Abstract

Objectives:

Mexican Americans live longer on average than other ethnic groups, but often with protracted cognitive and physical disability. Little is known, however, about the role of cognitive decline for transitions in instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) disability and tertiary outcomes of the IADL disablement for the oldest old (after 80 years old).

Methods

We employ the Hispanic Established Populations for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly (2010–2011, 2012–2013, and 2016, N = 1,078) to investigate the longitudinal patterns of IADL decline using latent transition analysis.

Results

Three IADL groups were identified: independent (developing mobility limitations), emerging dependence (limited mobility and community activities), and dependent (limited mobility and household and community activities). Declines in cognitive function were a consistent predictor of greater IADL disablement, and loneliness was a particularly salient distal outcome for emerging dependence.

Discussion

These results highlight the social consequences of cognitive decline and dependency as well as underscore important areas of intervention at each stage of the disablement process.

Keywords: instrumental activities of daily living, functional disability, dementia, cognitive impairment, latent transition analysis

Introduction

After the age of 80, individuals face an increased risk of physical and cognitive decline and a growing need for support. By age 90, 68.2% of men and 82.2% of women in the United States experience difficulties with some aspect of physical and cognitive functioning (Berlau et al., 2009). Although modern medicine and an improved quality of life have increased life spans for all groups, it has been less successful in compressing morbidity; increased longevity may result in protracted periods of disability and dependency (Angel & Angel, 2021; Angel et al., 2014). Studies of such disability and dependency often rely on self-reports or proxy reports of limitations measured by limitations in basic activities of daily living (ADLs) or instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs); (Lawton & Brody, 1969; Nagi, 1976; World Health Organization, 2007). The former include walking, bathing, dressing, and feeding oneself (Jekel et al., 2015). Such measures directly reflect physical capacity. Problems with IADLs such as shopping, managing money, driving, and obtaining transportation reflect higher-order cognition as well as social capacities and opportunities along with basic physical functioning (Jekel et al., 2015). IADL disability is a correlate of executive functioning. Complex IADLs require higher neuropsychological functioning and, therefore, are more sensitive to cognitive impairment.

In this article, we examine patterns of decline in IADLs among the oldest-old Mexican Americans, a group at high risk of living for long periods with disability, using two waves of the Hispanic Established Population for the Epidemiological Study of the Elderly (Hispanic EPESE). The study contributes to the existing literature by (a) focusing on IADLs since many studies on disability in the Mexican-origin population focus on ADLs, (b) using longitudinal data to examine precursors of serious IADL disability in order to identify social and demographic profiles for elevated risk and dependency on others, and (c) responding to calls for research that focuses on long-term consequences of disability such as quality of life, including loneliness, depression, and self-rated health (Peek et al., 2005; Verbrugge & Jette, 1994). The use of latent transition analysis (LTA) allows for the examination of subdomains of IADL impairment instead of focusing on a composite score, as the majority of past research has done. The results will have significant implications for a number of areas of the literature as well as policy interventions.

The Social Aspects of IADL Impairment

The disablement process refers to the impact of disease/pathology on impairments, the functional limitations of disability, and the extent to which decline is associated with the external support of an individual’s social network and physical environment (Nagi, 1976; Verbrugge & Jette, 1994; World Health Organization, 2007). IADLs are affected by social and cultural factors that might place older Mexican Americans at particularly high risk of dependency on family and social programs (Carmona-Torres et al., 2019; Garcia & Reyes, 2018; Kelley-Moore & Ferraro, 2004).

Previous studies highlight the role of sociodemographic risk factors, such as gender and nativity status, in affecting IADL disability risk in the Mexican-origin population. For example, a study of a nationally representative sample of US adults found that men are more likely than women to not engage in household related IADL activities for reasons unrelated to health limitations, while women show greater levels of health-related limitations in IADLs than men (Sheehan & Tucker-Drob, 2019). Specifically for Mexican American women, social and cultural factors may contribute to IADL-related problems or obstacles with driving and/or obtaining transportation (Garcia et al., 2015). Previous studies have found that immigrant Mexican American women were significantly disadvantaged in IADL disabilities, especially within the domains of using transportation, using the telephone, shopping, and performing heavy housework (Garcia et al., 2015; Garcia & Reyes, 2018). Many older Mexican-origin women never learned to drive and thus may have difficulty obtaining transportation even if they possess the requisite physical and cognitive capacity (Garcia et al., 2015).

Evidence also shows Mexican-origin immigrants in the US live longer than their US- born counterparts but with more functional limitations and serious impairments (Angel et al., 2014). The older Mexican-origin population reports more IADL limitations than non-Latino Whites, African Americans, and other Latino groups (Zsembik et al., 2000). Likewise, in a longitudinal study of both ADL and IADL impairment, Liang et al. (2010) found that Mexican American older adults have higher probabilities of poor health trajectories than non-Latino Whites. Both immigrant men and women spend a significantly greater fraction of later life with limitations in IADLs compared to the US-born, which may be largely associated with problems or obstacles with driving or obtaining transportation (Garcia et al., 2015). Yet, little emphasis has been placed on each specific domain of IADL and common processes or transitions in these limitations over time.

According to the disablement model, progression of IADL disabilities is also associated with needed support from an individual’s social network. IADL decline is significantly associated with depression (Kiyoshige et al., 2018). Fauth et al. (2012) examined the association between depressive symptoms and disability in the context of the disablement process and reported that depressive symptoms slightly increased with approaching disability, increased at onset of the disability, and declined in the post-disability phase. The results suggest that the transition into a disabled state may be the trigger for a rise in depressive symptoms. Results also revealed that lower social support was associated with more depressive symptoms, which suggest that the lack of social resources and the resultant feeling of loneliness may serve as risk factors for disablement. Furthermore, a dual trajectory analysis of perceived social support and dementia for older Mexican Americans found that living alone was a marker of inadequate social support in the context of the disablement model (Rote et al., 2020).

Longitudinal and Latent Patterns of IADL

Recent studies on older adults have explored the trajectories of ADLs and IADLs using person-centered approaches (Han et al., 2013; Liang et al., 2010; Rote et al., 2020). Studies that have examined the longitudinal patterns of IADLs have found trajectories of IADL ability fall along a continuum of functioning and limitations, from healthy functioning or moderate limitations to large functional decrements or frailty groups (Liang et al., 2010; Wolf et al., 2015). However, these longitudinal studies include IADLs as a composite score rather than as individual domains, which makes it difficult to capture the multidimensionality of the IADL disabilities. The results of a cross-sectional study examining heterogeneity in the individual domains of the IADL disabilities reveal some specific domains that characterize each subgroup, such as using the telephone, transportation, handling money, and housekeeping (Park & Lee, 2017).

Liang et al. (2010) demonstrated the utility of longitudinal studies of impairment, finding three trajectories using both ADLs and IADLs: healthy functioning, moderate functional decrement, and large functional decrement. A study using a latent class trajectory model of disablement uncovered three trajectories: gradually declining “frailty,” moderate decline, and rapid decline (Wolf et al., 2015). Results revealed women were at greater risk of spending more years with ADL limitations than men. Latino older adults and older adults with less than a high school education were at the greatest risk of belonging to the “frailty” trajectory.

A significant limitation in longitudinal studies is that they have focused on the composite score or total number of self-reported IADL disabilities. However, recent studies have started to examine its specific subdomains. Disability is not unidimensional, and different domains of IADL activities require different physical or cognitive skills (Ng et al., 2006). A study on functional limitations and cognitive impairment showed six IADLs (shopping for groceries, preparing meals, doing housework, doing laundry, taking medicine, and managing finances) to be associated with impairment in at least one of the cognitive domains (Kiosses & Alexopoulos, 2005). Furthermore, patients with MCI exhibited limitations in the IADL domains of managing finances, shopping, keeping appointments, driving, or using everyday technology (Jekel et al., 2015). To our knowledge, no research has incorporated both the individual domains of the IADL disabilities and examined its longitudinal transitions, as the current study does.

Few studies have examined IADL disability and dementia-related disablement processes. As dementia progresses, IADL disability can be examined to make better assessments of the number of older Latinos at risk of being left without adequate support (Rote et al., 2020). With this approach, we estimate at which point in the disablement process interventions are most needed.

Study Aims

The aims of the current study are as follows:

Estimate IADL transitions for older Mexican Americans over time.

Identify the social and health risk factors, including dementia, that characterize each latent class.

Examine the consequences of the progression of IADL disabilities for distal outcomes, including loneliness, depression, and self-rated health.

Methods

Data

We employ the HEPESE, a population-based longitudinal cohort study of Mexican Americans 65 years and older residing in the southwestern United States (Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, and California). The first wave, in 1993–94, involved 3,050 respondents interviewed in English or Spanish in their homes; subsequent waves have been gathered every 2 years. We use data from waves 7 (2010–2011), 8 (2012–2013), and 9 (2016), meaning that all respondents were at least 82. By wave 9, there were 1,126 individuals participating, but the final analytic sample consisted of 1,078 individuals after excluding for missing values. Differential loss to follow up showed that respondents in the wave 7 cohort were more likely to be women, non-married, and foreign-born compared to the baseline at wave 1 of 3,050 individuals.

Measures

Dependent Variables.

IADLs are defined as being unable to complete or needing help completing the following 10 activities: (1) using a telephone, (2) driving a car or traveling alone, (3) shopping for groceries/clothes, (4) preparing a meal, (5) performing light housework, (6) taking medication, (7) managing finances, (8) performing heavy housework, (9) climbing stairs, and (10) walking half a mile.

Independent and Control Variables.

The study included respondents’ gender as 1 = Female, 0 = Male. We incorporated Medicaid, an indicator of access to the healthcare safety net for low-income older adults, as a dichotomous variable. We coded nativity as 1 = Mexican-born, 0 = US-born. We included living arrangement in the analysis with 1 = living alone and 0 = living with others. We measured cognitive impairment through the Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE). For the cases where proxy was employed because the respondent was mentally incapacitated, we coded the missing values of MMSE as 0 if they were unable to answer questions due to memory impairment or dementia. Specifically, 131 individuals reported using proxies at wave 7 because the respondent was mentally incapacitated. Out of these 131, 46 were unable to answer the question, which we coded as 0. Cognitive impairment served as a dichotomous variable, coded as 1 if MMSE was within the range of 0–23 and 0 if MMSE was within the range of 24–30.

Distal (Outcome) Variables.

We use three variables from wave 9 to examine distal outcomes. Loneliness is defined using the three items based on the 20-item UCLA loneliness scale to measure one’s subjective feelings of loneliness and social isolation (Russell et al., 1980). The HEPESE data use a shortened version of the UCLA loneliness scale which is adapted for epidemiological studies, and the shorter scale has yielded comparable results to the full scale (Hughes et al., 2004). The three items included were “How often do you feel you lack companionship?” “How often do you feel left out?” and “How often do you feel isolated from others?” with responses coded as 1 = Hardly ever, 2 = Some of the time, and 3 = Often. A sum of the three variables resulted in a range of 3–9. We define loneliness as a binary variable, coded as 0 if the sum ranges from 3 to 5 and 1 if the sum ranges from 6 to 9. The HEPESE data use the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale to measure depressive symptoms, which gives a score ranging from 0 to 60. We used the total CES-D score from wave 9. Self-rated health was included as a binary variable, with responses to the question “How would you rate your overall health?” coded as 1 = Poor, Fair and 0 = Good, Excellent.

Analytic Strategy

To address our first objective, we use LTA to examine the dynamics of IADLs among the study sample. LTA is a longitudinal extension of latent class analysis. Employing LTA reveals unobserved heterogeneity of a population by classifying individuals according to similar item-response patterns, and the transition probabilities capture movement or transition between latent classes over time (Collins & Lanza, 2009). As additional objectives, LTA also allows for the inclusion of time-variant and time-invariant covariates, as well as distal outcome in the model.

First, we fit latent class models for wave 7 and 8, respectively. Latent class analysis identifies distinct subgroups (i.e., latent classes) according to the individual’s response patterns. Individuals with similar item-response probability are classified into the same latent class. In order to select the best fitting model with the optimal number of classes, we applied several fit information criteria: Akaike information criterion (AIC) (Akaike, 1987), Bayesian information criterion (BIC) (Schwarz, 1978), sample-size–adjusted Bayesian information criterion (aBIC) (Sclove, 1987), Lo-Mendell-Rubin–adjusted likelihood-ratio test (LMR-LRT) (Lo et al., 2001), parametric bootstrapped likelihood-ratio test (BLRT) (Peel & McLachlan, 2000), and entropy. Models with lower AIC, BIC, and aBIC values indicate a better model fit. The LMR-LRT and BLRT compare the fit of k class model with the k-1 class model. A significant p-value under .05 indicates the k-1 class model is a better fitting model than the k class model. An entropy value of .8 or higher indicates an adequate classification quality. In addition to the statistical fit information, we considered interpretability and class proportion in selecting the final optimal model.

Second, we combined the latent class results of wave 7 and 8 to estimate the transition probabilities, which provides information about the changes in latent classes over time. Within the combined model, we performed multinomial logistic regression to identify the significant predictors of the IADL latent class at each time point and transition. Finally, we included distal outcome variables to analyze the consequences of IADL disabilities progression. To predict a distal outcome from latent class membership, we separately estimated for each class the mean or proportion of distal outcomes and compared them to determine if there were any significant differences (Lanza et al., 2013). Specifically, we analyzed how loneliness, depressive symptoms, and self-rated health at wave 9 differed according to wave 8 latent classes.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics at wave 7. The results revealed that women accounted for 65% of the sample, and the average years of formal education was approximately 5 years. Almost 45% of respondents were born in Mexico, and the average age of the respondents was 85.9. The average age of arrival in the US was around 35 years old. Half of the respondents received Medicaid, one-third was currently married, and one-third lived alone. In terms of cognitive health, 60% of respondents exhibited cognitive impairment. The average score on the CES-D was 10.7, and about one-fourth reported feelings of loneliness and social isolation. About 67% of respondents rated their health as poor or fair.

Table 1.

Demographic and Health Characteristics of Participants at Baseline (Wave 7).

| Range | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 65% | .48 | |

| Education (highest grade completed) | 0–17 | 5.0 | 4.09 |

| Mexican-born | 45.% | .50 | |

| Age | 80–102 | 85.9 | 3.97 |

| Age at arrival in the United States. | 34.6 | 17.39 | |

| Medicaid | 50.% | .50 | |

| Married | 31.% | .46 | |

| MMSE | 61.% | .48 | |

| Living alone | 31.% | .46 | |

| Loneliness | 25.% | .34 | |

| Depressive symptoms (CES-D) | 0–60 | 10.7 | 9.20 |

| Self-rated health | 67.% | .47 |

Note. Averaged over 1,126 individuals.

Latent Class of IADL Disabilities at Each Wave

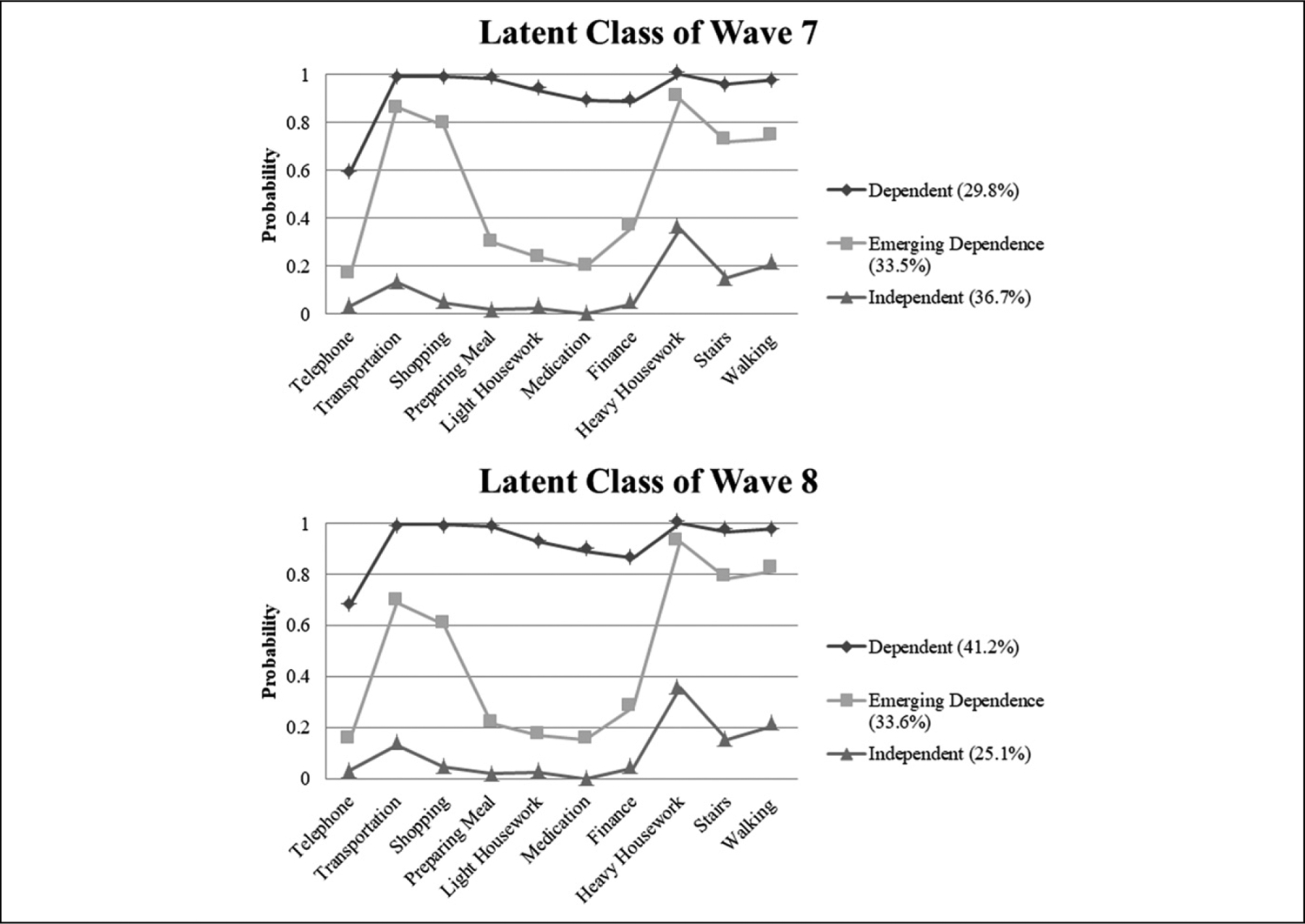

Latent class analysis of IADL disabilities at both waves 7 and 8 display three distinct classes as shown in Figure 1. Individuals with similar patterns of response probability regarding the 10 IADL items were classified into the same latent class. As the patterns of item-response probability were quite similar across both waves, model comparison of longitudinal measurement invariance was tested and achieved, implying that the structure of the three latent classes is the same at both waves 7 and 8. Under measurement invariance of item-response probability across time, the interpretation of the latent classes or the transitional probability becomes more straightforward.

Figure 1.

Latent Class of IADL Disabilities at Wave 7 and Wave 8 416 × 467 mm (47 × 47 DPI).

In Figure 1, the first class of wave 7, termed the “Independent” class, was characterized by an overall low need of assistance with all 10 items of IADL, as well as developing mobility limitations. This class represented about a third, 36.7% of the sample. The second class reported considerable limitations in transportation, mobility, heavy housework, and other limitations community activities, and thus was named the “Emerging Dependence” class. It was slightly smaller, at 33.5% of the sample. The third class, consisting of 29.8% of the sample, was termed “Dependent” as it showed an overall high dependence in most of the IADL items, including limitations in mobility, household, and community activities. Overall, wave 7 presented a relatively equal distribution of individuals in each class, with the largest percentage belonging to Independent, followed by Emerging Dependence, and then Dependent. By wave 8, however, the Independent class had shrunk to approximately 25% of the sample and 40% of the sample belonged to the Dependent class, while the Emerging Dependence class had stayed approximately the same size.

Ancillary analysis of descriptive statistics of each latent class revealed that more married people than people living alone or with other people than a partner were in the Independent class at both waves (Appendix A). At wave 7, a larger percentage of respondents living alone than living with others were in the Emerging Dependence class; women were also more likely to be in this class. The average age at migration was also highest for the Emerging Dependence class at both waves, closely followed by Dependent class. The Dependent classes at both waves had the oldest average age, least years of formal education, highest percentage of foreign-born respondents and respondents receiving Medicaid, and lowest average score on the MMSE.

Multinomial Logistic Regression

Table 2 shows the results of the multinomial logistic regression of both waves. Multinomial logistic regression pertaining to the wave 7 latent class variable revealed that cognitive impairment increased the probability of belonging to the Dependent class rather than the Independent or Emerging Dependence classes. Comparing Independent and Emerging Dependence classes showed that those with cognitive impairment were more likely to have IADL limitations in transportation and mobility. Those living alone were more likely to belong to Independent or Emerging Dependence classes, rather than to the Dependent class. Women were at greater risk of belonging to Dependent or to Emerging Dependence classes than to the Independent class. This may reflect low acculturation of Mexican-origin women and the problems they encounter with complex tasks such as driving or managing finances (Garcia et al., 2015). Older study participants receiving Medicaid were more likely to belong to the Dependent or Emerging Dependence classes than to the Independent class.

Table 2.

Multinomial Logistic Regressions Latent Class on Covariates at Wave 7 and Wave 8.

| Reference Group VS Comparing Group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Versus Dependent | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | ||

| Cognitive impairment | 6.90 | (3.22–14.75) | *** | 14.88 | (6.60–33.56) | *** |

| Living alone | .46 | (.23–0.91) | ** | .43 | (.19–0.98) | * |

| Married | .64 | (.34–1.22) | .95 | (.41–2.21) | ||

| Female | 2.77 | (1.47–5.21) | *** | .98 | (.45–2.12) | |

| Nativity (foreign-born) | 1.12 | (.66–1.89) | 1.04 | (.52–2.07) | ||

| Medicaid | 3.46 | (1.98–6.05) | *** | 1.44 | (.70–2.93) | |

| Independent versus Emerging Dependence | ||||||

| Cognitive impairment | 2.01 | (1.26–3.20) | *** | 4.43 | (2.28–8.61) | *** |

| Living alone | 1.29 | (.77–2.18) | .48 | (.22–1.04) | ||

| Married | .82 | (.46–1.46) | 1.23 | (.55–2.74) | ||

| Female | 2.83 | (1.72–4.66) | *** | 1.23 | (.58–2.58) | |

| Nativity (foreign-born) | 1.08 | (.68–1.71) | .83 | (.44–1.54) | ||

| Medicaid | 2.57 | (1.62–4.09) | *** | 1.77 | (.94–3.32) | |

| Emerging Dependence versus Dependent | ||||||

| Cognitive impairment | 3.43 | (1.56–7.53) | *** | 3.36 | (1.65–6.82) | *** |

| Living alone | .36 | (.18–0.69) | *** | .90 | (.46–1.75) | |

| Married | .78 | (.40–1.50) | .78 | (.39–1.54) | ||

| Female | .98 | (.50–1.90) | .80 | (.42–1.50) | ||

| Nativity (foreign-born) | 1.03 | (.62–1.74) | 1.26 | (.74–2.13) | ||

| Medicaid | 1.35 | (.76–2.39) | .81 | (.46–1.43) | ||

Note.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001.

Analysis of the relationship between the wave 8 latent class variable and its predictors revealed that cognitive impairment was a persistent, statistically significant risk factor of having more IADL disabilities. Much like at wave 7, older Mexicans living alone were more likely to belong to the Independent class than to the Dependent class.

Transition Probability

The estimation of transition probabilities provides information about the changes in latent classes over time. Table 3 shows the transition probability of the latent classes from wave 7 to wave 8. Transition probability based on the estimated model revealed that 95% of those belonging to the Dependent class at wave 7 also belonged to the Dependent class at wave 8. Over half (53%) of the individuals belonging to the Emerging Dependence class remained in the same class at wave 8, while 41% transferred to the Dependent class. For those belonging to the Independent class at wave 7, 54% remained in the same class, while 33% transferred to the Emerging Dependence class and 13% moved to the Dependent class. Overall patterns of transition revealed similar or increasing need for assistance regarding IADL among the oldest-old, with the class of Emerging Dependence acting as an intermediate phase between the other two classes.

Table 3.

Transition Probabilities of Latent Class from Wave 7 to Wave 8.

| Wave 8 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent, % | Emerging Dependence, % | Independent, % | ||

| Wave 7 | Dependent | 95 | 4 | 1 |

| Emerging Dependence | 41 | 53 | 6 | |

| Independent | 13 | 33 | 54 | |

Consequences of IADL Disabilities

We included distal outcome variables from wave 9 in the analysis to identify the consequences of the processes the latent transition model described. We independently estimated the mean or proportion of the distal outcome variables at wave 9, including loneliness, depressive symptoms, and poor to fair self-rated health, for each of the classes at wave 8. Results in Tables 4 and 5 revealed overall significant mean differences in the distal outcomes across latent classes. For loneliness, older Mexican Americans in the Emerging Dependence class reported a significantly higher level of loneliness compared to both the Dependent and Independent classes. However, the comparison between Independent and Dependent classes was not significant. For depressive symptoms and self-rated health, there was a similar pattern: older Mexican Americans in the Emerging Dependence and Dependent classes reported significantly higher levels of depressive symptoms and worse self-rated health compared to those in the Independent class. The difference between the Emerging Dependence class and Dependent class was not statistically significant for either depressive symptoms or self-rated health.

Table 4.

Analysis of Distal Outcome for Each Latent Class at Wave 8.

| Wave 9 Distal Outcome (Proportion/Mean) | Dependent | Emerging Dependence | Independent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loneliness | 12.1% | 29.2% | 11.7% |

| CES-D | 13.6 | 13.7 | 8.6 |

| Self-rated health | 74.4% | 75.2% | 52.3% |

Note. Self-rated health was coded as (1: poor, fair/0: good, excellent).

Table 5.

Wald Test for Distal Outcomes for Each Latent Class at Wave 8.

| Distal Outcome | Latent Class Comparison | Wald | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loneliness | Overall test | 10.76 | .01 |

| Dependent versus Emerging Dependence | 6.14 | .00 | |

| Emerging Dependence versus Independent | 10.05 | .01 | |

| Independent versus Dependent | .00 | .95 | |

| CES-D | Overall test | 25.54 | .00 |

| Dependent versus Emerging Dependence | .00 | .97 | |

| Emerging Dependence versus Independent | 18.63 | .00 | |

| Independent versus Dependent | 14.79 | .00 | |

| Self-rated health | Overall test | 17.17 | .00 |

| Dependent versus Emerging Dependence | .02 | .88 | |

| Emerging Dependence versus Independent | 13.65 | .00 | |

| Independent versus Dependent | 13.40 | .00 |

Conclusion

This study demonstrates longitudinal transition patterns of IADL disabilities and their association with cognitive impairment in the context of the disablement model for older Mexican Americans. This article contributes to the literature by examining the heterogeneity in longitudinal patterns of IADL disability and drawing unique classes of individuals with similar type of IADL disabilities. Results revealed three groups of IADL disability found in later stages of the life course: Independent (developing mobility limitations), Emerging Dependence (limited mobility and community activities), and Dependent (limited mobility and household and community activities). Notably, our findings uncovered the unique group of Emerging Dependence, characterized by considerable limitations in domains of transportation, shopping, and mobility (stairs and walking). This group is an important intermediary stage for older adults between Independent and Dependent in which they can still complete minor household tasks but are dependent on others for community activities such as transportation and shopping and mobility tasks. This unique group is often limited to the home and reliant on others for transportation, community activities, and heavy housework.

This study finds that more women than men were in the Emerging Dependence group. This aligns with previous studies, which have shown that the risk of disability while partaking in physical activities with household tasks, transportation, and shopping was highest in older adults and increased rapidly with age, with women in particular at greater risk of experiencing difficulty with traveling (Bleijenberg et al., 2017; Garcia et al., 2015). The fact that living alone correlates with the Emerging Dependence group partially aligns with past research. A previous study has found that living alone is a marker of inadequate support and possible dependence (Rote et al., 2020). The fact that the Independent group does not correlate with living alone may reflect cultural norms in Latino communities in which older adults typically live with their grown children regardless of health status at higher rates than non-Latino Whites. Future research should examine caregiving structures and availability of support to Mexican Americans in this Emerging dependence group in order to identify potential risk for unmet need.

Findings with respect to cognitive impairment align with past research in that it was associated with more IADL disabilities throughout both waves (Dodge et al., 2005; Jekel et al., 2015; Rajan et al., 2013). Cognitive impairment was also a consistent predictor of IADL disability transitions and led to more rapid disablement, especially in the progression from Emerging Dependence to Dependent. Previous literature has found that older adults with mild or minimal cognitive impairment are more likely to lose IADL independence compared to those with no impairments (Dodge et al., 2005) and that IADL restrictions in MCI predicted future dementia (Gold, 2012). As functional dependency predicts dementia and is accelerated by progression of cognitive impairment, this study aligns with past studies calling for identification of precursors and for early and timely interventions to older Mexican Americans living with mild cognitive impairment (Gallagher-Thompson et al., 2020).

This study also supports previous studies showing that multiple domains of cognitive impairment, especially domains of memory and executive function, predicted IADL dependence, with executive functioning being the strongest predictor (Mansbach & Mace, 2019). IADL domains of transportation and managing finances are closely associated with executive functions such as sequencing and inhibition, and these domains showed the largest discrepancy between those living with cognitive impairment and those living without impairment (Gold, 2012; Passler et al., 2020). Combined with previous literature, the findings of this study emphasize the need to carefully examine individual domains of both IADL disability and cognitive impairment and their associations. Tailored services should be provided to older Mexican Americans with disability in more complex tasks (e.g., financial and medication management and transportation) that require executive functioning.

In the context of the disablement model, the results of our study suggest early-stage impact of disability. According to the model, the progression of dementia results in cognitive impairment, which in turn has an impact on functional limitations and disabilities. In our findings, the patterns of transition revealed the tendency of the oldest-old Mexican Americans to either remain in the same class or progress toward higher dependency in IADLs. Previous literature has found that IADLs requiring physical functioning, such as transportation and heavy housework, develop earlier than those requiring mental functioning, such as managing finances and medication (Bleijenberg et al., 2017). In our study, the Emerging Dependence group served as an intermediate phase between the other two groups, implying that the transition to this group signifies the onset of IADL disability.

Our findings with respect to distal outcomes prompt future research on IADL independence and social support. Older Mexican Americans belonging to the Emerging Dependence group showed the highest levels of both loneliness and depressive symptoms. The results are consistent with previous studies that found loneliness is associated with functional limitations and disabilities and suggests the transition into a disabled state may be the trigger for a rise in depressive symptoms (Fauth et al., 2012; Shankar et al., 2017). Depressive symptoms are often associated with lower social support, and social support has a significant effect on moderate frailty, a middle “transition” between high and low frailty in older Mexican Americans (Peek et al., 2012). Altogether, the findings for the Emerging Dependence group indicate the timing of transitions in the disablement model for much-needed early intervention for both loneliness and depression, two factors which can further speed up disablement processes and increase risk for mortality. Future research should incorporate markers of family support for IADL tasks to determine linkages among dementia and disability for loneliness and depressive symptoms. Data linked to caregiver support structures and tasks will provide a better overview of support enacted for older Mexican Americans by their family caregivers throughout the disablement process and specific subpopulations that may be at risk for unmet support need.

Study Limitations

This study has certain limitations. We used a dichotomization of the loneliness outcome variable, which may not be representative of the true qualitative difference reflected in the loneliness scores. We used self-reported measures for functional disability. Additional information regarding objective reports of physical function and caregiver support structure and tasks is needed for a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the need for assistance and the state of dependency in this population of older adults. Future studies should also examine the longitudinal trajectories of household living arrangements. Although living alone was included as a time-varying covariate in the current study, the overall changing patterns of living arrangements and their associations with cognitive impairment should be considered. Finally, as the interest of the study was to examine dynamics of instrumental ADLs in the oldest-old HEPESE cohort, the results may not be generalized to the Mexican American population at younger-older ages. This study only includes those who are over 80 and have survived to waves 7, 8, and 9, and a possible attrition bias may be that those with the greatest limitations may be underrepresented in the results. Nevertheless, the findings of this study provide a better understanding of the development of functional disabilities in advanced ages for older Mexican Americans; in so doing, this study identifies an important subgroup in need of intervention for dementia- and disability-related support.

Our assessment of the longitudinal dynamics of IADL disabilities of the oldest-old Mexican Americans contributes to the literature by uncovering the unique, at-risk population of Emerging Dependence. Methodologically, this study in-corporates LTA in identifying changes in the pattern of IADL disabilities among the oldest-old Mexican Americans. Finally, this study provides meaningful implications regarding the risk and protective factors of functional limitations through the examination of time-varying covariates and distal outcomes.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by the National Institute on Aging grants [1R03AG063183-01] and [1R03AG059107-01].

Appendix

Table A1.

Ancillary analysis: Latent class characteristic at Wave 7

| Wave 7 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Living Alone, % | Female, % | Age | Married, % | Education* | Foreign-Born, % | Age at Migration | Medicaid, % | MMSE | |

| Independent | 26.0 | 50.5 | 84.3 | 43.9 | 6.4 | 40.0 | 32.3 | 36.1 | 24.1 |

| Emerging Dependence | 35.9 | 77.2 | 85.8 | 25.7 | 4.3 | 47.6 | 36.0 | 58.4 | 21.4 |

| Dependent | 21.2 | 74.4 | 86.9 | 29.4 | 4.1 | 54.4 | 35.9 | 68.5 | 16.3 |

Highest school grade completed.

Table 2A.

Ancillary analysis: Latent class characteristic at Wave 8.

| Wave 8 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Living Alone, % | Female, % | Age | Married, % | Education* | Foreign-Born, % | Age at Migration | Medicaid, % | MMSE | |

| Independent | 37.3 | 53.9 | 84.1 | 35.4 | 6.9 | 40.7 | 29.4 | 31.8 | 25.2 |

| Emerging Dependence | 28.7 | 66.1 | 84.9 | 32.2 | 5.1 | 41.9 | 36.4 | 52.0 | 21.7 |

| Dependent | 24.7 | 70.7 | 86.6 | 24.0 | 4.2 | 52.0 | 35.8 | 62.3 | 14.4 |

Highest school grade completed.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Akaike H (1987). Factor analysis and AIC. In: Selected papers of hirotugu akaike (pp. 371–386). Springer [Google Scholar]

- Angel RJ, & Angel JL (2021). Healthy life expectancy (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Angel RJ, Angel JL, & Hill TD (2014). Longer lives, sicker lives? Increased longevity and extended disability among mexican-origin elders. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70, 639–649. 10.1093/geronb/gbu158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlau DJ, Corrada MM, & Kawas C (2009). The prevalence of disability in the oldest-old is high and continues to increase with age: Findings from the 90+ study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 24(11), 1217–1225. 10.1002/gps.2248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleijenberg N, Zuithoff NPA, Smith AK, De Wit NJ, & Schuurmans MJ (2017). Disability in the individual ADL, IADL, and mobility among older adults: A prospective cohort study. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, 21(8), 897–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona-Torres JM, Rodríguez-Borrego MA, Laredo-Aguilera JA, López-Soto PJ, Santacruz-Salas E, & Cobo-Cuenca AI (2019). Disability for basic and instrumental activities of daily living in older individuals. Plos one, 14(7), e0220157. 10.1371/journal.pone.0220157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, & Lanza ST (2009). Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences (Vol. 718). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge HH, Kadowaki T, Hayakawa T, Yamakawa M, Sekikawa A, & Ueshima H (2005). Cognitive impairment as a strong predictor of incident disability in specific ADL-IADL tasks among community-dwelling elders: The Azuchi study. The Gerontologist, 45(2), 222–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauth EB, Gerstorf D, Ram N, & Malmberg B (2012). Changes in depressive symptoms in the context of disablement processes: Role of demographic characteristics, cognitive function, health, and social support. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67B(2), 167–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Thompson D, Choryan Bilbrey A, Apesoa-Varano EC, Ghatak R, Kim KK, & Cothran F (2020). Conceptual framework to guide intervention research across the trajectory of dementia caregiving. The Gerontologist, 60(Supplement_1), S29–S40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia MA, Angel JL, Angel RJ, Chiu C-T, & Melvin J (2015). Acculturation, gender, and active life expectancy in the Mexican-origin population. Journal of aging and health, 27(7), 1247–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia MA, & Reyes AM (2018). Prevalence and trends in morbidity and disability among older Mexican Americans in the Southwestern United States, 1993–2013. Research on Aging, 40(4), 311–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold DA (2012). An examination of instrumental activities of daily living assessment in older adults and mild cognitive impairment. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 34(1), 11–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han L, Allore H, Murphy T, Gill T, Peduzzi P, & Lin H (2013). Dynamics of functional aging based on latent-class trajectories of activities of daily living. Annals of Epidemiology, 23(2), 87–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, & Cacioppo JT (2004). A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys. Research on Aging, 26(6), 655–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jekel K, Damian M, Wattmo C, Hausner L, Bullock R, Connelly PJ, Dubois B, Eriksdotter M, Ewers M, Graessel E, Kramberger MG, Law E, Mecocci P, Molinuevo JL, Nygård L, Olde-Rikkert MG, Orgogozo J-M, Pasquier F, Peres K, Salmon E, & Frölich L (2015). Mild cognitive impairment and deficits in instrumental activities of daily living: a systematic review. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy, 7(1), 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley-Moore JA, & Ferraro KF (2004). The black/white disability gap: Persistent inequality in later life?. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 59(1), S34–S43. 10.1093/geronb/59.1.s34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiosses DN, & Alexopoulos GS (2005). IADL functions, cognitive deficits, and severity of depression: A preliminary study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 13(3), 244–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyoshige E, Kabayama M, Sugimoto K, Arai Y, Ishizaki T, Gondo Y, Rakugi H, & Kamide K (2018). Difference in association of depression with IADL decline between 70s and 80s age groups. Innovation in Aging, 2(suppl_1), 943. [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Tan X, & Bray BC (2013). Latent class analysis with distal outcomes: A flexible model-based approach. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 20(1), 1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, & Brody EM (1969). Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist, 9(3_Part_1), 179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J, Xu X, Bennett JM, Ye W, & Quiñones AR (2010). Ethnicity and changing functional health in middle and late life: A person-centered approach. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 65B(4), 470–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y, Mendell NR, & Rubin DB (2001). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika, 88(3), 767–778. [Google Scholar]

- Mansbach WE, & Mace RA (2019). Predicting functional dependence in mild cognitive impairment: Differential contributions of memory and executive functions. The Gerontologist, 59(5), 925–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagi SZ (1976). An epidemiology of disability among adults in the United States. In: The milbank memorial fund quarterly (Vol. 54, pp. 439–467). The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. Health and Society. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng T-P, Niti M, Chiam P-C, & Kua E-H (2006). Physical and cognitive domains of the instrumental activities of daily living: Validation in a multiethnic population of Asian older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 61(7), 726–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, & Lee YJ (2017). Patterns of instrumental activities of daily living and association with predictors among community-dwelling older women: A latent class analysis. BMC Geriatrics, 17(1), 158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passler JS, Kennedy RE, Clay OJ, Crowe M, Howard VJ, Cushman M, Unverzagt FW, & Wadley VG (2020). The relationship of longitudinal cognitive change to self-reported IADL in a general population. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition, 27(1), 125–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek MK, Howrey BT, Ternent RS, Ray LA, & Ottenbacher KJ (2012). Social support, stressors, and frailty among older Mexican American adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67(6), 755–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek MK, Patel KV, & Ottenbacher KJ (2005). Expanding the disablement process model among older Mexican Americans. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 60(3), 334–339. 10.1093/gerona/60.3.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peel D, & McLachlan GJ (2000). Robust mixture modelling using the t distribution. Statistics and Computing, 10(4), 339–348. [Google Scholar]

- Rajan KB, Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Mendes de Leon CF, & Evans DA (2013). Disability in basic and instrumental activities of daily living is associated with faster rate of decline in cognitive function of older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 68(5), 624–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rote SM, Angel JL, Kim J, & Markides KS (2020). Dual trajectories of dementia and social support in the Mexican-origin population. The Gerontologist, 61(3), 374–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D, Peplau LA, & Cutrona CE (1980). The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(3), 472–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz G (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics, 6(2), 461–464. [Google Scholar]

- Sclove SL (1987). Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika, 52(3), 333–343. [Google Scholar]

- Shankar A, McMunn A, Demakakos P, Hamer M, & Steptoe A (2017). Social isolation and loneliness: Prospective associations with functional status in older adults. Health psychology, 36(2), 179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan CM, & Tucker-Drob EM (2019). Gendered expectations distort male-female differences in instrumental activities of daily living in later adulthood. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 74(4), 715–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge LM, & Jette AM (1994). The disablement process. Social Science & Medicine, 38(1):1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf DA, Freedman VA, Ondrich JI, Seplaki CL, & Spillman BC (2015). Disability trajectories at the end of life: A “countdown” model. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70(5), 745–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2007). International classification of functioning, disability, and health: Children & youth version ICF-CY. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Zsembik BA, Peek MK, & Peek CW (2000). Race and ethnic variation in the disablement process. Journal of Aging and Health, 12(2), 229–249. 10.1177/089826430001200205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]