Abstract

Isocyanoaminoarenes (ICAAr-s) are a novel and versatile group of solvatochromic fluorophores. Despite their versatile applicability, such as antifungals, cancer drugs and analytical probes, they still represent a mostly unchartered territory among intramolecular charge-transfer (ICT) dyes. The current paper describes the preparation and detailed optical study of novel 1-isocyano-5-aminoanthrace (ICAA) and its N-methylated derivatives along with the starting 1,5-diaminoanthracene. The conversion of one of the amino groups of the diamine into an isocyano group significantly increased the polar character of the dyes, which resulted in a significant 50–70 nm (2077–2609 cm−1) redshift of the emission maximum and a broadened solvatochromic range. The fluorescence quantum yield of ICAAs is strongly influenced by the polarity of the solvent. The starting anthracene-diamine is highly fluorescent in every solvent (√f = 12–53%), while the isocyano derivatives are practically nonfluorescent in solvents more polar than dioxane. This phenomenon implies the potential application of ICAAs to probe the polarity of the medium and is favorable in practical applications, such as cell-staining, resulting in a reduced background fluorescence. The ICT character of the emission states of ICAAs are in good agreement with the computational findings presented in TD-DFT calculations and molecular electrostatic potential (MESP) isosurfaces.

Keywords: anthracene, fluorescence, solvatochromic effect, isonitrile, DFT

1. Introduction

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) moieties such as pyrene and anthracene are important building blocks of smart electronic and fluorescent materials [1,2,3]. Owing to their rigid planar structure and easy substitutability with reactive or bulky functional groups, they can be incorporated into more complex structures, such as graphene nanoribbons [4] and ribbon-like pyrene-fused pyrazaacenes (PPAs) [5]. The unprecedented optoelectronic properties of these complex structures can be utilized in many optoelectronic applications, for example, in dye sensitized solar cells (DSSCs) [6] among all. In addition, anthracene moiety makes up the core of many important fluorescent probes used for the detection of transition metal ions such as Zn2+ [7]. The formation of at least two amino groups on PAHs in symmetric positions offers an easy way to incorporate the aromatic moiety into more complex structures through alkylation, acylation or diazotation reactions. In addition, by varying the number and position of N atoms and the substitution on the aromatic core along the π-framework, it is possible to modulate the electronic structure, stability, solubility and supramolecular organization [8,9]. In this context, the molecular organization in π-conjugated systems could be further controlled by virtue of the cooperative effect of stronger non-covalent interactions. Among them, hydrogen bonding represents an appropriate tool [10,11,12], as it is evidenced by biological systems in which the combination of π-stacking and hydrogen bonds determines the macrostructure of proteins or nucleic acids, just to mention well-known examples. One of the most important members of diamino PAHs is 1,5-diaminoanthracene, which is used to construct organic semiconductors [13], dinuclear nickel complexes for highly active ethylene dimerization [14], self-assembled small-molecule-based hole-transporting material for inverted perovskite solar cells [15], photoactivated healable vitrimeric copolymers [16], amorphous porous organic polymers for highly efficient iodine capture [17], bimetallic aluminum complexes for ring-opening polymerization of lactide [18], Luminescent Supramolecular Lanthanide Complexes [19], Squaraine dyes [20] and others. Despite its widespread application, the literature on the optical properties of 1,5-diaminoanthracene is very limited.

The optical properties may be further enhanced (while preserving the important H-bonding ability) by converting one of the amino groups into isocyanide using dichlorocarbene [21]. Only a few members of the resulting isocyanoaminoarene substance family have been prepared and studied until recently, despite their simple structure and preparation. Isocyanoaminoarenes are typically built up from an electron-donating (amino, D) and an electron-withdrawing (isocyano, A) group, connected through an aromatic π-linker moiety. These so-called D-π-A type solvatochromic fluorophores are therefore based on the shift of the electron density from the donor group to the acceptor moiety through the π-system upon excitation; hence, an intramolecular charge-transfer (ICT) takes place [22,23], which may result in an increase in the excited state dipole moment with respect to that of the ground state. It is believed that the presence of ICT, in the absence of any specific interaction, i.e., hydrogen-bonding, between the fluorophore and the solvent is the primary reason of solvatochromism. Fluorophores, whose fluorescence emissions are particularly sensitive to the polarity of their microenvironment and hence they alter the emitted light color upon the effect of polarity change, are called solvatochromic fluorophores [23].

Recently, we have synthesized a series of new solvatochromic fluorophores based on the preliminary concept of ICT in which the donor amine and the acceptor isocyano groups are connected via the naphthalene moiety in its 1,5-positions to yield 1,5-isocyanoamino- (1,5-ICAN) derivatives [21,24,25,26]. The 1,5-ICANs exhibit large solvatochromic and Stokes shifts and turned out to be one of the most versatile “smart” fluorophore dye families. They found application as nontoxic supravital stains for the investigation and characterization of both plant and animal cells [27,28], enable the selective detection of Hg2+ and, at the same time, can indicate the presence of Ag+, which is unprecedented among fluorescent sensors [29]. ICANs can also be utilized in silver analytics as isocyanide ligands [26] and the simultaneous presence of the amino, isocyano and naphthalene groups yielded a most effective antifungal drug, the efficacy of which was demonstrated in vivo in mice against Candida strains [30]. Moreover, the small modification of acridine orange (the aromatic core is very similar to the anthracene in this study) resulted in a very efficient physiological pH-probe [31] and the new isocyano-aminoacridines opened up a new pathway in cancer treatment based on phototoxicity studies [32].

The rational design and development of more efficient solvatochromic fluorophores requires a deeper understanding of their structure–property relationships. One of the key factors is the aromatic core of the D-π-A system, which determines the distance between the donor and acceptor groups, and therefore also the dipole moment (and its change upon excitation) of the molecule. We assume that the solvatochromic range of ICANs could be extended while keeping their advantageous properties by exchanging the naphthalene ring to the larger anthracene. Since the field of isocyanoaminoarenes is still largely unexplored, we believe that they may contain a considerable potential to become versatile smart dyes. The aim of this study is therefore the preparation of novel 1-amino-5-isocyanoanthracenes and the detailed optical study of these fluorophores along with the starting 1,5-diaminoanthracene.

2. Results and Discussion

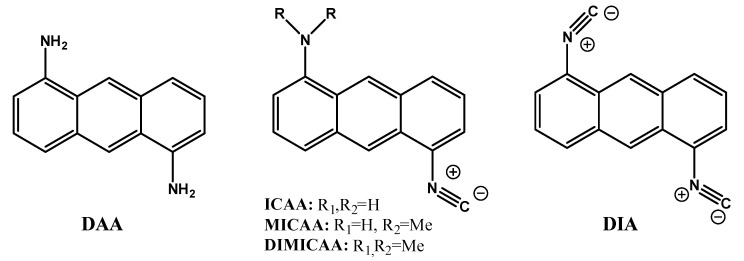

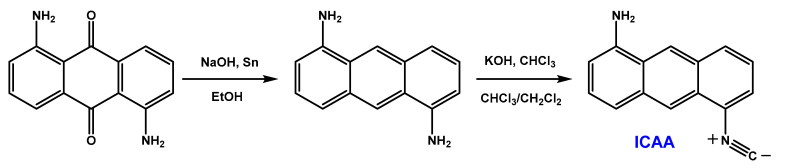

1,5-Diaminoanthracene (DAA) was obtained by the reduction of 1,5-Diaminoanthraquinone and was easily converted to 1-Amino-5-isocyanoanthracene (ICAA) and 1,5-Diisocyano-anthracene (DIA) by the reaction of the amino group(s) with dichlorocarbene. To enhance the optical properties, alkylation of ICAA was carried out by using MeI on the free amino group to yield (MICAA) and (DIMICAA). The structures of the dyes in this study are presented in Figure 1. The purity and structure of the compounds were checked by 1H- and 13C-NMR (spectra can be found in the Supporting Information). ESI-MS measurements further confirmed the structures as the measured m/z values differed with no more than ±0.01 Da from those of the ones calculated.

Figure 1.

The structure and name of the dyes used in this study. The full names are given in the experimental section.

2.1. UV–Vis Electronic Absorption Properties of 1-Amino-5-Isocyanoanthracene Derivatives

To obtain a deeper understanding of the ground state electronic properties of the starting 1,5-diaminoanthracene and its isocyano derivatives, UV–vis spectra were recorded in 15 different solvents, selected to cover a broad range of solvent polarity, spanning from the non-polar hexane to the polar H2O. Another criterion for solvent selection was their ability to form H-bond, either as donor or acceptor, to study the specific solute–solvent interactions, too. All the UV–vis, steady-state emission and excitation spectra in various solvents are presented in the Supporting Information (SI) for all the substances as separate chapters.

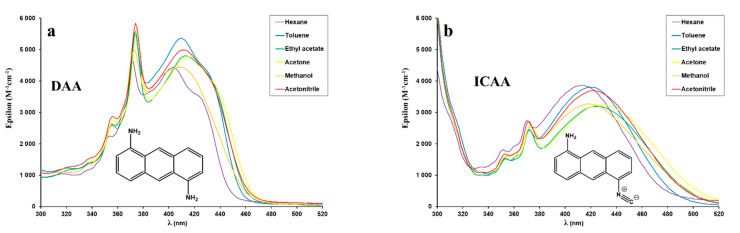

The UV–vis spectra of all the dyes in this study in different solvents are shown in Figure 2, while the absorption maximum wavelength (λAbs) and the corresponding molar extinction coefficients (ε) are compiled in Table 1.

Figure 2.

UV–vis spectra of 1,5-diaminoanthracene and the isocyano derivatives recorded in solvents of different polarity (a–e). The normalized UV–vis spectra (f) of DAA-DIMICAA in hexane in comparison to 1-amino-5-isocyanonaphthalene (ICAN). ([dye] = 5 × 10−5 M, T = 20 °C).

Table 1.

The absorption maximum wavelengths (λAbs) and the molar extinction coefficients at λAbs (ε) determined in various solvents for the 1,5-diaminoanthracene (DAA) and its isocyano derivatives (ICAA, MICAA, DIMICAA). The dielectric constants of the solvents (εr) are listed next to the solvent names.

| Solvent (εr) | DAA | ICAA | MICAA | DIMICAA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λAbs (nm) | ε ×10−3 (M−1cm−1) | λAbs (nm) | ε ×10−3 (M−1cm−1) | λAbs (nm) | ε ×10−3

(M−1cm−1) |

λAbs (nm) | ε ×10−3 (M−1cm−1) | |

| n-Hexane (1.89) | 403 | 4.4 | 412 | 3.9 | 432 | 3.9 | 397 | 4.9 |

| Toluene (2.38) | 409 | 5.4 | 420 | 3.8 | 433 | 4.1 | 401 | 4.8 |

| DCM (8.93) | 407 | 4.7 | 417 | 3.9 | 431 | 4.0 | 404 | 4.8 |

| 2-propanol (17.9) | 403 | 4.6 | 426 | 3.6 | 434 | 3.9 | 403 | 4.9 |

| THF (7.58) | 416 | 5.0 | 435 | 3.1 | 445 | 3.7 | 404 | 4.8 |

| Chloroform (4.81) | 404 | 4.6 | 414 | 3.8 | 431 | 3.9 | 404 | 4.8 |

| EtOAc (6.02) | 411 | 4.8 | 425 | 3.2 | 437 | 4.0 | 400 | 4.9 |

| Dioxane (2.25) | 415 | 5.2 | 426 | 3.7 | 438 | 4.1 | 402 | 5.1 |

| Acetone (20.7) | 415 | 4.8 | 430 | 3.2 | 441 | 3.7 | 400 | 4.6 |

| Methanol (32.7) | 406 | 4.4 | 426 | 3.3 | 427 | 3.7 | 398 | 4.9 |

| Pyridine (12.4) | 423 | 5.7 | 426 | 3.1 | 451 | 4.0 | 407 | 4.8 |

| Acetonitrile (37.5) | 410 | 5.0 | 422 | 3.7 | 434 | 4.0 | 403 | 4.9 |

| DMF (36.7) | 421 | 5.4 | 442 | 3.1 | 449 | 3.9 | 404 | 4.9 |

| DMSO (46.7) | 426 | 5.3 | 444 | 3.4 | 451 | 4.0 | 409 | 4.9 |

| Water (80.1) | 395 | 4.6 | 410 | 3.6 | 415 | 3.4 | 400 | 3.9 |

As it is evident from Figure 2f and the data of Table 1, the exchange of the 10 π-electron naphthalene ring of ICAN to the 14 π-electron anthracene ring in ICAA, MICAA and DIMICAA results in a significant bathochromic shift (from 338 nm of ICAN to 412 nm of ICAA) of the absorption maximum. This >70 nm (5315 cm−1) redshift is favorable for the practical applicability of the dyes (i.e., cell-staining), since they can be excited using blue-light instead of UV-light, which is toxic for living cells. Independently of solvent polarity, similarly for DAA-DIMICAA, a broad long wavelength absorption band is seen in the range of ~350–500 nm (or ~28571–20000 cm−1, Figure 2f), which can be attributed to the intramolecular charge-transfer transition (ICT) between the donor amino and the acceptor isocyano groups. The ICT character of this band is further supported by the fact that the absorption spectrum of the diisocyano derivative (DIA), where both substituents are electron withdrawing, is almost identical to that of the unsubstituted anthracene [33]. In addition, the absorption bands of the 1,5-diaminoanthracene (DAA, Figure 2a, Figures S2–S16) are narrower and more structured than those of the amino-isocyano derivatives (ICAA-DIMICAA). The ICT band is accompanied by an overlapping sharp absorption band around 370 nm (27027 cm−1) in DAA, ICAA and MICAA, belonging either to the locally excited state (LE) of the aromatic anthracene ring or may appear owing to the vibrational progression associated with N-H bonding. Since this sharp band is completely absent in the case of the dimethylamino-derivative (DIMICAA), which does not have any N-H bond, the N-H vibrational origin is more plausible, as we have shown previously in the case of our ICAN derivatives [24].

It is clearly seen from the data of Table 1 that λAbs is dependent upon the solvent polarity, i.e., the ICT absorption bands suffer a slight redshift with increasing solvent polarity. The bathochromic shifts (from n-hexane to DMSO) are approximately 20 nm (1340 cm−1) for DAA and MICAA and 30 nm (1750 cm−1) for ICAA, while surprisingly only 10 nm (739 cm−1) for DIMICAA. The shifts of the low energy bands are indicative of the polar character of the ground state. Indeed, DFT calculations yielded 2.0, 6.0, 5.5 and 5.5 D ground state dipole moments in hexane (Table 2.) for the 1,5-diamino (DAA), 1-amino-5-isocyano (ICAA), 1-N-methylamino-5-isocyano (MICAA) and 1-N,N-dimethylamino-5-isocyano (DIMICAA) derivatives, respectively. It should be noted, however, that the symmetric product: 1,5-diisocyanoanthracene does not have a dipole moment in either ground or excited state, which explains the lack of ICT band and the structured anthracene-like absorption spectrum.

Table 2.

Dipole moments (μ) and distances between the N-atoms d(N-N) of the functional groups of compounds DAA-DIA in solvents of different polarity, obtained by DFT calculations.

| Hexane | Dioxane | Water | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d (N-N) | µ | d (N-N) | µ | d (N-N) | µ | ||

| S0 (Ground State) | Angstrom | Debye | Angstrom | Debye | Angstrom | Debye | |

| DAA | 7.492 | 2.03 | 7.493 | 2.07 | 7.501 | 2.49 | |

| ICAA | 7.473 | 6.05 | 7.474 | 6.19 | 7.478 | 7.29 | |

| MICAA | 7.479 | 5.55 | 7.480 | 5.67 | 7.488 | 6.50 | |

| DIMICAA | 7.476 | 5.52 | 7.477 | 5.64 | 7.482 | 6.50 | |

| DIA | 7.446 | 0.00 | 7.447 | 0.00 | 7.452 | 0.00 | |

| S1opt (Excited State) | Angstrom | Debye | Angstrom | Debye | Angstrom | Debye | |

| DAA | 7.502 | 1.64 | 7.504 | 1.66 | 7.514 | 1.84 | |

| ICAA | 7.462 | 12.15 | 7.463 | 12.45 | 7.472 | 14.64 | |

| MICAA | 7.541 | 12.98 | 7.543 | 13.32 | 7.554 | 15.81 | |

| DIMICAA | 7.510 | 13.02 | 7.511 | 13.36 | 7.519 | 15.78 | |

| DIA | 7.445 | 0.00 | 7.446 | 0.00 | 7.451 | 0.00 | |

It is evident from the data of Table 2 that the conversion of one of the amino groups of DAA into isocyano group significantly increased the polar character (larger dipole moments) of the dyes. However, it can also be surmised that besides dipole moments, specific dye–solvent interactions, such as H-bonds, may also be responsible for the position of λAbs. In H-bond acceptor solvents, such as THF, dioxane and pyridine, λAbs values are significantly higher than would be expected based on the dielectric constants (polarity) of the solvents. For example, in the case of MICAA, λAbs = 451 nm in pyridine, the highest value is the same as in DMSO. However, the dielectric constant of pyridine is only εr = 12.4, while that of DMSO is εr = 46.7. In contrast, in H-bond donor solvents, such as isopropanol, methanol and chloroform, λAbs values are significantly lower than would be expected based on polarity of the solvent. In DIMICAA, where the amino group is dimethylated and there is no N-H bond, the possibility of the formation of H-bonds is limited, which can explain its narrower λAbs range in different solvents compared to those of DAA-MICAA, where at least 1 N-H bond is present.

Interestingly, λAbs values in water, as in the most polar compound listed in Table 1, are lower than those measured in DMSO for all the amino-isocyano derivatives (ICAA-DIMICAA) and for the starting diamine (DAA), too. The wavelength differences (λAbs, DMSO–λAbs, H2O) are 31 nm (1842 cm−1), 34 nm (1868 cm−1), 36 nm (1923 cm−1) for the 1,5-DAA, 1,5-ICAA and 1,5-MICAA, respectively, while only 10 nm (550 cm−1) for 1,5-DIMICAA. The solvatochromic shifts in DMSO can be probably explained by hydrogen bonds. DMSO is a surprisingly good hydrogen bond acceptor and the large shifts observed for the compounds possessing NH groups are most probably the results of H-bond donation to DMSO molecules. This suggest that the solvatochromic response is strongly modulated by specific interactions, as well. Protic solvents, on the other hand, may form hydrogen bonds with the amine nitrogen. In this case, hypsochromic shifts are expected, since hydrogen bonding to the amine hydrogen would destabilize the ground state resulting in redshift, whereas hydrogen bonding to the amine nitrogen would stabilize the ground state resulting in blueshift. We previously showed the strong H-bond forming capability of amino-isocyanoarenes with pyridine [24]. Of course, the shifts are additionally influenced by the solvent polarity due to dielectric stabilization.

2.2. Steady-State Fluorescence Properties

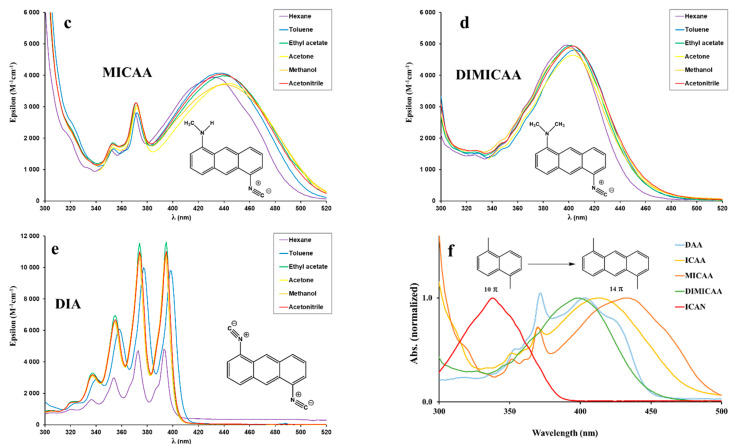

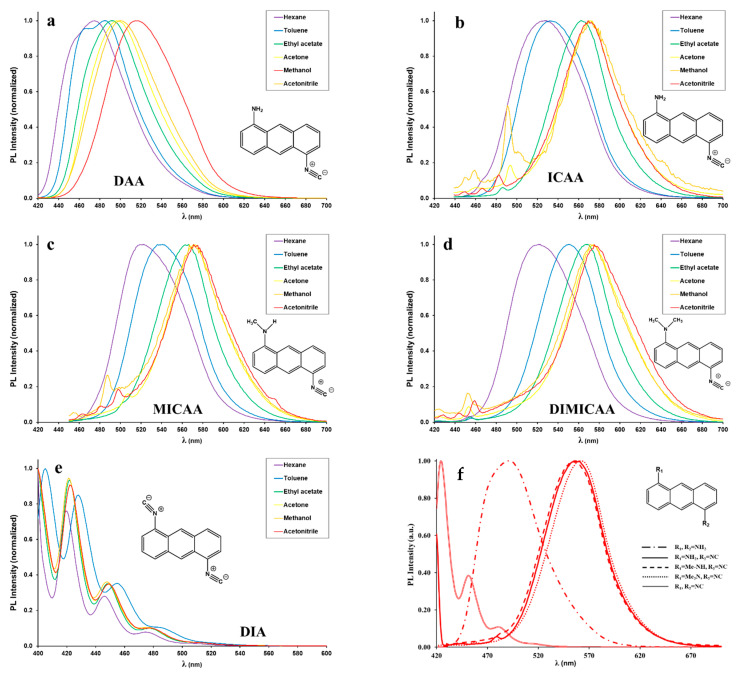

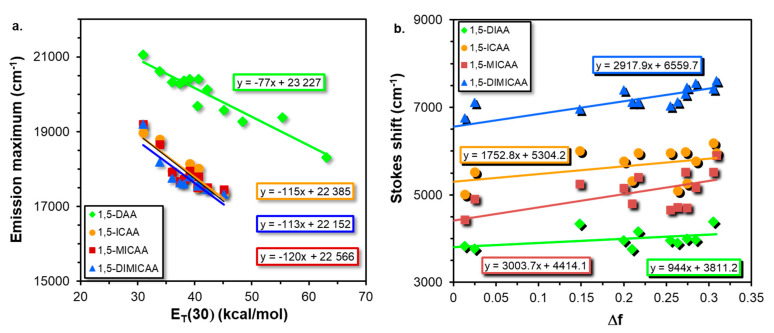

Fluorescence spectra of all dyes (DAA-DIA) were recorded using λAbs values of Table 1 as the excitation wavelengths (λEx). The results are summarized in Figure 3 and Figure 4 (Figures S1, S33, S51, S69 and S72) and in Table 3.

Figure 3.

(a–e) Steady-state fluorescence spectra of DAA, ICAA, MICAA, DIMICAA and DIA recorded in various solvents of different polarity. (f) The normalized emission spectra of DAA-DIA recorded in dioxane. ([dye] = 5 × 10−5 M, T = 20 °C).

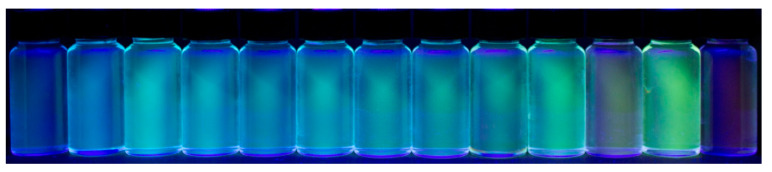

Figure 4.

Demonstration of the fluorescence properties of 1,5-diaminoanthracene (DAA), 1-amino-5-isocyanoanthracene (ICAA), 1-N-methylamino-5-isocyanoanthracene (MICAA) and 1-N,N-dimethylamino-5-isocyanoanthracene (DIMICAA) (from top to bottom) in different solvents illuminated by light of λ = 365 nm. Solvents from left to the right are hexane, toluene, 1,4-dioxane, dichloromethane, chloroform, tetrahydrofuran (THF), acetonitrile, acetone, pyridine, methanol, dimethylformamide (DMF), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), water.

Table 3.

The fluorescence emission maxima (λEm), the quantum yields (Φf) and the Stokes shifts ( ) determined in various solvents for the 1,5-disubstituted anthracene derivatives.

| 1,5-DAA | 1,5-ICAA | 1,5-MICAA | 1,5-DIMICAA | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent | λEm (nm) | √f (%) | (cm−1) | λEm (nm) | √f (%) | (cm−1) | λEm (nm) | √f (%) | (cm−1) | λEm (nm) | √f (%) | (cm−1) |

| n-Hexane | 475 | 21 | 3761 | 527 | 13 | 5297 | 521 | 12 | 3954 | 521 | 14 | 5995 |

| Toluene | 485 | 38 | 3831 | 532 | 14 | 5013 | 536 | 11 | 4438 | 550 | 11 | 6756 |

| DCM | 490 | 40 | 4162 | 555 | 6.7 | 5963 | 562 | 5.9 | 5408 | 567 | 5.9 | 7116 |

| 2-propanol | 519 | 23 | 5546 | 572 | 0.4 | 5992 | 571 | 1.0 | 5528 | 571 | 1.7 | 7301 |

| THF | 493 | 34 | 3754 | 566 | 2.9 | 5321 | 566 | 3.7 | 4804 | 567 | 4.5 | 7116 |

| Chloroform | 490 | 12 | 4717 | 551 | 7.8 | 6006 | 557 | 7.0 | 5249 | 562 | 9.7 | 6959 |

| EtOAc | 491 | 32 | 3964 | 563 | 3.4 | 5767 | 564 | 3.4 | 5153 | 568 | 3.8 | 7394 |

| Dioxane | 492 | 53 | 3771 | 557 | 6.6 | 5521 | 558 | 7.5 | 4910 | 563 | 9.0 | 7114 |

| Acetone | 497 | 25 | 3976 | 572 | 1.1 | 5773 | 571 | 1.3 | 5163 | 573 | 1.6 | 7548 |

| Methanol | 516 | 17 | 5251 | 571 | 0.3 | 5961 | 571 | 0.5 | 5906 | 571 | 0.8 | 7612 |

| Pyridine | 508 | 22 | 3956 | 571 | 1.3 | 5961 | 571 | 1.5 | 4660 | 570 | 3.7 | 7026 |

| Acetonitrile | 500 | 28 | 4390 | 571 | 0.9 | 6184 | 571 | 0.8 | 5528 | 575 | 0.9 | 7423 |

| DMF | 506 | 37 | 3990 | 576 | 0.4 | 5263 | 572 | 0.8 | 4820 | 578 | 0.9 | 7451 |

| DMSO | 511 | 45 | 3905 | 576 | 0.3 | 5160 | 573 | 0.9 | 4720 | 577 | 1.0 | 7119 |

| Water | 546 | 3.1 | 7001 | 530 | 0.1 | - | 559 | 0.2 | 6207 | 567 | 0.2 | 7363 |

As it is evident from Figure 3, the conversion of one amino group into isocyano resulted in a significant 50–70 nm (2077–2609 cm−1) redshift of the emission maximum of ICAA-DIMICAA compared to that of the starting diamine (DAA) in most of the solvents. ICAA, MICAA and DIMICAA (and to a limited extent DAA) clearly show positive solvatochromic behavior, i.e., their emission maximum shifts to higher wavelengths with increasing solvent polarity, due to the stabilizing effect of solvent reorganization around the excited dye [23]. The solvatochromic ranges (λem,DMSO–λem,hexane) are Δλ = 36 nm (1483 cm−1), 49 nm (1614 cm−1), 50 nm (1742 cm−1) and 56 nm (1863 cm−1) for DAA, ICAA, MICAA and DIMICAA, respectively. It is important to note that the diisocyano derivative DIA does not show any solvatochromic behavior because of the lack of ICT. When the fluorescence properties of ICAA are compared to those of our naphthalene-cored solvatochromic dye, ICAN, the bathochromic shifts are more significant due to the exchange of the 10π naphthalene core to the 14π anthracene core. For example, the emission maximum of ICAN was found to be at 409 and 497 nm for hexane and DMSO in the blue and greenish-blue region of visible light, while λem,max for ICAA is redshifted to 527 and 574 nm in the same solvents (Figure 3 and Figure 4). The bathochromic shift is almost 120 nm (5474 cm−1) in hexane; however, it is only 77 nm (2699 cm−1) in DMSO meaning the contraction of the emission range of ICAA to 49 nm (1553 cm−1), which is only half of that of ICAN. A possible explanation can be the limited solubility of ICAA in polar solvents, which is further backed by the observation that ICAA is practically nonfluorescent in solvents more polar than dioxane (Figure 4). Surprisingly, increasing the electron donating character of the amino group by methylation did not enhance the optical properties of ICAA as was shown previously for our ICAN compounds. Both the solvatochromic range and the position of the emission maximum are virtually the same for the methylated (MICAA), dimethylated (DIMICAA) and nonmethylated (ICAA) 1-amino-5-isocyanoanthracenes.

2.3. Fluorescence Quantum Yield of ICAA Derivatives in Different Solvents

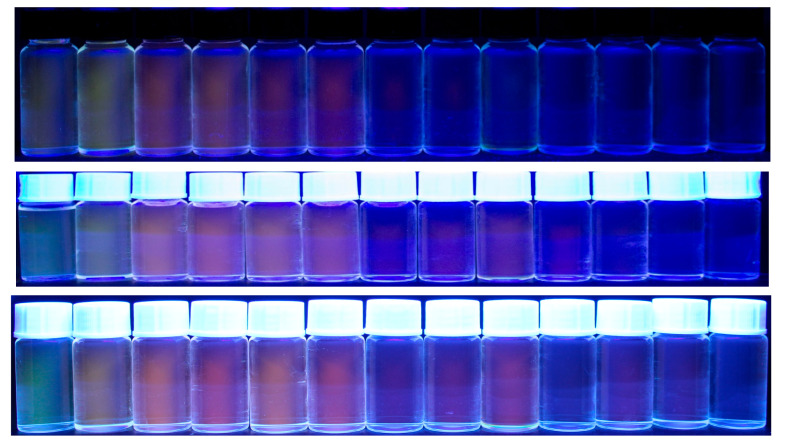

An essential property, which also determines the practical applicability of any fluorophore, is their quantum yield (√f), i.e., the ratio of the emitted and absorbed photons. The fluorescence quantum yield of ICAAs is strongly influenced by the polarity of the solvent (Table 3). The starting anthracene-diamine is highly fluorescent in every solvent (√f = 12–53%); however, in water, the quantum yield drops to only 3%. In contrast, √f rarely exceeds 10% in nonpolar solvents for the isocyano derivatives ICAA, MICAA and DIMICAA, and they are practically nonfluorescent in solvents more polar than dioxane (Figure 4). In polar solvents, the quantum yields of ICAA-DIMICAA are close to only 1%; moreover, it drops to only √f = 0.1–0.2% in water. The fluorescence quantum yield of DAA, ICAA, MICAA and DIMICAA in different solvents was correlated with the empirical Dimroth polarity parameters ET(30) of the solvents (Figure 5). While no clear correlation was obtained for the diamine (DAA), the isocyano derivatives (ICAA-DIMICAA) show almost identical behavior, i.e., a sharp decrease in √f between ET(30) = 30–40 (kcal/mol), followed by a constant minimum range above ET(30) > 40 (kcal/mol). A very similar behavior was described for 1,8-naphthalimides [34,35]. This phenomenon implies the potential application of ICAAs to probe the polarity of the medium. The very low quantum yield in water is favorable in practical applications, such as cell-staining, resulting in a reduced background fluorescence as we have shown previously for the ICAN dyes [26]. The reduced fluorescence in polar solvents can also be practical for the selective staining of different nonpolar cell compartments such as cell membrane and/or nucleus.

Figure 5.

Dependence of quantum fluorescence yields of the 1,5-disubstituted anthracene dyes on the empirical parameter of solvent polarity ET(30).

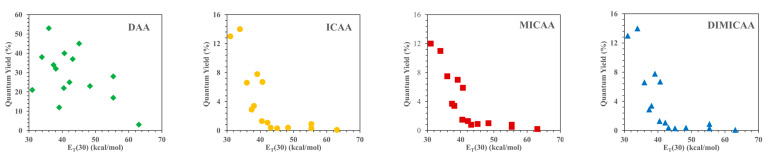

Two of the most common ways to quantify the solvatochromic effect in solvents of different polarity is to plot the fluorescence emission maxima (νEm) as a function of the empirical solvent polarity parameter ET(30) [36] and the Lippert–Mataga (LM) plot [37,38], which are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Variation of the fluorescence emission maximum with the empirical solvent polarity parameter ET(30) (a) and the Lippert–Mataga (LM) (b) plots for the 1,5-disubstituted anthracene dyes.

Interestingly, two groups can be identified: one belonging to the diamine (DAA) and the other to the isocyano (ICAA-DIMICAA) dyes (Figure 6a). In both cases, the correlation is linear between the fluorescence emission maximum and ET(30) for all the anthracene fluorophores. It can be surmised from the corresponding slopes that ICAA, MICAA and DIMICAA have almost the same solvatochromic shift (113–120 kcal−1cm−1mol), while this value is significantly lower for the 1,5-DAA (77 kcal−1cm−1mol) supporting the ICT character of the emission state of ICAA-DIMICAA, which is in good agreement with the computational findings presented in Table 2. It should be noted, however, that because of their strong H-bond donating character (i.e., the solvatochromic response is strongly modulated by specific interactions), protic solvents (iPrOH, MeOH and H2O) were not included in the plot. The plots containing all the solvents are found in the Supplementary Information (Figure S89).

Lippert–Mataga’s Equation (1), which is based on the correlation of energy difference between the ground and excited states (Stokes’ shift) with the solvent orientation polarizability (Δf), can be used to investigate the change in dipole moment between the excited singlet state (µe) and ground state (µg).

| (1) |

where (in cm−1) is the Stokes shift, ε0, h and c are the vacuum permittivity (8.8541 × 10−12 C⋅V−1m−1), Planck constant (h = 6.626 × 10−34 Js), speed of light (c = 299,792,458 m s−1), respectively, and the dipole moment is given in Debye. The Onsager cavity radius (a0), which closely reflects to the radius of a spherical cavity the fluorophore molecule occupies, is either obtained from quantum chemical calculations or by using Suppan’s Equation (2) [39],

| (2) |

where M is the molecular weight of the fluorophore, NA is the Avogadro’s constant and ρ is the density. Δf stands for the orientation polarizability defined as:

| (3) |

where ε and n are the dielectric constant and the refractive index of the solvent, respectively.

After plotting the Stoke’s shift values versus Δf (Figure 6b), the dipole moment change can be calculated from the slope of the plot as:

| (4) |

According to Figure 6b, MICAA has the highest slope (3003 cm−1) obtained from the LM plot, which is closely followed by DIMICAA (2917 cm−1). The smallest slope belongs to DAA (944 cm−1), which is almost twice as small as the corresponding values for ICAA (1752 cm−1). In addition, the Stokes shifts at ΔfLM = 0, i.e., the intercepts of the lines determined from the LM plots, decrease in the order of DIMICAA > ICAA > MICAA > DAA. The difference between the excited and the ground state dipole moments, i.e., Δμ = μE − μG, have been calculated according to Equation (4) and by using the DFT results (Table 2). To calculate Δμ, first, a has to be determined, and instead of using Equation (2), it has been associated with the half distance between the amino and isocyano groups of the corresponding optimized geometries (Table 2). The fully DFT-based dipole moment difference (μE − μG)DFT computed in hexane, dioxane and water are summarized in Table 4 along with the experimental values (μE − μG)LM calculated from Figure 6b using Equation (4).

Table 4.

The dipole moment difference between the excited and the ground state (μE − μG)DFT) calculated by DFT (in various solvents), and the dipole moment differences in the excited and ground state (μE − μG)LM) determined by the Lippert–Mataga equation (Equation (4)).

| (μE − μG)DFT (D) | (μE − μG)LM (D) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hexane | Dioxane | Water | ||

| DAA | −0.39 | −0.41 | −0.65 | 2.22 |

| ICAA | 6.10 | 6.26 | 7.35 | 3.07 |

| MICAA | 7.31 | 7.77 | 9.31 | 3.98 |

| DIMICAA | 7.49 | 7.72 | 9.28 | 3.88 |

| DIA | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

It is evident from the data of Table 4 that the simultaneous presence of one amino and one isocyano group (ICAA, MICAA and DIMICAA) yields a higher dipole moment change than in the case of DAA, and in line with the expectations, DIA with the symmetric structure does not have a dipole moment or dipole moment change. However, contrary to the expectations and DFT calculations, DAA also has a significant dipole moment change (Δμ = 2.22 D). Amongst the molecules studied, only the structure of DIA is planar, and the isocyano groups linearly attached to the ring structure resulted in a Cs symmetric molecule. On the other hand, the structure of DAA has unique structural features in such a way that the aromatic rings are slightly bent which come from the interaction of amine nitrogens with the ring structure. One of the hydrogens in each amine group is almost in the rings’ plane while the other one sticks out of the plane (Figure 7). Since two amine groups are attached to this structure, these hydrogens can be on one side of the rings or on opposite sides. Since the latter conformer has only a permanent dipole moment, we have considered it.

Figure 7.

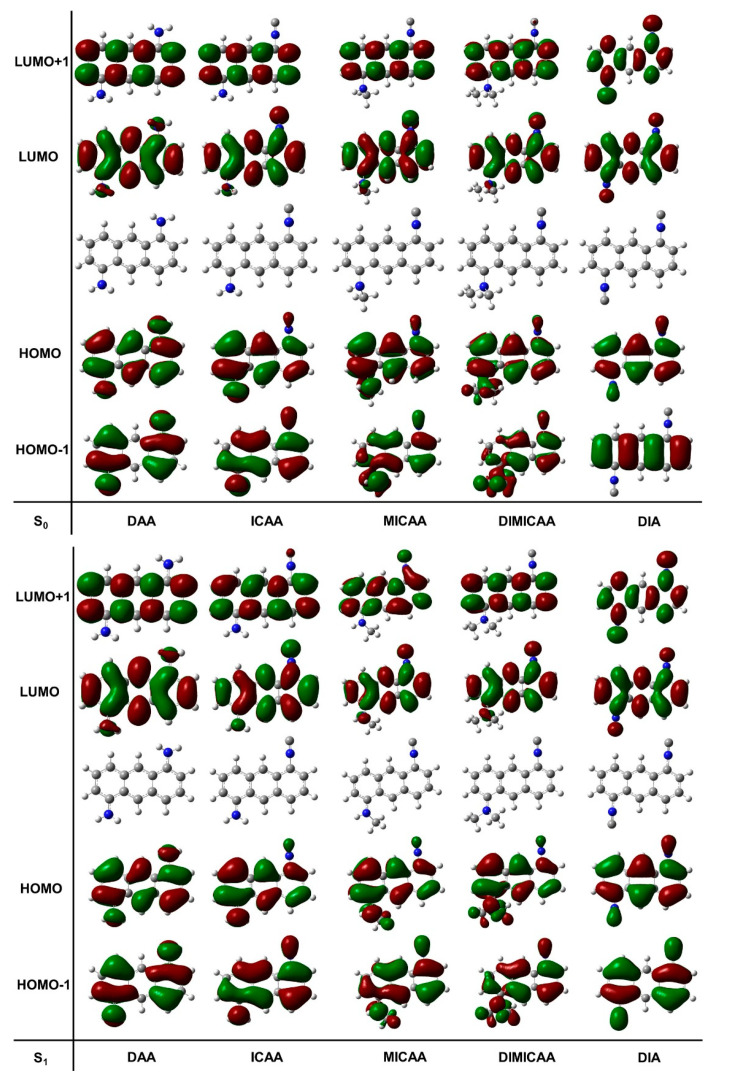

Representation of the relevant molecular orbitals (MO) for the relaxed ground (S0(solv, s0)) and excited states (S1(solv, s1)) of the 1,5-disubstituted anthracene dye structures in dioxane (isovalue for electron density was set to 0.000400 a.u.).

Interestingly, the Δμ values calculated from the Lippert–Mataga equation are half than those obtained by DFT. However, the change of the values from the LM plots are in good agreement with the fully DFT-based results. That is, Δμ changes in the order of 0 D = DIA < DAA < ICAA < MICAA ≅ DIMICAA. In addition, Δμ values are lower for ICAA, MICAA and DIMICAA, while in the case of DAA, Δμ is higher compared to the results in water.

TD-DFT calculations were performed to obtain a deeper understanding of the electronic behavior of the excited states of the studied structures (Figure 7). Optimizations have been carried out on the ground and excited state geometries. The HOMO, LUMO, HOMO-1, LUMO+1 molecular orbitals for all the dye structures in this study are depicted in Figure 7. There are no significant differences between the corresponding ground and excited state molecular orbitals.

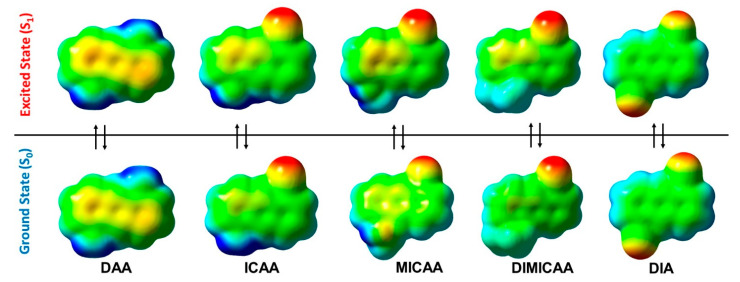

Molecular electrostatic potential (MESP) isosurfaces have also been created for the relaxed ground and excited states as shown in Figure 8. There is no visible difference in the MESPs of the S0 and S1 in the case of the diamino and diisocyano structures, DAA and DIA, respectively (Figure 8). However, a slight difference between the ground and excited state MESPs of ICAA, MICAA and DIMICAA can be seen. However, these cannot be associated with significant changes in the geometries. The largest difference between the S0 and S1 MESPs occurs on the isocyano group in case of MICAA, where a rotation of the methylated amino group is also experienced.

Figure 8.

Molecular electrostatic potential (MESP) isosurfaces (isovalue = 0.02 a.u.) for the relaxed ground (S0(solv, s0)) and excited states (S1(solv, s1)) of the 1,5-disubstituted anthracene dye structures in dioxane (blue color corresponds to +0.045. a.u. (ca. +120 kJ/mol) potential while red represents −0.045 a.u. (ca. −120 kJ/mol)).

3. Materials and Methods

Acetone, dichloromethane (DCM), hexane, 2-propanol (iPrOH), toluene, ethyl-acetate (EtOAc) (reagent grade, Molar Chemicals, Hungary) were purified by distillation. Acetonitrile (MeCN), tetrahydrofuran (THF), methanol (MeOH), dimethyl formamide (DMF), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), pyridine (HPLC grade, VWR, Germany), cyclohexane, 1,4-dioxane (reagent grade, Reanal, Hungary), chloroform, 1,5-diaminoanthraquinone (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) were used without further purification.

NMR: 1H and 13C-NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 and DMSO-d6 at 25 °C on a Bruker Avance DRX-400 and a Bruker AM 360 spectrometer at 400 and 360 MHz, respectively, with tetramethylsilane as the internal standard.

UV–vis: The UV–vis spectra were recorded on an Agilent Cary 60 spectrophotometer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) in a quartz cuvette of 1.00 cm optical length. A 3.00 cm3 solution was prepared from the sample.

3.1. Synthesis

3.1.1 1-Amino-5-Isocyanoanthracene (ICAA) and 1,5-Diisocyanoanthracene (DIA)

In a 250 mL round-bottom flask, 1,5-diaminoanthracene* (1.00 g, 4.80 mmol) and potassium hydroxide (2.69 g, 48.0 mmol) suspended in 50 mL chloroform and 50 mL toluene were stirred for 1 h, then extracted with water. The organic phase was dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, and the solvent was removed on a rotary evaporator. The crude product was purified on a column filled with normal-phase silica gel, using dichloromethane as eluent. Yield: 0.16 g, 15% ICAA (orange-red crystals) and 0.12 g, 11% DIA (pale yellow crystals).

*1,5-Diaminoanthracene was synthesized by the reduction of 1,5-Diaminoanthraquinone according to the literature (Figure 9) [9].

Figure 9.

The synthesis of DAA and ICAA from 1,5-diaminoanthraquinone.

ICAA

1H NMR (360 MHz, DMSO) δ = 8.95 (s, 1H), 8.50 (s, 1H), 8.16 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (dd, J = 17.2, 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.37 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.73 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.09 (s, 2H) ppm (Figure S17).

13C NMR (95 MHz, DMSO) δ = 167.89 (CNC), 145.32 (C1,5), 133.93 (C8a), 131.43 (C6), 129.80 (C4a), 128.91 (C8), 125.43 (C3), 125.22 (C9a), 124.13 (C10a), 123.90 (C7), 123.34 (C9), 120.65 (C4), 115.90 (C10), 106.18 (C2) ppm (Figure S17).

DIA

1H NMR (360 MHz, DMSO) δ = 8.96 (s, 1H), 8.54 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 8.02 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H) ppm (Figure S35).

3.1.2 1-N-Methylamino-5-Isocyanoanthracene (MICAA) and 1-N,N-Dimethylamino-5-Isocyanoanthracene (DIMICAA)

A 250 mL round-bottomed flask, equipped with a magnetic stir bar, was charged with 1-Amino-5-isocyanoanthracene (1.00 g, 4.58 mmol), potassium hydroxide (2.82 g, 50.4 mmol) and absolute dimethyl formamide freshly distilled over phosphorous pentoxide (50 mL). Methyl iodide (2.85 mL, 45.8 mmol) was added to the solution, then the flask was flushed with argon and sealed with a rubber septum. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature, protected from light. After 2 days, 200 mL methylene chloride and 5% ammonia were added, and the solution was extracted 5 times with water, then the organic phase was dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate. Solvent was removed on a rotary evaporator and the residue was purified on a normal-phase silica gel-filled column, using methylene chloride: hexane (1:1) as eluent. Yield: 0.23 g, 22% MICAA (orange crystals) and 0.35 g, 31% DIMICAA (yellow-orange crystals).

MICAA

1H NMR (360 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 8.64 (s, 1H), 8.40 (s, 1H), 8.02 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.55–7.43 (m, 2H), 7.41–7.33 (m, 1H), 6.59 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H), 4.66 (s, 1H), 3.10 (s, 3H) ppm (Figure S53).

DiMICAA

1H NMR (360 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 8.84 (s, 1H), 8.67 (s, 1H), 8.08 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 7.46 (dd, J = 8.4, 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (dd, J = 8.5, 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.07 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 2.97 (s, 6H) ppm (Figure S71).

13C NMR (91 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 167.38 (CNC), 150.87 (C1,5), 134.06 (C8a), 130.95 (C6), 130.69 (C4a), 128.58 (C9a), 126.84 (C8), 125.66 (C10a), 124.38 (C3), 124.27 (C7), 123.53 (C9), 123.36 (C4), 122.28 (C10), 113.77 (C2), 45.24 (CCH3) ppm (Figure S71).

3.2. Fluorescence Measurements

Steady-state fluorescence measurements were carried out using a Jasco FP-8200 fluorescence spectrophotometer equipped with a Xe lamp light source. The excitation and emission spectra were recorded at 20 °C, using 2.5 nm excitation, 5.0 nm emission bandwidth and 200 nm/min scanning speed. Fluorescence quantum yields (ΦF) were calculated by using quinine-sulfate as the reference, using the following equation:

| (5) |

where Φr is the quantum yield of the reference compound (quinine-sulfate in 0.1 mol/L sulfuric acid, absolute quantum efficiency (Φr = 55%)), n is the refractive index of the solvent, I is the integrated fluorescence intensity and A is the absorbance at the excitation wavelength. The absorbances at the wavelength of excitation were kept below A = 0.1 in order to avoid inner filter effects.

For UV–vis and fluorescence measurements, the investigated compounds were dissolved in acetonitrile at a concentration of 1.19 mM and were diluted to 2.38 × 10−5 M and 4.76 × 10−6 M in the solvents in interest. The spectra were processed using Spectragryph software [40].

3.3. Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations

To obtain an explanation for the spectral changes which take into account the electronic structure of the species, a previously tested calculation protocol was adopted [41,42,43]. The geometry optimization of solvated molecules (DAA-DIA) was carried out by using M06 [44] density functional combined with triple-ζ Karlsruhe basis set (TZVP) [45]. The solvent effect on the geometries was mimicked by integral equation formalism of the polarizable continuum model (IEF-PCM) and the solvent cavity for hexane, dioxan and water (solv) was constructed as implemented in Gaussian09 software package. [46] Normal mode analysis was performed to ensure that optimized geometry corresponds to real minima of the potential energy surface (noted as S0(solv, s0)). The harmonic vibrational wavenumbers were used to obtain the thermochemical properties. The first singlet vertical excitation energies (VEE) were computed for each molecule by time dependent (TD) counterpart of M06/TZVP (TD-M06/TZVP). To properly account for nonequilibrium solvation, the corrected linear response formalism was employed [47] via PisaLR protocol [www.dcci.unipi.it/molecolab/tools/white-papers/pisalr (last accessed on 29 December 2021.)]. The calculated VEE values (for S1(solv, s0)) were then compared with the wavenumber at the maximum in experimental excitation spectra (λex,max). The geometry of the first singlet excited states (S1) of molecules were optimized at TD-M06/TZVP level of theory considering equilibrium solvation (S1(solv, s1)). The local minimum nature of each optimized S1 structures were verified by normal mode analysis using numerical Hessian. The maximum of the emission spectra (λem,max) was approximated as energy difference of the first singlet excited (S1(solv, s1)) and ground states (vertical de-excitation) in such a way that nonequilibrium solvation is considered for the ground state (S0(solv, s1)). For both S0(solv, s0)) and S1(solv, s1)), the magnitude of the permanent electric dipole moments (noted μS0 and μS1, respectively) and molecular electrostatic potentials (MESP) of the studied molecules were also calculated by using the M06/TZVP(IEF-PCM) level of theory.

4. Conclusions

The electronic absorption, solvatochromic and photophysical properties of novel 1-amino-5-isocyanoanthracenes (ICAAs) and the synthetically important 1,5-diaminoanthracene (DAA) have been studied. The new isocyano-aminoanthracenes (and to a limited extent DAA) clearly show positive solvatochromic behavior. Contrary to expectations, the symmetrical DAA behaves as a weak solvatochromic dye, and its fluorescence is shifted bathochromically with increasing solvent polarity (λEm = 475 and 511 nm in hexane and DMSO, respectively). DAA is strongly fluorescent in most of the solvents Φf = 21–53% (hexane-dioxane) and its solvatochromic behavior may be explained by the significant change of its dipole moment between excited and ground states (Δμ = 2.22 D). DAA has unique structural features because the aromatic rings are slightly distorted due to the interaction of amine nitrogens with the ring. By replacing one of the amino groups of DAA with isocyanide, the absorption maximum is redshifted 10–20 nm in the case of ICAA and monomethylation of the remaining amino group adds another 10 nm redshift in the case of MICAA. Interestingly, dimethylation results in an opposite effect, and the absorption maxima are found approximately 10 nm lower than in the case of DAA. The molar absorption coefficients in various solvents were slightly lower for ICAA than those of DAA and were found to decrease in the order of DAA > DIMICAA > MICAA > ICAA. The differences in the dipole moments of the excited and ground states were determined by using the Lippert–Mataga equation and DFT calculations. According to DFT calculations, the ICT is limited within the ICAA molecules, that is, no HOMO-LUMO pairs were found that were dominantly located on the amino and isocyano groups. Instead, ICT to the aromatic ring was observed, which is in line with the results obtained from MESP isosurfaces. In contrast to DAA, the Φf rarely exceeds 10% in nonpolar solvents for the isocyano derivatives, and they are practically nonfluorescent in solvents more polar than dioxane. This phenomenon implies the potential application of ICAAs to probe the polarity of the medium. Furthermore, the very low quantum yield in water is favorable in cell-staining, and thus, by using the studied species, even the selective visualization of different non-polar cell compartments (e.g., cell membrane and/or nucleus) is feasible.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms23031315/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.N.; methodology, M.N., B.F., M.S., L.V.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N., M.S., B.F., L.V.; writing—review and editing, B.F., B.V.; supervision, B.V.; funding acquisition, B.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the European Union and the Hungarian State, co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund in the framework of the GINOP-2.3.4-15-2016-00004 project, which aimed to promote the cooperation between the higher education and the industry. Further support has been provided by the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund (Hungary) within the TKP2021-NVA-14 project.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files) or are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bendikov M., Wudl F., Perepichka D.F. Tetrathiafulvalenes, Oligoacenenes and Their Buckminsterfullerene Derivatives: The Brick and Mortar of Organic Electronics. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:4891–4946. doi: 10.1021/cr030666m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anthony J.E. Functionalized Acenes and Heteroacenes for Organic Electronics. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:5028–5048. doi: 10.1021/cr050966z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anthony J.E. The Larger Acenes: Versatile Organic Semiconductors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:452–483. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen L., Hernandez Y., Feng X., Müllen K. From Nanographene and Graphene Nanoribbons to Graphene Sheets: Chemical Synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:7640–7654. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mateo-Alonso A. Pyrene-fused pyrazaacenes: From small molecules to nanoribbons. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43:6311–6324. doi: 10.1039/C4CS00119B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin Y.-Z., Huang C.H., Chang Y.J., Yeh C.-W., Chin T.-M., Chi K.-M., Chou P.-T., Watanabe M., Chow T.J. Anthracene based organic dipolar compounds for sensitized solar cells. Tetrahedron. 2014;70:262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2013.11.072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen M.-H., Nguyen T.-N., Do D.-Q., Nguyen H.-H., Phung Q.-M., Thirumalaivasan N., Wu S.-P., Dinh T.-H. A highly selective fluorescent anthracene-based chemosensor for imaging Zn2+ in living cells and zebrafish. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2020;115:107882. doi: 10.1016/j.inoche.2020.107882. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gómez P., Cerdá J., Más-Montoya M., Georgakopoulos S., da Silva I., García A., Ortí E., Aragó J., Curiel D. Effect of molecular geometry and extended conjugation on the performance of hydrogen-bonded semiconductors in organic thin-film field-effect transistors. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2021;9:10819–10829. doi: 10.1039/D1TC01328A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsumoto H., Nishimura Y., Arai T. Excited-state intermolecular proton transfer dependent on the substitution pattern of anthracene–diurea compounds involved in fluorescent ON1–OFF–ON2 response by the addition of acetate ions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017;15:6575–6583. doi: 10.1039/C7OB01376K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Black H.T., Lin H., Bélanger-Gariépy F., Perepichka D.F. Supramolecular control of organic p/n-heterojunctions by complementary hydrogen bonding. Faraday Discuss. 2014;174:297–312. doi: 10.1039/C4FD00133H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Głowacki E.D., Irimia-Vladu M., Bauer S., Sariciftci N.S. Hydrogen-bonds in molecular solids–from biological systems to organic electronics. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2013;1:3742–3753. doi: 10.1039/c3tb20193g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Irimia-Vladu M., Kanbur Y., Camaioni F., Coppola M.E., Yumusak C., Irimia C.V., Vlad A., Operamolla A., Farinola G.M., Suranna G.P., et al. Stability of Selected Hydrogen Bonded Semiconductors in Organic Electronic Devices. Chem. Mater. 2019;31:6315–6346. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.9b01405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gómez P., Georgakopoulos S., Más-Montoya M., Cerdá J., Pérez J., Ortí E., Aragó J., Curiel D. Improving the Robustness of Organic Semiconductors through Hydrogen Bonding. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021;13:8620–8630. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c18928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feng C., Zhou S., Wang D., Zhao Y., Liu S., Li Z., Braunstein P. Cooperativity in Highly Active Ethylene Dimerization by Dinuclear Nickel Complexes Bearing a Bifunctional PN Ligand. Organometallics. 2021;40:184–193. doi: 10.1021/acs.organomet.0c00683. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Más-Montoya M., Gómez P., Curiel D., Da Silva I., Wang J., Janssen R.A.J. A Self-Assembled Small-Molecule-Based Hole-Transporting Material for Inverted Perovskite Solar Cells. Chem. A Eur. J. 2020;26:10276–10282. doi: 10.1002/chem.202000005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wright T., Tomkovic T., Hatzikiriakos S.G., Wolf M.O. Photoactivated Healable Vitrimeric Copolymers. Macromolecules. 2018;52:36–42. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.8b01898. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo Z., Sun P., Zhang X., Lin J., Shi T., Liu S., Sun A., Li Z. Amorphous Porous Organic Polymers Based on Schiff-Base Chemistry for Highly Efficient Iodine Capture. Chem. Asian J. 2018;13:2046–2053. doi: 10.1002/asia.201800698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi T., Zheng Q.-D., Zuo W.-W., Liu S.-F., Li Z.-B. Bimetallic aluminum complexes supported by bis(salicylaldimine) ligand: Synthesis, characterization and ring-opening polymerization of lactide. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2017;36:149–156. doi: 10.1007/s10118-018-2039-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li X.-Z., Zhou L.-P., Yan L.-L., Yuan D.-Q., Lin C.-S., Sun Q.-F. Evolution of Luminescent Supramolecular Lanthanide M2nL3n Complexes from Helicates and Tetrahedra to Cubes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:8237–8244. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b02764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuster S., Geiger T. Coupled π-conjugated chromophores: Squaraine dye dimers as two connected pendulums. Dye. Pigment. 2015;113:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.dyepig.2014.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rácz D., Nagy M., Mándi A., Zsuga M., Kéki S. Solvatochromic properties of a new isocyanonaphthalene based fluorophore. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2013;270:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2013.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lakowicz J.R. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Springer; New York, NY, USA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marini A., Muñoz-Losa A., Biancardi A., Mennucci B. What is Solvatochromism? J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:17128–17135. doi: 10.1021/jp1097487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagy M., Rácz D., Lázár L., Purgel M., Ditrói T., Zsuga M., Kéki S. Solvatochromic Study of Highly Fluorescent Alkylated Isocyanonaphthalenes, Their π-Stacking, Hydrogen-Bonding Complexation, and Quenching with Pyridine. Chemphyschem. 2014;15:3614–3625. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201402310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagy M., Rácz D., Nagy Z.L., Nagy T., Fehér P.P., Purgel M., Zsuga M., Kéki S. An acrylated isocyanonaphthalene based solvatochromic click reagent: Optical and biolabeling properties and quantum chemical modeling. Dye. Pigm. 2016;133:445–457. doi: 10.1016/j.dyepig.2016.06.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagy M., Rácz D., Nagy Z.L., Fehér P.P., Kalmár J., Fábián I., Kiss A., Zsuga M., Kéki S. Solvatochromic isocyanonaphthalene dyes as ligands for silver(I) complexes, their applicability in silver(I) detection and background reduction in biolabelling. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018;255:2555–2567. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2017.09.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagy M., Kéki S., Rácz D., Mathur J., Vereb G., Garda T., M-Hamvas M., Chaumont F., Bóka K., Böddi B., et al. Novel fluorochromes label tonoplast in living plant cells and reveal changes in vacuolar organization after treatment with protein phosphatase inhibitors. Protoplasma. 2017;255:829–839. doi: 10.1007/s00709-017-1190-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagy Z., Nagy M., Kiss A., Rácz D., Barna B., Konczol P., Bankó C., Bacsó Z., Kéki S., Bánfalvi G., et al. MICAN, a new fluorophore for vital and non-vital staining of human cells. Toxicol. Vitr. 2018;48:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagy M., Kovács S.L., Nagy T., Rácz D., Zsuga M., Kéki S. Isocyanonaphthalenes as extremely low molecular weight, selective, ratiometric fluorescent probes for Mercury(II) Talanta. 2019;201:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2019.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagy M., Szemán-Nagy G., Kiss A., Nagy Z.L., Tálas L., Rácz D., Majoros L., Tóth Z., Szigeti Z.M., Pócsi I., et al. Antifungal Activity of an Original Amino-Isocyanonaphthalene (ICAN) Compound Family: Promising Broad Spectrum Antifungals. Molecules. 2020;25:903. doi: 10.3390/molecules25040903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagy M., Rácz D., Nagy Z.L., Fehér P.P., Kovács S.L., Bankó C., Bacsó Z., Kiss A., Zsuga M., Kéki S. Amino-isocyanoacridines: Novel, Tunable Solvatochromic Fluorophores as Physiological pH Probes. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:8250. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-44760-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bankó C., Nagy Z.L., Nagy M., Szemán-Nagy G.G., Rebenku I., Imre L., Tiba A., Hajdu A., Szöllősi J., Kéki S., et al. Isocyanide Substitution in Acridine Orange Shifts DNA Damage-Mediated Phototoxicity to Permeabilization of the Lysosomal Membrane in Cancer Cells. Cancers. 2021;13:5652. doi: 10.3390/cancers13225652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berlman I.B. Handbook of Fluorescence Spectra of Aromatic Molecules. Academic Press; New York, NY, USA: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poteau X., Brown A.I., Brown R.G., Holmes C., Matthew D. Fluorescence switching in 4-amino-1,8-naphthalimides: “on–off–on” operation controlled by solvent and cations. Dye. Pigment. 2000;47:91–105. doi: 10.1016/S0143-7208(00)00067-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Staneva D., Vasileva-Tonkova E., Grabchev I. Chemical modification of cotton fabric with 1,8-naphthalimide for use as heterogeneous sensor and antibacterial textile. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2019;382:111924. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2019.111924. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reichardt C. Solvatochromic Dyes as Solvent Polarity Indicators. Chem. Rev. 1994;94:2319–2358. doi: 10.1021/cr00032a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lippert E. Dipolmoment und Elektronenstruktur von angeregten Molekülen. Z. Für Nat. A. 1955;10:541–545. doi: 10.1515/zna-1955-0707. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mataga N., Kaifu Y., Koizumi M. The Solvent Effect on Fluorescence Spectrum, Change of Solute-Solvent Interaction during the Lifetime of Excited Solute Molecule. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1955;28:690–691. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.28.690. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suppan P. Excited-state dipole moments from absorption/fluorescence solvatochromic ratios. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1983;94:272–275. doi: 10.1016/0009-2614(83)87086-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Menges F. “Spectragryph—Optical Spectroscopy Software”, Version 1.2.15. 2020. [(accessed on 30 December 2021)]. Available online: http://www.effemm2.de/spectragryph/

- 41.Kovács S.L., Nagy M., Fehér P.P., Zsuga M., Kéki S. Effect of the Substitution Position on the Electronic and Solvatochromic Properties of Isocyanoaminonaphthalene (ICAN) Fluorophores. Molecules. 2019;24:2434. doi: 10.3390/molecules24132434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kovács E., Faigl F., Mucsi Z. Regio- and Diastereoselective Synthesis of 2-Arylazetidines: Quantum Chemical Explanation of Baldwin’s Rules for the Ring-Formation Reactions of Oxiranes. J. Org. Chem. 2020;85:11226–11239. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.0c01310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kovács E., Cseri L., Jancsó A., Terényi F., Fülöp A., Rózsa B., Galbács G., Mucsi Z. Synthesis and Fluorescence Mechanism of the Aminoimidazolone Analogues of the Green Fluorescent Protein: Towards Advanced Dyes with Enhanced Stokes Shift, Quantum Yield and Two-Photon Absorption. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2021;2021:5649–5660. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.202101173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao Y., Truhlar D.G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: Two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2008;120:215–241. doi: 10.1007/s00214-007-0310-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schäfer A., Huber C., Ahlrichs R. Fully optimized contracted Gaussian basis sets of triple zeta valence quality for atoms Li to Kr. J. Chem. Phys. 1994;100:5829–5835. doi: 10.1063/1.467146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miertuš S., Scrocco E., Tomasi J. Electrostatic interaction of a solute with a continuum. A direct utilization of AB initio molecular potentials for the prevision of solvent effects. Chem. Phys. 1981;55:117–129. doi: 10.1016/0301-0104(81)85090-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Caricato M., Mennuccia B., Tomasi J., Ingrosso F., Cammi R., Corni S., Scalmani G. Formation and relaxation of excited states in solution: A new time dependent polarizable continuum model based on time dependent density functional theory. J. Chem. Phys. 2006;124:124520. doi: 10.1063/1.2183309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files) or are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.