Abstract

Background

In breast cancer (BC), recurrent fusion genes of estrogen receptor alpha (ESR1) and AKAP12, ARMT1 and CCDC170 have been reported. In these gene fusions the ligand binding domain of ESR1 has been replaced by the transactivation domain of the fusion partner constitutively activating the receptor. As a result, these gene fusions can drive tumor growth hormone independently as been shown in preclinical models, but the clinical value of these fusions have not been reported. Here, we studied the prognostic and predictive value of different frequently reported ESR1 fusion transcripts in primary BC.

Methods

We evaluated 732 patients with primary BC (131 ESR1-negative and 601 ESR1-positive cases), including two ER-positive BC patient cohorts: one cohort of 322 patients with advanced disease who received first-line endocrine therapy (ET) (predictive cohort), and a second cohort of 279 patients with lymph node negative disease (LNN) who received no adjuvant systemic treatment (prognostic cohort). Fusion gene transcript levels were measured by reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR. The presence of the different fusion transcripts was associated, in uni- and multivariable Cox regression analysis taking along current clinico-pathological characteristics, to progression free survival (PFS) during first-line endocrine therapy in the predictive cohort, and disease- free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) in the prognostic cohort.

Results

The ESR1-CCDC170 fusion transcript was present in 27.6% of the ESR1-positive BC subjects and in 2.3% of the ESR1-negative cases. In the predictive cohort, none of the fusion transcripts were associated with response to first-line ET. In the prognostic cohort, the median DFS and OS were respectively 37 and 93 months for patients with an ESR1-CCDC170 exon 8 gene fusion transcript and respectively 91 and 212 months for patients without this fusion transcript. In a multivariable analysis, this ESR1-CCDC170 fusion transcript was an independent prognostic factor for DFS (HR) (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.8 (1.2–2.8), P = 0.005) and OS (HR (95% CI: 1.7 (1.1–2.7), P = 0.023).

Conclusions

Our study shows that in primary BC only ESR1-CCDC170 exon 8 gene fusion transcript carries prognostic value. None of the ESR1 fusion transcripts, which are considered to have constitutive ER activity, was predictive for outcome in BC with advanced disease treated with endocrine treatment.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-022-09265-1.

Keywords: Fusion genes, ESR1, CCDC170, Breast cancer, Prognosis, RT-qPCR

Background

The estrogen receptor (ER) plays a key role in cellular growth and tumor development in a large fraction of breast cancers. As a result, endocrine therapy has been and still is a successful treatment in patients with ESR1-positive (ESR1 +) breast cancers (BC) [1]. However, in the metastatic setting, nearly half of the patients are de novo resistant to endocrine therapy while the remaining cases acquire resistance over time [2, 3]. One of the primary characterized mechanisms of acquired resistance to endocrine therapy is the acquisition of mutations within the ligand-binding domain (LBD) of the estrogen receptor alpha gene (ESR1) activating the receptor constitutively thereby rendering tumor cells less dependent on estrogen [4–7]. Another mechanism that lead to less estrogen dependency of BC cells is the occurrence of ESR1 fusion proteins. Through analysis of RNA-sequencing data in breast cancer, recurrent intragenic fusions of 5′ end of ESR1 and the 3′ ends of AKAP12, ARMT1 or CCDC170 amongst other genes have been identified [8–13]. AKAP12, ARMT1, and CCDC170 genes together with ESR1 gene were selected for our evaluation, because they all were located at the 6q25.1 locus within 1 Mb distance [14] and fusions between the two non-coding 5’ exons of ESR1 with the 3’ ends of CCDC170, AKAP12 and ARMT1, upstream of ESR1, were identified in patients resistant to endocrine treatment [9, 10].

Gene fusions were preferentially detected in high-grade disease and/or endocrine-resistant forms of ESR1 + BC [10, 13]. Particularly, an enrichment of ESR1-CCDC170 fusion was previously reported in HER-positive patients (luminal A 9%, luminal B 3–8% and HER2 3.1%) and was correlated with a worse clinical outcome after endocrine therapy [9, 15, 16]. The ESR1-AKAP12 fusion was identified in 6.5% breast cancer that were resistant to letrozole aromatase inhibitor treatment [17].The novel fusion ESR1-ARMT1 was instead detected in a HER2-negative patient with luminal A-like subtype [16] and in a breast cancer patient who had not received endocrine therapy [18]. Moreover, a recently study based on molecular characterization of luminal breast cancer in African American women reported the fusions at a frequency of 11% for ESR1-CCDC170, 8% for ESR1-AKAP12 and 6% for ESR1-ARMT1 [19]. Despite the diversity among these fusions, they share a common structure retaining the hormone-independent transactivation domain as well as the DNA-binding domain whereas their ligand-binding domain is lost and replaced with a functional (transactivating) domain of the fusion partner, suggesting a pathological impact in ESR1 + BC [13]. However, the clinical significance of these fusions has not yet been properly addressed in uniform and well annotated cohorts.

In this study, we explored the occurrence of fusion transcripts of three of the most commonly reported fusion partners of ESR1 (i.e. CCDC170, AKAP12 and ARMT1) and determined the associations of their presence with clinical outcome in a cohort of 732 breast cancer patients allowing us to investigate their predictive value for endocrine treatment failure as well as their prognostic value.

Methods

Study cohorts

The protocol to study biological markers associated with disease outcome was approved by the medical ethics committee of the Erasmus Medical Centre Rotterdam, The Netherlands (MEC 02.953) and was performed in accordance with the Code of Conduct of the Federation of Medical Scientific Societies in The Netherlands (https://www.federa.org/codes-conduct). The use of coded left-over material for scientific purposes and, therefore, for the greater good, does not require informed consent according to Dutch law and the new European general data protection regulation (GDPR).

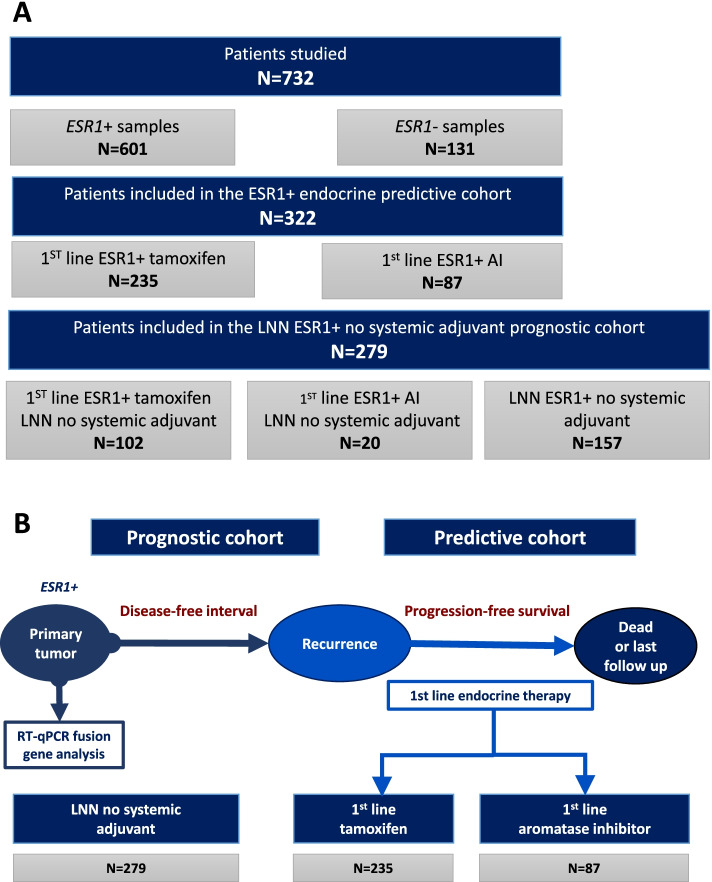

In this retrospective study (see Fig. 1A for the consort diagram of the study), female patients were included, who underwent surgery for invasive primary breast cancer between 1980 and 2000 in the Netherlands. A further selection criterion was no previously diagnosed cancers with the exception of basal cell carcinoma or stage Ia/Ib cervical cancer. Within this study, only data from sections of primary tumors with at least 30% invasive tumor cells were included. The details of tissue processing, RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis and QC of this cohort have been described previously [20, 21]. Tumor grade was assessed according to standard procedures at the time of inclusion. For the classification of patients’ RNA samples regarding expression of the estrogen and progesterone receptors, as well as the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) amplification status, reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was used with cut-offs previously described by us [20, 21].

Fig. 1.

Overview of the study and selection of available patients. A Flow diagram of the study; B Workflow of processing samples: fusion gene mRNA levels were measured in 322 ER-positive primary tumors (predictive cohort) by quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-qPCR). All patients in this cohort were hormone-naïve and all experienced a disease recurrence and subsequently received 1st line endocrine therapy. The association of the presence of ESR1 fusion genes in the primary tumor progression-free survival (PFS) after start with 1st line tamoxifen (n = 235) or aromatase inhibitors (n = 87), were evaluated. Similarly, disease free interval (DFS) and overall survival (OS) were investigated in 279 lymph node negative ER-positive breast cancer patients (prognostic cohort) who had not received any (neo)adjuvant systemic therapy. ESR1: Estrogen Receptor 1 gene; AI: Aromatase Inhibitor; LNN: Lymph node negative; ER: Estrogen Receptor; RT-qPCR: Quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR

The total cohort consisted of 732 patients with primary breast cancer (131 ESR1-negative and 601 ESR1-positive cases) (Fig. 1B). The clinical relevance of the gene fusion transcripts was evaluated in a predictive and a prognostic cohort of ESR1 + BC patients.

The predictive cohort consisted of 322 breast cancer patients with ESR1 + primary tumors of which 235 patients received tamoxifen (40 mg daily) and 87 patients an aromatase inhibitor (AI: anastrozole, letrozole, exemestane [22]) as a 1st-line treatment for recurrent disease. Clinical response to tamoxifen therapy was defined as previously described [20, 23]. The prognostic cohort included primary tumors from 279 lymph node negative (LNN) ESR1 + BC patients who had not received any systemic (neo) adjuvant therapy. Of note, 122 of these LNN ESR1 + patients were also included in the predictive cohort. Clinicopathological characteristics of each of these 2 cohorts are described in Table 1 Association of ESR1 fusions with clinical parameters of patients enrolled in the predictive cohort and in the prognostic cohort are reported in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of ER-positive breast cancer patient cohorts

| Predictive Endocrine Therapy Cohorts | Prognostic Cohort | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tamoxifen | Aromatase inhibitors | Lymph node negative (LNN) | |

| Total | 235 | 87 | 279 |

| Median age (range) | 61 (29–90) | 66 (35–86) | 55 (26–85) |

| Menopausal Status: | |||

| Premenopausal | 60 | 4 | 120 |

| Postmenopausal | 175 | 82 | 159 |

| Surgery: | |||

| Lumpectomy | 87 | 8 | 178 |

| Ablation | 147 | 22 | 101 |

| Adjuvant hormonal therapy: | |||

| no | 235 | 17 | 279 |

| yes | 0 | 69 | 0 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy: | |||

| no | 198 | 69 | 279 |

| yes | 37 | 18 | 0 |

| Lymph node status: | |||

| negative | 102 | 20 | 279 |

| positive | 81 | 49 | 0 |

| not applicable (M1) | 42 | 17 | 0 |

| Distant metastasis: | |||

| yes | 235 | 87 | 165 |

| no | 0 | 0 | 114 |

| Disease -Free Interval: | |||

| < 1 year | 59 | 13 | 20 |

| 1–3 year | 108 | 29 | 71 |

| > 3 year | 68 | 45 | 188 |

| Median Follow-up time (in months): | |||

| after surgery | 62 (3–272) | 103 (7–295) | 93 (5–337) |

| after start therapy | 30 (1–208) | 45 (2–108) | |

| PR statusa: | |||

| Positive | 186 | 72 | 217 |

| Negative | 48 | 15 | 62 |

| HER2 statusa: | |||

| Amplified | 31 | 10 | 43 |

| Not amplified | 202 | 77 | 233 |

| CCDC170 statusa: | |||

| Positive | 206 | 81 | 252 |

| Negative | 28 | 3 | 26 |

ESR1 estrogen receptor alpha, LNN lymph node negative disease, M1 methastatic stage 1, PR progesterone receptor, HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, CCDC170 coiled-coil domain containing 170, RT-qPCR Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

aas measured by RT-qPCR

Table 2.

Association of ESR1 fusions with clinical parameters in the predictive cohort

| Predictive Endocrine Therapy Cohorts | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | n |

at least one ESR1-CCDC170 (exon 2 to 8) fusion |

P-Value | ESR1-CCDC170 (exon 2) fusion | PValue | ESR1-CCDC170 (exon 8) fusion | P-Value | ESR1-AKAP12 | P-Value | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||||

| All patients | 322 | 89 | 27.6% | 50 | 15.5% | 51 | 15.8% | 13 | 4.0% | ||||

| Age at start 1st line treatment (years) | |||||||||||||

| ≤ 50 | 63 | 19 | 30.2% | 0.63 | 12 | 19.0% | 0.62 | 8 | 12.7% | 0.029 | 1 | 1.6% | 0.36 |

| > 50- ≤ 70 | 161 | 37 | 23.0% | 23 | 14.3% | 24 | 14.9% | 7 | 4.3% | ||||

| > 70 | 98 | 33 | 33.7% | 15 | 15.3% | 19 | 19.4% | 5 | 5.1% | ||||

| Menopausal status at start of 1st line treatment | |||||||||||||

| Premenopausal | 64 | 17 | 26.6% | 0.82 | 10 | 15.6% | 0.99 | 8 | 12.5% | 0.41 | 1 | 1.6% | 0.26 |

| Postmenopausal | 257 | 72 | 28.0% | 40 | 15.6% | 43 | 16.7% | 12 | 4.7% | ||||

| Surgery type | |||||||||||||

| Lumpectomy | 95 | 25 | 26.3% | 0.79 | 14 | 14.7% | 0.90 | 15 | 15.8% | 0.83 | 2 | 2.1% | 0.89 |

| Ablation | 169 | 42 | 24.9% | 24 | 14.2% | 25 | 14.8% | 4 | 2.4% | ||||

| Radiotherapy | |||||||||||||

| No | 105 | 30 | 28.6% | 0.33 | 20 | 19.0% | 0.08 | 16 | 15.2% | 0.98 | 2 | 1.9% | 0.74 |

| Yes | 159 | 37 | 23.3% | 18 | 11.3% | 24 | 15.1% | 4 | 2.5% | ||||

| Nodal status | |||||||||||||

| No lymph nodes | 122 | 33 | 27.0% | 0.88 | 19 | 15.6% | 0.99 | 20 | 16.4% | 0.95 | 4 | 3.3% | 0.2 |

| Positive lymph nodes | 130 | 38 | 29.2% | 21 | 16.2% | 22 | 16.9% | 9 | 6.9% | ||||

| Tumor outside lymph nodes | 53 | 15 | 28.3% | 8 | 15.1% | 7 | 13.2% | 0 | 0.0% | ||||

| Not applicable (M1) | 16 | 3 | 18.8% | 2 | 12.5% | 2 | 12.5% | 0 | 0.0% | ||||

| Pathological Tumor classification | |||||||||||||

| pT1 | 85 | 22 | 25.9% | 0.60 | 13 | 15.3% | 0.21 | 14 | 16.5% | 0.90 | 2 | 2.4% | 0.36 |

| pT2 + unknown | 186 | 50 | 26.9% | 25 | 13.4% | 30 | 16.1% | 10 | 5.4% | ||||

| pT3 + pT4 | 51 | 17 | 33.3% | 12 | 23.5% | 7 | 13.7% | 1 | 2.0% | ||||

| Tumor grade | |||||||||||||

| Poor | 160 | 45 | 28.1% | 0.36 | 27 | 16.9% | 0.60 | 27 | 16.9% | 0.60 | 7 | 4.4% | 0.078 |

| Unknown | 81 | 18 | 22.2% | 10 | 12.3% | 10 | 12.3% | 0 | 0.0% | ||||

| Moderate/Good | 74 | 24 | 32.4% | 13 | 17.6% | 13 | 17.6% | 5 | 6.8% | ||||

| Tumor cell content | |||||||||||||

| 30–49% | 27 | 7 | 25.9% | 0.96 | 4 | 14.8% | 0.99 | 2 | 7.4% | 0.25 | 2 | 7.4% | 0.63 |

| 50–70% | 98 | 28 | 28.6% | 15 | 15.3% | 13 | 13.3% | 4 | 4.1% | ||||

| > 70% | 197 | 54 | 27.4% | 31 | 15.7% | 36 | 18.3% | 7 | 3.6% | ||||

| Hormone/ growth factor status (RT-qPCR) | |||||||||||||

| ESR1-negative | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| ESR1-positive | 322 | 89 | 27.6% | 50 | 15.5% | 51 | 15.8% | 13 | 4.0% | ||||

| PR-negative | 63 | 18 | 28.6% | 0.87 | 11 | 17.5% | 0.65 | 11 | 17.5% | 0.70 | 6 | 9.5% | 0.014 |

| PR-positive | 258 | 71 | 27.5% | 39 | 15.1% | 40 | 15.5% | 7 | 2.7% | ||||

| HER2 non-amplified | 279 | 77 | 27.6% | 0.63 | 44 | 15.8% | 0.85 | 45 | 16.1% | 0.81 | 13 | 4.7% | 0.16 |

| HER2 amplified | 41 | 12 | 29.3% | 6 | 14.6% | 6 | 14.6% | 0 | 0.0% | ||||

| CCDC170 negative | 31 | 5 | 16.1% | 0.13 | 2 | 6.5% | 0.15 | 4 | 12.9% | 0.62 | 0 | 0.0% | 0.23 |

| CCDC170 positive | 287 | 83 | 28.9% | 47 | 16.4% | 47 | 16.4% | 13 | 4.5% | ||||

| Adjuvant endocrine therapy | |||||||||||||

| No | 252 | 66 | 26.2% | 0.24 | 38 | 15.1% | 0.64 | 36 | 14.3% | 0.13 | 7 | 2.8% | 0.030 |

| Yes (AI cohort only) | 69 | 23 | 33.3% | 12 | 17.4% | 15 | 21.7% | 6 | 8.7% | ||||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | |||||||||||||

| No | 267 | 76 | 28.5% | 0.47 | 40 | 15.0% | 0.55 | 45 | 16.9% | 0.27 | 12 | 4.5% | 0.36 |

| Yes | 55 | 13 | 23.6% | 10 | 18.2% | 6 | 10.9% | 1 | 1.8% | ||||

| Disease-free interval | |||||||||||||

| ≤ 1 year disease-free | 72 | 23 | 31.9% | 0.47 | 14 | 19.4% | 0.62 | 12 | 16.7% | 0.99 | 2 | 2.8% | 0.45 |

| 1–3 years disease-free | 137 | 37 | 27.0% | 20 | 14.6% | 20 | 14.6% | 8 | 5.8% | ||||

| > 3 years disease-free | 113 | 29 | 25.7% | 16 | 14.2% | 19 | 16.8% | 3 | 2.7% | ||||

| Dominant site of metastasis | |||||||||||||

| Local regional | 29 | 10 | 34.5% | 0.51 | 7 | 24.1% | 0.32 | 4 | 13.8% | 0.36 | 0 | 0.0% | 0.40 |

| Bone | 159 | 40 | 25.2% | 25 | 15.7% | 21 | 13.2% | 6 | 3.8% | ||||

| Other distant metastasis | 130 | 38 | 29.2% | 17 | 13.1% | 25 | 19.2% | 7 | 5.4% | ||||

| Response type | |||||||||||||

| Complete response | 11 | 3 | 27.3% | 0.87 | 2 | 18.2% | 0.73 | 1 | 9.1% | 0.29 | 0 | 0.0% | 0.46 |

| Partial response | 39 | 9 | 23.1% | 3 | 7.7% | 6 | 15.4% | 2 | 5.1% | ||||

| Stable disease over 6 months (SD > 6 m) | 115 | 32 | 27.8% | 16 | 13.9% | 23 | 20.0% | 1 | 0.9% | ||||

| Stable disease for 6 months or less (SD ≤ 6 m) | 13 | 2 | 15.4% | 2 | 15.4% | 1 | 7.7% | 0 | 0.0% | ||||

| Progressive disease (PD) | 83 | 20 | 24.1% | 14 | 16.9% | 8 | 9.6% | 3 | 3.6% | ||||

| Response type | |||||||||||||

| No response | 96 | 22 | 22.9% | 0.50 | 16 | 16.7% | 0.38 | 9 | 9.4% | 0.05 | 3 | 3.1% | 0.50 |

| Response | 165 | 44 | 26.7% | 21 | 12.7% | 30 | 18.2% | 3 | 1.8% | ||||

ESR1 estrogen receptor alpha, CCDC170 coiled-coil domain containing 170, AKAP12 A-Kinase Anchoring Protein 12 gene, ESR1-CCDC170 ESR1-CCDC170 gene fusion, ESR1-AKAP12 ESR1-AKAP12 gene fusion, M1 methastatic stage 1, pT primary tumor, pT1 small primary tumor (tumour is 2 cm across or less), pT2 tumour more than 2 cm but no more than 5 cm across, pT3 T3 tumour bigger than 5 cm across, pT4 tumor with phatological stage, RT-qPCR Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction, PR progesterone receptor, HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor, AI aromatase inhibitors, SD standard deviation, PD progressive disease

Statistically significant differences are indicated in bold

Table 3.

Associations of ESR1 fusions with clinical parameters in prognostic clinical cohort

| LNN ESR + Prognostic cohort | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | n |

at least one ESR1-CCDC170 (exon 2 to 8) fusion |

P-value | ESR1-CCDC170 (exon 2) fusion | P-value | ESR1-CCDC170 (exon 8) fusion | P-value | ESR1-AKAP12 | P-value | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||||||

| All patients | 279 | 70 | 25.1% | 33 | 11.8% | 39 | 14.0% | 5 | 1.8% | |||||

| Age at primary surgery | ||||||||||||||

| ≤ 40 years | 29 | 6 | 20.7% | 0.001 | 4 | 13.8% | 0.38 | 4 | 13.8% | 0.26 | 1 | 3.4% | 0.27 | |

| 41–50 years | 81 | 11 | 13.6% | 5 | 6.2% | 5 | 6.2% | 0 | 0.0% | |||||

| 51–70 years | 125 | 36 | 28.8% | 16 | 12.8% | 21 | 16.8% | 3 | 2.4% | |||||

| > 70 years | 44 | 17 | 38.6% | 8 | 18.2% | 9 | 20.5% | 1 | 2.3% | |||||

| Menopausal status | ||||||||||||||

| Premenopausal | 120 | 19 | 15.8% | 0.002 | 10 | 8.3% | 0.12 | 11 | 9.2% | 0.044 | 1 | 0.8% | 0.29 | |

| Postmenopausal | 159 | 51 | 32.1% | 23 | 14.5% | 28 | 17.6% | 4 | 2.5% | |||||

| Surgery type | ||||||||||||||

| Lumpectomy | 178 | 44 | 24.7% | 0.85 | 19 | 10.7% | 0.43 | 25 | 14.0% | 0.97 | 4 | 2.2% | 0.45 | |

| Ablation | 101 | 26 | 25.7% | 14 | 13.9% | 14 | 13.9% | 1 | 1.0% | |||||

| Radiotherapy | ||||||||||||||

| No | 84 | 24 | 28.6% | 0.38 | 14 | 16.7% | 0.10 | 12 | 14.3% | 0.92 | 1 | 1.2% | 0.62 | |

| Yes | 195 | 46 | 23.6% | 19 | 9.7% | 27 | 13.8% | 4 | 2.1% | |||||

| Nodal status | ||||||||||||||

| No lymph nodes | 279 | 70 | 25.1% | 33 | 11.8% | 39 | 14.0% | 5 | 1.8% | |||||

| Positive lymph nodes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| Tumor outside lymph nodes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| Pathological Tumor classification | ||||||||||||||

| pT1 | 151 | 34 | 22.5% | 0.28 | 17 | 11.3% | 0.61 | 16 | 10.6% | 0.08 | 2 | 1.3% | 0.1 | |

| pT2 + unknown | 119 | 32 | 26.9% | 14 | 11.8% | 20 | 16.8% | 2 | 1.7% | |||||

| pT3 + pT4 | 9 | 4 | 44.4% | 2 | 22.2% | 3 | 33.3% | 1 | 11.1% | |||||

| Tumor grade | ||||||||||||||

| Poor | 131 | 36 | 27.5% | 0.60 | 21 | 16.0% | 0.06 | 21 | 16.0% | 0.56 | 3 | 2.3% | 0.84 | |

| Unknown | 81 | 20 | 24.7% | 9 | 11.1% | 11 | 13.6% | 1 | 1.2% | |||||

| Moderate/Good | 67 | 14 | 20.9% | 3 | 4.5% | 7 | 10.4% | 1 | 1.5% | |||||

| Tumor cell content | ||||||||||||||

| 30–49% | 31 | 9 | 29.0% | 0.82 | 6 | 19.4% | 0.38 | 4 | 12.9% | 0.86 | 1 | 3.2% | 0.81 | |

| 50–70% | 69 | 16 | 23.2% | 7 | 10.1% | 11 | 15.9% | 1 | 1.4% | |||||

| > 70% | 179 | 45 | 25.1% | 20 | 11.2% | 24 | 13.4% | 3 | 1.7% | |||||

| Hormone/ growth factor status (RT-qPCR) | ||||||||||||||

| ESR1 negative | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| ESR1 positive | 279 | 70 | 25.1% | 33 | 11.8% | 39 | 14.0% | 5 | 1.8% | |||||

| PR negative | 62 | 16 | 25.8% | 0.88 | 9 | 14.5% | 0.46 | 8 | 12.9% | 0.78 | 2 | 3.2% | 0.93 | |

| PR positive | 217 | 54 | 24.9% | 24 | 11.1% | 31 | 14.3% | 3 | 1.4% | |||||

| HER2 non-amplified | 233 | 62 | 26.6% | 0.15 | 29 | 12.4% | 0.30 | 34 | 14.6% | 0.61 | 4 | 1.7% | 0.78 | |

| HER2 amplified | 43 | 7 | 16.3% | 3 | 7.0% | 5 | 11.6% | 1 | 2.3% | |||||

| CCDC170 negative | 26 | 4 | 15.4% | 0.23 | 2 | 7.7% | 0.49 | 3 | 11.5% | 0.70 | 0 | 0.0% | 0.47 | |

| CCDC170 positive | 252 | 66 | 26.2% | 31 | 12.3% | 36 | 14.3% | 5 | 2.0% | |||||

| Disease-free interval | ||||||||||||||

| ≤ 1 year disease-free | 20 | 7 | 35.0% | 0.011 | 2 | 10.0% | 0.08 | 4 | 20.0% | 0.006 | 0 | 0.0% | 0.57 | |

| 1–3 years disease-free | 71 | 18 | 25.4% | 10 | 14.1% | 14 | 19.7% | 2 | 2.8% | |||||

| > 3 years disease-free | 188 | 45 | 23.9% | 21 | 11.2% | 21 | 11.2% | 3 | 1.6% | |||||

| Adjuvant endocrine therapy | ||||||||||||||

| No | 279 | 66 | 23.7% | 33 | 11.8% | 39 | 14.0% | 5 | 1.8% | |||||

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | ||||||||||||||

| No | 279 | 66 | 23.7% | 33 | 11.8% | 39 | 14.0% | 5 | 1.8% | |||||

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

ESR1 estrogen receptor alpha, CCDC170 coiled-coil domain containing 170, AKAP12 A-Kinase Anchoring Protein 12 gene, ESR1-CCDC170 ESR1-CCDC170 gene fusion, ESR1-AKAP12 ESR1-AKAP12 gene fusion, pT primary tumor, pT1 small primary tumor (tumour is 2 cm across or less), pT2 tumour more than 2 cm but no more than 5 cm across, pT3 T3 tumour bigger than 5 cm across, pT4 tumor with phatological stage, RT-qPCR Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction, PR progesterone receptor, HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor

Statistically significant differences are indicated in bold

RNA isolation and RT-qPCR

Total RNA isolation from human breast cancer tissue, breast cancer cell line models and quality control were performed as previously described [20]. Next, cDNA was generated by a cycle at 48 °C for 30 min with RevertAid H-minus (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cDNA was then pre-amplified for specific genes as previously described [20]. Briefly, 2 µL of cDNA (0.1 to 1 ng/ µL) was subject to a pre-amplification of 15 cycles using a multiple loci target-specific amplification for ESR1 fusions with AKAP12, ARMT1 and CCDC170 and two reference genes, the Epithelian Cell Adhesion Molecule (EPCAM) and the Hypoxanthine Phosphoribosyltransferase 1 (HPRT1), with TaqMan PreAmp Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), as recommended by the manufacturer. Pre-amplified products were then diluted 12-fold in LoTE buffer (3 mM Tris–HCl/0.2 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) prior to downstream analysis. Next, 5 µL diluted pre-amplified samples were subjected to a TaqMan probe based real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) for each gene combination, according to the manufacturer’s instructions, in a MX3000P Real-Time PCR System (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). The average expression of HPRT1 and the epithelial marker EPCAM was used as reference to control RNA quality and calculate the expression levels of target genes, as previously described [20]. Only those samples with a ∆Cq > 25 relative to the two reference genes were used for further evaluation of gene fusions, as previously described [24–26]. Additional file 1 describes the primer sets used in the pre-amplification combination, as well as the Taqman qPCR used to quantify the fusions and reference genes. For ESR1-CCDC170 fusion transcripts, the variants in which exon 2 of ESR1 is fused to the coding region (exon 2 to 11) of CCDC170 were examined (E2-E2, E2-E3, E2-E4, E2-E5, E2–E6, E2–E7, E2–E8, E2–E10 and E2-E11). Samples with a ∆Cq > 25 relative to the reference genes were afterwards validated by MultiNA analysis (Shimadzu Europe, Duisburg, Germany). Only those samples with a MultiNA fusion product of the expected size were considered positive for the fusion transcripts (Additional file 2). The detection of ESR1-CCDC170 fusion transcripts with RT-qPCR and MultiNA analysis was verified and confirmed in a set of fusion-positive reported breast cancer cell lines (Additional files 3, 4 and 5).

Statistical analysis

All data were entered in SPSS version 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) to generate the tables and perform the statistical analyses. For contingency tables, the Pearson Chi-Square Test was used. All P-values are 2-sided and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Association of ESR1 with its CCDC170, AKAP12 and ARMT1 fusion partner

The presence of the ESR1 fusions with AKAP12, ARMT1 and CCDC170 (exon 2 to exon 11) was evaluated in breast cancer tissue samples from 732 breast cancer patients. Fusion transcripts were predominantly detected in the ESR1 + population, with CCDC170, AKAP12 or ARMT1 fusion transcripts observed in 27.6%, 4.04% and 1.4% of the ER-positive cases respectively, and seen in 2.3%, 0.8% and 0% of the ESR1- cases respectively (P < 0.001, Fisher’s exact test two tailed. Table 4 and Additional file 6). In ER-positive tumors, full length ESR1 and CCDC170 mRNA levels were strongly correlated (R2 = 0.31, P < 0.0001) (Additional file 7A) and transcript levels of both were significantly higher in the group of samples with an ESR1-CCDC170 fusion transcript when compared to the group without [Student T-Test P = 0.0316 and 0.0001, respectively (Additional file 7B).

Table 4.

Prevalence of ESR1 fusions in the different analyzed cohorts

|

At least one ESR1-CCDC170 (exon 2 to 8) fusion |

ESR1-CCDC170 exon 2 |

ESR1-CCDC170 exon 8 |

ESR1_AKAP12 | ESR1-ARMT1 | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Count | no | yes | % | % of total count | no | yes | % | no | yes | % | no | yes | % | % of total count | no | yes | % | % of total count | ||

| All samples studied | 788 |

ESR1 negative |

128 | 3 | 2.3% | 22.0% | 128 | 3 | 2.29% | 130 | 1 | 0.76% | 130 | 1 | 0.76% | 2.7% | 131 | 0 | 0.00% | 1.1% |

| ESR1 positive | 487 | 170 | 25.9% | 565 | 92 | 14.00% | 556 | 101 | 15.37% | 637 | 20 | 3.04% | 648 | 9 | 1.37% | |||||

| 1st line Tamoxifen | 235 | ESR1 negative | 0 | 0 | 0% | 24.7% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 2.6% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0.4% |

| ESR1 positive | 177 | 58 | 24.7% | 204 | 31 | 13.19% | 201 | 34 | 14.47% | 229 | 6 | 2.55% | 234 | 1 | 0.43% | |||||

| 1st line AI | 87 | ESR1 negative | 0 | 0 | 0% | 35.6% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 8.0% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 3.4% |

| ESR1 positive | 56 | 31 | 35.6% | 68 | 19 | 21.84% | 70 | 17 | 19.54% | 80 | 7 | 8.05% | 84 | 3 | 3.45% | |||||

| 1st line endocrine cohort | 322 | ESR1 negative | 0 | 0 | 0% | 27.6% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 4.0% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 1.2% |

| ESR1 positive | 233 | 89 | 27.6% | 272 | 50 | 15.53% | 271 | 51 | 15.84% | 309 | 13 | 4.04% | 318 | 4 | 1.24% | |||||

| Primary cohort | 566 | ESR1 negative | 113 | 3 | 2.6% | 17.8% | 113 | 3 | 2.59% | 115 | 1 | 0.86% | 115 | 1 | 0.86% | 1.9% | 116 | 0 | 0% | 0.7% |

| ESR1 positive | 352 | 98 | 21.8% | 403 | 47 | 10.44% | 392 | 58 | 12.89% | 440 | 10 | 2.22% | 446 | 4 | 0.89% | |||||

| Primary LNP cohort | 192 | ESR1 negative | 26 | 0 | 0.0% | 15.6% | 26 | 0 | 0.00% | 26 | 0 | 0.00% | 26 | 0 | 0.00% | 2.6% | 26 | 0 | 0% | 0.5% |

| ESR1 positive | 136 | 30 | 18.1% | 152 | 14 | 8.43% | 148 | 18 | 10.84% | 161 | 5 | 3.01% | 165 | 1 | 0.60% | |||||

| Primary LNN cohort | 369 | ESR1 negative | 87 | 3 | 3.3% | 18.7% | 87 | 3 | 3.33% | 89 | 1 | 1.11% | 89 | 1 | 1.11% | 1.6% | 90 | 0 | 0.0% | 0.8% |

| ESR1 positive | 213 | 66 | 23.7% | 246 | 33 | 11.83% | 240 | 39 | 13.98% | 274 | 5 | 1.79% | 276 | 3 | 1.08% | |||||

| Normal breast tissue of breast cancer patients | 36 | ESR1 negative | 0 | 0 | 0% | 66.7% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0.0% | |

| ESR1 positive | 12 | 24 | 66.7% | 18 | 18 | 50.0% | 23 | 13 | 36.1% | 36 | 0 | 0.0% | 36 | 0 | 0.0% | |||||

| Tissue of breast fibroadenoma's | 16 | ESR1 negative | 0 | 0 | 0% | 25.0% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0.0% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0.0% |

| ESR1 positive | 12 | 4 | 20.0% | 16 | 0 | 0.0% | 16 | 4 | 20.0% | 16 | 0 | 0.0% | 16 | 0 | 0.0% | |||||

| Tissue of breast DCIS | 13 | ESR1 negative | 0 | 0 | 0% | 7.7% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0.0% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0.0% |

| ESR1 positive | 12 | 1 | 7.7% | 13 | 0 | 0.0% | 13 | 0 | 0.0% | 13 | 0 | 0.0% | 13 | 0 | 0.0% | |||||

| Normal breast tissue of healthy women | 10 | ESR1 negative | 0 | 0 | 0% | 10.0% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0.0% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0.0% |

| ESR1 positive | 9 | 1 | 10.0% | 9 | 1 | 10.0% | 10 | 0 | 0.0% | 10 | 0 | 0.0% | 10 | 0 | 0.0% | |||||

ESR1 estrogen receptor alpha, CCDC170 coiled-coil domain containing 170, AKAP12 A-Kinase Anchoring Protein 12 gene, ARMT1 Acidic Residue Methyltransferase 1, ESR1-CCDC170 ESR1-CCDC170 gene fusion, ESR1-AKAP12 ESR1-AKAP12 gene fusion, ESR1-ARMT1 ESR1-ARMT1 gene fusion, 1st first line treatment, LNP lymph node positive disease, LNN lymph node negative disease, DCIS Ductal carcinoma in situ

Statistically significant differences are indicated in bold

Prevalence of ESR1 fusion genes in normal mammary tissue, benign lesions and carcinoma in situ of the breast

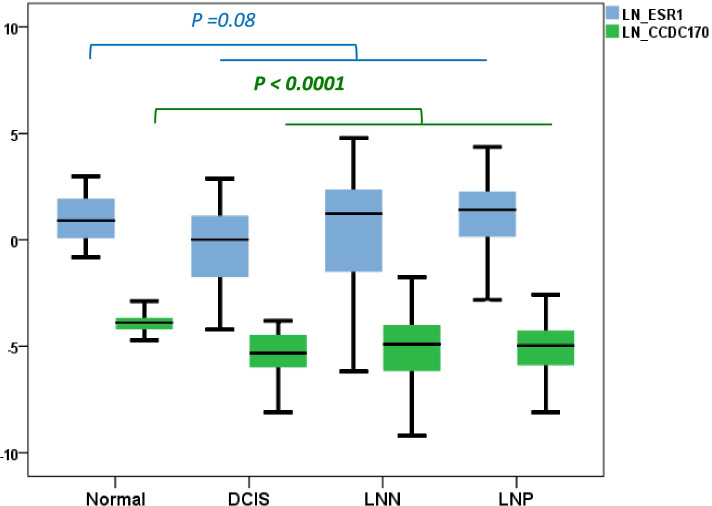

While AKAP12 and ARMT1 fusion transcripts were not found in 36 non-malignant breast tissues taken at a distance of the primary tumor, ESR1-CCDC170 fusion transcripts were detected in 67% of these normal breast tissues of patients with diagnosed breast cancer (Table 4). Note that CCDC170, but not ESR1, mRNA levels were significantly higher in these normal (adjacent to tumor) tissues than in cancer tissue (Kruskal Wallis Test P < 0.0001, (Fig. 2). To investigate this unexpectedly high incidence in more detail, we analyzed normal breast tissues of ten women without diagnosed breast cancer, 16 benign fibroadenomas and 13 ductal carcinomas in situ (DCIS) tissues, all of them ESR1-positive. In addition, we measured the fusion transcripts in three sets of patient-matched normal breast and primary tumor carcinomas and four patient-matched sets of primary breast tumors and metastatic lymph nodes, also all ESR1-positive. In none of these cases did we detect an ESR1 fusion transcripts with AKAP12 or ARMT1. However, one of the breast tissues of women without breast cancer diagnosis (10%) showed ESR1-CCDC170 exon 2 (E2-E2) fusion transcripts, one of the DCIS cases (7.7%) had ESR1-CCDC170 exon 6 (E2-E6) fusion transcripts, and four patients with fibroadenoma (25%) had ESR1-CCDC170 exon 8 (E2-E8) fusion transcripts (Table 4 and Additional file 6). For one out of the three matched normal-tumor cases we found an ESR1-CCDC170 exon 8 fusion in both the primary tumor and the normal breast tissue taken at a distance from the primary tumor. Finally, for two out of the four patients of which we had a matched primary tumor and lymph node metastasis, an ESR1-CCDC170 exon 2 fusion was present in both the primary tumor and the lymph node metastasis.

Fig. 2.

Expression of ESR1 and CCDC170 genes in breast tissues. Relative CCDC170 (blue box) and ESR1 (green box) mRNA levels normalized to HPRT1 gene are showed in the y-axis and were measured by RT-qPCR in normal (adjacent to tumor), benign (DCIS) and carcinoma (LNN and LNP) breast tissues. The box plots show interquartile ranges (IQR) together with the median (black horizontal line) of the ESR1 and CCDC170 mRNA levels for the different conditions. DCIS: ductal carcinomas in situ; LNP: Lymph node positive; LNN: Lymph node negative

Prevalence of ESR1 fusion genes in breast tumor tissues

Since fusion transcripts were predominantly detected in the ESR1 + population, we decided to investigate the clinical relevance of these transcripts in primary tumors. To this end, we stratified ESR1 + patients in two distinct cohort: a predictive cohort of advanced BC patients treated with first-line endocrine therapy and a prognostic cohort of primary BC patients with lymph node negative disease (LNN) who did not receive any adjuvant systemic treatment.

In these two ESR1 + cohorts, ESR1-ARMT1 fusion transcripts were detected in four patients of the predictive cohort (1.2%) and in three patients of the prognostic cohort (1.1%). Due to the low incidence of this ESR1-ARMT1 fusion transcript, it was not further pursued. ESR1-AKAP12 fusion transcripts were more common, and observed in 13 patients of the predictive cohort (4.0%) and in five patients of the prognostic cohort (1.8%). The ESR1-CCDC170 fusion transcripts, however, were the most prevalent and detected in the predictive cohort in 89 patients (27.6%) and in the prognostic cohort in 70 patients (25.1%). Interestingly, all patients harboring an ESR1-ARMT1 or an ESR1-AKAP12 fusion were also positive for an ESR1-CCDC170 rearranged transcript. Moreover, we noticed the coexistence of the three fusions in two subjects. Of all the breast tissue samples studied, the most prominent ESR1-CCDC170 fusion transcripts found involved exon 2 of ESR1 fused with exon 2 (14%) and exon 8 (15.37%) of CCDC170 (Table 4).

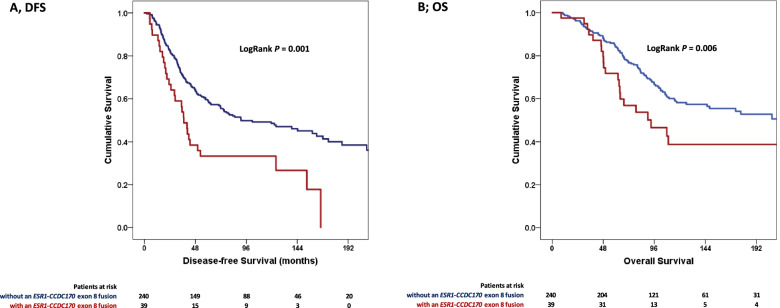

Association of ESR1 fusion genes with DFS and OS in the prognostic cohort

The presence of ESR1-CCDC170 fusion transcripts in the primary tumor of our ESR1 + LNN patients predicted a shorter disease-free survival in a Cox proportional hazards regression survival analysis (HR ± 95% CI: 1.44 (1.01 – 2.05), P = 0.044) (Table 5). We decided to investigate the two frequently present ESR1-CCDC170 fusion transcripts (E2-E2 and E2-E8). Analyzing the ESR1-CCDC170 exon 2 and exon 8 separately, showed that the fusion with exon 8 of CCDC170 on its own associated with a short disease free survival (DFS; HR ± 95% CI: 1.95 (1.30 – 2.93), P = 0.001). No association with disease free survival was seen for ESR1-AKAP12 fusion transcripts (HR ± 95% CI: 1.23 (0.39 – 3.87), P = 0.72). Concerning overall survival, only the presence of an ESR1-CCDC170 exon 8 fusion predicted a shorter overall survival time (HR ± 95% CI: 1.85 (1.18 – 2.90, P = 0.007) The DFS and OS Kaplan Meier curves as a function of ESR1-CCDC170 exon 8 fusion transcripts are shown in Fig. 3A and Fig. 3B, respectively. A multivariate analysis was performed in which age at primary surgery, pathological tumor classification, tumor grade, progesterone receptor and HER2 status were included. The analysis revealed HER2 status as a significant prognostic factor for overall survival, but not for DFS (P = 0.36) (Table 5). In this analyses, the presence of ESR1-CCDC170 exon 8 fusion transcripts was an independent prognostic factor for both DFS (HR ± 95% CI: 1.82 (1.20 – 2.75), P = 0.005) and OS (HR ± 95% CI: 1.71 (1.08 – 2.72), P = 0.001).

Table 5.

Uni- and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression survival analysis

| Univariate model DFS | Multivariate model DFS | Univariate model OS | Multivariate model OS | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | n | HR | (95% CI) | P | HR | (95% CI) | P | HR | (95% CI) | P | HR | (95% CI) | P | ||||

| 279 | |||||||||||||||||

| Age at primary surgery | 0.25 | 0.31 | 0.19 | 0.18 | |||||||||||||

| ≤ 40 years | 29 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 41–50 years | 81 | 0.59 | 0.35 | 1.00 | 0.049 | 0.60 | 0.35 | 1.02 | 0.06 | 0.53 | 0.30 | 0.96 | 0.036 | 0.51 | 0.28 | 0.94 | 0.032 |

| 51–70 years | 125 | 0.73 | 0.44 | 1.19 | 0.20 | 0.72 | 0.44 | 1.18 | 0.19 | 0.75 | 0.44 | 1.28 | 0.30 | 0.72 | 0.42 | 1.26 | 0.25 |

| > 70 years | 44 | 0.78 | 0.43 | 1.40 | 0.41 | 0.71 | 0.39 | 1.28 | 0.25 | 0.73 | 0.37 | 1.43 | 0.35 | 0.73 | 0.37 | 1.47 | 0.38 |

| Menopausal status | |||||||||||||||||

| Premenopausal | 120 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Postmenopausal | 159 | 1.01 | 0.73 | 1.38 | 0.96 | 1.06 | 0.74 | 1.53 | 0.73 | ||||||||

| Pathological Tumor classification | 0.009 | 0.037 | 0.017 | 0.019 | |||||||||||||

| pT1 | 151 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| pT2 + unknown | 119 | 1.54 | 1.12 | 2.11 | 0.007 | 1.35 | 0.98 | 1.88 | 0.069 | 1.30 | 0.90 | 1.87 | 0.165 | 1.19 | 0.81 | 1.74 | 0.375 |

| pT3 + pT4 | 9 | 2.31 | 1.00 | 5.32 | 0.049 | 2.47 | 1.07 | 5.75 | 0.035 | 3.26 | 1.39 | 7.62 | 0.006 | 3.45 | 1.45 | 8.19 | 0.005 |

| Grade | < 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.033 | 0.082 | |||||||||||||

| poor | 131 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| unknown | 81 | 1.36 | 0.97 | 1.91 | 0.076 | 1.40 | 0.98 | 1.99 | 0.064 | 0.89 | 0.59 | 1.34 | 0.577 | 0.97 | 0.64 | 1.48 | 0.894 |

| moderate and good | 67 | 0.52 | 0.33 | 0.82 | 0.004 | 0.57 | 0.36 | 0.89 | 0.014 | 0.51 | 0.31 | 0.85 | 0.009 | 0.57 | 0.34 | 0.94 | 0.029 |

| ER | 279 | 1.11 | 0.98 | 1.25 | 0.10 | 0.99 | 0.86 | 1.14 | 0.92 | ||||||||

| PR | |||||||||||||||||

| negative | 62 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| positive | 217 | 0.66 | 0.46 | 0.93 | 0.019 | 0.68 | 0.47 | 0.98 | 0.037 | 0.49 | 0.33 | 0.73 | < 0.001 | 0.56 | 0.37 | 0.85 | 0.007 |

| HER2 statusa | |||||||||||||||||

| not amplified | 233 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| amplified | 43 | 1.21 | 0.80 | 1.84 | 0.36 | 1.82 | 1.17 | 2.84 | 0.008 | 1.72 | 1.08 | 2.73 | 0.022 | ||||

| Univariate model PFS | Univariate model post-relapse survival | ||||||||||||||||

| 1st line Tamoxifen | 235 | ||||||||||||||||

| at least one ESR1-CCDC170 (exon 2 to 8) fusion | 0.96 | 0.71 | 1.30 | 0.81 | 1.16 | 0.85 | 1.60 | 0.35 | |||||||||

| ESR1-AKAP12 | 1.37 | 0.61 | 3.10 | 0.44 | 1.92 | 0.84 | 4.35 | 0.12 | |||||||||

| 1st line AI | 87 | ||||||||||||||||

| at least one ESR1-CCDC170 (exon 2 to 8) fusion | 0.85 | 0.53 | 1.37 | 0.50 | |||||||||||||

| ESR1-AKAP12 | 1.62 | 0.73 | 3.60 | 0.24 | |||||||||||||

| Separately added to the base model | |||||||||||||||||

| Univariate model DFS | Multivariate model DFS | Univariate model OS | Multivariate model OS | ||||||||||||||

| at least one ESR1-CCDC170 (exon 2 to 8) fusion | |||||||||||||||||

| negative | 213 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| positive | 66 | 1.44 | 1.01 | 2.05 | 0.044 | 1.33 | 0.92 | 1.92 | 0.13 | 1.67 | 1.13 | 2.47 | 0.010 | 1.54 | 1.02 | 2.33 | 0.042 |

| ESR1-CCDC170 (exon 2) fusion | |||||||||||||||||

| negative | 246 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| positive | 33 | 1.40 | 0.89 | 2.21 | 0.14 | 1.75 | 1.07 | 2.87 | 0.026 | 1.38 | 0.82 | 2.33 | 0.22 | ||||

| ESR1-CCDC170 (exon 8) fusion | |||||||||||||||||

| negative | 240 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| positive | 39 | 1.95 | 1.30 | 2.93 | 0.001 | 1.82 | 1.20 | 2.75 | 0.005 | 1.85 | 1.18 | 2.90 | 0.007 | 1.71 | 1.08 | 2.72 | 0.023 |

| ESR1-AKAP12 | |||||||||||||||||

| negative | 274 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| positive | 5 | 1.23 | 0.39 | 3.87 | 0.72 | 2.45 | 0.90 | 6.65 | 0.08 | ||||||||

DFS disease free survival, OS overall survival, HR hazard ratio, CI interval of confidence, pT1 small primary tumor (tumour is 2 cm across or less), pT2 tumour more than 2 cm but no more than 5 cm across, pT3 T3 tumour bigger than 5 cm across pT4 tumor with phatological stage, ER estrogen receptor, PR progesterone receptor, HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor, AI aromatase inhibitors, ESR1-CCDC170 ESR1-CCDC170 gene fusion, ESR1-AKAP12 ESR1-AKAP12 gene fusion. Statistically significant differences are indicated in bold

a due to unknown data numbers do not add up to 279

Fig. 3.

Disease free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) in the prognostic cohort. The DFS and OS Kaplan Meier curves in ER-positive LNN patients. A DFS of patients with or without ESR1-CCDC170 exon 8 fusion gene; B OS of patients with or without ESR1-CCDC170 exon 8 fusion gene. The reported P-value is from a log-rank test and the test statistics from Cox regression analyses

Association of ESR1 fusion genes with clinical characteristics, PFS and post-relapse overall survival in advanced BC patients

The fusion transcripts were related with traditional clinical parameters, with response to first-line endocrine therapy in the predictive cohort (n = 322; tamoxifen (n = 235), aromatase inhibitors (n = 87)) (Table 2). In the predictive cohort ESR1-CCDC170 fusion transcripts showed an association with age at start of first-line treatment, whereas ESR1-AKAP12 fusion transcripts were enriched in patients with progesterone-negative primary tumors at time of surgery and in AI-treated patients who received adjuvant tamoxifen. No relation with PFS after first-line tamoxifen (n = 235) was found in our Cox proportional hazards regression survival analysis for the ESR1-CCDC170 fusion transcripts (HR ± 95% CI: 0.96 (0.71 – 1.30), P = 0.81) nor for the ESR1-AKAP12 fusion transcripts (HR ± 95% CI: 1.37 (0.61 – 3.10), P = 0.44) (Table 5). In addition, the presence of these fusion transcripts did not affect the time from relapse to death (post-relapse survival, HR ± 95% CI: 1.16 (0.85 – 1.60), P = 0.35 and 1.92 (0.84 – 4.35), P = 0.12, for ESR1 fusions with CCDC170 and AKAP12, respectively) (Table 5). Similarly, also no association with PFS for first-line aromatase inhibitors (n = 87) was found for ESR1-CCDC170 fusion transcripts (HR ± 95% CI: 0.85 (0.53 – 1.37), P = 0.50) nor for the ESR1-AKAP12 fusion transcripts (HR ± 95% CI: 1.62 (0.73 – 3.60), P = 0.24). With data available for only 27 patients post-relapse, we did not analyze post-relapse survival for aromatase inhibitors. Moreover, no-significant associations with PFS were seen when the ESR1-CCDC170 exon 2 and exon 8 fusion transcripts were analyzed separately (Table 5).

Discussion

The genetic landscape contributing to de novo or acquired resistance to endocrine therapy in breast cancer patients is not completely understood yet. In this study, we investigated the occurrence of recurrent fusion transcripts between ESR1 and three different loci adjacent to ESR1 (CCDC170, AKAP12 and ARMT1) and correlated their presence with clinical outcome. All of the fusion transcripts analyzed are recurrent and most frequently present in ER-positive disease and among them ESR1-CCDC170 fusion transcripts were the most predominant. As proposed by others [10, 13], the presumption was that these fusion transcripts, which are considered to cause constitutive ER signaling, might signify resistance to endocrine therapy. However, in patients with advanced breast cancer, we did not find that the presence of any of these fusion transcripts is associated with outcome to endocrine therapy whether it concerned first line tamoxifen or an aromatase inhibitor. Importantly, smaller size effects from these the variants may be undetected due to the relatively small sample size of the study cohort, 87 patients treated with aromatase inhibitors and 235 subjects with tamoxifen. In contrast, in patients with primary BC and not receiving adjuvant systemic hormone treatments, we found that fusion between ESR1 and CCDC170 in general, and between exon 2 of ESR1 and exon 8 of CCDC170 in particular, predicted in uni- and multivariable analyses shorter disease free survival as well as shorter overall survival. Thus, ESR1 and CCDC170 fusion transcript pinpoint cancers with an adverse outcome.

Understanding the molecular mechanisms that underlay the origin of fusion transcripts could help to comprehend the role of these fusions in carcinogenesis as well as improve the diagnosis of cancer patients [10, 13]. Although the progress in DNA sequencing enhanced detection of recurrent and pathological breast cancer fusions, the complexity of underlying genomic rearrangement patterns makes their characterization at the DNA level often difficult. The fusion between ESR1 and its neighboring gene CCDC170 are potentially generated by tandem duplication [9, 13, 27, 28], which is also causing other genetic rearrangements in cancer [9, 29, 30]. Kim et al. found a region within the ESR1 genomic locus most vulnerable to DNA strand breakage, which often included intron 6 region of its neighboring gene CCDC170, resulting in oncogenic mRNA ESR1-CCDC170 fusion transcript of exons 2 of ESR1 connected to exon 2–11 of CCDC170, i.e. the C-terminal domain of CCDC170 [31]. Irrespective of mechanisms causing the gene fusions, they occur in a patient-specific manner, which makes their identification at the DNA level less suitable for routine diagnostics. Our method to analyze fusion transcripts is much less dependent on exact position of the underlying gene fusion at the DNA level and is therefore better suited to evaluate as a general biomarker in large patient cohorts. However, an important caveat for detecting gene fusions at the transcript level is the fact that it cannot distinguish between fusion transcripts arising from actual genetic rearrangements and those that arise from transcription reading from one gene into the next without a genetic cause. Interestingly, Giltnane et al. rejected the option of a run-on transcription for these genes since the 5’end of ESR1 is fused to the 3’ends of CCDC170 and AKAP12, which are upstream of ESR1 gene [10]. Finally, the generation of artefactual fusion sequences, which are randomly ligated during the sequencing procedure, might happen, as previously reported by Veeraraghavan et al. [13]. Overall, we performed RT-qPCR analysis and investigated RNA not DNA, therefore we cannot tell whether fusion transcripts are the results of (DNA) rearrangements. Furthermore, to our great surprise, ESR1-CCDC170 and ESR1-AKAP12 fusions were detected in ER-negative patients even if at low frequency (2.3% and 0.8%, respectively). Besides sampling bias, this finding might be explained by a challenge in ER and PR determination. Althought immunohistochemistry (IHC) is the “gold standard” to determine the surrogate markers ER and PR for breast cancer classification, several studies addressed limitations in IHC by shedding light on the discordance rates in scoring hormone receptor status with negative and false-positive rates in ER and PR statuses higher than 20% [32, 33]. Similarly, a recently article by Fakhri et all. found that 12.5% of samples negative for ER by IHC were positive via microarray analysis [34]. In this context, we performed RT-qPCR to accurately determine hormone receptor status. However, this method could be subject to bias during RNA measurement. Moreover, a recently study found that in primary breast cancers, the ER-negative phenotype is not the result of mutations in ER gene, but is due to deficient ER expression at the transcriptional or post-transcriptional level [35]. Therefore, we might hypothesize that the ER expression might be restored in ER-negative patients due to the strongly impact of the signaling environment, as already demonstrated for breast cancer cells via inhibition of DNA methylation or histone deacetylation [36].

Another interesting question regards the biological significance of clinically relevant fusion transcripts. Gene fusions and their products (RNAs and proteins) are assumed to be exclusive to cancer. However, RNA-sequencing analyses from normal appearing margins of cancerous specimens showed fusion transcripts also in normal tissues [37]. In fact, oncogenic rearrangements, such as the EML4-ALK [38], NPM-ALK [39], JAZF1-JJAZ1 [40] and BCR-ABL1 [41] fusions are also expressed at a low level in histologically non-neoplastic tissues [9]. In our study, expression of ESR1 fused to exons 2 and exon 8 of CCDC170 was found in mammary epithelial tissues derived from women without diagnosis of breast cancer, and in cases with (benign) fibroadenomas, respectively. Also in early stages of breast cancer, like DCIS, we detected fusion transcripts. Moreover, ESR1-CCDC170 fusion transcripts were also detected in normal breast tissues of patients with diagnosed breast cancer. This argues that a percentage may be transcript read-through instead of fusion transcripts arising from gene fusions.

According to our results, the expression of ESR1-CCDC170 exon 2 and exon 8 fusion transcripts were linked to a less favorable disease in BC patients who not received adjuvant systemic treatment. Overall, our results are in agreement with those reported by Veeraraghavan et al. which showed that ESR1-CCDC170 fusions, when introduced into ER-positive breast cancer cells, leads to a markedly increase of cell motility and colony-forming ability, increase in S-G2/M phase cells and a decrease in G0/G1 phase cells. Although several functional studies [9, 42] demonstrated a role of ESR1-CCDC170 fusions in endocrine therapy resistance, no relationship between fusion transcripts and treatment outcome was observed in our predictive cohort. Overall, since ESR1-CCDC170 fusions in our study demonstrated no predictive value for endocrine therapy resistance, their prognostic value might be explained by the recurrent incidence of read-through events during cell cycle progression. This latter has been exemplified with the abundance of CTSD-IFITM10 readthrough fusions during breast cancer cell proliferation [43].

Conclusions

The most important conclusion from our work is that among the fusion transcripts evaluated measuring ESR1-CCDC170 exon 8 fusion transcripts in primary breast cancers has diagnostic potential as it identifies a more aggressive subset of ER-positive breast cancer patients. Furthermore, with our study we demonstrated that ESR1-CCDC170 fusion transcript does not predict endocrine therapy resistance in our setting.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Assays used for ESR1-CCDC170 fusion analyses. F: forward primer; R: reverse primer

Additional file 2. Expected ESR1-CCDC170 fusion products. In blue are shown the expected sizes of fusion products while in violet are depicted aspecific products, which can be generated during RT-qPCR

Additional file 3. Expression of CCDC170 wildtype and fusion protein evaluated by immunohistochemical staining (IHC) and western blotting in breast cancer cell lines. A. IHC performed on a cell line microarray of 44 breast cancer cell lines show a histoscore correlation between the cytoplasmic CCDC170 and CCDC170 wildtype as well as between ESR1-CCDC170 exon 8 fusion transcript levels and CCDC170 wildtype, but not with exon 2 fusion transcript levels. B. Western blotting analyses demonstrated the expression of CCDC170 fusion protein. The exon 2 ESR1 – exon 8 CCDC170 fusion product (~30kD) was detected in ZR75.1 and HCC1500, but not in MCF-7. The exon 2- exon 10 CCDC170 fusion protein (~14kD) was also observed, but only in HCC1500

Additional file 4. ESR1-CCDC170 fusions confirmation by MultiNA in a subset of Breast cancer cell lines. If the Taqman probe-based RT-qPCR generated a positive Cq value, the expected fusion gene product sizes were validated by MultiNA. Only products with a MultiNA fusion product of the expected size and a ∆Cq ≥ -25 relative to the two reference genes were considered positive for the fusion product. MultiNA analyses confirmed the CCDC170 RNA fusion products in three breast cancer cell lines. Red boxes indicate fusion expression with correct fragment sizes

Additional file 5. Expression of ESR1 fusions and reference (ESR1 and CCDC170) genes in a panel of 54 breast cancer cell lines. Genes with expression level above the threshold are indicated in orange

Additional file 6. Details of prevalence of ESR1-CCDC170 (exon 1-11) fusion genes in the different analyzed cohorts. ESR1: Estrogen Receptor 1 gene; AI: Aromatase Inhibitor; LNP: Lymph node positive; LNN: Lymph node negative; DCIS: ductal carcinomas in situ

Additional file 7. ESR1 and CCDC170 wildtype expression in ER-positive tumors compared between CCDC170 fusion-negative and positive cases. A. Correlation between CCDC170 and ESR1 wildtype expression measured by RT-qPCR. B. CCDC170 and ESR1 wildtype mRNA levels were measured by RT-qPCR in samples with ESR1-CCDC170 fusion transcript and compared to the group without fusion transcript. The box plots show interquartile ranges (IQR) together with the median (black horizontal line) of the ESR1 and CCDC170 mRNA levels for the different conditions. Group 0: CCDC170-fusion negative cases (n =387); Group 1: CCDC170-fusion positive cases (n =159)

Acknowledgements

The authors are especially grateful to all patients, to Steven van Laere and Luc Dirix—Department Oncology, Antwerp University, Belgium and to Sabine C. Linn – Department of Medical Oncology, Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, the Netherlands for their contribution of tissues from patients treated with 1st line aromatase inhibitor.

Abbreviations

- AI

Aromatase inhibitor

- ARMT1

Acidic Residue Methyltransferase 1

- AKAP12

A-Kinase Anchoring Protein 12

- BC

Breast cancer

- CCDC170

Coiled-Coil Domain Containing 170

- DCIS

Ductal carcinomas in situ

- DFS

Disease- free survival

- ER

Estrogen receptor

- ERBB2

Erb-B2 Receptor Tyrosine Kinase 2

- ESR1

Estrogen receptor alpha

- ET

Endocrine therapy

- HPRT1

Hypoxanthine Phosphoribosyltransferase 1

- HR

Hazard ratio

- IHC

Immunohistochemical staining

- LBD

Ligand-binding domain

- LNN

Lymph node negative

- LNP

Lymph node positive

- OS

Overall survival

- PFS

Progression free survival

- PR

Progesterone receptor

- RT-qPCR

Reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR

- TAM

Tamoxifen

Authors’ contributions

SRV and AMS designed the study; SRV, KR-R, CB, AMT, RF, AMT-J and AMS performed the laboratory experiments (RT-qPCR, western blotting analyses and immunohistochemical stainings). AMS and MPHMJ analyzed the data and compiled statistics; JWM and MPHMJ supplied the patient materials (tissues and clinical information); PV, SS and JWM supervised the study and provided the financial budget; SRV, AMS and MPHMJ wrote the manuscript, which was reviewed, edited and approved by all authors.

Funding

AMS and JWM were supported by the Cancer Genomics Netherlands (CGC.nl)/Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO). SRV was supported by an ERC Advanced grant (No 322737).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol of the study was approved by the medical ethics committee of the Erasmus Medical Centre Rotterdam, The Netherlands (MEC 02.953) and was performed in accordance with the Code of Conduct of the Federation of Medical Scientific Societies in The Netherlands (https://www.federa.org/codes-conduct). The use of coded left-over material for scientific purposes does not require informed consent according to Dutch law and the new European general data protection regulation (GDPR).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Anieta M. Sieuwerts is deceased.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pritchard KI. Endocrine therapy: is the first generation of targeted drugs the last? J Intern Med. 2013;274:144–152. doi: 10.1111/joim.12065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riggins RB, Schrecengost RS, Guerrero MS, Bouton AH. Pathways to tamoxifen resistance. Cancer Lett. 2007;256:1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osborne CK, Schiff R. Mechanisms of endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62:233–247. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-070909-182917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schiavon G, Hrebien S, Garcia-Murillas I, Cutts RJ, Pearson A, Tarazona N, Fenwick K, Kozarewa I, Lopez-Knowles E, Ribas R, et al. Analysis of ESR1 mutation in circulating tumor DNA demonstrates evolution during therapy for metastatic breast cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:313ra182. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac7551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pejerrey SM, Dustin D, Kim JA, Gu G, Rechoum Y, Fuqua SAW. The Impact of ESR1 Mutations on the Treatment of Metastatic Breast Cancer. Horm Cancer. 2018;9:215–228. doi: 10.1007/s12672-017-0306-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beije N, Sieuwerts AM, Kraan J, Van NM, Onstenk W, Vitale SR, van der Vlugt-Daane M, Dirix LY, Brouwer A, Hamberg P, et al. Estrogen receptor mutations and splice variants determined in liquid biopsies from metastatic breast cancer patients. Mol Oncol. 2018;12:48–57. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vitale SR, Sieuwerts AM, Beije N, Kraan J, Angus L, Mostert B, Reijm EA, Van NM, van Marion R, Dirix LY, et al. An Optimized Workflow to Evaluate Estrogen Receptor Gene Mutations in Small Amounts of Cell-Free DNA. J Mol Diagn. 2019;21:123–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson DR, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Wu YM, Shankar S, Cao X, Ateeq B, Asangani IA, Iyer M, Maher CA, Grasso CS, et al. Functionally recurrent rearrangements of the MAST kinase and Notch gene families in breast cancer. Nat Med. 2011;17:1646–1651. doi: 10.1038/nm.2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veeraraghavan J, Tan Y, Cao XX, Kim JA, Wang X, Chamness GC, Maiti SN, Cooper LJ, Edwards DP, Contreras A, et al. Recurrent ESR1-CCDC170 rearrangements in an aggressive subset of oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancers. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4577. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giltnane JM, Hutchinson KE, Stricker TP, Formisano L, Young CD, Estrada MV, Nixon MJ, Du L, Sanchez V, Ericsson PG, et al. Genomic profiling of ER(+) breast cancers after short-term estrogen suppression reveals alterations associated with endocrine resistance. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9:eaai7993. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aai7993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li S, Shen D, Shao J, Crowder R, Liu W, Prat A, He X, Liu S, Hoog J, Lu C, et al. Endocrine-therapy-resistant ESR1 variants revealed by genomic characterization of breast-cancer-derived xenografts. Cell Rep. 2013;4:1116–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshihara K, Wang Q, Torres-Garcia W, Zheng S, Vegesna R, Kim H, Verhaak RG. The landscape and therapeutic relevance of cancer-associated transcript fusions. Oncogene. 2015;34:4845–4854. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veeraraghavan J, Ma J, Hu Y, Wang XS. Recurrent and pathological gene fusions in breast cancer: current advances in genomic discovery and clinical implications. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;158:219–232. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-3876-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun Y, Ye C, Guo X, Wen W, Long J, Gao YT, Shu XO, Zheng W, Cai Q. Evaluation of potential regulatory function of breast cancer risk locus at 6q25.1. Carcinogenesis. 2016;37:163–168. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgv170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li L, Lin L, Veeraraghavan J, Hu Y, Wang X, Lee S, Tan Y, Schiff R, Wang XS. Therapeutic role of recurrent ESR1-CCDC170 gene fusions in breast cancer endocrine resistance. Breast Cancer Res. 2020;22:84. doi: 10.1186/s13058-020-01325-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park C, Yoon KA, Kim J, Park IH, Park SJ, Kim MK, Jang W, Cho SY, Park B, Kong SY, Lee ES. Integrative molecular profiling identifies a novel cluster of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer in very young women. Cancer Sci. 2019;110:1760–1770. doi: 10.1111/cas.13982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lei JT, Gou X, Seker S, Ellis MJ. ESR1 alterations and metastasis in estrogen receptor positive breast cancer. J Cancer Metastasis Treat. 2019;5:38. doi: 10.20517/2394-4722.2019.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanke Y, Shimomura A, Saito M, Honda T, Shiraishi K, Shimada Y, Watanabe R, Yoshida H, Yoshida M, Shimizu C, et al. Gene aberration profile of tumors of adolescent and young adult females. Oncotarget. 2018;9:6228–6237. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simons Y, Hassan M, Chlipala G, Danciu OC, Gadi VK, Singh M, Mohapatra G, Hoskins K. Molecular characterization of luminal breast tumors in African American women. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:550–550. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sieuwerts AM, Meijer-van Gelder ME, Timmermans M, Trapman AM, Garcia RR, Arnold M, Goedheer AJ, Portengen H, Klijn JG, Foekens JA. How ADAM-9 and ADAM-11 differentially from estrogen receptor predict response to tamoxifen treatment in patients with recurrent breast cancer: a retrospective study. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:7311–7321. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sieuwerts AM, Usher PA, Meijer-van Gelder ME, Timmermans M, Martens JW, Brunner N, Klijn JG, Offenberg H, Foekens JA. Concentrations of TIMP1 mRNA splice variants and TIMP-1 protein are differentially associated with prognosis in primary breast cancer. Clin Chem. 2007;53:1280–1288. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.082800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramirez-Ardila DE, Helmijr JC, Look MP, Lurkin I, Ruigrok-Ritstier K, van Laere S, Dirix L, Sweep FC, Span PN, Linn SC, et al. Hotspot mutations in PIK3CA associate with first-line treatment outcome for aromatase inhibitors but not for tamoxifen. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;139:39–49. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2529-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayward JL, Rubens RD, Carbone PP, Heuson JC, Kumaoka S, Segaloff A. Assessment of response to therapy in advanced breast cancer. A project of the programme on clinical oncology of the International Union against Cancer, Geneva, Switzerland. Eur J Cancer. 1978;14:1291–1292. doi: 10.1016/0014-2964(78)90238-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Onstenk W, Sieuwerts AM, Kraan J, Van M, Nieuweboer AJ, Mathijssen RH, Hamberg P, Meulenbeld HJ, De Laere B, Dirix LY, et al. Efficacy of Cabazitaxel in Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer Is Independent of the Presence of AR-V7 in Circulating Tumor Cells. Eur Urol. 2015;68:939–945. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sieuwerts AM, Kraan J, Bolt-de Vries J, van der Spoel P, Mostert B, Martens JW, Gratama JW, Sleijfer S, Foekens JA. Molecular characterization of circulating tumor cells in large quantities of contaminating leukocytes by a multiplex real-time PCR. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;118:455–468. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0290-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sieuwerts AM, Mostert B, Bolt-de Vries J, Peeters D, de Jongh FE, Stouthard JM, Dirix LY, van Dam PA, Van Galen A, de Weerd V, et al. mRNA and microRNA expression profiles in circulating tumor cells and primary tumors of metastatic breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:3600–3618. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lei JT, Gou X, Ellis MJ. ESR1 fusions drive endocrine therapy resistance and metastasis in breast cancer. Mol Cell Oncol. 2018;5:e1526005. doi: 10.1080/23723556.2018.1526005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paratala BS, Dolfi SC, Khiabanian H, Rodriguez-Rodriguez L, Ganesan S, Hirshfield KM. Emerging Role of Genomic Rearrangements in Breast Cancer: Applying Knowledge from Other Cancers. Biomark Cancer. 2016;8:1–14. doi: 10.4137/BIC.S34417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones DT, Kocialkowski S, Liu L, Pearson DM, Backlund LM, Ichimura K, Collins VP. Tandem duplication producing a novel oncogenic BRAF fusion gene defines the majority of pilocytic astrocytomas. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8673–8677. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipson D, Capelletti M, Yelensky R, Otto G, Parker A, Jarosz M, Curran JA, Balasubramanian S, Bloom T, Brennan KW, et al. Identification of new ALK and RET gene fusions from colorectal and lung cancer biopsies. Nat Med. 2012;18:382–384. doi: 10.1038/nm.2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim RN, Moon HG, Han W, Noh DY. Perspective Insight into Future Potential Fusion Gene Transcript Biomarker Candidates in Breast Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:502. doi: 10.3390/ijms19020502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Viale G, Regan MM, Maiorano E, Mastropasqua MG, Dell'Orto P, Rasmussen BB, Raffoul J, Neven P, Orosz Z, Braye S, et al. Prognostic and predictive value of centrally reviewed expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors in a randomized trial comparing letrozole and tamoxifen adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal early breast cancer: BIG 1–98. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3846–3852. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.9453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hede K. Breast cancer testing scandal shines spotlight on black box of clinical laboratory testing. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(836–837):844. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fakhri GB, Akel RS, Khalil MK, Mukherji DA, Boulos FI, Tfayli AH. Concordance between Immunohistochemistry and Microarray Gene Expression Profiling for Estrogen Receptor, Progesterone Receptor, and HER2 Receptor Statuses in Breast Cancer Patients in Lebanon. Int J Breast Cancer. 2018;2018:8530318. doi: 10.1155/2018/8530318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roodi N, Bailey LR, Kao WY, Verrier CS, Yee CJ, Dupont WD, Parl FF. Estrogen receptor gene analysis in estrogen receptor-positive and receptor-negative primary breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:446–451. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.6.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brinkman JA, El-Ashry D. ER re-expression and re-sensitization to endocrine therapies in ER-negative breast cancers. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2009;14:67–78. doi: 10.1007/s10911-009-9113-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Babiceanu M, Qin F, Xie Z, Jia Y, Lopez K, Janus N, Facemire L, Kumar S, Pang Y, Qi Y, et al. Recurrent chimeric fusion RNAs in non-cancer tissues and cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:2859–2872. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martelli MP, Sozzi G, Hernandez L, Pettirossi V, Navarro A, Conte D, Gasparini P, Perrone F, Modena P, Pastorino U, et al. EML4-ALK rearrangement in non-small cell lung cancer and non-tumor lung tissues. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:661–670. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maes B, Vanhentenrijk V, Wlodarska I, Cools J, Peeters B, Marynen P, de Wolf-Peeters C. The NPM-ALK and the ATIC-ALK fusion genes can be detected in non-neoplastic cells. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:2185–2193. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64690-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li H, Wang J, Mor G, Sklar J. A neoplastic gene fusion mimics trans-splicing of RNAs in normal human cells. Science. 2008;321:1357–1361. doi: 10.1126/science.1156725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biernaux C, Loos M, Sels A, Huez G, Stryckmans P. Detection of major bcr-abl gene expression at a very low level in blood cells of some healthy individuals. Blood. 1995;86:3118–3122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Li JV, Yiheng H, Wang X, Tan Y, Schiff R, Wang X. Abstract 376: Therapeutic role of ESR1-CCDC170 gene fusion in breast cancer endocrine resistance. American Association for Cancer Research. 2019;79:376. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Varley KE, Gertz J, Roberts BS, Davis NS, Bowling KM, Kirby MK, Nesmith AS, Oliver PG, Grizzle WE, Forero A, et al. Recurrent read-through fusion transcripts in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;146:287–297. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3019-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Assays used for ESR1-CCDC170 fusion analyses. F: forward primer; R: reverse primer

Additional file 2. Expected ESR1-CCDC170 fusion products. In blue are shown the expected sizes of fusion products while in violet are depicted aspecific products, which can be generated during RT-qPCR

Additional file 3. Expression of CCDC170 wildtype and fusion protein evaluated by immunohistochemical staining (IHC) and western blotting in breast cancer cell lines. A. IHC performed on a cell line microarray of 44 breast cancer cell lines show a histoscore correlation between the cytoplasmic CCDC170 and CCDC170 wildtype as well as between ESR1-CCDC170 exon 8 fusion transcript levels and CCDC170 wildtype, but not with exon 2 fusion transcript levels. B. Western blotting analyses demonstrated the expression of CCDC170 fusion protein. The exon 2 ESR1 – exon 8 CCDC170 fusion product (~30kD) was detected in ZR75.1 and HCC1500, but not in MCF-7. The exon 2- exon 10 CCDC170 fusion protein (~14kD) was also observed, but only in HCC1500

Additional file 4. ESR1-CCDC170 fusions confirmation by MultiNA in a subset of Breast cancer cell lines. If the Taqman probe-based RT-qPCR generated a positive Cq value, the expected fusion gene product sizes were validated by MultiNA. Only products with a MultiNA fusion product of the expected size and a ∆Cq ≥ -25 relative to the two reference genes were considered positive for the fusion product. MultiNA analyses confirmed the CCDC170 RNA fusion products in three breast cancer cell lines. Red boxes indicate fusion expression with correct fragment sizes

Additional file 5. Expression of ESR1 fusions and reference (ESR1 and CCDC170) genes in a panel of 54 breast cancer cell lines. Genes with expression level above the threshold are indicated in orange

Additional file 6. Details of prevalence of ESR1-CCDC170 (exon 1-11) fusion genes in the different analyzed cohorts. ESR1: Estrogen Receptor 1 gene; AI: Aromatase Inhibitor; LNP: Lymph node positive; LNN: Lymph node negative; DCIS: ductal carcinomas in situ

Additional file 7. ESR1 and CCDC170 wildtype expression in ER-positive tumors compared between CCDC170 fusion-negative and positive cases. A. Correlation between CCDC170 and ESR1 wildtype expression measured by RT-qPCR. B. CCDC170 and ESR1 wildtype mRNA levels were measured by RT-qPCR in samples with ESR1-CCDC170 fusion transcript and compared to the group without fusion transcript. The box plots show interquartile ranges (IQR) together with the median (black horizontal line) of the ESR1 and CCDC170 mRNA levels for the different conditions. Group 0: CCDC170-fusion negative cases (n =387); Group 1: CCDC170-fusion positive cases (n =159)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.