Abstract

Previously we reported the development of a highly sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay specific for anti-tuberculous glycolipid (anti-TBGL) for the rapid serodiagnosis of tuberculosis. In this study, the usefulness of an anti-TBGL antibody assay kit for rapid serodiagnosis was evaluated in a controlled multicenter study. Antibody titers in sera from 318 patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis (216 positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis in smear and/or culture tests and 102 smear and culture negative and clinically diagnosed), 58 patients with old tuberculosis, 177 patients with other respiratory diseases, 156 patients with nonrespiratory diseases, and 454 healthy subjects were examined. Sera from 256 younger healthy subjects from among the 454 healthy subjects were examined as a control. When the cutoff point of anti-TBGL antibody titer was determined as 2.0 U/ml, the sensitivity for active tuberculosis patients was 81.1% and the specificity was 95.7%. Sensitivity in patients with smear-negative and culture-negative active pulmonary tuberculosis was 73.5%. Even in patients with noncavitary minimally advanced lesions, the positivity rate (60.0%) and the antibody titer (4.6 ± 9.4 U/ml) were significantly higher than those in the healthy group. These results indicate that this assay using anti-TBGL antibody is useful for the rapid serodiagnosis of active pulmonary tuberculosis.

To eradicate tuberculosis, it is important to improve diagnostic techniques so that active tuberculosis can be treated at an early stage before tuberculous bacilli can be detected in the sputa. The tuberculin skin test is not useful in subjects with a previous history of active tuberculosis or Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccination. Gene technology utilizing nucleic acid amplification has been successfully introduced for rapid diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis. Clinically, however, its usefulness is reduced in patients without sputum expectoration. In fact, in previous papers, including a report of the American Thoracic Society (ATS) Workshop in 1997, the sensitivity of gene diagnosis was reported to be about 50% in patients with acid-fast bacillus smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis (4, 6, 8) and was particularly low (5 to 20%) in smear and culture-negative patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis (5, 12). A further drawback is that this test is expensive. Therefore, there has been strong demand for the development of rapid, reliable, and less costly diagnostic methods for the detection of pulmonary tuberculosis.

We previously developed an enzyme immunoassay in which the glycolipid antigen trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate (TDM) purified from Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv was used as an antigen for detecting antituberculosis immunoglobulins and showed that a glycolipid was an effective antigen for serodiagnosis (13, 16). Subsequently, by mixing TDM with more hydrophilic glycolipids, we constructed a new tuberculous glycolipid (TBGL) antigen and successfully established a sensitive serodiagnostic kit for tuberculosis using this antigen (15). For this report, by a controlled multicenter study we evaluated the practical diagnostic value of this anti-TBGL antibody assay for active pulmonary tuberculosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and serum specimens.

A total of 1,277 subjects from four institutions were entered into this study. This group consisted of 823 patients with active tuberculosis, nontuberculous mycobacteriosis (NTM), old pulmonary tuberculosis, other respiratory diseases, and nonrespiratory diseases and 454 healthy subjects. Serum specimens were obtained from the following six groups.

(i) Active pulmonary tuberculosis group.

The active pulmonary tuberculosis group consisted of 164 patients with smear-positive and culture-positive tuberculosis who had active lesions on chest radiograms, 52 patients with culture-positive tuberculosis and active chest radiogram lesions for whom three consecutive tests on admission were smear negative, and 102 patients with smear-negative and culture-negative tuberculosis who had been clinically diagnosed and treated by antituberculous chemotherapy. The last of these groups was class 3 according to the ATS tuberculosis classification (1, 3).

Serum specimens were obtained upon admission before chemotherapy and stored at −20°C until assay of anti-TBGL antibody titers. Sputum specimens for examinations by smear staining and cultivation were obtained on three consecutive days upon admission. All patients had received combination antituberculosis chemotherapy with either streptomycin or ethambutol in addition to isoniazid and rifampin for 6 months following admission and/or pyrazinamide for 2 months following admission. Serum specimens had been obtained every month from admission until 6 months after the initial chemotherapy in 46 patients, among whom 41 patients' results were smear or culture positive.

(ii) NTM group.

Of the 111 patients who were diagnosed according to the ATS criteria of NTM, 77 had pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex disease and 34 had other pulmonary mycobacterioses (2).

(iii) Old pulmonary tuberculosis group.

The old pulmonary tuberculosis group consisted of fifty-eight patients with old tuberculosis in whom sclerotic chest X-ray-lesions had been stable and sputum examinations had been persistently negative. This group was class 4 according to the ATS tuberculosis classification.

(iv) Other respiratory disease group.

Studied were 180 patients with other respiratory diseases. This group was comprised of 61 patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 55 with neoplasm (52 with lung cancer, 2 with malignant pleural mesothelioma, and 1 with adult T-cell leukemia), 21 with pulmonary fibrosis (18 with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, 2 with pneumoconiosis, and 1 with rheumatoid lung disease), 40 with other infectious lung diseases (26 with bacterial pneumonia, 7 with diffuse panbronchiolitis, 4 with lung abscess, 2 with acute bronchitis, and 1 with pulmonary aspergillosis), and 3 with sarcoidosis. Acid-fast bacilli had not been detected in any patient in this group.

(v) Nonrespiratory disease group.

As a disease control group, 156 patients with cardiovascular or other nonrespiratory diseases were used. These patients had no pulmonary lesions on chest radiograms.

(vi) Healthy subject groups.

When we designed this study, healthy subjects were considered as one group. However, we found that in younger subjects antibody titers were significantly lower than in older subjects. We decided that the normal control group (not infected by tubercle bacilli) included a subgroup of younger healthy subjects differing in antibody status from the older patients, since in Japan the incidence of tuberculosis, although decreased, has been higher than that in the United States or European countries over the past half-century. The 454 healthy subjects who had normal findings on chest radiogram with no past history and family history of tuberculosis were assembled from primary health care offices. Of these, 384 subjects had been BCG vaccinated in childhood and 42 had received no BCG vaccination, and the BCG vaccination history was unknown in the remaining 28 subjects. No BCG-vaccinated subjects had negative tuberculin skin test results.

No patient identified as having human immunodeficiency virus infection was included in this study. All subjects provided informed consent to participate in this study according to our institutional guidelines.

TBGL assay kit and method of assay.

The serum specimens were assayed without knowledge of the clinical status in every case. TBGL assay kits manufactured using TBGLs consisting of TDM and minor glycolipids (trehalose monomycolate, diacyltrehalose, phenolic glycolipid, 2,3,6,6-tetraacyl-trehalose-2-sulfate, and 2,3,6-triacyl-trehalose) prepared from the cell walls of M. tuberculosis H37Rv were provided by Kyowa Medex Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). Details of this assay were reported previously (15). Polystyrene 96-well microtiter plates (Polysorp immunoplates; Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were sensitized by coating them with 25 μl of antigen solution (10 pg/ml in n-hexane) per well, placed at room temperature, and allowed to dry. All samples, sera, or calibrators were diluted 1/41 with dilution buffer, and 100 μl of the diluted samples was added to each well, after which the plates were incubated for 60 min at room temperature. After the plates were washed five times with buffer, anti-human immunoglobulin G (IgG) rabbit Fab′-horseradish peroxidase was added to each well and the plates were incubated for 60 min at room temperature. Plates were washed three times with washing buffer, 100 μl of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMBZ) solution was added to each well, and the plates were thereafter incubated for 15 min at room temperature. To stop the enzymatic reaction, 100 μl of 1 M H2SO4 was added and absorbance at 450 nm was measured with an MTP-120 plate reader (Corona Electric Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analyses.

Statistical analyses were performed by conventional methods. Numerical anti-TBGL antibody values were converted into logarithmic values. Multiple comparison tests (analysis of variance, Scheffe F tests) were performed for a single factor model because some of the values in each group did not show normal distribution. Values are means ± 1 standard deviation (SD). Changes of antibody titers by tuberculosis chemotherapy were analyzed using paired t tests.

RESULTS

Selection of healthy control subjects.

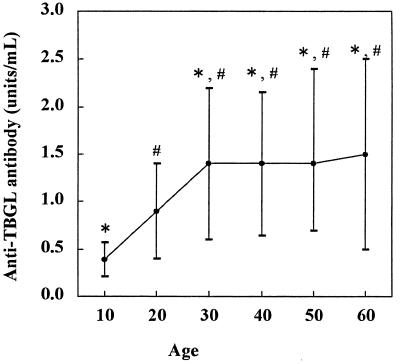

In selecting healthy control subjects, it is necessary to select persons who have not been infected by acid-fast bacilli because in Japan the incidence of tuberculosis, while it has decreased, has been higher than that in the United States or European countries over the past half-century. There was no significant difference in the antibody titers in serum between BCG-vaccinated subjects (1.2 ± 1.0 U/ml) and those not vaccinated (1.3 ± 1.3 U/ml). Healthy subjects were divided into six groups according to age (Fig. 1). In the first two groups, the antibody titers were significantly (P < 0.01) lower than those in the four older groups, indicating that healthy subjects less than 30 years old should be selected as healthy controls.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of anti-TBGL antibody titers in healthy subjects according to age. Each point represents the mean ± SD (error bar) of the antibody titer. The following age groups (in years) comprised the indicated numbers of subjects: 10s, n = 58; 20s, n = 198; 30s, n = 16; 40s, n = 91; 50s, n = 62; 60s, n = 29. Symbols indicate significant difference from the value for the first decade and the second decade: ∗, P < 0.01; #, P < 0.01.

Cutoff point of anti-TBGL antibody titer and mean value.

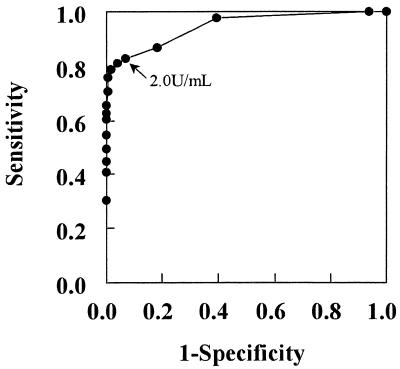

The normal range for the antibody titer was determined to be lower than 2 SDs above the mean of converted logarithmic values (−0.175 ± 0.239) in younger healthy subjects. The cutoff point for antibody titer in serum was determined to be 2.0 U/ml. In addition, receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve analysis was performed between younger healthy subjects and patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis (Fig. 2). The cutoff point was also determined to be 2.0 U/ml using the ROC curve.

FIG. 2.

ROC curve analysis for diagnosis of active pulmonary tuberculosis. ROC curve analysis was performed for comparison between younger healthy subjects and patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis.

The mean value of the anti-TBGL antibody titer in each group is summarized in Table 1. In the younger healthy subjects, it was 0.8 ± 0.5 U/ml. The antibody titers in the active pulmonary tuberculosis (total and in the three subgroups) and NTM groups were significantly higher than in the other five groups. Even in patients with smear-negative and culture-negative tuberculosis, the antibody titers were significantly higher than in the old pulmonary tuberculosis group, the other respiratory disease group, the nonrespiratory disease group, and the two healthy subject groups. There was no significant difference in the antibody titers in the older healthy subjects compared with those in the old tuberculosis group, the other respiratory disease group, and the nonrespiratory disease group.

TABLE 1.

Anti-TBGL antibody titers in each group

| Row | Group | n | Mean age ± SD (yr) | Mean titer ± SD

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (U/ml) | Statistical significancea for comparison with value in row:

|

||||||||

| G | F | E | D | C | |||||

| A | Active pulmonary tuberculosis | 318 | 53.1 ± 18.5 | 12.5 ± 17.9 | # | # | # | # | # |

| Smear positive, culture positive | 164 | 53.8 ± 17.5 | 17.9 ± 21.0 | # | # | # | # | # | |

| Smear negative, culture positive | 52 | 54.2 ± 20.0 | 6.2 ± 8.8 | # | # | # | # | # | |

| Smear negative, culture negative | 102 | 51.7 ± 19.5 | 7.5 ± 13.4 | # | # | # | # | # | |

| B | Nontuberculous mycobacteriosis | 111 | 64.9 ± 13.1 | 10.2 ± 14.8 | # | # | # | # | # |

| C | Old tuberculosis | 58 | 57.0 ± 16.7 | 1.6 ± 0.8 | # | NS | NS | NS | |

| D | Other respiratory disease | 180 | 64.2 ± 13.0 | 1.3 ± 1.3 | NS | NS | NS | ||

| E | Nonrespiratory disease | 156 | 68.3 ± 11.2 | 1.2 ± 0.9 | NS | NS | |||

| F | Older healthy subjects | 198 | 49.5 ± 8.3 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | # | ||||

| G | Younger healthy subjects | 256 | 22.3 ± 3.3 | 0.8 ± 0.5 | |||||

#, P < 0.05; NS, not significant.

Sensitivity and specificity using anti-TBGL antibody.

When the cutoff point was settled at 2.0 U/ml, the specificities in the older and younger healthy subjects were 82.8 and 95.7%, respectively (Table 2). For the total of 318 patients who comprised the active pulmonary tuberculosis group, sensitivity was 81.1%. Even in the subgroup of 102 patients with smear- and culture-negative active pulmonary tuberculosis, sensitivity was 73.5%. Anti-TBGL antibody was positive in 79.3% of the 111 patients with NTM. Specificities did not differ significantly among the old tuberculosis group (74.1%), other respiratory disease group (85.0%), nonrespiratory disease group (84.6%,) and the older healthy subjects (82.8%) but were lower than those in the younger healthy group (95.7%) (Table 2). In the smear-negative active pulmonary tuberculosis group, the mean antibody titer and the positivity rate were significantly higher than those values in each subgroup of the other respiratory diseases group (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Positivity rate of anti-TBGL antibody in each group

| Group | No. of subjects

|

Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Positivea | Negative | |||

| Active pulmonary tuberculosis | 318 | 258 | 60 | 81.1 | |

| Smear positive, culture positive | 164 | 147 | 17 | 89.6 | |

| Smear negative, culture positive | 52 | 36 | 16 | 69.6 | |

| Smear negative, culture negative | 102 | 75 | 27 | 73.5 | |

| Nontuberculous mycobacteriosis | 111 | 88 | 23 | 79.3 | |

| Old tuberculosis | 58 | 15 | 43 | 74.1 | |

| Other respiratory disease | 180 | 27 | 158 | 85.0 | |

| Nonrespiratory disease | 156 | 24 | 132 | 84.6 | |

| Older healthy subjects | 198 | 34 | 164 | 82.8 | |

| Younger healthy subjects | 256 | 11 | 245 | 95.7 | |

Cutoff value was set at 2.0 U/ml.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of anti-TBGL antibody levels in patients with smear-negative active pulmonary tuberculosis and other respiratory diseases

| Group | All patients (n) | Anti-TBGL antibody

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positivea

|

Titer (mean ± SD) | |||

| n | Rate (%) | |||

| Smear-negative active pulmonary tuberculosis | 154 | 111 | 72.1 | 6.9 ± 11.9 |

| Other respiratory diseases | ||||

| COPDc | 61 | 9 | 14.8 | 0.8 ± 0.1b |

| Neoplasma | 55 | 7 | 12.7 | 1.1 ± 0.2b |

| Pulmonary fibrosis | 21 | 5 | 23.8 | 2.1 ± 0.5b |

| Other infectious disease | 40 | 5 | 12.5 | 1.6 ± 0.2b |

| Sarcoidosis | 3 | 1 | 33.0 | 1.3 ± 1.3b |

Cutoff value was set at 2.0 U/ml.

Significantly different from the value for smear-negative active pulmonary tuberculosis (P < 0.01).

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Anti-TBGL antibody titers according to chest X-ray lesions in patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis.

According to chest X-ray findings, the positivity rate and the antibody titer were higher in patients with cavitary lesions (89.4% [160 of 179 patients]; titer, 16.4 ± 19.8 U/ml) compared with patients with noncavitary lesions (66.3% [69 of 104 patients]; titer, 7.5 ± 13.6 U/ml) (Table 4). Among the five subgroups according to chest X-ray findings, the mean antibody titer and positivity rates in subgroups with far and moderately advanced cavitary lesions were significantly higher than in patients with moderately and minimally advanced noncavitary lesions. Even in the subgroup with minimally advanced noncavitary lesions, which included 25 (55.6%) patients with smear- and culture-negative active pulmonary tuberculosis, the positivity rate (60.0%) and the antibody titer (4.6 ± 9.4 U/ml) were significantly higher than those in the older and younger healthy groups.

TABLE 4.

Positive rate of anti-TBGL antibody according to chest X-ray findings in patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis

| Sputum examination result | Positive rate according to chest X-ray findingsa

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cavitary lesions

|

Noncavitary lesions

|

||||

| Far advanced | Moderately advanced | Far advanced | Moderately advanced | Minimally advanced | |

| Smear positive, culture positive | 29/32 (93.5) | 83/89 (93.3) | 5/5 (100.0) | 19/25 (76.0) | 5/7 (71.4) |

| Smear negative, culture positive | 3/3 (100.0) | 16/22 (72.3) | 1/2 (50.0) | 4/7 (57.1) | 8/13 (61.5) |

| Smear negative, culture negative | 6/6 (100.0) | 23/28 (82.1) | 1/3 (33.3) | 12/17 (70.6) | 14/25 (56.0) |

| Total | 38/40 (95.0) | 122/139 (87.8) | 7/10 (70.0) | 35/49 (71.4) | 27/45 (60.0) |

The cutoff value was set at 2.0 U/ml. Results are presented as numbers of positive subjects/total number of subjects (percentages). The mean anti-TBGL titers ± SDs (units per milliliter) for patients with far advanced and moderately advanced cavitary lesions were 16.9 ± 16.9 and 15.3 ± 19.9, respectively. Those for patients with far advanced, moderately advanced, and minimally advanced noncavitary lesions were 12.2 ± 20.0, 9.3 ± 15.0, and 4.6 ± 9.4 U/ml, respectively. The values for patients with cavitary lesions were significantly different from values for patients with noncavitary lesions (P < 0.01).

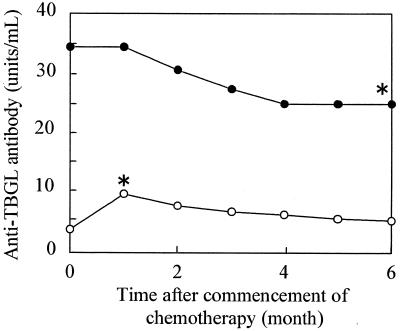

Changes of antibody titer in patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis by antituberculosis chemotherapy.

Forty-six patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis were administered antituberculosis chemotherapy in the hospital, and antibody titers were calculated each month for the initial 6 months after commencement of chemotherapy. These patients were divided into two groups according to the level of antibody titer (high group, >10 U/ml; low group, ≤10 U/ml) (Fig. 3). The mean antibody titer in the high group decreased after antituberculosis chemotherapy but significantly increased in the initial 1 month in the low group. Antibody titers significantly decreased from the maximum mean value of 22.8 ± 22.8 U/ml for each patient to 12.8 ± 15.5 U/ml after 6 months of antituberculosis chemotherapy.

FIG. 3.

Changes of anti-TBGL antibody titer in two groups with active pulmonary tuberculosis by tuberculous chemotherapy. Patients treated with chemotherapy were divided into two groups according to antibody titer (high group, >10 U/ml [●]; low group, ≤10 U/ml [○]). ∗, significantly different from prechemotherapy value (month 0), P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

In the last decade, much progress has been reported in studies of antibodies to M. tuberculosis in the serum of patients with tuberculosis using various antigens (10, 11, 16, 18). However, no serodiagnostic method has been established. We previously reported the usefulness of detecting antibody to TBGL in serum, which is significantly increased in active pulmonary tuberculosis patients (19, 20). In this study, we evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of our rapid serodiagnostic method for pulmonary tuberculosis through collaboration with four institutions.

We first selected normal control subjects from healthy subjects to determine the cutoff point of the antibody titer, because the incidence of tuberculous disease has rapidly decreased in Japan in the past half-century, resulting in a low rate of tuberculous infection in young people. Additionally, combination chemotherapy with rifampin began in 1970 in Japan, and the incidence of tuberculosis has rapidly decreased from this time (172 cases per 100,000 persons) to the present (35 cases per 100,000 persons). Thus, the anti-TBGL antibody titer should be lower in young subjects born after 1970 than in those born before then. Therefore, as a control, we selected younger healthy subjects who were less than 30 years old and had no history and no family history of tuberculosis and determined the cutoff titer in serum to be 2.0 U/ml. This cutoff point may be lower in the United States or in European countries where the incidence of tuberculosis is lower than in Japan.

We compared the results obtained from methods using TBGL with previously reported results for other antigens. As indicated in Table 2, specificity for anti-TBGL antibody for control subjects in this study was 95.7%, which was close to that from data obtained for anti-CF IgG antibody (96.1%), anti-antigen 60 IgG antibody (95.0%), and antilipoarabinomannan IgG antibody (95.1%) (10, 11, 16, 18, 20). In patients with active smear-positive and/or culture-positive pulmonary tuberculosis, the sensitivity for anti-TBGL antibody was calculated to be 84.7%, about as high as those for antilipoarabinomannan IgG antibody (72.0 to ∼93.0%), anti-CF antibody (81.1%), and anti-antigen 60 IgG antibody (88.0%) in such patients. In addition, the sensitivity of the TBGL test was 73.5% in the smear- and culture-negative active pulmonary tuberculosis group. The positivity rate of anti-TBGL antibody was also high (60.0%) in patients with noncavitary minimally advanced lesions, including 25 (55.6%) patients with smear- and culture-negative active pulmonary tuberculosis. This indicates that the TBGL test is an expedient method for establishing a serodiagnosis in patients with clinically diagnosed active tuberculosis. This test is also very useful as a rapid diagnosis of active pulmonary tuberculosis in patients who have smear-negative tuberculosis and/or a nonproductive cough. Furthermore, utilization of a combination of the nucleic acid amplification might improve diagnostic accuracy. A collaborative study among nine institutions of the combination of these two tests is now in progress. Results of the role of a combination of tests using serology and gene technology, respectively, will be reported in the future.

In some patients with smear-positive tuberculosis who were not identified as being in an immunosuppressed status, the TBGL test remained negative for the period of antituberculosis chemotherapy. The lack of anti-TBGL antibody was inconsistent with an immunosuppressed status, indicating that the antigen used in the present study has not yet been completed. To improve the efficacy of the TBGL test, further studies are necessary to determine in detail the characteristics of the antigens (TDM and other molecules) and to design the most appropriate combination of various antigens such as lipoarabinomannan and antigen 60. In developing a more accurate serodiagnosis for pulmonary tuberculosis, the following three observations should be considered. (i) Many antibodies against antigens of glycolipids other than TDM are present in the sera of patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis (15). (ii) Sensitivity differs depending upon the differences in composition of the mycolic acid subclasses with regard to the antigenicity of TDM (17). (iii) The glycolipid composition of the tuberculous bacillus isolated from patients was reported to differ in each patient (7). In terms of the diagnosis of tuberculosis, however, patients who were identified as tuberculosis positive by smear test or by the nucleic acid amplification test did not need to undergo serodiagnosis. Antibody titers increased in the initial 1 to 2 months of antituberculosis chemotherapy in patients with active tuberculosis with low antibody titers (less than 2 U/ml). Therefore, it is necessary to monitor carefully the course of pulmonary tuberculosis by serologic diagnosis based on the TBGL test, especially in patients with smear-negative tuberculosis without cavitary lesions. The antibody titer significantly decreased after 6 months of antituberculosis chemotherapy but was not reduced to the normal level. We consider that a 2- to 3-year period after antituberculosis chemotherapy may be necessary before antibody titers return to normal levels (14, 16).

The patients with NTM also showed a high positivity rate because TDM exists as a common cell wall component of all acid-fast organisms such as Mycobacteria and Nocardia. It is a limitation of the assay in diagnosis that the TBGL test does not differentiate between patients with NTM and patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis. The serodiagnostic method using specific glycopeptidolipids purified from the M. avium-Mycobacterium intracellulare complex, which is being developed in our institute, may be useful for the differential diagnosis of M. avium-M. intracellulare complex pulmonary disease from tuberculosis (9).

There was no significant difference in the antibody titer in older healthy subjects compared with those in the old tuberculosis group, the other respiratory disease group, and nonrespiratory disease group. The antibody titer of 2 SDs above the mean of converted logarithmic values in the older healthy group was 4 U/ml. Now in Japan, which has a high incidence of tuberculosis, we consider that the definite cutoff point can be settled at 4 U/ml for the serodiagnosis of tuberculosis in older patients.

In the present study, we showed that the use of anti-TBGL antibody is of value in diagnosing active pulmonary tuberculosis, even among patients with smear- and culture-negative tuberculosis. Furthermore, we consider that the TBGL test may be useful for monitoring the effects of antituberculosis chemotherapy.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Thoracic Society. Diagnostic standards and classification of tuberculosis in adults and children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;161:1376–1395. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.4.16141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Thoracic Society. Diagnosis and treatment of disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteriosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:S1–S25. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.2.atsstatement. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Thoracic Society. Diagnostic standards and classification of tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:725–735. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.3.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Thoracic Society Workshop. Rapid diagnostic tests for tuberculosis. What is the appropriate use? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:1804–1914. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.5.9154896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anonymous. Present status of new examination methods for acid fast bacilli in diagnosis and treatment. Kekkaku. 1996;71(12):677–702. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradley S P, Reed S L, Catanzard A. Clinical efficacy of the amplified Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Direct test for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:1606–1610. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.5.8630609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaicumpar K, Yano I. Studies of polymorphic DNA fingerprinting and lipid pattern of Mycobacterium tuberculosis patient isolate in Japan. Microbiol Immunol. 1997;41:107–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1997.tb01176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chin D P, Yajko D M, Hadley W K, Sanders C A, Nassos P S, Madej J J, Hopewell P C. Clinical utility of a commercial test based on the polymerase chain reaction for detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis in respiratory specimens. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:1872–1877. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.6.7767534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enomoto K, Oka S, Fujiwara N, Okamoto T, Okuda Y, Maekura R, Kuroki T, Yano I. Rapid serodiagnosis of Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex infection by ELISA with cord factor (trehalose 6,6-dimycolate), and serotyping using the glycopeptidolipid antigen. Microbiol Immunol. 1998;42:689–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1998.tb02341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gevaudan M J, Bollet C, Charpin D, Mallet M N, Micco D E. Serological response of tuberculosis patients to antigen 60 of BCG. Eur J Epidemiol. 1992;5:666–676. doi: 10.1007/BF00145382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta S, Kumari S, Banwalikar J N, Gupta S K. Diagnosis utility of the estimation of mycobacterial antigen A60 specific immunoglobulins IgM, IgA and IgG in the sera of cases of adult human tuberculosis. Tuber Lung Dis. 1995;76:418–424. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(95)90008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hironobu K. Clinical evaluation of a reagent for detection of DNA of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex using the ligase chain reaction (LCR) method. 1997. J. Jpn. Infect. Dis. 1246–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hua H, Oka S, Yamamura Y, Kusunose E, Kusunose M, Yano I. Rapid serodiagnosis of human mycobacteriosis by ELISA using cord factor (treharose-6,6′-dimycolate) purified from Mycobacterium tuberculosis as antigen. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1991;76:201–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1991.tb04215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imaz M S, Zerbini E. Antibody response to culture filtrate antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis during and after treatment of tuberculous patients. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000;4:562–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawamura M, Maekura R, Yano I, Kohno H. Enzyme immunoassay to detect antituberculous glycolipid antigen (anti-TBGL antigen) antibody in serum for diagnosis of tuberculosis. J Clin Lab Anal. 1997;11:140–145. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2825(1997)11:3<140::AID-JCLA4>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maekura R, Yano I. Clinical evaluation of rapid serodiagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis by ELISA with cord factor (trehalose-6-6′-dimycolate) as antigen purified from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:997–1001. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.4_Pt_1.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan J, Fujiwara N, Oka S, Maekura R, Ogura T, Yano I. Anti-cord factor (trehalose-6,6′-dimycolate) IgG antibody in tuberculosis patients recognizes mycolic acid subclasses. Microbiol Immunol. 1999;43:863–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1999.tb01221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sada E, Brennan P J, Herrera T, Torres M. Evaluation of lipo-arabinomannan for the serological diagnosis of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2287–2590. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.12.2587-2590.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toyoda T, Osumi M, Aoyagi T, Kawasumi T. Serodiagnosis of tuberculosis by detection of anti tuberculous glycolipid antigen (TBGL antigen) antibodies in serum using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay: clinical evaluation of anti-TBGL antibodies assay kit. Kekkaku. 1996;71(12):655–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wada M, Abe C, Kohno H, Kawamura M, Yano J. Serodiagnosis with trehalose-6,6′-dimycolate of pulmonary tuberculosis. J Jpn Respir Dis. 1997;35:43–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]