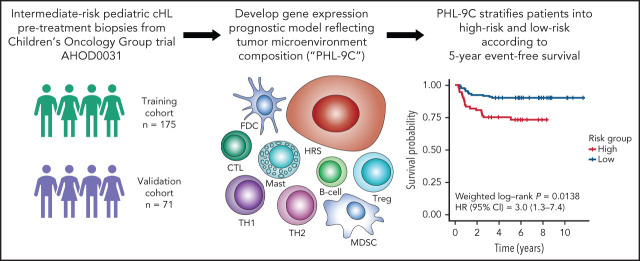

Johnston et al demonstrate differences in gene expression between pediatric and adult classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL), finding that eosinophil, B-cell, and mast cell signatures were enriched in children while macrophage and stromal cell signatures were more prominent in adults. They also developed and validated a gene expression profile–based model reflective of the tumor microenvironment biology, but independent of clinical features, that predicts event-free survival in pediatric patients. This model may be applicable for use in future clinical trials.

Key Points

Gene signatures reflecting tumor microenvironment composition correlate with event-free survival of patients in the COG AHOD0031 trial.

An outcome prognostic model risk stratifies patients according to 5-year event-free survival.

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) is a common malignancy in children and adolescents. Although cHL is highly curable, treatment with chemotherapy and radiation often come at the cost of long-term toxicity and morbidity. Effective risk-stratification tools are needed to tailor therapy. Here, we used gene expression profiling (GEP) to investigate tumor microenvironment (TME) biology, to determine molecular correlates of treatment failure, and to develop an outcome model prognostic for pediatric cHL. A total of 246 formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue biopsies from patients enrolled in the Children’s Oncology Group trial AHOD0031 were used for GEP and compared with adult cHL data. Eosinophil, B-cell, and mast cell signatures were enriched in children, whereas macrophage and stromal signatures were more prominent in adults. Concordantly, a previously published model for overall survival prediction in adult cHL did not validate in pediatric cHL. Therefore, we developed a 9-cellular component model reflecting TME composition to predict event-free survival (EFS). In an independent validation cohort, we observed a significant difference in weighted 5-year EFS between high-risk and low-risk groups (75.2% vs 90.3%; log-rank P = .0138) independent of interim response, stage, fever, and albumin. We demonstrate unique disease biology in children and adolescents that can be harnessed for risk-stratification at diagnosis. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT00025259.

Introduction

Classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) is one of the most common malignancies in children and adolescents.1 As a result of treatment approaches that may include dose-dense chemotherapy, cure rates exceed 90%.2 However, long-term sequelae of standard therapy can negatively impact overall survival (OS) and therefore remain a major challenge in managing pediatric cHL patients. As firmly established and prospectively validated molecular biomarkers of response are lacking, developing such biomarkers in children and adolescents could aid in balancing toxicity with the efficacies of chemotherapy, radiation, and novel therapeutics.

cHL exhibits a unique morphological appearance as the malignant cell population, Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells, are vastly outnumbered by immune and stromal cells representing the tumor microenvironment (TME).3 Studies conducted predominantly in adult cHL have established the prognostic significance of reactive immune cells in the TME, in particular macrophages, T-cell subsets, B cells, and plasma cells. With the emergence of technology platforms applicable to formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue (FFPET), several prognostic models for adult cHL have been developed which utilize multigene signatures for patient risk stratification.4-6 However, studies exploring putative molecular biomarkers in pediatric cHL patients are sparse and have mainly been restricted to single-marker immunohistochemistry (IHC) studies.7-9 Here, we report the development of a gene expression–based model using cellular component scores, which identifies a subset of pediatric patients at high risk of treatment failure in an international, multisite, randomized clinical trial.

Study design

To generate a prognostic model of event-free survival (EFS) for pediatric cHL, we performed gene expression profiling (GEP) of pretreatment FFPET biopsies using NanoString CodeSets comprising published cHL prognostic markers and TME genes (supplemental Tables 1 and 2 available on the Blood Web site). For model building and validation, training (n = 175) and validation cohorts (n = 71, enriched for events) were drawn from the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) intermediate-risk HL trial AHOD0031 (supplemental Methods; supplemental Tables 3 and 4; supplemental Figure 1). This trial defined intermediate-risk HL, accounting for ∼60% of all pediatric cHL patients, as stages IB, IAE, IIB, IIAE, IIIA, and IVA with or without bulky disease, and IA or IIA with bulky disease. Genes were assigned to signatures termed cellular components according to the literature (supplemental Tables 1 and 2). Cellular component scores were calculated by the median expression of its constituent genes. Univariate Cox regression was used to determine cellular components significantly associated with EFS, which in turn were used as input to build a prognostic model for EFS. Thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC) IHC was used to validate GEP results.

Results and discussion

Of the available 274 tissue specimens, 246 cases (90%) yielded sufficient GEP data passing quality control measures. To test the performance of our previously published adult cHL OS prognostic model trained using cases from the Intergroup E2496 trial,5 we applied the 23-gene model to the training cohort of pediatric patients from the COG trial AHOD0031.10 According to this model, 51 pediatric patients were classified as “high risk” and 124 as “low risk” (supplemental Figure 2A-C). However, this model failed to predict inferior outcomes, with 5-year OS rates of 100% vs 96.3% (log-rank P = .07) and 5-year EFS rates of 83.9% vs 70.6% (log-rank P = .09) in the high-risk and low-risk groups, respectively (supplemental Figure 2D-E). Six genes from this model, CCL17, CXCL11, ALDH1A1, LMO2, IFNG, and PRF1, were significantly associated with EFS (P = .02, .004, .01, .01, .0003, and .005, respectively) but with opposing hazard ratios in the pediatric cohort compared with the adult cohort (supplemental Figure 2F-G). Moreover, using Cox regression interaction modeling contrasting EFS in the AHOD0031 trial with failure-free survival and OS in the E2496 trial, a large majority of gene features displayed significantly different prognostic behavior (supplemental Tables 5 and 6). Spearman correlation analysis of TME component score with age revealed that eosinophil (P = 3.7e-15), B-cell (P = 2.2e-07), and mast cell signatures (P = 1.3e-06) were more prominent in younger patients, whereas macrophage (P = 9.9e-16) and stroma signatures (P = 2.2e-11) predominated in older patients (supplemental Figures 3 and 4). These observations, in conjunction with the opposing hazard ratios of individual genes between the E2496 and AHOD0031 trials, strongly suggest a difference in the underlying biology of pediatric and adult cHL. This is further supported by epidemiologic evidence describing multimodal age distributions and Epstein-Barr virus–related disease etiologies that are associated with known histopathologically recognized subtypes.3,11

Given the importance of TARC (encoded by CCL17) for recruiting regulatory T cells (Treg) into the TME12 and the opposing prognostic association of CCL17 expression in pediatric vs adult cohorts (unfavorable vs favorable treatment outcomes), we sought to validate our GEP data using IHC. In the training cohort, 67.4% of cases were TARC high (supplemental Figure 5A). TARC-high vs -low cases had significantly different 5-year EFS (70.0% vs 86.6%, log-rank P = .025), validating the gene expression findings (supplemental Figure 5B).

The differences observed between pediatric and adult cHL motivated us to explore outcome-associated features and build a prognostic model using the pediatric cohort. Because EFS of the standard and experimental treatment arms in the AHOD0031 trial was not significantly different in the training cohort (P = .61),10 patient specimens were merged across treatment arms. The expression levels of 79 genes (10% of genes in our CodeSet) were significantly associated with EFS (P < .05; supplemental Figure 6). Most notably, we found an inferior prognostic association of Treg and T-helper cell 2 (Th2) gene signatures in pediatric cHL, which is in contrast to several previous studies in adult cHL ascribing a favorable prognostic impact to FOXP3+ Treg cells.13-15 The unfavorable prognostic impact of a Treg signature is consistent with our finding that high TARC expression by HRS cells, a chemo-attractant of Treg cells, is associated with inferior survival in pediatric cHL.

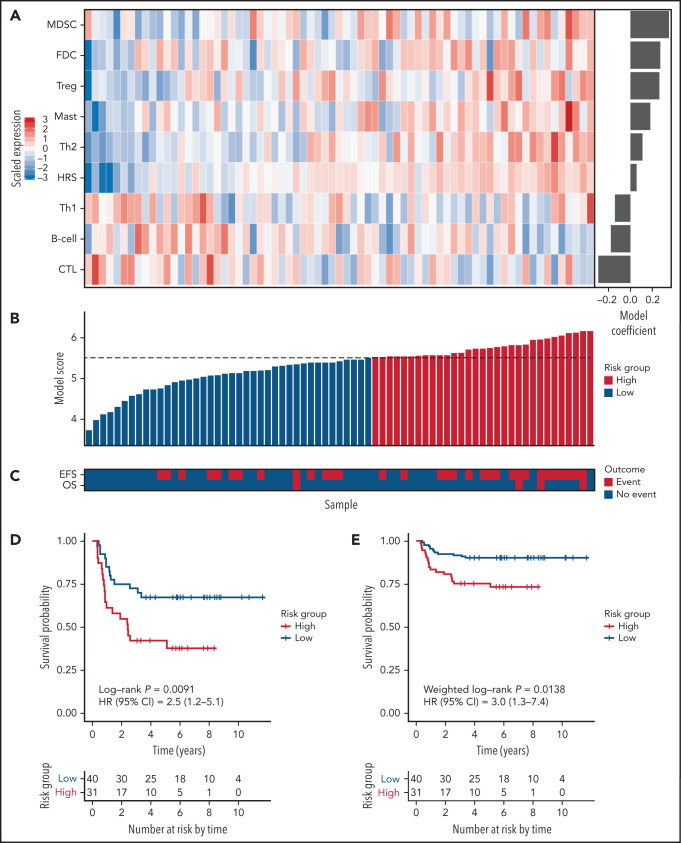

For model building, a cellular component-based approach was used, where scores for 9 components comprising 111 genes were inputs for Cox regression analysis. The 9 components included 5 cellular components significantly associated with an increased hazard in univariate Cox regression (Treg, mast, Th2, myeloid-derived suppressor cell, and HRS), one component (follicular dendritic cell) significantly associated with EFS in rapid early responders, and 3 components (B cell, cytotoxic T cell, and Th1) associated with a decreased but nonsignificant hazard ratio. The latter components were used to balance the model with positive and negative coefficients (Figure 1A-C; supplemental Table 7). The resulting model, PHL-9C, was applied to the validation cohort and resulted in a statistically significant survival difference between high-risk and low-risk patients (5-year EFS 75.2% vs 90.3%, weighted log-rank P = .0138, Figure 1D-E; supplemental Figure 7). The global performance of PHL-9C was assessed and resulted in an area under the time-dependent ROC curve of 0.73 at 5 years (supplemental Figure 8).

Figure 1.

The 9-cellular component model PHL-9C for pediatric cHL applied to the independent validation cohort. (A) Scaled gene expression values of the 9 cellular components in the prognostic model for pediatric cHL. Columns represent patients arranged by their individual model score, and rows represent cellular components arranged by their model coefficient. Bar plot of the model coefficients for each cellular component (right). (B) Model scores for the 9-cellular component model colored by risk class as defined by the model score threshold (dotted line). (C) Survival outcomes of patients in the validation cohort. Kaplan Meier estimates of EFS in the independent validation cohort using nonweighted analysis (D) and weighted analysis (E). Because the validation cohort was enriched for events, weighted analysis was performed to estimate PHL-9C's performance in the AHOD0031 trial population. The number at risk indicates the number of patients in the validation cohort contributing to the weighted analysis.

We then tested PHL-9C for independence from other clinical parameters. Univariate Cox regression analysis revealed that PHL-9C, fever, and albumin were associated with EFS in the validation cohort (supplemental Table 8). PHL-9C and fever were also significant in the multivariable Cox model, indicating that PHL-9C is independent from fever and albumin (supplemental Table 8). Pairwise multivariable analyses of PHL-9C against the individual variables that determine Childhood Hodgkin International Prognostic Score16 and early response status revealed that PHL-9C was associated with EFS independent of stage IV, fever, albumin, and stratum SER (Table 1).

Table 1.

Pairwise multivariable analyses in the pediatric HL validation cohort

| Variable | Patients | Pairwise multivariable analysis* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | HR | SE | P | |

| Pairwise analysis 1 | |||||

| Model score high | 31 | 43.7 | 2.4 | 0.4 | .017 |

| Stage IV | 15 | 21.1 | 1.3 | 0.4 | .468 |

| Pairwise analysis 2 | |||||

| Model score high | 31 | 44.3 | 2.1 | 0.4 | .055 |

| Mediastinal mass >0.33†,‡ | 25 | 35.7 | 1.4 | 0.4 | .401 |

| Pairwise analysis 3 | |||||

| Model score high | 31 | 43.7 | 3.0 | 0.4 | .003 |

| Fever | 13 | 18.3 | 3.6 | 0.4 | .002 |

| Pairwise analysis 4 | |||||

| Model score high | 29 | 43.3 | 2.3 | 0.4 | .028 |

| Albumin <3.5‡ | 19 | 28.4 | 2.6 | 0.4 | .010 |

| Pairwise analysis 5 | |||||

| Model score high | 31 | 43.7 | 2.6 | 0.4 | .010 |

| Stratum SER | 22 | 31.0 | 0.8 | 0.4 | .620 |

HR, hazard ratio; SE, standard error; SER, slow early responder.

Pairwise multivariable analyses were performed with Cox proportional hazards regression models using only patients with data available for both variables.

Mediastinal mass was unavailable for 1 patient.

Albumin measurements were unavailable for 4 patients.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that GEP reflective of TME biology is prognostic for treatment outcome in a large proportion of children with cHL and that a gene expression–based biomarker assay, PHL-9C, reliably identifies patients at high risk for treatment failure in a risk-adapted treatment regimen. Given its applicability to routinely available FFPET, PHL-9C can be further tested in retrospective real-world settings or in upcoming biomarker studies complementing clinical trials that test other risk-adapted study designs, including validation in the COG study AHOD1331.

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Children’s Oncology Group, the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers National Cancer Institute Grant No. U10 CA98543, U24CA114766, and U10CA098413. The Children’s Oncology Group also acknowledges funding by NCTN Operations Center Grant U10CA180886, NCTN Statistics & Data Center Grant U10CA180899, and the St. Baldrick’s Foundation. C.S. acknowledges Large Scale Applied Research Project funding from Genome Canada, Genome BC, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute; as well as a Foundation grant from CIHR, the BC Cancer Foundation, and the Paul G. Allen Frontiers Group (Distinguished Investigator award). C.S. also received a New Investigator award from CIHR and a Career Investigator award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

Footnotes

Digital gene expression data can be requested from the corresponding author.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: D.W.S., T.M.H., and C.S. study design; R.L.J., A.M., T.M.H., and C.S. writing; all authors manuscript review; A.T. and A.M. digital gene expression profiling; R.L.J., A.M., D.W.S., T.M.H., and C.S. data interpretation; R.L.J., A.M., A.J., and C.S. data analysis; A.M., L.V., A.D., and R.D.G. immunohistochemistry and pathology review; and K.M.K., D.L.F., C.L.S., and T.M.H. case identification and clinical correlates.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.S. has performed consultancy for Seattle Genetics, Curis Inc., Roche, AbbVie, Juno Therapeutics and Bayer, and has received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Epizyme, and Trillium Therapeutics Inc. C.S. is a coinventor on a patent (“Method for determining lymphoma type”) using NanoString technology. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Christian Steidl, Department of Lymphoid Cancer Research, British Columbia Cancer, 675 West 10th Ave, Vancouver, BC V5Z 1L3, Canada; e-mail: csteidl@bccancer.bc.ca.

REFERENCES

- 1.Scott AR, Stoltzfus KC, Tchelebi LT, et al. Trends in cancer incidence in US adolescents and young adults, 1973-2015. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2027738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahn JM, Kelly KM. Adolescent and young adult Hodgkin lymphoma: raising the bar through collaborative science and multidisciplinary care. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(7):e27033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connors JM, Cozen W, Steidl C, et al. Hodgkin lymphoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sánchez-Espiridión B, Sánchez-Aguilera A, Montalbán C, et al. ; Spanish Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Study Group . A TaqMan low-density array to predict outcome in advanced Hodgkin’s lymphoma using paraffin-embedded samples. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(4):1367-1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott DW, Chan FC, Hong F, et al. Gene expression-based model using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded biopsies predicts overall survival in advanced-stage classical Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(6):692-700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan FC, Mottok A, Gerrie AS, et al. Prognostic model to predict post-autologous stem-cell transplantation outcomes in classical Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(32):3722-3733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barros MH, Hassan R, Niedobitek G. Tumor-associated macrophages in pediatric classical Hodgkin lymphoma: association with Epstein-Barr virus, lymphocyte subsets, and prognostic impact. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(14):3762-3771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta S, Yeh S, Chami R, Punnett A, Chung C. The prognostic impact of tumour-associated macrophages and Reed-Sternberg cells in paediatric Hodgkin lymphoma. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(15):3255-3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagpal P, Akl MR, Ayoub NM, et al. Pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma: biomarkers, drugs, and clinical trials for translational science and medicine. Oncotarget. 2016;7(41):67551-67573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman DL, Chen L, Wolden S, et al. Dose-intensive response-based chemotherapy and radiation therapy for children and adolescents with newly diagnosed intermediate-risk hodgkin lymphoma: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group Study AHOD0031. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(32):3651-3658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Massini G, Siemer D, Hohaus S. EBV in Hodgkin lymphoma. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2009;1(2):e2009013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Stasi A, De Angelis B, Rooney CM, et al. T lymphocytes coexpressing CCR4 and a chimeric antigen receptor targeting CD30 have improved homing and antitumor activity in a Hodgkin tumor model. Blood. 2009;113(25):6392-6402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alvaro T, Lejeune M, Salvadó MT, et al. Outcome in Hodgkin’s lymphoma can be predicted from the presence of accompanying cytotoxic and regulatory T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(4):1467-1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tzankov A, Meier C, Hirschmann P, Went P, Pileri SA, Dirnhofer S. Correlation of high numbers of intratumoral FOXP3+ regulatory T cells with improved survival in germinal center-like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma and classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Haematologica. 2008;93(2):193-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chetaille B, Bertucci F, Finetti P, et al. Molecular profiling of classical Hodgkin lymphoma tissues uncovers variations in the tumor microenvironment and correlations with EBV infection and outcome. Blood. 2009;113(12):2765-3775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartz CL, Chen L, McCarten K, et al. Childhood Hodgkin International Prognostic Score (CHIPS) predicts event-free survival in Hodgkin lymphoma: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(4):10.1002/pbc.26278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.