Abstract

Objectives:

To develop and validate a score to accurately predict the probability of death for adult ECPR.

Background:

Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR) is being increasingly utilized to treat refractory in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA), but survival varies from 20-40%.

Methods:

Adult patients with ECMO for IHCA (ECPR) were identified from the American Heart Association Get With The Guidelines – Resuscitation registry. A multivariate survival prediction model and score built to predict hospital death. Findings were externally validated in a separate cohort of patients from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry who underwent ECPR for IHCA.

Results:

A total of 1075 patients treated with ECPR were included. Twenty eight percent survived to discharge in both the derivation and validation cohorts. A total of 6 variables were associated with in-hospital death: age, time of day, initial rhythm, history of renal insufficiency, patient type (cardiac vs non-cardiac and medical vs surgical), and duration of the cardiac arrest event which were combined into the RESCUE-IHCA score. The model had good discrimination (area under the curve [AUC]) of 0.719 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.680, 0.757) and acceptable calibration (Hosmer and Lemeshow Goodness of Fit) p=0.079). Discrimination was fair in the external validation cohort (AUC of 0.676 (95% CI: 0.606, 0.746) with good calibration (p=0.66), demonstrating the model’s ability to predict in-hospital death across a wide range of probabilities.

Conclusions:

The RESCUE-IHCA score can be used by clinicians in real-time to predict in-hospital death among patients with IHCA who are treated with ECPR.

Keywords: Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation, In-hospital cardiac arrest, Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, Mortality prediction, Survival prediction

CONDENSED ABSTRACT

Using 6 simple patient/arrest characteristics, the probability of hospital mortality can be predicted (72% accuracy) for patients with IHCA treated with ECPR (RESCUE-IHCA score). Five characteristics can be known upon initial patient assessment are non-modifiable (age, time of day, initial rhythm, history of renal insufficiency, patient type (cardiac vs non-cardiac and medical vs surgical)); one is potentially modifiable (duration of resuscitation). The score was derived from 1075 adult ECPR patients from a national registry (AHA GWTG-R) and had fair discrimination and good calibration; the score externally validated among 297 patients from the international ELSO Registry who received ECPR for IHCA.

Tweet/handle:

JoeTonnaMD; The RESCUE-IHCA score predicts in-hospital death among patients with IHCA treated w/ ECPR. Age, nighttime, non-VF, renal insufficiency, medical non-cardiac etiology, longer duration to ECPR all have higher mortality. RESCUE-IHCA Score has 72% accuracy & is externally validated

INTRODUCTION

Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR) is increasingly utilized worldwide as a rescue technique among patients with refractory cardiac arrest (1). ECPR is used to rescue patients who arrest in-hospital and those with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) brought into the emergency department. As a component within a bundle of interventions for OHCA due to refractory ventricular fibrillation, ECPR was recently shown to be highly effective in improving survival and good neurological outcome compared to conventional CPR in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) (2). Although RCTs demonstrating the effectiveness of ECPR in IHCA are lacking, observational studies have reported 20-40% survival (3,4). However, there is large variation in this survival benefit highlighting the importance of patient selection (5). Information on patient factors associated with improved survival with ECPR remains limited but important to understand given the associated complications and cost/resources need to deliver ECPR care (6-8).

Models to predict survival in patients receiving ECMO have been developed in patients with cardiogenic shock and respiratory failure (9,10). However, ECMO for IHCA (i.e., ECPR) represents a unique clinical condition where survival is likely dependent on resuscitation-specific variables such as duration of resuscitative efforts (11). Prior studies of in-patient ECPR are limited by small sample size and limited generalizability due to inclusion of a small number of sites (12).

To address this gap in knowledge, we conducted a large national study of ECPR among 1075 patients from 219 centers participating in the Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation (GWTG-R) registry to develop a mortality prediction model using simple baseline and arrest characteristics and display the results with a simple to calculate score. The model was designed to be used by clinicians in real-time for use within patients who receive ECPR to treat their IHCA to inform their probability of death. We externally validated our model in a separate cohort of ECPR patients from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) Registry.

METHODS

Our analysis is reported according to the Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) guideline and incorporated best practice recommendations for variable selection and model construction when using existing observational datasets, including reporting model calibration, prediction accuracy, checking for overfitting, and external validation (Supplement). Analysis was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Utah #91962.

Data Source

Data were obtained from the American Heart Association GWTG-R Registry. Briefly, patients are defined as having an IHCA if they have lack of pulse, apnea, and unresponsiveness, without do-not-resuscitate orders, and subsequently receive chest compressions / cardiopulmonary resuscitation or defibrillation. Registry details are given in the Supplement.

Study Population

We identified inpatient cardiac arrest events from 2000-2018 that were treated with ECPR as part of the arrest. This population has been previously described in detail (5), and is listed in the Supplement. Briefly, we excluded patients <18 years of age, and those with OHCA preceding admission. We excluded all non-index cardiac arrest events for each patient, patients from hospitals which had submitted less than 6 months of data or fewer than 5 cardiac arrest events submitted to the GWTG Registry and patients with missing neurologic outcome data.

External Validation Cohort

The validation cohort was obtained from patients entered into the ELSO Registry during the year 2017. Registry details are in the Supplement but briefly, patients were included if they were ≥18 years of age, had an IHCA during admission, did not have an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest prior to admission, and had been decannulated from ECMO (Supplement). Patients overlapping between the ELSO and GWTG-R Registries were identified through previously described linkage using these two datasets (13), and were excluded from the validation dataset.

Study Outcome and Variables

Our primary outcome was in-hospital death. Candidate predictor variables selected a priori included patient and arrest characteristics previously associated with survival after both cardiac arrest and/or ECMO. These variables are listed in detail in the Supplement but broadly included demographics; initial arrest rhythm; patient type; location of cardiac arrest; time of day and day of week of cardiac arrest; comorbid medical conditions prior to arrest; therapeutic interventions in place at the time of cardiac arrest; and intra-arrest characteristics and treatments. Handling of missing data is presented in Supplement.

Statistical Analysis

Potential predictors were summarized descriptively stratified by discharge survival status. Continuous variables were summarized as median (interquartile range IQR) and categorical variables were summarized as frequency and row percent. Univariable comparisons of each predictor between survivors and non-survivors were done using Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables and Chi-squared tests for categorical variables. Variables associated with survival with a p ≤0.1 in univariate analyses were included in the final multivariable model. Variable multicollinearity was then checked among candidate predictors using a variable inflation factor (VIF). We intentionally excluded race from the prediction model, to avoid encouraging racial bias in the use of ECPR, given that race is often a surrogate for unmeasured variables such as socio-economic status.

A multivariable model predicting survival was developed using Bayesian model averaging after multiple imputation (14). Briefly, twenty augmented datasets were generated where missing variables were imputed using regression methods in the R package MICE (15). Bayesian model averaging was performed on each of the imputed data sets, and the models were combined to form a final prediction model where coefficients were averaged across the twenty models. Model accuracy was assessed as area under the curve (AUC). Bootstrapping was used to construct 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the odds ratios (ORs). A score to predict the probability of survival was then constructed to allow individual predictions without the need of model refitting. A Hosmer-Lemeshow (HL) test was conducted for the final model to assess model Goodness of Fit (16). Predicted values for death were categorized into quintiles, and plotted versus their observed values, along with a goodness of fit line. An p-value >0.05 suggests acceptable model fit. Finally, as patients who arrested in the operating room may have been characteristically different than other patients, some of whom included cardiac surgery patients who had access to cardiopulmonary bypass, a sensitivity analysis was done to describe differences between cardiac surgical patients and other patients and then to exclude patients who arrested in the operating room (Supplement). The final model was then externally validated using data on patients ≥18 years of age from the ELSO Registry who were treated with ECPR. Variable matching and categorization for external validation is presented in the Supplement.

ORs, 95% CIs and p-values were reported from all models. Statistical analyses were conducted in R v.3.4, significance was assessed at the 0.05 level and all tests were two-tailed.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Among patients in the GWTG-R registry, 1075 had a cardiac arrest treated with ECMO and met criteria for analysis (Figure 1). Survivors (28%, n=306) were younger than non-survivors (58 years [IQR 47, 68] vs 61 years [48, 72]; p=0.019) and were more likely to be of white race than non-white race (31% vs 21%; p<0.001) but were otherwise similar in sex (29% vs 27% male; p=0.36) or weight (78kg [68, 93] vs 80kg [67, 97]; p=0.26) (Table 1). Survivors were less likely to have history of pre-existing renal insufficiency prior to arrest (20% vs 31%; p<0.001) but had otherwise similar comorbidities.

Figure 1: Study enrollment flowchart.

Patients with IHCA from the AHA GWTG-R Registry treated with ECPR. Patients with prior OHCA, non-index arrest, or missing outcome data were excluded, as were patients who arrested at a hospital where ECPR had not previously been performed.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Variable | Dead (N=769) | Alive (N=306) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 61 (48, 72) | 58 (47, 68) | 0.019 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 467 (71%) | 195 (29%) | 0.36 |

| Female | 302 (73%) | 111 (27%) | |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 547 (69%) | 249 (31%) | <0.001 |

| Non-white | 219 (79%) | 57 (21%) | |

| Hispanic ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| No | 726 (71%) | 294 (29%) | 0.26 |

| Yes | 43 (78%) | 12 (22%) | |

| Weight(kg), Median (IQR) | 80 (67, 97) | 78 (68, 93) | 0.49 |

| Pre-existing conditions, n (%) | |||

| Hypoperfusion prior to arrest | |||

| No | 418 (69%) | 186 (31%) | 0.06 |

| Yes | 348 (74%) | 120 (26%) | - |

| Stroke or neurologic disorder | |||

| No | 695 (72%) | 277 (28%) | 0.92 |

| Yes | 71 (71%) | 29 (29%) | - |

| Congestive heart failure | |||

| No | 493 (70%) | 216 (30%) | 0.052 |

| Yes | 273 (75%) | 90 (25%) | - |

| Diabetes mellitus | |||

| No | 587 (71%) | 240 (29%) | 0.53 |

| Yes | 179 (73%) | 66 (27%) | - |

| Hepatic insufficiency | |||

| No | 722 (71%) | 297 (29%) | 0.06 |

| Yes | 44 (83%) | 9 (17%) | - |

| Major Trauma | |||

| No | 733 (71%) | 299 (29%) | 0.11 |

| Yes | 33 (82%) | 7 (18%) | - |

| Cancer | |||

| No | 732 (71%) | 299 (29%) | 0.10 |

| Yes | 34 (83%) | 7 (17%) | - |

| Myocardial infarction (history) | |||

| No | 606 (72%) | 238 (28%) | 0.63 |

| Yes | 160 (70%) | 68 (30%) | - |

| Myocardial infarction (this admission) | |||

| No | 558 (71%) | 225 (29%) | 0.82 |

| Yes | 208 (72%) | 81 (28%) | - |

| Renal insufficiency | |||

| No | 573 (69%) | 257 (31%) | 0.001 |

| Yes | 193 (80%) | 49 (20%) | - |

| Sepsis | |||

| No | 699 (71%) | 287 (29%) | 0.17 |

| Yes | 67 (78%) | 19 (22%) | - |

| Devices already in place at time of arrest | |||

| Mechanical ventilation | |||

| No | 384 (74%) | 138 (26%) | 0.15 |

| Yes | 384 (70%) | 168 (30%) | - |

| Invasive airway | |||

| No | 400 (73%) | 146 (27%) | 0.20 |

| Yes | 368 (70%) | 160 (30%) | - |

| Arterial catheter | |||

| No | 432 (72%) | 167 (28%) | 0.62 |

| Yes | 336 (71%) | 139 (29%) | - |

| Time of day of arrest | |||

| 7am to 2:59pm | 332 (67%) | 166 (33%) | <0.001 |

| 3pm to 10:59pm | 262 (74%) | 93 (26%) | - |

| 11pm to 5:59am | 148 (85%) | 27 (15%) | - |

| Day of Week | |||

| Weekday | 629 (71%) | 260 (29%) | 0.21 |

| Weekend | 140 (75%) | 46 (25%) | - |

| Patient type | |||

| Outpatient | 13 (72%) | 5 (28%) | 1.00 |

| Emergency Department | 37 (71%) | 15 (29%) | - |

| Other | 719 (72%) | 286 (28%) | - |

| Arrest location | |||

| General inpatient* | 74 (75%) | 25 (25%) | 0.002 |

| Outpatient† | 13 (81%) | 3 (19%) | - |

| Cardiac/Coronary Unit | 75 (73%) | 28 (27%) | - |

| ICU | 309 (78%) | 88 (22%) | - |

| OR / Coronary catheterization laboratory | 272 (65%) | 148 (35%) | - |

| Emergency Department | 26 (65%) | 14 (35%) | - |

| Illness category | |||

| Medical | |||

| Non-Cardiac | 104 (78%) | 30 (22%) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac | 257 (78%) | 74 (22%) | |

| Surgical | |||

| Non-Cardiac | 63 (74%) | 22 (26%) | |

| Cardiac | 345 (66%) | 180 (34%) | |

| Automated / mechanical chest compressions | |||

| No | 452 (71%) | 189 (29%) | 0.81 |

| Yes | 140 (71%) | 56 (29%) | - |

| Presenting Cardiac Rhythm | |||

| Asystole | 160 (76%) | 51 (24%) | <0.001 |

| PEA | 305 (76%) | 96 (24%) | - |

| Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia (pVT) | 63 (68%) | 30 (32%) | - |

| Ventricular Fibrillation (VF) | 110 (60%) | 74 (40%) | - |

| Palpable pulse initially | 79 (70%) | 34 (30%) | - |

| Any VF or pVT during arrest | |||

| No | 351 (72%) | 139 (28%) | 0.95 |

| Yes | 418 (71%) | 167 (29%) | - |

| Any return of spontaneous circulation during arrest | |||

| No | 215 (100%) | 1 (0%) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 552 (65%) | 302 (35%) | - |

| Total duration (minutes) before durable ROSC, median (IQR) | 44 (20, 80) | 23 (10, 44) | <0.001 |

| Induced hypothermia | |||

| No | 523 (67%) | 257 (33%) | 0.74 |

| Yes | 74 (65%) | 39 (35%) | - |

Abbreviations: IQR: interquartile range; ROSC: return of spontaneous circulation

Row percentages shown

Includes adults arresting in the newborn unit

such as ambulatory same day surgery units; includes rehabilitation.

Missing values by group: Race=3/0, Weight(kg)=401/154, Pre-existing condition-Hypoperfusion=3/0, -CVA or Neurologic Disorder=3/0, -CHF=3/0, -Diabetes Mellitus=3/0, -Hepatic Insufficiency=3/0, -Major Trauma=3/0, -Cancer =3/0, -History of MI=3/0, -MI this Hospitalization=3/0, -Renal Insufficiency=3/0, -Sepsis=3/0, Admission CPC=178/47, Devices -Mechanical Ventilation=1/0, Devices - Invasive Airway=1/0, Devices - Arterial Line=1/0, Time of Day of arrest=27/20, Compression method-Mechanical=177/61, Presenting rhythm status=52/21, Any ROSC=2/3, Total duration before durable ROSC=105/57, Induced Hypothermia= 172/10.

Survivors were more likely to arrest during 7am-2:59pm, compared to 3pm-10:59pm or 11pm - 6:59am (33% vs. 26% vs. 15%; p<0.001), and were more likely to be located in procedural areas such as the operating room or the coronary catheterization laboratory, or in the emergency department compared to general inpatient wards. There were no significant differences between survivors or non-survivors in the presence of pre-exiting invasive medical devices such as arterial lines or mechanical ventilation, or in the use of mechanical chest compression.

Mortality Prediction

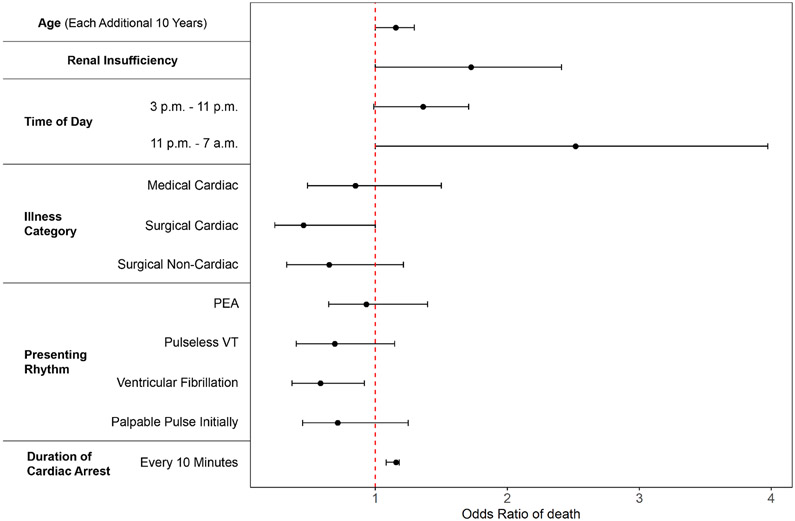

Among factors initially associated with mortality in univariate analysis, six remained in the final multivariable model (Figure 2, Supplement) which included age, pre-existing renal insufficiency, off-hours arrest (3pm – 6:59am), non-cardiac surgical patient type or medical patient type, initial arrest rhythm, and increasing duration of arrest. The model had good discrimination with an area under the curve [AUC]) of 0.719 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.680, 0.757), implying that the score could predict mortality with 72% accuracy. The above variables were combined to develop a score to predict hospital survival (Table 2), the Resuscitation Using ECPR during In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest (RESCUE-IHCA) Score. Points are assigned according to the six variables, from −15 ranging up to >40. A higher number of points correspond to a higher probability of death, which ranged from 0.22 to 0.99 (Figure 3). The summed points from each of the six variables would be used to determine the probability of death for a patient with IHCA treated with ECMO. Model calibration, to show how accurately the model fits the observed data, indicated acceptable fit (Hosmer and Lemeshow Goodness of Fit p=0.079)(Figure 4). As Goodness of Fit can change with different bin sizes, other sizes were tested without improvement in fit. Likewise, restriction of the data to 2010-2018 did not change model fit (AUC 0.719 [95% CI 0.671, 0.767]).

Figure 2: Adjusted odds of individual risk factors with death.

Adjusted association (odds ratio of death) for individual patient factors retained the multivariate mortality prediction model.

Table 2:

Score Calculation

| Points | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ≤20 | 2 |

| Each additional 10 | +2 | |

| Pre-existing renal insufficiency | Yes | +8 |

| Time of day | 3pm - 10:59pm | +4 |

| 11pm - 6:59am | +13 | |

| Illness category | Medical Cardiac | −2 |

| Surgical Cardiac | −11 | |

| Surgical Non-Cardiac | −6 | |

| Presenting rhythm | PEA | −1 |

| pVT | −5 | |

| VF | −8 | |

| Palpable pulse initially | −5 | |

| Duration of cardiac arrest | Each 10 minutes | +2 |

Abbreviations: PEA: pulseless electrical activity

pVT: pulseless ventricular tachycardia

VF: ventricular fibrillation

Figure 3: Predicted probability of death across points.

Curve with 95% CI shading showing the association between score points and mortality of in-hospital death, among the derivation cohort.

Abbreviations: CI—confidence interval

Figure 4: Calibration Plot of Observed (Y Axis) versus Predicted (X Axis) Mortality from Derivation dataset (Get With The Guidelines®-R).

Discrimination and calibration of the model among 1,075 patients from the AHA GWTG-R registry. Correlation between observed mortality the AHA GWTG-R dataset (Y axis) vs predicted mortality according to the RESCUE-IHCA mortality prediction score (X axis), in the derivation dataset. A p value greater than 0.05 indicates acceptable fit.

External Validation

The predictive model was externally validated within 297 adult patients from the ELSO registry who received ECMO for their cardiac arrest and met criteria for analysis (Supplement). Patients were well matched on characteristics (Table 3) including survival, age, time of day of arrest, and duration of event. Despite differences in the characteristics of the validation cohort, the model discrimination was only marginally lower with an AUC of 0.676 (95% CI: 0.606, 0.746) compared to the derivation cohort. Model calibration likewise indicated acceptable fit (Hosmer and Lemeshow Goodness of Fit p=0.66) (Figure 5). Other bin sizes were likewise tested without improvement in fit.

Table 3:

Comparison of derivation and validation patient characteristics.

| Variable* | Derivation (N=1075) |

Validation (N=297) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age† | 60.0 (48.0, 71.0) | 59.1 (48.3, 68.3) | 0.58 |

| Race | |||

| White | 796 (74%) | 155 (52%) | <0.001 |

| Non-white | 276 (25.7%) | 142 (48%) | - |

| Initial Rhythm | |||

| Asystole | 211 (21%) | 24 (9%) | <0.001 |

| PEA | 401 (40%) | 114 (41%) | - |

| Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia | 93 (9%) | 34 (12%) | - |

| Ventricular Fibrillation | 184 (18%) | 75 (27%) | - |

| Palpable pulse initially | 113 (11%) | 32 (12%) | - |

| Time of day of arrest | |||

| 7am to 2:59pm | 498 (48%) | 138 (47%) | 0.73 |

| 3pm to 10:59pm | 355 (35%) | 110 (37%) | - |

| 11pm to 6:59am | 175 (17%) | 49 (17%) | - |

| Pre-existing conditions | |||

| Congestive heart failure | 363 (34%) | 80 (27%) | 0.024 |

| Renal insufficiency | 242 (23%) | 76 (26%) | 0.28 |

| Preceding hypoperfusion | 468 (44%) | 271 (91%) | <0.001 |

| Duration of event, minutes† | 36.0 (17.0, 69.0) | 41.0 (27.0, 60.0) | 0.15 |

| Patient Type | |||

| Medical Noncardiac | 134 (13%) | 66 (22%) | <0.001 |

| Medical Cardiac | 331 (31%) | 44 (15%) | - |

| Surgical Cardiac | 525 (49%) | 138 (47%) | - |

| Surgical Non-cardiac | 85 (8%) | 49 (17%) | - |

| Sustained ROSC | 854 (80%) | 91 (31%) | <0.001 |

| Died | 769 (72%) | 214 (72%) | 0.86 |

Abbreviations: IQR-interquartile range; PEA-Pulseless electrical activity; ROSC-return of spontaneous circulation

Missing values by group: Race=3/0, Initial rhythm=73/18, Time of day=47/0, CHF=3/0, Renal insufficiency=3/0, Hypoperfusion=3/0, Duration of event=162/0, ROSC=5/0.

number (%) unless indicated

Median, Interquartile range (IQR)

Figure 5: Calibration Plot of Observed (Y Axis) versus Predicted (X Axis) Mortality from Validation dataset (Extracorporeal Life Support Organization).

Discrimination and calibration from external validation among 297 cardiac arrest patients treated with ECMO/ECPR from the ELSO Registry. Correlation between observed mortality the ELSO dataset (Y axis) vs predicted mortality according to the RESCUE-IHCA mortality prediction score (X axis), in the external validation dataset. A p value greater than 0.05 indicates acceptable fit.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis excluding patients who arrested in the operating room excluded age as a predictive variable but was otherwise unchanged with a similar AUC and acceptable calibration for both derivation and validation datasets (Supplement).

DISCUSSION

In this large study of hospitalized patients in the United States who sustained IHCA and were treated with ECPR, we identified six patient or arrest characteristics that were strongly associated with in-hospital mortality. These characteristics were combined to create the RESUCUE-IHCA score, a simple and easy to calculate score comprising only 6 variables; 5 of these variables can be known from the patient’s history—without laboratory values. The RESCUE-IHCA can be used to determine an individual patient’s estimated risk of mortality with good discrimination (AUC of 0.72) and calibration. The score was then externally validated in a separate cohort of 297 patients in the ELSO registry who received ECPR for IHCA. The calibration and validation values of the model show that the score can predict the probability of death with 72% accuracy. The score is simple and rapid enough to be used by clinicians at the beside.

Over the past decade, there has been a growing interest in the use of ECMO for adult cardiopulmonary failure, and cardiogenic shock after myocardial infarction (17-20). Although scores to predict outcome in patients receiving ECMO have been previously reported, a vast majority of them are for patients receiving ECMO for non-arrest indications (e.g., cardiogenic shock, severe respiratory failure) (9,10). Many require more variables and were not designed for ECPR (9,21,22); others lack external validation (23) or have a lower accuracy (22,24,25). In 2020, Okada et al analyzed 916 patients with OHCA (23). The Okada score had accuracy and comparable to our RESCUE-IHCA score (AUC 0.724 vs 0.719), but requires obtaining a laboratory value (pH) and external validation was not performed. Other scores from small sample sizes report high accuracy, but lack validation and may be overfitted (26). External validation of prediction models on an external dataset is important as it reflects the model’s ability to generalize and is advised by best practice (27). Models that are internally validated may be over optimistic or overfit (27,28). The RESCUE-IHCA score was derived from a large sample size of >1,000 adults from >200 hospitals treated with ECPR from a national dataset. The score externally validated across an international dataset of adults treated with ECPR for IHCA with good discrimination and calibration.

The RESCUE-IHCA score fills an important gap in the literature, as the first large externally validated mortality prediction score for IHCA patients treated with ECPR. The RESCUE-IHCA score enables a clinician to estimate at the bedside in real-time, with 72% accuracy, a probability of death ranging from 22% to >99% using patient characteristics known at the time of cardiac arrest, and without waiting for laboratory values. Moreover, we found that five of the variables associated with survival were related to the conditions of the arrest or to the patient (age, patient type, history of renal insufficiency, time of day and initial rhythm), whereas only one was a potentially modifiable intra-arrest feature (duration of arrest). This suggests that much of the probably of survival can be known based on fixed characteristics of the patient and their arrest.

A striking finding is the influence of time of day on survival, with nocturnal ECPR conferring mortality risk comparable to renal insufficiency and older age. We previously demonstrated that US patients were more likely to receive ECPR for IHCA during daytime hours (5), reflecting increased staff during the day. As such, this increased observed mortality at night may simply reflect decreased nighttime in-house staff. We have previously shown that multiple specialties are involved in the care of ECPR patients (29), and that post-arrest care is strongly correlated with survival (30), both of which may be more limited at night. These suggest that efforts to provide comparable levels of care at night for ECPR patients could improve survival. We note that the survival of patients during the weekend was 4% lower than during the weekday, which is the same as observed in previous analyses of cardiac arrest (31), but not significant in our sample size, compared to the 15% improved daytime survival compared to night. Alternatively, the lower survival at night vs weekend may reflect slower psychomotor skills for his complex procedure, as has been suggested (32).

Although the RESCUE-IHCA score had modest calibration and discrimination, it was comparable to other scores derived from large registries for both ECMO without cardiac arrest, and for cardiac arrest without ECMO (33-36). The SAVE score for cardiogenic shock treated with ECMO had an AUC of 0.68, while the RESP score for respiratory failure treated with ECMO had an AUC of 0.74 (9,21). Many of the variables included in the RESCUE-IHCA score were also included in the CASPRI score, which was developed for predicting survival with favorable neurological outcome for IHCA patients (excluding ECMO) (37). However, the relative strength of association of individual variables with survival (e.g., age, initial rhythm, etc.) differs between the two scores, given the inherent differences in patients treated with ECMO/ECPR compared to IHCA patients not receiving these therapies (37). Many of the other scores require laboratory or other variables not routinely available for patients with OHCA treated with ECPR, a population in whom our score validated. Our finding of worse outcome with nocturnal ECPR is a new and important finding compared to previous ECMO scores.

We did note that the RESCUE-IHCA derivation cohort had a higher rate of ROSC (80% vs 31%) than the validation cohort, which is likely due to differences in definition of ROSC. Until 2015, the GWTG-R data collection form recorded any ROSC rather than ROSC sustained for longer than 20 minutes, as defined in ELSO and currently in the GWTG-R data.

A strength of the RESCUE-IHCA score is that it can be calculated readily using six pre- and intra-arrest variables, and does not include laboratory values; it is parsimonious compared to other survival prediction scores for either cardiac arrest or ECMO (9,21,22,37,38). We envision that the RESCUE-IHCA score would be of value to front line physicians. By providing objective data with an externally validated model regarding the probability of death, the RESCUE-IHCA score can help clinicians engage with patients/families as they navigate difficult decisions regarding goals of care in this resource intensive, high risk and expanding population.

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of the following limitations. First, although GWTG-R includes rich data on patient and cardiac arrest variables, data on variables such as quality of CPR prior to ECMO canulation, laboratory values (e.g., serum pH, lactate) etc. which may be strongly associated with survival in this population were not available. Second, we chose to predict hospital survival rather than neurologically intact survival. The GWTG-R data have a high proportion of missing neurologic status, which has been increasing in recent years. By choosing hospital mortality as our outcome, we were able to externally validate our score—a critical step; additionally, we observed that within our dataset, >85% of survivors had good neurologic outcomes recorded. This is consistent with the majority of other studies of adult ECPR, though is a limitation we acknowledge, and future studies could examine neurologically intact survival as a relevant outcome. Our dataset was of IHCA, and as such, a large portion of our patients were cardiac surgical patients. While this may be considered a limitation, we have previously shown that this reflects the population in whom ECPR is used for IHCA in the US (5). Further, the validation dataset from ELSO—the largest ECMO and ECPR registry in the world—reflected this patient type distribution also, suggesting our model is well suited to the way in which ECPR has historically been used.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we developed and externally validated the RESCUE-IHCA score, a simple score that can be used at bedside to determine the probability of mortality in adult IHCA patients treated with ECPR.

Supplementary Material

Central Illustration: RESCUE-IHCA Score to predict hospital mortality for adult ECPR.

The probability of hospital mortality for adult ECPR can be accurately predicted with the RESCUE-IHCA Score using five pre-existing patient factors (age, time of day, initial rhythm, history of renal insufficiency, and patient type (cardiac versus non-cardiac and medical versus surgical)), and one intra-arrest factor (duration of the cardiac arrest event). The score predicts the probability of mortality (ranging from 22-99%) with 72% accuracy and is externally validated with similar performance.

PERSPECTIVES.

WHAT IS KNOWN?

No multi-center study with external validation has examined predictors of survival/mortality for adult ECPR.

WHAT IS NEW?

The probability of death after IHCA treated with ECPR / ECMO can be rapidly predicted with good accuracy using only six patient and arrest characteristics without laboratory values: age, time of day, initial rhythm, history of renal insufficiency, patient type (cardiac versus non-cardiac and medical versus surgical), and duration of the cardiac arrest event. The RESCUE-IHCA Score is externally validated in the ELSO dataset with comparable accuracy.

WHAT IS NEXT?

The RESCUE-IHCA could be applied to patients with OHCA and modified using pre-arrest laboratory values to see how these influence score accuracy.

Dislcosures/funding:

Dr. Tonna was supported by a career development award (K23HL141596) from the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Tonna received speakers fees and travel compensation from LivaNova and Philips Healthcare, unrelated to this work. This study was also supported, in part, by the University of Utah Study Design and Biostatistics Center, with funding in part from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant UL1TR002538 (formerly 5UL1TR001067-05, 8UL1TR000105 and UL1RR025764). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. None of the funding sources were involved in the design or conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data, or preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

None of the authors report any conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- AHA GWTG-R

American Heart Association Get With The Guidelines—Resuscitation

- ECPR

extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- ELSO

Extracorporeal Life Support Organization

- IHCA

in-hospital cardiac arrest

- IQR

interquartile range

- MI

myocardial infarction

- OHCA

out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

- ROSC

return of spontaneous circulation

- VF

ventricular fibrillation

- pVT

pulseless ventricular tachycardia

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Richardson AS, Schmidt M, Bailey M, Pellegrino VA, Rycus PT, Pilcher DV. ECMO Cardio-Pulmonary Resuscitation (ECPR), trends in survival from an international multicentre cohort study over 12-years. Resuscitation 2017;112:34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yannopoulos D, Bartos J, Raveendran G et al. Advanced reperfusion strategies for patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and refractory ventricular fibrillation (ARREST): a phase 2, single centre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D'Arrigo S, Cacciola S, Dennis M et al. Predictors of favourable outcome after in-hospital cardiac arrest treated with extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation 2017;121:62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stub D, Bernard S, Pellegrino V et al. Refractory cardiac arrest treated with mechanical CPR, hypothermia, ECMO and early reperfusion (the CHEER trial). Resuscitation 2015;86:88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tonna JE, Selzman CH, Girotra S et al. Patient and Institutional Characteristics Influence the Decision to Use Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation for In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9:e015522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tonna JE, Selzman CH, Mallin MP et al. Development and Implementation of a Comprehensive, Multidisciplinary Emergency Department Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Program. Ann Emerg Med 2017;70:32–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bharmal M, Venturini JM, Chua RFM et al. Cost-Utility of Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Patients with Cardiac Arrest. Resuscitation 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen ML, Gause E, Mills B et al. Traumatic and hemorrhagic complications after extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt M, Burrell A, Roberts L et al. Predicting survival after ECMO for refractory cardiogenic shock: the survival after veno-arterial-ECMO (SAVE)-score. European Heart Journal 2015;36:2246–2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt M, Pham T, Arcadipane A et al. Mechanical Ventilation Management during Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. An International Multicenter Prospective Cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019;200:1002–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldberger ZD, Chan PS, Berg RA et al. Duration of resuscitation efforts and survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest: an observational study. Lancet 2012;380:1473–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin JW, Wang MJ, Yu HY et al. Comparing the survival between extracorporeal rescue and conventional resuscitation in adult in-hospital cardiac arrests: propensity analysis of three-year data. Resuscitation 2010;81:796–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bembea MM, Ng DK, Rizkalla N et al. Outcomes After Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation of Pediatric In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Report From the Get With the Guidelines-Resuscitation and the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registries. Crit Care Med 2019;47:e278–e285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schomaker M, Heumann C. Model selection and model averaging after multiple imputation. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis 2014;71:758–770. [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. 2011 2011;45:67. [Google Scholar]

- 16.H D Jr, L S, RX S. Applied Logistic Regression. 3rd ed. New York: Wiley, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Acharya D, Torabi M, Borgstrom M et al. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in Myocardial Infarction Complicated by Cardiogenic Shock: Analysis of the ELSO Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:1001–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guglin M, Zucker MJ, Bazan VM et al. Venoarterial ECMO for Adults: JACC Scientific Expert Panel. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:698–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeFilippis EM, Clerkin K, Truby LK et al. ECMO as a Bridge to Left Ventricular Assist Device or Heart Transplantation. JACC Heart Fail 2021;9:281–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schrage B, Burkhoff D, Rübsamen N et al. Unloading of the Left Ventricle During Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Therapy in Cardiogenic Shock. JACC: Heart Failure 2018;6:1035–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmidt M, Bailey M, Sheldrake J et al. Predicting survival after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory failure. The Respiratory Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Survival Prediction (RESP) score. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2014;189:1374–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Becher PM, Twerenbold R, Schrage B et al. Risk prediction of in-hospital mortality in patients with venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for cardiopulmonary support: The ECMO-ACCEPTS score. J Crit Care 2019;56:100–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okada Y, Kiguchi T, Irisawa T et al. Development and Validation of a Clinical Score to Predict Neurological Outcomes in Patients With Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Treated With Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2022920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muller G, Flecher E, Lebreton G et al. The ENCOURAGE mortality risk score and analysis of long-term outcomes after VA-ECMO for acute myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock. Intensive care medicine 2016;42:370–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen WC, Huang KY, Yao CW et al. The modified SAVE score: predicting survival using urgent veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation within 24 hours of arrival at the emergency department. Crit Care 2016;20:336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee SW, Han KS, Park JS, Lee JS, Kim SJ. Prognostic indicators of survival and survival prediction model following extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation in patients with sudden refractory cardiac arrest. Ann Intensive Care 2017;7:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leisman DE, Harhay MO, Lederer DJ et al. Development and Reporting of Prediction Models: Guidance for Authors From Editors of Respiratory, Sleep, and Critical Care Journals. Crit Care Med 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, Moons KG, Group T. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. The TRIPOD Group. Circulation 2015;131:211–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tonna JE, Johnson NJ, Greenwood J et al. Practice characteristics of Emergency Department extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (eCPR) programs in the United States: The current state of the art of Emergency Department extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ED ECMO). Resuscitation 2016;107:38–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tonna J, Selzman C, Bartos J et al. Abstract 117: Critical Care Management, Hospital Case Volume, and Survival After Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Circulation 2020;142:A117–A117. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peberdy MA, Ornato JP, Larkin GL et al. Survival from in-hospital cardiac arrest during nights and weekends. JAMA 2008;299:785–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Indik JH. Is it Like Night and Day, or Weekend? J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:412–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gräsner J-T, Meybohm P, Fischer M et al. A national resuscitation registry of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Germany—A pilot study. Resuscitation 2009;80:199–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu N, Ong MEH, Ho AFW et al. Validation of the ROSC after cardiac arrest (RACA) score in Pan-Asian out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients. Resuscitation 2020;149:53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thai TN, Ebell MH. Prospective validation of the Good Outcome Following Attempted Resuscitation (GO-FAR) score for in-hospital cardiac arrest prognosis. Resuscitation 2019;140:2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ebell MH, Jang W, Shen Y, Geocadin RG, Get With the Guidelines-Resuscitation I. Development and validation of the Good Outcome Following Attempted Resuscitation (GO-FAR) score to predict neurologically intact survival after in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1872–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan PS, Spertus JA, Krumholz HM et al. A validated prediction tool for initial survivors of in-hospital cardiac arrest. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:947–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ji C, Brown TP, Booth SJ et al. Risk Prediction Models for Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Outcomes in England. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.