Abstract

Purpose:

Early diagnosis of keratoconus (KCN) and corneal collagen cross-linking can ensure that best-corrected visual acuity is preserved. We report the sequence of events leading to the diagnosis of KCN, as well as its impact on quality of life.

Methods:

This survey-based study included patients diagnosed with KCN for the first time at our center. Their corneal tomography was analyzed, and they were provided with a proforma and the NEI-VFQ-25 questionnaire and were asked to answer the given set of questions.

Results:

The study included 328 eyes of 164 patients. At the time of diagnosis, 112 (68.3%) patients were not aware of a disease called “keratoconus.” VKC was present in 56 patients, and 92 patients were not aware of the need to avoid eye rubbing. In total, 101 patients gave a history of sleeping more often on the side with worse KCN. The preferred primary point of contact was an optometrist for 45.1% of patients; 51.2% of patients reported never having visited an ophthalmologist. Sixty-four (39%) patients were advised a screening test to rule out KCN before presenting to our center; 42 (71.8%) of these patients did not get it done. Vision-targeted score showed a significant negative correlation with grade of KCN (r value: −0.471) and positive correlation (r value: 0.534) with LogMAR vision.

Conclusion:

KCN is a disease of the young and severely affects the quality of life. Improving awareness of the general public, ensuring timely referral by optometrists, and keeping a high index of suspicion is emphasized.

Keywords: Corneal collagen cross-linking, keratoconus, quality of life

Keratoconus (KCN) is a noninflammatory, progressive, bilateral, and asymmetric corneal ectatic disorder.[1,2] It is primarily a disease of young individuals around the pubertal period, with most cases becoming clinically apparent in late teens to early twenties.[2,3] It has a progressive course, and the progression, if not halted, often leads to irreversible reduction in best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA).[3] The significant asymmetry reduces the ability of sphero-cylindrical spectacle lenses to adequately correct vision in most advanced cases. It has been reported that in Asian-Indian patients, the majority of eyes with KCN demonstrate a severe stage of the disease by the second decade.[4]

Most people in developing countries rely on optometrists to get their refraction checked and may not find it necessary to visit an ophthalmologist for an issue that they consider as minor, including a change in the refractive error.[5] Moreover, many eye care centers lack facilities for corneal topography, which is the primary diagnostic tool for early KCN detection.[6] Inability to refract to a BCVA of 20/20, presence of irregular/oblique astigmatism, scissoring reflex on retinoscopy, and high keratometry values of auto-refractor should arise suspicion to screen a patient for KCN. Awareness among the public about this disease pathology is limited, unlike other common eye pathologies.[7]

With the introduction of corneal cross-linking (CXL), we can halt the progression of KCN and have reduced the need for corneal transplantation.[8] Still, we continue to see patients in cornea clinics with KCN related reduced quality of life either due to reduced BCVA or dependence on rigid contact lenses.[9] Many undiagnosed cases are seen to present with acute hydrops.[4,10] It is indeed unfortunate that most of these consequences could have been prevented with timely intervention. This motivated us to study the sequence of events leading to the diagnosis of a patient with KCN, to enable us to highlight the areas which can help improve early diagnosis and management of such patients.

Methods

This survey-based study was approved by the institutional review board. Informed consent was taken from all subjects or their legal guardians (younger than 18 years of age). The study included patients over the age of 12 years who were diagnosed with subclinical or clinical KCN for the first time at our tertiary eye center. The diagnosis of KCN was performed via corneal topography (Pentacam, Oculus, Wetzlar Germany)], refraction, and clinical examination. Demographic data, BCVA (at presentation to our institute), and pentacam records of every subject were retrieved. Staging of KCN was done according to the modified Amsler Krumeich staging classification system, and the inter-eye asymmetry score was assessed according to a scoring system [Annexure 1]. They were provided with a proforma [Annexure 2] and the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ-25) questionnaire [Annexure 3] and were asked to answer the given set of questions at the time of diagnosis. The sequence of events leading to the diagnosis of KCN was thoroughly investigated. Ethics Committee approval was received on 25/07/2020.

Results

The present study included 328 eyes of 164 patients diagnosed with clinical or subclinical KCN at a tertiary eye care center in India. The mean age of patients at the time of diagnosis was 20.82 ± 5.89 years. The youngest patient was 12 years old and the oldest was 36 years old. There were 106 (64.6%) males and 58 females (35.4%). Out of 164 patients of KCN, 3 (1.8%) were younger than 14 years of age and were classified as pediatric KCN. Two patients (1.2%) presented with acute hydrops as the initial presentation at the time of diagnosis. These two male patients were 20 and 19 years old respectively. Systemic illness was present in 8 (4.9%) patients, 2 had bronchial asthma, 2 had allergic dermatitis, and 4 had allergic rhinitis.

History of vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) was present in 56 (34.1%) patients, with 37 (22.6%) patients being symptomatic for more than one year. Ninety-two (56.1%) patients were not aware of the need to avoid eye rubbing, whereas 26 (15.9%) and 46 (28%) patients remembered being advised against eye rubbing by an optometrist and ophthalmologist, respectively. One hundred and one (61.6%) patients gave a history of sleeping more often on the side with worse KCN. One hundred and eighteen (71.9%) used spectacles for vision correction as compared to 46 (28.1%) using contact lenses.

At the time when diagnosis of KCN was made, 112 (68.3%) patients were not aware of a disease called “keratoconus.” Ten (6.1%) and 36 (22%) patients were hinted about the possibility of this disease by their optometrist or ophthalmologist, respectively. Six (3.7%) were aware of the condition due to the presence of a similar condition in a family member or acquaintance. Out of 52 patients who were aware of the condition, 48 (92.3%) were aware of the possible consequences of progression in this condition.

Previous ocular examination

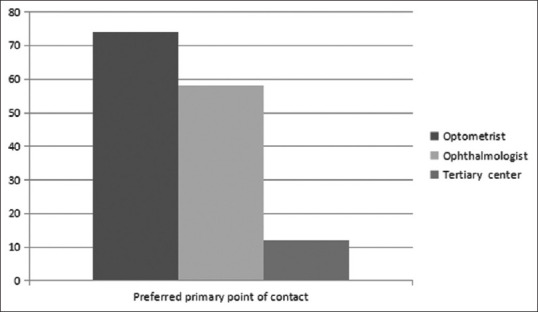

Seventy-four (45.1%) patients preferred visiting an optometrist for their complaints. The distribution of the preferred primary point of contact for patients is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the preferred primary point of contact for patients

Despite a drop in BCVA, 84 (51.2%) patients reported never having visited an ophthalmologist before presenting to our tertiary eye care center. The factors associated with not consulting an ophthalmologist are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Factors associated with not consulting an ophthalmologist

| Factors associated with not consulting an ophthalmologist | Number of patients (Percentage patients) |

|---|---|

| No ophthalmologist in the vicinity | 6 (7.1%) |

| Faith in local practitioner/optician | 14 (11.9%) |

| Considered it a minor problem | 62 (66.7%) |

| Cost factor [2 (2.4%)] | 2 (2.4%) |

Sixty-four (39%) patients were advised a screening test (corneal topography) to rule out KCN before presenting to our tertiary care center. Forty-two (71.8%) of these patients did not get it done. Factors attributed to not getting a screening test done are summarized in Table 2. Twenty-two (13.4%) patients underwent a screening test for KCN in the form of corneal topography. However, none of them were diagnosed as KCN at that time. The time interval between the last screening test and KCN diagnosis at the tertiary center was 18 ± 5.9 months.

Table 2.

Factors for not undergoing screening corneal topography

| Factors for not undergoing screening corneal topography | Number of patients (Percentage patients) |

|---|---|

| Found the test to be unnecessary/considered the disease a minor problem | 15 (35.7%) |

| High cost | 12 (28.5%) |

| Non-availability of the machine required for test in the concerned center | 10 (23.8%) |

| Lack of time/too busy | 5 (11.9%) |

First visit to a tertiary eye care system where diagnosis of KCN was made

Fifty-two (31.7%) patients were referred by an optometrist or previous practitioner. The reasons for visiting our tertiary eye care center when the first diagnosis of KCN was made were as follows: referred by previous practitioner [16 (9.7%)], referred by optometrist [40 (24.4%)], “not satisfied with glasses prescribed elsewhere” [46 (28%)], first consultation for reduced vision [58 (35.4%)], and consult for some other complaint [4 (2.4%)].

Visual acuity and refractive error

Corrected distance visual acuity and refractive variables are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Visual Acuity and Refractive variables

| Parameter | Mean±standard deviation (range) |

|---|---|

| CDVA (logMAR) | 0.27±0.24 (0-1.6) |

| Spherical Equivalent (D) | 2.62±1.95 (0.25-11.5) |

| Cylinder (D) | 2.80±1.45 (0.5-7) |

| Axis | 105.81±49.96 (10-180) |

| K mean (D) | 48.26±4.75 (40.6-66.1) |

| K max (D) | 54.19±7.35 (42.3-87.6) |

Corneal tomography

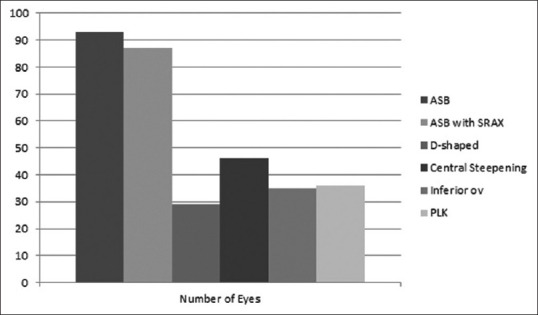

A diagnosis of clinical KCN was made based on clinical features, refraction, and corneal tomography. Subclinical KCN was diagnosed based on corneal tomography suggestive of KCN. The distribution of various patterns on axial/sagittal curvature is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Distribution of various patterns on axial/sagittal curvature

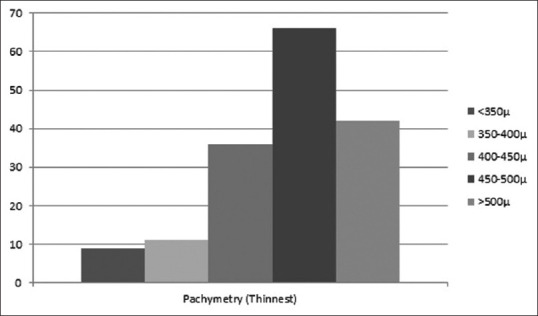

The mean pachymetry at the thinnest point was 62.7805 ± 60.8 Microns (range: 303–570). Distribution of pachymetry at the thinnest location is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Distribution of pachymetry at the thinnest location

Inter-eye asymmetry score

The distribution of inter-asymmetry score was <3 in 45 (27.4%), 3 in 25 (15.2%), and 4–5 in 94 (57.3%) patients. It was found that 112 (68.3%) had never noticed a difference in vision in the two eyes, whereas 52 (31.7%) were aware of some difference.

Stage of KCN

The distribution of stage of KCN (modified Amsler Krumeich staging) in the worse eye at the time of diagnosis was as follows: Stage 1 in 40 (24.4%), 2 in 78 (47.6%), 3 in 6 (3.6%), and 4 in 38 (23.2%) patients. Two (1.2%) patients presented with acute hydrops at the time of diagnosis.

After diagnosing KCN, they were offered options for visual rehabilitation. Ninety-six (58.5%) selected spectacles, 26 (15.8%) selected rigid contact lenses, and 42 (25.6%) selected scleral contact lenses.

Quality of life

·NEI-VFQ-25

All 164 patients completed the NEI-VFQ-25 questionnaire and were included in the analysis. The scores are summarized in Table 4. Further, we asked the patients about the effect of reduced vision on the career they wish to pursue, and 46 (28.1%) patients self-reported that they felt that their choice of career was now compromised because of poor vision attributed to the diagnosis of KCN. We studied the correlation of vision-targeted composite score with various variables. It showed no relation with age of diagnosis (r value: −0.005) but showed a significant negative correlation with grade of KCN (r value: −0.471) and positive correlation (r value: 0.534) with LogMAR vision at presentation.

Table 4.

National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ-25) scores

| General Health | General Vision | Ocular Pain | Near Activities | Distance Activities | Social Function | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | 71.91±28.3 | 55.8±19.2 | 80±21.7 | 82.82±14.7 | 78.8±17.7 | 88.12±15.7 |

| Range | 0-100 | 20-100 | 20-100 | 25-100 | 25-100 | 50-100 |

|

| ||||||

| Mental Health | Role difficulties | Dependency | Driving | Color vision | Peripheral vision | |

|

| ||||||

| Mean±SD | 62.9±18.5 | 81.9±21.6 | 92.1±14.5 | 83.3±11.6 | 96.6±8.6 | 94.1±6.6 |

| Range | 18.75-93.75 | 25-100 | 33.3-100 | 58.3-100 | 75-100 | 75-100 |

Discussion

KCN is primarily a disease of early adulthood, beginning typically at about the age of puberty, and usually progresses over the next 10 − 20 years.[1] The mean age of patients at the first visit to an ophthalmologist, as also the age at which diagnosis of KCN was made, was 20.82 ± 5.89 years in our study. It affects both genders; however, gender predisposition is unclear, with some studies reporting equal prevalence between genders;[11,12] while other investigators have found a greater prevalence in males,[13,14] as is also supported by our study. The mean cylindrical refractive error at presentation was 2.80 ± 1.45 (range: 0.5 − 7) D. It is imperative to point out that KCN can present with low cylindrical power, and a high index of suspicion is necessary to diagnose this condition. Correlation of history of VKC to KCN goes in coherence with other studies,[15,16] but the tragic part highlighted is the lack of awareness among patients about the relation between eye rubbing and KCN, with the majority of patients (56.1%) not knowing about this correlation. Ignorance among patients and lack of regulations necessitating regular follow-up with an ophthalmologist might be the reason, which needs to be worked on.

In our study, 101 (61.6%) patients gave a history of sleeping more often on the side with worse KCN. Similarly, a recent study highlighted that in KCN patients, the most affected eye correlated with the preferential side on which patients were used to sleeping.[17] This likely association can be explained by compression forces on the eye, which results in the release of inflammatory mediators, which further result in keratocyte apoptosis, contributing to stromal thinning.

The natural course of KCN is progressive, and the disease can only be halted at the stage at which it is diagnosed.[1,14] In our study, 22 (13.4%) patients, despite undergoing a screening test for KCN (corneal topography), were not diagnosed as KCN at that time. The time interval between the last screening test and KCN diagnosis at our tertiary center was 18 ± 5.9 months. Therefore, a higher suspicion and regular examination will ensure that patients are diagnosed at an early stage of KCN. In our study, we found that at the time when the diagnosis of KCN was made for the first time, as many as 38 (23.2%) patients were at stage four of KCN. Furthermore, in two patients, acute hydrops was the presenting feature of KCN. Literature supports that most of the cases of acute hydrops are seen in the second or the third decade with preponderance for the male gender.[10] In our study too, the two patients were males and were 19 and 20 years old, respectively. Both these patients, despite being spectacle users for 5 and 6 years, respectively, had never visited an ophthalmologist and were never screened for KCN. Reduced vision at the time of diagnosis (log MAR: 0.29 ± 0.29) is also highlighted in the study. This indicates that a substantial loss of visual acuity had already occurred in the patients by the time a confirmatory diagnosis of KCN was made. Furthermore, 20 (12.2%) of these patients had a thinnest pachymetry of <400 m, making CXL a challenge.[8]

We investigated the sequence of events related to the diagnosis of KCN in these patients. The preferred primary point of contact was an optometrist in the majority of patients (45.1%), indicating that the role of optometrists needs to be emphasized to ensure early diagnosis of KCN. Despite BCVA getting worse than 6/6, patients did not prefer to consult an ophthalmologist/tertiary eye care center; 51.4% of patients had never visited an ophthalmologist for their complaints. It is alarming to note that 56 (66.7%) of these patients never visited an ophthalmologist as they considered it to be a minor issue. Most of the patients (68.3%) were unaware of the disease entity and were never screened (68.3%), suggesting the need to improve awareness among patients and healthcare professionals.

KCN is known to be a bilateral asymmetric condition.[18,19] The inter-eye asymmetry score in our study was 4 − 5 in 94 (57.3%) patients. Further, upon assessing whether patients had ever noticed any difference in visual acuity in the two eyes prior to being diagnosed with KCN, it was found that 112 (68.3%) had never noticed a difference in vision in the two eyes. Children may not notice a difference in vision in the two eyes, necessitating routine ophthalmological examination.

Similar studies on KCN reporting to tertiary care centers suggest that KCN in India presents at a younger age than in the Western population and progresses more rapidly.[4,20] This emphasizes the need to build up our reach of tertiary care facilities in the developing world. We follow a protocol of screening patients with corneal topography when either of the following criteria is met: inability to refract to 20/20 with high cylindrical power against the rule/oblique astigmatism, high keratometry value, and progressive increase in cylindrical power or keratometry value. Using this protocol, we have been able to pick up subclinical KCN at a relatively early stage. Various centers can come together to create a protocol to screen patients for KCN so that these cases can be picked up early in the course of the disease. We found that poor quality of life scores were associated with worse grade of KCN and BCVA at the time when the diagnosis was made. This is in coherence with previous studies.[21,22] Patients with the disease, unlike other ocular pathologies, belonged to a lower age group and hence reduction in quality of life seems more important and impactful.

Conclusion

Keratoconus is a disease of the young and severely affects their quality of life. Improving awareness of the general public, ensuring timely referral by optometrists, and keeping a high index of suspicion for KCN is emphasized.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Annexure 1: Inter-eye corneal asymmetry score

| Scoring criteria | Positive(+1 point) if inter-eye difference |

|---|---|

| Mean anterior keratometry | >=0.3 diopters |

| Mean posterior keratometry | >=0.1 diopters |

| Thinnest pachymetry | >=12 μm |

| Front elevation at thinnest location | >=2 μm |

| Back elevation at thinnest location | >= 5 μm |

Annexure 2: Quesstionnaire

| History |

|---|

| Allergic conjunctivitis/VKC in childhood |

| History present or absent |

| How many years were the patient symptomatic |

| Where was he getting treated |

| Did anyone mention that children should avoid rubbing of eyes |

| Was any screening test for keratoconus done |

| Any systemic disease/Syndrome |

| At what age did you notice a decrease in visual acuity? |

| Sleeping posture |

| Use of glasses/contact lenses and duration of use |

| Use of glasses/contact lenses |

| RGP/soft contact lenses |

| Duration |

| Vision with correction: RE LE |

| Comfort with use of contact lenses |

| Are you aware of a condition called “Keratoconus”? |

|

|

| Previous ophthalmological examination |

|

|

| Have you shown anywhere before? |

| Optometrist at spectacles shop |

| Ophthalmologist(private practitioner) |

| Ophthalmologist(at a tertiary center) |

| What were your complaints? |

| Why did you not show any ophthalmologist for refractive error? Why did you not consult any ophthalmologist after noticing a difference in BCVA of two eyes? |

| No ophthalmologist in the vicinity |

| Faith in local practitioner |

| Considered it as a minor eye problem |

| Did the previous examiner mention about keratoconus? If yes, what did you do then and why? |

| Was any screening test like ARK or Orbscan or any corneal topography done? What were the results? |

|

|

| Present visit |

|

|

| What are your complaints? |

| Why did you come to a tertiary care center now? |

| Referred by the previous practitioner |

| Not satisfied with glasses/contact lenses prescribed elsewhere |

| Came for first consultation for decreased visual acuity |

| Which option did you select for correction of vision? Why? |

| Glasses/Contact lenses |

| Contact lenses are not comfortable |

| Difficult to use contact lenses |

| Not much difference in visual acuity with glasses and contact lenses |

Annexure 3: NEI-VFQ-25 Questionnaire

PART 1 - GENERAL HEALTH AND VISION

1. In general, would you say your overall health is*:

Excellent 1; Very Good 2; Good 3; Fair 4; Poor 5

2. At the present time, would you say your eyesight using both eyes (with glasses or contact lenses, if you wear them) is:

Excellent 1; Good 2; Fair 3; Poor 4; Very Poor 5; Completely Blind 6

3. How much of the time do you worry about your eyesight?

None of the time 1; A little of the time 2; Some of the time 3 Most of the time 4; All of the time 5

4. How much pain or discomfort have you had in and around your eyes (for example, burning, itching, or aching)? Would you say it is:

None 1; Mild 2; Moderate 3; Severe 4; Very severe 5

PART 2 - DIFFICULTY WITH ACTIVITIES

| Task | No difficulty | A little difficulty | Moderate difficulty | Extreme difficulty | Stopped due to eyesight | Stopped due to other reasons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How much difficulty do you have reading ordinary print in newspapers? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| How much difficulty do you have doing work or hobbies that require you to see well up close, such as cooking, sewing, fixing things around the house, or using hand tools? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Because of your eyesight, how much difficulty do you have finding something on a crowded shelf? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| How much difficulty do you have reading street signs or the names of stores | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Task | No difficulty | A little difficulty | Moderate difficulty | Extreme difficulty | Stopped due to eyesight | Stopped due to other reasons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How much difficulty do you have driving during the daytime in familiar places? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | NA | NA |

| How much difficulty do you have driving at night? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| How much difficulty do you have driving in difficult conditions, such as in bad weather, during rush hour, on the freeway, or in city traffic? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Task | No difficulty | A little difficulty | Moderate difficulty | Extreme difficulty | Stopped due to eyesight | Stopped due to other reasons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Because of your eyesight, how much difficulty do you have going down steps, stairs, or curbs in dim light or at night? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Because of your eyesight, how much difficulty do you have noticing objects off to the side while you are walking along? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Because of your eyesight, how much difficulty do you have seeing how people react to things you say? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Because of your eyesight, how much difficulty do you have picking out and matching your own clothes? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Task | No difficulty | A little difficulty | Moderate difficulty | Extreme difficulty | Stopped due to eyesight | Stopped due to other reasons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Because of your eyesight, how much difficulty do you have visiting with people in their homes, at parties, or in restaurants ? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Because of your eyesight, how much difficulty do you have going out to see movies, plays, or sports events? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

15- Now, I would like to ask about driving a car. Are you currently driving, at least once in a while?

Yes- 1

No- 2

15a. IF NO: Have you never driven a car or have you given up driving?

Never drove -1

Gave up- 2

15b. IF GAVE UP DRIVING: Was that mainly because of your eyesight, mainly for some other reason, or because of both your eyesight and other reasons?

Mainly eyesight- 1

Mainly other reasons- 2

Both eyesight and other reasons- 3

The next questions are about how things you do may be affected by your vision.

| Task | All of the time | Most of the time | Some of the time | A little of the time | None ofthe time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you accomplish less than you would like because of your vision? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Are you limited in how long you can work or do other activities because of your vision? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| How much does pain or discomfort in or around your eyes, for example, burning, itching, or aching, keep you from doing what you would like to be doing? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Task | Definitely true | Mostly true | Not sure | Mostly false | Definitelyfalse |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I stay home most of the time because of my eyesight | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I feel frustrated a lot of the time because of my eyesight | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I have much less control over what I do because of my eyesight | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Because of my eyesight, I have to rely too much on what other people tell me | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I need a lot of help from others because of my eyesight | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I worry about doing things that will embarrass myself or others, because of my eyesight | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

References

- 1. Krachmer JH, Feder RS, Belin MW. Keratoconus and related noninflammatory corneal thinning disorders. Surv Ophthalmol. 1984;28:293–322. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(84)90094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kankariya VP, Kymionis GD, Diakonis VF, Yoo SH. Management of pediatric keratoconus-evolving role of corneal collagen cross-linking:An update. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2013;61:435–40. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.116070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vazirani J, Basu S. Keratoconus:Current perspectives. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7:2019–30. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S50119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Saini JS, Saroha V, Singh P, Sukhija JS, Jain AK. Keratoconus in Asian eyes at a tertiary eye care facility. Clin Exp Optom. 2004;87:97–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0938.2004.tb03155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. De Souza N, Cui Y, Looi S, Paudel P, Shinde L, Kumar K, et al. The role of optometrists in India:An integral part of an eye health team. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2012;60:401–5. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.100534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Matalia H, Swarup R. Imaging modalities in keratoconus. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2013;61:394–400. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.116058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ambrósio R. Violet June:The global keratoconus awareness campaign. Ophthalmol Ther. 2020;9:685–8. doi: 10.1007/s40123-020-00283-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mohammadpour M, Masoumi A, Mirghorbani M, Shahraki K, Hashemi H. Updates on corneal collagen cross-linking:Indications, techniques and clinical outcomes. J Curr Ophthalmol. 2017;29:235–47. doi: 10.1016/j.joco.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gothwal VK, Reddy SP, Fathima A, Bharani S, Sumalini R, Bagga DK, et al. Assessment of the impact of keratoconus on vision-related quality of life. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:2902–10. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barsam A, Petrushkin H, Brennan N, Bunce C, Xing W, Foot B, et al. Acute corneal hydrops in keratoconus:A national prospective study of incidence and management. Eye. 2015;29:469–74. doi: 10.1038/eye.2014.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McGhee CN. 2008 Sir Norman McAlister Gregg Lecture:150 years of practical observations on the conical cornea –what have we learned? Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;37:160–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2009.02009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kennedy RH, Bourne WM, Dyer JA. A 48-year clinical and epi-demiologic study of keratoconus. Am J Ophthalmol. 1986;101:267–73. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(86)90817-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nielsen K, Hjortdal J, Aagaard Nohr E, Ehlers N. Incidence and prevalence of keratoconus in Denmark. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2007;85:890–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.00981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Owens H, Gamble G. A profile of keratoconus in New Zealand. Cornea. 2003;22:122–5. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200303000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wagner H, Barr JT, Zadnik K. Collaborative longitudinal evaluation of keratoconus (CLEK) study:Methods and findings to date. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2007;30:223–32. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zadnik K, Steger-May K, Fink BA, Joslin CE, Nichols JJ, Rosenstiel CE, et al. CLEK Study Group. Between-eye asymmetry in keratoconus. Cornea. 2002;21:671–9. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200210000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mazharian A, Panthier C, Courtin R, Jung C, Rampat R, Saad A, et al. Incorrect sleeping position and eye rubbing in patients with unilateral or highly asymmetric keratoconus:A case-control study. Graefe's Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020;258:2431–9. doi: 10.1007/s00417-020-04771-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Totan Y, Hepşen IF, Çekiç O, Gündüz A, Aydın E. Incidence of keratoconus in subjects with vernal keratoconjunctivitis:A videokeratographic study. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:824–7. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00664-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Taneja M, Ashar JN, Mathur A, Vaddavalli PK, Rathi V, Sangwan V, et al. Measure of keratoconus progression in patients with vernal keratoconjunctivitis using scanning slit topography. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2013;36:41–4. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2012.10.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jonas JB, Nangia V, Matin A, Kulkarni M, Bhojwani K. Prevalence and associations of keratoconus in rural maharashtra in central India:The central India eye and medical study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148:760–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kymes SM, Walline JJ, Zadnik K, Gordon MO, Collaborative Longitudinal Evaluation of Keratoconus (CLEK) Study Group Quality of life in keratoconus. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138:527–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tan JC, Nguyen V, Fenwick E, Ferdi A, Dinh A, Watson SL. Vision-related quality of life in keratoconus:A save sight keratoconus registry study. Cornea. 2019;38:600–4. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]