Abstract

Background and objectives

The underlying mechanism of IgA vasculitis (IgAV) and IgA vasculitis with nephritis (IgAVN) remains unclear. Therefore, there are no accurate diagnostic methods. Lipid metabolism is related to many immune related diseases, so this study set out to explore the relationship of lipids and IgAV and IgAVN.

Methods

Fifty-eighth patients with IgAV and 28 healthy controls were recruited, which were divided into six separate pools to investigate the alterations of serum lipids according to the clinical characteristics: healthy controls group (HCs) and IgAV group (IgAVs), IgAVN group (IgAV-N) and IgAV without nephritis group (IgAV-C), initial IgAV group (IgAV0) and IgAV in treatment with glucocorticoids group (IgAV1).

Results

31 identified lipid ions significantly changed in IgAVs with p < 0.05, variable importance of the projection (VIP) > 1 and fold change (FC) > 1.5. All these 31 lipid ions belong to 6 classes: triacylglycerols (TG), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylserine, ceramide, and lysophosphatidylcholine. TG (16:0/18:1/22:6) +NH4 over 888875609.05, PC (32:1) +H over 905307459.90 and PE (21:4)-H less than 32236196.59 increased the risk of IgAV significantly (OR>1). PC (38:6) +H was significantly decreased (p < 0.05, VIP>1 and FC>1.5) in IgAVN. PC (38:6) less than 4469726623 conferred greater risks of IgAV (OR=45.833, 95%CI: 6.689~341.070).

Conclusion

We suggest that lipid metabolism may affect the pathogenesis of IgAV via cardiovascular disease, insulin resistance, cell apoptosis, and inflammation. The increase of TG(16:0/18:1/22:6) + NH4, and PC(32:1) + H as well as PE (21:4)-H allow a good prediction of IgAV. PE-to-PC conversion may participate in the damage of kidney in IgAV. PC (38:6) + H may be a potential biomarker for IgAVN.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13000-021-01185-1.

Keywords: IgA vasculitis, IgA vasculitis with nephritis, Lipid metabolism, Serum lipidome

Introduction

IgA vasculitis (IgAV), also referred to as Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP), is the most common systemic vasculitis in children with an annual incidence of 3 ~ 26.7 cases per 100,000 [1]. IgAV is an autoimmune disease characterized by IgA depositing on arterioles, capillaries, and venules. Skin, gastrointestinal tract, joints and kidneys are the main involved organs [2]. As a result, purpura, arthralgia, and abdominal are the “classic triad” of IgAV. IgAV was first reported by Heberden in 1802, however, the cause of it still remains unclear during the past two hundred years [3, 4]. At present, most researchers believe IgAV is related to the high level of IgA1-AECA, which binds to small vessels to induce cytokines that recruit neutrophils activated by the interaction between IgA1 and its receptor FcαRI, resulting in inflammation [3]. Nevertheless, there is no specific diagnostic laboratory test available as markers of IgAV up to date [7, 8]. When severe symptoms occur, glucocorticoids are the main choice for IgAV. IgA vasculitis with nephritis (IgAVN) is an important factor in the poor prognosis of IgAV and about 30% of IgAV patients suffer from nephritis9. Most methods for diagnosis and treatment of IgAVN are based on studies of IgA nephropathy, which is also closely related with galactose-deficient IgA1 [10, 11]. So, the mechanism of IgAV and IgAVN required further investigation to define potential biomarkers to assist in the early detection and accurate diagnosis for improving the prognosis of IgAV.

Lipidomics, a sub-discipline of metabolomics, has become a hot spot in scientific research. Lipids play significant roles in human health as important components of biological membranes, the major source of energy, signaling molecules, and second messengers [12]. The Lipid Metabolites and Pathways Strategy Consortium (LIPID MAPS) has classified lipids into eight categories: fatty acyls (FA), glycerolipids (GL), glycerophospholipids (GP), sphingolipids (SP), sterol lipids (ST), prenol lipids (PR), saccharolipids (SL), and polyketides (PK) [13]. Fatty acid is one of the most common lipid class and it can be divided to saturated fatty acids (e.g. palmitic acid), monounsaturated fatty acids (e.g. oleic acid) and polyunsaturated fatty acids (e.g. docosahexaenoic acid or linoleic acid), according to chain length and degree of saturation. Among these, saturated fatty acids were reported to be related with inflammation with insulin-resistant states and atherosclerosis, whereas oleic acid and polyunsaturated omega-3 fatty acids are anti-inflammatory and protective against these metabolic diseases [14]. GL are esterified by glycerol and fatty acids, according to the number of which, GL can be classified to be monoacylglycerols (MG), diacylglycerols (DG) and triacylglycerols (TG). Higher levels of DG and TG increase the risk of type 2 diabetes [15]. GP consist of DG and ether glycerophospholipids. With respect to the different phosphate groups, GP were categorized into different lipid classes, such as phosphatidylglycerol (PG), phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE). SP were associated with obesity, insulin resistance, muscle function, β-cell exhaustion, the inflammatory response, vascular complications, and cardiac failure [16–19]. Ceramide (Cer) and sphingomyelin were the most common SP. ST included sterols, steroids, secosteroids, bile acids with derivatives, steroid conjugates and so on. Cholesterol, a kind of sterols, is an important component of the cellular membrane in animals. Vitamin E, Vitamin K and Coenzyme Q10 were well known PR. SL were fatty acids with the sugar moiety. Many polyketides are clinically important, with antimicrobial, anticancer and immunosuppressive properties [20, 21].

Lipidomics has been established to play an important role in many diseases, such as IgA nephropathy, systemic lupus erythematosus, major depressive disorder, type 2 diabetes [15, 22–25]. In IgAV, paraoxonase1 (PON1), a high density lipoprotein (HDL)-associated enzyme preventing lipid peroxidation was confirmed to be associate with the development and progression of arterial damage. Meanwhile, the differentially expressed proteins in IgAVN were reported to be enriched in lipid metabolism [26].

In this study, we sought to discover the serum lipid alternations in IgAV and IgAVN children by using Liquid Chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LCMS/MS) [27], trying to find some biomarkers in IgAV and IgAVN disease.

Methods

Ethical statement

A total of 86 individuals under 18 years old participated in our research, and informed consent was signed by their guardians. The experimental protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (XXJ2018–11).

Participants and grouping

A total of 86 individuals under 18 years old participated in our research, and informed consent was signed by their guardians. All participants were recruited from The Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University between November 2018 and May 2019(Hunan Changsha, China). 58 IgAV patients were diagnosed based on EULAR/PRINTO/PRES 2008 criteria for Henoch-Schonlein purpura: Purpura or petechiae (mandatory) with lower limb predominance [7]. The healthy control group (HCs group) consisted of 28 healthy children without any disease or drug-using histories in recent 6 months, confirming by screening questionnaires. All the participants with previous chronic inflammatory diseases, chronic kidney disease, other systemic vasculitis or immunological diseases were excluded.

In IgAVs groups, according to the renal damage and glucocorticoids treatment, they were divided into four groups. The diagnosis of IgAV with nephritis (IgAV-N group) was made when patients had biopsy specimen–proven renal involvement with mesangial IgA in electron microscopy. IgAV patients without nephritis (IgAV-C group) were consistent with IgAV patients without proteinuria and hematuria on urinalysis. Initial IgAV patients (IgAV0 group) means those in the early onset did not receive any treatments, and IgAV1 groups were defined as IgAV patients with glucocorticoids treatment with or without other treatment measures.

Sample collection and preparation

Blood samples were collected from vein in the morning after an overnight fasting (> 8 h). The quality control (QC) sample was prepared from 10 μL of each test sample. The fasting blood was collected in 5 mL vacutainer tubes containing heparin lithium, then the samples were centrifuged for 15 min (1500×g, 4 °C). Each aliquot (100 μL) of the plasma sample was stored at − 80 °C until the ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography equipped with Liquid Chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis. The plasma samples were thawed at 4 °C and 100 μL aliquots were mixed with 200 μL water and then added to 240 μL of cold methanol/acetonitrile, again mixed well. After that, 800 μL MTBE were added and it was mixed well. The homogenate solution was followed by sonication in water for about 20 min and placed at room temperature for another 30 min. After centrifugation for 15 min (1400×g, 10 °C), the upper organic phase was collected and dried with nitrogen gas (Changsha Ruichong Gas Co., LTD). Before LC-MS/MS, each sample was added to 200 μL isopropanol:acetonitrile (90:10, v/v), vortexed and centrifuged for 15 min (1400×g, 10 °C) and the supernatant was instantaneously injected into the chromatograph.

LC-MS/MS analysis

These samples were performed on an ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) Nexera LC-30A (Agilent Technologies, Santa-Clara, California, USA). The injection volume was 3 μl, flow rate was 300 ml/ min and the column temperature was 45 °C. The mobile phase comprised of A, 10 mM ammonium formate acetonitrile solution (acetonitrile:water = 6:4, v/v) and B, 10 mM ammonium formate acetonitrile isopropyl alcohol solution (acetonitrile:isopropanol = 1:9, v/v). The program of gradient elution included 30% (B) at 0–2 min, a linear gradient from 30 to 100% (B) at 2-25 min, and 30% (B) at 25-35 min. During the analysis process, we used an automatic sample injector (10 °C) and continuous sample analysis using random order was performed to correct the impact of instrument signal fluctuation.

After the UHPLC separation, mass spectrometry was performed using a Q-Exactive plus mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific™).

Electrospray ionization (ESI) positive ion and negative ion modes were used respectively, under the following condition:

Positive: Heater Temp 300 °C, Sheath Gas Flow rate 45 arb, Aux Gas Flow Rate15 arb, Sweep Gas Flow Rate 1arb, spray voltage 3.0KV, Capillary Temp 350 °C, S-Lens RF Level 50%. MS1 scan ranges: 200–1800.

Negative: Heater Temp 300 °C, Sheath Gas Flow rate 45arb, Aux Gas Flow Rate 15arb, Sweep Gas Flow Rate 1arb, spray voltage 2.5KV, Capillary Temp 350 °C, S-Lens RF Level 60%. MS1 scan ranges: 250–1800

According to the methods used which were each fully scanned (full scan), 10 pieces of map (MS2 scan, HCD) were collected, and the lipid molecules and quality of the lipid debris charge ratio were collected.

The resolution of MS2 at M/Z200 was 17,500 AND The resolution of MS2 at M/Z200 was 17,500,

Lipidomics data analysis

LipidSearch software version 4.1 (Thermo Scientific™) was used for data processing, such as peak identification, lipid identification, peak extraction, peak integration, and peak alignment. Lipid molecules with a RSD > 30% were removed.

The missing value in the group with > 50% of lipid molecules was also deleted and the abundance values were obtained using total peak area normalization based on LipidSearch data extraction. The application software SIMCA-P 14.1 (Umetrics, Umea, Sweden) was used for pattern recognition. p value< 0.05 and VIP > 1 was considered statistically significant. Fold change (FC) > 1.5 was considered large differences.

Statistical analysis

In order to access the relationship among changed lipidions and the severity of IgAV or IgAVN, optimal curve correlation of lipidions and multiple regression analysis of all the changed lipidions and IgAV or IgAVN were performed using SPSS (26.0). A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The clinical and demographic characteristics of all the subjects

Twenty-eight healthy controls (HCs) (male/female: 14/14) and 58 IgAV patients (IgAVs) (male/female: 28/30) were included in this research. There were no significant differences in sex and age between the two groups. Body mass index (BMI) of IgAV patients were statistically higher (p = 0.01). In these 58 IgAV children, 15 (25.86%) children were initially diagnosed without any treatments (IgAV0), 30 (51.72%) were in treatment with glucocorticoids (IgAV1), and 13 patients had stopped medication after drug treatment (22.41%), purpura (48.28%), arthralgia (20.69%), and abdominal symptoms (20.69%) were the main clinical features of these patients. 13 (22.41%) IgAVs were diagnosed with IgAVN (IgAV-N) from electron microscopy (patients detected only by light microscopy were excluded). 28 (48.28%) IgAVs were defined as IgAV without nephritis (IgAV-C) by the absence of proteinuria and hematuria on urinalysis. The clinical and demographic characteristics of the subjects are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The clinical and demographic characteristics of all the subjects

| Characteristics of different groups | IgAVs | HCs | IgAV-N | IgAV-C | IgAV0 | IgAV1 | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgAVs vs HCs | IgAV-N vs IgAV-C | IgAV0 vs IgAV1 | |||||||

| Patients (n) | 58 | 28 | 13 | 28 | 15 | 30 | NA | NA | NA |

| Male (n, %) a | 28 (48.3%) | 14 (50.0%) | 7 (50.0%) | 16 (53.6%) | 7 (46.7%) | 16 (53.3%) | 0.881 | 0.82 | 0.881 |

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| 2~14 | 3~17 | 4~14 | 7~14 | 2~14 | 4~14 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Mean ± SD b | 9.17 ± 3.08 | 10.61 ± 3.67 | 10.23 ± 2.52 | 8.50 ± 2.90 | 8.27 ± 3.67 | 9.80 ± 2.76 | 0.061 | 0.072 | 0.12 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||||||

| Mean ± SD b | 16.47 ± 2.85 | 18.57 ± 4.51 | 17.14 ± 1.32 | 15.88 ± 1.73 | 15.96 ± 2.10 | 16.83 ± 3.46 | 0.01 | 0.153 | 0.38 |

| Symptoms | |||||||||

| Purpura | 28 (48.28%) | 0(0.00%) | 2(15.38%) | 14(50.00%) | 15(100.00%) | 14(46.67%) | NA | NA | NA |

| Arthralgia | 12 (20.69%) | 0(0.00%) | 1(7.69%) | 6(21.43%) | 6(40.00%) | 6(20.00%) | NA | NA | NA |

| Abdominal pain | 12 (20.69) | 0(0.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 8(28.57%) | 6(40.00%) | 6(20.00%) | NA | NA | NA |

| Renal biopsy | 13 (22.41%) | 0(0.00%) | 13(100.00%) | 0(0.00%) | 1(6.67%) | 14(46.67%) | NA | NA | NA |

| Haematuria | 21 (36.21%) | 0(0.00%) | 2(15.38%) | 0(0.00%) | 2(13.33%) | 6(20.00%) | NA | NA | NA |

| Proteinuria | 13 (22.41%) | 0(0.00%) | 8(61.84%) | 0(0.00%) | 2(13.33%) | 13(43.33%) | NA | NA | NA |

aAnalyzed by the Chi-square test

bAnalyzed by the ANOVA followed by post hoc comparison of the groups using the Bonferroni test

NA means it cannot be calculated

Lipidomics analysis of plasma obtained from IgAV subjects and HCs

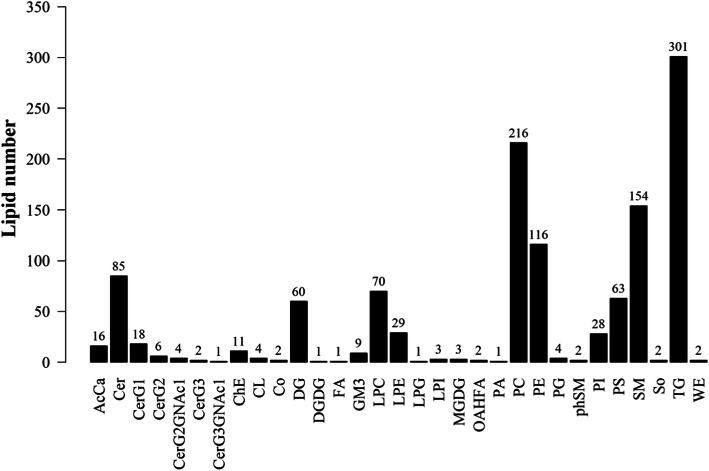

The data obtained from negative and positive ion modes on the UHPLC-Orbitrap MS were analyzed to qualitatively identify then perform quantification. A total of 31 classes and 1217 species of lipids (including homomers) were analyzed using the Lipid Search software version 4.1. Among these 31 lipid classes, classes possessing the highest number of lipid species were TG (301), PC (216), SM (154) and PE (116) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

all the lipids detected in plasma samples in HCs and IgAVs. All the 1217 species of lipids detected belonged to 31 classes, of which TG (301), PC (216), SM (154) and PE (116) were the predominant lipid

In order to identify the differences of lipid classes in IgAVs, Wilcoxon test was performed and a single lipid class, GM3, was significantly associated (p = 0.000454) with IgAV. However, the expression changes of all these significant lipid classes (p < 0.05) were not obvious (FC < 1.5). To validate the reproducibility of the results, comparison was made among the basic peak chromatogram (BPC) of QC samples from both negative and positive ion modes (Fig. S1). The results showed an overlap between response strength and retention time of the chromatographic peak; the experimental repeatability was also deemed good. To look for differences of lipidions between IgAVs and HCs, OPLS-DA score plot and permutation test results were displayed (Fig. S2). There were significant differences between these two groups. We performed a preliminary screen for differences under multivariate statistical analyses (VIP > 1) based on the OPLS-DA model, and we also identified the significance under univariate statistical analyses (P < 0.05). Finally, we screened 31 lipidions with multiple change greater than 1.5.

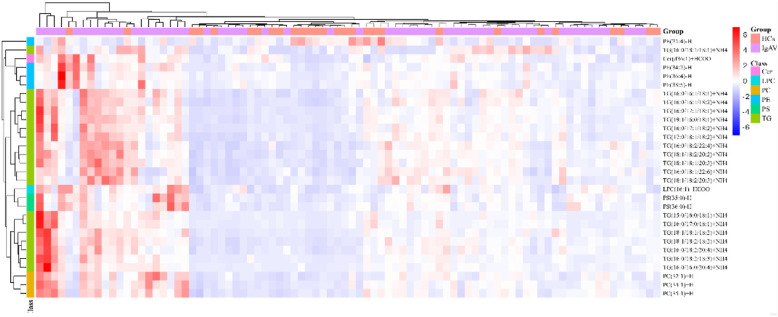

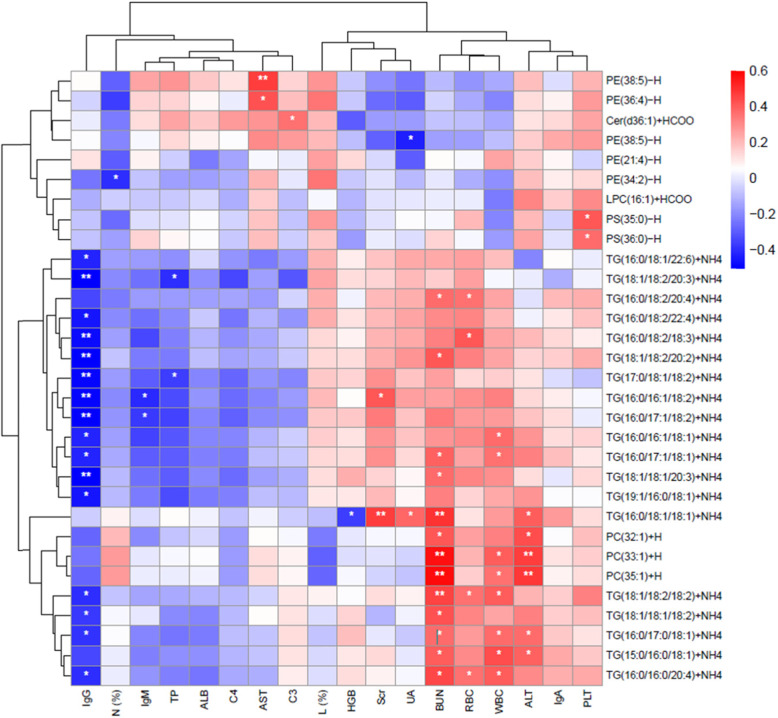

Thirty One identified lipidions showed significant difference between HCs and IgAVs, and the detailed information of them is provided in Table 2. The heat plot for these differential lipids is shown in Fig. 2. As it can be seen in the heat plot, the plasma lipid levels of IgAV patients are increased over all. All these 31 lipid ions can be divided into 6 classes, including TG, PE, PC, Phosphatidylserine (PS), Cer, and lyso-phosphatidylcholine (LPC). Most of these lipidions are TGs. The correlation between 31 lipid ions and laboratary examinations were showed in Fig. 3.

Table 2.

Identified differential lipidions between HCs and IgAVs

| Lipidions | Class | Fatty Acid | VIP | p value | Fold.change | Log1.5 foldchange |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TG(16:0/18:2/18:3) + NH4 | TG | (16:0/18:2/18:3) | 1.84835 | 0.02482772 | 2.103717 | 1.834204 |

| TG(15:0/16:0/18:1) + NH4 | TG | (15:0/16:0/18:1) | 1.37775 | 0.04404364 | 1.923537 | 1.613371 |

| TG(16:0/16:0/20:4) + NH4 | TG | (16:0/16:0/20:4) | 1.72933 | 0.00999953 | 1.909782 | 1.595671 |

| TG(16:0/17:1/18:2) + NH4 | TG | (16:0/17:1/18:2) | 1.62306 | 0.00722187 | 1.80384 | 1.454916 |

| PC(32:1) + H | PC | (32:1) | 2.56503 | 0.00066097 | 1.796607 | 1.445007 |

| PS(35:0)-H | PS | (35:0) | 3.2507 | 0.00036811 | 1.780378 | 1.422627 |

| TG(16:0/17:1/18:1) + NH4 | TG | (16:0/17:1/18:1) | 2.23389 | 0.00898277 | 1.768255 | 1.405776 |

| TG(18:1/18:2/18:2) + NH4 | TG | (18:1/18:2/18:2) | 3.78748 | 0.00043832 | 1.757964 | 1.391381 |

| TG(16:0/18:2/20:4) + NH4 | TG | (16:0/18:2/20:4) | 2.6048 | 0.00040886 | 1.748873 | 1.378594 |

| PC(33:1) + H | PC | (33:1) | 1.25795 | 0.0002234 | 1.7368 | 1.361509 |

| TG(16:0/17:0/18:1) + NH4 | TG | (16:0/17:0/18:1) | 1.32552 | 0.02861302 | 1.736614 | 1.361245 |

| TG(18:1/18:1/18:2) + NH4 | TG | (18:1/18:1/18:2) | 1.19282 | 0.00397713 | 1.713335 | 1.327961 |

| PS(36:0)-H | PS | (18:0/18:0) | 1.54875 | 0.00017949 | 1.668692 | 1.262846 |

| Cer(d36:1) + HCOO | Cer | (d18:1/18:0) | 1.36673 | 0.00092262 | 1.654524 | 1.241817 |

| TG(16:0/16:1/18:1) + NH4 | TG | (16:0/16:1/18:1) | 5.6857 | 0.01808469 | 1.620904 | 1.191185 |

| TG(18:1/18:2/20:2) + NH4 | TG | (18:1/18:2/20:2) | 1.9634 | 9.50E-05 | 1.616611 | 1.184644 |

| TG(16:0/18:1/18:1) + NH4 | TG | (16:0/18:1/18:1) | 1.60668 | 0.02201249 | 1.592181 | 1.14709 |

| TG(18:1/18:1/20:3) + NH4 | TG | (18:1/18:1/20:3) | 1.8557 | 0.00061773 | 1.583948 | 1.134303 |

| TG(19:1/16:0/18:1) + NH4 | TG | (19:1/16:0/18:1) | 1.50919 | 0.01516599 | 1.577544 | 1.124312 |

| TG(16:0/18:1/22:6) + NH4 | TG | (16:0/18:1/22:6) | 1.88274 | 0.00046975 | 1.557257 | 1.09239 |

| PE(36:4)-H | PE | (16:0/20:4) | 1.77295 | 0.00246647 | 1.55075 | 1.082063 |

| TG(16:0/16:1/18:2) + NH4 | TG | (16:0/16:1/18:2) | 4.49804 | 0.01947916 | 1.547024 | 1.07613 |

| PE(38:5)-H | PE | (18:0/20:5) | 1.02753 | 0.01636181 | 1.541867 | 1.067895 |

| PC(35:1) + H | PC | (35:1) | 1.177 | 0.00014923 | 1.529081 | 1.047357 |

| TG(17:0/18:1/18:2) + NH4 | TG | (17:0/18:1/18:2) | 1.41525 | 0.01595431 | 1.509847 | 1.016138 |

| LPC(16:1) + HCOO | LPC | (16:1) | 1.37718 | 3.72E-05 | 1.508243 | 1.013516 |

| PE(38:5)-H | PE | (18:1/20:4) | 1.09762 | 0.01334339 | 1.506316 | 1.010363 |

| TG(16:0/18:2/22:4) + NH4 | TG | (16:0/18:2/22:4) | 3.00908 | 0.00181107 | 1.505923 | 1.009719 |

| PE(34:2)-H | PE | (16:0/18:2) | 1.60924 | 0.01677844 | 1.505824 | 1.009557 |

| TG(18:1/18:2/20:3) + NH4 | TG | (18:1/18:2/20:3) | 1.01849 | 0.00323496 | 1.505755 | 1.009444 |

| PE(21:4)-H | PE | (10:0/11:4) | 1.41852 | 0.03854884 | 0.601425 | −1.254 |

Fig. 2.

The heat plot for the differential lipids in IgAVs vs HCs. Decreased lipidions colored blue and increased lipidions colored red. All Most of these altered lipidions rose in IgAV patients, except for PE (21:4)-H

Fig. 3.

The heat plot for the 31 lipid ions and other lab examinations. Negative correlation colored blue and positive correlation colored red. * means p < 0.05, and ** means p < 0.01

To further evaluate the lipid biomarkers of IgAV, a stepwise binary logisticregression analysis regressed all these 31 lipid ions and BMI and showed the model of TG (16:0/18:1/22:6) +NH4, PC (32:1) +H, BMI, and PE (21:4)-H was significant with the correct class of 83.7%. A decreased BMI was linked with an increased risk of IgAV (OR=0.68, 95%CI: 0.53~0.88). Among these three lipid ions, PE (21:4)-H were decreased (FC<1) in IgAVs. ROC analysis was performed and corresponding AUC was calculated to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of each of the 3 plasma lipid ions and BMI for diagnosing IgAV (Fig. 4). TG (16:0/18:1/22:6) +NH4, and PC (32:1) +H were significantly increased, with AUC greater than 0.7, distinguishing IgAV patients from HCs. Then we determined cut-points for TG (16:0/18:1/22:6) +NH4 (888875609.05), PC (32:1) +H (905307459.90), BMI (19.18), and PE (21:4)-H (32236196.59) (Table 3). Children with the quantity of TG(16:0/18:1/22:6)+NH4 over 888875609.05 were 4.974 times more likely with IgAV (OR=4.974, 95%CI: 1.027~24.092); Children with the quantity of PC(32:1)+H over 905307459.90 were 9.804 times more likely with IgAV (OR=9.804, 95%CI: 1.964~48.942); children with the quantity of PE(21:4)-H less than 32236196.59 were 6.897 times more likely with IgAV (OR=6.897,95%CI: 1.920~24.774); children with BMI less than 19.18 were 5.629 times more likely with IgAV (OR=5.629, 95%CI: 1.4445~21.937).

Fig. 4.

The ROC Curve of 2 increased lipidions(a), 1 decreased lipidions(b) and BMI(c) for IgAV

Table 3.

TG(16:0/18:1/22:6) + NH4, PC(32:1) + H, PE (21:4)-H, and BMI as predictors of IgAV

| Parameter | B | Std. Error | Wald Chi-Square | p Value | Odds Ratio | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| TG(16:0/18:1/22:6) + NH4 | 1.604 | 0.805 | 3.971 | 0.046 | 4.974 | 1.027 | 24.092 |

| PC(32:1) + H | 2.283 | 0.820 | 7.744 | 0.005 | 9.804 | 1.964 | 48.942 |

| PE(21:4)-H | 1.931 | 0.652 | 8.761 | 0.003 | 6.897 | 1.920 | 24.774 |

| BMI | 1.728 | 0.694 | 6.199 | 0.0132 | 5.629 | 1.4445 | 21.937 |

Lipidomics analysis of plasma obtained from IgAV-N subjects and IgAV-C

Seven kinds of lipidions were found to be significantly different (p<0.05, VIP>1, FC>1.5) (Table 4), and a heatmap was performed in Fig. 5. PC (38:6) +H, was significantly different (p<0.01) with correct class of 85.4% (Table S3). PC (38:6) +H was decreased in IgAVN patients with an AUC of 0.885 to discriminate IgAV-N from IgAV-C (Fig. 6). We identified the cut-point of PC (38:6) (4469726623) for IgAVN on the basis of the results from the ROC curve. Based on the logistic model with PC (38:6), children with the quantity of PC (38:6) less than 4469726623 were 45.833 times more likely with IgAVN (OR=45.833, 95% CI: 6.689~341.070).

Table 4.

Identified differential lipid ions between IgAVc and IgAVN

| LipidIons | Class | Fatty Acid | p value | VIP | Fold change | log1.5 fold change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TG(18:0/16:0/18:3) + NH4 | TG | (18:0/16:0/18:3) | 0.0013 | 2.57394 | 3.28158 | 2.93077 |

| TG(16:1/16:1/18:2) + NH4 | TG | (16:1/16:1/18:2) | 0.014209 | 1.49978 | 2.01381 | 1.726483 |

| PE(34:2p)-H | PE | (34:2p) | 0.016049 | 1.27288 | 1.52816 | 1.045871 |

| PC(38:5) + H | PC | (18:1/20:4) | 0.002901 | 2.87729 | 0.662728 | −1.01461 |

| PC(38:6) + H | PC | (16:0/22:6) | 5.55E-05 | 3.21673 | 0.649622 | −1.06388 |

| PC(18:0/22:5) + H | PC | (18:0/22:5) | 0.008981 | 1.27596 | 0.635838 | − 1.11677 |

| PC(40:6) + H | PC | (40:6) | 0.000125 | 2.6263 | 0.608873 | −1.22365 |

Fig. 5.

The heat plot for the differential lipids in IgAV-N vs IgAV-C. Decreased lipidions colored blue and increased lipidions colored red. PCs were decreased in IgAVN, while PEs and TGs were increased

Fig. 6.

The ROC Curve of PC (38:6) + H for IgAVN

Lipidomics analysis between the plasma of IgAV1 and IgAV0

A lipidions contrast was made between IgAV0 and IgAV1 to evaluate the lipidions changes during the treat phrase with glucocorticoids. 17 lipidions were identified to be significantly different (p < 0.05, VIP>1, FC>1.5) (Table 5). TG (16:0/18:1/22:6) +NH4, TG (16:0/16:1/18:2) +NH4, and TG (16:0/18:2/18:3) +NH4 were significantly different in both IgAV1vs IgAV0 and IgAVs vs HCs (Table 6) and remained elevated after treatment.

Table 5.

Identified differential lipid ions between IgAV0and IgAV1

| LipidIons | Class | Fatty Acid | p value | VIP | Fold change | log1.5 fold change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SM(d18:1/24:1) + H | SM | (d18:1/24:1) | 0.00484 | 5.8611 | 0.734012 | −7.63E-01 |

| TG(18:3/18:2/18:2) + NH4 | TG | (18:3/18:2/18:2) | 0.01953 | 2.73572 | 4.22322 | 3.55E+ 00 |

| TG(16:1/18:2/18:3) + NH4 | TG | (16:1/18:2/18:3) | 0.0158979 | 1.29336 | 3.19441 | 2.86E+ 00 |

| TG(16:1/16:1/18:2) + NH4 | TG | (16:1/16:1/18:2) | 0.007937 | 1.16421 | 2.82852 | 2.56E+ 00 |

| TG(16:0/18:1/22:6) + NH4 | TG | (16:0/18:1/22:6) | 0.0090351 | 1.37791 | 2.71566 | 2.46E+ 00 |

| TG(18:3/18:2/18:2) + Na | TG | (18:3/18:2/18:2) | 0.00191 | 1.06146 | 2.55724 | 2.32E+ 00 |

| TG(18:1/18:2/18:3) + NH4 | TG | (18:1/18:2/18:3) | 0.0076853 | 3.27982 | 2.09544 | 1.82E+ 00 |

| PC(32:2) + H | PC | (14:0/18:2) | 0.0075443 | 1.44772 | 1.99826 | 1.71E+ 00 |

| TG(18:1/18:1/18:3) + NH4 | TG | (18:1/18:1/18:3) | 0.0037147 | 2.4811 | 1.82271 | 1.48E+ 00 |

| PC(36:4) + H | PC | (18:2/18:2) | 0.0265343 | 1.97895 | 1.79346 | 1.44E+ 00 |

| TG(16:0/18:2/18:3) + NH4 | TG | (16:0/18:2/18:3) | 0.0271601 | 1.92436 | 1.75106 | 1.38E+ 00 |

| TG(16:0/16:1/18:2) + NH4 | TG | (16:0/16:1/18:2) | 0.0379257 | 1.65399 | 1.66646 | 1.26E+ 00 |

| TG(16:0/18:1/22:5) + NH4 | TG | (16:0/18:1/22:5) | 0.0135847 | 1.84413 | 1.58691 | 1.14E+ 00 |

| PC(34:2e) + H | PC | (34:2e) | 0.0298178 | 2.96902 | 1.57944 | 1.13E+ 00 |

| LPC(20:5) + H | LPC | (20:5) | 0.0232202 | 1.05066 | 1.51736 | 1.03E+ 00 |

| TG(18:1/18:2/22:5) + NH4 | TG | (18:1/18:2/22:5) | 0.0358588 | 1.93212 | 0.592921 | −1.29E+ 00 |

| SM(d42:1) + H | SM | (d42:1) | 0.0263021 | 1.59175 | 0.468622 | −1.87E+ 00 |

Table 6.

3 lipidions significantly different in both IgAVs vs HCs and IgAV1 vs IgAV0

| Lipidions | Fold Change | |

|---|---|---|

| IgAVs vs HCs | IgAV1 vs IgAV0 | |

| TG(16:0/18:1/22:6) + NH4 | 1.557256907 | 2.71566 |

| TG(16:0/16:1/18:2) + NH4 | 1.54702425 | 1.66646 |

| TG(16:0/18:2/18:3) + NH4 | 2.103717277 | 1.75106 |

Discussion

The current study was carried out to investigate the lipidomic profile for the patients with IgAV in order to established and evaluate them as novel biomarkers.

Among IgAV patients and healthy controls, there were no differences in age or sex, whereas BMI was significantly increased in IgAV patients. GM3 was significantly associated (p = 0.000454) with IgAV, though the FC was small. 31 lipidions were finded to be significantly changed in IgAV patients and all of them are divided into 6 classes, including TG, PE, PC, PS, Cer and LPC. Most of these 31 lipidions were increased in IgAV patients, apart of PE (21:4)-H.

Among IgAVN patients and IgAV patients without nephritis, no difference in basic characteristics was observed. And there are two different change trends of lipidions in IgAVN patients and IgAV patients without nephritis that in IgAVN, PEs and TGs continued growing while PCs declined.

Most of these significant lipidions in IgAV belong to TG which plays an important role in cardiovascular diseases, which are also common seen in IgAVs [28]. High TG concentrations are associated with decreased high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (HDL-C) levels, elevated levels of non–HDL-C and raised remnants rich in cholesterol, that are risks of cardiovascular disease [29, 30]. Also, TG is are correlated with the severity of insulin resistance, which has been showed to have an adverse impact on cardiovascular and renal systems [31]. Moreover, Metabolic pathways of TG are not independent from the effects of the presence of structural lipids such as glycerophospholipids or sphingolipids, which may interact with TG metabolism at multiple levels [32]. PC is one of GPs and it has been reported to prevent TG accumulation and the coalescence of LDs (lipid droplets), which are cellular storage organelles for TG [33]. Meanwhile, LDs can synthesize PC locally with 2 PC synthesizing enzymes, lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 1 and lysop hosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 2, localized on the surface of LDs [34]. Besides, Cer was involved in the process that TG influences the severity of insulin resistance [35–37]. In our research, TG are positive related to BUN and WBC. BUN is generally regarded as a significant serum marker in estimating renal function which is important in IgAV. WBC are involved in immunity which related to the pathogenesis of IgAV [38].

In addition, LPC is called as ‘the grease for cardiovascular disease’, and it can activate platelets as well as form inflammatory platelet-monocyte aggregates interaction with G2AR on platelets [39, 40]. In IgAV children, platelet is in a high level [41]. Platelets not only exacerbate cardiovascular diseases, but also aggravate inflammation. Activated platelets can induce the release of inflammatory cytokines (including TNF-α and IL-6) and the presentation of surface molecules (including P-selectin, E-selectin) to recruit neutrophil and release NETosis [41, 42]. Meanwhile, platelet can release C3 and GM-CSF, which also contribute to IgAV.

Plasmalogen PC and plasmalogen PE were reported to be associated with oxidative stresses which are important in IgAV pathogenesis [43]. In our result PE(36:4)-H, PE (38:5)-H, PE (38:5)-H PE (34:2)-H and PCs rose, while PE (21:4)-H declined. In addition, the diversity of PE and PC species containing polyunsaturated fatty acyls (acids) (PUFAs) contributes to the production of lipid mediators [44, 45]. The decreased PE (21:4)-H may be hydrolyzed to release free arachidonic acid, to release varieties of eicosanoids such as prostaglandins and leukotrienes, causing inflammation and damage of vascular endothelial cells in IgAV. These increased phospholipids may rise to compensate for the reduced PE (21:4)-H, as well as be the reservoir for producing anti-inflammatory mediators such as resolvins and protectins [25].

PS were reported to be associated with mitochondrial function, which plays an important role in cell death such as apoptosis [46]. PS exposed on the cell surface is an apoptotic ‘eat me’ signal which can be recognized by the PS receptor, or a secreted PS-binding molecules, which bind PS on apoptotic cells and a membrane protein on the macrophage [46]. Besides, in our study, PS are found to be related to platelets count.

Cer belong to SP. SP plays an important role in cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and cell senescence [47, 48]. Cer can upregulate cytokine expression and cell apoptosis through inducing the activity of caspase3 and caspase8 [49, 50].

Though the change of GM3 was little, GM3 may be involved in the pathogenesis of IgAV. GM3 was found to inhibit cell growth by decreasing cell adhesion and epidermal growth factor-dependent phosphorylation of epidermal growth factor receptor [51]. GM3 were also report to increase IL-17 proliferation and secretion from Th17 cells so as to accelerate the pathogenesis and progression of RA and mouse CIA [52]. In human B cell, GM3 can inhibit IgG subclasses and IgM production, but not IgA1 and IgA2 [53].

Above all, lipid metabolism can participate in the pathogenesis of IgAV, through cardiovascular disease, insulin resistance, cell apoptosis, and inflammation.

The multiple logistic regression analysis was used to assess associations between lipidions and IgAV. Based on the lipidions quantitated by LC/MS, we constructed ROC curves to select the optimal cut-point for TG(16:0/18:1/22:6) + NH4 (888,875,609.05), PC(32:1) + H (905,307,459.90), and PE (21:4)-H (32,236,196.59). Then, we started multiple logistic regression to prove that the increase in TG(16:0/18:1/22:6) + NH4 and PC(32:1) + H, as well as the decrease of PE (21:4)-H can raise risk of IgAV. Besides, in our study BMI also decreased in IgAVs, that is not normal in cardiovascular diseases [54]. This may because the average BMI of both IgAVs and HCs fallen within the normal BMI range.

Next, we compared IgAV patients with and without nephritis. PCs were decreased in IgAVN while PEs and TGs were increased. In our study, PC (38:6) + H was found to be the most prominent biomarker in IgAVN, with a significant decrease and an AUC of 0.885. As an anti-inflammatory and antioxidant agent, PC ameliorated oxidative stress in kidney via reducing proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 [55]. PC also decreased tubular degeneration and hypertrophy of glomeruli by enhancing antioxidant enzyme activity [56]. Meanwhile, DHA-enriched PC can attenuate nephrotoxicity through inactivating mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways, including upregulation of Bcl-2 and downregulation of caspase-9, caspase-3, cytochrome-c, p38, and JNK. On the contract, PC loss may lead to renal damage. In animals, PC mainly obtained from diet and the methylation of PE by the enzyme PE N-methyltransferase (PEMT) [57]. The increased PE and decreased PC imply that the methylation of PE may be disturbed in IgAVN.

Finally, comparison before treatment and after treatment with glucocorticoids was made. In our research, TG was increased in IgAV and continued to rise after threaten. That could be because of the effects of glucocorticoids [58].

This study reveals the lipid alterations in IgAV and IgAVN. However, the mechanisms of lipid alterations can only be speculated upon at present. Further studies are required to explore the functions of theses lipids in physiological and pathological processes through cell and animal experiments.

Supplementary Information

Abbreviations

- IgAV

IgA vasculitis

- IgAVN

IgA vasculitis nephritis

- FA

Fatty acyls

- GL

Glycerolipids

- GP

Glycerophospholipids

- SP

Sphingolipids

- ST

Sterol lipids

- PR

Prenol lipids

- SL

Saccharolipids

- PK

Polyketides

- MG

Monoacylglycerols

- DG

Diacylglycerols

- TG

Triacylglycerols

- PG

Phosphatidylglycerol

- PC

Phosphatidylcholine

- PE

Phosphatidylethanolamine

- Cer

Ceramide

- PON1

Paraoxonase1

- HDL

High density lipoprotein

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDs

Lipid droplets

- LC-MS/MS

Liquid Chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry

- ESI

Electrospray ionization

- VIP

Variable importance of the projection

- BUN

Blood urea nitrogen

- Scr

Serum creatinine

- UA

Uric acid

- WBC

White blood cell

- RBC

Red blood cell

- HGB

Hemoglobin concentration

- PLT

Platelets count

- N (%)

Neutrophil count

- L (%)

Lymphocyte count

- C3

Complement component 3

- C4

Complement component 4

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- ALB

Albumin

- TP

Total protein

Authors’ contributions

HXJ designed the experiment and provided guidance and support in the whole process. LY and WM collected the data and wrote the manuscript. HQN, DXQ and FSP participated in the specimen collection and technical guide. LTH, DXW and LXY analyzed the data. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ying Liu and Min Wen contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-first authors.

References

- 1.Piram M, Mahr A. Epidemiology of immunoglobulin a vasculitis (Henoch-Schonlein): current state of knowledge. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2013;25(2):171–178. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32835d8e2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ozen S, Marks SD, Brogan P, Groot N, de Graeff N, Avcin T, Bader-Meunier B, Dolezalova P, Feldman BM, Kone-Paut I, Lahdenne P, McCann L, Pilkington C, Ravelli A, van Royen A, Uziel Y, Vastert B, Wulffraat N, Kamphuis S, Beresford MW. European consensus-based recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of immunoglobulin a vasculitis-the SHARE initiative. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2019;58(9):1607–1616. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heineke MH, Ballering AV, Jamin A, Ben Mkaddem S, Monteiro RC, Van Egmond M. New insights in the pathogenesis of immunoglobulin a vasculitis (Henoch-Schonlein purpura) Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16(12):1246–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2017.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonzalez-Gay MA, Lopez-Mejias R, Pina T, Blanco R, Castaneda S. IgA Vasculitis: genetics and clinical and therapeutic management. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2018;20(5):24. doi: 10.1007/s11926-018-0735-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heineke MH, van Egmond M. Immunoglobulin a: magic bullet or Trojan horse? Eur J Clin Invest. 2017;47(2):184–192. doi: 10.1111/eci.12716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aleyd E, van Hout MW, Ganzevles SH, Hoeben KA, Everts V, Bakema JE, van Egmond M. IgA enhances NETosis and release of neutrophil extracellular traps by polymorphonuclear cells via Fcalpha receptor I. J Immunol. 2014;192(5):2374–2383. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozen S, Pistorio A, Iusan SM, Bakkaloglu A, Herlin T, Brik R, Buoncompagni A, Lazar C, Bilge I, Uziel Y, Rigante D, Cantarini L, Hilario MO, Silva CA, Alegria M, Norambuena X, Belot A, Berkun Y, Estrella AI, Olivieri AN, Alpigiani MG, Rumba I, Sztajnbok F, Tambic-Bukovac L, Breda L, Al-Mayouf S, Mihaylova D, Chasnyk V, Sengler C, Klein-Gitelman M, Djeddi D, Nuno L, Pruunsild C, Brunner J, Kondi A, Pagava K, Pederzoli S, Martini A, Ruperto N, Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials, O EULAR/PRINTO/PRES criteria for Henoch-Schonlein purpura, childhood polyarteritis nodosa, childhood Wegener granulomatosis and childhood Takayasu arteritis: Ankara 2008. Part II: Final classification criteria. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(5):798–806. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.116657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rigante D, Castellazzi L, Bosco A, Esposito S. Is there a crossroad between infections, genetics, and Henoch-Schonlein purpura? Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12(10):1016–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davin JC, Coppo R. Henoch-Schonlein purpura nephritis in children. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014;10(10):563–573. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2014.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suzuki H, Yasutake J, Makita Y, Tanbo Y, Yamasaki K, Sofue T, Kano T, Suzuki Y. IgA nephropathy and IgA vasculitis with nephritis have a shared feature involving galactose-deficient IgA1-oriented pathogenesis. Kidney Int. 2018;93(3):700–705. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al Harash A, Saeli S, Lucke M, Arora S. IgA Vasculitis nephritis: a case series and comparison of treatment guidelines. Case Rep Rheumatol. 2020;2020:8863858–8863855. doi: 10.1155/2020/8863858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Z, Bagarolo GI, Thoroe-Boveleth S, Jankowski J. "Lipidomics": mass spectrometric and chemometric analyses of lipids. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2020;159:294–307. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fahy E, Subramaniam S, Brown HA, Glass CK, Merrill AH, Jr, Murphy RC, Raetz CR, Russell DW, Seyama Y, Shaw W, Shimizu T, Spener F, van Meer G, VanNieuwenhze MS, White SH, Witztum JL, Dennis EA. A comprehensive classification system for lipids. J Lipid Res. 2005;46(5):839–861. doi: 10.1194/jlr.E400004-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim JH, Gerhart-Hines Z, Dominy JE, Lee Y, Kim S, Tabata M, Xiang YK, Puigserver P. Oleic acid stimulates complete oxidation of fatty acids through protein kinase A-dependent activation of SIRT1-PGC1alpha complex. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(10):7117–7126. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.415729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niu Z, Wu Q, Sun L, Qi Q, Zheng H, Li H, Zeng R, Lin X, Zong G. Circulating Glycerolipids, fatty liver index and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a prospective study among Chinese. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(7):2010–2020. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zywno H, Bzdega W, Kolakowski A, Kurzyna P, Harasim-Symbor E, Sztolsztener K, et al. The Influence of Coumestrol on Sphingolipid Signaling Pathway and Insulin Resistance Development in Primary Rat Hepatocytes. Biomolecules. 2021;11(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Hajduch E, Lachkar F, Ferre P, Foufelle F. Roles of Ceramides in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J Clin Med. 2021;10(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Wigger D, Schumacher F, Schneider-Schaulies S, Kleuser B. Sphingosine 1-phosphate metabolism and insulin signaling. Cell Signal. 2021;82:109959. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2021.109959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romano A, Friuli M, Del Coco L, Longo S, Vergara D, Del Boccio P, et al. Chronic Oleoylethanolamide Treatment Decreases Hepatic Triacylglycerol Level in Rat Liver by a PPARgamma/SREBP-Mediated Suppression of Fatty Acid and Triacylglycerol Synthesis. Nutrients. 2021;13(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Olishevska S, Nickzad A, Deziel E. Bacillus and Paenibacillus secreted polyketides and peptides involved in controlling human and plant pathogens. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2019;103(3):1189–1215. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-9541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yin Y, Cai M, Zhou X, Li Z, Zhang Y. Polyketides in aspergillus terreus: biosynthesis pathway discovery and application. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;100(18):7787–7798. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7733-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou X, Liu L, Lan X, Cohen D, Zhang Y, Ravindran AV, Yuan S, Zheng P, Coghill D, Yang L, Hetrick SE, Jiang X, Benoliel JJ, Cipriani A, Xie P. Polyunsaturated fatty acids metabolism, purine metabolism and inosine as potential independent diagnostic biomarkers for major depressive disorder in children and adolescents. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(10):1478–1488. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0047-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jia LW, Wang C, Kong HW, Cai ZW, Xu GW. Plasma phospholipid metabolic profiling and biomarkers of mouse IgA nephropathy. Metabolomics. 2006;2(2):95–104. doi: 10.1007/s11306-006-0025-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suvitaival T, Bondia-Pons I, Yetukuri L, Poho P, Nolan JJ, Hyotylainen T, Kuusisto J, Oresic M. Lipidome as a predictive tool in progression to type 2 diabetes in Finnish men. Metabolism. 2018;78:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2017.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu L, Hu C, Zhao Y, He L, Zhou J, Li H, Du Y, Wang Y, Wen C, Han X, Fan Y. Shotgun Lipidomics Revealed Altered Profiles of Serum Lipids in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Closely Associated with Disease Activity. Biomolecules2018,8 (4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Gao R, Niu X, Zhu L, Qi R, He L. iTRAQ quantitative proteomic analysis differentially expressed proteins and signal pathways in henoch-schonlein purpura nephritis. Am J Transl Res. 2020;12(12):7908–7922. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han X. Lipidomics for studying metabolism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12(11):668–679. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tracy A, Subramanian A, Adderley NJ, Cockwell P, Ferro C, Ball S, Harper L, Nirantharakumar K. Cardiovascular, thromboembolic and renal outcomes in IgA vasculitis (Henoch-Schonlein purpura): a retrospective cohort study using routinely collected primary care data. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(2):261–269. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nordestgaard BG, Varbo A. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease. Lancet. 2014;384(9943):626–635. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenson RS, Davidson MH, Hirsh BJ, Kathiresan S, Gaudet D. Genetics and causality of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(23):2525–2540. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Artunc F, Schleicher E, Weigert C, Fritsche A, Stefan N, Haring HU. The impact of insulin resistance on the kidney and vasculature. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12(12):721–737. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2016.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heier C, Kuhnlein RP. Triacylglycerol metabolism in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2018;210(4):1163–1184. doi: 10.1534/genetics.118.301583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krahmer N, Guo Y, Wilfling F, Hilger M, Lingrell S, Heger K, Newman HW, Schmidt-Supprian M, Vance DE, Mann M, Farese RV, Jr, Walther TC. Phosphatidylcholine synthesis for lipid droplet expansion is mediated by localized activation of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase. Cell Metab. 2011;14(4):504–515. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moessinger C, Kuerschner L, Spandl J, Shevchenko A, Thiele C. Human lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferases 1 and 2 are located in lipid droplets where they catalyze the formation of phosphatidylcholine. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(24):21330–21339. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.202424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jensen PN, Fretts AM, Yu C, Hoofnagle AN, Umans JG, Howard BV, Sitlani CM, Siscovick DS, King IB, Sotoodehnia N, McKnight B, Lemaitre RN. Circulating sphingolipids, fasting glucose, and impaired fasting glucose: the strong heart family study. EBioMedicine. 2019;41:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.12.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lemaitre RN, Yu C, Hoofnagle A, Hari N, Jensen PN, Fretts AM, Umans JG, Howard BV, Sitlani CM, Siscovick DS, King IB, Sotoodehnia N, McKnight B. Circulating sphingolipids, insulin, HOMA-IR, and HOMA-B: the strong heart family study. Diabetes. 2018;67(8):1663–1672. doi: 10.2337/db17-1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chaurasia B, Summers SA. Ceramides in metabolism: key Lipotoxic players. Annu Rev Physiol. 2021;83(1):303–330. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-031620-093815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ding Y, Zhou Y, Li HR, Xiong YH, Yin W, Zhao L. Characteristics of immune function in the acute phase of Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40(9):3711–3716. doi: 10.1007/s10067-021-05707-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koenen RR. Lysophosphatidylcholine in platelet microvesicles: the grease for cardiovascular disease. Thromb Haemost. 2019;119(8):1202–1204. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1693024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diehl P, Nienaber F, Zaldivia MTK, Stamm J, Siegel PM, Mellett NA, Wessinger M, Wang X, McFadyen JD, Bassler N, Puetz G, Htun NM, Braig D, Habersberger J, Helbing T, Eisenhardt SU, Fuller M, Bode C, Meikle PJ, Chen YC, Peter K. Lysophosphatidylcholine is a major component of platelet microvesicles promoting platelet activation and reporting atherosclerotic plaque instability. Thromb Haemost. 2019;119(8):1295–1310. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1683409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jaszczura M, Gora A, Grzywna-Rozenek E, Barc-Czarnecka M, Machura E. Analysis of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, platelet to lymphocyte ratio and mean platelet volume to platelet count ratio in children with acute stage of immunoglobulin a vasculitis and assessment of their suitability for predicting the course of the disease. Rheumatol Int. 2019;39(5):869–878. doi: 10.1007/s00296-019-04274-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nording H, Langer HF. Complement links platelets to innate immunity. Semin Immunol. 2018;37:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Omma A, Colak S, Can Sandikci S, Yucel C, Erden A, Sertoglu E, Ozgurtas T. Serum neopterin and ischemia modified albumin levels are associated with the disease activity of adult immunoglobulin a vasculitis (Henoch-Schonlein purpura) Int J Rheum Dis. 2019;22(10):1920–1925. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hishikawa D, Hashidate T, Shimizu T, Shindou H. Diversity and function of membrane glycerophospholipids generated by the remodeling pathway in mammalian cells. J Lipid Res. 2014;55(5):799–807. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R046094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gorjao R, Azevedo-Martins AK, Rodrigues HG, Abdulkader F, Arcisio-Miranda M, Procopio J, Curi R. Comparative effects of DHA and EPA on cell function. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;122(1):56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vance JE. Historical perspective: phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylethanolamine from the 1800s to the present. J Lipid Res. 2018;59(6):923–944. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R084004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hannun YA. Functions of ceramide in coordinating cellular responses to stress. Science. 1996;274(5294):1855–1859. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5294.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ruvolo PP. Ceramide regulates cellular homeostasis via diverse stress signaling pathways. Leukemia. 2001;15(8):1153–1160. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lu Z, Li Y, Ru JH, Lopes-Virella MF, Lyons TJ, Huang Y. Interaction of palmitate and LPS regulates cytokine expression and apoptosis through sphingolipids in human retinal microvascular endothelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2019;178:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2018.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shao Y, Li C, Xu W, Zhang P, Zhang W, Zhao X. miR-31 Links Lipid Metabolism and Cell Apoptosis in Bacteria-Challenged Apostichopus japonicus via Targeting CTRP9. Front Immunol. 2017;8:263. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang H, Isaji T, Satoh M, Li D, Arai Y, Gu J. Antitumor effects of exogenous ganglioside GM3 on bladder cancer in an orthotopic cancer model. Urology. 2013;81(1):210 e11–210 e15. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsukuda Y, Iwasaki N, Seito N, Kanayama M, Fujitani N, Shinohara Y, Kasahara Y, Onodera T, Suzuki K, Asano T, Minami A, Yamashita T. Ganglioside GM3 has an essential role in the pathogenesis and progression of rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e40136. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kimata H, Yoshida A. Differential effects of gangliosides on Ig production and proliferation by human B cells. Blood. 1994;84(4):1193–1200. doi: 10.1182/blood.V84.4.1193.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sommer A, Twig G. The impact of childhood and adolescent obesity on cardiovascular risk in adulthood: a systematic review. Curr Diab Rep. 2018;18(10):91. doi: 10.1007/s11892-018-1062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Elblehi SS, Hafez MH, El-Sayed YS. L-alpha-phosphatidylcholine attenuates mercury-induced hepato-renal damage through suppressing oxidative stress and inflammation. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2019;26(9):9333–9342. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-04395-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee HS, Kim BK, Nam Y, Sohn UD, Park ES, Hong SA, Lee JH, Chung YH, Jeong JH. Protective role of phosphatidylcholine against cisplatin-induced renal toxicity and oxidative stress in rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;58:388–393. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li Z, Vance DE. Phosphatidylcholine and choline homeostasis. J Lipid Res. 2008;49(6):1187–1194. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R700019-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ricotti R, Solito A, Mariotti Zani E, Caputo M, Genoni G, Barone-Adesi F, Mancioppi V, Agosti E, Aimaretti G, Bellone S, Prodam F. The relationship between cortisol and IGF-I influences metabolic alteration in pediatric overweight and obesity sity. Eur J Endocrinol. 2020;182(3):255–264. doi: 10.1530/EJE-19-0792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.