Abstract

Objectives

To understand the facilitators and barriers to hospice staff engagement of patients and surrogates in advance care planning (ACP) conversations.

Design

Qualitative study conducted with purposive sampling and semi-structured interviews using ATLAS.ti software to assist with template analysis.

Settings and participants

Participants included 51 hospice professionals (31 clinicians, 13 leaders, and 7 quality improvement administrators) from four geographically-distinct non-profit U.S. hospices serving over 2,700 people.

Measures

Interview domains were derived from the implementation science framework of Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, and Behavior (COM-B), with additional questions soliciting recommendations for behavior change. Differences in themes were reconciled by consensus. The facilitator, barrier, and recommendation themes were organized within the COM-B framework.

Results

Capability was facilitated by interdisciplinary teamwork and specified clinical staff roles and inhibited by lack of self-perceived skill in engaging in ACP conversations. Opportunities for ACP occurred during admission to hospice, acute changes, or deterioration in patient condition. Opportunity-related environmental barriers included time constraints such as short patient stay in hospice and workload expectations that prevented clinicians from spending more time with patients and families. Motivation to discuss ACP was facilitated by the employee’s goal of providing personalized, patient-centered care. Implicit assumptions about patients and families’ preferences reduced staff’s motivation to engage in ACP. Hospice staff made recommendations to improve ACP discussions, including training and modeling practice sessions, earlier introduction of ACP concepts by clinicians in pre-hospice settings, and increasing workforce diversity to reflect the patient populations the organizations want to reach and cultural competency.

Conclusions and implications

Even hospice staff can be uncomfortable discussing death and dying. Yet staff were able to identify what worked well. Solutions to increase behavior of ACP engagement included staff training and modeling practice sessions, introducing ACP prior to hospice, and increasing workforce diversity to improve cultural competency.

Keywords: Advance care planning, qualitative research, Health workforce, behavior change, implementation

Brief summary:

The primary contributions of our paper is documenting that barriers and facilitators to ACP engagement exist even in hospice. Our results identify teachable factors that could be implemented in other hospice organizations and further improve hospice ACP.

Advance care planning (ACP) involves more than a completed advance directive or a code status/life-sustaining treatment order. ACP is a process that supports patients in understanding and sharing their personal values, life goals, and preferences regarding future medical care through iterative discussions revisited regularly at any age or stage of life.1 Given that hospice organizations care for people nearing end-of-life, it may seem reasonable to assume that hospice staff and organizations are experts at ACP conversations and have the essential skills and knowledge to engage effectively in ACP. Yet, little research describes staff perceptions of how ACP conversations actually occur in hospice. Existing literature has examined facilitators and barriers to ACP conversations in the context of admissions to nursing home or hospital, and in the context of serious illness such as heart failure or end-stage liver disease,2–4 but not in hospice itself. We need to understand how ACP conversations occur in hospice in order to ensure goal-concordant care for patients at the end-of-life, and to identify opportunities for improvement.

Improving ACP engagement depends on behavior change. Thus, behavior change interventions are needed to increase and promote best practices. The COM-B model provides an overarching framework to identify facilitators/barriers that could be translated into behavior change interventions. COM-B includes three interacting components, Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation, to understand Behavior.5 Capability represents the individual’s psychological or physical capacity (e.g. knowledge or skills) to engage in a behavior. Opportunities include factors in the physical and social environment that prompt or make the behavior possible. Motivation reflects the way an individual is energized to engage in a specific behavior, including emotional responses, habitual or decision-making processes, and goals or beliefs. COM-B provides a lens through which to understand facilitators and barriers to engagement in ACP conversations and to identify targets for increasing engagement6 (i.e. behavior change).

Therefore, we designed a qualitative study to understand hospice clinician attitudes toward and practices of ACP in order to identify facilitators and barriers to ACP at time of admission to hospice and opportunities for improvement. This study addresses two research questions: How do hospice professionals identify facilitators and barriers to engaging hospice enrollees and families in ACP? What opportunities improve engagement in ACP conversations?

Methods

Design

This qualitative study was designed to address research questions involving staff attitudes and practices of ACP engagement in community-based hospice organizations7,8 See Appendix for additional information. Our Institutional Review Board determined the study to be exempt.

Settings and participants

Eligible sites included geographically diverse non-profit community-based hospices affiliated with the Palliative Care Research Cooperative (PCRC). Participants were purposively recruited from the hospice organizations and included hospice employees from various organizational roles and training backgrounds (interdisciplinary clinicians, executive leadership, quality improvement (QI) administrators).7

Measures

In-depth, face-to-face interviews were conducted by an experienced qualitative researcher (KH). All participants provided verbal consent. Interview domains drew from the Theory of Domains Framework9 and associated COM-B model5,10 to understand stakeholder perspectives. Semi-structured interview questions addressed: 1) capability, opportunity, and motivation to facilitate end-of-life care conversations; and 2) professional recommendations about opportunities to improve end-of-life care and conversations (see Appendix for interview framework).

Data analysis

Interviews were professionally transcribed and deidentified. Four authors (AO, NT, KM, KH) read the dataset in its entirety. NT and KM created within-site analytic summaries and AO created cross-site matrices.11 Data were interrogated using template analysis, a combination of deductive and inductive coding that allows for further adaptation and refinement of theory across different clinical contexts.12,13 KH/NT/KM deductively coded ACP practices and attitudes, while AO/KH deductively coded Capability, Opportunity and Motivation (both 10% double-coded). AO/KH then used inductive (open) coding to identify emerging subcategories within the COM-B framework when the subcategory did not fit the data (e.g. participants discussed physical capabilities of learned skills rather than physical strength or stamina). Other team members (TA/CR/RS) helped adjudicate coding discrepancies and refined subthemes. Differences were reconciled by discussion.

Results

Seventy-one staff members were recruited across four sites; 51 agreed to particípate. All sites had free-standing inpatient units, accepted full-code patients, and procedures to document patient/family preferences. Participants were evenly spread across sites, including 31 clinicians (48% nurses, 35% social workers (SW), 6% chaplains, 10% physicians), 13 leaders, and 7 QI administrators. Most participants were female and white; 12% of participants were people of color, 20% were male.7

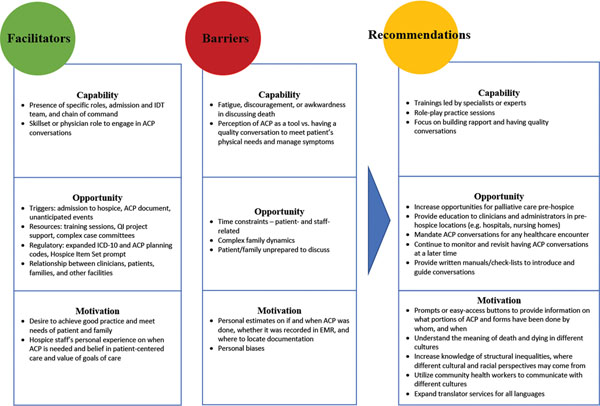

When asked to define ACP, 53% (n=27) of the participants defined ACP narrowly, including only completion of documentation or orders such as advance directives, proxy directive, or code status. The remainder defined ACP broadly as any conversation involving immediate or long-term goals of care (GOC), values, plans, or preferences. GOC conversations are only one aspect of ACP, yet these GOC conversations commonly co-occurred with ACP at hospice admission; many participants conflated the two terms. We have retained use of GOC in their quotes. Quotes included in this manuscript are identified by site, participant number, participant type, and credentials, e.g. s4_p44_clinician_MD. We present a summary of key findings regarding hospice and staff perspectives on facilitators and barriers to engaging patients and families in ACP (Figure 1) related to Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation (Table 1, 2) as well as staff recommendations for improvements to previously-identified barriers (Table 3).

Figure 1. Summary of COM-B model applied to identifying facilitators, barriers, and recommendations to advance care planning discussion with hospice patients and families from front-life staff perspectives.

Capability was facilitated by interdisciplinary teamwork and specified clinical staff roles and inhibited by lack of self-perceived skill in engaging in ACP conversations. Hospice staff recommended trainings and modeling practice sessions to improve staff capability for ACP. Opportunities for ACP occurred during admission to hospice, acute changes, or deterioration in patient condition. Opportunity-related environmental barriers included time constraints such as short patient stay in hospice and workload expectations that prevented clinicians from spending more time with patients and families. Hospice staff recommended introducing ACP concepts earlier in pre-hospice settings. Motivation to discuss ACP was facilitated by the employee’s goal of providing personalized, patient-centered care. Implicit assumptions about patients and families’ preferences reduced staffs motivation to engage in ACP. Hospice staff recommended increasing workforce diversity to reflect the patient populations the organizations want to reach and cultural competency.

Table 1.

Themes and quotes reflecting facilitators on capability, opportunity, and motivations in engaging patients and families in ACP conversations from hospice staff perspectives

| Theme | Illustrative quote or example |

|---|---|

| CAPABILITY FACILITATOR | |

| Presence of specific roles and interdisciplinary care and chain of command: admission team, nurse, SW, chaplain, physician | “I think the other part is I wouldn’t know how to really elicit well a spiritual care – goals of care. So am I able to delve in and figure that out? No, not as well as a spiritual care counselor can. And the same thing, you know, the social worker isn’t going to be able to establish the medical goals of care as well as a nurse or a doctor can.” (Site 3, Physician leader, male, [s3_p1_leader_MD) |

| Physician role or clinicians with unusually good ability or skill to explore fears, discuss values | “Now, do I think that there is a

lynchpin person who could open the conversation? The doctor. If the

doctor had the hutzpah, if the doctor had the comfort, if the doctor had

the financial incentives to do so that could probably make all of the

difference because us nurses, social workers, chaplains, we might be

able to get in a side door. But the front door of these conversations

really is the physician.” (Site 4, Nurse leader, female

[s4_p41_leader_RN]) “I don’t think you need to be a physician to have these conversations. I’ve worked with social workers, nurses, chaplains that are just as skilled as I am. I think sometimes you need the MD blessing on it.” (Site 2, Physician clinician, male, [s2-p32-clinician-MD]) |

| OPPORTUNITY FACILITATOR | |

| Triggers – admission to hospice: hospice eligibility determination, required screening and forms prior to admission (lack of advanced directive, full-code status) | “—staring at admission...if a patient comes on and, say they are full code, the social worker really makes a visit very quickly out there with the nurse to start the discussion. We’re not force-feeding it but we have to have the discussion with the family. And they say, ‘I’m just not ready for that,’ then that’s fine. We have to respect it, but we do need to revisit it.” (Site 2, Nurse leader, female [s2-p29-leader-RN]) |

| Availability of ACP document | “when an individual has advanced directives and you see dissention in family and that you can go back to that document and say “Your mom or your dad gave you the greatest gift when they did these documents so you wouldn’t have to carry the burden of making these decisions.” And when you frame it that way it kind of changes the whole context of the conversation. They still may not be comfortable, but they realize the greatest gift that they can give to their parent or loved one is honoring those wishes.” (Site 3, RN, female [S3_p6_clinician_RN]) |

| Triggers – unanticipated acute events, e.g. infections or falls | “Honestly, though, I think we’re more reactive. I think as a society we’re more reactive. And I think when people are pushed and busy we’re more reactive. And I think when people don’t want to deal with it we’re just going to say, “... we’re just going to wait until it comes up. We’re going to wait until somebody starts bleeding out ... and then we have to deal with it.” (Site 4, Nurse leader, female [s4_p41_leader_rn]) |

| Resources – training sessions | “... as part of the education they get at orientation...we came up with some scenarios, and then we try to use volunteers to act as patients and families. And then we’re just showing different people’s approaches to having the advanced care planning kind of conversations... you can lecture people, but sometimes to have them have the opportunity to see it... could they shadow some of us that do it all the time?” (Site 2, Physician leader, female, [s2_p27_leader_MD]) |

| Resources – committees to address complex cases and programs to initiate ACP conversations earlier for certain disease processes | “I’m noticing a lot more of what they call bridge programs. So while they’re not hospice patients, they’re getting quality care and maybe having some palliative radiation, say, for a tumor that’s pressed against the spine and the radiation reduces the tumor size and they have better pain control because of that..” (Site 3, RN clinician, [s2-p39-clinician-RN]) |

| Regulatory – Expanded ICD-10 codes and ACP planning codes now reimburse for non-hospice and primary care providers, though may be underutilized and not completely understood | “You can pretty much ICD-10 anything ... previously I would not have thought that major depression would have been a terminal diagnosis, we were able to say it actually was. This person had had a traumatic event where their husband had committed suicide in front of them and they had some other traumatic experiences. And so over the course of years, it had debilitated to a point where they were bed bound and like 50 pounds so they were hospice appropriate. It wouldn’t have been a traditional diagnosis that we would have used previously.” (Site 1, Leader, female [s1_p17_leader]) |

| Regulatory – Hospice Item Set prompt, detailed discussions and improves overall quality | “I use all of what we have to offer [Hospice Item Set measures] in different scenarios. Sometimes, what we have online for symptom management; a great tool. It helps me when I’m under the gun, when there’s exacerbation of symptoms, to ... have a reference to check ... I definitely think the tools work well.” (Site 3, RN clinician, male, [s2-p39-clinician-RN]) |

| Relationships between clinicians and patient/families - staff’s ability to assess patient/family readiness and openness and recall patient’s wishes | “the son has never wanted to do advanced directives, so after this conversation he made it quite clear to the social worker “These conversations need to stop,” but we kept it as a problem because it was still not addressed. So we review it every now and then with not much luck, and then just lately, actually two weeks ago, the doctor did a joint visit with the nurse.... the son said afterward “I didn’t know my mother felt that way.” And so a DNR has been signed, and he’s actively pursuing filling out advanced directives a year and a half later.” (Site 3, SW, female, [S3_p9_clinician_SW]) |

| Relationships with other facilities and processes of sharing forms and warm hand-offs | “...it starts on the referral, and it depends on where the referral’s coming from. So if they’re in the hospital we have a liaison that works in the hospital... she meets with them in the hospital, and she has a goals of care conversation with them, and it helps kind of determine a lot of those next steps. And so we’re fortunate in that that if we are getting a hospice referral that we have someone who can go and have that conversation, and there’s also a palliative team that’s working there too that can have those conversations, and if needed they can work together for those hand-offs as well.” (Site 1, Leader, female [s1_p17_leader]) |

| MOTIVATION FACILITATOR | |

| Desire to achieve ideal good practices through education for staff, planning, quality improvement cycles | “On any given day I have between five and nine staff members in the field .. and I really ask for five things ... first and foremost, obviously determining hospice eligibility, second of all, a good goals of care conversation, third is advance directives, fourth is medications and fifth is DME. ... I’m trying to build a best practices so we are in the midst of that where basically ... I do a two hour staff meeting once a month and the last 30 minutes ... has been really talking about our conversations and talking about how we introduce our conversation ... We also spend a couple of weeks on prep and how we prepare for our cases. So it’s going to be about an 8 to 12 month project of really having these great conversations with my staff, building best practices and then it will be something that actually we’ll use in on-boarding and everything.” (Site 4, RN, male, [s4_p40_clinician_RN]) |

| Hospice employee’s personal experience where ACP was needed and belief in (i) wanting to see more DNRs at home and (ii) earlier ACP conversations | “I think hospice will always it seems have a vested interest in wanting to see DNRs in homes, and I know that that is a statement that might be a little controversial, because we’re not supposed to probably have much of an opinion on that. Our goal is to never sway someone, but I think that we would always hope knowing that this person is going to take a last breath with us that they would not want CPR performed, but again if it is their wish to do so we will honor that wish too.” (Site 1, QI administrator, SW, female) |

| Belief in value of goals of care and patient-centered care | “the care plan in hospice is one of the most brilliantly devised tools ever in healthcare... It first exists with the belief that you have a peer professional or an interdisciplinary team of people that are looking at people as a holistic human being...that care plan should never be cookie cutter. It should truly come from the perspective of what matters most. What is most important to that patient and family and, of course, advance care directives or advance care planning are one of those tools to engage in those sorts of conversations” (Non-clinician leader) |

| Reflexes in response to family (e.g. letting family guide the goals of care conversations) | “Most people by the time they get to us are, I mean, and I think respectfully, we kind of let them be the guide. You know, I always say, you know, we don’t go anywhere we’re not invited. ... you know, knowing how to open the door a little bit and then if they don’t open a little bit on their side, then I’m not gonna keep trying to open it...And just kind of being respectful of that.” (Site 1, SW clinician, female [s1_p23_clinician_sw]) |

Table 2.

Themes and quotes reflecting barriers on capability, opportunity, and motivations in engaging patients and families in ACP conversations from hospice staff perspectives

| Theme | Illustrative quote or example |

|---|---|

| CAPABILITY BARRIER | |

| Lack of skillset to engage in ACP conversations | “I think barriers for the clinicians here is some of the newer staff, you know, it’s a “learned skill” is what I call it, to have that conversation. So think that the newer you are to hospice, the harder it is for you to have it, but it gets easier the lot more you do it. I still think, again, the biggest barriers are.. people don’t want to talk about it ... in the US, people don’t want to talk about the fact that everybody’s dying.” (Site 2, Physician leader, female [s2_p27_leader_MD]) |

| Overall fatigue, discouragement, or awkwardness in discussing death | “It just feels awkward, for one. Like I could think of a social worker trying to do it and feeling like they know this is part of their job so they’re trying to do it, but they don’t have a lot of skill in being sensitive and going with the flow of the conversation and being able to just approach it in a sensitive way. Like I had gone on an admission visit with a nurse with an infant. And her describing, “Well, that we want a DNR because of the violence involved with the resuscitation process.” And she used the word ‘violence’ several times with a three-day-old baby. There’s better ways to describe that.” (Site 4, Physician provider, male) |

| Perception of ACP as a checklist (e.g. Hospice Item Set) vs. having a quality conversation and meeting patient’s physical needs and managing symptoms | “You have to have an intuition with that, and I think that my team does, because if you just start talking about advanced directives because it’s on a checklist ... but the family is giving you that sign, “Stop” or “I’m not ready for this,” we need to respect that and not keep going, because then you are severing the relationship. You are now causing a trust barrier with that family ... you may have gotten your advanced directives discussion done, but now maybe they’re not quite sure whether or not hospice was the right decision, because, again, the majority of people in this society think that hospice is the death squad ... and if ... they don’t know anything about hospice and you go and start talking about advanced directives and DNR you’ve just validated that you’re the death squad ... You need not to make it a checking it off your list but really connecting with that family and finding out that time was important to them and then bringing up the advanced directives and then reading that reaction.” (Site 3, SW, female, [S3_p9_clinician_SW]) |

| OPPORTUNITY BARRIER | |

| Time constraints – patient-related | “...they’re diagnosed with advanced cancer and it’s already widely metastatic, they don’t have much time to deal with or even grasp the fact that they have cancer, much less are dying, and they’re gonna die by the time they get there. They don’t have much time to grieve. And it happens so quickly. And then what ends up happening is ... we end up, like, addressing all the physical needs and the symptom management, but then that emotional component, they still have to do that work and there’s no pill for that. So that can be a big barrier if they don’t have much time. The longer they have to cope with and accept, if they do accept that they’re, you know, that they have a terminal illness, the better.” (Site 4, RN, female, [4_p50_clinician_RN]) |

| Time constraints – staff-related | “A barrier for clinicians is the expected case load expectations, better, faster, cheaper; doing sacred work it just doesn’t make any sense. And so, I’m the one that’s saying oh this is what the case load needs to be. And do it really great, have a meaningful conversation, do all of your paperwork, make sure you get it all done and do it timely same day. And at some point something’s got to give.” (Site 4, Nurse leader, female [s4_p41_leader_rn]) |

| Patient and family are unprepared to discuss due to (i) young age, (ii) emotional state, and (iii) lack of appearance of serious illness | “Young parents on both parts, so

families of young people, particularly their parents (are not ready to

engage in ACP conversations or full discussions). You’re not

supposed to be caring for your....50-year old mom, so that’s

huge.” (Site 4, Physician leader, female

[s4_p42_leader_md]) “Or you get the sense that you don’t use the word hospice before you come in like (the family) greet you in the driveway, “Don’t say hospice and we’re not talking about death and dying.” Okay. And then you get the patient and they’re like, “Am I dying?” But they can’t say it in front of their loved ones.” (Site 4, Nurse leader, female [s4_p41_leader_RN]) “So there’s the-- they wanna hold out that hope that they’re gonna get better, and that’s where some of the resistance comes in ... there’s always another study and sometimes we get the patients that have gone through everything and they’re just incredibly tired of the whole thing, and they’re pretty far along so they don’t last long ... the biggest thing is they haven’t been able to accept it, so where there’s a still a certain amount of denial.” (Site 2, Chaplain, male [s2-p37-clinician-CP) |

| Complex family dynamics, including conflicting perspectives on ACP and goals of care within families | “...they just don’t wanna talk about it ... I can think of one family ... There’s seven children and ... they’re all on a different plane ... There’s a group of ‘em that can’t accept it. ... But the person that’s in charge, so to speak, that’s signature’s on the most and the do not resuscitate form, is a daughter and she’s very much onboard. And the poor guy is just suffering and we’re working very hard to overcome that.” (Site 2, Chaplain, male [s2-p37-clinician-CP) |

| Lack of resources to serve diverse communities (e.g. reliance on family as translators) | “This is a pretty diverse area. So, we do have-- it’s not uncommon pretty much every day in a Hospice Item Set record to read that “Patient’s son is translating. Patient speaks only Hungarian. Patient speaks only Arabic. Patient speaks only this or that.” We see that almost every single day, but it’s not an issue. As you know, hospice, we’re required to provide a translator and one’s not available.” (Site 3, QI administrator, female [s3_p3_QI]) |

| MOTIVATION BARRIER | |

| Personal estimates and perceptions on if/when ACP was done, documentation, ability to find goals of care documentation in medical record, and whether it conflicts with existing patient/family preferences | “Patient and family willingness can be a barrier. People are afraid to talk about it, or they otherwise don’t want to, or they think the decision’s already made. I’ve had any number of-- especially in palliative care-- patients tell me, “Well, I already have a living will,” implying that, therefore, “We don’t need to talk about this, because I’ve already done that.” And, “Okay, your living will, again, doesn’t help me right now.” So there’s some perception that, “Once I’ve done it, it’s done, and I never have to think about it again.” (Site 1, MD clinician, female, [s1_p21_clinician_MD]) |

| Lack of comfort in discussing death and in-depth goals of care conversations | “...I do think that our staff do back off a little too easily from having conversations, that as soon as there’s roadblocks about, “I’m not ready to go there,” they accept that as an answer because they hide-- and my impression is that they often hide behind, “Well, we have to meet families where they are,” and don’t sometimes have the urgency that they need to when-- sure, I can meet families wherever they are, but it is clear that we’re running out of time here, and we need to press a little bit more because when we don’t, we know what’s going to happen.” (Site 3, QI/Nurse Practitioner clinician, female [s3_p3_QI_NP]) |

| Personal biases, including perception of ACP as a tool which conflicts with (i) ability to have a conversation with the patient and family and (ii) staff’s own personal ability to focus on patient’s physical needs and symptom management (e.g. goals of care is a conversation) | “And that our goals are to respect to their goals and fall in line with that to the best that we can. And certainly it’s very common to have people that make decisions that are not in line with our decisions or our preferences in terms of what we feel would be the better outcome. ...And regardless of what you think is the best in their best interest they’re going to do it their way. So that’s something that we do try to honor. And without a doubt certainly I’m sure that I project and it comes across sometimes that I disagree with their approach. But that’s an ongoing learning process.” (Site 4, RN, male, [s4_p43_clinician_RN]) |

| Lack of awareness on cultural differences, difficulty engaging with non-English-speaking patients and families, and leaning on cultural stereotypes | “Hispanic families and African American families [are] just not as trusting of the medical community so the discussions are hard, ... there’s frequently this dichotomy of what they want but what it takes to get there they don’t like, so “I don’t want my mom hurting, but I don’t want you giving her pain medicines, because she’ll be sleepy. I don’t want her to have to go back to the hospital, but I certainly want her a full code, because I want to make sure you do everything,” so trying to get them to understand what “do everything” means, what does that mean to you or to the family, but I would say we see that a lot.” (Site 4, Physician leader, female [s4_p42_leader_MD]) |

Table 3.

Hospice staff recommendations for behavior and intervention functions linked to COM-B model to address previously identified barriers in engaging hospice recipients and families

| Barrier Themes | Recommendation for behavior change intervention or policy (definition) – example and quote |

|---|---|

| Barriers to Capability | Recommendations re: Capability |

| Lack of skillset to engage in ACP conversations |

Training (imparting skills) –

trainings led by specialists or experts “...we used our-- particularly our palliative-care certified physicians on staff are very good at this and using them to train our social workers and gain a level of comfort.” (Site 2, Nurse leader, female [s2-p34-leader-RN]) |

| Overall fatigue, discouragement, or awkwardness in discussing death |

Modelling (providing an example for

people to aspire or to imitate) – using practice sessions and

role-play “...as part of the education they get at orientation...we came up with some scenarios, and then we try to use volunteers to act as patients and families. And then we’re just showing different people’s approaches to having the advanced care planning kind of conversations...you can lecture people, but sometimes to have them have the opportunity to see it...could they shadow some of us that do it all the time?” (Site 2, Physician leader, female, [s2_p27_leader_MD]) |

| Perception of ACP as a checklist (e.g. Hospice Item Set) vs. having a quality conversation and meeting patient’s physical needs and managing symptoms |

Enablement (increasing means/reducing

barriers to increase capability or opportunity) – focus on

building rapport and having quality

conversations “...I actually think that conversation can help with advance directives. I think it’s having a conversation first of all what the goals of care are can help someone to better decide about filling out a form for an advance directive. So yeah, I think it’s a more meaningful place to start than just, “Please fill out this form, select if you want to be resuscitated,” I don’t think that’s a very good way to start a conversation or I don’t think it’s a good way to build rapport or anything like that.” (Site 4, SW, female, [s4_p48_clinician_SW]) |

| Barriers to Opportunity | Recommendations re: Opportunity |

| Time constraints – patient-related |

Service provision (delivering a

service), e.g. palliative care pre- hospice admission that

encourages earlier ACP conversations “And I know that in our palliative care, they do a good job too. The social workers on that side, they do, because when our palliative care patients come to us, they’ve got those [documents].” (Site 1, SW clinician, female [s1_p23_clinician_sw]) |

| Time constraints – staff-related |

Education (increasing knowledge or

understanding), e.g. provide education to clinicians and

administrators in pre-hospice locations such as hospitals and

nursing homes. “I would like to see if they could get more presentations in nursing homes and hospitals. That’s where we seem to struggle the most with understanding ... hospitals, they have their own training, probably nursing homes have their own training, but maybe they come from the aspect of how do advanced directives affect a hospice patient or a palliative care patient more so than just in general.” (Site 3, Leader, female, [s3_p4_leader]) Guidelines (e.g. creating documents that recommend or mandate practice, includes all changes to service provision), e.g. mandating ACP conversations for any healthcare encounter “I don’t think people know how important it is to do your care-- to talk, at least talk to your family about what you want. If something should happen to me, because we just see too many people who don’t have a clue, you know. And I hate that, because then I think they end up having a lot of interventions that maybe that patient didn’t want. So or just knowing, just knowing. But, you know, nobody’s really doing that out there. Nobody’s really talking about that... And so I think that, to me, is just the big lack, the big gap in our healthcare right now is folks just not having those conversations.” (Site 1, SW clinician, female [s1_p23_clinician_sw]) |

| Patient and family are unprepared to discuss due to (i) young age, (ii) emotional state, and (iii) lack of appearance of serious illness |

Communication/marketing (using print,

electronic, telephone, or broadcast media), e.g. providing written

manuals or check-lists to introduce and guide

conversations “[Our company] has a really great manual that we give people at admission, a comfort and caring manual, and the nurses use that and the social workers and the chaplains as a way to introduce conversations. It’s broken up into a bunch of different chapters ... there’s one on signs and symptoms of you know, the end of life which is really helpful. ... The nurses can say, “Well, let’s look at the manual.. let’s look at chapter one,” and you know, they’re able to start those conversations early” (Site 2, RN clinician, female, s2-p38-clinician-RN) |

| Complex family dynamics, including conflicting perspectives on ACP and goals of care within families |

Service provision (delivering a

service), e.g. IDT continues to monitor and revisits at a later

time; hospice organization creates a specific committee to handle

tough cases “... if I were in a home and I talked with the family and they were adamant that they did not want to discuss the DNR I would typically leave it at that point, because if they’re not in an okay place I’m not going to push that with them .. typically later on it was okay to broach that topic again, but the team would keep that top of mind with that patient.” (Site 1, SW QI, female, [s1_p15_QI_SW]) |

| Lack of resources to serve diverse communities (e.g. reliance on family as translators) |

Environmental restructuring (changing

the physical or social context), e.g. have the workforce reflect the

patient populations one wants to reach “... we think about that strategically, of how to serve the underserved and get the diversity that we need. We need that in our workforce as well.” (Site 2, RN leader, female, [s2_p29_leader_RN]) Enablement (increasing means/reducing barriers to increase capability or opportunity), e.g. expand translator services for all languages “there might be a language barrier and if I’m using a translator, I know in the Vietnamese community ... it’s a small community, so if I got a translator they probably know that family and it’s not necessarily going to stay private. That’s been my experience. So families don’t always necessarily want to talk about some of those things.” (Site 4, SW, female [s4_p51_clinician_SW]) |

| Barriers to Motivation | Recommendations re: Motivation |

| Personal estimates and perceptions on if and when ACP was done, whether it was documented, ability to find goals of care documentation in medical record, and whether it conflicts with existing patient/family preferences |

Environmental restructuring (change the

physical or social context), e.g. prompts or easy-access buttons to

provide information on what portions of ACP and forms have been

done, by whom, and when. “I think that communication of goals of care across sites and between teams could be better. So there are times when I’m asking patients what-- you know, what’s important and what they would like to have done or not done, they’ll say, “Well, I just told that to somebody yesterday, don’t you ever read--” you know, that sort of thing. So, you know, so do people have to kind of print and you need to repeat. So I think, from my standpoint, that could be a little bit better, as far as that communication piece.” (Site 3, MD leader, male, [s3_p1_leader_MD]) |

| Lack of comfort in discussing death and in-depth goals of care conversations |

Enablement (increasing means/reducing

barriers to increase capability or opportunity), e.g. having

clinicians “skilled” in having ACP discussion

available “...there’s very skilled clinicians in this company. They make my job easy. They can deescalate folks and maybe they can’t turn around their thoughts that day, but they can certainly educate them within the next few days into understanding what’s going on.” (Site 2, MD leader, female, [s2_p34_leader_MD]) |

| Personal biases, including perception of ACP as a tool which conflicts with (i) ability to have a conversation with the patient and family and (ii) staff’s own personal ability to focus on patient’s physical needs and symptom management (e.g. goals of care is a conversation) |

Persuasion (using communication to

induce positive or negative feelings or stimulate

action) “contrasting the Hollywood approach of you’re going to be resuscitated and everything is great versus what things-- what it actually looks like in practice with some-- certainly there are some statistics we can provide about what the fact that a lot of people do not come back in the same condition after they’ve had CPR. And the potential for brain deterioration and so forth.” (Site 3, QI/NP clinician, female, [s3_p3_QI_NP]) |

| Lack of awareness on cultural differences, difficulty engaging with non-English-speaking patients and families, and leaning on cultural stereotypes |

Education (increasing knowledge or

understanding), e.g. understand where different cultural and racial

perspectives may come from, the meaning of death and dying in

different cultures, structural

inequalities “using people’s stories and to teach clinicians, we actually use that in the immersion course where we do poetry reading by African-Americans, and some of the issues they’ve had with the health care system and teach clinicians, you know, try to create empathy and understand people’s stories as a way to engage them. Because some of the time I think clinicians can be judgmental in why people are pursuing-- some of the kind of treatment they’re pursuing. And when you have an understanding for where people are coming from, and maybe some of the mistreatment and some of the issues around institutional racism and all that. I think that you can teach some of that to clinicians. So ... we created a one-day training, two four-hour blocks for clinicians. And it incorporates a lot of that specifically for African Americans. But we have that every year for new clinicians that are coming on board. So trying to create some of that cultural competency, where I think some of the biggest issues come with advance care planning and goals of care.” (Site 1, MD leader, female [s1_p24_leader_MD]) Persuasion (using communication to induce positive or negative feelings or stimulate action), e.g. use resources like community health workers to communicate to their own culture “We’re looking at getting culturally-based liaisons to go into various communities, folks that they can relate to, to educate regarding hospice and palliative care and alternatives to care as we move forward, as our census grows.” (Site 2, Nurse leader, female [s2-p34-leader-RN]) Enablement (increasing means/reducing barriers to increase capability or opportunity), e.g. increasing time to build trust to allow in-depth conversations “Trust is the key there to be able to have that conversation, well, like with any different culture, but that one’s for me personally have been a more challenging situation... I have found in my practice that usually it requires a more in-depth conversation and validating and showing more compassion” (Site 3, SW clinician, female [s3_p9_clinician_SW])” |

Capability

Capability for ACP engagement was facilitated by the interdisciplinary team and staff roles

Hospice staff noted “the team approach, that getting everybody on the same page at the same time” facilitated ACP engagement (increased capability) through the combination of multiple disciplinary backgrounds and abilities (s4_p44_clinican_MD). If one team member was not able to discuss values, fears, and concerns with the patient/family, another team member (i.e. “patient-whisperer”) who felt more comfortable could step in and help: “the SW helps to get the conversation going, and then, ... if it’s a really complex issue, we’ll have our physician go out” (s2_p29_leader_RN). Inclusion of other team members allowed for well-tailored and compassionate conversations.

Participants discussed how different disciplines contributed in different ways to ACP engagement. Nurses and physicians most commonly discussed code status and the need to complete documents such as Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment. SWs performed case assessments, “owned the advance directives”, and were critical in managing unfinished ACP forms and getting copies uploaded to the electronic medical record (EMR) (s4_p42_leader_MD). Chaplains were essential in assisting with funerary arrangements. For example, one nurse described the interdisciplinary team (IDT) as follows:

“There’s many facets of the IDT team. There’s nursing, doctor, social work, chaplaincy, volunteers….if it’s an advance directive or a GOC question, the doctor or the nurse is gonna tackle it from one end and the other interdepartmental team members are gonna tackle it from another end ... You can tackle that from many different aspects of the team to get somebody to understand it better.” (s1_p19_clinician_nurse)

Personal discomfort in discussing end-of-life reduced capability for ACP

At all four sites, clinicians identified obstacles to capability, including perceived- and personally-experienced discomfort in discussing death and ACP. Participants attributed discomfort to lack of confidence or skill as “some clinicians do not understand what advance directives are” (s3_p9_clinician_SW). As one nurse leader shared, ACP is a skill that requires “experience” and “mindfulness,” and that can pose challenges with caseload requirements:

“The barriers for staff is just really having the tools to have the meaningful Deep conversations that come with experience or training. And the willingness to be in the struggle. We can have great clinicians that are very adept technically and are efficient. Do they really engage? Really with presence? ... Our clinicians who are willing to be slower and grieve with people and do the wisdom work aren’t so good technically or technologically and their pace is really slow. And then they can’t carry the caseload requirements.... What we’re asking hospice and palliative care clinicians to do is really nuanced difficult work.” (s4_p41_leader_RN)

Opportunity

Activating elements in the physical environment

Participants noted that admission to hospice and unanticipated acute events, such as intercurrent hospitalizations, provided the main opportunities to initiate and revisit ACP conversations. On hospice admission, staff in all four sites assessed whether advance directives were available and flagged patients who were full-code, requested “aggressive” interventions, and had conflicting perspectives on ACP preferences with family members: “we usually ask the questions, but if the questions get pushed to the side and the subject change[d], then we put that in our summary” (s1_p19_clinician_nurse). Staff discussed these patients at IDT meetings and revisited ACP at any available opportunity.

Structural reminders, such as the Hospice Item Set questions, facilitated ACP conversations by requiring documentation of assessment of preferences or not. As one nurse leader stated, the structured questions “force people to address things that need to be addressed, so I see it only helping our quality, not hurting us” (s2_p29_leader_RN).

Environmental constraints included time restrictions and patient/family characteristics

Most staff remarked on how time constraints for both patients (e.g. length of time in hospice) and clinicians (e.g. time needed to have meaningful conversations) reduced opportunities to engage in ACP. Referrals to hospice close to the time of death shortened the time available for engagement in meaningful ACP conversations making “...it so hard to get all of that information and act on it, when they’re on for a very short period of time” (s2_p27_leader_MD).

Workload-related time constraints for clinicians required prioritization of ACP versus seeing other patients with urgent and distressing symptoms. Additional physical and social environmental factors that made ACP conversations difficult for staff included serving young patients, reliance on family members as interpreters, or conflicts between patient and family members regarding treatment preferences “because they wanna talk to their loved one but also want them to have pain control and the two can conflict at times” (s2_p39_clinician_RN).

Motivation

Top motivator for ACP conversations was strong desire for personalized, patient-centered care

One SW summarized the importance of whole person-focused conversations as follows:

“Not only are they the physical and medical GOC, but they’re also the emotional/spiritual, what feeds their soul GOC, and that’s important to know. That’s the foundation of hospice work: their individualized GOC and making them know that we embrace that and we will follow that.” (s3_p9_clinician_SW)

Preconceptions that lowered staff motivations for ACP

Several staff acknowledged that once they were familiar with a patient or families’ preference, they revisited ACP less often. A QI administrator commented that problems arose when clinicians lost the motivation to read other IDT team members’ EMR notes:

“...there were so many issues about people not reading the EMR, just focusing in on entering into that system what they had from this visit and not really referring back to, “Well, yeah, but I know that patient, so this is baseline for them.” “Did you look at what the SW wrote yesterday and how—what they said yesterday compared to--?” “No, I know this patient”.... “The more you get familiar with your own caseload, the less you look at a chart. I mean it’s wrong. It’s wrong. It’s dangerously wrong, but it is the reality.” (s3_p5_QI_NP)

Challenges for long-time hospice staff adjusting to implementation of and changes in EMR also lowered staff motivation for ACP engagement.

Although our original question asked only for the identification of patterns seen amongst patients and families who did not want to engage in ACP, we found participants at each site who responded with racialized, ethnic, and religious stereotypes that marked certain groups as “difficult” and reduced clinician motivation to engage those families in ACP. Several clinicians generalized that certain groups “do everything till the end.” One physician spoke of a “fear of saying the H-word” out of beliefs that it might hasten death, and a nurse asserted that the meaning of the word “hospice” changed in translation to another language. The additional time required to communicate with non-English-speaking patients and families was perceived by several as inconvenient. One leader stated utilizing interpreters “complicated the process” and observed that interpreters were not always available. But these assumptions were also questioned by other participants, such as a SW who described how what she saw and experienced with families was different from what she had been taught to believe.

Behavior-change recommendations

We asked participants for specific recommendations from their organizations and linked these recommendations to previously identified barriers (Table 3).

To facilitate capability, staff members at three sites emphasized orientation and training sessions led by specialists or experts to increase “skills” and modelling practice sessions that used role-play to apply skills and increase clinician comfort. One nurse explained: “You learn by watching someone do it really well. So we do a lot of... observing, and then the tables turn, where you’re the talker and someone else is observing, and then thatperson can then debrief after.” (s2_p36_clinician_RN)

With regards to opportunity-related barriers of time constraints, participants advocated for guidelines or mandates for ACP conversations at any healthcare encounter. They highlighted the importance of engaging clinicians and administrators in pre-hospice locations and not “passing the buck” (s4_p32_clinician_MD).

Clinician motivation to engage patients and families in ACP decreased due to preconceptions and assumptions of preferences. In response to barriers related to lack of knowledge of cultural, racial, and ethnic norms and backgrounds, leadership at one site recommended increasing workforce diversity to reflect the patient populations the organization wanted to reach and to cultivate cultural humility. This site utilized community health workers and “culturally-based liaisons” in order to reach communities. Leadership at this site also provided to staff trainings and education “so that we’re able to understand what death and dying is to [different] cultures” in order to increase cultural humility, create empathy, and increase understanding of people’s life stories as way to increase ACP engagement (s2_p29_leader_RN).

Discussion

In this study, hospice staff identified facilitators and barriers to discussing ACP with patients and families. The presence of multiple team members and variety of clinical roles mitigated clinician discomfort in engaging patients and families in ACP conversations (capability). Activating events such as admission to hospice and major changes in patient condition provided opportunities while patient- and clinician-associated time constraints limited opportunities. Personal commitment to providing patient-centered care was a key motivator. Yet, assumptions about a patient or families’ preferences reduced staffs ability and motivation to engage patients and families in ACP. This novel study makes explicit the implicit, providing insight into hospice staff perceptions of the structure and content of ACP conversations and the broader factors that facilitate or hinder engagement. It builds on our prior work describing hospice staff perspectives on caring for people with dementia, discussing ethical dilemmas related to caring for people with preferences for full code and aggressive treatments, and measuring ACP quality.7,8,14 Here, we highlight staff-identified practice elements that facilitated high-quality ACP conversations and goal-aligned care as well as opportunities to improve. These data, coupled with participant recommendations, can provide targets for future interventions aiming to further improve hospice ACP.

Knowing patient and family values is central to the hospice staffs work and aligns with the core mission of hospice.15 Yet more than half of the staff in our study defined ACP narrowly as completion of documents and orders, which reflects the wide range of ACP definitions in the field. A Delphi panel of multidisciplinary, international ACP experts only developed a consensus definition of ACP in 2017, which focuses on the iterative process that supports people’s understanding and sharing of their personal values, life goals, and preferences.1 Our results suggest discrepancies exist within hospice organizations on whether to focus on advance directives versus conversations and more education about the evolving and broadening field of ACP may be needed.

Even in hospice, clinicians expressed discomfort in discussing death and GOC. Behavior change recommendations to increase clinician comfort included trainings to increase “skills” and modelling practice sessions that used role-play to apply these skills. Outside of hospice, similar trainings have been developed around teaching ACP conversations including the Vital Talk curriculum, Education in Palliative and End-Of-Life Care program, and trainings from the End-Of-Life Nursing Education Consortium and Center to Advance Palliative Care.16–19 Clinicians in pre-hospice settings may benefit from behavior change training in ACP engagement in order to increase opportunities for meaningful ACP conversations.20 Clinician involvement in pre-hospice settings is necessary if we are to address the fact that median hospice enrollment was 18 days in 2018 compared to 6-month enrollment eligibility.15

Additional barriers to ACP conversations occurred when clinicians fell back on defaults: (1) assumptions that may not be consistent with evolving patient/caregiver ACP preferences and (2) implicit bias based on racialized or stereotyped assumptions. A handful of participants used stereotypes that mirrored some of the problematic ways in which health inequities have been blamed on socioeconomic, religious, racialized21, and cultural groups rather than on structural drivers of disparities.22 This stereotyping is concerning as it compartmentalizes diverse cultural, racial, and ethnic backgrounds and may inhibit trust with diverse groups of patients and families already at increased risk to receive lower quality health care.23,24

A substantial majority (82% in 2018) of hospice patients are white15, which reflected the race/ethnic characteristics of our staff participants (88% white). Our participants recognized a need to diversify the hospice workforce to better reflect the racial and ethnic makeup of the U.S. and suggested diversity, equity, and inclusion training to confront stereotypes and bias.25,26 Explicitly acknowledging the role that racism (institutionalized, internalized, interpersonal27) and other stereotypes about nationality, religion, and income has on the patients’ and families’ experience over their lifetimes and cultivating cultural competence would improve hospice ) care.28,29 Acquaviva and colleagues recommend conducting a thorough family and social history that includes questions about cultural beliefs and practices, geographic ancestry, physical environment, and emphasizes the need for inclusive language.30,31

Limitations included recruitment from hospices that were committed to palliative care research (through PCRC) and limited geographic locations. Staff recommendations drawn from participating practices may be difficult to implement in hospices with fewer resources or may differ from the priorities of for-profit hospices.

Conclusions and implications

Systemic barriers to ACP still remain in hospice; even hospice staff can be uncomfortable discussing death and dying. Hospice workers identified factors to inform ACP-related behavior change interventions, including interdisciplinary teamwork, training/practice sessions, workforce diversity, and individual commitment to patient-centered care. These practice elements provide targets for intervention, as do identified barriers: lack of training in ACP engagement and implicit bias, lack of diversity among hospice staff, and lack of adequate time to do the “wisdom work” of ACP. Integration of evidence-based training programs, formal diversity, equity and inclusion training with accompanying recruitment of diverse clinicians are appropriate next steps toward ensuring that hospice adequately engages in ACP at the end-of-life.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank the participants from the four hospice organizations included in this study and members of the community advisory group. We would like to thank the Palliative Care Research Cooperative (PCRC) leaders and members of our community advisory group for their formative feedback on study design and Gabrielle Dressler for her assistance with early phases of analysis

Funding sources:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under award number U2CNR014637. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This work was supported by a pilot award to Dr. Harrison from the Palliative Care Research Cooperative (PCRC) Group funded by National Institute of Nursing Research (U24NR014637). The authors received funding from the following sources: VA Office of Academic Affiliations (Grant AF-3Q-09-2019-C), UCSF Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center funded by National Institute on Aging (P30 AG044281); and National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health (Allison K23AG062613, Harrison K01AG059831, Sudore K24AG054415). The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or other funders. The funders had no role in development of the study, data acquisition, data interpretation, writing, or editing of article.

Appendix.

| Methodologic orientation and theory | The overarching qualitative, multi-site study32 was based on a subtle realist epistemology.33,34 The study design is based on the social science case study approach,35,36 appropriate for a study focused on a particular issue or concern (the process of determining and enacting preferences for end-of-life care) in the context of a purposively chosen, clearly identifiable and bounded case used to illustrate the issue (hospice organizations).37 Within the case study approach, qualitative methods were selected as appropriate for exploratory and descriptive research questions related to processes and ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions not previously addressed in the literature. No data previously existed on hospice staff members’ perceptions of the practice or measurement of the process of determining and enacting preferences for end-of-life care, making it essential to use a flexible methodology for the formative research. |

| Interview guide | The interview guide used the Theory of Domains Framework38 (which is also the basis for the COM-B framework) to investigate hospice staff member attitudes and practices of ACP (as individuals or on behalf of the organization), as well as perception of factors relevant to behavior change. The guide was reviewed and refined in consultation with Palliative Care Research Cooperative (PCRC, https://palliativecareresearch.org/) methods experts and a community advisory group which consisted of 7 individuals within a local non-participating hospice who were clinicians, quality improvement administrators, executive leaders, and volunteers who were formerly caregivers. Copies of the interview guide were provided in advance for two study participants upon request (provided below). In conjunction with the interview, participants were asked to share either internal or external documents relevant to the study. Examples of documents included brochures about dementia-specific care available by the front desk; materials carried by clinicians to aid discussions about preferences or advance care planning, such as Respecting Choices or POLST forms; a redacted patient chart printed out; copies of quality improvement projects related to ACP; or copies of quality measure dashboard results. |

| Qualitative interview guide used for this study | 1. Tell me about the discussions you

have with referred or newly admitted patient and/or family

seeking care from the hospice organization about preferences for

care. What are you specifically referring to (e.g. advanced care

planning [ACP] vs. goals of care [GOC] conversations)? How does

the ACP/GOC discussion affect the plan of care? How often do you

revisit the conversations about preferences with patients and

families? Do you know what is in the ACP documents for all your

patients? 2. How often do admissions to hospice already have ACP discussion or forms completed? 3. How do you/members of your organization communicate the results of the ACP/GOC discussion to other team members? How formal or informal is the communication? 4. What are the barriers to full discussions of ACP/GOC? i. Are barriers for patients due to capability, opportunity, or motivation? ii. Barriers for families due to capability, opportunity, or motivation? iii. Barriers for clinicians due to capability, opportunity, or motivation? 5. What patterns do you see among patients and families that do not want to engage in ACP or where conflicts occur around ACP? Due to age or prognosis, symptoms, cognitive impairment, setting of care (home care vs. facility vs. inpatient), type of caregiver (spouse vs. parent vs. child), socioeconomic, race, ethnicity, or culture? 6. What currently works well in your team or organization’s practice of asking patients and families about ACP/GOC? 7. What could your team or organization do differently to improve ACP/GOC discussions with patients and families? 8. How does the organization monitor the presence, quality, or frequency of GOC/advance directives [AD] discussions? What are the barriers to monitoring GOC/AD across the patient population (capability, opportunity, motivation)? What could be done differently or better about how your organization measures GOC/AD? 9. Describe what happens when the patient/family preferences do not align with the hospice philosophy? |

| Field notes | Hand written field notes were made during the interview (recording key details and questions to return to) as well as after the interview (including reflections on what went well or poorly, the interviewer’s emotional and physical state that may have influenced data collection, or environmental factors influencing the interview (e.g. interrupting phone call, thunderstorm); additional topics that the participant discussed after the recording was ended; questions to ask other participants or probes to consider adding to the interview guide; and analytic thoughts about new topics, common topics arising within participants at that site or across sites, or comparisons by type of participant or site). All field notes were created in a de-identified way using participant ID keys only. Overarching notes were also created at the beginning and end of each site visit. |

| Data saturation | Data saturation on broad themes (e.g. process of engaging hospice enrollees in discussion of preferences, documenting preferences, measuring discussions and documentation) was reached at all sites. Saturation by participant type (e.g. leader, clinician, administrator) within or across sites was not attempted. |

| Description of the coding tree | For the overarching study, deductive

primary codes included: • context of the site (secondary codes: site context, hospice admission process, pre-hospice discussion or documentation of end-of-life care preferences, state policy, changes over time); • practice of engaging enrollees/proxies in discussion of end-of-life care preferences (inductive secondary codes: practices generally, good practices, team roles, team communication, training, documentation, materials/forms, and implementing stated preferences); • measurement (inductive secondary codes: quality assessment generally, quality measures, quality improvement); • attitudes, opinions and beliefs (inductive secondary codes: stakeholder opinion, perception of patient/family perspectives, recommendations, connotations of advance care planning, perceptions of importance of discussion of end-of-life care preferences; tensions between patient, family or clinician preferences) • emergent cross-cutting themes (inductive secondary codes: facilitators/barriers, policy-relevant topics, aggressive care or full code; dementia). |

| Derivation of themes | Primary codes and some secondary codes for the overarching study were deductively derived from the research question and interview guide. The majority of the secondary or tertiary codes inductively derived from the data. This process was repeated with the entire interdisciplinary author team. |

Footnotes

No conflicts of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. Defining Advance Care Planning for Adults: A Consensus Definition From a Multidisciplinary Delphi Panel. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(5):821–832.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schichtel M, Wee B, MacArtney JI, Collins S. Clinician barriers and facilitators to heart failure advance care plans: a systematic literature review and qualitative evidence synthesis. BMJ Support Palliat Care. Published online July 22, 2019. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2018-001747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ufere NN, Donlan J, Waldman L, et al. Barriers to Use of Palliative Care and Advance Care Planning Discussions for Patients With End-Stage Liver Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2019;17(12):2592–2599. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Threapleton DE, Chung RY, Wong SYS, et al. Care Toward the End of Life in Older Populations and Its Implementation Facilitators and Barriers: A Scoping Review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(12):1000–1009.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci IS. 2011;6:42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Onken LS, Carroll KM, Shoham V, Cuthbert BN, Riddle M. Reenvisioning Clinical Science: Unifying the Discipline to Improve the Public Health. Clin Psychol Sci J Assoc Psychol Sci. 2014;2(1):22–34. doi: 10.1177/2167702613497932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrison KL, Allison TA, Garrett SB, Thompson N, Sudore RL, Ritchie CS. Hospice Staff Perspectives on Caring for People with Dementia: A Multisite, Multistakeholder Study. J Palliat Med. Published online March 4, 2020. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2019.0565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dressler G, Garrett SB, Hunt LJ, et al. “It’s Case by Case, and It’s a Struggle”: A Qualitative Study of Hospice Practices, Perspectives, and Ethical Dilemmas When Caring for Hospice Enrollees with Full-Code Status or Intensive Treatment Preferences. J Palliat Med. Published online in press 2020. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2020.0215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, et al. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(1):26–33. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.011155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The Behavior Change Wheel Book - a Guide to Designing Interventions. Silverback Publishing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldaña J. Designing matrix and network displays. In: Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd ed. SAGE Publications; :107–120. [Google Scholar]

- 12.King N Using templates in the thematic analysis of text. In: Essential Guide for Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research. SAGE Publications Ltd; 2004:256–270. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brooks J, McCluskey S, Turley E, King N. The Utility of Template Analysis in Qualitative Psychology Research. Qual Res Psychol. 2015;12(2):202–222. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2014.955224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunt LJ, Garrett SB, Dressler G, Sudore R, Ritchie CS, Harrison KL. “Goals of Care Conversations Don’t Fit in a Box”: Hospice Staff Experiences and Perceptions of Advance Care Planning Quality Measurement. J Pain Symptom Manage. Published online October 20, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.09.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. NHPCO Facts and Figures: 2020 Edition.; 2020. https://www.nhpco.org/wp-content/uploads/NHPCO-Facts-Figures-2020-edition.pdf

- 16.VitalTalk. VitalTalk. Want to be a better communicator? https://courses.vitaltalk.org/courses/

- 17.Northwestern Medicine Feinberg School of Medicine. EPEC: Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care. EPEC: Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care. Published 2019. Accessed September 22, 2020. https://www.bioethics.northwestern.edu/programs/epec/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Association of Colleges of Nursing. End-of-Life Care (ELNEC). ELNEC Curricula. Published 2020. Accessed September 22, 2020. https://www.aacnnursing.org/ELNEC/About/ELNEC-Curricula [Google Scholar]

- 19.Center to Advance Palliative Care. Building Physician Skills in Basic Advance Care Planning. Accessed September 22, 2020. https://www.capc.org/training/building-physician-skills-basic-advance-care-planning/

- 20.Sudore RL, Fried TR. Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(4):256–261. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-4-201008170-00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shim JK. Constructing ‘Race’ Across the Science-Lay Divide: Racial Formation in the Epidemiology and Experience of Cardiovascular Disease. Soc Stud Sci. Published online June 29, 2016. doi: 10.1177/0306312705052105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fernandez A The Unacceptable Pace of Progress in Health Disparities Education in Residency Programs. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2013097. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.13097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rhodes RL, Teno JM, Connor SR. African American bereaved family members’ perceptions of the quality of hospice care: lessened disparities, but opportunities to improve remain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34(5):472–479. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rizzuto J, Aldridge MD. Racial Disparities in Hospice Outcomes: A Race or Hospice-Level Effect? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(2):407–413. doi: 10.1111/jgs.l5228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanders JJ, Johnson KS, Cannady K, et al. From Barriers to Assets: Rethinking factors impacting advance care planning for African Americans. Palliat Support Care. 2019;17(3):306–313. doi: 10.1017/S147895151800038X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ejem DB, Barrett N, Rhodes RL, et al. Reducing Disparities in the Quality of Palliative Care for Older African Americans through Improved Advance Care Planning: Study Design and Protocol. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(S1):90–100. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2019.0146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1212–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boyd RW, Lindo EG, Weeks LD, McLemore MR. On racism: a new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. Health Affairs Blog. Published July 2, 2020. Accessed September 29, 2020. 10.1377/hblog20200630.939347/full/ [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boucher NA, Johnson KS. Cultivating Cultural Competence: How Are Hospice Staff Being Educated to Engage Racially and Ethnically Diverse Patients? Am J Hosp Palliat Care. Published online July 31, 2020:1049909120946729. doi: 10.1177/1049909120946729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Acquaviva KD, Mintz M. Perspective: are we teaching racial profiling? The dangers of subjective determinations of race and ethnicity in case presentations. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2010;85(4):702–705. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d296c7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosa WE, Shook A, Acquaviva KD. LGBTQ+ Inclusive Palliative Care in the Context of COVID-19: Pragmatic Recommendations for Clinicians. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(2):e44–e47. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rendle KA, Abramson CM, Garrett SB, Halley MC, Dohan D. Beyond exploratory: a tailored framework for designing and assessing qualitative health research. BMJ Open. 2019;9(8):e030123. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mays N, Pope C. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ. 2000;320(7226):50–52. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.RWJF - Qualitative Research Guidelines Project | Critical or Subtle Realist Paradigm | Critical or Subtle Realist Paradigm. Accessed March 15, 2021. http://www.qualres.org/HomeCrit-3517.html

- 35.Yin RK. Case Study Research and Applications. 4th ed. SAGE Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.George AL, Bennett A. Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences. MIT Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. SAGE Publications; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, et al. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(1):26–33. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.011155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]