Abstract

Introduction:

Due to scarring, appearance anxiety is a common psychological difficulty in patients accessing burns services. Appearance anxiety can significantly impact upon social functioning and quality of life; thus, the availability of effective psychological therapies is vital. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is considered useful for treating distress associated with other health conditions and may lend itself well to appearance anxiety. However, no published research is currently available.

Methods:

Three single case studies (two male burns patients; one female necrotising fasciitis patient) are presented where appearance anxiety was treated using ACT. A treatment protocol was followed and evaluated: the Derriford Appearance Scale measured appearance anxiety; the Work and Social Adjustment Scale measured impairment in functioning; the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire measured acceptance (willingness to open up to distressing internal experiences); and the Committed Action Questionnaire measured engagement in meaningful and valued life activities. Measures were given at every treatment session and patient feedback was obtained. One-month follow-up data were available for two cases.

Results:

After the intervention, all patients had reduced functional impairment and were living more valued and meaningful lives. No negative effects were found.

Discussion:

These case studies suggest that ACT may be a useful psychological therapy for appearance anxiety. The uncontrolled nature of the intervention limits the conclusions that can be drawn.

Conclusion:

A pilot feasibility study to evaluate the effectiveness of ACT for appearance anxiety is warranted.

Lay Summary

Many patients with scars can feel distressed about their appearance. This is known as appearance anxiety and can include patients accessing burns services. Appearance anxiety can stop patients from enjoying a good quality of life and impact upon important areas of daily functioning. It is therefore important that psychological therapies are effective. However, research investigating the effectiveness of psychological therapies is limited. This paper describes the psychological therapy of three patients who were distressed about scarring. A psychological therapy called Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) was used as part of standard care and evaluated using questionnaires and patient feedback. After the course of ACT, all patients were less impacted day-to-day by their appearance anxiety and were living more valued and meaningful lives. No negative effects were found. These case studies suggest that ACT may be a useful psychological therapy for appearance anxiety and further research evaluating it should be completed.

Keywords: Appearance anxiety, scarring, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, ACT, burns, necrotising fasciitis, disfigurement

Introduction

People with visible differences, whose appearance is considered different compared to the culturally defined ‘norm,’ can experience psychological distress1–3 and receive negative social responses from others, including stares and unsolicited questions. 4 Appearance anxiety (distress related to appearance) is a common difficulty affecting those with visible differences,5,6 including the burns population.7,8 Appearance anxiety falls on a continuum of distress and can negatively affect social, occupational and relational functioning.9,10 Effective psychological therapies to reduce appearance anxiety are therefore vital.

Several studies have highlighted unhelpful cognitive and behavioural factors in the maintenance of appearance anxiety, including negative beliefs about the value and acceptability of appearance, social comparisons, self-focused attention and avoidance behaviour.5,11,12 As a consequence, cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), which aims to reduce unhelpful cognitive and behavioural factors, has been a common therapeutic approach. 13 However, there is a lack of high-quality studies investigating the effectiveness of CBT, or indeed any other psychological therapy, for appearance anxiety associated with a visible difference.14,15

More recently, three studies have highlighted the potential importance of other psychological factors such as mindfulness (the ability to be in the present moment),16,17 acceptance (willingness to experience internal experiences, including distress),17,18 cognitive defusion (standing back from thoughts) 17 and committed action (doing what matters despite distress) 17 in reduced appearance anxiety. These are all elements of ‘psychological flexibility’, which underpins a newer form of CBT that incorporates mindfulness and acceptance, called Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). 19 ACT typically teaches people the following: to be more accepting of (willing to feel) distressing internal experiences (such as emotions, thoughts or physiological sensations); to stand back or get some distance from thoughts that get in the way of people doing what matters to them; and to be in the present moment, rather than caught up in the past or the future. The overall aim of ACT is not to reduce psychological distress per se, but rather to help people live with their distressing experiences so that they can choose to behave in ways that enable them to live their life more meaningfully. There is increasing evidence that ACT is effective in reducing psychological difficulties such as anxiety and depression, as well as reducing distress associated with chronic health problems. 20 Improvements have been reported after individual and group therapy of 6–12 sessions in patients across a variety of chronic physical health conditions, late-stage cancer and chronic pain,21–23 and one-day workshops targeting obesity-related distress and diabetes self-management.24,25 However, there is no published research exploring the effectiveness of ACT for appearance anxiety despite this being viewed as potentially well-suited. 26 Published clinical case studies are useful in exploring whether a psychological therapy is helpful to patients in real-life clinical settings and can help inform whether conducting further controlled studies is warranted. The current paper presents the use of ACT with three patients with appearance anxiety associated with scarring.

Methods

Participants

Three patients from a UK burns service were referred to the affiliated clinical psychology service as part of standard care. Patients received usual clinical care and provided informed written consent to the anonymised dissemination of their therapy. All patients were experiencing appearance anxiety, determined through a clinical interview by one of the treating clinical psychologists (authors LS and AT) and completion of the Derriford Appearance Scale (DAS-24). 27

Case 1: ‘Adam’

Adam was a 21-year-old white British man with a 2% total body surface area (TBSA) full-thickness flame burn to his hand following a workplace accident six months before the intervention. He was employed full-time and was living with his partner at the time of the accident. After the accident, Adam developed post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which had been treated successfully through trauma-focused psychological therapy by the second author (AT). In addition, Adam developed appearance anxiety due to scarring, and treatment for this began after his symptoms of PTSD had reduced to subclinical levels, as determined by the treating clinical psychologist (AT) and his self-report. He did not have a history of psychological problems before the accident but he reported that he had always had a degree of poor body image but that this had never impacted on his daily functioning. He worried about how others would perceive his hand, covered his scars, avoided holding hands with his partner and withdrew socially. This negatively impacted his relationship and social life. Adam received eight sessions of ACT. He cancelled and rearranged four sessions and had no non-attendances.

Case 2: ‘Paul’

Paul was a 26-year-old white British man who sustained 8% TBSA mixed-depth burns to his face and hands during a workplace welding accident 13 months before the intervention. He had been working full-time in the welding industry before the accident and lived with his partner and pre-school daughter. He had no history of psychological difficulties. After the accident, Paul developed PTSD, which had been treated successfully through trauma-focused psychological therapy by the second author (AT). Before the intervention for his appearance anxiety, Paul’s symptoms of PTSD were in the subclinical range and not impacting upon any area of his life. Paul experienced appearance anxiety associated with scarring on his hands and pigmentation changes to his face. He was troubled by thoughts about others judging him negatively and worried others would ask questions and that he would not be able to manage social exchanges. He spent excessive amounts of time checking and concealing his scarring by clothing, gloves and make-up. He was isolating himself, avoiding public places and had stopped doing meaningful activities with his young daughter, such as taking her to nursery, swimming and dance lessons. Paul received nine sessions of ACT. He cancelled and rearranged four sessions and had no non-attendances.

Case 3: ‘Jessica’

Jessica was a 39-year-old white British woman who developed necrotising fasciitis five months before the intervention. Before being hospitalised, she was working part-time and living with her partner and three school-aged children. She had a history of postnatal depression but was not depressed at the time of her illness. The necrotising fasciitis left significant scarring and contour changes to her leg. Jessica had appearance anxiety related to the shape of her leg and was spending excessive amounts of time attempting to make her legs look more symmetrical, using bandages. She was avoiding wearing tight clothing and swimming (her former hobby). She felt self-conscious when in public places and was overwhelmed by thoughts about what other people would think about her leg. She also felt burdened by scar management procedures. Jessica received six sessions of ACT. She cancelled and rearranged one session and had no non-attendances. Jessica also developed PTSD associated with her experience of being rushed to hospital, developing sepsis and undergoing emergency surgery. This was treated using trauma-focused psychological therapy after the detailed intervention for her appearance anxiety by the first author (LS), in line with Jessica’s main concern, which was her appearance anxiety.

Procedure

As part of routine care, patients were assessed to determine suitability for psychological therapy by the treating clinical psychologists (authors LS and AT). Patients were deemed appropriate for therapy if the treating psychologists believed that they were able to appropriately engage, there were no concerns about suicidal risk or risk to others, there was no other mental health problems that required urgent or mental healthcare, and if patients stated that they wanted therapy to manage their appearance anxiety. In the period of treating the three cases presented, three additional patients were assessed and deemed suitable for the intervention. They were offered the intervention but declined any form of psychological therapy.

ACT intervention

In the absence of empirically supported ACT treatment protocols for appearance anxiety, an ACT protocol had been developed by the first and second authors (LS and AT) who specialise in treating psychological difficulties due to visible differences and are highly trained in ACT. Therapy sessions were 60 min long, usually delivered weekly and involved giving between-sessions tasks. Therapy sessions were delivered in person by the treating psychologists (LS and AT) at the hospital where the patients had received their medical care from the burns service. Therapy ended when patients reported that they had achieved their therapy goals and/or felt able to manage any residual distress independently, through clinical conversations with the treating clinical psychologists (LS and AT). The full clinical protocol is available from the corresponding author but is summarised as follows:

Session 1: Introducing ACT; Recognising that current ways of managing appearance anxiety are not working; Introducing the idea of willingness to feel anxiety and learning to live with it (acceptance);

Session 2: Identifying what matters/values; Mindfulness exercise; Further introduction to acceptance using the ‘passengers on the bus’ exercise 19 ;

Session 3: Developing acceptance through metaphors, scaling and teaching acceptance techniques; Identifying a first behavioural step to living life according to values; Experiential acceptance exercise 19 ;

Session 4: Techniques to aid standing back from difficult thoughts about appearance and others’ reactions (cognitive defusion) 19 ;

Session 5: Developing a stepped plan of behavioural changes patients would like to make in line with values; Reinforcement of acceptance and cognitive defusion techniques; Experiential acceptance exercise 19 ;

Session 6: Review of behavioural changes made; Trouble-shooting difficulties by reinforcing acceptance and cognitive defusion techniques; Introducing the idea of being distinct from thoughts and feelings; Mindfulness exercise;

Session 7: Review of behavioural change and trouble-shooting difficulties by reinforcing acceptance and defusion techniques; Mindfulness exercise; Developing awareness of being in the present moment;

Session 8 onwards: Review of behavioural changes made; Trouble-shooting difficulties by reinforcing acceptance and cognitive defusion techniques; Advanced troubleshooting exercises as required.

Measures

Patients were asked to complete four outcome measures, using paper questionnaires, at baseline (while on the waiting list for the service), as part of an initial clinical assessment by the clinical psychologist, after every treatment session, and at the one-month follow-up. Only one patient completed the outcome measures at baseline. All patients completed the measures during the assessment. Patients were asked to complete the measures after treatment sessions at home and return them at their next session, and data was collected after the majority of sessions. Follow-up data was available for two patients as one patient moved out of the area and did not respond to follow-up attempts by telephone.

The DAS-24 27 was used to measure appearance anxiety. It consists of 24 items measuring distress associated with appearance (e.g. ‘How rejected do you feel?’ and ‘I avoid communal changing rooms’). Total scores were in the range of 10–96, where higher scores denote increased distress. Norms are available for general and clinical populations but there is no clinical cut-off score as distress is conceptualised on a continuum. This measure is commonly used in appearance research and was used in a previous study exploring the relationship between appearance anxiety and psychological flexibility after burns. 17

The Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS) 28 was used to measure impairment in functioning (e.g. ‘Because of the way I feel, my social leisure activities involving other people, such as parties, outings, visits, dating, home entertainment, cinema, are impaired’). It consists of five items and total scores are in the range of 0–40, with higher scores indicating increased impairment. Scores in the range of 1–10 indicate ‘Mild’ functional impairment, scores of 11–20 suggest ‘Moderate’ functional impairment and scores ⩾ 21 indicate ‘Severe’ functional impairment. This measure is commonly used in clinical settings to determine functional impairment and change after treatment.

The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ-II) 29 was used to measure acceptance (e.g. ‘I’m afraid of my feelings’). It has seven items, the total score is in the range of 7–49, and lower scores indicate greater acceptance. Scores of ⩾ 24 suggest probable clinical distress. This is a widely used measure of psychological flexibility and has been used in previous research after burns. 17

The Committed Action Questionnaire (CAQ-8) 30 was used to measure valued action/doing what matters. The scale contains eight items (e.g. ‘If I feel distressed or discouraged, I let my commitments slide’) and higher scores indicate increased valued living. Total scores are in the range of 0–48 and no norms are available. It has been previously used in research exploring psychological flexibility in burns patients. 17

Results

Adam

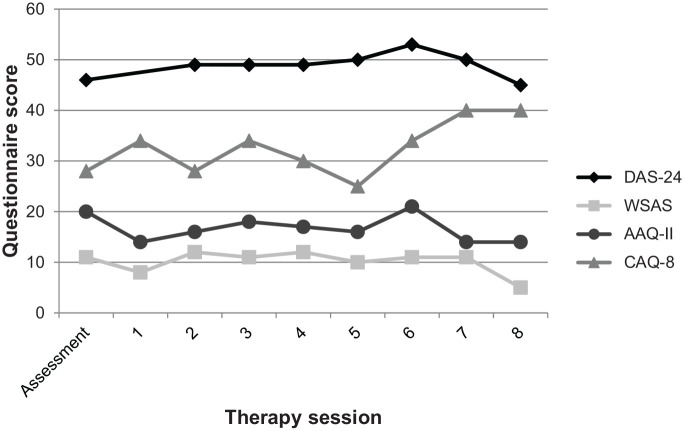

Figure 1 illustrates that during therapy Adam gradually began living a more valued life (CAQ-8 score increased from 28 to 40). He developed new social interests and gradually started attending social events that he had been avoiding and taking more opportunities at work. Adam continued to dislike the appearance of his scar, experience anxiety about others’ reactions to it and avoid holding hands with his partner (evidenced by a similar DAS-24 score of 46 before therapy and 45 after therapy). However, during therapy his willingness to experience his anxiety (acceptance) increased (AAQ-II score decreased from 20 to 14). He learnt ways to live with his anxiety and stand back from unhelpful thoughts so they had less impact on his functioning (WSAS score decreased from 11 to 5). At the end of therapy, Adam felt happier, more confident and motivated, and had increased self-esteem, using the patient’s self-report as well as behavioural observations by the treating clinical psychologist (author AT). He reported feeling confident in utilising skills learnt during therapy to independently work towards allowing his partner to hold his hand/touch his scar. As previously detailed, no follow-up data were available on Adam due to him moving out of the area and not responding to telephone follow-up attempts.

Figure 1.

Adam’s questionnaire scores for assessment and ACT therapy sessions. DAS-24: higher scores indicate increased appearance anxiety; WSAS: higher scores indicate greater functional impairment; AAQ-II: higher scores indicate reduced acceptance; CAQ-8: higher scores indicate greater valued living.

Paul

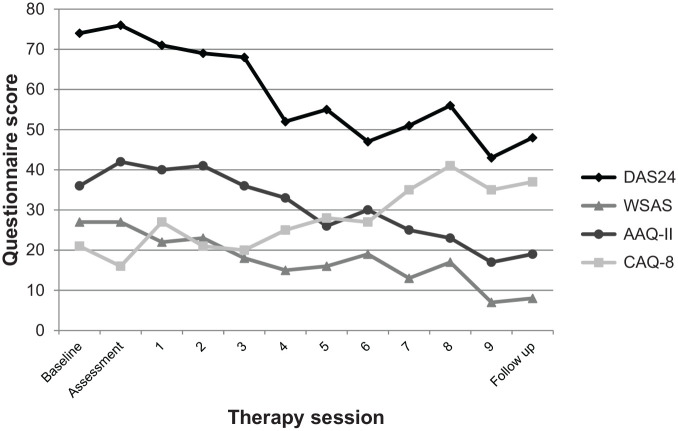

Figure 2 shows Paul’s reduced appearance anxiety during therapy (DAS-24 score reduced from 74 to 48). By the end of therapy, his anxiety was having less impact on his functioning (WSAS score reduced from 27 to 8) and he gradually started living his life more in line with his values (CAQ-8 score increased from 21 to 37). During therapy, he learnt to be willing to experience anxiety (AAQ-II score reduced from 36 to 19) and how to better manage his unhelpful thoughts about his scar and other people’s judgements and reactions. By the end of therapy, he had returned to socialising with friends and taking his daughter to nursery, swimming and dance lessons. He was living according to his values of being a present father and focused on relationships with others. Gains were sustained at the one-month follow-up.

Figure 2.

Paul’s questionnaire scores for baseline, assessment, ACT therapy sessions and one-month follow-up. DAS-24: higher scores indicate increased appearance anxiety; WSAS: higher scores indicate greater functional impairment; AAQ-II: higher scores indicate reduced acceptance; CAQ-8: higher scores indicate greater valued living.

Jessica

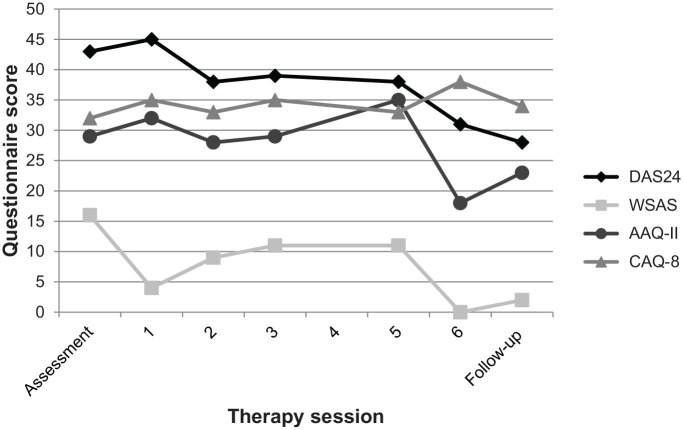

Figure 3 demonstrates Jessica’s reduction in appearance anxiety (DAS-24 score reduced from 43 to 28) during therapy. She became more willing to experience anxiety and self-consciousness when in public (AAQ-II score reduced from 29 to 23) and learnt how to manage distressing thoughts about the appearance of her leg. By the end of therapy, the impact of her appearance anxiety on her functioning had reduced (WSAS score reduced from 16 to 2) and she was living a more valued life (CAQ-8 score increased from 32 to 34). She was no longer making attempts to make her legs look more symmetrical using bandages, was wearing tight clothing when she wanted to and had returned to swimming. She also no longer felt burdened by scar management procedures and was doing these routinely. Gains were sustained at the one-month follow-up.

Figure 3.

Jessica’s questionnaire scores for assessment, ACT therapy sessions and one-month follow-up. DAS-24: higher scores indicate increased appearance anxiety; WSAS: higher scores indicate greater functional impairment; AAQ-II: higher scores indicate reduced acceptance; CAQ-8: higher scores indicate greater valued living.

Discussion

These three case studies illustrate the possible effectiveness of ACT for patients experiencing appearance anxiety. By the end of the intervention, all patients had reduced functional impairment and were living more valued and meaningful lives. No negative effects were found. A reduction in appearance anxiety was observed in two cases. In the other case, appearance anxiety remained at a similar level throughout therapy, but gains were made in valued living and functioning. This is in line with the nature of ACT, which does not aim to reduce distress but rather improve a person’s ability to live meaningfully with distress. 19 These cases, treated by ACT to increase psychological flexibility, may support recent research that has suggested a role of reduced psychological flexibility in appearance anxiety.16–18 It also adds to the growing body of evidence suggesting that ACT may be effective in managing distress related to physical health problems.20–25

Given the small number of case studies presented, the results should be treated with some caution. The single case experimental design was not adhered to and the case studies relied on nomothetic measures (questionnaires). As such, future case studies should be conducted using idiographic and patient-specific outcome measures, which would enable detailed analysis of change to be investigated. The current findings are also limited by the uncontrolled nature of the intervention; it is important to acknowledge that the improvements observed in the cases may have been due to other factors that were not measured. In addition, baseline and follow-up data were also not available for all cases, which would have strengthened the results. Furthermore, there are limitations of the WSAS, used to measure functional impairment. This is a brief measure and does not capture all relevant domains that can be affected by appearance anxiety, such as sexual relationships and clothing choices. Finally, clinical experience of the authors suggests that ACT is not effective for some patients experiencing appearance anxiety, and this is typically when patients are not ready to engage in behavioural change and/or are not open to the concept of being willing to feel uncomfortable or distressing emotions. Indeed, readiness is key for engaging in all types of psychological therapy and avoidance (related to emotions, feelings or behaviour) can be a barrier. These aspects need to be explored during clinical assessments and throughout therapy.

Conclusion

The cases presented provide preliminary support for the notion that ACT may be well-suited to some patients with visible differences who are experiencing appearance anxiety and are ready to engage with the concept of reducing their emotional and behavioural avoidance. This readiness can be routinely assessed and ACT provided by clinical psychologists. The ACT intervention did not appear to have any negative effects in the three cases presented. Our study also provides a rationale for conducting a feasibility pilot study to evaluate the effectiveness of ACT for appearance anxiety.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the patients for consenting to the anonymised descriptions of their difficulties and psychological therapy. The authors would also like to acknowledge the patients’ determination and strength throughout therapy.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Laura Shepherd  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0205-6596

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0205-6596

Darren P Reynolds  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9550-8493

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9550-8493

References

- 1. Dalgard FJ, Gieler U, Tomas-Aragones L, et al. The psychological burden of skin diseases: a cross-sectional multicenter study among dermatological outpatients in 13 European countries. J Invest Dermatol 2015; 135: 984–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Clarke A, Thompson AR, Jenkinson E, et al. CBT for appearance anxiety: Psychosocial interventions for anxiety due to visible difference. Chichester: Wiley, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wiechman SA, Patterson DR. Psychosocial aspects of burn injuries. BMJ 2004; 329: 391–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Thompson A, Kent G. Adjusting to disfigurement: processes involved in dealing with being visibly different. Clin Psychol Rev 2001; 21: 663–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rumsey N, Clarke A, White P, et al. Altered body image: appearance-related concerns of people with visible disfigurement. J Adv Nurs 2004; 48: 443–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gibson JAG, Acking E, Bisson JI, et al. The association of affective disorders and facial scarring: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2018; 239: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lawrence JW, Fauerbach JA, Heinberg LJ, et al. Visible vs. hidden scars and their relation to body esteem. J Burn Care Rehabil 2004; 25: 25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Van Loey NEE, Van Son MJM. Psychopathology and psychological problems in patients with burn scars. Am J Clin Dermatol 2003; 4(4): 245–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thombs BD, Notes LD, Lawrence JW, et al. From survival to socialization: A longitudinal study of body image in survivors of severe burn injury. J Psychosom Res 2008; 64: 205–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Esselman PC, Wiechman Askay S, Carrougher GJ, et al. Barriers to return to work after burn injuries. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007; 88(2): 50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thompson AR, Kent G, Smith JA. Living with vitiligo: dealing with difference. Br J Health Psychol 2002; 7: 213–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kornhaber R, Wilson A, Abu-Qamar MZ, et al. Coming to terms with it all: adult burn survivors’ ‘lived experience’ of acknowledgement and acceptance during rehabilitation. Burns 2014; 40: 589–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Clarke A, Thompson AR, Jenkinson E, et al. CBT for appearance anxiety: Psychosocial interventions for anxiety due to visible difference. Chichester: Wiley, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Muftin Z, Thompson AR. A systematic review of self-help for disfigurement: effectiveness, usability, and acceptability. Body Image 2013; 10(4): 442–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Norman A, Moss TP. Psychosocial interventions for adults with visible differences: a systematic review. PeerJ 2015; 3: e870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Montgomery K, Norman P, Messenger AG, et al. The importance of mindfulness in psychosocial distress and quality of life in dermatology patients. Br J Dermatol 2016; 175: 930–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shepherd L, Reynolds DP, Turner A, et al. The role of psychological flexibility in appearance anxiety in people who have experienced a visible burn injury. Burns 2019; 45: 942–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dudek JE, Bialaszek W, Ostaszewski P. Quality of life in women with lipoedema: a contextual behavioral approach. Qual Life Res 2016; 25: 401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hayes SC, Strosahl K, Wilson KG. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Experiential approach to behavior change. New York: Guilford Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20. A-Tjak JGL, Davis ML, Morina N, et al. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of acceptance and commitment therapy for clinically relevant mental and physical health problems. Psychother Psychosom 2015; 84: 30–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rost AD, Wilson K, Buchanan E, et al. Improving psychological adjustment along late-stage ovarian cancer patients: Examining the role of avoidance in treatment. Cognit Behav Pract 2012; 19: 508–517. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wicksell RK, Kemani M, Jensen K, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy for fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Pain 2013; 17: 599–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brassington L, Monteiro da Rocha Bravo Ferreira N, Yates S, et al. Better living with illness: A trans diagnostic acceptance and commitment therapy group intervention for chronic physical illness. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science 2016; 5(4): 208–214. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gregg JA, Callaghan GM, Hayes SC, et al. Improving diabetes self-management through acceptance, mindfulness, and values: A randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2007; 72(2): 336–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lissis J, Hayes SC, Bunting K, et al. Teaching acceptance and mindfulness to improve the lives of the obese: A preliminary test of a theoretical model. Ann Behav Med 2009; 37: 58–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zucchelli F, Donnelly O, Williamson H, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy for people experiencing appearance related distress associated with a visible difference: A rationale and review of relevant research. J Cogn Psychother 2018; 32(3): 171–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Carr T, Moss T, Harris D. The DAS24: a short form of the Derriford Appearance Scale DAS59 to measure individual responses to living with problems of appearance. Br J Health Psychol 2005; 10: 285–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mundt JC, Marks IM, Shear MK, et al. The Work and Social Adjustment Scale: a simple measure of impairment in functioning. Br J Psychiatry 2002; 180: 461–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bond FW, Hayes SC, Baer RA, et al. Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II: a revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behav Ther 2011; 42: 676–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McCracken LM, Chilcot J, Norton S. Further development in the assessment of psychological flexibility: a shortened Committed Action Questionnaire (CAQ-8). Eur J Pain 2015; 19: 677–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

How to cite this article

- Shepherd L, Turner A, Reynolds DP, Thompson AR. Acceptance and commitment therapy for appearance anxiety: Three case studies. Scars, Burns & Healing, Volume 6, 2020. DOI: 10.1177/2059513118967584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]