Abstract

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has underscored the need for rapidly usable prophylactic and antiviral treatments against emerging viruses. The targeted stimulation of antiviral innate immune receptors can trigger a broad antiviral response that also acts against new, unknown viruses. Here, we used the K18-hACE2 mouse model of COVID-19 to examine whether activation of the antiviral RNA receptor RIG-I protects mice from lethal SARS-CoV-2 infection and reduces disease severity. We found that prophylactic, systemic treatment of mice with the specific RIG-I ligand 3pRNA, but not type I interferon, 1–7 days before viral challenge, improved survival of mice by up to 50%. Survival was also improved with therapeutic 3pRNA treatment starting 1 day after viral challenge. This improved outcome was associated with lower viral load in oropharyngeal swabs and in the lungs and brains of 3pRNA-treated mice. Moreover, 3pRNA-treated mice exhibited reduced lung inflammation and developed a SARS-CoV-2-specific neutralizing antibody response. These results demonstrate that systemic RIG-I activation by therapeutic RNA oligonucleotide agonists is a promising strategy to convey effective, short-term antiviral protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection, and it has great potential as a broad-spectrum approach to constrain the spread of newly emerging viruses until virus-specific therapies and vaccines become available.

Keywords: MT: Oligonucleotides: Therapies and Applications, coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, RIG-I, type I IFN, innate immunity, nucleic acid immunity, antiviral immunity, K18-hACE2 mouse model, emerging viruses, pandemic

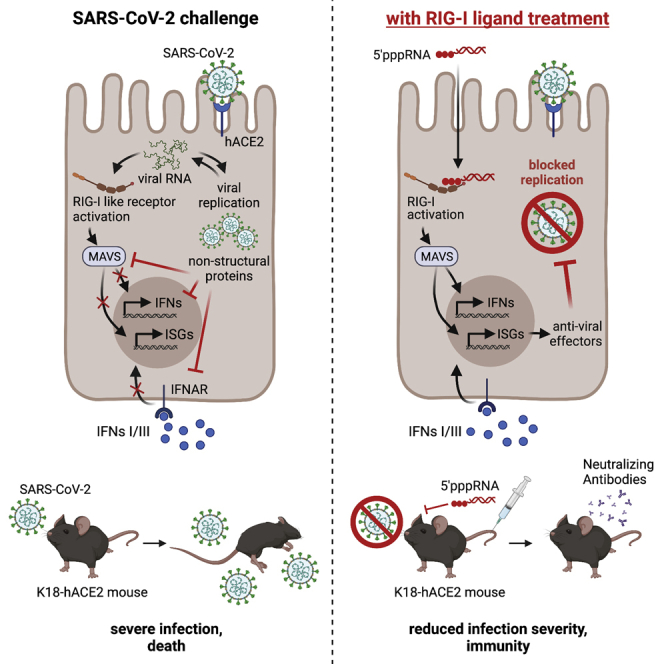

Graphical abstract

Nucleic acid receptors such as RIG-I are essential to the antiviral innate immune response. In this study, Marx and colleagues report that the activation of RIG-I by a specific 3pRNA ligand protects hACE2-transgenic mice from otherwise lethal SARS-CoV-2 infection, demonstrating the potential of 3pRNA treatment for the containment of emerging viruses.

Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic has called to attention the vital importance of rapid, effective strategies for limiting the spread of emerging viruses. SARS-CoV-2 is the etiological agent of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19),1,2 which infects the upper and lower airways of patients but also can cause neurological symptoms, in particular anosmia.3,4 The clinical course of COVID-19 is extremely variable between individuals, from mild symptoms to severe interstitial pneumonia requiring mechanical ventilation. Since the initial outbreak in 2019 in Wuhan, China, SARS-CoV-2 virus infection has resulted in more than 290 million confirmed COVID-19 cases and over 5.4 million deaths (https://COVID19.who.int/, status January 6, 2022). Moreover, we are only beginning to understand the extent of its socioeconomic repercussions, including the impact of chronic disease,5 loss of primary caregivers,6 unemployment, and school closures. While tremendous efforts are being made to control the virus, the development of vaccines has progressed more rapidly than the development of direct antiviral treatments.7 Repurposed small-molecule antiviral drugs such as remdesivir, molnupiravir, or monoclonal antibody cocktails have shown only modest efficacy with moderately improved survival rates compared with placebo in hospitalized patients.8, 9, 10 Hence, there is still a great need for new and effective antiviral drugs against SARS-CoV-2.

SARS-CoV-2, like other betacoronaviruses, possesses multiple features that allow it to subvert our antiviral defenses and cause disease. SARS-CoV-2 codes for several structural and non-structural proteins that inhibit antiviral signaling cascades11,12 as well as enzymes that cap and methylate (Cap1) its nascent transcripts.13,14 By using a Cap1 structure, SARS-CoV-2 molecularly mimics our own messenger RNA (mRNA), allowing it to escape recognition by critical, antiviral restriction factors such as interferon (IFN)-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1 (IFIT1) and innate immune sensing receptors such as retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I).15, 16, 17 Nevertheless, the induction of an innate antiviral response that includes type I and type III IFN and direct antiviral effector functions in infected cells is essential for the development of an appropriate adaptive immune response.17 Thus, despite numerous escape mechanisms, type I IFN still plays a key role in the SARS-CoV-2 immune defense.18,19 A robust early type I IFN response is associated with the clearance of the infection, whereas its absent or late induction is associated with progression to severe COVID-19.19, 20, 21 Moreover, anti-type I IFN autoantibodies or genetic alterations of the IFN pathway have been associated with severe COVID-19, underscoring the importance of this pathway for antiviral defense.22,23

The use of synthetic nucleic acids to activate innate, antiviral immune-sensing receptors and to induce the release of type I IFN has been studied in numerous therapeutic contexts.24 The cytosolic RNA receptor RIG-I has proven particularly suitable for such applications. RIG-I is activated by blunt-end double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) with a 5′-triphosphate or 5′-diphosphate,25, 26, 27 and potent specific ligands can be generated by solid-phase synthesis.28 Its activation induces a broad and effective antiviral program that surpasses the effect of recombinant type I IFN alone.29 Since RIG-I is widely expressed in nucleated cells, including tumor cells, and its activation induces potent natural killer (NK) cell responses,30,31 RIG-I ligands have been used in immunotherapy against tumors in mouse models,32 and in phase I/II clinical trials in humans.33 Synthetic RIG-I ligands induce broad antiviral effects,29 and, in previous work, we showed that the stimulation of RIG-I was more effective than the activation of other nucleic acid-sensing receptors such as Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7) or TLR9 in protecting mice from a lethal influenza virus infection.34

In the present study, we investigated the efficacy of a synthetic 5′-triphosphate dsRNA RIG-I ligand (3pRNA) against SARS-CoV-2 in the murine K18-hACE2 (keratin18-human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2) mouse model of COVID-19. Since SARS-CoV-2 does not infect wild-type mice, the virus either needs to be genetically adapted to mice or mice need to be engineered to express human ACE2, as in the K18-hACE2 mouse model (see Renn et al.35 for a review of COVID-19 animal models). The K18-hACE2 mouse model recapitulates key aspects of human COVID-19 disease, such as anosmia, severe lung inflammation, and impaired lung function, but the expression of hACE2 under the keratin18 promoter leads to nonphysiologically high expression of ACE2 in additional tissues such as the brain, resulting in high lethality after exposure to relatively low viral doses.36, 37, 38 In the present study, we found that both prophylactic, systemic administration of the RIG-I ligand 3pRNA, 1–7 days before virus challenge, and therapeutic administration, starting 1 day after infection, substantially ameliorated the clinical course of otherwise lethal infection. Moreover, improved survival was accompanied by a lower viral load in the lungs and in the brain, with the surviving mice developing a SARS-CoV-2-specific neutralizing immunoglobulin G (IgG) response. Our study demonstrates that targeted RIG-I activation is an effective strategy for the short-term prophylactic or therapeutic treatment of SARS-CoV-2 and highlights the potential of the application of specific RIG-I agonists for the immediate treatment and containment of emerging viral infections.

Results

Prophylactic treatment with RIG-I ligand improves the survival of K18-hACE-2 mice challenged with a lethal dose of SARS-CoV-2

K18-hACE2 mice overexpress the hACE2 gene under the control of the Keratin18 promoter, which enables productive infection by SARS-CoV-2 displaying key characteristics of human COVID-19.36 K18-hACE2 mice show a severe course of disease with high lethality even at low viral doses.35

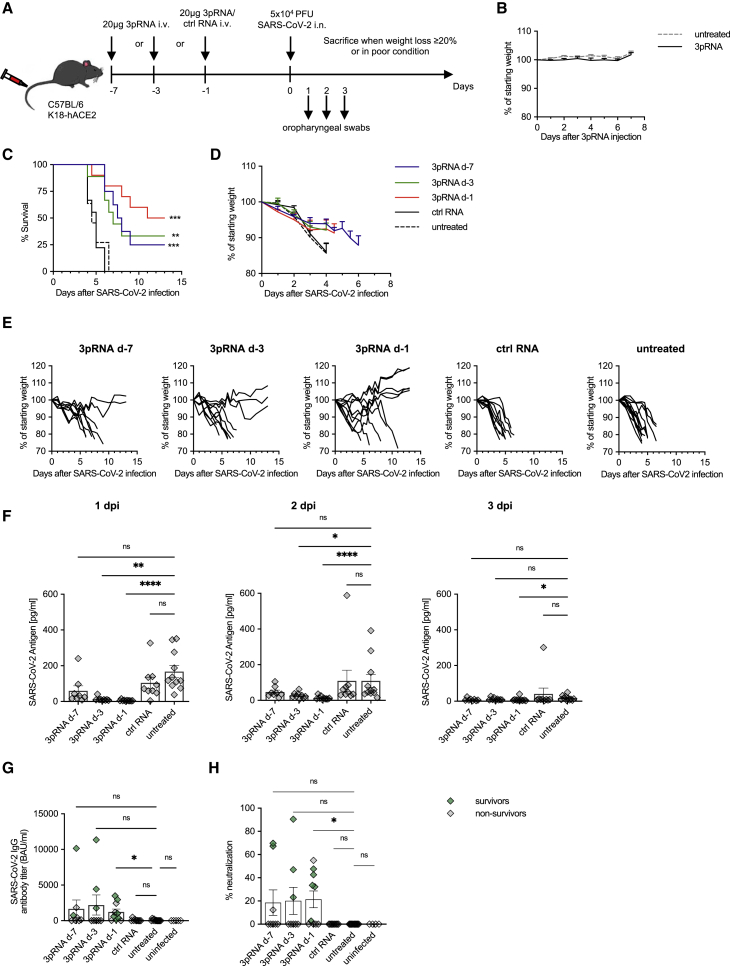

To investigate the protective effects of a selective RIG-I ligand (3pRNA), K18-hACE2 mice were injected intravenously (i.v.) with a single dose of 20 μg 3pRNA or control RNA (CA21) complexed with in vivo jetPEI at 7 days (d-7), d-3, or d-1 before intranasal (i.n.) inoculation with 5 × 104 plaque-forming units (PFU) of SARS-CoV-2 (SARS-CoV-2/human/Germany/Heinsberg-01/2020). Weight loss and clinical manifestations were recorded daily for up to 13 days post-infection (dpi). Mice were euthanized for ethical reasons when they lost more than 20% of their initial body weight or showed overt signs of illness (Figure 1A). The treatment with 3pRNA at this dose did not induce weight loss or other signs of toxicity (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Prophylactic RIG-I stimulation protects mice from lethal SARS-CoV-2 infection

(A) Experimental setup. K18-hACE2wt/tg mice were i.v. injected with 20 μg 3pRNA or control RNA complexed to in vivo jetPEI on the indicated days. On day 0 (d-0), mice were infected intranasally with 5 × 104 PFU SARS-CoV-2 virus. Oropharyngeal swabs were obtained on d-1 to d-3 post-infection (dpi). Disease development and survival were monitored up to twice daily until 13 dpi. (B) Weight development of 3pRNA-treated animals. Plotted are the means ± SEMs of 2 independent experiments (3pRNA n = 8, untreated n = 11). (C–E) Kaplan-Meier curve (C) and (D) weight loss (pooled) of SARS-CoV-2-infected animals. (E) Individual weight loss over time of each SARS-CoV-2 infected mouse until reaching the endpoint criteria or 13 dpi. (F) SARS-CoV-2 antigen ELISA of oropharyngeal swab material on 1 dpi to 3 dpi. (G) Quantification of anti-SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG antibody titers in sera of SARS-CoV-2-infected animals collected at their individual time of death or 13 dpi. (H) Percentage of inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 S1/RBD-hACE2 interaction by sera of SARS-CoV-2-infected animals collected at their individual time of death or 13 dpi. (C, D, F–H) Plotted are the means ± SEMs (3pRNA d-7 n = 8, 3pRNA d-3 n = 9, 3pRNA d-1 n = 10, ctrl RNA d-1 n = 9, untreated n = 11). The data are pooled from 2 independent experiments. The statistical significance was calculated by log rank Mantel-Cox test (B) and the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple testing (F and G). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

SARS-CoV-2-infected mice rapidly and uniformly showed weight loss and signs of disease such as reduced activity, hunched posture, and lethargy. All of them reached the euthanasia criteria by 4.5 to 6 dpi when left untreated (Figures 1C and 1D). Some mice exhibited severe intestinal symptoms such as bowel obstructions or neurological symptoms marked by progressive motor deficits. A single injection of 3pRNA administered d-1 before inoculation with the virus improved the survival rate from 0% (treatment with control RNA) to 50% (Figure 1C). Injection at d-3 or d-7 before infection still improved the survival rate by 25%–30%. Some of the 3pRNA-treated mice that eventually succumbed to SARS-CoV-2 infection still showed slower weight loss and a delayed onset of other symptoms, resulting in a right shift of the Kaplan-Meier curve (Figure 1C). Surviving animals maintained or increased their weight and did not show any signs of disease for the duration of the experiment (Figure 1E).

To monitor viral replication, oropharyngeal swabs were taken 1–3 dpi. SARS-CoV-2 viral antigens were quantified by ELISA (Figure 1F), and viral RNA was quantified by qPCR (Figure S1). Pretreatment with 3pRNA d-1 and d-3 (trend for d-7) before infection led to a significant reduction of viral burden 1 day and 2 days after viral challenge (Figures 1F and S1). In contrast, pre-treatment with control RNA had no effect compared to untreated animals. At 3 days after viral challenge, viral antigen was no longer detectable in most of the mice (Figure 1F). We then examined the levels of anti-SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG antibody titers in the sera of all of the animals at the time of death (non-surviving mice, marked in black) or at the end of the observation period (day 13, surviving mice, marked in green). 3pRNA-treated mice showed significantly higher anti-SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG antibodies titers post-infection than untreated infected control mice (Figure 1G). SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies also conferred neutralizing activity by blocking the interaction between ACE2 and the Spike protein in vitro (Figure 1H). Of note, the fact that sera were obtained at the time of death or at 13 dpi (surviving mice) limits a comparative analysis of the data.

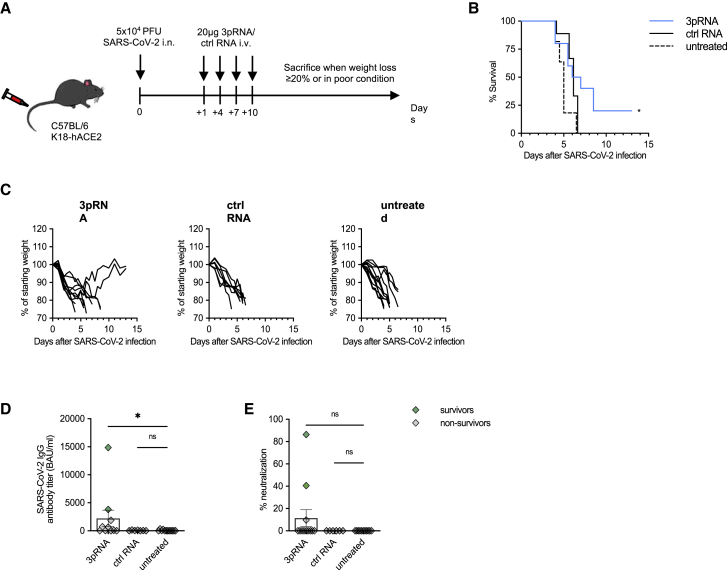

Early therapeutic intervention partially rescues mice from lethal SARS-CoV-2 infection

We then tested whether RIG-I stimulation was beneficial after viral infection had already occurred. K18-hACE2 mice were infected with 5 × 104 PFU SARS-CoV-2, and 20 μg 3pRNA or control RNA were injected i.v. 24 h later and repeated on 4, 7, and 10 dpi (Figure 2A). In contrast to mice treated with control RNA and untreated control animals, 25% of mice treated with 3pRNA recovered from the initial weight loss and survived (Figures 2B and 2C). Moreover, the surviving mice developed a neutralizing SARS-CoV-2-specific antibody response (Figures 2D and 2E).

Figure 2.

Therapeutic intervention with RIG-I ligand confers an intermediate level of protection against lethal SARS-CoV-2 infection in mice

(A) Experimental setup. K18-hACE2wt/tg mice were infected intranasally with 5 × 104 PFU SARS-CoV-2. One day post-infection, mice were i.v. injected with 20 μg 3pRNA or control RNA complexed to in vivo jetPEI. Injection of 3pRNA or control RNA was repeated on 4, 7, and 10 dpi. Disease development and survival were monitored up to twice daily until 13 dpi. (B and C) Kaplan-Meier curve of SARS-CoV-2-infected animals (B). (C) Individual weight loss development of each mouse until they reached the endpoint criteria or 13 dpi. (D) Quantification of anti-SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG antibody titers in the sera of SARS-CoV-2-infected animals collected on their individual time point of death or 13 dpi. (E) Percentage of inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 S1/RBD-hACE2 interaction by the sera of SARS-CoV-2-infected animals collected on their individual time point of death or 13 dpi. Plotted are the means ± SEMs (3pRNA n = 10, ctrl RNA n = 9, untreated n = 11). The data are pooled from 2 independent experiments. The statistical significance was calculated by log rank Mantel-Cox test (B) and non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple testing (D and E). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

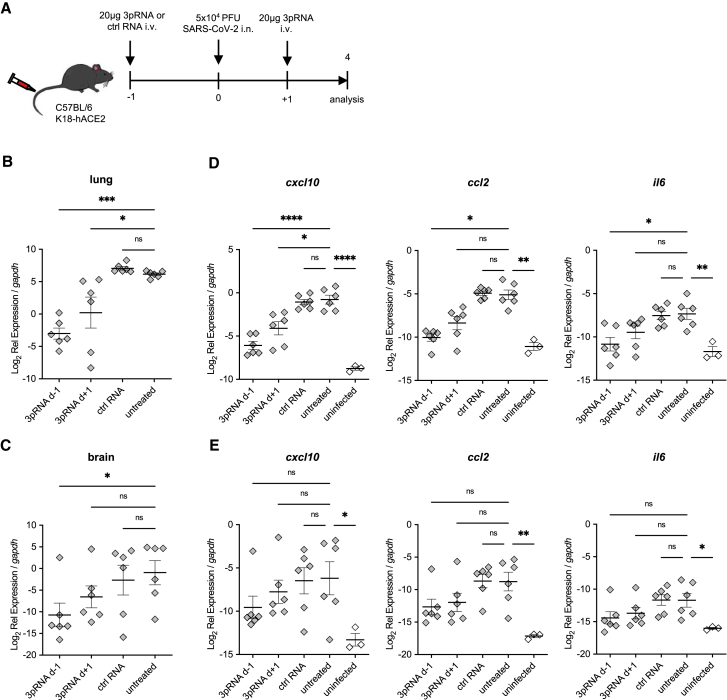

3pRNA treatment reduces viral load and inflammation

Next, we analyzed the viral load in the lungs and the brains of mice i.v. injected with 20 μg 3pRNA either 1 day before (prophylactic) or 1 day after (therapeutic) i.n. inoculation with SARS-CoV-2. Mice were sacrificed and their lungs and brains were prepared on 4 days after viral challenge (Figure 3A). Prophylactic 3pRNA treatment significantly reduced the viral burden (Figures 3B and 3C) in the lungs and brains as well as inflammation in lung tissue as indicated by a diminished expression of the chemokines C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10) and C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) and the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6) (Figure 3D). The number of viral RNA copies as well as the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the brain (Figures 3C and 3E) of the mice were overall lower than in the lungs (Figures 3B and 3D) at 4 days after viral challenge.

Figure 3.

Reduced viral burden and inflammation in SARS-CoV-2-infected lungs upon RIG-I ligand treatment

(A) Experimental setup. K18-hACE2wt/tg mice were i.v. injected with 20 μg 3pRNA or control RNA complexed to in vivo jetPEI 1 day before (3pRNA d-1) or after (3pRNA d+1) infection. Mice were infected intranasally with 5 × 104 PFU SARS-CoV-2 and sacrificed 4 dpi. (B and C) SARS-CoV-2 viral burden in the lungs (B) and in the brain (C) at 4 dpi. (D and E) Cytokine expression in the lungs (D) and brain (E) at 4 dpi. For (B)–(E), expression was quantified by qPCR relative to murine gapdh expression. Plotted are the means ± SEMs (n = 6, uninfected n = 3). The statistical significance was calculated by 1-way ANOVA (Welch) with Dunnett’s T3 multiple testing, when the data were lognormally distributed; otherwise, a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple testing was applied. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

We also analyzed the viral burden in the mice shown in Figure 1 from which organs were taken at the time of death or at the end of the observation period. Surviving animals from all 3pRNA-treated groups and non-surviving mice from the 3pRNA-treated d-1 group showed a significant reduction in viral RNA in the lungs (Figure S2A). However, in the brain, this was seen only for surviving animals from the 3pRNA-treated d-1 group, with a similar tendency for the 3pRNA-treated d-3 and d-7 animals (Figure S2B), underscoring the importance of CNS infection in this mouse model. Accordingly, in untreated animals, the viral load in the brain was higher at the time of death (4.5 to 6 dpi) than at 4 dpi, indicating an aggravation of viral replication in the brain during the course of the infection (compare Figures S2B and S3C).

Immunohistochemical staining of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid in lung and brain sections correlated with the results of qPCR analysis when scored by three independent scientists in a blinded fashion (Figures S2C and S2D). Histological scores for the nucleocapsid staining were lower in the lungs of all of the 3pRNA-treated animals and in the brains of the surviving 3pRNA-treated mice, but they did not reach significance (Figures S2E and S2F).

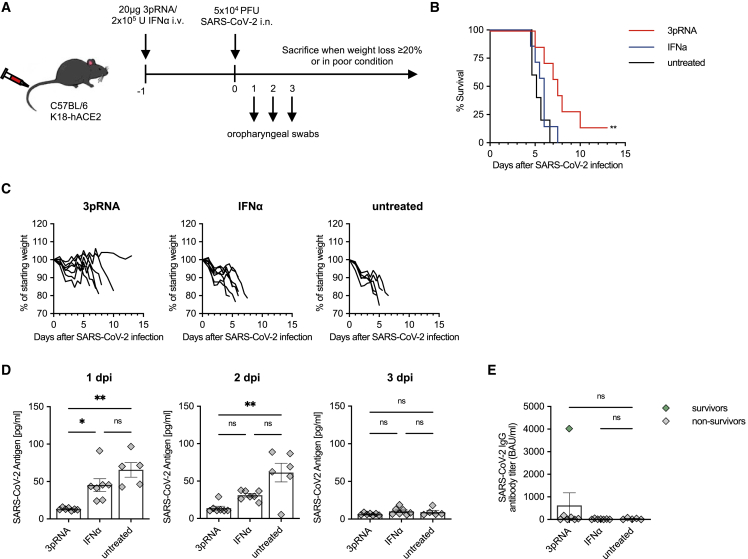

3pRNA confers superior protection compared to recombinant type I IFN

Intravenous injection of 3pRNA induces significant amounts of IL-6, CXCL10, and type I (α/β) and type II (γ) IFN (Figure S3). Since treatment of COVID-19 with recombinant type I IFN has already been studied in clinical trials, we compared the antiviral efficacy of 3pRNA to high-dose recombinant universal IFN-α (IFN-a/d; 2 × 105 U, 877 ng), which is equivalent to the IFN levels observed after 3pRNA treatment and has been used by others.39 In our experimental setting, prophylactic treatment with recombinant universal IFN-α d-1 before infection did not improve the survival after SARS-CoV-2 infection, in contrast to 3pRNA treatment (Figures 4A–4C). Moreover, only 3pRNA significantly reduced the amount of viral antigen (Figure 4D) and viral RNA (Figure S4) in the upper respiratory tract on 1 and 2 dpi, and it reduced the viral burden in the lungs at the time point of death (Figure S4B). However, for recombinant universal IFN-α, a weaker, non-significant trend could still be observed in the oropharyngeal swabs. Nonetheless, in direct comparison, the effect of 3pRNA treatment was significantly better than recombinant IFN-α (Figures 4D, S4A, and S4B). Surviving animals in the 3pRNA group developed SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG antibodies (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

RIG-I stimulation is superior to type I interferon (IFN) at protecting mice from lethal SARS-CoV-2 infections

(A) Experimental setup. K18-hACE2wt/tg mice were i.v. injected with 20 μg 3pRNA complexed to in vivo jetPEI or 2 × 105 U recombinant universal IFN-α (A/D) 1 day before infection. Mice were infected intranasally with 5 × 104 PFU SARS-CoV-2. Oropharyngeal swabs were obtained on 1 to 3 dpi. Disease development and survival were monitored up to twice daily until 13 dpi. (B) Kaplan-Meier curve of SARS-CoV-2-infected animals. (C) Individual weight loss development of each mouse until its individual time of death or 13 dpi. (D) SARS-CoV-2 antigen ELISA in oropharyngeal swab material on 1 to 3 dpi. (E) Quantification of anti-SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG antibody titers in the sera of SARS-CoV-2-infected animals. Plotted are the means ± SEMs (3pRNA and IFN-α n = 7, untreated n = 5). The statistical significance was calculated by log rank Mantel-Cox test (B) and non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple testing (D and E). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

Discussion

Innate antiviral defense is triggered upon immune sensing of viral nucleic acids. The betacoronavirus SARS-CoV-2 uses multiple mechanisms to efficiently escape from innate recognition of its viral RNA.40 In the present study, we evaluated whether prophylactic and therapeutic activation of innate antiviral immunity through i.v. administration of a specific RIG-I ligand protects mice from SARS-CoV-2 infection. Using the murine K18-hACE2 mouse model of COVID-19, we show that synthetic RIG-I agonists drastically reduce viral replication not only in the upper and lower airways of SARS-CoV-2 infected mice but also in the CNS. Prophylactic treatment even up to 7 days before infection substantially decreased morbidity and mortality compared to untreated animals. All RIG-I agonist-treated mice that survived the infection developed neutralizing antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, showing that this exogenous, supraphysiological activation of innate antiviral immunity does not negatively interfere with the development of an effective adaptive immune response. Here, it is important to note that the mouse model in this study exhibits 100% lethality upon infection, while for SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans the infection fatality rate has remained below 1%.41,42 Thus, it is very likely that the results presented in this study largely underestimate the protective and therapeutic effect of prophylactic RIG-I ligand treatment against SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans.

Other studies have proposed stimulation of the innate immune system as an approach for SARS-CoV-2 treatment. Notably, recombinant pegylated (PEG)-IFNa2,43 PEG-IFNb44 or PEG-IFNL45 treatment were shown to accelerate the recovery of COVID-19 patients in Phase II trials. However, we and others show that RIG-I ligands confer greater protection and therapeutic benefit than recombinant type I IFN in the K18-hACE2 mouse model.39 One reason may be that 3pRNA offers the additional advantage that the entire physiological spectrum of type I and III IFNs are induced and that the profile of expressed antiviral effectors is broader than what is induced by type I IFN alone.29 Similar to RIG-I, ligands for stimulator of interferon genes (STING), another receptor of the innate immune system, yielded better results than recombinant IFN in protecting K18-hACE2 mice from lethal SARS-CoV-2 infections,46,47 indicating that direct activation of innate antiviral immune sensing receptors may be generally superior to recombinant IFNs in the context of viral infections. Moreover, treatment with recombinant IFN frequently leads to the generation of autoantibodies against the administered type I IFN, which reduces the efficacy of the therapy.48 In this context, it is important to note that patients with autoantibodies against IFNs have also been reported to be more susceptible to severe COVID-19.23 Because these patients usually carry only autoantibodies against either IFN-α or IFN-β, simultaneous stimulation of different physiological forms of type I and III IFN by therapeutic RIG-I activation would potentially still be quite effective. The physiologic induction of IFNs by RIG-I may also have the advantage of inducing less anti-type I IFN autoantibodies, because endogenous IFN is not altered in terms of its amino acid sequence and glycosylation pattern or by pegylation, as this is the case for the recombinant IFNs.49 Moreover, the absence of anti-type I IFN autoantibodies is expected to offer an advantage for future immune responses against other viral infections.

The therapeutic treatment with recombinant IFN yields the best effects when applied soon after the infection, whereas late treatment can even contribute to increased inflammation and may have detrimental effects.50 Given the short therapeutic window in the K18-hACE2 mouse model with the mice succumbing 4 days to 6 days after infection, the rescue of 25% of mice with a treatment 24 h after infection shows that 3pRNA treatment could also be used in a therapeutic setting.

Consistent with our data, in a recent publication, Mao et al. have demonstrated efficacy of RIG-I agonists against SARS-CoV-2 infections.39 While our study used 5′-triphosphate blunt-end dsRNA, they used a 5′-triphosphate stem loop RNA. Nonetheless, both studies showed a reduction in viral load and increased survival of K18-hACE2 mice with comparable doses of RIG-I agonist (20 μg versus 15 μg). However, it is important to note that despite using the same K18-hACE2 mouse model, these two studies differ in the virus dose used for infection and in the resulting lethality. This needs to be considered when comparing quantitative efficacies of different compounds and prophylactic treatment regimens. Both studies used 5 × 105 U of the same recombinant universal IFN-α. While this dose conferred protection when given 4 h after an infection with 5 × 102 PFU SARS-CoV-2 in the Mao et al. study, it failed to do so when given 1 day before infection with the 100-times higher viral dose used in our study. Furthermore, in line with our previous findings on RIG-I-mediated protection against influenza virus infection,34 Mao et al. confirmed that the efficacy of the RIG-I ligands depends on a functional type I IFN system.39

Bifunctional dsRNAs activating RIG-I and silencing genes by serving as small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) have been used in the past to treat tumors, such as melanoma32 or viral infections such as influenza A51 or hepatitis B.52 Because targeting of essential RNAs of SARS-CoV-2 with siRNA has already shown protection in the K18-hACE2 model,53 the approach of bifunctional siRNAs is a promising approach to further increasing antiviral activity.

While vaccines will likely continue to be the most important weapon against SARS-CoV-2, the capability of RIG-I agonists to induce protection in immunocompromised hosts and their effectiveness against variants of concern39 would help to fill important niches, such as antiviral prophylaxis in organ transplant recipients or the treatment of front-line healthcare workers exposed to emerging variants. In our study, the reduced morbidity and mortality after prophylaxis, even when administered 7 days before infection, show that RIG-I agonists induce a relatively long-lasting antiviral state, which would allow for a clinically feasible weekly pre-exposure prophylaxis in high-exposure environments.

Moreover, the ability of RIG-I ligands to reduce viral load and thereby the inflammation in the lungs in response to therapeutic treatment could be used to treat high-risk COVID-19 patients immediately after a positive qPCR diagnosis to reduce the likelihood of hospitalization or death. Because double-stranded RIG-I agonists have already been tested in Phase I/II clinical studies for oncologic indications (NCT03739138, NCT0306502),33 trials for the prophylaxis or treatment of COVID-19 could swiftly be initiated.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that RIG-I agonist-mediated antiviral prophylaxis has great potential in the context of SARS-CoV-2, but it is also a promising approach against newly emerging viruses, in which it could be used to limit outbreaks and prevent pandemic spread.

Materials and methods

Mice

B6.Cg-Tg(K18-ACE2)2Prlmn/J (K18-hACE2) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories and bred in-house at the University Hospital of Bonn. Mice of both sexes that were 8–20 weeks old were used throughout the study. All of the mice were housed in individually ventilated cages (IVCs) in groups of up to 5 individuals per cage and maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle at 22°C–25°C temperature and 40%–70% relative humidity under specific-pathogen-free conditions. All of the mice were fed with regular rodent chow and sterilized water ad libitum. All of the procedures used in this study were performed with approval by the responsible animal welfare authority (81-02.04.2019.A433, 81-02.04.2021.A267 LANUV NRW).

Virus stock

The SARS-CoV-2 virus stock used in this study was isolated from a throat swab isolate of a SARS-CoV-2-infected patient at the University of Bonn, Germany, in March 2020 (SARS-CoV-2/human/Germany/Heinsberg-01/2020). The virus was passaged in VeroE6 cells, and the viral titers were determined using a plaque assay as described by Koenig et al.54

3pRNA synthesis

Synthetic 3pRNA with a published sequence (3pGFP2)55 was chemically synthesized by solid-phase synthesis as described previously.28 CA21-control RNA (5′-CACACACACACACACACACAC-3′) was synthesized by Biomers (Ulm, Germany).

In vivo RIG-I and IFN-α stimulation

3pRNA or control RNA (CA21) was complexed with in vivo jetPEI (N/P ratio 6) according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Polyplus, Illkirch, France). At the indicated time points, mice were injected i.v. with 20 μg RNA or 2 × 105 U human recombinant universal IFN-α(A/D) (R&D Systems, Wiesbaden, Germany) into the tail vein.

SARS-CoV-2 mouse infection

All of the SARS-CoV-2 experiments were performed in a Biosafety Level 3 (BSL-3) facility at the University Hospital Bonn. K18-hACE2 transgenic mice were lightly anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine before 5 × 104 PFU SARS-CoV-2 virus was pipetted on mice noses and subsequently inhaled by the animal. On 1 dpi to 3 dpi, oropharyngeal swabs were obtained using minitips and placed in a 1-mL UTM medium (360C, COPAN, Hain Lifescience GmbH, Nehren, Germany). Viral antigen in the oropharyngeal swabs was quantified with ELISA according to the manufacturer’s protocol (SARS-CoV-2-Antigen-ELISA, Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany). Following infection, weight loss and survival were monitored up to twice daily for 13 days. Endpoint criteria were ≥20% weight loss, lethargy, motor deficits, and high respiratory rates.

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from mouse lung and brain tissues using TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After a DNase I digestion step (Thermo Fisher Scientific), reverse transcription was carried out with RevertAid reverse transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

The resulting cDNA was used for the amplification of selected genes by qPCR using EvaGreen QPCR-mix II (ROX) (Biobudget, Krefeld, Germany) on a Quantstudio 5 machine (Thermo Fisher Scientific). SARS-CoV-2 envelope RNA expression was determined using the commercial E_Sarbeco primer sets (10006888 and 10006890, Integrated DNA Technologies [IDT], Leuven, Belgium). Cytokine expression was determined using the following primer sets (ordered from IDT): cxcl10 fwd CCCACGTGTTGAGATCATTGCC, cxcl10 rev GTGTGTGCGTGGCTTCACTC, il6 fwd TGTGACATCAAGGACCTGCC, il6 rev CTGAGTCACCTGCTACACGC, ccl2 fwd CAC TCA CCT GCT GCT ACT CA, ccl2 rev GCT TGG TGA CAA AAA CTA CAG C. For tissues, the relative expression values were normalized to murine gapdh (fwd 5′-CTGCCCAGAACATCATCCCT-3′, rev 5′-TCATACTTGGCAGGTTTCTCCA-3′), and average values from duplicates were shown as 2−ΔCq.

IgG ELISA

The presence of SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG antibodies in the sera of mice was quantified using ELISA (QuantiVac, Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, with the exception that the anti-human anti-IgG antibody in the kit was exchanged for a goat anti-mouse IgG-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate (115-035-062, Jackson Immuno Research, London, UK), 1:5,000 in 0.5% BSA in PBS. Neutralizing antibodies were quantified with a pseudo-SARS-CoV-2 neutralization ELISA (NeutraLISA, Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany).

Statistical analysis

All of the statistical tests were calculated using Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Survival curves were analyzed using the log rank Mantel-Cox test. The analysis of weight change was determined by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). All of the results are expressed as means ± SEMs and were corrected for multiple comparisons. The data were checked for log-normal distribution with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Log-normally distributed data were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA, and other data were analyzed using a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test, as indicated in the figure legends.

Acknowledgments

We thank Meghan Campbell for her critical reading of this manuscript, Maike Adamson for helpful scientific discussion, and Hendrik Streeck for the use of the BSL3 facility at the Institute of Virology. We thank Patrick Müller, Christian Hagen, Vanessa Barabasch, Sandra Ferring-Schmitt, and Janett Wieseler for expert technical assistance. This study was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy–EXC2151–390873048, of which E.B., G.H., H.K., and M.S. are members, and by the DFG Project-ID 369799452 – TRR237, to E.B., G.H., B.M.K., H.K., and M.S., and Project-ID 397484323 –TRR259, to G.H. It was further supported by the German Center for Infectious Diseases (DZIF), grant nos. TTU 01.806 and 01.810 (to B.M.K.) and TTU 07.834_00 (to G.H.). C.G. is the recipient of a scholarship from the Bonner Promotionskolleg “NeuroImmunology” (BonnNi, University of Bonn). M.R. is funded by the Deutsche Krebshilfe through a Mildred Scheel Nachwuchszentrum grant (grant no. 70113307). The graphical abstract accompanying this manuscript was created with BioRender.com.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, G.H. Formal analysis, S.M., M.R., and E.B. Investigation, S.M., C.G., and M.R. Methodology, B.M.K., H.K., M.S., M.R., E.B., and G.H. Resources, B.M.K., H.K., M.S., and G.H. Visualization, S.M., M.R., E.B., and G.H. Writing – original draft, S.M., M.R., E.B., and G.H. Writing – review & editing, S.M., B.M.K., C.G., H.K., M.S., M.R., E.B., and G.H. Supervision, B.M.K., M.R., and G.H. Project administration, M.R., E.B., and G.H. Funding acquisition, G.H.

Declaration of interests

M.S. and G.H. are inventors on a patent on RIG-I ligands.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2022.02.008.

Supplemental information

Document S2. Article plus supplemental information

References

- 1.Zhou P., Yang X.-L., Wang X.-G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H.-R., Zhu Y., Li B., Huang C.-L., et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J., Zhao X., Huang B., Shi W., Lu R., et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen X., Laurent S., Onur O.A., Kleineberg N.N., Fink G.R., Schweitzer F., Warnke C. A systematic review of neurological symptoms and complications of COVID-19. J. Neurol. 2021;268:392–402. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-10067-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta A., Madhavan M.V., Sehgal K., Nair N., Mahajan S., Sehrawat T.S., Bikdeli B., Ahluwalia N., Ausiello J.C., Wan E.Y., et al. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020;26:1017–1032. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0968-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alwan N.A. The road to addressing Long Covid. Science. 2021;373:491–493. doi: 10.1126/science.abg7113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hillis S.D., Unwin H.J.T., Chen Y., Cluver L., Sherr L., Goldman P.S., Ratmann O., Donnelly C.A., Bhatt S., Villaveces A., et al. Global minimum estimates of children affected by COVID-19-associated orphanhood and deaths of caregivers: a modelling study. Lancet. 2021;398:391–402. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01253-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dong Y., Shamsuddin A., Campbell H., Theodoratou E. Current COVID-19 treatments: rapid review of the literature. J. Glob. Health. 2021;11:10003. doi: 10.7189/jogh.11.10003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dougan M., Nirula A., Azizad M., Mocherla B., Gottlieb R.L., Chen P., Hebert C., Perry R., Boscia J., Heller B., et al. Bamlanivimab plus etesevimab in mild or moderate covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;385:1382–1392. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2102685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernal A.J., da Silva M.M.G., Musungaie D.B., Kovalchuk E., Gonzalez A., Reyes V.D., Martín-Quirós A., Caraco Y., Williams-Diaz A., Brown M.L., et al. Molnupiravir for oral treatment of covid-19 in nonhospitalized patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;386 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116044. NEJMoa2116044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beigel J.H., Tomashek K.M., Dodd L.E., Mehta A.K., Zingman B.S., Kalil A.C., Hohmann E., Chu H.Y., Luetkemeyer A., Kline S., et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of covid-19 — Final report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:1813–1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xia H., Cao Z., Xie X., Zhang X., Chen J.Y.-C., Wang H., Menachery V.D., Rajsbaum R., Shi P.-Y. Evasion of type I interferon by SARS-CoV-2. Cell Rep. 2020;33:108234. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lei X., Dong X., Ma R., Wang W., Xiao X., Tian Z., Wang C., Wang Y., Li L., Ren L., et al. Activation and evasion of type I interferon responses by SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:3810. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17665-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y., Guo D. Molecular mechanisms of coronavirus RNA capping and methylation. Virol. Sin. 2016;31:3–11. doi: 10.1007/s12250-016-3726-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krafcikova P., Silhan J., Nencka R., Boura E. Structural analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 methyltransferase complex involved in RNA cap creation bound to sinefungin. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:3717. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17495-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schuberth-Wagner C., Ludwig J., Bruder A.K., Herzner A.-M., Zillinger T., Goldeck M., Schmidt T., Schmid-Burgk J.L., Kerber R., Wolter S., et al. A conserved histidine in the RNA sensor RIG-I controls immune tolerance to N1-2O-methylated self RNA. Immunity. 2015;43:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daffis S., Szretter K.J., Schriewer J., Li J., Youn S., Errett J., Lin T.-Y., Schneller S., Zust R., Dong H., et al. 2′-O methylation of the viral mRNA cap evades host restriction by IFIT family members. Nature. 2010;468:452–456. doi: 10.1038/nature09489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bartok E., Hartmann G. Immune sensing mechanisms that discriminate self from altered self and Foreign nucleic acids. Immunity. 2020;53:54–77. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lokugamage K.G., Hage A., de Vries M., Valero-Jimenez A.M., Schindewolf C., Dittmann M., et al. Type I interferon susceptibility distinguishes SARS-CoV-2 from SARS-CoV. J. Virol. 2020;94:e01410–e01420. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01410-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee J.S., Shin E.-C. The type I interferon response in COVID-19: implications for treatment. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020;20:585–586. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-00429-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hadjadj J., Yatim N., Barnabei L., Corneau A., Boussier J., Smith N., Péré H., Charbit B., Bondet V., Chenevier-Gobeaux C., et al. Impaired type I interferon activity and inflammatory responses in severe COVID-19 patients. Science. 2020;369:718–724. doi: 10.1126/science.abc6027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lucas C., Wong P., Klein J., Castro T.B.R., Silva J., Sundaram M., Ellingson M.K., Mao T., Oh J.E., Israelow B., et al. Longitudinal analyses reveal immunological misfiring in severe COVID-19. Nature. 2020;584:463–469. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2588-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Q., Bastard P., Liu Z., Pen J.L., Moncada-Velez M., Chen J., Ogishi M., Sabli I.K.D., Hodeib S., Korol C., et al. Inborn errors of type I IFN immunity in patients with life-threatening COVID-19. Science. 2020;370:eabd4570. doi: 10.1126/science.abd4570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bastard P., Rosen L.B., Zhang Q., Michailidis E., Hoffmann H.-H., Zhang Y., Dorgham K., Philippot Q., Rosain J., Béziat V., et al. Autoantibodies against type I IFNs in patients with life-threatening COVID-19. Science. 2020;370:eabd4585. doi: 10.1126/science.abd4585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Junt T., Barchet W. Translating nucleic acid-sensing pathways into therapies. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015;15:529–544. doi: 10.1038/nri3875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goubau D., Schlee M., Deddouche S., Pruijssers A.J., Zillinger T., Goldeck M., Schuberth C., der Veen A.G.V., Fujimura T., Rehwinkel J., et al. Antiviral immunity via RIG-I-mediated recognition of RNA bearing 5’-diphosphates. Nature. 2014;514:372–375. doi: 10.1038/nature13590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hornung V., Ellegast J., Kim S., Brzózka K., Jung A., Kato H., Poeck H., Akira S., Conzelmann K.-K., Schlee M., et al. 5’-Triphosphate RNA is the ligand for RIG-I. Science. 2006;314:994–997. doi: 10.1126/science.1132505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schlee M., Roth A., Hornung V., Hagmann C.A., Wimmenauer V., Barchet W., Coch C., Janke M., Mihailovic A., Wardle G., et al. Recognition of 5’ triphosphate by RIG-I helicase requires short blunt double-stranded RNA as contained in panhandle of negative-strand virus. Immunity. 2009;31:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldeck M., Tuschl T., Hartmann G., Ludwig J. Efficient solid-phase synthesis of pppRNA by using product-specific labeling. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2014;126:4782–4786. doi: 10.1002/anie.201400672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goulet M.-L., Olagnier D., Xu Z., Paz S., Belgnaoui S.M., Lafferty E.I., Janelle V., Arguello M., Paquet M., Ghneim K., et al. Systems analysis of a RIG-I agonist inducing broad spectrum inhibition of virus infectivity. PLOS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003298. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daßler-Plenker J., Paschen A., Putschli B., Rattay S., Schmitz S., Goldeck M., Bartok E., Hartmann G., Coch C. Direct RIG-I activation in human NK cells induces TRAIL-dependent cytotoxicity toward autologous melanoma cells. Int. J. Cancer. 2019;144:1645–1656. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Engel C., Brügmann G., Lambing S., Mühlenbeck L.H., Marx S., Hagen C., Horváth D., Goldeck M., Ludwig J., Herzner A.-M., et al. RIG-I resists hypoxia-induced immunosuppression and dedifferentiation. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2017;5:455–467. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0129-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poeck H., Besch R., Maihoefer C., Renn M., Tormo D., Morskaya S.S., Kirschnek S., Gaffal E., Landsberg J., Hellmuth J., et al. 5′-triphosphate-siRNA: turning gene silencing and Rig-I activation against melanoma. Nat. Med. 2008;14:1256–1263. doi: 10.1038/nm.1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Middleton M.R., Wermke M., Calvo E., Chartash E., Zhou H., Zhao X., Niewel M., Dobrenkov K., Moreno V. LBA16 Phase I/II, multicenter, open-label study of intratumoral/intralesional administration of the retinoic acid–inducible gene I (RIG-I) activator MK-4621 in patients with advanced or recurrent tumors. Ann. Oncol. 2018;29:viii712. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coch C., Stümpel J.P., Lilien-Waldau V., Wohlleber D., Kümmerer B.M., Bekeredjian-Ding I., Kochs G., Garbi N., Herberhold S., Schuberth-Wagner C., et al. RIG-I activation protects and rescues from lethal influenza virus infection and bacterial superinfection. Mol. Ther. 2017;25:2093–2103. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Renn M., Bartok E., Zillinger T., Hartmann G., Behrendt R. Animal models of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 for the development of prophylactic and therapeutic interventions. Pharmacol. Therapeut. 2021;228:107931. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oladunni F.S., Park J.-G., Pino P.A., Gonzalez O., Akhter A., Allué-Guardia A., Olmo-Fontánez A., Gautam S., Garcia-Vilanova A., Ye C., et al. Lethality of SARS-CoV-2 infection in K18 human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 transgenic mice. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:6122. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19891-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winkler E.S., Bailey A.L., Kafai N.M., Nair S., McCune B.T., Yu J., Fox J.M., Chen R.E., Earnest J.T., Keeler S.P., et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection of human ACE2-transgenic mice causes severe lung inflammation and impaired function. Nat. Immunol. 2020;21:1327–1335. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-0778-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng J., Wong L.-Y.R., Li K., Verma A.K., Ortiz M.E., Wohlford-Lenane C., Leidinger M.R., Knudson C.M., Meyerholz D.K., McCray P.B., et al. COVID-19 treatments and pathogenesis including anosmia in K18-hACE2 mice. Nature. 2021;589:603–607. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2943-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mao T., Israelow B., Lucas C., Vogels C.B.F., Gomez-Calvo M.L., Fedorova O., Breban M.I., Menasche B.L., Dong H., Linehan M., et al. A stem-loop RNA RIG-I agonist protects against acute and chronic SARS-CoV-2 infection in mice. J. Exp. Med. 2021;219:e20211818. doi: 10.1084/jem.20211818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y., Grunewald M., Perlman S. Coronaviruses: an updated overview of their replication and pathogenesis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020;2203:1–29. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-0900-2_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Streeck H., Schulte B., Kümmerer B.M., Richter E., Höller T., Fuhrmann C., Bartok E., Dolscheid-Pommerich R., Berger M., Wessendorf L., et al. Infection fatality rate of SARS-CoV2 in a super-spreading event in Germany. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:5829. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19509-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meyerowitz-Katz G., Merone L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of published research data on COVID-19 infection fatality rates. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;101:138–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pandit A., Bhalani N., Bhushan B.L.S., Koradia P., Gargiya S., Bhomia V., Kansagra K. Efficacy and safety of pegylated interferon alfa-2b in moderate COVID-19: a phase II, randomized, controlled, open-label study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;105:516–521. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Darazam I.A., Shokouhi S., Pourhoseingholi M.A., Irvani S.S.N., Mokhtari M., Shabani M., Amirdosara M., Torabinavid P., Golmohammadi M., Hashemi S., et al. Role of interferon therapy in severe COVID-19: the COVIFERON randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:8059. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-86859-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feld J.J., Kandel C., Biondi M.J., Kozak R.A., Zahoor M.A., Lemieux C., Borgia S.M., Boggild A.K., Powis J., McCready J., et al. Peginterferon lambda for the treatment of outpatients with COVID-19: a phase 2, placebo-controlled randomised trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021;9:498–510. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30566-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Humphries F., Shmuel-Galia L., Jiang Z., Wilson R., Landis P., Ng S.-L., Parsi K.M., Maehr R., Cruz J., Morales A., et al. A diamidobenzimidazole STING agonist protects against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Sci. Immunol. 2021;6:eabi9002. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abi9002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li M., Ferretti M., Ying B., Descamps H., Lee E., Dittmar M., Lee J.S., Whig K., Kamalia B., Dohnalová L., et al. Pharmacological activation of STING blocks SARS-CoV-2 infection. Sci. Immunol. 2021;6:eabi9007. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abi9007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Farrell R., Kapoor R., Leary S., Rudge P., Thompson A., Miller D., Giovannoni G. Neutralizing anti-interferon beta antibodies are associated with reduced side effects and delayed impact on efficacy of Interferon-beta. Mult. Scler. 2008;14:212–218. doi: 10.1177/1352458507082066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Antonelli G., Currenti M., Turriziani O., Dianzani F. Neutralizing antibodies to interferon-alpha: relative frequency in patients treated with different interferon preparations. J. Infect. Dis. 1991;163:882–885. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.4.882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang N., Zhan Y., Zhu L., Hou Z., Liu F., Song P., Qiu F., Wang X., Zou X., Wan D., et al. Retrospective multicenter cohort study shows early interferon therapy is associated with Favorable clinical responses in COVID-19 patients. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;28:455–464.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin L., Liu Q., Berube N., Detmer S., Zhou Y. 5’-Triphosphate-Short interfering RNA: potent inhibition of influenza A virus infection by gene silencing and RIG-I activation. J. Virol. 2012;86:10359–10369. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00665-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ebert G., Poeck H., Lucifora J., Baschuk N., Esser K., Esposito I., Hartmann G., Protzer U. 5′ triphosphorylated small interfering RNAs control replication of hepatitis B virus and induce an interferon response in human liver cells and mice. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:696–706.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Idris A., Davis A., Supramaniam A., Acharya D., Kelly G., Tayyar Y., West N., Zhang P., McMillan C.L.D., Soemardy C., et al. A SARS-CoV-2 targeted siRNA-nanoparticle therapy for COVID-19. Mol. Ther. 2021;29:2219–2226. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koenig P.-A., Das H., Liu H., Kümmerer B.M., Gohr F.N., Jenster L.-M., Schiffelers L.D.J., Tesfamariam Y.M., Uchima M., Wuerth J.D., et al. Structure-guided multivalent nanobodies block SARS-CoV-2 infection and suppress mutational escape. Science. 2021;371:eabe6230. doi: 10.1126/science.abe6230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang Y., Ludwig J., Schuberth C., Goldeck M., Schlee M., Li H., Juranek S., Sheng G., Micura R., Tuschl T., et al. Structural and functional insights into 5′-ppp RNA pattern recognition by the innate immune receptor RIG-I. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:781–787. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Document S2. Article plus supplemental information