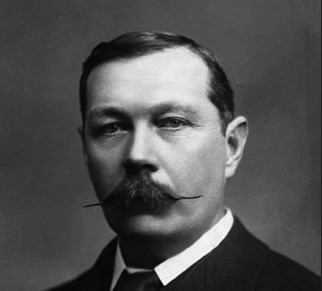

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930)

“The world is full of obvious things which nobody by any chance ever observes.” – Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The Hound of Baskervilles

Ever wondered how the pair of glasses found next to a murder victim led to the identification of the suspect’s facial appearance, sex and gait? Well, it’s quite elementary if you are either Sherlock Holmes or his brain, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. The pair of glasses in The Adventures of the Golden Prince-Nez was more than a piece of clue. It was a subtle reference to the former profession of one of the most famous authors- an ophthalmologist practising in London. December marks the month when Sherlock Holmes and Dr James Watson were first introduced in A Study in Scarlet published in Beeton Christmas Annual, 1887 and 2021, the 120th year of The Hound of the Baskervilles. This month’s Tale of Yore is a reminiscence of the ophthalmologist who created the epitome of observational skills.

Arthur Conan Doyle was born at Picardy Place, Edinburgh on May 22, 1859. He was the son of Charles Atamonte Doyle, a civil servant in the Edinburgh Office of Works, and Mary Doyle.

Doyle was educated in Jesuit schools and produced his first story, an illustrated tale of a man and a tiger, at the age of six. He entered medical school at the behest of his parents and obtained his medical degree from the Edinburgh University.[1] He wrote his first piece of fiction, a short story in the October issue of Chamber’s Journal in 1879 and earned three guineas.

As a medical student, Doyle administered near fatal dose of gelsemium, an alkaloid stimulant, to himself and concluded that the maximum dose that could be administered was more than what was mentioned in the textbooks. He published his findings in 1879 in the British Medical Journal.[2] He also described the treatment of leucocythemia (leukemia) with large doses of arsenic, iodine and chlorate of potash.[3] This was published in the Lancet. The reputed journal unfortunately spelt the name of one of the greatest writers as “A. Cowan Doyle.”[1] It is no wonder that Doyle found his calling in journals away from the medical ones. He, however, wrote stories from the world of medicine in Round the Red Lamp. Being Facts and Fancies of Medical Life, tackling both the dark and the light side of it. The ardent followers would have already drawn the connection- Mr Holmes used to self-inject himself with cocaine, had “profound knowledge of chemistry” and was “well up in belladonna, opium and poisons in general”!

Doyle qualified as a doctor in 1885. He signed up as a ship surgeon and hopped aboard a steamer to West Africa, more in search of adventure than to earn a livelihood. Once back, his attention was drawn to ophthalmology while his soul could not deny being drawn to literature. His work received appreciation and encouragement from greats like Oscar Wilde.

In a letter to his sister, Doyle expresses his desire, “If it (Micah Clarke) comes off, we may have a few hundreds to start us. I should go to London and study the eye. I should then go to Berlin and study the eye. I should then go to Paris and study the eye. Having learned all there is to know about the eye, I should come back to London and start as an eye-surgeon, still, of course, keeping literature as my milk-cow.” [1] This was at the time that he had just finished a historical novel, Micah Clark. Even in his earlier work, The Stark Munro Letters, he referred to ophthalmology as a career with good chance to earn well in smaller cities where there were no eye doctors to treat astigmatism, squint and cataracts, “There is money in ears, but the eye is a gold mine.”[1] In 1890, he moved to Vienna to acquire greater skills in ophthalmology. Unfortunately, lessons in German did little to help him. On returning to London, Doyle practiced medicine as an eye specialist at Southsea near Portsmouth in Hampshire. He restricted himself to refraction and retinoscopy. Talking about his practice, “Every morning I walked from the lodgings at Montague Place, reached my consulting room at ten and sat there until three or four, with never a ring to disturb my serenity. Could better conditions for reflection and work be found?”[4]

Doyle drew the characters of his stories from the people he knew and perhaps that is what made them so vivid and endearing. In the medical school he met several people who left a mark on him. Professor William Rutherford, the “ruthless vivisector”, was the basis for Professor Challenger from Doyle’s The Lost World, The Poison Belt and The Land of Mist.[4] This was in an era when “science fiction” was not recognized as a genre and Doyle had written these as “boy’s books.” Interestingly, Professor Challenger was one of Doyle’s favorite characters, “a character who has always amused me more than any other which I have invented.” In some of the pictures for the books of The Lost World, he even disguised himself as Professor Challenger. Dr Reginald Ratcliffe Hoare, a general practitioner in Birmingham, became the model for Dr Horton in The Stark-Munro Letter, a delightfully humorous autobiographical take on his life at Birmingham and his short stint as a partner in the clinic of George Budd, a medical school friend.[5]

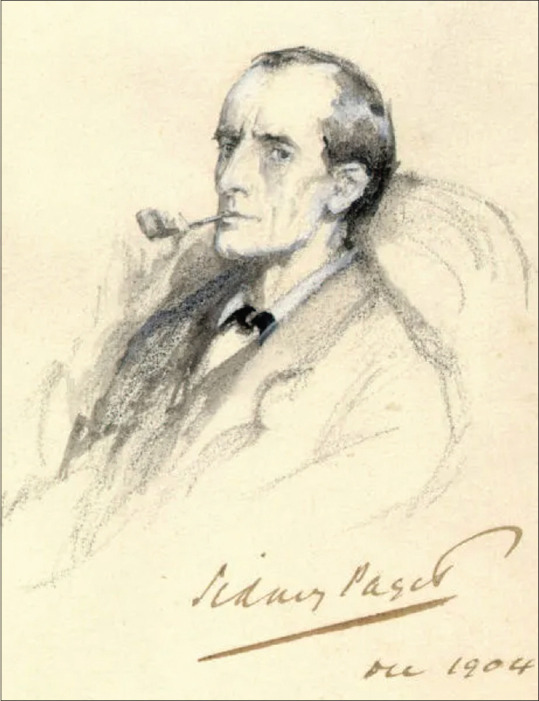

It is well known that Doyle based his most well known protagonist on the character of Dr Joseph Bell, the surgeon at Edinburgh infirmary, whose ability to diagnose, deduce and draw logical conclusions were both inspirational and influential for young Arthur’s mind that craved for constant activity of the grey cells. Doyle had the good fortune to be his outpatient clerk and as he mentioned, “I had ample chance of studying his methods and of noticing that he often learned more of the patients by a few quick glances than I had done by all my questions.” The name itself, Holmes, was a tribute to one of Doyle’s idols, Dr Oliver Wendell Holmes. “Never have I so known and loved a man whom I had never seen. It was one of the ambitions of my lifetime to look upon his face.” Doyle tried to find the fitting first name, playing with combinations of Sherringford Holmes and Sherrington Hope before chancing upon an old Irish name, Sherlock…knowing little how famous that name was about to be. Contrary to popular belief, John Watson, is not Arthur Conan Doyle. Doyle named him after a young friend and colleague, Dr James Watson. But the model for Watson’s personality remains a mystery. In the first of the four Holmes’ novels, A Study in Scarlet, Sherlock Holmes is described by Dr Watson as a man with such a striking appearance to catch the attention of even the most casual observers, “Rather over six feet and so excessively lean that he seemed considerably taller. His eyes were sharp and piercing, save during the intervals of temper to which I have alluded; and his thin hawk-like nose gave his whole expression an air of alertness and decision. His chin too had the prominence and squareness which mark the man of determination.” The illustrator of the stories, Sidney Paget, found the perfect model in his brother, Walter [Fig. 1].

Figure 1.

Illustrative sketch of Sherlock Holmes by Sidney Paget

Doyle wrote A Study in Scarlet in a span of six weeks and was in for a rude surprise when his novel was rejected by multiple publishers without a second glance. Desperate for money, Doyle approached a publishing house, known to publish cheap and sensational literature, who bought the complete copyright for 25 pounds, never to pay Doyle again for all the revenues they got from the numerous editions of the book and the cinema rights.

Doyle liked his ophthalmology practice, but it never took off to support him financially. On the other hand, his literary skills had already taken roots. By 1891, he was writing as a seasoned writer having published 18 short stories, 2 articles, two volumes of collected stories and one novel in press. He had successfully entered into a deal with the Strand Magazine who would be publishing the Sherlock Holmes stories. In April 1891, the first weeks of his practice, he sent four of the first six Sherlock Holmes short stories to the publishers. On the May of 1891, after a severe bout of influenza, Doyle decided to give up his medical profession, “and I determined with a wild rush of joy to cut the painter and to trust for ever to my power of writing. I remember in my delight taking the handkerchief which lay upon the coverlet in my enfeebled hand, and tossing it up to the ceiling in my exultation. I should at last be my own master.”

The second Sherlock Holmes story was the The Sign of the Four followed by The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. At the end of 1891, Doyle planned to end the series as it was distracting him from writing serious works. He aspired to be a historical writer and in 1893, he became so tired of his detective that he devised his death in the The Final Problem where Holmes meets his nemesis, the evil genius, Professor Moriarty, at the falls of the Reichenbach in Switzerland, and disappears. However, Doyle’s readers were outraged to say the least. Twenty thousand readers cancelled their Strand subscriptions and Doyle received more than just his share of hate mails.

After spending years tending to his sick wife, volunteering as a medical doctor in the Boer War and trying his hand at politics, an exhausted Doyle spent a prolonged period in the moors of Devonshire. While there, he visited the prehistoric ruins and heard tales of an escaped convict and a local legend of a hell hound. This was his inspiration for the “satanic tale of a gigantic hell, a devil incarnate who stalks the wastes of Dartmoor wreaking a terrible vengeance upon the heirs of the House of Baskervilles.” But Doyle needed a hero to match the evil lurking in the moors. “Why should I invent such a character, when I already have him in the form of Sherlock Holmes?” Doyle narrated an early case of the dead detective. The story is presented as if Dr Watson had overlooked it in his notebook and so dates back to a time before Holmes died. The first episode of The Hound of Baskervilles was published in the Strand in August of 1901.[6] Because of the public demand, Doyle finally resurrected his popular hero in The Empty House and subsequent tales.

Doyle made Holmes appear detached and devoid of emotion but the traces of human qualities - friendship and fighting for justice - can be found hidden within the layers of his personality in the pages of the books. Arthur himself was a strong voice against injustice and often went out of his way to help wronged convicts. He once saved a young man when he proved that the man had such poor eyesight that he could not have slaughtered the horses and cows that he was being convicted for.[6] Doyle was knighted in 1902 by King Edward VII for services rendered in the Boer War. He died on July 7, 1930. He was the author of more than 50 books, 14 novels and 56 short stories including historical novels, science fiction, domestic comedy, seafaring adventure, the supernatural, poetry, military history and many other subjects. Arthur Conan Doyle is as brilliant as his detective. Even though he chooses to play the part of Dr Watson, there can be no doubt that it is his mind which is working through his central character. For once, Ophthalmology is shamelessly unapologetic about losing a genius to Literature.

“There’s no need for fiction in medicine,…for the facts will always beat anything you fancy.” Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Round the Red Lamp. Being Facts and Fancies of Medical Life.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Snyder C. There's money in ears, but the eye is a gold mine;Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's brief career in ophthalmology. Arch Ophthalmol. 1971;85:359–65. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1971.00990050361023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Doyle AC. Gelseminum as a poison. Br Med J. 1879;2:483. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Conan Doyle A. Notes on a case ofleucocythaemia. Lancet. 1882;490 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conan Doyle A. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1989. Memories and Adventures. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Watts MT. The mysterious case of the doctor with no patients. J R Soc Med. 1991;84:165–6. doi: 10.1177/014107689108400317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. [Last accessed on 2021 Nov 07]. Available from: https://www.arthurconandoyle.com/biography.html .