Abstract

Lung-eye-trachea disease-associated herpesvirus (LETV) is linked with morbidity and mortality in mariculture-reared green turtles, but its prevalence among and impact on wild marine turtle populations is unknown. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was developed for detection of anti-LETV antibodies and could distinguish LETV-exposed green turtles from those with antibodies to fibropapillomatosis-associated herpesvirus (FPHV). Plasma from two captive-reared green turtles immunized with inactivated LETV served as positive controls. Plasma from 42 healthy captive-reared green turtles and plasma from 30 captive-reared green turtles with experimentally induced fibropapillomatosis (FP) and anti-FPHV antibodies had low ELISA values on LETV antigen. A survey of 19 wild green turtles with and 27 without FP (with and without anti-FPHV antibodies, respectively) identified individuals with antibodies to LETV regardless of their FP status. The seroprevalence of LETV infection was 13%. The presence of antibodies to LETV in plasma samples was confirmed by Western blot and immunohistochemical analyses. These results are the first to suggest that wild Florida green turtles are exposed to LETV or to an antigenically closely related herpesvirus(es) other than FPHV and that FPHV and LETV infections are most likely independent events. This is the first ELISA developed to detect antibodies for a specific herpesvirus infection of marine turtles. The specificity of this ELISA for LETV (ability to distinguish LETV from FPHV) makes it valuable for detecting exposure to this specific herpesvirus and enhances our ability to conduct seroepidemiological studies of these disease-associated agents in marine turtles.

All species of marine turtles have suffered serious population declines from overharvesting for their eggs, meat, and shells; entrapment by fishing lines and nets; collisions with boats; dredging operations; and destruction of nesting beaches and foraging habitat, and are currently either threatened or endangered (22). Little is known about the impact that infectious diseases have had on marine turtle populations, although it is well established that infections with pathogens are capable of causing significant mortality in marine life (17, 18, 23).

Herpesviruses have been implicated as the etiological agents of three marine turtle diseases. The fibropapillomatosis-associated herpesvirus (FPHV) has been identified in green turtles (Chelonia mydas) with experimentally induced fibropapillomatosis (FP) and has been associated with naturally occurring FP in green, loggerhead (Caretta caretta), and olive Ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea) turtles (10, 16, 19, 25). The prevalence of FP is greater than 90% in some wild green turtle populations, and this disease has become an increasing threat to wild marine turtle populations worldwide (9, 19). Although FP has reached epizootic proportions in some wild marine turtle populations, the relationship between exposure to FPHV and development of FP in wild populations has not been studied. FPHV has not been isolated in culture to allow fulfillment of Koch's postulates for this virus and detailed study of viral pathogenesis.

The two other documented herpesvirus infections have been associated with green turtles raised in mariculture. A herpesvirus infection is associated with gray patch disease (GPD), a necrotizing dermatitis of posthatching green turtles raised in mariculture. To our knowledge, the original putative cultures of this virus were not maintained (26). Lung-eye-trachea disease (LETD)-associated herpesvirus (LETV) was isolated from green turtles exhibiting conjunctivitis, pharyngitis, tracheitis, and pneumonia at the Cayman Turtle Farm, Grand Cayman, British West Indies (15). Two successive outbreaks at the Cayman Turtle Farm among 12- to 24-month-old green turtles resulted in 8 to 38% mortality (15). Infection with this virus has not yet been documented in wild green turtles. However, the characteristic signs of stomatitis, glottitis, tracheitis, and bronchopneumonia have been documented in mariculture and oceanarium-reared green turtles worldwide, and mortality in posthatchling and juvenile turtles can reach 70% (8). Of significant conservation and management concern is the release of intensively reared posthatchling and young juveniles into the wild from numerous captive-rearing “head start” programs around the world. The release of these turtles has taken place for decades and continues to take place despite enzootic and epizootic disease within these facilities. Thus, there is a critical need for diagnostics such as the tests described in this paper, especially if head start-type programs are allowed to continue as a conservation strategy.

Serological studies to detect antibodies to marine turtle herpesviruses have been limited to immunohistochemical assays. For example, detection of antibodies to FPHV has relied on sections of embedded formalin-fixed tumors with viral inclusions. Variability in virus antigen load among the tumors has limited the usefulness of this technique for large-scale population serological studies. Although >95% of tumors contain herpesvirus detectable by PCR, only 10% of tumors analyzed had regions with virus inclusions suitable for staining (12, 14, 19). Immunohistochemistry has been inadequate to distinguish between anti-FPHV antibodies from anti-LETV antibodies or possible antibodies to other marine turtle herpesviruses and has pointed to the need for improved serological assays. The LETD-associated herpesvirus is the only marine turtle herpesvirus to be successfully isolated and propagated in pure culture (15) and was therefore chosen for diagnostic test development.

In this report, we describe the development of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for the specific detection of antibodies to the marine turtle herpesvirus LETV. The rationale for this effort was to examine whether LETV infections occur in wild marine turtle populations and also to develop an assay capable of distinguishing LETV from FP-associated herpesvirus infections. We provide preliminary evidence that LETV infections occur among wild turtles on the east coast of Florida and that this infection is independent of infection with FPHV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cultured cells.

A 1.5-cm skin biopsy was taken from the ventral surface of the rear flipper of a 1-year-old captive-reared green turtle, 99A-1, and digested in 10 ml of collagenase (260 U/ml) and 2.5% (wt/vol) trypsin in Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS). The digestion medium was collected, and cells were pelleted at 500 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Cells were resuspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM/F12) supplemented with 5% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin-streptomycin (2 μg/ml), gentamicin (60 μg/ml), and fungizone (1 μg/ml). The cell suspension was added to 25-cm2 vented flasks and grown in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator at 28°C. The 99A-1 primary cell strain was maintained and passaged in continuous culture. The D-1 green turtle fibroblastic cell strain was developed previously (13). Terrapene heart cell monolayer lines (TH-1; ATCC CCL 50) were also used.

Plaque purification of LETV.

An aliquot of the LETV isolated from the original clinical case of LETD was obtained courtesy of Jack Gaskin (University of Florida, Gainesville) (15). The aliquot was expanded in two passages on TH-1 cells, and plaque assays were performed to isolate individual plaques following a standard protocol (21) with the following exceptions. The virus inoculum was incubated on 60-mm dishes of TH-1 cells at 28°C for 1 h with rocking. Dishes were overlaid with agarose (SeaPlaque; FMC BioProducts, Rockland, Maine) instead of agar because agar has been reported to be toxic to reptilian cells and some animal viruses (2, 7). The agarose, incubated at 42°C instead of 55°C due to the temperature sensitivity of LETV (6), was mixed with 2× DMEM/F12 supplemented with FBS and antibiotics and added to the dishes, and then the dishes were incubated at 28°C. On day 9 postinfection, dishes were overlaid with agarose plus neutral red and scored on day 10. Plaques were picked with sterile glass Pasteur pipettes and transferred to phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) plus 1% (vol/vol) bovine serum albumin (PBS/B). The virus released in the PBS/B was replated on TH-1 cells and overlaid with agarose, and plaques were picked as described above. Each twice-plaque-purified clone was expanded on a 100-mm dish of TH-1 cells. Two of the LETV clones, 221 and 292, were used in this study.

Antigen preparation.

Plaque-purified LETV clones 292 and 221 were propagated in TH-1, D-1, or 99A-1 cells grown in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 5% FBS and antibiotics in vented flasks in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator at 28°C. Monolayers with 75 to 80% cytopathic effect (CPE) were scraped into medium and stored frozen. The cell suspension was thawed, sonicated for 60 s, and clarified by centrifugation at 2,500 × g for 20 min at 4°C. Virus was pelleted from the supernatant by ultracentrifugation at 40,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C. Virus pellets were resuspended in PBS and repelleted under the same conditions. The washed virus pellet was resuspended in 2 to 4 ml of PBS and sonicated for 60 s. Virus titers were determined by plaque assay as described. Uninfected cells were scraped into medium, pelleted, resuspended in PBS, and sonicated to serve as uninfected cell lysate controls. Protein concentrations of virus and uninfected cell controls antigens were measured by the Bradford assay (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.).

Development of control LETV antisera.

Two juvenile captive-reared green turtles, 99C-1 and 99A-1, received subcutaneous immunizations with inactivated LETV preparations to produce anti-LETV antibodies to serve as reagent controls. Antigen was prepared as described above for LETV clones 292 and 221 and then inactivated by dialysis against 0.02% (vol/vol) formaldehyde at 30°C for 48 h (20). Residual formaldehyde was removed by dialysis against three changes of PBS for 24 h. Inactivation was confirmed by plaque assay as described above. Turtle 99C-1 was immunized with LETV clone 292 grown in D-1 cells, and turtle 99A-1 was immunized with LETV clone 221 grown in 99A-1 cells to minimize development of antibodies to cellular antigens. Each turtle received five immunizations every 2 weeks with 104 PFU/injection plus an equal volume of 2× Ribi's adjuvant (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.).

Green turtle plasma samples.

Plasma from 42 juvenile captive-reared green turtles (healthy turtles with no known exposure to herpesviruses) and plasma collected from 30 juvenile captive-reared green turtles after experimentally induced FP (10) were evaluated by the serological assays described below (9- to 11-month-old and 21-to 23-month-old turtles, respectively). Plasma samples collected from 27 juvenile wild FP-positive turtles and 19 juvenile wild FP-negative green turtles netted in the Indian River Lagoon (Indian River County, Florida; 27°49′N, 80°26′W) and along the Wabassco Beach (Indian River County, 27°47′N, 80°24′W) were also included (12). All of these plasma samples had been evaluated previously by immunohistochemistry for antibodies to FPHV (12). Plasma from all FP-positive green turtles contained anti-FPHV antibodies, and all FP-negative green turtles did not (12). Plasma from turtle 99C-1 pre- and 2 months postimmunization with LETV served as the negative and positive LETV antibody controls, respectively.

ELISA procedure.

Each well of a 96-well flat-bottomed microtiter plate (Nunc-Immuno MaxiSorp; Nunc, Kamstrup, Denmark) was filled with 50 μl of 292 LETV or uninfected cell lysate control, diluted in sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) containing 0.15 M NaCl and 0.02% NaN3 (PBS/A) to a concentration of 5 μg/ml, and then covered with sealing tape and incubated overnight at 4°C. The wells were washed four times with 250 μl of PBS/A containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS/T) using an automatic microplate washer (EAWII; SLT-Labinstruments, Salzburg, Austria), and then blocked overnight with 300 μl per well of PBS/T containing 5% (wt/vol) nonfat dry milk (PBS/TM) at 4°C. After four more washes, 50 μl of green turtle plasma samples diluted 1:25 in PBS/TM or negative or positive LETV antibody control plasma diluted 1:100 in PBS plus 2% FBS (PBS/F) were added to the appropriate wells. For titration experiments, plasma samples were twofold serially diluted. Each plasma sample was incubated with 292 LETV and uninfected cell lysate control for 1 h at room temperature on a Nutator (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, Md.). The microplate was washed as described above, and 50 μl of biotinylated monoclonal HL858 (anti-green turtle 7S immunoglobulin G [IgG]) (11) diluted in PBS/A to a concentration of 1 μg/ml was incubated for 1 h at room temperature on a Nutator. After washing, 50 μl of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin (Zymed Laboratories Inc., San Francisco, Calif.) diluted 1:5,000 in PBS/A was added to each well. The microplate was incubated and washed as described above, and then 100 μl of p-nitrophenyl phosphate disodium (1 mg/ml in 0.01 M sodium bicarbonate [pH 9.6], 2 mM MgCl2) was added to each well. The microplate was incubated in the dark without agitation at room temperature. The A405 of each well was measured in an ELISA plate reader (Spectra II; SLT-Labinstruments, Salzburg, Austria) with DeltaSoft version 3.3 software (Biometallics, Princeton, N.J.).

Optical density values were adjusted as follows. For each plasma sample, the optical density of the well coated with uninfected cell lysate was subtracted from the optical density of the well coated with virus to account for nonspecific absorbance. Optical densities equal to or less than 0 were adjusted to 0.001 for statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SigmaStat 2.03 software (SPSS Incorporated, Chicago, Ill.). The Kolmgorov-Smirnov normality test was applied to optical density value data measured by ELISA from plasma of captive-reared FP-negative, captive-reared FP-positive, wild FP-positive, and wild FP-negative turtles. Because many of the groups were non-normally distributed, the following statistical analyses were used. The Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used to compare captive-reared FP-positive to captive-reared FP-negative turtles and to compare wild FP-positive turtles to wild FP-negative turtles. The Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) on ranks was used to compare all of the groups. To identify the group or groups that differed from the others, all pairwise multiple comparison procedures were performed using Dunn's method. For estimating seroprevalences, a cutoff value was based on the optical density values obtained from the 42 healthy captive-reared green turtles. The cutoff value was calculated as the highest optical density value obtained from these healthy turtles plus three times the standard deviation (cutoff value = 0.310). Chi-square analysis was used to compare the relative frequencies of seroprevalence.

Immunoblotting.

The specificities of the polyclonal anti-LETV antibodies from the LETV-immunized green turtles and plasma from FP-positive and FP-negative turtles seropositive for anti-LETV antibodies were tested by Western immunoblotting. Clone 292 LETV and uninfected cell lysate control antigens were separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) under denaturing conditions with a precast 10% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide bis-Tris gel and MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) running buffer (NuPAGE,-Novex, San Diego, Calif.). The separated proteins were electroblotted from the gel onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and then the membrane was blocked overnight with PBS/TM at 4°C. The blocked blot was washed in PBS/T and then incubated with green turtle plasma at a 1:25 dilution in PBS/TM or LETV control plasma diluted 1:100 in PBS/F for 60 min at room temperature with rocking in a manifold (Pierce). After washing, the blot was removed from the manifold and incubated with HL858 as described for 60 min at room temperature on a rocker. After washing the membrane, it was incubated in alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin as described for 60 min at room temperature on a rocker. After a final washing, the blot was developed in substrate buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCl [pH 8.8], 1 mM MgCl2) containing nitroblue tetrazolium chloride and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate p-toluidine salt (Promega, Madison, Wis.).

Immunohistochemistry.

TH-1 cells were cultured as described above in two-well glass chamber slides (Nalgene; Nunc, Naperville, Ill.) and grown to confluency. One well was infected with LETV 292, and after 40 to 50% CPE was observed, cells in the infected and the uninfected wells were fixed with 2% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer (0.12 M NaH2PO4 · H2O, 0.28 M Na2HPO4 [pH 7.2]), permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100, washed with PBS, and then air dried. On the day of the assay, slides were rehydrated in PBS, and endogenous peroxidases were inactivated by adding 3% hydrogen peroxide for 30 min. Slides were blocked with PBS plus 2% (vol/vol) horse serum (PBS/H) for 20 min at room temperature in a moist chamber. Then, 100 μl of green turtle plasma diluted 1:25 in PBS/TM or LETV control plasma diluted 1:100 in PBS/F was added to each well. The slides were incubated overnight at 4°C in a moist chamber. Each slide was washed individually in three changes of PBS for 10 min each.

For the following incubations, 100 μl of each reagent was added to each well and the slide was incubated for 45 min at room temperature in a moist chamber. Unbiotinylated monoclonal antibodies HL858 (1 μg/ml) and HL673 anti-tortoise Ig light chain (27) at 1 μg/ml in PBS/H were added to each well. Slides were washed as before, and then 2% (vol/vol) universal anti-IgG-conjugated biotin in PBS (Vectastain ABC kit; Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, Calif.) was added. The slides were washed and then incubated with horseradish peroxidases-conjugated streptavidin. After washing, slides were incubated in Coplin jars containing chilled chromogen (0.3 mg of 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrachloride per ml in PBS) and monitored microscopically for color development relative to the positive and negative LETV antibody controls. Using standard procedure, slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted with coverslips (4). Stained slides were viewed with an Olympus BX50F microscope and photographed with an Olympus digital camera.

RESULTS

Detection of seroconversion by ELISA.

Positive control antisera to LETV were generated by immunizing two captive-reared juvenile green turtles, 99A-1 and 99C-1, with inactivated LETV clones 221 and 292, respectively. The ELISA was able to detect antibodies to LETV in the plasma of both turtles as early as 1 to 2 months postimmunization (data not shown). Anti-LETV was still detectable at least 4.5 months after the last immunization. Plasma samples from 99C-1 before and 2 months after LETV immunization served as the negative and positive controls, respectively, for all future experiments.

To assess the interassay reproducibility of the ELISA, the mean A405, standard deviation (SD), and coefficient of variation (CV) for the negative and positive reagent controls of 10 ELISAs were calculated. The positive control (mean A405 = 1.874, SD = 0.186) with a coefficient of variance value equal to 9.9 demonstrated the reproducibility of the assay. A CV value of ≤10% is considered excellent (5). The negative control (mean A405 = 0.007; SD = 0.015) had a CV value (SD/mean A405 × 100) equal to 210, since both the mean A405 and standard deviation were such small values.

Survey of captive-reared green turtles for antibodies to LETV.

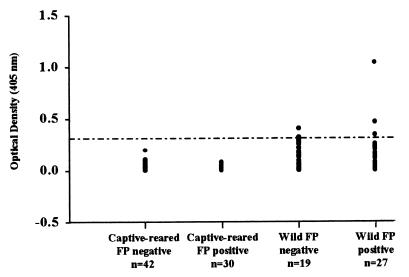

Plasma samples from captive-reared green turtles without experimentally induced FP were tested in the ELISA format (Fig. 1). Optical density values for these plasma samples were very low (mean A405 = 0.020; standard error [SE] = 0.006). To evaluate potential cross-reactivity between anti-FPHV antibodies and LETV antigens, plasma samples from 30 turtles with experimentally induced FP and anti-FPHV antibodies previously detected by immunohistochemistry (12) were tested by ELISA (Fig. 1). The optical density values for these plasma samples were also very low (mean A405 = 0.020; SE = 0.004). Both groups were non-normally distributed (P < 0.001). There was no difference in ELISA values between plasma from the turtles with and without experimentally induced FP (Mann-Whitney test; T = 1238.0; P = 0.153). Based on the cutoff value of 0.310, the green turtles with experimentally induced FP were seronegative for antibodies to LETV (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Antibodies to LETV in plasma from captive-reared and wild green turtles by ELISA. Plasma from 42 captive-reared turtles with no known exposure to herpesviruses and from 30 captive-reared turtles with experimentally induced FP had low optical density values (seronegative). Plasma from 27 wild FP-positive and 19 wild FP-negative turtles had higher ELISA values, regardless of FP status. The cutoff of 0.310 (dashed line) was used to calculate seroprevalence. Plasma samples were tested at a 1:25 dilution. Positive control: mean A405 = 1.874, SE = 0.059; negative control: mean A405 = 0.007, SE = 0.005, 10 replicates.

Survey of wild green turtles for antibodies to LETV.

The ELISA was then applied to plasma previously tested for FPHV antibodies (12) from free-ranging FP-positive (n = 27) and FP-negative (n = 19) green turtles to assay for the presence of anti-LETV antibodies. In contrast to the captive-reared turtles, ELISA values were higher from plasma collected from both FP-positive (mean A405 = 0.192, SE = 0.041) and FP-negative (mean A405 = 0.143; SE = 0.027) wild green turtles (Fig. 1). The wild FP-negative plasma was normally distributed (P > 0.200), but the wild FP-positive plasma was not normally distributed (P < 0.001). There was no difference between ELISA values of plasma from FP-positive and FP-negative turtles (Mann-Whitney rank; I = 425.5; P = 0.647) demonstrating the lack of a correlation between FP status of wild green turtles and ELISA values measured to LETV. Both of the wild groups were different from the captive-reared turtles (Dunn's method; P < 0.05). Based on the cutoff (Fig. 1), 10.5% of the FP-negative and 14.8% of the FP-positive green turtles were seropositive for antibodies to LETV. There was no statistically significant correlation between LETV seroprevalence and FP status (chi-square = 0.195, P > 0.50). The seroprevalence overall for Florida green turtles tested was 13%. These results were confirmed by Western blot and immunohistochemistry.

Confirmation of anti-LETV antibodies in green turtle plasma.

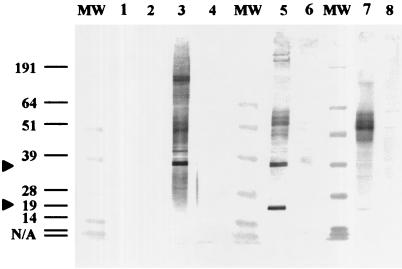

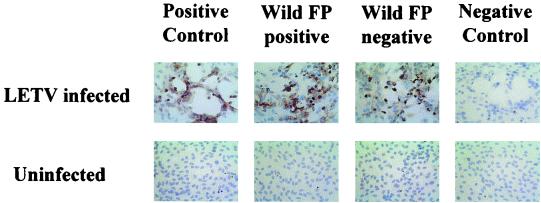

Plasma samples from FP-positive and FP-negative wild green turtles that were LETV seropositive by ELISA were titered and tested by two complementary serological assays, Western blot and immunohistochemistry. The anti-LETV antibodies displayed a normal titration pattern reflecting their specific interaction with LETV antigen in the ELISA (data not shown). Plasma samples that were LETV seropositive by ELISA also reacted with LETV-infected cell preparations in a Western blot format (Fig. 2). Antibodies in plasma from LETV-immunized, FP-positive, and FP-negative turtles seropositive by ELISA recognized similar bands in the LETV-infected cells. Although antibodies in plasma bound to a number of bands, the immunodominant bands were approximately 38 and 19 kDa (Fig. 2, arrows). Faint background or nonspecific binding to various proteins in the uninfected cell lysate control, containing medium and serum proteins, was also noted. When assayed by immunohistochemistry, the plasma containing LETV antibodies, as measured by ELISA, reacted specifically with LETV-infected cells in the zones of CPE and not with uninfected cells (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Western blot confirms presence of antibodies to LETV in green turtle plasma samples with the highest optical density values in the ELISA. LETV (10 μg) was used as the antigen in odd-numbered lanes. Cell lysate (10 μg) was used as the control antigen in even-numbered lanes. Lanes 1 and 2, preimmune 99C-1 plasma; lanes 3 and 4, 2-month postimmune plasma; lanes 5 and 6, FP-positive plasma; lanes 7 and 8, FP-negative plasma. Lane MW, molecular size markers (in kilodaltons).

FIG. 3.

Immunohistochemistry confirms presence of antibodies to LETV in green turtle plasma samples with the highest optical density values in the ELISA. Plasma samples from FP-positive and FP-negative turtles and from the preimmune (negative control) and 2-month postimmunized (positive control) 99C-1 turtle were incubated with LETV-infected and uninfected TH-1 monolayers. Magnification, ×400.

DISCUSSION

This is the first ELISA developed for a specific herpesvirus infection of marine turtles. Immunization of two captive-reared green turtles with inactivated LETV produced an ELISA-detectable antibody response against LETV within 1 to 2 months (data not shown). The temporal pattern of this antibody response was similar to that obtained from previous immunization experiments conducted in green turtles using dinitrophenol (DNP)-conjugated bovine serum albumin (11). Assay of plasma collected from captive-reared and wild green turtles illustrated the absence of a correlation between the presence of anti-FPHV antibodies and reactivity with LETV in the ELISA. The 30 captive-reared green turtles with experimentally induced FP (Fig. 1) were of particular interest since they were raised in captivity with no known exposure to herpesviruses and no clinical herpesvirus disease prior to their use in FP transmission studies. All 30 turtles with anti-FPHV antibodies (12) were seronegative for LETV. Thus, in contrast to the immunohistochemical format, in which the plasma from some of these FP-positive turtles with anti-FPHV antibodies reacted with LETV (presumably through cross-reactive FPHV/LETV antigens) (24), the ELISA is specific for the detection of 7S IgG anti-LETV antibodies.

There was no relationship between FP status (anti-FPHV antibodies) and reactivity with LETV in the ELISA among wild green turtles (potentially exposed to many herpesviruses) in Florida (Fig. 1) This further supports the hypothesis that these two viral infections are independent of one another. Antibodies to LETV detected by ELISA and confirmed by Western blot and immunohistochemistry in plasma of the wild green turtles (both FP positive and negative) indicated that these turtles were exposed to LETV or an antigenically related LETV-like virus. In the case of the FP-positive turtles, antibodies to LETV suggested coinfection.

When few known-positive plasma samples are available, a cutoff value based on the distribution of a known-negative population can be used to classify unknown samples as potentially positive or negative (5). In this study, a cutoff value (optical density = 0.310) based on 42 healthy captive-reared green turtles was used to calculate an estimated seroprevalence of LETV at a Florida study site. Based on this cutoff, 13% of the green turtles assayed in this sample possessed antibodies to LETV. Recently, a larger survey of plasma samples from 329 wild green turtles from three study sites in Florida revealed a seroprevalence of 21.6% (3), strongly supporting the initial findings of this study. However, it is difficult to determine, using this test alone, what is the true extent of LETV exposure in the wild. Transmission studies with infectious LETV or identification of naturally infected turtles diagnosed with LET disease are needed to provide additional positive reference plasma to refine this test further and to provide information about the relationship between LETV infection, the development of class-specific (IgM, 7S IgG, and 5.7S IgG) antibody responses, and the clinical course of LET disease.

These serological data indicate that wild green turtles in Florida are exposed to LETV and identify the urgent need to investigate this disease further. Infection with LETV is likely to result in clinical disease and mortality in wild green turtle populations. The transient nature of herpesviral lesions and the pelagic and dispersed life stages of posthatchling animals make it difficult to document active disease among wild turtles. Serological assays such as the ELISA described here will enable researchers to monitor wild populations of turtles for exposure to LETV in the absence of overt disease. This assay also may serve as a health screening tool for head start programs and other release programs to reduce the risk of introducing animals harboring infection into wild turtle populations and introducing virus into marine habitats. The mechanism(s) of herpesvirus transmission in the marine environment is unknown, but LETV could potentially be transmitted to uninfected individuals by direct contact between infected turtles or by contact with substrates harboring virus, such as sediments, contaminated surfaces, or seawater. We have previously demonstrated that LETV remains infectious in seawater for up to 5 days (6).

In addition to LETV's potential impact on marine turtle health and conservation, LETV infection is a potential confounder in serological studies of the fibropapillomatosis-associated herpesvirus. Both viruses are alphaherpesviruses but differ significantly in apparent tissue tropism (unpublished data). The only method presently available for detecting FP-associated herpesvirus antibodies (12) shows significant cross-reactivity between the two viruses (24), and is therefore limited for use in seroepidemiology of free-ranging populations. The specific ELISA for LETV antibodies described here provides one of the tools needed to distinguish these different herpesvirus exposures in wild turtles, much as ELISAs are used to distinguish human herpes simplex virus (HSV), such as HSV-1 and HSV-2, exposures in humans.

Although these analyses will always be limited by the largely inaccessible life stages of these endangered wild species and complicated by the known significant effects of age, temperature, season, and hormones on antibody responses in these reptiles (1), the development of the LETV-specific ELISA allows further exploration of the impact of this herpesvirus on marine turtle health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by research grants RWO 180 and RWO 194 from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Department of the Interior, administered by the Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Unit, University of Florida, Gainesville.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambrosius H. Immunoglobulins and antibody production in reptiles. Oxford, England: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1976. pp. 298–334. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark H F, Karzon D T. Iguana virus, a herpes-like virus isolated from cultured cells of a lizard, Iguana iguana. Infect Immun. 1972;5:559–569. doi: 10.1128/iai.5.4.559-569.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coberley S S, Herbst L H, Ehrhart L M, Bagley D A, Hirama S, Jacobson E R, Klein P A. Survey of Florida green turtles for exposure to a disease-associated herpesvirus. 2001. Dis. Aquat. Org., in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coligan J E, Kruisbeek A M, Margulies D H, Shevach E M, Strober W. Current protocols in immunology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crowther J R. Methods in molecular biology: the ELISA guidebook. Totowa, N.J: Humana Press; 2001. pp. 301–326. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curry S S, Brown D R, Gaskin J M, Jacobson E R, Ehrhart L M, Blahak S, Herbst L H, Klein P A. Persistent infectivity of a disease-associated herpesvirus in green turtles after exposure to seawater. J Wildl Dis. 2000;36:792–797. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-36.4.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Maeyer E, Schonne E. Starch gel as an overlay for the plaque assays of animal viruses. Virology. 1964;24:13–18. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(64)90142-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glazebrook J S, Campbell R S, Thomas A T. Studies on an ulcerative stomatitis-obstructive rhinitis-pneumonia disease complex in hatchling and juvenile sea turtles Chelonia mydas and Caretta caretta. Dis Aquat Org. 1993;16:133–147. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herbst L H. Fibropapillomatosis of marine turtles. Annu Rev Fish Dis. 1994;4:389–425. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herbst L H, Jacobson E R, Moretti R, Brown T, Sundberg J P, Klein P A. Experimental transmission of green turtle fibropapillomatosis using cell-free tumor extracts. Dis Aquat Org. 1995;22:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herbst L H, Klein P A. Monoclonal antibodies for the measurement of class-specific antibody responses in the green turtle, Chelonia mydas. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1995;46:317–335. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(94)05360-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herbst L H, Greiner E C, Ehrhart L M, Bagley D A, Klein P A. Serological association between spirorchidiasis, herpesvirus infection, and fibropapillomatosis in green turtles from Florida. J Wildl Dis. 1998;34:496–507. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-34.3.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herbst L H, Sundberg J P, Shultz L D, Gray B A, Klein P A. Tumorigenicity of green turtle fibropapilloma-derived fibroblast lines in immunodeficient mice. Lab Anim Sci. 1998;48:162–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herbst L H, Jacobson E R, Klein P A, Balazs G H, Moretti R, Brown T, Sundberg J P. Comparative pathology and pathogenesis of spontaneous and experimentally induced fibropapillomas of green turtles (Chelonia mydas) Vet Pathol. 1999;36:551–564. doi: 10.1354/vp.36-6-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobson E R, Gaskin J M, Roelke M, Greiner E C, Allen J. Conjunctivitis, tracheitis, and pneumonia associated with herpesvirus infection in green sea turtles. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1986;189:1020–1023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobson E R, Harris R K, Buergelt C, Williams B. Herpesvirus in cutaneous fibropapillomas of the green turtle, Chelonia mydas. Dis Aquat Org. 1991;12:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kennedy S. Morbillivirus infections in aquatic mammals. J Comp Pathol. 1998;119:201–225. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9975(98)80045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennedy S, Kuiken T, Jepson P D, Deaville R, Forsyth M, Barrett T, van de Bildt M W, Osterhaus A D, Eybatov T, Duck C, Kydyrmanov A, Mitrofanov I, Wilson S. Mass die-off of Caspian seals caused by canine distemper virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2000;6:637–639. doi: 10.3201/eid0606.000613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lackovich J K, Brown D R, Homer B L, Garber R L, Mader D R, Moretti R H, Patterson A D, Herbst L H, Oros J, Jacobson E R, Curry S S, Klein P A. Association of herpesvirus with fibropapillomatosis of the green turtle Chelonia mydas and the loggerhead turtle Caretta caretta in Florida. Dis Aquat Org. 1999;37:89–97. doi: 10.3354/dao037089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laufs R, Steinke H. Vaccination of nonhuman primates with killed oncogenic herpesviruses. Cancer Res. 1976;36:704–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahy B W J, Kangro H O. Virology methods manual. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Research Council. Decline of the sea turtles: causes and prevention. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nettles V., Jr Wildlife diseases and population medicine. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1992;200:648–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Origgi F C, Jacobson E R, Herbst L H, Klein P A, Curry S S. Proceedings of the 20th Annual Symposium on Sea Turtle Biology and Conservation. 2001. Development of serological assays for herpesvirus infections in chelonians. NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-SEFSC, in press. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quackenbush S L, Work T M, Balazs G H, Casey R N, Rovnak J, Chaves A, duToit L, Baines J D, Parrish C R, Bowser P R, Casey J W. Three closely related herpesviruses are associated with fibropapillomatosis in marine turtles. Virology. 1998;246:392–399. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rebell G, Rywlin A, Haines H. A herpesvirus-type agent associated with skin lesions of green sea turtles in aquaculture. Am J Vet Res. 1975;36:1221–1224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schumacher I M, Brown M B, Jacobson E R, Collins B R, Klein P A. Detection of antibodies to a pathogenic mycoplasma in desert tortoises (Gopherus agassizii) with upper respiratory tract disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1454–1460. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.6.1454-1460.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]