Abstract

Purpose of review

Effective ways to diagnose the remaining people living with HIV who do not know their status are a global priority. We reviewed the use of risk-based tools, a set of criteria to identify individuals who would not otherwise be tested (screen in) or excluded people from testing (screen out).

Recent findings

Recent studies suggest that there may be value in risk-based tools to improve testing efficiency (i.e. identifying those who need to be tested). However, there has not been any systematic reviews to synthesize these studies.

Summary

We identified 18,238 citations, and 71 were included. The risk-based tools identified were most commonly from high-income (51%) and low HIV (<5%) prevalence countries (73%). The majority were for “screening in” (70%), with the highest performance tools related to identifying MSM with acute HIV. Screening in tools may be helpful in settings where it is not feasible or recommended to offer testing routinely. Caution is needed for screening out tools, where there is a trade-off between reducing costs of testing with missing cases of people living with HIV.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11904-022-00601-5.

Keywords: HIV, Testing, Screening tool

Introduction

Globally, an estimated 6.0 million people living with HIV (PLHIV) remain unaware of their status, approximately 16% of the total population of PLHIV [1]. This gap in knowledge of HIV status is a significant public health problem, whereby those living with HIV who are not linked to appropriate treatment and care have higher HIV-related mortality and morbidity [2]. Finding effective and efficient ways to close this testing gap is an urgent global priority.

As nations strive to meet United Nation’s (UN) 95-95-95 testing and treatment targets—with the first target referring to having 95% of PLHIV diagnosed and aware of their status by 2025 [3]—efforts to reach the remaining undiagnosed individuals is challenging and costly. As countries successfully control the HIV epidemic, HIV positivity (or yield) may decline in parallel with increases in testing and treatment coverage, thereby increasing the cost per person diagnosed. Countries also need to make testing more efficient in light of HIV funding in low-and-middle-income countries stalling and decreasing since 2017, with further disruption of services as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic [4]. Strategic use of HIV testing services (HTS) approaches, including partner services [5], community-based testing [6••], and HIV self-testing [7, 8], focused on geographic areas, and populations with the greatest HIV burden and unmet testing need have proven effective and efficient in reaching people with undiagnosed HIV infection.

Another strategy to consider is using risk-based screening tools in HIV testing services. Risk-based screening tools typically use a set of criteria to either identify high-risk individuals for HIV testing who would not otherwise be offered a test (screen in) or exclude low-risk people from a routine offer of the test (screen out). Tools may be electronic or paper-based and can be self or provider-administered in inpatient [9, 10] and outpatient clinics [11], primary care or community settings [12]. A tool may use a combination of demographics, risk behaviours, clinical examination findings, HIV indicator conditions or presenting symptoms to ascertain the risk of HIV in the individual and suggest whether an HIV test should be offered. Currently, it is uncertain how widely used the tools are, whether tools are validated, which tools are used for what populations and how feasible and acceptable tools are to patients and providers. To date, results have varied; some programmatic implementation of screening tools suggests increased yield and positivity [6••, 13••, 14], while other reports raise concerns that these screening tools may mean people with undiagnosed HIV are not tested and missed due to limited criteria [15–17].

This study aims to use a systematic review and global survey of HTS implementers to describe which risk-based tools are used in what settings and populations, and how they perform in relation to their potential risks and benefits.

Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria for the Systematic Literature Review

We searched Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, Web of Science, and Global Health Search between 1st and 9th July 2020. The search terms used two key concepts: “HIV”, and “Risk assessments or screening tools.” The complete search strategy is presented in Appendix 1. The inclusion criteria were any study published from 1st January 2010 and contained primary data about using screening tools to optimise HTS. We excluded systematic literature reviews, letters, editorials, and duplicated results from the same study. The primary outcome of interest was the performance of the risk-based screening tool in terms of its sensitivity and specificity in diagnosing HIV, and the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve [18]. Secondary outcomes included [1] external validation (i.e. testing the performance of the tool in individuals who are not the same as the development cohort); [2] characteristics of screening tools—number and type of questions, time to complete, self/provider administered, electronic/paper, self-report/clinic record based; [3] use of tool to select (screen in) or exclude (screen out) individuals from the offer of testing; [4] settings where the tool is used; [5] whether tools are being monitored; [6••] feasibility of implementing the tool, e.g. time needed to administer, impact on patient and throughput; and [7] economic evaluation.

Titles and abstracts were independently assessed for eligibility by at least two reviewers (KC, TN, MT). Another reviewer (JO) resolved any discrepancies. This systematic review has been registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO: CRD42020187838).

Data Analysis

An extraction file was created in Microsoft Excel to collect the relevant information as per the primary and secondary outcomes outlined above. Data extraction was conducted by at least two reviewers (KC, TN, MT), and another reviewer (JO) resolved any discrepancies. The quality of each study was assessed using the appropriate critical appraisal tool from Johanna Briggs Institute [19].

Statistical Analysis

Where available, we ranked the area under the ROC curve (AUC) from screening tools according to subpopulations (women, MSM, paediatrics) and settings (primary care, emergency department). A country with a high HIV prevalence was a national prevalence above 5%, as reported by UNAIDS [20]. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 16 (StataCorp. 2019. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC). This review is reported per Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Role of the Funding Source

The funders did not have any role in the study design; collection, analysis or interpretation of the data; writing the report or decision to submit the paper for publication.

Patient and Public Involvement

The study did not involve any patient participation. Our preliminary findings were presented at two WHO meetings on “Optimizing HIV Testing Services Using HIV Risk Assessment Tools” (11–13th November 2020 and 1st June 2021) where the public could register to attend and provide feedback.

Results

Systematic Review Results

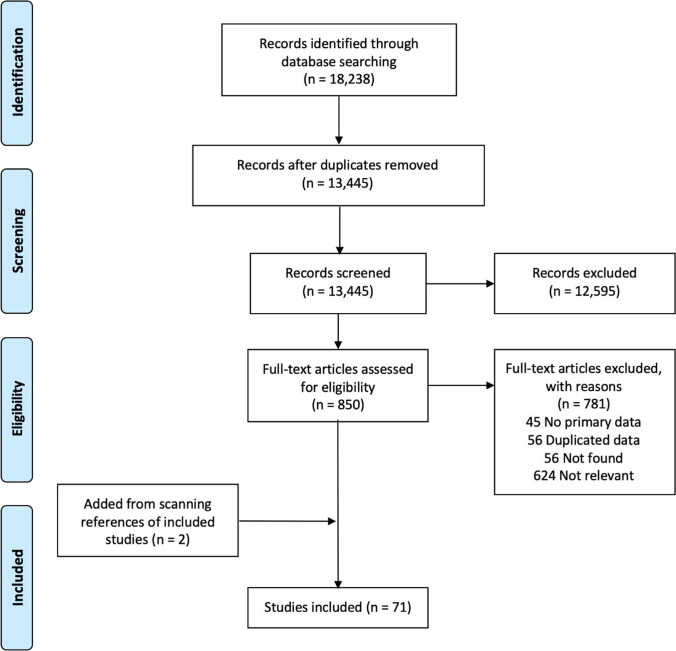

The initial search identified 18,238 potential manuscripts. After removing duplicates, the titles and abstracts of 13,445 records were searched for relevance of the study objectives. We removed 12,595 records as they did not meet the study inclusion criteria. Full texts of 850 articles were assessed, with 71 included in the final analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

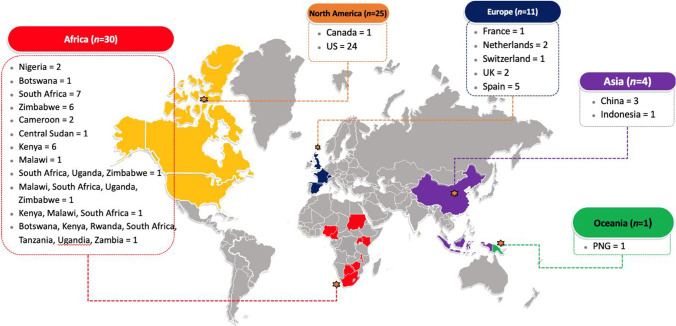

Figure 2 summarises the countries where the risk-based HIV screening tools were reported. Most studies arose from Africa (42%), followed by North America (35%), Europe (15%), Asia (6%), and Oceania (1%).

Fig. 2.

Countries of studies with an evaluation of HIV risk-based tools (N=71)

Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the included studies according to the country’s HIV burden. Most tools were used in high- and middle-income countries, in primary care settings, for MSM and paediatric populations, and primarily administered by the provider. The majority of risk-based screening tools were for screening in.

Table 1.

Study characteristics, according to HIV prevalence [21]

|

Total (N=71) |

Low HIV prevalence1 (N=52) | High HIV prevalence1 (N=19) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country income level* | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| High | 36 (51) | 36 (69) | 0 (0) |

| Middle | 33 (46) | 15 (29) | 18 (95) |

| Low | 6 (8) | 1 (2) | 5 (26) |

| Settings | |||

| Primary care | 17 (24) | 7 (13) | 10 (53) |

| Hospital | 13 (18) | 10 (19) | 3 (16) |

| Emergency department | 11 (15) | 11 (21) | 0 (0) |

| Community | 8 (11) | 8 (15) | 0 (0) |

| STI clinic | 5 (7) | 4 (8) | 1 (5) |

| Antenatal or maternity ward | 4 (6) | 1 (2) | 3 (16) |

| Prisons | 2 (3) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Populations | |||

| MSM | 15 (21) | 15 (29) | 0 (0) |

| Paediatrics | 14 (20) | 6 (12) | 8 (42) |

| Primary care attendees | 11 (15) | 11 (21) | 0 (0) |

| Emergency department attendees | 11 (15) | 11 (21) | 0 (0) |

| Women | 8 (11) | 1 (2) | 7 (37) |

| Hospital inpatients | 6 (8) | 5 (10) | 1 (5) |

| Adults in the community | 3 (4) | 1 (2) | 2 (11) |

| STI clinic attendees | 3 (4) | 2 (4) | 1 (5) |

| Incarcerated persons | 2 (3) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Serodiscordant couples | 2 (3) | 1 (2) | 1 (5) |

| People who inject drugs | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Female sex workers | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

| Tool administered by | |||

| Patient | 13 (18) | 6 (12) | 7 (37) |

| Provider | 42 (52) | 26 (50) | 16 (84) |

| Type of tool | |||

| Screening in | 50 (70) | 38 (73) | 12 (63) |

| Screening out | 21 (30) | 14 (27) | 7 (37) |

*Some studies contain more than one country, so the denominator may not add up to 71. The number of missing studies is not shown

1High HIV prevalence is defined as ≥5%, and low HIV prevalence is defined as <5%

Table 2 summarises the risk-based tools for MSM. All tools were used to “screen in”. Most had been externally validated (13/15) and used in various settings. The tools with the highest AUC related to identifying men with acute HIV in Kenya (0.89) [22], the Netherlands (0.88) [13••], and the USA (0.85) [23]. The use of these tools helped allocate more costly diagnostics to those who are more likely to have acute HIV. Acute HIV was defined by a positive HIV-1 RNA or p24 antigen test and two negative rapid antibody tests or ELISA assays, followed by documented antibody seroconversion. Tools with the highest sensitivity were related to identifying HIV among MSM in Kenya (98% [24], 90% [22]), and MSM in the USA (84%) [25]. The tools with the highest specificity related to identifying men with acute HIV in the US (96% [23], 81% [13••]), and the Netherlands (78% [26••]). The most common domain used in the tools was the risk behaviours (Supplementary Table 1). The average number of items within a tool was 6.6 (range 4–12).

Table 2.

Risk-based screening tools for men who have sex with men ordered by performance ordered by the area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC)

| Lead Author (year of publication) | Year(s) of data | Sample size | Country | Setting | Externally validated? | AUC (95% CI) | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanders (2015) [22] | 2005-12 | Unclear | Kenya | Health facilities | Yes | 0.89 | 90% | 74.1% |

| Lin (2018) [13••] | 2007-17 | 757 | USA | Community-based screening program | Yes | 0.88 (0.84-0.91) | 78.2% | 81% |

| Lin (2018) [23] | 2007-17 | 998 | USA | Community-based screening program | Yes | 0.85 (0.78-0.92) | 72% | 96% |

| Dijkstra (2017) [27] | 1984-2009 | 1562 | Netherlands | STI clinic | Yes | 0.82 (0.79-0.86) | 76.3% (68.2-83.2) | 76.3% (75.6-77.0) |

| Scott (2020) [28] | 2009-10 | 1164 | US | Community | Yes | 0.8 | 81.1% | 59.6% |

| Wahome (2013) [29] | 2005-2012 | 6531 | Kenya | Unclear | Yes | 0.79 | 75.3% | 76.4% |

| Wahome (2018) [24] | 2005-16 | 753 | Kenya | Community - personal networks, sex venues | No | 0.76 (0.71-0.8) | 97.9% | 16.9% |

| Smith (2012) [25] | 1998-2001 | 7754 | USA | Unclear | Yes | 0.74 | 84% | 42% |

| Yin (2018) [30] | 2013-14 | 3588 | China | Study clinics and community | Yes | 0.71 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Dijkstra (2020) [26••] | 2003-18 | 1071 | Netherlands | STI clinic | Yes | 0.70 (0.64-0.76) | 54.0% | 77.9% |

| Hoenigl (2015) [31] | 2008-2014 | 8326 | USA | Community-based screening program | Yes | 0.70 (0.63-0.78) | 58% | 76% |

| Luo (2019) [32] | 2009-16 | 1442 | China | Unclear | Yes | 0.63 (0.61-0.66) | Nor reported | Not reported |

| Jones (2018) [33] | 2010-14 | 562 | USA | Recruited from venue-based time-space sampling and via Facebook ads | Yes |

HIRI: 0.62 (0.52-0.72) Menza: 0.51 (0.41-0.60) SDET: 0.55 (0.44-0.66) |

HIRI: 62.5% (43.7-78.9) Menza: 62.5% (43.7-78.9) SDET: 25% (11.5-43.4) |

HIRI: 56.7% (52.4-61.0) Menza: 41.1% (36.9-45.5) SDET: 83.9% (80.5-87.0) |

| Yun (2019) [34] | 2009-16 | 999 | China | VCT in hospital, recruitment from community | Yes | 0.6 (0.45-0.74) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Beymer (2017) [35] | 2009-14 | 9481 | USA | LGBT Centre | No | 75% | 50% |

LGBT lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender; STI sexually transmitted infection; VCT voluntary counselling and testing; 95% CI 95% confidence interval

Table 3 summarises the risk-based tools for the paediatric population. Most studies were for 'screening out' (67%, 8/12). A minority had been externally validated (6/13). Only two studies reported AUCs (0.73 [36], 0.65 [6••]); both were generally lower than most tools used for MSM. The tools with the highest sensitivity were for prioritising children for HIV testing at birth in Botswana (100% [37]), hospitalised paediatric patients in Papua New Guinea (96% [38]) and Malawi (84% [39]). The tools with the highest specificity were for targeting hospitalised paediatric patients in Central Sudan (96% [40]) and Zimbabwe (88% [41]). The most common domain used in the tools was symptoms and signs (Supplementary Table 2). The average number of items within a tool was 5.2 (range 4–9).

Table 3.

Risk-based screening tools for paediatric population ordered by the area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC)

| Lead Author (year of publication) | Year of data | Sample size | Country | Setting | External validation? | AUC | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bandason (2016) [36]* | 2013-14 | 9568 | Zimbabwe | Primary care | Yes | 0.73 (0.72-0.75) | 80.4% (76.5-84.0) | 66.3% (65.3-67.2) |

| Bandason (2018) [6••]* | 2015 | 5384 | Zimbabwe | Community | Unclear | 0.65 (0.60-0.72) | 56.3% (44-68.1) | 75.1% (73.9-76.3) |

| Ibrahim (2018) [37]* | 2015-16 | 2303 | Botswana | Hospital maternity wards | No | Not reported | 100% | Not reported |

| Allison (2011) [38] | 2007-08 | 487 | PNG | Hospital | Yes | Not reported | 96.3% | 25% |

| Moucheraud (2018) [39] | 2016-17 | 8602 | Malawi | Inpatient paediatric ward | Yes | Not reported | 84.4% | 39.6% |

| Bandason (2015) [42]* | 2015 | 6102 | Zimbabwe | Primary health centre | Yes | Not reported | 80% (75-85) | 66% (95% CI 64-67) |

| Du Plessis (2019) [43]* | 2014-16 | 1759 | South Africa | Hospital maternity wards | No | Not reported | 80% | 64% |

| Ferrand (2011) [44]* | 2011 | 506 | Zimbabwe | Primary care | Yes | Not reported | 74% (64-82) | 80% (71-87) |

| Mafaune (2020) [45]* | 2018-19 | 1970 | Zimbabwe | Health facility (Antenatal) | No | Not reported | 62.1% | 87.2% |

| Bandason (2018) [6••]* | 2015 | 5384 | Zimbabwe | Unclear | Unclear | Not reported | 56.3% (44-68.1) | 75.1% (73.9-76.3) |

| Nathoo (2012) [41] | 2012 | 355 | Zimbabwe | Medical paediatric wards | No | Not reported | 43% | 88% |

| Abbas (2010) [40] | 2007-08 | 127 | Central Sudan | Hospital | Unclear | Not reported |

WHO-CCD 16.7% (0.4-64.1), B-CCD 33.3% (4.3-77.7), MB-CCD 66.7% (22.3-95.7) |

96% (90.1-98.9), 88% (80-93.6) 74% (64.3-82.3) |

*Screening out tools

Table 4 summarises the risk-based tools for targeting women. All tools were used to “screen in”. A majority had been externally validated (5/8). The tools with the highest AUC were used for targeting pregnant women in Kenya (0.84) [46], and sexually active women in South Africa (0.75 [47] and 0.73 [14]). The tools with the highest sensitivity were for targeting women in South Africa (96% [48]), women in South Africa/Uganda/Zimbabwe (91% [49]) and Malawi/South Africa/Uganda/Zimbabwe (90%) [50]. The tools with the highest specificity were for targeting sexually active women (18–30 years old) in South Africa (84% ) [48], sexually active women (18–24 years old) in South Africa (84%) [51] and sexually active women (18–35 year old) in South Africa (71%) [51]. The most common domain used in the tool was risk behaviours (Supplementary Table 3). The average number of items within a tool was 6 (range 4–7).

Table 4.

Risk-based screening tools for women ordered by the area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC)

| Author | Year | Sample size | Country | Setting (target group) | External validation? | AUC | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pintye (2017) [46] | 2011-14 | 1304 | Kenya |

Antenatal clinics (pregnant women) |

Yes |

0.84 (95%CI 0.72-0.95) 0.76 (0.67-0.85) – simplified score |

Not reported | Not reported |

| Wand (2018) [47] | 2002-12 | 8982 | South Africa |

Part of trial (sexually active 16+) |

Yes |

0.75 - development 0.71 - validation |

83% (development) 80% (validation) |

33% (development) 32% (validation) |

| Wand (2012) [14] | 2003-06 | 1485 | South Africa |

Unclear (women 18-49) |

Yes |

0.73 (0.66-0.79) - development 0.79 (0.70-0.81) - validation |

88% (development) 90% (validation) |

32% (development) 36% (validation) |

| Balkus (2016) [49] | 2009-11 | 5029 | South Africa, Uganda, Zimbabwe |

Part of trial (women 18-40) |

Yes |

0.67 (0.64-0.70) – development 0.7 (0.65-0.75) – validation with HPTN035 0.58 (0.51-0.65) – validation with FEM-PrEP |

91% (development) 84% (HPTN035) 83% (FEM-PrEP) |

38% (development) 46% (HPTN035) 31% (FEM-PrEP) |

| Balkus (2016) [50] | 2016 | 1269 | Malawi, South Africa, Uganda, Zimbabwe |

Part of trial (women 18-40) to externally validate the tool. |

Yes | 0.66 (0.6-0.73) | 90% | 35% |

| Burgess (2018) [52] | 2018 | 444 | South Africa |

Unclear (women 18-40) |

Unclear |

0.66 (0.54-0.74) – overall 0.69 (0.6-0.78) - age <25 0.49 (0.3-0.63) – age >25 |

64% (overall) 78% (age <25) 58% (age >25) |

57% (overall) 49% (age <25) 38% (age >25) |

| Peebles (2018) [51] | 2015-18 | 5573 | South Africa |

A diverse range of settings across five provinces (women 18-35) |

Yes |

0.64 (0.6-0.67) – age 18-24 0.68 (0.62-0.73) – age 25-35 0.61 (0.58-0.65) – using VOICE score [49] |

48.6% (age 18-24) 78.6% (age 25-35) |

70.8% (age 18-24) 42.7% (age 25-35) |

| Burgess (2017) [48] | 2011-14 | 1115 | South Africa |

9 South African sites (sexually active, 18-30) |

No | 0.56 (0.5-0.62) |

96% (Risk score >3) 84% (Risk score >5) |

84% (Risk score >5) 23% (Risk score >5) |

The risk-based tools are provided for emergency department attendees (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5), primary care attendees (Supplementary Tables 6 and 7), hospital inpatients (Supplementary Tables 8 and 9), adults in the community (Supplementary Tables 10 and 11), STI clinic attendees (Supplementary Tables 12 and 13), incarcerated persons (Supplementary Tables 14 and 15), serodiscordant couples (Supplementary Tables 16 and 17), and people who inject drugs (Supplementary Tables 18 and 19). The risk of bias assessments are provided in Supplementary Tables 20-24.

Discussion

This systematic review highlights the use of HIV screening tools in both high and low HIV prevalence settings. We found that published tools were mostly used to screen in and prompt testing for those who may be missed otherwise, primarily from high or middle-income countries and administered predominantly in primary care settings. Screening out tools were mainly used in neonatal or paediatric settings. We found that the tools with the highest accuracy existed for identifying acute HIV infections among MSM. Caution should be exercised when using risk-based screening tools for other populations, as we found variable performance depending on their setting. In low HIV prevalence settings where HIV testing is not routinely offered, there is benefit in using the tools to screen in those with a greater risk of HIV acquisition. However, there is a trade-off in using these tools in high HIV prevalence settings and/or among key populations. Using these tools to reduce testing offer in these contexts risk missing undiagnosed people living with HIV.

There was some evidence on the potential risks and benefits of tools that would screen out and not test individuals. The systematic literature found several studies to reduce testing volume with mixed results. There seems to be value in using tools to target expensive acute HIV screening tests among MSM [53]. In low HIV prevalence settings, these screening out tools have high negative predictive values (NPV): a tool for emergency department and primary care attendees in Spain (100% NPV) [54], a tool to identify children living with HIV in a community setting in Zimbabwe (99% NPV) [6••], and a tool to identify adolescents attending primary care in Zimbabwe (100% NPV) [53]. Targeted screening of infants compared with universal testing in Botswana could lower costs of testing [37]. However, studies show that screening out tools for newborn testing could miss 1 in 5 newborns in South Africa [43] and 2 in 5 in Zimbabwe [45]. Further, the use of targeted screening tools in US emergency departments [55] or among US veterans [16] would still miss cases of people living with HIV. In some instances, screening out tools did not significantly reduce testing volume nor increase positivity rates [56, 57]. Together, the evidence suggests that providers must be cautious in using screening out tools depending on the target population, as missing people with HIV who would otherwise be tested could undermine efforts to achieve ambitious 95-95-95 targets.

There could be several benefits to using risk-based screening in tools. First, screening tools evaluated were generally effective in identifying people who had a higher likelihood of HIV, thereby improving allocative efficiency by targeting limited resources to those with higher risks of HIV acquisition [58], prioritising patients who need expensive tests (e.g. for identifying acute HIV) [22, 23, 26••] or prioritising individuals in need of more expensive prevention methods like PrEP [25, 28, 59–62, 63••, 64]. However, several studies underscore the importance of using locally validated tools as the performance of tools could differ according to race [65] or age [51]. Second, we found that in settings where patients may not be forthcoming about risk factors or where clinicians are not likely to ask, the implementation of risk-based tools prompted the offer of testing and improved HIV testing uptake [44, 66, 67]. Except for three papers [17, 30, 54], no other study discussed how privacy and confidentiality were maintained when administering the screening tool. Third, most screening tools were simple enough to allow their use by non-professional health workers, such as lay counsellors or self-assessments [39]. There have been many innovations with virtual interventions, particularly during COVID-19, such as online HIV self-testing which included self-risk assessment tools [68]. Using screening in tools could further improve the efficiencies of decentralised HIV testing services by enabling the training of lay providers, peers, and clients to use these tools in a range of contexts and settings to focus HIV testing outreach. Last, risk-based screening tools may be more cost-effective than routine testing in some settings. An economic evaluation from the USA reported that targeted testing compared with routine testing in clinics, hospitals, and community-based organisations was more cost-effective per diagnosis and per transmission averted [69]. In addition, targeted testing compared with testing patients suspected to have symptomatic HIV in US emergency departments was found to be cost-saving [70]. The cost per new diagnosis in a primary care setting in Spain was €129 compared with €2001 for routine testing [71].

There may be potential harms to using HIV risk-based screening in tools. First, the screening questions that seek to identify people with high HIV risks could potentially be stigmatising and reduce testing uptake. For example, a study in Indonesia used self-reported injecting drug use as part of the risk-based screening tool among incarcerated persons [15]. This led to under-reporting of injecting drug use and 1 in 3 eligible people declining to test [15]. Second, given suboptimal sensitivity for some tools, there is potential for missing cases of people living with HIV [26••]. This is particularly important for tools used for antenatal or paediatric populations where the consequences of missing an HIV case outweighs any benefits of risk-based HIV testing [6••, 41, 43]. Therefore, universal opt-out testing should be standard practice in settings with serious consequences for missing a case. Third, there are resource implications when implementing risk-based screening as there is a need for regular external validation of tools to local contexts to ensure its expected accuracy, correct items to include, optimal length, acceptability by providers and patients, and the impact on patient flow [26••, 54, 72]. This ongoing evaluation and monitoring could impact the feasibility of implementing these tools.

Overall, an ideal HIV risk-based screening tool should be accurate, preferably with an area under the curve (AUC) of over 0.8 [18]. Tools should be externally validated to account for variations in HIV epidemiological profiles (even within the same country). Further, as risk factors may change over time, regular evaluations every few years may be necessary to ensure the tools continue to perform optimally and are appropriately adapted to local contexts. Tools must be reliable and ideally be based on objective measures rather than self-reported behaviours, which might be inaccurate if risk items are stigmatising or challenging to measure. This includes careful evaluation of the language construction of risk-based tools such that they are culturally appropriate for each setting. Tools should be administered in a private setting to maintain confidentiality. Finally, tools must be feasible to implement using simple questionnaires acceptable to the provider and patient and do not adversely affect the clinic flow.

The strength of this research is that we comprehensively searched the literature to provide an overview of HIV-risk-based tools. We identified tools with high accuracy targeting different populations, and explored the advantages and disadvantages of implementing such tools. There are limitations to the study. We did not include any non-English language data, which may lead to selection bias. There would be a possibility of publication bias if screening tools that performed poorly were not published.

Conclusion

As evidence continues to accumulate for HIV risk-based tools, we strongly encourage considerations on the role of screening in tools in settings where the routine offer of testing is not feasible or recommended, and how these could be adapted to self-assessment, targeted outreach, distribution of self-tests, and incorporated into virtual interventions for HIV testing. Caution must be exercised for screening out tools, where there is a trade-off between reducing costs of testing with missing cases of people living with HIV. We also encourage programmes to construct, adapt and regularly evaluate the implementation of any HIV risk-based screening tools to ensure they do not undermine progress toward the 95-95-95 targets. Further data will also be needed to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of HIV risk-based screening tools and assess any differences in linkage to care for people tested using risk-based tools.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 233 kb)

Code Availability

Not applicable

Author Contribution

JJO, CJ, and MSJ conceptualized the idea. KC, CQ, MJT, and TH performed the screening and extraction of data. JJO analysed the data. JJO and KC wrote the original draft. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. This research was supported by funding from the World Health Organization through the following grants: USAID GHA-G-00-09-00003, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation OPP1177903. JJO is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Emerging Leadership Fellowship (GNT1193955).

Data Availability

All relevant data are presented in the manuscript and online supplementary materials. Any further details can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable

Consent to Participate

Not applicable

Consent for Publication

Not applicable

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on The Science of Prevention

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: •• Of major importance

- 1.UNAIDS. Global HIV & AIDS statistics — Fact sheet [16th June 2021]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet.

- 2.Group ISS. Lundgren JD, Babiker AG, Gordin F, Emery S, Grund B, et al. Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy in Early Asymptomatic HIV Infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):795–807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNAIDS. Understanding fast-track: accelerating action to end the AIDS epidemic by 2030. Geneva, Switzerland; 2015.

- 4.UNAIDS. Global AIDS update: Seizing the moment- tackling entrenched inequalities to end epidemics. Geneva, Switzerland; 2020. Report No.: JC991.

- 5.Bernstein KT, Stephens SC, Moss N, Scheer S, Parisi MK, Philip SS. Partner services as targeted HIV screening--changing the paradigm. Public health reports (Washington, DC : 1974). 2014;129 Suppl 1(9716844, qja):50-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.••.Bandason T, Dauya E, Dakshina S, McHugh G, Chonzi P, Munyati S, et al. Screening tool to identify adolescents living with HIV in a community setting in Zimbabwe: A validation study. PloS One. 2018;13(10):e0204891. This study is an example of the importance of validating HIV risk-based tools to ensure the tools are context-specific. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Indravudh PP, Fielding K, Kumwenda MK, Nzawa R, Chilongosi R, Desmond N, et al. Community-led delivery of HIV self-testing targeting adolescents and men in rural Malawi: A cluster-randomised trial. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2019;22(Supplement 5).

- 8.Hood JE, Forsyth EW, Neary J, Buskin S, Golden MR, Katz DA. HIV self-testing in the seattle transgender community: A mixed-methods evaluation. Topics in Antiviral Medicine. 2016;24(E-1):416. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allison W, Kiromat M, Vince J, Wand H, Cunningham P, Kaldor J. Development of an algorithmic tool to guide routine HIV testing of hospitalized pediatric patients in Papua New Guinea (PNG), a resource-limited setting with moderate HIV prevalence. Journal of the International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care. 2010;9(1):56. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hankin A, Freiman H, Copeland B, Shah B. A comparison of routine hiv screening strategies in a large, inner-city emergency department: Integrated versus parallel models. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2014;64(4 SUPPL. 1):S67. doi: 10.1177/00333549161310S111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dijkstra M, Van Rooijen MS, Hillebregt MM, Van Sighem AI, Smit C, Hogewoning A, et al. Targeted screening and immediate start of treatment for acute HIV infection decreases time between HIV diagnosis and viral suppression among MSM at a Sexual Health Clinic in Amsterdam. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2019;22(Supplement 5).

- 12.Tillison AS, Avery AK. Evaluation of the Impact of Routine HIV Screening in Primary Care. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care. 2017;16(1):18–22. doi: 10.1177/2325957416666677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.••.Lin TC, Dijkstra M, De Bree GJ, Schim Van Der Loeff MF, Hoenigl M. The Amsterdam symptom and risk-based score predicts for acute HIV infection in men who have sex with men in San Diego. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2018;79(2):E52-E5. This study provides an example of a high performance HIV-risk tool for men who have sex with men. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Wand H, Ramjee G. Assessing and evaluating the combined impact of behavioural and biological risk factors for HIV seroconversion in a cohort of South African women. AIDS care. 2012;24(9):1155–1162. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.687820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelwan EJ, Isa A, Alisjahbana B, Triani N, Djamaris I, Djaja I, et al. Routine or targeted HIV screening of Indonesian prisoners. International journal of prisoner health. 2016;12(1):17–26. doi: 10.1108/IJPH-04-2015-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennedy LA, Gordin FM, Kan VL. Assessing targeted screening and low rates of HIV testing. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(9):1765–1768. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.182790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muttai H, Guyah B, Musingila P, Achia T, Miruka F, Wanjohi S, et al. Development and Validation of a Sociodemographic and Behavioral Characteristics-Based Risk-Score Algorithm for Targeting HIV Testing Among Adults in Kenya. AIDS Behav. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Mandrekar JN. Receiver operating characteristic curve in diagnostic test assessment. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5(9):1315–1316. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181ec173d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools [Available from: https://joannabriggs.org/critical-appraisal-tools.

- 20.UNAIDS. AIDSinfo [Available from: https://aidsinfo.unaids.org/.

- 21.UNAIDS. Global HIV & AIDS statistics- 2020 fact sheet 2020

- 22.Sanders EJ, Wahome E, Powers KA, Werner L, Fegan G, Lavreys L, et al. Targeted screening of at-risk adults for acute HIV-1 infection in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2015;29(Suppl 3):S221–S230. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin TC, Gianella S, Tenenbaum T, Little SJ, Hoenigl M. A Simple Symptom Score for Acute Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection in a San Diego Community-Based Screening Program. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2018;67(1):105–111. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wahome E, Thiong'o AN, Mwashigadi G, Chirro O, Mohamed K, Gichuru E, et al. An Empiric Risk Score to Guide PrEP Targeting Among MSM in Coastal Kenya. AIDS and behavior. 2018;22(Suppl 1):35–44. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2141-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith DK, Pals SL, Herbst JH, Shinde S, Carey JW. Development of a clinical screening index predictive of incident HIV infection among men who have sex with men in the United States. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2012;60(4):421–427. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318256b2f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.••.Dijkstra M, Lin TC, de Bree GJ, Hoenigl M, Schim van der Loeff MF. Validation of the San Diego Early Test Score for Early Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection Among Amsterdam Men Who Have Sex With Men. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2020;70(10):2228-30. This study validates a widely used HIV-risk based tool among men who have sex with men. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Dijkstra M, de Bree GJ, Stolte IG, Davidovich U, Sanders EJ, Prins M, et al. Development and validation of a risk score to assist screening for acute HIV-1 infection among men who have sex with men (vol 17, pg 425, 2017). Bmc Infectious Diseases. 2017;17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Scott H, Vittinghoff E, Irvin R, Liu A, Nelson L, Del Rio C, et al. Development and Validation of the Personalized Sexual Health Promotion (SexPro) HIV Risk Prediction Model for Men Who Have Sex with Men in the United States. AIDS and behavior. 2020;24(1):274–283. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02616-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wahome E, Fegan G, Okuku HS, Mugo P, Price MA, Mwashigadi G, et al. Evaluation of an empiric risk screening score to identify acute and early HIV-1 infection among MSM in Coastal Kenya. AIDS (London, England). 2013;27(13):2163–2166. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283629095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yin L, Zhao Y, Peratikos MB, Song L, Zhang X, Xin R, et al. Risk Prediction Score for HIV Infection: Development and Internal Validation with Cross-Sectional Data from Men Who Have Sex with Men in China. AIDS and behavior. 2018;22(7):2267–2276. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2129-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoenigl M, Graff-Zivin J, Little SJ. Costs per Diagnosis of Acute HIV Infection in Community-based Screening Strategies: A Comparative Analysis of Four Screening Algorithms. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2015;62(4):501–511. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo Q, Huang X, Li L, Ding Y, Mi G, Scott SR, et al. External validation of a prediction tool to estimate the risk of human immunodeficiency virus infection amongst men who have sex with men. Medicine. 2019;98(29):e16375. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000016375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones J, Hoenigl M, Siegler AJ, Sullivan PS, Little S, Rosenberg E. Assessing the Performance of 3 Human Immunodeficiency Virus Incidence Risk Scores in a Cohort of Black and White Men Who Have Sex With Men in the South. Sex Transm Dis. 2017;44(5):297–302. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yun K, Xu J, Leuba S, Zhu Y, Zhang J, Chu Z, et al. Development and Validation of a Personalized Social Media Platform-Based HIV Incidence Risk Assessment Tool for Men Who Have Sex With Men in China. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(6):e13475. doi: 10.2196/13475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beymer MR, Weiss RE, Sugar CA, Bourque LB, Gee GC, Morisky DE, et al. Are Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guidelines for Preexposure Prophylaxis Specific Enough? Formulation of a Personalized HIV Risk Score for Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Initiation. Sex Transm Dis. 2017;44(1):48–56. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bandason T, McHugh G, Dauya E, Mungofa S, Munyati SM, Weiss HA, et al. Validation of a screening tool to identify older children living with HIV in primary care facilities in high HIV prevalence settings. AIDS (London, England). 2016;30(5):779–785. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ibrahim M, Maswabi K, Ajibola G, Moyo S, Hughes MD, Batlang O, et al. Targeted HIV testing at birth supported by low and predictable mother-to-child transmission risk in Botswana. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2018;21(5):e25111. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Allison WE, Kiromat M, Vince J, Wand H, Cunningham P, Graham SM, et al. Development of a clinical algorithm to prioritise HIV testing of hospitalised paediatric patients in a low resource moderate prevalence setting. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(1):67–72. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.179143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moucheraud C, Chasweka D, Nyirenda M, Schooley A, Dovel K, Hoffman RM. Simple Screening Tool to Help Identify High-Risk Children for Targeted HIV Testing in Malawian Inpatient Wards. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2018;79(3):352-357. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Abbas AA, Gabo NEAAA, Babiker ZOE, Herieka EAM. Paediatric HIV in central Sudan: high sero-prevalence and poor performance of clinical case definitions. Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 2010;47(1):82–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nathoo KJ, Rusakaniko S, Tobaiwa O, Mujuru HA, Ticklay I, Zijenah L. Clinical predictors of HIV infection in hospitalized children aged 2-18 months in Harare, Zimbabwe. Afr Health Sci. 2012;12(3):259–267. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v12i3.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bandason T, McHugh G, Ferrand RA, Munyati S, Kranzer K, Chonzi P. Moving towards targeted HIV testing in older children at risk of vertically transmitted HIV. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2015;18:82. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Du Plessis NM, Muller CJB, Avenant T, Pepper MS, Goga AE. An Early Infant HIV Risk Score for Targeted HIV Testing at Birth. Pediatrics. 2019;143(6). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Ferrand RA, Weiss HA, Nathoo K, Ndhlovu CE, Mungofa S, Munyati S, et al. A primary care level algorithm for identifying HIV-infected adolescents in populations at high risk through mother-to-child transmission. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16(3):349–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02708.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mafaune HW, Sacks E, Chadambuka A, Musarandega R, Tachiwenyika E, Simmonds FM, et al. Effectiveness of Maternal Transmission Risk Stratification in Identification of Infants for HIV Birth Testing: Lessons From Zimbabwe. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2020;84 Suppl 1(100892005):S28-S33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Pintye J, Drake AL, Kinuthia J, Unger JA, Matemo D, Heffron RA, et al. A Risk Assessment Tool for Identifying Pregnant and Postpartum Women Who May Benefit From Preexposure Prophylaxis. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2017;64(6):751–758. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wand H, Reddy T, Naidoo S, Moonsamy S, Siva S, Morar NS, et al. A Simple Risk Prediction Algorithm for HIV Transmission: Results from HIV Prevention Trials in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa (2002-2012) AIDS Behav. 2018;22(1):325–336. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1785-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burgess EK, Delany-Moretlwe S, Pisa P, Ahmed K, Sibiya S, Gama C, et al. Validation of a risk score for HIV acquisition in young African women with facts 001. Topics in Antiviral Medicine. 2017;25(1 Supplement 1):364s-5s.

- 49.Balkus JE, Brown E, Palanee T, Nair G, Gafoor Z, Zhang J, et al. An Empiric HIV Risk Scoring Tool to Predict HIV-1 Acquisition in African Women. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2016;72(3):333–343. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Balkus J, Palnee-Phillips T, Zhang J, Matovu Kiweewa F, Nair G, Pather A, et al., editors. A Validated Risk Score to Predict HIV Acquisition in African Women: Assessing Risk Score Performance among Women who Participated in the ASPIRE Trial. HIV Research for Prevention (HIVR4P) Partnering for Prevention; 2016; Chicago.

- 51.Peebles K, Palanee-Phillips T, Balkus JE, Beesham I, Makkan H, Deese J, et al. Age-Specific Risk Scores Do Not Improve HIV-1 Prediction Among Women in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;85(2):156–164. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burgess EK, Yende-Zuma N, Castor D, Karim QA. An age-stratified risk score to predict HIV acquisition in young South African women. Topics in Antiviral Medicine. 2018;26:419. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Facente SN, Pilcher CD, Hartogensis WE, Klausner JD, Philip SS, Louie B, et al. Performance of risk-based criteria for targeting acute HIV screening in San Francisco. PloS one. 2011;6(7):e21813. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Elias MJP, Gomez-Ayerbe C, Elias PP, Muriel A, de Santiago AD, Martinez-Colubi M, et al. Development and Validation of an HIV Risk Exposure and Indicator Conditions Questionnaire to Support Targeted HIV Screening. Medicine. 2016;95(5):e2612. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hsieh YH, Patel A, Laeyendecker O, Rahmoun N, Alazemi M, Quinn TC, et al. All current emergency department screening strategies for human immunodeficiency virus still leaving many patients undiagnosed. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2018;25:S143–S1S4. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lyons MS, Lindsell CJ, Ruffner AH, Wayne DB, Hart KW, Sperling MI, et al. Randomized comparison of universal and targeted HIV screening in the emergency department. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;64(3):315–323. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a21611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kakanfo K, Khamofu H, Obiora-Okafo C, Obanubi C, Adedokun O, Oladele E, et al. How well does the bandason HIV risk screening tool perform in the nigerian setting? findings from a large-scale field implementation. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2018;34(Supplement 1):151. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haukoos J, Hopkins E, Bender B, Sasson C, Al-Tayyib A, Thrun M. Enhanced targeted hiv screening using the denver hiv risk score outperforms nontargeted screening in the emergency department. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2012;19(SUPPL. 1):S222–S2S3. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Giovenco D, Pettifor A, MacPhail C, Kahn K, Wagner R, Piwowar-Manning E, et al. Assessing risk for HIV infection among adolescent girls in South Africa: an evaluation of the VOICE risk score (HPTN 068) J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22(7):e25359. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blumenthal J, Jain S, Mulvihill E, Sun S, Hanashiro M, Ellorin E, et al. Perceived Versus Calculated HIV Risk: Implications for Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Uptake in a Randomized Trial of Men Who Have Sex With Men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;80(2):e23–ee9. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hoenigl M, Weibel N, Mehta SR, Anderson CM, Jenks J, Green N, et al. Development and validation of the San Diego Early Test Score to predict acute and early HIV infection risk in men who have sex with men. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(3):468–475. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kahle EM, Hughes JP, Lingappa JR, John-Stewart G, Celum C, Nakku-Joloba E, et al. An empiric risk scoring tool for identifying high-risk heterosexual HIV-1-serodiscordant couples for targeted HIV-1 prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62(3):339–347. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827e622d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.••.Krakower DS, Gruber S, Hsu K, Menchaca JT, Maro JC, Kruskal BA, et al. Development and validation of an automated HIV prediction algorithm to identify candidates for pre-exposure prophylaxis: a modelling study. Lancet HIV. 2019;6(10):e696-e704. This study uses machine learning as an approach to identify those at highest risk for HIV. This is an alternate approach for HIV risk-based tools. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Leal L, Torres B, Leon A, Lucero C, Inciarte A, Diaz-Brito V, et al. Predictive Factors for HIV Seroconversion Among Individuals Attending a Specialized Center After an HIV Risk Exposure: A Case-Control Study. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2016;32(10-11):1016–1021. doi: 10.1089/AID.2016.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jones J, Hoenigl M, Siegler A. Assessing the Performance of Three HIV Incidence Risk Scores in a Cohort of Black and White MSM in the South (vol 44, pg 297, 2017). Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2018;45(3):E13-E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Gillet C, Darling KEA, Senn N, Cavassini M, Hugli O. Targeted versus non-targeted HIV testing offered via electronic questionnaire in a Swiss emergency department: A randomized controlled study. PloS one. 2018;13(3):e0190767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Caldwell DH, Jan G. Computerized assessment facilitates disclosure of sensitive HIV risk behaviors among African Americans entering substance abuse treatment. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(4):365–369. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2012.673663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.HIV Self-Testing Africa Initiative. Considerations for HIV self-testing in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and its response: an operational update. [Available from: https://www.psi.org/project/star/resource-library/considerations-for-hiv-self-testing-in-the-context-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-and-its-response-an-operational-update/.

- 69.Castel AD, Choi S, Dor A, Skillicorn J, Peterson J, Rocha N, et al. Comparing Cost-Effectiveness of HIV Testing Strategies: Targeted and Routine Testing in Washington, DC. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0139605. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dowdy DW, Rodriguez RM, Hare CB, Kaplan B. Cost-effectiveness of targeted human immunodeficiency virus screening in an urban emergency department. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2011;18(7):745–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Menacho I, Sequeira E, Muns M, Barba O, Leal L, Clusa T, et al. Comparison of two HIV testing strategies in primary care centres: indicator-condition-guided testing vs. testing of those with non-indicator conditions. HIV medicine. 2013;14 Suppl 3(100897392):33-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 72.Falasinnu T, Gustafson P, Gilbert M, Shoveller J. Validation of the denver HIV risk score for targeting HIV screening in Vancouver, British columbia. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2015;91(SUPPL. 1):A63. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2014-051992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 233 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are presented in the manuscript and online supplementary materials. Any further details can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.