Abstract

This study assessed the effects of a diet containing avocado meal (AMD), an underutilized by-product avocado oil processing, on apparent total tract digestibility (ATTD) and fecal fermentative end-products when compared with beet pulp (BPD) and cellulose (CD) diets targeting 15% total dietary fiber (TDF). The concentration of persin, a natural fungicidal toxin present in avocado, was also determined on several parts of the fruit and avocado meal. Nine intact female beagles (4.9 ± 0.6 yr and 11.98 ± 1.76 kg) were randomly grouped in a 3 × 3 replicated Latin square design. Periods were 14 d long, with 10 d of adaptation followed by 4 d of total fecal and urine collection for apparent total tract digestibility (ATTD) calculations. Fresh fecals were analyzed for fermentative end-products. The BPD (87.0 g/d) caused higher (P < 0.05) fecal output (as-is basis) than AMD (62.3 g/d) and CD (58.0 g/d). Fecal score for the BPD (3.1) was greater (P < 0.05) than for AMD (2.8) or CD (2.6). Acid-hydrolyzed fat ATTD was lower (P < 0.05) for the BPD (94.1%) than for the AMD (95.5%) and CD (95.7%). Crude protein ATTD was greater (P < 0.05) for the CD (88.5%) than the AMD (82.2%) or BPD (83.7%). Dogs fed AMD (49.9%) or BPD (51.0%) exhibited greater (P < 0.05) TDF ATTD than CD. The fermentative profile for the AMD (233.4, 70.9, 8.8, and 12.0 μmole/g DM, respectively) was similar (P > 0.05) to the CD (132.9, 61.7, 7.5, and 9.5 μmole/g DM, respectively) profile, with lower (P < 0.05) concentrations of acetate and propionate and higher (P < 0.05) concentrations of isovalerate and indoles compared to the BPD. Dogs fed AMD (47.0 μmole/g DM) or BPD (54.2 μmole/g DM) exhibited similar (P > 0.05) fecal butyrate concentrations greater (P < 0.05) than for CD (24.7 μmole/g DM). Given these results, avocado meal appears to be an adequate dietary fiber source when compared with traditional fiber sources used in canine diets. No health adverse effects were observed in dogs fed extruded diet containing as much as 18% of avocado meal (as-is basis).

Keywords: by-product, dog, digestibility, extrusion, fecal metabolites, Persea americana, persin

Introduction

Avocado (Persea americana) meal is an underutilized by-product of the avocado oil processing industry. Even though there is no published research on feeding a diet containing avocado meal to dogs, pet owners are told that avocados are poisonous and should not be fed. This information comes from veterinary case studies, including only one with dogs (Buoro et al., 1994). Studies testing avocado meal or defatted avocado pulp have found that it is a suitable fiber source and can affect blood cholesterol levels, digestibility of nutrients, and feed efficiency. However, all of this work was done with rats (Naveh et al., 2002), sheep (Skenjana et al., 2006), and broiler chickens (van Ryssen et al., 2013) and, therefore, is not directly applicable to dogs. In addition, none of these studies have addressed the potential impact avocado meal may have on gastrointestinal fermentation, which relates to the dietary fiber source used in canine diets and may have implications for gut health.

Persin, a fatty acid derivative, is synthesized in idioblast oil cells present in the avocado fruit and leaves with suggested insecticidal and fungicidal activity (Oberlies et al., 1998; Rodriguez-Saona and Trumble, 2000). Persin is classified as an acetogenin, derived from the biosynthesis of long-chain fatty acids and with similar structure of linoleic acid (Butt et al., 2006). In vitro, persin has shown cytotoxic and proapoptotic effects in human breast cancer cell lines (Butt et al., 2006; Ding et al., 2007; Brooke et al., 2011). In contrast with the human literature, consumption of avocado by small ruminant (goats and sheep) and monogastric animal species (avians, reptiles, dogs, and cats) is discouraged, due to acute signs of toxicity (i.e., labored breathing, decreased appetite, lethargy, congestion in the lungs, cardiomyopathy, and nephrosis) and eventual death. The toxic effects of avocado have been attributed to the presence of persin, even though this compound has not been quantified in any of those studies.

This study’s objective was to compare avocado meal to beet pulp and cellulose, traditional fiber sources in diets for canines, to determine the concentration of persin in various parts of the avocado fruit and avocado meal, and its potential for use in the pet food industry. We hypothesized that avocado meal would not negatively impact ATTD of macronutrients or would exert similar physiological effects of beet pulp due to comparable ratio of soluble to insoluble dietary fiber fractions of these ingredients.

Materials and Methods

Ingredient and fatty acid analysis

The avocado meal utilized in this study was sourced from Green Source Organics, Boynton Beach, FL. The nutrient composition of avocado meal was determined as described under the chemical analyses section. The fatty acid profile of avocado meal was also determined by weighing out 0.1 g samples in duplicate to begin the analysis. The internal standard (nonadecanoic acid, 19:0) and external fatty acid methyl ester standards were purchased from Supelco Sigma–Aldrich. The internal standard was dissolved in methanol-butylated hydroxytoluene solution (50 µg/mL methanol) at a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL. The internal standard solution (50 µL) was added to test tubes containing 2 mL of methanol-hexane (4:1, v/v) mixture, vortexed, and placed on ice. Acetyl chloride (200 µL) was slowly added dropwise into the tubes and then capped under nitrogen. The samples were heated for 10 min at 100 °C, vortexed briefly, and returned to be heated for another 50 min. After heating, the tubes were placed on ice and allowed to cool. They were then neutralized by adding 5 mL of a 6% Na2CO3 solution. The tubes were vortexed for 1 min and centrifuged at 2300 rpm for 3 min to separate the mixture into two phases. The upper organic phase was collected into a new test tube and the extraction was repeated once more by adding 0.5 mL of hexane, vortex, and centrifuged for another 3 min. The organic phase was collected again and combined with the first extraction. The combined extraction was evaporated under nitrogen to 300 µL, then transferred to a gas chromatograph (GC) vial with a 300-µL glass insert, and crimped under nitrogen for fatty acid methyl ether analysis by GC.

Thermo Scientific TRACE 1300 gas chromatograph coupled with flame ionization detector was used for analyzing individual fatty acid methyl ether. Exacts (1 µL) were injected into GC and separated on a fused silica capillary column (SP-2560, 100 m length, 0.25 mm I.D., 0.2 um film thickness). The carrier gas was helium, and the flow rate was 20 cm/s, at a split ratio of 100:1. The temperature was at 140 °C initially for 5 min, then increased at 4 °C/min to a final temperature of 240 °C, and held for 15 min. The temperatures for the injector and detector were 250 and 260 °C, respectively.

Several avocados were purchased from local grocery stores and processed in our laboratory to separate the pulp, pit, and peel. These fruit parts were then lyophilized (Labconco FreeZone, LABCONCO, Kansas City, MO). The freeze-dried samples were then ground to a fine powder using a porcelain mortar and pestle, and analyzed for persin [(Z,Z)-1-acetyloxy-2-hydroxy-12,15-heneicosadien-4-one] concentration. Remaining freeze-dried samples were stored at −80 °C.

Persin synthesis, extraction, and analysis

The synthesis of persin was carried out according to the method described by Oelrichs et al. (1995). Ingredient and food samples were soaked in high-performance liquid chromatography-grade methanol for 15 h at −20 °C and then extracted twice with 1 mL of methanol after sonication for 5 min. All methanol extract were collected and combined, then centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 10 min, and passed through a 0.2-µm Nylon syringe filter. The filtered extracts were then diluted 10 times and stored at −20 °C for MS analysis. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry was used to quantify (+)-persin content on a Shimadzu Nexera XR UHPLC system with an SPD-M30A UV/VIS Photodiode array detector and an LC-MS 2020 mass spectrometer. Chromatographic separation was done on a Kinetex 1.7 μm Evo C18 100 Å 50 mm column with a binary gradient from 20% to 90% MeCN in water over 2 min, then 90% to 95% over 2 min at 0.4 mL/min, then 95% to 20% MeCN in water over 0.1 min, and then held at 20% for 1.4 min. Detection was done with selected ion monitoring with electrospray ionization on Shimadzu LCMS-2020 instrument. Signal intensities correspond to integrated ion count traces. Five-point linear calibration curve was built at concentrations of 10, 25, 50, 75, and 100 µM. This standard curve was used to calculate concentration of persin from the sample extracts based on their peak area.

Animals

All animal procedures were approved by the University of Illinois Institutional Animal Care and Use committee (IACUC protocol No.: 16099). All methods were performed in accordance with the United States Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Nine intact female Beagles (4.9 ± 0.6 yr, 11.98 ± 1.76 kg, and 6.72 ± 1.18 body condition score) were used in a replicated 3 × 3 Latin square design. Each period consisted of 10 d of diet adaptation and 4 d of total fecal and urine collection. Dogs were housed individually (1.2 × 1.8 m) with free access to water. They were fed twice daily at 0800 and 1600 h and had access to food until the next feeding time when food refusals, if present, were collected and recorded. All dogs were fed to maintain their daily metabolizable energy requirements based on previous records of daily food intake and energy intake requirements for each dog in our colony. During the collection phase, dogs were housed individually in metabolic cages and given the same access to food and water.

Diets

Three diets were formulated to meet the Association of American Feed Control Officials (2016) nutritional requirements for adult dogs with similar macronutrient targets and bulk densities ranging from 350 to 370 g/L; a common bulk density target for commercial extruded canine diets. The avocado meal ingredient was obtained from Green Source Organics Natural Extracts (Boynton Beach, FL), all other dry ingredients from Lortscher Animal Nutrition (Bern, KS), and choice white grease from the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign Feed Mill (Champaign, IL). The total dietary fiber (TDF) source for each diet was either avocado meal (AMD), beet pulp (BPD), or cellulose (CD). Diets were manufactured at the Kansas State University Bioprocessing and Industrial Value Added Products Innovation Center (Manhattan, KS) and coated with an additional 4% choice white grease (University of Illinois Feed Mill, Champaign, IL) and 2% palatant (AFB International bioflavor #F25003, St. Charles, MO). Dogs were fed to maintain body weight and body condition score, which were measured once a week during the study periods.

Acceptability testing

Acceptability of the AMD without the second coating of choice white grease and palatant was determined by Kennelwood, Inc. (Champaign, IL) using a one-bowl monadic test. Twenty dogs (13.81 ± 3.90 kg) were offered 400 g/d for 2 d. Daily food intake was calculated by subtracting food refusals from the offered food.

Sample collection

During the collection phase, all feces were collected from each dog for macronutrient analysis. Fecal weight (as-is) and fecal score using a 5-point scale (1 = hard, dry pellets; small hard mass; 2 = hard formed, remains firm and soft; 3 = soft, formed and moist stool, retains shape; 4 = soft, unformed stool; assumes shape of container; 5 = watery, liquid that can be poured) were recorded for each sample. Samples were frozen at −20 °C for analysis at a later time. Total urine output volume after acidifying with 2N hydrochloric acid also was recorded and approximately 25% of each sample was saved for further analysis. Samples from each dog were stored in separate containers and frozen at −20 °C.

One fecal sample from each dog was collected within 15 min of defecation and analyzed for dry matter (DM), phenols and indoles, short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), and branched-chain fatty acids (BCFA). A pH reading, fecal score, and total sample weight also were taken. Dry matter was measured by drying approximately 2 grams (g) of feces in duplicate in a 105 °C oven until all moisture was removed. Approximately 2 g of feces in duplicate were stored in plastic tubes covered in parafilm and frozen at −20 °C for subsequent indole and phenol analyses. Finally, 5 g of sample were stored in Nalgene bottles containing 5 milliliters (mL) of 2N hydrochloric acid and frozen at −20 °C to determine SCFA, BCFA, and ammonia concentrations.

Eight millimeters of blood were collected from each dog on 14 d of each collection period. One milliliter was saved for plasma analysis and the remaining 7 mL were used for serum chemistry. All blood analyses were done by the Clinical Pathology group at the University of Illinois College of Veterinary Medicine (Urbana, IL).

Chemical analyses

Diets were subsampled and ground in a Wiley mill with a 10 mesh [2 millimeter (mm)] screen size. Fecal samples from each dog and period were pooled together and dried in a 57 °C oven before grinding in the Wiley Mill with a 10 mesh (2 mm) screen size. These materials were used for macronutrient concentrations. Dry matter, organic matter (OM), and ash were determined for the diets and feces using the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC, 2006; methods 934.01 and 942.05). Acid-hydrolyzed fat (AHF) in the diet and feces was done following methods of the American Association of Cereal Chemists (AACC, 1983), and Budde et al. (1952). Crude protein (CP) analysis was done by measuring total nitrogen using a LECO TruMac (model 630-300-300) and following the Official Method of AOAC International (2006). Gross energy of diets, feces, and urine were measured using a Parr 6200 calorimeter (Parr Instrument Company, Moline, IL). Total dietary fiber (TDF) was analyzed according to Prosky et al. (1992) and the Official Method of AOAC International, 2006 (Methods 985.29 and 991.43).

Short-chain fatty acids and BCFA were analyzed using gas chromatography with a glass 6ʹ × 1/4″ ODx4mmID column and 10%SP1200/1%H3PO4 on 80/100 Chrom-WAW, Supleco packing and following the methods of Erwin et al. (1961) and Goodall and Byers (1978). Gas chromatography also was used to measure phenols and indoles as cited in Flickinger et al. (2003). Ammonia concentration was determined using the methods of Chaney and Marbach (1962).

Physical analyses

Ten kibbles of the AMD, BPD, and CD were weighed individually on an analytical scale (model #AG104, Mettler Toledo, Switzerland). Digital calipers (model #01407A, Neiko Tools, China) were used to determine radial diameter and piece length. From these measurements, piece volume, piece density, sectional expansion index (SEI), and specific length were calculated using equations 1–4. Replicates of each diet were averaged and sample standard deviation was calculated.

Equation 1: Piece volume formula

Equation 2: Piece density formula

Equation 3: Sectional expansion index (SEI) formula

Equation 4: Specific length formula

A texture analyzer (TA HD plus; Texture Technologies Corporation, Scarsdale, NY) equipped with a 30 kg load cell and a 50.8 mm cylindrical probe (TA-15) was used to compress 10 kibbles per diet by 50%. Pre-test, test, and post-test speed settings were 2, 1, and 10 mm/s, respectively. Data were collected using Texture Expert Exceed software (Stable Micro Systems, Godalming, England). Peak force [greatest force measurement, Newton (N)] and energy required for compression [area under the curve, Newton x millimeter (Nxmm)] were calculated from time vs. force graphs. This method was slightly modified from Dogan et al. (2007). Duplicates for each diet and processing stage combination were averaged together and standard deviation was calculated.

Three-dimensional images of kibbles were taken using a Rigaku CT Lab GX130 (The Woodlands, TX) with a current of 60 kV and 133 µA. Ten kibbles from each processing stage and diet were scanned at once for 57 min. Pixel size is 0.9 cubic millimeters (mm3). Kibbles in each image were isolated and ScanIP (Synopsys Inc., Mountain View, CA) was used to create 3D masks based on brightness to determine the volume of the kibble vs. the volume of solid material in the kibble. Volume of air contained within the kibble was determined by subtracting the volume of solid material from the total volume of the kibble.

Calculations

Digestibility of individual macronutrients was calculated by subtracting the nutrient content of the feces from the nutrient content of food consumed, dividing by the nutrient content of the food consumed, and multiplying by 100. Nutrient content of feces and diet was determined by multiplying the feces or diet (g, DM basis) by the corresponding nutrient percentage. Digestible energy was calculated by subtracting the energy contained in the feces from the energy contained in the diet. Metabolizable energy was determined by subtracting the energy contained in the urine from the digestible energy.

Statistical analysis

Data were compared using SAS, version 9.4, using a mixed model. The statistical model included the fixed effect of diet and the random effect of animal. Data normality was checked using the UNIVARIATE procedure of SAS. All treatment least-square means were compared with each other and Tukey adjustment was used to control for experiment-wise error. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically different.

Results

Chemical composition of avocado meal is presented in Table 1. Dry matter and OM concentrations were high, both above 90%. This ingredient also had a high concentration of TDF of 37.4% (DM basis), with approximately 73% of the TDF content being comprised of insoluble fiber. Oleic acid was the most abundant fatty acid in the avocado meal (849.3 µg/g), followed by linoleic (280.6 µg/g), palmitoleic (82.4 µg/g), palmitic (55.6 µg/g), linolelaidic (44.6 µg/g), α-linolenic (38.8 µg/g), and stearic acids (11.5 µg/g). Persin concentration was highest in avocado peel (720 µg/g), intermediate in the pulp (110.1 µg/g), and pit (98.7 µg/g), and not present at detectable concentration (10 µM) in avocado meal (Table 2).

Table 1.

Chemical composition of avocado meal ingredient

| Item | |

|---|---|

| Dry matter, % | 94.1 |

| % DM basis | |

| Organic matter | 91.0 |

| Ash | 9.0 |

| Acid hydrolyzed fat | 9.1 |

| Crude protein | 11.5 |

| Total dietary fiber | 37.4 |

| Soluble dietary fiber | 10.4 |

| Insoluble dietary fiber | 27.0 |

| Gross energy, kcal/g | 4.9 |

| Fatty acid composition, µg/g, DMB | |

| C16:0 (Palmitic) | 55.6 |

| C16:1 (Palmitoleic) | 82.4 |

| C18:0 (Stearic) | 11.5 |

| C18:1n9c (Oleic) | 849.3 |

| C18:2n6c (Linoleic) | 280.6 |

| C18:2n6t (Linolelaidic) | 44.6 |

| C18:3n3 (α-Linolenic) | 38.8 |

Table 2.

Persin concentration of avocado fruit parts and avocado meal

| Item | Concentration (µg/g) |

|---|---|

| Avocado pulp | 110.1 |

| Avocado pit | 98.7 |

| Avocado peel | 720.7 |

| Avocado meal | ND |

Ingredients and their inclusion levels were similar among dietary treatments (Table 3). Avocado meal and beet pulp replaced cellulose and chicken by-product meal and brewer’s rice. Choice-white grease inclusions were adjusted to maintain isonitrogenous and isocaloric nutrient compositions (Table 4). Small differences in AHF were observed, with CD (18.5%, DM basis) being the greatest, followed by AMD (17.8%, DM basis) and BPD (17.0%, DM basis). The treatments also had different IDF:SDF ratios.

Table 3.

Ingredient composition of dietary treatments with selected dietary fiber sources for adult canines

| Ingredient, % as-is | Treatments1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| AMD | BPD | CD | |

| Chicken by-product meal | 29.57 | 29.91 | 31.42 |

| Brewer’s rice | 26.81 | 27.17 | 31.61 |

| Choice white grease | 9.11 | 11.32 | 11.32 |

| Corn gluten meal | 7.66 | 7.74 | 7.74 |

| Whole corn | 3.83 | 3.87 | 3.87 |

| AFB bioflavor F25003 | 1.89 | 1.89 | 1.89 |

| Avocado meal | 18.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Beet pulp | 0.00 | 15.66 | 0.00 |

| Cellulose | 0.00 | 0.00 | 9.72 |

| AFB bioflavor B22006 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.89 |

| Salt | 0.48 | 0.47 | 0.47 |

| Potassium chloride | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.42 |

| Taurine | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| Mineral premix2 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 |

| Vitamin premix3 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 |

| Choline chloride | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

AMD, avocado meal diet; BPD, beet pulp diet; CD, cellulose diet.

Provided per kilogram of diet: 35.6 mg manganese (MnSO4), 601.4 mg iron (FeSO4), 29.6 mg copper (CuSO4), 0.02 mg cobalt (CoSO4), 326.3 mg zinc (ZnSO4), 2.9 mg iodine (KI), and 0.8 mg selenium (Na2SeO3).

Provided per kilogram of diet: 17000 IU vitamin A (retinyl acetate), 2550 IU vitamin D3, 136 IU vitamin E (DL-α tocopherol acetate), 3.3 mg vitamin K, 28.9 mg thiamin, 28.9 mg riboflavin, 51.7 mg pantothenic acid, 117.3 mg niacin, 28.9 mg pyridoxine, 0.1 mg biotin, 1.0 mg folic acid, and 1.1 mg vitamin B12 (mannitol).

Table 4.

Chemical composition of dietary treatments containing selected fiber sources for adult canines

| Item | Treatments1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| AMD | BPD | CD | |

| Dry matter, % | 95.3 | 93.4 | 95.2 |

| % DM basis | |||

| Organic matter | 91.3 | 91.8 | 92.8 |

| Ash | 8.7 | 8.2 | 7.2 |

| Acid hydrolyzed fat | 17.8 | 17.0 | 18.5 |

| Crude protein | 32.5 | 32.3 | 32.4 |

| Total dietary fiber | 17.7 | 18.1 | 19.5 |

| Soluble dietary fiber | 4.3 | 3.5 | 2.6 |

| Insoluble dietary fiber | 13.4 | 14.7 | 17.0 |

| Gross energy, kcal/g | 5.3 | 5.2 | 5.3 |

AMD, avocado meal diet; BPD, beet pulp diet; CD, cellulose diet.

Physical characteristics of the kibbles varied across dietary treatments (Table 5). Piece mass (AMD = 0.14 ± 0.01 g; BPD = 0.15 ± 0.01 g; CD = 0.12 ± 0.01 g) and piece length (AMD = 6.6 ± 0.6 mm; BPD = 6.7 ± 0.5 mm; CD = 6.7 ± 0.4 mm) were very similar. The AMD (7.8 ± 0.4 mm) had the largest piece diameter with BPD (6.8 ± 0.3 mm) and CD (6.5 ± 0.3 mm) being smaller. The same relationship was observed for piece volume (AMD = 0.32 ± 0.04 cm3; BPD = 0.25 ± 0.03 cm3; CD = 0.23 ± 0.03 cm3) and SEI (AMD = 3.8 ± 0.4; BPD = 2.9 ± 0.3; CD = 2.7 ± 0.3). The BPD (0.61 ± 0.05 g/cm3) had greater piece density, followed by CD (0.55 ± 0.07 g/cm3) and AMD (0.46 ± 0.05 g/cm3). On the other hand, AMD (4.6 ± 0.2 mm/g) and BPD (4.5 ± 0.1 mm/g) had similar specific length and were smaller than CD (5.5 ± 0.4 mm/g). The BPD had the lowest kibble hardness (32.4 ± 5.0 N) and energy to compress (24.8 ± 7.5 Nxmm), with AMD being very similar (48.4 ± 10.2 N and 35.9 ± 10.3 Nxmm, respectively) and CD being much higher than both (88.2 ± 7.7 N and 110.3 ± 18.3 Nxmm, respectively). Material percentage of kibbles from AMD (67.5% ± 5.2%) and BPD (68.9% ± 6.7%) were also similar and slightly lower than for CD (79.3% ± 8.3%), with the inverse true for air percentage of kibble (AMD = 32.5% ± 5.2%; BPD = 31.1% ± 6.7%; CD = 20.7% ± 8.3%).

Table 5.

Analyzed physical characteristics of extruded dietary treatments for adult canines containing selected dietary fiber sources

| Item | Treatments1 (Average ± Standard Deviation) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| AMD | BPD | CD | |

| Piece mass, g | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.01 |

| Piece diameter, mm | 7.8 ± 0.4 | 6.8 ± 0.3 | 6.5 ± 0.3 |

| Piece length, mm | 6.6 ± 0.6 | 6.7 ± 0.5 | 6.7 ± 0.4 |

| Piece volume, cm3 | 0.32 ± 0.04 | 0.25 ± 0.03 | 0.23 ± 0.03 |

| Piece density, g/cm3 | 0.46 ± 0.05 | 0.61 ± 0.05 | 0.55 ± 0.07 |

| Sectional expansion ratio | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 2.7 ± 0.3 |

| Specific length, mm/g | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 4.5 ± 0.1 | 5.5 ± 0.4 |

| Kibble hardness, N | 48.4 ± 10.2 | 32.4 ± 5.0 | 88.2 ± 7.7 |

| Energy to compress 50%, Nxmm | 35.9 ± 10.3 | 24.8 ± 7.5 | 110.3 ± 18.3 |

| Material, % of kibble volume | 67.5 ± 5.2 | 68.9 ± 6.7 | 79.3 ± 8.3 |

| Air, % of kibble volume | 32.5 ± 5.2 | 31.1 ± 6.7 | 20.7 ± 8.3 |

AMD, avocado meal diet; BPD, beet pulp diet; CD, cellulose diet.

There was no statistical difference (P > 0.05) in intakes of OM, AHF, CP, and gross energy for all dietary treatments (Table 6). Mean body weight of the dogs was not affected by treatment (P > 0.05), CD = 11.86 kg, BP = 11.80, and AMD 11.91, data not shown. The BPD (87.0 g/d as-is) resulted in greater (P < 0.05) daily fecal output on an as-is basis than the CD (58.0 g/d as-is) and the AMD (62.3 g/d as-is), but statistical differences disappeared (P > 0.05) when expressed on a DM basis (AMD = 27.6 g/d DM basis; BPD = 30.0 g/d DM basis; CD = 32.2 g/d DM basis). Average fecal score for dogs consuming BPD (3.1) was greater (P < 0.05) than for the CD (2.6) and the AMD (2.8). The CD (40.2%) also had the highest (P < 0.05) fecal DM content, followed by AMD (35.3%; P < 0.05), then BPD (30.4%; P < 0.05). Fecal pH for the CD (6.2) was higher (P < 0.05) than for the AMD (5.9) and BPD (5.5), which were not different from each other (P > 0.05). Apparent total tract digestibility (ATTD) of DM, OM, and GE was similar among dietary treatments (P > 0.05). Dogs consuming BPD (94.1% DM basis) exhibited lower (P < 0.05) AHF ATTD than those consuming CD (95.7% DM basis) or AMD (95.5% DM basis), which were not different from each other (P > 0.05). For CP ATTD, CD (88.5% DM basis) was higher (P < 0.05) than AMD (82.2% DM basis) and BPD (83.7% DM basis), which did not differ from each other (P > 0.05). Energy partitioning into digestible energy and metabolizable energy did not differ (P > 0.05) by dietary treatment.

Table 6.

Food intake, fecal characteristics, and total tract apparent macronutrient digestibility by adult canines fed dietary treatments containing select dietary fiber sources

| Item | Treatments1 | SEM2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMD | BPD | CD | ||

| Food intake, as-is | ||||

| Dry matter, g/d | 134.4 | 155.7 | 143.0 | 13.61 |

| Organic matter, g/d | 135.9 | 142.9 | 141.1 | 7.57 |

| Acid hydrolyzed fat, g/d | 26.5 | 26.5 | 28.2 | 1.44 |

| Crude protein, g/d | 48.4 | 50.4 | 49.3 | 2.67 |

| Total dietary fiber, g/d | 27.3 | 28.3 | 29.6 | 1.40 |

| Soluble dietary fiber, g/d | 6.6a | 5.4b | 3.8c | 0.26 |

| Insoluble dietary fiber, g/d | 20.7b | 22.8b | 25.8a | 1.14 |

| Gross energy, kcal/d | 781.6 | 810.5 | 805.9 | 43.15 |

| Fecal output, g/d (as-is) | 62.3b | 87.0a | 58.0b | 8.30 |

| Fecal output, g/d (DMB) | 27.6 | 30.0 | 32.2 | 2.11 |

| Fecal score | 2.8b | 3.1a | 2.6b | 0.10 |

| Fecal DM % | 35.3b | 30.4c | 40.2a | 1.39 |

| Fecal pH | 5.9b | 5.5b | 6.2a | 0.10 |

| Digestibility, % | ||||

| Dry matter | 81.7 | 80.8 | 79.5 | 1.75 |

| % DM basis | ||||

| Organic matter | 84.5 | 84.3 | 81.9 | 0.94 |

| Acid hydrolyzed fat | 95.5a | 94.1b | 95.7a | 0.39 |

| Crude protein | 82.2b | 83.7b | 88.5a | 1.29 |

| Total dietary fiber | 49.9a | 51.0a | 33.5b | 3.01 |

| Energy | 85.3 | 85.6 | 80.0 | 0.85 |

| Digestible energy, kcal/g | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 0.04 |

| Metabolizable energy, kcal/g | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 0.04 |

AMD, avocado meal diet; BPD, beet pulp diet; CD, cellulose diet, n = 9.

Pooled standard error of means.

Superscripts with different letters in a row represent statistical differences (P < 0.05).

Consuming the BPD (672.7 and 480.5 μmole/g DM, respectively) resulted in the greatest (P < 0.05) total SCFA and acetate concentrations, with AMD (351.0 μmole/g DM and 233.4 μmole/g DM, respectively) and CD (219.0 μmole/g DM and 132.9 μmole/g DM, respectively) not different from each other (P > 0.05; Table 7). The concentration of butyrate was lowest (P < 0.05) for dogs consuming CD (24.7 μmole/g DM), and AMD (47.0 μmole/g DM) and BPD (54.2 μmole/g DM) were the same (P > 0.05). The BPD (138.0 μmole/g DM) resulted in the greatest (P < 0.05) propionate concentration, whereas AMD (70.9 μmole/g DM) and CD (61.7 μmole/g DM) were lower and not statistically different from each other (P > 0.05). Total BCFA concentration was not impacted (P > 0.05) by dietary treatment, but individual compounds were. Statistical differences were observed in the concentration of isovalerate, with AMD (8.8 μmole/g DM) and CD-fed dogs (7.5 μmole/g DM) being similar (P > 0.05) to each other, but greater (P < 0.05) than BPD-fed dogs (5.6 μmole/g DM). Valerate concentration for dogs consuming BPD (1.0 μmole/g DM) was greater (P < 0.05) than CD (0.5 μmole/g DM), and AMD (0.8 μmole/g DM) was not different (P > 0.05) from either. Concentrations of fecal indole and total indole and phenol exhibited the same relationship, with AMD (12.0 μmole/g DM and 12.1 μmole/g DM, respectively) and CD (9.5 μmole/g DM and 9.9 μmole/g DM, respectively) being similar (P > 0.05) but higher (P < 0.05) than BPD (2.9 μmole/g DM and 2.9 μmole/g DM, respectively). Ammonia concentrations for CD (132.9 μmole/g DM) were higher (P < 0.05) than for the BPD (90.7 μmole/g DM), with AMD (109.3 μmole/g DM) being intermediate (P > 0.05).

Table 7.

Fecal fermentative-end products for adult canines fed dietary treatments with selected dietary fiber sources

| Item, μmole/g DM | Treatments1 | SEM2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMD | BPD | CD | ||

| Total short-chain fatty acids | 351.0b | 672.7a | 219.0b | 40.55 |

| Acetate | 233.4b | 480.5a | 132.9b | 32.21 |

| Butyrate | 47.0a | 54.2a | 24.7b | 3.28 |

| Propionate | 70.9b | 138.0a | 61.7b | 8.09 |

| Total branched-chain fatty acids | 14.7 | 9.9 | 14.2 | 2.14 |

| Isobutyrate | 5.0 | 3.3 | 5.0 | 0.41 |

| Isovalerate | 8.8a | 5.6b | 7.5a | 0.90 |

| Valerate | 0.8a,b | 1.0a | 0.5b | 0.09 |

| Ammonia | 109.3a,b | 90.7b | 132.9a | 10.60 |

| Total indoles and phenols | 12.1a | 2.9b | 9.9a | 1.37 |

| Indole | 12.0a | 2.9b | 9.5a | 1.33 |

| Phenol | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.12 |

AMD, avocado meal diet; BPD, beet pulp diet; CD, cellulose diet; n = 9.

Pooled standard error of means.

Superscripts with different letters in a row represent statistical differences (P < 0.05).

Many serum metabolites were not impacted (P > 0.05) by the dietary treatments and few were outside the reference range for healthy adult dogs (Table 8). Albumin levels were within reference ranges, but were greatest (P < 0.05) for dogs fed AMD (3.3 mg/dL), lowest for those fed CD (3.2 mg/dL; P < 0.05), and the BPD (3.2 mg/dL) was not different (P > 0.05) from either. Dogs fed BPD exhibited globulin levels (2.6 g/dL) slightly below the reference range (2.7–4.4 g/dL), but there was no treatment effect (P > 0.05). The ratio of albumin to globulin was also not affected (P > 0.05), but all treatments (AMD = 1.2; BPD = 1.2; CD = 1.2) had a ratio higher than the reference range (0.6–1.1). Serum calcium levels were within reference ranges, but were greater (P < 0.05) for dogs fed AMD (10.3 mg/dL) than CD (10.1 mg/dL), but BPD (10.2 mg/dL) was not different (P > 0.05) from either. The BPD (26.5 U/L) and CD (25.2 U/L) resulted in levels of alkaline phosphatase total that were similar (P > 0.05), but lower (P < 0.05) than the AMD (51.7 U/L). The same relationship was observed for corticosteroid-induced alkaline phosphatase: AMD (22.6) was greater (P < 0.05) than BPD (8.9) and CD (6.3), which were not different (P > 0.05) from each other. The BPD (0.2 mg/dL) resulted in greater (P < 0.05) levels of total bilirubin than CD (0.1 mg/dL), and AMD (0.2 mg/dL) was intermediate and not different (P > 0.05) from either. Cholesterol levels were the highest (P < 0.05) for dogs fed the AMD (236.0 mg/dL) and BPD (198.0 mg/dL) and CD (209.2 mg/dL) were not different (P > 0.05) from each other. Dogs fed the CD (84.1 mg/dL) had a greater (P < 0.05) level of triglycerides compared to those fed the AMD (53.6 mg/dL), with BPD (64.7 mg/dL) not being different (P > 0.05) from either. The reverse relationship was observed with bicarbonate levels: AMD (21.2 mmol/L) was higher (P < 0.05) than CD (19.6 mmol/L), and BPD (20.4 mmol/L) was intermediate and not different (P > 0.05) from AMD and CD.

Table 8.

Fasted serum chemistry profiles for adult canines fed dietary treatments with selected dietary fiber sources

| Item | Reference Range | Treatments1 | SEM2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMD | BPD | CD | |||

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.5–1.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.02 |

| Blood urea nitrogen, mg/dL | 6–30 | 12.1 | 12.7 | 13.1 | 0.47 |

| Total protein, g/dL | 5.1–7.0 | 6.0 | 5.9 | 5.9 | 0.09 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 2.5–3.8 | 3.3a | 3.2a,b | 3.2b | 0.05 |

| Globulin, g/dL | 2.7–4.4 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 0.08 |

| Albumin/globulin ratio | 0.6–1.1 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.04 |

| Calcium, mg/dL | 7.6–11.4 | 10.3a | 10.2a,b | 10.1b | 0.10 |

| Phosphorus, mg/dL | 2.7–5.2 | 3.4 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 0.17 |

| Sodium, mmol/L | 141–152 | 144.7 | 144.7 | 144.4 | 0.42 |

| Potassium, mmol/L | 3.9–5.5 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 0.09 |

| Sodium/potassium ratio | 28–36 | 34.1 | 32.7 | 32.4 | 0.74 |

| Chloride, mmol/L | 107–118 | 109.8b | 111.2a | 111.9a | 0.62 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 68–126 | 90.7 | 88.2 | 91.2 | 2.73 |

| Alkaline phosphatase total, U/L | 7–92 | 51.7a | 26.5b | 25.2b | 4.59 |

| Corticosteroid-induced alkaline phosphatase, U/L | 0–40 | 22.6a | 8.9b | 6.3b | 3.12 |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 8–65 | 34.0 | 34.1 | 32.3 | 4.06 |

| Gamma-glutamyl transferase, U/L | 0–7 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 0.17 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.1–0.3 | 0.2a,b | 0.2a | 0.1b | 0.02 |

| Cholesterol total, mg/dL | 129–297 | 236.0a | 198.0b | 209.2b | 14.73 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 35–154 | 53.6b | 64.7a,b | 84.1a | 10.02 |

| Bicarbonate (TCO2), mmol/L | 16–24 | 21.2a | 20.4a,b | 19.6b | 0.53 |

| Anion gap | 8–25 | 17.9 | 17.6 | 17.7 | 0.68 |

AMD, avocado meal diet; BPD, beet pulp diet; CD, cellulose diet; n = 9.

Clinical Pathology Laboratory at the University of Illinois College of Veterinary Medicine.

Pooled standard error of means.

Superscripts with different letters in a row represent statistical differences (P < 0.05).

The complete blood counts were within normal references ranges for adult canines, except for hematocrit (AMD = 55.5%; BPD = 55.4%; CD = 55.2), which was above the reference range (35%–52%) for all treatments but not different (P > 0.05) from each other (Table 9). All other cell counts were not affected (P > 0.05) by the dietary treatments.

Table 9.

Fasted complete blood cell analysis for adult canines fed dietary treatments with selected dietary fiber sources

| Item | Reference range2 | Treatments1 | SEM3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMD | BPD | CD | |||

| Red blood cells, ×106/µL | 5.50–8.50 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 0.22 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 12.0–18.0 | 17.8 | 17.7 | 17.7 | 0.47 |

| Hematocrit, % | 35.0–52.0 | 55.5 | 55.4 | 55.2 | 1.47 |

| Mean cell volume, fl | 60.0–77.0 | 74.6 | 74.8 | 75.1 | 0.57 |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin, pg | 20.0–25.0 | 24.0 | 24.0 | 24.1 | 0.21 |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, g/dL | 32.0–36.0 | 32.1 | 32.0 | 31.2 | 0.11 |

| Platelet estimate, x103/µL | 200–900 | 312.2 | 316.2 | 321.7 | 30.68 |

| White blood cell count, x103/µL | 6.00–17.00 | 6.6 | 7.1 | 7.2 | 0.37 |

| Sequential neutrophils, x103/µL | 3.00–11.50 | 4.7 | 5.0 | 5.2 | 0.36 |

| Band neutrophils, x103/µL | 0.00–0.30 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.03 |

| Lymphocytes, x103/µL | 1.00–4.80 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 0.19 |

| Monocytes, x103/µL | 0.20–1.40 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.07 |

| Eosinophils, x103/µL | 0.10–1.00 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.05 |

| Basophils, x103/µL | 0.00–2.00 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

AMD, avocado meal diet; BPD, beet pulp diet; CD, cellulose diet; n = 9.

Clinical Pathology Laboratory at the University of Illinois College of Veterinary Medicine.

Pooled standard error of means.

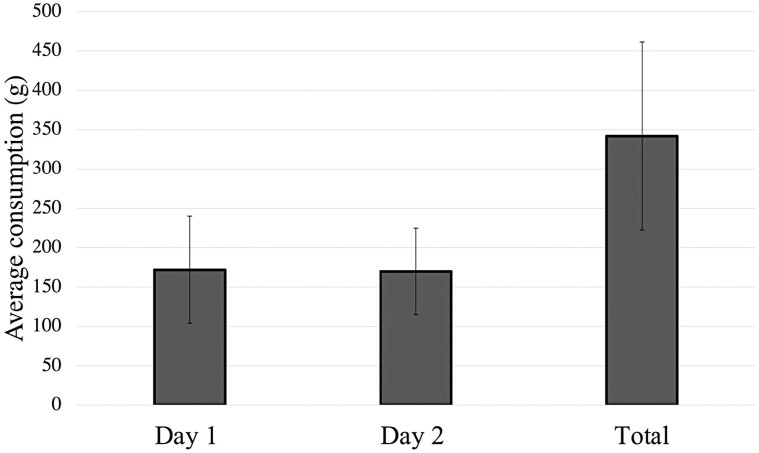

Monadic testing resulted in an average daily food intake of 172.1 ± 68.2 g for day 1, 169.8 ± 55.1 g for day 2, and 341.9 ± 119.3 g for both days (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Monadic palatability test for avocado meal diet fed to adult dogs (n = 20).

Discussion

Fiber in canine diets has become a greater concern with recent research suggested that fiber can aid with weight loss and supports beneficial bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract. Avocado meal has not been evaluated as a fiber source for canines, nor has the impact of high fiber formulations on physical and organoleptic characteristics of extruded foods been described.

Currently, there is limited literature on avocado meal composition. The first study to test avocado meal in an animal diet was done by Naveh et al. (2002); the defatted avocado pulp tested was comprised of 43.4% TDF, 15.8% moisture, 12.8% CP, and 2.5% ash. The chemical composition of another source of avocado meal was characterized as 9.5% CP, 51.82% neutral detergent fiber, 39.33% acid detergent fiber, 25.8% acid detergent lignin, and 0.38% acid detergent insoluble nitrogen on DM basis (Skenjana et al., 2006). Most recently, van Ryssen et al. (2013) reported comparable nutrient composition of avocado meal for DM (94.9%), CP (15.6%), fiber (34.9%), and fat (6.3%) to the avocado meal evaluated herein. Oleic (C18:1 c9; 57%) and palmitic (C16:0; 14%) acids were also the most predominant fatty acids in avocado pulp and peel ingredient (de Evans et al., 2020). It is possible that variations observed in these different sources of avocado meal are related to the avocado oil extraction method, parts and proportions of the fruit that were included in the final ingredient, as well as analytical methods utilized to determine chemical composition. Those previous studies have not determined, however, the concentration of persin in avocado meal or parts of the avocado fruit. Because persin was present in all parts of the avocado fruit (i.e., peel, pulp, and pit) but not in avocado meal, it is likely that this compound was degraded during the thermal processing applied during the manufacturing of this ingredient. Persin is an acetogenin derived from the biosynthesis of long-chain fatty acids, with structural homology to linoleic acid (Butt et al., 2006). Persin might be susceptible to oxidation during thermal processes and light exposure; however, further research on this front is needed. Variable concentrations of persin in different cultivars of avocado have been reported (Carman and Handley, 1998). In general, Hass variety had the highest persin concentration (4.5–4.1 mg/g of fresh leaf), whereas cultivars Duke-7, Zutano, Velvck, Edranol, and Martin Grande had persin concentrations lower than 1 mg/g of fresh leaf.

In general, the physical and organoleptic results from this study agree with previously published findings from research on fiber-rich human food products. Kibble hardness and energy to compress for AMD and BPD were lower than for CD. This was driven by the differences in SDF and IDF, and was previously observed by Yanniotis et al. (2007) who found that extrudates higher in IDF were less expanded than those higher in SDF. Our results do not support that, but our main processing goal was to produce dietary treatments with similar bulk density, piece diameter, and piece length. Different processing settings have the ability to change the degree of expansion (Lue et al., 1991; Rinaldi et al., 2000) and it might confound our results.

Standard fiber sources (BPD and CD) showed results similar to previously published literature. Even though our BPD was high in TDF (> 15%, DM basis), and the ATTD from our BPD diet are well-aligned with those reported by Fahey et al. (1990), who tested the effects of 6 levels of beet pulp (0.0%, 2.5%, 5.0%, 7.5%, 10.0%, and 12.5%) in diets for canines and found 7.5%, DM basis, of beet pulp to be ideal. In addition, and agreeing with Fahey et al. (1990), we observed an increased fecal output on an as-is basis for dogs fed the BPD that was not observed for dogs fed the AMD or CD. This is likely due to the water holding capacity of beet pulp fiber. Howard et al. (2000) also reported no differences (P > 0.10) in DM digestibility and DM intake between cellulose (6% DM basis) and beet pulp (6% DM basis), which was also observed in the present study, when they compared them in a study with diets containing a fiber blend (6.0% beet pulp, 2.0% gum talha, and 1.5% fructooligosaccharides, DM basis) or fructooligosaccharides (1.5% DM basis) and a no-fiber diet. Our results agree with their finding that beet pulp and cellulose do not result in different GE or nitrogen/CP intakes. The finding that there are no differences in nitrogen/CP digestibility between the two sources was not found in the present study. Howard et al. (2000) found that beet pulp was more fermentable than cellulose, meaning that more nutrients were available to the gastrointestinal microbiota when the dogs were fed beet pulp. This would result in greater concentrations of fermentative end-products for BPD, which was seen in total SCFA, acetate, butyrate, propionate, and valerate. Other fermentation end products were either not significant or greater for CD, but overall BPD and CD performed as expected.

Although previous research on avocado meal and defatted avocado pulp is limited, some of it agrees with the results obtained with the AMD. Naveh et al. (2002) also observed decreased fecal output (as-is) for defatted avocado pulp compared to cellulose when fed to rats. They also found that as-is food intake for defatted avocado pulp was lower than for cellulose; this was observed in the numerically, but not significantly, lower DM intake for AMD compared to CD. We may have observed stronger significance if expressed on an as-is basis. Our conclusion that avocado meal may be a good fiber source for canines supports the work of van Ryssen et al. (2013), who tested multiple levels of avocado meal in complete diets for broiler chickens and found that increased levels of avocado meal decreased production, as is expected with higher levels of fiber.

Avocado meal performed similarly to cellulose in canine diets. Fermentability of the fiber sources likely played a role in the results. Bosch et al. (2009) found differences when feeding a highly fermentable canine diet (8.5% as-is beet pulp, 2% as-is inulin) vs. a poorly fermentable canine diet (8.5% as-is cellulose). In their study, food intake tended to be lower for dogs fed the highly fermentable diet. In our study, AMD-fed dogs trended to have lower voluntary DM intake than BPD, but CD did not differ. Bosch et al. (2009) also reported decreased ATTD of DM, OM, neutral detergent fiber, acid detergent fiber, non-starch polysaccharides, and energy and increased ATTD of crude fat when the high fermentability diet was consumed. The only result confirmed in our study is the greater AHF ATTD observed in AMD and CD compared to BPD. Dry matter, OM, and energy ATTD were not significantly impacted in our study. However, CP ATTD for AMD and BPD was reduced when compared with CD. A potential reason is higher excretion of microbial protein in the feces of dogs fed AMD and BPD due to greater gut fermentation.

Bosch et al. (2009) also measured short-chain fatty acids and found increased concentrations of total SCFA, acetate, and propionate when dogs were fed the highly fermentable diet vs. the poorly fermentable diet. A highly fermentable diet will provide a greater pool of substrates for gut microbes to ferment, resulting in greater concentrations of fermentative end-products. Our study showed lower total SCFAs, acetate, butyrate, and propionate concentrations for CD than BPD, which was expected because beet pulp is more fermentable than cellulose. Unexpectedly, fecal concentrations of total SCFAs, acetate, and propionate from dogs fed AMD were not different from dogs fed CD and concentration of butyrate was not different from dogs fed BPD. This, in conjunction with the results from Bosch et al. (2009), further suggests that avocado meal fermentability is intermediate between beet pulp and cellulose.

Overall, the dogs in this study remained healthy on all treatments. No serum metabolites were outside acceptable ranges. Hematocrit was above the range for healthy canines for all treatments, but only by 3%. This is not great enough to cause concern. Urine of AMD-fed and BPD-fed dogs appeared darker than CD-fed dog urine. This could be caused by the presence of anthocyanins in beet pulp and avocado meal, mainly coming from the skin (Ashton et al., 2006).

No clinical signs of persin toxicity were exhibited in this study. Published case studies have listed serum chemistry results observed while consuming portions of avocado. The Grant et al. 1991 study in rats showed elevated blood urea nitrogen, whereas the dogs in our study had normal levels and did not exhibit treatment effects. Moderate kidney disease was observed in a hen fed 12.5 g of avocado leaves per kg of body weight and a hen fed 15 g of unripe fruit per kg of body weight (Burger et al., 1994). Consumption of AMD in this study resulted in normal serum creatinine levels comparable to BPD and CD. A case study in two dogs suspected of suffering from avocado toxicity reported normal blood urea nitrogen and protein, but elevated white blood cells and serum alanine aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase levels (Buoro et al., 1994). Dogs in this study had statistically higher alkaline phosphorus total when fed AMD compared to BPD and CD, but these levels were within normal ranges. There was also no observed effect on alanine amino transferase or white blood cells, which does not agree with Buoro et al. (1994). Blood serum in rabbits fed avocado leaves had elevated sodium levels and lower chloride and phosphorus levels than acceptable (Ali et al., 2010). The present study showed no treatment effects on sodium and phosphorus levels, and all levels were within normal ranges. Chloride levels were significantly lower for AMD compared to BPD and CD, but the levels were still acceptable and the differences too small to be detected clinically. The only blood count outside of acceptable ranges was hematocrit, which was only slightly elevated and not mentioned in any reported case of persin toxicity. Avocado meal-fed dogs did not exhibit abnormal levels of lymphocytes and neutrophils, as was seen in Buoro et al. (1994). These results make it highly unlikely that persin toxicity is a concern when feeding a diet containing avocado meal. Total cholesterol was also significantly higher in AMD, but was still within reference ranges. This treatment effect was also seen in rats (Naveh et al., 2002; Imafidon et al., 2010); the researchers believe that this occurred because the supplemented levels of avocado pulp or aqueous avocado seed extract, respectively, were above the ideal supplementation. A commercial diet would not contain as much avocado meal as this experimental diet (18.67%), which means that any of the serum chemistry results from this study may be diminished with a commercial formulation.

One concern with fiber sources is potentially negative impacts on palatability (Fekete et al., 2001). The monadic test revealed that acceptability of AMD was adequate (approx. 150 g/d) and similar to the daily food intake results observed during the digestibility study (approx. 143 g/d). Even though the monadic test and digestibility trial were not done using the same dogs, both trials used Beagles of similar body weight. Because the dogs in the monadic test did not overeat the AMD diet, the addition of extra topical fat and palatant can be used to improve food palatability.

Conclusions

Avocado meal appears to be an acceptable dietary fiber source for adult canines. The present study shows that avocado meal performs similarly to cellulose in a high TDF diet in terms of ATTD and fecal fermentative end-product concentrations. All differences in blood analyses were within acceptable ranges, which suggests that dogs can maintain good health while fed a diet containing avocado meal for 2 wk. In addition, a commercially produced diet likely will not contain high inclusion levels of avocado meal, so the negative impacts on food palatability could be diminished. A diet formulated with less avocado meal also may not need as much added fat and palatant to maintain or improve diet acceptance and palatability. Future work should develop and evaluate fiber blends incorporating avocado meal to examine their potential functionality for gut and animal health, as long as determine long-term effects on the health status of pet animals fed avocado-containing products.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIFA ILLU-538-938 grant. We thank Dr. Sajid Alavi, Professor at the Department of Grain Science and Industry at Kansas State University and the staff at the Kansas State University Bioprocessing and Industrial Value Added Products Innovation Center (Manhattan, KS) for assisting in the manufacturing of the extruded diets.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AMD

avocado meal diet

- ATTD

apparent total tract digestibility

- AHF

acid hydrolyzed fat

- BCFA

branched chain fatty acids

- BPD

beet pulp diet

- CD

cellulose diet

- CP

crude protein

- DM

dry matter

- GE

gross energy

- GC

gas chromatography

- OM

organic matter

- mL

milliliter

- mm

millimeter

- N

Newton

- SCFA

short-chained fatty acids

- SEI

sectional expansion index

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- TDF

total dietary fiber

- µg

microgram

- µM

micromolar

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no real or perceived conflicts of interest.

Literature Cited

- Ali, M. A., Chanu Kh. V., Singh W. R., Shah M. A. A., and Leishangthem G. D.. . 2010. Biochemical and pathological changes associated with avocado leaves poisoning in rabbits—a case report. Int. J. Res. Pharm. Sci. 1:225–228. [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Cereal Chemists (AACC) . 1983. Approved methods. 8th ed. St. Paul (MN):American Association of Cereal Chemists. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton, O. B. O., Wong M., McGhie T. K., Vather R., Wang Y., Requejo-Jackman C., Ramankutty P., and Woolf A. B.. . 2006. Pigments in avocado tissue oil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 54:10151–10158. doi: 10.1021/jf061809j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) . 2016. Official publication. Champaign (IL):Association of American Feed Control Officials, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC) . 2006. Official methods of analysis. 17th ed. Gaithersburg (MD):Association of Official Analytical Chemists. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, G., Verbrugghe A., Hesta M., Holst J. J., van der Poel A. F., Janssens G. P., and Hendriks W. H.. . 2009. The effects of dietary fibre type on satiety-related hormones and voluntary food intake in dogs. Br. J. Nutr. 102:318–325. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508149194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, D. G., Shelley E. J., Roberts C. G., Denny W. A., Sutherland R. L., and Butt A. J.. . 2011. Synthesis and in vitro evaluation of analogues of avocado-produced toxin (+)-(R)-persin in human breast cancer cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 19:7033–7043. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budde, E. F. 1952. The determination of fat in baked biscuit type of dog foods. J. Assoc. Off. Agric. Chem. 35:799–805. [Google Scholar]

- Buoro, I. B., Nyamwange S. B., Chai D., and Munyua S. M.. . 1994. Putative avocado toxicity in two dogs. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 61:107–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger, W. P., Naudé T. W., van Rensburg I. B. J., Botha C. J., and Pienaar A. C. E.. . 1994. Cardiomyopathy in ostriches (Struthio camelus) due to avocado (Persea americana var. Guatemalensi) intoxication. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. 65:113–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt, A. J., Roberts C. G., Seawright A. A., Oelrichs P. B., Macleod J. K., Liaw T. Y., Kavallaris M., Somers-Edgar T. J., Lehrbach G. M., Watts C. K., . et al. 2006. A novel plant toxin, persin, with in vivo activity in the mammary gland, induces Bim-dependent apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 5:2300–2309. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carman, R. M., and Handley P. N.. . 1998. Antifungal diene in leaves of various avocado cultivars. Phytochem. 50:1329–1331. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(98)00348-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaney, A. L., and Marbach E. P.. . 1962. Modified reagents for determination of urea and ammonia. Clin. Chem. 8:130–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding, H., Chin Y. W., Kinghorn A. D., and D’Ambrosio S. M.. . 2007. Chemopreventive characteristics of avocado fruit. Semin. Cancer Biol. 17:386–394. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2007.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogan, H. and Kokini J. L.. . 2007. Psychophysical markers for crispness and influence of phase behavior and structure. J. Texture Stud. 38:324–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4603.2007.00100.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin, E. S., March G. J., and Emergy E. M.. . 1961. Volatile fatty acid analysis of blood and rumen fluid by gas chromatography. J. Dairy Sci. 44:1768–1771. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(61)89956-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Evan, T., Carro M. D., Fernández Yepes J. E., Haro A., Arbesú L., Romero-Huelva M., and Molina-Alcaide E.. . 2020. Effects of feeding multinutrient blocks including avocado pulp and peels to dairy goats on feed intake and milk yield and composition. Animals. 10:194. doi: 10.3390/ani10020194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahey, G. C., Jr., Merchen N. R., Corbin J. E., Hamilton A. K., Serbe K. A., Lewis S. M., and Hirakawa D. A.. . 1990. Dietary fiber for dogs: I. Effects of graded levels of dietary beet pulp on nutrient intake, digestibility, metabolizable energy, and digesta mean retention time. J. Anim. Sci. 68:4221–4228. doi: 10.2527/1990.68124221x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete, S., Hullár I., Andrásofszky E., Rigó Z., and Berkényi T.. . 2001. Reduction of the energy density of cat foods by increasing their fibre content with a view to nutrients’ digestibility. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl). 85:200–204. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0396.2001.00332.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flickinger, E. A., Schreijen E. M., Patil A. R., Hussein H. S., Grieshop C. M., Merchen N. R., and G. C.Fahey, Jr. 2003. Nutrient digestibilities, microbial populations, and protein catabolites as affected by fructan supplementation of dog diets. J. Anim. Sci. 81:2008–2018. doi: 10.2527/2003.8182008x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodall, S. R., and Byers F. M.. . 1978. Automated micro method for enzymatic L(+) and D(-) lactic acid determinations in biological fluids containing cellular extracts. Anal. Biochem. 89:80–86. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90728-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant, R., Basson P. A., Booker H. H., Hofherr J. B., and Anthonissen M.. . 1991. Cardiomyopathy caused by avocado (Persea americana Mill) leaves. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. 62:21–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard, M. D., Kerley M. S., Sunvold G. D., and Reinhart G. A.. . 2000. Source of dietary fiber fed to dogs affects nitrogen and energy metabolism and intestinal microflora populations. Nutr. Res. 20:1473–1484. doi: 10.1016/S0271-5317(00)80028-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Imafidon, K. E. and Amaechina F. C.. . 2010. Effects of aqueous seed extract of Persea americana mill. (avocado) on blood pressure and lipid profile in hypertensive rats. Advan. Biol. Res. 4: 116–121. [Google Scholar]

- Lue, S., Hsiesh F., and Huff H. E.. . 1991. Extrusion cooking on corn meal and sugar beet fiber: effects on expansion properties, starch gelatinization, and dietary fiber content. Cereal Chem. 68:227–234. [Google Scholar]

- Naveh, E., Werman M. J., Sabo E., and Neeman I.. . 2002. Defatted avocado pulp reduces body weight and total hepatic fat but increases plasma cholesterol in male rats fed diets with cholesterol. j. Nutr. 132:2015–2018. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.7.2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberlies, N. H., Rogers L. L., Martin J. M., and McLaughlin J. L.. . 1998. Cytotoxic and insecticidal constituents of the unripe fruit of Persea americana. J. Nat. Prod. 61:781–785. doi: 10.1021/np9800304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oelrichs, P. B., Ng J. C., Seawright A. A., Ward A., Schäffeler L., and MacLeod J. K.. . 1995. Isolation and identification of a compound from avocado (Persea americana) leaves which causes necrosis of the acinar epithelium of the lactating mammary gland and the myocardium. Nat. Toxins 3:344–349. doi: 10.1002/nt.2620030504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosky, A., Asp N. G., Schweizer T. F., Devries J. W., and Furda I.. . 1992. Determination of insoluble and soluble dietary fiber in foods and food products: collaborative study. J. AOAC. 75:360–367. doi: 10.1093/jaoac/75.2.360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi, V. E. A., Ng P. K. W., and Bennink M. R.. . 2000. Effects of extrusion on dietary fiber and isoflavone contents of wheat extrudates enriched with wet okara. Cereal Chem. 77:237–240. doi: 10.1094/CCHEM.2000.77.2.237 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Saona, C., and Trumble J. T.. . 2000. Biologically active aliphatic acetogenins from specialized idioblast oil cells. Curr. Org. Chem. 4:1249–1260. doi: 10.2174/1385272003375789 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Ryssen, L. B. J., Skenjana A., and van Niekerk W. A.. . 2013. Can avocado meal replace maize meal in broiler diets? Appl. Anim. Husb. Rural Develop. 6:22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Skenjana, A., van Ryssen J. B. J., and van Niekerk W. A.. . 2006. In vitro digestibility and in situ degradability of avocado meal and macadamia waste products in sheep. South African J. Anim. Sci. 36:78–81. [Google Scholar]

- Yanniotis, S., Petraki A., and Soumpasi E.. . 2007. Effect of pectin and wheat fibers on quality attributes of extruded cornstarch. J. Food Eng. 80:594–599. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2006.06.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]