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2020.8721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yates T., Zaccardi F., Islam N., et al. Obesity, ethnicity, and risk of critical care, mechanical ventilation, and mortality in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: analysis of the ISARIC CCP-UK Cohort. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2021;29(7):1223–1230. doi: 10.1002/oby.23178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clift A.K., Coupland C.A.C., Keogh R.H., et al. Living risk prediction algorithm (QCOVID) for risk of hospital admission and mortality from coronavirus 19 in adults: national derivation and validation cohort study. BMJ. 2020;371:m3731. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Castro-Rodriguez J.A., Forno E. Asthma and COVID-19 in children: a systematic review and call for data. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020;55(9):2412–2418. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dorantes-Acosta E., Avila-Montiel D., Klunder-Klunder M., Juarez-Villegas L., Marquez-Gonzalez H. Survival in pediatric patients with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic: scoping systematic review. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2020;77(5):234–241. doi: 10.24875/BMHIM.20000174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montoya J., Ugaz C., Alarcon S., et al. COVID-19 in pediatric cancer patients in a resource-limited setting: national data from Peru. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;68(2):e28610. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Du H., Dong X., Zhang J.J., et al. Clinical characteristics of 182 pediatric COVID-19 patients with different severities and allergic status. Allergy. 2021;76(2):510–532. doi: 10.1111/all.14452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qian G., Zhang Y., Xu Y., et al. Reduced inflammatory responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection in children presenting to hospital with COVID-19 in China. medRxiv. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Sung H.K., Kim J.Y., Heo J., et al. Clinical course and outcomes of 3060 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Korea, January-May 2020. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(30):e280. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alharbi M., Kazzaz Y.M., Hameed T., et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in children, clinical characteristics, diagnostic findings and therapeutic interventions at a tertiary care center in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health. 2021;14(4):446–453. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bayesheva D., Boranbayeva R., Turdalina B., et al. COVID-19 in the paediatric population of Kazakhstan. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2021;41(1):76–82. doi: 10.1080/20469047.2020.1857101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qian G., Zhang Y., Xu Y., et al. Reduced inflammatory responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection in children presenting to hospital with COVID-19 in China. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;34 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Almoosa Z.A., Al Ameer H.H., AlKadhem S.M., Busaleh F., AlMuhanna F.A., Kattih O. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, the real disease of COVID-19 in pediatrics - a multicenter case series from Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2020;12(10):e11064. doi: 10.7759/cureus.11064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jain S., Sen S., Lakshmivenkateshiah S., et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children with COVID-19 in Mumbai, India. Indian Pediatr. 2020;57(11):1015–1019. doi: 10.1007/s13312-020-2026-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shahbaznejad L., Navaeifar M.R., Abbaskhanian A., Hosseinzadeh F., Rahimzadeh G., Rezai M.S. Clinical characteristics of 10 children with a pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome associated with COVID-19 in Iran. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20(1):513. doi: 10.1186/s12887-020-02415-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hasan M., Zubaidi K.A., Diab K., et al. COVID-19 related multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C): a case series from a tertiary care Pediatic hospital in Qatar. BMC Pediatr. 2020 doi: 10.1186/s12887-021-02743-8. In Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Armann J.P., Diffloth N., Simon A., et al. Hospital admission in children and adolescents with COVID-19. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;117(21):373–374. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2020.0373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bellino S., Punzo O., Rota M.C., et al. COVID-19 disease severity risk factors for pediatric patients in Italy. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4) doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-009399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giacomet V., Barcellini L., Stracuzzi M., et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms in severe COVID-19 children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39(10):e317–ee20. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garazzino S., Montagnani C., Dona D., et al. Multicentre Italian study of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and adolescents, preliminary data as at 10 April 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(18) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.18.2000600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.de Ceano-Vivas M., Martin-Espin I., Del Rosal T., et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in ambulatory and hospitalised Spanish children. Arch Dis Child. 2020;105(8):808–809. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Storch-de-Gracia P., Leoz-Gordillo I., Andina D., et al. Clinical spectrum and risk factors for complicated disease course in children admitted with SARS-CoV-2 infection. An Pediatr (Engl Ed) 2020;93(5):323–333. doi: 10.1016/j.anpede.2020.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Korkmaz M.F., Ture E., Dorum B.A., Kilic Z.B. The epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 81 children with COVID-19 in a pandemic hospital in Turkey: an observational cohort study. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(25):e236. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yayla B.C.C., Aykac K., Ozsurekci Y., Ceyhan M. Characteristics and management of children with COVID-19 in a tertiary care hospital in Turkey. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2021;60(3):170–177. doi: 10.1177/0009922820966306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moraleda C., Serna-Pascual M., Soriano-Arandes A., et al. Multi-inflammatory syndrome in children related to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in Spain. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(9):e397–e401. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pang J., Boshier F.A.T., Alders N., Dixon G., Breuer J. SARS-CoV-2 polymorphisms and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. Pediatrics. 2020;146(6) doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-019844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carbajal R., Lorrot M., Levy Y., et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children rose and fell with the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in France. Acta Paediatr. 2021;110(3):922–932. doi: 10.1111/apa.15667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alkan G., Sert A., Oz S.K.T., Emiroglu M., Yilmaz R. Clinical features and outcome of MIS-C patients: an experience from Central Anatolia. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40(10):4179–4189. doi: 10.1007/s10067-021-05754-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van der Zalm M.M., Lishman J., Verhagen L.M., et al. Clinical experience with SARS CoV-2 related illness in children - hospital experience in Cape Town, South Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(12):e938–e944. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Team CC-R Coronavirus disease 2019 in children - United States, February 12-April 2, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(14):422–426. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6914e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chao J.Y., Derespina K.R., Herold B.C., et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized and critically ill children and adolescents with coronavirus disease 2019 at a tertiary care medical center in New York City. J Pediatr. 2020;223 doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.006. 14-9 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]