ABSTRACT.

There has been a significant increase in the number of students, residents, and fellows from high-income settings participating in short-term global health experiences (STGHEs) during their medical training. This analysis explores a series of ethical conflicts reported by medical residents and fellows from Emory University School of Medicine in the United States who participated in a 1-month global health rotation in Ethiopia. A constant comparative analysis was conducted using 30 consecutive reflective essays to identify emerging categories and themes of ethical conflicts experienced by the trainees. Ethical conflicts were internal; based in the presence of the visiting trainee and their personal interactions; or external, occurring due to witnessed events. Themes within internal conflicts include issues around professional identity and insufficient preparation for the rotation. External experiences were further stratified by the trainee’s perception that Ethiopian colleagues agreed that the scenario represented an ethical conflict (congruent) or disagreed with the visiting trainee’s perspective (incongruent). Examples of congruent themes included recognizing opportunities for collaboration and witnessing ethical conflicts that are similar to those experienced in the United States. Incongruent themes included utilization of existing resources, issues surrounding informed consent, and differing expectations of clinical outcomes. By acknowledging the frequency and roots of ethical conflicts experienced during STGHEs, sponsors may better prepare visiting trainees and reframe these conflicts as collaborative educational experiences that benefit both the visiting trainee and host providers.

INTRODUCTION

Within the past decade there has been unprecedented growth in global health interest among medical trainees1–3 and an increase in the number of medical students, residents, and fellows traveling to low- and middle-income countries on short-term global health experiences (STGHEs).4,5 To keep up with this growing interest, the number of global health programs offered at U.S. institutions quadrupled between 2003 and 20096,7 and continues to increase within medical residency8 and fellowship1 programs. Availability of global health opportunities serves as a strong recruitment tool with evidence that programs offering global health experiences are preferentially selected by incoming trainees.9,10 STGHEs also have a strong impact on the developing careers of physicians in training. Trainees who complete international rotations report broader medical knowledge,11,12 advanced physical examination skills,8,13 increased cultural sensitivity,9 and enhanced communication skills.8,14 They are more likely to dedicate their clinical career to disadvantaged populations and demonstrate higher rates of humanitarianism.15,16 There have been fewer studies regarding the impact of STGHEs on host institutions, but STGHEs appear to provide broader knowledge and educational resources to the host institution17 and strengthen direct patient care.18

Despite the many benefits, participating in global health experiences can produce ethical challenges that stem from collaborations in which medical practice, cultural norms, and access to resources among partners are dramatically different than what medical trainees from high-income countries are accustomed to.19,20 In this context, ethical conflicts are traditionally defined as witnessing or participating in an encounter that challenges a trainee’s personal or professional moral code. In response to the increasing demand of global health experiences and awareness of potential harms, the American College of Physicians released a position paper on ethical obligations regarding STGHEs,21 converting several previously published practice guidelines for medical students,22–24 residents, and fellows2,19,25,26 into guiding principles for all medical personnel. These recommendations include the need for mandatory predeparture preparation in logistical, cultural, and ethical topics that are tailored to both the international site and institutional collaboration. Despite these recommendations, there has been little guidance regarding which ethics topics should be highlighted in predeparture training.

Annually since 2012, approximately 15 to 20 medical residents and fellows at Emory University School of Medicine from diverse medical specialties have participated in the Global Health Residency Scholars Program (GHRSP). Trainees participate in a yearlong global health curriculum that includes monthly didactics and simulations to build knowledge and practical experience in global health, including several sessions dedicated to global health ethics. The program culminates in a 1-month clinical rotation in Ethiopia, generally at Tikur Anbessa (Black Lion) Hospital, an urban tertiary care hospital in Addis Ababa that serves as the primary teaching hospital for Addis Ababa University (AAU). During these rotations, visiting residents and fellows participate in clinical education, teaching conferences, and patient rounds with direct supervision from Emory and AAU faculty. This is an ongoing collaboration focused at the department level between Emory University School of Medicine and AAU School of Medicine. The GHRSP was set up after discussion with colleagues at AAU to ensure that the program was mutually beneficial for both institutions and that the rotations would enhance and benefit medical education and training within the undergraduate and postgraduate levels at AAU. Each year GHRSP participants write and present a structured reflection essay describing an ethical conflict they encountered during their rotation. We explored ethical conflicts that arose for visiting trainees during the GHRSP rotation and developed a theoretical model grounded in these data. These findings can be used to optimize predeparture curricula, inform expectations for future participants, and strengthen the educational collaboration between visiting and host institutions.

METHODS

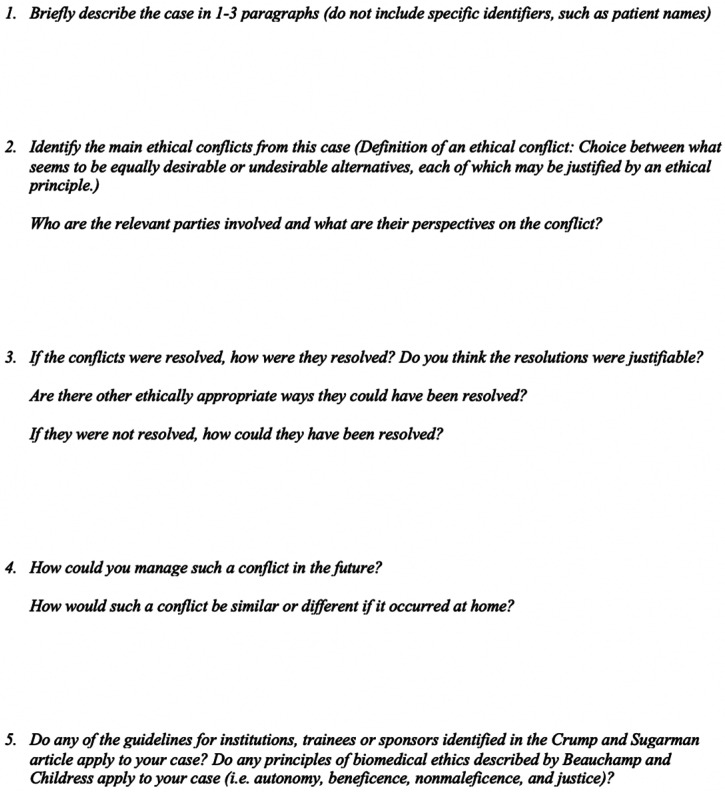

Beginning in 2015, as a part of the GHRSP postrotation debriefing process, Emory residents and fellow participants were requested to complete and present a structured reflection essay about an ethical conflict they encountered during their rotation. The reflection essays included a series of questions requiring the trainees to reflect back on the experience and identify a specific ethical conflict that they encountered, alternative approaches to address the conflict, and resolutions from theirs’ and others’ perspectives. Guidelines provided to residents and fellows on how to complete the reflection exercise are shown in Figure 1. All reflection essays were deidentified before analysis to protect confidentiality, and there was no contact or direct communication with the GHRSP participants during this study. A waiver of informed consent and approval for exemption of human research was granted by the Emory Institutional Review Board.

Figure 1.

Template of the semistructured written response tool used to create the original qualitative data set.

Our approach was a constructivist grounded theory study using semistructured written response tool (Figure 1) completed by most GHRSP participants. The social constructivist approach implies that the theory generated is based on the individual perspectives of the participants27,28 and acknowledges there are diverse interpretations and complex multiple realities of the processes under investigation. The core grounded theory seeks to create a unified explanation for the phenomena described using inductive analysis of the original qualitative data.29 This method was selected over other descriptive forms of qualitative inquiry such as narrative or phenomenological research because it seeks an explanation and provides a framework for further investigation to better inform global health predeparture curricula.

Memo writing was used throughout. Each case was systematically reviewed by two authors (C. E. M. and A. C. V.) using open coding to identify themes and classify preliminary categories. After grouping the categories into a core phenomenon, each case was reviewed again for axial coding to restructure and refine themes and categories. Both open and axial coding were conducted independently by C. E. M. and A. C. V. A sample of the case interpretations was reviewed by Ethiopian colleagues who trained at AAU for further context. Coding schemes were then compared, and consensus was reached30 regarding general themes and categories. Selective coding then explored the intersections and relationship between categories. Finally, themes were combined and compared to generate the central phenomenon and theoretical framework that explains the original data.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics.

Thirty reflection essays were reviewed in the analysis written by residents and fellows between 2015 and 2019. Subspecialities of GHRSP participants included Internal Medicine, Emergency Medicine, Family Medicine, Dermatology, Infectious Diseases, Pathology, Psychiatry, Pediatrics, Pediatric Endocrinology, Radiology, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Ophthalmology, Anesthesia, and Radiation Oncology. Because of the semistructured written response tool used, there were variable levels of length and detail in the responses. All essay authors participated in the predeparture global health curriculum before their rotation in Ethiopia.

Key themes and categories.

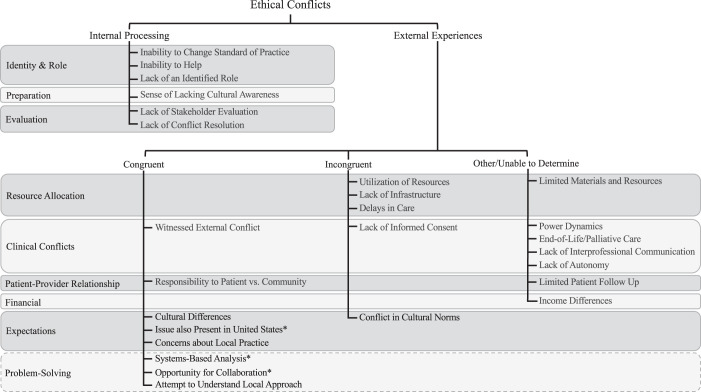

Two major types of ethical conflicts emerged in our analyses of trainee essays: internal conflicts versus external conflicts. The source of the conflict was either related to the presence of the visiting medical trainee and their interactions with the environment (internal processing) or from witnessed experiences external to the trainee. Themes within external experiences were further characterized by the degree of congruence the trainee interpreted as sharing with, or diverging from, the perspective of Ethiopian providers. The summary of the categories and subcategories identified is depicted in Figure 2 and defined in Tables 1 and 2.

Figure 2.

Summary of the axial coding paradigm developed from the reflective essays of Global Health Residency Scholars Program (GHRSP) participants by grouping categories into internal or external processes. Further subgroup categorizations that span different core categories are also depicted. *Denotes a category that is not of ethical conflict but describes the downstream effect of experiencing a conflict and constructing a framework to explore potential solutions.

Table 1.

Internal processing categories generated by open and axial coding with definitions of category labels and examples from the reflective essays

| Core category | Subcategories | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Processing | Inability to Change Standard of Care | Frustration or acknowledgment that similar scenarios have occurred previously and change to prevent reoccurrence has not taken place. | “The hematology department does recognize that there is a problem with neutropenic fever prevention and treatment in the hospital system. This however does not deter any treatment which may result in severe neutropenia.” |

| Inability to Help | Sense of being unable to influence patient outcomes. | “Nobody knew where I was from, what my background was, what my level of training was, and thus I felt it was unprofessional of me to try and intervene.” “I think there will always be an internal tension for radiology residents … between the patient care environment that they have been trained in, and the practical realities of Ethiopian healthcare, between what they hope to do, and what they can do.” | |

| Lack of Conflict Resolution | Visiting resident perceived that there was no resolution to the conflict they witnessed or experienced. | “Ultimately, there was no conflict resolution. … The child did die, but the questions of the boundaries of our role while working in [Ethiopia], and the question of what more we can offer remain open.” “It is unsure if a resolution for this scenario was achieved. This was a unique scenario and unforeseen consequence of our pilot study.” | |

| Lack of Identifiable Role | Lack of understanding or expectation about role of visiting trainee. | “When I discussed this with the resident, the procedure had already been completed and I did not feel that it was appropriate for me to question what they had done—to have started a discussion about informed consent at the time would have, I believe, seemed accusatory.” “As a visitor, it is difficult to insert myself into the hierarchy of a surgical training program. Although I would have liked to moderate a discussion with the attending and the resident at the least, and possibly with the family, there are established roles and procedures.” | |

| Lack of Stakeholder Evaluation | No attempt or perceived inability of visiting trainee to assess various stakeholder input. | “Unfortunately, due to…inability to discuss critical matters like this with the Ethiopian attendings, it is unclear their perspective on the matter.” “It was difficult to ascertain what was most needed or would be most beneficial for the residents in Addis before my arrival there.” | |

| Sense of Lacking Cultural Awareness | Internal reflection of the visiting trainee acknowledging a deficiency in their awareness of local cultural or community practices. | “The concept of cultural competency would apply as this circumstance could have possibly been avoided with a better understanding of cultural standards of Ethiopian citizens in general, as well as those within the medical community.” “I could have provided my thoughts on how this would be managed in the USA at my home institution, however given the immense challenge the surgical program has with resources—OR time, plates and screws, reliable pathologic reports—there would be some disconnect with evaluating the situation and system as a whole.” |

Table 2.

External experience categories generated by open and axial coding with definitions of category labels and examples from the reflective essays

| Core categories | Categories | Subcategories | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| External Experience | Congruent | Attempt to Understand Local Approach* | Visiting trainee attempted to understand the Ethiopian perspective by discussing the case or conflict with a local provider. | “I was only able to discuss this with the residents, but their perspective was one that they had tried many other systems, none of them worked very well, and this was their current attempt at making the best of what they had.” “During the process, a couple of residents explained that is seemed somewhat strange to be using this delicacy (thick cuts of high-quality steak) for a [procedure] simulation, especially since it would be discarded once we finished the simulation.” |

| Concern about Local Practice | Medical care witnessed is viewed as substandard by both visiting and local providers. | “I witnessed a critically ill patient receiving poor medical care. … The Ethiopian residents were managing the patient as well as they knew how. They clearly were overwhelmed and my impression was that they did not receive much training on how to manage situations like this.” “A prior biopsy read … was clearly not the correct diagnosis. The team did not have access to necessary reconstruction hardware including plates and screws. They acknowledged that the standard of care would have been resection, however in light of their limitations, they elected to perform a [different procedure].” | ||

| Cultural Differences | A perceived difference in approach to patient care between U.S. and Ethiopian training but with the same anticipated outcome. | “The culture in the United States to weigh the risks and benefits of treatment and sometimes withholding chemotherapy for the benefit of the patient may not be as well accepted in Ethiopia. When deciding to withhold treatment from a patient, the patient and his/her family should also be involved in the decision, but this is not the case based on patient interactions we observed.” | ||

| Issue Also Present in United States | The conflict details or themes are acknowledged to be an issue within the visiting trainees home institution. | “In the setting of poor prognosis for a progressive disease, it benefits both the clinician and the patient/family to discuss their wishes prior to an emergent event. This could prevent a similar conflict, but this is difficult to do in the U.S. let alone in a resource-limited setting. I do not think this was an ethical dilemma unique to Ethiopia.” “Thankfully there are enough resources in the U.S. that there wouldn’t be that kind of waiting list to be treated, however we do have similar problems with VIPs or people with a lot of money getting preferential treatment.” | ||

| Opportunity for Collaboration* | Acknowledged as an opportunity for teaching or learning between visiting and local trainees/providers. | “I think in the future I would engage in a more detailed discussion of how Ethiopian physicians approach informed consent. … I would ask the residents more about the consent process and what their typical discussion is with a patient.” “One of our teaching [topics] was requested by the Ethiopian faculty and became a collaboration. … The faculty and hospital have a huge need in their patient population for Palliative Care and identified our program as a way to help with establishing that mentoring and teaching.” | ||

| Responsibility to Patient vs. Community | Direct conflict between a provider’s responsibility toward an individual patient and their responsibility to the community. | “Our main conflict is that we will have to choose between operating in a limited resource setting despite knowing that we will have complications and poor follow up vs. choosing to not intervene at all.” “It was a child born with multiple birth defects who would need advanced surgical and medical interventions and there was a delay in diagnosis due to use of [an imaging] modality which was not standard. It was also unclear whether they could offer the interventions the child would need, and so that posed the question, is there a way to get this child to a center which could? Would that be the right thing to do? Why would we offer that to this child and not everyone?” | ||

| Systems-Based Analysis* | Conflict prompted a review of how this conflict could be improved at a system-wide level. | “The resolutions are justifiable on a case-by-case basis, but do not remedy the deeper systems problems. … An attempt at resolution would require changes from the top down: hospital funding, laboratory capacity, pharmacy dispensing, as well as clinical reasoning.” “In the current system, there is no systematic process to re-evaluate current MICU patients’ status and de-escalate care quickly in the situation where a bed is urgently needed [for a sick patient].” | ||

| Witnessed External Conflict | Perception of that Ethiopian providers experienced similar distress at the outcome of a case. | “Although the faculty and staff held the perspective that the patient should be made comfortable and ultimately aggressive care removed in a timely manner, the influence of the hospital administration prohibited them from caring out what was ethically the most appropriate for the patient.” “The residents feel unsupported and not well equipped to make good management decisions. As a result, they often make minimal changes to the management plans.” | ||

| Other/Unable to Determine | Lack of Autonomy | Lack or patient or family autonomy in medical decision-making. | “The patient was not involved in any of the decision making as she was not even present during the visit. Her family had traveled 200km and there was no way for them to transport this elderly woman that long of a distance safely.” “Patients’ autonomy was frequently usurped in Ethiopia. Perhaps due to cultural norms, the expected doctor’s role, or provider preference, many patients were given limited autonomy in their own medical care.” | |

| End-of-Life/Palliative Care | Conflict involving issues around palliative or end-of-life care. | “[CPR] prolonged the child’s life by a few days. He was intubated and sedated for the remainder of his time. … As a clinician, I believe that the resolution was justifiable in an emergent situation. However, I do wish that the situation could have been prevented to begin with.” “Because of the acute and urgent situation, the medical team did not have explain to the father what they were doing, and they certainly did not discuss the father’s wishes regarding code status or for the patient’s end of life care… Unfortunately, this is a common occurrence in Ethiopia as Palliative Care is a developing field in both adult and pediatric care. I witnessed very few discussions regarding end-of-life care or code status despite seeing many critical patients.” | ||

| Income Differences | Acknowledgment of income status difference between visiting trainee and their Ethiopian colleagues and patients. | “Radiology is by its very nature a very expensive and technology-dependent field, certainly among the most so of any of the medical specialties. This makes a stark contrast between the United States and its near-decadent approach to healthcare and any developing nation.” “The hospital has no thrombolytics available. A private hospital down the road does. The initial cost is quoted at 3000 ETB or ∼100 USD—a cost that does not initially seem prohibitive. [The patient’s] family explains that they are unable to afford it. Between your [American] team you easily have that amount in cash. What do you do?” | ||

| Lack of Communication | Ineffective or lack of communication between interprofessional stakeholders and medical team members. | “There was little discussion (among the treatment team, and also with the patient/family) regarding risks/benefits of chemotherapy prior to initiation, at least per our observation.” “The ethical conflict could have been resolved if there was a system in place to allow for urgent communication for acute findings such as paging or telephone. Having the ability to contact different services or attendings directly could provide a streamlined system allowing for prompt medical care.” | ||

| Limited Materials and Resources | Lack of access or materials or resources considered by the visiting trainee to be within the standard of care. | “The resident started bagging the patient but there was no oxygen tank available – someone had to go get it … there are no blood pressure measurements because the patient does not have a blood pressure cuff…ICU attending mentions using fiberoptic to confirm placement, but fiberoptic was just used on another patient and is dirty.” “Our first day in the operating room we quickly learned that we would have limited access to their cystoscopy equipment. Upon realizing this, we discussed with the consultants and residents how this will limit our work in certain compartments of the pelvic floor. We explained that in the spirit of “do no harm,” we cannot perform surgeries where we are unable to properly detect iatrogenic injuries, especially if they can lead to chronic infection and organ failure later on.” | ||

| Limited Patient Follow-Up | Lack of patient follow up within the clinical setting. | “This patient was sent home relatively quickly after minimal examination; both patient numbers and distance travelled make it impossible to personally follow patients beyond the post-operative day one visit.” “Many times, in Ethiopia, due to the great distance in being able to receive treatment, family members will come to pick up medications for their loved one and the doctor has not seen the patient for months.” | ||

| Power Dynamics | Decision inequities within a medical team related to interpersonal dynamics. | “I did not want to be paternalistic and jump in when the Ethiopian residents’ management of the patient was inadequate, especially because there was an [American] ICU attending supervising and not correcting them.” “We let the Ethiopian attending lead the surgery and watched the surgeon leave small bits of tumor attached to the underlying mucosa. In our attempt to remove this excess tumor made the attending very uncomfortable and almost defiant that he did not want us to remove any further tissue.” | ||

| Incongruent | Conflict in Cultural Norms | Differences in what is considered an acceptable or anticipated outcome between visiting and local providers. | “Once he did develop neutropenic fever, he was not able to receive the hospital’s standard of care with regard to antibiotics since he couldn’t afford it. Such a massive change will require a change in provider attitudes. There may be some cultural differences that may be difficult to change.” “In the US if this complication were to happen, we would do daily checks on the patient’s eye and pressure and follow up very closely. [In Ethiopia] this patient was sent home relatively quickly after minimal examination.” | |

| Delay in Care | Delay in medical care correlated with adverse patient outcome. | “No electronic medical record and radiology reports are typed on Microsoft Word with significant delay in turn-around time.” “Neurosurgery had not seen the patient by morning report and were called again and asked to see the patient. During the course of the day the patient’s right sided weakness became full paralysis and he had multiple episodes of grand mal seizures. The next day neurosurgery still had not seen the patient.” | ||

| Lack of Informed Consent | Perception of visiting trainee that informed consent was not obtained. | “We discussed informing the patient and allowing her to decide, but the language and practice barriers limited our ability to ensure that this would be done correctly.” | ||

| Lack of Infrastructure | Effectiveness of available or recommended resources is undermined by a lack of institutional or societal support. | “The fundamental question was: can we justify offering a potential lethal treatment of myeloablative chemotherapy for an also lethal condition (leukemia) if we cannot also offer adequate supportive care?” “This conflict involves the triage process and the motivations for accepting patients to the MICU. … The scenario described is more of a system malfunction.” | ||

| Utilization of Resources | Inappropriate or ineffective use of resources that are available. | “We realized that the residents were not screening the patients for diabetes complications and comorbidities even though the resources were readily available.” “She then explained that this patient had lung cancer, had a poor long-term prognosis, and should not have been intubated. The ED only has two ventilators and by intubating this woman who had likely chronic respiratory failure, you wouldn’t be able to use the ventilator for another patient.” |

Denotes a category that is not of ethical conflict but describes the downstream effect of experiencing a conflict and constructing a framework to explore potential solutions.

Internal processing.

Many of the ethical conflicts described in the essays reflected concerns about the presence of the visiting trainee within Ethiopia and the impact their visiting status had on their personal development and the surrounding environment. Themes included the following: identity (inability to change standard practice, inability to help, lack of an identifiable role), preparation (sense of lacking cultural awareness), and evaluation (lack of stakeholder evaluation, lack of conflict resolution). Issues related to identity expressed concerns about the role of visiting trainees during the rotation including powerlessness in improving current medical practice or inability to have a positive impact on clinical outcomes. One trainee commented:

We hope to make a small improvement in healthcare … but we cannot really make significant interventions for individual patients or bridge the divide between the standard of care in which we received our training and what is available to the population of [Ethiopia].

Additionally, several trainees discussed the lack of having a defined role during the rotation and that the experience would have benefited from clearer expectations before the trainee’s arrival. They recognized deficits in their own cultural awareness and interpreted these as shortfalls in their understanding or preparation for the rotation. One trainee remarked on the lack of cultural awareness in an Ethiopian context and the isolating effect it had on her from her surroundings. She describes the moment she acknowledged that her understanding of “futile care” was much different from the definition generally accepted by local providers.

The disparity that became clear to me in this case was my unawareness of what constituted urgent care and futile care in this healthcare setting, which was already familiar and internalized with the people who work there every day.

It was rare for any of the ethical conflicts discussed within the essays to be resolved. Although many trainees attributed this lack of resolution to faults within the medical system, there were instances in which the absence of resolution was internalized as a personal limitation of the visiting trainee. This was usually due to lack of fully understanding the context of the conflict, lack of decision-making control, or inability to engage Ethiopian providers in a stakeholder evaluation.

External experiences.

The remainder of ethical conflicts were scenarios external to the visiting trainee and described as part of the training and clinical environment within Ethiopia. For example, witnessing the treatment of a patient’s infection be dictated by which antibiotics the patient could or could not afford. These experiences were further stratified by the visiting trainee’s perception of congruence with Ethiopian providers. In many instances the interpretation of a scenario as an ethical conflict was shared by both the visiting trainee and the Ethiopian providers involved, whereas at other times, the conflict stemmed from the fact that a scenario viewed as a conflict by the trainee was not seen as such by their Ethiopian colleagues. A third theme was also identified for experiences in which congruence was not specifically commented on or was unknown in the context of the situation described.

Congruent external experiences.

Themes among external ethical conflicts considered congruent between visiting trainees and Ethiopian providers included clinical conflicts (witnessed external conflict), issues around the patient–provider relationship (responsibility to patient vs. community), and expectations of clinical outcomes (cultural differences, issues also present in the United States, concerns about local practice). Although not a specific type of ethical conflict, the category of conflict processing (systems-based analysis, opportunity for collaboration, attempt to understand local approach) emerged as a unique result of trainee processing of a witnessed conflict.

Visiting trainees reported instances in which they observed Ethiopian providers experience or discuss ethical conflicts they have faced. Similarly, some trainees along with their Ethiopian clinical team were challenged by a conflicting responsibility to a single patient versus the community as a whole. One trainee described a case of a young woman with a pulmonary embolus and the debate of whether to place her on the last available mechanical ventilator despite her poor prognosis:

We were conflicted between the natural moral imperative we felt to help the human in front of us and the realization that doing so would potentially create an environment that was unfair and favored an individual’s health over that of the system/population.

The final theme within congruent external experiences included shared expectations of clinical outcomes between the visiting trainee and Ethiopian providers and distress that resulted when those outcomes were not met. This included an appreciation of different approaches to clinical care between the visiting trainee’s expectation and realistic practice in Ethiopia provided the outcome was still acceptable. One trainee commented on this:

What we perceive as “urgent” does not necessarily translate, figuratively speaking, to the care. This may be because we’re unaware of the resource availability, and thus the systemic triage, that often happens below our perception.

Alternatively, trainees also related to some ethical conflicts they witnessed by comparing how the scenario would play out similarly in the United States or at their home institution, normalizing the ethical conflict as a universal issue. For the conflicts that were related to substandard clinical practice, the trainee often described when this concern was shared by Ethiopian providers as well.

Conflict processing included categories that engaged the visiting trainee and local providers in recognizing causes of the ethical conflict and potential solutions together. This category is distinctly separate from others in that it does not fall under “ethical conflicts” per se. However, it does capture the phenomenon of trainees translating witnessed conflicts—for example, allocation of material resources, issues regarding informed consent, or expectations for clinical outcomes—into potential solutions. Often the Emory trainee would describe a multidisciplinary approach that identified one or several areas of the healthcare system where change would help prevent similar scenarios from occurring in the future. Trainees also identified some of these ethical conflicts as opportunities to collaborate with local providers or prompt conversations to try to fully understand the conflict from an Ethiopian provider’s perspective. One reflection essay recounted the experience:

I asked the [Ethiopian] residents about whether they typically discuss code status with the patient’s family—and they did not know what I was talking about. I learned from them that the culture in Ethiopia seems to imply full code status for every patient.

Incongruent external experiences.

This category includes external ethical conflicts where the conflict experienced by visiting trainee does not seem to be viewed as ethically significant by Ethiopian providers. This was most often depicted in the cases as Ethiopian providers describing the context of the case to the visiting trainee with normalizing or standardizing language. The themes of these conflicts include resource allocation (utilization of resources, lack of infrastructure, delays in care), clinical conflicts (informed consent), and expectations of clinical outcomes (conflict in cultural norms).

Allocation of resources was frequently reported by visiting trainees as inefficient use of existing clinical resources. This included concerns about the use of material resources (diabetes supplies and pathology cassettes were cited as examples), delays in providing patient care, and the lack of infrastructure to support adequate clinical care. One trainee posed the following question after seeing a patient suffer complications from chemotherapy:

Should the patient have been given systemic chemotherapy knowing the risk of developing neutropenia with subsequent infection, if the healthcare system is then not going to support the patient in treating this life-threatening infection?

Several visiting trainees remarked on issues where cultural differences in approach to care between themselves and Ethiopian providers resulted in opposing expectations about acceptable outcomes. This often challenged the visiting trainee’s expectations that had been originally formed by his or her training in the United States. In particular, issues regarding informed consent were often discussed. One resident expressed concern when a procedure she felt was unnecessary for clinical diagnosis was done:

I am not sure if [the resident] explained to the patient that the only motivation for doing the biopsy was for education rather than diagnosis. [The resident] may have done so … I suspect [the patient] may not have agreed to the procedure for purely learning purposes.

Other external experiences.

There were external conflict themes that did not clearly fall within congruent or incongruent themes due to lack of information or description provided in the written essay. For example, resource allocation (limited materials and resources), clinical conflicts (power dynamics, end-of-life/palliative care, lack of interprofessional communication, lack of autonomy), issues around the patient–provider relationship (limited patient follow-up), and financial considerations (income differences) were not easily categorized.

The most frequently cited category for ethical conflicts revolved around limited material resources. These were most often framed as a comparison of how the scenario would be handled using resources readily available at the trainee’s home institution in the United States compared with how it was addressed in Ethiopia.

The most striking difference is the resources available, and the impact they make on care. First, prenatal care and the impact of screening ultrasound, but also the availability of advanced imaging, including fetal MRI and echocardiography. Often difficult cardiac cases in the U.S. are now identified prenatally. Availability of advanced cardiac and specialized general pediatric surgeons, and the transportation to get the children to the appropriate specialist center are important contrasts as well.

Conflicts were also witnessed in direct patient care and interprofessional interactions. Visiting trainees commented on ethical issues regarding power dynamics and poor communication within the medical team. There were also several cases that discussed the lack of palliative care services available or observed minimal autonomy offered to the patient to engage in their medical care.

The patient and his family were assumed not to understand the diagnosis and the associated treatments. It was hard for me to tell if the family was consulted or if they understood that there would be more surgeries involved.

Other external ethical conflicts included limited patient follow-up and an awareness of the financial inequalities between the visiting trainee and the Ethiopian providers and patients.

DISCUSSION

This study is among the first to identify a framework and associated themes about ethical conflicts experienced by visiting American medical residents and fellows during STGHEs in Ethiopia based on a qualitative analysis of semistructured written reflection essays. Ethical conflicts are categorized as related to either an internal process or the external environment relative to the visiting trainee’s experience. Conflicts related to the external environment are further stratified by the degree to which the interpretation of the conflict is shared with the trainee’s international hosts.

Ethical conflicts during a STGHE can have a profound effect on the trainee’s experience. Positive outcomes include viewing the conflict as a transformational experience31 that causes the trainee to reevaluate their assumptions, change their understanding of the world around them, and broaden their range of moral reasoning. Opposingly, ethical conflicts can lead to moral distress, defined as discomfort or awareness that occurs when a provider acts in a manner contrary to personal or professional values due to the influence or limitations within the external environment.32 Adverse outcomes of moral distress include stress, anxiety, loss of compassion, and personal psychological fatigue.33 STGHE participants are particularly vulnerable to moral distress because they are surrounded by a community in which practice patterns, resources, language, and culture are dramatically different from their home training environment.

There is a paucity of research exploring host perspectives of STGHEs and few investigations we are aware of that explore the impact of STGHE-related ethical conflicts on host providers or the academic partnership. Benefits of STGHEs as described by host preceptors include improvement in specialty training, a sense of achievement in providing teaching to the next generation of providers,17 and promotion of the professional image of the clinical location.18 These come at the cost of decreased efficiency for the host preceptors.17,18 A survey of Ugandan residents found that nearly a third of participants reported discomfort with the ethics of certain clinical decisions made by visiting faculty,34 although the same number also shared similar concerns regarding local faculty as well. Lukolyo et al. also described gaps identified by host preceptors within visiting trainee’s knowledge base regarding health system infrastructure. They conclude that host preceptors prefer trainees to complete a targeted predeparture curriculum including training in ethical and emotional challenges they may encounter abroad.18

Within our analysis, ethical conflicts originating from internal processing included challenges related to the visiting trainee’s presence in the international site, calling into question their sense of self or professional identity. This phenomenon has been described previously as related to the concepts of introspection, humility, and solidarity35 that are essential for moral development and reasoning.36 The role of self-compassion and mindfulness in global health remains largely unexplored,37 but brief mindfulness interventions38 and mindful emotional awareness39 have been shown to reduce stress and emotional exhaustion while improving resilience among physicians. Teaching these skills and applying these principles to anticipated challenges during a global health rotation may preemptively combat distress associated with internal processes. We found that visiting trainees also rarely elicited feedback or perspectives of the case from their Ethiopian colleagues, experienced resolution, or debriefed about the ethical conflict before the end of the rotation. When used in the appropriate setting, these practices can assist with understanding the root causes of a scenario, offsetting the emotional or moral distress experienced and reframing it as more of a transformative learning experience.

Many recommendations for STGHEs include the need for clear role identification and expectations for visiting trainees.2,5,21,23,25 This includes an outline for clinical duties, teaching responsibilities, the degree of supervision required based on level of training, and any limitations within normal scope of practice due to their visiting status. These should be established before their arrival for the rotation and revised based on feedback from previous rotation participants and providers from the host institution. Having a more clearly defined role agreed upon by both sponsoring and host institutions and an identified in-country mentor or peer would likely prevent some of the distress experienced by STGHE participants. Within the GHRSP, this includes a preestablished Memorandum of Understanding between Emory and AAU that specifies an annual predeparture evaluation of training needs and education priorities at AAU before a visiting trainee’s departure. This is an essential part of the collaboration to ensure ongoing mutual benefit from the program.

Previous concerns of STGHEs related to the presence of visiting trainees were not seen within our analysis. Recommendations often raise concern about the burden of visiting trainees on local providers and the diversion of already limited resources to meet the needs of visiting trainees;9,40 however, this was not commented on by any GHRSP participants. This may be related to the fact that Ethiopian colleagues have not been queried about this issue directly. Alternatively, variable amounts of support are also provided by the high-income institution within academic partnerships. For the GHRSP, all expenses (salary, airfare, hotel and living expenses) for visiting trainees and supervising faculty are covered by the GHRSP through support from the trainee or faculty’s department and the Dean’s Office in the Emory University School of Medicine. There are also frequently cited concerns within the medical literature about exceeding a visiting trainee’s scope of practice,41–43 which was not voiced in any trainee reflection for this analysis. One potential explanation for this is that these issues may be more specific for individuals who are earlier in their training, such as medical students,44,45 who have a larger representation in the literature on STGHEs than residents and fellows.9 Alternatively, visiting Emory trainees may have lacked awareness of this concern early in their learning about the culture and context of medical practice in Ethiopia.

External ethical conflicts related to the visiting trainee’s environment were most often caused by a difference in expectations generated from medical training within a high-income setting versus actual outcomes in Ethiopia. The levels of distress experienced during the scenario may be correlated with the level of divergence from expectations and congruence/incongruence with local providers. Issues that were similar to those experienced in the United States or congruent with local providers were familiar to the visiting trainee. These types of conflicts were more often identified as opportunities for collaboration or for engagement in systems-based analyses.

In contrast, incongruent and other external conflicts were more difficult for the visiting trainee to reconcile without an understanding of local practice approaches and customs. This is one of the suggestions made by Melby et al.2 as a guiding principle of STGHE development to build cross-cultural effectiveness and humility. These types of ethical conflicts raise the question of what a visiting trainee’s practice standards should be in resource-limited settings. Adhering to expectations that are not congruent with local providers can represent a form of ethical imperialism and serves as an important reminder that resolution of ethical conflicts must be sought within culturally and structurally appropriate contexts. An example of this includes delays in triage and subspecialty care, which several GHRSP participants commented would be considered unacceptable within the United States. As discussed by Iserson et al.,46 creating triage criteria in emergency care—if accepted by the local provider and patient communities—can resolve this issue because it is based on culturally acceptable limits and maximizing use of the limited resources available. These authors made the argument for framing these issues as “moral challenges” rather than “ethical conflict” because the standard of care is different between resource-rich and resource-poor areas and the resulting goals and values cannot be directly compared.46

The distinction between moral versus emotional distress can also be difficult for medical trainees to identify. Many of the scenarios described by trainees in our analysis referenced emotionally distressing clinical emergencies, including cardiac arrest, respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation, cancer diagnosis, and end-of-life care. The frequency with which these types of scenarios were described raises questions about how commonly the label of “ethical conflict” is applied to cases that are emotionally challenging but ethically straightforward. In our case series, the application of a structured written response tool assisted participants in selecting cases with ethics-specific concerns to answer the prompts. However, this suggests there is benefit to providing education on the distinction among ethical conflicts, moral distress, and emotional distress47 within predeparture curricula to facilitate recognition of the wide array of clinical scenarios an ethical conflict does, or does not, encompass.

Specific and reoccurring incongruent external conflicts suggest case examples and themes for a global health predeparture curriculum to address that is tailored to the specific realities faced in that particular host country by trainees from that originating institution. Within the Emory–AAU partnership, this would include cases involving informed consent, interprofessional communication, power dynamics, limited material resources, and approaches to end-of-life and palliative care in Ethiopia. For example, several GHRSP participants commented on lack of patient autonomy and engaging the patient in shared decision-making, both principles fundamental to medicine in the United States that are less pervasive in other parts of the world. A predeparture case-based simulation could address this idea supported by evidence that different community groups favor a family-centered, rather than patient-centered, model of medical decision-making48 and Ethiopian refugees in the United States prefer a diagnosis of terminal illness to be disclosed to family or close friend, viewing this as more appropriate than telling the patient directly.49

The results of this study have important implications enhancing predeparture preparation curricula. Teaching trainees the differing types of ethical conflicts they may experience can help them recognize the issue and select which set of tools are best used to address it. Ethical conflicts around internal processes would be better served if the trainee was taught about self-compassion and mindfulness. Congruent external conflicts can draw on skills learned from ethical conflicts experienced at their home institution, while incongruent external conflicts may require training in systems analysis and stakeholder evaluation to fully understand appropriate clinical and cultural context. This is the first study to our knowledge that categorizes the types of ethical conflicts experienced by visiting trainees and provides a framework for addressing them that can be adapted into a preexisting global health predeparture curriculum.

Case-based learning is a cornerstone educational tool in current global health ethics pre-departure curricula used to introduce potential conflicts and themes with the ability to immediately process, share opinions, and debrief with other trainees. Cases can take the form of written prompts such as the online syllabus created in collaboration by Stanford and Johns Hopkins Universities50 (http://ethicsandglobalhealth.org) or the Simulation for Global Away Rotations (SUGAR) curriculum, which uses written prompts and trained facilitators to teach trainees processing skills that transform ethical conflicts from distressing experiences into learning opportunities. Both of these case-based ethics curricula were adapted for use within GHRSP prior to the trainees’ rotation in Ethiopia. A more immersive approach is taken by the ESIGHT program51 and the Health, Equity, Action and Leadership (HEAL) Initiative at the University of California–San Francisco,52 which use in-person simulated experiences with actors to re-create ethical conflicts and reframe reactions into adaptive approaches. In particular for cases involving incongruent external conflicts, case-based simulation via written prompts or acted scenes followed by debriefing, theme analysis, and self-reflection may serve as an invaluable educational tool specific to each sponsoring and host program collaboration.

Distinguishing differences between internal versus external conflicts aligns with the findings of Harrison et al.,53 who conducted focus groups comprising of global health faculty on ethical dilemmas that medical trainees could potentially encounter. Themes that overlapped with our analysis included interactions with the external environment and a category for “personal moral development” similar to our finding of internal processing but encompassing a wider catchment of moral and personal beliefs belonging to the visiting trainee. Our sample differs in that it directly assesses conflicts experienced by medical trainees rather than concerns raised by faculty with global health experience. However, the overlap in themes and categories suggests there are some shared classifications worth addressing in all predeparture curricula.

Limitations of our study include that it encompasses the experience of one STGHE program and results should be applied with caution to other partnerships and international sites. The utilization of a static written response tool for qualitative analysis also limits the application of grounded theory, and there was no way to confirm or assess category saturation or revisit specific cases for further detail. The small sample size of 30 written prompts similarly lacks the power to summarize all of the themes applicable to ethical conflicts experienced in the Emory–AAU partnership. Perhaps the most relevant omission is the absence of input from Ethiopian providers and that the determination of congruence and incongruence is based on the interpretation and language used by the visiting trainee within the reflective essay. Although research on ethical considerations of STGHEs is lacking, there is even less literature about the impact on host communities and institutions54–56 highlighting the need for bidirectionality in future investigations. Research on this issue within the GHRSP includes an upcoming interview-based study with Ethiopian providers to discuss these cases and elicit novel considerations from the Ethiopian perspective with the overall goal of tailoring the program to better promote the agenda of local host communities.

We developed a grounded theory about ethical conflicts experienced by visiting medical trainees during an international health rotation using a constant comparative methodology applied to a diverse range of clinical experiences with a singular institutional partnership. Although some themes and structures may be unique to the GHRSP, the overall approach can be applied and adapted to similar academic collaborations. The identification of themes stratified by internal versus external processing and congruence with local providers helps inform optimal methods for anticipating these issues within predeparture curricula and preparing medical trainees for the challenges associated with participating in STGHEs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the participants and leadership of the Global Health Residency Scholars Program and Emory Division of Internal Medicine Global Health Distinctions Program. We also thank Dr. Anteneh Eshetu from the Addis Ababa University Department of Internal Medicine and Dr. Kassahun Desalegn from the Emory Department of Dermatology for their feedback on the cases and manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Nelson B Izadnegahdar R Hall L Lee PT , 2012. Global health fellowships: a national, cross-disciplinary survey of US training opportunities. J Grad Med Educ 4: 184–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Melby MK Loh LC Evert J Prater C Lin H Khan OA , 2016. Beyond medical “missions” to impact-driven short-term experiences in global health (STEGHs): ethical principles to optimize community benefit and learner experience. Acad Med 91: 633–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Association of American Medical Colleges , 2012. Matriculating Student Questionnaire: 2012 All Schools Summary Report. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/students-residents/report/matriculating-student-questionnaire-msq.

- 4. Kerry VB Ndung’u T Walensky RP Lee PT Kayanja VF Bangsberg DR , 2011. Managing the demand for global health education. PLoS Med 8: e1001118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Drain PK Holmes KK Skeff KM Hall TL Gardner P , 2009. Global health training and international clinical rotations during residency: current status, needs, and opportunities. Acad Med 84: 320–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Merson MH Page C , 2009. The Dramatic Expansion of University Engagement in Global Health: Implications for US Policy: A Report by the CSIS Global Health Policy Center. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies.

- 7. Macfarlane SB Jacobs M Kaaya EE , 2008. In the name of global health: trends in academic institutions. J Public Health Policy 29: 383–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lu PM Park EE Rabin TL Schwartz JI Shearer LS Siegler EL Peck RN , 2018. Impact of global health electives on US medical residents: a systematic review. Ann Glob Health 84: 692–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mutchnick IS Moyer CA Stern DT , 2003. Expanding the boundaries of medical education: evidence for cross-cultural exchanges. Acad Med 78: S1–S5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Miller WC Corey GR Lallinger GJ Durack DT , 1995. International health and internal medicine residency training: the Duke University experience. Am J Med 99: 291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Monroe-Wise A Kibore M Kiarie J Nduati R Mburu J Drake FT Bremner W Holmes K Farquhar C , 2014. The Clinical Education Partnership Initiative: an innovative approach to global health education. BMC Med Educ 14: 1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sawatsky AP Rosenman DJ Merry SP McDonald FS , 2010. Eight years of the Mayo International Health Program: what an international elective adds to resident education. Mayo Clin Proc 85: 734–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Smilkstein G Culjat D , 1990. An international health fellowship in primary care in the developing world. Acad Med 65: 781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Haq C Rothenberg D Gjerde C Bobula J Wilson C Bickley L Cardelle A Joseph A , 2000. New world views: preparing physicians in training for global health work. Fam Med 32: 566–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thompson MJ Huntington MK Hunt DD Pinsky LE Brodie JJ , 2003. Educational effects of international health electives on U.S. and Canadian medical students and residents: a literature review. Acad Med 78: 342–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Drain PK Primack A Hunt DD Fawzi WW Holmes KK Gardner P , 2007. Global health in medical education: a call for more training and opportunities. Acad Med 82: 226–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Keating EM Haq H Rees CA Swamy P Turner TL Marton S Sanders J Mohapi EQ Kazembe PN Schutze GE , 2019. Reciprocity? International preceptors’ perceptions of global health elective learners at African sites. Ann Glob Health 85: 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lukolyo H Rees CA Keating EM Swamy P Schutze GE Marton S Turner TL , 2016. Perceptions and expectations of host country preceptors of short-term learners at four clinical sites in sub-Saharan Africa. Acad Pediatr 16: 387–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stone GS Olson KR , 2016. The ethics of medical volunteerism. Med Clin North Am 100: 237–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wall A , 2011. The context of ethical problems in medical volunteer work. HEC Forum 23: 79–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. DeCamp M Lehmann LS Jaeel P Horwitch C , 2018. Ethical obligations regarding short-term global health clinical experiences: an American College of Physicians position paper. Ann Intern Med 168: 651–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shah S Wu T , 2008. The medical student global health experience: professionalism and ethical implications. J Med Ethics 34: 375–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lahey T , 2012. Perspective: a proposed medical school curriculum to help students recognize and resolve ethical issues of global health outreach work. Acad Med 87: 210–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Raine SP , 2017. Ethical issues in education: medical trainees and the global health experience. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 43: 115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Crump JA Sugarman J Working Group on Ethics Guidelines for Global Health T , 2010. Ethics and best practice guidelines for training experiences in global health. Am J Trop Med Hyg 83: 1178–1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Suchdev P Ahrens K Click E Macklin L Evangelista D Graham E , 2007. A model for sustainable short-term international medical trips. Ambul Pediatr 7: 317–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mills J Bonner A Francis K , 2006. The development of constructivist grounded theory. Int J Qual Methods 5: 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Charmaz K , 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- 29. Corbin J Strauss A , 2014. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- 30. Denzin NK Lincoln YS , 2008. Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- 31. Mezirow J , 2003. Transformative learning as discourse. J Transform Educ 1: 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Campbell SM Ulrich CM Grady C , 2016. A broader understanding of moral distress. Am J Bioeth 16: 2–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Epstein EG Hamric AB , 2009. Moral distress, moral residue, and the crescendo effect. J Clin Ethics 20: 330–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Elobu AE Kintu A Galukande M Kaggwa S Mijjumbi C Tindimwebwa J Roche A Dubowitz G Ozgediz D Lipnick M , 2014. Evaluating international global health collaborations: perspectives from surgery and anesthesia trainees in Uganda. Surgery 155: 585–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pinto AD Upshur RE , 2009. Global health ethics for students. Developing World Bioeth 9: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. DeCamp M Kalbarczyk A Manabe YC Sewankambo NK , 2019. A new vision for bioethics training in global health. Lancet Glob Health 7: e1002–e1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hall-Clifford R Addiss DG Cook-Deegan R Lavery JV , 2019. Global health fieldwork ethics: mapping the challenges. Health Hum Rights 21: 1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schroeder DA Stephens E Colgan D Hunsinger M Rubin D Christopher MS , 2018. A brief mindfulness-based intervention for primary care physicians: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Am J Lifestyle Med 12: 83–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Guillemin M Gillam L , 2015. Emotions, narratives, and ethical mindfulness. Acad Med 90: 726–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Crump JA Sugarman J , 2008. Ethical considerations for short-term experiences by trainees in global health. JAMA 300: 1456–1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Radstone S , 2005. Practising on the poor? Healthcare workers’ beliefs about the role of medical students during their elective. J Med Ethics 31: 109–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Harris H , 1998. Medical students’ electives abroad. Some care is better than none at all. BMJ 317: 1528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Doobay-Persaud A Evert J DeCamp M Evans CT Jacobsen KH Sheneman NE Goldstein JL Nelson BD , 2019. Extent, nature and consequences of performing outside scope of training in global health. Global Health 15: 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Elansary M, Provenzano AM, Barry M, Khoshnood K, Rastegar A, 2011. Ethical dilemmas in global clinical electives. The Columbia University Journal of Global Health 1: 24–27.

- 45. Provenzano AM Graber LK Elansary M Khoshnood K Rastegar A Barry M , 2010. Short-term global health research projects by US medical students: ethical challenges for partnerships. Am J Trop Med Hyg 83: 211–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Iserson KV Biros MH James Holliman C , 2012. Challenges in international medicine: ethical dilemmas, unanticipated consequences, and accepting limitations. Acad Emerg Med 19: 683–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. McCarthy J Deady R , 2008. Moral distress reconsidered. Nurs Ethics 15: 254–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Blackhall LJ Murphy ST Frank G Michel V Azen S , 1995. Ethnicity and attitudes toward patient autonomy. JAMA 274: 820–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Beyene Y , 1992. Medical disclosure and refugees. Telling bad news to Ethiopian patients. West J Med 157: 328–332. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. DeCamp M Rodriguez J Hecht S Barry M Sugarman J , 2013. An ethics curriculum for short-term global health trainees. Global Health 9: 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Asao S Lewis B Harrison JD Glass M Brock TP Dandu M Le P , 2017. Ethics Simulation in Global Health Training (ESIGHT). MedEdPORTAL 13: 10590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jacobs ZG Tittle R Scarpelli J Cortez K Aptekar SD Shamasunder S , 2019. Reflective practices among global health fellows in the HEAL Initiative: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med 34: 521–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Harrison JD Logar T Le P Glass M , 2016. What are the ethical issues facing global-health trainees working overseas? A multi-professional qualitative study . Healthcare (Basel) 4: 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bozinoff N Dorman KP Kerr D Roebbelen E Rogers E Hunter A O’Shea T Kraeker C , 2014. Toward reciprocity: host supervisor perspectives on international medical electives. Med Educ 48: 397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kung TH Richardson ET Mabud TS Heaney CA Jones E Evert J , 2016. Host community perspectives on trainees participating in short-term experiences in global health. Med Educ 50: 1122–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kraeker C Chandler C , 2013. “We learn from them, they learn from us”: global health experiences and host perceptions of visiting health care professionals. Acad Med 88: 483–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]