Abstract

Nuclear pore complexes (NPCs) are membrane-embedded gatekeepers of traffic between the nucleus and cytoplasm. Key features of the NPC symmetric core have been elucidated, but little is known about the NPC basket, a prominent structure with numerous roles in gene expression. Studying the basket was hampered by its instability and connection to the inner nuclear membrane (INM). Here, we reveal the assembly principle of the yeast NPC basket by reconstituting a recombinant Nup60-Mlp1-Nup2 scaffold on a synthetic membrane. Nup60 serves as the basket’s flexible suspension cable, harboring an array of short linear motifs (SLiMs). These bind multivalently to the INM, the coiled-coil protein Mlp1, the FG-nucleoporin Nup2, and the NPC core. We suggest that SLiMs, embedded in disordered regions, allow the basket to adapt its structure in response to bulky cargo and changes in gene expression. Our study opens avenues for the higher-order reconstitution of basket-anchored NPC assemblies on membranes.

The nuclear pore basket is assembled on a flexible, membrane-tethered “suspension cable.”

INTRODUCTION

Nuclear pore complexes (NPCs) fuse the inner nuclear membrane (INM) and outer nuclear membrane (ONM) to create a specialized pore membrane and a channel between the cytoplasm and nucleoplasm (1). NPCs do not only regulate nucleocytoplasmic transport but also influence genome architecture and gene expression (2–5), and their misfunction causes human diseases (6, 7). In budding yeast, each 52-MDa NPC consists of ~30 different proteins termed nucleoporins or Nups, which are present in multiple copies adding up to ~550 Nups per NPC (8–10). Nups fall into four classes: transmembrane, core scaffold, linker, and Phe-Gly (FG) Nups. The key structural elements of the NPC are the inner ring, which is located at the crest of the fused INM and ONM; the cytoplasmic ring and the nuclear ring, which are both anchored at the inner ring; and two peripheral appendages, the cytoplasmic filaments and the nuclear basket, which emanate from the cytoplasmic and nuclear ring, respectively (11–16). The central NPC channel is lined by FG Nups, which establish the permeability barrier and interact with shuttling transport receptors. The Y complex is the main component of the cytoplasmic and nuclear rings where it oligomerizes in a head-to-tail fashion (9, 11, 15–19). Numerous other interaction surfaces including several short linear motifs (SLiMs) (20) in scaffold and linker Nups establish connections within the NPC core scaffold (9, 15, 21–24).

The nuclear basket is a conical, cage-like structure, originally called a “fishtrap” (25–27). A multitude of functions have been assigned to it including the exclusion of (hetero-) chromatin to keep free access to the NPC channel (28, 29), the interconnection of neighboring NPCs (30), ribonucleoprotein (RNP) particle docking before export (31), the selection of export-competent and the retention of faulty mRNAs (32), and protein quality control (33), as well as the physical tethering and regulation of genes via basket-associated adaptors (2–5). The FG regions of basket Nups also contribute to the permeability barrier that confers selectivity and specificity to the NPC (34, 35). Some basket Nups provide docking sites for shuttling transport receptors, mostly of the karyopherin family. How this multitude of functions is encoded in the basket’s architecture is unclear but likely requires a substantial structural plasticity to allow simultaneous interactions with chromatin and various macromolecular complexes.

Electron microscopy (EM) studies, performed in amphibia, insects, slime mold, and yeast (12, 25–27, 36), have revealed an intricate basket architecture that comprises eight filaments joined distally by a ring. The height of the basket varies between species (~60 to 120 nm) (12, 37). The basket filaments appear to be anchored to the Y complex according to recent cryo–electron tomography (cryo-ET) and integrative structural analyses (9, 11). The basket is a flexible structure in situ because the transport of large messenger RNPs (mRNPs) can lead to major distortion, which is reversed after passage (38). The structural basis for this phenomenon is unclear but could serve to restore the NPC’s permeability barrier after the transport of bulky cargo.

Basket Nups are among the most dynamic components of the NPC; although their protein turnover is slow, their exchange rates within the NPC are fast, indicating a continuous swapping of basket-bound Nups with Nups from a free pool (39, 40). Posttranslational modifications may further regulate basket structure in cells (41). It is unknown how the basket can be dismantled and reassembled so easily. Yeast NPCs adjacent to the nucleolus lack basket filaments (30, 32), underscoring the structural heterogeneity of the nucleoplasmic face of the NPC.

In yeast, the nuclear basket is composed of Nup1, Nup2, Nup60, and the paralogs Myosin-like protein 1 and 2 (Mlp1/Mlp2). Mlp1 and Mlp2 are large coiled-coil proteins (~200 kDa) that can form homo- and heterodimers in cells and form the eight basket filaments (29). The metazoan basket harbors only three Nups, NUP153 (a likely ortholog of yeast Nup1/Nup60), NUP50 (Nup2), and TPR (Mlp1/2) (10). The stoichiometry of yeast basket Nups has been estimated as either 8 or 16 copies for Nup60, Mlp1, or Mlp2, depending on the technical approach (Nup2 was not determined) (9, 42, 43). On the basis of immuno-EM, cryo-ET, and biochemical studies, the position of some basket Nups has been coarsely approximated (9, 11, 29, 44–47). While the structural backbone of the basket filaments is likely formed by the Mlp/TPR coiled-coil proteins, a considerable portion of the basket may be unstructured. Nup1, Nup2, and Nup60 are rich in FG repeats, with other short motifs interspersed.

Basket Nups may have a key role in forming the NPC pore and embedding NPCs. The NPC pore membrane exhibits both convex and concave curvatures. Given that lipid bilayers tend to resist both bending and remodeling, forces have to be applied to curve and fuse the pore membrane during interphase NPC biogenesis (1, 48). This process involves an inside-out extrusion of the INM (49), which might be driven by INM-bound Nups. Notably, the nuclear basket proteins Nup1 and Nup60 can directly bind and remodel lipid bilayers (50), and this function is conserved in metazoa (51). Specifically, yeast Nup1 and Nup60 bend membranes in vitro via an amphipathic helix (AH), remodel the nuclear envelope (NE) in vivo when overexpressed, and protect NE integrity against membrane stress (50). All other putative membrane-deforming and curvature-sensing activities of the NPC map to symmetric components of the NPC core (9, 15, 19, 52–55). At present, Nup1, Nup60, and NUP153 are the only known asymmetric lipid-interacting parts of the NPC. Hence, understanding how membrane interactions are coupled to NPC biogenesis is imperative.

Structural biochemistry of the NPC basket can address these questions but has been challenging because (i) basket Nups are large (>200-kDa Mlp/TPR) or unstructured and appeared to exhibit low-affinity protein-protein interactions, (ii) the NPC basket cannot be purified as a stable entity from cells, (iii) the basket might be unstable in a nonlipid in vitro environment, and (iv), unlike the NPC core, the basket has not been amenable to high-resolution structural analyses. To overcome these obstacles, we have developed a “visual biochemistry” approach that combines membrane-supported Nup reconstitution with microscopic analysis. In doing so, we assembled a nuclear pore basket scaffold and revealed the existence of a “basket suspension cable,” which couples membrane recruitment with higher-order protein assembly.

RESULTS

A biomimetic system for Nup recruitment to the INM

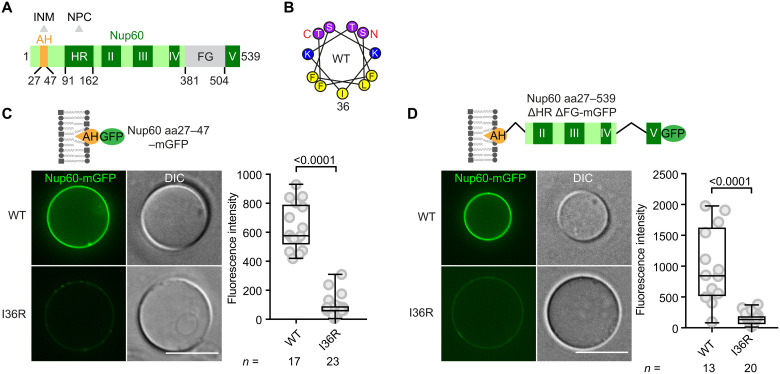

To recapitulate basket assembly at the INM, we first reconstituted basket (sub-) structures using fluorescently labeled recombinant proteins on a membrane support. We previously reported that the Nup60 amphipathic helix (termed Nup60AH; Fig. 1, A and B) cosedimented with large unilamellar vesicles (size range of 0.1 to 1 μm) made from Folch lipids, a crude lipid extract (50). We sought to improve this method by directly visualizing the stepwise recruitment of multiple Nups to a membrane of defined lipid composition. We used giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs; size range of 1 to 200 μm) because they allow rapid inspection by light microscopy. The lipid composition of the INM is unknown but differs from the ONM/endoplasmic reticulum (ER) because diacylglycerol (DAG) is specifically enriched at the INM (56). Hence, we used a lipid mix containing 1.0 mole percent (mol %) of DAG together with 46.3 mol % of POPE, 28.9 mol % of POPS, 18.9 mol % of POPC, and 4.9 mol % of PIP2 (see Materials and Methods for details). DAG incorporation into GUVs was confirmed with a DAG-specific sensor (fig. S1, A and B) (56). Recombinant Nup60AH (aa27–47; 100 nM protein), C-terminally tagged with monomeric green fluorescent protein (mGFP), was recruited to GUVs as shown by fluorescence/differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy and quantification of fluorescence intensity on the GUV membrane (Fig. 1C; see fig. S1C for input). Nup60AH recruitment was increased when GUVs contained 1.0 mol % of DAG, possibly because DAG facilitates the insertion of amphipathic helices into the lipid bilayer (fig. S1D) (57). Nup60 may encounter these conditions when binding to the DAG-rich INM in cells. Compromising Nup60 amphipathicity by introducing a charged amino acid at the hydrophobic side of the AH (I36R; Fig. 1B) diminished membrane binding (Fig. 1C and fig. S1C).

Fig. 1. Nup60 binds to GUVs via its amphipathic helix.

(A) Predicted motif organization of Nup60. An AH (orange) binds to the INM; the adjacent HR interacts with the NPC core. Other conserved regions (dark green) are numbered with roman numerals. FG, phenylalanine-glycine repeat region. Boundaries are drawn to scale. Relevant amino acid positions are indicated. (B) Helical wheel representation of the Nup60AH calculated with the HeliQuest algorithm. I36R substitution disrupts the hydrophobic face of the helix. WT, wild type. (C) GUV-binding assay. Representative fluorescence microscopy and DIC images of GUVs incubated with the indicated recombinant mGFP-tagged Nup60 constructs. Scale bar, 10 μm. The fluorescence signal at the membrane was quantified and is depicted as a box-whisker plot showing median, interquartile range, minimum and maximum value, and individual data points (gray circles). The number (n) of quantified GUVs is indicated. The P value from a two-tailed t test is indicated above the graph. See fig. S1C for protein input. (D) GUV-binding assay with the indicated recombinant proteins. Experimental setup, quantification, and statistics as in (C). Scale bar, 10 μm. See fig. S1E for protein input.

Nup60 harbors several conserved motifs distal to the AH, which we considered as potential protein-protein junctions (Fig. 1A). The α-helical region (HR; Nup60HR) was previously shown to target Nup60 to NPCs (50), but the function of motif II, III, IV, and V remained unknown. Obtaining a recombinant full-length Nup60 protein was hampered by its low expression/solubility and susceptibility to proteolysis. Hence, we engineered a construct lacking the HR (aa48–162) and the disordered FG repeat region (aa381–504) (Fig. 1D). This Nup60 construct (aa27–539ΔHRΔFG-mGFP; subsequently abbreviated as Nup60*) was successfully purified by a split approach, first pulling on an N-terminal His-tag and then on a C-terminal StrepII tag, thereby selecting for the full-length protein (fig. S1E). Nup60* bound efficiently to GUVs, and this required an intact AH as shown by the reduced membrane affinity of the Nup60* I36R mutant (Fig. 1D). We used Nup60 at concentrations that do not deform GUVs (50) so that we could now start to build larger membrane-anchored basket assemblies on a planar membrane.

A distinct Nup60 motif directly binds and recruits Mlp1 to membranes

The large coiled-coil proteins Mlp1 and Mlp2 (orthologs of vertebrate TPR) constitute the eight basket filaments (29, 45). A recent in situ cryo-ET model and an integrative structural model converge on the notion that the Mlp filaments associate with the Y complex (9, 11). On the other hand, Nup60 is also involved in the recruitment of Mlp1 and Mlp2 to the NPC (29, 58), because these proteins cluster into nucleoplasmic foci when NUP60 is deleted. A direct interaction between Nup60 and Mlp1/2 has not been demonstrated. Thus, how the Mlps are recruited to the NPC is still poorly understood.

To search for a Nup60 motif that binds Mlp1, we truncated Nup60-mCherry from its C terminus and examined the localization of Mlp1-GFP in cells (fig. S1F). Because Mlp1 and Mlp2 are paralogs, we focused on Mlp1 alone. The truncation of Nup60 up to aa318 did not affect Mlp1 localization, but a further shortening to aa239 caused a mislocalization of Mlp1 into bright fluorescent foci similar in appearance to the Mlp1 foci observed in nup60∆ cells [compare fig. S1F (bottom) and the Section ‘A network of SLiMs is essential for NPC basket integrity in vivo’]. Nup60 aa1–239 remained at the nuclear rim, consistent with the AH and HR mediating Nup60 NE/NPC anchorage (50). Thus, the conserved Nup60 aa240–318 region (motif III) is required for proper Mlp1 localization (fig. S2A).

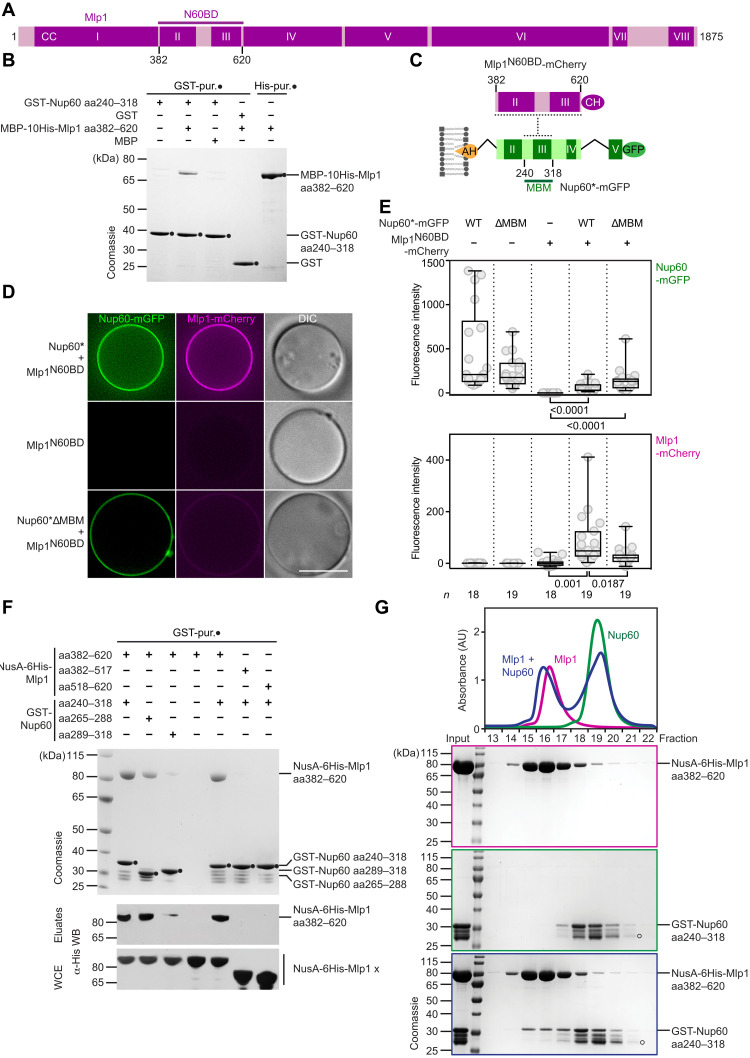

To establish whether Nup60 and Mlp1 interact directly, we performed in vitro binding assays with recombinant Nup60 and Mlp1 proteins. We focused on a region of Mlp1 (aa338–616) that was previously shown to exhibit a punctate, NPC-like pattern at the NE when expressed as a fragment in yeast (29). Considering amino acid conservation and structure predictions (Fig. 2A; fig. S2, B and C), we optimized a recombinant Mlp1 fragment (Mlp1 aa382–620) for interaction tests with glutathione S-transferase (GST)–tagged Nup60 aa240–318, the suspected Mlp1-binding motif of Nup60. Mlp1 aa382–620 was N-terminally tagged with Maltose-binding protein (MBP) to enhance its expression/solubility. GST-Nup60 aa240–318 copurified MBP-His-Mlp1 aa382–620 after both proteins were coexpressed in Escherichia coli, but it did not copurify MBP alone. Conversely, GST alone did not copurify MBP-His-Mlp1 aa382–620, confirming a specific Nup60-Mlp1 interaction (Fig. 2B and fig. S3A). We conclude that Nup60 aa240–318 [termed Nup60 Mlp1-binding motif (Nup60MBM)] directly interacts with Mlp1 aa382–620 [termed Mlp1 Nup60-binding domain (Mlp1N60BD)].

Fig. 2. A distinct Nup60 motif directly binds and recruits Mlp1 to membranes.

(A) Predicted coiled-coil (CC) organization of Mlp1 and its binding site with Nup60. CCs (dark magenta) are numbered by roman numerals; amino acid boundaries are drawn to scale. N60BD, Nup60-binding domain. For CC prediction, see fig. S2B. (B) Nup60 and Mlp1 directly interact. GST-Nup60 aa240–318 or GST alone (negative control) were coexpressed with MBP-10His-Mlp1 aa382–620 or MBP (negative control) in E. coli and subjected to GST-affinity purification. Proteins were eluted with glutathione and analyzed by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Coomassie staining. Right lane shows Ni-affinity purification of MBP-10His-Mlp1 aa382–620 for comparison. Bands were identified by mass spectrometry and immunoblotting (see fig. S3A). (C) Cartoon of the membrane-tethered Nup60-Mlp1 junction. The indicated protein constructs were used for the GUV assay in (D). MBM, Mlp1-binding motif. The Nup60* construct lacks the Nup60HR and Nup60FG regions. (D) GUV-binding assay. Representative fluorescence microscopy and DIC images of GUVs incubated with the indicated proteins. Scale bar, 10 μm. (E) Fluorescent signals at the membrane in (D) were quantified and depicted as box-whisker plots with median, interquartile range, minimum and maximum values, and individual data points (gray circles). The number (n) of quantified GUVs and the P values from a two-tailed t test are indicated. See fig. S3B for input. (F) GST-Nup60 constructs were coexpressed with NusA-6His-Mlp1 variants and subjected to GST-affinity purification. Protein eluates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, Coomassie staining, and immunoblotting against Mlp1. All Mlp1 variants were detectable in whole-cell extracts (WCEs). (G) Analytical size exclusion chromatography (SEC) of Nup60 and Mlp1 proteins in isolation and after preincubation. Absorbance profiles and corresponding Coomassie-stained gels are shown. Input is shown next to the size marker. Open circles indicate the degradation product of Nup60. See fig. S3D for GST only control.

Having established a direct Nup60-Mlp1 interaction, we determined whether Nup60, via its AH, is sufficient to recruit Mlp1 to a membrane. We incubated GUVs with recombinant Nup60*-mGFP and added recombinant Mlp1N60BD-mCherry (Fig. 2, C to E; see fig. S3B for input). We observed co-recruitment of Mlp1N60BD-mCherry and Nup60*-mGFP on the GUV surface (Fig. 2, D and E). In contrast, Mlp1N60BD alone did not bind GUVs as it lacks a membrane anchor. Moreover, a Nup60* construct without the Mlp1-binding motif (Nup60*ΔMBM) did not efficiently recruit Mlp1. The fluorescence intensity of Nup60 and Mlp1 on GUVs shows some variability between different GUVs; however, the higher the amount of Nup60, the higher the amount of Mlp1 recruited (R2 = 0.8792) (fig. S3C).

Next, we aimed to identify the minimally interacting regions of Nup60 and Mlp1 by further dissecting the Nup60MBM and the Mlp1N60BD. For this new set of Mlp1 constructs, we exchanged the MBP tag against a NusA tag as it further improved Mlp1 expression/solubility and then coexpressed Nup60 and Mlp1 in E. coli. GST pull-down experiments showed that the Nup60MBM can be subdivided into two SLiMs, both of which bind Mlp1N60BD, albeit with lower affinity compared to the entire Nup60MBM (Fig. 2F). The first SLiM comprises a predicted short α helix (Nup60 aa265–288), and the second SLiM comprises a disordered region (Nup60 aa289–318) (fig. S2A). The Mlp1N60BD comprises two predicted coiled coils (designated II and III), which are connected by a presumably flexible linker (fig. S2, B and C). GST-Nup60MBM did not efficiently bind to either Mlp1 coiled-coil II (aa382–517) or III (aa518–620), suggesting that both regions of Mlp1 must be present for binding to Nup60 (Fig. 2F).

Because of its importance for Mlp1 recruitment to NPCs, we sought to reconstitute this interaction in vitro. Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) revealed two distinct peaks of NusA-Mlp1N60BD and GST-Nup60MBM when analyzed individually (Fig. 2G). However, after preincubating the proteins together, a fraction of Nup60 comigrated with Mlp1, indicating complex formation. In contrast, GST alone, used as a control, did not shift NusA-Mlp1N60BD into a higher molecular weight fraction (fig. S3D). Multiangle light scattering experiments showed that the Mlp1N60BD exhibits an absolute molar mass corresponding to a dimer, consistent with being a predicted coiled-coil protein (fig. S3E).

In sum, we have reconstituted the direct link between Nup60 and Mlp1, which features SLiMs in Nup60 binding to an interrupted coiled-coil domain of Mlp1. By using its N-terminal AH as a lipid anchor, Nup60 couples membrane binding and the recruitment of the basket filaments.

Conserved SLiMs form a Nup60-Nup2 basket junction

Nup2 (metazoan NUP50) plays an important role in the disassembly of import complexes in the nucleoplasm (59). Nup2 displaces mono- and bipartite nuclear localization sequence (NLSs) from Kap60 (importin-α) after import. Nup2 also binds RanGTP and Cse1 (the export carrier of Kap60/importin-α) to increase their local concentration at the basket (see Fig. 3A for binding sites). In doing so, Nup2 accelerates cargo disassembly and recycling of import complexes. Nup2 was shown to associate with Nup60 (60); however, the precise binding site(s) and how these interactions contribute to the basket’s architecture had remained unclear.

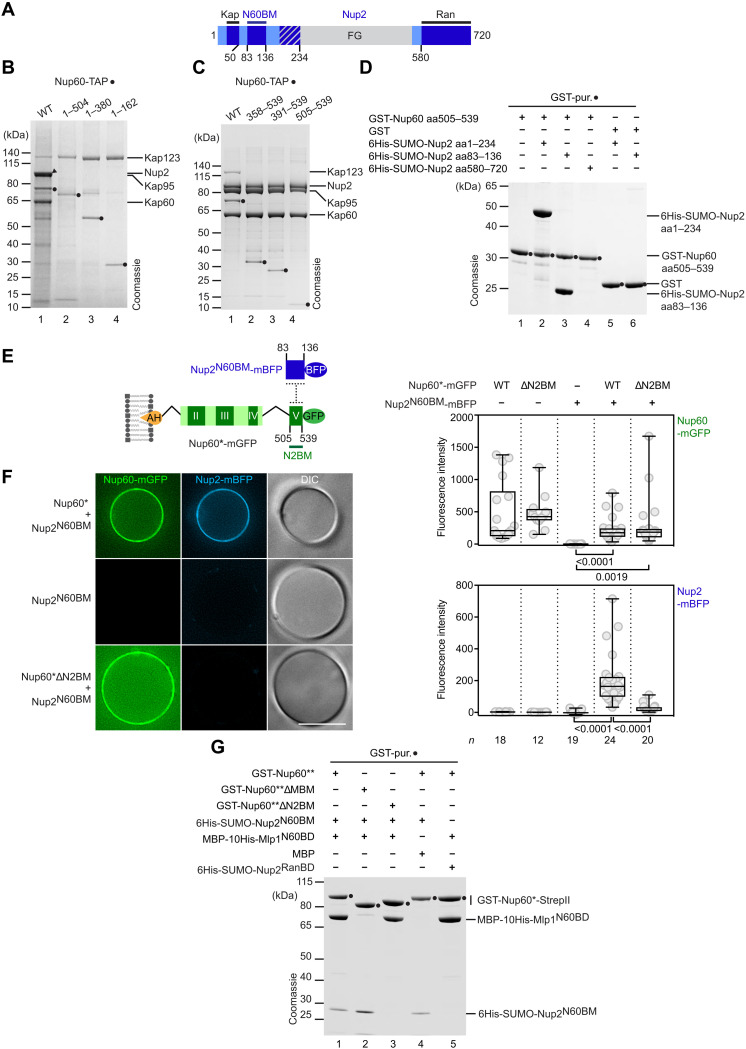

Fig. 3. Conserved SLiMs form a Nup60-Nup2 basket junction.

(A) Motif organization of Nup2. Conserved regions are labeled in dark blue, and nonconserved regions are labeled in light blue. A conserved region overlapping with FG repeats is striped. Kap, karyopherin-binding domain; N60BM, Nup60-binding motif; Ran, Ran-binding domain. (B) Tandem affinity purification of C-terminally TAP-tagged Nup60 constructs (genomically integrated). Calmodulin eluates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE/Coomassie staining and immunoblotting (see fig. S4A). Closed circles indicate bait proteins [Nup60-calmodulin-binding peptide (CBP)]. Proteins were identified by mass spectrometry. (C) Tandem affinity purification of Nup60 and N-terminal Nup60 truncations. A nup60∆ strain was transformed with plasmids carrying NUP60-TAP variants. Closed circles indicate bait proteins (Nup60-CBP). Proteins were assigned by mass spectrometry. (D) GST-Nup60N2BM aa505–539 or GST (negative control) were coexpressed with 6His-SUMO-Nup2 constructs in E. coli and subjected to GST-affinity purification. Eluates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE/Coomassie staining. See fig. S4C for immunoblotting. (E) Cartoon of the Nup60-Nup2 protein junction. These constructs were used for the GUV assay in (F). N2BM, Nup2-binding motif. BFP, blue fluorescent protein. The Nup60* construct lacks the Nup60HR and Nup60FG regions. (F) GUV-binding assay. Representative fluorescence microscopy and DIC images of GUVs were incubated with the indicated proteins. Scale bar, 10 μm. Fluorescent signals at the membrane were quantified and depicted as box-whisker plots showing median, interquartile range, minimum and maximum values, and individual data points (gray circles). Number (n) of quantified GUVs and P values from two-tailed t test are indicated. See fig. S4D for input. (G) Reconstitution of a Nup60-Mlp1-Nup2 scaffold. GST-Nup60** or GST-Nup60** deletion mutants were coexpressed with MBP-His-Mlp1N60BD or MBP (negative control) in E. coli. The respective lysates were mixed with lysates expressing His-SUMO-Nup2N60BM. A Nup60 split purification was then performed, first using the GST-tag on the N terminus and then using the StrepII-tag on the C terminus of Nup60. Eluates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE/Coomassie staining and immunoblotting (see fig. S4F).

To address this question, we purified Nup60 from yeast by using the tandem affinity purification (TAP) tag. Wild-type Nup60-TAP copurified with Nup2, Kap123, and Kap60/Kap95 (Fig. 3B, lane 1). The presence of Nup2 in the Nup60 eluate was also confirmed by immunoblotting (fig. S4A). Deletion of the previously uncharacterized, conserved motif V (aa505–539) at the Nup60 C terminus (Fig. 1A) disrupted the association of Nup60 (now aa1–504) with Nup2 (Fig. 3B, lane 2). Kap60-Kap95 were also lost upon deleting motif V, likely indirectly, because of their interaction with Nup2 (Fig. 3B, lane 2, and fig. S4A). In contrast, the interaction of Nup60 with Kap123 was retained because Kap123 binds to an NLS at the N terminus of Nup60 (see also Fig. 3B, lane 4) (50). The SLiM at the Nup60 C terminus (aa505–539), hereafter termed Nup60N2BM (Nup60 Nup2-binding motif), was sufficient to copurify Nup2 and the Nup2-interacting Kap60-Kap95 (Fig. 3C; compare lanes 1 and 4). The Nup60N2BM SLiM comprises a short predicted α helix within a disordered region (fig. S4B).

To determine which region of Nup2 binds to Nup60, we purified GST-Nup60N2BM (aa505–539) after coexpression with different Nup2 fragments in E. coli. Nup60N2BM interacted robustly with the N terminus of Nup2 (aa1–234), but not with the C-terminal Ran-binding domain (aa580–720) (Fig. 3D; compare lanes 2 and 4). A conserved SLiM of Nup2 (aa83–136), hereafter termed Nup2N60BM (Nup2 Nup60-binding motif), was sufficient for the interaction with Nup60 (Fig. 3D, lane 3, and fig. S4C). Our data are consistent with an earlier study, which identified a spatial proximity of the Nup60 C terminus with the Nup2 (aa83–136) region using cross-linking mass spectrometry (fig. S4B) (9). Moreover, the Nup2N60BM overlaps with a larger fragment of Nup2 (aa50–175) that exhibits a punctate, NPC-like staining when expressed in yeast (61). Thus, our biochemical results are in excellent agreement with these independent in vivo studies.

Last, we determined whether Nup60 (i.e., Nup60*) was able to target Nup2N60BM to the membrane using the GUV-binding assays. Nup2N60BM was recruited to GUVs in a Nup60*-dependent manner (Fig. 3, E and F, and fig. S4, D and E). In contrast, Nup60* that lacked the Nup60N2BM failed to recruit the Nup2N60BM to the GUV surface. In sum, we succeeded in reconstituting a lipid-anchored Nup60-Nup2 basket junction. This suggests that the disassembly of import complexes, a key function of Nup2, is tied to the INM via basket SLiMs. It also implies that the Nup60MBM would fasten Nup2 and its FG repeats to the Mlps via the Nup60N2BM, albeit indirectly. This loose suspension of FG repeats may create a more permeable meshwork of FG repeats on the nucleoplasmic side of the NPC, as suggested earlier (9).

Reconstitution of a minimal NPC basket scaffold on a membrane

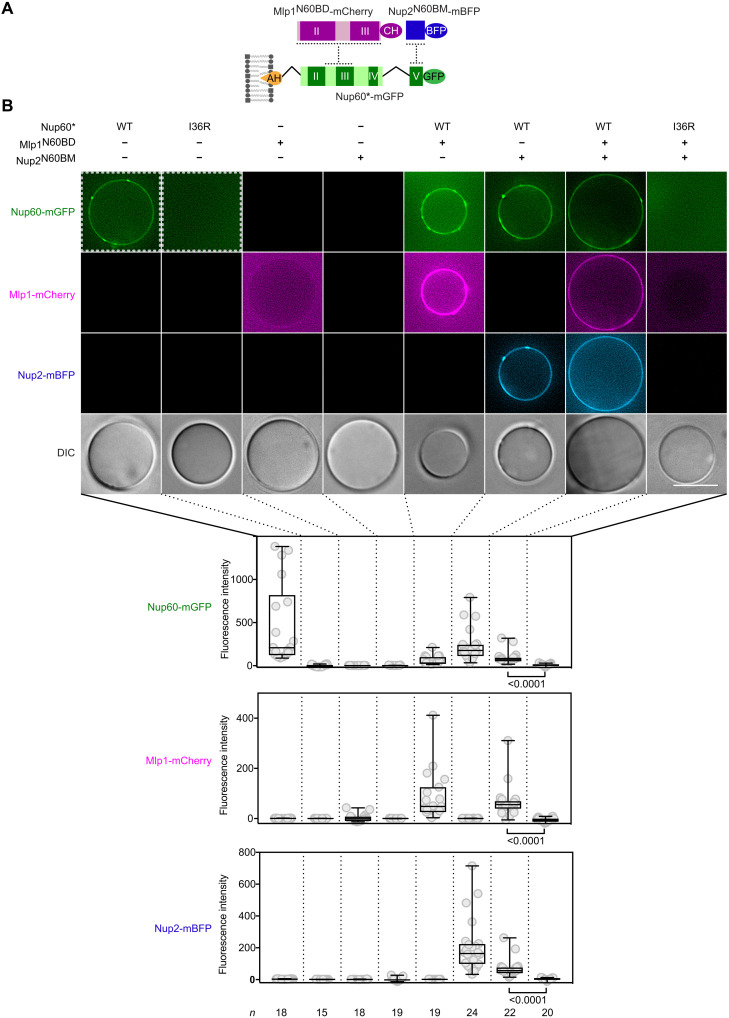

Because Nup60 binds Mlp1 and Nup2 independently via two separate SLiMs (i.e., Nup60MBM and Nup60N2BM), we determined whether a heterotrimeric NPC basket scaffold can be reconstituted. To this end, we optimized the purification of a GST-Nup60 construct (aa27–539; termed Nup60**), which only lacks the nonconserved N terminus. Immobilized recombinant GST-Nup60** interacts simultaneously with Mlp1N60BD and Nup2N60BM to form a stable heterotrimeric protein complex (Fig. 3G, lane 1). As expected, deletion of the Nup60MBM from Nup60** prevents the interaction with Mlp1, while the recruitment of Nup2 remains unaffected (Fig. 3G, lane 2). Conversely, deletion of Nup60N2BM from Nup60** prevents interaction with Nup2, while the recruitment of Mlp1 remains intact (Fig. 3G, lane 3). MBP or the Nup2 Ran-binding domain (Nup2RanBD), used as negative controls, did not interact with Nup60** (Fig. 3G and fig. S4F). Last, we tested whether a minimal Nup60-Mlp1-Nup2 basket scaffold can be assembled on GUVs. Co-incubation of Nup60*, Mlp1N60BD, and Nup2N60BM with GUVs lead to the enrichment of all proteins on the membrane surface, as judged by the signal of the respective fluorophores (Fig. 4, A and B). This assembly depended on the membrane anchor because the I36R mutation in the Nup60AH abolished the membrane recruitment of the entire complex. Consistently, neither Mlp1N60BD nor Nup2N60BM alone showed a significant recruitment to GUVs, unless Nup60* was present on the membrane. Moreover, Mlp1 and Nup2 were recruited to membrane-bound Nup60* independently of each other. Thus, we conclude that Nup60 serves as the basket’s “suspension cable,” with SLiMs connecting to lipids (Nup60AH), the NPC core (Nup60HR), Mlp1 (Nup60MBM), and Nup2 (Nup60N2BM). Nup60 served as a seed to reconstitute a minimal NPC basket scaffold on a membrane.

Fig. 4. Reconstitution of a minimal NPC basket scaffold on a membrane.

(A) Cartoon of the membrane-tethered Nup60-Mlp1-Nup2 junction. The indicated protein constructs were used for the GUV-binding assay in (B). Nup60* designates a construct that lacks the Nup60HR and Nup60FG regions. CH, mCherry. (B) Three-component GUV-binding assay. Representative fluorescence microscopy images of GUVs incubated with the indicated Nup60, Mlp1, and Nup2 constructs are shown. Scale bar, 10 μm. The fluorescent signal of the membrane was quantified and depicted as a box-whisker plot showing median, interquartile range, minimum and maximum values, and individual data points (gray circles). The number (n) of quantified GUVs and the P values from a two-tailed t test are indicated. Note that the efficiency of Nup60* recruitment to GUVs is higher without its interacting proteins. For comparison, the Nup60* and Nup60*I36R constructs (dashed squares) are shown at reduced brightness. We used Nup60* instead of Nup60** (see Fig. 3G) because the latter construct, which contains the HR and FG region, exhibited a slightly higher background binding to GUVs.

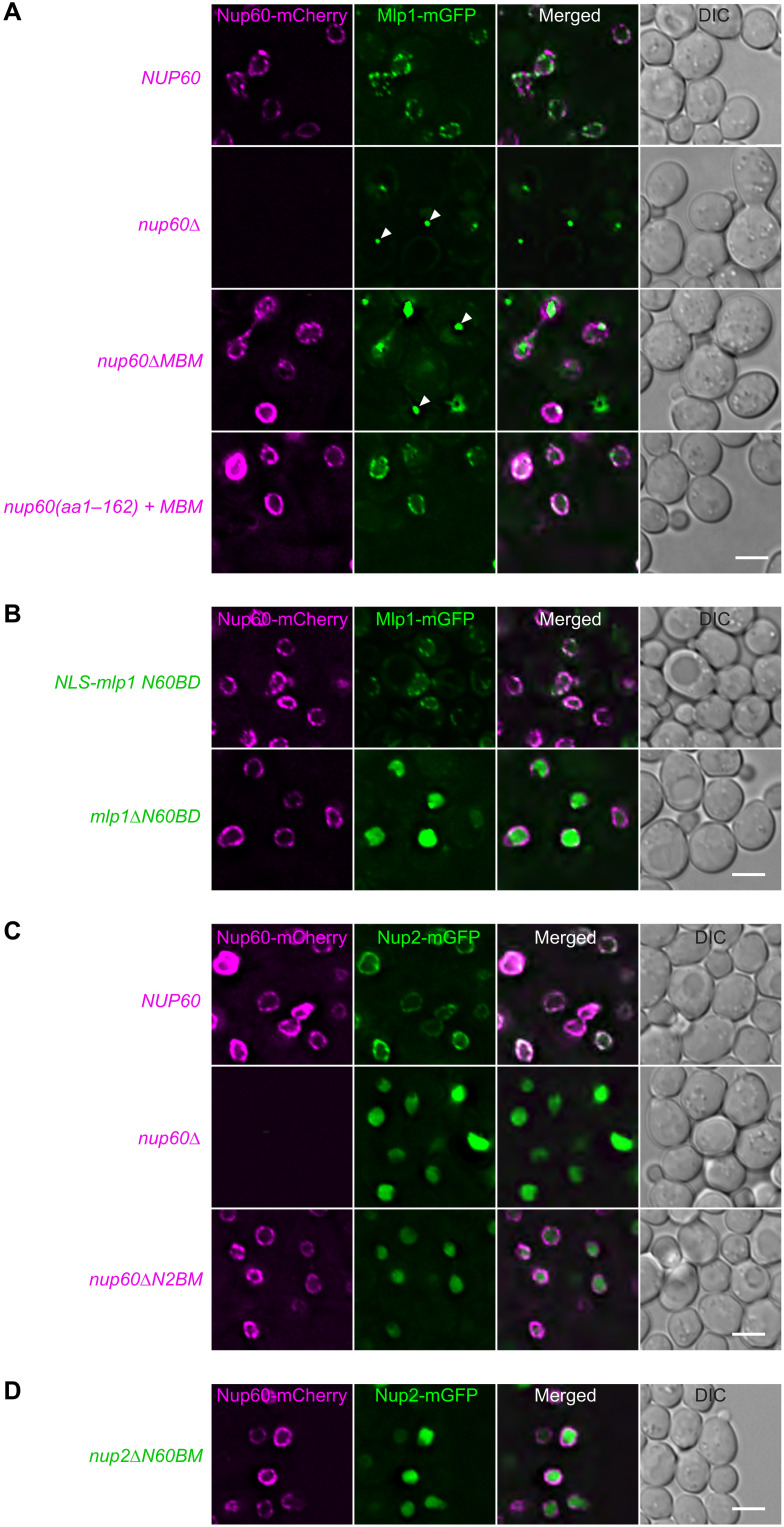

A network of SLiMs is essential for NPC basket integrity in vivo

To assess the importance of the Nup60-Mlp1-Nup2 network of SLiMs in cells, we conducted live-cell imaging experiments. Deletion of NUP60 mislocalized Mlp1-mGFP into bright fluorescent foci in the nucleus, which may represent Mlp1 aggregates (Fig. 5A) (58). Mlp1 foci formation suggests that NUP60 is required both for tethering Mlp1 to NPCs and for keeping Mlp1 in a soluble, nonaggregated state. Notably, deletion of the NUP60MBM from NUP60 also mislocalized Mlp1-GFP into foci, confirming the central role of this SLiM for proper NPC basket assembly in vivo. By contrast, deletion of the NUP60MBM did not affect the NE localization of Nup60-mCherry, which we assume remains attached to the INM via its AH and to the NPC core via the HR (see also Fig. 1A) (50). Next, we determined whether Mlp1 mislocalization could be rescued by fusing the Nup60MBM to the Nup60 N terminus (aa1–162; i.e., AH and HR), while omitting the remainder of Nup60. This Nup60 construct was sufficient to restore Mlp1 at the NE (Fig. 5A; see fig. S5 for expression levels).

Fig. 5. A network of SLiMs is essential for NPC basket integrity in vivo.

(A) Representative live-cell images of a nup60∆mlp1∆ strain cotransformed with the indicated plasmid-based NUP60-mCherry constructs (or an empty plasmid) and a wild-type MLP1-mGFP plasmid. NUP60 and MLP1 were expressed from their endogenous promoters. The nup60 aa1–162 + MBM construct is a fusion of the two NUP60 regions. White arrows label Mlp1 foci, which often appear as a single fluorescent spot in the nucleus. Scale bar, 3 μm. (B) Live-cell imaging of nup60∆mlp1∆ cells cotransformed with the indicated plasmid-based MLP1-mGFP constructs and a wild-type NUP60-mCherry plasmid. An SV40 NLS was appended to the mlp1N60BD construct to ensure its nuclear import. Scale bar, 3 μm. (C) Live-cell imaging of nup60∆nup2∆ cells cotransformed with the indicated plasmid-based NUP60-mCherry constructs (or an empty plasmid) and a wild-type NUP2-mGFP plasmid (expressed from the endogenous NUP2 promoter). Scale bar, 3 μm. (D) Live-cell imaging of nup60∆nup2∆ cells cotransformed with the indicated NUP2-mGFP construct and a wild-type NUP60-mCherry plasmid. Scale bar, 3 μm.

In a reciprocal experiment, we determined whether the Mlp1N60BD, equipped with an artificial nuclear localization sequence (SV40 large T-antigen NLS; NLS-mlp1 N60BD) to promote import, was capable of proper NPC localization. This was the case because Mlp1N60BD exhibited NPC-like fluorescent puncta at the NE (Fig. 5B, top). Mlp1 targeting to NPCs depended on the Mlp1N60BD, because deleting this SLiM mislocalized Mlp1 (Fig. 5B, bottom). When Mlp1∆N60BD became detached from NPCs, it did not form foci similar to the full-length Mlp1 in nup60∆ cells (Fig. 5A), but it exhibited a diffuse nucleoplasmic localization (Fig. 5B, bottom). Thus, the Mlp1N60BD promotes the aggregation of full-length Mlp1 in the absence of Nup60. Together, these data agree with our biochemical reconstitutions in vitro (Fig. 2) and demonstrate the in vivo significance of the Nup60-Mlp1 junction of the NPC basket.

Next, we examined the in vivo relevance of the SLiMs that form the Nup60-Nup2 junction. Deletion of the entire NUP60 mislocalized Nup2-mGFP into the nucleoplasm (Fig. 5C) (62). The detachment of Nup2 from the basket also occurred upon just deleting the NUP60N2BM from NUP60, indicating that this SLiM is the major and possibly sole tethering point of Nup2. Deleting the C-terminal NUP60N2BM did, however, not affect Nup60 localization, indicating that neither Nup2 nor the Nup60N2BM are required for proper Nup60 targeting to NPCs. Conversely, deleting the NUP2N60BM from NUP2 mislocalized Nup2-mGFP into the nucleoplasm, whereas Nup60 was properly localized (Fig. 5D). In sum, we have described an intricate network of SLiMs with Nup60 at its center that is crucial for constructing an NPC basket in cells.

DISCUSSION

We have reconstituted key interactions of the NPC basket, which allowed us to build a minimal basket scaffold on a synthetic membrane. To do so, we identified a series of SLiMs that tie the basket together. Nup60 is the basket’s suspension cable and a highly connected hub protein with at least four discrete SLiMs connecting to lipids, Mlp1, Nup2, and the NPC core. The data presented here reveal the assembly principle of the NPC basket and unite a host of earlier observations that, to this date, have not received a satisfactory biochemical explanation. Furthermore, by using the basket scaffold as a lipid-anchored seed, our study is a stepping stone toward reconstituting higher-order NPC assemblies in a membrane environment.

Basket SLiMs in disordered Nup60 regions explain basket flexibility

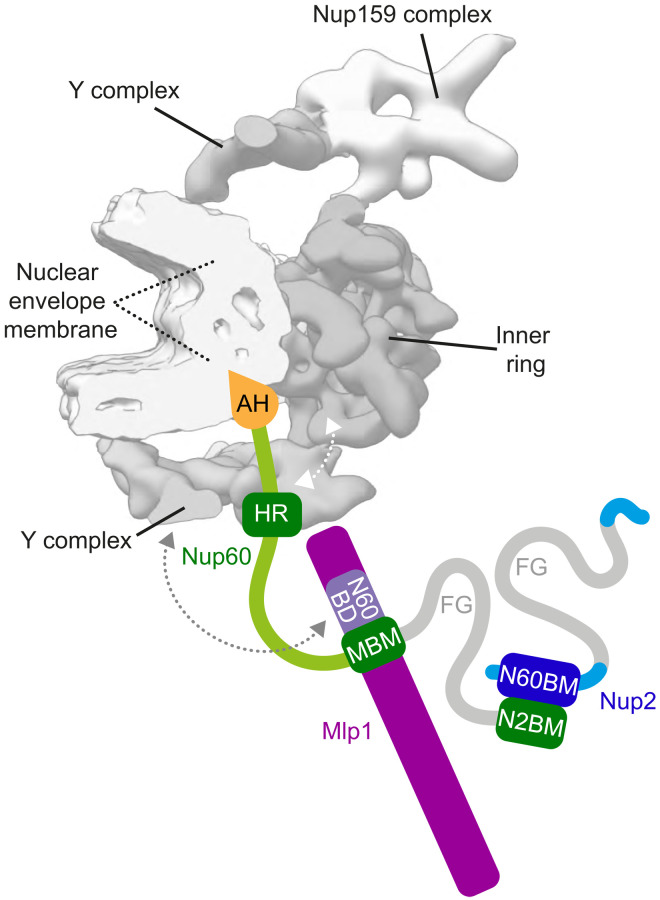

Numerous ultrastructural studies have depicted the NPC basket as a flexible structure, in which the basket filaments can be horizontally deflected in the plane of the membrane, vertically compressed or extended with respect to the transport channel, or dilated at their distal ring in response to bulky cargo (12, 25–27, 36, 38). This flexibility was seen across species and likely represents a conserved, functionally important feature, which reflects the basket’s ability to accommodate a wide range of cargo sizes and to switch its protein interactome in response to changes in gene expression (2–5). We suggest that flexibility is imparted mainly by Nup60, the basket’s intrinsically disordered suspension cable (Fig. 6): The N-terminal membrane anchor Nup60AH is expected to exhibit lateral mobility in the INM, the Nup60MBM lies within a disordered region, and so does the Nup60N2BM at the C terminus. Hence, the rod-like Mlp1/2 filaments and Nup2 are suspended on a flexible cable, which expands the basket’s conformational freedom considerably. Recent studies suggest that the Mlp filaments also associate with the Y complex. An integrative modeling approach reported that one end of the Mlp1/2 proteins interacts with the Nup85-Seh1 arm of the yeast Y complex (9), whereas an in situ cryo-ET study of the yeast NPC suggested that the Mlp1/2 filaments are attached to the vertex of the Y complex (11). These differences may reflect, in part, the flexible nature of the Mlp1/2 suspension on the NPC core. It will be interesting to see whether and how the Nup60MBM contributes to Mlp1/2 attachment to the Y complex (Fig. 6). This protein junction is likely distinct from a previously suggested interface between the Nup60HR and the Y complex, which may involve Nup84 (41, 50). Our identification of a network of basket SLiMs embedded in the mostly disordered Nup60 explains many earlier observations about the basket’s structural plasticity.

Fig. 6. Nup60 is the basket’s suspension cable connecting lipids with Mlp1, Nup2, and the NPC core.

Model of the NPC basket scaffold highlighting critical motifs and interactions between proteins and lipids. Color code of basket proteins is the same as in previous figures. An individual spoke of the circular NPC (eight spokes in total) is displayed on the basis of an in situ cryo-ET model of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae NPC (gray; cross-sectional view) (11). The FG repeat–containing transport channel is on the right side, and the highly curved NE membrane is on the left. Nup60 acts as a multifunctional organizer of the basket that (i) inserts and bends the NE membrane via its AH, (ii) interacts with the NPC core via its HR, (iii) recruits Mlp1 via its MBM, (iv) recruits Nup2 via its N2BM, and (v) tethers the FG regions onto Mlp1. The dashed gray arrow indicates the putative interaction between Mlp1 and the Y complex. The dashed white arrow refers to the putative association between the Nup60HR and the Y complex (41). Nup1 and Mlp2 were omitted for simplicity.

Basket SLiMs as a conserved construction principle of the NPC

The basket’s connectivity is based on construction principles that appear analogous to the NPC core. An emerging concept is that scaffold Nups in the NPC core are connected by a network of SLiMs, which are embedded in disordered FG Nups or in the flexible extensions that some scaffold Nups contain. For example, Nups in the thermophilic fungus Chaetomium thermophilum and their respective Saccharomyces cerevisiae homologs (ScNup53, ScNic96, and the three paralogs ScNup145N/Nup116/Nup100) harbor conserved arrays of SLiMs, which mediate interactions with several inner ring complex components through multiple, relatively weak interactions (14, 15, 21, 23). Thus, both the NPC core and the basket seem to use a combination of flexible linkers and SLiM-based contacts to make the entire structure more deformable and hence adaptable to mechanical stress. However, the basket’s various interactions with the chromatin fiber, mRNPs, and the large, multicomponent transcription machinery may necessitate an even greater degree of conformational freedom than that of the NPC core, which could explain why the Mlp proteins are suspended on the membrane through Nup60.

An important feature of SLiMs is that they are easy to biochemically make and break and hence could facilitate NPC assembly and disassembly. Notably, all Nups display uniformly slow protein turnover, yet their exchange rates (i.e., replacement of NPC-bound Nups by soluble Nups) can vary significantly (39). As a general rule, the basket Nups (Nup60, Nup2, Nup1, Mlp1, and Mlp2) are rapidly exchanging NPC proteins, and so are Nup53 (and its paralog Nup59) and Nup145N (and its paralogs Nup116/Nup100). As described above, a hallmark of Nup53 and Nup145N is the presence of arrays of SLiMs within their intrinsically disordered region (IDRs). In contrast, scaffold-forming Nups exchange slowly. Hence, the high exchange rate likely reflects the weakly adhesive properties of their SLiMs that allow rapid binding and detachment, thus ensuring that the structure can be built and recycled efficiently.

Basket SLiMs are subject to an added layer of regulation by posttranslational modifications. Nup60 is (mono-) ubiquitinated in a region of eight lysines (between K105 and K175), which overlaps with the Nup60HR (Fig. 6) (41, 50). Ubiquitination of this SLiM affects the association with the NPC core, is stimulated upon genotoxic stress, and regulates the DNA damage response and telomere repair. Nearly a quarter of SLiMs in eukaryotic proteomes are posttranslationally modified (63), and SLiM modification also pertains to the NPC core. For example, phosphorylation of the SLiM-containing region of human NUP98 (the homolog of ScNup145N/Nup116/Nup100) mediates the disassembly of the NPC core during mitosis (64). These cases are likely just the beginning of a larger array of SLiM-centered posttranslational modifications that regulate NPC plasticity.

Basket SLiMs: Implications for NPC assembly and membrane remodeling

The order of interphase NPC assembly was recently characterized by metabolic labeling/proteomics (40). Individual Nups progressed through NPC biogenesis at different rates ranging from minutes up to ~1 hour. NPC maturation began with the symmetrical core Nups and continued with the asymmetrical Nups including Nup60 and Nup2. Unexpectedly, basket assembly was only completed after ~40 min, when Mlp1 and Mlp2 became incorporated. According to this hierarchy, membrane recruitment of Nup60 via the Nup60AH and Nup2 recruitment via the Nup60N2BM could occur simultaneously. However, Mlp1 recruitment is delayed, despite the direct biochemical interaction between the Nup60MBM and Mlp1N60BD (Fig. 2G). This implies that basket SLiMs can be used sequentially rather than simultaneously, necessitating a regulation of the Nup60MBM-Mlp1N60BD junction that allows Mlp1 binding exclusively to morphologically complete NPC structures. Several phosphorylation and ubiquitination sites, which map to the Mlp1N60BD and the Nup60MBM (65, 66), will require further study.

The sequential usage of SLiMs could also be critical for inserting NPCs into the membrane during interphase assembly. This insertion proceeds asymmetrically (49). It starts with an inside-out extrusion of the INM that grows in depth and diameter until it fuses with the flat ONM. The INM-attached, “mushroom-shaped” NPC precursor undergoes a marked reorganization as it matures. It is still unclear which specific proteins localize to the “mushroom” and whether all details of the process are conserved across eukaryotes. However, binding of the Nup60AH and Nup1AH to the INM may be one of the earliest steps because they are the only known lipid-interacting Nups at the INM and incorporate early during NPC biogenesis (40). Both basket Nups are capable of membrane deformation in vitro and upon overexpression in vivo (50, 51). Moreover, the Nup60HR was shown to strongly augment the degree of membrane curvature imparted by the Nup60AH coincident with linking Nup60 to the NPC core (Fig. 6) (50). These SLiM-driven steps could, in principle, generate mechanical tension that couples force transmission on the membrane with anchorage on the maturing NPC core.

Together, we suggest that SLiMs, embedded in intrinsically disordered regions, can shape the basket’s architecture and membrane environment while, at the same time, being shaped by the various mechanical stresses that impinge on the NPC. Our visual biochemistry approach can be taken to the next level by incorporating additional lipid-interacting Nups (e.g., Nup1 and Nup53) and core scaffold Nups into the reconstitution while monitoring the membrane for dome-shaped evaginations (49) as a hallmark of early NPC biogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Recombinant protein expression and purification

All proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21 CodonPlus (DE3) RIL cells. Cells were homogenized in a French press, and proteins were purified using one-step or two-step affinity purifications (see below). All purification steps were performed at 4°C.

Purification of 6His-Nup60-mGFP-StrepII, 6His-Nup2-mTagBFP2-StrepII, and 6His-PKCβ aa31–158–mGFP-StrepII constructs

Cells were lysed in “His-purification buffer” [50 mM tris (pH 7.5), 300 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.15% CA-630 (Sigma-Aldrich)] with the Protease Inhibitor Mix HP (Serva), and the cleared lysate was incubated with a Ni Sepharose 6 Fast Flow resin (GE Healthcare). The unbound material was washed out with His-purification buffer in the Poly-Prep Chromatography Column (Bio-Rad), and proteins were eluted with a “His-elution buffer” [50 mM tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 500 mM imidazole]. The eluate was incubated with a StrepTactin Sepharose High Performance resin (GE Healthcare), unbound material was washed out on the Poly-Prep Chromatography Column (Bio-Rad) with “Strep-purification buffer” [50 mM tris (pH 7.5), 300 mM NaCl, and 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT)], and proteins were eluted with “Strep-elution buffer” [50 mM tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM DTT, and 5 mM biotin].

Purification of 6His-Mlp1-mCherry-FLAG

The first part of the purification was performed as above. The eluate from the Ni-affinity purification was incubated with an ANTI-FLAG M2 Affinity gel resin (Sigma-Aldrich), unbound material was washed out on the Mobicol F Column (MoBiTec), and proteins were eluted with “FLAG-elution buffer” [50 mM tris (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM DTT, and FLAG peptide (0.2 mg/ml)].

GST pull-down assays

Cells were lysed in “GST-purification buffer” [50 mM tris (pH 7.5), 100 or 200 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2,1 mM DTT, and 0.15% CA-630 (Sigma-Aldrich)] with the Protease Inhibitor Mix HP (Serva), and the cleared lysate was incubated with a Glutathione Sepharose 4B resin (GE Healthcare). Unbound material was washed out on the Poly-Prep Chromatography Column (Bio-Rad), and proteins were eluted with “GST-elution buffer” [50 mM Hepes (pH 8.0), 200 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM DTT, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 20 mM glutathione].

Purification of MBP-10His-Mlp1 aa382–620

Protein was purified using a (single-step) Ni-affinity purification and eluted with a His-elution buffer as indicated above.

Reconstitution of a minimal Nup60-Mlp1-Nup2 complex

A cleared lysate of cells coexpressing GST-Nup60**-StrepII variants and MBP-10His-Mlp1 (or MBP-10His alone) was mixed with a cleared lysate of cells expressing 6His-SUMO-Nup2 variants and was then subjected to GST purification (performed as above) followed by a Strep-affinity purification and elution with 2.5 mM desthiobiotin.

Purification of NusA-6His-Mlp1 aa382–620

The protein was purified on an ÄKTA Purifier fast protein liquid chromatography system (GE Healthcare). Cells were lysed in a buffer containing 50 mM tris (pH 7.5), 300 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphin (TCEP), 50 mM imidazole, and 0.15% CA-630 (Sigma-Aldrich) with the Protease Inhibitor Mix HP (Serva), and a cleared lysate was injected into a pre-equilibrated HiTrap HP 5-ml column (Cytiva) with the lysis buffer without CA-630. The unbound material was washed out with the same buffer, and the protein was eluted into a buffer containing 50 mM tris (pH 7.5), 300 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM TCEP, and 500 mM imidazole. The eluate was diluted to adjust the NaCl concentration to 100 mM and submit to ion exchange chromatography on a MonoQ 5/15GL (Cytiva), equilibrated with 50 mM tris (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM TCEP. The unbound sample was washed with the same buffer, and the protein was eluted in a NaCl gradient from 100 to 500 mM NaCl. The sample elutes as a single peak. The corresponding fractions were pooled together, concentrated, and submitted to SEC on Superose 6 10/300 (Cytiva) equilibrated with 50 mM tris (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.5 mM DTT.

Reconstitution of a Mlp1N60BD-Nup60MBM complex and analytical SEC

Purified NusA-6His-Mlp1N60BD and GST-Nup60MBM proteins were mixed in 50 mM tris (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, and 1.5 mM MgCl2 in a molar ratio of 1:2 (21 μM Mlp1N60BD:42 μM Nup60MBM). The mixture was incubated for 45 min on ice before running it on a Superose 6 Increase 3.2/300 column (Cytiva). Fractions (0.1 ml) were collected for analysis on SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

Tandem affinity purification

Yeast cells were grown in yeast-extract peptone dextrose (YPD) media (genomically integrated TAP tag; Fig. 3B and fig. S4A) or in synthetic dextrose complete (SDC)–Leu media (plasmid-based expression; Fig. 3C). TAPs were performed according to Rigaut et al. (67).

Preparation of GUVs

The lipids POPE, POPS, POPC, brain PIP2, and DAG (1-2-dioleoyl-sn-glycerol) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids. GUVs were synthesized by polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)–assisted swelling (68). Ten microliters of 4% PVA (weight-average molecular weight of 146,000 to 186,000; Sigma-Aldrich) in 280 mM sucrose were spread on a glass coverslip and dried at 60°C for 30 min. Ten microliters of lipid mixture [46.3 mol % of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoylsn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (POPE), 28.9 mol % of sodium salt of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine (POPS), 18.9 mol % of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC), 4.9 mol % of ammonium salt of l-a-phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), and 1.0 mol % of diacylglycerol (DAG)] at 1 mg/ml in chloroform was spread on top of the PVA layer and desiccated for 45 min. A total of 500 μl of swelling buffer [280 mM sucrose and 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.4)] was added on the coverslip and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature (RT) to induce vesicle formation. Vesicles were harvested by pipetting and kept at RT for immediate use.

Preparation of GUV samples for microscopy

Vesicles were imaged in the 16-well plates (glass bottom; Grace Bio-Labs). Wells were blocked for 1 hour with coating buffer [50 mM tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, and bovine serum albumin (2.5 mg/ml)]. Samples were premixed in a test tube by adding the reaction buffer, GUV solution, and protein solution (in this order). A reaction buffer [50 mM tris (pH 7.5) and 200 mM NaCl/250 mM NaCl for series including Mlp1] was added to a total volume of 60 μl, followed by 7.5 μl of GUV solution and a protein (final concentration of 100 nM). In multiprotein samples, proteins were premixed, incubated for 1 min, and added to the reaction to yield a 100 nM concentration of each protein. Coated wells were washed with reaction buffer before loading the samples. After an incubation time of 10 min (RT), GUVs were imaged for another 10 min.

Visualization of GUVs

GUVs were imaged at RT on a DeltaVision Elite microscope (GE Healthcare). Images were acquired with 60× oil immersion objective and recorded with a CoolSNAPHQ2 charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (Photometrics). GUVs were manually selected using the DIC channel, and nonspherical or clustered vesicles were excluded.

Quantification of protein signal on the GUVs

Images were deconvolved using softWoRx software (GE Healthcare). All following steps were performed in ImageJ (version 1.51j8, National Institutes of Health). For each GUV with a diameter of dGUV, two concentric circles were drawn: an outer circle with a diameter of douter = dGUV + t and an inner circle with a diameter of dinner = dGUV − t. The membrane thickness (t) was empirically determined for our microscope setup using GUVs labeled with a fluorescent lipid. A third circle was drawn next to the GUV for background subtraction. For all three circles, total fluorescence intensity (FIouter, FIinner, and Flbackground) and area (Aouter, Ainner, and Abackground) were measured. The total fluorescence intensity per area of a GUV was calculated as follows

This step was repeated for each channel. The data were further analyzed in GraphPad Prism 7. Statistical significance was assessed by a two-tailed t test. P values and sample sizes are indicated in the figures.

Live-cell imaging of yeast

Exponentially growing cells were immobilized on microscope slides with agarose pads and imaged on a DeltaVision Elite microscope (GE Healthcare). Images were acquired with a 60× oil immersion objective and recorded with a CoolSNAPHQ2 CCD camera (Photometrics). Deconvolution was carried out using softWoRx software (GE Healthcare).

Construction of yeast strains

Genes in yeast were tagged or deleted by a standard one-step polymerase chain reaction–based technique. Microbiological techniques followed standard procedures. Cells were grown in YPD or, when transformed with plasmids, in selective SDC drop-out medium.

Plasmids

| Name | Description | Reference |

| MalpET | MBP-10His-TEV vector | (69) |

| MalpET-Mlp1 aa382–620 | Mlp1N60BD | This study |

| pET28a-His-TEV | 10His-TEV vector | Novagen (modified) |

| pET28a-His-TEV-Mlp1 aa382–620–mCherry-FLAG | Mlp1N60BD-mCherry | This study |

| pET-6His-SUMO | 6His-SUMO vector | Invitrogen (modified) |

| pET-6His-SUMO-Nup2 aa1–234 | Nup21–234 | |

| pET-6His-SUMO-Nup2 aa83–136 | Nup2N60BM | This study |

| pET-6His-SUMO-Nup2 aa83–136–TagmBFPII-StrepII | Nup2N60BM | This study |

| pET-6His-SUMO-Nup2 aa580–720 | Nup2RanBD | This study |

| pGEX-GST-TEV | GST vector | Amersham (modified) |

| pGEX-GST-TEV-Nup60 aa27–539–StrepII | Nup60** | This study |

| pGEX-GST-TEV-Nup60 aa27–539Δaa240–318–StrepII | Nup60**ΔMBM | This study |

| pGEX-GST-TEV-Nup60 aa27–539 Δaa505–539–StrepII | Nup60**ΔN2BM | This study |

| pGEX-GST-TEV-Nup60 aa505–539 | Nup60N2BM | This study |

| pGEX-GST-TEV-Nup60 aa240–318 | Nup60MBM | This study |

| pPROEX-HTB | 6His-TEV vector | Invitrogen |

| pPROEX-HTB-6His-Nup60 aa27–47–mGFP-StrepII | Nup60AH | This study |

| pPROEX-HTB-6His-Nup60 aa27–47(I36R)–mGFP-StrepII | Nup60AH I36R | This study |

| pPROEX-HTB-6His-Nup60 aa27–539ΔHRΔFG-mGFP-StrepII | Nup60* | This study |

| pPROEX-HTB-6His-Nup60 aa27–539ΔHRΔFG(I36R)–mGFP-StrepII | Nup60* I36R | This study |

| pPROEX-HTB-6His-Nup60 aa27–539ΔHRΔMBMΔFG-mGFP-StrepII | Nup60* ΔMBM | This study |

| pPROEX-HTB-6His-Nup60 aa27–539ΔHRΔFGΔN2BM-mGFP-StrepII | Nup60* ΔN2BM | This study |

| pROEX-HTB-6His-PKCβ aa31–158–mGFP-StrepII | PKCβ C1aC1b | This study |

| pETM-60 | NusA-6His-TEV | (70) |

| pETM-60-NusA-6His-Mlp1 aa382–620 | Mlp1N60BD | This study |

| pETM-60-NusA-6His-Mlp1 aa382–517 | Mlp1382–517 | This study |

| pETM-60-NusA-6His-Mlp1 aa518–620 | Mlp1518–620 | This study |

| pRS315 | Yeast expression vector | (71) |

| pRS315-Mlp1promoter-SV40NLS-Mlp1 aa382–620–mGFP | NLS-Mlp1N60BD | This study |

| pRS315-Nup60prom-Nup60-TAP | Nup60-TAP | This study |

| pRS315-Nup60prom-Nup60 aa385–539–TAP | Nup60385–539-TAP | This study |

| pRS315-Nup60prom-Nup60 aa391–539–TAP | Nup60391–539-TAP | This study |

| pRS315-Nup60prom-Nup60 aa505–539–TAP | Nup60505–539-TAP | This study |

| pRS315-Nup60prom-Nup60-mCherry | Nup60-mCherry | This study |

| pRS315-Nup60prom-Nup60 aa1–504–mCherry | Nup601–504-mCherry | This study |

| pRS315-Nup60prom-Nup60 aa1–318–mCherry | Nup601–318-mCherry | This study |

| pRS315-Nup60prom-Nup60 aa1–239–mCherry | Nup601–239-mCherry | This study |

| pRS315-Nup60 prom-Nup60 Δaa505–539– mCherry | Nup60ΔN2BM-mCherry | This study |

| pRS316 | Yeast expression vector | (71) |

| pRS316-Nup2prom-Nup2-mGFP | Nup2-mGFP | This study |

| pRS316-Nup2prom-Nup2 Δaa83–136–mGFP | Nup2 ΔN60BM-mGFP | This study |

| pRS316-Nup60 prom-Nup60-mCherry | Nup60-mCherry | This study |

| pRS316-Nup60prom-Nup60ΔMBM-mCherry | Nup60 ΔMBM-mCherry | This study |

| pRS316-Nup60prom-Nup60 aa1–162 + aa240–318–mCherry | Nup60 aa1–162 + MBM-mCherry | This study |

Yeast strains

| Name | Genotype | Reference |

| BY4741 | Mat a; his3D1; leu2D0; met15D0; ura3D0; | Euroscarf |

| nup60Δ mlp1Δ |

Mat a; his3D1; leu2D0; met15D0; ura3D0;nup60Δ::kanMX4 mlp1Δ::natNT2 |

This study |

| nup60Δ nup2Δ |

Mat a; his3D1; leu2D0; met15D0; ura3D0; nup60Δ::kanMX4 nup2Δ::natNT2 |

This study |

| NUP60-TAP MLP1-MYC |

Mat a; his3D1; leu2D0; met15D0; ura3D0; NUP60-TAP::natNT2 MLP1-MYC::hisMX6 |

This study |

| nup60aa1–504-TAP MLP1-MYC |

Mat a; his3D1; leu2D0; met15D0; ura3D0;nup60 aa1–504-TAP::natNT2 MLP1-MYC::hisMX6 |

This study |

| nup60aa1–380-TAP MLP1-MYC |

Mat a; his3D1; leu2D0; met15D0; ura3D0;nup60 aa1–380-TAP::natNT2 MLP1-MYC::hisMX6 |

This study |

| nup60aa1–162-TAP MLP1-MYC |

Mat a; his3D1; leu2D0; met15D0; ura3D0;nup60 aa1–162-TAP::natNT2 MLP1-MYC::hisMX6 |

This study |

| NUP60-TAP NUP2-MYC MLP1-GFP |

Mat a; his3D1; leu2D0; met15D0; ura3D0;NUP60-TAP::natNT2 NUP2-MYC::kanMX4 MLP1-GFP::hisMX6 |

This study |

| nup60aa1–504-TAP NUP2-MYC MLP1-GFP |

Mat a; his3D1; leu2D0; met15D0; ura3D0;nup60aa1–504-TAP::natNT2 NUP2-MYC::kanMX4 MLP1-GFP::hisMX6 |

This study |

| nup60aa1–380-TAP NUP2-MYC MLP1-GFP |

Mat a; his3D1; leu2D0; met15D0; ura3D0;nup60aa1–380-TAP::natNT2 NUP2-MYC::kanMX4 MLP1-GFP::hisMX6 |

This study |

| nup60aa1–318-TAP NUP2-MYC MLP1-GFP |

Mat a; his3D1; leu2D0; met15D0; ura3D0;nup60aa1–318-TAP::natNT2 NUP2-MYC::kanMX4 MLP1-GFP::hisMX6 |

This study |

| nup60aa1–239-TAP NUP2-MYC MLP1-GFP |

Mat a; his3D1; leu2D0; met15D0; ura3D0;nup60aa1–239-TAP::natNT2 NUP2-MYC::kanMX4 MLP1-GFP::hisMX6 |

This study |

| nup60aa1–162-TAP NUP2-MYC MLP1-GFP |

Mat a; his3D1; leu2D0; met15D0; ura3D0;nup60aa1–162-TAP::natNT2 NUP2-MYC::kanMX4 MLP1-GFP::hisMX6 |

This study |

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Martens and T. Leonard for valuable discussions, E. Stankunas and T. Clausen for comments on the manuscript, and A. Romanauska for technical advice.

Funding: This study was funded by an ERC-COG grant (772032; NPC BUILD). A.K. is a recipient of a NOMIS Pioneering Research Grant. J.C. was funded by an OeAW DOC Fellowship. K.R. was funded by the doctoral program RNA biology W1207 of the Austrian Science Foundation.

Author contributions: J.C. performed biochemical mapping of the basket SLiMs and reconstitution of the minimal Nup60-Mlp1-Nup2 scaffold. R.M.G.C. performed SEC experiments. J.C. designed and purified protein fragments for GUV experiments. F.B. optimized GUV preparations, GUV-binding assays, imaging, and quantification. F.B., J.C., and K.R. performed GUV experiments. The live-cell miscroscopy was done by K.R. and J.C. A.K. supervised the project and wrote the manuscript with input from J.C.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions of the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S5

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Ungricht R., Kutay U., Mechanisms and functions of nuclear envelope remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 229–245 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iglesias N., Paulo J. A., Tatarakis A., Wang X., Edwards A. L., Bhanu N. V., Garcia B. A., Haas W., Gygi S. P., Moazed D., Native chromatin proteomics reveals a role for specific nucleoporins in heterochromatin organization and maintenance. Mol. Cell 77, 51–66.e8 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pascual-Garcia P., Capelson M., The nuclear pore complex and the genome: Organizing and regulatory principles. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 67, 142–150 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raices M., D’Angelo M. A., Nuclear pore complexes and regulation of gene expression. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 46, 26–32 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneider M., Hellerschmied D., Schubert T., Amlacher S., Vinayachandran V., Reja R., Pugh B. F., Clausen T., Köhler A., The nuclear pore-associated TREX-2 complex employs mediator to regulate gene expression. Cell 162, 1016–1028 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho U. H., Hetzer M. W., Nuclear periphery takes center stage: The role of nuclear pore complexes in cell identity and aging. Neuron 106, 899–911 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakuma S., D’Angelo M. A., The roles of the nuclear pore complex in cellular dysfunction, aging and disease. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 68, 72–84 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hampoelz B., Andres-Pons A., Kastritis P., Beck M., Structure and assembly of the nuclear pore complex. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 48, 515–536 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim S. J., Fernandez-Martinez J., Nudelman I., Shi Y., Zhang W., Raveh B., Herricks T., Slaughter B. D., Hogan J. A., Upla P., Chemmama I. E., Pellarin R., Echeverria I., Shivaraju M., Chaudhury A. S., Wang J., Williams R., Unruh J. R., Greenberg C. H., Jacobs E. Y., Yu Z., de la Cruz M. J., Mironska R., Stokes D. L., Aitchison J. D., Jarrold M. F., Gerton J. L., Ludtke S. J., Akey C. W., Chait B. T., Sali A., Rout M. P., Integrative structure and functional anatomy of a nuclear pore complex. Nature 555, 475–482 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin D. H., Hoelz A., The structure of the nuclear pore complex (an update). Annu. Rev. Biochem. 88, 725–783 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allegretti M., Zimmerli C. E., Rantos V., Wilfling F., Ronchi P., Fung H. K. H., Lee C.-W., Hagen W., Turoňová B., Karius K., Börmel M., Zhang X., Müller C. W., Schwab Y., Mahamid J., Pfander B., Kosinski J., Beck M., In-cell architecture of the nuclear pore and snapshots of its turnover. Nature 586, 796–800 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck M., Förster F., Ecke M., Plitzko J. M., Melchior F., Gerisch G., Baumeister W., Medalia O., Nuclear pore complex structure and dynamics revealed by cryoelectron tomography. Science 306, 1387–1390 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eibauer M., Pellanda M., Turgay Y., Dubrovsky A., Wild A., Medalia O., Structure and gating of the nuclear pore complex. Nat. Commun. 6, 7532 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kosinski J., Mosalaganti S., von Appen A., Teimer R., DiGuilio A. L., Wan W., Bui K. H., Hagen W. J. H., Briggs J. A. G., Glavy J. S., Hurt E., Beck M., Molecular architecture of the inner ring scaffold of the human nuclear pore complex. Science 352, 363–365 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin D. H., Stuwe T., Schilbach S., Rundlet E. J., Perriches T., Mobbs G., Fan Y., Thierbach K., Huber F. M., Collins L. N., Davenport A. M., Jeon Y. E., Hoelz A., Architecture of the symmetric core of the nuclear pore. Science 352, aaf1015 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Appen A., Kosinski J., Sparks L., Ori A., DiGuilio A. L., Vollmer B., Mackmull M.-T., Banterle N., Parca L., Kastritis P., Buczak K., Mosalaganti S., Hagen W., Andres-Pons A., Lemke E. A., Bork P., Antonin W., Glavy J. S., Bui K. H., Beck M., In situ structural analysis of the human nuclear pore complex. Nature 526, 140–143 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szymborska A., de Marco A., Daigle N., Cordes V. C., Briggs J. A. G., Ellenberg J., Nuclear pore scaffold structure analyzed by super-resolution microscopy and particle averaging. Science 341, 655–658 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelley K., Knockenhauer K. E., Kabachinski G., Schwartz T. U., Atomic structure of the Y complex of the nuclear pore. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 22, 425–431 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nordeen S. A., Turman D. L., Schwartz T. U., Yeast Nup84-Nup133 complex structure details flexibility and reveals conservation of the membrane anchoring ALPS motif. Nat. Commun. 11, 6060 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Roey K., Uyar B., Weatheritt R. J., Dinkel H., Seiler M., Budd A., Gibson T. J., Davey N. E., Short linear motifs: Ubiquitous and functionally diverse protein interaction modules directing cell regulation. Chem. Rev. 114, 6733–6778 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amlacher S., Sarges P., Flemming D., van Noort V., Kunze R., Devos D. P., Arumugam M., Bork P., Hurt E., Insight into structure and assembly of the nuclear pore complex by utilizing the genome of a eukaryotic thermophile. Cell 146, 277–289 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eisenhardt N., Redolfi J., Antonin W., Interaction of Nup53 with Ndc1 and Nup155 is required for nuclear pore complex assembly. J. Cell Sci. 127, 908–921 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischer J., Teimer R., Amlacher S., Kunze R., Hurt E., Linker Nups connect the nuclear pore complex inner ring with the outer ring and transport channel. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 22, 774–781 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teimer R., Kosinski J., von Appen A., Beck M., Hurt E., A short linear motif in scaffold Nup145C connects Y-complex with pre-assembled outer ring Nup82 complex. Nat. Commun. 8, 1107 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldberg M. W., Allen T. D., The nuclear pore complex: Three-dimensional surface structure revealed by field emission, in-lens scanning electron microscopy, with underlying structure uncovered by proteolysis. J. Cell Sci. 106, 261–274 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jarnik M., Aebi U., Toward a more complete 3-D structure of the nuclear-pore complex. J. Struct. Biol. 107, 291–308 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ris H., Malecki M., High-resolution field emission scanning electron microscope imaging of internal cell structures after epon extraction from sections: A new approach to correlative ultrastructural and immunocytochemical studies. J. Struct. Biol. 111, 148–157 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krull S., Dörries J., Boysen B., Reidenbach S., Magnius L., Norder H., Thyberg J., Cordes V. C., Protein Tpr is required for establishing nuclear pore-associated zones of heterochromatin exclusion. EMBO J. 29, 1659–1673 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niepel M., Molloy K. R., Williams R., Farr J. C., Meinema A. C., Vecchietti N., Cristea I. M., Chait B. T., Rout M. P., Strambio-de-Castillia C., The nuclear basket proteins Mlp1p and Mlp2p are part of a dynamic interactome including Esc1p and the proteasome. Mol. Biol. Cell 24, 3920–3938 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niepel M., Strambio-de-Castillia C., Fasolo J., Chait B. T., Rout M. P., The nuclear pore complex-associated protein, Mlp2p, binds to the yeast spindle pole body and promotes its efficient assembly. J. Cell Biol. 170, 225–235 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saroufim M. A., Bensidoun P., Raymond P., Rahman S., Krause M. R., Oeffinger M., Zenklusen D., The nuclear basket mediates perinuclear mRNA scanning in budding yeast. J. Cell Biol. 211, 1131–1140 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galy V., Gadal O., Fromont-Racine M., Romano A., Jacquier A., Nehrbass U., Nuclear retention of unspliced mRNAs in yeast is mediated by perinuclear Mlp1. Cell 116, 63–73 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Albert S., Schaffer M., Beck F., Mosalaganti S., Asano S., Thomas H. F., Plitzko J. M., Beck M., Baumeister W., Engel B. D., Proteasomes tether to two distinct sites at the nuclear pore complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 13726–13731 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lemke E. A., The multiple faces of disordered nucleoporins. J. Mol. Biol. 428, 2011–2024 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmidt H. B., Gorlich D., Transport selectivity of nuclear pores, phase separation, and membraneless organelles. Trends Biochem. Sci. 41, 46–61 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kiseleva E., Allen T. D., Rutherford S., Bucci M., Wente S. R., Goldberg M. W., Yeast nuclear pore complexes have a cytoplasmic ring and internal filaments. J. Struct. Biol. 145, 272–288 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fahrenkrog B., Hurt E. C., Aebi U., Pante N., Molecular architecture of the yeast nuclear pore complex: Localization of Nsp1p subcomplexes. J. Cell Biol. 143, 577–588 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kiseleva E., Goldberg M. W., Daneholt B., Allen T. D., RNP export is mediated by structural reorganization of the nuclear pore basket. J. Mol. Biol. 260, 304–311 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hakhverdyan Z., Molloy K. R., Keegan S., Herricks T., Lepore D. M., Munson M., Subbotin R. I., Fenyö D., Aitchison J. D., Fernandez-Martinez J., Chait B. T., Rout M. P., Dissecting the structural dynamics of the nuclear pore complex. Mol. Cell 81, 153–165.e7 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Onischenko E., Noor E., Fischer J. S., Gillet L., Wojtynek M., Vallotton P., Weis K., Maturation kinetics of a multiprotein complex revealed by metabolic labeling. Cell 183, 1785–1800.e26 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niño C. A., Guet D., Gay A., Brutus S., Jourquin F., Mendiratta S., Salamero J., Géli V., Dargemont C., Posttranslational marks control architectural and functional plasticity of the nuclear pore complex basket. J. Cell Biol. 212, 167–180 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mi L., Goryaynov A., Lindquist A., Rexach M., Yang W. D., Quantifying nucleoporin stoichiometry inside single nuclear pore complexes in vivo. Sci. Rep. 5, 9372 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rajoo S., Vallotton P., Onischenko E., Weis K., Stoichiometry and compositional plasticity of the yeast nuclear pore complex revealed by quantitative fluorescence microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E3969–E3977 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fahrenkrog B., Maco B., Fager A. M., Köser J., Sauder U., Ullman K. S., Aebi U., Domain-specific antibodies reveal multiple-site topology of Nup153 within the nuclear pore complex. J. Struct. Biol. 140, 254–267 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krull S., Thyberg J., Bjorkroth B., Rackwitz H. R., Cordes V. C., Nucleoporins as components of the nuclear pore complex core structure and Tpr as the architectural element of the nuclear basket. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 4261–4277 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strambio-de-Castillia C., Blobel G., Rout M. P., Proteins connecting the nuclear pore complex with the nuclear interior. J. Cell Biol. 144, 839–855 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rout M. P., Aitchison J. D., Suprapto A., Hjertaas K., Zhao Y., Chait B. T., The yeast nuclear pore complex: Composition, architecture, and transport mechanism. J. Cell Biol. 148, 635–652 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De Magistris P., Antonin W., The dynamic nature of the nuclear envelope. Curr. Biol. 28, R487–R497 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Otsuka S., Bui K. H., Schorb M., Hossain M. J., Politi A. Z., Koch B., Eltsov M., Beck M., Ellenberg J., Nuclear pore assembly proceeds by an inside-out extrusion of the nuclear envelope. eLife 5, e19071 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meszaros N., Cibulka J., Mendiburo M. J., Romanauska A., Schneider M., Köhler A., Nuclear pore basket proteins are tethered to the nuclear envelope and can regulate membrane curvature. Dev. Cell 33, 285–298 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vollmer B., Lorenz M., Moreno-Andrés D., Bodenhöfer M., de Magistris P., Astrinidis S. A., Schooley A., Flötenmeyer M., Leptihn S., Antonin W., Nup153 recruits the Nup107-160 complex to the inner nuclear membrane for interphasic nuclear pore complex assembly. Dev. Cell 33, 717–728 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Doucet C. M., Talamas J. A., Hetzer M. W., Cell cycle-dependent differences in nuclear pore complex assembly in metazoa. Cell 141, 1030–1041 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Drin G., Casella J.-F., Gautier R., Boehmer T., Schwartz T. U., Antonny B., A general amphipathic α-helical motif for sensing membrane curvature. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 138–146 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marelli M., Lusk C. P., Chan H., Aitchison J. D., Wozniak R. W., A link between the synthesis of nucleoporins and the biogenesis of the nuclear envelope. J. Cell Biol. 153, 709–724 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vollmer B., Schooley A., Sachdev R., Eisenhardt N., Schneider A. M., Sieverding C., Madlung J., Gerken U., Macek B., Antonin W., Dimerization and direct membrane interaction of Nup53 contribute to nuclear pore complex assembly. EMBO J. 31, 4072–4084 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Romanauska A., Köhler A., The inner nuclear membrane is a metabolically active territory that generates nuclear lipid droplets. Cell 174, 700–715.e18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vanni S., Hirose H., Barelli H., Antonny B., Gautier R., A sub-nanometre view of how membrane curvature and composition modulate lipid packing and protein recruitment. Nat. Commun. 5, 4916 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Feuerbach F., Galy V., Trelles-Sticken E., Fromont-Racine M., Jacquier A., Gilson E., Olivo-Marin J.-C., Scherthan H., Nehrbass U., Nuclear architecture and spatial positioning help establish transcriptional states of telomeres in yeast. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 214–221 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stewart M., Molecular mechanism of the nuclear protein import cycle. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Bio. 8, 195–208 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Denning D., Mykytka B., Allen N. P. C., Huang L., Burlingame A., Rexach M., The nucleoporin Nup60p functions as a Gsp1p-GTP-sensitive tether for Nup2p at the nuclear pore complex. J. Cell Biol. 154, 937–950 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chu D. B., Gromova T., Newman T. A. C., Burgess S. M., The nucleoporin Nup2 contains a meiotic-autonomous region that promotes the dynamic chromosome events of meiosis. Genetics 206, 1319–1337 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dilworth D. J., Suprapto A., Padovan J. C., Chait B. T., Wozniak R. W., Rout M. P., Aitchison J. D., Nup2p dynamically associates with the distal regions of the yeast nuclear pore complex. J. Cell Biol. 153, 1465–1478 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kumar M., Gouw M., Michael S., Sámano-Sánchez H., Pancsa R., Glavina J., Diakogianni A., Valverde J. A., Bukirova D., Čalyševa J., Palopoli N., Davey N. E., Chemes L. B., Gibson T. J., ELM—The eukaryotic linear motif resource in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D296–D306 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Laurell E., Beck K., Krupina K., Theerthagiri G., Bodenmiller B., Horvath P., Aebersold R., Antonin W., Kutay U., Phosphorylation of Nup98 by multiple kinases is crucial for NPC disassembly during mitotic entry. Cell 144, 539–550 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lanz M. C., Yugandhar K., Gupta S., Sanford E. J., Faça V. M., Vega S., Joiner A. M. N., Fromme J. C., Yu H., Smolka M. B., In-depth and 3-dimensional exploration of the budding yeast phosphoproteome. EMBO Rep. 22, e51121 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Swaney D. L., Beltrao P., Starita L., Guo A., Rush J., Fields S., Krogan N. J., Villén J., Global analysis of phosphorylation and ubiquitylation cross-talk in protein degradation. Nat. Methods 10, 676–682 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rigaut G., Shevchenko A., Rutz B., Wilm M., Mann M., Séraphin B., A generic protein purification method for protein complex characterization and proteome exploration. Nat. Biotechnol. 17, 1030–1032 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weinberger A., Tsai F.-C., Koenderink G. H., Schmidt T. F., Itri R., Meier W., Schmatko T., Schröder A., Marques C., Gel-assisted formation of giant unilamellar vesicles. Biophys. J. 105, 154–164 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vidilaseris K., Dong G., Expression, purification and preliminary crystallographic analysis of the N-terminal domain of Trypanosoma brucei BILBO1. Acta Cryst. 70, 628–631 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.De Marco V., Stier G., Blandin S., de Marco A., The solubility and stability of recombinant proteins are increased by their fusion to NusA. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 322, 766–771 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sikorski R. S., Hieter P., A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122, 19–27 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figs. S1 to S5