Keywords: ammoniagenesis, connecting tubule, renal cortex, renal microcirculation, tubuloglomerular feedback

Abstract

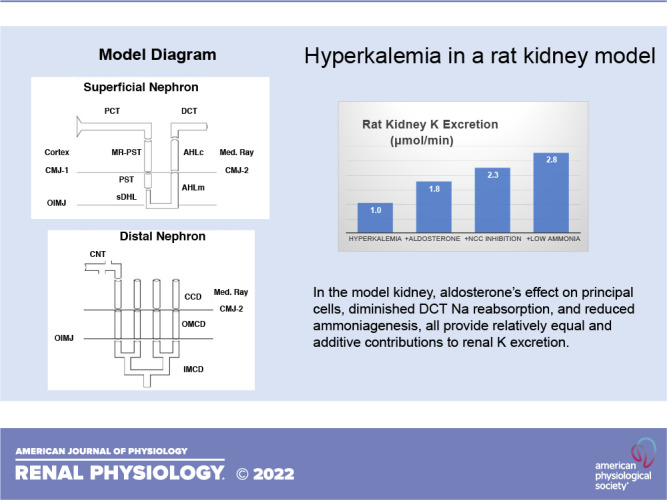

The renal response to acute hyperkalemia is mediated by increased K+ secretion within the connecting tubule (CNT), flux that is modulated by tubular effects (e.g., aldosterone) in conjunction with increased luminal flow. There is ample evidence that peritubular K+ blunts Na+ reabsorption in the proximal tubule, thick ascending Henle limb, and distal convoluted tubule (DCT). Although any such reduction may augment CNT delivery, the relative contribution of each is uncertain. The kidney model of this laboratory was recently advanced with representation of the cortical labyrinth and medullary ray. Model tubules capture the impact of hyperkalemia to blunt Na+ reabsorption within each upstream segment. However, this forces the question of the extent to which increased Na+ delivery is transmitted past the macula densa and its tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF) signal. Beyond increasing macula densa Na+ delivery, peritubular K+ is predicted to raise cytosolic Cl− and depolarize macula densa cells, which may also activate TGF. Thus, although the upstream reduction in Na+ transport may be larger, it appears that the DCT effect is critical to increasing CNT delivery. Beyond the flow effect, hyperkalemia reduces ammoniagenesis and reduced ammoniagenesis enhances K+ excretion. What this model provides is a possible mechanism. When cortical is taken up via peritubular Na+-K+()-ATPase, it acidifies principal cells. Consequently, reduced ammoniagenesis increases principal cell pH, thereby increasing conductance of both the epithelial Na+ channel and renal outer medullary K+ channel, enhancing K+ excretion. In this model, the effect of aldosterone on principal cells, diminished DCT Na+ reabsorption, and reduced ammoniagenesis all provide relatively equal and additive contributions to renal K+ excretion.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Hyperkalemia blunts Na+ reabsorption along the nephron, and increased CNT Na+ delivery facilitates K+ secretion. The model suggests that tubuloglomerular feedback limits transmission of proximal effects past the macula densa, so that it is DCT transport that is critical. Hyperkalemia also reduces PCT ammoniagenesis, which enhances K+ excretion. The model suggests a mechanism, namely, that reduced cortical ammonia impacts CNT transport by raising cell pH and thus increasing both ENaC and ROMK conductance.

INTRODUCTION

The kidney copes with hyperkalemia by dramatically increasing K+ excretion, at times to levels greater than the amount of filtered K+ (1). The capacity for renal tubular K+ secretion was demonstrated by micropuncture of the rat cortical distal nephron, specifically the connecting tubule (CNT), which revealed increasing K+ flow along the lumen (2, 3). Within the CNT and collecting duct (CD), K+ secretion is the product of principal cell transporters: luminal membrane epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC)-mediated Na+ reabsorption, peritubular membrane Na+/K+ exchange via Na+-K+-ATPase, and luminal membrane channel-mediated K+ secretion [renal outer medullary K+ channel (ROMK)] (4, 5). CNT K+ secretion increases in response to hyperkalemia, and upregulation of ENaC by aldosterone and other signals is well established. Beyond the impact of principal cell transporter activity, it has long been known that CNT K+ secretion is enhanced when Na+ delivery to this segment is increased, principally by increasing luminal flow rate (6, 7). Recently, the K+-induced increment in CNT Na+ delivery has attracted intense interest, prompted by recognition that distal convoluted tubule (DCT) Na+ reabsorption is downregulated by hyperkalemia (8). This is a direct effect of peritubular K+ to decrease DCT luminal membrane NaCl cotransporter (NCC) activity (9, 10). What is less secure is the quantitative importance of this reduction in DCT Na+ transport, in the context of the full nephron. Specifically, high peritubular K+ can acutely blunt proximal tubule (PT) Na+ reabsorption (11), which is distinct from the observation that chronic dietary K+ loading reduces Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 3 (NHE3) density (12). It has also been demonstrated in microperfused ascending Henle limbs that increases in peritubular K+ decrease Na+ reabsorption from that segment (13). Experimental studies have not clearly delineated the relative contribution of each of these upstream sites to the increase in CNT Na+ delivery. One additional tubular response to hyperkalemia is a reduction in ammoniagenesis within PTs (14, 15). The mechanism by which this change in ammonia metabolism contributes to enhancing renal K+ excretion has not been addressed.

Mathematical modeling has been used to estimate the quantitative significance of observed or proposed transport changes in response to hyperkalemia. At the segmental level, a CNT model has provided a map depicting the interplay of delivered Na+ concentration and tubular flow rate in modulating K+ secretion (16). Models of both the ascending Henle limb (AHL) (17) and of the DCT (9) have captured the impact of increases in blood K+ to increase cytosolic Cl− concentration. Higher cytosolic Cl− can blunt luminal Na+ entry in these segments through purely kinetic considerations, and this is captured by the models. However, within the DCT the more important regulation of luminal Na+ entry derives from Cl−-dependent regulatory cascades that ultimately phosphorylate NCC (18). A multisegment model of the distal nephron (DCT-CNT-CD) provided a map of the interplay of DCT Na+ reabsorption and CNT K+ secretion, as a surrogate for angiotensin and aldosterone effects (19). A whole kidney model has provided simulation of the full ensemble of proximal and distal nephron segments and suggested that in response to hyperkalemia, the impact to reduce PT Na+ reabsorption was most important to rationalizing natriuresis (20). In the proximal convoluted tubule (PCT), increased cortical interstitial K+ depressed peritubular Cl− and exit, so the cell was alkalinized and luminal NHE3 activity decreased. Most recently, the kidney model was extended to represent renal cortical blood flow, both within the cortical labyrinth and medullary ray (MR) (21). This model provides predictions of both cortical and medullary interstitial solute concentrations and was first applied to examine renal ammonia partitioning between venous return and urinary excretion. In the present work, this model was used to simulate the whole kidney response to acute hyperkalemia. What the model can provide is explicit representation of interstitial K+ concentrations that modulate tubular K+ secretion, tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF) action to blunt natriuresis, and the reduction of ammoniagenesis that increases CNT and cortical CD (CCD) K+ secretion. Specifically, it will be shown that the reduction in ammoniagenesis decreases cortical ammonia concentration, which diminishes principal cell acidification, and thus enhances ENaC activity. This mechanism, by which a reduction of ammoniagenesis can increase K+ excretion, is a novel prediction of this model.

PROGRAM OF CALCULATIONS

The model used for the calculations of this work is the most recent simulation of the whole kidney (21). This model, whose development has relied on micropuncture data, is considered to represent a male rat. Several model features will be highlighted in the calculations of this paper. Specifically, there is a uniform population of superficial (SF) nephrons, which outnumber juxtamedullary (JM) nephrons by 2:1. At the single nephron level, baseline JM glomerular filtration rate (JMGFR) is about twice that for superficial nephrons [superficial glomerular filtration rate (SFGFR)], so that filtration for the two populations is comparable. A TGF relation prescribes the exact single-nephron GFR (SNGFR) as a function of that nephron’s end-cortical AHL cytosolic Cl− concentration (Eq. 23 in Ref. 22):

| (1) |

In this equation, Fv0 is a specified set point for SNGFR and ΔFv determines the fractional excursion around this point, as cytosolic Cl− varies above or below a reference concentration CI0(Cl). Fv0 is taken at 30 and 60 nL/min for SF and JM nephrons, respectively; for all nephrons, ΔFv = 1.0, whereas for SF and JM, CI0(Cl) has been set to 17 and 20 mM, respectively. In the calculations in which TGF is turned off, ΔFv is set to zero. The distinction between SF and JM nephrons extends through the DCT, and the two populations merge at the CNT inlet. In view of the fact that the model does not capture regulated NCC phosphorylation, the impact of hyperkalemia will be addressed by examining an 80% reduction in NCC density for both the SF and JM DCT. [Rengarajan et al. (8) found a 60% reduction in phosphorylated NCC in acutely K+-loaded rats, while Sorensen et al. (23) reported a more profound reduction in mice in which the hyperkalemia was greater.]

For principal cells of the CNT and CCD, ENaC activity is modulated by both luminal and cytosolic Na+ and by cytosolic pH (24), and ROMK activity is modulated by cytosolic pH (25); specifically, both channels show increased open probability with cytosolic alkalinization. Strieter et al. (26) provided representation of these regulated channels: for ENaC permeability,

| (2) |

in which pHI and CI(Na) are the cytosolic pH and Na+ concentration (in mM) and CM(Na) is the Na+ concentration in the luminal fluid; for ROMK permeability,

| (3) |

The terms P(Na) and P(K) are luminal membrane permeabilities, with dimension cm/s. They reflect channel density, unitary conductance, and channel open probability (NPo). The right hand sides do not identify those three components as distinct entities but rather provide empiric formulas for the effect of ambient Na+ and cytosolic pH. For the simulations of the aldosterone effect, both the luminal ENaC density, identified as P0(Na) in Eq. 2, along with the peritubular density of Na+-K+-ATPase are doubled from baseline. The rationale for this choice is that in the initial assignment of CCD parameters, ENaC density was chosen so that it would yield a reabsorptive Na+ flux that was within the envelope of values observed in the microperfused rat CCD, stimulated by aldosterone and possibly also antidiuretic hormone (see Table 6 in Ref. 27). A doubling of CCD Na+ flux would put flux value near the upper limit of these experimental observations. In the model, this was achieved by coordinate increases in both ENaC and Na+-K+-ATPase (27). In fashioning the CNT model, principal cell transporter densities had been taken to be fourfold greater than those of the CCD (16), and that proportion was preserved at baseline and with aldosterone stimulation.

With respect to Eq. 3 and the pH dependence of ROMK, it is acknowledged that ROMK expressed in oocytes showed a conductance pKa = 7.2 (28). The data from Wang et al. (25) that were used in formulating Eq. 3 were obtained in patches excised from the rat CCD and thus are germane to the model of this paper. Beyond that, in calculations not shown, changing the ROMK pKa to 7.2 did alter principal cell K+ transport but did not change the relative impact of ammoniagenesis perturbations of renal K+ excretion. In this model, ammoniagenesis takes place in PCTs and in proximal straight tubules (PSTs) in both the MR and outer medulla (OM). Baseline rates, Q0(Amm), are an order of magnitude greater in the PCT than in the PST, and in the PCT there is flow dependence of ammoniagenesis. The flow dependence [see Eqs. 2–5 in Weinstein (22)] specifies PCT transport parameter densities, including local ammoniagenesis, as a linear function of drag on brush-border microvilli, according to

| (4) |

In Eq. 4, T(x) is the local microvillous torque, which is proportional to drag and an estimate of the force on the underlying actin cytoskeleton; T0 is a reference torque; and TS is the sensitivity. In the calculations that follow, ammoniagenesis perturbations are performed by changing the reference rate, Q0(Amm).

The program of calculations is shown in Table 1, organized in three sections. Section A includes no transporter regulation but simply the effect of hyperkalemia, with and without TGF functioning. A1 repeats the baseline calculation from Ref. 21, in which arterial K+ = 5 mM. In A2, K+ is increased to 6.5 mM, with no other model change, so that TGF remains active. In A3, TGF is eliminated, and GFR is specified at its level determined from A1; this reveals the direct tubule effects of hyperkalemia. In section B, known regulatory responses to hyperkalemia are introduced sequentially and additively: the aldosterone effect on CNT and CCD principal cells, NCC downregulation, and halving of ammoniagenesis in all PCTs and PSTs (in both the MR and OM). In section C, the calculations of section B are repeated with TGF turned off.

Table 1.

Program of calculations

| Calculation | Blood K+ | TGF Off | PC ENaC × 2Na+-K+-ATPase × 2 | NCC × 20% | QI (Amm) × 50% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Section A | |||||

| A1 | 5.0 | ||||

| A2 | 6.5 | ||||

| A3 | 6.5 | X | |||

| Section B | |||||

| B0 = A2 | 6.5 | ||||

| B1 | 6.5 | X | |||

| B2 | 6.5 | X | X | ||

| B3 | 6.5 | X | X | X | |

| Section C | |||||

| C0 = A3 | 6.5 | X | |||

| C1 | 6.5 | X | X | ||

| C2 | 6.5 | X | X | X | |

| C3 | 6.5 | X | X | X | X |

ENaC, epithelial Na+ channel; NCC, NaCl cotransporter; PC, principal cell; QI(Amm), proximal tubule ammoniagenesis; TGF, tubuloglomerular feedback.

MODEL RESULTS

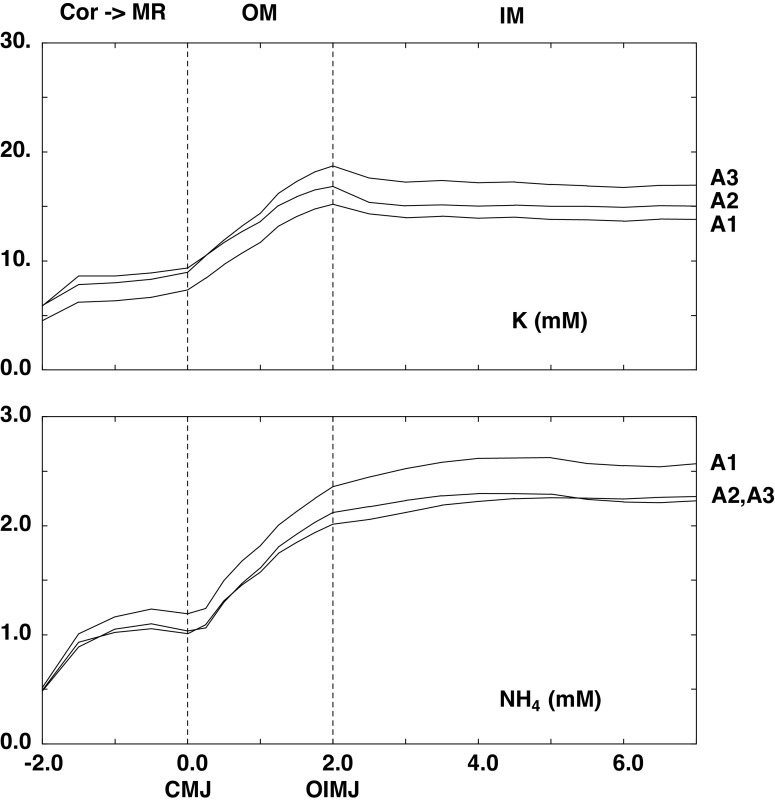

Regulation Is Absent

Table 2 shows the arterial blood composition and intrarenal blood flows, which are stipulated parameters. In Table 2, column 2 shows (in bold) the change in arterial composition used to represent hyperkalemia and also the change in the reference rate for ammoniagenesis. (In each PCT, the actual rate of ammoniagenesis is modulated by luminal fluid velocity.) When TGF is active, GFR is a model variable; column 1 in Table 2 includes its value in the baseline case (A1), and column 2 in Table 2 includes its value in hyperkalemia, when all regulatory features are active (B3). Although the model parameters are identical to those used previously (21), the 1% difference in baseline GFR reflects a computational correction in β-cell transport. Of note, cortical blood flow [renal blood flow (RBF)] and cortical interstitial hydrostatic pressures were assumed unchanged with hyperkalemia. With respect to blood flow, there appears to be no experimental guidance as to how to apportion afferent and efferent arteriolar resistance changes corresponding to TGF activation. With afferent constriction RBF is reduced and with efferent relaxation RBF increases. From purely afferent constriction, the 12% GFR reductions shown in Table 2 would be associated with a 7% decrease in RBF (unpublished calculation), which would produce minor perturbation of predicted cortical interstitial concentrations. As previously indicated (21), cortical interstitial pressures (10 mmHg) could not be computed for a capillary plexus and were assumed; cortical volume conservation was achieved by setting capillary fluid uptake equal to aggregate regional nephron fluid absorption. Computed interstitial concentrations of K+ and for each of the three conditions of unregulated transporters are shown in Fig. 1. Key values are shown in Table 3 within the cortical labyrinth, at the corticomedullary junction (CMJ) of the MR and OM, at the junction of the OM and inner medulla (IM) (OIMJ), and at the papillary tip. Whether normal or hyperkalemic, cortical K+ concentration is lower than in arterial blood, reflecting CNT K+ secretion; cortical is higher than in arterial blood due to ammoniagenesis. In each calculation, the MR concentration profiles are flat, so that the CMJ value is approximately that found throughout the ray. With reference to Tables 3 and 4 in Ref. 21, the principal sources of MR K are the PST and cortical AHL; the principal source of is the CCD, with smaller contributions from the PST and AHL. Comparison of OIMJ and CMJ concentrations demonstrates the ramp up for both K+ and within the OM, due to reabsorption by the AHL and flux across the OMCD. Within the IM, the profiles are flat, and differences between the OIMJ and papillary tip are small.

Table 2.

Blood composition and flows: baseline and hyperkalemia

| Baseline (A1) | Hyperkalemia (B3) | |

|---|---|---|

| Plasma flow, µL/min | ||

| Cortical labyrinth | 2,700.0 | 2,700.0 |

| Medullary ray | 311.0 | 311.0 |

| SAVR | 192.0 | 192.0 |

| LAVR | 37.2 | 37.2 |

| Hematocrit, % | 45 | 45 |

| Po2, mmHg | ||

| Cortical labyrinth | 65 | 65 |

| Medullary ray | 65 | 65 |

| Outer medulla | 35 | 35 |

| Inner medulla | 35 → 7 | 35 → 7 |

| Interstitial pressure, mmHg | ||

| Cortical labyrinth | 10.0 | 10.0 |

| Medullary ray | 10.0 | 10.0 |

| GFR, µL/min | ||

| Superficial | 741.0 | 652.8 |

| Juxtamedullary | 767.4 | 699.0 |

| Filtration fraction | 32% | 29% |

| Plasma concentration | ||

| Na+, mM | 144.00 | 144.00 |

| K+, mM | 5.00 | 6.50 |

| Cl−, mM | 118.40 | 119.90 |

| , mM | 25.0 | 25.0 |

| H2CO3, µM | 3.53 | 3.53 |

| CO2, mM | 1.20 | 1.20 |

| , mM | 2.10 | 2.10 |

| , mM | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Urea, mM | 5.00 | 5.00 |

| NH3, µM | 1.83 | 1.83 |

| , mM | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| HCO2−, mM | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| H2CO2, µM | 0.22 | 0.22 |

| Glucose, mM | 5.00 | 5.00 |

| Protein, g/dL | 8.00 | 8.00 |

| Ammoniagenesis, nmol/s/cm2 | ||

| SFPCT | 0.150 | 0.075 |

| SFPST | 0.015 | 0.0075 |

| JMPCT | 0.300 | 0.150 |

| JMPST | 0.030 | 0.015 |

In column 2, the bold font shows the change in arterial composition used to represent hyperkalemia and also the change in the reference rate for ammoniagenesis. GFR, glomerular filtration rate; JMPCT and JMPST, juxtamedullary proximal convoluted tubule and proximal straight tubule; LAVR, long ascending vasa recta; SAVR, short ascending vasa recta; SFPCT and SFPST, superficial proximal convoluted tubule and proximal straight tubule, respectively.

Figure 1.

Interstitial K+ and concentration profiles from the medullary ray (MR) (−2 < x < 0 mm) through the outer medulla (OM) (0 < x < 2 mm) and inner medulla (IM) (2 < x < 7 mm). The initial point at x = −2.0 indicates concentration within the cortical labyrinth. The three curves correspond to model calculations in the absence of any regulatory response: normal K+ (NK; A1) and hyperkalemia with and without active tubuloglomerular feedback (HK + TGF and HK + no TGF; A2 and A3). CMJ, corticomedullary junction; OIMJ, outer-inner medullary junction.

Table 3.

Interstitial concentrations without and with transporter regulation

| Calculation |

A1 (K+ = 5; TGF on) |

A2 (K+ = 6.5; TGF on) |

A3 (K+ = 6.5; TGF off) |

|---|---|---|---|

| K+, mM | |||

| Cortex | 4.5 | 5.9 | 5.9 |

| CMJ | 7.3 | 9.4 | 9.0 |

| OIMJ | 15.2 | 16.8 | 18.7 |

| Papilla | 13.8 | 15.0 | 16.9 |

| , mM | |||

| Cortex | 0.52 | 0.49 | 0.48 |

| CMJ | 1.19 | 1.01 | 1.03 |

| OIMJ | 2.36 | 2.01 | 2.12 |

| Papilla | 2.57 | 2.27 | 2.23 |

| CalculationTGF on |

B1 (Aldo) |

B2 (Aldo + NCC) |

B3 [Aldo + NCC + QI (Amm)] |

|---|---|---|---|

| K+, mM | |||

| Cortex | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.4 |

| CMJ | 9.7 | 9.3 | 9.1 |

| OIMJ | 22.7 | 20.8 | 22.0 |

| Papilla | 21.3 | 19.5 | 20.1 |

| , mM | |||

| Cortex | 0.47 | 0.44 | 0.25 |

| CMJ | 1.05 | 1.00 | 0.59 |

| OIMJ | 2.15 | 2.14 | 1.36 |

| Papilla | 2.12 | 2.21 | 1.39 |

| Calculation TGF off |

C1 (Aldo) |

C2 (Aldo + NCC) |

C3 [Aldo + NCC + QI (Amm)] |

|---|---|---|---|

| K+, mM | |||

| Cortex | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.4 |

| CMJ | 9.5 | 9.2 | 9.0 |

| OIMJ | 17.7 | 17.9 | 19.4 |

| Papilla | 16.4 | 16.1 | 17.1 |

| , mM | |||

| Cortex | 0.50 | 0.46 | 0.26 |

| CMJ | 1.23 | 0.95 | 0.56 |

| OIMJ | 2.45 | 1.98 | 1.26 |

| Papilla | 2.54 | 2.20 | 1.34 |

Aldo, aldosterone; CMJ, corticomedullary junction; NCC, NaCl cotransporter; OIMJ, outer-inner medullary junction; QI(Amm), proximal tubule ammoniagenesis; TGF, tubuloglomeruler feedback.

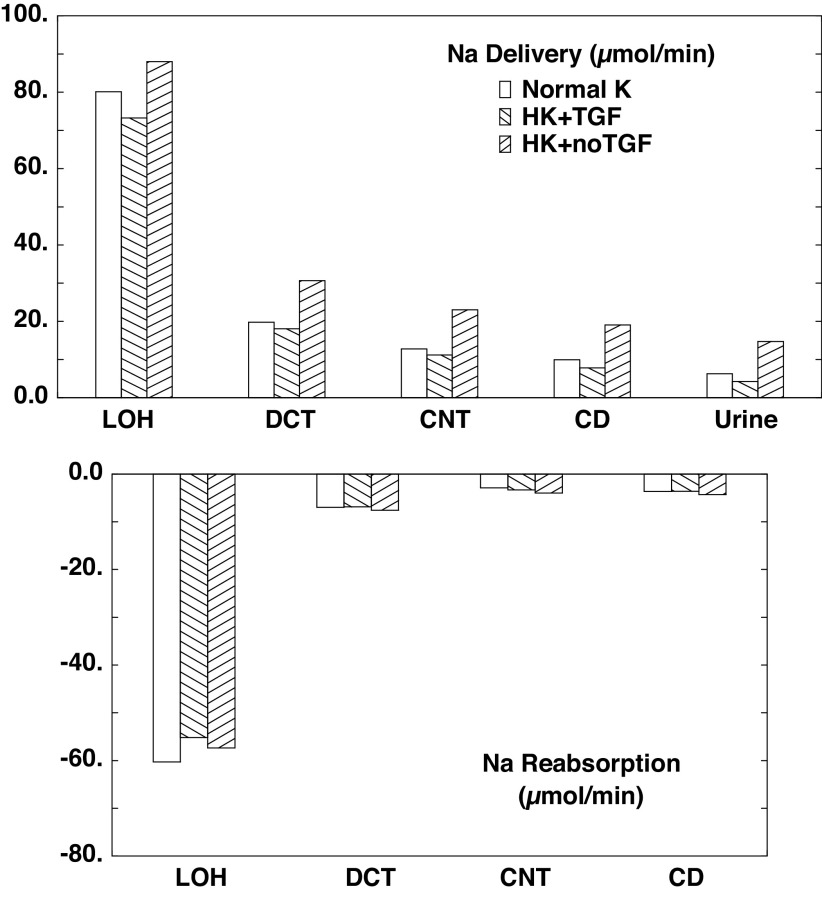

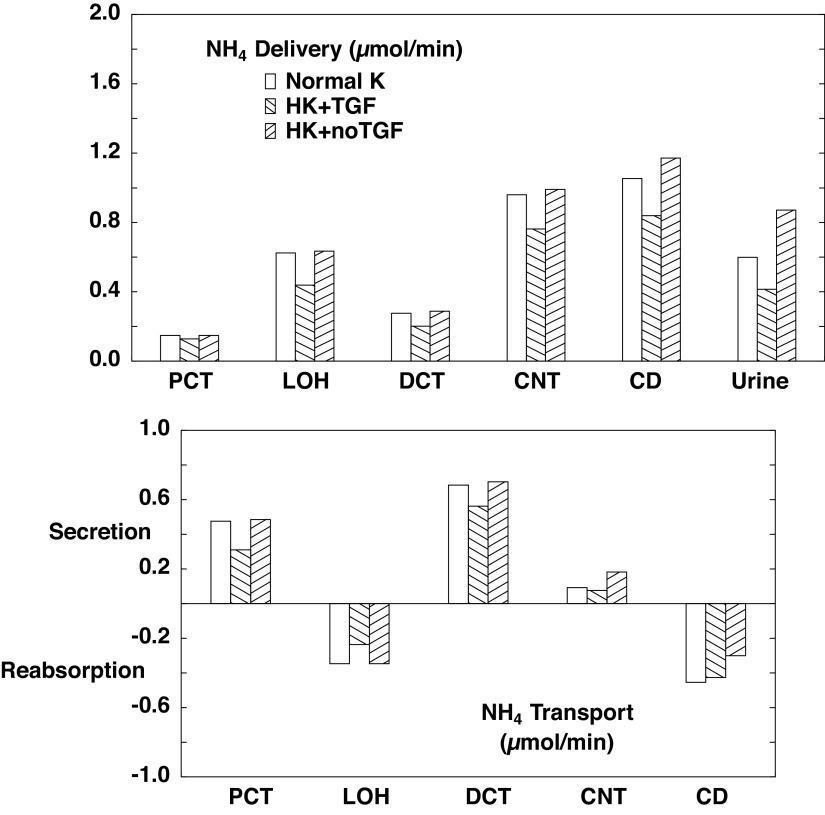

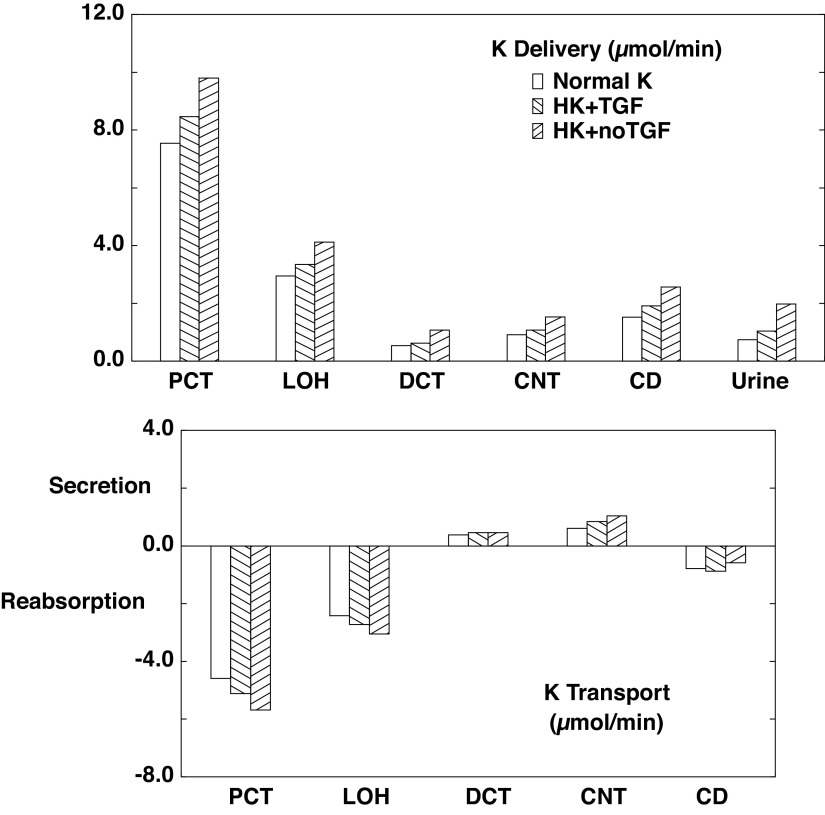

Table 4 and associated Figs. 2–4 show flows and fluxes of Na+, K+, , and volume in five nephron regions. This is a compression of the information provided in Tables 3 and 4 of Ref. 21, which reported out flows and fluxes of 19 nephron segments. Specifically, superficial proximal convoluted tubule (SFPCT) and juxtamedullary proximal convoluted tubule (JMPCT) entries are combined as the PCT, all tubules from the PST through the cortical AHL are combined into the loop of Henle (LOH), the DCT sums both SF and JM segments, and the CD includes the CCD, OMCD, and IMCD; by virtue of its importance to this work, the CNT is reported individually. Figures 2–4 show regional solute entry (delivery) at the top; the bottom shows reabsorption as a negative deflection and secretion as positive. For each graph, the first (open) bars correspond to normal K+ (A1), the second (backslash) bars correspond to hyperkalemia with active TGF (A2), and the third (forward slash) bars are hyperkalemia with no change in GFR (A3). With respect to Na+ (Fig. 2), comparison of A1 and A3 shows that hyperkalemia reduces PCT reabsorption from 63.1% to 59.5% of filtered load. In downstream segments, the increase in Na+ delivery acts to enhance Na+ reabsorption, while hyperkalemia may reduce it. In the LOH, the K+ effect dominates, so that Na+ reabsorption decreases from 27.8% to 26.4% of filtered load. In all, CNT Na+ delivery increases from 5.9% to 10.6% of filtered load on the basis of hyperkalemia alone; renal Na+ excretion more than doubles from 2.9% to 6.8% of filtrate. When TGF is active (A2), the model shows a 14% reduction in GFR, which attenuates to a 9% reduction in LOH Na+ delivery, and this difference attenuates further, so that there is comparable Na+ delivery to the CNT, and urinary Na+ excretion is little different from when K+ is normal. The impact of hyperkalemia on renal K+ handling is modest (Fig. 3). When Na+ delivery to the CNT is similar (comparing A1 with A2), hyperkalemia increases CNT K+ secretion from 0.61 to 0.84 µmol/min. With the near doubling of CNT Na+ delivery that comes with silencing TGF (A1 vs. A3), CNT K+ secretion goes up to 1.04 µmol/min. In this model, ammonia secretion occurs in the cortex, primarily in the PCT and DCT, with reabsorption in the LOH and CD (Fig. 4). When TGF is on (A2), lower PCT flow blunts ammoniagenesis (from 2.9 to 2.5 µmol/min) as well as flux through NHE3, to reduce PCT secretion. In the DCT, higher peritubular K+ reduces uptake by Na+-K+-ATPase and thus reduces secretion there. The net effect of hyperkalemia is a reduction in urinary . Absent TGF, PT secretion is restored to baseline (A1). With increased Na+ delivery to the distal nephron, the DCT and CNT increase Na+ reabsorption driving peritubular Na+/ exchange and thus luminal secretion. The increase in fluid delivery to the CD blunts reabsorption there, so that overall excretion is augmented.

Table 4.

Whole kidney flows and fluxes in the absence of transporter regulation

| Case A1 | PCT | LOH | DCT | CNT | CD | Urine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delivery | ||||||

| Na+, µmol/min | 217.2 | 80.1 | 19.8 | 12.8 | 9.9 | 6.3 |

| K+ | 7.54 | 2.95 | 0.53 | 0.91 | 1.52 | 0.73 |

| 0.15 | 0.62 | 0.28 | 0.96 | 1.05 | 0.60 | |

| Fv, µL/min | 1,508 | 565 | 236 | 214 | 117 | 39 |

| Relative to filtered load | ||||||

| Na+ | 100.0% | 36.9% | 9.1% | 5.9% | 4.6% | 2.9% |

| K+ | 100.0% | 39.1% | 7.0% | 12.1% | 20.1% | 9.7% |

| 100.0% | 421.2% | 186.6% | 648.5% | 711.4% | 404.8% | |

| F v | 100.0% | 37.4% | 15.7% | 14.2% | 7.7% | 2.6% |

| Reabsorption | Total | |||||

| Na+, µmol/min | 137.1 | 60.3 | 7.0 | 2.9 | 3.6 | 210.9 |

| K+ | 4.59 | 2.42 | −0.38 | −0.61 | 0.78 | 6.81 |

| −0.48 | 0.35 | −0.68 | −0.09 | 0.45 | −0.45 | |

| Jv, µL/min | 944 | 328 | 22 | 97 | 78 | 1470 |

| Relative to filtered load | ||||||

| Na+ | 63.1% | 27.8% | 3.2% | 1.3% | 1.7% | 97.1% |

| K+ | 60.9% | 32.1% | −5.1% | −8.0% | 10.4% | 90.3% |

| −321.2% | 234.6% | −461.8% | −62.9% | 306.6% | −304.8% | |

| J v | 62.6% | 21.8% | 1.5% | 6.4% | 5.2% | 97.4% |

| Case A2 | PCT | LOH | DCT | CNT | CD | Urine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delivery | ||||||

| Na+, µmol/min | 187.5 | 73.2 | 18.1 | 11.2 | 7.9 | 4.3 |

| K+ | 8.46 | 3.34 | 0.62 | 1.07 | 1.92 | 1.04 |

| 0.13 | 0.44 | 0.20 | 0.76 | 0.84 | 0.41 | |

| Fv, µL/min | 1,302 | 514 | 215 | 192 | 97 | 29 |

| Relative to filtered load | ||||||

| Na+ | 100.0% | 39.1% | 9.6% | 6.0% | 4.2% | 2.3% |

| K+ | 100.0% | 39.5% | 7.3% | 12.7% | 22.6% | 12.3% |

| 100.0% | 342.8% | 157.2% | 596.6% | 656.4% | 323.4% | |

| F v | 100.0% | 39.4% | 16.5% | 14.8% | 7.4% | 2.2% |

| Reabsorption | Total | |||||

| Na+, µmol/min | 114.3 | 55.2 | 6.9 | 3.3 | 3.6 | 183.2 |

| K+ | 5.12 | 2.73 | −0.45 | −0.84 | 0.88 | 7.43 |

| −0.31 | 0.24 | −0.56 | −0.08 | 0.43 | −0.29 | |

| Jv, µL/min | 789 | 298 | 23 | 96 | 67 | 1273 |

| Relative to filtered load | ||||||

| Na+ | 60.9% | 29.4% | 3.7% | 1.8% | 1.9% | 97.7% |

| K+ | 60.5% | 32.2% | −5.4% | −10.0% | 10.4% | 87.7% |

| −242.8% | 185.6% | −439.3% | −59.8% | 332.9% | −223.4% | |

| J v | 60.6% | 22.9% | 1.8% | 7.4% | 5.2% | 97.8% |

| Case A3 | PCT | LOH | DCT | CNT | CD | Urine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delivery | ||||||

| Na+, µmol/min | 217.2 | 88.0 | 30.6 | 23.0 | 19.1 | 14.7 |

| K+ | 9.80 | 4.12 | 1.07 | 1.53 | 2.57 | 1.97 |

| 0.15 | 0.63 | 0.29 | 0.99 | 1.17 | 0.87 | |

| Fv, µL/min | 1508 | 616 | 295 | 278 | 200 | 88 |

| Relative to filtered load | ||||||

| Na+ | 100.0% | 40.5% | 14.1% | 10.6% | 8.8% | 6.8% |

| K+ | 100.0% | 42.0% | 10.9% | 15.6% | 26.2% | 20.1% |

| 100.0% | 428.3% | 194.2% | 669.0% | 791.8% | 588.8% | |

| F v | 100.0% | 40.8% | 19.5% | 18.4% | 13.3% | 5.8% |

| Reabsorption | Total | |||||

| Na+, µmol/min | 129.2 | 57.4 | 7.6 | 4.0 | 4.3 | 202.5 |

| K+ | 5.68 | 3.05 | −0.46 | −1.04 | 0.59 | 7.83 |

| −0.49 | 0.35 | −0.70 | −0.18 | 0.30 | −0.72 | |

| Jv, µL/min | 893 | 321 | 16 | 78 | 112 | 1420 |

| Relative to filtered load | ||||||

| Na+ | 59.5% | 26.4% | 3.5% | 1.8% | 2.0% | 93.2% |

| K+ | 58.0% | 31.1% | −4.7% | −10.6% | 6.0% | 79.9% |

| −328.3% | 234.1% | −474.8% | −122.8% | 203.0% | −488.8% | |

| J v | 59.2% | 21.3% | 1.1% | 5.2% | 7.4% | 94.2% |

CD, collecting duct from the cortical collecting duct through the inner medullary collecting duct; CNT, connecting tubule; DCT, distal convoluted tubule; Fv, axial volume flow; Jv, volume reabsorption; LOH, loop of Henle (all tubules from the proximal straight tubule through the cortical ascending Henle’s loop); PCT, all proximal convoluted tubules.

Figure 2.

Segmental accounting of whole kidney Na+ flows (delivery) and fluxes (transport) in the absence of a regulatory response. Negative transport values correspond to reabsorptive fluxes. The loop of Henle (LOH) comprises all tubule segments from the proximal straight tubule through the cortical ascending Henle’s loop, and the collecting duct (CD) includes cortical and medullary CDs. Open bars denote normal K+ (NK; A1); backslash bars indicate hyperkalemia with active tubuloglomerular feedback (HK + TGF; A2); and forward slash bars shows results when glomerular filtration rate is at its value for normal K+ (HK + no TGF; A3). Proximal delivery and reabsorption are available in Table 4 but are not depicted, to appreciate distal transport. CNT, connecting tubule; DCT, distal convoluted tubule.

Figure 4.

Segmental accounting of whole kidney flows and fluxes in the absence of a regulatory response. Negative or positive transport values correspond to reabsorptive or secretory fluxes. As in Fig. 2. open bars denote normal K+ (NK), backslash bars indicate hyperkalemia with active tubuloglomerular feedback (HK + TGF; A2); and forward slash bars shows results when glomerular filtration rate is at its value for normal K+ (HK + no TGF; A3). The values shown are those in Table 4. secretion is most prominent in the proximal convoluted tubule (PCT) and distal convoluted tubule (DCT). CD, collecting duct; CNT, connecting tubule; LOH, loop of Henle.

Figure 3.

Segmental accounting of whole kidney K+ flows and fluxes in the absence of a regulatory response. Negative or positive transport values correspond to reabsorptive or secretory fluxes. As in Fig. 2. open bars denote normal K+ (NK), backslash bars indicate hyperkalemia with active tubuloglomerular feedback (HK + TGF; A2); and forward slash bars shows results when glomerular filtration rate is at its value for normal K+ (HK + no TGF; A3). The values shown are those in Table 4. Hyperkalemia per se increases filtered K+ and its reabsorption within the proximal convoluted tubule (PCT) and loop of Henle (LOH). Compared with normokalemia, overall K+ excretion increases 50% with hyperkalemia, and this is nearly doubled by higher flow. CD, collecting duct; CNT, connecting tubule; DCT, distal convoluted tubule.

In view of the impact of TGF in modulating solute excretion, it is important to understand the mechanism by which the model translates increased arterial K+ into a GFR reduction. That is shown in Table 5, which shows end-cortical AHL (macula densa) lumen, cell, and interstitial conditions for SF nephrons, when blood K+ = 5.0 (A1) and when K+ = 6.5 with TGF on (A2). With the increase in blood K+, MR interstitial K+ increases from 6.2 to 7.8 mM. The impact on the cell is peritubular depolarization (−87.2 to −81.1 mV) and an increase in cytosolic Cl− (13.4 to 19.1 mM). By virtue of peritubular Cl−/ exchange, cytosolic increases from 13.4 to 19.5 mM, and the cell alkalinizes from pH = 6.76 to 6.93. It is the increase in cell Cl− that is the TGF signal (Eq. 1). Parenthetically, the higher cell Cl− blunts luminal Na+ entry via Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter isoform 2 (NKCC2) from 87.1 to 83.1 pmol/min/mm, and the alkalinization reduces Na+ entry via NHE3 from 52.0 to 43.0 pmol/min/mm. With these reductions in Na+ uptake, cytosolic Na+ decreases from 13.0 to 11.0 mM. This impact of peritubular K+ on cytosolic composition and on luminal membrane transport had been examined in the initial presentation of the AHL model (see Fig. 5 in Ref. 17).

Table 5.

End superficial ascending Henle’s loop (macula densa) solute concentrations: baseline (A1) and hyperkalemia (A2)

| Case A1 | Lumen | Cell | Interstitium |

|---|---|---|---|

| PD, mV | 15.5 | −87.2 | |

| Concentrations, mM | |||

| Na+ | 73.5 | 13.0 | 186.5 |

| K+ | 2.4 | 166.5 | 6.2 |

| Cl− | 64.6 | 16.5 | 160.7 |

| 5.9 | 13.4 | 27.8 | |

| CO2 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.9 |

| 1.5 | 6.3 | 1.7 | |

| 3.7 | 6.8 | 0.9 | |

| Urea | 9.7 | 6.7 | 6.3 |

| 1.2 | 3.6 | 1.0 | |

| Imp | 125.3 | ||

| pH | 6.41 | 6.76 | 7.08 |

| Case A2 | Lumen | Cell | Interstitium |

|---|---|---|---|

| PD, mV | 16.4 | −81.1 | |

| Concentrations, mM | |||

| Na+ | 73.9 | 11.0 | 184.2 |

| K+ | 3.2 | 171.6 | 7.8 |

| Cl− | 62.3 | 19.1 | 158.4 |

| 8.9 | 19.5 | 29.3 | |

| CO2 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.9 |

| 1.9 | 7.8 | 1.8 | |

| 3.0 | 5.8 | 0.9 | |

| Urea | 9.5 | 6.6 | 6.2 |

| 1.0 | 2.1 | 0.9 | |

| Imp | 113.1 | ||

| pH | 6.59 | 6.93 | 7.10 |

Imp, cytosolic impermeant.

Regulated Transport: TGF Is On

In this section, the impact of transport regulation is examined with TGF intact, so that the baseline for comparison is A2. Aldosterone regulation and the reduction in NCC activity are established responses to hyperkalemia; decreased ammoniagenesis in hyperkalemia is also secure but has not yet been identified as a factor that enhances K+ excretion. Table 3 shows interstitial concentrations determined by the three calculations of this section. Aldosterone by itself (B1) reduces cortical interstitial K+ concentration (from 5.9 to 5.5 mM), consistent with increased CNT uptake, and increases medullary interstitial K+ (from 16.8 to 20.8 at the OIMJ), consistent with increased CD delivery. In this case, there is little change in profiles. Augmenting the aldosterone effect by reducing NCC transport (B2) produces no change in cortical K+ and only a small reduction in medullary K+, consistent with restoration of urinary flow. When ammoniagenesis is also reduced by 50% (B3), cortical and medullary interstitial concentrations fall by ∼40%; there is a modest increase in medullary interstitial K+.

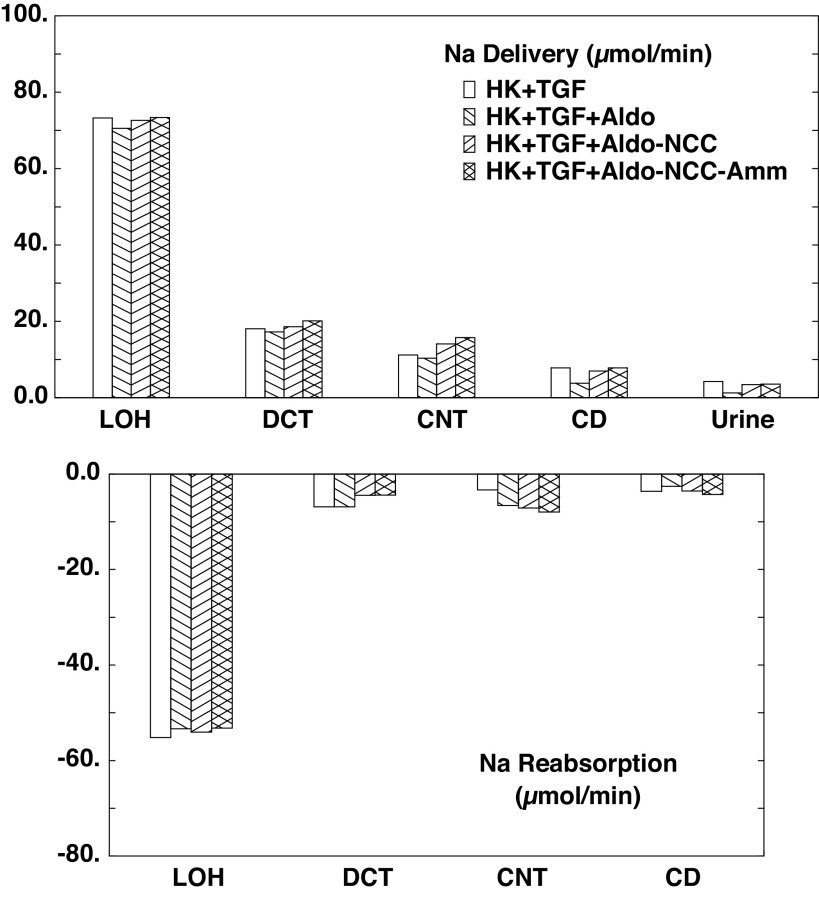

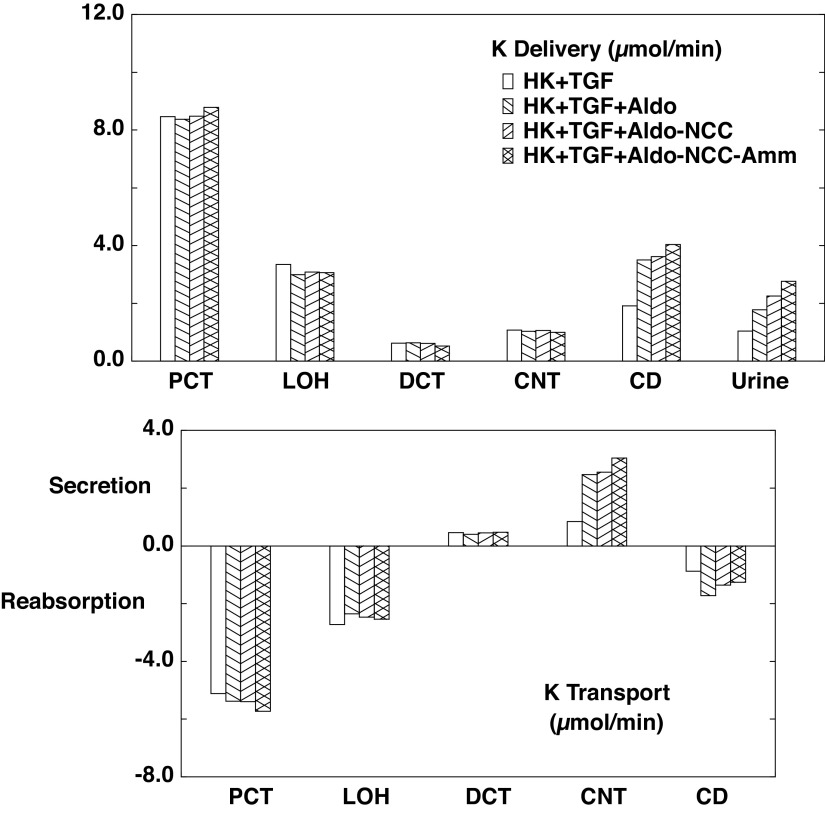

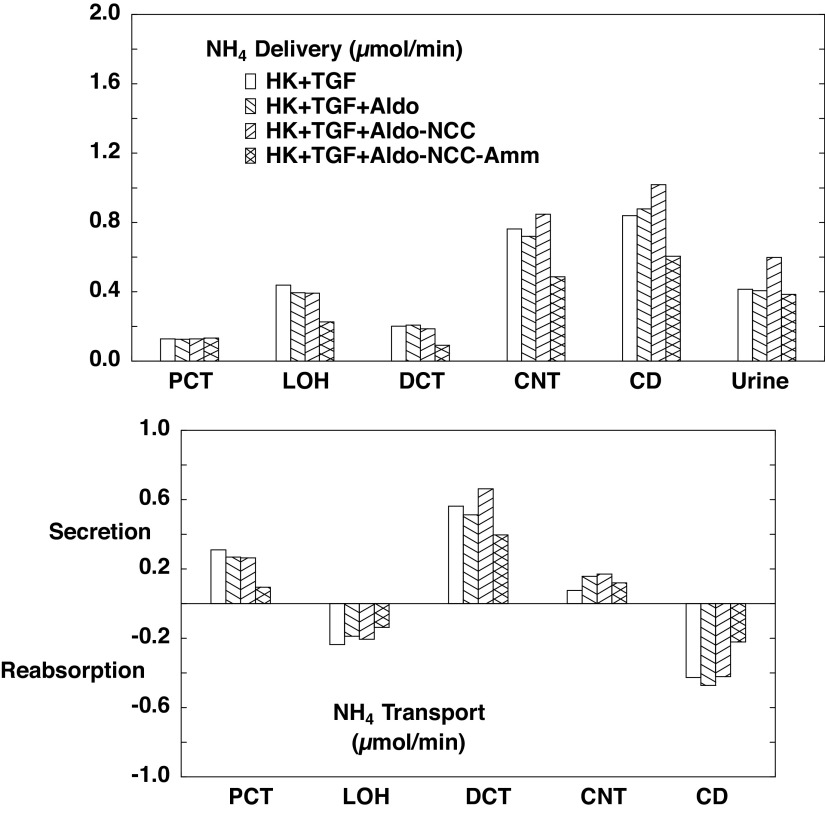

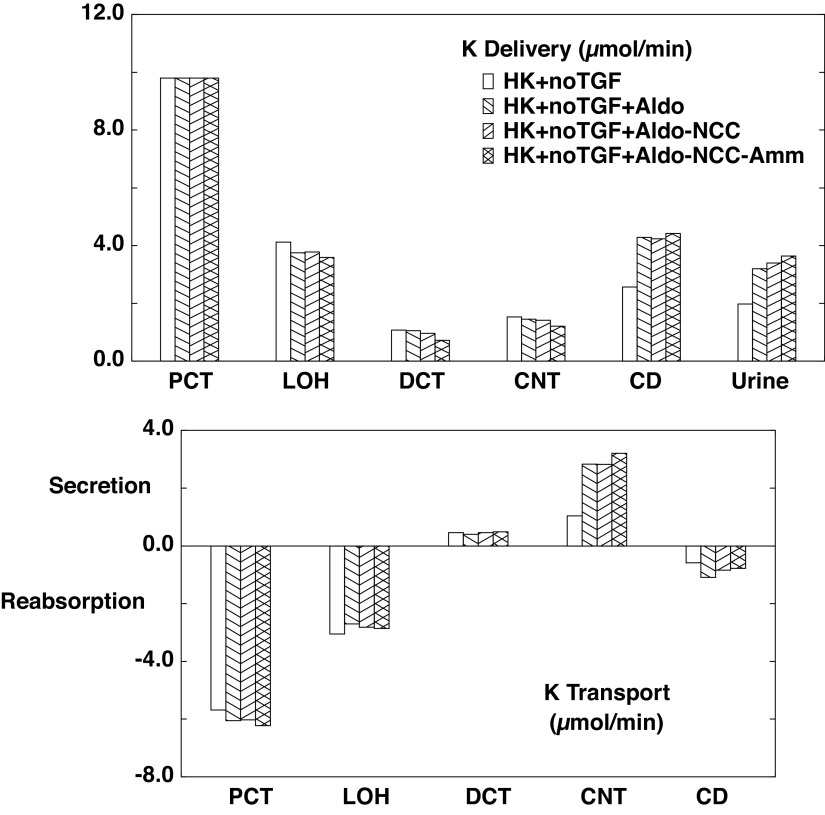

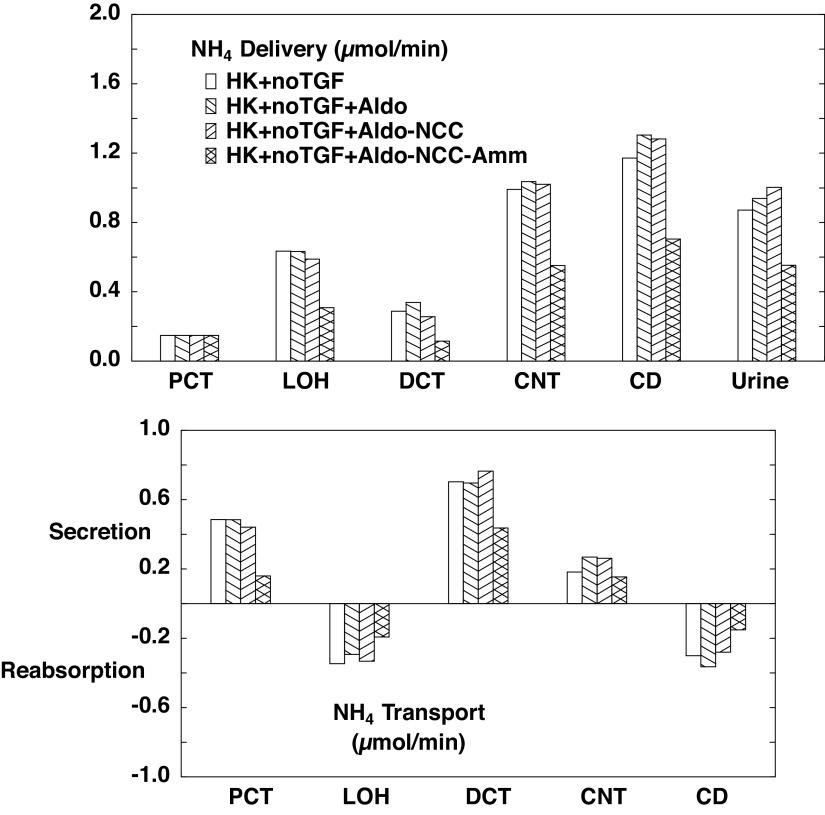

The flows and fluxes associated with these simulations are shown in Table 6 and Figs. 5–7. Figures 5–7 show solute delivery at the top and solute transport at the bottom. For each region, there are four bars: the left-most (open) bars correspond to unregulated hyperkalemia (A2), the second (backslash) bars are the aldosterone effect (B1), the third (forward slash) bars include NCC inhibition (B2), and the right-most bars (cross-hatched) add reduction of ammoniagenesis (B3). With respect to Na+ transport (Fig. 5), aldosterone increases CNT Na+ reabsorption from 3.3 µmol/min or 1.8% of filtered Na+ (A2 in Table 4) to 6.5 µmol/min or 3.5% of filtered Na+ (B1 in Table 6). This reduces Na+ delivery to CD and ultimately lowers urinary Na+, from 2.9% of filtered Na+ to 0.7%. With the 80% reduction in NCC, DCT Na+ reabsorption falls from 6.9 to 4.5 µmol/min (B2) and thus restores downstream Na+ delivery so that excreted Na+ is 1.8% of filtered load. The reduction in ammoniagenesis has a negligible impact on Na+ transport. With respect to K+ transport, the impact of all three regulatory processes is substantial (Fig. 6). As seen in the final urine, aldosterone, NCC inhibition, and ammonia reduction all increase urine K+ in a step-wise fashion, with nearly equal contributions from each. When all three are operative, urinary K+ excretion is 2.77 µmol/min (B3) compared with 1.04 µmol/min in the absence of any regulation (A2). In the case of aldosterone alone (B1), the increment in urine K+ derives from the increment in CNT K+ secretion, up to 2.47 from 0.84 µmol/min. With NCC reduction, the increment in urine K+ derives from diminished CD K+ reabsorption, and this is due to the increase in CD fluid flow that comes with restoration of urine Na+ flow: 109 µL/min (B2) compared with 81 µL/min (B1). At higher flows within the CD, there is less concentration of luminal solutes and thus a reduction in the transepithelial K+ concentration difference driving reabsorption (29). The reduction in ammoniagenesis (B3) augments K+ excretion by virtue of its impact on CNT K+ secretion, and the model reveals the mechanism. Table 7 shows the impact of reduced ammoniagenesis on CNT transport, when the aldosterone effect and reduced NCC are already in place, comparing B2 with B3. With reduced ammoniagenesis, cortical interstitial decreases from 0.4 to 0.2 mM, so that peritubular uptake via Na+-K+-ATPase is reduced. Peritubular entry acidifies the cell, so that reducing this flux produces cytosolic alkalinization from pH = 7.24 to 7.29. The pH effect on ENaC (Eq. 2) increases its Na+ conductance so as to yield a 12% increase in Na+ entry and luminal hyperpolarization by 2 mV. The pH effect on ROMK (Eq. 3) provides for a 32% increase in secretory K+ flux.

Table 6.

Whole kidney flows and fluxes in hyperkalemia with regulated transport and tubuloglomerular feedback active

| Case B1 | PCT | LOH | DCT | CNT | CD | Urine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delivery | ||||||

| Na+, µmol/min | 185.4 | 70.5 | 17.2 | 10.4 | 3.8 | 1.2 |

| K+ | 8.37 | 2.99 | 0.63 | 1.03 | 3.50 | 1.78 |

| 0.13 | 0.40 | 0.21 | 0.72 | 0.88 | 0.41 | |

| Fv, µL/min | 1,288 | 492 | 206 | 183 | 81 | 18 |

| Relative to filtered load | ||||||

| Na+ | 100.0% | 38.1% | 9.3% | 5.6% | 2.1% | 0.7% |

| K+ | 100.0% | 35.7% | 7.6% | 12.3% | 41.8% | 21.2% |

| 100.0% | 312.8% | 163.6% | 569.4% | 694.5% | 321.0% | |

| F v | 100.0% | 38.2% | 16.0% | 14.2% | 6.3% | 1.4% |

| Reabsorption | Total | |||||

| Na+, µmol/min | 114.9 | 53.3 | 6.9 | 6.5 | 2.6 | 184.2 |

| K+ | 5.38 | 2.36 | −0.40 | −2.47 | 1.72 | 6.59 |

| −0.27 | 0.19 | −0.51 | −0.16 | 0.47 | −0.28 | |

| Jv, µL/min | 796 | 286 | 23 | 102 | 62 | 1,269 |

| Relative to filtered load | ||||||

| Na+ | 62.0% | 28.8% | 3.7% | 3.5% | 1.4% | 99.3% |

| K+ | 64.3% | 28.2% | −4.8% | −29.5% | 20.6% | 78.8% |

| −212.8% | 149.2% | −405.8% | −125.1% | 373.5% | −221.0% | |

| J v | 61.8% | 22.2% | 1.8% | 7.9% | 4.8% | 98.6% |

| Case B2 | PCT | LOH | DCT | CNT | CD | Urine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delivery | ||||||

| Na+, µmol/min | 187.8 | 72.6 | 18.6 | 14.1 | 7.0 | 3.4 |

| K+ | 8.48 | 3.08 | 0.61 | 1.06 | 3.61 | 2.25 |

| 0.13 | 0.39 | 0.19 | 0.85 | 1.02 | 0.60 | |

| Fv, µL/min | 1,304 | 506 | 217 | 196 | 109 | 32 |

| Relative to filtered load | ||||||

| Na+ | 100.0% | 38.7% | 9.9% | 7.5% | 3.7% | 1.8% |

| K+ | 100.0% | 36.4% | 7.2% | 12.5% | 42.6% | 26.5% |

| 100.0% | 306.1% | 145.2% | 662.7% | 795.4% | 466.7% | |

| Fv | 100.0% | 38.8% | 16.6% | 15.1% | 8.3% | 2.5% |

| Reabsorption | Total | |||||

| Na+, µmol/min | 115.2 | 54.1 | 4.5 | 7.1 | 3.6 | 184.4 |

| K+ | 5.40 | 2.47 | −0.45 | −2.55 | 1.36 | 6.23 |

| −0.26 | 0.21 | −0.66 | −0.17 | 0.42 | −0.47 | |

| Jv, µL/min | 798 | 290 | 20 | 88 | 77 | 1,272 |

| Relative to filtered load | ||||||

| Na+ | 61.3% | 28.8% | 2.4% | 3.8% | 1.9% | 98.2% |

| K+ | 63.7% | 29.1% | −5.3% | −30.1% | 16.1% | 73.5% |

| −206.1% | 161.0% | −517.7% | −132.7% | 328.7% | −366.7% | |

| J v | 61.2% | 22.2% | 1.5% | 6.7% | 5.9% | 97.5% |

| Case B3 | PCT | LOH | DCT | CNT | CD | Urine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delivery | ||||||

| Na+, µmol/min | 194.7 | 73.4 | 20.2 | 15.8 | 7.8 | 3.6 |

| K+ | 8.79 | 3.06 | 0.52 | 0.99 | 4.04 | 2.77 |

| 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.49 | 0.61 | 0.38 | |

| Fv, µL/min | 1,352 | 510 | 224 | 205 | 118 | 35 |

| Relative to filtered load | ||||||

| Na+ | 100.0% | 37.7% | 10.4% | 8.1% | 4.0% | 1.8% |

| K+ | 100.0% | 34.8% | 5.9% | 11.3% | 45.9% | 31.5% |

| 100.0% | 171.3% | 68.4% | 367.0% | 456.3% | 289.9% | |

| F v | 100.0% | 37.8% | 16.6% | 15.1% | 8.7% | 2.6% |

| Reabsorption | Total | |||||

| Na+, µmol/min | 121.3 | 53.2 | 4.4 | 7.9 | 4.2 | 191.1 |

| K+ | 5.73 | 2.54 | −0.48 | −3.04 | 1.27 | 6.02 |

| −0.09 | 0.14 | −0.40 | −0.12 | 0.22 | −0.25 | |

| Jv, µL/min | 841 | 287 | 19 | 87 | 83 | 1,317 |

| Relative to filtered load | ||||||

| Na+ | 62.3% | 27.3% | 2.3% | 4.1% | 2.2% | 98.2% |

| K+ | 65.2% | 29.0% | −5.4% | −34.6% | 14.4% | 68.5% |

| −71.3% | 102.9% | −298.6% | −89.3% | 166.4% | −189.9% | |

| J v | 62.2% | 21.2% | 1.4% | 6.4% | 6.1% | 97.4% |

CD, collecting duct from the cortical collecting duct through the inner medullary collecting duct; CNT, connecting tubule; DCT, distal convoluted tubule; Fv, axial volume flow; Jv, volume reabsorption; LOH, loop of Henle (all tubules from the proximal straight tubule through the cortical ascending Henle’s loop); PCT, all proximal convoluted tubules.

Figure 5.

Segmental accounting of whole kidney Na+ flows (delivery) and fluxes (transport), in hyperkalemia, with tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF) active. Negative transport values correspond to reabsorptive fluxes. The bars correspond to incremental regulatory responses: open bars denote unregulated hyperkalemia (HK + TGF; A2); backslash bars indicate aldosterone (Aldo) action, a doubling of the density of the epithelial Na+ channel and Na+-K+-ATPase in principal cells (HK + TGF + Aldo; B1); forward slash bars adds an 80% reduction in NaCl cotransporter (NCC) density (HK + TGF + Aldo-NCC; B2); and cross-hatched bars add a halving of ammoniagenesis (HK + TGF + Aldo-NCC-Amm; B3). Proximal delivery and reabsorption are available in Table 6 but are not depicted. CD, collecting duct; CNT, connecting tubule; DCT, distal convoluted tubule; LOH, loop of Henle.

Figure 6.

Segmental accounting of whole kidney K+ flows (delivery) and fluxes (transport), in hyperkalemia, with tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF) active. Negative or positive transport values correspond to reabsorptive or secretory fluxes. As in Fig. 5, open bars denote unregulated hyperkalemia (HK + TGF; A2); backslash bars indicate aldosterone (Aldo) action, a doubling of the density of the epithelial Na+ channel and Na+-K+-ATPase in principal cells (HK + TGF + Aldo; B1); forward slash bars adds an 80% reduction in NaCl cotransporter (NCC) density (HK + TGF + Aldo-NCC; B2); and cross-hatched bars add a halving of ammoniagenesis (HK + TGF + Aldo-NCC-Amm; B3). The values shown are those in Table 6. With each additional regulatory response, there is a step up in K+ excretion. CD, collecting duct; CNT, connecting tubule; DCT, distal convoluted tubule; LOH, loop of Henle; PCT, proximal convoluted tubule.

Table 7.

End connecting tubule solute concentrations and principal cell luminal fluxes: combined aldosterone plus reduced NaCl cotransporter (B2) and with reduced ammoniagenesis (B3)

| Case B2 | Lumen | Cell | Interstitium |

|---|---|---|---|

| PD, mV | −46.8 | −72.4 | |

| Concentrations, mM | |||

| Na+ | 64.3 | 12.6 | 143.0 |

| K+ | 33.2 | 150.3 | 5.5 |

| Cl− | 91.5 | 18.8 | 117.4 |

| 7.0 | 28.8 | 27.1 | |

| CO2 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| 0.5 | 22.7 | 1.9 | |

| 7.4 | 8.2 | 0.6 | |

| Urea | 21.0 | 6.7 | 4.7 |

| 9.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 | |

| Imp | 16.5 | ||

| pH | 5.67 | 7.24 | 7.29 |

| PC fluxes, nmol/s/cm2 | |||

| ENaC | 7.93 | ||

| ROMK | −1.63 | ||

| Case B3 | Lumen | Cell | Interstitium |

|---|---|---|---|

| PD, mV | −48.9 | −72.4 | |

| Concentrations, mM | |||

| Na+ | 66.4 | 14.3 | 143.3 |

| K+ | 34.3 | 148.3 | 5.4 |

| Cl− | 92.3 | 19.4 | 117.5 |

| 5.8 | 33.6 | 27.0 | |

| CO2 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.8 |

| 0.4 | 21.2 | 1.9 | |

| 7.0 | 6.8 | 0.6 | |

| Urea | 19.8 | 6.6 | 4.6 |

| 5.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| Imp | 13.5 | ||

| pH | 5.56 | 7.29 | 7.27 |

| PC fluxes, nmol/s/cm2 | |||

| ENaC | 8.89 | ||

| ROMK | −2.15 | ||

ENaC, epithelial Na+ channel; ROMK, renal outer medullary K+ channel; Imp, cytosolic impermeant.

Ammonia flows and fluxes are shown in Fig. 7. As expected, reducing ammoniagenesis to 1.3 µmol/min (B3) decreases ammonia secretion in both the PCT and DCT, consistent with the decrease in cortical interstitial concentration. There is also reduced CD reabsorption, which derives from the reduced delivery. What is perhaps less intuitive is that with NCC inhibition (B2), there is enhanced DCT secretion, and this propagates to an increase in excretion. This is due to enhanced secretion via luminal membrane Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 2 (NHE2), and again the model provides insight into the mechanism. Table 8 shows the end-DCT in SF nephrons when only the aldosterone effect is operative (B1) and when the reduction in NCC density is added (B2). Reduced NCC activity lowers cytosolic Na+ from 10.4 to 8.1 mM and cytosolic Cl− from 18.4 to 12.8 mM. With the 80% reduction in NCC density, the corresponding reduction in Na+ flux via NCC is only 57%, due to the decrease in cytosolic Na+ and Cl− (and the reciprocal increase in electrochemical potential difference for NaCl across the luminal membrane). The reduction in cell Na+, however, also increases the driving force across luminal membrane NHE2, producing a near doubling of its Na+ reabsorption. Most of this increase in NHE2 Na+ flux derives from an increase in Na+/ exchange, and this is manifest as a step up in DCT secretion. When NCC reduction is combined with reduced ammoniagenesis (B3), the net effect is that excretion is little changed from baseline. With respect to overall acid-base balance, net acid excretion is 0.88 µmol/min with unregulated hyperkalemia (A2), 1.00 µmol/min with aldosterone (B1), 1.18 µmol/min with NCC inhibition (B2), and 0.94 µmol/min when reduced ammoniagenesis is superimposed (B3). In short, these last two regulatory features (NCC inhibition and reduced ammoniagenesis) combine to increase K+ excretion while avoiding an acid-base disturbance.

Figure 7.

Segmental accounting of whole kidney flows (delivery) and fluxes (transport), in hyperkalemia, with tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF) active. Negative or positive transport values correspond to reabsorptive or secretory fluxes. As in Fig. 5, open bars denote unregulated hyperkalemia (HK + TGF; A2); backslash bars indicate aldosterone (Aldo) action, a doubling of the density of the epithelial Na+ channel and Na+-K+-ATPase in principal cells (HK + TGF + Aldo; B1); forward slash bars adds an 80% reduction in NaCl cotransporter (NCC) density (HK + TGF + Aldo-NCC; B2); and cross-hatched bars add a halving of ammoniagenesis (HK + TGF + Aldo-NCC-Amm; B3). The values shown are those in Table 6. Halving of ammoniagenesis is evident in the reduced secretion in the proximal convoluted tubule (PCT) and distal convoluted tubule (DCT), and urinary excretion has normalized (comparing A1). CD, collecting duct; CNT, connecting tubule; LOH, loop of Henle.

Table 8.

End superficial distal convoluted tubule solute concentrations and cotransporter fluxes: aldosterone (B1) and combined aldosterone plus reduced NCC (B2)

| Case B1 | Lumen | Cell | Interstitium |

|---|---|---|---|

| PD, mV | −8.7 | −89.2 | |

| Concentrations, mM | |||

| Na+ | 35.1 | 10.4 | 142.8 |

| K+ | 7.0 | 144.0 | 5.5 |

| Cl− | 35.2 | 18.4 | 117.5 |

| 4.0 | 9.0 | 26.9 | |

| CO2 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| 1.4 | 9.2 | 1.9 | |

| 4.7 | 9.0 | 0.6 | |

| Urea | 11.7 | 5.1 | 4.7 |

| 4.7 | 1.4 | 0.5 | |

| Imp | 92.1 | ||

| pH | 6.29 | 6.81 | 7.28 |

| Cotransporter fluxes, nmol/s/cm2 | |||

| NCC(Na) | 4.37 | ||

| NHE2(Na) | 0.52 | ||

| NHE2(H) | −0.31 | ||

| NHE2(NH4) | −0.10 | ||

| Case B2 | Lumen | Cell | Interstitium |

|---|---|---|---|

| PD, mV | −10.4 | −88.3 | |

| Concentrations, mM | |||

| Na+ | 57.3 | 8.1 | 143.0 |

| K+ | 6.6 | 147.3 | 5.5 |

| Cl− | 61.3 | 12.8 | 117.4 |

| 1.9 | 8.9 | 27.1 | |

| CO2 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| 0.7 | 10.3 | 1.9 | |

| 5.0 | 10.0 | 0.6 | |

| Urea | 10.4 | 5.0 | 4.7 |

| 5.8 | 0.9 | 0.4 | |

| Imp | 94.7 | ||

| pH | 5.97 | 6.81 | 7.29 |

| Cotransporter fluxes, nmol/s/cm2 | |||

| NCC(Na) | 1.86 | ||

| NHE2(Na) | 0.92 | ||

| NHE2(H) | −0.38 | ||

| NHE2(NH4) | −0.46 | ||

NCC, NaCl cotransporter; NHE2, Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 2; Imp, cytosolic impermeant.

Regulated Transport: TGF Is Off

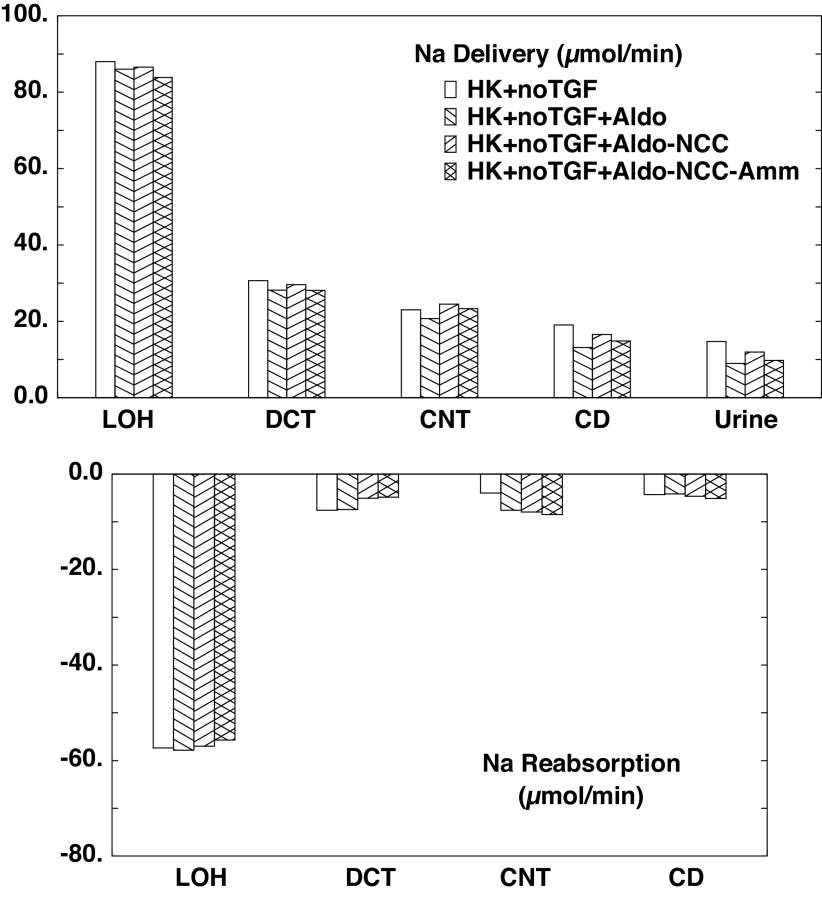

Here the impact of transport regulation is examined with TGF turned off and GFR set to the value computed in normokalemia, so that the baseline for comparison of regulatory features is A3. Table 3 shows interstitial concentrations determined by the three calculations of this section. In general terms, the higher GFR for these cases propagates into higher urine flow rates, with some degree of medullary washout. Thus, compared with the medullary concentrations computed for B1−B3, the interstitial K+ profiles are lower. The flows and fluxes associated with these simulations are shown in Table 9 and Figs. 8–10. With respect to Na+ transport (Fig. 8), the aldosterone effect to increase transport in CNT is evident, and it translates into reduced delivery in the CD and final urine. What is less obvious is how aldosterone can act to reduce LOH delivery, i.e., to enhance PT Na+ reabsorption. With reference to Table 3, the impact of increased CNT K+ secretion is to decrease cortical interstitial K+ concentration from 5.9 to 5.5 mM, thus reducing peritubular K+ inhibition of Na+ transport. The impact of NCC inhibition is also apparent in its contribution to increased urine Na+. Reduced ammoniagenesis produces a small drop in LOH Na+ delivery, indicative of enhanced PT Na+ reabsorption, and this also propagates to reduce Na+ excretion. In this case, the explanation of the change in PT transport is more convoluted: in the late PT, there is diffusive paracellular reabsorptive flux of , which acts to blunt luminal fluid acidification. This backflux is less in C3 compared with C2, so that end-PT concentrations are 15.8 mM (C3) and 16.7 mM (C2). The osmotic effect of lower luminal increases paracellular volume reabsorption and thus enhances convective Na+ flux across tight junctions. Regardless of the subtle differences of Na+ transport produced by these regulatory features, all cases show between 50% and 100% greater Na+ excretion than at baseline (A1).

Table 9.

Whole kidney flows and fluxes in hyperkalemia with regulated transport and no tubuloglomerular feedback

| Case C1 | PCT | LOH | DCT | CNT | CD | Urine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delivery | ||||||

| Na+, µmol/min | 217.2 | 86.0 | 28.2 | 20.7 | 13.1 | 9.0 |

| K+ | 9.80 | 3.75 | 1.05 | 1.45 | 4.29 | 3.20 |

| 0.15 | 0.63 | 0.34 | 1.04 | 1.30 | 0.94 | |

| Fv, µL/min | 1,508 | 600 | 281 | 263 | 175 | 66 |

| Relative to filtered load | ||||||

| Na+ | 100.0% | 39.6% | 13.0% | 9.5% | 6.1% | 4.1% |

| K+ | 100.0% | 38.3% | 10.7% | 14.8% | 43.7% | 32.6% |

| 100.0% | 426.9% | 228.9% | 698.9% | 880.7% | 634.2% | |

| F v | 100.0% | 39.8% | 18.6% | 17.5% | 11.6% | 4.4% |

| Reabsorption | Total | |||||

| Na+, µmol/min | 131.2 | 57.9 | 7.5 | 7.6 | 4.1 | 208.2 |

| K+ | 6.05 | 2.71 | −0.40 | −2.83 | 1.09 | 6.61 |

| −0.48 | 0.29 | −0.70 | −0.27 | 0.37 | −0.79 | |

| Jv, µL/min | 909 | 319 | 17 | 88 | 109 | 1442 |

| Relative to filtered load | ||||||

| Na | 60.4% | 26.6% | 3.4% | 3.5% | 1.9% | 95.9% |

| K | 61.7% | 27.6% | −4.1% | −28.9% | 11.1% | 67.4% |

| NH4 | −326.9% | 198.1% | −470.0% | −181.8% | 246.5% | −534.2% |

| J v | 60.2% | 21.2% | 1.2% | 5.8% | 7.2% | 95.6% |

| Case C2 | PCT | LOH | DCT | CNT | CD | Urine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delivery | ||||||

| Na+, µmol/min | 217.2 | 86.6 | 29.6 | 24.5 | 16.6 | 12.0 |

| K+ | 9.80 | 3.78 | 0.96 | 1.41 | 4.24 | 3.39 |

| 0.15 | 0.59 | 0.26 | 1.02 | 1.28 | 1.00 | |

| Fv, µL/min | 1,508 | 603 | 288 | 273 | 198 | 82 |

| Relative to filtered load | ||||||

| Na+ | 100.0% | 39.9% | 13.6% | 11.3% | 7.6% | 5.5% |

| K+ | 100.0% | 38.5% | 9.8% | 14.4% | 43.2% | 34.6% |

| 100.0% | 397.5% | 173.2% | 688.9% | 865.7% | 676.5% | |

| F v | 100.0% | 40.0% | 19.1% | 18.1% | 13.1% | 5.5% |

| Reabsorption | Total | |||||

| Na+, µmol/min | 130.6 | 57.0 | 5.1 | 7.9 | 4.6 | 205.3 |

| K+ | 6.03 | 2.82 | −0.46 | −2.82 | 0.84 | 6.41 |

| −0.44 | 0.33 | −0.76 | −0.26 | 0.28 | −0.85 | |

| Jv, µL/min | 905 | 315 | 15 | 75 | 116 | 1426 |

| Relative to filtered load | ||||||

| Na | 60.1% | 26.2% | 2.3% | 3.7% | 2.1% | 94.5% |

| K | 61.5% | 28.8% | −4.7% | −28.8% | 8.6% | 65.4% |

| NH4 | −297.5% | 224.4% | −515.7% | −176.8% | 189.2% | −576.5% |

| J v | 60.0% | 20.9% | 1.0% | 5.0% | 7.7% | 94.6% |

| Case C3 | PCT | LOH | DCT | CNT | CD | Urine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delivery | ||||||

| Na+, µmol/min | 217.2 | 83.8 | 28.1 | 23.3 | 14.9 | 9.8 |

| K+ | 9.80 | 3.58 | 0.72 | 1.21 | 4.42 | 3.64 |

| 0.15 | 0.31 | 0.11 | 0.55 | 0.70 | 0.55 | |

| Fv, µL/min | 1,508 | 583 | 276 | 260 | 182 | 71 |

| Relative to filtered load | ||||||

| Na+ | 100.0% | 38.6% | 13.0% | 10.7% | 6.8% | 4.5% |

| K+ | 100.0% | 36.5% | 7.4% | 12.3% | 45.0% | 37.1% |

| 100.0% | 208.1% | 77.6% | 372.0% | 475.7% | 373.3% | |

| F v | 100.0% | 38.7% | 18.3% | 17.2% | 12.1% | 4.7% |

| Reabsorption | Total | |||||

| Na, µmol/min | 133.4 | 55.7 | 4.8 | 8.5 | 5.1 | 207.4 |

| K | 6.22 | 2.86 | −0.49 | −3.21 | 0.78 | 6.17 |

| NH4 | −0.16 | 0.19 | −0.44 | −0.15 | 0.15 | −0.40 |

| Jv, µL/min | 925 | 307 | 16 | 78 | 111 | 1,437 |

| Relative to filtered load | ||||||

| Na+, µmol/min | 61.4% | 25.7% | 2.2% | 3.9% | 2.4% | 95.5% |

| K+ | 63.5% | 29.2% | −5.0% | −32.7% | 8.0% | 62.9% |

| −108.1% | 130.5% | −294.5% | −103.7% | 102.4% | −273.3% | |

| Jv, µL/min | 61.3% | 20.4% | 1.1% | 5.2% | 7.4% | 95.3% |

CD, collecting duct from the cortical collecting duct through the inner medullary collecting duct; CNT, connecting tubule; DCT, distal convoluted tubule; Fv, axial volume flow; Jv, volume reabsorption; LOH, loop of Henle (all tubules from the proximal straight tubule through the cortical ascending Henle’s loop); PCT, all proximal convoluted tubules.

Figure 8.

Segmental accounting of whole kidney Na+ flows (delivery) and fluxes (transport), in hyperkalemia, with tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF) fixed at its normokalemic value (A1). Negative transport values correspond to reabsorptive fluxes. As in Fig. 5, the bars correspond to incremental regulatory responses: open bars denote unregulated hyperkalemia (HK + no TGF; A3); backslash bars indicate aldosterone (Aldo) action, a doubling of the density of the epithelial Na+ channel and Na+-K+-ATPase in principal cells (HK + no TGF + Aldo; C1); forward slash bars adds an 80% reduction in NaCl cotransporter density (HK + no TGF + Aldo-NCC; C2); and cross-hatched bars add a halving of ammoniagenesis (HK + no TGF + Aldo-NCC-Amm; C3). Proximal delivery and reabsorption are available in Table 9 but are not depicted. CD, collecting duct; CNT, connecting tubule; DCT, distal convoluted tubule; LOH, loop of Henle.

K+ transport for this series is shown in Fig. 9, where the aldosterone effect provides the dominant increase in K+ excretion. NCC reduction does little to augment urine K+, as that effect was based on increasing CD urine flow and blunting K+ reabsorption there. The impact of reducing peritubular on CNT K+ secretion persists and is little influenced by the increase in flow: comparing B3 with B2, the increase in CNT K+ secretion was 0.49 µmol/min, whereas the difference between C3 and C2 was 0.39 µmol/min. Figure 10 shows ammonia handling in hyperkalemia, in the absence of TGF. Compared with Fig. 7 (TGF on), all of the values for delivery and reabsorption are higher, reflecting the higher GFR and the dependence of ammoniagenesis on PCT flow. Nevertheless, the increase in DCT secretion due to NCC inhibition persists. With reduced ammoniagenesis, reduced delivery, reabsorption, and secretion are observed along the nephron. Again, the combination of NCC reduction and reduced ammoniagensis (C3) mitigates derangement of acid-base balance. At baseline (A3), net acid excretion is 0.72 µmol/min, 1.19 µmol/min with aldosterone (C1), 1.26 µmol/min with NCC inhibition (C2), and 0.93 µmol/min when reduced ammoniagenesis is superimposed (C3).

Figure 9.

Segmental accounting of whole kidney K+ flows (delivery) and fluxes (transport), in hyperkalemia, with tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF) fixed at its normokalemic value (A1). Negative or positive transport values correspond to reabsorptive or secretory fluxes. As in Fig. 8, open bars denote unregulated hyperkalemia (HK + no TGF; A3); backslash bars indicate aldosterone (Aldo) action, a doubling of the density of the epithelial Na+ channel and Na+-K+-ATPase in principal cells (HK + no TGF + Aldo; C1); forward slash bars adds an 80% reduction in NaCl cotransporter density (HK + no TGF + Aldo-NCC; C2); and cross-hatched bars add a halving of ammoniagenesis (HK + no TGF + Aldo-NCC-Amm; C3). The values shown are those in Table 9. Because of the higher glomerular filtration rate, there are higher distal flows, so that the Aldo action to augment K+ excretion is most prominent; the other regulatory responses are less potent. CD, collecting duct; CNT, connecting tubule; DCT, distal convoluted tubule; LOH, loop of Henle; PCT, proximal convoluted tubule.

Figure 10.

Segmental accounting of whole kidney flows (delivery) and fluxes (transport), in hyperkalemia, with tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF) fixed at its normokalemic value (A1). Negative or positive transport values correspond to reabsorptive or secretory fluxes. As in Fig. 8, open bars denote unregulated hyperkalemia (HK + no TGF; A3); backslash bars indicate aldosterone (Aldo) action, a doubling of the density of the epithelial Na+ channel and Na+-K+-ATPase in principal cells (HK + no TGF + Aldo; C1); forward slash bars adds an 80% reduction in NaCl cotransporter density (HK + no TGF + Aldo-NCC; C2); and cross-hatched bars add a halving of ammoniagenesis (HK + no TGF + Aldo-NCC-Amm; C3). The values shown are those in Table 9. Halving of ammoniagenesis is evident in the reduced secretion in the proximal convoluted tubule (PCT) and distal convoluted tubule (DCT), and urinary excretion has normalized (comparing A1). CD, collecting duct; CNT, connecting duct; LOH, loop of Henle.

DISCUSSION

The kidney model of this laboratory was recently advanced with representation of the interstitium of the cortical labyrinth and MR (21). This introduced a second avenue for communication between the proximal and distal nephron, in addition to TGF and to the well-studied interaction between LOH and CD within the medulla. That model capability was first applied to examining the problem of directing proximally generated ammonia into the final urine rather than into renal venous blood. Specifically, ammonia generated within the PCT set the cortical ammonia concentration and thus modulated DCT ammonia secretion. In this work, the model was applied to the response to hyperkalemia. It is a classic finding from micropuncture that the CNT is the critical segment for K+ secretion, where it is controlled by aldosterone, and that this secretion is enhanced by increasing CNT Na+ delivery. CNT Na+ delivery is not a trivial modulator, as is clinically apparent in the hyperkalemia that presents when renal perfusion is poor and proximal reabsorption is increased (e.g., with dehydration or heart failure). Recent interest has focused on this aspect of K+ handling, following the observation that increases in cortical interstitial K+ downregulate NCC activity via a direct effect on DCT cytosolic Cl− and a downstream cascade of kinases. In view of the fact that peritubular K+ can also blunt Na+ reabsorption within the PCT and AHL, there was an obvious application of the model to estimating the relative importance of each of these antecedent segments in determining CNT Na+ delivery. An additional modulator of K+ excretion, which has had less attention but which this model captures, is that proximally generated ammonia can also impact K+ secretion. When cortical is taken up via peritubular Na+-K+()-ATPase, it acidifies principal cells. Thus, reduced ammoniagenesis can be expected to increase principal cell pH, thereby increasing conductance of both ENaC and ROMK.

Credibility of model analysis and predictions depends in large measure on how model flows and fluxes comport with experimental findings. There are several micropuncture studies of the renal response to acute hyperkalemia, and the three most comprehensive have been abstracted in Table 10. The format of Table 10 corresponds to that used in tables of flows and fluxes in this paper, namely each of the three sections shows entering solute flow (delivery) to the designated region and the transport of solute within that region. Specifically, PCT delivery (filtered load) corresponds to an early superficial PCT collection; LOH delivery is defined by late superficial PCT flow; and distal tubule (DT) and CD are determined by early and late superficial DT collections. For studies in which absolute delivery has been reported, Table 10 shows calculated delivery relative to filtered load; for studies in which relative delivery is reported, the absolute flows and fluxes were calculated. For each study, the reported values are shown in bold. All reabsorption values are determined here as the difference between regional delivery and the next flow determination. Specifically, when there are only PCT and DT flows, reabsorption under the PCT comprises transport by both the PCT and LOH; when there is no CD delivery determination, then reabsorption under the DT comprises both the DT and CD. It is important to note that to facilitate reference to the individual reports, the absolute flows that were published are reproduced in Table 10. This produces very different values for each study due to the reference weight of the rats. Wright et al. (30) reported all flows per 100 g of rat weight, Karlmark et al. (31) and Jaeger et al. (32) reported mean values for their group of large rats, and Sufit and Jamison (33) used smaller rats and reported filtration per gram of kidney weight, but otherwise their reported flows were fractional. Of note, the choice of 5.0 mEq/L for baseline blood K+ concentration has been a fixture throughout the development of this model, beginning with component tubule segments. That value had been motivated by micropuncture studies [e.g., Karlmark et al. (31)].

Table 10.

Micropuncture studies of acute hyperkalemia in the rat

| Control |

Acute KCl |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wright et al. (30), µmol/min/100 g body wt | |||||||||

| PCT | DT | CD | Urine | PCT | DT | CD | Urine | ||

| Absolute delivery | Absolute delivery | ||||||||

| Na+ | 69.5 | 4.5 | 1.6 | 0.4 | Na+ | 55.0 | 5.2 | 2.7 | 1.4 |

| K+ | 1.90 | 0.29 | 0.44 | 0.38 | K+ | 3.94 | 1.18 | 1.97 | 2.44 |

| Delivery relative to PCT delivery | Delivery relative to PCT delivery | ||||||||

| Na+ | 100.0% | 6.5% | 2.3% | 0.6% | Na+ | 100.0% | 9.5% | 4.9% | 2.5% |

| K+ | 100.0% | 15.3% | 23.2% | 20.0% | K+ | 100.0% | 29.9% | 50.0% | 61.9% |

| Absolute reabsorption | Absolute reabsorption | ||||||||

| Na+ | 65.0 | 2.9 | 1.2 | Na+ | 49.8 | 2.5 | 1.3 | ||

| K+ | 1.61 | −0.15 | 0.06 | K+ | 2.76 | −0.79 | −0.47 | ||

| Reabsorption relative to PCT delivery | Reabsorption relative to PCT delivery | ||||||||

| Na+ | 93.5% | 4.2% | 1.7% | Na+ | 90.5% | 4.5% | 2.4% | ||

| K+ | 84.7% | −7.9% | 3.2% | K+ | 70.1% | −20.1% | −11.9% | ||

| Karlmark et al. (31) and Jaeger et al. (32), µmol/min/320 g body wt | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCT | DT | CD | Urine | PCT | DT | CD | Urine | ||

| Absolute delivery | Absolute delivery | ||||||||

| Na+ | 361.1 | 28.2 | 13.7 | 3.3 | Na+ | 306.6 | 27.0 | 16.2 | 0.4 |

| K+ | 9.74 | 1.27 | 1.95 | 1.87 | K+ | 17.32 | 3.3 | 7.1 | 5.26 |

| 1.29 | 1.07 | 0.81 | 0.68 | ||||||

| Delivery relative to PCT delivery | Delivery relative to PCT delivery | ||||||||

| Na+ | 7.8% | 3.8% | 1.1% | Na+ | 8.8% | 5.3% | 0.2% | ||

| K+ | 13% | 20% | 22% | K+ | 19% | 41% | 41% | ||

| Absolute reabsorption | Absolute reabsorption | ||||||||

| Na+ | 332.9 | 14.4 | 10.4 | Na+ | 279.6 | 10.7 | 15.8 | ||

| K+ | 8.47 | −0.68 | 0.08 | K+ | 14.03 | −3.81 | 1.84 | ||

| Reabsorption relative to PCT delivery | Reabsorption relative to PCT delivery | ||||||||

| Na+ | 92.2% | 4.0% | 2.9% | Na+ | 91.2% | 3.5% | 5.2% | ||

| K+ | 87.0% | −7.0% | 0.8% | K+ | 81.0% | −22.0% | 10.6% | ||

| Sufit and Jamison (33), µmol/min/160 g body wt | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCT | LOH | DT | Urine | PCT | LOH | DT | Urine | ||

| Absolute delivery | Absolute delivery | ||||||||

| Na+ | 143.0 | 85.8 | 15.7 | 0.21 | Na+ | 167.0 | 93.5 | 18.4 | 1.32 |

| K+ | 4.00 | 2.64 | 0.68 | 0.25 | K+ | 7.08 | 4.46 | 1.84 | 3.33 |

| Delivery relative to PCT delivery | Delivery relative to PCT delivery | ||||||||

| Na+ | 60% | 11% | 0.2% | Na+ | 56% | 11% | 0.8% | ||

| K+ | 66% | 17% | 6.2% | K+ | 63% | 26% | 47.1% | ||

| Absolute reabsorption | Absolute reabsorption | ||||||||

| Na+ | 57.2 | 70.1 | 15.5 | Na+ | 73.5 | 75.2 | 17.1 | ||

| K+ | 1.36 | 1.96 | 0.43 | K+ | 2.62 | 2.62 | −1.49 | ||

| Reabsorption relative to PCT delivery | Reabsorption relative to PCT delivery | ||||||||

| Na+ | 40.0% | 49.0% | 10.9% | Na+ | 44.0% | 45.0% | 10.2% | ||

| K+ | 34.0% | 49.0% | 10.8% | K+ | 37.0% | 37.0% | −21.1% | ||

CD, collecting duct; DT, distal tubule; LOH, loop of Henle; PCT, proximal convoluted tubule. For studies in which absolute delivery has been reported. This table shows calculated delivery relative to filtered load; for studies in which relative delivery is reported, then the absolute flows and fluxes were calculated. For each study, the reported values are shown in bold.

In assessing the renal response to hyperkalemia, changes in GFR are foundational, as tubular flow is critical to all downstream Na+ and K+ transport. The data in Table 10 show that Wright et al. (30) found a 21% GFR reduction with acute hyperkalemia and determined that this difference was significant. Karlmark et al. (31) reported a 15% GFR reduction, but its statistical significance was not noted. In contrast, Sufit and Jamison (33) documented a nonsignificant 17% GFR increase. It should be noted that with their protocol, Sufit and Jamison (33) appeared to be working with rats that were relatively volume depleted (as assessed by the rates of cation excretion), and the KCl infusion may have provided a volume rescue. With the TGF formulated for this model (Eq. 1), hyperkalemia reduced GFR by 14%, due to increases in cytosolic Cl− in the late cortical AHL (macula densa). When TGF was introduced into this model, this TGF function provided a response of GFR to variation of AHL flow that resembled experimental curves (22). That work acknowledged the macula densa model of Edwards et al. (34), who favored peritubular electrical potential as the TGF signal (with depolarization reducing GFR), but it was also indicated that the two choices for the signal variable yielded congruent TGF curves (22). In this study (Table 5), hyperkalemia induced both an increase in macula densa cytosolic Cl− (16.5 to 19.1 mM) and peritubular depolarization (−87.2 to −81.1 mV), so that either representation would have predicted TGF activation and a reduction in GFR. Although the TGF signal is known to be dependent on luminal K+ (35), perhaps the study most germane to the simulations of this paper is that of Braam et al. (36), who examined TGF in rats subjected to acute hyperkalemia. In that work, K+ infusion increased serum K+ from 4.56 to 5.76 mM, but there were no associated changes in SNGFR, nor were there any changes in the distal delivery of Na+ or K+. With respect to this negative finding, the model perspective (Table 3) is that CNT K+ secretion renders cortical interstitial K+ less than in systemic plasma, so it may be that the systemic K+ increase of the Braam et al. study did not yield a comparable bump in cortical K+. A positive finding of Braam et al. (36) came with direct examination of the impact of LOH perfusion on GFR, in which they observed attenuation of the TGF signal. This finding suggests that in the event of K+-induced proximal natriuresis, a diminished TGF would be less likely to nullify the increase in distal Na+ delivery.

In the initial presentation of this kidney model, the impact of acute hyperkalemia on tubular Na+ transport was examined in detail (20). In the model PCT, Na+ reabsorption is blunted by an increase in cortical interstitial K+, due to its depression of peritubular Cl− and exit; the resulting cytosolic alkalinization decreases luminal NHE3 activity. In the model of this paper, when TGF is silenced and GFR is unchanged, hyperkalemia reduced fractional proximal Na+ reabsorption from 63.1% to 59.5%, so that LOH Na+ delivery increased from 80 to 88 µmol/min and DCT Na+ delivery increased by 50%, from 19.8 to 30.6 µmol/min (Table 4, comparing A3 with A1). With active TGF (A2), the combination of reduced GFR and lower fractional PT Na+ reabsorption (60.9%) reduced LOH Na+ delivery from 80 to 73 µmol/min, and then the K+-induced depression of AHL Na+ transport provided the DCT with Na+ delivery only slightly lower than normal 18.1 µmol/min (comparing A2 with A1). It is important to acknowledge that in the initial version of this model (20), MR blood vessels were a countercurrent system, oriented from the cortex to medulla, whereas the recent update has MR vessels entering and exiting laterally along its corticomedullary axis (21). With the original configuration of MR vessels, the systemic K+ increase (from 5.0 to 5.5 mM) did not perturb peritubular K+ near the macula densa. As a consequence, TGF was not activated and the proximal tubular K+ impact was unmitigated, as in A3 and C1−C3 of this work. With reference to Table 10, Wright et al. (30) found that KCl infusion induced a 16% increase in absolute Na+ delivery to the DT, which in view of the lower GFR was an increase in fractional delivery from 6.5% to 9.5% of filtered load, and they attributed this to K+-induced suppression of PT Na+ reabsorption. Karlmark et al. (31) found a small decrease in absolute Na+ delivery to the DT, but which also translated into an increase in fractional delivery from 7.8% to 8.8%. In the study of Sufit and Jamison (33), K+-induced absolute DT Na+ delivery was higher, consistent with the increase in GFR, so that fractional delivery was unchanged from control. In short, the experimental findings suggest that a combination of reduced filtration and lower Na+ reabsorption was homeostatic with respect to DT Na+ delivery.

With regard to the impact of hyperkalemia on DT Na+ transport, only the two studies with both early and late distal punctures can address this issue. It is important to remember that in the micropuncture literature, the “distal tubule” comprised segments from both the DCT and CNT. In the study of Wright et al. (30), hyperkalemia reduced absolute DT Na+ reabsorption by 14% (from 2.9 to 2.5 µmol/min/100 g body wt); Karlmark et al. (31) observed a 26% decrease (from 14.4 to 10.7 µmol/min/320 g body wt.). Both studies reported that under control conditions, DT Na+ reabsorption dwarfed K+ secretion by a factor of 20; with hyperkalemia, this ratio was ∼3. With reference to Table 6 (B3), the ratio of CNT Na+ reabsorption to K+ secretion is 2.7, and this factor is approximately the case for all of the hyperkalemic simulations. If this transport ratio holds for the rat CNT, then this suggests that hyperkalemia has shifted most of the DT Na+ reabsorption from the DCT to the CNT. This finding is certainly supportive of the importance of the studies that have identified the impact of hyperkalemia on NCC dephosphorylation (9, 10). When referred to a 300-g rat, the observed values of DT Na+ reabsorption and K+ secretion are 7.5 and 2.5 µmol/min in the study of Wright et al. (30), and 10.0 and 3.6 µmol/min in the study by Karlmark et al. (31). Of note, both studies were performed in male rats. In the model of this paper, with regulated transport and active TGF (B3), these values are 12.3 and 3.5 µmol/min for the combined DCT-CNT (micropuncture DT); absent TGF (C3), they are 13.3 and 3.7 µmol/min for the combined DCT-CNT. The ratios of these DT fluxes are 3.5 and 3.6 with and without TGF, respectively. Acknowledging that micropuncture did not access the full extent of these segments, the concordance of fluxes provides some assurance that the model kidney is faithfully representing rat kidney transport.

In the whole animal, there is a reciprocal relationship between excretion of K+ and . Glutamine ingestion enhances ammoniagenesis and acutely decreases K+ excretion (37). Conversely, K+ ingestion acutely decreases excretion (14). In rat renal cortical slices examined in vitro, a high-K+ diet before euthanasia depressed ammoniagenesis, while slices from rats on a low-K+ diet showed greater ammoniagenesis (15). The clinical correlate is the defect in excretion in chronic hyperkalemia and its consequent metabolic acidosis (38). With respect to ammonia transport, Jaeger et al. (32) found that an acute K+ load significantly decreased late DT flow and reduced excretion by close to 40%. With the acute K+ load, they could not document a difference in flow in either the late PT or early DT, leaving the conclusion that the drop in excretion was due to reduced DT secretion. In this model, comparing normokalemia (A1) with fully regulated hyperkalemia (B3), CD delivery fell from 1.05 to 0.61, capturing the findings of Jaeger et al., although reductions in tubular secretion were predicted in both proximal and distal segments. With respect to K+ transport, the finding of this model is that a reduction in PT ammoniagenesis enhanced K+ excretion by 25%, even with aldosterone stimulation and NCC reduction in place (comparing B3 with B2). The mechanism in the model is that reduced ammoniagenesis decreased cortical concentration, which raised principal cell pH, which, in turn, increased the conductance of ENaC and ROMK. In short, the reduction in ammoniagenesis with hyperkalemia facilitated CNT K+ secretion by modulating channel conductance and was not dependent on changes in tubular flow.

One notable model observation relates to urinary acidification by the DCT. The model predicts that isolated NCC inhibition will increase NHE2-mediated Na+ reabsorption, either exchanging for protons or , by virtue of the reduction in cytosolic Na+ (Table 8). This recapitulates the finding of increased urinary acidification by the DCT in a distal nephron model simulation of the effect of thiazides (39). That model observation was thought to have possible relevance to diuretic-induced metabolic alkalosis. In this model, the impact of the increase in NHE2 activity was to mitigate the reduction in net acid excretion that came with reduced ammoniagenesis. There is, however, little in the way of experimental support for this model finding. In their micropuncture study, Karlmark et al. (31) found that, compared with control, K+ infusion reduced the increase in titratable acid along the DT. This suggests reduced DT proton secretion but does not distinguish between NHE2 transport and secretion by the proton-ATPases of CNT α-cells. There have been a limited number of micropuncture perfusion studies that have examined early DT and late DT transport independently (tabulated in Ref. 16). Ellison et al. (40) found that thiazides completely abolished DCT Na+ reabsorption, while eliminating lumen Cl− in the perfusate preserved ∼30% of Na+ reabsorption. Ellison et al. interpreted the residual Na+ flux as the result of luminal Cl− availability, due to secretory backflux. Alternatively, Wang et al. (41) documented early distal reabsorption at a rate that was ∼30% of Na+ flux. There seem to be no studies that have addressed the issue of NHE2 flux in relation to acute hyperkalemia, specifically, whether the regulatory cascade that modulates NCC also affects NHE2 activity.

In summary, it is secure that the renal response to hyperkalemia is mediated by increased K+ secretion by the CNT, and it is also secure that this flux is modulated by direct tubular effects (e.g., aldosterone) in conjunction with increased luminal flow of fluid and Na+. There is ample evidence that an increase in peritubular K+ blunts upstream Na+ reabsorption in the PT, thick AHL, and DCT. The model tubules capture these segmental transport effects, which in the case of the PT are substantial in relation to distal Na+ delivery. The simulation of hyperkalemia in this study forces the question of the extent to which increased Na+ delivery gets transmitted past the macula densa and its TGF signal. Beyond the direct effect of luminal Na+ to activate TGF, high peritubular K+ is predicted to raise cytosolic Cl− and depolarize macula densa cells, and each has been considered integral to TGF signaling. In this paper, the two sets of simulations bracket the possibilities that TGF either is effective in stabilizing distal Na+ delivery or fails to be activated with hyperkalemia and permits natriuresis. Experimental evidence suggests TGF activation in acute hyperkalemia, so that even though upstream changes in Na+ flux may be larger, it may be the reduction in DCT Na+ reabsorption that is critical to increasing CNT delivery. That hyperkalemia reduces ammoniagenesis and that reduced ammoniagenesis can enhance K+ excretion is also secure. What the model adds to this discussion is a possible mechanism, namely that hyperkalemic reduction of renal cortical ammonia can impact CNT transport, by raising cell pH and thus enhancing both ENaC and ROMK conductance.

DATA AVAILABLITY

All of the model computer codes and references to model publications may be found on the GitHub website at https://github.com/amweins/kidney-models-amw.

GRANTS

This investigation was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant R01DK29857.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.M.W. conceived and designed research; performed experiments; analyzed data; interpreted results of experiments; prepared figures; drafted manuscript; edited and revised manuscript; and approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author appreciates the critical reading of this manuscript by Dr. Lawrence G. Palmer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berliner RW, Kennedy TJ Jr, Hilton JG. Renal mechanisms for excretion of potassium. Am J Physiol 162: 348–367, 1950. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1950.162.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malnic G, Klose RM, Giebisch G. Micropuncture study of renal potassium excretion in the rat. Am J Physiol 206: 674–686, 1964. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1964.206.4.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malnic G, Klose RM, Giebisch G. Micropuncture study of distal tubular potassium and sodium transport in rat nephron. Am J Physiol 211: 529–547, 1966. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1966.211.3.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sansom SC, O'Neil RG. Mineralocorticoid regulation of apical cell membrane Na+ and K+ transport of the cortical collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 248: F858–F868, 1985. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1985.248.6.F858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]