Abstract

Mycobacterium ulcerans and M. marinum are emerging necrotizing mycobacterial pathogens that reside in common reservoirs of infection and exhibit striking pathophysiological similarities. Furthermore, the interspecific taxonomic relationship between the two species is not clear as a result of the very high phylogenetic relatedness (i.e., >99.8% 16S rRNA sequence similarity), in contrast to only 25 to 47% DNA relatedness. To help understand the genotypic affiliation between these two closely related species, we performed a comparative analysis including PCR restriction profile analysis (PRPA), IS2404 restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP), and amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) on a set of M. ulcerans (n = 29) and M. marinum (n = 28) strains recovered from different geographic origins. PRPA was based on a triple restriction of the 3′ end region of 16S rRNA, which differentiated M. ulcerans into three types; however, the technique could not distinguish M. marinum from M. ulcerans isolates originating from South America and Southeast Asia. RFLP based on IS2404 produced six M. ulcerans types related to six geographic regions and did not produce any band with M. marinum, confirming the previous findings of Chemlal et al. (K. Chemlal, K. DeRidder, P. A. Fonteyne, W. M. Meyers, J. Swings, and F. Portaels, Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 64:270–273, 2001). AFLP analysis resulted in profiles which grouped M. ulcerans and M. marinum into two separate clusters. The numerical analysis also revealed subgroups among the M. marinum and M. ulcerans isolates. In conclusion, PRPA appears to provide a rapid method for differentiating the African M. ulcerans type from other geographical types but is unsuitable for interspecific differentiation of M. marinum and M. ulcerans. In comparison, whole- genome techniques such as IS 2404-RFLP and AFLP appear to be far more useful in discriminating between M. marinum and M. ulcerans, and may thus be promising molecular tools for the differential diagnosis of infections caused by these two species.

Mycobacterium ulcerans and M. marinum are slow-growing mycobacterial species with optimal growth temperatures of 30 to 33°C. These organisms are emerging as clinically significant pathogens associated with skin infections (5, 9). M. ulcerans infection, or Buruli ulcer (BU), was first described in Bairnsdale, Australia, in 1948 (17) and was subsequently found in numerous, mostly tropical countries in Africa, the Americas, Southeast Asia, and the central Pacific. Recent reports describe increases in the incidence of BU in Benin (13), Australia (6, 8, 12, 34), and Côte d'Ivoire (18). M. ulcerans causes chronic necrotizing ulcers in the skin of humans (22) and other mammals (22, 23). The epidemiology of BU is poorly understood, but most foci are associated with slow-flowing or stagnant water; however, the natural reservoir of M. ulcerans remains unknown. M. marinum, first described in Sweden (1), gives rise to infections in temperate climates and is the cause of fish tank and swimming pool granulomas (16).

M. ulcerans is often difficult to isolate from clinical specimens and usually requires 6 to 8 weeks to produce visible growth in primary culture (23, 24). Definitive identification of M. ulcerans is thus time-consuming; however, it can be recognized by classic molecular and microbiologic methods (20, 24). M. marinum, once cultured, is readily identified by using conventional mycobacterial characterization methods. It grows relatively quickly (1 to 2 weeks) and is easily recognized as a result of its photochromogenicity (20). While infections due to M. marinum can usually be treated with antimycobacterial drugs, very few cases of BU lesions respond favorably to antimicrobial therapy (2), making wide surgical excision and skin grafting the treatment of choice.

In the last decade, various DNA-based techniques have been used to classify mycobacteria (15, 25, 26, 30). All such studies have demonstrated a high taxonomic affiliation between M. ulcerans and M. marinum. Other attempts have targeted the 3′ end of 16S rRNA gene and found four subtypes of M. ulcerans related to their geographic origin, except for one isolate from Suriname, which exhibited the same sequence as M. marinum (20). The use of IS2404 resriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis (2) led to the classification of M. ulcerans into six groups, including the isolate from Suriname as M. ulcerans type VI. Unfortunately, because only a few M. marinum isolates were included in the last two studies (2, 20), no reliable conclusions could drawn made on an interspecific relationship between M. ulcerans and M. marinum.

In the present study, three DNA-based methods were evaluated for the purpose of the identification and typing of M. ulcerans and M. marinum to define the taxonomic and phylogenetic relationship of these two species. PCR restriction profile analysis (PRPA) was used for the first time for studies of M. ulcerans and M. marinum. This approach is comparable to the PCR restriction enzyme analysis method described by Telenti et al. (32). PRPA differs from the latter technique in both the targeted region for PCR (i.e., the 3′ end of the 16S rRNA gene) and the use of three restriction enzymes (RsaI, DraI, and EcoNI). As a follow-up to our previous study (2) we applied IS2404 RFLP to a comparable number of M. ulcerans and M. marinum strains to determine the phylogenetic relationship between these two species. Finally, in view of the ability of amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) analysis to discriminate continental types of M. ulcerans (10), we have evaluated the usefulness of this technique in differentiating M. ulcerans from M. marinum.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains used.

All 57 isolates included in this study are part of the Institute of Tropical Medicine collection and were assigned to the species M. ulcerans and M. marinum by conventional biochemical methods (36). Fresh subcultures were made on tubes of Löwenstein- Jensen medium. The collection comprised type and reference strains originally obtained from clinical sources. Some strains were kindly provided by V. Vincent (Institut Pasteur de Paris, Paris, France), P. Lavalle (Centro Dermatologico Pascua, Mexico, Mexico), W. R. Faber and P. Van Keulen (Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), T. Tønjum (Institute of Microbiology, Oslo, Norway), P. L. Small (National Institutes of Health, Hamilton, Mont.), and H. F. A. K. Huchzermeyer (Veterinary Research Institute, Onderstepoort, South Africa).

PCR restriction profile analysis.

The lysates from all isolates were obtained by resuspending a loopful of bacterial cells in 100 μl of TE (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8]) containing 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 and heating at 100°C for 15 min. Then 10 μl of lysate was added to 50 μl of PCR mixture containing 50 pmol each of primers P11 (5′-AGGAATTCTGGGTTTGACATGCACAGGA-3′) and P61 (5′-AAGGAGGTGATCCAGCCGCA-3′), 1 U of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Roche Molecular Systems), 200 μM each deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.4) and overlaid with mineral oil. Primers P11 and P61 target a 525-bp fragment of the 3′ end of the 16S rRNA gene of the genus Mycobacterium. Cycling was performed as follows: denaturation at 94°C for 5 min; amplification for 30 cycles at 94°C for 45 s, 56°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 45 s and a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. Subsequently, 7 μl of amplified DNA was electrophoresed through a 2% agarose gel, and bands were detected by ethidium bromide staining and UV transillumination. Restriction analysis of the amplification product was carried out for 2 h at 37°C in 20 μl of incubation buffer containing 15 U of restriction enzyme (RsaI, DraI, and EcoNI [Sigma]) and 8 μl of PCR product. Restriction fragment patterns were analyzed by gel electrophoresis of the restriction mixture at 50 V for 1.5 h in 3% small-fragment agarose gel (Eurogentec).

Southern blotting and preparation of the IS2404 probe.

The IS2404 probe was prepared by chemical labeling of a PCR product as described by van Embden et al. for the preparation of the IS6110 probe (35). The primers used were PGP3 and PGP4 as described previously (2).

For Southern blot analysis, M. ulcerans genomic DNA was digested with the appropriate restriction enzyme (PvuII) and separated overnight by electrophoresis through a 0.8% agarose gel (35). DNA was transferred to the Hybond N+ nylon membrane (Amersham Corp.) for 1 h in 0.4 M NaOH using a vacuum blotter system (Appligene-oncor). Hybridizations were performed at 42°C with high-stringency posthybridization washes (35). DNA was detected with the ECL direct system as specified by the manufacturer (Amersham Life Science).

AFLP analysis.

The DNA was isolated and purified as described previously (35). All protocols relating to the preparation of DNA templates for AFLP analysis were performed essentially as described previously (11). Oligonucleotide sequences, amplification procedures, electrophoresis conditions, and data capture and analysis have been described elsewhere (10).

RESULTS

A collection of 29 M. ulcerans and 28 M. marinum isolates was used in this study (Table 1). These isolates originated from a variety of sources and represent both temporal and geographic diversity. All the isolates were of human origin except for M. marinum, for which nine strains were of animal origin and one was from water (Table 1)

TABLE 1.

Source and origin of the mycobacterial strains used in this study

| Species | Strain | Source | Received from (other strain designation)a | Geographical origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. ulcerans(n = 29) | ITM7922 | Human | V.V., IPT141090018 | French Guiana |

| ITM842 | Human | V.K. 701357 | Suriname | |

| ITM 8756 | Human | ATCC 33728 | Japan | |

| ITM 5114 | Human | P.L. | Mexico | |

| ITM 94-1330 | Human | L.S., 143150 | Australia | |

| ITM 94-1325 | Human | L.S., 187859 | Australia | |

| ITM 5122 | Human | F.P. | Democratic Republic of Congo | |

| ITM 94-662 | Human | F.P. | Ivory Coast | |

| ITM 94-339 | Human | F.P. | Australia | |

| ITM 94-1327 | Human | F.P. | Australia | |

| ITM 94-1329 | Human | F.P. | Australia | |

| ITM 94-886 | Human | F.P. | Benin | |

| ITM 97-111 | Human | F.P. | Benin | |

| ITM 97-104 | Human | F.P. | Benin | |

| ITM 9146 | Human | F.P. | Benin | |

| ITM 94-815 | Human | F.P. | Ivory Coast | |

| ITM 97-684 | Human | F.P. | Benin | |

| ITM 97-490 | Human | F.P. | Benin | |

| ITM 96-658 | Human | F.P. | Angola | |

| ITM 97-680 | Human | F.P. | Angola | |

| ITM 95-1112 | Human | F.P. | Australia | |

| ITM 9114 | Human | F.P. | Benin | |

| ITM 9550 | Human | D.D., 17679 | Australia | |

| ITM 9540 | Human | D.D., 11098 | Australia | |

| ITM 9537 | Human | D.D., 11878 | Papua New Guinea | |

| ITM 94-1324 | Human | L.S., 176862 | Australia | |

| ITM 8849 | Human | D.D., 8471/69 | Australia | |

| ITM 5147 | Human | ATCC 19423T | Australia | |

| ITM 94-1326 | Human | L.S., 93160339 | Australia | |

| M. marinum(n = 28) | ITM 94-996 | Fish | K.H. | South Africa |

| US H35392/93 | Human | P.S. | United States | |

| US M6 | Fish | P.S. | United States | |

| ITM 7732 | Fish | ATCC 927T | United States | |

| ITM 94-979 | Fish | K.H. | South Africa | |

| IPP 99000876 | Human | V.V. | France | |

| IPP 99/890 | Human | V.V. | France | |

| IPP 2000449 | Human | V.V. | France | |

| IPP 99000843 | Huamn | V.V. | France | |

| IPP 2000355 | Human | V.V. | France | |

| US LS | Fish | P.S. | United States | |

| IPP 031038 | Human | V.V. | France | |

| TON F106/91 | Human | T.T. | Norway | |

| IPP 99/363 | Human | V.V. | France | |

| ITM 8022 | Human | F.P. | Belgium | |

| ITM 94-56 | Human | F.P. | Belgium | |

| ITM 97-1321 | Axololt. | F.P. | Belgium | |

| IPP 99000821 | Human | V.V. | France | |

| ITM 98-852 | Human | F.P. | Italy | |

| ITM 00-533 | Human | F.P. | Belgium | |

| ITM 99-822 | Human | F.P. | Belgium | |

| ITM 99-2570 | Human | F.P. | Belgium | |

| ITM 99-3021 | Human | F.P. | Belgium | |

| TON T25/84 | Water | T.T. | Norway | |

| IPP CCUG533 | Human | V.V. | France | |

| ITM 1717 | Armadillo | F.P. | United States | |

| ITM 1726 | Armadillo | F.P. | United States | |

| ITM 97-1320 | Axololt. | F.P. | Belgium |

V.V., V. Vincent Institut Pasteur de Paris, Paris, France; F.P., F. Portaels, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium; P.L., P. Lavalle, Centro Dermatologico Pascua, Mexico, Mexico; P.L., P.L. Small, National Institutes of Health, Hamilton Mont., T.T., T. Tønjum, Institute of Microbiology, Oslo, Norway; V.K., P. Van Keulen, Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; D.D., D. Dawson, Laboratory of Microbiology and Pathology, Queensland Health, Brisbane, Australia; L.S., L. Stanford, School of Pathology, London, United Kingdom; K.H., K. Huchzermeyer, Veterinary Research Institute, Onderstepoort, South Africa.

PCR restriction profile analysis.

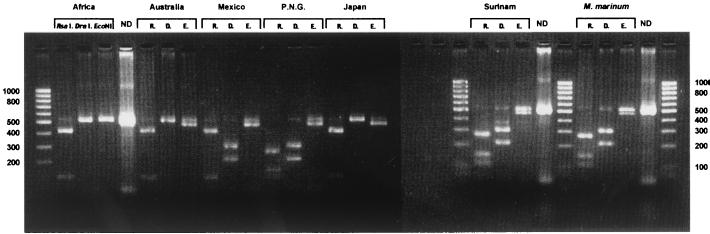

In Fig. 1, the various profiles derived from the three restrictions of the 525-bp fragment 16S rRNA amplicons are shown for M. ulcerans and M. marinum strains originating from different geographical regions. Table 2 lists the observed sizes of the fragments from the digested amplicons which are compatible with the predicted sizes obtained by GeneBank sequence analysis of the 3′-end 16S RNA gene. All the African M. ulcerans isolates tested yielded the same profile with RsaI (data not shown), and a highly similar banding pattern was also produced by the Australian, Mexican, and Japanese strains. On the other hand, the Papua New Guinean and Surinamese strains of M. ulcerans and all the M. marinum isolates exhibited the same pattern with RsaI. No DraI restriction sites were found with M. ulcerans strains from Africa, Australia, or Japan. All the M. marinum strains and the M. ulcerans strains from Mexico, Papua New Guinea, and Suriname generated two bands at 300 and 220 bp. With EcoNI there was incomplete digestion with all the isolates except for the African M. ulcerans strains. By combining the three restriction profiles (Fig. 1), we found that all the M. ulcerans strains tested in this study are categorized into three types (African, Australian, and Mexican), except for the Papuan New Guinean and Surinamese isolates, which exhibited the same profiles as all the M. marinum isolates evaluated. PRPA applied to more than 50 African strains of M. ulcerans resulted in the same profile. Furthermore, 18 relatively closely related mycobacterial species, subjected to the same technique and with the same set of restriction enzymes, produced patterns that differed from the four profiles shown in Fig. 1 (K. Chemlal, unpublished data).

FIG. 1.

Examples of PCR restriction profiles obtained from a representative set of strains using three restriction enzymes, RsaI, DraI, and EcoNI. The first and last lanes show the 100-bp ladder. ND, no digested PCR product; R, D, and E, RsaI, DraI, and EcoNI, respectively, P.N.G., Papua New Guinea.

TABLE 2.

Fragment sizes obtained by triple restriction of the 16S rRNA PCR product of M. ulcerans and M. marinum

| Straina |

RsaI

|

DraI

|

EcoNI

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length of fragments observed (bp) | No. of restriction sites | Length of fragments observed (bp) | No. of restriction sites | Length of fragments observed (bp) | No. of restriction sites | |

| Africa (type I)a | 419, 120 | 1 | 525 | 0 | 525 | 0 |

| Australia (type II)a | 419, 120 | 1 | 525 | 0 | 500 | 1 |

| Mexico (type III)a | 419, 120 | 1 | 300, 220 | 1 | 500 | 1 |

| Papua New Guinea | 272, 147, 120 | 2 | 300, 220 | 1 | 500 | 1 |

| Japana (type IV)a | 419, 120 | 1 | 525 | 0 | 500 | 1 |

| Suriname | 272, 147, 120 | 2 | 300, 220 | 1 | 500 | 1 |

| M. marinum | 272, 147, 120 | 2 | 300, 220 | 1 | 500 | 1 |

Classification reported by Portaels et al. (20).

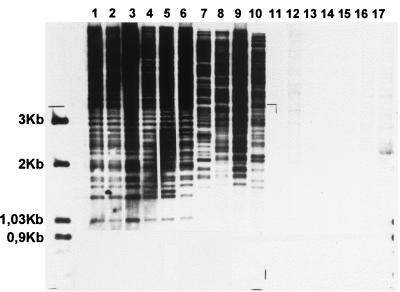

IS2404 RFLP profiles.

Representative patterns obtained with chromosomal DNA of M. ulcerans and M. marinum probed with IS2404 are shown in Fig. 2. From the strains shown in Table 1, only representatives of M. ulcerans produced an IS2404 RFLP band pattern (lanes 1 to 10) whereas no profile was obtained with seven selected M. marinum strains (lanes 11 to 17). Within the IS2404 RFLP fingerprints of M. ulcerans, the 3-kb zone was polymorphic and allowed further subtyping of the M. ulcerans isolates into six groups (Fig. 2 legend).

FIG. 2.

A representative Southern blot obtained with 10 M. ulcerans (lanes 1 to 10) and 7 M. marinum (lanes 11 to 17) strains from different geographic origins. Lanes: 1 to 3, African; 4, reference strain ATCC 19423; 5, Australian; 6, Southeast Asian; 7, Asian; 8 and 9, South America; 10, Mexican; 11 and 12, United States; 13, reference strain ATCC 927; 14 and 15, Belgian; lanes 16 and 17, South African. The molecular size (in kilobases) is shown on the left.

AFLP analysis.

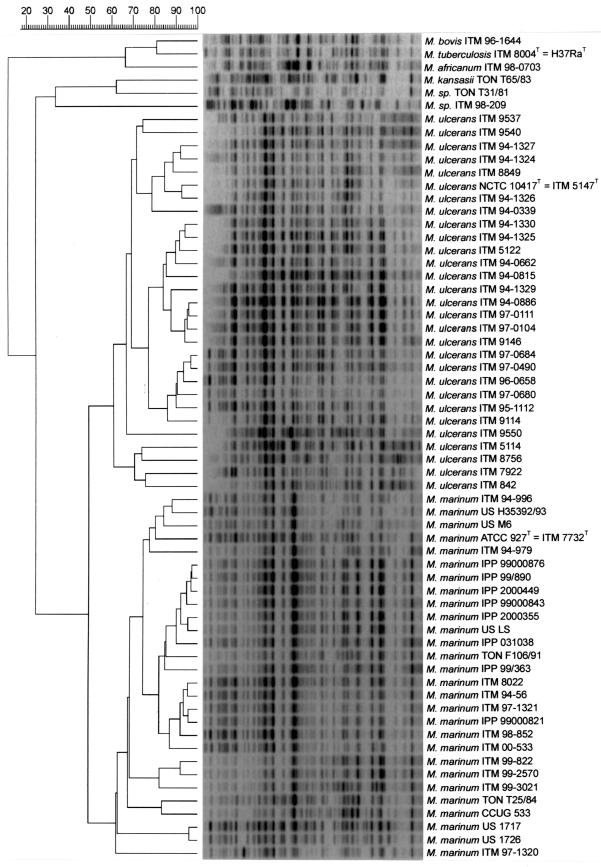

AFLP patterns were obtained by using the primer combination A02 plus T02 (10). Typically, the AFLP patterns generated comprised 30 to 50 bands (data not shown). Following numerical analysis using the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, the 57 strains included in this study were grouped in two AFLP clusters at a delineation level of 60% (Fig. 3). These two clusters uniformly corresponded to the phenotypic species identifications of the strains, i.e., M. ulcerans and M. marinum. Within each of these clusters, a number of intraspecific subdivisions could be observed. Compared to the IS2404 RFLP and PRPA results, there was no correlation with geographic origins.

FIG. 3.

Numerical analysis of normalized AFLP band patterns generated from M. ulcerans (n = 29) and M. marinum (n = 28) using primer combination A02 and T02. In addition, six outlying strains representing other mycobacterial taxa were included: M. tuberculosis (ITM 8004T), M. bovis (ITM 96-1644), M. africanum (ITM 98-0703), M. kansaii (TON T65/83), and two Mycobacterium strains (TON T31/81 and ITM 98-209). The dendrogram was constructed using the unweighted paired-group using arithmetic averages with correlation levels expressed as percentages of the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient. The clusters representing M. ulcerans and M. marinum were defined at a delineation level of 60%.

DISCUSSION

The identification of mycobacterial species constitutes a critical step in patient management because the results obtained influence the choice of appropriate treatment. Classical procedures to establish the species of mycobacteria based on conventional biochemical tests can take several weeks and may generate inaccurate diagnoses. For M. ulcerans, there are only a few phenotypic characteristics, making additional molecular tests essential for conclusive identification. PCR-based methods offer several advantages including speed, sensitivity, and specificity (3, 4, 15, 21, 30). In the present investigation, a combination of PCR amplification of a 525-bp 16S rRNA fragment and a triple-restriction analysis (PRPA) was used to differentiate M. ulcerans from the closely related species M. marinum. The results of PRPA on a set of geographically diverse M. ulcerans isolates showed three different PRPA profiles (Table 2): subtype 1, representing the African strains; subtype 2, representing the Australian and Asian strains; and subtype 3, representing the Mexican strain. The M. ulcerans isolates from South America (strains ITM842 and ITM7922) gave the same profile as M. marinum, showing that PRPA is not suitable for a clear-cut differentiation between these two species. This result is in accord with previous findings that the 3′-end 16S rRNA sequence of the Surinamese M. ulcerans and M. marinum strains are identical (20). All the African and Australian M. ulcerans strains as well as all the M. marinum strains included in this study yielded highly similar PRPA patterns with the three restriction enzymes employed. This finding suggests that the discriminatory power of PRPA to differentiate strains within certain geographical regions is limited. However, PRPA proved to be a rapid method for the identification of M. ulcerans subtypes I and II compared to the laborious procedures involved in sequencing.

The pattern of conserved and variable domains within the 16S rRNA molecule offers the unique advantage of a single amplification reaction for identification of virtually all Mycobacterium spp. (14, 26, 29, 37). Unfortunately, the number of polymorphic sites in the 16S rDNA in the genus Mycobacterium is rather low since some species have the same sequence (M. kansasii and M. gastri) or possess a very high degree of sequence similarity (99.9%) (M. malmoense and M. szulgai) (26). Molecular distinction between M. ulcerans and M. marinum based on 16S rRNA is very difficult due to the existence of identical signature regions and only two single-nucleotide differences at the 3′ end of the gene (20). As shown in the present study (Fig. 1; Table 2), the high degree of conservation of the mycobacterial 16S rRNA gene may explain why PRPA of the 16S rRNA genes of M. ulcerans and M. marinum is not useful for discriminating between these two species. Other molecular methods have tried to circumvent this limitation in species discrimination (27), including sequence analysis of a 360-bp gene fragment characteristic for GyrA lacking an intein and the 16-kDa HSP, an α-crystalline homologue (I. C. Shamputa, unpublished data). However, none of these methods so far permits an unequivocal differentiation between M. ulcerans and M. marinum.

To address the shortcomings of the PRPA method for identifying M. ulcerans and M. marinum, the current investigation was extended by an evaluation of two other molecular methods, namely, IS2404 RFLP and AFLP. The IS2404 RFLP technique was recently used in our laboratory (2) and was able to distinguish six groups in M. ulcerans. In the present study, the same results were obtained by analyzing the polymorphic region (<3 kb) of all the M. ulcerans profiles (Fig. 2). None of the M. marinum strains included in this study provided a band with the IS2404-specific probe (Fig. 2), confirming that this insertion sequence is specific to M. ulcerans. The presence of numerous copies of the IS2404 insertion sequence in M. ulcerans (30) and its absence in M. marinum suggests that the highly related genomes of these two species may have been subjected to an evolutionary rearrangement by acquiring or losing insertion sequences. A recent genetic analysis of M. ulcerans and M. marinum, including multilocus sequencing and macrorestriction fragment polymorphism analysis, strongly supports this hypothesis (31). Because the IS2404 RFLP method is not helpful at the subspecific level for the identification of M. marinum, an alternative DNA fingerprinting technique that encompasses the entire genome is essential. The PCR-based AFLP technique is such a whole-genome coverage technique and has already been successfully applied as a reproducible and reliable taxonomic tool for the differentiation of M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, and M. ulcerans (10). In the present study, AFLP was evaluated for its ability to discriminate among strains of M. ulcerans and M. marinum at the interspecific level. Using the primer combination A02 plus T02, both having one C extension at their 3′ ends (10), visual inspection as well as clustering analysis using the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient (Fig. 3) revealed that M. ulcerans can be clearly separated from M. marinum by AFLP. In sharp contrast to their very high 16S rRNA sequence homology (>99.8%), DNA-DNA hybridization results have shown that M. ulcerans and M. marinum exhibit only 25 to 47% DNA homology (33). Since AFLP clustering is known to support classification based on DNA hybridization groups in a wide range of bacterial genera (28), it is not surprising that M. ulcerans and M. marinum represent two distinct AFLP groups. Furthermore, numerical analysis of normalized AFLP band patterns also revealed two or more subclusters in each of the two species-specific AFLP clusters (Fig. 3). Within M. ulcerans, these subgroupings did not correlate with the geographical origin of the strains as was observed with PRPA (Fig. 1). However, as previously demonstrated, the use of primer combination A02 and T01 in conjunction with a band-based similarity coefficient for numerical analysis differentiated African from Australian M. ulcerans types (10). Also, in the AFLP cluster encompassing M. marinum, there was no clear relationship between subgroupings and the source or origin of strains. Therefore, we recommend that the use of multiple AFLP primer combinations and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis be further explored for epidemiological studies on M. marinum.

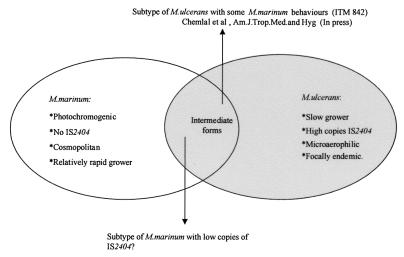

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates the limitations of the 16S rRNA-based PRPA technique to differentiate M. ulcerans from M. marinum and the usefulness of the DNA fingerprinting techniques utilizing IS2404 RFLP and AFLP to distinguish between these two species. Collectively, the striking phylogenetic closeness reported by Tønjum et al. (33) and the IS2404 RFLP results presented in this study further support the recent findings of Stinear and et al. (31) in which a comparative genetic analysis revealed recent divergence of M. ulcerans from M. marinum. In our opinion, this hypothesis can be further supported by the following two observations: (i) the IS2404 element is present in high copy number in M. ulcerans collected from different geographic sources (30) but absent in the closely related species M. marinum; and (ii) similar to the occurrence of IS6110 in M. tuberculosis (7), the microaerophilic growth conditions required for M. ulcerans (19) may play a role in the stimulation of transposition of IS2404 into the genome of these species. The key to confirming the hypothesized recent divergence of M. ulcerans from M. marinum would be finding a missing link between the two, e.g., an M. marinum strain with a low IS2404 copy number (Fig. 4), indicating an evolving characteristic within the taxon.

FIG. 4.

Hypothetical presentation showing some differential characteristics of M. marinum and M. ulcerans and the postulated position of putative transitory forms between these two taxa.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank D. Dawson, P. Lavalle, P. H. J. van Keulen, J. L. Stanford, P. L. C. Small, T. Tønjum, and F. A. K. Huchzermeyer for providing M. ulcerans and M. marinum isolates. We also thank J. C. Palomino and S. R. Pattyn for assistance and advice.

This work was generously supported by the Damien Foundation (Brussels) and the Belgian Agency for Development (Project: Buruli ulcer in Benin). It was also partially supported by The Fund for Scientific Research, Flanders (Belgium) (F.W.O.-Vlaanderen) (contract G.0368.98).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aronson J D. Spontaneous tuberculosis in salt water fish. Infect Dis. 1926;39:315–320. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chemlal K, De Ridder K, Fonteyne P A, Meyers W M, Swings J, Portaels F. The use of IS 2404 restriction fragment length polymorphism suggests the diversity of Mycobacterium ulcerans from different geographical areas. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;64:270–273. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.64.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Beenhouwer H, Liang Z, de Rijk P, van Eekeren C, Portaels F. Detection and identification of mycobacteria by DNA-DNA amplification and oligonucleotide-specific capture plate hybridization. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2994–2998. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.11.2994-2998.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devalois A, Goh K H, Rastogi N. Rapid identification of mycobacteria to species level by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of hsp65 gene and proposition of an algorithm to differentiate 34 mycobacterial species. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2969–2973. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.2969-2973.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edelstein H. Mycobacterium marinum skin infections. Report of 31 cases and review of the literature. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1359–1364. doi: 10.1001/archinte.154.12.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flood P, Street A, O'Brien P, Hayman J. Mycobacterium ulcerans infection on Philip Island, Victoria. Med J Aust. 1994;160:160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghanekar K, Mcbride A, Dellagostin O, Thorne S, Mooney R, McFadden J. Stimulation of transposition of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis insertion sequence IS6110 by exposure to microaerobic environment. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:982–993. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goutzamanis J J, Gilbert G L. Mycobacterium ulcerans infection in Australian children: report of eight cases and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:1186–1192. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.5.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayman J. Out of Africa: observations on the histopathology of Mycobacterium ulcerans infections. Clin Pathol. 1993;46:5–9. doi: 10.1136/jcp.46.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huys G, Rigouts L, Chemlal K, Portaels F, Swings J. Evaluation of amplified fragment length polymorphism analysis for inter- and intraspecific differentiation of Mycobacterium bovis, M. tuberculosis, and M. ulcerans. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:3675–3680. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.10.3675-3680.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janssen P, Coopman R, Huys G, Swings J, Bleeker M, Vos P, Zabeau M, Kersters K. Evaluation of the DNA fingerprinting method AFLP as a new tool in bacterial taxonomy. Microbiology. 1996;142:1881–1893. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-7-1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson P D, Veitch M G, Leslie D E, Flood P E, Hayman J A. The emergence of Mycobacterium ulcerans in Melbourne. Med J Aust. 1996;164:76–78. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1996.tb101352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Josse R, Guédénon A, Aguiar J, Anagonou S, Zinsou C, Porst C, Foundohou J, Touze J E. L'ulcère de Buruli, une pathologie peu connue au Bénin. A propos de 227 cas. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1994;87:170–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirschner P, Springer B, Vogel U, Meier A, Wrede A, Kiekenbeck M, Bange F C, Böttger E C. Genotypic identification of mycobacteria by nucleic acid sequence determination: report of a 2-year experience in a clinical laboratory. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2882–2889. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.11.2882-2889.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kox L F F, van Leeuwen J, Knijper S, Jansen H M, Kolk A H. PCR assay based on DNA coding for 16S rRNA for detection and identification of mycobacteria in clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3225–3233. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3225-3233.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linnell F, Norden A. Mycobacterium balnei. A new acid-fast bacillus occuring in swimming pools and capable of producing skin lesions in humans. Acta Tuberc Scand. 1954;33(Suppl. 1):26–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacCallum P, Tolhurst J C, Buckle G, Sissons H A. A new mycobacterial infection in man. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1948;60:93–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marston B J, Diallo M O, Horsburgh C R, Jr, Diomande I, Saki M Z, Kanga J M, et al. Emergence of Buruli ulcer disease in the Daloa region of Côte d'Ivoire. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;52:219–224. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1995.52.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palomino J C, Obiang A M, Realini L, Meyers W M, Portaels F. Effect of oxygen on Mycobacterium ulcerans growth in the BACTEC system. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3420–3422. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3420-3422.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Portaels F, Fonteyne P-A, de Beenhouwer H, de Rijk P, Guédénon A, Hayman J, Meyers W M. Variability in the 3′ end of 16S rRNA sequences of Mycobacterium ulcerans is related to geographic origin of isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:962–965. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.962-965.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Portaels F, Aguiar J, Fissette K, Fonteyne P-A, DeBeenhouwer H, de Rijk P, Guédénon A, Lemans R, Steunou C, Zinsou C, Dumonceau J M, Meyers W M. Direct detection and identification of Mycobacterium ulcerans in clinical specimens by PCR and oligonucleotide-specific capture plate hybridization. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1097–1100. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1097-1100.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Portaels F. Epidemiology of mycobacterial diseases. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:207–222. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(95)00004-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Portaels F, Chemlal K, Elsen P, Johnson P D R, Hayman J A, Kirkwood R, Meyers W M. Mycobacterium ulcerans in wild animals. Rev Sci Tech. 2001;20:252–264. doi: 10.20506/rst.20.1.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Portaels F. Basic microbiology. In: Asiedu K, Scherpbies R, Raviglione M, editors. Buruli ulcer: Mycobacterium ulcerans infection. WHO/CDS/CPE/GBUI/2000. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2000. pp. 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts B. Molecular and Immunological studies of Mycobacterium ulcerans. Ph. D. thesis. Cairne, Australia: James Cook University; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rogall T, Wolters J, Floher T, Böttger E C. Towards a phylogeny and definition of the species at the molecular level within the genus Mycobacterium. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1990;40:323–330. doi: 10.1099/00207713-40-4-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sander P, Alcaide F, Richter I, Frischkorn K, Tortoli E, Springer B, Telenti A, Böttger E. Inteins in mycobacterial GyrA are a taxonomic character. Microbiology. 1998;144:589–591. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-2-589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Savelkoul P H M, Aarts H J M, de Haas J, Dijkshoorn L, Duin B, Otsen M, Rademaker J W, Schouls L, Lenstra J A. Amplified fragment length polymorphism analysis: the state of the art. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3083–3091. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.10.3083-3091.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stahl D A, Urbance J W. The division between fast- and slowly growing species corresponds to natural relationships among the mycobacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:116–124. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.1.116-124.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stinear T, Ross B C, Johnson P D R, Marino L, Robins-Browne R M, Oppedisano F, Sievers A, Davies J K. Identification and characterisation of IS2404 and IS2606: two distinct repeated sequences for detection of Mycobacterium ulcerans. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1018–1023. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.4.1018-1023.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stinear T, Jenkin G, Johnson P D, Davies J K. Comparative genetic analysis of Mycobacterium ulcerans and Mycobacterium marinum reveals evidence of recent divergence. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:6322–6330. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.22.6322-6330.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Telenti A, Marchesi F, Balz M, Bally F, Böttger E C, Bodmer T. Rapid identification of mycobacteria to the species level by polymerase chain reaction and restriction enzyme analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:175–178. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.175-178.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tϕnjum T, Welty D B, Jantzen E, Small P L. Differentiation of Mycobacterium ulcerans, M. marinum, and M. haemophilum: mapping of their relationships to M. tuberculosis by fatty acid profile analysis, DNA-DNA hybridization, and 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:918–925. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.4.918-925.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsang A Y, Faber E R. The primary isolation of Mycobacterium ulcerans. Am J Clin Pathol. 1973;59:688–692. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/59.5.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Embden J D A, Cave M D, Crawford J T, Dale W, Eisenach K D, Gicquel B, Hermans P, Martin C, McAdam R, Shinnick T M, Small P M. Strain identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by DNA fingerprinting: recommendations for a standardized methodology. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:406–409. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.406-409.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vincent Lévy-Frébault V, Portaels F. Proposed minimal standards for the genus Mycobacterium and for the description of new slowly growing Mycobacterium species. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:315–323. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-2-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wayne L G, Good R C, Krichevsky M I, Blacklock Z, David H L, Dawson D, Gross W, Hawkins J, Juhlin I, Käppler W, Kleeberg H H, Lévy-Frebault V, McDurmont, Nel E E, Portaels F, Rüsch-Gerdes S, Schröder K H, Silcox V A, Szabo I, Tsukamura M, van Den Breen L, Vergmann B, Yakrus M A. Third report of cooperative, open-ended study of slowly growing mycobacteria by International Working Group on Mycobacterial Taxonomy. Int J Syst Microbiol. 1989;39:267–278. doi: 10.1099/00207713-41-4-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]