Abstract

Background

Advances in systemic treatment and in brain imaging have led to a higher incidence of diagnosed brain metastases. In the treatment of brain metastases, stereotactic radiotherapy and radiosurgery, systemic immunotherapy, and targeted drug therapy are important evidence-based options. In this review, we summarize the available evidence on the treatment of brain metastases of the three main types of cancer that give rise to them: non–small-cell lung cancer, breast cancer, and malignant melanoma.

Methods

This narrative review is based on pertinent original articles, meta-analyses, and systematic reviews that were retrieved by a selective search in PubMed. These publications were evaluated and discussed by an expert panel including radiation oncologists, neurosurgeons, and oncologists.

Results

There have not yet been any prospective randomized trials concerning the optimal combination of local stereotactic radiotherapy/radiosurgery and systemic immunotherapy or targeted therapy. Retrospective studies have consistently shown a benefit from early combined treatment with systemic therapy and (in particular) focal radiotherapy, compared to sequential treatment. Two meta-analyses of retrospective data from cohorts consisting mainly of patients with non–small-cell lung cancer and melanoma revealed longer overall survival after combined treatment with focal radiotherapy and checkpoint inhibitor therapy (rate of 12-month overall survival for combined versus non-combined treatment: 64.6% vs. 51.6%, p <0.001). In selected patients with small, asymptomatic brain metastases in non-critical locations, systemic therapy without focal radiotherapy can be considered, as long as follow-up with cranial magnetic resonance imaging can be performed at close intervals.

Conclusion

Brain metastases should be treated by a multidisciplinary team, so that the optimal sequence of local and systemic therapies can be determined for each individual patient.

cme plus

This article has been certified by the North Rhine Academy for Continuing Medical Education. Participation in the CME certification program is possible only over the internet at cme.aerztebatt.de. The deadline for submission is 11 November 2022.

Patients with brain metastases, if untreated, have a median survival time of approximately one month (e1). Lung cancer, breast cancer, and malignant melanoma are the most common causes of brain metastases, accounting for 67–80% of the total (e2). Advances in neuroimaging, as well as new treatments, particularly targeted and immunotherapeutic drugs, have led both to longer overall survival (OS) and to an increasing incidence of brain metastases (e2– e4). As a result, the median survival of patients with brain metastases rose from five to seven months from 1986–1999 to 2010–2020 (e4). Traditionally, treatment consisted mainly of neurosurgical resection, particularly of solitary metastases with critical space-occupying effect (e5), whole-brain radiation therapy (WBRT), and best supportive care. Further currently available options include stereotactic radiotherapy (local irradiation in multiple fractions) and radiosurgery (RS, i.e., local irradiation in a single session), and new forms of personalized systemic treatment, alongside classic chemotherapy (e6). When used to treat selected cases, these immune therapies and targeted therapies yield markedly higher response rates than classic chemotherapy, for both extra-and intracranial lesions. Predictive molecular markers from tissue and blood can be used to estimate probability of a response (e7).

The optimal multimodal treatment of brain metastases presents a particularly acute challenge at present. In randomized trials, radiosurgery without additional whole-brain radiation therapy led to lasting control of metastases with the same or better OS (e8, e9). These trials, however, generally included patients of heterogeneous tumor histology, and they were performed in an era before effective systemic treatment was introduced. Targeted drugs and immunotherapeutic drugs are likewise evidence-based, standard therapies at present, but, in their approval studies, patients with symptomatic brain metastases were often specifically excluded. High activity in the brain was shown only for certain drugs in secondary analyses. A potential breach in the integrity of the blood-brain barrier and the blood-tumor barrier by radiotherapy is the theoretical basis for improved efficacy, in particular for drugs that ordinarily do not reach the central nervous system (CNS), or do so only to a limited extent (e10). This article provides an overview of the combination of these new systemic and radiooncological treatment options for brain metastases of the most common kinds.

Methods

This narrative review is based on publications in English retrieved by a selective search in PubMed, including original articles, meta-analyses, and systematic reviews. The search was for studies on brain metastases of non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), malignant melanoma, and breast cancer that were treated with immunotherapy and/or targeted therapy combined with radiotherapy. Both retrospective and prospective studies were included. They were evaluated by an expert panel consisting of specialists in radiation oncology, neurosurgery, and oncology. The case numbers, radiotherapeutic methods, types of systemic treatment, toxicity, intracranial responses, and overall survival were all considered in the analysis.

Focal radiotherapy for brain metastases

For patients with limited cerebral metastatic disease (up to four brain metastases with a maximal diameter of 4 cm) and without marked clinical manifestations, radiosurgery is the radiotherapeutic method of choice. In radiosurgery, an equivalent radiotherapeutic dose that is much higher than in traditional WBRT enables long-term local tumor control in 70-90% of patients, even in those with radioresistant tumors, such as melanoma or renal-cell carcinoma (e11-e13). The high spatial precision (figure) of this form of radiotherapy accounts for its favorable side-effect profile; radiation necrosis is a common side effect, appearing after up to one-quarter of all treatments (e14). Radiosurgery alone, i.e., without prior WBRT, is the current standard of treatment, based on the findings of multiple randomized trials (e9, e15). Even though RS alone, compared to RS combined with WBRT, is more often followed by distant cerebral progression (i.e., the appearance of one or more new cerebral metastases outside the treated areas), this is not associated with any worsening of overall survival (e9). The patient’s neurocognitive function is better preserved without WBRT (e16). Follow-up with cranial MRI (cMRI) every 2–3 months is mandatory, so that any new brain metastases can be detected early and treated with either salvage RS or WBRT.

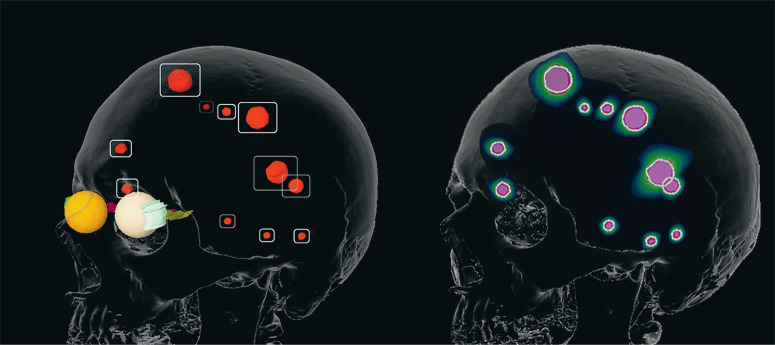

Figure.

Treatment planning for stereotactic irradiation in a patient with 11 brain metastases (target volumes, left; dose distribution, right).

Yamamoto et al. reported that radiosurgery alone is a treatment option even when there are more than four metastases: in their prospective observational study, the OS of treated patients with 5–10 metastases was no worse than that of patients with 2–4 metastases (1194 patients total) (e17).

One may conclude that radiosurgery alone is a solid therapeutic alternative to WBRT for selected patients with a limited number of metastases and a limited total volume of metastatic tumor.

The surgical resection of brain metastases is also an important tool for local therapy, particularly for large, solitary masses that are symptomatic and surgically accessible, including those located in the posterior fossa (e5, e18). In such cases, it is also important to treat peritumoral cerebral edema (which is largely of vasogenic origin, resulting from a breach in the blood-brain barrier) with drugs, particularly cortico-steroids (e18).

Treatment-associated neurocognitive changes

Most patients who have undergone WBRT suffer a worsening of their neurocognitive function several months after treatment; typically, some degree of functional compromise is already present because of the brain metastasis or metastases themselves (e19). Further deterioration affects these patients’ activities of daily living and their quality of life (e20), produce stress for their families, and limit the benefit of the life-prolonging effect of WBRT, which is often very limited (e21).

The cognition-related neurotoxicity of WBRT is markedly worse than that of radiosurgery alone (e22), especially when structures that are particularly vulnerable in terms of cognitive function, such as the hippocampus, are not specifically spared (e23, e24). A randomized trial revealed a markedly higher likelihood of deficits in learning and memory after RS + WBRT (52%) compared to RS alone (24%) (e19). Thus, the use of RS without WBRT, including as part of combination therapy, can lessen cognition-related neurotoxicity.

Low neurotoxicity is also a feature of certain types of chemotherapy and of other systemic treatments, e.g., T-cell-mediated immunotherapy (e25, e26).

Non-small-cell lung cancer

Systemic treatment alone

With regard to systemic treatment, NSCLC with an activating mutation (EGFR, ALK, ROS1, BRAF) can be treated with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), while NSCLC without such a mutation cannot. Most Phase 3 trials of targeted TKI have had specific endpoints for brain metastases (table 1). Higher intracranial response rates have been shown for osimertinib, a third-generation EGFR- and ALK-inhibitor, than for first-generation TKI (1). A further benefit of TKI therapy is that it can prevent the appearance of new brain metastases. It has been shown that fewer new brain metastases arise under treatment with third-generation TKI than with first-generation TKI (4.6% with alectinib vs. 31.5% with crizotinib; 5% with osimertinib vs. 18% with a first-generation TKI) (1, 2).

Table 1. Studies of targeted therapy or immunotherapy as the sole treatment of brain metastases.

| Reference | Study type | Study population | Treatment |

Toxicity (grade 3–4) |

Intracranial response rate, extracranial response rate, intracranial control rate* |

Median PFS | median OS |

| Tawbi 2018 (25) Tawbi 2019 (26) |

prospective | melanoma (n = 94) |

ipilimumab plus nivolumab | 55% | 52% 47% 58.4% |

6 m: 64.2% 9 m: 59.5% |

6 m: 92.3% 9 m: 82.8% 12 m: 81.5% |

| Davies 2017 (27) | prospective | melanoma (n = 108) |

dabrafenib plus trametinib | 48% | 44–59% 41–75% 78–88% |

4.2 –7.2 m 6 m: 13–73% |

24.3 m |

| Reungwetwattana 2019 (1) | prospective | NSCLCEGFR-mut (n = 128) |

osimertinib | 34% | 91% 77% not reported |

18.9 m | 38.6 m |

| Schuler 2016 (30) | prospective | NSCLC EGFR-mut (n = 81) |

afatinib | 46.2% | 82.1% not reported 19–25% |

8.2 m | 13.3 m |

| Gadgeel 2018 (2) | prospective | NSCLC ALK-mut (n = 64) |

alectinib | 41% | 86% not reported not reported |

9.6 m | not yet reached |

| Goldberg 2016 (4) | prospective | NSCLC PD-L1-pos (n = 18) |

pembrolizumab | 30% | 33% 33% not reported |

3.0–7.0 m | 7.7 m |

| Bachelot 2013 (14) | prospective | breast CaHER2-pos (n = 45) |

lapatinib plus capecitabine | 49% | 57% not reported not reported |

5.5 m | 17.0 m |

| Lin 2020 (15) | prospective | breast CaHER2-pos (n = 291) |

tucatinib plus trastuzumab plus capecitabine | 55% | 41% not reported not reported |

9.9 m | 18.1 m1 year: 70.1% |

| Bartsch 2015 (16) | retrospektiv | breast CaHER2-pos (n = 10) |

trastuzumabemtansin | 10% | 70% 80% not reported |

5.0 m | 8.5 m |

| Modi 2020 (17) | prospective | breast CaHER2-pos (n = 24) |

trastuzumabderuxtecan | 50% | 58% not reported not reported |

16.4 m | not yetreached |

* conrol rate: response and stabilization

ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; Ca, cancer; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor; m, months; mut, mutation;

NSCLC, non-small-celllung cancer; OS, overall survival; PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand protein 1; PFS, progression-free survival

For patients without an activating mutation, only very limited data are available on monotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) or chemotherapy. There have been a few small-scale trials of chemotherapy alone for patients with asymptomatic brain metastases, but the results are difficult to interpret because the trials were terminated early (3). A phase 2 trial of treatment with pembrolizumab alone in 18 patients with asymptomatic lung cancer metastases to the brain revealed markedly lower intracranial activity than extracranial activity (4).

Targeted therapy and immunotherapy combined with radiotherapy

No data from randomized trials are yet available concerning the optimal sequence and combination of local radiotherapy with targeted therapy or ICI for NSCLC.

Retrospective studies on patients with an activating EGFR mutation, with study sizes ranging from 176 to 351 patients, have shown better survival with a third-generation TKI such as erlotinib (5), gefinitib (6), or osimertinib (7) and early radiosurgery than with sequential therapy in which radiosurgery is only performed when the tumor progresses (table 2).

Table 2. Stereotactic ratiotherapy combined with targeted therapy or immunotherapy for brain metastases of NSCLC.

| Reference | Study type | Study population | Treatment | Toxicity | Intracranial response | Median overall survival |

| Magnuson 2017 (5) | retrospective | n = 351 | – RC followed by EGFR-TKI – WBRT followed by EGFR-TKI – EGFR-TKI followed by RS or WBRT in case of intracranial progression |

not reported | freedom from intracranial progression (median): RS 23 m (HR: 0.73; 95% CI: [0.52; 1.02]), WBRT 24 m (HR: 0.92 [0.66; 1.29]), EGFR-TKI: 17 m |

RS: 46 m (HR: 0.39 [0.26; 0.58]),WBRT: 30 m (HR 0.70 [50%; 98%]), EGFR-TKI: 25 m |

| Miyawaki 2019 (6) | retrospective | n = 176 | – initial EGFR-TKI – initial local therapy |

not reported | freedom from intracranial progression (median): 12 m versus 22 m (HR: 0.54 [0.36; 0.79]) |

23 m versus 28 m (HR: 0.75 [0.52; 1.07]), subgroup with 1–4 BM: 23 m versus 35 m (HR: 0.57 [0.34; 0.91]) |

| Lee 2019 (7) | retrospective | n = 198 | – initial WBRT – initial RS – delayed RT in case of intracranial progression – no intracranial RT |

not reported | freedom from intracranial progression (median): initial WBRT or RS: delayed RT or no RT: 11.7 m (p < 0.001) |

initial WBRT: 18.5 m, initial RS: 55.7 m, delayed RT in case of intracranial progression: 21.1 m, no intracranial RT: 18.2 m (p = 0.008) |

BM, brain metastasis (-es); EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; HR, hazard ratio; m, months; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer;

RS, radiosurgery; RT, radiotherapy; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; WBRT, whole-brain radiation therapy; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval

A meta-analysis of the retrospective studies carried out to date supports the hypothesis of improved overall survival after early combined therapy. The survival advantage was greater in patients with symptomatic brain metastases than in patients with asymptomatic ones (8).

Sparse data are available on the optimal sequence of treatment for NSCLC patients with ALK translocations. The retrospective data to date indicate that combined therapy is advantageous (9).

For most NSCLC patients without any activating driver mutation, immunotherapy alone or in combination with chemotherapy is the standard drug treatment. Many retrospective studies and two meta-analyses (10, 11) with data mainly from patients with NSCLC and melanoma indicate that the combination of immunotherapy and early radiosurgery prolongs overall survival (OS at 12 months, for combined versus non-combined treatment: 64.6% and 51.6%, p <0.001 [11]).

Breast cancer

Systemic treatment alone (table 1)

The treatment options for brain metastases of breast cancer depend on the molecular subtype (12). For triple-negative breast cancer, no data are available on systemic treatment alone after brain metastases arise. Nor are there any prospective data on systemic treatment alone for patients with luminal breast cancer; nonetheless, in this situation, retrospective analyses imply that continuous endocrine therapy may be clinically advantageous for overall survival even after brain metastases arise (13).

The largest number of prospective trials of systemic treatment alone for brain metastases have been carried out on patients with HER2-positive breast cancer (table 1). These patients have the best prognosis with respect to overall survival after brain metastases are diagnosed (12). The combination of lapatinib, a HER2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor, with capecitabine, a chemotherapeutic drug, for the treatment of multiple oligo- or asymptomatic brain metastases has been shown to prolong the time to progression by eight months (14). In a randomized follow-up trial, tucatinib (another tyrosine kinase inhibitor) combined with trastuzumab + capecitabine was compared with trastuzumab + capecitabine alone. In the tucatinib arm, progression-free survival was 9.9 months, compared to 4.2 months in the control group (15).

The efficacy of T-DM1, a trastuzumab-chemotherapy conjugate, has been shown in small case series (16). Trastuzumab-deruxtecan, another trastuzumab-chemotherapy conjugate, has also been found in initial studies to have a comparably high intracranial efficacy. It is now being studied in a trial specifically concerned with brain metastases (17).

Targeted therapy and immunotherapy combined with radiotherapy

Regarding combined radiotherapy and systemic treatment for brain metastases of breast cancer, there have been retrospective studies of lapatinib and radiosurgery, and of lapatinib and WBRT (table 3). A meta-analysis on this subject included six studies up to the year 2020 with a total of 843 HER2-positive patients (442 HER2-amplified, 399 luminal B disease) (18). 279 patients were treated with lapatinib in addition to trastuzumab, with or without chemoradiotherapy, while 610 received trastuzumab-based treatment or chemotherapy alone. In all studies, RS was mainly given as local therapy, with or without WBRT (404 patients). Although WBRT was only used in three studies, it was the most common main form of treatment in terms of the number of patients treated (484 patients). All of the included studies were retrospective (19– 24). The combination of trastuzumab and lapatinib yielded a survival advantage compared to either agent alone (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.55; 95% confidence interval: [0.32; 0.92]). RS combined with lapatinib achieved better local tumor control than RS alone (HR: 0.47 [0.33; 0.66]).

Table 3. Stereotactic radiotherapy combined with targeted therapy or immunotherapy for the treatment of brain metastases of breast cancer.

| Reference | Study type | Study population | Treatment | Toxicity | Intracranial response | Median overall survival |

| Bartsch 2012 (31) |

retrospective | n = 80 | RT (WBRT/RS) + trastuzumab +/− lapatinib |

not reported | not reported | RT + trastuzumab: 13 m RT + trastuzumab + lapatinib: not reachet at 24 m FU, (HR: 0.279; 95% CI: [0.1; 0.76]) |

| Yap 2012 (20) |

retrospective | n = 280 | RT (WBRT/RS) +/− trastuzumab +/− lapatinib |

not reported | not reported | RT + trastuzumab + lapatinib: 25.9 m, RT + lapatinib: 21.4 m, RT + trastuzumab: 10.5 m RT without sys. treatment: 5.7 m |

| Yomo 2013 (21) |

retrospective | n = 40 | RT (RS) +/− lapatinib |

not reported | local 1-year tumor control: RS – lapatinib: 69% RS + lapatinib: 86% (p < 0.001) |

RS – lapatinib: 15 m RS + lapatinib: 19.5 m (p = 0.530) |

| Miller 2017 (22) |

retrospective | n = 233 | RT (WBRT/RS) +/− HER2 new +/− lapatinib |

incidence of radio- necrosis at‧ 12 m: RT: 6.3%, RT + lapatinib: 1.3% (p = 0,001) |

incidence of local recurrence at 12 m: RT: 15.1% RT+ lapatinib: 5.7% (p < 0.001) |

RT: 15.4 m RT + lapatinib: 21.1 m (p = 0.03) |

| Kim 2019 (23) |

retrospective | n = 84 | RT (RS) +/− lapatinib |

incidence of radio- necrosis at 12 m: RT – lapatinib: 3.5%, RT + lapatinib: 1.0% (p = 0.27) |

PD local RT − lapatinib: 43%, RT + lapatinib: 25% p = 0121 PD at 12 m: RT – lapatinib: 49%, RT + lapatinib: 48% (p = 0.91) |

RT – lapatinib: 2.,1 m, RT + lapatinib: 40.4 m (p = 0.155) |

| Parsai 2019 (24) |

retrospective | n = 126 | RT (RS) +/− lapatinib |

incidence of radio- necrosis at 12 m: RT: 6.3%, RT + lapatinib: 1.3% (p < 0.01) |

incidence of local recurrence at 12 m: RT: 15.1%, RT + lapatinib: 5.7% (p < 0.01) | RT: 19.5 m, RT + lapatinib: 27.3 m (p = 0.03) |

| Kotecha 2019 (32) |

retrospective | n = 150 | RT (RS) +/− ICI |

not reported | intracranial response rate:immediate ICI: 71% non-immediate ICI: 53% (p < 0.008) | 30 m |

FU, follow-up; HR, hazard ratio; Her2, human epidermal growth receptor 2; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; m, months; PD, progressive disease;

RS, radiosurgery; RT, radiotherapy; WBRT, whole-brain radiation therapy; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval

In a retrospective comparison, Kim et al. showed statistically significant improvement of intracranial tumor control with lapatinib and concomitant radiotherapy: in 57% of cases, there was a complete response of metastases that were given combined treatment, compared to 38% of metastases that were not. There was no significant increase in the objective response rate per patient (complete remission plus partial remission, 75% vs. 57%) (23). The cumulative 12-month incidence of a distant intracranial recurrence after RS and lapatinib was 48% (95% confidence interval: [28%; 68%]), compared to 49% [40%; 58%] after RS alone. The incidence of radionecrosis was not significantly higher after combination therapy than after RS alone.

Miller et al. reported better distant tumor control after combination therapy than after radiotherapy alone: the 12-month incidence of distant metastases was 9.2% vs. 18.3% (22). Radionecrosis was more common after radiotherapy alone: 1.3% vs. 6.3%. Prospective, randomized trials are now in progress to evaluate modern systemic therapies combined with radiation therapy for brain metastases of breast cancer: pembrolizumab and RS (NCT03449238), atezolizumab and RS for triple-negative breast cancer patients with brain metastases (NCT03483012).

Malignant melanoma

Systemic treatment alone

In patients with newly diagnosed metastatic melanoma and asymptomatic brain metastases, the combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab has been shown to yield similar intra- and extracranial response rates. A complete intracranial remission was seen in 26% of patients. After one year, 59.5% of patients were free of intracranial progression, and 70.4% were free of extracranial progression (25). In asymptomatic patients (of whom there were 18), the efficacy of the combination was markedly lower, with an intracranial response rate of only 16.6% (26). Similarly, prospective trials of combined BRAF and MEK inhibitors have shown comparable extra- and intracranial activity in asymptomatic patients with newly diagnosed brain metastases. Patients with symptomatic and previously locally treated, but currently progressive brain metastases were included as well and displayed an intracranial response rate of 44% (27).

Prospective trials of systemic treatment alone for malignant melanoma have shown a very good response compared to combined approaches with focal radiotherapy, but patient selection must be considered in the evaluation of these data. The best response rate was seen in asymptomatic patients who did not need cortisone. The size of the brain metastases was restricted as well. At present, trials such as the ABC-X trial (NCT03340129) are in progress that will meet the need for an adequate assessment of the optimal combination and sequence of systemic treatment and local radiotherapy. The results are expected to be published over the next few years.

Targeted therapy and immunotherapy combined with radiotherapy

to date, there have only been retrospective studies on combinations of radiosurgery and immunotherapy or targeted therapy for brain metastases of melanoma. Prospective trials are now being carried out in numerous centers.

Multiple studies have provided evidence for the superiority of RS combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) or targeted therapy, compared to monotherapy with systemic treatment alone or with RS (table 4):

Table 4. Stereotactic radiotherapy combined with targeted therapy or immunotherapy for the treatment of brain metastases of malignant melanoma.

| Reference | Study type | Study population | Treatment | Toxicity | Intracranial response | Median overall survival |

| Tétu 2019 (28) |

retrospective | n = 262 | anti-PD1, anti- CTLA4, BRAFi, BRAFi + MEKi +/− RT* |

no increased neurotoxicity in the RT group |

not reported | median OS: combined RT: 16.8 m, non combined: 6.9 m (HR: 0.6; 95% CI [0.4; 0.8] after propensity score matching) |

| Mathew 2013 (33) |

retrospective | n = 58 | RS +/− ipilimumab | no increased bleeding rate with the addition of ipilimumab |

LC at 6 months: RS: 65% RS + ipilimumab: 63% (NS) |

6-month OS RS: 45% RS + ipilimumab: 56% (NS) |

| Kiess 2016 (34) |

retrospective | n = 46 | RS + ipilimumab | grade III/IV toxicity = 20% (pruritus, hepatitis, CNS hemorrhage, seizures) |

not reported | median OS: 12.4 months |

| Diao 2018 (35) |

retrospective | n = 91 | RS +/− ipilimumab | radionecrosis = 5% | 1 year without local recurrence: RS: 45% RS + conc. ipilimumab: 58% RS + non-conc. ipilimumab: 70% (NS) |

median OS: RS: 7.8 m RS + ipilimumab: 15.1 m (p = 0.02) |

| Ahmed 2016 (36) |

retrospective | n = 26 | SRT/RS + nivolumab | no grade III/IV toxicity | LC at 12 months: 85% | median OS: 11.8 m |

| Ahmed 2015 (37) |

retrospective | n = 24 | RS + vemurafenib | 1 case of early recurrence with hemorrhage and necrotic components |

LC at 12 months: 75% | median OS: 11.9 m |

* Radiotherapy was considered “combined” when it was given within the period from 30 days before to 30 days after the first dose of systemic treatment.

BRAFi, BRAF inhibitor; CNS, central nervous system; conc., concomitant; CTLA4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4; HR, hazard ratio; LC, local control; m, months; MEKi, MEK inhibitor; NS, not significant; OS, overall survival; PD1, programmed cell death protein 1; RS, radiosurgery; RT, radiotherapy; SRT, stereotactic radiotherapy; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval

A retrospective analysis of a prospectively acquired registry of 262 patients treated either with ICI or with targeted therapy revealed, after propensity score matching, that patients who received combined radiotherapy (ICI + RS or WBRT) had a significant survival advantage compared to those who did not (28).

In a systematic review of 95 studies on patients with brain metastases of melanoma, tumor control was found to be the best, and survival the longest, after radiotherapy combined with immunotherapy or targeted therapy. As for treatment timing, the best outcome was achieved when radiotherapy was performed before or during systemic treatment (29).

In a meta-analysis, Lehrer et al. studied the combination of RS and ICI for brain metastases on the basis of individual data from 534 patients, most of whom suffered from melanoma. One-year overall survival was better, to a statistically significant extent, after simultaneous therapy, compared to non-simultaneous therapy (64.6% vs. 51.6%). Likewise, with respect to the regional control of brain metastases after one year, the simultaneous administration of ICI and RS was superior to their sequential administration (ICI and then RS; 38.1% vs. 12.3%) (11).

Conclusion

The prognosis of patients with brain metastases with respect to survival has markedly improved in recent years, and thus the quality of life and the avoidance of neurocognitive sequelae of uncontrolled brain metastases, and of the treatment itself, have become important issues. The findings of prospective, randomized trials concerning the optimal combination and temporal sequence of modern radiotherapy and systemic therapies are expected within the next few years.

Aside from potentially indicated neurosurgical intervention, multimodal combined treatment based on the current scientific evidence, consisting of initial local radiotherapy followed by targeted therapy or immunotherapy, is a safe therapeutic strategy that enables the best possible control of brain metastases. Radiosurgery has now replaced whole-brain radiation therapy in many situations, even when multiple metastases are present.

Questions on the article in issue 45/2021:

Focal Radiotherapy of Brain Metastases in Combination With Immunotherapy and Targeted Drug Therapy

The submission deadline is 11 November 2022.

Only one answer is possible per question. Please select the answer that is most appropriate.

Question 1

What is the approximate survival time of patients with brain metastases if they undergo no treatment?

one week

one month

three months

six months

one year

Question 2

What three types of cancer most commonly give rise to brain metastases?

lung cancer, breast cancer, malignant melanoma

breast cancer, basal-cell carcinoma, lung cancer

lung cancer, bladder cancer, basal-cell carcinoma

testicular cancer, lung cancer, uterine cancer

non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, lung cancer, bladder cancer

Question 3

For what type of metastatic disease is radiosurgery the radiotherapeutic method of choice?

≤ 2 brain metastases, diameter > 4 cm, markedly symptomatic

≥ 10 brain metastases, diameter > 5 cm, markedly symptomatic

≤ 4 brain metastases, diameter > 5 cm, oligo- or asymptomatic

≤ 4 brain metastases, diameter ≤ 4 cm, oligo- or asymptomatic

≤ 3 brain metastases, diameter > 8 cm, markedly symptomatic

Question 4

What is the advantage of radiosurgery compared to whole-brain radiation therapy?

rarer appearance of new brain metastases

better preservation of neurocognitive function

more effective, because delivered in multiple fractions

lower equivalent dose

no need for stereotactic fixation of the head

Question 5

What type of follow-up is recommended after the radiosurgical treatment of brain metastases?

cranial computerized tomography (cCT) every 1–2 months

cranial magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) every 2–3 weeks

cranial magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) every 2–3 months

cranial computerized tomography (cCT) every 1–2 weeks

cranial magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) every 6 months

Question 6

Brain metastases of what kind of primary tumor can be treated with osimertinib?

breast cancer with a mutation in the HER2 gene (HER2-positive)

non-small-cell lung cancer with a mutation in the gene for the programmed cell death ligand protein (PD-L1-pos)

malignant melanoma with a mutation in the BRAF gene

non-small-cell lung cancer with a mutation in the EGF receptor gene (EGFR-mut)

colon cancer with a mutation in the BRAF gene

Question 7

In a meta-analysis by Lehrer et al. with data from patients mainly suffering from malignant melanoma as their primary tumor, simultaneous (combined) treatment with focal radiotherapy and checkpoint inhibitors was compared with non-simultaneous (sequential) treatment. What were the 12-month survival figures for patients receiving these two forms of treatment?

45.1% (combined) versus 62.4% (sequential)

96.2% (combined) versus 49.5% (sequential)

30.8% (combined) versus 58.5% (sequential)

15.3% (combined) versus 30.7% (sequential)

64.6% (combined) versus 51.6% (sequential)

Question 8

Which of the following agents is mainly used to treat breast cancer?

ipilimumab

vemurafenib

lapatinib

nivolumab

pembrolizumab

Question 9

In what percentage of brain metastases treated with radiosurgery does radionecrosis occur later?

up to 0.5%

up to 2%

up to 5%

up to 10%

up to 25%

Question 10

What method of radiotherapy does the abbreviation SRT stand for?

selective radiotherapy

sequential radiotherapy

superficial radiotherapy

stereotactic radiotherapy

sparing radiotherapy

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

PD Dr. Kaul has received reimbursement of travel expenses from Accuray.

Prof. Berghoff has been a paid consultant for Roche and Daiichi and has received reimbursement of meeting participation fees and of travel and accommodation expenses from Roche, Amgen, Daiichi, and Abbvie, as well as lecture honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb. She has received financial support from Daiichi for a research project that she initiated.

The remaining authors state that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Reungwetwattana T, Nakagawa K, Cho BC, et al. CNS response to osimertinib versus standard epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with untreated EGFR-mutated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:3290–3297. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.3118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gadgeel S, Peters S, Mok T, et al. Alectinib versus crizotinib in treatment-naive anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive (ALK+) non-small-cell lung cancer: CNS efficacy results from the ALEX study. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:2214–2222. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Besse B, Le Moulec S, Mazieres J, et al. Bevacizumab in patients with nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer and asymptomatic, untreated brain metastases (BRAIN): a nonrandomized, phase II study. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:1896–1903. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldberg SB, Gettinger SN, Mahajan A, et al. Pembrolizumab for patients with melanoma or non-small-cell lung cancer and untreated brain metastases: early analysis of a non-randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:976–983. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30053-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magnuson WJ, Lester-Coll NH, Wu AJ, et al. Management of brain metastases in tyrosine kinase inhibitor-naive epidermal growth factor receptor-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer: a retrospective multi-institutional analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:1070–1077. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.7144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyawaki E, Kenmotsu H, Mori K, et al. Optimal sequence of local and EGFR-TKI therapy for EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer with brain metastases stratified by number of brain metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;104:604–613. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee JH, Chen HY, Hsu FM, et al. Cranial irradiation for patients with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutant lung cancer who have brain metastases in the era of a new generation of EGFR inhibitors. Oncologist. 2019;24:e1417–e1425. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong K, Liang W, Zhao S, et al. EGFR-TKI plus brain radiotherapy versus EGFR-TKI alone in the management of EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients with brain metastases. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2019;8:268–279. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2019.06.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ni J, Li G, Yang X, et al. Optimal timing and clinical value of radiotherapy in advanced ALK-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer with or without baseline brain metastases: implications from pattern of failure analyses. Radiat Oncol. 2019;14 doi: 10.1186/s13014-019-1240-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu VM, Goyal A, Rovin RA, Lee A, McDonald KL. Concurrent versus non-concurrent immune checkpoint inhibition with stereotactic radiosurgery for metastatic brain disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurooncol. 2019;141:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11060-018-03020-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehrer EJ, Peterson J, Brown PD, et al. Treatment of brain metastases with stereotactic radiosurgery and immune checkpoint inhibitors: An international meta-analysis of individual patient data. Radiother Oncol. 2019;130:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2018.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sperduto PW, Mesko S, Li J, et al. Beyond an updated graded prognostic assessment (Breast GPA): a prognostic index and trends in treatment and survival in breast cancer brain metastases from 1985 to today. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;107:334–343. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.01.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergen ES, Berghoff AS, Medjedovic M, et al. Continued endocrine therapy is associated with improved survival in patients with breast cancer brain metastases. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:2737–2744. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bachelot T, Romieu G, Campone M, et al. Lapatinib plus capecitabine in patients with previously untreated brain metastases from HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (LANDSCAPE): a single-group phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:64–71. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70432-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin NU, Borges V, Anders C, et al. Intracranial efficacy and survival with tucatinib plus trastuzumab and capecitabine for previously treated HER2-positive breast cancer with brain metastases in the HER2CLIMB trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:2610–2619. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.00775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartsch R, Berghoff AS, Vogl U, et al. Activity of T-DM1 in Her2-positive breast cancer brain metastases. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2015;32:729–737. doi: 10.1007/s10585-015-9740-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Modi S, Saura C, Yamashita T, et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:610–621. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1914510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan M, Zhao Z, Arooj S, Zheng T, Liao G. Lapatinib plus local radiation therapy for brain metastases from HER-2 positive breast cancer patients and role of trastuzumab: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 2020;10 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.576926. 576926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartsch R, Bago-Horvath Z, Berghoff A, et al. Ovarian function suppression and fulvestrant as endocrine therapy in premenopausal women with metastatic breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:1932–1938. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yap YS, Cornelio GH, Devi BC, et al. Brain metastases in Asian HER2-positive breast cancer patients: anti-HER2 treatments and their impact on survival. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:1075–1082. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yomo S, Hayashi M, Cho N. Impacts of HER2-overexpression and molecular targeting therapy on the efficacy of stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases from breast cancer. J Neurooncol. 2013;112:199–207. doi: 10.1007/s11060-013-1046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller JA, Kotecha R, Ahluwalia MS, et al. Overall survival and the response to radiotherapy among molecular subtypes of breast cancer brain metastases treated with targeted therapies. Cancer. 2017;123:2283–2293. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim JM, Miller JA, Kotecha R, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery with concurrent HER2-directed therapy is associated with improved objective response for breast cancer brain metastasis. Neuro Oncol. 2019;21:659–668. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noz006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parsai S, Miller JA, Juloori A, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery with concurrent lapatinib is associated with improved local control for HER2-positive breast cancer brain metastases. J Neurosurg. 2019;132:503–511. doi: 10.3171/2018.10.JNS182340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tawbi HAH, Forsyth PA, Algazi A, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in melanoma metastatic to the brain. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:722–730. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tawbi HAH, Forsyth PAJ, Hodi FS, et al. Efficacy and safety of the combination of nivolumab (NIVO) plus ipilimumab (IPI) in patients with symptomatic melanoma brain metastases (CheckMate 204) Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2019;37 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davies MA, Saiag P, Robert C, et al. Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with BRAFV600-mutant melanoma brain metastases (COMBI-MB): a multicentre, multicohort, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:863–873. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30429-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tétu P, Allayous C, Oriano B, et al. Impact of radiotherapy administered simultaneously with systemic treatment in patients with melanoma brain metastases within MelBase, a French multicentric prospective cohort. Eur J Cancer. 2019;112:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Opijnen MP, Dirven L, Coremans IEM, Taphoorn MJB, Kapiteijn EHW. The impact of current treatment modalities on the outcomes of patients with melanoma brain metastases: a systematic review. Int J Cancer. 2020;146:1479–1489. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schuler M, Wu YL, Hirsh V, et al. First-line afatinib versus chemotherapy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer and common epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations and brain metastases. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:380–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2015.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bartsch R, Berghoff A, Pluschnig U, et al. Impact of anti-HER2 therapy on overall survival in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer patients with brain metastases. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:25–31. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kotecha R, Kim JM, Miller JA, et al. The impact of sequencing PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors and stereotactic radiosurgery for patients with brain metastasis. Neuro Oncol. 2019;21:1060–1068. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noz046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mathew M, Tam M, Ott PA, et al. Ipilimumab in melanoma with limited brain metastases treated with stereotactic radiosurgery. Melanoma Res. 2013;23:191–195. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e32835f3d90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kiess AP, Wolchok JD, Barker CA, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for melanoma brain metastases in patients receiving ipilimumab: safety profile and efficacy of combined treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;92:368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diao K, Bian SX, Routman DM, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery and ipilimumab for patients with melanoma brain metastases: clinical outcomes and toxicity. J Neurooncol. 2018;139:421–429. doi: 10.1007/s11060-018-2880-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahmed KA, Stallworth DG, Kim Y, et al. Clinical outcomes of melanoma brain metastases treated with stereotactic radiation and anti-PD-1 therapy. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:434–441. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahmed KA, Freilich JM, Sloot S, et al. LINAC-based stereotactic radiosurgery to the brain with concurrent vemurafenib for melanoma metastases. J Neurooncol. 2015;122:121–126. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1685-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Lang EF, Slater J. Metastatic brain tumors. Results of surgical and nonsurgical treatment. Surg Clin North Am. 1964;44:865–872. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)37308-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Nayak L, Lee EQ, Wen PY. Epidemiology of brain metastases. Curr Oncol Rep. 2012;14:48–54. doi: 10.1007/s11912-011-0203-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Schellinger PD, Meinck HM, Thron A. Diagnostic accuracy of MRI compared to CCT in patients with brain metastases. J Neurooncol. 1999;44:275–281. doi: 10.1023/a:1006308808769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Steindl A, Kreminger J, Moor E, et al. Clinical characterization of a real-life cohort of 6001 patients with brain metastases from solid cancers treated between 1986-2020. Profferred Paper, ESMO Virtual Congress 2020. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(suppl. 4):S397–S408. [Google Scholar]

- E5.DGN - Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie. Leitlinie Hirnmetastasen und Meningeosis neoplastica. www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/030-060l_S2k_Hirnmetastasen_Meningeosis_neoplastica_ 2015-06-abgelaufen.pdf (last accessed on 11 July 2021) [Google Scholar]

- E6.Suh JH, Kotecha R, Chao ST, Ahluwalia MS, Sahgal A, Chang EL. Current approaches to the management of brain metastases. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17:279–299. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0320-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Berghoff AS, Bartsch R, Wohrer A, et al. Predictive molecular markers in metastases to the central nervous system: recent advances and future avenues. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;128:879–891. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1350-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Andrews DW, Scott CB, Sperduto PW, et al. Whole brain radiation therapy with or without stereotactic radiosurgery boost for patients with one to three brain metastases: phase III results of the RTOG 9508 randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;363:1665–1672. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Kocher M, Soffietti R, Abacioglu U, et al. Adjuvant whole-brain radiotherapy versus observation after radiosurgery or surgical resection of one to three cerebral metastases: results of the EORTC 22952-26001 study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:134–141. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Arvanitis CD, Ferraro GB, Jain RK. The blood-brain barrier and blood-tumour barrier in brain tumours and metastases. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20:26–41. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0205-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E11.Mori Y, Kondziolka D, Flickinger JC, Kirkwood JM, Agarwala S, Lunsford LD. Stereotactic radiosurgery for cerebral metastatic melanoma: factors affecting local disease control and survival. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;42:581–589. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00272-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Mori Y, Kondziolka D, Flickinger JC, Logan T, Lunsford LD. Stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastasis from renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 1998;83:344–353. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980715)83:2<344::aid-cncr19>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Lesueur P, Lequesne J, Barraux V, et al. Radiosurgery or hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for brain metastases from radioresistant primaries (melanoma and renal cancer) Radiat Oncol. 2018;13 1 doi: 10.1186/s13014-018-1083-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.Kohutek ZA, Yamada Y, Chan TA, et al. Long-term risk of radionecrosis and imaging changes after stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases. J Neurooncol. 2015;125:149–156. doi: 10.1007/s11060-015-1881-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E15.Aoyama H, Shirato H, Tago M, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery plus whole-brain radiation therapy vs stereotactic radiosurgery alone for treatment of brain metastases: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2483–2491. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.Li J, Ludmir EB, Wang Y, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery versus whole-brain radiation therapy for patients with 4-15 brain metastases: a phase III randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics. 2020;108:S21–S22. [Google Scholar]

- E17.Yamamoto M, Serizawa T, Shuto T, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for patients with multiple brain metastases (JLGK0901): a multi-institutional prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:387–395. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E18.Proescholdt MA, Schodel P, Doenitz C, et al. The management of brain metastases-systematic review of neurosurgical aspects. Cancers (Basel) 2021 doi: 10.3390/cancers13071616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E19.Chang EL, Wefel JS, Hess KR, et al. Neurocognition in patients with brain metastases treated with radiosurgery or radiosurgery plus whole-brain irradiation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1037–1044. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70263-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E20.Li J, Bentzen SM, Li J, Renschler M, Mehta MP. Relationship between neurocognitive function and quality of life after whole-brain radiotherapy in patients with brain metastasis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E21.Pinkham MB, Sanghera P, Wall GK, Dawson BD, Whitfield GA. Neurocognitive effects following cranial irradiation for brain metastases. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2015;27:630–639. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E22.Tsao MN, Xu W, Wong RK, et al. Whole brain radiotherapy for the treatment of newly diagnosed multiple brain metastases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;1 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003869.pub4. CD003869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E23.Brown PD, Gondi V, Pugh S, et al. Hippocampal avoidance during whole-brain radiotherapy plus memantine for patients with brain metastases: phase III trial NRG oncology CC001. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:1019–1029. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E24.Grosu AL, Frings L, Bentsalo I, et al. Whole-brain irradiation with hippocampal sparing and dose escalation on metastases: neurocognitive testing and biological imaging (HIPPORAD)—a phase II prospective randomized multicenter trial (NOA-14, ARO 2015-3, DKTK-ROG) BMC Cancer. 2020;20 doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07011-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E25.Lange M, Joly F, Vardy J, et al. Cancer-related cognitive impairment: an update on state of the art, detection, and management strategies in cancer survivors. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:1925–1940. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E26.Joly F, Castel H, Tron L, Lange M, Vardy J. Potential effect of immunotherapy agents on cognitive function in cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020;112:123–127. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]