Abstract

Candida dubliniensis is an opportunistic yeast closely related to Candida albicans that has been recently implicated in oropharyngeal candidiasis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Most manifestations of candidiasis are associated with biofilm formation, with cells in biofilms displaying properties dramatically different from free-living cells grown under normal laboratory conditions. Here, we report on the development of in vitro models of C. dubliniensis biofilms on the surfaces of biomaterials (polystyrene and acrylic) and on the characteristics associated with biofilm formation by this newly described species. Time course analysis using a formazan salt reduction assay to monitor metabolic activities of cells within the biofilm, together with microscopy studies, revealed that biofilm formation by C. dubliniensis occurred after initial focal adherence, followed by growth, proliferation, and maturation over 24 to 48 h. Serum and saliva preconditioning films enhanced the initial attachment of C. dubliniensis and subsequent biofilm formation. Scanning electron microscopy and confocal scanning laser microscopy were used to further characterize C. dubliniensis biofilms. Mature C. dubliniensis biofilms consisted of a dense network of yeasts cells and hyphal elements embedded within exopolymeric material. C. dubliniensis biofilms displayed spatial heterogeneity and an architecture showing microcolonies with ramifying water channels. Antifungal susceptibility testing demonstrated the increased resistance of sessile C. dubliniensis cells, including the type strain and eight different clinical isolates, against fluconazole and amphotericin B compared to their planktonic counterparts. C. dubliniensis biofilm formation may allow this species to maintain its ecological niche as a commensal and during infection with important clinical repercussions.

Candida dubliniensis is a newly described and widely distributed yeast species that is closely related to Candida albicans (12, 14, 20, 30, 34, 36, 37, 47, 55, 59–62). Indeed, C. dubliniensis was initially difficult to distinguish from C. albicans and was often misidentified as such in standard clinical laboratory tests because of phenotypic and genotypic characteristics closely shared with the latter (6, 12, 17, 21, 29, 34, 36, 47, 51, 55, 58, 60). Most C. dubliniensis clinical isolates are susceptible to existing antifungal agents, although the inducibility of fluconazole resistance in vitro has been described (34, 38, 39, 50, 52, 54). Thus, the frequent use of fluconazole prophylaxis may contribute to the emerging role of C. dubliniensis as a pathogen.

C. dubliniensis is a causative agent of oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC) in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected and AIDS patients (12–14, 29, 30, 34, 36, 37, 56, 61, 62). Other forms of mucosal candidiasis are frequently encountered in other patient groups, such as denture wearers, cancer patients, infants, and the elderly (11). In order to colonize and infect the oral environment, yeast cells must first adhere to host cells and tissues or prosthetic materials within the oral cavity or must coaggregate with the oral microbiota (7, 8, 10, 20, 27, 28, 31, 42, 53, 57). In the case of C. dubliniensis these adhesive properties may be facilitated by the intrinsic cell surface hydrophobicity displayed by this organism (26). Initial attachment of cells is followed by proliferation and biofilm formation, with sessile cells in biofilms displaying properties that are dramatically different from their planktonic (free-living) counterparts. Two consequences of biofilm growth with profound clinical implications are the markedly enhanced resistance to antimicrobial agents and protection from host defenses (9, 15, 16, 18, 19, 48, 64). While previous studies of biofilm development and species interaction have focused largely on bacterial species, relatively little is known about fungal biofilms. C. albicans biofilms share several properties with bacterial biofilms, including their structural heterogeneity, the presence of expolymeric material, and their decreased susceptibility to antimicrobial agents and biocides (1–5, 23, 24, 27, 32, 65). However, the ability of C. dubliniensis to form biofilms has not been evaluated. We have previously shown that C. dubliniensis was able to withstand competitive pressure from C. albicans when both species were grown under biofilm-inducing conditions but not when they were grown as planktonic cultures (33). Understanding the biofilm lifestyle is, therefore, critical in relation to therapeutic strategies engaged to treat OPC and related infections, as it is more than likely that microbial biofilms will be the predominant mode of growth. Here, we describe models and characteristics of C. dubliniensis biofilms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms.

Nine isolates of C. dublinenisis were used in the course of this study: eight clinical strains (1154, 1231, 1439, 2419, 3698, 4516, 4572, and 4712), isolated from oropharyngeal samples taken from HIV-infected patients, as previously described by Kirkpatrick et al. (1998), and C. dubliniensis type strain NCPF 3949. All strains were stored on Sabouraud dextrose slopes (BBL, Cockeysville, Md.) at −70°C.

All C. dubliniensis isolates were propagated in yeast-peptone-dextrose (YPD) medium (1% wt/vol yeast extract, 2% wt/vol peptone, 2% wt/vol dextrose [US Biological, Swampscott, Mass.]). Flasks containing liquid medium (20 ml) were inoculated from YPD agar plates containing freshly grown C. dubliniensis and incubated overnight in an orbital shaker at 30°C until the cells had reached a stationary phase of growth. All strains grew in the budding-yeast phase under these conditions. Cells were harvested and washed in sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (10 mM phosphate buffer, 2.7 mM potassium chloride, 137 mM sodium chloride, pH 7.4 [Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.]). Cells were suspended in RPMI-1640 supplemented with l-glutamine, buffered with morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (Angus Buffers and Chemicals, Niagara Falls, N.Y.), and adjusted to the desired cellular density by counting in a hematocytometer (see below).

Biofilm formation on the surface of wells of microtiter plates.

C. dubliniensis biofilms were formed on commercially available presterilized, polystyrene, flat-bottomed, 96-well microtiter plates (Corning Incorporated, Corning, N.Y.). Biofilms were formed by pipetting standardized cell suspensions (100 μl of a suspension containing 5.0 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI-1640) into selected wells of microtiter plates and incubating over a series of time intervals (0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 24, and 48 h) at 37°C. After biofilm formation, the medium was aspirated and nonadherent cells were removed by thoroughly washing the biofilms three times in sterile PBS. A semiquantitative measure of biofilm formation was calculated using a 2,3-bis(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-5-[(phenylamino)carbonyl]-2H-tetrazolium hydroxide (XTT) reduction assay, which measures metabolic activity of cells, essentially as described before (22, 25, 63). Briefly, XTT (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) was prepared as a saturated solution at a concentration of 0.5 g/liter in Ringer's lactate. This solution was filter sterilized through a 0.22-μm-pore-size filter, aliquoted, and stored at −70°C. Prior to each assay, an aliquot of stock XTT was thawed, and menadione (Sigma) added to a final concentration of 1 μM. A 100-μl aliquot of XTT-menadione was then added to each prewashed biofilm and to control wells (to measure background XTT levels). The plates were then incubated in the dark for 1 h at 37°C, and the colorimetric change (a direct reflection of the metabolic activity of the cells within the biofilms) was measured in a microtiter plate reader at 490 nm (Benchmark Microplate Reader; Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). Microscopic examinations of biofilms formed in microtiter plates were performed with light microscopy using an inverted microscope.

Preconditioning films with serum and saliva.

Serum was collected from patients at the University Hospital, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, who tested negatively for both HIV and hepatitis B infection. The serum was pooled, aliquoted, and stored at −70°C. Saliva was collected from several volunteers, who chewed parafilm to stimulate their salivary glands for 1 h, and it was collected in 50-ml Falcon tubes on ice and then centrifuged at 3,000 × g. The saliva was pooled, aliquoted, and stored at −70°C. Serum and saliva were prepared at 50% (vol/vol) in sterile PBS, individually dispensed (50 μl) into six wells of a microtiter plate, and then incubated in the wells overnight at 4°C. Excess serum and saliva were aspirated, and the adsorbed conditioning film was washed once in sterile PBS. C. dubliniensis isolates were washed in PBS, resuspended at a concentration of 108 cells per milliliter in RPMI-1640, and dispensed (100 μl per well) into the 96-well microtiter plates and incubated for 30 min, 4 h, and 24 h at 37°C. For each time point the wells were aspirated and washed three times in sterile PBS, and adhesion was measured by the XTT reduction assay and by light microscopy.

Experiments were performed twice with six replicates for each condition. Results were analyzed by using an unpaired and two-tailed Student t test.

SEM.

For scanning electron microscopy (SEM), biofilms were formed on polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) disks (diameter, 25 mm), which were prepared by combining Dentsply repair material-lucitone Fas-PorE pourable denture base liquid with Dentsply repair material powder (Dentsply International Inc., York, Pa.) at a ratio of 7.5 ml of monomer liquid to 10 g of powder, and mixed thoroughly. The PMMA solution was then quickly poured into Teflon molds and allowed to polymerize into rigid disks. The disks were then washed in sterile distilled H2O to remove toxic monomer residues and sterilized with 70% (vol/vol) alcohol. Biofilms were formed on PMMA discs within six-well cell culture plates (Corning International, Corning, N.Y.) by dispensing standardized cell suspensions (4 ml of a suspension containing 5.0 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI-1640) onto appropriate disks at 37°C. The disks were removed at selected time intervals (2, 4, 6, 8, 24, and 48 h) and washed as described above. The biofilms were then either air dried or placed in a fixative (4% formaldehyde [vol/vol], 1% glutaraldehyde [vol/vol] PBS) overnight. The samples were rinsed in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (2 times, 3 min each) and then placed in 1% Zetterquist's osmium for 30 min. The samples were subsequently dehydrated in a series of ethanol washes (70% for 10 min, 95% for 10 min, and 100% for 20 min), treated (2 times, 5 min each) with hexamethyldisilizane (Polysciences Inc., Warrington, Pa.), and finally air dried in a desiccator. The specimens were coated with gold-palladium (40%/60%). After processing, samples were observed with a scanning electron microscope (Leo 435 VP) in high vacuum mode at 15 kV. The images were processed for display using Photoshop software (Adobe Systems Inc., Mountain View, Calif.).

Confocal Scanning Laser Microscopy (CSLM).

Biofilms were formed as described above for SEM but using 15-mm-diameter plastic coverslips. After incubation at 37°C for different periods of time, they were washed with PBS and stained using the FUN 1 fluorescent cell stain (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.). This product was used here as a nonspecific stain for all cells within the biofilm, with no differentiation between metabolically active and inactive cells. Stained biofilms were observed with an Olympus FV-500 laser scanning confocal microscope, using a 488-nm argon ion laser. Serial sections in the xy plane were obtained at 1-μm intervals along the z axis. Three-dimensional reconstructions of imaged biofilms were obtained by the resident software. The images were processed for display using the Adobe Photoshop program (Adobe).

Antifungal susceptibility testing.

Two clinically used antifungal agents were used in this study, fluconazole (Pfizer, Inc., New York, N.Y.) and amphotericin B (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, N.J.). Fluconazole and amphotericin B were prepared at stock concentrations of 1,024 μg/ml in RPMI-1640 (Angus Buffers and Chemicals) and antibiotic medium 3 (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.), respectively. Antifungal susceptibility testing to determine MICs for planktonic cells was performed by using the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) M-27A broth microdilution method with reading of endpoints at 48 h (41). For antifungal susceptibility testing of sessile (biofilm) cells, biofilms were formed by pipetting standardized cell suspensions (100 μl) into selected wells of the microtiter plate, as described above, which were then incubated for 48 h at 37°C. The biofilms were then washed thoroughly three times with sterile PBS before the addition of antifungal agents in serially double-diluted concentrations and incubated for a further 48 h at 37°C. A series of antifungal free wells was also included to serve as controls. MICs for sessile cells were determined at 50% inhibition (SMIC50) and at 80% inhibition (SMIC80) compared to results with drug-free control wells using the XTT reduction assay described above.

RESULTS

In vitro biofilm formation by C. dubliniensis.

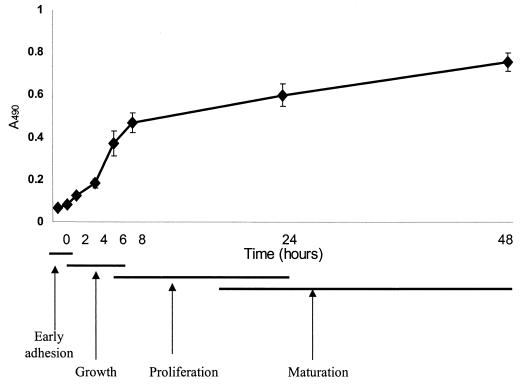

The kinetics of biofilm formation by the C. dubliniensis type strain on the surface of polystyrene wells over 48 h as revealed by the colorimetric XTT formazan salt reduction assay is illustrated in Fig. 1. The metabolic activity of cells in the biofilm increased over time as the cellular mass increased. The biofilms were highly metabolically active in the first 8 h. However, as the biofilm matured and the complexity increased (24 to 48 h), the metabolic activity reached a plateau but remained high, which reflected the increased number of cells that constituted the mature biofilm. Experiments were performed in sets of eight replicates on three separate occasions, with similar results obtained in all experiments.

FIG. 1.

Kinetics of C. dubliniensis NCPF 3949 biofilm formation as determined by XTT readings. The different phases of biofilm development according to both colorimetric readings and microscopic observations are indicated.

Light microscopy was used in conjunction with this semiquantitative method to monitor biofilm formation and morphological characteristics of adhered cells. At 30 min, adherent budding yeast cells were observed sticking to the wells in a random manner (the origins of microcolonies). Germ tube formation occurred within 2 h, and the presence of filamentous forms was noticeable at 4 and 6 h. After 8 h of adhesion a monolayer of yeast cells, germ tubes, hyphae, and pseudohyphae was observed covering the entire surface of the well. As the biofilm matured after 24 and 48 h of growth, the complexity of the biofilm increased into a multilayered biofilm matrix, with all fungal morphologies being present in the final biofilm structure.

The kinetics of biofilm formation by the different clinical isolates showed a pattern similar to that of the type strain. However, in relation to their metabolic activities and individual propensity to adhere to the polystyrene wells, strain variations were detected (results not shown).

Effect of serum and saliva conditioning films on C. dubliniensis adhesion and biofilm formation.

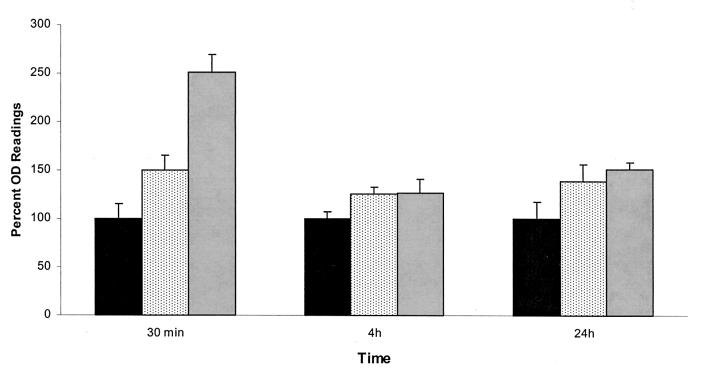

The effect of serum and saliva conditioning films on C. dubliniensis adherence and biofilm formation is shown in Fig. 2. When serum was provided as a conditioning film, the level of C. dublinienisis adherence was significantly elevated in comparison to that observed in untreated wells. The effect was most clearly demonstrated during early adherence at 30 min (P < 0.0001). After 4 and 24 h a smaller difference was observed between biofilm formation in the presence and absence of the serum pellicle, but differences were still statistically significant (P = 0.0003 and 0.0001, respectively). This pattern of adherence was observed consistently for two other strains examined (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Effect of serum and saliva preconditioning films on the formation of C. dubliniensis NCPF 3949 biofilms. Values are expressed as average percent optical density readings for XTT assays compared to those for control wells (considered 100%). Error bars represent standard errors of the means. Results are from a single experiment performed with six replicate wells. ■, Control;  , saliva;

, saliva;  , serum.

, serum.

When saliva was provided as a conditioning film, the level of adherence of C. dubliniensis was elevated in comparison to results with polystyrene. In contrast to the case with serum, the effect was marginally increased at 30 min (P = 0.0185). However, after 4 and 24 h there was a larger increase in biofilm metabolic activity (P = 0.0002 and < 0.0001, respectively), comparable to that observed in the presence of serum pellicle. The effect of saliva conditioning films on adherence was generally lower than that of serum; however, a general trend in increased adherence and biofilm formation was equally observed. Overall the results showed that biological conditioning films help provide receptor binding sites for planktonic C. dublinienis.

SEM and CSLM visualization of C. dubliniensis biofilms.

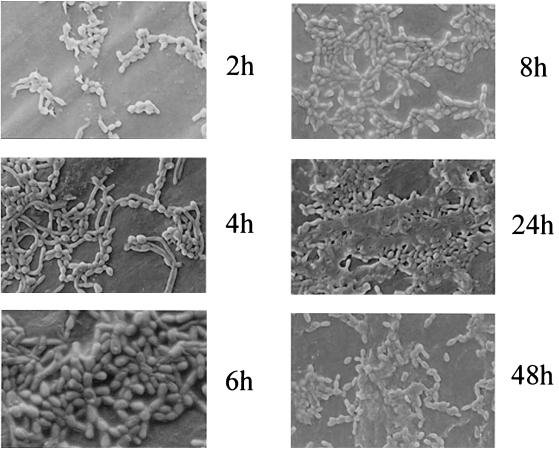

Biofilm formation by C. dubliniensis on acrylic discs was monitored by SEM (Fig. 3 and 4). Despite its destructive nature, SEM observations provided useful information on the different cellular morphologies present in the biofilm structure. Initial adherence of yeast cells was followed by germ tube formation and subsequent development of hyphae (Fig. 3). Mature biofilms consisted of a dense network of cells of all morphologies, deeply embedded in a matrix consisting of expolymeric material, which was better preserved when the biofilm samples were air dried (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

SEM images of C. dubliniensis NCPF 3949 biofilm formation on PMMA disks over various time intervals (2, 4, 6, 8, 24 and 48 h). Biofilm samples were not fixed to maximize the preservation of exopolymeric material.

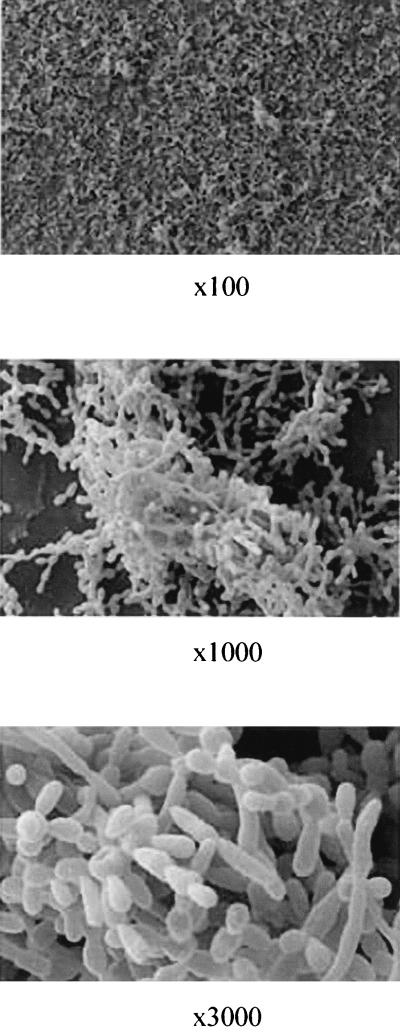

FIG. 4.

SEM images of mature (48-h) C. dubliniensis NCPF 3949 biofilms formed on PMMA. The same biofilm area is shown at different magnifications. Samples were fixed prior to processing for SEM.

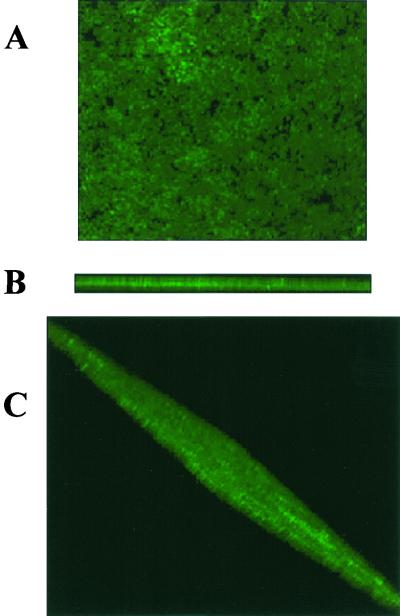

The noninvasive CSLM technique enabled imaging of intact biofilms and visualization of the three-dimensional distribution of labeled C. dubliniensis cells in the context of the complex biofilm community. Significant channeling and porosity were also observed. Overall, results indicated that mature C. dubliniensis biofilms displayed a typical microcolony/water channel architecture with extensive spatial heterogeneity. Figure 5 shows a three-dimensional reconstruction of a 24-h-old, 40-μm-thick C. dubliniensis biofilm resulting from the compilation of a series of individual xy sections taken across the z axis.

FIG. 5.

Three-dimensional reconstruction of a 24-h C. dubliniensis NCPF 3949 biofilm using confocal microscopy and the associated software for the compilation of xy optical sections taken across the z axis. (A) View from the top. (B) Cross-section to show depth of the biofilm (approximately 40 μm). (C) Rotated view to provide a global biofilm perspective.

Susceptibility testing of C. dubliniensis biofilms against clinically used antifungal agents.

The in vitro activity of clinically used fluconazole and amphotericin B against preformed C. dubliniensis biofilms was assessed using the modified XTT assay. Experiments revealed the increased resistance of sessile C. dubliniensis cells. The results, expressed as SMIC50s and SMIC80s, are presented in Table 1. Data revealed that C. dubliniensis biofilms were intrinsically resistant to fluconazole. Amphotericin B demonstrated certain activity against C. dubliniensis biofilms, as indicated by SMIC50s. However SMIC80s were substantially increased (up to 64-fold higher than the corresponding MICs) and already fell within the resistant range for this antifungal agent (>1 μg/ml).

TABLE 1.

Antifungal agent susceptibility testing of sessile (biofilm) and planktonic cells from different C. dubliniensis isolates with amphotericin B and fluconazole

| Isolate | Results (μg/ml) for:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amphotericin B

|

Fluconazole

|

|||||

| Planktonic MIC (NCCLS) | SMIC50 | SMIC80 | Planktonic MIC (NCCLS) | SMIC50 | SMIC80 | |

| 1154 | 0.25 | 0.0625 | 1 | 2 | >1,024 | >1,024 |

| 1231 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 4 | 0.5 | >1,024 | >1,024 |

| 1439 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 2 | 1 | >1,024 | >1,024 |

| 2419 | 0.125 | 0.0625 | 4 | 0.25 | >1,024 | >1,024 |

| 3698 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 4 | 16 | >1,024 | >1,024 |

| 4516 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 8 | 4 | 1,024 | >1,024 |

| 4572 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 4 | 64 | >1,024 | >1,024 |

| 4712 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 8 | 64 | >1,024 | >1,024 |

| NCPF 3949 | 0.125 | 0.0625 | 8 | 0.25 | >1,024 | >1,024 |

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated the ability of C. dubliniensis to adhere to and form biofilms on the surfaces of different biomaterials. A semiquantitative colorimetric method based on XTT reduction allowed monitoring of the different stages in biofilm formation on the wells of microtiter plates. The presence of serum or salivary pellicles, which are normally found in the oral environment and may provide binding sites for Candida (8, 10), increased the initial adherence of C. dubliniensis cells to biomaterials and subsequent biofilm formation. Other investigators have previously shown that the presence of serum and salivary pellicles can potentiate C. albicans colonization of acrylic strips and denture lining materials (41–46).

SEM techniques revealed that similar to C. albicans biofilms (5, 23), mature C. dubliniensis biofilms consist of a mixture of yeast and filamentous forms embedded within exopolymeric material. The exopolymeric material was better preserved when biofilm preparations were air dried, whereas in fixed biofilms only its remains were visible attached to the surfaces of the cells (Fig. 3 and 4). The nondestructive CSLM technique (Fig. 5) allowed in situ visualization of hydrated biofilms and demonstrated that C. dubliniensis biofilms possess structural heterogeneity and display a typical microcolony/water channel architecture similar to what has been described for bacterial biofilms (49, 64). This structure may represent an optimal arrangement for the influx of nutrients, disposal of waste products, and establishment of microniches throughout the biofilm (15, 16).

Currently there is a method well described by the NCCLS (M-27A) for determining antifungal susceptibilities for yeast planktonic cultures (40). Nevertheless, the susceptibility data generated from this approach do not account for the intrinsic resistance exhibited by sessile cells. For example, Hawser and Douglas (24) reported that a range of antifungal agents were between 30 and 2,000 times less active against C. albicans biofilms than against planktonic cultures as measured by MICs. In agreement with these observations, here we have demonstrated the intrinsic resistance of C. dubliniensis biofilms to fluconazole, the most commonly used antifungal agent for the treatment of OPC, and their increased resistance to clinically used amphotericin B. Although amphotericin B exhibited a certain degree of activity against biofilms as indicated by SMIC50s, the SMIC80s, all above 1 μg/ml, already fell into the range indicating resistance according to interpretative break points (41). Although these concentrations represent obtainable drug levels, the intrinsic toxicity displayed by this agent will preclude its use at such a high dose. Moreover, even at higher concentrations (up to 16 μg/ml) sterility was never achieved. Factors that may be responsible for the increased resistance of microbial biofilms include restricted penetration of antimicrobials due to the exopolymeric material, a decreased growth rate (physiological status) of cells within the biofilm, and differential gene expression. An interesting possibility to explain biofilm resistance has been proposed recently by Lewis, that is that the majority of cells within the biofilm are not necessarily more resistant to killing than planktonic cells, but rather a few persisters survive and are actually preserved by antibiotic pressure (35). Overall, the disparity between MICs for planktonic and sessile cultures from an identical isolate may, therefore, explain why antifungal treatment may be ineffective in some instances and may partially explain the lack of an absolute correlation between clinical (in vivo) and mycological (in vitro) resistance.

The ability of C. dubliniensis to form biofilms may confer on this microorganism an ecological advantage in trying to maintain its niche as a commensal and pathogen of humans by evading host immune mechanisms, resisting antifungal treatment, and better withstanding the competitive pressure from other oral microorganisms. Fungal biofilms may also serve as a safe reservoir for the release of infecting cells into the oral environment. Thus, biofilm formation in C. dubliniensis may represent a key factor for the survival of this species, which seems to be particularly well adapted to colonization of the oral cavity, with important clinical repercussions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant ATP 3659-0080 from the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board (Advance Technology Program, Biomedicine). J.L.L.-R. is the recipient of a New Investigator Award in Molecular Pathogenic Mycology from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

We thank T. F. Patterson for C. dubliniensis clinical isolates. We thank Peggy Miller and Victoria Frohlich (Depts of Pathology and Cellular and Structural Biology) for assistance in SEM and CSLM experiments, respectively.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baillie G S, Douglas L J. Candida biofilms and their susceptibility to antifungal agents. Methods Enzymol. 1999;310:644–656. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)10050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baillie G S, Douglas L J. Effect of growth rate on resistance of Candida albicans biofilms to antifungal agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1900–1905. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baillie G S, Douglas L J. Iron-limited biofilms of Candida albicans and their susceptibility to amphotericin B. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2146–2149. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baillie G S, Douglas L J. Matrix polymers of Candida biofilms and their possible role in biofilm resistance to antifungal agents. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;46:397–403. doi: 10.1093/jac/46.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baillie G S, Douglas L J. Role of dimorphism in the development of Candida albicans biofilms. J Med Microbiol. 1999;48:671–679. doi: 10.1099/00222615-48-7-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bikandi J, Millan R S, Moragues M D, Cebas G, Clarke M, Coleman D C, Sullivan D J, Quindos G, Ponton J. Rapid identification of Candida dubliniensis by indirect immunofluorescence based on differential localization of antigens on C. dubliniensis blastospores and Candida albicans germ tubes. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2428–2433. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2428-2433.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Busscher H J, Geertsema-Doornbusch G I, van der Mei H C. Adhesion to silicone rubber of yeasts and bacteria isolated from voice prostheses: influence of salivary conditioning films. J Biomed Mater Res. 1997;34:201–209. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199702)34:2<201::aid-jbm9>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cannon R D, Chaffin W L. Oral colonization by Candida albicans. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1999;10:359–383. doi: 10.1177/10454411990100030701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlsson J. Bacterial metabolism in dental biofilms. Adv Dent Res. 1997;11:75–80. doi: 10.1177/08959374970110012001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaffin W L, Lopez-Ribot J L, Casanova M, Gozalbo D, Martinez J P. Cell wall and secreted proteins of Candida albicans: identification, function, and expression. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:130–180. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.1.130-180.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Challacombe S J. Immunologic aspects of oral candidiasis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;78:202–210. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(94)90148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coleman D, Sullivan D, Harrington B, Haynes K, Henman M, Shanley D, Bennett D, Moran G, McCreary C, O'Neill L. Molecular and phenotypic analysis of Candida dubliniensis: a recently identified species linked with oral candidosis in HIV-infected and AIDS patients. Oral Dis. 1997;3(Suppl. 1):S96–S101. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1997.tb00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coleman D C, Rinaldi M G, Haynes K A, Rex J H, Summerbell R C, Anaissie E J, Li A, Sullivan D J. Importance of Candida species other than Candida albicans as opportunistic pathogens. Med Mycol. 1998;36(Suppl. 1):156–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coleman D C, Sullivan D J, Mossman J M. Candida dubliniensis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:3011–3012. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.3011-3012.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costerton J W, Lewandowski Z, Caldwell D E, Korber D R, Lappin-Scott H M. Microbial biofilms. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:711–745. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.003431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costerton J W, Stewart P S, Greenberg E P. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999;284:1318–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gales A C, Pfaller M A, Houston A K, Joly S, Sullivan D J, Coleman D C, Soll D R. Identification of Candida dubliniensis based on temperature and utilization of xylose and alpha-methyl-d-glucoside as determined with the API 20C AUX and vitek YBC systems. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3804–3808. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.3804-3808.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gander S. Bacterial biofilms: resistance to antimicrobial agents. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:1047–1050. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.6.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilbert P, Das J, Foley I. Biofilm susceptibility to antimicrobials. Adv Dent Res. 1997;11:160–167. doi: 10.1177/08959374970110010701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilfillan G D, Sullivan D J, Haynes K, Parkinson T, Coleman D C, Gow N A. Candida dubliniensis: phylogeny and putative virulence factors. Microbiology. 1998;144:829–838. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-4-829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hannula J, Saarela M, Alaluusua S, Slots J, Asikainen S. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of oral yeasts from Finland and the United States. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1997;12:358–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1997.tb00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hawser S. Adhesion of different Candida spp. to plastic: XTT formazan determinations. J Med Vet Mycol. 1996;34:407–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawser S P, Douglas L J. Biofilm formation by Candida species on the surface of catheter materials in vitro. Infect Immun. 1994;62:915–921. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.3.915-921.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hawser S P, Douglas L J. Resistance of Candida albicans biofilms to antifungal agents in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2128–2131. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.9.2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hawser S P, Norris H, Jessup C J, Ghannoum M A. Comparison of a 2,3-bis(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-5-[(phenylamino)carbonyl]-2H-tetrazolium hydroxide (XTT) colorimetric method with the standardized National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards method of testing clinical yeast isolates for susceptibility to antifungal agents. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1450–1452. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.5.1450-1452.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hazen K C, Wu J G, Masuoka J. Comparison of the hydrophobic properties of Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis. Infect Immun. 2001;69:779–786. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.2.779-786.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holmes A R, Cannon R D, Jenkinson H F. Interactions of Candida albicans with bacteria and salivary molecules in oral biofilms. J Ind Microbiol. 1995;15:208–213. doi: 10.1007/BF01569827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jabra-Rizk M A, Falkler W A, Merz W G, Kelley J I, Baqui A A A M, Meiller T F. Candida dubliniensis and Candida albicans display surface variations consistent with observed intergeneric coaggregation. Rev Iberoam Micol. 1999;16:187–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jabra-Rizk M A, Baqui A A, Kelley J I, Falkler W A, Jr, Merz W G, Meiller T F. Identification of Candida dubliniensis in a prospective study of patients in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:321–326. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.2.321-326.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jabra-Rizk M A, Falkler W A, Jr, Merz W G, Baqui A A, Kelley J I, Meiller T F. Retrospective identification and characterization of Candida dubliniensis isolates among Candida albicans clinical laboratory isolates from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected and non-HIV-infected individuals. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2423–2426. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.6.2423-2426.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jabra-Rizk M A, Falkler W A, Jr, Merz W G, Kelley J I, Baqui A A, Meiller T F. Coaggregation of Candida dubliniensis with Fusobacterium nucleatum. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1464–1468. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.5.1464-1468.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalya A V, Ahearn D G. Increased resistance to antifungal antibiotics of Candida spp. adhered to silicone. J Ind Microbiol. 1995;14:451–455. doi: 10.1007/BF01573956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirkpatrick W R, Lopez-Ribot J L, McAtee R K, Patterson T F. Growth competition between Candida dubliniensis and Candida albicans under broth and biofilm growing conditions. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:902–904. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.2.902-904.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirkpatrick W R, Revankar S G, McAtee R K, Lopez-Ribot J L, Fothergill A W, McCarthy D I, Sanche S E, Cantu R A, Rinaldi M G, Patterson T F. Detection of Candida dubliniensis in oropharyngeal samples from human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients in North America by primary CHROMagar Candida screening and susceptibility testing of isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3007–3012. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.3007-3012.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis K. Riddle of biofilm resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:999–1007. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.4.999-1007.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCullough M J, Clemons K V, Stevens D A. Molecular and phenotypic characterization of genotypic Candida albicans subgroups and comparison with Candida dubliniensis and Candida stellatoidea. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:417–421. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.2.417-421.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meiller T F, Jabra-Rizk M A, Baqui A, Kelley J I, Meeks V I, Merz W G, Falkler W A. Oral Candida dubliniensis as a clinically important species in HIV-seropositive patients in the United States. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;88:573–580. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(99)70088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moran G P, Sanglard D, Donnelly S M, Shanley D B, Sullivan D J, Coleman D C. Identification and expression of multidrug transporters responsible for fluconazole resistance in Candida dubliniensis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1819–1830. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.7.1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moran G P, Sullivan D J, Henman M C, McCreary C E, Harrington B J, Shanley D B, Coleman D C. Antifungal drug susceptibilities of oral Candida dubliniensis isolates from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected and non-HIV-infected subjects and generation of stable fluconazole-resistant derivatives in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:617–623. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.3.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts: approved standard. NCCLS Document M27-A. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nikawa H, Hamada T, Yamamoto T, Kumagai H. Effects of salivary or serum pellicles on the Candida albicans growth and biofilm formation on soft lining materials in vitro. J Oral Rehabil. 1997;24:594–604. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.1997.00539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nikawa H, Hayashi S, Nikawa Y, Hamada T, Samaranayake L P. Interactions between denture lining material, protein pellicles and Candida albicans. Arch Oral Biol. 1993;38:631–634. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(93)90132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nikawa H, Jin C, Hamada T, Makihira S, Kumagai H, Murata H. Interactions between thermal cycled resilient denture lining materials, salivary and serum pellicles and Candida albicans in vitro. Part II. Effects on fungal colonization. J Oral Rehabil. 2000;27:124–130. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2000.00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nikawa H, Nishimura H, Hamada T, Kumagai H, Samaranayake L P. Effects of dietary sugars and saliva and serum on Candida biofilm formation on acrylic surfaces. Mycopathologia. 1997;139:87–91. doi: 10.1023/a:1006851418963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nikawa H, Nishimura H, Hamada T, Yamashiro H, Samaranayake L P. Effects of modified pellicles on Candida biofilm formation on acrylic surfaces. Mycoses. 1999;42:37–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0507.1999.00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nikawa H, Nishimura H, Makihira S, Hamada T, Sadamori S, Samaranayake L P. Effect of serum concentration on Candida biofilm formation on acrylic surfaces. Mycoses. 2000;43:139–143. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0507.2000.00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Odds F C, Van Nuffel L, Dams G. Prevalence of Candida dubliniensis isolates in a yeast stock collection. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2869–2873. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.2869-2873.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O'Toole G A, Pratt L A, Watnick P I, Newman D K, Weaver V B, Kolter R. Genetic approaches to study of biofilms. Methods Enzymol. 1999;310:91–109. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)10008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palmer R J, Jr, Sternberg C. Modern microscopy in biofilm research: confocal microscopy and other approaches. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1999;10:263–268. doi: 10.1016/S0958-1669(99)80046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pfaller M A, Messer S A, Gee S, Joly S, Pujol C, Sullivan D J, Coleman D C, Soll D R. In vitro susceptibilities of Candida dubliniensis isolates tested against the new triazole and echinocandin antifungal agents. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:870–872. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.3.870-872.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pinjon E, Sullivan D, Salkin I, Shanley D, Coleman D. Simple, inexpensive, reliable method for differentiation of Candida dubliniensis from Candida albicans. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2093–2095. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.7.2093-2095.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Quindos G, Carrillo-Munoz A J, Arevalo M P, Salgado J, Alonso-Vargas R, Rodrigo J M, Ruesga M T, Valverde A, Peman J, Canton E, Martin-Mazuelos E, Ponton J. In vitro susceptibility of Candida dubliniensis to current and new antifungal agents. Chemotherapy. 2000;46:395–401. doi: 10.1159/000007320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Radford D R, Sweet S P, Challacombe S J, Walter J D. Adherence of Candida albicans to denture-base materials with different surface finishes. J Dent. 1998;26:577–583. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(97)00034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ruhnke M, Schmidt-Westhausen A, Morschhauser J. Development of simultaneous resistance to fluconazole in Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis in a patient with AIDS. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;46:291–295. doi: 10.1093/jac/46.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schoofs A, Odds F C, Colebunders R, Ieven M, Goossens H. Use of specialised isolation media for recognition and identification of Candida dubliniensis isolates from HIV-infected patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;16:296–300. doi: 10.1007/BF01695634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schorling S R, Kortinga H C, Froschb M, Muhlschlegel F A. The role of Candida dubliniensis in oral candidiasis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2000;26:59–68. doi: 10.1080/10408410091154183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sen B H, Safavi K E, Spangberg L S. Colonization of Candida albicans on cleaned human dental hard tissues. Arch Oral Biol. 1997;42:513–520. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(97)00026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Staib P, Morschhauser J. Chlamydospore formation on Staib agar as a species-specific characteristic of Candida dubliniensis. Mycoses. 1999;42:521–524. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0507.1999.00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sullivan D, Coleman D. Candida dubliniensis: an emerging opportunistic pathogen. Curr Top Med Mycol. 1997;8:15–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sullivan D, Coleman D. Candida dubliniensis: characteristics and identification. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:329–334. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.329-334.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sullivan D, Haynes K, Bille J, Boerlin P, Rodero L, Lloyd S, Henman M, Coleman D. Widespread geographic distribution of oral Candida dubliniensis strains in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:960–964. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.960-964.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sullivan D J, Westerneng T J, Haynes K A, Bennett D E, Coleman D C. Candida dubliniensis sp. nov.: phenotypic and molecular characterization of a novel species associated with oral candidosis in HIV-infected individuals. Microbiology. 1995;141:1507–1521. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-7-1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tellier R, Krajden M, Grigoriew G A, Campbell I. Innovative endpoint determination system for antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1619–1625. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.8.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Watnick P, Kolter R. Biofilm, city of microbes. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2675–2679. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.10.2675-2679.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Webb B C, Willcox M D, Thomas C J, Harty D W, Knox K W. The effect of sodium hypochlorite on potential pathogenic traits of Candida albicans and other Candida species. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1995;10:334–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1995.tb00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]