Abstract

Background

Studies from multiple contexts conceptualize organized crime as comprising different types of criminal organizations and activities. Notwithstanding growing scientific interest and increasing number of policies aiming at preventing and punishing organized crime, little is known about the specific processes that lead to recruitment into organized crime.

Objectives

This systematic review aimed at (1) summarizing the empirical evidence from quantitative, mixed methods, and qualitative studies on the individual‐level risk factors associated with the recruitment into organized crime, (2) assessing the relative strength of the risk factors from quantitative studies across different factor categories and subcategories and types of organized crime.

Methods

We searched published and unpublished literature across 12 databases with no constraints as to date or geographic scope. The last search was conducted between September and October 2019. Eligible studies had to be written in English, Spanish, Italian, French, and German.

Selection Criteria

Studies were eligible for the review if they:

Reported on organized criminal groups as defined in this review.

Investigated recruitment into organized crime as one of its main objectives.

Provided quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods empirical analyses.

Discussed sufficiently well‐defined factors leading to recruitment into organized crime.

Addressed factors at individual level.

For quantitative or mixed‐method studies, the study design allowed to capture variability between organized crime members and non‐members.

Data Collection and Analysis

From 51,564 initial records, 86 documents were retained. Reference searches and experts' contributions added 116 additional documents, totaling 202 studies submitted to full‐text screening. Fifty‐two quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods studies met all eligibility criteria. We conducted a risk‐of‐bias assessment of the quantitative studies while we assessed the quality of mixed methods and qualitative studies through a 5‐item checklist adapted from the CASP Qualitative Checklist. We did not exclude studies due to quality issues. Nineteen quantitative studies allowed the extraction of 346 effect sizes, classified into predictors and correlates. The data synthesis relied on multiple random effects meta‐analyses with inverse variance weighting. The findings from mixed methods and qualitative studied were used to inform, contextualize, and expand the analysis of quantitative studies.

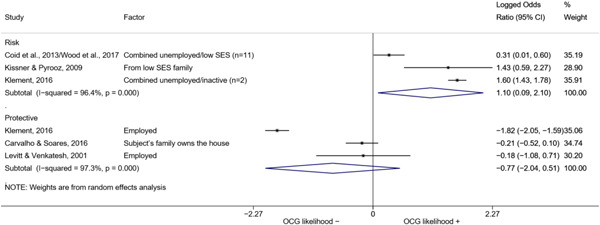

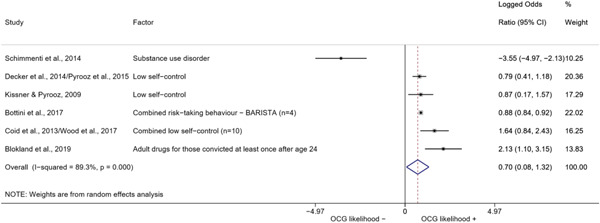

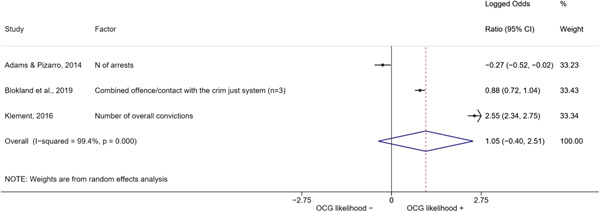

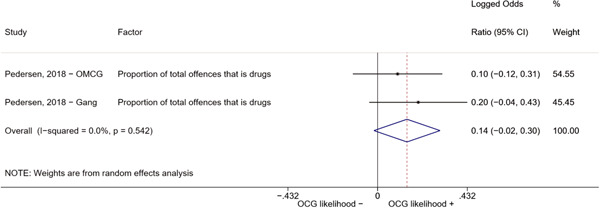

Results

The amount and the quality of available evidence were weak, and most studies had a high risk‐of‐bias. Most independent measures were correlates, with possible issues in establishing a causal relation with organized crime membership. We classified the results into categories and subcategories. Despite the small number of predictors, we found relatively strong evidence that being male, prior criminal activity, and prior violence are associated with higher odds of future organized crime recruitment. There was weak evidence, although supported by qualitative studies, prior narrative reviews, and findings from correlates, that prior sanctions, social relations with organized crime involved subjects, and a troubled family environment are associated with greater odds of recruitment.

Authors' Conclusions

The available evidence is generally weak, and the main limitations were the number of predictors, the number of studies within each factor category, and the heterogeneity in the definition of organized crime group. The findings identify few risk factors that may be subject to possible preventive interventions.

1. PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

Evidence suggests individual‐level factors predict recruitment into organized crime.

1.1. The review in brief

There is relatively strong evidence that being male and having committed prior criminal activity and violence are associated with future organized crime recruitment. There is weak evidence that prior sanctions, social relations with organized crime‐involved subjects and a troubled family environment are associated with recruitment.

1.2. What is this review about?

This systematic review examines what individual‐level risk factors are associated with recruitment into organized crime.

Despite the increase of policies addressing organized crime activities, little is known about recruitment. Existing knowledge is fragmented and comprises different types of organized criminal groups.

Recruitment refers to the different processes leading individuals to stable involvement in organized criminal groups, including mafia, drug trafficking organizations, adult gangs and outlawed motorcycle gangs. This systematic review excludes youth (street) gangs, prison gangs and terrorist groups.

What is the aim of this review?

This Campbell systematic review examines individual‐level risk factors related to recruitment into organized crime groups. The review summarizes evidence from 52 studies, including 19 quantitative studies, 28 qualitative studies, and five studies that apply mixed methods.

1.3. What studies are included?

This review examines empirical studies of sufficiently well‐defined factors associated with involvement in organized crime. Nineteen quantitative, 28 qualitative, and five mixed‐methods studies met all eligibility criteria and were included in the systematic review.

Quantitative studies had to compare data on organized crime members and non‐organized crime members. The meta‐analyses of risk factors associated with recruitment focused on the evidence from 19 quantitative studies.

1.4. What are the main findings of this review?

All the included studies presented some important methodological weaknesses. Risk factors were divided into predictors (when the factors occurred before recruitment into organized crime) or correlates (factors measured at the same moment or subsequent to recruitment). Most risk factors were correlates, which causes problems in establishing a causal relation with recruitment into organized crime.

Despite the small number of predictors, there is relatively strong evidence that being male and having committed prior criminal activity and violence are associated with higher probability of future organized crime recruitment.

There is weak evidence, although supported by qualitative studies, prior narrative reviews and findings from correlates, that prior sanctions, social relations with organized crime‐involved subjects and a troubled family environment are associated with greater likelihood of recruitment.

Evidence from correlates indicates that higher levels of education are associated with lower probability of organized crime recruitment Conversely, low self‐control, sanctions, a troubled family environment, violence, being in a relationship, and poor economic conditions are associated with a higher likelihood of involvement in organized crime. These findings, however, should not be confused with predictors, due to difficulties in establishing a clear causal relation between the correlates and organized crime recruitment.

1.5. What do the findings of this review mean?

The available evidence is weak. There was a small number of studies for most factor categories. Most quantitative studies were from the United States and the United Kingdom. Thus, it may be difficult to apply the findings to organized crime groups in other countries.

Furthermore, this review encompassed a variety of organized crime groups. Different risk factors may drive recruitment into different types of groups, which may affect the quality of the evidence. Notwithstanding these limitations, the findings identify risk factors that may point to areas for possible interventions.

1.6. How up‐to‐date is this review?

The review authors searched for studies up to October 2019.

2. BACKGROUND

2.1. The issue: Organized crime

The differences in the study of organized crime have influenced the challenge of defining and conceptualizing the concept itself, which has long been debated among researchers (Finckenauer, 2005; Hagan, 1983, 2006; Smith, 1975; Von Lampe, 2008, 2016). The term ‘organized crime’ first emerged in the late 19th century in the United States, but its meaning varied over the past century (Fijnaut & Paoli, 2004; Kenney & Finckenauer, 1994; Woodiwiss, 2001). Organized crime was first associated with activities protected by public officials (e.g., prostitution and racketeering), and subsequently also with fraud and extortion (Woodiwiss, 2003). In the 1950s, the concept evolved toward the “alien conspiracy” approach, due to the influence of the media and US institutions such as the Kefauver Committee. The alien conspiracy approach contended that organized crime was predominantly composed of foreign, especially Italian immigrants, criminals organized in formally hierarchical groups and dominating profitable illegal markets such as gambling, prostitution, and narcotics (Cressey, 1969; Smith, 1976). By the 1960s, several scholars rejected this approach, suggesting that organized crime mostly revolves on social connections, patron‐client relationships and the social organization of the underworld (Albini, 1971; Blok, 1974; Hess, 1970/1973; Ianni & Reuss‐Ianni, 1972). In the 1970s, the paradigm of the “illegal enterprise” replaced the alien conspiracy, shifting the focus on the role of criminal organizations in supplying illegal products and services (Arlacchi, 1983; Block, 1980/1983; Reuter, 1983; Smith, 1975). A particular theoretical interpretation contended that organized crime specializes in the supply of illegal protection (Gambetta, 1993; Varese, 2005, 2010). The economic perspective became equally predominant in Europe, which had largely remained out of the debate until the mid‐1970s (Fijnaut & Paoli, 2004; Paoli & Vander Beken, 2014). Ever since, the organized crime label has become increasingly popular all over the world, and authors have proposed a variety of definitions (Von Lampe, 2016).

Notwithstanding several shifts in the conceptualization of organized crime, the theoretical debate has so far failed to achieve an agreement on its definition. Several studies reviewed existing definitions to identify common dimensions (Finckenauer, 2005; Hagan, 1983, 2006; Maltz, 1976; Van Duyne, 2004; Varese, 2010, 2017; Von Lampe et al., 2006). These efforts yielded several conclusions. First, the problematic element in the concept of organized crime is the term “organized” and its operationalization. Consequently, most interpretations attempted to distinguish organized crime from “crimes that are organized,” that is, complex criminal activities requiring important levels of coordination among the participants but lacking the additional features of organized crime (Finckenauer, 2005; Hagan, 1983, 2006). Second, it is important to distinguish between the characteristics of the group and those of the crimes and activities it perpetrates (Paoli & Vander Beken, 2014; Reuter & Paoli, 2020; Von Lampe, 2016). When considering the groups, organized crime should be conceptualized as an ordinal rather than a binary category, with groups exhibiting different levels of intensity of specific characteristics within a continuum rather than groups having/not having specific elements defined by an arbitrary threshold (Hagan, 1983, 2006, p. 200; Paoli & Vander Beken, 2014). Third, notwithstanding the heterogeneity in the literature, most contributions identify a core set of dimensions of organized crime and namely: (a) its nonideological nature, that is, criminal organizations do not have political or religious motivations; (b) organized crime is profit oriented, aiming to achieve illegal profits; (c) continuity, that is, organized crime aims at the repeated commission of an indeterminate number of crimes; (d) organized crime uses threat and violence to perpetrate crimes; (e) organized crime has an internal organization, not necessarily a formal hierarchy, such as a division of tasks (f) organized crime is embedded in the surrounding social environment and actively interacts with it, for example, by corrupting public officials, providing extra‐legal protection, controlling legal activities, influencing politics (Reuter & Paoli, 2020; Varese, 2017). While the attempts to define organized crime share important similarities, some scholars have contended that the very concept of organized crime is problematic and the result of a social construct rather than a useful tool for empirical analysis (Van Duyne, 1995; Von Lampe et al., 2006). Notwithstanding these criticisms, organized crime has remained a popular concept in the scholarly literature, in the policy debate, and in the public attention.

This systematic review relies on the definition provided by Article 2 of the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (United Nations, 2000):

“Organized criminal group” shall mean a structured group of three or more persons, existing for a period of time and acting in concert with the aim of committing one or more serious crimes or offences established in accordance with this Convention, to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit.

The UN Convention definition is the result of international efforts in stepping up the fight against criminal organizations in the 1990s. Although it has been criticized for being excessively vague (Calderoni, 2012; McClean, 2007; Paoli, 2014), the UN definition suits the purposes of this systematic review by providing a broad, inclusive, operationalization of organized crime. This allows for more flexibility when searching for potentially relevant studies, encompassing a variety of organized criminal groups as the mafias, drug trafficking groups, and some criminal gangs.

2.2. Recruitment into organized crime

This systematic review aims at summarizing and consolidating the knowledge of the factors associated with recruitment into organized crime. Entering into an organized criminal group is a significant step in the life of an individual, constituting a negative turning point in life and determining an increase in the risk of offending, harm, and incarceration (Fuller et al., 2019; Laub & Sampson, 1993; Melde & Esbensen, 2011; Morgan et al., 2020). Furthermore, individuals involved in criminal organizations are responsible for serious crimes with wide‐ranging societal implications, including loss of lives, economic impact, and politics (Lavezzi, 2008; Pinotti, 2015). For this review, recruitment refers to the different processes leading individuals to the stable involvement into organized criminal groups. This interpretation comprises individuals deliberately choosing to participate in criminal organizations, but also subjects socialized into criminal groups through family, friendship, and community relations. It also includes, but it is not limited to, the processes of formal or ritual affiliation exhibited by some criminal organizations (which would unnecessarily restrict the scope of the review, were they adopted as operational definition). Conversely, this definition excludes individuals occasionally cooperating or co‐offending with members of organized criminal groups, as they lack stability over time.

2.3. The risk factors for recruitment into organized crime

For several years, the field of organized crime studies has remained at the margins of the most popular debates in criminology (Posick & Rocque, 2018). For example, the important dispute on the individual or social causes of criminal behavior has rarely touched on what causes people to join organized crime groups. Some of the most popular contributions to the debate make only a quick reference to criminal organizations, in some case contending that “there is no need for theories designed specifically to account for … organized crime” (Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990, p. 214).

At the same time, the literature on organized crime has disregarded the contributions of important theoretical and empirical discussions in the discipline. In general, however, organized crime studies relied on a few seminal studies arguing that the social environment plays a central role in the involvement of individuals in criminal organizations, with limited attention to individual characteristics (Albini, 1971; Block, 1980/1983; Ianni & Reuss‐Ianni, 1972). Furthermore, most studies have emphasized the role of the social environment at a meso‐level, contending that factors such as trust, social relations, kinship, and cultural/symbolic elements are crucial for the formation and persistence of criminal groups (Gambetta, 1993; Kleemans & Van de Bunt, 1999; Paoli, 2003). Possibly due to the lack of data, very rarely studies have directly addressed the factors leading to recruitment or involvement into organized crime at the individual level (Von Lampe, 2016). As a result, among earlier contributions, information on the processes that lead individuals to join organized criminal groups is largely dispersed.

Only in recent years a few studies have gained access to better information on individual members of organized crime groups. This enabled scholars to examine the factors influencing the recruitment into organized crime at the individual level. These recent developments in organized crime research have also enabled to reconnect with the broader theoretical debate, for example with the increasing attention on changes in offending patterns within individuals over time spurred by developmental and life‐course criminology (Farrington, 2003; Kleemans & De Poot, 2008).1 Availability of individual‐level, longitudinal data on organized crime offenders enabled to explore the factors that lead individuals to join delinquent groups and organized criminal groups within the society they belong to. Yet, in line with the prevalent focus of the field, studies mostly pointed at the role of the social environment (Kleemans & De Poot, 2008; Kleemans & Van de Bunt, 1999; Kleemans & Van Koppen, 2014; Morselli, 2009; Van Koppen et al., 2010). This study has gererally confirmed that social relations and social capital are important drivers of involvement into organized crime, and argued that inviduals join criminal groups due to the social opportunity structure, the social relations giving acces to criminally exploitable opportunities (Kleemans & De Poot, 2008). Furthermore, and possibly due to the impossibility to collect longitudinal socioeconomic and psychological data on such a specific population, studies emphasized the role of previous offending, deviance, violence and contact with the criminal justice system. Several researchers have addressed changes in offending patterns within individuals engaged in organized crime (Kleemans & De Poot, 2008; Morselli & Tremblay, 2004; Morselli, 2003; Van Koppen, de Poot, & Blokland, 2010; Van Koppen, de Poot, Kleemans, et al., 2010), while others have taken a closer look at risk factors for joining organized crime groups (Kleemans & De Poot, 2008; Kleemans & Van de Bunt, 1999; Kleemans & van Koppen, 2014; Klein & Maxson, 2006; Lyman & Potter, 2006). Few recent contributions have addressed the intergenerational transmission of delinquency and organized crime offending within families (Spapens & Moors, 2020; Van Dijk et al., Unpublished), whereas others have drawn attention on economic disadvantages (Carvalho & Soares, 2016; Lavezzi, 2008, 2014). Other studies have focused on the impact of joining organized crime groups or gangs on the life of individuals (Melde & Esbensen, 2011; Pyrooz, 2014; Pyrooz et al., 2016) or of leaving organized crime groups (Berger et al., 2017; Pyrooz et al., 2017; Sweeten et al., 2013).

2.4. How the risk factors may impact the recruitment into organized criminal groups

Given the scattered nature of research summarized above, there is a lack of an overarching theoretical framework on the individual‐level drivers of involvement into organized criminal groups. Criminological research has emphasized the social opportunity structure as well as the criminal skills and experiences. Yet these findings are far from providing a comprehensive theoretical framework of all possible factors that influence the recruitment into criminal organizations. For example, demographic, psychological, and economic factors may also drive the recruitment. In this regard, organized crime research remarkably differs from the study of youth gangs, where empirical and theoretical advancements have enabled the development of specific models (Decker et al., 2013; Higginson et al., 2018; Howell & Egley, 2005; Thornberry et al., 2003). The lack of theoretical framework suggests adopting a broad and flexible approach to this systematic review.

Focusing only on the main factor categories pointed out by recent research, social relations, and criminal background, may unnecessarily restrict the scope of this systematic review. Instead, this review focuses on all individual‐level factors presented in the literature, leaving to the included studies the establishment of the boundaries of the analysis. This option provides a comprehensive assessment of the factors identified by empirical research and, at the same time, enables comparison across different factors. Furthermore, it allows the necessary flexibility to encompass the multiple forms and types of organized crime groups, consistently with the broad definition presented above. Several systematic reviews in criminology followed a similar approach and a recent systematic review on the risk and protective factors for radicalization (Wolfowicz et al., 2020).

2.5. Why it is important to do the review

A better understanding of the factors associated with recruitment into organized criminal groups is needed to improve and consolidate the knowledge of organized crime, and to design empirically based prevention strategies. For this purpose, this systematic review aims at summarizing the existing empirical evidence about the relative strength of the risk factors related to recruitment into organized criminal groups. The theoretical debate on the definition of organized crime has often neglected empirical research. To the best of our knowledge, there are no systematic reviews with meta‐analysis on organized crime. Only recently a systematic narrative review on this topic examined 47 studies published until 2017 and pointed out the importance of social relations, criminal background, and criminal skills for the recruitment into organized crime (Calderoni et al., 2020; Comunale et al., 2020).

While only partially overlapping with organized crime literature, gang research has produced a few systematic reviews. Previous systematic reviews have focused on youth gang membership and interventions (Hodgkinson et al., 2009; Klein & Maxson, 2006; Raby & Jones, 2016). The Campbell Collaboration has published three systematic reviews on the involvement of young people in gangs (Fisher et al., 2008a, 2008b; Higginson et al., 2015), and more recently one on predictors of youth gang membership in low‐ and middle‐income countries (Higginson et al., 2018). Furthermore, two systematic reviews on the factors leading to radicalization and recruitment into terrorism have been recently published (Wolfowicz et al., 2020, 2021). While these reviews show the growing interest for the risk factors leading to involvement into groups engaged in criminal activities in a broad sense, they did not consider the factors relating to recruitment in organized crime.

A systematic approach on empirically based findings will provide a better understanding of organized crime. The findings of this review can contribute to clarifying the definitional debate around organized crime and push the field to further engage with empirical research by pointing out directions for future inquiry. Systematic analysis of the evidence regarding specific factors may show what mechanisms may drive individuals into organized criminal groups, point out similarities and differences with research on the general offending population and or other groups engaged in crimes (youth gangs, terrorist groups).

This review aims to inform not only researchers but also to support the formulation of effective evidence‐based intervention and prevention policies. By identifying the most important factors of pathways to organized crime membership, this review seeks to provide policy makers with detailed information on how to design potential intervention strategies. The importance of proper prevention policies against organized crime links to the fact that arrests only cause temporary drawbacks to the functioning of organized criminal groups. In fact, their resilience to law enforcement interventions is one of the most distinct features of organized criminal groups. This is due to organized criminal groups' ability to rapidly reorganize and to easily recruit new members. From an opportunity reduction perspective, intervention within the recruitment process could be an effective complementary strategy for combating organized crime. In this regard, the results of this systematic review may be used to inform about the most common risk factors for recruitment into organized crime, and hence to develop intervention strategies mitigating these factors. Finally, the findings may provide policy makers with more comparative insights about the dynamics of recruitment into various organized criminal groups. Shedding light on similarities in pathways into organized crime may help to formulate effective criminal justice policies applicable in various countries.

3. OBJECTIVES

This systematic review and meta‐analysis aim at providing a comprehensive overview of current empirical knowledge about the individual‐level risk factors related to recruitment into organized crime. This overarching aim can be subdivided into two main objectives:

Objective 1: Summarize the empirical evidence from quantitative, mixed methods, and qualitative studies on the individual‐level risk factors associated with the recruitment into organized crime.

Objective 2: Assess the relative strength of the risk factors from quantitative studies across different factor categories and subcategories and types of organized crime groups.

4. METHODS

This review is based on the previously published protocol (Calderoni et al., 2019). This section, except for specifically mentioned updates or changes, draws on the protocol.

4.1. Criteria for including and excluding studies

4.1.1. Study design

This systematic review aims to identify and evaluate existing knowledge of individual‐level risk factors relating to recruitment into organized crime. As recruitment into organized crime cannot be the object of experimental interventions, this review examines only empirical evidence resulting from studies using an observational research design.

This review includes studies having as one of the main objectives the analysis of recruitment into organized crime. Also, studies were included if they provided sufficient information and details on the analytical strategy, including sampling technique/data collection, and type of analysis conducted, intended as the relation between a risk factor and recruitment into organized crime. This review retrieved and screened quantitative, qualitative studies, and mixed methods studies, and excluded literature reviews, theoretical and conceptual contributions, and editorial pieces. This section describes in detail the search and screening process leading to the identification and inclusion of eligible studies.

For the synthesis of quantitative research, we relied on studies with variability in recruitment into organized crime, measuring and comparing at least two groups (e.g., organized crime members vs. non‐members). The review searched for studies based on longitudinal and cross‐sectional designs, though the study eligibility assessment resulted in including only cross‐sectional studies. We included in the meta‐analysis quantitative studies reporting at least an effect size or studies providing enough information to calculate an effect size from the reported statistics, as also described in the published protocol of this review (Calderoni et al., 2019). We included qualitative and mixed methods studies (for the qualitative analysis) that reported a clear aim of the research and provided appropriate information regarding the methodology and analytical strategy.

We did not exclude studies based on their geographical scope, year of publication, or quality. We evaluated the risk of bias in included quantitative studies using a risk‐of‐bias tool adapted from Higginson et al. (2018) and PROBAST tool for prediction studies (see Quality assessment of the included studies). We assessed the quality of qualitative and mixed methods studies using the CASP Qualitative Checklist (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2018).

4.1.2. Types of organized crime groups

The literature has long debated on the definition of organized crime and the characteristics of organized criminal groups. With the aim of favoring the inclusion of the largest number of eligible studies, we adopted the broad definition provided by Article 2 of the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (United Nations, 2000, p. 5):

“Organized criminal group” shall mean a structured group of three or more persons, existing for a period of time and acting in concert with the aim of committing one or more serious crimes or offences established in accordance with this Convention, to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit.

Under this definition, a variety of groups are described as organized criminal groups, including traditional mafias, drug trafficking organizations, and adult gangs. We excluded groups described as youth (street) gangs, prison gangs, and terrorist groups. The literature generally discriminates between youth street gangs and organized criminal groups (Decker & Pyrooz, 2014), with the latter having an important share of adult offenders adults involved in potentially more complex criminal activities aiming at profit. Furthermore, previous systematic reviews have already assessed the factors leading to youth gang membership (Higginson et al., 2018; Klein & Maxson, 2006; Raby & Jones, 2016). As for prison gangs, while some are extension of criminal organizations active outside the prison, others establish themselves and thrive in the isolation of the prison setting. Moreover, while there is a relevant literature on prison gangs, this field is mostly separate from the literature on organized crime, which emphasizes the social embeddedness into the legitimate world. For these reasons, we excluded prison gangs, as the recruitment of individuals in such groups occurs in confined settings and therefore is influenced by different contextual factors (Blevins et al., 2010; Wood et al., 2014). Lastly, we excluded terrorist groups due to their ideological/political motivation. In addition, two systematic reviews on the putative risk and protective factors relating to cognitive and behavioral radicalization were recently published (Wolfowicz et al., 2020, 2021).

4.1.3. Types of factors

This systematic review includes only studies measuring recruitment into organized criminal groups at the individual level. We did not limit the search of studies to specific factors, adopting a field‐wide approach to ensure a broad coverage of the available evidence. As a result, we identified several types of factors that can be nonetheless grouped into different categories: sociodemographic, economic, psychological, and criminal history factors.

For a variable to be considered as a risk factor, it must occur before the outcome (Murray et al., 2009). The risk factor therefore must precede recruitment into organized crime, and this would ideally require longitudinal designs for its measurement. However, some factors may be considered as preceding the recruitment even if included in cross‐sectional studies, as they do not vary over the life course (e.g., sex, ethnicity). For this reason, we considered as risk factors for organized crime membership not only predictors measured before organized crime membership but also time‐invariant factors estimated from cross‐sectional studies. We also considered self‐reported retrospective data assessing risk factors preceding the outcome, though they present some biases as they are based on individual's recall of past events (Murray et al., 2009). This choice was driven by the aim of including as many studies as possible and enhance the knowledge of individual‐level factors leading to recruitment into organized crime.

In line with previous systematic reviews (Higginson et al., 2018; Klein & Maxson, 2006), we classified as predictors the factors measuring conditions preceding the recruitment into organized criminal groups and as correlates the factors measuring conditions occurring simultaneously or after the recruitment. Effects and results of the meta‐analysis of predictors and correlates are reported separately (see Synthesis of results).

4.1.4. Types of outcome measures

The review included self‐ and peer‐reported measures, and practitioner‐ and police‐reported measures of individual organized crime membership. The outcome of interest in this systematic review is the recruitment into organized crime, measured with a dichotomous variable. We considered recruitment as a more general concept referring to the several processes leading individuals to the stable involvement into organized crime groups, without differentiating between different forms of recruitment. For this reason, we included studies focusing on recruitment, affiliation, and other forms of stable involvement. Lastly, we conducted moderator analyses by type of organized criminal group to assess the variation in effect sizes attributable to heterogeneity.

4.2. Search methods for identification of studies

4.2.1. Search terms

This review relied on a three‐fold query structure that ensured systematic, comprehensive, and efficient screening results. The queries incorporate all aspects that are relevant to the factors relating to the recruitment into different types of organized criminal groups. The search terms from each of the three main categories (organized crime groups, factors, and recruitment) combined formed the queries. The Boolean Operator “OR” connected keywords pertaining to the same category, while the Boolean Operator “AND” connected keywords from different categories (Figure 1). This query structure ensured to retrieve all the studies containing at least one term from each word category (see Table 11 in Supporting Information Appendix A: Search categories and related search terms).

Figure 1.

Query structure

4.2.2. Search locations and languages

The search for eligible studies relied on 12 databases relating to different research disciplines—including social, psychological, and economic research—reflecting the transdisciplinary approach of this systematic review.2 The search strategy included published or unpublished studies in English, French, German, Italian, and Spanish.3 We applied no limitations as to their year of publication or geographic origin. Table 1 reports the list of databases by language of the search and search technique. When available, the preferred technique was to search title, abstract and keywords.

Table 1.

List of databases and search techniques

| Language | Database | Sub‐database | Search technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| English | EBSCO | Criminal Justice Abstracts | Abstract |

| Open Grey | Full‐text | ||

| ProQuest | Social Sciences Premium | Abstract | |

| NJCRS | |||

| APA PsycInfo | |||

| ABI/INFORM Collection | |||

| International Bibliography of the Social Sciences | |||

| Public Health Database | |||

| Military Database | |||

| EconLit | |||

| APA PsycArticles | |||

| PubMed | Title and Abstract | ||

| Scopus | Title, Abstract & Keyword | ||

| Web of Science | Science Citation Index Expanded | Title | |

| Social Sciences Citation Index | |||

| Arts & Humanities Citation Index | |||

| Conference Proceedings Citation Index—Science | |||

| Conference Proceedings Citation Index—Social Sciences and Humanities | |||

| Book Citation Index—Science | |||

| Book Citation Index—Social Sciences & Humanities | |||

| Emerging Sources Citation Index | |||

| French | Google Scholar | Full‐text | |

| Sudoc.Abes | Title | ||

| German | Sowiport | Title | |

| Italian | Riviste Web | Full‐text | |

| Spanish | Liliacs | Title, Abstract & Subject | |

| ProQuest | Latin America & Iberia Database | Full‐text |

The initial search was conducted between January and March 2017. An updated search was performed between September and October 2019.

We attended two meetings with a librarian to validate the search terms and queries and ensure the inclusion of all databases relevant to this systematic review (see Table 11 in Supporting Information Appendix A: Search categories and related search terms).

4.2.3. Multistage approach to searching

We identified potentially eligible studies not only through scientific database searching but also through contact with experts in the field of organized crime. The initial list of experts to be contacted was further expanded including the authors of the studies deemed eligible after the full text screening.4 Lastly, we identified relevant literature from the bibliographies of the potentially eligible studies retrieved for full‐text screening and we included such studies in the full‐text screening.

4.3. Data collection and analysis

4.3.1. Selection of studies

The review process incorporated all the studies retrieved through database search, references search, and experts' contribution. Metadata for each study were imported into the Covidence online platform that provides an environment to manage and conduct systematic reviews.5

After the removal of duplicate entries, the research team underwent training sessions for the screening of potentially eligible studies. The trainings provided researchers with background information on the aim of the systematic review as well as with briefings on how to implement the search strategy and screening of studies. A preliminary screening phase was performed, with each reviewer independently conducting the title and abstract screening of a set of 100 studies. The results were then compared among all researchers and disagreements were discussed to reach common criteria for screening and including eligible studies. To ensure reliability throughout the screening process, two reviewers screened each document. A third researcher settled divergent screening decisions, in consultation with the full review team where necessary.6

First, the research team performed title and abstract screening to retain only studies investigating recruitment into organized criminal groups as one of the main aims of the study. When the information reported in the title and abstract was not sufficient to include or exclude the document, we retained the study for full‐text screening.

Second, the research team performed full‐text screening of all potentially eligible studies retained.7 To be included, each document had to meet all the eligibility criteria listed in the “Eligibility screening form” (see Table 12 in Supporting Information Appendix B: Eligibility screening form). If none of the eligibility criteria could be definitively answered, the study was filtered out. While in the previous phase we favored inclusivity, in this phase every criterion needed to be conclusively met, on penalty of study exclusion.

4.3.2. Data extraction and management

The quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies that met all full‐text screening criteria were independently coded by two reviewers based on a detailed coding guide (see Supporting Information Appendix C: Document coding protocol). We initially planned to code mixed methods studies twice, one entry for the quantitative section and one entry for the qualitative one. However, the full‐text screening resulted in limiting their inclusion to the set of eligible qualitative studies, as the quantitative parts of the mixed‐methods studies did not meet the last item of the “Eligibility screening form,” that is, variability in the outcome measure (see Table 12 in Supporting Information Appendix B: Eligibility screening form). As for the previous screening steps, the results of the reviewers were compared, and any coding conflict was resolved through exchanges with the review manager.

4.3.3. Quality assessment of the included studies

We assessed the risk of study bias for quantitative studies through a section of the coding protocol (questions 58–85 in Table 14 in Supporting Information Appendix C: Document coding protocol). The quality of each study was assessed by two authors. The review manager evaluated the two assessments and promoted a consensus decision for discrepancies. The items in the coding protocol allowed the investigation of a variety of potential issues related to sample selection, risk factors and outcome definition and application and statistical modeling, including diagnostic measures on the statistical models. The protocol allowed to analytically reach an overall risk‐of‐bias rating for each included quantitative study. The quality assessment is largely an adaptation of Higginson and colleagues' systematic review (Higginson et al., 2018) and of PROBAST risk‐of‐bias tool for prediction models (PROBAST, 2018, p. 8). Overall, the risk of bias judgment is as follows:

Low risk of bias: If all domains were rated low risk of bias.

High risk of bias: If at least one domain is judged to be at high risk of bias.

Unclear risk of bias: If an unclear risk of bias was noted in at least one domain and it was low risk for all other domains.

In line with previous meta‐analysis protocols, we did not exclude low‐quality studies (see Higginson et al., 2018) and we opted for the “traffic light” model adopted by de Vibe et al. (2012) to present the results.

For the included qualitative studies and the qualitative parts of mixed‐method studies the quality assessment relied on an adaptation of the CASP Qualitative Checklist (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2018). Of the original 10‐item checklist we retained the following five items (items 98–102 in Table 15 in Supporting Information Appendix C: Document coding protocol:

Clear aim on recruitment: the qualitative study main aim must be on the recruitment into organized crime, or the topic must be addressed in a relevant part of the study (chapter, section, subsection).

Research design appropriate: the study must clearly indicate the research design adopted to investigate the recruitment into organized criminal groups or the research design must be the same for all the objectives of the study, including the recruitment.

Data collection appropriate: the study must clearly state the sources of information to investigate the recruitment into organized crime, and/or the sources must be the same for the rest of the study. The study must offer indications on how the information was collected, verified, and analyzed.

Data analysis rigorous: the study must provide an in‐depth description of the analysis, of the construction of categories and themes, present sufficient data.

Clear statement of findings: the study must clearly present the findings, discuss them in relation to limitations and other contributions.

Also for the quality assessment of qualitative studies we did not exclude low‐quality studies. We presented the results of the assessment adapting the “traffic light” model to the five items.

4.3.4. Effect size metric and calculations

To perform the meta‐analyses, we transformed different statistical measures reported in eligible quantitative studies into comparable effect size measures. When effect sizes were not directly reported in the studies, we calculated them based on the reported and extrapolated statistics. When studies did not report enough information to calculate effect sizes, we contacted the authors to obtain the necessary data (see below, Missing data). We extracted effect sizes and relevant statistics following a detailed coding guide throughout the process (see items 35–57 in Supporting Information Appendix C: Document coding protocol).

We coded all effect sizes extracted from the included quantitative studies based on several dimensions relevant for synthesis and interpretation, including: the document of origin, the nature of the two (or more) groups the effect was assessed on (e.g. organized crime members for the organized crime group and offenders in general for the non‐organized‐crime group), and the risk factor each effect size referred to (items 1–4, 18–19, and 35 of Supporting Information Appendix C: Document coding protocol, respectively). We carried out the statistical synthesis for all the comparable effect sizes between similar pairs of groups. We classified effect sized based on their focus domain (sociodemographic, economic, psychological, criminal history) (see item 36 in Supporting Information Appendix C: Document coding protocol). However, we opted to present the results based on a list of categories and subcategories that were inductively identified from the data (see items 36a and 36b in Supporting Information Appendix C: Document coding protocol).

We calculated effect sizes using two categories of statistics: group means, for continuous variables, and risk‐based association measures between two binary variables. The quantitative studies included in this review reported their results using mainly group mean differences and standard deviations for continuous variables, and contingency tables or odds ratios for binary variables. Such type of data was transformed into effect sizes in the form of log odds ratios to perform the meta‐analysis.

The logic of using log odds ratios as a common statistic is twofold. First, both odds ratios and log odds ratios are symmetrical across the two variables they reference. Second, log odds ratios have the property of symmetry around their null value. While odds ratios are defined between 0 and positive infinity with a null value of 1 and asymmetrical standard errors, log odds ratios “normalize” the null value to 0 and are defined between negative infinity and positive infinity, with symmetrical standard errors regardless of sign (see Borenstein et al., 2009, p. 35).

Log odds ratios, however, are difficult to interpret. To assist the reader in interpreting our results, in the Discussion section we converted the average log odds ratios into odds ratios.

The conversion to log odds ratios entails, respectively:

-

1.

For continuous variables for which group means and variance are reported, calculating first Cohen's d and d's standard error (Borenstein et al., 2009, p. 21). These measures will then be used to calculate the log odds ratio and the standard error (Borenstein et al., 2009, p. 47).

-

2.

For binary variables for which contingency tables or odds ratios are reported, calculating log odds ratio and standard error (Borenstein et al., 2009, p. 33).

4.3.5. Determining independent findings

Some included studies relied on the same data to investigate different issues. In some cases, however, they reported the same factors. To avoid issues of lack of independence among the estimated effect sizes, we paired six studies employing the same data before the inclusion of the effect sizes in the meta‐analysis. The resulting pairs are: Francis et al. (2013)/Kirby et al. (2016), Decker et al. (2014)/Pyrooz et al. (2015), and Coid et al. (2013)/Wood et al. (2017). The first pair did not pose any issue, since the two studies always reported the same values for the same factors. We thus ensured that the extracted measures were included only once. The other two pairs reported slightly different values, possibly due to few observations being dropped from the analyses for various, unspecified reasons. Nonetheless, the estimated effect sizes were always similar. We thus opted to include the effect sizes from the study reporting the largest samples within each pair.

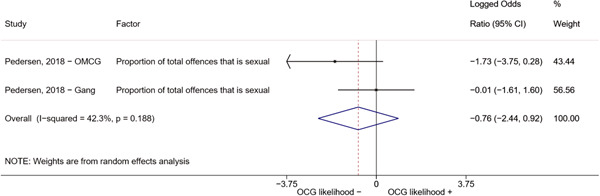

Second, one study (Pedersen, 2018) reported estimates for two different types of organized criminal groups: outlaw motorcycle gang members (OMCG) and adult gang members. We therefore split the effect sizes extracted from Pedersen (2018) as if they were extracted from two different studies. We reported these effect sizes separately, by labeling them as “Pedersen, 2018—OMCG” and “Pedersen, 2018—Gang.”

Third, several included studies reported different effect sizes falling within the same factor category or subcategory. For example, several studies reported effect sizes comparing organized criminal groups with more than one non‐organized‐crime group type (e.g., offenders in general, violent men). In addition, multiple effect sizes measured the same construct (e.g., several reported measures of violence). This required to combine such measures into one synthetic effect size before inclusion in the analysis (see below, Data synthesis).

4.3.6. Assessment of publication bias

We planned to test publication bias through funnel plots, a specialized form of scatter plots used in meta‐analysis to visually identify publication and other bias (Sterne et al., 2006) and adjust for publication bias with trim and fill analysis following the methodology suggested by Rothstein et al. (2005). However, due to the low number of independent effect sizes included in the meta‐analysis, it was not possible to conduct these tests. Moreover, all included studies were published studies. For these reasons, we acknowledge that the results may be affected by publication bias.

4.3.7. Missing data

One eligible study (Danner & Silverman, 1986) included insufficient data to determine any effect size except one. Another study (Sharpe, 2002) provided only partial information, allowing the computation of only some effect sizes. We could not retrieve the email contacts of the authors of these two studies.

Other eligible studies provided incomplete data for few measures or variables (e.g., reporting only average values without standard deviations). We contacted the authors asking for additional information. We received feedback from several contacted authors, who provided sufficient information to integrate the data from the included studies (Adams & Pizarro, 2014; Carvalho & Soares, 2016; Francis et al., 2013; Kirby et al., 2016; Klement, 2016). For one study, the authors were unable to provide the requested information (Van Koppen et al., 2010). An integration request is still pending for one study (Blokland et al., 2019).

4.3.8. Data synthesis

Whenever included studies reported multiple effect sizes falling within the same factor category or subcategory, we synthesized effect sizes adopting the following procedure:

-

1.

We grouped effect sizes by study, factor category (and subcategory where applicable), and factor type (predictor or correlate).

-

2.

Some studies also reported the same measures for multiple non‐organized‐crime groups (i.e., comparison group, see below Characteristics of included studies for further details). In such cases, in line with the literature on subgroup analysis (see Borenstein et al., 2009, pp. 149–186), we first synthesized effect sizes of the same study by comparison group, then the synthetic measures were subsequently synthesized to obtain a synthetic effect size for each study. Within‐study effect sizes were computed using the Stata robumeta command which allows to estimate robust variance in meta‐regression with dependent effect sizes estimates (the analyses used random‐effects models).8

-

3.

Whenever possible, we included the synthetic effect sizes in random‐effects meta‐analyses using the Stata meta command (StataCorp, 2019). Alternatively, we just reported the synthetic effect sizes (e.g., when no other studies reported on the same measures).

We conducted a random‐effects meta‐analysis using inverse variance weighting when at least two included studies provided predictors or correlates falling within the same factor category and measuring conceptually similar factors. In this way, we calculated the overall weighted mean effect estimate of each separate factor on organized crime recruitment. We carried out meta‐analysis using log odds ratios and we presented the results in a forest plot with 95% confidence intervals. We presented results of meta‐analyses of predictors separately to results of meta‐analyses of correlates. For each type of factors, we performed a meta‐analysis on different factors, including sociodemographic, economic, psychological, and criminal history factors. We initially planned to conduct meta‐analyses including only effect sizes that measured not only the same factor, but also the same pair of organized crime versus non‐organized‐crime group (e.g., organized crime members vs. offenders in general) (see published protocol, Calderoni et al., 2019). However, this sublevel of analysis would have limited the number of meta‐analyses due to the low number of effect sizes retrieved from included quantitative studies. For this reason, differing from the protocol, we conducted meta‐analyses only by type of effect size (predictor, correlate) and type of factor category or subcategory. Nonetheless, we conducted moderator analyses by type of organized criminal group to further investigate statistically significant heterogeneity displayed by the results of meta‐analyses (see below Sensitivity and subgroup analysis and Supporting Information Appendix E: Moderator analyses by type of organized criminal group).

4.3.9. Assessment and investigation of heterogeneity

The study of heterogeneity can provide indications on how to interpret the overall effect size of each meta‐analysis (Borenstein et al., 2009). We assessed heterogeneity between studies with the I 2 and τ 2 (Borenstein et al., 2009). Given the diversity of the groups classified as organized crime across time and countries and the controversies surrounding the definition of organized crime (as discussed above in Background), we performed subgroup meta‐analyses moderating studies by type of organized criminal group for all meta‐analyses showing statistically significant heterogeneity. We included forest plots displaying an inverse‐variance weighted random‐effect meta‐analysis of the effect of factor category on involvement into organized criminal groups (see Supporting Information Appendix E: Moderator analyses by type of organized criminal group). Results of moderator analyses should be interpreted with caution, as the number of effect sizes for each moderator category is limited and the inclusion of additional studies may alter the results.

4.3.10. Sensitivity and subgroup analysis

We initially planned to conduct subgroup analyses to further investigate the effect of risk of bias, geographic scope as well as the effect of study heterogeneity. However, due to the low number of included studies in each meta‐analysis, we did not conduct sensitivity analyses of risk of bias and of geographic scope. We assessed the heterogeneity through subgroup meta‐analyses moderating studies by type of organized criminal group, using Stata 16 meta command (StataCorp, 2019). Results of the moderator analyses, analogous to the analysis of variance (ANOVA), are presented in a separate subsection at the end of the Results section, and integrally reported in Supporting Information Appendix E: Moderator analyses by type of organized criminal group.

4.3.11. Treatment of qualitative research

Systematic reviews have generally excluded qualitative studies because of the impossibility of using their findings to draw conclusions. Nonetheless, Campbell policies and guidelines have recently encouraged the inclusion of qualitative and descriptive research, which can provide a more comprehensive overview of the object of study. In addition, both anonymous reviewers of the protocol stressed the importance of including relevant qualitative works to achieve the objectives of this review. For these reasons, this systematic review includes quantitative studies as well as qualitative studies.

We systematically retrieved and screened qualitative studies for their inclusion, coding them using part of the coding document also used for the quantitative literature. We assessed the quality of the included studies through a 5‐item list adapted from the CASP Qualitative Checklist (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2018). The included studies were used to inform, contextualize, and expand the knowledge resulting from the evidence and findings of the quantitative studies.

5. RESULTS

5.1. Description of studies

5.1.1. Results of the search

The search led to the collection of 51,564 records that were subsequently screened for assessing their eligibility for this systematic review (Figure 2). A team of trained researchers applied common criteria in screening the title and abstract of each study. We considered as relevant for the scope of the review studies focusing on and/or reporting about individual‐level factors for recruitment into organized criminal groups and making an original research contribution. We therefore excluded news articles, theoretical contributions, or reviews of any type.9

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram of search and screening process

From the initial number of records, 1929 documents consisted of duplicates and therefore were excluded. A total of 49,547 records were considered irrelevant and largely off‐topic as they did not meet the inclusion criteria for title and abstract screening. We thus retained 86 remaining studies. Experts' contribution and references search led to the identification of 116 additional studies, reaching a total of 202 studies potentially eligible for full‐text screening. Of these, we failed to retrieve six studies as the full text was unavailable. The full‐text screening, based on six items (with the sixth item applied only to quantitative studies), allowed to exclude 144 studies that did not meet one or more of criteria, resulting in 52 studies deemed eligible for inclusion.

5.1.2. Included studies

The search and screening process led to the inclusion of 52 studies adopting a quantitative (19), qualitative (28), or mixed methods approach (5) (Figure 2). The 19 quantitative studies were included in the meta‐analyses while the qualitative information provided by the 28 qualitative and 6 mixed methods studies was coded as relevant factor categories on recruitment into organized crime. We categorized the included studies through a detailed document coding protocol classifying their characteristics based on several items (Supporting Information Appendix C: Document coding protocol).

5.1.3. Excluded studies

Full‐text screening allowed to exclude 144 studies that did not meet any of the six inclusion criteria. The studies were deemed ineligible because they did not report on organized criminal groups as defined for this review (i.e., out of scope studies, n = 75), recruitment into organized criminal groups not main objective of the study (n = 36), nonempirical contribution (n = 16), no well‐defined/single factors (n = 2), nonindividual factors (n = 3), lack of comparison group (n = 12) (Figure 2). A table with the full reference of the excluded studies as well as the reasons for exclusion is reported below in References to excluded studies.

5.2. Characteristics of included studies

5.2.1. Quantitative studies

The 19 included quantitative studies are summarized below and in Table 2. The full references are provided in References to included studies.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included quantitative studies

| Study | Study objectives | Country | Type of OCG | Type of comparison group | Methods of data collection and sample | Data analysis | Risk factors (by category) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adams and Pizarro (2014) | Examine the arrest histories of homicide gang and non‐gang offenders to assess patterns of offense specialization, escalation, or de‐escalation. | US | Gang | Serious offenders | Police intelligence data | The authors use multinomial models to calculate the predicted probability of a particular offense type being committed at each arrest, with specifications for gang members and non‐gang members. Differences in age, number of arrests and ethnicity for gang and non‐gang members are reported, but only data about ethnicity allow effect size calculation. | Age; Ethnicity; Offence and/or contact with CJ system |

| Data is retrieved from homicide investigation files compiled by the Newark Police Department's Homicide Unit from 1999 to 2005. The sample includes 140 homicide offenders that had at least five arrests before the homicide (81 non‐gang members and 59 gang members). | |||||||

| Blokland et al. (2019) | Examine various dimensions of the criminal careers of outlaw bikers, including participation, onset, frequency, and crime mix. | The Netherlands | Biker gang | Offenders in general; Population sample | Police intelligence data | The authors report the means and standard deviations between OMCG members and non‐OMCG members across personal and criminal careers characteristics. T‐tests and Chi2/Fisher Exact tests significance are also reported. They also perform logistic regressions to predict OMCG membership. | Foreign born; Low self‐control; Offence and/or contact with CJ system; Sanctions; Violence |

| Data is retrieved from the outlaw motorcycle gangs intelligence unit of the Central Criminal Investigations Division of the Netherlands National Police (OMCG members), and from the Dutch National Vehicle and Driving Licence Registration Authority database “light vehicles” (non‐OMCG members). The criminal careers of OMCG members and the comparison group of motorcycle owners are constructed using extracts from the Judicial Information System. The sample includes 601 OMCG members, and 300 non‐OMCG members. | |||||||

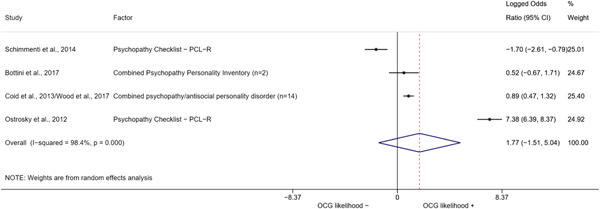

| Bottini et al. (2017) | Examine which psychological and neuropsychological variables better discriminates differences between the groups of OC prisoners, non‐OC prisoners, and non‐prisoners controls. | Italy | Mafia | Offenders in general; Population sample | Survey (interviews) + professional testing | The authors report mean scores and standard deviations for several variables across the three groups. They test the statistical significance of the differences among groups through different tests. They also perform discriminant analyses between OC and non‐OC prisoners, although results are reported summarily | Age; Anxiety; Cognitive functioning; Depression; Education; Low self‐control; Negative life events; Psychopathy and antisocial personality disorder; Sanctions |

| Data is retrieved thanks to the performance of neuropsychological interviews, psychological assessments, and neuropsychological tests. The sample includes 150 male individuals (50 OC prisoners, 50 non‐OC prisoners, and a control group of 50 non‐prisoners). OC and non‐OC prisoners comprised 25 violent and 25 nonviolent individuals per group. The non‐prisoner control group was matched in age, years of education with the prisoner groups. | |||||||

| Carvalho and Soares (2016) | Characterize drug‐trafficking jobs and study the selection into gangs, analyzing what distinguishes gang‐members from other youth living in favelas. | Brazil | Drug trafficking organization | Population sample | Survey (interviews) | The authors propose equations to estimate gang membership, and earnings for the illegal sector. In addition, key characteristics of interviewees related to ethnicity, religion, marital status, age, education, and labor market status are compared to data from the Brazilian Census of males aged 10–25 living in Rio's favelas; only some of these variables allow effect size calculation. | Age; Being in a relationship; Economic condition; Education; Ethnicity; Living conditions/household (adulthood); Religious beliefs; Troubled family environment |

| Data is retrieved from interviews collected by the Brazilian NGO Observatório de Favelas (OF) on individuals working for the drug‐trafficking business in favelas of Rio de Janeiro. The sample includes 230 individuals (98% males) aged 11–24 who were members of different drug‐trafficking gangs. | |||||||

| Coid et al. (2013) | Investigate associations between gang membership, violent behavior, psychiatric morbidity, and use of mental health services. | UK | Gang | Population sample; Violent men | Survey (questionnaires) | The authors use logistic regressions to compare the demographic characteristics of non‐violent men, violent men, and gang members. Linear trends are established by entering group membership as an ordinal variable. Finally, associations between gang membership, violence, and psychopathology or service use are investigated. | Age; Anxiety; Being in a relationship; Depression; Economic condition; Ethnicity; Foreign born; Low self‐control; Negative life events; Psychopathy and antisocial personality disorder; Violence |

| Data is retrieved from a cross‐sectional survey using random location sampling in Great Britain. The survey gathers information about gang membership, violence, use of mental health services, and psychiatric diagnoses. The sample includes 4,664 men aged 18–34, and men from areas with high levels of violence and gang activities are oversampled. | |||||||

| Danner and Silverman (1986) | Examine the extent to which there is a distinct configuration of demographic, offense history, and attitude characteristics among bikers and non‐biker inmates. | US | Biker gang | Offenders in general | Survey (questionnaires) | The authors perform a discriminant analysis to discover differences between the biker and non‐biker groups regarding their demographic characteristics, offense history, and attitude/value orientations. However, only data about ethnicity allow effect size calculation. | Ethnicity |

| Data is retrieved from a survey about demographic characteristics and criminal history administrated to bikers and non‐bikers incarcerated in adult correctional institutions in the United States. The sample includes 168 individuals (63 bikers and 105 non‐bikers). | |||||||

| Decker et al. (2014) | Validate self‐nomination in gang research. | Survey (interviews) | |||||

| Investigate differences in gang embeddedness across current gang members, former gang members, and those individuals who have never joined a gang. | US | Gang | Population sample | Data is retrieved from interviews conducted with individuals in 5 US cities in settings chosen to include many individuals with involvement in gangs and criminal behavior. The sample includes 621 respondents (188 current gang members, 264 former gang members, and 169 non‐members). | The authors assess the unadjusted differences between non‐, former, and current gang members across the study variables, focusing on the magnitude and statistical significance of differences. Then, standardized differences in a mixed graded response model of gang embeddedness are evaluated across the three statuses of gang membership to assess the validity of self‐nominated gang membership. | Age; Criminal versatility; Education; Ethnicity; Low self‐control; Motivation; Sex; Social environment; Troubled family environment; Violence | |

| Francis et al. (2013) | Examine the criminal histories of offenders who become involved in organized crime by analyzing administrative data on criminal sanctions. | UK | Other organized crime group | Offenders in general; Serious offenders | Judicial/official data | The authors compare the demographics of organized crime offenders and the nature of the inclusion offences to the characteristics of offenders in the comparison groups. The onset of organized offenders' criminal career, the volume of offences before being convicted of organized crime, the specialization within their criminal career, the offending profile, and the escalation of offence seriousness are also investigated. | Age; Criminal versatility; Ethnicity; Foreign born; Offence and/or contact with CJ system; Sex |

| Data is retrieved from the Police National Computer (PNC), which includes information on sanctioned offenders in the UK in 2007–2010. The sample includes 4109 offenders convicted for offences linked to organized crime, and two comparison groups (4090 general crime offenders, and 4109 serious crime offenders). | |||||||

| Kirby et al. (2016) | Explore the feasibility of identifying a greater number of organized crime offenders, currently captured but invisible, within existing national general crime databases. | UK | Other organized crime group | Offenders in general; Serious offenders | Judicial/official data | The authors identify demographics and offending behavior of organized crime offenders, the spatial distribution of organized crime offenders, and they establish whether it is possible to distinguish organized crime offenders from control groups. Gender, age, nationality, ethnicity, and inclusion offence are tested using Chi2 tests. To examine differences between means, the distributional assumption of normality is tested using quantile‐quantile plots and using the Kruskal‐Wallis test if non‐normality is found, and a one‐way ANOVA otherwise. | Age; Criminal versatility; Ethnicity; Foreign born; Offence and/or contact with CJ system; Sex |

| Data is retrieved from the Police National Computer (PNC), containing information on sanctioned offenders in the UK in 2007–2010. The sample includes 4109 offenders convicted for an offence linked to organized crime, and two comparison groups (4090 general crime offenders, and 4109 serious crime offenders). | |||||||

| Kissner and Pyrooz (2009) | Assess the relative independent effects on gang membership of differential association and self‐control measures in terms of both strength and significance. | US | Gang | Population sample | Survey (interviews) | The authors provide descriptive statistics to assess if current gang members are distinguishable from the two control groups. Pearson χ 2 tests are run for nominal level variables to examine significance between the three groups; independent sample t tests are run to examine significance for all other variables. Logistic regressions are executed to evaluate the effect of self‐control on former and current gang membership. | Age; Economic condition; Ethnicity; Low self‐control; Sex; Social environment; Troubled family environment |

| Data is retrieved from face‐to‐face interviews to a random cluster sample of inmates located in a large California city. The sample includes 200 inmates that self‐nominated themselves as non‐gang members (n = 136), former gang members (n = 27), and current gang members (n = 33). | |||||||

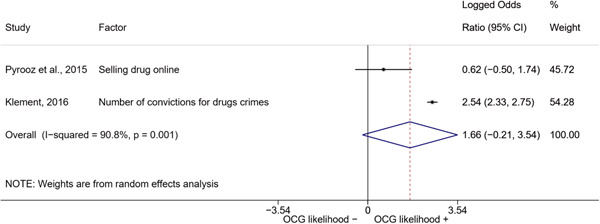

| Klement (2016) | Investigate the effect of being an outlaw biker on criminal involvement in Denmark. | Denmark | Biker gang | Offenders in general | Police intelligence data | The authors estimate 46 unstandardized difference‐in‐difference regressions to assess the effect of an affiliation with an outlaw motorcycle club on criminal involvement. | Economic condition; Education; Offence and/or contact with CJ system; Offence type; Sanctions; Violence |

| Data is retrieved from the Danish National Police that provides information on a list of 1146 individuals suspected of involvement in organized crime and from Statistics Denmark that provides extensive information on individuals in a depersonalized anonymous format. The final sample includes 297 outlaw bikers that are matched on various background characteristics with 181,931 control individuals. | |||||||

| Levitt and Venkatesh (2001) | Reconstruct the economic and social histories of a group of young males who spent their adolescence in the early 1990s in a neighborhood economically marginalized and heavily influenced by gangs and drugs. | US | Gang | Population sample | Survey (interviews) | The authors document the labor‐market experiences of individuals included in the sample. Overall means and standard deviations, and the breakdown by gang status, for background characteristics are presented. OLS regressions are employed to assess the relationship between background characteristics of individuals, gang involvement and educational attainment. | Age; Economic condition; Education; Living conditions/household (adulthood); Troubled family environment |

| Data is retrieved from a structured survey administered orally to a group of young men who came of age in early ‘90 s and that, at the peak of the crack epidemic, used to live in Chicago in a neighborhood heavily influenced by gangs and drugs. The sample includes 29 gang members and 61 non‐gang members. | |||||||

| Ostrosky et al. (2012) | Describe a sample of incarcerated serious offenders who participated in Mexican drug gangs, in relation to Psychopathy Checklist, Revised (PCL‐R) scores and an array of cognitive neuropsychology assessments of prefrontal functioning. | Mexico | Drug trafficking organization | Population sample | Survey (interviews) + professional testing | The authors provide a descriptive characterization of the sample by mean and range. To assess differences between groups in all measures, Bonferroni post‐hoc correction tests are performed. | Age; Cognitive functioning; Education; Psychopathy and antisocial personality disorder |

| Data related to the psychological assessment is retrieved from semi‐structured interviews, review of files provided by the prison authorities, and the Psychopathy Checklist, Revised (PCL‐R). Data related to the neuropsychological assessment is retrieved from the Executive Functions Battery (BANFE). The sample includes 82 inmates pertaining to different hierarchical levels in criminal organizations related to drug production, trafficking, and marketing and with absence of any psychiatric, medical, or neurological disorder, and a control group of 76 healthy male volunteers with no history of convictions, arrests, or use of drugs. | |||||||

| Pedersen (2018) | Examine crime specialization and crime seriousness before gang initiation among adult gang members, outlaw bikers and matched comparison groups of offenders. | Denmark | Biker gang; Gang | Offenders in general | Police intelligence data | The author computes the diversity index and the forward specialization coefficient to examine the quantity of each offence type among individuals and the degree of specialization over time. Differences in the offence committed and criminal versatility among groups are also reported, allowing effect size calculation. | Criminal versatility; Offence type; Violence |

| Data is retrieved from Statistics Denmark and the Police Intelligence Database and it provides information on criminal records of gang members, outlaw bikers and offenders who stay out of such gangs. The sample includes 564 gang members with a matching group of 1608 non‐gang offenders, and 800 outlaw bikers with a matching group of 2390 non‐biker offenders. | |||||||

| Pyrooz et al. (2015) | Explore the prevalence of Internet usage among gang and non‐gang youth and young adults. Explore whether gang members have a higher propensity to engage in criminal and deviant activities online than their non‐gang peers. | US | Gang | Population sample | Survey (interviews) | The authors present univariate and bivariate statistics establishing the nature and patterns of online activities among groups. Then, multi‐level logistic IRT modeling is used to relate gang membership status to crime and deviance online. | Age; Criminal versatility; Education; Ethnicity; Foreign born; Internet use and technological capacity; Low self‐control; Motivation; Offence type; Sex; Social environment; Troubled family environment; Violence; Motivation |

| Data is retrieved from face‐to‐face interviews about the use of the Internet and involvement in gangs conducted with youth and young adults in five US cities. The sample includes 585 respondents (174 self‐nominated current gang members, 244 self‐nominated former gang members, and 167 self‐nominated non‐gang members). | |||||||

| Schimmenti et al. (2014) | Examine the levels of psychopathic traits among Mafia members who have been convicted of a criminal offence. | Italy | Mafia | Offenders in general | Survey (interviews) | The authors compute descriptive statistics for sociodemographic and psychopathic trait variables. Student's t‐test and Pearson's Chi2 tests are performed to assess differences between Mafia members and other inmates. A stepwise logistic regression based on Wald statistic is undertaken to examine the associations between psychopathic traits, sociodemographic variables, and the classification of participants into groups. | Age; Being in a relationship; Education; Low self‐control; Psychopathy and antisocial personality disorder; Sanctions |

| Data is retrieved from a semi‐structured interview administrating the Psychopathy Checklist‐Revised (PCL‐R) and from prison files review. The sample includes 30 men convicted of Mafia‐related and 39 of non‐Mafia‐related crimes convicted in the Pagliarelli prison in Palermo. | |||||||

| Sharpe (2002) | Apply the epidemiology model or risk factor approach to determine the level of association of risk factors to gang membership. | US | Gang | Offenders in general | Survey (questionnaires) | The author computes logistic regressions and t‐test analysis to determine the nature of the relationship between the identified risk factors and gang membership. Odds ratio analysis is also performed to determine the relative risk an individual faced if exposed to certain factors. | Economic condition; Ethnicity; Negative life events; Offence and/or contact with CJ system; Religious beliefs; Sex; Troubled family environment |

| Data is retrieved from a survey focused on all aspects of gang life administrated to a convenience sample of inmates incarcerated in North Carolina. The sample includes 396 self‐identified gang members and a control group of 390 self‐identified non‐gang members. | |||||||