Abstract

Localization of cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1) immunoreactivity on mitochondrial membranes, at least their outer membranes distinctly, was detected in progesterone-producing cells characterized by mitochondria having tubular cristae and aggregations of lipid droplets in ovarian interstitial glands in situ of adult mice. Both immunoreactive and immunonegative mitochondria were contained in one and the same cell. Considering that the synthesis of progesterone is processed in mitochondria, the mitochondrial localization of CB1 in the interstitial gland cells suggests the possibility that endocannabinoids modulate the synthetic process of progesterone in the cells through CB1:

Keywords: CB1, mitochondria, ovary, steroidogenic cell

Introduction

In the endocannabinoid (eCB) signaling system, two most extensively studied eCBs are 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol (2-AG) and anandamide, also termed N-arachidonoyl ethanolamine (AEA). Key enzymes for the synthesis of 2-AG and AEA are diacylglycerol kinases (DGLs) and a specific phospholipase D (NAPE-PLD), respectively. In addition, receptors termed cannabinoid receptor (CB) type 1 and CB2 for eCBs and enzymes degrading eCBs such as monoacylglycerol lipase and fatty acid amide hydrolase all work together in the signaling system.

As eCBs affect various reproductive events from oogenesis and oocyte maturation to fertilization and from the implantation of embryo to the final outcome of pregnancy, 1 there have been studies on the localization of eCB signaling molecules in the female reproductive system by several authors with attention largely paid to supposed effects of eCB signaling on oocyte maturation after resumption of meiosis I.2–5 However, relatively little information is still available on the cellular and subcellular localization of the signaling molecules in the ovary in situ before the resumption of meiosis I. In view of this point, our recent study has clarified for the first time the detailed localization of CB1, DGLα, and DGLβ in oocytes in situ of mouse ovary. 6 This study was thus undertaken as the second to clarify in immuno-light and electron microscopy the expression and localization of these eCB signaling molecules in various ovarian cells in situ of adult mice. During this attempt, CB1 immunoreactivity was found on mitochondria containing tubular cristae in steroidogenic cells characterized by mitochondria having tubular cristae and aggregations of lipid droplets in the interstitial gland. Therefore, the localization was described here in detail.

Materials and Methods

In total, 10 female ICR mice at a stage of postnatal 8 weeks were purchased from the National Laboratory Animal Center, Bangkok, Thailand. As the expression bands for CB1 at its authentic molecular size and no differences in expression of the molecule among the four estrous stages were already confirmed in Western blots of adult ovaries of the same resource in our previous study, 6 mice at the diesterus stage were used in this study.

All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals at Khon Kaen University. This study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Khon Kaen University, based on the Ethics of Animal Experimentation of the National Research Council of Thailand (Reference No. IACUC-KKU-18/63).

The specimen preparation for routine immuno-DAB light and electron microscopy, including the treatment of adult mice and the control with antigen absorption, was done in the same way as that in our previous study. 6

For double immunofluorescence light microscopy, some cryostat sections were first incubated with CB1 antibody at the same concentration as used for single immunostaining described above and then with mouse monoclonal antibody for ATP5A (mitochondrial marker) (cat. no. ab14748, RRID:AB_301447; Abcam, UK) at a concentration of 1:100. The antigen–antibody reaction sites were visualized with goat anti-mouse IgM + IgG + IgA (H + L), FITC conjugate (cat. no. AP501F, RRID: AB_805334; EMD Millipore, Temecula, CA), goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L), and Alexa Fluor 647 conjugate (cat. no. AP187SA6; EMD Millipore). The mouse on mouse polymer IHC Kit (cat. no. ab269452; Abcam; Tokyo, Japan) was used for optimization of the background after using the mouse monoclonal antibody.

For pre-embedding immuno-gold electron microscopy, cryostat sections on poly-l-lysine-coated plastic slides were pretreated with 0.1% saponin and incubated with CB1 antibody (5 μg/ml) overnight. The sections were subsequently reacted with goat anti-rabbit IgG (cat. no. 2003, Lot. #34C498, RRID: AB_2687591; Nanoprobes, Yaphank, NY) which are covalently linked with ultra small gold particles (1:100 in dilution) and treated for silver enhancement using a kit (cat. no. 500.01, Aurion R-GENT SE-LM silver enhancement kit; Aurion, Hatfield, PA).

Results

In our recent study, 6 the expression of CB1 in the ovary of adult female mice was confirmed with a band of 51 kDa in Western blots, whose size is compatible with that reported in mouse brain with the same antibody. 7

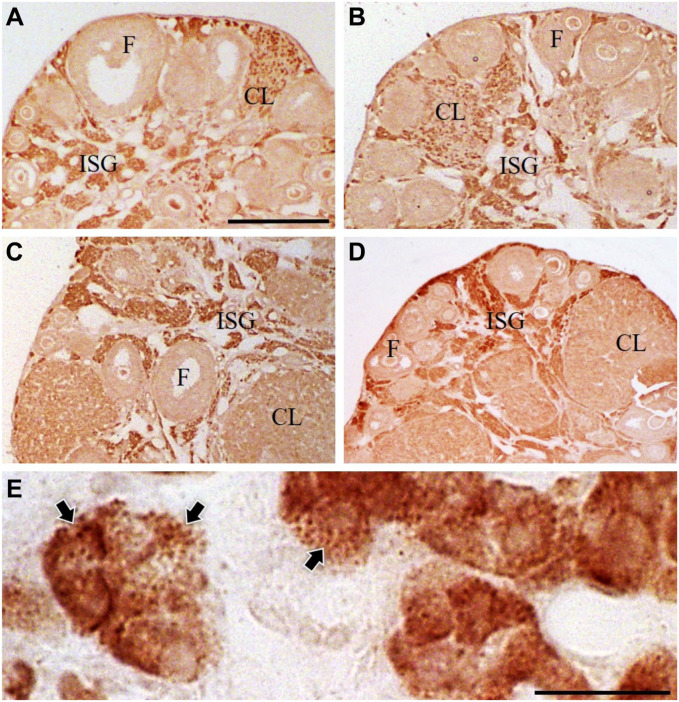

In immuno-light microscopy, CB1 immunoreactivity was moderate to intense in a majority of cells in the interstitial glands, whereas it was seen in a substantial number of cells distributed randomly in corpora lutea, and its immunointensity was slightly lower than that in the interstitial gland cells. No immunoreactivity for CB1 was see in follicular cells of primordial, primary, secondary, or antral follicles (Fig. 1A–D). The population densities of the immunoreactive cells in the interstitial glands seemed to be stable among the four estrous stages (Fig. 1A–D), whereas those in the corpus luteum seemed different among the four stages with a tendency to the highest at the proestrus stage. The latter needs a quantitative analysis for further clarification. Because of this tendency, the following examination and description in immunoelectron microscopy were confined to the interstitial glands at the diestrus stage in this study. At higher magnification, CB1 immunoreactivity appeared in forms of fine granules in some cells, especially in much thinly sectioned specimens, whereas it appeared rather diffusely throughout the cytoplasm in some other cells (Fig. 1E). No significant immunoreactivity was found in nuclei.

Figure 1.

Immuno-DAB light micrographs for cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1) of ovarian interstitial cells of mice at the four estrous stages (A: proestrus, B: estrus, C: metestrus; D: diestrus) and at the diestrus stage (E). Note no significant differences in the immunointensity in the interstitial glands (ISG) among the four estrous stages. Also note somehow differences in corpora lutea (CL) among the four stages, with the highest at the proestrus stage. Further note that CB1 immunoreactivity in some cells appears finely granular (black arrows) in the cytoplasm, whereas it appears rather diffuse in some other cells. F: healthy-looking follicles. Bars represent 500 μm (A–D), 25 μm (E).

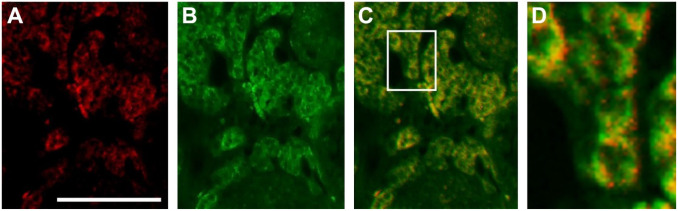

In double immunofluorescence microscopy, intensely CB1-immunoreactive materials were distributed slightly less congested than ATP5A-immunoreactive materials in individual cells in the same sections. In superimposed views of two immunofluorescence images, overlapping colored substructures appeared in forms of dots (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Double immunofluorescence micrographs for cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1) (A: red), ATP5A (B: green), and superimposed view of the two (C and D: yellow). An area enclosed by rectangle in (C) is shown at higher magnification in (D). Note, in the superimposed views, especially in (D), overlapping colored (yellow) substructures in forms of dots corresponding to mitochondria. Substructures with CB1 immunofluorescence appear slightly less congested than those with ATP5A immunofluorescence in the interstitial cells. Bars represent 100 μm (A–C), 25 μm (D).

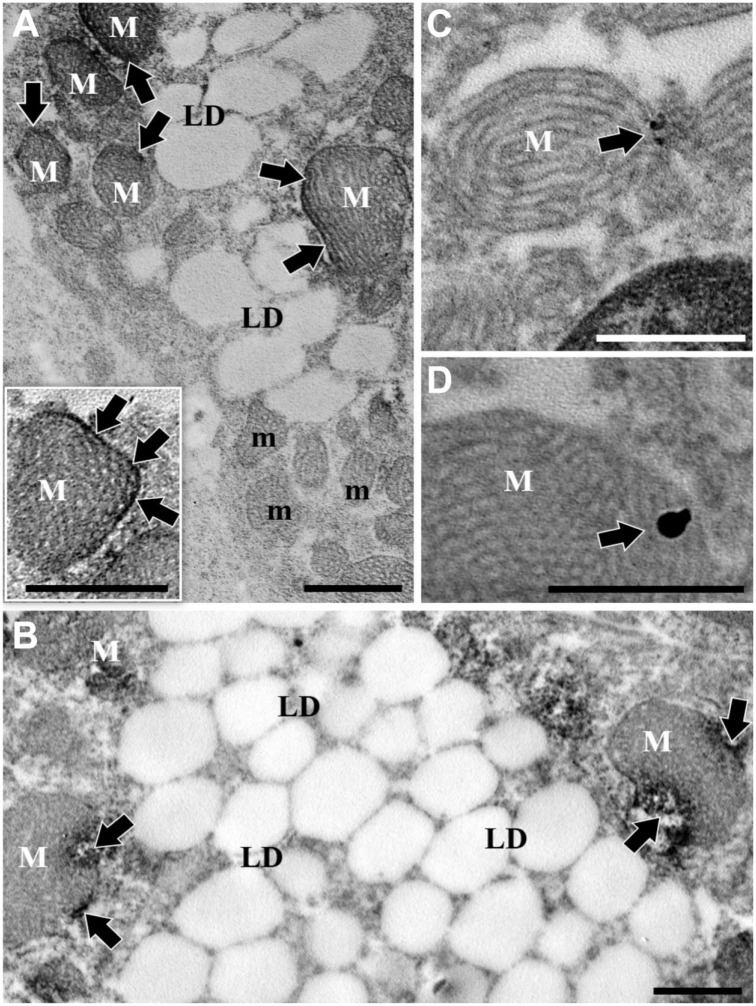

In immuno-DAB electron microscopy, cells immunoreactive for CB1 were characterized by mitochondria containing tubular cristae and numerous lipid droplets. Electron-dense materials representing the immunoreaction were deposited mainly on the outer membranes or peripheral domains of mitochondria (Fig. 3A and B). The deposit sites of electron-dense materials were sometimes associated with circumscribed broken spots in mitochondria (Fig. 3B). Mitochondria without any immunoreactive materials despite having tubular cristae were also seen in the same cells as those containing immunoreactive mitochondria with tubular cristae (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Immuno-DAB (A, B) and immuno-gold (C, D) electron micrographs for cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1) of interstitial gland cells characterized by relatively large mitochondria (M) having tubular cristae and lipid droplets (LD). (B) represents specimens immuno-DAB incubated slightly longer than (A). Note in (A) and its inset immunopositive mitochondria (M) showing higher electron densities dominantly on outer membranes (arrows), together with immunonegative mitochondria (m) with evenly low electron densities in one and the same cell. Also, note in (B) electron-dense materials deposited in outer mitochondrial domains and tiny broken spots within some of them (arrows). Further note in (C) and (D) a few immuno-gold particles (arrows) on mitochondrial outer membranes and no particles in extra-mitochondrial cell domains including the nucleus (N). Bars represent 800 nm.

In immuno-gold electron microscopy, only a few gold particles representing the immunoreaction were seen on the outer mitochondrial membranes (Fig. 3C and D).

In addition to the immunoreactive cells that comprised a majority of cell population in the interstitial glands, a minority of cells were found to be immunonegative for CB1 and distributed widely throughout the glands. They were characterized by smaller mitochondria having lamellar cristae (data not shown).

In the control experiment for CB1 immunoreactivity, no significant immunoreaction was detected throughout the ovary at the four estrous stages (data not shown).

Discussion

This is the first report on the detection, in ovarian interstitial gland cells, of CB1 immunoreactivity on the outer membranes of mitochondria having tubular cristae which are generally considered to be typical of progesterone-producing cells. The mitochondrial localization of CB1 was confirmed by double immunofluorescence microscopy using the mitochondria-specific marker ATP5A and by immuno-DAB and immuno-gold electron microscopy.

Although CB1 receptors, a G-protein-coupled receptor, are localized primarily in the plasma membrane, there have recently been evidence suggesting the presence of functional intracellular CB1 receptors, such as in spermatozoa 8 and skeletal muscle fibers,9,10 as well as in neurons and astrocytes of the brain.11–14 Most of the published studies have used immuno-golds as a marker for antigen–antibody reaction sites on tissue sections. The immuno-gold immunohistochemistry is generally regarded as superior to the immuno-DAB one which is stated to have a risk of diffusion of DAB-reaction materials beyond the real site of antigen–antibody reaction, although such a risk seems to be exaggerated. The DAB-reaction sites are sometimes associated with tiny broken spots in addition to electron-dense deposits. The phenomena are generally considered to be by-products of the antigen–antibody reaction and related ones, which can be somehow regulated by the control of the incubation time and could rather help in identification of immunoreaction sites. 15 This was the case in the present mitochondria of the immunoreactive cells. Although there are no methods free of demerits, the labeling of only one or two gold particles may often cause frustration to interpreters on reliable localization of molecules in such small targets as mitochondria. This is the case for most previous studies on mitochondrial localization of CB1 cited above. In cases of such small targets relative to the ultrathin section thickness as intramitochondrial domains, cryo-ultrathin sectioning, subsequent immuno-gold staining, and covering thereafter with epoxy resin are at present the best way to obtain findings almost free of skepticism. 16 This method is, however, too difficult to perform for the routine analysis. Therefore, this study first employed the alternative and popular method of immunostaining with golds using light microscopic cryo-sections, subsequent epon-embedment, and ultrathin sectioning as described in the “Materials and Methods” section. As a result, only a few gold particles were rather sporadically detected on peripheral portions of mitochondria as shown in Fig. 3C and D, at levels not dissimilar to the other studies reporting on the mitochondrial localization of CB1 cited above. In contrast, as shown in Fig. 3A and B, the occurrence of mitochondria exhibiting CB1 immunoreactivity by DAB as a marker was relatively numerous and constant and well corresponded to the immuno-DAB light microscopic images shown in Fig. 1. Therefore, the present DAB immunoreactivity for CB1 discerned in electron microscopy was regarded as representing CB1 in mitochondria. Admittedly, it is critical to examine the immunoreactive localization in the ovary of CB1-gene knockout mice for final confirmation of the present immunoreaction, although antigen preabsorption as a control for the authentic immunoreaction showed the negative result. Such mutant mice are not available yet at our hand at present, unfortunately.

What is the functional role of this localization in the cells? The first to consider is an involvement of eCB in the modulation of the progesterone synthesis. Needless to say, the interstitial gland is a site of active synthesis and secretion of progesterone in the ovary, and there have been studies showing the localization of immunoreactivities for key enzymes for progesterone synthesis such as cytochrome P450 in the interstitial gland cells. 17 It is known that cholesterol is transported from lipid droplets into the mitochondria, in which the synthesis of progesterone is processed on demand, in the interstitial gland cells. 18 The activation of mitochondrial CB1 has been shown to decrease mitochondrial mobility, which is probably linked to reduced mitochondrial metabolism and decrease in flux through intramitochondrial electron transport chain, oxygen consumption, and energy reduction. 19 It is thus tempting to consider that the activation of mitochondrial CB1 may suppress the synthesis of progesterone. This consideration seems to be compatible with the higher level of steroidogenesis in corpora lutea, 20 whose immunoreactivity for CB1 was lower than the interstitial cells. It is necessary to examine how the activity of cytochrome P450 is modulated by eCBs in biochemistry and molecular biology. In this regard, it should also be noted that the immunoreactive deposits for CB1 were not associated with all mitochondria in a given immunopositive cell. Such a heterogeneity in the immunoreactivity may indicate that the extent of involvement of mitochondrial CB1 in supposed functions is various within the given steroidogenic cells.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: AK contributed to the experimental design and performed the experiments, data analysis, and interpretation. JS contributed to perform the experiments, data analysis, and interpretation. MW contributed to synthesis of the antibody, data analysis, and interpretation and made critical revisions to the drafted manuscript. HK and WH contributed to the experimental design and made critical revision to the drafted manuscript. SC contributed to the experimental design and interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript, figures, and references prior to submission.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was granted by Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Thailand (Grant Number IN63338).

ORCID iD: Surang Chomphoo  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2879-5127

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2879-5127

Contributor Information

Anussara Kamnate, Electron Microscopy Unit, Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand; Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Princess of Naradhiwas University, Narathiwat, Thailand.

Juthathip Sirisin, Electron Microscopy Unit, Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand.

Masahiko Watanabe, Department of Anatomy, Graduate School of Medicine, Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan.

Hisatake Kondo, Electron Microscopy Unit, Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand; Department of Anatomy, Graduate School of Medicine, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan.

Wiphawi Hipkaeo, Electron Microscopy Unit, Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand.

Surang Chomphoo, Electron Microscopy Unit, Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand.

Literature Cited

- 1. Battista N, Bari M, Maccarrone M. Endocannabinoids and reproductive events in health and disease. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2015;231:341–65. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-20825-1_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Agirregoitia E, Peralta L, Mendoza R, Expósito A, Ereño ED, Matorras R, Agirregoitia N. Expression and localization of opioid receptors during the maturation of human oocytes. Reprod Biomed Online. 2012;24(5):550–7. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cecconi S, Rossi G, Oddi S, Di Nisio V, Maccarrone M. Role of major endocannabinoid-binding receptors during mouse oocyte maturation. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(12):2866. doi: 10.3390/ijms20122866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. El-Talatini MR, Taylor AH, Elson JC, Brown L, Davidson AC, Konje JC. Localisation and function of the endocannabinoid system in the human ovary. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(2):e4579. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. López-Cardona AP, Sánchez-Calabuig MJ, Beltran-Breña P, Agirregoitia N, Rizos D, Agirregoitia E, Gutierrez-Adán A. Exocannabinoids effect on in vitro bovine oocyte maturation via activation of AKT and ERK1/2. Reproduction. 2016;152(6):603–12. doi: 10.1530/REP-16-0199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kamnate A, Sirisin J, Polsan Y, Chomphoo S, Watanabe M, Kondo H, Hipkaeo W. In situ localization of diacylglycerol lipase α and β producing an endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol and of cannabinoid receptor 1 in the primary oocytes of postnatal mice. J Anat. 2021;238:1330–40. doi: 10.1111/joa.13392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yoshida T, Fukaya M, Uchigashima M, Miura E, Kamiya H, Kano M, Watanabe M. Localization of diacylglycerol lipase-alpha around postsynaptic spine suggests close proximity between production site of an endocannabinoid, 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol, and presynaptic cannabinoid CB1 receptor. J Neurosci. 2006;26(18):4740–51. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0054-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Aquila S, Guido C, Santoro A, Perrotta I, Laezza C, Bifulco M, Sebastiano A. Human sperm anatomy: ultrastructural localization of the cannabinoid1 receptor and a potential role of anandamide in sperm survival and acrosome reaction. Anat Rec (Hoboken). 2010;293(2):298–309. doi: 10.1002/ar.21042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Arrabal S, Lucena MA, Canduela MJ, Ramos-Uriarte A, Rivera P, Serrano A, Pavón FJ, Decara J, Vargas A, Baixeras E, Martín-Rufián M, Márquez J, Fernández-Llébrez P, De Roos B, Grandes P, Rodríguez de, Fonseca F, Suárez J. Pharmacological Blockade of cannabinoid CB1 receptors in diet-induced obesity regulates mitochondrial dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase in muscle. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(12):e0145244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mendizabal-Zubiaga J, Melser S, Bénard G, Ramos A, Reguero L, Arrabal S, Elezgarai I, Gerrikagoitia I, Suarez J, Rodríguez De, Fonseca F, Puente N, Marsicano G, Grandes P. Cannabinoid CB1 receptors are localized in striated muscle mitochondria and regulate mitochondrial respiration. Front Physiol. 2016;7:476. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bénard G, Massa F, Puente N, Lourenço J, Bellocchio L, Soria-Gómez E, Matias I, Delamarre A, Metna-Laurent M, Cannich A, Hebert-Chatelain E, Mulle C, Ortega-Gutiérrez S, Martín-Fontecha M, Klugmann M, Guggenhuber S, Lutz B, Gertsch J, Chaouloff F, López-Rodríguez ML, Grandes P, Rossignol R, Marsicano G. Mitochondrial CB1 receptors regulate neuronal energy metabolism. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(4):558–64. doi: 10.1038/nn.3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gutiérrez-Rodríguez A, Bonilla-Del Río I, Puente N, Gómez-Urquijo SM, Fontaine CJ, Egaña-Huguet J, Elezgarai I, Ruehle S, Lutz B, Robin LM, Soria-Gómez E, Bellocchio L, Padwal JD, van der Stelt M, Mendizabal-Zubiaga J, Reguero L, Ramos A, Gerrikagoitia I, Marsicano G, Grandes P. Localization of the cannabinoid type-1 receptor in subcellular astrocyte compartments of mutant mouse hippocampus. Glia. 2018;66(7):1417–31. doi: 10.1002/glia.23314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hebert-Chatelain E, Reguero L, Puente N, Lutz B, Chaouloff F, Rossignol R, Piazza PV, Benard G, Grandes P, Marsicano G. Cannabinoid control of brain bioenergetics: exploring the subcellular localization of the CB1 receptor. Mol Metab. 2014;3(4):495–504. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hebert-Chatelain E, Desprez T, Serrat R, Bellocchio L, Soria-Gomez E, Busquets-Garcia A, Pagano Zottola AC, Delamarre A, Cannich A, Vincent P, Varilh M, Robin LM, Terral G, García-Fernández MD, Colavita M, Mazier W, Drago F, Puente N, Reguero L, Elezgarai I, Dupuy JW, Cota D, Lopez-Rodriguez ML, Barreda-Gómez G, Massa F, Grandes P, Bénard G, Marsicano G. A cannabinoid link between mitochondria and memory. Nature. 2016;539(7630):555–9. doi: 10.1038/nature20127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cuello AC, Priestley JV, Sofroniew MV. Immuno-cytochemistry and neurobiology. Q J Exp Physiol. 1983;684:545–78. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1983.sp002748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Möbius W, Posthuma G. Sugar and ice: immunoelectron microscopy using cryosections according to the Tokuyasu method. Tissue Cell. 2019;57:90–102. doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gray SA, Mannan MA, O’Shaughnessy PJ. Development of cytochrome P450 aromatase mRNA levels and enzyme activity in ovaries of normal and hypogonadal (hpg) mice. J Mol Endocrinol. 1995;14(3):295–301. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0140295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shen WJ, Azhar S, Kraemer FB. Lipid droplets and steroidogenic cells. Exp Cell Res. 2016;340(2):209–14. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Djeungoue Petga -MA, Hebert-Chatelain E. Linking mitochondria and synaptic transmission: the CB1 receptor. Bioessays. 2017;39(12):1700126. doi: 10.1002/bies.201700126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eckery DC, Juengel JL, Whale LJ, Thomson BP, Lun S, McNatty KP. The corpus luteum and interstitial tissue in a marsupial, the brushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula). Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;191(1):81–7. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]