Abstract

Purpose:

Sexual side effects after breast cancer treatment are common and distressing to both survivors and their intimate partners, yet few receive interventions to address cancer-related sexual concerns. To direct intervention development, this qualitative study assessed the perceptions of female breast cancer survivors, intimate partners of breast cancer survivors, and breast cancer oncology providers about how an Internet intervention for couples may address breast cancer-related sexual concerns.

Methods:

Survivors (N=20) responded to online open-ended surveys. Partners (N=12) and providers (N=8) completed individual semi-structured interviews. Data were inductively coded using thematic content analysis.

Results:

Three primary intervention content areas were identified by the key stakeholder groups: (1) information about and strategies to manage physical and psychological effects of cancer treatment on sexual health, (2) relationship and communication support, and (3) addressing bodily changes and self-image after treatment. Survivors and partners tended to express interest in some individualized intervention private from their partner, although they also emphasized the importance of opening communication about sexual concerns within the couple. Survivors and partners expressed interest in an intervention that addresses changing needs across the cancer trajectory, available from the time of diagnosis and through survivorship.

Conclusion:

An Internet intervention for couples to address cancer-related sexual concerns, particularly one that provides basic education about treatment side effects and that evolves with couples’ changing needs across the cancer trajectory, was perceived as a valuable addition to breast cancer care by survivors, partners, and providers.

Keywords: Breast neoplasms, Cancer survivors, Internet-based intervention, Qualitative research, Sexual dysfunction, Spouses

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer and the associated treatments can potentially impact every phase of a woman’s sexual response cycle [1,2] and her perceived femininity, desirability, and body satisfaction [3]. As a result, breast cancer survivors report more sexual health concerns relative to women without history of cancer treatment [4], with 70 to 77% of survivors reporting clinically significant symptoms of sexual dysfunction [4–6]. Breast cancer survivors have described sexual side effects of treatment as among their most distressing cancer-related challenges [7–9], yet fewer than one in three report receiving any kind of information or intervention to address their cancer-related sexual side effects [10].

Less is known regarding the experiences of the romantic partners of breast cancer survivors. Available data suggest that partners have difficulty navigating sexual concerns with the survivor [11,12]. Fittingly, survivors consistently report a strong preference for their partners to be included in efforts to address sexual side effects from cancer, emphasizing the importance of addressing communication, relationship, and intimacy issues [9,13]. Communication- and intimacy-based intervention components that help couples openly and comprehensively address cancer-related sexual concerns are essential [14,15], yet have been described as “the most overlooked aspect of therapy for sexual dysfunction” for cancer survivors [16].

Internet interventions are uniquely positioned to overcome common barriers that have traditionally limited access to comprehensive efforts to address breast cancer-related sexual functioning challenges, such as limited appointment time and discomfort discussing a sensitive subject [17,18]. An Internet intervention is a program comprising behavioral, psychological, and/or educational components that is delivered through the Internet [19]. Internet interventions have particular utility for interventions for couples [20], and both survivors and partners have expressed interest in Internet resources related to sexual functioning given the privacy and convenience the Internet affords [9,13]. Intervention delivered via the Internet might also be particularly useful in reaching couples who decline more traditional provider-delivered sexual health interventions [21]. To date, Internet interventions addressing cancer-related sexual concerns have primarily focused on managing the needs of the cancer survivor without comprehensively addressing partner concerns or relational difficulties [22].

Understanding perspectives from multiple key stakeholders – survivors and partners who might use such an intervention, and providers who might recommend it – is needed to develop acceptable, comprehensive, and sustainable interventions for couples impacted by breast cancer. Taking a phenomenological approach, this qualitative study aimed to assess the perceptions of female breast cancer survivors, intimate partners of breast cancer survivors, and breast cancer oncology providers about how an Internet intervention for couples may effectively anticipate and address common breast cancer-related sexual concerns.

METHODS

Procedures

This study was approved as exempt research by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Virginia. Supplementary materials – including interview guides and COREQ checklist – are archived at http://bit.ly/BrCaQual. Participants were recruited from the University of Virginia Breast Care Center from October 2019 through April 2020. Eligible survivors included women aged 45–65 with a diagnosis of stage I-III breast cancer who were between 6 months to 5 years from their final breast cancer treatment (chemotherapy, radiation, or surgery); active treatment with adjuvant endocrine therapy was permitted. Potentially eligible survivors were identified through medical record review and approached by a nurse at their Breast Care Center appointment, and interested survivors returned a recruitment card with their contact information. Partners were either self-referred via in-clinic recruitment materials or referred by survivors on their recruitment cards. Partners were eligible if they were aged 18 or older and in a romantic relationship with a female breast cancer survivor. All of the Breast Care Center-affiliated surgeons, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, and nurse practitioners were eligible to participate, excluding SS, who was a study team member. All data collection was conducted in English, and all participants (survivors, partners, and providers) provided informed consent to participate.

Data Collection

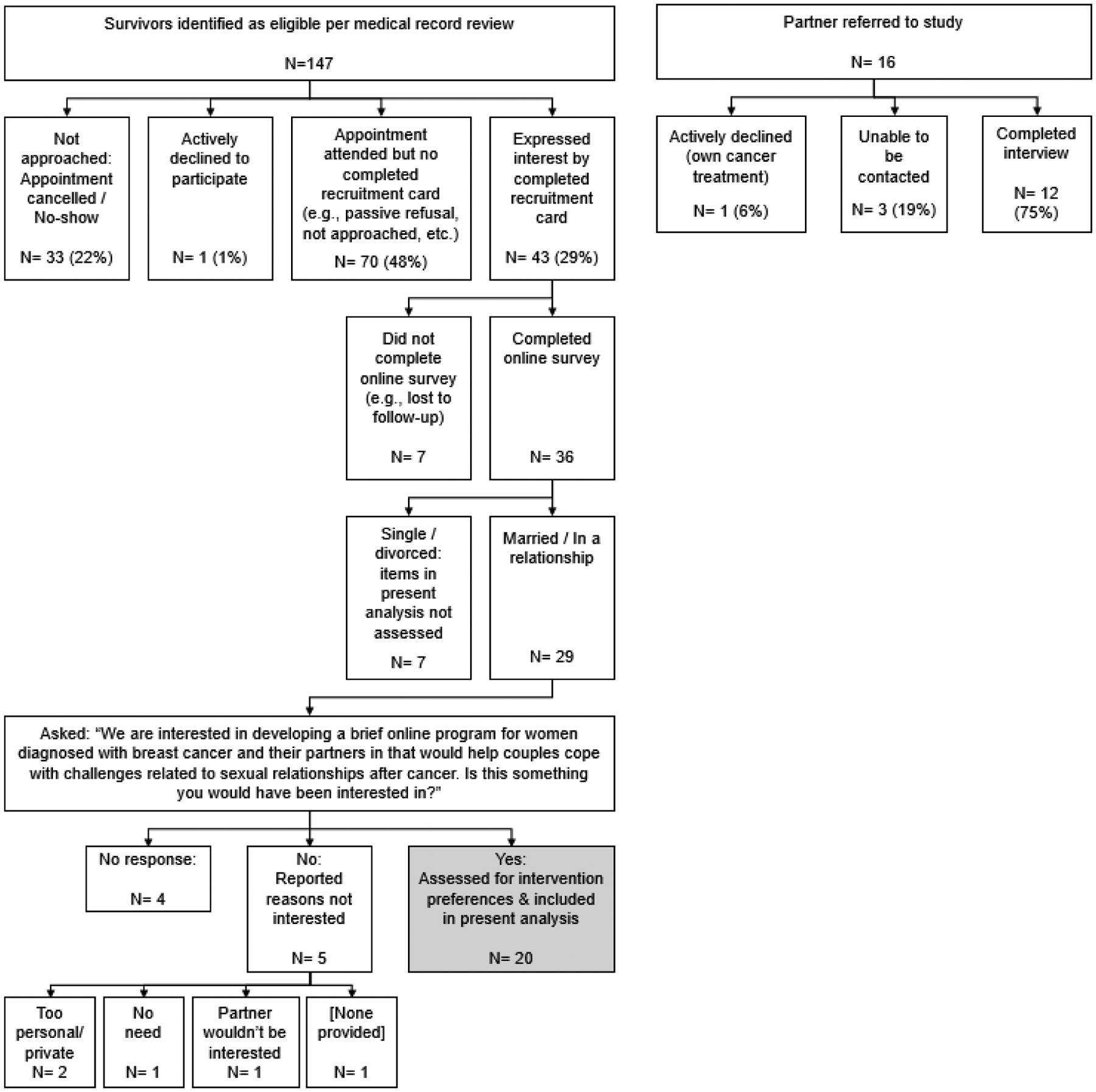

Recruitment data for survivors and partners is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Recruitment Data for Survivors and Partners

Survivors.

Interested survivors were emailed a link to complete HIPAA-compliant study surveys via Qualtrics. Within the survey, survivors who indicated they were in a romantic relationship and would be interested in an Internet intervention for couples addressing cancer-related sexual concerns were prompted with free-response items assessing their preferences related to the content and delivery of such an intervention.

Partners.

Partners completed audio-recorded semi-structured interviews with EK by telephone. Partners self-reported demographics and responded to a survey of their current sexual satisfaction, as well as prompts assessing their perceptions regarding the effect of their partners’ breast cancer and related treatment on their intimate relationship and their preferences related to the content and delivery of an Internet intervention for couples to address cancer-related sexual concerns. Partners were recruited to reach thematic saturation, which was achieved by 12 interviews (see Supplementary Table 2 for saturation data table).

Providers.

Providers completed audio-recorded semi-structured interviews with EK in-person. Providers responded to prompts regarding how technology may help address sexual concerns among their patients.

Data Analysis

Survivors.

Open-ended survey responses were inductively coded separately by KMS and EK. Upon completion, KMS and EK reviewed coding results together and resolved coding conflicts by consensus.

Partners and providers.

Partner and provider interview recordings were transcribed using automated transcription software (https://trint.com/) then reviewed by trained research assistants. Transcripts were coded in Dedoose software (https://www.dedoose.com/). Partner and provider interviews were coded separately; both sets of interviews were iteratively coded using inductive thematic content analysis. Starting with the provider interviews, three coders (KMS, EK, & JVG) began by each individually coding the same three interviews and then met to review generated codes. These first-round codes were refined by consensus, and then the transcripts and refined codes were reviewed with other members of the study team (AHC, WC, SS). The coders then proceeded iteratively: each coder individually coded two of the next three interviews such that each interview was double-coded, then coding was reviewed together to resolve conflicts, codes were refined, and coding for previously coded interviews was revised as necessary, until all interviews in the provider set were coded. The process was then repeated for the set of partner interviews.

RESULTS

Survivor and partner sample descriptives are listed in Table 1. Although recruitment was not limited to heterosexual relationships, all participating partners were male. Survivors, on average, self-reported their sexual functioning to be within the range of clinically significant sexual dysfunction. Partners, on average, self-reported good sexual functioning. All 8 eligible providers completed an interview – of these, 3 were men and 5 were women. Select quotes from survivors, partners, and providers are presented in-text; additional representative quotes from partner and provider interviews are listed in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Table 1.

Survivor and Partner Demographics

| Demographic information (Self-report) | Survivor (N=20) N (%) unless specified |

Partner (N=12) N (%) unless specified |

|---|---|---|

| Range | 45 – 65 | 36 – 70 |

| Race / ethnicity | ||

| African American / Black | 0 (0%) | 1 (8%) |

| Asian | 0 (0%) | 2 (17%) |

| Hispanic / Latinx | 2 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 17 (85%) | 9 (75%) |

| Multiracial | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Education | ||

| High school degree or less | 1 (5%) | 1 (8%) |

| Associate’s Degree or some college | 5 (25%) | 2 (17%) |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 4 (20%) | 1 (8%) |

| Some graduate school | 2 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

| Graduate Degree | 8 (40%) | 8 (67%) |

| Relationship duration | ||

| 5 to <10 years | 1 (5%) | 2 (17%) |

| 10 to <20 years | 4 (20%) | 4 (33%) |

| 20 years or longer | 15 (75%) | 6 (50%) |

| Cancer diagnosis and treatment information (Electronic Medical Record) | Survivor (N=20) N (%) unless specified |

Partners’ wives (N=10*) N (%) unless specified |

| Stage | ||

| I | 11 (55%) | 7 (70%) |

| II | 8 (40%) | 3 (30%) |

| II/III | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Range | 6.73 – 60.40 | 9.17 – 60.03 |

| Breast surgery**† | ||

| Mastectomy | 11 (55%) | 6 (60%) |

| Lumpectomy | 10 (50%) | 3 (30%) |

| None ever | 0 (0%) | 1 (10%) |

| Breast radiation** | ||

| External | 11 (55%) | 5 (50%) |

| Intraoperative | 3 (15%) | 1 (10%) |

| None ever | 6 (30%) | 4 (40%) |

| Received chemotherapy | 7 (35%) | 3 (30%) |

| Endocrine therapy** | ||

| Tamoxifen | 8 (40%) | 4 (40%) |

| Exemestane | 0 (0%) | 1 (10%) |

| Anastrozole | 4 (20%) | 2 (20%) |

| Letrozole | 6 (30%) | 1 (10%) |

| None ever | 4 (20%) | 3 (30%) |

| Sexual functioning (Self-report) | Survivor (N=20) M (SD) |

Partner (N=12) M (SD) |

| PROMIS Sexual Functioning (T-score; M=50, SD=10 in U.S. adults; higher scores = better functioning [35]) | 47.47 (9.24) | 56.38 (9.27) |

| Female Sexual Function Index (scores ≤ 26 indicative of sexual dysfunction [36,37]) | 23.58 (6.06) | – |

| Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire (scores ≤ 41 indicative of sexual dysfunction [38]) | 37.74 (9.72) | – |

| Relationship Assessment Scale (mean scores range 1 to 5, higher scores = better relationship satisfaction [39]) | 4.24 (0.68) | – |

Data for the wives of 2 partners not available

Patients were counted if they ever had a procedure or ever were prescribed an endocrine therapy for their breast cancer

Two patients’ records indicated they had completed both a lumpectomy and a mastectomy

Desired Content for an Internet Intervention for Couples Targeting Cancer-Related Sexual Concerns

Three primary intervention content areas were identified by the 3 key stakeholder groups as important to include in an intervention for couples: (1) information about and strategies to manage physical and psychological effects of cancer treatment on sexual health, (2) relationship and communication support, and (3) addressing bodily changes and self-image after treatment. Responses are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Survivor, partner, and provider preferences for topics to be covered by an Internet-delivered program on sexual health for couples following breast cancer

| Topic | Survivor (N=20) | Partner – for themselves (N=12) | Provider – for survivors (N=8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| For themselves | For their partners | |||

| Information about and strategies to manage physical and psychological effects of treatment on sexual health | 16 (80%) | 12 (60%) | 5 (42%) | 6 (75%) |

| Relationship and communication support | 6 (30%) | 14 (70%) | 2 (17%) | 2 (25%) |

| Addressing bodily changes and self-image after treatment | 13 (65%) | 7 (35%) | 1 (8%) | 2 (25%) |

Information about effects of cancer treatment.

The intervention content for survivors and partners most frequently endorsed as important by the 3 key stakeholder groups included information about how breast cancer and its treatments physically and psychologically impact survivors’ sexual functioning, as well as basic strategies for how these impacts might be mitigated. Survivors commonly requested information for both themselves and their partners related to helping them understand why they were experiencing sexual problems, ways to comfortably continue being physically intimate, and managing vaginal dryness and pain with intercourse. Concerns about libido were also prevalent among survivor responses – one survivor captured these concerns with her questions, “Why don’t I want to have sex anymore? Why is my libido so lame?”

Partners also stated that having this information would help them prepare, adjust, and cope. One partner wished he had more information so he could have helped “preempt some of these problems, rather than deal with them afterwards.” Partners identified specific concerns related to the survivors’ libido and pain. For instance, partners noted how the survivors’ sexual desire “disappeared” and one partner wondered if his wife was having sex with him just because “she doesn’t want to let me down.” This concern that sex was no longer enjoyable for the survivors was prevalent among partners, suggesting the value of providing information to partners about how to be physically intimate in ways that may be more comfortable for survivors.

Providers regarded the ability for information about sexual concerns and their management to be available to survivors “instantaneously” and “outside formal [appointment] time” as an important benefit of an Internet intervention. Providers discussed the importance of survivors having access to sexual functioning information as it facilitates productive clinical discussions. One provider highlighted how survivors often “use technology first to search for answers, before they even approach a provider,” so having vetted information about sexual symptoms and potential treatments available through an Internet intervention would help survivors and providers have “more informed discussions.” Other providers similarly discussed how this kind of education would empower survivors to more clearly identify sexual side effects of their treatment and then describe “what their issue is in a way that, as a provider, I can effectively help.”

Relationship and communication support.

Survivors commonly requested that a potential intervention cover topics specific to restoring and enhancing relational intimacy, gaining support from their partner, and discussing sexual concerns candidly. Survivors especially reported wanting their partners to have access to this information – for instance, how to provide effective support to the survivor and how to communicate openly about sexual changes to “address the ‘elephant’ in the room.”

Although partners did not often spontaneously request intervention content related to relationship and communication support, partner interviews revealed themes suggesting they placed great importance on providing emotional support to the survivor. One partner described his key advice to other partners of women diagnosed with breast cancer as “you’ve got to be there for your spouse and just be supportive,” suggesting partners may value intervention content that directly addresses restoring and maintaining emotional intimacy. Relatedly, partners commonly discussed how communication was essential to their ability to support the survivors’ adjustment to diagnosis and treatment. Some partners talked about how they worked to be “diplomatic” to avoid upsetting the survivor – one partner said, “it was very important to me to be very supportive and say nothing negative.” Another partner, however, discussed how this kind of censorship drove a wedge between him and his wife, saying it was “not until I was truthful one on one with the communication that things started changing.” Other partners similarly talked about how discussing sexual concerns with the clinical care team helped “affirm what we were going through,” whereas another partner discussed how lack of open communication about sexual concerns left him “feeling alone in all that… because nobody else is talking about it.”

Providers, too, addressed the utility of broadly normalizing discussions about sexual concerns following a breast cancer diagnosis. One provider felt intervention content for survivors on how to communicate about sexual concerns is important “because that’s probably where it all falls down. So teaching [survivors] it’s OK to talk to providers and talk to your partners about it” would help survivors get the care they need. Providers also indicated that a resource to mitigate relational consequences of sexual side effects would be important, given how physical sexual symptoms “affect [survivors’] interactions with their loved ones,” and can result in “fractured relationships, loss of intimacy – even non-sexual intimacy… because of loss of desire.”

Addressing bodily changes and self-image.

Survivors commonly requested support on “liking one’s body again” following their breast cancer treatments. One survivor wrote, “losing, or changing, a part of my femininity has played a big part of not only my treatment choices, but also how comfortable I am with looking at or sharing my body now.” While survivors most commonly requested this kind of information for themselves, many also indicated that it may be useful for their partners. One survivor wrote, “How does he cope with his wife’s body never looking ‘right’ again?”

While partners less frequently generated the topic of survivor’s self-image as important to address in an intervention, they did commonly discuss the survivor’s lowered self-esteem following treatments. One partner described trying to encourage his wife, when she would sometimes have “low self-confidence, saying, ‘Oh, you can divorce me.’” Another partner described how he felt his wife, following mastectomy and reconstruction, “didn’t feel like she was beautiful anymore and didn’t feel like I was attracted to her, and we grew apart.”

Providers also did not tend to generate the topic of survivors’ self-image as an area of content to address in an intervention. They did, however, commonly discuss how physical sexual side effects from treatment frequently lead to “issues related to self-image and perceived sexuality,” which were recognized to be in large part responsible for distress related to these side effects. Providers discussed how these psychological issues fell largely outside of what they are typically able to address with their patients due to limited appointment time and expertise, and as such, they expressed value in having a vetted resource they could recommend to their patients to more comprehensively address these topics.

Desired Delivery Format for an Internet Intervention for Couples Targeting Cancer-Related Sexual Concerns

Survivors and partners were queried about their preferences regarding the delivery of an Internet intervention for couples. Responses are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Survivor and partner preferences for delivery of an Internet-delivered program on sexual health for couples following breast cancer

| Survivors (N=20) | Partners (N=12) | |

|---|---|---|

| Dyadic delivery * | ||

| Prefer all together | 0 (0%) | 3 (25%) |

| Prefer some separate content | 13 (65%) | 7 (58%) |

| Leave up to the couple | 1 (5%) | 2 (17%) |

| Unsure | 3 (15%) | 0 (0%) |

| No response | 2 (10%) | 1 (8%) |

| Timing of the intervention * | ||

| Before treatment / early / from beginning | 9 (45%) | 2 (17%) |

| After treatment | 5 (25%) | 2 (17%) |

| Ongoing | 5 (25%) | 1 (8%) |

| Specific to treatment (e.g., after surgery but before radiation) | 3 (15%) | 3 (25%) |

| Don’t know | 0 (0%) | 3 (25%) |

| No response | 2 (10%) | 1 (8%) |

Responses can reflect more than one preference/code

Dyadic delivery.

Survivors and partners were asked about a hypothetical dyadic intervention to address sexual concerns, in which couples engage in select intervention components together and other intervention components as individuals to address survivors’ and partners’ unique experiences separately. Most survivors felt this separation was a good idea. One survivor indicated “there are some things that the survivor needs to discuss privately;” another wrote that some privacy is important, as couples might “not have the opportunity to express their feelings unless they could do so in private without hurting the other partner.” Body image was commonly cited as a topic survivors preferred to address privately. As a diverging opinion, one survivor commented that she was “not sure [delivering content separately] is necessary – my initial thought is that it would be helpful to see things from both perspectives.”

Most partners also reported that some separate content would be beneficial, with one partner describing that, without some privacy, partners might avoid being “totally honest about their sexual relationship in fears of hurting their spouse.” Some partners, however, felt that separate content may inadvertently contribute to relationship problems. One partner noted that, “you’re both struggling apart and you’re disconnected, so you’re not really facing what’s really hurtful,” suggesting that it may be more helpful to go through a program together to increase their capability for candid discussion of difficult subjects. Another partner similarly noted that, “there’s two parties involved in the marriage relationship and there’s two parties involved in the effects of the surgery, so it seems like it ought to be a joint conversation.”

Timing of the intervention.

Regarding the potential timing of access to an Internet intervention designed to address cancer-related sexual concerns, most survivors indicated that they would have liked access closely following their breast cancer diagnosis. One woman commented how she had “started out on a path of sexual dysfunction” from before her surgery, so early information would have helped; another woman wrote that, despite the time around her diagnosis being “overwhelming,” that “it would be nice to know a resource is available to you when you are ready.”

Partners’ preferences on timing of the intervention were mixed. Some partners felt that access to information from the beginning would be important as “that’s the scariest period,” and it would have helped them be more proactive in addressing potential problems. Others felt that waiting until after treatments were complete would be more appropriate, thinking it might be “selfish to put forward [my] sexual needs when [the survivor] is going through all kinds of issues.”

Both survivors and partners did commonly indicate that an intervention that addressed changing needs across the cancer trajectory would be helpful. One survivor noted she would have liked to have an intervention addressing sexual concerns “throughout the whole process – [my concerns] changed as I went through surgery, treatment, and recovery.” A partner similarly remarked that it would have been helpful to have access to an intervention “through the duration of the whole process.”

DISCUSSION

This qualitative study collected the unique perspectives of 3 key stakeholder groups – breast cancer survivors, romantic partners of breast cancer survivors, and breast cancer providers – to understand how an Internet intervention may help anticipate and address cancer-related sexual concerns for both survivors and their partners. Three key intervention content areas were identified as important to comprehensively addressing couples’ sexual concerns: (1) information regarding the physical and psychological effects of breast cancer and its treatment on women’s sexual functioning – as well as strategies to mitigate these effects, (2) relationship and communication support, and (3) addressing bodily changes and self-image after treatment. Survivors and partners tended to express interest in some individualized intervention private from their partner, although they also emphasized the importance of opening honest communication about sexual concerns within the couple. In addition, an intervention that addresses couples’ changing needs across the cancer trajectory was desired.

Survivors, partners, and providers all reported that greater access to foundational education about how breast cancer and various treatments may affect women’s biopsychosocial sexual well-being was essential for women to get the support they need from their partners and care they need from their providers. Indeed, most cancer survivors’ sexual concerns can be addressed with educational interventions alone [23,24], and reviews of sexual health interventions for breast cancer survivors recommend couples-based educational approaches [1,25]. With the capability of providing tailored information to users discreetly and on-demand, Internet interventions are uniquely suited to make this kind of care more widely and routinely accessible to survivors and their partners, which was perceived as a key benefit by survivors, partners, and providers alike.

While each of the stakeholder groups independently raised the topic of basic information about sexual side effects as an important to include in an intervention, only survivors commonly raised the topics of relationship/communication and self-image as key to a comprehensive cancer-related sexual concerns intervention. Communication and sexual self-image challenges often are mutually reinforcing among female cancer survivors: a negative sexual self-concept engenders embarrassment and shame, limiting sexual behaviors and communication, which in turn restricts opportunities for positive sexual experiences and for sexual challenges to be addressed [26,27]. Survivors in our study commonly expressed interest in addressing body image concerns privately from their partner; however, restricted communication between couples about the survivor’s body can result in tension, conflict, and withdrawal [28] – themes that were also reflected in the partner interviews in the current study. Findings suggest the benefit of a dyadic approach that integrates intervention components targeted to the unique needs of each member of the couple paired with an early emphasis on opening candid, productive communication about the wide-ranging effects of cancer treatment on intimacy.

Beyond the content of the intervention itself, survivors and partners expressed interest in having an intervention available across the cancer trajectory. Both survivors and partners discussed the utility of having such an intervention available early, even at the point of diagnosis, in order for sexual side effects to be more readily identified, understood, and managed from the outset. Not all survivors and partners expressed that they would have engaged with the program early in the cancer trajectory – some survivors indicated they were preoccupied managing other symptoms and worries during treatment, and some partners expressed reserve regarding the appropriateness of considering their sexual relationships while their partners were in treatment. An Internet intervention may be uniquely situated to accommodate differing preferences and needs across survivors and partners, given that they can provide tailored content to individuals based on their current needs and interests, and can be continuously available for access when a survivor or partner is ready.

Although the primary purpose of the study focused on an Internet-delivered intervention for cancer-related sexual concerns, findings also hold implications for clinical practice. While acknowledging the barriers that are often cited to raising these discussions [17,18], findings suggest that providers raising the topic of sexual concerns to openly permit the discussion of the topic may offer important relief and validation to patients. Models for this communication include the PLISSIT model [29,30] and 5A’s model [31,32], which both emphasize the importance of this initial step of signaling to patients that discussion of sexual concerns is welcome. Internet interventions may be particularly helpful to carrying out the following steps in these models by serving as an accessible resource that providers may refer to their patients to receive tailored information about their specific concerns.

Limitations and Future Directions

Interpretations of findings are limited given the demographics of the participants and researchers. Our survivor, partner, and provider samples, as well as the study team, primarily comprise non-Hispanic White, highly educated, and heterosexual individuals. Data have therefore been generated and interpreted through these lenses and are not representative of the needs and preferences that reflect diversity in race, ethnicity, healthcare access and literacy, and sexual orientation. Given that individuals who identify with marginalized groups often experience greater barriers to accessing comprehensive survivorship care [33,34], incorporating their perspectives in the development of interventions will be required to ensure disparities are not reinforced. Moreover, the samples of survivors and partners tended to report being in long-term relationships. This means that findings may not be representative of the perspectives or needs of survivors and partners in newer relationships, who may not have as established trust or entrenched communication patterns as those in decades-long relationships.

Conclusions

An Internet intervention for couples to address potential cancer-related sexual concerns, particularly one providing basic education about physical and psychological side effects and that evolves with couples’ changing needs across the cancer trajectory, was perceived as a valuable addition to breast cancer care by survivors, partners, and providers.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT:

Authors are sincerely grateful for the participation of the survivors, partners, and providers in this study, for the support of the UVA Breast Care Center, and for the recruitment assistance of Dora Irvin, LPN.

FUNDING:

This study was funded by a UVA Cancer Center Cancer Control and Population Health Sciences (CCPH) program Population Research Pilot Projects award. Dr. Shaffer was supported in part by the NIH NCATS Award Numbers UL1TR003015 and KL2TR003016. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST/COMPETING INTERESTS:

Dr. Shaffer discloses funding from NCATS related to this work. Ms. Kennedy, Ms. Glazer, Dr. Cohn, Dr. Millard, and Dr. Showalter report no pertinent conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Clayton reports outside the submitted work grants from Janssen, Relmada Therapeutics, Inc., and Sage Therapeutics; personal fees from Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, AMAG Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Fabre-Kramer, Ovoca Bio plc, Pure Tech Health, Sage Therapeutics, Takeda/Lundbeck, WCG MedAvante-ProPhase, Ballantine Books/Random House, Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire, Guilford Publications; personal fees and other from S1 Biopharma; and other from Euthymics and Mediflix LLC. Dr. Ritterband reports having a financial and/or business interest in BeHealth Solutions and Pear Therapeutics and is a consultant to Mahana Therapeutics. These companies had no role in preparing this manuscript. The terms of these arrangements have been reviewed and approved by the University of Virginia in accordance with its policies.

Footnotes

ETHICS APPROVAL: This study was approved as exempt research by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Virginia.

CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

CONSENT TO PUBLISH: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Participants were informed that results would be reported. Data have been anonymized for publication.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIAL:

Data available upon reasonable request from the authors. Supplementary materials – including interview guides and COREQ checklist – are archived at http://bit.ly/BrCaQual.

REFERENCES

- 1.Seav SM, Dominick SA, Stepanyuk B, et al. : Management of sexual dysfunction in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. Women’s Midlife Health. 2015; 1:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cella D, Fallowfield LJ: Recognition and management of treatment-related side effects for breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008; 107:167–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schover LR: The impact of breast cancer on sexuality, body image, and intimate relationships. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 1991; 41:112–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oberguggenberger A, Martini C, Huber N, et al. : Self-reported sexual health: Breast cancer survivors compared to women from the general population–an observational study. BMC Cancer. 2017; 17:599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panjari M, Bell RJ, Davis SR: Sexual function after breast cancer. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2011; 8:294–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raggio GA, Butryn ML, Arigo D, Mikorski R, Palmer SC: Prevalence and correlates of sexual morbidity in long-term breast cancer survivors. Psychology & Health. 2014; 29:632–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fergus KD, Gray RE: Relationship vulnerabilities during breast cancer: patient and partner perspectives. Psycho-Oncology: Journal of the Psychological, Social and Behavioral Dimensions of Cancer. 2009; 18:1311–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ochsenkühn R, Hermelink K, Clayton AH, et al. : Menopausal status in breast cancer patients with past chemotherapy determines long-term hypoactive sexual desire disorder. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2011; 8:1486–1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reese JB, Porter LS, Casale KE, et al. : Adapting a couple-based intimacy enhancement intervention to breast cancer: A developmental study. Health Psychology. 2016; 35:1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flynn KE, Reese JB, Jeffery DD, et al. : Patient Experiences With Communication About Sex During and After Treatment for Cancer. Psychooncology. 2012; 21:594–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nasiri A, Taleghani F, Irajpour A: Men’s sexual issues after breast cancer in their wives: a qualitative study. Cancer Nursing. 2012; 35:236–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zahlis EH, Lewis FM: Coming to grips with breast cancer: the spouse’s experience with his wife’s first six months. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2010; 28:79–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leon-Carlyle M, Schmocker S, Victor JC, et al. : Prevalence of physiologic sexual dysfunction is high following treatment for rectal cancer: but is it the only thing that matters? Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 2015; 58:736–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yi JC, Syrjala KL: Sexuality after Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Cancer J. 2009; 15:57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shanis D, Merideth M, Pulanic TK, Savani BN, Battiwalla M, Stratton P: Female long-term survivors after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: evaluation and management. Seminars in Hematology. 2012; 49:83–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henson HK: Breast Cancer and Sexuality. Sexuality and Disability. 2002; 20:261–275. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ussher JM, Perz J, Gilbert E, et al. : Talking about sex after cancer: A discourse analytic study of health care professional accounts of sexual communication with patients. Psychology & Health. 2013; 28:1370–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coleman E, Elders J, Satcher D, et al. : Summit on medical school education in sexual health: report of an expert consultation. J Sex Med. 2013; 10:924–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ritterband LM, Thorndike FP, Cox DJ, Kovatchev BP, Gonder-Frederick LA: A behavior change model for Internet interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2009; 38:18–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaffer KM, Tigershtrom A, Badr H, Benvengo S, Hernandez M, Ritterband LM: Dyadic Psychosocial eHealth Interventions: Systematic Scoping Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2020; 22:e15509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reese JB, Sorice KA, Oppenheimer NM, et al. : Why do breast cancer survivors decline a couple-based intimacy enhancement intervention trial? Transl Behav Med. 2020; 10:435–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wootten A, Pillay B, Abbott J-A: Can sexual outcomes be enhanced after cancer using online technology? Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliative Care. 2016; 10:81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barbera L, Fitch M, Adams L, Doyle C, DasGupta T, Blake J: Improving care for women after gynecological cancer: the development of a sexuality clinic. Menopause. 2011; 18:1327–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schover LR, Evans RB, von Eschenbach AC: Sexual rehabilitation in a cancer center: diagnosis and outcome in 384 consultations. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1987; 16:445–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor S, Harley C, Ziegler L, Brown J, Velikova G: Interventions for sexual problems following treatment for breast cancer: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011; 130:711–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andersen BL, Woods XA, Copeland LJ: Sexual Self-Schema and Sexual Morbidity Among Gynecologic Cancer Survivors. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997; 65:221–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Emilee G, Ussher JM, Perz J: Sexuality after breast cancer: A review. Maturitas. 2010; 66:397–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rowland E, Metcalfe A: A systematic review of men’s experiences of their partner’s mastectomy: coping with altered bodies. Psycho-Oncology. 2014; 23:963–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Annon JS: The PLISSIT model: A proposed conceptual scheme for the behavioral treatment of sexual problems. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy. 1976; 2:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson JW, Lounsberry JJ: Communicating about sexuality in cancer care. In: Kissane D, Bultz B, Butow P, Finlay I, editors. Handbook of Communication in Oncology and Palliative Care. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. p. 409–422. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park ER, Norris RL, Bober SL: Sexual health communication during cancer care: barriers and recommendations. The Cancer Journal. 2009; 15:74–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bober SL, Reese JB, Barbera L, et al. : How to ask and what to do: A guide for clinical inquiry and intervention regarding female sexual health after cancer. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2016; 10:44–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lisy K, Peters MD, Schofield P, Jefford M: Experiences and unmet needs of lesbian, gay, and bisexual people with cancer care: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Psycho-Oncology. 2018; 27:1480–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yedjou CG, Tchounwou PB, Payton M, et al. : Assessing the racial and ethnic disparities in breast cancer mortality in the United States. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017; 14:486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weinfurt KP, Lin L, Bruner DW, et al. : Development and Initial Validation of the PROMIS® Sexual Function and Satisfaction Measures Version 2.0. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2015; 12:1961–1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. : The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000; 26:191–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiegel M, Meston C, Rosen R: The female sexual function index (FSFI): cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. J Sex Marital Ther. 2005; 31:1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clayton AH, McGarvey EL, Clavet GJ: The Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire (CSFQ): Development, reliability, and validity. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1997; 33:731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hendrick SS, Dicke A, Hendrick C: The relationship assessment scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1998; 15:137–142. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon reasonable request from the authors. Supplementary materials – including interview guides and COREQ checklist – are archived at http://bit.ly/BrCaQual.