Abstract

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has high recurrence rates after surgery, however, there is no standard of care neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapies. While immunotherapy improved survival in advanced HCC, the aim of this study was to evaluate perioperative immunotherapy in resectable HCC.

Methods

In this phase 2 randomised, open-label study, patients with resectable HCC were assigned to receive 240 mg of nivolumab intravenously (IV) every 2 weeks alone or 480 mg of nivolumab IV every 4 weeks plus 1 mg/kg of ipilimumab IV every 6 weeks up to 4 doses before and after surgery. Patients were randomised to the treatment arms using blocked randomisation with a random block size. The primary endpoint was the safety and tolerability. Secondary and exploratory endpoints included overall response rate; pathological, and immunological correlates of response. An intention-to-treat analysis was used for data analysis. ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT03222076.

Findings

13/27 randomised patients were treated with nivolumab and 14/27 with nivolumab+ipilimumab. Grade 3 adverse events(AEs) were higher with combination treatment (43%, 6/14 patients) than with monotherapy (23%, 3/13 patients). The most common trAEs were elevated alanine aminotransferase, elevated aspartate aminotransferase, anemia, constipation, fatigue, hypothyroidism, elevated lipase, nausea, decreased platelet count, pruritis and maculo-papular rash. 7/27 patients had surgical cancellations, but not due to treatment-related AEs. Therefore, the study met the primary endpoint of safety and tolerability. 6/20 resected patients (33%; 3 in each arm) achieved major pathological response (MPR=100% necrosis(complete response, CR)+ >60% necrosis). 5/6 MPR patients achieved CR. After median follow-up of 24.6 months (95% CI:21.6,34.1), no recurrence was observed in patients with MPR, while 7/14 patients without MPR developed recurrence.

Interpretation

Our study showed that perioperative nivolumab and nivolumab+ipilimumab is safe and feasible in patients with resectable HCC. The study regimens induced MPR, which was accompanied by no recurrence. Our clinical and immune correlative findings support further studies of immunotherapy in the perioperative setting in HCC.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary liver cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortality in the world.(1) Around 15% of hepatocellular carcinomas are diagnosed at an early stage and are amenable to potentially curative treatments, such as surgical resection and liver transplantation.(2) However, no approved neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapies exist, despite the high 5-year tumor recurrence rate following surgical resection, of up to70%.(3–5)

Immune checkpoint therapy (ICT) with the blockade of the PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 pathways has been shown to improve clinical outcomes in advanced HCC and has been approved for systemic treatment.(6–11) ICT has not been studied in early-stage HCC, but it was shown to be feasible in non-small cell lung cancer, early-stage melanoma, early-stage mismatch repair–deficient colon cancer, and bladder cancer.(12–19) These studies also demonstrated that patients who achieved major pathological response (MPR) with ICT had superior survival outcomes in the postoperative period.

We hypothesized that anti-PD1 antibody (nivolumab) alone or in combination with anti-CTLA-4 antibody (ipilimumab) can be safely administered and may induce augmented immunological and clinical responses in patients with resectable HCC. We performed a phase 2 study to test our hypothesis.

Methods

Study design and participants

This is an investigator-initiated, single-center, phase 2 randomised, open-label study. Patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive nivolumab alone (Arm A) or nivolumab+ipilimumab (Arm B) before and after partial hepatectomy.

Initially, this study also included a third arm in which patients with unresectable localized HCC were to receive nivolumab+ipilimumab. This arm of the study was different from Arm B based on the enrollment of patients with unresectable localized HCC. The goal of this arm was to study if unresectable localized disease will have adequate tumor shrinkage to become resectable. However, the study was amended in June 2019 to remove Arm C due to lack of accrual.

Key inclusion criteria were ≥18 years and having resectable HCC, with the diagnosis confirmed by histology or clinical features, measurable disease defined by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, version 1.1 (RECIST 1.1). Additional inclusion criteria were Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status 0–1, adequate liver, kidney and marrow function. Patients who received prior local or systemic treatment were allowed, except for anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 therapy. Key exclusion criteria included Child-Pugh score B/C. The complete list of eligibility criteria is provided in the trial protocol, available in the supplementary materials.

This study was approved by the institutional review board at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC2017-0097, NCT03222076) and was supported by Bristol-Myers-Squibb. The study was conducted according to Good Clinical Practice guidelines, defined by the International Conference on Harmonisation, and Declaration of Helsinki principles. All the patients provided written informed consent.

Randomisation and masking

Patients were randomly assigned (1:1) using blocked randomisation with a random block size to receive nivolumab alone (Arm A) or nivolumab+ipilimumab (Arm B) before and after partial hepatectomy. No masking was applied to clinical outcome assessors.

Procedures

Patients assigned to Arm A received 240 mg of nivolumab intravenously (IV) every 2 weeks, for a total of 3 doses prior to liver resection in week 6. In the adjuvant setting, starting 4 weeks after surgery, patients received 480 mg of nivolumab IV every 4 weeks for up to 2 years or until disease progression or intolerable toxicity. Patients assigned to Arm B, patients received 1 dose of concurrent ipilimumab (1mg/kg) IV with the first preoperative nivolumab treatment and up to 4 doses of ipilimumab (1mg/kg) IV every 6 weeks postoperatively in the adjuvant setting (Figure 1, appendix p 1).

All patients underwent pretreatment biopsy and tumor staging with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with elastography at baseline and at week 6 before surgery. The resectability status was defined by a multidisciplinary liver tumor board. Restaging scans were performed 6 weeks after initiation of therapy and post-operatively every 12 weeks for two years and every 24 weeks for 3 additional years.

Resected primary tumors were assessed for percentage necrosis at the largest dimension of the tumor section on routine hematoxylin and eosin staining by two independent pathologists. Additionally, we used mass cytometry by time-of-flight (CyTOF), immunohistochemistry (IHC), and NanoString nCounter gene expression profiling on baseline and post-treatment tumor samples to study the immunological correlates of response (See Supplementary Appendix).

Outcomes

The primary objective of the study was to evaluate the safety and tolerability of presurgical nivolumab with/without ipilimumab. Secondary endpoints were overall response proportion (ORR) and progression-free survival (PFS). Exploratory endpoints included pathological, immunological, and other biomarker correlates of response. No masking was applied to clinical outcome assessors. Notably, immune profiling experiments was done with no access to clinical outcome data. However, at time of analysis the clinical outcomes were shared to analyze the data.

Measurements of safety included proportion of adverse events (AEs), serious AEs (grades≥3), and laboratory abnormalities. AEs were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for AEs, version 4.0. Meeting the primary endpoint was predefined as having at least 13 of 15 subjects receive their assigned therapy without grades≥3 adverse events necessitating delay in the surgical resection. ORR was defined as the number of subjects with complete response or partial response after 6 weeks of therapy by RECIST 1.1 criteria divided by the number of randomised patients. PFS was defined as the time from the start of treatment to the date of progressive disease, recurrence, or death, whichever occurred first. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from the start of treatment to death. Post-hoc analysis was performed to calculate recurrence-free survival (RFS), defined as the time from surgery to the date of recurrent disease or death, whichever occurred first.

Statistical Analysis

We made the determination that the proposed treatment would not be regarded as safe if more than 2 of 15 patients in each group had a surgery delay due to grade 3 or higher adverse events. Enrollment was discontinued once 30 patients were enrolled. Since no effective treatments are available in the perioperative setting, an ORR of 15% was predefined as an acceptable clinical benefit, based on studies reported at the time of study design(20),(21). Response proportions for ORR and MPR were estimated along with 95% exact confidence intervals (95% CIs). Survival analyses with the Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test were performed to assess various time-to-event end points. Categorical and continuous patient characteristics between patients who achieved major pathologic response (MPR) and non-MPR patients were compared using Fisher’s exact test or Wilcoxon rank sum test, respectively. Reported P values were two-sided and should be considered as exploratory; we regard estimates and confidence intervals as more relevant for clinical decision making. An intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis was used for data analysis. Statistical analyses performed for immune monitoring studies are described in Supplementary Appendix. This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03222076.

Role of the Funding Source

The funder of the study (NCI and BMS) did not participate in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing of the report.

Results

From October 2017 through December 2019, 30 patients provided consent enrolled. Of these patients, 2 withdrew consent and 1 developed progressive disease that was deemed unresectable before randomisation (Figure S1, appendix p 1). Twenty-seven patients were randomised, 13 to nivolumab, and 14 to nivolumab+ipilimumab arm. Baseline characteristics were well balanced between the groups (Table 1). The median age for the cohort was 64 years (IQR: 53, 69), and the majority of patients were males. Half of the patients had history of viral hepatitis. One patient in the nivolumab arm had Y90 treatment and was found to have residual disease confirmed by biopsy prior to study enrollment. Four patients (3 in nivolumab, 1 in nivolumab+ipilimumab arm) had prior liver resection and enrolled in the study with recurrent disease in the liver.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Patients Who Underwent Randomization*.

| Median age (IQR) — yr | 64 (56 – 68) | 62 (53 – 72) |

| Sex — no. (%) | ||

| Male | 11 (85) | 8 (57) |

| Ethnicity — no. (%) | ||

| African-American | 3 (23) | 4 (29) |

| Asian | 4 (31) | 3 (21) |

| White | 6 (46) | 7 (50) |

| ECOG PS — no. (%) | ||

| 0 | 9 (69) | 10 (71) |

| Child-Pugh score — no. (%) | ||

| A5 | 13 (100) | 13 (93) |

| Viral hepatitis — no. (%) | ||

| Hepatitis B | 4 (31) | 3 (21) |

| Hepatitis C | 3 (23) | 4 (29) |

| Non-viral ¶ | 6 (46) | 7 (50) |

| Alpha-fetoprotein — no. (%) | ||

| ≥400 ng/mL | 7 (54) | 2 (14) |

| Serum IGF — no. (%) | ||

| >50 ng/mL | 12 (92) | 13 (93) |

| IGF-CTP score — no. (%) ∥ | ||

| A4 | 12 (92) | 13 (93) |

| Fibrosis score — no./total no. (%) ~ | ||

| 0 | 7/12 (58) | 11/13 (85) |

| 1 – 2 | 3/12 (25) | 0/13 (0) |

| 3 | 1/12 (8) | 2/13 (15) |

| 4 | 1/12 (8) | 0/13 (0) |

| Tumor differentiation — no. (%) | ||

| Well | 4/11 (36) | 5/13 (38) |

| Moderate | 5/11 (45) | 5/13 (38) |

| Poor | 2/11 (18) | 3/13 (23) |

| Tumor nodularity — no. (%) | ||

| 1 | 10 (77) | 8 (57) |

| 2 | 3 (23) | 6 (43) |

| Baseline tumor size (range) - cm | 8.4 (1.6 – 11) | 5.5 (4.4–10.2) |

| Tumor size, sum — no. (%) | ||

| 1 – 5 cm | 4 (31) | 6 (43) |

| 5 – 10 cm | 5 (38) | 4 (29) |

| > 10 cm | 4 (31) | 4 (29) |

| Tumor size, sum mean (range) — cm | 7.5 (1.2 – 14.5) | 7.3 (1.5 – 18.6) |

| Prior treatment — no. (%) | ||

| Surgery | 3 (23) | 1 (7) |

| Y90 | 1 (8) | 0 (0) |

Percentages may not total 100 because of rounding.

Insulin-like Growth Factor 1-Child-Turcotte-Pugh (IGF-CTP) score was classified as either A (5–6 points), B (7–9 points), or C (>9 points). Classification was determined by scoring according to the presence and severity of four clinical measures of liver disease (bilirubin levels, albumin levels, prolonged prothrombin time, and IGF-1 levels).

Nonviral causes include alcohol, other, and unknown non-hepatitis B and C causes.

Fibrosis score was classified based on magnetic resonance imaging liver stiffness measurement scale: <2.5 kPa (normal), 2.5 to 2.93 kPa (normal or inflammation), 2.93 to 3.5 kPa (Stage 1–2 fibrosis), 3.5 to 4.0 (Stage 2–3 fibrosis), 4.0 to 5.0 kPa (Stage 3–4 fibrosis), and >5.0 kPa (Stage 4 fibrosis).

In total, 27 patients were randomised, and the study reached its primary end point of safety as at least 13 subjects were randomised to each group, and none were forced to delay surgery because of adverse events. Overall, 77% (10/13) of patients who received nivolumab and 86% (12/14) of patients who received nivolumab+ipilimumab had treatment-related adverse events (trAEs) at all grades (Table 2, Table S1, appendix p 8). Grade 3 trAEs were higher with nivolumab+ipilimumab treatment (43%, 6/14) compared with nivolumab alone (23%, 3/13) (difference =20%, 95% CI: −14.7%, 38.7%, Fisher’s exact test p value=0.69). The most common trAEs were elevated alanine aminotransferase, elevated aspartate aminotransferase, anemia, constipation, fatigue, hypothyroidism, elevated lipase, nausea, decreased platelet count, pruritis and maculo-papular rash. There were no surgical cancellations due to trAEs. Four patients in nivolumab and 3 patients in nivolumab+ipilimumab arm had cancellation of surgeries for other reasons (Figure S1 appendix p 1, Table S2, appendix p 9). All patients who had surgical cancellations were treated with standard-of-care local or systemic treatment options. One patient (Figure 2C, patient #6) had delayed surgery and deviation from protocol due to receiving 6 cycles of neoadjuvant nivolumab. The patient initially had 3 cycles of nivolumab treatment per the protocol and achieved partial response per RECIST 1.1. However, because of concern regarding a limited future liver remnant, it was recommended to continue 3 more cycles of nivolumab to achieve further decrease in tumor size. Subsequently, the patient also underwent right portal vein embolization to allow the residual left liver to hypertrophy. Later, the patient had successful hepatic resection without any complications.

Table 2.

Treatment-Related Adverse Events Occurring in 15% or More of Treated Patients in Either Group*.

| Event | Nivolumab (N=13) | Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab (N=14) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Patients (Percent) | ||||

| Any Grade | Grade 3/4 | Any Grade | Grade 3/4** | |

| All events | 10 (77) | 3 (23) | 12 (86) | 6 (43) |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 3 (23) | 1 (8) | 7 (50) | 4 (29) |

| Anemia | 2 (15) | 0 (0) | 3 (21) | 0 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 3 (23) | 1 (8) | 7 (50) | 4 (29) |

| Constipation | 2 (15) | 0 | 1 (7) | 0 |

| Fatigue | 1 (8) | 0 | 6 (43) | 0 |

| Hypothyroidism | 2 (15) | 0 | 2 (14) | 0 |

| Lipase increased | 2 (15) | 0 | 1 (7) | 0 |

| Nausea | 3 (23) | 0 | 3 (21) | 0 |

| Platelet count decreased | 2 (15) | 0 | 1 (7) | 0 |

| Pruritus | 2 (15) | 0 | 1 (7) | 0 |

| Rash maculo-papular | 4 (31) | 0 | 3 (21) | 0 |

Numbers represent the highest grades assigned.

1 patient treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab developed respiratory failure postoperatively requiring intubation, treated appropriately and recovered. This adverse event was considered as possibly related to the treatment.

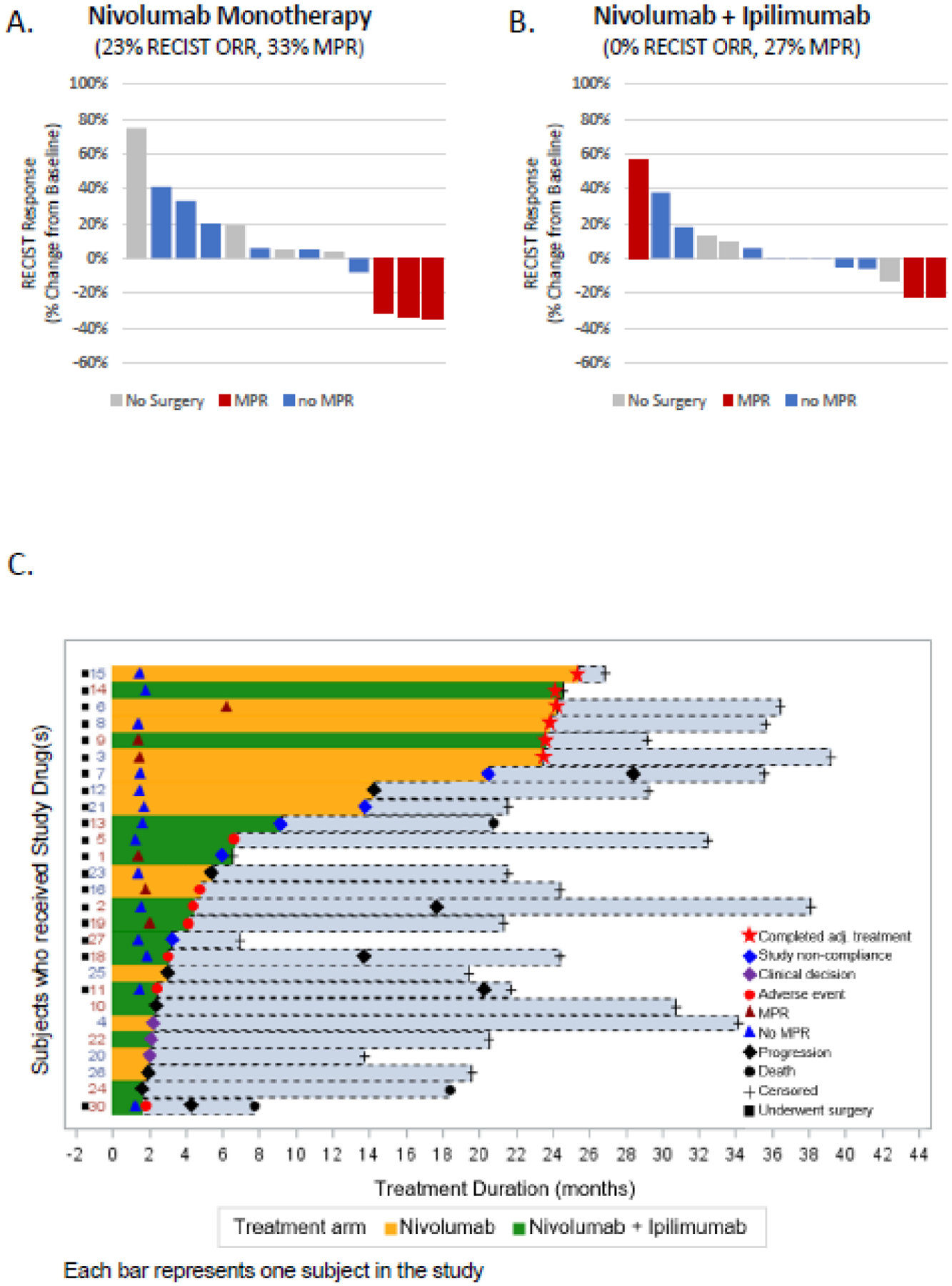

Figure 2.

Radiographic and Pathological Responses to Neoadjuvant Nivolumab and the Combination of Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab. Waterfall plots of ORRs by RECIST 1.1 at 6 weeks prior to the surgery and major pathological responses on resected tumors (panel A-B). Swimmer plot (panel C) shows the treatment duration and for patients who received study drug(s).

Representative radiologic and pathological responses after neoadjuvant treatment are shown in Supplementary Figure 2. Radiologic response was evaluated in 27 patients who underwent imaging at week 6. The ORRs at week 6, prior to the surgery, were 23% (3/13 patients, 95%CI:5%–53.8%) with nivolumab and 0% (0/14 patients, 95%CI:0%–23.2%) with nivolumab+ipilimumab. Pathological response was evaluated in 20 patients who underwent surgery in the study. MPR proportions were 33% (3/9 patients, 95%CI:7.5%–70.1%) with nivolumab and 27% (3/11 patients, 95%CI:6%−61%) with nivolumab+ipilimumab (Figure 2A–B). One patient had a complete pathological response despite the tumor enlargement observed on preoperative MRI of the abdomen, which was determined to be due to immune-cell infiltration (Figure S2B, appendix p 2).

Another secondary end point of the study was PFS. Two patients were not included in the PFS analysis because of their surgical cancellations unrelated to progressive disease (Figure 2C, patient #4, 22). 7/12 patients who received nivolumab and 7/13 patients who received nivolumab+ipilimumab had disease progression or death, whichever occurred first. The estimated median PFS was 9.4 months (95%CI,1.47-NE) for nivolumab compared to 19.53 months (95%CI,2.33-NE) for nivolumab+ipilimumab (HR=0.89 for nivolumab arm as reference, 95% CI: 0.31–2.54) (Figure 1A). The estimated 2-year PFS rates were 42% (95%CI,21–81%) for nivolumab and 31% (95%CI,11–88%) for nivolumab+ipilimumab (log-rank test P value=0.84).

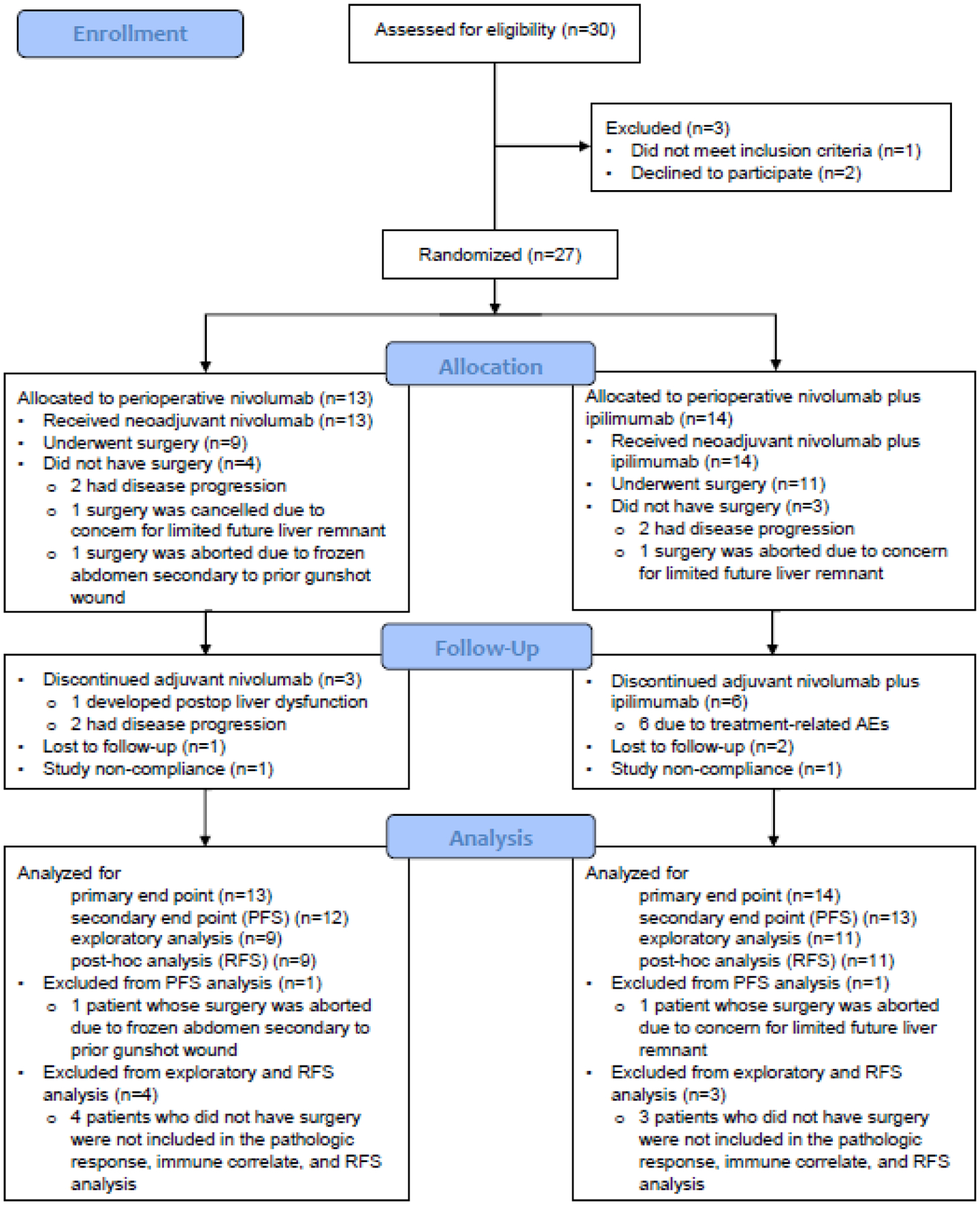

Figure 1.

Study CONSORT flow diagram.

During the median follow-up time of 24.6 months (IQR: 21.1–32.9), 3 patients in the nivolumab+ipilimumab arm died; 2 patients developed progressive disease prior to death, and the other patient was lost to follow-up prior to death, and therefore the cause of death is unknown (Figure S3, appendix p 3). No patients in the nivolumab arm died during the follow-up period.

Post-hoc RFS was evaluated in 20 patients who underwent surgery. The RFS was significantly improved in patients who achieved MPR compared to patients who did not achieve MPR, referred to as no MPR (non-MPR) (log-rank P=0.049) (Figure 3B). At the data cutoff of March 31, 2021, after median follow-up of 26.8 months (95%CI,21.7–35.6), 7/14 patients who did not have MPR developed recurrence, but none of the patients who had MPR developed recurrence or died during the follow-up period. The follow-up time for patients who achieved MPR was ranging from 6 months to more than 36 months. More specifically, the follow-up time was about 6 months in one patient and more than 18 months in other 5 patients. The median RFS was 24.4 months (95% CI: 14.0, NE) in patients without MPR (log-rank P=0.049). Our exploratory analysis of clinical predictors of outcome and tumor parameters are listed in Table S3, appendix 10.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier Plots of Progression-Free Survival and Recurrence-Free Survival. Shown are Kaplan–Meier estimates of progression-free survival (panel A) and recurrence-free survival (panel B), according to RECIST 1.1. Stratified hazard ratios for progression or death are reported.. P<0.05 denotes significant differences. Tick marks indicate censored data. CI denotes confidence interval; NE, not evaluable.

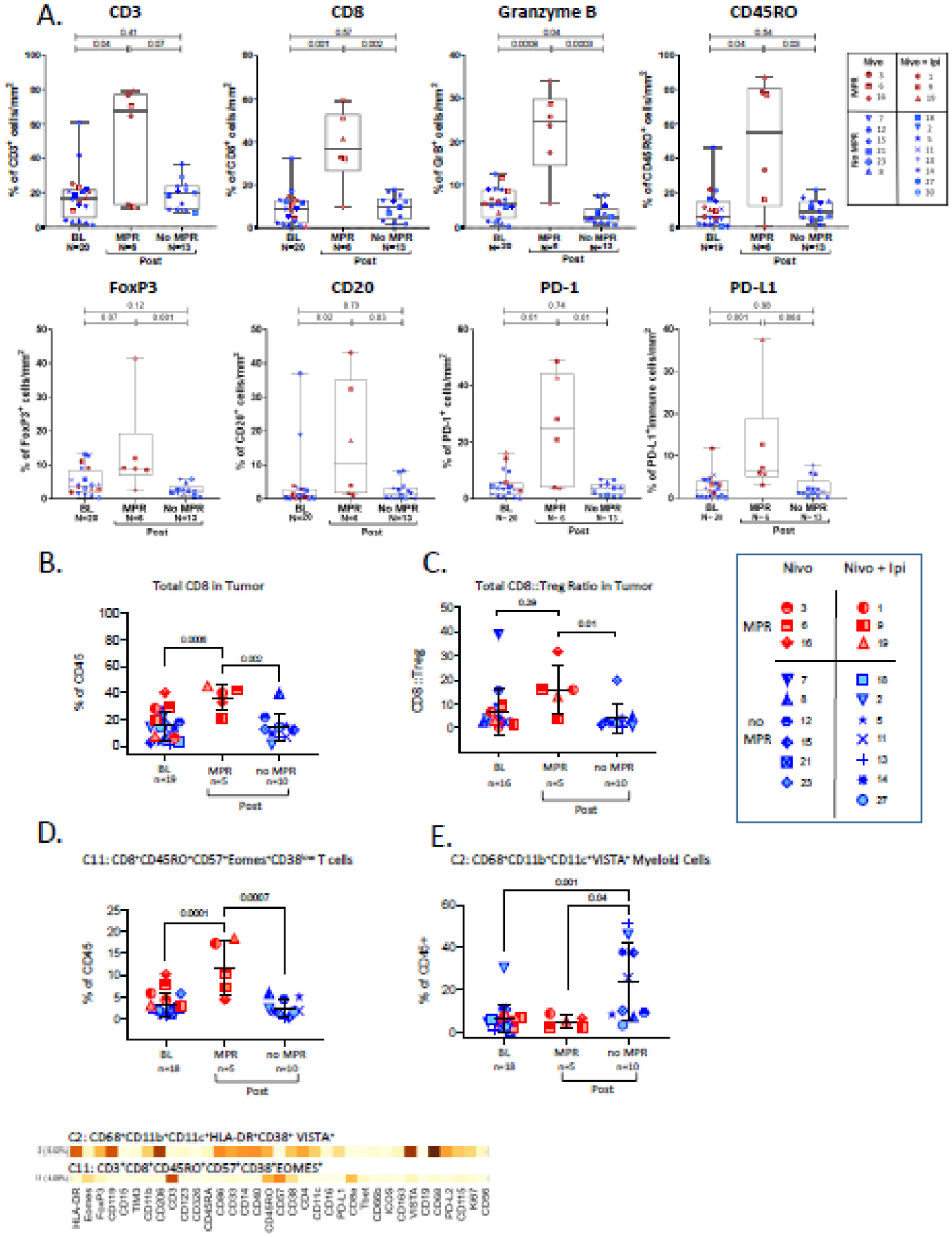

We analyzed pre and post-treatment tissue samples from MPR and non-MPR patients to explore the immune microenvironment associated with pathological responses. IHC analysis showed an increase in immune cell infiltration upon treatment with nivolumab±ipilimumab in patients with MPR (Figure 4A). A significant increase in the percentage of T cells (CD3+,CD8+,CD45RO+), Tregs (FOXP3+), B cells (CD20+), and immune cells expressing Granzyme B, PD-1, and PD-L1 was observed in post-treatment tissues of MPR patients compared to baseline (Figure 4A). MPR patients also showed a higher percentage of these cells in their post-treatment tissues compared to those of non-MPR patients (Figure 4A, Figure S4, appendix p 4). Similarly, CyTOF analysis showed a significant increase in CD8+ T cells in post-treatment tissues of MPR patients compared to baseline (Figure 4B). Post-treatment tissues of MPR patients had both a higher frequency of CD8+ T cells and a higher CD8-to-Treg ratio compared to post-treatment tissues of non-MPR patients (Figure 4B–C). No significant differences were observed in the frequency of Tregs between MPR and non-MPR patients (Figure S5, appendix p 5). To define the phenotype of tumor-infiltrating leukocytes (TILs), high-dimensional analysis of CyTOF data was performed and 33 different clusters of leukocyte subpopulations were identified (Figure S6, appendix p 6). We found two clusters which had opposite distribution patterns in MPR and non-MPR patients. In post-treatment tissues of MPR patients, an activated CD8+ effector T cell cluster (Cluster11:CD8+CD45RO+CD57+Eomes+CD38low) had both an increased frequency compared to baseline and and a higher frequency compared to post-treatment tissues of non-MPR patients (Figure 4D). While in post-treatment tissues of non-MPR patients, a CD68+ myeloid cluster expressing the immunosuppressive molecule VISTA (Cluster2:CD68+CD11b+CD11c+ VISTA+) was increased compared to baseline and also had a higher frequency compared to post-treatment tissues of MPR patients (Figure 4E). Overall, patients with resectable HCC who achieve MPR upon treatment with ICTs have a favorable tumor microenvironment (TME), while patients who do not achieve MPR have an immunosuppressive myeloid-rich TME.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry (A) and CYTOF analysis (B-E) of tissue samples. A. Immune cell density box plots with whiskers ranging from upper to lower quartiles. Categorical scatter plots showing frequency of B. CD8 T cells, C. CD8:Treg ratio, D. T cell cluster and, E. Myeloid cell cluster. Plots depict mean +/− SD.

Since nivolumab and ipilimumab have different modes of action, we interrogated if there were differences in immune responses to nivolumab versus nivolumab+ipilimumab. Gene expression analysis showed that baseline tissues of nivolumab treated MPR patients have higher expression of CD45 (p=0.004), total T (p=0.01), CD8 T (p=0.06), Th1 (p=0.002) and cytotoxic NK cell (p=0.03) markers compared to baseline tissues of non-MPR patients (Figure S7, top panel, appendix p 7). In contrast, post-treatment tissues of MPR patients who were treated with nivolumab+ipilimumab, showed an increase in infiltration with TILs (CD45, p=0.02; T cell, p=0.02, CD8 T cell, p=0.05, TH1, p=0.01, cytotoxic NK, p=0.002) compared to baseline while this increase was not observed in non-MPR patients (CD45, p=0.71; T cell, p=0.51, CD8 T cell, p=0.52, cytotoxic NK, p=0.44) (Figure S7, bottom panel, appendix p 7). No significant increase with TILs (CD45, p=0.59; T cell, p=0.31; CD8 T cell, p=0.33; TH1, p=0.39; cytotoxic NK, p=0.22) was observed in MPR/non-MPR patients who were treated with nivolumab alone (Figure S7, top panel, appendix p 7). Altogether, a higher infiltration with T cells at baseline is required for response to nivolumab monotherapy whereas responses to combination therapy does not have this requirement because addition of ipilimumab leads to favorable immunological changes in the TME.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first trial of perioperative ICT in patients with resectable HCC. Treatment with neoadjuvant nivolumab±ipilimumab was well tolerated, and trAEs did not cause cancellations or delays in surgery. Importantly, nivolumab and nivolumab+ipilimumab led to MPR proportions of 33% (3/9) and 27% (3/11), respectively, similar to other reported studies of neoadjuvant ICT in other cancers (Table S4, appendix p 11). Notably, the 6 patients who achieved MPR with neoadjuvant ICT did not have recurrence after a median follow-up of 26.8 months; in contrast, 7/14 non-MPR patients developed recurrence. Despite the small sample size, the RFS significantly differed between patients with vs. without MPR (P=0.049).

In this study the proportions of grade 3–4 trAEs with nivolumab and nivolumab+ipilimumab was 23% (3/13) and 43% (6/14), respectively, similar to previous reports. (7),6. Despite 9 (3 in nivolumab arm, and 6 in nivolumab+ipilimumab arm) patients having grade 3/4 adverse events, none of the patients had delay or cancellation in the surgery due to adverse events. Four patients in nivolumab and 3 patients in nivolumab+ipilimumab arm had cancellation of surgeries for other reasons, described in Table S2. Meeting the predefined primary end-point of safety and tolerability of both nivolumab and nivolumab+ipilimumab regimens in this study, supports further studies of investigating the efficacy.

Notably, ORR was observed in previous advanced HCC trials (nivolumab 14–20%, nivolumab+ipilimumab 27–32%)(6) after 2–2.7 months median time to response. In a recent phase 1b study of unresectable locally advanced HCC, cabozatinib and nivolumab combination enabled the resection of 12 patients, only one patient showed complete pathological response and additional 4 patients had major pathological response.(22) However, the combination included immunotherapy and tyrosine kinase inhibitor, cabozatinib. Furthermore, in the current neoadjuvant immunotherapy study of nivolumab±ipilimumab, we observed 5 complete pathological responses and 1 major pathological response of more than 70% necrosis. That is a 23% ORR (33% MPR) with nivolumab and a 0% ORR (27% MPR) with nivolumab+ipilimumab at 6 weeks. It is important to highlight in the nivolumab+ipilimumab treatment out of 3 patients who developed MPR, one had progressive disease and two had stable disease per RECIST criteria. Regarding the discrepancy between ORR and MPR in the nivolumab+ipilimumab arm, two patient who had stable disease per RECIST, can be explained by the short duration of therapy prior to surgery. Perhaps, those two patients who had stable disease, if continued therapy without surgery may eventually develop partial response per RECIST as indicated with the radiological tumor shrinkage and pathological necrosis. In fact, the median time for RECIST response in the CheckMate 040 study was 2–2.7 months as described above(6). For the third patient in the nivolumab+ipilimumab arm who had progressive disease but developed MPR, the discrepancy can be explained by the limitations of RECIST criteria being based on tumor size only without the consideration of tumor immune infiltration. As described in Figure S2B, that patient had immune infiltration which caused increased size of the radiological tumor measurement which was interpreted as progression per RECIST, however, developed MPR per pathological review. Nevertheless, MPR correlated with clinical outcome in our study. Based on this experience, we are encourage to include MPR as a predefined primary or secondary endpoint in future neoadjuvant ICB studies in HCC.

Correlative studies demonstrated several immune biomarkers of response to ICT. IHC analysis showed an increase in percentage of TILs after treatment with nivolumab±ipilimumab who achieved MPR. Additionally, in post-treatment tissues of patients who achieved MPR, CyTOF analysis showed an increase in an activated effector T cell cluster known to be essential in T cell–mediated antitumor immune response.(23, 24) These observations extend our previous findings from a case report of the first ever reported pathological responder to neoadjuvant immunotherapy from this trial. In this final report of the study, we also identified a VISTA+ myeloid cell cluster that was significantly increased in patients who did not achieve MPR, perhaps contributing to the immunosuppressive microenvironment,(25, 26) and provides a rationale for future trials targeting the VISTA in ICT-refractory HCC patients. Our data corroborate previous observations in other cancer types,(27–30) where responses to ICTs were associated with infiltration of immune cells and increase in the CD8+ T-cell/Treg ratio.(31) Consistent with previous studies,(12) NanoString analysis showed that pathological responses with nivolumab+ipilimumab combination therapy were less dependent on baseline TILs, likely due to known immune cell priming with anti–CTLA-4 inhibition.(32)

Limitations of our study include that it is a single-center study with a relatively small sample size and was not powered to formally compare clinical outcomes, pathological response, and immune correlates of nivolumab vs. nivolumab+ipilimumab. We note that group-specific 95% CIs assume simple random sampling of each treatment group from a hypothetical population of eligible patients, which may be quite unrealistic as in any trial(33). Additionally, there is possibility of selection bias and measurement bias due to loss to follow-up and non-compliance. However, despite these limitations, we observed complete pathological response in 5/20 patients and additional 1 patient with >50% pathological necrosis following neoadjuvant ICT. More importantly, patients with MPR did not have recurrences during a median 2-year follow-up. The findings in the correlative studies were consistent with previously known immune biomarkers of response and moreover generated new hypothesis for testing neoadjuvant nivolumab+ipilimumab in a larger future study. More specifically, as described in the Figure S7, patients who had MPR with nivolumab+ipilimumab had significantly increased immune infiltration when comparing baseline to post-treatment tumor. In contrast, patients who had MPR with nivolumab treatment already had high immune infiltration at baseline. This data suggests that despite having low immune infiltrates at baseline, with the immune priming ability of anti-CTLA4 treatment, nivolumab+ipilimumab, was able to generate MPR even in tumors which had low immune infiltration at baseline. However, nivolumab required high immune infiltration at baseline to generate MPR. Therefore, we chose nivolumab+ipilimumab for further studies, and developed Southwest Oncology Group study 2109, in which patients with resectable HCC will be randomised to receive neoadjuvant nivolumab+ipilimumab for 12 weeks vs. surgery alone. Based on the current immune profiling data, we anticipate that even patients with low baseline tumor immune infiltration may develop MPR with the addition of ipilimumab to the nivolumab treatment.

In conclusion, our findings provide the first evidence that neoadjuvant ICT is safe in patients with resectable HCC. Preliminary efficacy results suggests that patients treated with neoadjuvant ICT can achieve MPR with longer RFS. Combination therapy with nivolumab+ipilimumab warrants further studies in the preoperative setting for resectable HCC patients, which could transform the role of immunotherapy from palliative treatment in the metastatic setting to curative treatment in localized disease.

Supplementary Material

Research in Context.

Evidence before this study

We did a literature search using PubMed to identify perioperative immunotherapy trials in hepatocellular carcinoma on July 29, 2021. We used the search terms “neoadjuvant immunotherapy”, “perioperative immunotherapy”, and “hepatocellular carcinoma”. One study that we found was an illustrative case report of a patient that achieved a complete response of this study. Another study of nivolumab plus cabozatinib reported major pathological response in patients with unresectable HCC and ended up having successful surgery.

Added value of this study

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate peri-operative immune checkpoint blockage (nivolumab alone or nivolumab+ipilimumab) use in patients with resectable hepatocellular carcinoma. We found that the study regimen was safe and well tolerated which were the primary endpoint of the trial. Remarkably, the study regimen induced major pathological response (MPR) in 30% of resected patients which was accompanied by no recurrence in MPR group as compared to 50% recurrence rate in non-MPR group after a median follow up period of 24.6 months. Moreover, detailed immunologic correlative studies demonstrated several key immune biomarkers of response to immune checkpoint blockade. We identified that percentage of T cells, B cells, and CD8+ T-cell/Treg ratio in the tumor microenvironment increased in MPR compared to no MPR.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our results suggest that combination therapy with nivolumab±ipilimumab in the perioperative setting for resectable HCC patients was safe and induce pathological response. These findings have important implications for future clinical trial design and could improve outcomes for patients with resectable HCC.

Acknowledgements

Supported by Bristol Myers Squibb and by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute under award numbers P50 CA217674 (The MD Anderson Cancer Center Specialized Program of Research Excellence [SPORE] in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Grant) and P30CA016672 (Cancer Center Support Grant; used the Biostatistical Resource Group and Clinical Trials Office).

We thank the patients and their families for participating in this clinical trial. The Immunotherapy Platform performed immune monitoring assays of tumor samples. We thank Ashura Khan (Program Director), Marla Polk (Administrative Director) for logistic support and other members of Immunotherapy Platform at MD Anderson for their technical support and scientific input. We thank Sunita Patterson, Senior Scientific Editor, Research Medical Library, for editing this article.

Funding:

Funded by Bristol Myers Squibb and the National Institutes of Health;

Declaration of interests

A.O.K. reports consulting, advisory roles and/or stocks/ownership for Gilead Sciences, Bayer Health, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Exelixis, Merck; reports research funding to MD Anderson Cancer Center from Adaptimmune, Bayer/Onyx, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Hengrui Pharmaceutical, Hengrui Pharmaceutical, Merck; honoraria from Bayer Health, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Exelixis, Merck; other expenses from Bayer/Onyx, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Exelixis, Merck.

E.H. reports research funding to MD Anderson Cancer Center from Conquer Cancer Foundation, Kidney Cancer Association, and International Kidney Cancer Coalation.

K.P.S.R. reports research funding to MD Anderson Cancer Center from Bayer, Daiichi, AstraZeneca, Genentech, Guardant, Merck; consulting fees from Bayer, Daiichi, AstraZeneca; honoraria from Bayer, Daiichi.

R.S. reports consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim.

C.W.D.T reports consulting fees donated to MD Anderson Cancer Center from PanTher Therapeutics.

R.A.W. reports royalties/licenses from McGraw Hill for MD Anderson Manual of Medical Oncology, 3rd edition; travel support from Modern Medicine Emirates Oncology Society. J.C.Y. reports consulting fees from Hutchinson Medi Pharma, Ipsen Biopharmaceuticals Inc, Amgen, Chiasma Pharma, Crinetics Pharmaceuticals, Advanced Accelerator Applications International, Novartis Pharmaceuticals; leadership roles at North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society.P.S. reports consulting feesfrom Achelois, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Affini-T, Apricity, BioAtla, BioNTech, Candel Therapeutics, Catalio, Codiak, Constellation, Dragonfly, Earli, Enable Medicine, Glympse, Hummingbird, ImaginAb, Infinity Pharma, Jounce, JSL Health, Lava Therapeutics, Lytix, Marker, Oncolytics, PBM Capital, Phenomic AI, Polaris Pharma, Sporos, Time Bioventures, Trained Therapeutix, Two Bear Capital, Venn Biosciences; stocks/ownership for Achelois, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Affini-T, Apricity, BioAtla, BioNTech, Candel Therapeutics, Catalio, Codiak, Constellation, Dragonfly, Earli, Enable Medicine, Glympse, Hummingbird, ImaginAb, Infinity Pharma, Jounce, JSL Health, Lava Therapeutics, Lytix, Marker, Oncolytics, PBM Capital, Phenomic AI, Polaris Pharma, Sporos, Time Bioventures, Trained Therapeutix, Two Bear Capital, Venn Biosciences.

J.P.A. reports consulting fees from Achelois, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Apricity, BioAtla, BioNTech, Candel Therapeutics, Codiak, Dragonfly, Earli, Enable Medicine, Hummingbird, ImaginAb, Jounce, Lava Therapeutics, Lytix, Marker, PBM Capital, Phenomic AI, Polaris Pharma, Time Bioventures, Trained Therapeutix, Two Bear Capital, Venn Biosciences; stocks/ownership for Achelois, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Apricity, BioAtla, BioNTech, Candel Therapeutics, Codiak, Dragonfly, Earli, Enable Medicine, Hummingbird, ImaginAb, Jounce, Lava Therapeutics, Lytix, Marker, PBM Capital, Phenomic AI, Polaris Pharma, Time Bioventures, Trained Therapeutix, Two Bear Capital, Venn Biosciences. The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data sharing

De-identified individual data might be made available following publication. Investigators who wish to use the data for individual patient data can direct their proposal to the corresponding authors. Data will be made available via an appropriate data archive.

References

- 1.Yang JD, Hainaut P, Gores GJ, Amadou A, Plymoth A, Roberts LR. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(10):589–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chedid MF, Kruel CRP, Pinto MA, et al. Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Diagnosis and Operative Management. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2017;30(4):272–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Portolani N, Coniglio A, Ghidoni S, et al. Early and late recurrence after liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: prognostic and therapeutic implications. Ann Surg. 2006;243(2):229–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tabrizian P, Jibara G, Shrager B, Schwartz M, Roayaie S. Recurrence of hepatocellular cancer after resection: patterns, treatments, and prognosis. Ann Surg. 2015;261(5):947–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruix J, Takayama T, Mazzaferro V, et al. Adjuvant sorafenib for hepatocellular carcinoma after resection or ablation (STORM): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(13):1344–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10088):2492–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yau T, Park JW, Finn RS, et al. CheckMate 459: A randomized, multi-center phase III study of nivolumab (NIVO) vs sorafenib (SOR) as first-line (1L) treatment in patients (pts) with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (aHCC). Annals of Oncology. 2019;30:874-+. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):1894–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finn RS, Ryoo BY, Merle P, et al. Pembrolizumab As Second-Line Therapy in Patients With Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma in KEYNOTE-240: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase III Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(3):193-+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu AX, Finn RS, Edeline J, et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib (KEYNOTE-224): a non-randomised, open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncology. 2018;19(7):940–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yau T, Zagonel V, Santoro A, et al. Nivolumab (NIVO) plus ipilimumab (IPI) plus cabozantinib (CABO) combination therapy in patients (pts) with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (aHCC): Results from CheckMate 040. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(4). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amaria RN, Reddy SM, Tawbi HA, et al. Neoadjuvant immune checkpoint blockade in high-risk resectable melanoma. Nat Med. 2018;24(11):1649–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blank CU, Rozeman EA, Fanchi LF, et al. Neoadjuvant versus adjuvant ipilimumab plus nivolumab in macroscopic stage III melanoma. Nat Med. 2018;24(11):1655–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chalabi M, Fanchi LF, Dijkstra KK, et al. Neoadjuvant immunotherapy leads to pathological responses in MMR-proficient and MMR-deficient early-stage colon cancers. Nat Med. 2020;26(4):566–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Q, Wang C, Ma F, et al. Development and biological activity of long-acting recombinant human interferon-alpha2b. BMC Biotechnol. 2020;20(1):16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang AC, Orlowski RJ, Xu X, et al. A single dose of neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade predicts clinical outcomes in resectable melanoma. Nat Med. 2019;25(3):454–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Powles T, Kockx M, Rodriguez-Vida A, et al. Clinical efficacy and biomarker analysis of neoadjuvant atezolizumab in operable urothelial carcinoma in the ABACUS trial. Nat Med. 2019;25(11):1706–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forde PM, Chaft JE, Smith KN, et al. Neoadjuvant PD-1 Blockade in Resectable Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(21):1976–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cascone T, William WN Jr., Weissferdt A, et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab or nivolumab plus ipilimumab in operable non-small cell lung cancer: the phase 2 randomized NEOSTAR trial. Nat Med. 2021;27(3):504–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Khoueiry AB MI, Crocenzi TS, et al. Phase I/II safety and antitumor activity of nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): CA209–040. J Clin Oncol. 2015. (suppl; abstr LBA101).. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sangro BMI, Yau T, et al. Safety and antitumor activity of nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: interim analysis of dose-escalation cohorts from the phase 1/2 CheckMate 040 study. Presented at: 10th Annual International Liver Cancer Association Conference; September 9–11, 2016; Vancouver, Canada. Abstract O–019.. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho WJ, Zhu Q, Durham J, et al. Neoadjuvant cabozantinib and nivolumab convert locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma into resectable disease with enhanced antitumor immunity. Nature Cancer. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu Y, Ju S, Chen E, et al. T-bet and eomesodermin are required for T cell-mediated antitumor immune responses. J Immunol. 2010;185(6):3174–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu RC, Hwu P, Radvanyi LG. New insights on the role of CD8(+)CD57(+) T-cells in cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1(6):954–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blando J, Sharma A, Higa MG, et al. Comparison of immune infiltrates in melanoma and pancreatic cancer highlights VISTA as a potential target in pancreatic cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(5):1692–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao J, Ward JF, Pettaway CA, et al. VISTA is an inhibitory immune checkpoint that is increased after ipilimumab therapy in patients with prostate cancer. Nat Med. 2017;23(5):551–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen PL, Roh W, Reuben A, et al. Analysis of Immune Signatures in Longitudinal Tumor Samples Yields Insight into Biomarkers of Response and Mechanisms of Resistance to Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Cancer Discov. 2016;6(8):827–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tumeh PC, Harview CL, Yearley JH, et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature. 2014;515(7528):568–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barry KC, Hsu J, Broz ML, et al. A natural killer-dendritic cell axis defines checkpoint therapy-responsive tumor microenvironments. Nat Med. 2018;24(8):1178–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sivori S, Vacca P, Del Zotto G, Munari E, Mingari MC, Moretta L. Human NK cells: surface receptors, inhibitory checkpoints, and translational applications. Cell Mol Immunol. 2019;16(5):430–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tu JF, Ding YH, Ying XH, et al. Regulatory T cells, especially ICOS(+) FOXP3(+) regulatory T cells, are increased in the hepatocellular carcinoma microenvironment and predict reduced survival. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wei SC, Duffy CR, Allison JP. Fundamental Mechanisms of Immune Checkpoint Blockade Therapy. Cancer Discov. 2018;8(9):1069–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Senn SS. Statistical issues in drug development: John Wiley & Sons; 2008. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

De-identified individual data might be made available following publication. Investigators who wish to use the data for individual patient data can direct their proposal to the corresponding authors. Data will be made available via an appropriate data archive.