Abstract

This article comments on:

Vladimir Y. Gorshkov, Yana Y. Toporkova, Ivan D. Tsers, Elena O. Smirnova, Anna V. Ogorodnikova, Natalia E. Gogoleva, Olga I. Parfirova, Olga E. Petrova, and Yuri V. Gogolev, Differential modulation of the lipoxygenase cascade during typical and latent Pectobacterium atrosepticum infections, Annals of Botany, Volume 129, Issue 3, 16 Februray 2022, Pages 271–285 https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcab108

Keywords: Lipoxygenase pathway, Pectobacterium atrosepticum, typical and latent infections

In this issue of the Annals of Botany, Gorshkov et al. report altered oxylipin signatures between typical and latent infections of tobacco plants with the necrotrophic pathogen Pectobacterium atrosepticum. Resistance against necrotrophic pathogens is mediated by jasmonic acid (JA), whereas resistance to biotrophic pathogens is caused by salicylic acid (SA) (Pieterse et al., 2012). Many phytopathogenic micro-organisms including Pectobacterium cause asymptomatic (latent) interactions without disease symptoms for long periods, but which can turn to disease after several host plant life cycles, causing cell wall degradation due to production of degrading enzymes. Pectobacterium can form coronafacic acid (CA), a constituent of the phytotoxin coronatine, a functional analogue of jasmonates that is also produced as a multifunctional suppressor of defence by Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC 3000, the system in which the characterization of coronatine action has been most fully developed (Geng et al., 2012; Xin and He, 2013). The link between jasmonates and CA has been further demonstrated by the finding that the first and most prominent JA-insensitive mutant in Arabidopsis was identified as a coronatine-insensitive mutant (coi1, Xie et al., 1998).

Jasmonic acid and its derivatives are formed within the lipoxygenase (LOX) pathway. There are seven different branches of the LOX pathway contributing to the metabolism of lipid constituents such as α-linolenic acid (α-LeA) and linoleic acid (LA). Among these branches are the allene oxide synthase (AOS) branch, the hydroperoxide lyase (HPL) branch, the divinyl ether synthase (DES) branch and the epoxyalcohol synthase (EAS) branch (Wasternack and Feussner, 2018). In the AOS branch, the action of allene oxide cyclase (AOC) leads to cis-12-oxo-phytodienoic acid (OPDA), which is reduced by the OPDA reductase (OPR) and subsequently shortened in the carboxylic acid side chain by the fatty acid β-oxidation machinery to JA (Wasternack and Hause, 2013). OPDA, JA and JA derivatives are important signals of plant stress responses and plant development (Wasternack and Hause, 2013).

A key trait of the LOX pathway is its activation upon external stimuli such as wounding or pathogen infection, with differential effects on the various branches. This leads to a distinct profile of LOX-catalysed lipid-derived compounds, so-called oxylipins. The profile is essentially determined by positional specificity of oxygen insertion within the substrates α-LeA and LA catalysed by LOX enzymes. We can distinguish two principal categories of LOX: 9-LOXs, with oxygen insertion at carbon atom 9, and 13-LOXs, which oxygenate at C-13. Consequently, the various LOX branches lead to 9- and 13-products formed in the cytosol (9-LOXs) and the chloroplasts (13-LOXs), respectively (Wasternack and Feussner, 2018).

Plants respond to bacterial or fungal infection with the activation of the LOX pathway and distinct pattern of oxylipins. The term ‘oxylipin signature’ was proposed for any characteristic profile of oxylipins (Weber et al., 1997) and describes a typical feature in the LOX-derived profile upon pathogen infection. Examples for the specific accumulation of 13- LOX or 9-LOX-products are: (1) the fungal infection of maize, e.g. with Fusarium graminearum, leads to reduced levels of 9-oxylipins and reduced expression of 9-LOX genes compared with jasmonates and expression of 13-LOX genes, whereas resistant lines show an inverse ratio (Wang et al. 2021); (2) the symptom-less infection of potato with the phytopathogenic bacterium Pseudomonas syringae pv. maculicula leads to few 13-LOX-derived products and preferential 9-LOX-derived metabolites, whereas infection with the oomycete Phytopthora infestans does not lead to activation of the 13-LOX-derived oxylipins at all (Göbel et al., 2002).

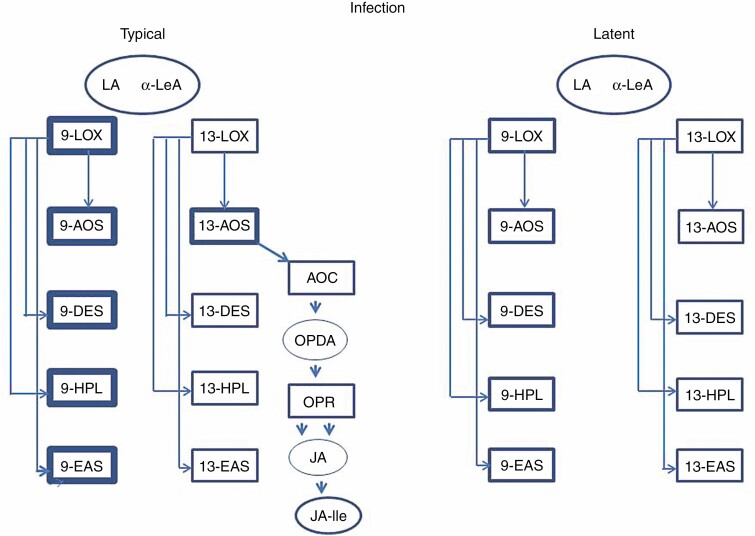

In the study of Gorshkov et al. (2021), initial expression of 13-LOX and 9-LOX genes following infection consisted of the induction of six of the twelve 13-LOX annotated genes and twelve of the nineteen 9-LOX annotated genes. Among the induced 9-LOX genes, only three were expressed by both typical and latent infections, but interestingly ten times more highly expressed upon typical infection than upon latent infection. This clearly greater extent of expression of 9-LOX genes than that of 13-LOX genes was recorded mainly for typical infection. This suggests specific differences among the LOX-derived products (Fig. 1). Indeed, the distinct oxylipin signatures for both types of infection were correlated to corresponding differences in the expression of genes encoding HPLs, DESs, AOSs, AOCs and OPRs, several of them with higher expression during typical infection.

Fig. 1.

Scheme of the reactions in the lipoxygenase (LOX) pathway during typical and latent infection by Pectobacterium atrosepticum. Linoleic acid (LA) or α-linolenic acid (α- LeA) can be converted by 9-LOX or 13-LOX followed by reactions of 9- or 13-allene oxide synthase (AOS), by 9- or 13-divinyl ether synthase (DES), by 9- or 13- hydroperoxide lyase (HPL) or by 9- or 13-epoxyalcohol synthase (EAS). 12-Oxophytodienoic acid (OPDA) is formed within the AOS branch by allene oxide cyclase (AOC) and further converted by several enzymes including OPDA reductase (OPR) to jasmonic acid (JA), which is conjugated with amino acids (e.g. isoleucine) to the most active JA compound. The thickness of the frames indicates the degree of expression of corresponding genes and degree of accumulation of compounds. There is clearly a preferential expression of genes of the 9-LOX pathway in typical infections.

To complete the picture of JA biosynthesis gene activity, the authors looked at expression of components of JA signalling: the authors compared expression of genes coding for the transcriptional activator MYC2 and transcriptional repressors JAZs in typical and latent infections. Although redundancy of MYC2 with MYC3 and MYC4 as well as among the JAZs was not taken into account, the data clearly show higher expression of MYC2 and JAZ genes in typical infection compared with latent infection. Such patterns of expression of genes of JA biosynthesis, the LOX pathway and genes active in JA signalling suggest generation of distinct products of 9-LOX and 13-LOX enzymes and the subsequent target enzymes AOS, HPL, EAS and DES. Indeed, upon typical infection, activities of 9-LOX enzymes were clearly higher than those of 13-LOX-related enzymes. In summary, the 9-LOX pathway, expression of genes encoding 9-LOX, 9-AOS, 9-HPL, 9-DES and 9-EAS, as well as activity of the corresponding enzymes were induced were induced compared with non-infected plants. In contrast, only the activity of enzymes of the 13-AOS branch increased among the 13-LOX pathway components.

An apparent contradiction was found by lack of a co-ordinated increase of enzyme activity and accumulation of the corresponding products for some reactions, e.g. the 13-AOS branch products JA and OPDA were below the detection limit. This might be due to the conversion of JA into downstream products, such as the isoleucine conjugate (Fig. 1). The physiological activity of JA, however, was unchanged: upon typical infection, upregulation of JA-responsive genes including those of JA signalling took place, suggesting that any possibly transient increase in JA levels was sufficient to switch on gene expression. Finally, an interesting dual enzyme specificity was found by identification of the first tobacco HPL with EAS activity. The protein encoded by the LOC107825278 gene was shown to form aldehydes and aldoacids as typical HPL products and oxiranyl carbinols as characteristic EAS products.

In summary, the article by Gorshkov et al. (2021) demonstrates that the oxylipin signature provides a powerful heuristic for unravelling the plant–pathogen interactions that determine whether a given infection event proceeds along a latent or symptomatic trajectory.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I thank B. Hause (IPB, Halle, Germany) for critical reading and comments.

FUNDING

The work was supported by the Czech Grant Agency, project No. 19-10464Y and from ERDF project ‘Plants as a tool for sustainable global development’ (No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_019/0000827).

LITERATURE CITED

- Geng X, Cheng J, Gangadharan A, Mackey D. 2012. The coronatine toxin of Pseudomonas syringae is a multifunctional suppressor of Arabidopsis defense. The Plant Cell 24: 4763–4774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göbel C, Feussner I, Hamberg M, Rosahl S. 2002. Oxylipin profiling in pathogen-infected potato leaves. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1584: 55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorshkov V, Toporkova Y, Tsers I, et al. 2022. Differential modulation of lipoxygenase cascade during typical and latent Pectobacterium atrosepticum infections. Annals of Botany 129: 271–285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse CM, Van der Does D, Zamioudis C, Leon-Reyes A, Van Wees SC. 2012. Hormonal modulation of plant immunity. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 28: 489–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Sun Y, Wang F, et al. 2021. Transcriptome and oxylipin profiling joint analysis reveals opposite roles of 9-oxylipins and jasmonic acid in maize resistance to gibberella stalk rot. Frontiers in Plant Science 12: 699146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasternack C, Feussner I. 2018. The oxylipin pathways: biochemistry and function. Annual Review of Plant Biology 69: 363–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasternack C, Hause B. 2013. Jasmonates: biosynthesis, perception, signal transduction and action in plant stress response, growth and development. An update to the 2007 review in Annals of Botany. Annals of Botany 111: 1021–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber H, Vick BA, Farmer EE. 1997. Dinor- oxo-phytodienoic acid: a new hexadecadienoic signal in the jasmonate family. Proceedings of the Natiional Academy of Sciences, USA 94: 10473–10478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie DX, Feys BF, James S, Nieto-Rostro M, Turner JG. 1998. COI1: an Arabidopsis gene required for jasmonate-regulated defense and fertility. Science 280: 1091–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin XF, He SY. 2013. Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000: a model pathogen for probing disease susceptibility and hormone signaling in plants. Annual Review of Phytopathology 51: 473–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]