Abstract

The p44 gene of the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (aoHGE) encodes a 44-kDa major outer surface protein. A technique was developed for the typing of the aoHGE based on the PCR amplification of the p44 gene followed by a multiple restriction digest with HindIII, EcoRV, and AspI to generate restriction fragment length polymorphism patterns. Twenty-four samples of the aoHGE were collected from geographically dispersed sites in the United States and included isolates from humans, equines, canines, small mammals, and ticks. Six granulocytic ehrlichiosis (GE) types were identified. The GE typing method is relatively simple to perform, is reproducible, and is able to differentiate among the various isolates of granulocytic ehrlichiae in the United States. These characteristics suggest that this GE typing method may be an important epizootiological and epidemiological tool.

Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) is an emerging infectious disease first reported in the Unites States in 1994 (7). The disease is caused by an as-yet unnamed Ehrlichia species similar or identical to Ehrlichia equi and Ehrlichia phagocytophila, which are known veterinary pathogens. Clinical symptoms of HGE include fever, myalgias, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia (1, 3). HGE can be treated readily with tetracyclines; however, the disease has proven fatal for several patients with serious underlying medical conditions (3, 13, 18).

Most cases of HGE are reported from the northeast and upper midwestern United States. The four states reporting the highest overall incidence of HGE are New York, Connecticut, Wisconsin, and Minnesota (21). The geographic locations of reported cases correspond to the natural habitat of the implicated tick vectors. In the northeast and upper midwestern United States, the agent of HGE (aoHGE) is transmitted to humans by the black-legged tick, Ixodes scapularis (8, 14, 24, 25, 31), and in the western United States it is transmitted to humans by Ixodes pacificus (4, 5, 9, 26, 27). The HGE agent can also infect a variety of small mammals. HGE agent has been detected by PCR or culture in white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus) (25, 30), deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus) (23, 33), meadow voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus) (32), eastern chipmunks (Tamias striatus) (32), and dusky-footed woodrats (Neotoma fuscipes) (20, 23). One drawback to studying the epidemiology and epizootiology of HGE is that, at present, there is no standard typing method to distinguish between unique strains of the HGE agent. Attempts to compare 16S sequences and the ank gene sequences of isolates of the HGE agent have shown little or no variability (6, 19).

We investigated the possibility of using the gene that encodes the P44 protein for the typing of the aoHGE. P44 is the designated name of a family of HGE agent outer membrane surface proteins. P44 is capable of eliciting immunogenic responses in infected patients (2, 16, 34). The gene that encodes the outer membrane protein P44 is present in multiple copies in the genome and has shown significant sequence diversity. The p44 gene was first cloned and sequenced by Ijdo et al. (17) and is homologous to the multigene family msp-2 genes in Anaplasma marginales (22). Zhi et al. (35) have estimated the copy number of the p44 gene at 18 to 22. They are of different sizes and are randomly dispersed throughout the HGE agent genome. Zhi and coworkers have reported the transcription of at least 5 copies of the p44 gene by reverse transcription-PCR (35). This indication of genetic diversity makes p44 an attractive target for restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis. PCR amplification of specific gene sequences followed by RFLP analysis has been used successfully to type other organisms, such as Helicobacter pylori (29), Staphylococcus aureus (15), Borrelia spp. (10), and Rickettsia spp. (11).

Bacterial isolates were supplied as viable cultures or DNA extracts as described in Table 1. The HGE agents were cultivated in the HL60 cell line (CCL240; American Type Culture Collection), grown in RPMI 1640 (Gibco, Grand Island, N.Y.) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) at 37°C with 5% CO2 as described by Goodman et al. (12). The HL60 cells were harvested by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min when greater than 70% of the HL60 cells had visible morulae upon microscopic examination of Giemsa-stained cytospin preparations. The cellular DNA was extracted from the HGE-infected HL60 cells using the guanidium isothiocyanate method (IsoQuick; ORCA Research Industries, Inc., Bothell, Wash.). The purified HGE agent DNA was used as template DNA in the PCR. The 50 μl of PCR contained 25 ml of Taq PCR Master Mix (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, Calif.), 1 to 5 μl of DNA template (about 0.5 μg of DNA), 5 μl of each primer (10 pmol/μl), and distilled water to bring the reaction mixture to a volume of 50 μl. The primers used were previously published by Ijdo et al.: 5′AGCGTAATGATGTCT ATGGC-3′ and 5′-ACCCTAACACCAAATTCCC-3′, which amplify a 1,279-bp portion of the p44 gene (17). The PCR was carried out by denaturation at 94°C for 2 min and then 40 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 58°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 3 min (1 s was automatically added to each consecutive extension cycle), followed by a final cycle at 72°C for 7 min in a model 4800 thermal cycler (Perkin Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.). About 40 μl of the PCR of the p44 gene was transferred to the appropriate well in 1% agarose gel and run by electrophoresis in 0.5× TBE buffer (0.5× TBE is 45 mM Tris-borate plus 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) at 50 V for 3 h. The agarose gel was stained with ethidium bromide. The amplified p44 gene of 1,279 bp was excised from the agarose gel under the illumination of UV light and then was extracted and purified using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit following the instructions of the manufacturer (Qiagen Inc.). The purified 1,279-bp p44 band described above was digested by a mixture of enzymes HindIII, AspI, and EcoRV in a 20- to 30-μl reaction mixture containing 10 to 15 μl of p44 DNA purified from gel containing about 0.4 to 0.6 μg of DNA, 1× reaction buffer B, and 5 to 8 U of each endonuclease (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.). The reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The reaction mixture was loaded onto a 2% agarose gel containing 1 mM ethidium bromide and electrophoresed at 50 V for 3 h. The gel was electrophoresed longer than 3 h to separate closely sized DNA bands. The restriction digestion of purified p44 DNA from different isolates was repeated at least 2 times with various amounts of DNA to confirm complete digestion and to obtain the best concentration for effective resolution of the bands by gel electrophoresis. The gels were then viewed on a UV transilluminator box and photographed on high-speed film (Polaroid Corporation, Cambridge, Mass.). The sizes of all the DNA fragments were calculated using the method of Schaffer and Sederoff (28).

TABLE 1.

Source of HGE specimens

| Sample | Source | State | Provided by |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1003 | Meadow vole (M. pennsylvanicus) | Minn. | Johnsona |

| 1007 | Eastern chipmunk (T. striatus) | Minn. | Johnson |

| 1008 | Eastern chipmunk (T. striatus) | Minn. | Johnson |

| 1011 | White-footed mouse (P. leucopus) | Minn. | Johnson |

| 1014 | Eastern chipmunk (T. striatus) | Minn. | Johnson |

| 1023 | Meadow vole (M. pennsylvanicus) | Minn. | Johnson |

| 1026 | Eastern chipmunk (T. striatus) | Minn. | Johnson |

| 1029 | White-footed mouse (P. leucopus) | Minn. | Johnson |

| 1033 | Southern red-backed vole (Clethrionomys gapperi) | Minn. | Johnson |

| PL59 | White-footed mouse (P. leucopus) | Minn. | Johnson |

| HGE-1 | Human | Minn. | Goodmanb |

| HGE-2 | Human | Minn. | Goodman |

| HGE-3 | Human | Minn. | Goodman |

| HGE-4 | Human | Wis. | Goodman |

| HGE-5 | Human | N.Y. | Goodman |

| HGE-6 | Human | N.Y. | Goodman |

| Martin | Canine | Minn. | Munderlohc |

| Equi | Equine (E. equi MRK strain) | Calif. | Munderloh |

| GOM2 | Tick (I. spinipalpis) | Colo. | Piesmand |

| GOM4 | Tick (I. spinipalpis) | Colo. | Piesman |

| TB41 | Mexican wood rat (Neotoma mexicana) | Colo. | Piesman |

| TB64 | Deer mouse (P. maniculatus) | Colo. | Piesman |

| TB90 | Deer mouse (P. maniculatus) | Colo. | Piesman |

| TB108 | Mexican wood rat (N. mexicana) | Colo. | Piesman |

Cultures from mammals trapped in Morrison and Washington counties, Minn.

Cultures supplied by Jesse Goodman, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

Cultures supplied by Ulrike Munderloh, University of Minnesota, St. Paul.

DNA extracts supplied by Joseph Piesman and William Nicholson, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Fort Collins, Colo.

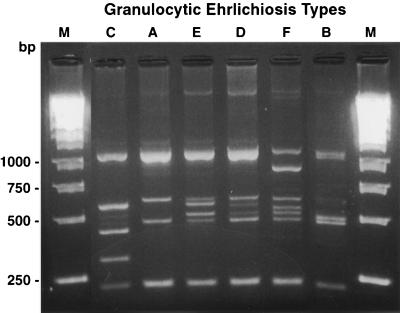

Twenty-four samples of the aoHGE were collected from geographically dispersed sites. The sites consisted of the northeastern (New York), north-central (Minnesota and Wisconsin), and western (Colorado and California) regions of the United States. The specimens were obtained from a variety of hosts, which included humans, equines, canines, small mammals, and ticks. All specimens were examined by RFLP-PCR. The RFLP patterns consisted of 4 to 7 bands that ranged in size from 225 to 1,100 bp. All specimens contained a 1,100-bp and a 225-bp band but varied in the sizes of the remaining bands. The banding patterns were separated into six granulocytic ehrlichiosis (GE) types, A to F (Table 2). Representative gel patterns of the GE types are shown in Fig. 1. Control DNA from the agent of monocytic ehrlichiosis, Ehrlichia chafeensis, and normal mouse spleen were nonreactive with the HGE p44 specific primers.

TABLE 2.

GE types characterized by restriction fragment sizes

| GE type | Fragment sizes (bp) |

|---|---|

| Aa | 1,100, 610, 470, 225 |

| B | 1,100, 490, 480, 225 |

| C | 1,100, 570, 430, 310, 225 |

| D | 1,100, 610, 560, 490, 470, 225 |

| E | 1,100, 610, 570, 490, 470, 225 |

| Fb | 1,100, 890, 600, 530, 490, 470, 225 |

May also have a faint band at 750 bp.

May also have a band at 340 bp.

FIG. 1.

RFLP patterns of GE types A through F. The lanes labeled M contain molecular size markers (Kb DNA Ladder; Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.)

The geographical distribution of the six GE types of the aoHGE from the various hosts analyzed are shown in Table 3. Although the number of samples from the northeast and the western regions were limited, the results suggest that this typing method has strong discriminatory potential. GE types B and F were present in Colorado, and types C, D, and E were found in the north-central states (Minnesota and Wisconsin). In contrast, GE type A was present in specimens from California, Minnesota, and New York.

TABLE 3.

GE types, hosts, and geographical locations

| Host | State

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New York | Minnesota | Wisconsin | Colorado | California | |

| Human | A A | C C C | E | ||

| Equine | A | ||||

| Canine | C | ||||

| White-footed mouse | A A D | ||||

| Deer mouse | B F | ||||

| Eastern chipmunk | C D E E | ||||

| Southern red-backed vole | C | ||||

| Meadow vole | A A | ||||

| Mexican wood rat | F F | ||||

| I. spinipalpis | F F | ||||

Three GE types were identified among the six human specimens. They were type A for the two New York patients, type C for the three Minnesota patients, and type E for the Wisconsin isolate. The Minnesota canine isolate was GE type C, the same GE type as that of the three Minnesota human isolates. The Minnesota human isolate, type C, was also present in a chipmunk and a southern red-backed vole from Minnesota. The Wisconsin human isolate, type E, was also present in eastern chipmunks captured in Minnesota. The GE type A, present in the two New York human isolates, was also present in white-footed mice and meadow voles from Minnesota as well as a horse isolate from California (Table 3). Four different GE types were represented among the 14 isolates of the aoHGE from Minnesota. GE type F, present in the Mexican wood rat and the deer mouse from Colorado, was also identified in the tick vector, Ixodes spinipalpis.

We investigated the stability of the GE type in two isolates, one from a human and one from a white-footed mouse. The human isolate was determined to be GE type C at tissue culture passage number 15, and after 164 passages in HL60 cells it remained type C. A white-footed mouse isolate was identified as GE type A at its second passage in HL60 cells. Its GE type remained type A after isolation from an experimentally infected mouse, 1 week postinoculation, and following 48 passages in HL60 cells. Based on the above typing results of these two aoHGE isolates, we conclude that the GE type is a stable characteristic.

The GE typing method we described is relatively simple to perform, is very reproducible, and appears to be a sensitive means to differentiate among the various isolates of granulocytic ehrlichiae. Another advantage of this technique is that it can be performed on animal and human specimens without the need to cultivate the organism. These characteristics suggest that the GE typing method has the potential of being an important epizootiological and epidemiological tool.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following persons for providing cultures or DNA extracts of the HGE agent: Jesse Goodman, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis; Uli Munderloh, University of Minnesota, St. Paul; and William Nicholson and Joseph Piesman, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Fort Collins, Colo. We also thank the personnel at Camp Ripley, Little Falls, Minn., and the Metropolitan Mosquito Control District, St. Paul, Minn., for providing animal specimens.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aguero-Rosenfeld M E, Horowitz H W, Wormser G P, McKenna D F, Nowakowski J, Munoz J, Dumler J S. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis: a case series from a medical center in New York State. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:904–908. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-11-199612010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asanovich K M, Bakken J S, Madigan J E, Aguero-Rosenfeld M, Wormser G P, Dumler J S. Antigenic diversity of granulocytic Ehrlichia isolates from humans in Wisconsin and New York and a horse in California. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1029–1034. doi: 10.1086/516529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakken J S, Krueth J, Wilson-Nordskog C, Tilden R L, Asanovich K, Dumler J S. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. JAMA. 1996;275:199–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barlough J E, Madigan J E, DeRock E, Bigornia L. Nested polymerase chain reaction for detection of Ehrlichia equi genomic DNA in horses and ticks (Ixodes pacificus) Vet Parasitol. 1996;63:319–329. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(95)00904-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barlough J E, Madigan J E, Kramer V L, Clover J R, Hui L T, Webb J P, Vredevoe L K. Ehrlichia phagocytophila genogroup rickettsiae in ixodid ticks from California collected in 1995 and 1996. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2018–2021. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.8.2018-2021.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chae J, Foley J E, Dumler J S, Madigan J E. Comparison of the nucleotide sequences of 16S rRNA, 444 Ep-Ank, and groESL heat shock operon genes in naturally occurring Ehrlichia equi and human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent isolates from northern California. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1364–1369. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.4.1364-1369.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen S M, Dumler J S, Bakken J S, Walker D H. Identification of a granulocytotropic Ehrlichia species as the etiologic agent of human disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:589–595. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.3.589-595.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Des Vignes F, Fish D. Transmission of the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis by host-seeking Ixodes scapularis (Acari:Ixodidae) in southern New York state. J Med Entomol. 1997;34:379–382. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/34.4.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foley J E, Crawford-Miksza L, Dumler J S, Glaser C, Chae J S, Yeh E, Schnurr D, Hood R, Hunter W, Madigan J E. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in northern California: two case descriptions with genetic analysis of the Ehrlichiae. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:388–392. doi: 10.1086/520220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fukunaga M, Okada K, Nakao M, Konishi T, Sato Y. Phylogenetic analysis of Borrelia species based on flagellin gene sequences and its application for molecular typing of Lyme disease borreliae. Int J Sys Bacteriol. 1996;46:898–905. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-4-898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gage K L, Schrumpf M E, Karstens R H, Burgdorfer W, Schwan T G. DNA typing of rickettsiae in naturally infected ticks using a polymerase chain reaction/restriction fragment length polymorphism system. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;50:247–260. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.50.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodman J L, Nelson C M, Vitale B, Madigan J E, Dumler J S, Kurtti T J, Munderloh U G. Direct cultivation of the causative agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. N Eng J Med. 1996;334:209–215. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601253340401. . (Erratum, 335:361.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardalo C J, Quagliarello V, Dumler J S. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Connecticut: report of a fatal case. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:910–914. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.4.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hodzic E, Fish D, Maretzki C M, De Silva A M, Feng S, Barthold S W. Acquisition and transmission of the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis by Ixodes scapularis ticks. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3574–3578. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.12.3574-3578.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hookey J V, Richardson J F, Cookson B D. Molecular typing of Staphylococcus aureus based on PCR restriction fragment length polymorphism and DNA sequence analysis of the coagulase gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1083–1089. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.4.1083-1089.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ijdo J W, Zhang Y, Hodzic E, Magnarelli L A, Wilson M L, Telford III S R, Barthold S W, Fikrig E. The early humoral response in human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:687–692. doi: 10.1086/514091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ijdo J W, Sun W, Zhang Y, Magnarelli L A, Fikrig E. Cloning of the gene encoding the 44-kilodalton antigen of the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis and characterization of the humoral response. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3264–3269. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3264-3269.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jahangir A, Kolbert C, Edwards W, Mitchell P, Dumler J S, Persing D H. Fatal pancarditis associated with human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in a 44-year-old man. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:1424–1427. doi: 10.1086/515014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Massung R F, Owens J H, Ross D, Reed K D, Petrovec M, Bjoersdorff A, Coughlin R T, Beltz G A, Murphy C I. Sequence analysis of the ank gene of granulocytic ehrlichiae. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2917–2922. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.8.2917-2922.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maupin G O, Gage K L, Piesman J, Montenieri J, Sviat S L, VanderZanden L, Happ C M, Dolan M, Johnson B J. Discovery of an enzootic cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi in Neotoma mexicana and Ixodes spinipalpis from northern Colorado, an area where Lyme disease is nonendemic. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:636–643. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.3.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McQuiston J H, Paddock C D, Holman R C, Childs J E. The human ehrlichioses in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:635–642. doi: 10.3201/eid0505.990504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murphy C I, Storey J R, Recchia J, Doros-Richert L A, Gingrich-Baker C, Munroe K, Bakken J S, Coughlin R T, Beltz G A. Major antigenic proteins of the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis are encoded by members of a multigene family. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3711–3718. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3711-3718.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicholson W L, Castro M B, Kramer V L, Sumner J W, Childs J E. Dusky-footed wood rats (Neotoma fuscipes) as reservoirs of granulocytic Ehrlichiae (Rickettsiales: Ehrlichieae) in northern California. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3323–3327. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.10.3323-3327.1999. . (Erratum, 37:4206.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pancholi P, Kolbert C P, Mitchell P D, Reed K D, Dumler J S, Bakken J S, Telford III S R, Persing D H. Ixodes dammini as a potential vector of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1007–1012. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.4.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ravyn M D, Kodner C B, Carter S E, Jarnefeld J L, Johnson R C. Isolation of the etiologic agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis from the white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus) J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:335–338. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.1.335-338.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reubel G H, Kimsey R B, Barlough J E, Madigan J E. Experimental transmission of Ehrlichia equi to horses through naturally infected ticks (Ixodes pacificus) from northern California. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2131–2134. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.7.2131-2134.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richter P J, Jr, Kimsey R B, Madigan J E, Barlough J E, Dumler J S, Brooks D L. Ixodes pacificus (Acari:Ixodidae) as a vector of Ehrlichia equi (Rickettsiales: Ehrlichieae) J Med Entomol. 1996;33:1–5. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/33.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schaffer H E, Sederoff R R. Improved estimation of DNA fragment lengths from agarose gels. Anal Biochem. 1981;115:113–122. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90533-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shortridge V D, Stone G G, Flamm R K, Beyer Versalovic J, Graham D W, Tanaka S K. Molecular typing of Helicobacter pylori isolates from a multicenter U.S. clinical trial by ureC restriction fragment length polymorphism. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:471–473. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.2.471-473.1997. . (Erratum, 36:1468, 1998.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stafford K C, Massung R F, Magnarelli L A, Ijdo J W, Anderson J F. Infection with agents of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis, Lyme disease, and babesiosis in wild white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus) in Connecticut. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2887–2892. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.9.2887-2892.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Telford III S R, Dawson J E, Katavolos P, Warner C K, Kolbert C P, Persing D H. Perpetuation of the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in a deer tick-rodent cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6209–6214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.6209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walls J J, Greig B, Neitzel D F, Dumler J S. Natural infection of small mammal species in Minnesota with the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:853–855. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.853-855.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeidner N S, Burkot T R, Massung R, Nicholson W L, Dolan M C, Rutherford J S, Biggerstaff B J, Maupin G O. Transmission of the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis by Ixodes spinipalpis ticks: evidence of an enzootic cycle of dual infection with Borrelia burgdorferi in northern Colorado. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:616–619. doi: 10.1086/315715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhi N, Ohashi N, Rikihisa Y, Horowitz H W, Wormser G P, Hechemy K. Cloning and expression of the 44-kilodalton major outer membrane protein gene of the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent and application of the recombinant protein to serodiagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1666–1673. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.6.1666-1673.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhi N, Ohashi N, Rikihisa Y. Multiple p44 genes encoding major outer membrane proteins are expressed in the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17828–17836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]