Abstract

Background: Accessing and using health care in European countries pose major challenges for asylum seekers and refugees due to legal, linguistic, administrative, and knowledge barriers. This scoping review will systematically describe the literature regarding health care for asylum seekers and refugees in high-income European countries, and the experiences that they have in accessing and using health care. Methods: Three databases in the field of public health were systematically searched, from which 1665 studies were selected for title and abstract screening, and 69 full texts were screened for eligibility by the main author. Of these studies, 44 were included in this systematic review. A narrative synthesis was undertaken. Results: Barriers in access to health care are highly prevalent in refugee populations, and can lead to underusage, misuse of health care, and higher costs. The qualitative results suggest that too little attention is paid to the living situations of refugees. This is especially true in access to care, and in the doctor-patient interaction. This can lead to a gap between needs and care. Conclusions: Although the problems refugees and asylum seekers face in accessing health care in high-income European countries have long been documented, little has changed over time. Living conditions are a key determinant for accessing health care.

Keywords: adult refugees, high-income European countries, access to health care, barriers and facilitators

1. Introduction

Asylum application numbers peaked in 2015 and 2016, when more than 2.5 million people applied for asylum in the European Union (EU) [1]. The high number of refugees and asylum seekers has challenged health care systems as health needs accompanied inequity in health care opportunities [2]. This renders migrant and refugee health a political public health topic [3].

It is difficult for refugees to access health care and for health care professionals to provide adequate care due to legal barriers, language barriers, administrative barriers, a lack of information and knowledge of the health care system, and breaks in the continuity of care [4]. When migration trajectories across Europe are considered, there are specific challenges in arrival, transit, and destination countries, such as a lack of coordination between health care providers in arrival countries, a short length of stay in transit countries, and missing social support in destination countries [5]. In particular, it is hard for refugees and asylum seekers to receive specialised care whilst in different migration phases [4,5].

As Lebano et al. (2020) [5] explained in their scoping review on migrants’ access to healthcare in nine European countries, research regarding this issue is scarce, and situations are difficult to compare. The scarcity of evidence and heterogeneity in structures make it even more important to examine the perspective of refugees and asylum seekers on access to health care. How refugees and asylum seekers experience access to care, and what facilitating factors and barriers they perceive, will be elicited in this scoping review. Therefore, the existing evidence will be presented to provide a narrative description of the complex and heterogeneous health care situations of refugees and asylum seekers in high-income European countries. For this purpose, the following questions were investigated:

How do refugees and asylum seekers use health care in high-income European countries, and what barriers do they face?

How do refugees experience access to health care in high-income European countries?

2. Materials and Methods

This review was conducted according to the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews Checklist [6]. No review protocol was published beforehand. The literature search was conducted in the databases PubMed, CINAHL and PsycInfo in April 2017. The search was then updated in the PubMed database in August 2021. The following search terms were used: refugee, asylum seeker, health services accessibility, access to health care, delivery of health care, and adult (cf. Table 1). MeSH terms and/or simple search terms were combined for the search. The terms were linked with the Boolean operators AND and OR. An overview of the search terms is presented in additional file 1. In addition to a database search, studies were included according to the snowball principle (e.g., via bibliographies). No grey literature was included.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the literature search.

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

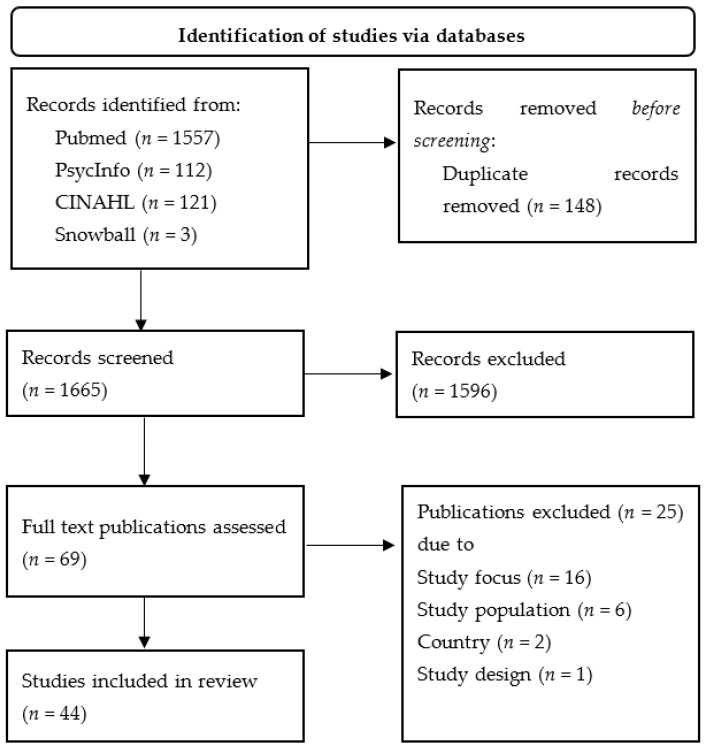

Screening was carried out by the first author only. After excluding duplicates, 1665 studies were included in the screening. After screening the titles, n = 158 were considered for further analysis. After screening the abstracts, n = 69 potentially relevant studies were identified, of which n = 44 were included in the present review after reading the full text (cf. Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRSIMA flow chart.

Studies with adult refugees and asylum seekers were included according to the provisions of the Geneva Refugee Convention or foreigners’ law equivalents. The groups of pregnant and minor refugees were excluded, as they are persons with special care needs. In order to ensure the greatest possible comparability, only studies that represent the situation in the European Region were included. Although the health care systems and residence regulations differ, there are common values between the participating states which have been established, for example, in the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. These include the right to life in Article 2, the right of access to preventive health care in Article 35, or the right to non-discrimination in Article 21.

The analysis included both qualitative and quantitative studies in English and German published from 1992 onwards, due to the conclusion of the Maastricht Treaty and thus the increasing number of refugees and asylum seekers in European countries, and the associated challenges for health and social care throughout that time.

3. Results

Twenty-four quantitative studies, sixteen qualitative studies, and four studies with a mixed-method design were included. The most frequently reported barriers were language barriers (n = 19 studies) and the desire for interpreter care (n = 3), as well as information barriers (n = 14). Furthermore, administrative (n = 10) and financial barriers (n = 7) make access to the care system more difficult for refugees and asylum seekers. The selected studies are summarised according to the research questions in a narrative way. Table 2 presents an overview of the included studies.

Table 2.

Overview of the included studies [4,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50].

| Authors | Publication Year | Country | Setting | Study Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bauhoff and Göpffarth [24] | 2018 | Germany | Cost analysis | Quantitative |

| Bhatia and Wallace [8] | 2007 | UK | Primary Care | Qualitative |

| Bhui et al. [15] | 2006 | UK | Inpatient psychiatric care | Quantitative |

| Bianco et al. [31] | 2015 | Italy | Health care by NGOs | Quantitative |

| Biddle et al. [32] | 2019 | Germany | Inpatient and outpatient care | Quantitative |

| Bischoff et al. [40] | 2003 | Switzerland | Inpatient care | Quantitative |

| Blöchliger et al. [50] | 1998 | Switzerland | Primary Care | Quantitative |

| Boettcher et al. [18] | 2021 | Germany | Psychiatric care | Quantitative |

| Borgschulte et al. [29] | 2018 | Germany | Primary care | Mixed-Method |

| Bozorgmehr et al. [30] | 2015 | Germany | Primary Care | Quantitative |

| Chiarenza et al. [4] | 2019 | European countries | Transit | Mixed-Method |

| Cignacco et al. [28] | 2018 | Switzerland | Sexual and reproductive care | Mixed-Method |

| Claassen & Jäger [26] | 2018 | Germany | Primary Care | Quantitative |

| Fang et al. [12] | 2015 | UK | Primary Care | Qualitative |

| Feldmann et al. [47] | 2007a | Netherlands | Primary Care | Qualitative |

| Feldmann et al. [49] | 2007b | Netherlands | Primary Care | Qualitative |

| Führer et al. [19] | 2020 | Germany | Psychiatric care | Quantitative |

| Gerritsen et al. [34] | 2006 | Netherlands | Primary Care | Quantitative |

| Hahn et al. [10] | 2020 | Germany | Inpatient and outpatient care | Qualitative |

| Jäger et al. [27] | 2019 | Germany | Primary care | Quantitative |

| Jensen et al. [46] | 2014 | Denmark | Inpatient psychiatric Care | Qualitative |

| Kang et al. [13] | 2019 | UK | Primary Care | Qualitative |

| Klingberg et al. [35] | 2020 | Switzerland | Emergency care | Quantitative |

| Kohlenberger et al. [33] | 2019 | Austria | Inpatient and outpatient care | Quantitative |

| Laban et al. [16] | 2007 | Netherlands | Primary care | Quantitative |

| Lamkaddem et al. [38] | 2014 | Netherlands | Psychiatric Care | Quantitative |

| Maier et al. [23] | 2010 | Switzerland | Cost analysis | Quantitative |

| Mangrio et al. [43] | 2018 | Sweden | Inpatient and outpatient care | Mixed-Method |

| Mårtensson et al. [44] | 2020 | Sweden | Health care information | Qualitative |

| Melamed et al. [20] | 2019 | Switzerland | Psychiatric care | Qualitative |

| Norredam et al. [7] | 2005 | EU countries | Comparative study | Quantitative |

| O’Donnell [39] | 2007 | UK | Primary Care | Qualitative |

| O’Donnell [48] | 2008 | UK | Primary Care | Qualitative |

| Razavi et al. [45] | 2011 | Sweden | Long term health care | Qualitative |

| Riza et al. [37] | 2020 | EU | Inpatient and outpatient care | Quantitative |

| Schein et al. [42] | 2019 | Norway | Inpatient and outpatient care | Qualitative |

| Schneider et al. [11] | 2015 | Germany | Inpatient and outpatient care | Quantitative |

| Spura et al. [9] | 2017 | Germany | Inpatient and outpatient care | Qualitative |

| Toar et al. [21] | 2009 | Ireland | Psychiatric care | Quantitative |

| Van Loenen et al. [14] | 2017 | EU | Primary Care | Qualitative |

| Wångdahl et al. [36] | 2018 | Sweden | Health literacy | Quantitative |

| Wenner et al. [25] | 2020 | Germany | Inpatient and outpatient care | Quantitative |

| Wetzke et al. [17] | 2018 | Germany | Primary Care | Quantitative |

| Zander et al. [41] | 2013 | Sweden | Inpatient and outpatient care | Qualitative |

3.1. Descriptive Results on Utilisation and Access Barriers

Twenty-two studies reported results on health care access for refugees and asylum seekers, such as formal and bureaucratic barriers in reception countries [7,8,9,10,11,12,13], during flight [4,14], and the influence of length of stay and legal status on the use of health care services [7,8,15,16,17,18]. Five studies [18,19,20,21,22] took into account the use of health care by groups under vulnerable conditions, such as refugees with mental illnesses. Two studies evaluated the financial burden of the health care systems used by refugees and asylum seekers [23,24]. Three other studies compared two access models for refugees in Germany [25,26,27].

Refugees and asylum seekers experience different access barriers to health care during flight through Europe [4,14]. In the countries of arrival and transit, the high number of asylum seekers, short-term stays, and uncoordinated health care can negatively impact access to, and quality of, care. A lack of patient records and information on the health status of patients during flight and in reception countries [14,28,29], as well as the involvement of different actors and organisations [4,14], lead to a lack of equity of need, duplication of treatment, and overlaps in care. In the destination countries, asylum seekers face a multitude of legal, financial, and administrative barriers to access [4]. Access to the health care system has primarily been subject to formal legal barriers [7]. In 10 out of 23 surveyed countries in the EU in 2004, there were access barriers to the health care system. Such countries include Austria, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Luxembourg, Malta, Spain and Sweden. With the exception of Austria, asylum seekers were only entitled to emergency health care. Although health care access has changed in some countries after the refugee migration in 2015/2016, this has not been systematically evaluated yet.

More recent studies have evaluated the utilisation rates of refugees and asylum seekers in host countries. These range from 1% to 90%, depending on physician specialty. In literature, utilisation rates of 52–85% for GPs [30,31,32], 22.4–42.5% for specialist care [30,32,33], and from 1% to 15.5% for psychotherapeutic care were seen [18,19,30]. Differences can be partly explained by gender [30,33,34], length of stay [16,17], country of origin [24,33], age [34] and low health literacy [35,36]. Differences are probably also due to the living and housing situation, as well as legal status, and formal restrictions in access to care. In comparison to reference populations, a lower use of GPs but higher use of hospitals and emergency care were seen [11,24], which can lead to higher expenditures [23,24]. Unmet health care needs are highly prevalent, and range from 20% to 45.2% [18,30,32,37]. Refugees and asylum seekers with mental illness found it especially difficult to receive adequate care [18,19,21,23,38]. In addition, a lack of culturally and gender-sensitive systems inhibits access to health care [10,28].

By reducing bureaucratic barriers, the use of health care can be improved, as has been shown, for example, through the introduction of new care models in Germany [25,26,27]. In addition, needs-based accommodation and social support can play a major key in access to health care [22,31].

3.2. Lived Experiences of Asylum Seekers and Refugees Using Health Care in Host Countries

Qualitative findings can be used to explain the experiences refugees and asylum seekers have and the barriers that they face in transit through Europe, and in host countries, in more detail. Language challenges are identified as key barriers to accessing and using the care system [8,10,12,13,39,40], due to experiences of dependency to understand, and to be understood [41]. Difficulties in obtaining a qualified interpreter are apparent. Interruptions in care can occur when interpreters are not available. At times, the relationship with the interpreter is characterised by mistrust [8,12,20,39]. This can lead to misunderstandings, and incorrect diagnoses in treatment situations. From the perspective of refugees and asylum seekers, it is important that interpreters know medical terminology and are culturally competent [12]. In addition, in two studies, a strong desire for continuous support from the same interpreter was found [8,39]. One study highlights the importance of language acquisition to the experience of autonomy and control in the treatment situation [42].

“Waiting” plays a key role—both in asylum seekers’ lives, and in health care [12,20,42,43]. For example, refugees describe having to wait a long time for doctor’s appointments. This is particularly important when symptoms are interpreted differently, as O’Donnell et al. (2007) [39] describe. For example, flu symptoms may, in some countries of origin, indicate a life-threatening illness, whereas in host countries they indicate little need for medical treatment. The discrepancy between subjective and medical needs, and the lack of familiarity with the spectrum of illnesses in the destination countries [44], can potentially lead to late access to care for serious health problems [12], or to emergency room visits for non-critical illnesses [39]. From the refugees’ perspective, concrete and explanatory health information made available from a variety of sources could help to strengthen knowledge on the health care system [44].

The complexity of health care processes and procedures can present challenges [45,46]. This is particularly evident in transit through Europe [14], when unfamiliarity with illness and treatment strategies can result in a discrepancy between expectations of care, and actual care [45]. This can lead to care disruptions [41]. As a result, refugees may feel uncertain as to how they should behave in the system, and what is expected of them as patients [45].

Six of the studies highlight the importance of friends, family, and social organisations in negotiating health care [8,20,38,42,46,47]. Social support is seen as the most important component for experiencing health and illness. The breakdown of trusting contacts in destination countries can affect mental health and lead to the non-utilisation of care [20]. Where support is available to access the health care system, e.g., an asylum support nurse in the accommodation, feelings of being welcomed are reported [39]. At the same time, the accommodation situation can be experienced as a barrier to accessing health care, especially when having to address the manager to ask for medical treatment [20,42]. A similar situation is reported by Spura et al. (2017) [9] and Hahn et al. (2020) [10] for the issuing of treatment vouchers at the social welfare office for asylum seekers in Germany.

The legal situation can also be an influencing factor. For example, Fang et al. (2015) [12] report that health care is not used because participants are afraid of consequences to their legal status. Schein et al. (2019) [42] note that the experience with the Norwegian health care system depends on the length of stay and the residence status. Uncertainty in the ongoing asylum procedure overlays the entirety of an asylum seekers’ life, leaving little space for healthcare. In addition, the interviewees feel “invisible” in the care system [42], as they do not possess a national insurance number, or “left out” by being an asylum seeker [39]. A rejected asylum decision can lead to a sudden lack of entitlements to health care, and thus the experience of loss of resources [12].

Societal conditions lead to experiences of hostility in health care through which refugees experience themselves as a “burden” for the system [8]. They may then withdraw from the health care system out of fear of stigmatisation. Moreover, refugees are often treated as representatives of refugees as a group, and not seen as individual patients [47]. Labelling as an “asylum seeker” or “refugee” leads to experiences of othering [12], and to possibly false assumptions about health status [47]. This creates feelings of difference and exclusion [39,48].

Too little attention is paid to the complex health needs and realities of refugees’ lives [12,45,46]. This can lead to perceived excessive medicalisation [45,46] because life experiences are not sufficiently acknowledged in the health care system. In addition, re-traumatising experiences can be triggered, as described by an interviewee in the study by Jensen et al. (2014) [46], who experienced flashbacks relating to her prison stay in her home country by being placed in a closed psychiatric ward.

Jensen et al. (2014) [46] provide insight into the specific care needs of refugees and asylum seekers. In qualitative interviews with native Danes, migrants, and refugees about access to and the course of treatment in psychiatric care in Denmark challenges were seen for all participants. These challenges in accessing the health system and in the course of treatment are characterised by rejection, interruptions, and transitions. At the same time, unique challenges for refugees and asylum seekers arise as there is not always a social network present to help access health care easily or to ensure childcare in the case of an inpatient stay.

The promoting factors mentioned include a trusting relationship with the attending doctor [8,48], adequate provision of interpreters [9,12], respectful interaction [12,49], comprehensive information about the health care system [12,39,44], an individual approach to health problems [47,49], and a good social network [41]. Adequate intercultural training of doctors could also reduce existing health care problems [50].

4. Discussion

This review reveals that health care for refugees in high-income European countries is restricted by a multitude of access barriers. Institutional and legal barriers to access especially impede the integration of refugees into regular care. Language and information barriers can lead to mistreatment, inadequate care provision, and underusage of (ambulatory) services, especially for patient groups in vulnerable conditions. All reported barriers lead to challenges for health care professionals and patients, as well as unmet care needs.

In this scoping review, we considered papers from 1992 onwards. There have been few changes in access to health care for refugees and asylum seekers over time. In particular, when comparing the data before and after the 2015 refugee movement, we can identify the same care problems, despite the fact that the following care problems have been well known for a long time: restrictions in care, language and information barriers, lack of funding for interpreters, no adequate care pathways, and lack of culturally sensitive care services. Overall, needs-based care for refugees in high-income European countries is rare, and health care does not correspond adequately. Recommendations for need-based care for refugees can be found in the literature, and can be drawn from our scoping review [4,5,51,52]: removal of legal restrictions, funding and provision of culturally sensitive and trained interpreters [53,54], strengthening health literacy [55], early screening for mental illness [52], low-threshold access to care [37], and intercultural training to reduce stereotyping and avoid discrimination [49].

The included qualitative studies provide new insights into the experience of health care in host countries. It can be seen that access to health care as a determinant of health [56] is strongly influenced by life circumstances. Postmigration stressors, such as legal status [42], hostile conditions in host countries [8], or lack of social network [20], play a key role here. This is especially important for refugees because health can be an influencing facilitator of integration, as well as the outcome of successful integration [57,58]. However, qualitative data reveal that refugees often find themselves in ongoing dependency relationships, for example, due to restrictions in access to the health care system by authorities, or facility managers, having to rely on adequate translation by the interpreter, or in relation to their residence status. This leads to feelings of disempowerment and exclusion in access to and use of health care [39]. Health care professionals should therefore be aware of the individual situations of refugees and asylum seekers. However, it has been shown that life experiences are not sufficiently accounted for in the treatment situation, which can be associated with negative health consequences [46]. In some cases, discriminatory and exclusionary practice due to the homogenisation of refugees and asylum seekers is evident [47]. Therefore, culturally sensitive and individualised care is necessary to empower refugees and asylum seekers to make adequate health decisions for themselves. For this, it is even more important to take the living conditions into account. For example, support for language acquisition early in their stay can strengthen the position of asylum seekers and refugees in health care. As shown by Schein et al. (2019) [42], improvements in language skills lead to experiences of autonomy and control in the treatment situation. Needs-based accommodation can also be beneficial [22]. Therefore, the access to and use of health care have to be seen in a broader socio-economic-legal context, with special emphasis on individuals’ life realities.

The overall aim of this scoping review was to map the literature and provide a broad overview of access to health care for refugees and asylum seekers in high-income European countries, including the perspectives of refugees and asylum seekers. Although the literature has been comprehensively presented, there have been methodological and content-related limitations. The literature search and screening were conducted only by the first author. Therefore, it may be that not all relevant studies have been included. Grey literature, which may have led to further insights in the research field, was excluded. Due to the inclusion of different study types with heterogenous outcome parameters, no quality assessment was carried out. Therefore, a potential bias of studies must be taken into account.

Even though we only included refugees and asylum seekers, they are a heterogenous study population with diverse cultural and sociodemographic backgrounds. The impact of gender or socioeconomic background on health care needs and associated use and access to health care services was not considered. As shown in this review, reception conditions differ in high-income European countries, and so it was sometimes difficult to generalize results. In general, however, barriers to the access to health care for refugees and asylum seekers are evident across national borders, and they are vocalized by refugees and asylum seekers in detail.

5. Conclusions

Access to health care for refugees and asylum seekers in high-income European countries is challenging and has scarcely changed over time. In addition to removing legal, linguistic, formal, and organisation barriers, the living conditions of refugees should be given greater consideration in the provision of care. On the one hand, they influence the development of health and illness directly. On the other hand, an improvement in living conditions and liberation from dependencies can lead to a sense of agency and experiences of empowerment in health care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.N. and C.H.; Data Curation, A.C.N.; Methodology, A.C.N.; Formal Analysis, A.C.N.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, A.C.N.; Writing—Review and Editing, A.C.N., Y.N. and C.H.; Supervision, C.H.; Funding Acquisition, C.H. among others. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry for Culture and Science of the German federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia within the graduate school ‘FlüGe—opportunities and challenges of global refugee migration for health care in Germany’, grant number 321-8.03.07-127600. The APC was funded by Universitaetsbibliothek Bielefeld.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in the published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Eurostat Asylbewerber und Erstmalige Asylbewerber nach Staatsangehörigkeit, Alter und Geschlecht—Jährliche Aggregierte Daten (Gerundet) Data File. 2021. [(accessed on 8 January 2022)]. Available online: https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=migr_asyappctza&lang=de.

- 2.Brandenberger J., Tylleskär T., Sontag K., Peterhans B., Ritz N. A systematic literature review of reported challenges in health care delivery to migrants and refugees in high-income countries: The 3C model. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:755. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7049-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith J. Migrant health is public health, and public health needs to be political. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3:e418. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30161-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiarenza A., Dauvrin M., Chiesa V., Baatout S., Verrept H. Supporting access to healthcare for refugees and migrants in European countries under particular migratory pressure. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019;19:513. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4353-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lebano A., Hamed S., Bradby H., Gil-Salmerón A., Durá-Ferrandis E., Garcés-Ferrer J., Azzedine F., Riza E., Karnaki P., Zota D., et al. Migrants’ and refugees’ health status and healthcare in Europe: A scoping literature review. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1039. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08749-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tricco A.C., Lillie E., Zarin W., O’Brien K.K., Colquhoun H., Levac D., Moher D., Peters M.D.J., Horsley T., Weeks L., et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018;169:467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norredam M., Mygind A., Krasnik A. Access to health care for asylum seekers in the European Union—a comparative study of country policies. Eur. J. Public Health. 2006;16:286–290. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhatia R., Wallace P. Experiences of refugees and asylum seekers in general practice: A qualitative study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2007;8:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spura A., Kleinke M., Robra B.P., Ladebeck N. How do asylum seekers experience access to medical care? Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundh. Gesundh. 2017;60:462–470. doi: 10.1007/s00103-017-2525-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hahn K., Steinhäuser J., Goetz K. Equity in Health Care: A Qualitative Study with Refugees, Health Care Professionals, and Administrators in One Region in Germany. BioMed Res. Int. 2020;2020:4647389. doi: 10.1155/2020/4647389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider C., Joos S., Bozorgmehr K. Disparities in health and access to healthcare between asylum seekers and residents in Germany: A population-based cross-sectional feasibility study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008784. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang M.L., Sixsmith J., Lawthom R., Mountian I., Shahrin A. Experiencing ‘pathologized presence and normalized absence’; understanding health related experiences and access to health care among Iraqi and Somali asylum seekers, refugees and persons without legal status. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:923. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2279-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang C., Tomkow L., Farrington R. Access to primary health care for asylum seekers and refugees: A qualitative study of service user experiences in the UK. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2019;69:e537–e545. doi: 10.3399/bjgp19X701309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Loenen T., van den Muijsenbergh M., Hofmeester M., Dowrick C., van Ginneken N., Mechili E.A., Angelaki A., Ajdukovic D., Bagic H., Pavlic D.R., et al. Primary care for refugees and newly arrived migrants in Europe: A qualitative study on health needs, barriers and wishes. Eur. J. Public Health. 2018;28:82–87. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckx210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhui K., Audini B., Singh S., Duffett R., Bhugra D. Representation of asylum seekers and refugees among psychiatric inpatients in London. Psychiatr. Serv. 2006;57:270–272. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laban C.J., Gernaat H.B., Komproe I.H., De Jong J.T. Prevalence and predictors of health service use among Iraqi asylum seekers in the Netherlands. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2007;42:837–844. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0240-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wetzke M., Happle C., Vakilzadeh A., Ernst D., Sogkas G., Schmidt R.E., Behrens G.M.N., Dopfer C., Jablonka A. Healthcare Utilization in a Large Cohort of Asylum Seekers Entering Western Europe in 2015. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018;15:2163. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15102163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boettcher V.S., Nowak A.C., Neuner F. Mental health service utilization and perceived barriers to treatment among adult refugees in Germany. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2021;12:1910407. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2021.1910407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Führer A., Niedermaier A., Kalfa V., Mikolajczyk R., Wienke A. Serious shortcomings in assessment and treatment of asylum seekers’ mental health needs. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0239211. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melamed S., Chernet A., Labhardt N.D., Probst-Hensch N., Pfeiffer C. Social Resilience and Mental Health Among Eritrean Asylum-Seekers in Switzerland. Qual. Health Res. 2019;29:222–236. doi: 10.1177/1049732318800004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toar M., O’Brien K.K., Fahey T. Comparison of self-reported health & healthcare utilisation between asylum seekers and refugees: An observational study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gottlieb N., Püschmann C., Stenzinger F., Koelber J., Rasch L., Koppelow M., Al Munjid R. Health and Healthcare Utilization among Asylum-Seekers from Berlin’s LGBTIQ Shelter: Preliminary Results of a Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:4514. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maier T., Schmidt M., Mueller J. Mental health and healthcare utilization in adult asylum seekers. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2010;140:w13110. doi: 10.4414/smw.2010.13110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bauhoff S., Göpffarth D. Asylum-seekers in Germany differ from regularly insured in their morbidity, utilizations and costs of care. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0197881. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wenner J., Bozorgmehr K., Duwendag S., Rolke K., Razum O. Differences in realized access to healthcare among newly arrived refugees in Germany: Results from a natural quasi-experiment. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:846. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08981-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Claassen K., Jäger P. Impact of the Introduction of the Electronic Health Insurance Card on the Use of Medical Services by Asylum Seekers in Germany. Int J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018;15:856. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15050856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jäger P., Claassen K., Ott N., Brand A. Does the Electronic Health Card for Asylum Seekers Lead to an Excessive Use of the Health System? Results of a Survey in Two Municipalities of the German Ruhr Area. Int J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019;16:1178. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16071178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cignacco E., Zu Sayn-Wittgenstein F., Sénac C., Hurni A., Wyssmüller D., Grand-Guillaume-Perrenoud J.A., Berger A. Sexual and reproductive healthcare for women asylum seekers in Switzerland: A multi-method evaluation. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018;18:712. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3502-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borgschulte H.S., Wiesmüller G.A., Bunte A., Neuhann F. Health care provision for refugees in Germany—one-year evaluation of an outpatient clinic in an urban emergency accommodation. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018;18:488. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3174-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bozorgmehr K., Schneider C., Joos S. Equity in access to health care among asylum seekers in Germany: Evidence from an exploratory population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015;15:502. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1156-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bianco A., Larosa E., Pileggi C., Nobile C.G.A., Pavia M. Utilization of health-care services among immigrants recruited through non-profit organizations in southern Italy. Int J. Public Health. 2016;61:673–682. doi: 10.1007/s00038-016-0820-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biddle L., Menold N., Bentner M., Nöst S., Jahn R., Ziegler S., Bozorgmehr K. Health monitoring among asylum seekers and refugees: A state-wide, cross-sectional, population-based study in Germany. Emerg. Themes Epidemiol. 2019;16:3. doi: 10.1186/s12982-019-0085-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kohlenberger J., Buber-EnnserI I., Rengs B., Leitner S., Landesmann M. Barriers to health care access and service utilization of refugees in Austria: Evidence from a cross-sectional survey. Health Policy. 2019;123:833–839. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerritsen A.A.M., Bramsen I., Devillé W., van Willigen L.H.M., Hovens J.-E., van der Ploeg H.M. Use of health services by Afghan, Iranian, and Somali refugees and asylum seekers living in the Netherlands. Eur. J. Public Health. 2016;16:394–399. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klingberg K., Stoller A., Müller M., Jegerlehner S., Brown A.D., Exadaktylos A., Jachmann A., Srivastava D. Asylum Seekers and Swiss Nationals with Low-Acuity Complaints: Disparities in the Perceived level of Urgency, Health Literacy and Ability to Communicate:A Cross-Sectional Survey at a Tertiary Emergency Department. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:2769. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wångdahl J., Lytsy P., Mårtensson L., Westerling R. Poor health and refraining from seeking healthcare are associated with comprehensive health literacy among refugees: A Swedish cross-sectional study. Int. J. Public Health. 2018;63:409–419. doi: 10.1007/s00038-017-1074-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riza E., Karnaki P., Gil-Salmerón A., Zota K., Ho M., Petropoulou M., Katsas K., Garcés-Ferrer J., Linos A. Determinants of Refugee and Migrant Health Status in 10 European Countries: The Mig-HealthCare Project. Int J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:6353. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17176353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lamkaddem M., Stronks K., Devillé W.D., Olff M., Gerritsen A.A., Essink-Bot M.L. Course of post-traumatic stress disorder and health care utilisation among resettled refugees in the Netherlands. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:90. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Donnell C.A., Higgins M., Chauhan R., Mullen K. “They think we’re OK and we know we’re not”. A qualitative study of asylum seekers’ access, knowledge and views to health care in the UK. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2007;7:75. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bischoff A., Bovier P.A., Rrustemi I., Gariazzo F., Eytan A., Loutan L. Language barriers between nurses and asylum seekers: Their impact on symptom reporting and referral. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003;57:503–512. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00376-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zander V., Müllersdorf M., Christensson K., Eriksson H. Struggling for sense of control: Everyday life with chronic pain for women of the Iraqi diaspora in Sweden. Scand. J. Public Health. 2013;41:799–807. doi: 10.1177/1403494813492033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schein Y.L., Winje B.A., Myhre S.L., Nordstoga I., Straiton M.L. A qualitative study of health experiences of Ethiopian asylum seekers in Norway. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019;19:958. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4813-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mangrio E., Carlson E., Zdravkovic S. Understanding experiences of the Swedish health care system from the perspective of newly arrived refugees. BMC Res. Notes. 2018;11:616. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3728-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mårtensson L., Lytsy P., Westerling R., Wångdahl J. Experiences and needs concerning health related information for newly arrived refugees in Sweden. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1044. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09163-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Razavi M.F., Falk L., Björn Å., Wilhelmsson S. Experiences of the Swedish healthcare system: An interview study with refugees in need of long-term health care. Scand. J. Public Health. 2011;39:319–325. doi: 10.1177/1403494811399655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jensen N.K., Johansen K.S., Kastrup M., Krasnik A., Norredam M. Patient experienced continuity of care in the psychiatric healthcare system-a study including immigrants, refugees and ethnic danes. Int J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2014;11:9739–9759. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110909739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feldmann C.T., Bensing J.M., de Ruijter A. Worries are the mother of many diseases: General practitioners and refugees in the Netherlands on stress, being ill and prejudice. Patient Educ. Couns. 2007;65:369–380. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O’Donnell C.A., Higgins M., Chauhan R., Mullen K. Asylum seekers’ expectations of and trust in general practice: A qualitative study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2008;58:e1–e11. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X376104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Feldmann C.T., Bensing J.M., de Ruijter A., Boeije H.R. Afghan refugees and their general practitioners in The Netherlands: To trust or not to trust. Sociol. Health Illn. 2007;29:515–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blöchliger C., Osterwalder J., Hatz C., Tanner M., Junghanss T. Asylum seekers and refugees in the emergency department. Soz. Prav. 1998;43:39–48. doi: 10.1007/BF01299239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pollard T., Howard N. Mental healthcare for asylum-seekers and refugees residing in the United Kingdom: A scoping review of policies, barriers, and enablers. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2021;15:60. doi: 10.1186/s13033-021-00473-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Munz D., Melcop N. The psychotherapeutic care of refugees in Europe: Treatment needs, delivery reality and recommendations for action. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2018;9:1476436. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2018.1476436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Karliner L.S., Jacobs E.A., Chen A.H., Mutha S. Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Serv. Res. 2007;42:727–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Griswold K.S., Pottie K., Kim I., Kim W., Lin L. Strengthening effective preventive services for refugee populations: Toward communities of solution. Public Health Rev. 2018;39:3. doi: 10.1186/s40985-018-0082-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith Jervelund S., Maltesen T., Wimmelmann C.L., Petersen J.H., Krasnik A. Ignorance is not bliss: The effect of systematic information on immigrants’ knowledge of and satisfaction with the Danish healthcare system. Scand. J. Public Health. 2017;45:161–174. doi: 10.1177/1403494816685936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marmot M., Friel S., Bell R., Houweling T.A., Taylor S. Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2008;372:1661–1669. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rechel B., Mladovsky P., Ingleby D., Mackenbach J.P., McKee M. Migration and health in an increasingly diverse Europe. Lancet. 2013;381:1235–1245. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen W., Hall B.J., Ling L., Renzaho A.M. Pre-migration and post-migration factors associated with mental health in humanitarian migrants in Australia and the moderation effect of post-migration stressors: Findings from the first wave data of the BNLA cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:218–229. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in the published article.