Visual Abstract

Keywords: 18F-fluciclovine, PET/CT, prostate cancer, radiotherapy, management change

Abstract

Imaging with novel PET radiotracers has significantly influenced radiotherapy decision making and radiation planning in patients with recurrent prostate cancer (PCa). The purpose of this analysis was to report the final results for management decision changes based on 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT findings and determine whether the decision change trend remained after completion of accrual. Methods: Patients with detectable prostate-specific antigen (PSA) after prostatectomy were randomized to undergo either conventional imaging (CI) only (arm A) or CI plus 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT (arm B) before radiotherapy. In arm B, positivity rates on CI and 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT for detection of recurrent PCa were determined. Final decisions on whether to offer radiotherapy and whether to include only the prostate bed or also the pelvis in the radiotherapy field were based on 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT findings. Radiotherapy decisions before and after 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT were compared. The statistical significance of decision changes was determined using the Clopper–Pearson (exact) binomial method. Prognostic factors were compared between patients with and without decision changes. Results: All 165 patients enrolled in the study had standard-of-care CI and were initially planned to receive radiotherapy. Sixty-three of 79 (79.7%) patients (median PSA, 0.33 ng/mL) who underwent 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT (arm B) had positive findings. 18F-Fluciclovine PET/CT had a significantly higher positivity rate than CI did for the whole body (79.7% vs. 13.9%; P < 0.001), prostate bed (69.6% vs. 5.1%; P < 0.001), and pelvic lymph nodes (38.0% vs. 10.1%; P < 0.001). Twenty-eight of 79 (35.4%) patients had the overall radiotherapy decision changed after 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT; in 4 of 79 (5.1%), the decision to use radiotherapy was withdrawn because of extrapelvic disease detected on 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT. In 24 of 75 (32.0%) patients with a final decision to undergo radiotherapy, the radiotherapy field was changed. Changes in overall radiotherapy decisions and radiotherapy fields were statistically significant (P < 0.001). Overall, the mean PSA at PET was significantly different between patients with and without radiotherapy decision changes (P = 0.033). Conclusion: 18F-Fluciclovine PET/CT significantly altered salvage radiotherapy decisions in patients with recurrent PCa after prostatectomy. Further analysis to determine the impact of 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT guidance on clinical outcomes after radiotherapy is in progress.

Despite advances in prostate cancer (PCa) treatment, approximately 40% of patients treated with prostatectomy experience a rise in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels (1,2). Radiotherapy with or without hormone therapy has been the mainstay of recurrent PCa treatment after prostatectomy (3,4). Nonetheless, PSA failure is noted in about 50% of patients after salvage radiotherapy (5), partly because of inappropriate patient selection and nontargeted therapy (3,6).

Imaging has played an essential role in disease localization and treatment planning for salvage radiotherapy in patients with recurrent PCa (7–9). Conventional imaging (CI), including bone scanning, CT, and MRI, has been the standard of care for PCa restaging and radiotherapy planning (7,10,11). Yet, CI has limited ability to accurately define the location and extent of recurrent disease, especially in patients with low PSA levels (6,12–14).

Imaging with novel PET radiotracers has significantly influenced radiotherapy decision making and radiation planning in patients with recurrent PCa (3,9,15,16). 18F-Fluciclovine (Axumin; Blue Earth Diagnostics, Ltd.) is a nonnatural amino acid PET radiotracer that is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the detection of recurrent PCa in patients with rising PSA. Because of its high specificity for extraprostatic disease, 18F-fluciclovine is able to identify both prostatic and extraprostatic recurrence across all PSA levels (17,18). In a preliminary interim analysis of this study, at 87 of 165 accrual, a 40.5% change in salvage radiotherapy management was seen in postprostatectomy patients after guidance with 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT (19). The purpose of this analysis was to report the final results for management decision changes and determine whether the decision change trend remained after completion of accrual.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This prospective randomized clinical trial (Clinical Trials.gov identifier NCT01666808)—Emory Molecular Prostate Imaging for Radiotherapy Enhancement (EMPIRE-1)—consisting of 2 groups (arms A and B), was conducted in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Patients 18 y or older with a history of prostate adenocarcinoma, detectable PSA after prostatectomy, no evidence of extrapelvic disease on CI, and a Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0–2 were enrolled. Exclusion criteria include contraindications to radiotherapy, prior pelvic radiotherapy, previous invasive malignancy (unless disease-free for at least 3 y), and severe acute morbidity. All patients provided written informed consent.

Before randomization, the treating radiation oncologist completed an intention-to-treat form. Patients were randomized to receive either CI (abdominopelvic CT or MRI) only (arm A) or CI plus 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT (arm B) before radiotherapy using a computer-generated schedule. All patients had standard-of-care 99mTc-methylene diphosphonate bone scanning. Patient follow-up for a minimum of 3 y with PSA and other clinical parameters (every 6 mo) is ongoing. This current report will focus mainly on management decision changes based on 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT guidance (arm B only), because data on these changes are available earlier than cancer control outcomes.

18F-Fluciclovine PET/CT Imaging Protocol

18F-Fluciclovine was prepared as previously reported (20). After at least 4 h of fasting, patients ingested an oral contrast medium. One hour later, abdominopelvic CT (slice thickness, 3.75 mm; spacing, 3.25 mm) was completed for anatomic imaging and attenuation correction (∼100 mAs and 120 kVp). After this, 370 ± 11.1 MBq (10.1 ± 0.3 mCi) of 18F-fluciclovine were injected intravenously. Afterward, dual-time-point (5–15.5 min and 16–27.5 min) imaging was completed, using 4 consecutive 2.5 min/bed position PET acquisitions from pelvis to diaphragm. PET/CT images were acquired on a Discovery MV690 16-slice integrated scanner (GE Healthcare). Images were reconstructed with iterative technique (VUE Point Fx [GE Healthcare]; 3 iterations, 24 subsets, 6.4-mm filter cutoff) and transferred to a MIMVista workstation (MIM Software) for interpretation.

Image Analysis

CI was performed and interpreted per institutional protocol before the 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT scan. 18F-Fluciclovine PET/CT images were interpreted independently by 2 board-certified nuclear medicine physicians (over 20 y experience each), with consensus agreement on discordant interpretations. The readers did not know the patient’s clinical history (beyond inclusion criteria) and other imaging results, to avoid interpretation bias. 18F-Fluciclovine PET positivity in the prostate bed, lymph nodes, or bone was defined as persistent nonphysiologic moderate (greater than marrow) focal uptake (17).

Management Decision Criteria

The prostate bed and pelvic lymph nodes were evaluated using the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group contouring guidelines (21). Initial (prefluciclovine) radiotherapy decisions were based on clinical history, histopathology findings at prostatectomy (lymph node–positive, margin-positive, seminal vesicle–positive, and extracapsular extension), PSA trajectory, and CI findings using well-recognized clinical criteria (22). Final radiotherapy decisions were based on 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT findings. If there was no uptake or if uptake was in the prostate bed only, radiotherapy (64.8–70.2 Gy in 1.8-Gy fractions) was delivered to only the prostate (surgical) bed as the standard field, or additionally to the area of uptake, respectively. If there was pelvic nodal uptake or pN1 (regional node involvement), radiotherapy (45.0–50.4 Gy in 1.8-Gy fractions) was performed to the pelvis plus the prostate (surgical) bed. If there was extrapelvic uptake, no radiotherapy was performed; instead, systemic therapy was offered.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated that a sample of 146 patients (73 in each arm) were needed to test a 20% difference in 3-y failure-free survival (50% vs. 70%) between arms at a 0.05 level of significance with 80% power (23). Assuming a withdrawal or dropout rate of 10%, the overall target enrollment was a minimum of 162 subjects. Positivity rates on CI and 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT for detection of recurrent PCa were determined and compared using the χ2 or Fisher exact test. The κ-statistic was used to determine interreader agreement for 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT.

Treatment plans before and after 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT were compared and changes noted. The statistical significance of changes regarding the overall radiotherapy decision, the decision on whether to offer radiotherapy, and the decision on the extent of the radiotherapy field (i.e., whether to treat only the prostate bed or to include the pelvic nodes) was calculated using the Clopper–Pearson (exact) binomial method. Two-sample t testing and Kruskal–Wallis testing were used to determine the differences in mean PSA at PET, Gleason score, and prostatectomy-to-PET interval between patients with and without decision changes. A P value of less than 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Data were analyzed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Eighty-three of 165 patients enrolled in the study between September 2012 and March 2019 were randomized into arm B. Four of 83 patients did not undergo 18F-fluciclovine PET. Therefore, only 79 patients were analyzed. The median PSA at PET was 0.33 ng/mL (range, 0.02–31.00 ng/mL). Patient characteristics are outlined in Table 1. Supplemental Table 1 describes Arm A (CI only) demographics (supplemental materials are available at http://jnm.snmjournals.org).

TABLE 1.

Demographic, Clinical, and Histopathologic Characteristics of Arm B (CI Plus 18F-Fluciclovine PET; n = 79)

| Characteristic | Data |

|---|---|

| Mean age (y) | 61.6 (SD, 7.6) |

| Median PSA at PET scan (ng/mL) | 0.33 (range, 0.02–31.00) |

| Gleason score (n) | |

| 3 + 3 (grade group 1) | 8 (10.1%) |

| 3 + 4 (grade group 2) | 27 (34.2%) |

| 4 + 3 (grade group 3) | 23 (29.1%) |

| ⩾4 + 4 (grade groups 4 and 5) | 21 (26.6%) |

| Primary tumor stage (n) | |

| T1–T2 | 37 (46.8%) |

| T3–T4 | 42 (53.2%) |

| Extracapsular extension (n) | 36 (45.6%) |

| Seminal vesicle invasion (n) | 24 (30.4%) |

| Margin-positive (n) | 34 (43.0%) |

| Node-positive (n) | 15 (19.0%) |

| Ongoing ADT at PET* (n) | 12 (15.4%) |

| Mean duration on ADT before PET (d) | 40 (SD, 31) |

| Median prostatectomy-to-CI interval (y) | 1.6 (range, 0.0–11.3) |

| Median prostatectomy-to-PET interval (y) | 1.7 (range, 0.2–11.5) |

n = 78 patients.

Detection of Recurrence on 18F-Fluciclovine PET/CT

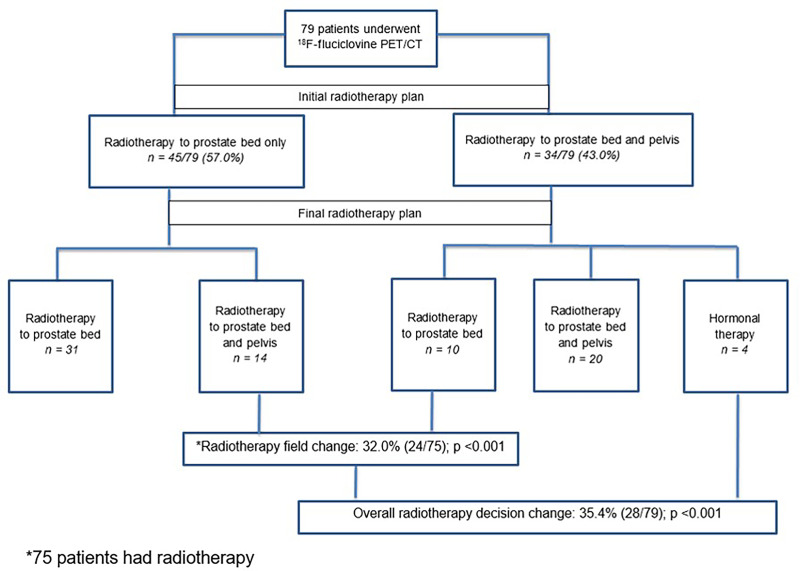

Sixty-three of 79 (79.7%) patients had positive 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT results. On whole-body analysis, the positivity rate on 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT was 75.4% for PSA 1 ng/mL or lower and 90.9% for PSA higher than 1 ng/mL (Table 2). κ was 0.59 in the prostate, 0.83 in the pelvis, and 0.67 in the extrapelvic regions.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of Positivity Rates on CI and 18F-fluciclovine PET

| Whole body | Prostate bed | Pelvic lymph nodes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | CI | PET | P | CI | PET | P | CI | PET | P |

| All patients (n = 79) | 11/79 (13.9) | 63/79 (79.7) | <0.001 | 4/79 (5.1) | 55/79 (69.6) | <0.001* | 8/79 (10.1) | 30/79 (38.0) | <0.001 |

| ≤1 ng/mL (n = 57) | 5/57 (8.8) | 43/57 (75.4) | <0.001 | 2/57 (3.5) | 39/57 (68.4) | <0.001* | 3/57 (5.3) | 16/57 (28.1) | 0.002* |

| >1 ng/mL (n = 22) | 6/22 (27.3) | 20/22 (90.9) | <0.001* | 2/22 (9.1) | 16/22 (72.7) | <0.001* | 5/22 (22.7) | 14/22 (63.6) | 0.014 |

Fisher exact test.

Data are number followed by percentage in parentheses.

CI Analysis

Seventy-one MRI and 8 CT scans were performed. On whole-body analysis, the positivity rate on CI was 8.8% for PSA 1 ng/mL or lower and 27.3% for PSA higher than 1 ng/mL (Table 2). No patient had extrapelvic metastasis, per the inclusion criteria.

Comparison Between Positivity Rates on 18F-Fluciclovine PET/CT and CI

18F-Fluciclovine PET/CT had a significantly higher positivity rate than CI for the whole body (79.7% vs. 13.9%; P < 0.001), prostate bed (69.6% vs. 5.1%; P < 0.001), and pelvic lymph nodes (38.0% vs. 10.1%; P < 0.001). These differences were significant across PSA levels (Fig. 1; Table 2). 18F-Fluciclovine PET/CT detected extrapelvic disease not previously seen on CI in 4 of 79 (5.1%) patients; 2 patients had uptake in extrapelvic lymph nodes, whereas 2 other patients had uptake in bone with or without extrapelvic lymph nodes.

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of positivity rates on CI and 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT. LN = lymph node.

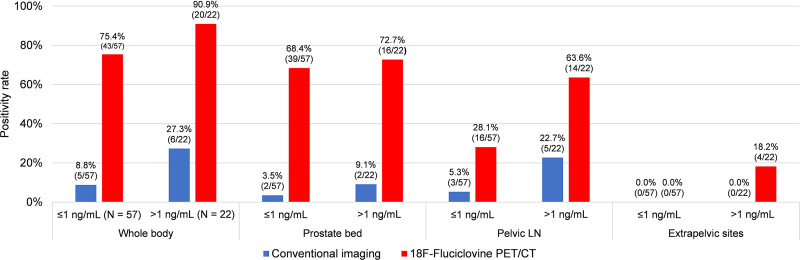

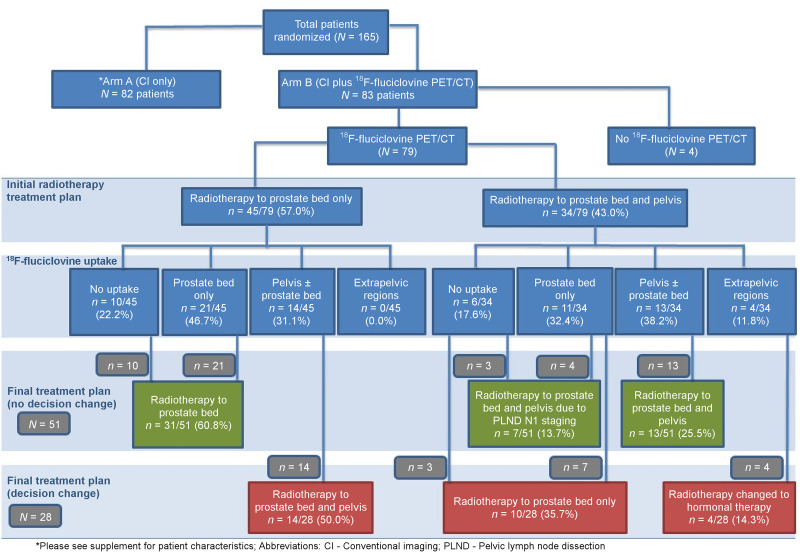

Management Decision Change

All 79 patients were initially planned to receive radiotherapy either to the prostate bed only (45 patients) or to the prostate bed and pelvis (34 patients). Details of the 18F-fluciclovine uptake pattern and the initial and final treatment decisions are shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Study flow diagram showing initial and final radiotherapy decisions.

Overall Decision Change

On the basis of the 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT findings, the overall radiotherapy decision was changed in 28 of 79 (35.4%) patients (Table 3). Although there were 4 major decision changes to not offer radiotherapy because of extrapelvic disease detected on PET, this difference, when considered alone, did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.120, Table 4). Subgroup analyses showed a 76.5% positivity rate on 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT and a 29.4% management change in patients with PSA lower than 0.5 ng/mL. Additionally, androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) decisions were changed in 5 patients; 2 patients who had not been offered ADT before 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT were offered ADT afterward, and 3 patients initially planned for short-term ADT were offered long-term ADT because of extrapelvic disease detected on 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT.

TABLE 3.

Influence of 18F-Fluciclovine on Overall Decision Change

| Postfluciclovine decision | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prefluciclovine decision | Prostate bed only | Pelvis ± prostate bed | No XRT | Decision change | P |

| Overall XRT decision (n = 79) | <0.001 | ||||

| XRT to prostate bed only | 31 | 14* | 0 | 14/79 (17.7%) | |

| XRT to prostate bed + pelvis | 10* | 20 | 4* | 14/79 (17.7%) | |

| No XRT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/79 (0.0%) | |

| Overall decision change | 35.4% | ||||

*Decision change.

XRT = radiotherapy.

TABLE 4.

Influence of 18F-Fluciclovine on Radiotherapy Decision Change

| Postfluciclovine decision | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prefluciclovine decision | Offer XRT | No XRT | Decision change | P |

| XRT decision (n = 79) | 0.120 | |||

| Offer XRT | 75 | 4 | 4/79 (5.1%) | |

| No XRT | 0 | 0 | 0/79 (0.0%) | |

XRT = radiotherapy.

Radiotherapy Field Change

As shown in Table 5, in 24 of 75 (32.0%) patients with a final decision to undergo radiotherapy, the radiotherapy fields changed after 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT. Changes in the overall radiotherapy decision and in the radiotherapy field were both statistically significant (P < 0.001). Representative images showing extrapelvic, pelvic, and prostate bed 18F-fluciclovine uptake are shown in Figures 3, 4, and 5, respectively.

TABLE 5.

Influence of 18F-Fluciclovine on Radiotherapy Field Change

| Postfluciclovine decision | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prefluciclovine decision | Prostate bed only | Pelvis ± prostate bed | Decision change | P |

| Radiotherapy field (n = 75)† | <0.001 | |||

| Prostate bed only (n = 45) | 31 | 14* | 14/75 (18.7%) | |

| Prostate bed + pelvis (n = 30) | 10* | 20 | 10/75 (13.3%) | |

| Field change | 32.0% | |||

Decision change.

Four patients excluded because of extrapelvic uptake.

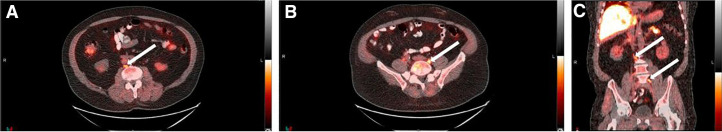

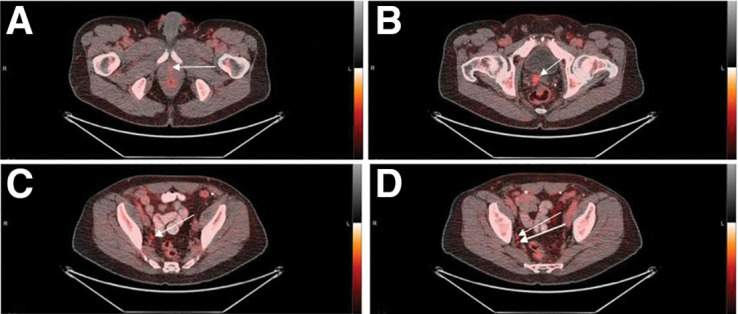

FIGURE 3.

A 72-y-old patient with biochemical recurrence after prostatectomy (PSA, 3.46 ng/mL; Gleason score, 5 + 4 = 9; T3bN1M0). Transaxial (A and B) and coronal (C) PET/CT images show abnormal 18F-fluciclovine uptake (arrows) in retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Radiotherapy decision was withdrawn, and hormonal therapy only was offered.

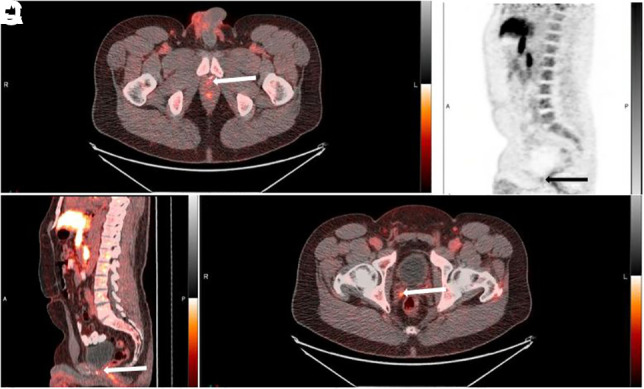

FIGURE 4.

A 64-y-old patient with biochemical recurrence after prostatectomy (PSA, 0.96 ng/mL; Gleason score, 4 + 3 = 7; T3aN0M0). Transaxial PET/CT images (A–D) show abnormal 18F-fluciclovine uptake (arrows) at vesicourethral anastomosis (A), right seminal vesicle (B), right internal iliac lymph node (C), and right obturator lymph node (D). Treatment decision changed from radiotherapy of prostate bed only to radiotherapy of prostate bed and pelvis.

FIGURE 5.

A 53-y-old patient with biochemical recurrence after prostatectomy (PSA, 0.23 ng/mL; Gleason score, 3 + 4 = 7; T2N0M0). Abnormal 18F-Fluciclovine uptake (arrows) is seen at vesicourethral anastomosis on transaxial PET/CT (A), sagittal PET (B), and sagittal PET/CT (C) images and at right seminal vesicle on transaxial PET/CT image (D). Treatment decision changed from radiotherapy of prostate bed and pelvis to radiotherapy of prostate bed only.

Among the prognostic factors examined, the overall mean PSA at PET was significantly higher in patients with radiotherapy decision changes than in those without (Table 6).

TABLE 6.

Prognostic Factors and Radiotherapy Decision Change

| Prognostic factor | Decision change (n = 28) | No decision change (n = 51) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSA at PET (ng/mL) | 2.67 (6.10) | 1.21 (2.30) | 0.033 |

| ⩽1 (n = 57) | 0.36 (0.23) | 0.25 (0.18) | 0.054 |

| >1 (n = 22) | 6.59 (7.43) | 4.33 (3.18) | 0.380 |

| Gleason score | 7.25 (0.89) | 7.39 (0.92) | 0.507 |

| ⩽3 + 4 (n = 35) | 6.69 (0.48) | 6.82 (0.40) | 0.406 |

| ≥4 + 3 (n = 44) | 7.73 (0.88) | 7.83 (0.97) | 0.754 |

| Prostatectomy-to-PET interval (y) | 3.91 (3.64) | 2.51 (2.69) | 0.055 |

| ⩽2 (n = 45) | 0.88 (0.61) | 0.81 (0.52) | 0.706 |

| >2 (n = 34) | 6.53 (3.05) | 5.36 (2.43) | 0.223 |

Data are mean followed by SD in parentheses.

DISCUSSION

Accurate localization and early detection of recurrent PCa are essential for patient selection, targeted therapy, and improved clinical outcomes. This prospective intention-to-treat clinical trial was designed to explore the influence of 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT on radiotherapy planning in postprostatectomy patients with PSA failure.

In this study, 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT resulted in a significant 35.4% change in overall radiotherapy decisions and 32.0% change in radiotherapy fields. The decision to offer radiotherapy was withdrawn and systemic therapy offered in 5.1% of patients because of extrapelvic disease detected only on 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT. In an interim analysis of this study of 42 patients who underwent 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT, we reported a 40.5% overall decision change and a 37.5% radiotherapy field change (19), comparable to the current findings.

The whole-body positivity rate on 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT was 79.7% in this study population, consistent with the reported positivity rates of 79.3% by Pernthaler (24) and 81% by Savir-Baruch (25). In contrast, relatively lower positivity rates on 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT have been found by other studies (26,27), likely related to differences in mean PSA and PSA kinetics. Similar to other studies, we found that the detection rate of recurrent PCa on 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT improves with increased PSA levels: 75.4% for PSA 1 ng/mL or lower and 90.9% for PSA higher than 1 ng/mL (19,25,28,29).

The choice of the radiotherapy field in postprostatectomy patients with recurrent PCa is based primarily on imaging findings (8–11,17). In this study, positive findings on 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT were identified in 53 patients who had negative CI findings. Furthermore, 23 of 28 patients with a management change had negative CI findings. Our results agree with previous studies that have found 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT to perform better than CI in detection of recurrent PCa (17,29). Distant metastases on 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT, not seen on CI, led to the decision to withdraw salvage radiotherapy and offer systemic therapy. These patients may have benefited from the early onset of systemic therapy and been spared the side effects of salvage radiotherapy.

In a prospective multicenter study of 104 men with biochemical recurrence and a median PSA of 0.79 ng/mL, a 64% management change after 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT was reported (26). The lower management change found in our study is likely due to the homogeneous patient population, lower median PSA, exclusion of patients with evidence of extrapelvic disease on CI, and strict predefined major treatment changes. Comparable to our finding, Solanki et al. reported a 48% management change after 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT in 114 postprostatectomy patients with biochemical recurrence (median PSA, 0.42 ng/mL) intended to undergo radiotherapy (27).

In studies evaluating the role of prostate-specific membrane antigen PET/CT in treatment planning, a range of 30.2%–76% has been reported for management change (30–32). Our result of a 29.4% management change in patients with PSA lower than 0.5 ng/mL is similar to that of a retrospective study of 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET/CT in patients with early PSA failure (PSA < 0.5 ng/mL) after prostatectomy, which reported an intended treatment change in 30.2% of patients (30). Treatment modification was also found in 13%–46.7% patients with biochemical recurrence after 11C-choline or 18F-fluorocholine PET (33–35). Thus, our finding of a 35.4% management change is on the lower end of the reported prostate-specific membrane antigen range and the higher end of the choline range. In a recent preliminary report on the primary endpoint of this trial, cancer control, we found that 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT resulted in significant improvement in failure-free survival between the 2 arms at 3 and 4 y after radiotherapy (36). Although other PET radiotracers have reported a change in management comparable to that of 18F-fluciclovine PET, clinical outcome as a primary endpoint in a prospective, randomized, controlled manner for these radiotracers has yet to be reported (37,38).

The randomized prospective design, 2 independent readers with consensus agreement, and homogeneous population of postprostatectomy patients were strengths of this study. Our study had several limitations. First, prefluciclovine radiotherapy decisions were made by several radiotherapy providers. These decisions likely represent a cross-section of decisions made in the prostate radiotherapy community. However, our study was quite rigorous, compared with virtually all other trials, with respect to the handling of post-PET decisions, as these were clearly declared at the outset and providers were held to these decisions. Second, most patients in this study did not have histologic investigation of imaging findings, as the study was not designed to validate the diagnostic performance of 18F-fluciclovine. Prior studies have reported a high positive predictive value for 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT using validated histology data (28). Finally, malignant extraprostatic lesions, especially osteoblastic bone lesions, may have been missed because of inherent radiotracer characteristics such as lower sensitivity in detection of small-volume disease and lack of uptake in some indolent sclerotic lesions (39). However, 18F-fluciclovine has demonstrated superior performance in the prostate bed because of very low urinary excretion (24).

CONCLUSION

This study showed that 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT changes patient management even at low PSA levels. In the setting of treatment planning for salvage radiotherapy after prostatectomy in patients with biochemical recurrence, our findings suggest that imaging with 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT can guide treatment decisions. Follow-up of these patients continues, and further study is ongoing to determine the impact of 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT–guided treatment on clinical outcomes after radiotherapy.

DISCLOSURE

Funding was received from National Institutes of Health R01CA169188; Blue Earth Diagnostics Ltd. provided fluciclovine synthesis cassettes. Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the Biostatistics Shared Resource of Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University and by NIH/NCI under award P30CA138292. Mark Goodman and Emory University are entitled to royalties derived from the sale of products related to the research described in this article. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed and approved by Emory University in accordance with its conflict-of-interest policies. Olayinka Abiodun-Ojo, Ashesh Jani, Akinyemi Akintayo, Oladunni Akin-Akintayo, Oluwaseun Odewole, Funmilayo Tade, Bridget Fielder, and David Schuster receive or received funding from Blue Earth Diagnostics Ltd. through the Emory University Office of Sponsored Projects for other clinical trials using 18F-fluciclovine. David M. Schuster participates through the Emory Office of Sponsored Projects in sponsored grants, including those funded or partially funded by Nihon MediPhysics Co, Ltd.; Telix Pharmaceuticals (US) Inc.; Advanced Accelerator Applications; Fujifilm Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc.; an Amgen Inc. consultant, Syncona; AIM Specialty Health; Global Medical Solutions Taiwan; and Progenics Pharmaceuticals, Inc. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

KEY POINTS

QUESTION: Can 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT influence salvage radiotherapy management decisions in patients with PCa recurrence after prostatectomy?

PERTINENT FINDINGS: In this prospective clinical trial exploring the influence of 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT on salvage radiotherapy decision planning in patients with PCa recurrence after prostatectomy, we found a significant 35.4% change in overall radiotherapy decisions and a 32.0% change in radiotherapy fields.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PATIENT CARE: Appropriate patient selection and targeted therapy through advanced imaging are essential to reduce high biochemical failure rates after salvage radiotherapy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Fenton G. Ingram, RT(R), CNMT, PET; Seraphinah Lawal, RT(R), CNMT, PET; Ronald J. Crowe, RPh, BCNP; and the cyclotron and synthesis team from Emory University Center for Systems Imaging.

REFERENCES

- 1. Han M, Partin AW, Zahurak M, Piantadosi S, Epstein JI, Walsh PC. Biochemical (prostate specific antigen) recurrence probability following radical prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 2003;169:517–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Freedland SJ, Humphreys EB, Mangold LA, et al. Risk of prostate cancer-specific mortality following biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 2005;294:433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rans K, Berghen C, Joniau S, De Meerleer G. Salvage radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2020;32:156–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cornford P, van den Bergh RCN, Briers E, et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II—2020 update: treatment of relapsing and metastatic prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2021;79:263–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stephenson AJ, Scardino PT, Kattan MW, et al. Predicting the outcome of salvage radiation therapy for recurrent prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2035–2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Choo R. Salvage radiotherapy for patients with PSA relapse following radical prostatectomy: issues and challenges. Cancer Res Treat. 2010;42:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kelloff GJ, Choyke P, Coffey DS. Group. PCIW. Challenges in clinical prostate cancer: role of imaging. AJR. 2009;192:1455–1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Amzalag G, Rager O, Tabouret-Viaud C, et al. Target definition in salvage radiotherapy for recurrent prostate cancer: the role of advanced molecular imaging. Front Oncol. 2016;6:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sandgren K, Westerlinck P, Jonsson JH, et al. Imaging for the detection of locoregional recurrences in biochemical progression after radical prostatectomy: a systematic review. Eur Urol Focus. 2019;5:550–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jackson ASN, Reinsberg SA, Sohaib SA, et al. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI for prostate cancer localization. Br J Radiol. 2009;82:148–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pound CR, Brawer MK, Partin AW. Evaluation and treatment of men with biochemical prostate-specific antigen recurrence following definitive therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. Rev Urol. 2001;3:72–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kane CJ, Amling CL, Johnstone PA, et al. Limited value of bone scintigraphy and computed tomography in assessing biochemical failure after radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2003;61:607–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hofman MS, Lawrentschuk N, Francis RJ, et al. Prostate-specific membrane antigen PET-CT in patients with high-risk prostate cancer before curative-intent surgery or radiotherapy (proPSMA): a prospective, randomised, multicentre study. Lancet. 2020;395:1208–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mason BR, Eastham JA, Davis BJ, et al. Current status of MRI and PET in the NCCN guidelines for prostate cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17:506–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jani AB, Schreibmann E, Rossi PJ, et al. Impact of 18F-fluciclovine PET on target volume definition for postprostatectomy salvage radiotherapy: initial findings from a randomized trial. J Nucl Med. 2017;58:412–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mohler JL, Antonarakis ES, Armstrong AJ, et al. Prostate cancer, version 2.2019, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17:479–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schuster DM, Nieh PT, Jani AB, et al. Anti-3-[18F]FACBC positron emission tomography-computerized tomography and 111In-capromab pendetide single photon emission computerized tomography-computerized tomography for recurrent prostate carcinoma: results of a prospective clinical trial. J Urol. 2014;191:1446–1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Robertson MS, Sakellis CG, Hyun H, Jacene HA. Extraprostatic uptake of 18F-fluciclovine: differentiation of nonprostatic neoplasms from metastatic prostate cancer. AJR. 2020;214:641–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Akin-Akintayo OO, Jani AB, Odewole O, et al. Change in salvage radiotherapy management based on guidance with FACBC (fluciclovine) PET/CT in postprostatectomy recurrent prostate cancer. Clin Nucl Med. 2017;42:e22–e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McConathy J, Voll RJ, Yu W, Crowe RJ, Goodman MM. Improved synthesis of anti-[18F]FACBC: improved preparation of labeling precursor and automated radiosynthesis. Appl Radiat Isot. 2003;58:657–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gay HA, Barthold HJ, O’Meara E, et al. Pelvic normal tissue contouring guidelines for radiation therapy: a Radiation Therapy Oncology Group consensus panel atlas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:e353–e362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Abdel-Wahab M, Mahmoud O, Merrick G, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® external-beam radiation therapy treatment planning for clinically localized prostate cancer. J Am Coll Radiol. 2012;9:233–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Klein JP, Moeschberger ML. Survival analysis: techniques for censored and truncated data: Springer; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pernthaler B, Kulnik R, Gstettner C, Salamon S, Aigner RM, Kvaternik H. A prospective head-to-head comparison of 18F-fluciclovine with 68Ga-PSMA-11 in biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer in PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2019;44:e566–e573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Savir-Baruch B, Lovrec P, Solanki AA, et al. Fluorine-18-labeled fluciclovine PET/CT in clinical practice: factors affecting the rate of detection of recurrent prostate cancer. AJR. 2019;213:851–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Scarsbrook AF, Bottomley D, Teoh EJ, et al. Effect of 18F-fluciclovine positron emission tomography on the management of patients with recurrence of prostate cancer: results from the FALCON trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;107:316–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Solanki AA, Savir-Baruch B, Liauw SL, et al. 18F-fluciclovine positron emission tomography in men with biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy and planning to undergo salvage radiation therapy: results from LOCATE. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2020;10:354–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bach-Gansmo T, Nanni C, Nieh PT, et al. Multisite experience of the safety, detection rate and diagnostic performance of fluciclovine (18F) positron emission tomography/computerized tomography imaging in the staging of biochemically recurrent prostate cancer. J Urol. 2017;197:676–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Odewole OA, Tade FI, Nieh PT, et al. Recurrent prostate cancer detection with anti-3-[18F]FACBC PET/CT: comparison with CT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43:1773–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Farolfi A, Ceci F, Castellucci P, et al. 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET/CT in prostate cancer patients with biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy and PSA <0.5 ng/ml: efficacy and impact on treatment strategy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;46:11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Albisinni S, Artigas C, Aoun F, et al. Clinical impact of 68Ga-prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) in patients with prostate cancer with rising prostate-specific antigen after treatment with curative intent: preliminary analysis of a multidisciplinary approach. BJU Int. 2017;120:197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rousseau E, Wilson D, Lacroix-Poisson F, et al. A prospective study on 18F-DCFPyL PSMA PET/CT imaging in biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2019;60:1587–1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ceci F, Herrmann K, Castellucci P, et al. Impact of 11C-choline PET/CT on clinical decision making in recurrent prostate cancer: results from a retrospective two-centre trial. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41:2222–2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Souvatzoglou M, Krause BJ, Pürschel A, et al. Influence of 11C-choline PET/CT on the treatment planning for salvage radiation therapy in patients with biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2011;99:193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lamanna G, Tabouret-Viaud C, Rager O, et al. Long-term results of a comparative PET/CT and PET/MRI study of 11C-acetate and 18F-fluorocholine for restaging of early recurrent prostate cancer. Clin Nucl Med. 2017;42:e242–e246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jani A, Schreibmann E, Goyal S, et al. Initial report of a randomized trial comparing conventional- vs conventional plus fluciclovine (18F) PET/CT imaging-guided post-prostatectomy radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;108:1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. D’Angelillo RM, Fiore M, Trodella LE, et al. 18F-choline PET/CT driven salvage radiotherapy in prostate cancer patients: up-date analysis with 5-year median follow-up. Radiol Med (Torino). 2020;125:668–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Emmett L, Tang R, Nandurkar R, et al. 3-year freedom from progression after 68Ga-PSMA PET/CT-triaged management in men with biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy: results of a prospective multicenter trial. J Nucl Med. 2020;61:866–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Calais J, Ceci F, Eiber M, et al. 18F-fluciclovine PET-CT and 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET-CT in patients with early biochemical recurrence after prostatectomy: a prospective, single-centre, single-arm, comparative imaging trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1286–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]