Abstract

Enzymes with phospholipase C activity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis have been recently described. The three genes encoding these proteins, plcA, plcB, and plcC, are located at position 2351 of the genomic map of M. tuberculosis H37Rv and are arranged in tandem. We have previously described the presence of variations in the restriction fragment length polymorphism patterns of the plcA and plcB genes in M. tuberculosis clinical isolates. In the present work we investigated the origin of this polymorphism by sequence analysis of the phospholipase-encoding regions of 11 polymorphic M. tuberculosis clinical isolates. To do so, a long-PCR assay was used to amplify a 5,131-bp fragment that contains the plcA and plcB genes and part of the plcC gene. In the M. tuberculosis strains studied the production of an amplicon ∼1,400 bp larger than anticipated was observed. Sequence analysis of the PCR products indicated the presence of a foreign sequence that corresponded to an IS6110 element. We observed insertion elements in the plcA, plcB, and plcC genes. One site in plcB had the highest incidence of transposition (5 out of 11 strains). In two strains the insertion element was found in plcA in the same nucleotide position. In all the cases, IS6110 was transposed in the same direction. The high level of transposition in the phospholipase region can lead to the excision of fragments of genomic DNA by recombination of neighboring IS6110 elements, as demonstrated by finding the deletion, in two strains, of a 2,837-bp fragment that included plcA and most of plcB. This can explain the negative results obtained by some authors when detecting the mtp40 sequence (plcA) by PCR. Given the high polymorphism in this region, the use of the mtp40 sequence as a genetic marker for M. tuberculosis sensu stricto is very restricted.

The mtp40 gene was first described as a 402-bp open reading frame (ORF) encoding a 13.8-kDa specific protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (21). This gene was cloned in a 3.1-kbp BamHI fragment, and, after sequencing the whole insert, Leão et al. noted the presence of an ORF of 1,170 bp and the beginning of another (15). Johansen et al. (13) completely sequenced the second ORF, and they also demonstrated in vitro that these genes encode phospholipase C activities. They named the ORFs mpcA and mpcB. The sequence called mtp40 actually constitutes only a part of the mpcA gene. After the whole M. tuberculosis H37Rv genome was sequenced, two more phospholipase genes were decribed: an ORF beside mpcB and another related sequence at position 1755 of the genome, located beside an IS6110 element (4). From this point on these genes were designated plc (phospholipase C) genes; the three ORFs arranged in tandem were called plcA, plcB, and plcC, and the fragment at position 1755 in M. tuberculosis H37Rv was called plcD. We use this nomenclature in the present work.

Since there have been conflicting results concerning the presence of the mtp40 sequence in the M. tuberculosis complex, we previously studied its distribution within a collection of M. tuberculosis clinical isolates. PCR amplification of the mtp40 region revealed that some strains were negative for this sequence (28). To rule out the presence of mutations or deletions in the primer annealing sites that cause a false-negative result, we carried out Southern blot assays using the PvuII enzyme and a PCR product corresponding to mtp40 as a probe. We observed that M. tuberculosis H37Rv and H37Ra presented two bands: one of 0.75 kbp, which we demonstrated to correspond to plcA, and one of 2.1 kbp that corresponds to plcB and that cross-reacts with the probe for mtp40 (which is part of plcA). We also found strains presenting variations of this pattern, showing extra bands or a shift in the molecular weight of the band corresponding to the plcB gene from 2.1 to 2.5 kbp (28). Some other clinical isolates presented changes in both bands or were negative in the Southern blot analysis.

To explain the changes in the restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) patterns, in this work we studied by long PCR the phospholipase-encoding regions of selected strains followed by sequence analysis of the amplicons.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Most of the M. tuberculosis strains used in this study were obtained from the National Reference Centre for Tuberculosis of the Laboratories for Health Canada (Winnipeg, Canada) and were identified by conventional methods. All the strains were maintained at −70°C in skim milk and subcultured on Lowenstein-Jensen medium when needed. DNA samples from two strains, which we named RIVM-7 and RIVM-13 were kindly donated by Kristin Kremer from the National Institute of Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), Bilthoven, The Netherlands (14).

Genomic-DNA extraction.

The mycobacteria were heat killed at 85°C for 30 min, and the DNA was extracted in accordance with a technique using cetyltrimethyammonium bromide-NaCl (31). The DNA was suspended in Tris-EDTA buffer, quantified, and stored at 4°C until use.

Southern blot assay.

For Southern blotting of clinical isolates, 2 μg of genomic DNA was digested with 5 U of PvuII (28) for 4 h at 37°C. The electrophoretic separation of the digested fragments was done in a 20- by 25-cm 0.8% agarose gel by applying 30 V overnight. After electrophoresis, the DNA samples were transferred to a nylon membrane using the Turboblotter system (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, N.H.) in accordance with the manufacturer's directions. The blot was prehybridized and then probed overnight at 42°C with peroxidase-labeled amplicons prepared with the enhanced chemiluminescence kit (ECL; Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.). Hybridization, washing, and development of the filters were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions.

As a probe we used a PCR product with primers PT1 and PT2, which amplify a region of plcA (6). To determine the phylogenetic relationships among some of the studied strains that presented identical insertions, we incubated the blots with a PCR probe derived from primers INS-1 and INS-2, which amplify a fragment of 243 bp in the IS6110 right arm.

Synthesis of oligonucleotide primers and sequence analysis of the amplicons.

The oligonucleotides used in this study (Table 1) were prepared on a 392 DNA-RNA synthesizer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) utilizing the standard phosphoramidite method. The sequences of the PCR products were determined with the Prism Dye Terminator sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems) in an ABI 377 automated sequencer.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this work

| Primer | Sequence | Nucleotides |

|---|---|---|

| TB20 | 5′ CGC AGC AAC ACC CTT ATC AAG T | 19275–19296a |

| TB21 | 5′ GTG ATT GTC GGC GAA ATG AAG T | 24406–24385a |

| TB25 | 5′ CTC CGG CGG GTA CCT CCT CG | 90–71b |

| TB26 | 5′ AGG CTG CCT ACT ACG CTC AAC G | 1272–1293b |

| INS-1 | 5′ CGT GAG GGC ATC GAG GTG GC | 633–652c |

| INS-2 | 5′ CGT AGG CGT CGG TGA CAA A | 876–858c |

Long-PCR assay.

To determine the genetic changes that lead to the polymorphism in the phospholipase region, we designed a pair of primers located 1,000 bp outwards of the plcA or plcB genes, which we called TB20 and TB21, respectively (Table 1). The predicted size of the amplicon was 5,131 bp. The PCR assay was carried out with 100 ng of genomic DNA in a PTC-200 thermocycler (MJ Research, Watertown, Mass.) by utilizing PCR assay kit XL (Perkin-Elmer) under the following conditions: 94°C for 2 min and 10 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 4 min. A second round of 20 cycles was carried out at 94°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 4 min, adding 20 s every cycle. A final extension step at 68°C for 10 min was performed. The PCR products were applied to a 0.8% low-melting-point agarose gel, and after the electrophoresis the gel slices containing the bands were excised and purified utilizing the GeneClean III (BIO 101, Inc., Vista, Calif.) kit. The DNA was quantified spectrophotometrically and stored at 4°C.

RESULTS

Southern blot analysis with PT1 and PT2.

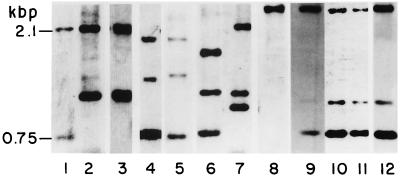

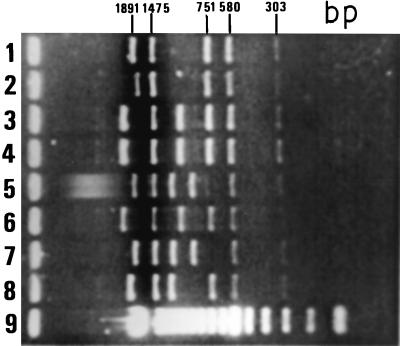

The Southern blot patterns of the strains with the plcA probe used in this study are presented in Fig. 1. According to the restriction map of the region (not shown), the 0.75-kbp band corresponds to the plcA gene; the 2.1-kbp band corresponds to plcB and part of plcC. In Fig 1, we observe that strains in lanes 4 to 6 and 8 to 12 lack the 2.1-kbp band corresponding to plcB; instead they have bands of different sizes. Strains in lanes 2, 3, 7, and 8 lack the 0.75-kbp band that corresponds to the plcA gene. Strains 9 to 12 present identical RFLP patterns, with a band of 2.5 kbp instead of the normal plcB band of 2.1 kbp, as well as another band of about 1.0 kbp and the 0.75-kbp band. By using a probe for plcB we observed that the 2.5-kbp band corresponds to this gene (data not shown). The strain in lane 8 presents only a band of about 2.8 kbp. As a control (lane 1) we used the M. tuberculosis 14323 strain, kindly donated by J. D. A. van Embden, which is used worldwide as a control for IS6110 studies.

FIG. 1.

Southern blot analysis of the M. tuberculosis strains studied in this work. The blots were incubated with a PCR probe, prepared with primers PT1 and PT2 as described before (28), that amplifies a 396-bp region near the 3′ end of the plcA ORF. Lanes: 1, M. tuberculosis strain 14323; 2, Dr-561; 3, RIVM-7; 4, RIVM-13; 5, Dr-351; 6, Dr-468; 7, Dr-194; 8, Dr-494; 9, Dr-116; 10, Dr-169; 11, Dr-170; 12, Dr-342.

Sequencing analysis of the TB20-TB21 amplicons.

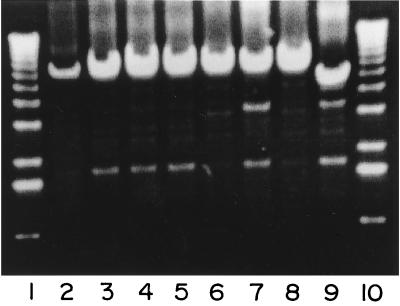

When amplifying genomic DNA from the polymorphic clinical isolates with primers TB20 and TB21, we observed the presence of amplicons bigger than those produced by control strain M. tuberculosis H37Rv (Fig 2). Other bands of less intensity were also observed. After sequencing analysis of some of these bands we concluded that they corresponded to less-specific annealing sites for the primers. First, we did the sequencing analysis with primers TB20 and TB21 and observed in one strain an IS6110 element at the end of an amplicon produced with TB20 and TB21 (TB20-TB21 amplicon). To simplify the analysis, we then performed the sequencing analysis using primers TB25 and TB26, which anneal to a region close to the end of the IS6110 sequence. These primers are directed outward in such way that, when performing the sequencing PCR, we could detect the insertion site in one run.

FIG. 2.

Long-PCR assay of mycobacterial genomic DNA from polymorphic strains for the phospholipase genes with primers TB20 and TB21. Lanes: 1 and 10, 1-kb ladder (Gibco); 2, RIVM-7; 3, Dr-169; 4, Dr-170; 5, Dr-342; 6, Dr-351; 7, Dr-561; 8, Dr-468; 9, M. tuberculosis H37Rv.

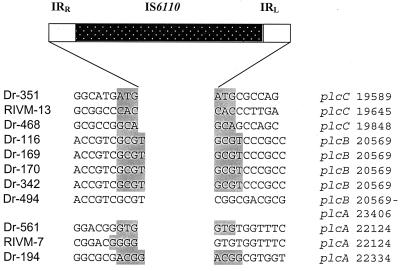

In Fig. 3 we describe the sequences at the junction between the insertion elements and the genomic mycobacterial DNA. We observed the duplication of three or four nucleotides at the site of the transposition. Interestingly in strain RIVM-7 there is only the duplication of two nucleotides and the duplicated nucleotides remained on one side of IS6110. These results were confirmed by preparing the amplicons and performing the sequencing analysis in duplicate.

FIG. 3.

Locations of the IS6110 elements inserted in the phospholipase regions of the M. tuberculosis strains studied in this work. At the right are positions of the insertion elements in the phospholipase locus. Shaded boxes, duplicated nucleotides. The nucleotide numbers are taken from GenBank sequence MCTY 98 (accession no. Z83860). For comparison purposes, sequence data from strain Dr-194, which have been published before, are shown (28). IRR and IRL, right and left imperfect repeats, respectively.

Instead of producing an amplicon bigger than that from M. tuberculosis H37Rv with TB20 and TB21, a smaller PCR fragment was obtained in strains Dr-494 and Dr-426. By sequencing analysis we observed, in both strains, that the right imperfect repeat of IS6110 was anchored on nucleotide 20569 (plcB gene) and that the left repeat was anchored on nucleotide 23406 (plcA), with the loss of a 2,837-bp fragment (Fig. 3). Interestingly no direct repeats were found at the ends of the IS6110 elements. These sequence analysis findings were corroborated by digestion of the TB20-TB21 amplicon with PvuII (data not shown), as mentioned below.

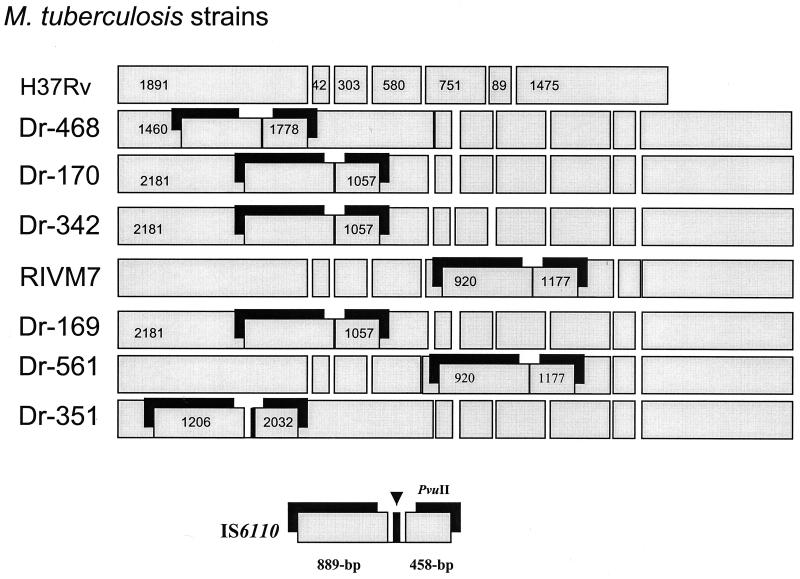

To confirm that the changes in the Southern blot patterns are only due to the insertion of the IS6110 element, we gel purified the amplicons and digested them with PvuII. In Fig. 4 we show the map with the predicted changes as well as the electrophoretic separation of the digested amplicons. In all the cases there was concordance between the expected and the obtained fragments.

FIG. 4.

Internal PvuII restriction sites of the TB20-TB21 amplicon. (Top) Map of the expected fragments obtained from amplicons derived from M. tuberculosis H37Rv strain and some of the polymorphic strains according to the PvuII restriction sites and the position of the inserted IS6110 element in each strain. (Bottom) A 1.5% agarose gel with the digested amplicons. Lanes: 1, M. tuberculosis H37Rv; 2, Dr-468; 3, Dr-170; 4, Dr-342; 5, RIVM-7: 6, Dr-169; 7, Dr-561; 8, Dr-351; lane 9, 100-bp ladder (Gibco). Molecular sizes of the fragments obtained from M. tuberculosis H37Rv are at the top.

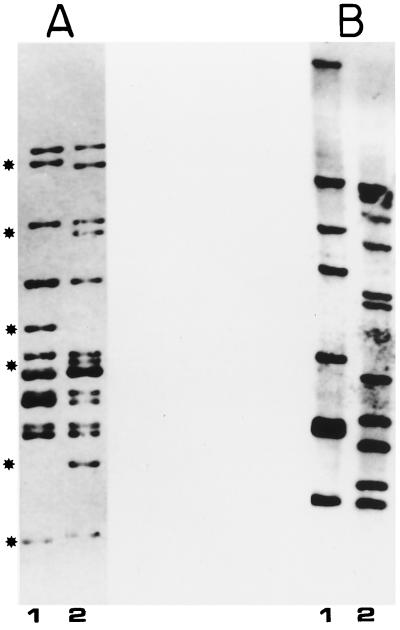

Since one explanation of the selection of the same insertion site could be that the strains actually belong to the same clone, we analyzed the RFLPs for IS6110 in those strains showing identical insertion sites. In Fig. 5A we show the Southern blot analysis of two of the most closely related strains. Both are isolates from British Columbia, Canada, and present nine similar bands. It is possible they have the same ancestor. On the other hand, although strain RIVM-7 from Mongolia and strain Dr-561 from Alberta, Canada (Fig. 5B), have the IS6110 element inserted in the same nucleotide position in plcA, they seem to be unrelated.

FIG. 5.

Southern blot analysis of some of the M. tuberculosis polymorphic strains showing identical insertion sites probed with an IS6110 right-arm PCR probe. (A) Lane 1, Dr-169; lane 2, Dr-170. (B) Lane 1, Dr-561; lane 2, RIVM-7.

In all the strains studied in this work we found the IS6110 elements transposed in the same direction.

DISCUSSION

IS6110 has a 1,361-bp sequence with a 28-bp imperfect repeat at the ends (25, 26). This insertion element belongs to the IS3 family of mobile elements and is widely distributed in the M. tuberculosis complex members. IS6110 polymorphism is currently used as a genetic target to differentiate individual clones of M. tuberculosis, because they can contain from 0 to 25 copies distributed in the entire genome (20, 27). Although it is considered that IS6110 transposes randomly, it is rarely found in the first quarter of the M. tuberculosis H37Rv circular map (4), which indicates a certain form of selection of the insertion sites. This is demonstrated also by the observation of “hot spots” for IS6110 transposition in several sites. The first is the direct repeat locus, which is composed of directly repeated sequences of 36 bp separated by nonrepetitive segments of 36 to 41 bp (12). Other high-frequency locations of IS6110 are the ipl locus, which is itself located in an insertion element-like element, IS1547 (7), and the DK1 site (10).

In this work we found IS6110 elements distributed along the phospholipase region; however this distribution was not random. It seems likely that even in the phospholipase genes there are preferential sites for the IS6110 insertion, such as nucleotides 20569 and 22124. In M. tuberculosis H37Rv and H37Ra there is an IS6110 interruption of the plcD gene (2), and other M. tuberculosis strains demonstrate similar insertion elements at the identical position (22). These data support the idea that there are hot spots, which exist in the M. tuberculosis genome and within the phospholipase genes specifically, that attract IS6110 insertion elements. Only by doing a study involving a great number of strains bearing IS6110 elements can we determine if there are consensus sequences within the phospholipase genes that stimulate IS6110 transposition.

During transposition, 3 or 4 bp of the DNA sequence at the insertion site is duplicated by the repair and filling mechanisms of the nick produced during this event (24). In the amplicon derived from RIVM-7 DNA, we did not observe direct repeats at the ends of the IS6110 element; instead we observed the duplication of two nucleotides in one of the sides. The absence of flanking direct repeats can be an indication of recombination mediated by insertion elements (16), which usually produces the deletion of the region between the elements. For RIVM-7 there was not such a deletion, which indicates the possible existence of other reparation or transposition mechanisms.

IS6110 transposition in high-preference sites such as the ipl locus has been found to produce the excision of neighboring DNA fragments (8, 9), possibly by homologous recombination between two adjacent IS6110 elements oriented in the same direction, as proposed by Fang et al. (9). Several regions of M. tuberculosis H37Rv (RvD2, RvD3, and RvD5 regions), ranging in size from 0.8 to 4 kbp (2), have also been attributed to DNA excised during IS6110 transposition. In a previous study (28) we observed that some strains did not hybridize with the probes for plcA and plcB. The excision of part of the phospholipase genes by IS6110 recombination can explain the lack of these genes in some M. tuberculosis strains described by us and others (29). Although initially the mtp40 sequence inside plcA was considered to exist only in M. tuberculosis, and thus was used to identify M. tuberculosis sensu stricto, it appears that these genes are very mobile and unstable, and this may restrict their clinical use as genetic markers.

Our data suggest that the phospholipase genes seem to attract IS6110 transposition. Thus the presence of an IS6110 element in two phospholipase genes at a time or in nearby genes (such as the neighboring cutinase or PE or PPE gene, all of which have also been found to attract IS6110 elements) (22) can produce excision and may lead to the loss of phospholipase sequences and, ultimately, function. This is also supported by the presence in M. tuberculosis H37Rv of a phospholipase gene (plcD) (4) that is interrupted by an IS6110 element. In the present study, two strains of M. tuberculosis were observed to produce 2.8-kbp excision fragments of the phospholipase genes. This could have been due to recombination of two IS6110 elements since, as mentioned above, IS6110 did not present direct repeats, and this is evidence of recombination between IS elements (16). It is possible that transposition of IS6110 elements mediates the mobilization or duplication of these genes, producing strains with no phospholipase genes, fragments of the genes, or extra bands produced by duplication, such as those strains belonging to group C (28). We are currently working on the characterization of the M. tuberculosis strains lacking the entire phospholipase locus; data from this work can help us to explain the mechanisms of the loss of DNA in this region.

The change in sequence divergence has been found useful in establishing and calibrating molecular clocks. Changes in the IS6110 pattern have been observed to occur over 1 or 2 years (3, 5). We observed in related M. tuberculosis strains minimal changes in the IS6110 patterns but radical changes in or the complete loss of the phospholipase genes (28). It is possible that environmental (11) or culture conditions may rapidly induce these changes in certain genomic areas, particularly in those where there are several IS6110 elements separated by small distances.

It has been claimed that phospholipases play an important role in virulence, either by producing tissue damage, as for the alfa toxin of Clostridium perfringens (30) or Pseudomonas aeruginosa phospholipase (19), or by allowing the escape of the microorganism from the phagolysosome to live freely in the macrophage cytoplasm (23). Recently, phospholipase C and D and sphingomyelinase activities have been detected in M. tuberculosis (13). M. tuberculosis phospholipase proteins resemble those encoded by P. aeruginosa plcH and plcS genes, which contribute to the virulence of this opportunistic lung pathogen. The phospholipase role in intracellular survival and as a virulence factor has been probed in vitro and in vivo by studying the effect of deletions of Listeria monocytogenes phospholipases encoded by plcA and plcB. Indeed a ΔplcA-plcB double mutant lost its ability to escape from the phagocyte and to spread from cell to cell (23). The production of hemolytic plaques of this microorganism was reduced to nearly 70% of that for the wild type and the mutant was 500-fold less virulent than wild-type bacteria in mice, which suggests a role for phospholipases as a virulence factor. It is possible that the M. tuberculosis cluster comprising plcA, plcB, and plcC can have a similar role in pathogenesis. It is important to note that M. bovis lacks this cluster of genes (1). The clinical diseases produced by M. tuberculosis and Mycobacterium bovis are indistinguishable. However, it has been observed that M. bovis has a decreased ability to reactivate and spread from person to person (18). Since phospholipase activity in other microorganisms has an important role in their virulence, it is possible that this activity confers to M. tuberculosis the ability to survive intracellularly in macrophages and therefore to grow and spread to other cells or tissues.

Recently, Miller and Shinnick (17) reported that Mycobacterium smegmatis cells complemented with PCR-generated plcA and plcB genes from M. tuberculosis did not show an increased rate of intracellular survival in THP-1 macrophages in comparison with wild-type bacteria. However, these results do not rule out a possible involvement of plc genes in the whole mechanism of pathogenesis of tuberculosis, as these genes may be involved in processes interacting with other factors present in M. tuberculosis but not in M. smegmatis, which is a limitation of that assay.

M. tuberculosis strains with naturally knocked out genes, such as those described in this paper, as well as strains lacking the complete cluster of phospholipase genes, can constitute a good model to study the role of these enzymes in M. tuberculosis pathogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Robert Vogrig, Claude Ouellette, and Shaun Tyler from the DNA Core Facility of the Federal Laboratories for Health Canada, Winnipeg, Canada, for their expert assistance in sequence analysis. Our thanks go to Juan Antonio Luna for his kind help in the preparation of the artwork.

This study was supported in part by the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT), México, grant no. 28697-M.

REFERENCES

- 1.Behr M A, Wilson M A, Gill W P, Salamon H, Schoolnik G K, Rane S, Small P M. Comparative genomics of BCG vaccines by whole-genome DNA microarray. Science. 1999;284:1520–1523. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5419.1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brosch R, Philip W J, Stavropoulos E, Colston M J, Cole S T, Gordon S V. Genomic analysis reveals variation between Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv and the attenuated M. tuberculosis H37Ra strain. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5768–5774. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5768-5774.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cave M D, Eisenach K D, Templeton G, Salfinger M, Mazurek G, Bates J H, Crawford J T. Stability of DNA fingerprint patterns produced with IS6110 in strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:262–266. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.1.262-266.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cole S T, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon S V, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry III C E, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Krogh A, McLean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver K, Osborne J, Quail M A, Rajandream M A, Rogers J, Rutter S, Seeger K, Skelton J, Squares R, Squares S, Sulston J E, Taylor K, Whitehead S, Barrel B G. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daley C L, Small P M, Schecter G F, Schoolnik G K, McAdam R A, Jacobs W R, Jr, Hopewell P C. An outbreak of tuberculosis with accelerated progression among persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:231–235. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199201233260404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Del Portillo P, Murillo L A, Patarroyo M E. Amplification of a species-specific DNA fragment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and its possible use in diagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2163–2168. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.10.2163-2168.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fang Z, Forbes K J. A Mycobacterium tuberculosis IS6110 preferential locus (ipl) for insertion into the genome. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:479–481. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.2.479-481.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang Z, Morrison N, Watt B, Doig C, Forbes K J. IS6110 transposition and evolutionary scenario of the direct repeat locus in a group of closely related Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2102–2109. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.8.2102-2109.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang Z, Doig C, Kenna D T, Smittipat N, Palittapongarnpim P, Watt B, Forbes K J. IS6110-mediated deletions of wild-type chromosomes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1014–1020. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.3.1014-1020.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fomukong, N., M. Beggs, H. El Hajj, G. Templeton, K. Eisenach, and M. D. Cave. 1998. Differences in the prevalence of IS6110 insertion sites in Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains: low and high copy number of IS6110.78:109–116. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Ghanekar K, McBride A, Dellagostin O, Thorne S, Mooney R, McFadden J. Stimulation of transposition of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis insertion sequence IS6110 by exposure to a microaerobic environment. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:982–993. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hermans P W, van Soolingen D, Bik E M, de Haas P E, Dale J W, van Embden J D. Insertion element IS987 from Mycobacterium bovis BCG is located in a hot-spot integration region for insertion elements in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2695–2705. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2695-2705.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johansen K A, Gill R E, Vasil M L. Biochemical and molecular analysis of phospholipase C and phospholipase D activity in mycobacteria. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3259–3266. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3259-3266.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kremer K, van Soolingen R, Frothingham R, Haas W H, Hermans P W M, Martin C, Palittapongarnpim P, Plikaytis B B, Riley L W, Yakrus M A, Musser J M, van Embden J D A. Comparison of methods based on different molecular epidemiological markers for typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains: interlaboratory study of discriminatory power and reproducibility. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2607–2618. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2607-2618.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leão S C, Rocha C L, Murillo L A, Parra C A, Patarroyo M E. A species-specific nucleotide sequence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis encodes a protein that exhibits hemolytic activity when expressed in Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4301–4306. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4301-4306.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahillon J, Chandler M. Insertion sequences. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:725–774. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.3.725-774.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller B H, Shinnick T M. Evaluation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis genes involved in resistance to killing by human macrophages. Infect Immun. 2000;68:387–390. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.387-390.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Reilly L M, Daborn C J. The epidemiology of Mycobacterium bovis infections in animals and man: a review. Tuber Lung Dis. 1995;76(Suppl. 1):1–46. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(95)90591-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ostroff R M, Wretlind B, Vasil M L. Mutations in the hemolytic-phospholipase C operon result in decreased virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01 grown under phosphate-limiting conditions. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1369–1373. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.5.1369-1373.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Otal I, Martín C, Vincent-Levy-Frebault V, Thierry D, Giquel B. Restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis using IS6110 as epidemiological marker in tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1252–1254. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.6.1252-1254.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parra C A, Londoño L P, Del Portillo P, Patarroyo M E. Isolation, characterization, and molecular cloning of a specific Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigen gene: identification of a species-specific sequence. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3411–3417. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.10.3411-3417.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sampson S L, Warren R M, Richardson M, van der Spuy G D, van Helden P D. Disruption of coding regions by IS6110 insertion in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuber Lung Dis. 1999;79:349–359. doi: 10.1054/tuld.1999.0218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith G A, Marquis H, Jones S, Johnston N C, Portnoy D A, Goldfine D H. The two distinct phospholipases C of Listeria monocytogenes have overlapping roles in escape from a vacuole and cell-to-cell spread. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4231–4237. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4231-4237.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spielmann-Ryser J, Moser M, Kast P, Weber H. Factors determining the frequency of plasmid cointegrate formation mediated by insertion sequence IS3 from Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;226:441–448. doi: 10.1007/BF00260657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thierry D, Cave M D, Eisenach K D, Crawford J T, Bates J H, Gicquel B, Guesdon J L. IS6110, an IS-like element of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:188. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.1.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thierry D, Brisson-Noel A, Vincent-Levy-Frebault V, Nguyen S, Guesdon J L, Gicquel B. Characterization of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis insertion sequence, IS6110, and its application in diagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2668–2673. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.12.2668-2673.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Embden J D A, Cave M D, Crawford J T, Dale J W, Eisenach K D, Giquel B, Hermans P, Martin C, McAdam R, Shinnick T M, Small P. Strain identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by DNA fingerprinting: recommendations for a standardized methodology. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:406–409. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.406-409.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vera-Cabrera L, Howard S T, Laszlo A, Johnson W M. Analysis of genetic polymorphism in the phospholipase region of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1190–1195. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1190-1195.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weil A, Plykatis B B, Butler W R, Woodley C L, Shinnick T M. The mtp40 gene is not present in all strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2309–2311. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2309-2311.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williamson E D, Titball R W. A genetically engineered vaccine against the alpha-toxin of Clostridium perfringens protects mice against experimental gas gangrene. Vaccine. 1993;11:1253–1258. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson K. Preparation of genomic DNA from bacteria. In: Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kinston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Wiley Interscience; 1990. pp. 2.4.1–2.4.2. [Google Scholar]