Abstract

Introduction

Sexual harassment (SH) at the workplace is a globally discussed topic and one deserving of scrutiny. It is an issue that is often avoided although around 25% of nurses worldwide have experienced some form of SH at their workplace. Consequences of SH at workplaces can be very serious and an occupation hazard for nurses around the world. In Sub-Saharan Africa there is also a need for more studies in the field.

Objective

The overall aim was to determine the prevalence, types, and consequences of sexual harassment among nurses and nursing students at a regional university hospital in Tanzania.

Methods

The study has a cross-sectional design. A study specific questionnaire was distributed to a total of 200 nurses and nursing students. Descriptive statistics were used for calculation of frequencies, prevalence, including gender differences, types, and consequences of sexual harassment.

Results

The result show that 9.6% of the participants had experienced some form of SH at their workplace. Regarding the female nurses and students, 10.5% had been sexually harassed at work, whereas the number for males was 7.8%, but 36% knew about a friend who had been sexually harassed. The most common perpetrator were physicians. The victims of SH were uncomfortable going back to work, felt ashamed and angry.

Conclusions

In conclusion, nearly 10% of the participants had been exposed to sexual harassment. However, an even greater number of victims was found when including by proxy victims of sexual harassment. SH can become a serious occupational hazard and stigmatization for nurses. Enhanced knowledge is needed, and hospitals and medical colleges should emphasize their possibilities to give support and assistance to the victims of SH. Education about SH in all levels and prevention methods should also be emphasized.

Keywords: sexual harassment, stigmatization, clinical practice, nurses, students, nursing, Tanzania, sexual violence

Sexual harassment (SH) at the workplace is a widely discussed topic and one deserving of scrutiny. Although it is still an issue that is often avoided due to social stigma, in the autumn of 2017 it got an upswing in social media through the movement of #metoo. The movement has put an international spotlight on workplace sexual harassment. More than 12 million women from many countries across the world shared their experiences of SH and assault through social media (Agsi, 2018; Pasha-Robinson, 2017; Stop Street Harassment, 2018). However, since the 1970s, SH has long been under discussion among organizations representing international human rights, and in 2008 the United Nations stated that: “There is one universal truth, applicable to all countries, cultures and communities: violence against women is never acceptable, never excusable, never tolerable.” (United Nations Secretary-General, Ban Ki-/Moon, 2008 in García-Moreno et al., 2013). Sexual Harassment reduces the quality of working life, jeopardizes the well-being of the victims andundermines gender equality (African Development Bank Group, 2015; Gabay & Shafran Tikva, 2020; Hutagalung & Ishak, 2012; M. Kim et al., 2018; Nelson, 2018). Sexual harassment in hospital setting can also lead to missed out nursing care and thereby affect the patients (Gabay & Shafran Tikva, 2020; Nelson, 2018).

Definitions of Sexual Harassment

According to United Nation (1948), article 1,2 and 3, to feel safe, free and not discriminated upon, is a human right. However, for nurses, as well as for many other professional women and men across the world, this is not always a reality. Nurses and nursing student are since long time often victims of SH during workhours and the perpetrators can be either superiors, colleagues or patients (Bronner et al., 2003; M. Kim et al.,2018; S.-K. Lee et al., 2011; Nelson, 2018). There are several distinct definitions of SH at the workplace and the present study focuses on the one formulated by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2005):

Any unwelcome sexual advance, request for sexual favor, verbal or physical conduct or gesture of a sexual nature, or any other behavior of a sexual nature that might reasonably be expected or be perceived to cause offence or humiliation to another. Sexual harassment may occur when it interferes with work, is made a condition of employment, or creates an intimidating, hostile or offensive environment. It can include a one-off incident or a series of incidents. Sexual harassment may be deliberate, unsolicited, and coercive. Both male and female colleagues can either be the victim or offender. Sexual harassment may also occur outside the workplace and/or outside working hours. (p. 3)

The experience of SH is fundamentally subjective and coloured by the socio-economic and cultural context (gender stereotypes, hierarchies, norms, etc.) in which it takes place, and what different kinds of behaviour that are considered harassment seems to vary among different cultures (McCann, 2005). Luthar and Luthar (2002) state, in a study where Hofstede’s cultural dimensions to explain sexually harassing behaviours in an international context were used, that in cultures with a higher masculinity index women are likely to be more tolerant of sexually aggressive behaviours than women in lower masculinity index cultures. Further, are males in higher masculinity index cultures more likely to be more sexually aggressive in their behaviours, than males in cultures with lower masculinity index.

Since 2002, sexual harassment in employment has been prohibited in all member countries of EU (Numhauser-Henning & Laulom, 2012). Further, In Africa, Kenya, Namibia, South Africa, and Tanzania have prohibited sexual harassment at workplace (WHO, 2014). Several countries in both South America and Asia have also adapted legislation to prohibit SH (McCann, 2005). The parliament of the United Republic of Tanzania adopted a new law to further safeguard the personal integrity, dignity, liberty, and security of women 1998. Henceforth, sexual harassment is an illegal act, and the consequences can either be conviction to imprisonment or pay a fine (Parliament of the United Republic of Tanzania, 1998).

Sexual Harassment Workplaces and in Clinical Practice

Sexual harassment is found in workplaces all over the world and is a hazard both to the victims’ health (Gabay & Shafran Tikva, 2020; Hadi, 2017; Lamesoo, 2013; Somani et al., 2015; Tekin & Buluk, 2014) and the work environment (Luthar & Luthar, 2002; McCann, 2005). The nursing profession is female-dominated, and nurses have long experience of SH at work, and the problem persists in today's workplace (Gabay & Shafran Tikva, 2020; Nelson, 2018; Somani et al., 2015). A review by Kahsay et al. (2020) shows that the frequency of SH among nurses vary from 10 to 87.5% and that the most common perpetrators were patients, 46%. A study from Israel on nursing and SH shows that 75% of perpetrators were men sexually harassing female nurses and nursing students (Bronner et al., 2003). However, it does not impact on all women in the same way but has also been shown to be more directed towards the more vulnerable and economically dependent, such as young female workers (McCann, 2005). But a recent qualitative study from a hospital in Sri Lanka points out that SH was a perceived workplace concern for the nurses (Adams et al., 2019). Studies have also emphasized that nurses/nursing students are vulnerable to SH (Bronner et al., 2003; Gabay & Shafran Tikva, 2020, Lamesoo, 2013). Although women are the most common targets for sexual harassment, men can also be victims to SH, especially vulnerable groups such as “young men, gay men, members of ethnic or racial minorities, and men working in female-dominated work groups” (McCann, 2005). Despite an increase in male nurses and nursing studies, the nursing profession can still be seen as a feminine work due to its caretaking character and female nurses are more prone to be sexually harassed than male nurses (Bronner et al., 2003; Lamesoo, 2013; Somani et al., 2015; Spector et al., 2014).

In a report made by PesaCheck, East Africa’s first fact-checking organization (https://pesacheck.org/), it is stated that “Tanzania is one of the countries with the highest prevalence of sexual violence by non-partners after the age of 15 years” and that sexual-violence reports have increased between 2016 and 2017 (pesacheck.org, 2020-08-02). PesaCheck is a fact-checking initiative supported by International Budget Partnership and Code for Africa affiliates in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. The aim is to verify numbers quoted by public figures across East Africa, in order to help decision making (pesacheck.org, 2020-08-02. A study by Bangham (2016), about the efficacy of sexual health education in Tanzania, states that “structural forces and violence against women contribute to a lack of attention to sexual and reproductive health education”, leading to young women’s lack of knowledge of their rights to their bodies and self-determination. This reinforces the unequal power balance between men and women.

Globally, several studies on SH among nurses has been made and different results have been found in different geographical areas investigated. A quantitative review on nurses’ exposure to physical and nonphysical violence, bullying, and sexual harassment, made by Spector et al. (2014) showed that around 25% of nurses worldwide have experienced being exposed to some form of SH. A more recent systematic review on female nurses revealed that 49% of the nurses, in the included studies, have experienced SH (Luthar & Luthar, 2002). Studies, made in Sub-Saharan African countries, show that a rather low rate of nurses’ experience exposure to sexual harassment, varying from 10% in Gambia (Sisawo et al., 2017) and 13-16% in Ethiopia and Malawi (Banda et al., 2016; Fute et al., 2015).

Effects of Sexual Harassment

Sexual harassment can have different impacts on its victims both physical and psychological, i.e. discomfort, unwillingness going back to work, shame, fear, depression (Gabay & Shafran Tikva, 2020; Hutagalung & Ishak, 2012; M. Kim et al., 2018; Luthar & Luthar, 2002; Nelson, 2018;). While less grave or aggressive forms might cause discomfort to the victim, more serious forms can instead have a direct impact on the health and wellbeing such as depression, anxiety and fear (Hutagalung & Ishak, 2012; M. Kim et al., 2018; Luthar & Luthar, 2002). Several studies equally show that SH can have both negative psychological and physical effects on the victims and should therefore be considered as an occupation hazard for nurses around the world (Bjørkelo et al., 2010; M. Kim et al., 2018; Luthar & Luthar, 2002; Sisawo et al., 2017).

The field of SH in the context of clinical practice and nursing in Tanzania is still relatively unexplored and there is a need for further research regarding SH’s social and cultural circumstances, as well as its effects on the victims and care. Therefore, the overall aim of the present study was to examine the prevalence, type of and psychological effects of experienced SH among nurses and nursing students in a region hospital in Tanzania

Methods

Study Design

The study has a descriptive cross-sectional design. A study specific self-administered questionnaire about experiences of SH was used for data collection. The questionnaire was developed by the researchers and contained two sections, the first focused on demographic data, while section two related to questions about SH and the specific objectives of the study, see Online Appendix 1. The study population consisted of nurses and nursing students who corresponded to the study’s inclusion criteria.

Broad Objective

Determine the prevalence of SH of nurses and nursing students at a region hospital in northern Tanzania.

Specific Objectives

To determine the prevalence of sexual harassment of nurses and nursing students

To determine the different types and consequences of SH of nurses and nursing students

To examine gender differences between female and male nurses and nursing students who have been exposed to SH.

Study Setting

The research was conducted at a regional hospital in northern Tanzania, serving a population of approximately 1.8 million. The hospital is a referral hospital and has 20 departments and a bed capacity of 450 excluding 1.000 daily out-patients visits. A total of 298 nurses works at the region hospital. The hospital is as well an educational hospital with students from different professions within healthcare performing clinical placements the hospital. The total number of nursing students who were studying at the faculty of nursing at the close by medical college at the time of the data collection were 351.

Study Sample

Eligibility Criteria

Nurses who were available at the time of the study at KCMC.

Nursing students who were available at the time of the study at KCMC.

Inclusion Criteria

Male and female nurses and nursing students ≥18 years of age.

Nurses: Enrolled Nurses (EN), Assistant Nurse Officers (ANO) and Nurse Officers (NO).

Students: Pre-service bachelor science of nursing students, and in-service nursing students and pre-service diploma nursing students.

Exclusion Criteria

Nurses and students not available at the time for the data collection.

Sample Size

The 351 number of nursing students, who were at the faculty of nursing at the time of the data collection, comprised of 148 Pre-service BS students, 59 In-service BS and 144 diploma nursing students. The number of nurses, working at the hospital, were 298 and consisted of 60 EN, 179 ANO and 59 NO. Due to the shortage of studies on sexual harassment regarding nurses and nursing students in Tanzania or nearby context, i.e. Sub-Saharan Africa, we estimated the frequency of SH to be 10%, which was based on the results, revealed in a study done in Gambia regarding nurses and SH (Sisawo et al., 2017).

Sample Size Calculation

n =(z)2p(1−p)

d2

n= sample size

z=level of confidence 95% (1.96)

p=expected prevalence of SH 10% (0.1)

d=tolerated margin of error 5% (0.05)

add 10% for missing data

Calculation of the number of participants:

n = (1.96)2 × 0.1 × (1–0.1)

0.052

n = 138.29 + 13.8 = 152.09

According to the calculation, this study’s sample size should be 152 nurses. Since the calculation is based on previous prevalence of nurses and SH, and the present study includes both nurses and nursing students, we decided to increase the study sample up to 200, equally divided between nurses and nursing students.

Sampling Technique

This research was done using a non-probability purposive sampling method. The sampling technique was chosen, as it was not possible to use a random sampling method, regarding the aim of the study and size of the study group. The calculation is based on previous prevalence of nurses, and since this study includes both nurses and nursing students, we intended to include 200 participants in the study, equally divided between nurses 100 and nursing students n = 100.

Data Collection Tool—Study Specific Questionnaire

A validated questionnaire about sexual harassment in the healthcare section was not found at the time of the study start. Therefore, a study specific questionnaire was developed and used in the study, see Online Appendix 1. The questionnaire was developed by the researchers and contained two sections, the first focused on demographic data, while section two related to questions about SH and the specific objectives of the study. The questions in section two sought to investigate whether the participants had experienced SH or knew someone who had. The questions in part two also inquired about the circumstances of its occurrence (time frame, different expressions of sexual harassment), as well as posterior experiences and feelings. It was also possible to add free text comments for the participants regarding SH. In total, there were 15 questions in the questionnaire, not including the possibility to add comments.

A pre-test of the questionnaire, prior to the initiation of the study, was carried out on n = 20 nursing students and teachers. The pre-testing was made to secure that the questionnaire was user friendly and understood but also to confirm the correspondence between the question and the objectives of the study in accordance with Polit and Beck (2017). After the pre-test, the questionnaire was slightly modified according to the comments. The modifications were, however, minor, and a pre-test of the modified version of the questionnaire was not considered necessary to perform as it was validated by face value.

Data Collection Procedure

The matron of the hospital arranged meetings with the respective in-charge nurses of each ward of the hospital. They in turn, introduced the conductors of the study to nurses who met the inclusion criteria. The participating nurses were informed about the study and asked if they were willing to participate. Those, who decided to participate were handed written information and a consent form to sign prior to receiving the questionnaire. The participants then filled in the questionnaire without the presence of the researchers for the study. The questionnaires were reviewed during recollection to assure full completion.

The nursing students were approached during lectures and were given the same information and consent form as the professional nurses. The students filled in their questionnaires individually. The same procedure of posterior review was applied to the recollection of the students’ questionnaires.

According to the sample size calculation, a total of 100 nurses and 100 nursing students were asked to participate. All nurses, except 3 (97), filled in the survey and all nursing students (100).

Ethical Considerations

The study was carried out according to the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). Ethical clearance was obtained from the National Institute for Medical Research in Tanzania and from Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College ethical clearance committee. The study permission to conduct the study was obtained from the Executive Director of the hospital. The questionnaire was anonymous and voluntary. Participants were informed about the purpose of the study and asked to sign a consent form prior to their participation. The questionnaire was designed to ensure confidentiality. The collection of the questionnaires and the interpretation of data retrieved were done solely by the persons involved in the study and no information was handed out to third parties.

Statistical Analysis

Data was analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences [SPSS] Version 20 and descriptive statistics were summarized for categorical variable frequencies and proportions. This was used to describe the prevalence (including gender differences), different types and consequences of sexual harassment was determined and analyzed with descriptive statistics.

A simplified qualitative content analysis, inspired by Elo and Kyngäs (2008) was adopted regarding the free text answers. All the free text answers were read and thereafter sorted into three categories.

Results

Out of the 200 questionnaires distributed to the study population, a total of 197 questionnaires were collected. Of those, 97 were completed by professional nurses and100 by nursing students, giving a total response rate of 98.5% and a response rate among the nurses of 97%.

Demographic Characteristics

In total, 197 nurses and nursing students participated in the present study, whereof 133 (67.5%) were female and 64 (33.5%) were male. The nursing student group and nurse group consisted of seven sub-groups, students: in-service Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BScN), pre-service BScN, diploma, Master of Science (MSc) and nurses: assistant nurse officer, enrolled nurse, and nurse officer. The largest age group represented was 18-29 years (78.2%), only one of 197 participants was above 65 years old. The majority of the professional nurses were assistant nurse officers (55.7%) and had less than one year of work experience (35%). The most common education level among nursing students was diploma (46%). Further background characteristics can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants, n = 197.

| Variable | Frequency | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–29 | 154 | 78.2 |

| 30–41 | 18 | 9.1 |

| 42–53 | 13 | 6.6 |

| 54–65 | 11 | 5.6 |

| 65+ | 1 | 0.5 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 133 | 67.5 |

| Male | 64 | 32.5 |

| Occupation | ||

| Nurse | 97 | 49.2 |

| Nursing student | 100 | 50.8 |

| Education level students | ||

| In-service BScN | 18 | 18 |

| Pre-service BscN | 35 | 35 |

| Diploma | 46 | 46 |

| MSc | 1 | 1 |

| Occupational profession nurses | ||

| Assistant nurse officer | 54 | 55.7 |

| Nurse officer | 19 | 19.6 |

| Enrolled nurse | 24 | 24.7 |

| Years of work experience | ||

| Less than 1 year | 34 | 35 |

| 1–5 years | 33 | 34 |

| 5–10 years | 6 | 6.2 |

| 10–20 years | 9 | 9.3 |

| More than 20 years | 15 | 15.5 |

Prevalence of Sexual Harassment

Ten percent (19/197) of the respondents had experienced SH at their workplace. Five percent (5/197) respondents did not want to admit whether they had experienced SH or not. Of a total of 133 female participants, 10.5% had experienced sexual harassment, whereas the percentage among male participants (n = 64) was 7.8%.

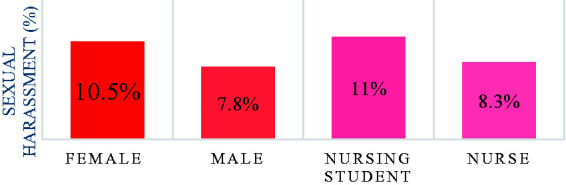

The majority of the 10% (19) of those, who reported being sexually harassed, 73.7% (14) were women. Risk ratio disclosed a 34.7% higher risk of SH for women than for men. Nursing students were shown to me more exposed to SH than professional nurses (11% to 8.3%), but the difference was not statistically significant p = 0.354. However, 53 (27%) of 197 the nurses and nursing students reported that they know a fellow student or colleague who had been sexually harassed. There was no significant difference between nurses and nursing students, p = 0.583. The majority (90.9%) of the respondents expressed knowledge about current laws against SH in Tanzania. Gender and occupational distributions are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Distribution of SH by Gender and Occupation. Distribution of SH by gender was calculated from n = 133 female participant and n = 64 male participants whereas occupation was calculated form n = 97 nurses and n = 100 nursing students.

Different Types of Sexual Harassment

The participants were given eleven types of SH from the questionnaire, see Table 2. The response rate (n = 62) includes both participants that have been sexually harassed and those who knew a victim of SH. The most common type reported was “sexual jokes and comments” (61.3%) followed by “unwelcome hugging or kissing” (48.4%). The varying types reported, did not differ between those who had been or those who knew someone that had been exposed to SH.

Table 2.

Types of SH.

| Different types of sexual harassment | Frequency | % (n = 62) |

|---|---|---|

| Had an intimate relationship to obtain his/her position at work or pass clinical practice | 14 | 22.6% |

| Unwelcome touching | 27 | 43.5% |

| Unwelcome hugging or kissing | 30 | 48.4% |

| Inappropriate psychical contact that made you feel uncomfortable | 19 | 30.6% |

| Inappropriate invitations to go out | 28 | 45.2% |

| Request or pressure for sex/other sexual acts | 17 | 27.4% |

| Any other unwelcome conduct of sexual nature | 14 | 22.6% |

| Sexual jokes or comments | 38 | 61.3% |

| Inappropriate staring | 12 | 19.4% |

| Have anyone showed, given, or left you sexual invitations | 10 | 16.1% |

| Attempt to have sex | 17 | 27.4% |

For those who were victims of SH, no significant difference could be found, when comparing the frequency of different types of SH between nursing students and nurses. Regarding severe SH, such as “attempts to have sex “or “request or pressure for sex/other sexual acts”, the reported frequency was 27.4%. However, a noticeable difference of severe SH was identified between nurses (n = 12) and nursing student (n = 5).

Among the self-reported male victims, 4 out of 5 reported “Sexual jokes and comments” as the most frequent type. “Request or pressure for sex/other sexual acts” was also identified to be frequent among the male victims (3 out of 5).

Perpetrator of Sexual Harassment

Physicians were reported to be the most common type of perpetrator (43.1%). Female nurses and nursing students were more exposed to SH from male physicians than male nursing students or nurses p = 0.047. The vast majority of the perpetrators were men (82.5%) and apart from physicians, supervisors or patient’s family members were among the perpetrator. No significant difference was, however, found between nurses and nursing students concerning reported type of perpetrator, but among male victims the perpetrators varied with no overrepresentation. Regarding male victims, 60% of the perpetrators were females.

Frequency of Perceived Consequences of Sexual Harassment

Among the respondents reporting being exposed to SH, 18 of 19 experienced at least one perceived consequence of SH, including i.e. anger and shame, see Table 3. In total, n = 54 consequences of SH were reported, and there were not any significant differences detected. However, between male and female victims a difference was discovered. Male victims reported at the same frequency “depressed” and “ashamed” as the most common perceived effect.

Table 3.

Perceived Consequences of Sexual Harassment (n = 18 Respondents).

| Consequence | Frequency(Total = 54 ) |

|---|---|

| Anger | 9 |

| Shame | 8 |

| Uncomfortable going back to work | 7 |

| Irritation | 6 |

| Depression | 6 |

| Sadness | 6 |

| Affected work performance | 4 |

| Trouble sleeping | 4 |

| Upset | 3 |

| Afraid | 1 |

Open Comments by the Participants on Sexual Harassment

Additional free-text comments could be done by the participants regarding SH and the answers were analyzed qualitatively. Several participants added comments about feeling ashamed, humiliated, and depressed after the event and therefore did not tell anyone and thus continued feeling uncomfortable during work. The comments show a great discomfort and worry from the participants in the study. It is also evident that in the professional role, the nurses and students have, it is difficult to express the negative feelings SHs result in for the victims. It is as well difficult to say “no” because of the inequality in the professional roles. The participants felt that they were disrespected, forced and minimized and that SH was very bad behavior. Some participants were even forced to do things they did not agreed to and did not want to discuss it with others or report it.

Some were afraid of telling and developed an avoiding manner and were stigmatized. Enhanced knowledge and education were pointed out as important issues to prevent SH, as well as that action should be taken against the perpetrators. Emphasized awareness of rights human rights, not only in the healthcare section, but in the society as a whole was considered to be essential as well.

The comments are categorized into 3 categories; disrespect, stigmatization and fear and knowledge and education, see Table 4.

Table 4.

Categories for the Open Free-Text Comments and Illustrating Examples.

| Category | Examples of free text comments |

|---|---|

| Disrespect | “Sexual harassment is a bad act to our societies. Give people discomfort in their life, sometime lead to suicide after getting psychological torture” “This is a bad act in any societies. It needs to be destroyed because it embarrasses women” “Nursing profession is a good job. But I see people are over underrating us more in health facilities. Other professions like doctors and pharmacist take us as a sexual tool” “Doctors asking for intercourse and forcing us to have intercourse” “I kept on thinking that those who did these things didn´t respect me or they lowered my value” |

| Stigmatization and fear | “Because it looks to be a normal thing in this profession. So, you handle it yourself” “Some of the staff member like me are not interested to expose things like this”. “When I was a girl (24 years) one senior doctor used to admire me attempted to approach me to sexual relation. I was very afraid as he was almost the same age as my father. I used to escape him and when he was on duty, I was worried, especially during the night shift. I avoided being alone and never walked into his office. It took time but finally he gave up following me” |

| Knowledge and education | “Most people don´t know much about SH and their rights. There is a need of talking about it so everyone can understand what SH is” “Education to staff about SH and if it happens where to report it. And action against the person responsible for the act should be taken” “People should be given education about the impacts/effects of sexual harassment. This should include people from both town and in remote areas” |

Discussion

Although previous studies on SH in Tanzania have been conducted, little has been written about SH in the healthcare settings in Tanzania. This study has examined cases of participants who experienced exposure to SH or reported knowing a colleague or a fellow student that had been so. The results showed a 9.6% prevalence of SH in the study group; however, it became considerably higher (36.5%) when including knowledge of exposure to a third party. Due to lack of previous studies of the nursing context in Tanzania, the results were compared to other studies from the Sub-Sahara region. In Gambia, 10% of the nurses reported exposure to SH (Sisawo et al., 2017) and 16% prevalence amongst nurses in Malawi (Banda et al., 2016). In Ethiopia, the prevalence was similar (Fute et al., 2015) but in Egypt the prevalence was 70%, which is very high compared to other studies (Abo Ali et al., 2015). Furthermore, we found that both men and women were exposed to SH, but women were more frequently victims than men, 10.5% versus 7.8%, and the distribution between female and male victims (n = 19) was 73.7% female, versus 26.3% male. Although this study has not calculated a statistic significant value of women being more often exposed to SH the results are supported by previous studies (Bronner et al., 2003; Fute et al., 2015; K. Lee et al., 2007; Somani et al., 2015). In 2017, it was estimated by United Nation Women (2017) that 35% of all women worldwide have been exposed to either physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence or sexual violence by a non-partner. This report also strengthens the study results, where women being more frequently exposed to SH than men. However, is it interesting that male nursing students expressed being sexually harassed in the present study. The most common form of SH was “sexual jokes and comment” (61.3%) followed by “unwelcome touching and hugging” (48.4%) which corresponds with previous findings of SH among nurses and nursing students (Abo Ali et al., 2015; Adams et al., 2019; Banda et al., 2016; Bronner et al., 2003), as well as among female university students in Ethiopia (Almaz et al., 2015). A significant gender difference between the reported types was difficult to establish due to the low number of self-reported male victims (n = 5). However, both female and male victims reported “sexual jokes and comments” as the most frequent type of SH. A notable discovery of this study was the high prevalence of severe type of SH, which was found to more frequent among young nurses, and not students. Comparable result was detected by Bronner et al. (2003) and by Numhauser-Henning and Laulom (2012).

The most common perpetrators were physicians (43.1%), which corresponds with previous research (Lamesoo, 2013). Among male victims, the situation was different, 4 out of 5 reported different perpetrators. There are studies (Bronner et al., 2003; Somani et al., 2015) which evince patients to be the most frequent type of perpetrator. Yet, the identification of physicians being the main perpetrator in this study could be due to the hospital-staff hierarchies, where physicians are considered superior to nurses (Lamesoo, 2013). This was also what some of the participants expressed. Several nurses felt that physicians were underestimating them and taking advantage of them. The results also indicated that men (78.9%) were more likely be perpetrators than women, which is supported in a review by Spector et al. (2014).

When including all reported cases of SH (personal and by proxy experiences), the prevalence became considerably higher (36.5%) compared to the personal cases alone (9.6%). The prevalence of 36.5% is comparable to the result of the quantitative review of 151,347 nurses where 25% stated have been sexually harassed (Spector et al., 2014). However, the low frequency of personal cases compared to all cases of SH in our study might imply an existence of a high number of non-reported cases. Sexual harassment in our study might imply an existence of a high number of non-reported cases. The prevalence could therefore be considerably higher than 9.6%. As previously discussed in the theoretical framework, the factor of stigma and unawareness of rights to bodily integrity are likely to play a big part in the biases of the answers. Several comments from the participants precisely suggest this. In the present study, the reporting of SH was low compared to studies from other parts of the world which have presented a higher prevalence of self–report cases of SH on NNS; 37.1% in Turkey, 50.8% North Korea, Egypt 70% and 91% in Israel (Abo Ali et al., 2015; Bronner et al., 2003). The differences in numbers can be interpreted in three different ways: firstly, that prevalence of SH actually differs between countries and regions due to different socio-cultural contexts; secondly, that the interpretation and acceptance level of inappropriate sexual behavior might differ due to the same; and thirdly, and most plausibly, that both these factors intervene in the experience of sexual harassment. The relatively small difference in the ratio male-female exposure is noteworthy compared to findings in previous studies on other groups which indicates that women always tend to be more exposed to SH than men.

Moreover, the results of this study indicate SH to be associated with negative psychological outcomes and could consequently become an occupational hazard for nurses. This corresponds to results from previous studies (Almaz et al., 2015; M. Kim et al., 2018; T. I. Kim et al., 2017) Further, SH at work increases anxiety and affects the nurses’ ability to focus and provide safe and adequate care. The results indicate that approximately 30% felt depressed and uncomfortable going back to work after experiencing sexual harassment. More than 40% of the respondents also reported feeling angry and ashamed after the event. A significant relation between exposure to sexual harassment, and low self-esteem and low job satisfaction was also found among female nurses in training in a study conducted by the University of Sargodha, Pakistan (Malik et al., 2017) and with a study performed in Sri Lanka (Adams et al., 2019) where nurses experienced guilt. Additionally, through a meta-analysis of the consequences of experiencing SH it has been concluded that there is an association between SH and physical and physiological negative outcome such as withdrawing from work, less occupational commitment and even post-traumatic stress disorder (K. Lee et al., 2007). The quality of care was also affected when nurses had been sexually harassed (Shafran-Tikva et al., 2017). Finally, the working condition must change for nurses. Women and men must feel safe at their workplace without the possibilities of being sexually harassed. It cannot be acceptable that your choices of occupation have an impact on your physical and mental health. As the United Nation General Assembly stated 1948- to feel safe is a human right (United Nation General Assembly, 1948).

Strength and Limitations

The relevance of the topic is based on the lack of previous studies on SH among nurses in Tanzania, since it both enriches the discussion on SH as such in the country and furthermore discusses the context of SH within the nursing profession. Both students and professional nurses were chosen to participate in the study to uncover if both groups were prone to exposure to sexual harassment, and if there could be any parallels drawn to the issue of rank within the hospital. The topic might inflict a problem on the study itself, firstly because SH is a stigmatized and therefore is likely to be avoided by those who have been exposed to it. The method used of this research was descriptive cross-sectional method and was well suited for this type of study due to its exploratory character. Similar studies on SH have also used this method. A validated questionnaire on SH applicable on both nurses and nursing students was not found thus a study-specific questionnaire was used which was not validated. On the other hand, it was developed according to current research methods (Polit & Beck, 2017). As the number of participants in the present study was limited (197) and the prevalence of SH was around 10% we therefore recommended that a larger study be performed with more validated evidence about prevalence, forms, consequences and gender differences of sexual harassment. However, there was a high response rate of 98% which strengthens the study’s validity.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the study determined that almost 10% of the participants had been exposed to sexual harassment. However, a considerably higher prevalence (36.5%) was found when including by proxy victims of sexual harassment. The most frequent forms of SH were “sexual jokes and comments” and “unwelcome hugging or kissing”. It can also be concluded that there are some gender differences between female and male nurses and nursing students where there was a higher frequency on SH among female nurses and nursing students. The perpetrators were often men and physicians. Sexual harassment could become an occupational hazard for nurses. Over 30% reported feeling depressed and uncomfortable going back to work after being harassed, and over 40% stated feeling angry and afraid.

Implications for Practice

This study has contributed on research on SH of nurses and nursing students in Tanzania. Studies from other countries have found that SH is a common problem amongst nurses and could lead to an occupational hazard. There is a lack of knowledge of what SH is and how it can be manifested. To reduce this, our recommendation is to educate nurses and nursing students on the topic and how to prevent and cope with SH.

We also encourage sexual and reproductive rights to be integrated in all education from primary school up to university level in Tanzania, since it is equally important that prospective perpetrators gain knowledge about what behavior is acceptable, and what is not. Hospitals and medical colleges should emphasize their possibilities to give support and assistance to the victims of SH and installing prevention methods should also considered. Further studies among other staff groups and student groups are encourage.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-son-10.1177_2377960820963764 for Sexual Harassment in Clinical Practice—A Cross-Sectional Study Among Nurses and Nursing Students in Sub-Saharan Africa by Teresia Tollstern Landin BSc, RN, Tove Melin MSc, Victoria Mark Kimaka BSc, RN, David Hallberg PhD, Paulo Kidayi MSc, RN, Rogathe Machange MSc, RN, Janet Mattsson PhD, RN, Gunilla Björling PhD, RN in SAGE Open Nursing

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Gunilla Björling https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1445-900X

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Abo Ali E. A., Saied S. M., Elsabagh H. M., Zayed H. A. (2015). Sexual harassment against nursing staff in Tanta University Hospitals, Egypt. The Journal of the Egyptian Public Health Association, 90(3), 94–100. 10.1097/01.EPX.0000470563.41655.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams E. A., Darj E., Wijewardene K., Infanti J. J. (2019). Perceptions on the sexual harassment of female nurses in a state hospital in Sri Lanka: A qualitative study. Global Health Action, 12(1), 1560587. 10.1080/16549716.2018.1560587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- African Development Bank Group. (2015). Empowering African women: An agenda for action. https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/African_Gender_Equality_Index_2015-EN.pdf

- Agsi R. (2018). Sexual harassment in medicine—#MeToo. New England Journal of Medicine, 378(3), 209–211. 10.1056/NEJMp1715962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almaz M., Getachew K., Mohammed Y. (2015). Prevalence of physical, verbal and nonverbal sexual harassments and their association with psychological distress among Jimma University female students: A cross-sectional study. Ethiopian Journal of Health Sciences, 25(1), 29–38. 10.4314/ejhs.v25i1.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banda C., Mayers P., Duma S. (2016). Violence against nurses in the Southern region of Malawi. Health SA Gesondheid, 21, 415–421. 10.1016/j.hsag.2016.01.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bangham, C. (2016). Assessing the Efficacy of Sexual Health Education in Tanzania. Proccedings of the National Conference on Undergraduate Research (NCUR). University of North carolina Asheville. pp. 524–550.

- Bjørkelo B., Einarsen S., Nielsen M. B., Notelaers G. (2010). Sexual harassment: Prevalence, outcomes, and gender differences assessed by three different estimation methods. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 19(3), 252–227. 10.1080/10926771003705056 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bronner G., Ehrenfeld M., Peretz C. (2003). Sexual of harassment nurses and nursing students. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 42(6), 637–644. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo S., Kyngäs H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fute M., Mengesha Z.-B., Wakgari N., Tessema G.-A. (2015). High prevalence of workplace violence among nurses working at public health facilities in Southern Ethiopia. BMC Nursing, 14(1), 9. http://dx.doi.org.till.biblextern.sh.se/10.1186/s12912-015-0062-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay G., Shafran Tikva S. (2020). Sexual harassment of nurses by patients and missed nursing care—A hidden population study. Journal of Nursing Management, 00, 1–7. 10.1111/jonm.12976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Moreno C., Pallitto C., Devries K., Stöckl H., Watts C., Abrahams N. (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. World Health Organization.

- Hadi A. (2017). Patriarchy and gender-based violence in Pakistan. European Journal of Social Sciences Education and Research, 10(2), 297–304. http://journals.euser.org/index.php/ejser/article/view/2485 [Google Scholar]

- Hutagalung F., Ishak Z. (2012). Sexual harassment: A predictor to job satisfaction and work stress among women employees. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 65, 723–730. [Google Scholar]

- Kahsay W. G., Negarandeh R., Dehghan Nayeri N., Hasanpour M. (2020). Sexual harassment against female nurses: A systematic review. BMC Nursing, 19(1), 58. 10.1186/s12912-020-00450-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M., Kim T., Tilley D. S., Kapusta A., Allen D., Cho H. S. M. (2018). Nursing students’ experience of sexual harassment during clinical practicum: A phenomenological approach. Korean Journal of Women Health Nursing, 24(4), 379–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T. I., Kwon, Y. J., & Kim, M. J. (2017). Experience and perception of sexual harassment during the clinical practice and self-esteem among nursing students. Korean Journal of Women Health Nursing, 23(1), 21–32. 10.4069/kjwhn.2017.23.1.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamesoo K. (2013). Some things are just more permissible for men: Estonian nurses’ interpretations of sexual harassment. Nora—Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research, 21(2), 123–139. 10.1080/08038740.2013.795190 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K., Steel P., Willness C. (2007). A meta-analysis of the antecedents and consequences of workplace sexual harassment. Personnel Psychology, 60(1), 127–162. 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00067.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.-K., Song J.-E., Kim S. (2011). Experience and perception of sexual harassment during the clinical practice of Korean nursing students. Asian Nursing Research, 5(3), 170–176. 10.1016/j.anr.2011.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar V., K., Luthar H., K. (2002). Using Hofstede’s cultural dimensions to explain sexually harassing behaviours in an international context. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 13(2), 268–284. 10.1080/09585190110102378 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malik N., Malik S., Qureshi N., Atta M. (2017). Sexual harassment as predictor of low self esteem and job satisfaction among in-training nurses. FWU Journal of Social Sciences, 8(2), 107–116. [Google Scholar]

- McCann D. (2005). Sexual harassment at work: National and international responses. International Labor Office. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_protect/—protrav/—travail/documents/publication/wcms_travail_pub_2.pdf

- Nelson R. (2018). Sexual harassment in nursing: A long-standing, but rarely studied problem. AJN, American Journal of Nursing, 118(5), 19–20. 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000532826.47647.42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numhauser-Henning A., Laulom R. S. (2012). Harassment related to sex and sexual harassment law in 33 European countries: Discrimination versus dignity. European Union. http://ec.europa.eu/justice/gender-equality/files/your_rights/final_harassement_en.pdf

- Parliament of the United Republic of Tanzania. (1998). The sexual offences special provisions act. http://www.saflii.org/tz/legis/num_act/sospa1998366.pdf

- Pasha-Robinson L. (2017). Me too': Millions of women share sexual assault stories as new ‘him though’ hashtag urges men to take responsibility. Independent. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/women-me-too-hashtag-twitter-sexual-harassment-stories-trending-him-though-men-responsibility-a8004806.html

- Polit D. F., Beck C. T. (2017). Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (10th ed.). Wolters Kluwer. [Google Scholar]

- Shafran-Tikva S., Zelker R., Stern Z., Chinitz D. (2017). Workplace violence in a tertiary care Israeli hospital—A systematic analysis of the types of violence, the perpetrators and hospital departments. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research, 6(1), 43–53. 10.1186/s13584-017-0168-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisawo J. E., Yacine Y. S., Ouédraogo A., Huang S.-L. (2017). Workplace violence against nurses in the Gambia: Mixed methods design. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 311–311. 10.1186/s12913-017-2258-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somani R., Karmaliani R., Mc Farlane J., Asad N., Hirani S. (2015). Sexual harassment towards nurses in Pakistan: Are we safe? International Journal of Nursing Education, 7(2), 286–289. 10.5958/0974-9357.2015.00120.8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spector P. E., Zhou Z. E., Che X. X. (2014). Nurse exposure to physical and nonphysical violence, bullying, and sexual harassment: A quantitative review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 51(1), 72–84. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stop Street Harassment. (2018). The fact behind the #metoo movement: A national study on sexual harassment an assault. http://www.stopstreetharassment.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Full-Report-2018-National-Study-on-Sexual-Harassment-and-Assault.pdf

- Tekin Y., Bulut H. (2014). Verbal, physical and sexual abuse status against operating room nurses in Turkey. Springer Science & Business Media. 10.1007/s11195-014-9339-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. (1948). UN Charter. Chapter 1 and 2: Purposes and Principles. Article 1–3. https://www.un.org/en/sections/un-charter/chapter-i/index.html

- United Nation Women. (2017). Facts and figures: Ending violence against women. http://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women/facts-and-figures

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2005). UNHCR’s policy on harassment, sexual harassment, and abuse of authority. http://www.un.org/womenwatch/osagi/UN_system_policies/(UNHCR)policy_on_harassment.pdf

- World Health Organization. (2014). The health of the people—An African regional health report. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/137377/9789290232612.pdf?sequence=4

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-son-10.1177_2377960820963764 for Sexual Harassment in Clinical Practice—A Cross-Sectional Study Among Nurses and Nursing Students in Sub-Saharan Africa by Teresia Tollstern Landin BSc, RN, Tove Melin MSc, Victoria Mark Kimaka BSc, RN, David Hallberg PhD, Paulo Kidayi MSc, RN, Rogathe Machange MSc, RN, Janet Mattsson PhD, RN, Gunilla Björling PhD, RN in SAGE Open Nursing