Abstract

Background:

Perioperative myocardial infarction is frequently attributed to type 2 myocardial infarction, a mismatch in myocardial oxygen supply-demand without unstable coronary artery disease. Our aim was to identify characteristics, management, and outcomes of perioperative type 1 versus type 2 myocardial infarction among surgical patients hospitalized in the United States.

Methods:

Adults age ≥45 years hospitalized for non-cardiac surgery were identified in the United States. Perioperative myocardial infarction were identified using ICD-10 codes. Clinical characteristics, invasive myocardial infarction management, mortality, and readmissions were assessed by myocardial infarction subtype.

Results:

Among 4,755,382 surgical hospitalizations, we identified 38,975 perioperative myocardial infarctions (0.82%), with type 2 infarction in 42%. Patients with type 2 myocardial infarction were older, more likely to be women, and less likely to have cardiovascular comorbidities compared with type 1 myocardial infarction. Fewer patients with type 2 myocardial infarction underwent invasive management than type 1 myocardial infarction (6.7% vs. 28.8%, p<0.001). Type 2 myocardial infarction mortality was lower than type 1 myocardial infarction mortality (12.1% vs. 17.4%, p<0.001; adjusted OR 0.51, 95% CI 0.45–0.59). Invasive management of perioperative myocardial infarction was associated with lower mortality in type 1 (aOR 0.56, 95% CI 0.49–0.74) but not type 2 (aOR 1.19, 95% CI 0.77–1.85) myocardial infarction. Among survivors, there was no difference in 90-day hospital readmission between type 2 and type 1 perioperative myocardial infarction (36.5% vs. 36.1%, p=0.72).

Conclusions:

Type 2 myocardial infarctions account for ~40% of perioperative myocardial infarctions. Patients with type 2 perioperative myocardial infarction are less likely to undergo invasive management and have lower mortality compared to those with type 1 perioperative myocardial infarction.

Keywords: coronary angiography, coronary revascularization, invasive management, mortality, myocardial infarction, outcomes, percutaneous coronary intervention, perioperative, readmission, rehospitalization, type 1, type 2

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Perioperative myocardial infarction occurs in ~1% of patients age ≥45 years hospitalized for non-cardiac surgery and is associated with excess mortality.1, 2 Although a proportion of perioperative myocardial infarctions are presumed to be caused by unstable atherosclerotic coronary artery disease with coronary thrombus, many events are attributed to a mismatch in myocardial oxygen supply and demand, or Type 2 myocardial infarction, as defined by the Universal Definition.3 As currently defined, type 2 myocardial infarction can occur in the setting of stable coronary artery disease, coronary microvascular disease, coronary spasm, non-atherosclerotic coronary embolism and spontaneous coronary artery dissection.3 Data on clinical characteristics and outcomes of perioperative myocardial infarction after noncardiac surgery have not previously been reported by subtype. In October 2017, an International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision Clinical Modification (ICD-10) code specific for type 2 myocardial infarction was introduced; 2018 was the first full calendar year in which this coding was used in the United States. We sought to identify clinical characteristics, management, and outcomes of perioperative myocardial infarction by subtype in patients hospitalized for non-cardiac surgery in the United States.

Methods

Surgical Hospitalizations

Adults ≥45 years of age hospitalized for non-cardiac surgery in 2018 were identified from the United States Agency For Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project’s (HCUP) National Inpatient Sample (NIS). The NIS is a national database of discharge-level administrative data from a 20% stratified sample of non-federal hospitals. Patients undergoing a major therapeutic surgical procedure in the operating room during the index hospital admission were identified using primary ICD-10 procedure codes for non-cardiac surgery and the HCUP Procedure Class indicator. Primary non-cardiac surgeries were then clustered by ICD-10 Clinical Classifications Software Refined (CCSR) codes into the following major surgical subtypes: endocrine surgery, otolaryngology, general surgery, genitourinary, gynecologic, neurosurgery, obstetrics, orthopedics, skin/breast, thoracic, transplant, and vascular surgery. Patients undergoing primary diagnostic procedures, cardiac surgery or invasive cardiology procedures, radiation therapy, dental surgery, and eye surgery were excluded.

In-Hospital Management and Outcomes

Perioperative myocardial infarction was identified by ICD-10 diagnosis codes during hospital admission. Type 2 myocardial infarctions were defined by ICD-10 code ‘I21A1’. Type 1 myocardial infarctions were identified by ICD-10 codes for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, with coding as specified in the Appendix. Invasive management of type 2 myocardial infarction was defined as in-hospital invasive coronary angiography, percutaneous coronary intervention, or coronary artery bypass grafting, as defined by ICD-10 and CCSR procedure codes during hospitalization (Appendix). Patients who did not undergo invasive coronary angiography or revascularization for perioperative myocardial infarction were considered to have been managed conservatively. Other relevant events during hospitalization, including the need for mechanical ventilation and vasopressor use for shock, were identified based on ICD-10 diagnosis and procedure codes. In-hospital, all-cause mortality was recorded for all patients based on the NIS discharge disposition.

Hospital Readmission after Perioperative Myocardial Infarction

To evaluate the frequency of hospital readmission after perioperative myocardial infarction, stratified by subtype, a cohort of adults ≥45 years of age hospitalized for non-cardiac surgery in the first 9 months of 2018 were identified from the AHRQ HCUP Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD), using definitions of non-cardiac surgery as previously described above. Ninety-day hospital readmissions were identified based on methodology outlined by HCUP.4 We restricted this analysis to patients discharged between January and September 2018 to ensure complete 90-day follow-up for all patients within the calendar year. Among patients with multiple readmissions within 90-days after perioperative myocardial infarction, only the first readmission was included in the all-cause readmission analysis. Primary ICD-10 diagnosis codes were used to determine the indication for hospital readmission and clustered into predefined CCSR categories. To ensure complete capture of recurrent ischemic events that may not have occurred during the first re-hospitalization, 90-day first readmission for myocardial infarction was also assessed separately. In-hospital, all-cause mortality was identified from the discharge disposition during hospital readmissions.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are reported as mean ± standard error (SE) and compared using logistic regression. Categorical variables are reported as percentages and compared by Pearson’s χ2 tests. Multivariable logistic regression models were generated to estimate odds ratios (OR) adjusted for patient demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, and comorbidities. Models included all covariates with a univariate p-value <0.1 for the comparison between myocardial infarction subtypes (Supplemental Appendix). Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate hazard ratios for hospital readmission associated with each myocardial infarction subtype.

Sampling weights were applied to determine national incidence estimates according to HCUP guidance. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 27 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical tests are two-sided and with significance levels set at <0.05. The NIS and NRD are publicly available, de-identified datasets, and this analysis did not require approval by an Institutional Review Board.

Results

A total of 4,755,382 hospitalizations for non-cardiac surgery were identified in the 2018 NIS; perioperative myocardial infarction was diagnosed in 38,975 (0.82%). Among hospitalizations with perioperative myocardial infarction, 16,285 (41.8%) had type 2 myocardial infarction, 22,495 (57.7%) had type 1 myocardial infarction, and 195 (0.5%) had both type subtypes coded. Among patients with type 1 perioperative myocardial infarction during the surgical hospitalization, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction was reported in 13.6% cases.

Overall, patients with perioperative myocardial infarction had a mean age of 72.0 years, 45.3% were women, and there was a high prevalence of cardiovascular disease and non-cardiovascular comorbidities. Characteristics of patients by subtype of myocardial infarction are reported in Table 1. Patients with type 2 myocardial infarction were older, more likely to be female, and were less likely to have hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and peripheral artery disease compared with patients with type 1 myocardial infarction. Coronary artery disease was reported in a smaller proportion of patients with type 2 versus type 1 perioperative myocardial infarction (44.4% vs. 63.6%, p<0.001). Patients with perioperative type 2 myocardial infarction were more likely to have documented atrial arrhythmias, coagulopathy, fluid and electrolyte disorders, liver disease, and weight loss compared with those who had type 1 myocardial infarction (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with type 1 versus type 2 myocardial infarction during hospitalization for non-cardiac surgery.

| No Perioperative Myocardial Infarction (n=4716407) | Type 1 Myocardial Infarction (n=22495) | Type 2 Myocardial Infarction (n=16285) | p-value * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years; mean (SEM) | 66.41 (0.045) | 71.71 (0.18) | 72.39 (0.22) | 0.013 |

| Female Sex (%) | 2541123 (53.9%) | 9720 (43.2%) | 7865 (48.3%) | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.045 | |||

| White | 3525658 (74.8%) | 16195 (72%) | 11985 (73.6%) | |

| Black | 462215 (9.8%) | 2335 (10.4%) | 1880 (11.5%) | |

| Hispanic | 379399 (8%) | 1935 (8.6%) | 1095 (6.7%) | |

| Asian | 92585 (2%) | 645 (2.9%) | 395 (2.4%) | |

| Other | 137600 (2.9%) | 750 (3.3%) | 500 (3.1%) | |

| Missing | 118950 (2.5%) | 635 (2.8%) | 430 (2.6%) | |

| Cardiovascular Risk Factors & Disease | ||||

| Tobacco Use | 598035 (12.7%) | 3195 (14.2%) | 1955 (12%) | 0.004 |

| Hypertension | 3046709 (64.6%) | 16815 (74.7%) | 11740 (72.1%) | 0.011 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1990664 (42.2%) | 11560 (51.4%) | 7080 (43.5%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes Mellitus (any) | 1275385 (27%) | 10080 (44.8%) | 6700 (41.1%) | 0.001 |

| without chronic complications | 572290 (12.1%) | 2085 (9.3%) | 1175 (7.2%) | 0.001 |

| with chronic complications | 703095 (14.9%) | 7995 (35.5%) | 55?5 (33.9%) | 0.130 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 638185 (13.5%) | 8745 (38.9%) | 6455 (39.6%) | 0.500 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 829495 (17.6%) | 14310 (63.6%) | 7225 (44.4%) | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 377675 (8%) | 9565 (42.5%) | 6965 (42.8%) | 0.824 |

| Valvular heart disease | 203400 (4.3%) | 3005 (13.4%) | 2195 (13.5%) | 0.877 |

| Atrial Fibrillation and Flutter | 541730 (11.5%) | 6945 (30.9%) | 5605 (34.4%) | 0.001 |

| Pulmonary circulatory disease | 26235 (0.6%) | 750 (3.3%) | 545 (3.3%) | 0.976 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 309185 (6.6%) | 4590 (20.4%) | 2745 (16.9%) | <0.001 |

| Other Comorbidities | ||||

| Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome | 6695 (0.1%) | 35 (0.2%) | 60 (0.4%) | 0.068 |

| Alcohol abuse | 128225 (2.7%) | 985 (4.4%) | 735 (4.5%) | 0.774 |

| Anemia (any) | 694695 (14.7%) | 7055 (31.4%) | 4710 (28.9%) | 0.032 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 878570 (18.6%) | 5700 (25.3%) | 4120 (25.3%) | 0.970 |

| Coagulopathy | 194120 (4.1%) | 3125 (13.9%) | 3010 (18.5%) | <0.001 |

| Dementia | 194060 (4.1%) | 2040 (9.1%) | 1630 (10%) | 0.182 |

| Depression | 638955 (13.5%) | 2400 (10.7%) | 1945 (11.9%) | 0.085 |

| Drug abuse | 81030 (1.7%) | 560 (2.5%) | 390 (2.4%) | 0.793 |

| Fluid and Electrolyte Disorders | 892560 (18.9%) | 12800 (56.9%) | 10440 (64.1%) | <0.001 |

| Hypothyroidism | 705995 (15%) | 3195 (14.2%) | 2310 (14.2%) | 0.982 |

| Liver Disease | 182665 (3.9%) | 940 (4.2%) | 970 (6%) | <0.001 |

| Malignancy (any) | 248310 (5.3%) | 1635 (7.3%) | 1360 (8.4%) | 0.060 |

| Obesity | 972575 (20.6%) | ?j35 (17%) | 2630 (16.1%) | 0.299 |

| Other neurological disorders | 327640 (6.9%) | 2660 (11.8%) | 2035 (12.5%) | 0.373 |

| Paralysis | 136180 2.9%) | 1750 (7.8%) | 1325 (8.1%) | 0.580 |

| Peptic Ulcer Disease | 34115 (0.7%) | 615 (2.7%) | 485 (3%) | 0.514 |

| Psychoses | 118795 (2.5%) | 545 (2.4%) | 455 (2.8%) | 0.303 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis / Collagen vascular disease | 187145 (4%) | 700 (3.1%) | 600 (3.7%) | 0.194 |

| Weight loss | 247730 (5.3%) | 3805 (16.9%) | 3340 (20.5%) | <0.001 |

| Primary Insurance Payer | 0.005 | |||

| Medicare | 2677509 (56.8%) | 16295 (72.6%) | 12340 (75.9%) | |

| Medicaid | 356180 (7.6%) | 1745 (7.8%) | 1140 (7%) | |

| Private Insurance | 1423119 (30.2%) | 3395 (15.1%) | 2130 (13.1%) | |

| Self-Pay | 94085 (2%) | 545 (2.4%) | 265 (1.6%) | |

| Other / Unknown | 165515 (3.5%) | 515 (2.3%) | 410 (2.5%) | |

| Hospital Size | 0.033 | |||

| Small | 1025961 (21.8%) | 3600 (16%) | 2350 (14.4%) | |

| Medium | 1310325 (27.8%) | 6570 (29.2%) | 4320 (26.5%) | |

| Large | 2380122 (50.5%) | 12325 (54.8%) | 9615 (59%) | |

| Hospital Location / Teaching Status | <0.001 | |||

| Rural | 315053 (6.7%) | 1650 (7.3%) | 915 (5.6%) | |

| Urban non-teaching | 959391 (20.3%) | 4100 (18.2%) | 2150 (13.2%) | |

| Urban teaching | 3441963 (73%) | 16745 (74.4%) | 13220 (81.2%) | |

| Region | ||||

| Northeast | 859688 (18.2%) | 3900 (17.3%) | 3950 (24.3%) | <0.001 |

| Midwest | 1083114 (23%) | 5155 (22.9%) | 4150 (25.5%) | |

| South | 1808627 (38.3%) | 9085 (40.4%) | 5140 (31.6%) | |

| West | 964979 (20.5%) | 4355 (19.4%) | 3045 (18.7%) |

P-value for the comparison of type 2 vs. type 1 MI.

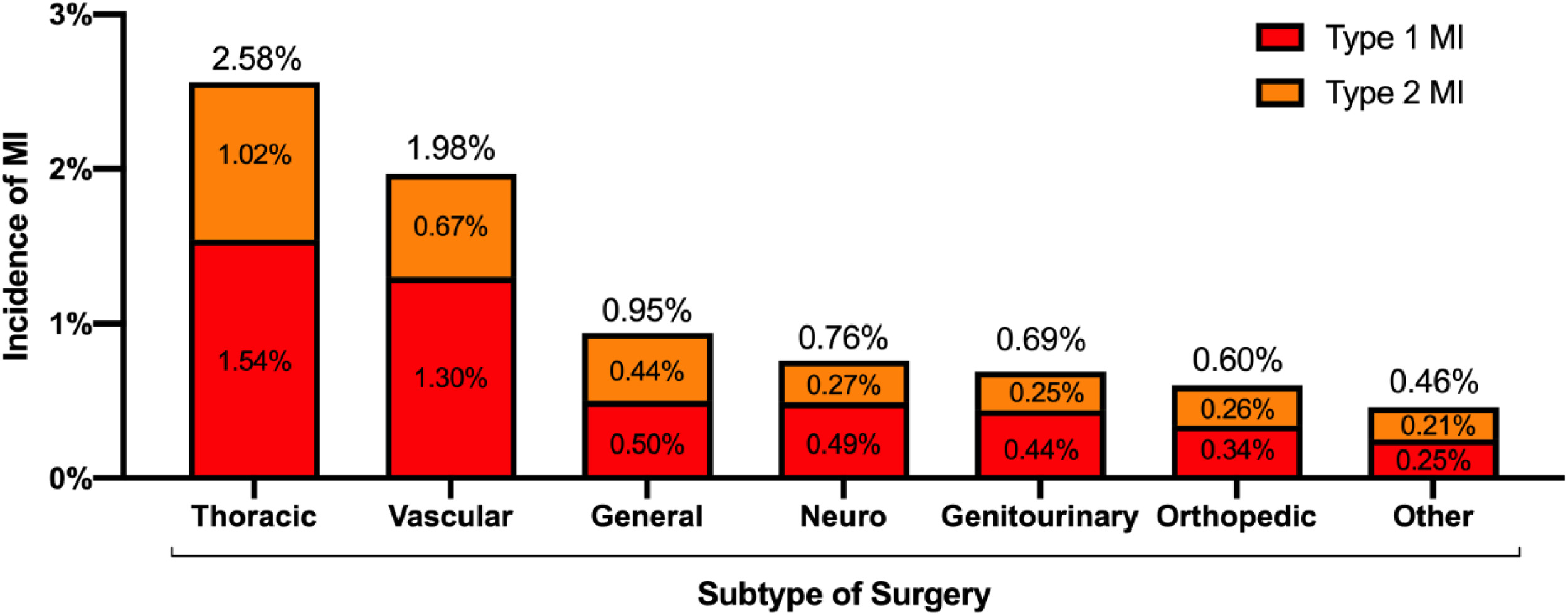

Surgical characteristics and management of patients by perioperative myocardial infarction subtype are reported in Table 2. Elective hospitalization for non-cardiac surgery was less common in patients with type 2 versus type 1 perioperative myocardial infarction (15.4% vs. 21.5%, p<0.001). The incidences of both subtypes of perioperative myocardial infarction were greatest in thoracic, vascular, and general surgeries (Figure 1), but perioperative myocardial infarction following general (46.9%), orthopedic (43.8%), and thoracic surgeries (40.3%) were more likely to be classified as type 2 than type 1 myocardial infarction. Among vascular surgery, only 34.5% were classified as type 2 myocardial infarction. Women and older adults with perioperative myocardial infarction were more likely to have type 2 perioperative myocardial infarction than men and younger adults, respectively (Supplemental Figure 1).

Table 2.

In-hospital management of patients with type 1 versus type 2 MI during hospitalization for non-cardiac surgery.

| No Perioperative Myocardial Infarction | Type 1 Myocardial Infarction | Type 2 Myocardial Infarction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=4716407) | (n=22495) | (n=16285) | p-value * | |

|

| ||||

| Elective Surgical Hospitalization | 2826042 (59.9%) | 4835 (21.5%) | 2510 (15.4%) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Primary Non-Cardiac Surgery Procedure | <0.001 | |||

| Orthopedic Surgery | 2661628 (56.4%) | 9025 (40.1%) | 6950 (42.7%) | |

| General Surgery | 973950 (20.7%) | 4955 (22%) | 4340 (26.7%) | |

| Vascular Surgery | 308045 (6.5%) | 4070 (18.1%) | 2105 (12.9%) | |

| Genitourinary Surgery | 213115 (4.5%) | 940 (4.2%) | 545 (3.3%) | |

| Neurosurgery | 184825 (3.9%) | 915 (4.1%) | 500 (3.1%) | |

| Thoracic Surgery | 124115 (2.6%) | 1960 (8.7%) | 1305 (8%) | |

| Gynecologic Surgery | 119200 (2.5%) | 120 (0.5%) | 100 (0.6%) | |

| Skin/Breast Surgery | 52415 (1.1%) | 160 (0.7%) | 155 (1%) | |

| Otolaryngology | 28550 (0.6%) | 105 (0.5%) | 75 (0.5%) | |

| Endocrine Surgery | 23875 (0.5%) | 65 (0.3%) | 65 (0.4%) | |

| Transplant Surgery | 21545 (0.5%) | 175 (0.8%) | 145 (0.9%) | |

| MI Management | ||||

| Invasive Management | 12455 (0.3%) | 6485 (28.8%) | 1085 (6.7%) | <0.001 |

| Diagnostic Catheterization | 10875 (0.2%) | 5610 (24.9%) | 1050 (6.4%) | <0.001 |

| Coronary Revascularization | 2805 (0.1%) | 3360 (14.9%) | 170 (1%) | <0.001 |

| Percutaneous Coronary Intervention | 1250 (0%) | 2705 (12%) | 165 (1%) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory Failure | 290520 (6.2%) | 10085 (44.8%) | 7600 (46.7%) | 0.11 |

| Mechanical Ventilation | 132865 (2.8%) | 6340 (28.2%) | 4290 (26.3%) | 0.092 |

| Any Shock | 111135 (2.4%) | 6040 (26.9%) | 4750 (29.2%) | 0.029 |

| Cardiogenic Shock | 6995 (0.1%) | 2145 (9.5%) | 610 (3.7%) | <0.001 |

| Septic Shock | 68680 (1.5%) | 3320 (14.8%) | 3305 (20.3%) | <0.001 |

| Hypovolemic Shock | 15180 (0.3%) | 495 (2.2%) | 570 (3.5%) | <0.001 |

| Vasopressor Use | 42740 (0.9%) | 1335 (5.9%) | 1190 (7.3%) | 0.032 |

P-value for the comparison of type 2 vs. type 1 MI.

Figure 1.

Incidence of type 1 and type 2 perioperative myocardial infarction by surgical subtype

Management

Invasive management with coronary angiography, with or without revascularization, was performed in 19.5% of all myocardial infarctions. The proportion of patients undergoing invasive management was lower in type 2 versus type 1 perioperative myocardial infarction (6.7% vs. 28.8%, p<0.001; Supplemental Figure 2). Among patients with type 2 myocardial infarction who underwent invasive coronary evaluation, coronary revascularization was performed in 15.7% (≈1% of all perioperative type 2 myocardial infarction), of which 97% underwent percutaneous coronary intervention. In contrast, 51.8% of patients with invasive management of type 1 perioperative myocardial infarction underwent coronary revascularization during hospitalization (~14.9% of all type 1 perioperative myocardial infarction), of which 80.5% underwent percutaneous coronary intervention.

Outcomes:

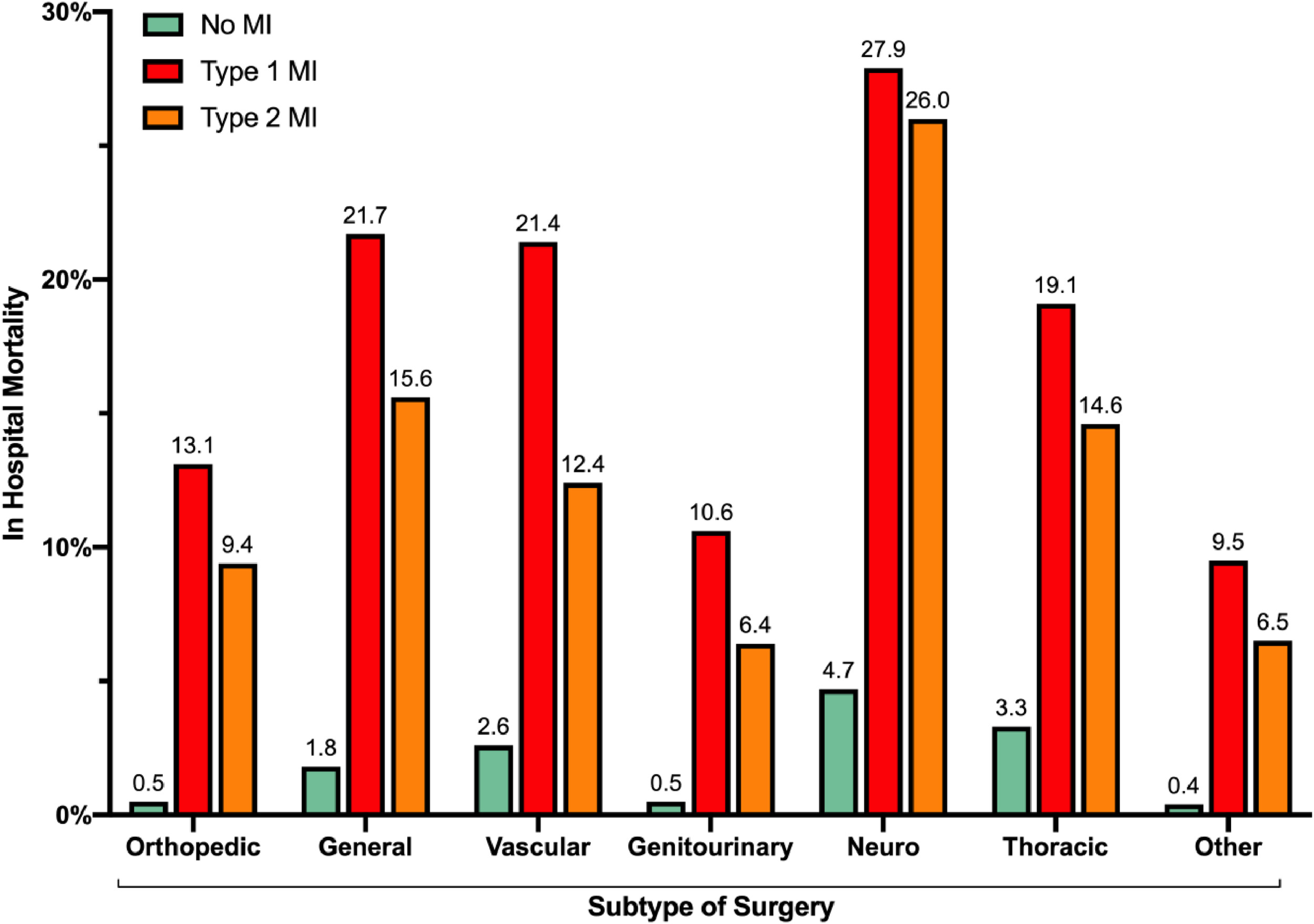

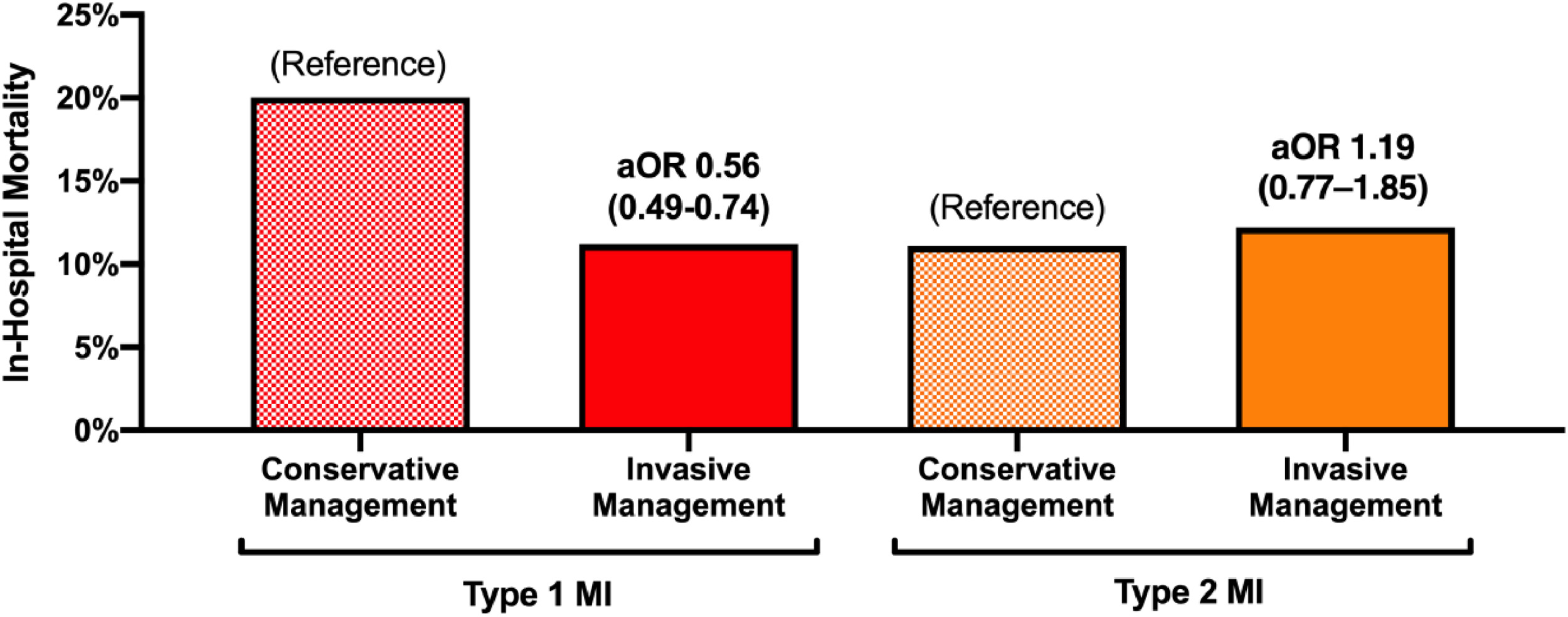

Among patients hospitalized with a diagnosis of perioperative myocardial infarction, the median length of stay was 10 days (IQR 6–18 days), with no difference by myocardial infarction subtype (p=0.28). In-hospital mortality in patients without myocardial infarction was 1.2%, compared to 12.1% with type 2 myocardial infarction, and 17.4% with type 1 myocardial infarction (Table 3). Type 2 myocardial infarction was associated with lower in-hospital mortality than type 1 myocardial infarction in all surgical subtypes (Figure 2). After adjustment for clinical covariates, the odds of mortality associated with type 2 myocardial infarction was lower than that for type 1 myocardial infarction (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.51, 95% CI 0.45–0.59). Compared to patients without perioperative myocardial infarction, those who experienced either type 2 (aOR 20.8, 95% CI 17.5–24.8) or type 1 myocardial infarction (aOR 213.6, 95% CI 159.7–285.7) had greater odds of in-hospital mortality. Invasive management of perioperative myocardial infarction was associated with a lower risk of in-hospital mortality among patients with type 1 (11.2% vs. 20.0%; aOR 0.56, 95% CI 0.49–0.74) but not type 2 (12.2% vs. 11.1%; aOR 1.19, 95% CI 0.77 – 1.85) myocardial infarction (Figure 3).

Table 3.

Outcomes of patients with type 1 versus type 2 perioperative myocardial infarction during hospitalization for non-cardiac surgery.

| No Perioperative Myocardial Infarction | Type 1 Myocardial Infaictk n | Type 2 Myocardial Infarction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=4716407) | (n=22495) | (n=16285) | p-value * | |

| Length of Stay, days | 3 (2–6) | 10 (6–17) | 10 (6–18) | 0.279 |

| Disposition | ||||

| Routine Discharge | 2434588 (51.6%) | 3865 (17.2%) | 2765 (17%) | 0.824 |

| Discharge with Home Healthcare | 1099129 (23.3%) | 3080 (13.7%) | 2435 (15%) | 0.133 |

| Nursing or Intermediate Care Facility | 1085485 (23%) | 10160 (45.2%) | 8560 (52.6%) | <0.001 |

| Transfer to Another Facility | 30060 (0.6%) | 1325 (5.9%) | 500 (3.1%) | <0.001 |

| Against Medical Advice | 11785 (0.2%) | 135 (0.6%) | 45 (0.3%) | 0.041 |

| Other / Unknown | 1070 (0%) | <20 (0%) | <20 (0%) | 0.761 |

| In-Hospital Mortality, n (%) | 54290 (1.2%) | 3920 (17.4%) | 1975 (12.1%) | <0.001 |

P-value for the comparison of type 2 vs. type 1 MI.

Figure 2.

Post-operative in-hospital mortality in patients with type 1, type 2, and no perioperative myocardial infarction, stratified by surgical subtype.

Figure 3.

Post-operative in-hospital mortality in patients with type 1 and type 2 myocardial infarction, stratified by invasive versus conservative management.

Hospital Readmission

In a cohort of 3,361,315 surgical hospitalizations from January to September in the 2018 NRD, perioperative myocardial infarction was diagnosed in 26,631 (0.79%), with 10,501 (39.4%) type 2 myocardial infarction, 15,766 (59.2%) type 1 myocardial infarction, and 363 (1.4%) with both myocardial infarction subtypes. Among patients with perioperative myocardial infarction who survived to hospital discharge, there was no difference in 90-day all-cause readmission between those with type 1 and type 2 myocardial infarction (36.1% vs. 36.5%, p=0.72; HR 1.00 [95% CI 0.94–1.06] for type 2 versus type 1 myocardial infarction). However, the proportion of patients readmitted within 90-days following either myocardial infarction was greater than the 17.2% 90-day readmission observed in patients without perioperative myocardial infarction (p<0.001; HR 2.38 [95% CI 2.29–2.47] for type 1 myocardial infarction versus no myocardial infarction; HR 2.38 [95% CI 2.27–2.49] for type 2 myocardial infarction versus no myocardial infarction). Indications for hospital readmission stratified by myocardial infarction subtype are presented in Table 4. The most common indications for readmission by system were circulatory disorders, infectious diseases, and digestive system disorders. Hospital readmission with a second acute myocardial infarction within 90-days occurred in 6.7% of patients with type 2 and 8.7% of patients with type 1 perioperative myocardial infarction, versus 0.5% in those without perioperative myocardial infarction during the index surgical hospitalization (Table 4, Supplemental Figure 3). Among patients with type 1 perioperative myocardial infarction during their index surgical hospitalization who had a hospital readmission for another myocardial infarction within 90 days, 83.2% had recurrent type 1 myocardial infarction. In contrast, among those with type 2 perioperative myocardial infarction during the index surgical hospitalization, only 45.3% of myocardial infarction readmissions were categorized as type 1 myocardial infarction. There was no relationship between invasive management of myocardial infarction during the index surgical hospitalization and the proportion of patients readmitted at 90-days.

Table 4.

90-day hospital readmission following type 1 versus type 2 perioperative myocardial infarction during hospitalization for non-cardiac surgery.†

| No Perioperative Myocardial Infarction | Type 1 Myocardial Infarction | Type 2 Myocardial Infarction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=3295866) | (n=12950) | (n=9209) | p-value ** | |

|

| ||||

| 90-Day Hospital Readmission | 568270 (17.2%) | 4675 (36.1%) | 3357 (36.5%) | 0.72 |

| Primary Diagnosis During Hospital Readmission: | ||||

| Diseases of the Circulatory System | 73388 (12.9%) | 1277 (27.3%) | 707 (21.1%) | |

| Injury, Poisoning and External Causes* | 118439 (20.8%) | 706 (15.1%) | 598 (17.8%) | |

| Infectious and Parasitic Diseases | 50445 (8.9%) | 619 (13.2%) | 493 (14.7%) | |

| Diseases of the Digestive System | 74.82 (13.2%) | 526 (11.3%) | 422 (12.6%) | |

| Diseases of the Genitourinary System | 7878 (6.7%) | 360 (7.7%) | 238 (7.1%) | |

| Diseases of the Respiratory System | 31989 (5.6%) | 365 (7.8%) | 226 (6.7%) | |

| Endocrine, Nutritional and Metabolic Diseases | 28527 (5%) | 235 (5%) | 178 (5.3%) | |

| Diseases of the Nervous System | 16924 (3%) | 115 (2.5%) | 94 (2.8%) | |

| Musculoskeletal and Connective Tissue Diseases | 61045 (10.7%) | 83 (1.8%) | 76 (2.3%) | |

| Diseases of the Blood and Immune Mechanism | 6225 (1.1%) | 67 (1.4%) | 87 (2.6%) | |

| Neoplasms | 23258 (4.1%) | 70 (1.5%) | 73 (2.2%) | |

| Diseases of the Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue | 14656 (2.6%) | 78 (1.7%) | 49 (1.5%) | |

| Mental Health and Behavioral Disorders | 5343 (0.9%) | <20 (0.4%) | 22 (0.7%) | |

| Other | 24422 (4.1%) | 14 6 (3.1%) | 94 (2.8%) | |

| Unknown | 751 (0.1%) | <20 (0.2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| In-Hospital Mortality during First Readmission | 17723 (3.1%) | 390 (8.3%) | 249 (7.4%) | 0.26 |

| 90-Day Readmission for Myocardial Infarction | 17139 (0.52%) | 1125 (8.7%) | 616 (6.7%) | <0.001 |

| Myocardial Infarction Subtype During Readmission | <0.001 | |||

| Type 1 Myocardial Infarction | 11016 (64.3%) | 937 (83.2%) | 279 (45.3%) | |

| Type 2 Myocardial Infarction | 5927 (34.6%) | 180 (16%) | 329 (53.4%) | |

| Type 1 + Type 2 Myocardial Infarction | 196 (1.1%) | <20 (0.8%) | <20 (1.3%) | |

| In-Hospital Mortality during Myocardial Infarction Readmission | 2357 (13.8%) | 174 (15.5%) | 76 (12.3%) | 0.19 |

Data reflects patients with and without perioperative MI from the 2018 Nationwide Readmission Database.

Injury, Poisoning and External Causes includes: fractures, sprains, wounds, amputations, allergic reactions, drug reactions, poisoning/toxicities, and complications of devices, implants or grafts, as defined by the HCUP CCSR category.

*P-value for the comparison of type 2 vs. type 1 myocardial infarction.

Discussion

In the first full year of type 2 myocardial infarction ICD-10 coding from the United States, perioperative myocardial infarction was reported in 0.8% of non-cardiac surgical hospitalizations for adults age ≥45 years, and type 2 myocardial infarction represented 42% of all perioperative myocardial infarction. Perioperative myocardial infarction following general, orthopedic, and thoracic surgeries were more likely to be classified as type 2 myocardial infarction, while perioperative myocardial infarction following vascular surgery were more likely to be classified as type 1 myocardial infarction. Patients with type 2 perioperative myocardial infarction were older, more likely to be women, less likely to have cardiovascular co-morbidities, and more likely to have been hospitalized for urgent or emergent surgery than patients with type 1 myocardial infarction.

This analysis provides important new data on the national incidence of perioperative type 2 perioperative myocardial infarction. In a prior single-center study of 54 patients with perioperative myocardial infarction after non-cardiac surgery, 41% were adjudicated to have type 2 myocardial infarction.5 Other non-cardiac surgery series reported higher proportions of type 2 myocardial infarction; among 146 patients with post-operative acute coronary syndrome who underwent coronary angiography, type 2 myocardial infarction was adjudicated in 72.6%.6 In a separate analysis of 250 perioperative myocardial infarction after vascular surgery, 64% were determined to be type 2 myocardial infarction.7 In an autopsy study of fatal perioperative myocardial infarction, plaque rupture consistent with type 1 myocardial infarction was present in only 46% of cases.8

While nearly 1 in 3 patients with perioperative type 1 myocardial infarction were evaluated with invasive coronary angiography during the surgical hospitalization, only 1 in 15 patients with type 2 myocardial infarction underwent invasive management. Among patients referred for invasive angiography, more than half of type 1 myocardial infarction patients underwent coronary revascularization, while revascularization was pursued in only 1 in 6 of such patients with type 2 myocardial infarction. The low frequency of invasive angiography and revascularization observed in the current analysis is consistent with type 2 myocardial infarction management beyond the post-operative setting and reflects uncertainty regarding the optimal care of patients with type 2 myocardial infarction.9–13 Despite this, a high prevalence of obstructive coronary artery disease has been reported in perioperative type 2 myocardial infarction patients who undergo coronary angiography. In an angiographic series of 31 patients with perioperative myocardial injury, 77.4% had obstructive coronary artery disease.14 In a separate study of 146 patients with perioperative myocardial infarction, of which the majority were classified as type 2, obstructive coronary artery disease was reported in 73.3%.6 Thus, significant coronary disease may be under-diagnosed among patients with perioperative type 2 myocardial infarction. Notably, we observed that invasive management of type 1, but not type 2, perioperative myocardial infarction was associated with a lower risk of in-hospital mortality. This differs from previously reported associations between invasive management and mortality in cohorts that included medical and surgical patients with type 2 myocardial infarction.15 This may reflect differences in the potential risk/benefit assessment of revascularization by myocardial infarction subtype in the post-operative setting. For example, many patients with type 2 myocardial infarction may be at increased risk of bleeding with dual antiplatelet therapy due to anemia or the post-surgical state. Type 2 myocardial infarction patients may also have stable coronary artery disease in the setting of post-operative fever, tachycardia, hypotension or heart failure, all of which may be best addressed with medical therapies rather than coronary revascularization. Alternatively, it may reflect differential referral biases by myocardial infarction subtype, particularly since few patients with type 2 myocardial infarction who underwent invasive management received coronary revascularization.

Although we report favorable in-hospital outcomes of type 2 myocardial infarction compared to type 1 myocardial infarction, mortality occurred in 1 in every 8 hospitalizations with type 2 perioperative myocardial infarction. Mortality was highest in patients with type 2 myocardial infarction during hospitalization for neurosurgery, general, and thoracic surgery. Our data are consistent with prior studies; in an analysis of 250 patients with post-op myocardial infarction after vascular surgery, type 1 myocardial infarction was associated with higher short-term mortality than type 2 myocardial infarction. However, long-term survival did not differ between patients with perioperative type 1 and type 2 myocardial infarction.7 In prior studies, anemia, hypotension, hypoxia, and multiple inciting mechanisms were associated with poor long-term survival after type 2 myocardial infarction.9

Patients with perioperative myocardial infarction had high risk of hospital readmission at 90-days compared to patients without perioperative myocardial infarction, and we observed no difference in the risk of all-cause hospital readmission by myocardial infarction subtype. Patients with type 1 perioperative myocardial infarction were slightly more likely than those with type 2 myocardial infarction to be readmitted with any type of myocardial infarction within 90 days, and were significantly more likely to have a recurrent type 1 myocardial infarction. These are the first analyses to report 90-day rates of hospital readmission by perioperative myocardial infarction subtype.

Study Limitations

To our knowledge, this is the largest analysis of perioperative myocardial infarction classified by subtype, representing nearly forty thousand myocardial infarctions from a cohort of nearly five million surgical hospitalizations. However, there are important limitations. First, as in all retrospective analyses, miscoding or misclassification may be present, which could underestimate the frequency of type 2 myocardial infarction. Second, the NIS and NRD do not record results of laboratory testing and cardiac biomarker concentrations remain unknown. The frequency of post-operative troponin surveillance could not be ascertained.16, 17 Although the peak troponin concentration could not be assessed in this analysis, prior studies of type 2 perioperative myocardial infarction reported lower peak troponin concentrations compared with type 1 myocardial infarction.5 Third, the current ICD-10 coding for type 2 myocardial infarction does not differentiate non–ST-segment elevation from ST-segment elevation type 2 myocardial infarction, nor does it provide insights into the mechanism of infarction. Underlying mechanisms of type 2 myocardial infarction are not captured by diagnosis codes. Hemodynamic derangements in the perioperative period, such as hypotension, hypertension, tachyarrhythmia, and anemia, and vascular causes of type 2 myocardial infarction, including spontaneous coronary artery dissection, coronary embolism, or spasm could not be reliably identified.10, 18, 19 Fourth, cardiology involvement has been shown to impact the management of type 2 myocardial infarction, but we were unable to determine whether cardiovascular consultation was performed during the surgical admission.20 Fifth, although the sequence of non-cardiac surgery preceding myocardial infarction could not be definitively established from the NIS and NRD, major non-cardiac surgery is contraindicated early after acute myocardial infarction, and patients presenting with myocardial infarction would be unlikely to undergo an unrelated non-cardiac surgery during the same hospital admission. Sixth, medical therapy could not be ascertained from the NIS or NRD, and relationships between in-hospital medical therapy and outcomes of perioperative type 2 myocardial infarction remain uncertain. Finally, although we report 90-day rates of rehospitalization, out-of hospital mortality and long-term outcomes were not available from the NIS or NRD. Significant long-term mortality has previously been reported in patients with myocardial injury after non-cardiac surgery and perioperative type 2 myocardial infarction.10, 21, 22

Conclusions

Perioperative myocardial infarction occurs in 0.8% of noncardiac surgeries, and approximately 40% are classified as type 2 myocardial infarction. Few patients with perioperative type 2 myocardial infarction undergo invasive evaluation for coronary artery disease or coronary revascularization during the surgical hospitalization. Although type 2 myocardial infarction carries a more favorable prognosis than type 1 myocardial infarction, mortality after type 2 perioperative myocardial infarction is high and readmissions are common. Prospective studies are needed to inform the optimal management of perioperative myocardial infarction by subtype after non-cardiac surgery.

Supplementary Material

Funding

Dr. Smilowitz is supported, in part, by the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23HL150315. Dr. Berger is funded, in part, by the National Heart and Lung Blood Institute of the National Institute of Health (R01HL139909 and R35HL144993). Dr. Shah is partially supported by funding from the VA Office of Research and Development (iK2CX001074) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (1R01HL146206, 3R01HL146206-02S1).

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Smilowitz serves on an advisory board for Abbott Vascular. Dr. Garcia reports institutional research grants from Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, and BSCI. Dr. Garcia serves as a proctor for Edwards Lifesciences and a consultant for Medtronic, Abbott Vascular and Neochord. Dr. Shah serves on advisory boards for Philips Volcano and as a consultant with Terumo Medical. The remainder of the authors report no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Smilowitz NR, Gupta N, Guo Y, Berger JS, Bangalore S. Perioperative acute myocardial infarction associated with non-cardiac surgery. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:2409–2417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smilowitz NR, Gupta N, Ramakrishna H, Guo Y, Berger JS, Bangalore S. Perioperative major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events associated with noncardiac surgery. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:181–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Chaitman BR, Bax JJ, Morrow DA, White HD, Executive Group on behalf of the Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/World Heart Federation Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial I. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). Circulation. 2018;138:e618–e651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrett M, Steiner C, Andrews R, Kassed C, Nagamine M. Methodological issues when studying readmissions and revisits using hospital adminstrative data. HCUP Methods Series Report # 2011–01. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanson I, Kahn J, Dixon S, Goldstein J. Angiographic and clinical characteristics of type 1 versus type 2 perioperative myocardial infarction. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;82:622–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Helwani MA, Amin A, Lavigne P, Rao S, Oesterreich S, Samaha E, Brown JC, Nagele P. Etiology of acute coronary syndrome after noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2018;128:1084–1091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reed GW, Horr S, Young L, Clevenger J, Malik U, Ellis SG, Lincoff AM, Nissen SE, Menon V. Associations between cardiac troponin, mechanism of myocardial injury, and long-term mortality after noncardiac vascular surgery. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen MC, Aretz TH. Histological analysis of coronary artery lesions in fatal postoperative myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Pathol. 1999;8:133–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raphael CE, Roger VL, Sandoval Y, Singh M, Bell M, Lerman A, Rihal CS, Gersh BJ, Lewis B, Lennon RJ, Jaffe AS, Gulati R. Incidence, trends, and outcomes of type 2 myocardial infarction in a community cohort. Circulation. 2020;141:454–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smilowitz NR, Subramanyam P, Gianos E, Reynolds HR, Shah B, Sedlis SP. Treatment and outcomes of type 2 myocardial infarction and myocardial injury compared with type 1 myocardial infarction. Coron Artery Dis. 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saaby L, Poulsen TS, Hosbond S, Larsen TB, Pyndt Diederichsen AC, Hallas J, Thygesen K, Mickley H. Classification of myocardial infarction: Frequency and features of type 2 myocardial infarction. Am J Med. 2013;126:789–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stein GY, Herscovici G, Korenfeld R, Matetzky S, Gottlieb S, Alon D, Gevrielov-Yusim N, Iakobishvili Z, Fuchs S. Type-ii myocardial infarction--patient characteristics, management and outcomes. PLoS One. 2014;9:e84285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hung J, Roos A, Kadesjo E, McAllister DA, Kimenai DM, Shah ASV, Anand A, Strachan FE, Fox KAA, Mills NL, Chapman AR, Holzmann MJ. Performance of the grace 2.0 score in patients with type 1 and type 2 myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ujueta F, Berger JS, Smilowitz N. Coronary angiography in patients with perioperative myocardial injury after non-cardiac surgery. J Invasive Cardiol. 2018;30:E90–E92 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCarthy CP, Kolte D, Kennedy KF, Vaduganathan M, Wasfy JH, Januzzi JL Jr. Patient characteristics and clinical outcomes of type 1 versus type 2 myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:848–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Botto F, Alonso-Coello P, Chan MT, Villar JC, Xavier D, Srinathan S, Guyatt G, Cruz P, Graham M, Wang CY, Berwanger O, Pearse RM, Biccard BM, Abraham V, Malaga G, Hillis GS, Rodseth RN, Cook D, Polanczyk CA, Szczeklik W, Sessler DI, Sheth T, Ackland GL, Leuwer M, Garg AX, Lemanach Y, Pettit S, Heels-Ansdell D, Luratibuse G, Walsh M, Sapsford R, Schunemann HJ, Kurz A, Thomas S, Mrkobrada M, Thabane L, Gerstein H, Paniagua P, Nagele P, Raina P, Yusuf S, Devereaux PJ, Devereaux PJ, Sessler DI, Walsh M, Guyatt G, McQueen MJ, Bhandari M, Cook D, Bosch J, Buckley N, Yusuf S, Chow CK, Hillis GS, Halliwell R, Li S, Lee VW, Mooney J, Polanczyk CA, Furtado MV, Berwanger O, Suzumura E, Santucci E, Leite K, Santo JA, Jardim CA, Cavalcanti AB, Guimaraes HP, Jacka MJ, Graham M, McAlister F, McMurtry S, Townsend D, Pannu N, Bagshaw S, Bessissow A, Bhandari M, Duceppe E, Eikelboom J, Ganame J, Hankinson J, Hill S, Jolly S, Lamy A, Ling E, Magloire P, Pare G, Reddy D, Szalay D, Tittley J, Weitz J, Whitlock R, Darvish-Kazim S, Debeer J, Kavsak P, Kearon C, Mizera R, O’Donnell M, McQueen M, Pinthus J, Ribas S, Simunovic M, Tandon V, Vanhelder T, Winemaker M, Gerstein H, McDonald S, O’Bryne P, Patel A, Paul J, Punthakee Z, Raymer K, Salehian O, Spencer F, Walter S, Worster A, Adili A, Clase C, Cook D, Crowther M, Douketis J, Gangji A, Jackson P, Lim W, Lovrics P, Mazzadi S, Orovan W, Rudkowski J, Soth M, Tiboni M, Acedillo R, Garg A, Hildebrand A, Lam N, Macneil D, Mrkobrada M, Roshanov PS, Srinathan SK, Ramsey C, John PS, Thorlacius L, Siddiqui FS, Grocott HP, McKay A, Lee TW, Amadeo R, Funk D, McDonald H, Zacharias J, Villar JC, Cortes OL, Chaparro MS, Vasquez S, Castaneda A, Ferreira S, Coriat P, Monneret D, Goarin JP, Esteve CI, Royer C, Daas G, Chan MT, Choi GY, Gin T, Lit LC, Xavier D, Sigamani A, Faruqui A, Dhanpal R, Almeida S, Cherian J, Furruqh S, Abraham V, Afzal L, George P, Mala S, Schunemann H, Muti P, Vizza E, Wang CY, Ong GS, Mansor M, Tan AS, Shariffuddin II, Vasanthan V, Hashim NH, Undok AW, Ki U, Lai HY, Ahmad WA, Razack AH, Malaga G, Valderrama-Victoria V, Loza-Herrera JD, De Los Angeles Lazo M, Rotta-Rotta A, Szczeklik W, Sokolowska B, Musial J, Gorka J, Iwaszczuk P, Kozka M, Chwala M, Raczek M, Mrowiecki T, Kaczmarek B, Biccard B, Cassimjee H, Gopalan D, Kisten T, Mugabi A, Naidoo P, Naidoo R, Rodseth R, Skinner D, Torborg A, Paniagua P, Urrutia G, Maestre ML, Santalo M, Gonzalez R, Font A, Martinez C, Pelaez X, De Antonio M, Villamor JM, Garcia JA, Ferre MJ, Popova E, Alonso-Coello P, Garutti I, Cruz P, Fernandez C, Palencia M, Diaz S, Del Castillo T, Varela A, de Miguel A, Munoz M, Pineiro P, Cusati G, Del Barrio M, Membrillo MJ, Orozco D, Reyes F, Sapsford RJ, Barth J, Scott J, Hall A, Howell S, Lobley M, Woods J, Howard S, Fletcher J, Dewhirst N, Williams C, Rushton A, Welters I, Leuwer M, Pearse R, Ackland G, Khan A, Niebrzegowska E, Benton S, Wragg A, Archbold A, Smith A, McAlees E, Ramballi C, Macdonald N, Januszewska M, Stephens R, Reyes A, Paredes LG, Sultan P, Cain D, Whittle J, Del Arroyo AG, Sessler DI, Kurz A, Sun Z, Finnegan PS, Egan C, Honar H, Shahinyan A, Panjasawatwong K, Fu AY, Wang S, Reineks E, Nagele P, Blood J, Kalin M, Gibson D, Wildes T, Vascular events In noncardiac Surgery patIents cOhort evaluatioN Writing Group oboTVeInSpceI, Appendix 1. The Vascular events In noncardiac Surgery patIents cOhort evaluatio NSIWG, Appendix 2. The Vascular events In noncardiac Surgery patIents cOhort evaluatio NOC, Vascular events In noncardiac Surgery patIents cOhort evaluatio NVSI. Myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: A large, international, prospective cohort study establishing diagnostic criteria, characteristics, predictors, and 30-day outcomes. Anesthesiology. 2014;120:564–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smilowitz NR, Redel-Traub G, Hausvater A, Armanious A, Nicholson J, Puelacher C, Berger JS. Myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiol Rev. 2019;27:267–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schoepfer H, Nestelberger T, Boeddinghaus J, Twerenbold R, Lopez-Ayala P, Koechlin L, Wussler D, Zimmermann T, Miro O, Martin-Sanchez JF, Christ M, Keller DI, Rubini Gimenez M, Mueller C, Investigators A. Effect of a proposed modification of the type 1 and type 2 myocardial infarction definition on incidence and prognosis. Circulation. 2020;142:2083–2085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nestelberger T, Boeddinghaus J, Badertscher P, Twerenbold R, Wildi K, Breitenbucher D, Sabti Z, Puelacher C, Rubini Gimenez M, Kozhuharov N, Strebel I, Sazgary L, Schneider D, Jann J, du Fay de Lavallaz J, Miro O, Martin-Sanchez FJ, Morawiec B, Kawecki D, Muzyk P, Keller DI, Geigy N, Osswald S, Reichlin T, Mueller C, Investigators A. Effect of definition on incidence and prognosis of type 2 myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1558–1568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCarthy CP, Olshan DS, Rehman S, Jones-O’Connor M, Murphy S, Cohen JA, Singh A, Vaduganathan M, Januzzi JL Jr., Wasfy JH. Cardiologist evaluation of patients with type 2 myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2021;14:e007440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh A, Gupta A, DeFilippis EM, Qamar A, Biery DW, Almarzooq Z, Collins B, Fatima A, Jackson C, Galazka P, Ramsis M, Pipilas DC, Divakaran S, Cawley M, Hainer J, Klein J, Jarolim P, Nasir K, Januzzi JL, Di Carli MF, Bhatt DL, Blankstein R. Cardiovascular mortality after type 1 and type 2 myocardial infarction in young adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:1003–1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chapman AR, Shah ASV, Lee KK, Anand A, Francis O, Adamson P, McAllister DA, Strachan FE, Newby DE, Mills NL. Long-term outcomes in patients with type 2 myocardial infarction and myocardial injury. Circulation. 2018;137:1236–1245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.