Abstract

Background:

Tapering and discontinuing antidepressants are important aspects of the management of patients with depression and should therefore be considered in clinical practice guidelines.

Objectives:

We aimed to assess the extent and content, and appraise the quality, of guidance on tapering and discontinuing antidepressants in major clinical practice guidelines on depression.

Methods:

Systematic review of clinical practice guidelines on depression issued by national health authorities and major national or international professional organisations in the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, Singapore, Ireland and New Zealand (PROSPERO CRD42020220682). We searched PubMed, 14 guideline registries and the websites of relevant organisations (last search 25 May 2021). The clinical practice guidelines were assessed for recommendations and information relevant to tapering and discontinuing antidepressants. The quality of the clinical practice guidelines as they pertained to tapering and discontinuation was assessed using the AGREE II tool.

Results:

Of the 21 included clinical practice guidelines, 15 (71%) recommended that antidepressants are tapered gradually or slowly, but none provided guidance on dose reductions, how to distinguish withdrawal symptoms from relapse or how to manage withdrawal symptoms. Psychological challenges were not addressed in any clinical practice guideline, and the treatment algorithms and flow charts did not include discontinuation. The quality of the clinical practice guidelines was overall low.

Conclusion:

Current major clinical practice guidelines provide little support for clinicians wishing to help patients discontinue or taper antidepressants in terms of mitigating and managing withdrawal symptoms. Patients who have deteriorated upon following current guidance on tapering and discontinuing antidepressants thus cannot be concluded to have experienced a relapse. Better guidance requires better randomised trials investigating interventions for discontinuing or tapering antidepressants.

Keywords: antidepressant tapering, clinical practice guidelines, depression, withdrawal symptoms

Introduction

Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) on depression generally recommend treatment with an antidepressant for moderate to severe episodes of depression as one treatment option and, given the clinical situation, the treatment is recommended to stop after a certain period.1–3 About half of the patients on antidepressants who try to discontinue or reduce the dose experience withdrawal symptoms,4,5 including flu-like symptoms, anxiety, emotional lability, lowering of mood, irritability, bouts of crying, dizziness, shaking, fatigue and electric shock sensations.6,7 The symptoms usually persist for weeks but can last months or even years, 4 and half of the patients who experience them rate the symptoms as severe. 4 Beyond the physiological effects related to drug withdrawal, discontinuing antidepressants can be difficult for psychological reasons. These include worry of relapse, a perceived biochemical cause of depression, insufficient emotion regulation skills and coping strategies, need for social support, psychological dependence, and experience of previous unsuccessful discontinuation attempts.8–11

The incidence and severity of withdrawal symptoms may depend on how the antidepressant is tapered,12–16 suggesting that the dose-reduction regimen is an important factor to successful discontinuation of antidepressants. Studies thus indicate that short-term tapering regimens result in a lower proportion of patients succeeding in discontinuing antidepressants compared with a longer tapering period.13–15 Furthermore, preliminary data from non-randomised trials suggest that hyperbolic tapering through tapering strips may reduce the incidence of withdrawal symptoms.17,18 Some CPGs, however, recommend short periods of tapering or even no tapering at all, depending on the specific antidepressant,1,2 but the evidence base for such recommendations is unclear.19,20

Tapering and discontinuing antidepressants are important aspects of the management of patients with depression, and relevant guidance should be considered an integral part of treatment guidelines for depression. The extent and characteristics of such guidance in current CPGs, however, is unclear.

We thus aimed to, for the first time, systematically review the guidance on tapering and discontinuing antidepressants in CPGs for depression issued by those national health authorities or major national or international professional organisations and societies that are likely to have the most impact on clinical practice. Our primary objective was to assess the extent and content of the guidance on tapering and discontinuing of antidepressants. As a secondary objective, we wished to appraise the quality of these guidelines as they pertained to discontinuation and tapering of antidepressants.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of CPGs on depression and appraised their quality using the AGREE II instrument. 21

Our protocol was developed according to the PRISMA-P guideline 22 and was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) on 16 November 2020 (registration ID CRD42020220682). We reported the review according to the PRISMA guideline. 23

Eligibility criteria

We defined the inclusion and exclusion criteria according to the PICAR framework for systematic reviews of CPGs (Table 1). 24

Table 1.

PICAR inclusion criteria.

| Population & clinical indication | Patients with depression Any age Any symptom severity |

| Interventions | Antidepressant treatment |

| Comparators, comparisons and content |

Comparators: Any, including none Key content: Guidance on stopping or reducing treatment |

| Attributes of eligible CPGs |

Language: Available in English Year of publication: Most recent from each organisation Publishing region: English-speaking, high-income countries Version: Latest version only System of rating evidence: Any Scope: Must have primary focus on treatment of depression Recommendations: No restrictions; CPGs will be included regardless of whether they contain guidance on tapering/discontinuation treatment or not |

| Recommendation characteristics |

Duration of treatment: No restrictions Levels of confidence: No restrictions Interventions: No restrictions Comparators: No restrictions; recommendations are not required to compare an intervention of interest with another intervention Locating recommendations: Within CPG text, tables, algorithms or decision paths |

CPG, clinical practice guideline.

To ensure clinical relevance, eligibility was restricted to CPGs issued by national health authorities and major national or international professional organisations or societies in English-speaking high-income countries (the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, Singapore, Ireland and New Zealand). Thus, we prioritised guidelines with the likely highest impact on clinical practice internationally over the inclusion of all existing treatment guidelines on depression. There were no restrictions on publication year. For each guideline, if several iterations were available, we included the latest version.

We included CPGs for the treatment of depression that recommended antidepressants. CPGs on non-pharmacological treatment only and CPGs that focused on the treatment of conditions other than depression were excluded. We applied no restrictions on symptom severity, treatment duration, comorbidity, other treatments, age, sex, ethnicity or hospitalisation status.

Data sources and searches

We first manually searched the websites of the governmental organisations, national health authorities, national psychiatric societies, and national psychological societies of each country and those of major international professional societies.

Next, we searched PubMed and 14 guideline registries [National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Standards and Guidelines Evidence, American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guidelines, National Health and Medical Research Council, New Zealand Guidelines Group, eGuidelines, Guidelines.co.uk, Guidelines International Network Library, Scottish Intercollegate Guidelines Network, the former National Guideline Clearinghouse (now hosted at www.ahrq.gov), Canadian Medical Association Infobase, National Library for Health Guidelines Finder, Best Practice Guidelines, and Magic]. See Supplementary Table 1 for details. Search terms for PubMed were as follows: [Depression(TI) OR ‘Depressive Disorder’(Mesh) OR ‘Depression’(Mesh)] AND [guideline(Publication Type) OR guideline*(TI)].

Finally, we searched Google for additional unique records using broader search terms for ‘depression’ and ‘guideline’, screening the top 100 hits, and scanned the reference lists of all retrieved CPGs.

All sources were last searched on 25 May 2021.

Study selection

Two researchers (A.S. and K.M.) independently screened the titles and abstracts of the identified records for eligibility. Full reports were retrieved for all records that appeared to meet our inclusion criteria or where there was uncertainty and screened for eligibility by two researchers (A.S. and K.M.) independently. Reasons for exclusion were noted. Disagreements were resolved by discussion, potentially involving a third researcher (K.J.J.). For all included CPGs we, additionally, retrieved any associated companion articles (e.g. methodology supplements and background documents) or relevant accompanying online information.

Data extraction

Two researchers (A.S. and K.M.) read the guideline documents and independently extracted the data using a standardised and piloted data extraction form in MS Excel™. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. We extracted the following data: title, year, source, country of origin, authors, funding source, conflicts of interest, when to consider discontinuing antidepressants, duration of maintenance treatment, duration of tapering period, dose-reduction regimen, tapering regimen (e.g. gradual, linear, hyperbolic), actions if withdrawal symptoms emerge, actions if deterioration or relapse occurs, mention of risk of confounding withdrawal symptoms with relapse, benefits and harms associated with tapering and discontinuing antidepressants, mention of any psychological challenges to discontinuing antidepressant treatment and mention of peer-support as a potential supportive measure. Text excerpts pertaining to tapering and discontinuing antidepressants were also extracted.

Quality assessment

Two researchers (A.S. and K.M.) independently assessed the quality of the guidelines containing guidance on tapering or discontinuing antidepressants using the AGREE II tool, 21 covering 23 items in the domains of scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigour of development, clarity of presentation, applicability and editorial independence. Items 9, 11, 12 and 15–21 were assessed specifically in relation to recommendations on tapering and discontinuation, whereas the remaining items were assessed by considering the guideline in total. The quality appraisal was therefore not an appraisal of the guidelines in their totality but specific for issues pertaining to tapering and discontinuing antidepressants. Guidelines not containing guidance on tapering or discontinuing were noted as ‘not covered’, and their quality was not assessed. Each item was scored on a 7-point Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). A final quality score for each domain was reached by summing the scores for each item obtained by the two independent researchers and scaling the total as a percentage of the maximum possible score for each domain (percentage = obtained score – minimum score / maximum possible score – minimum possible score × 100). ‘High quality’ of a CPG was defined according to suggestions in the AGREE II user’s manual as >70% on all domain scores. We then calculated the mean (SD) domain scores of each guideline. Finally, both researchers made an overall assessment for each CPG.

Data synthesis and analysis

We constructed a recommendation matrix with all recommendations pertaining to tapering and discontinuing antidepressants and calculated the proportion of guidelines covering the different types of guidance. We presented the AGREE II scores for individual domains and in total and calculated the mean (SD) of each domain across the included guidelines. Based on individual domain scores, we identified issues that contributed substantially to decreasing the quality of the guidelines.

Results

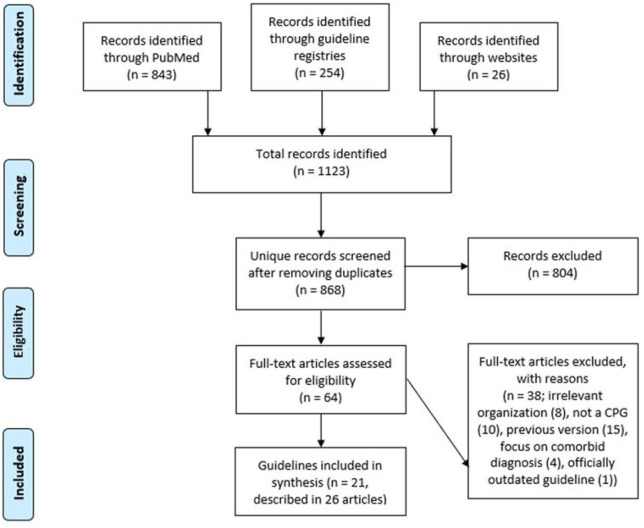

Our literature searches identified a total of 1123 hits (PubMed n = 843, guideline registries n = 254, manual website search n = 26). After removing duplicates, 868 unique records remained. After reviewing the titles and abstracts, we discarded 804 records. We examined the full text of the remaining 64 records and excluded a total of 38 records because they were either authored by an ineligible organisation (n = 8), not a CPG (n = 10), a later version of the CPG existed (n = 15), the CPG focused on a comorbid diagnosis (n = 4) and because the record pertained to a CPG that was no longer considered guidance for current practice by the organisation responsible for the CPG (n = 1). See Supplementary Table 2 for references to excluded records with reasons. In total, we included 21 unique CPGs (reported in 26 records).1–3,25–47 For one CPG, 31 we manually identified a newer version 48 not identified in any of our searches, which we included instead. The study selection process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study selection process.

Guideline characteristics

Of the 21 CPGs, seven were from the United States,26–30,32,48 five from the United Kingdom,1,2,33,35,36 and one from Canada, 37 New Zealand, 39 Scotland, 40 Singapore, 41 Ireland 42 and Australia/New Zealand, 3 respectively. Three CPGs were issued by international organisations.44,45,47 The CPGs were published between 1998 and 2020 (Table 2). Conflicts of interest for all authors were reported in 9 (43%) of the CPGs,3,28–30,33,35–37,47 and at least one author reported a financial conflict of interest in all the 14 CPGs that reported financial conflicts of interest.2,3,26,28,30,31,33,36,37,43

Table 2.

Characteristics of included guidelines.

| Source | Title | Country | Year | Issuing organisation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Practice Guidelines (AHCPR) | Treating major depression in primary care practice – an update of the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Practice Guidelines 32 | US | 1998 | National health service |

| American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) | Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders 48 | US | 2007 | Professional society |

| American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) | Guidelines for adolescent depression in primary care (GLAD-PC)): Part I. Practice preparation, identification, assessment and initial management + Part II. Treatment and ongoing management 26 | US | 2018 | Patient organisation + commercial company |

| American Psychological Association (APA) | Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of depression across three cohorts 29 | US | 2019 | Professional society |

| American Psychiatric Association (APA) | Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder Third Edition 28 | US | 2010 | Professional society |

| American College of Physicians (ACP) | Nonpharmacologic versus pharmacologic treatment of adult patients with major depressive disorder: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians 30 | US | 2016 | Professional society |

| British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP) | Evidence-based guidelines for treating depressive disorders with antidepressants: A revision of the 2008 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines 2 | UK | 2015 | Professional society |

| National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCCMH) | Depression: The NICE guideline on the treatment and management of depression in adults – updated edition 36 | UK | 2019 | Professional society |

| Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) | Canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: Section 3. Pharmacological Treatments 37 | Ca | 2016 | Professional organisation |

| Department of Veteran Affairs and Department of Defense (VA/DoD) and The Management of Major Depressive Disorder Working Group | VA/DoD Clinical practice guideline for the management of major depressive disorder 27 | US | 2016 | Government |

| Health Service Executive (HSE) and Irish College of General Practitioners (ICGP) | Guidelines for the management of depression and anxiety disorders in primary care 42 | Ir | 2006 | Professional society |

| Ministry of Health Singapore | Depression 41 | Si | 2012 | National health authority |

| National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) | Depression in adults – recognition and management 1 | UK | 2009 | Government |

| New Zealand Guidelines Group (NZGG) and Ministry of Health New Zealand | Identification of common mental disorders and management of depression in primary care 39 | NZ | 2008 | Government |

| National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) | Depression in children and young people – identification and management 33 | UK | 2019 | Government |

| Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) | The 2020 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders 3 | Aus, NZ | 2020 | Professional society |

| Royal College of Psychiatrists (RCPSYCH) and the Faculty of Old Age Psychiatry Working Group | Guideline for the management of late-life depression in primary care 35 | UK | 2003 | Professional society |

| Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) and Healthcare Improvement Scotland (HSE) | Management of perinatal mood disorders 40 | Sc | 2012 | Government |

| World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) | World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for biological treatment of unipolar depressive disorders, Part 1: Update 2013 on the acute and continuation treatment of unipolar depressive disorders + Part 2: Maintenance treatment of major depressive disorder – update 201544 | Int | 2013 + 2015 | Professional organisation |

| World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) | Guidelines for biological treatment of unipolar depressive disorders in primary care 45 | Int | 2007 | Professional society |

| World Health Organization (WHO) | Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) Intervention Guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings (2016) + WHO mhGAP Guideline Update (2015) 47 | Int | 2015 + 2016 | NGO |

Aus, Australia; Ca, Canada; Int, international; Ir, Ireland; mhGAP, Mental Health Gap Action Programme; NGO, non-governmental organisation; NZ, New Zealand; UK, the United Kingdom; US, the United States of America; Sc, Scotland; Si, Singapore.

Guidance on tapering and discontinuation

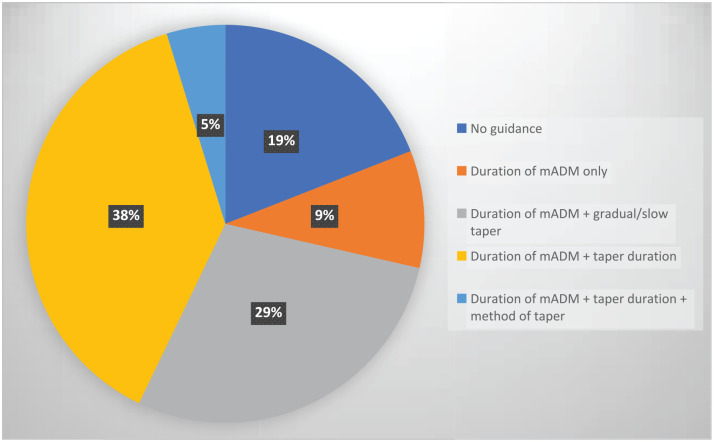

The prevalence of the different types of guidance for tapering and discontinuation is illustrated in Figure 2, summarised in Tables 3 and 4, and described below. The text excerpts pertaining to the guidance are presented in Supplementary Table 3.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of guidance on tapering in clinical practice guidelines on depression.

mADM, maintenance antidepressant medication.

Table 3.

Guidance on tapering and discontinuing antidepressants mentioned in clinical practice guidelines on depression.

| mADM duration | Gradual tapering | Hyperbolic tapering | Duration of taper | Dose-reduction regimen | WS actions | Relapse actions | WS as harm | Relapse as harm | Symptomatic overlap | Benefits mentioned | Psychological barriers | Peer-support | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 17 (81%) | 15 (71%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (43%) | 2 (10%) | 5 (24%) | 4 (19%) | 15 (71%) | 14 (67%) | 4 (19%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| American Psychiatric Association 28 | + | + | – | – | – | + | + | + | + | + | – | – | – |

| BAP 2 | + | + | – | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | – | – | – |

| NCCMH 36 | + | + | – | + | – | + | – | + | + | + | – | – | – |

| NICE 1 | + | + | – | + | – | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | – |

| NZGG 39 | + | + | – | + | – | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | – |

| NICE 33 | + | + | – | + | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – |

| WFSBP 44 | + | + | – | + | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | – | – |

| WFSBP 45 | + | + | – | + | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | – | – |

| WHO 47 | + | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – |

| CANMAT 37 | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – |

| AAP 26 | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | – |

| VA/DoD 27 | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | – |

| AACAP 48 | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | – |

| RANZCP 3 | + | + | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | – |

| MoH (Si) 41 | + | + | – | + | + | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | – |

| HSE 42 | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – |

| SIGN 40 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – |

| RCPSYCH 35 | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| AHCPR 32 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| APA 29 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| ACP 30 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

AACAP, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; AAP, American Academy of Pediatrics; ACP, American College of Physicians; AHCPR, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Practice Guidelines; APA, American Psychological Association; BAP, British Association for Psychopharmacology; CANMAT, Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments; HSE, Health Service Executive; mADM, maintenance antidepressant medication; MoH (Si), Ministry of Health, Singapore; NCCMH, National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NZGG, New Zealand Guidelines Group; RANZCP, Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists; RCPSYCH, Royal College of Psychiatrists; Relapse actions, guidance on actions if relapse or deterioration in general occurs; Relapse as harm, mention of relapse as a possible harm of tapering or discontinuing antidepressants; SIGN, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; Symptomatic overlap, mention of the symptomatic overlap between withdrawal symptoms and relapse; VA/DoD, Department of Veteran Affairs and Department of Defense; WFSBP, World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry; WHO, World Health Organization; WS, withdrawal symptoms; WS actions, guidance on actions if withdrawal symptoms occur; WS as harm, mention of withdrawal symptoms as a possible harm of tapering or discontinuing antidepressants. ‘+’ indicates that the item was mentioned in the guideline. ‘–’ indicates that the item was not mentioned in the guideline.

Table 4.

Summary of recommendations on discontinuation and tapering of antidepressants in clinical practice guidelines on depression.

| Source and year | Duration of mADM | Duration of taper | Actions if discontinuation symptoms emerge | Actions if deterioration/relapse occurs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAP 2 | 6 mo–>2 yr | >4 wks–some months | Explanation and reassurance; resume AD and taper more slowly; switch to fluoxetine and stop | Restart an AD; reestablish previous dose |

| RANZCP 3 | >6 mo | Slowly | – | – |

| HSE + ICGP 42 | >6 mo–12 mo | – | – | – |

| CANMAT 37 | 6 mo–>2 yr | Several weeks | – | – |

| WFSBP 44 | >6 mo–lifetime | >3 mo to 4–6 mo | – | Resume full dose for at least 6 months |

| AAP 26 | 6 mo–1 year | Slow taper | – | |

| SIGN + HIS 40 | – | – | – | – |

| VA/DoD 27 | >6 mo–indefinitely | Slow taper | – | – |

| WHO46,47 | >9–12 mo | >4 wk | – | – |

| American Psychiatric Association 28 | 4 mo–indefinitely | Several weeks–a longer period | Reassurance and a more gradual taper; switch to fluoxetine and stop | Resume AD treatment; monitor symptoms |

| APA 29 | – | – | – | – |

| ACP 30 | – | – | – | – |

| NZGG + MoH (NZ) 39 | >6 mo–>2 yr | 4 wk | Resume AD and taper more slowly | – |

| NICE 33 | >6 mo | 6–12 wk | – | |

| WFSBP 45 | >6 mo–lifetime | >6 wk to 4–6 mo | – | Resume full dose for at least 6 months |

| AACAP 48 | >6 mo–indefinitely | Slowly | – | – |

| NICE 1 | >6 mo–>2 yr | 4 wk–longer | Seek advice from practitioner; monitoring and reassurance; resume AD and taper more gradually; start another AD with longer half-life and taper more gradually | – |

| AHCPR 32 | – | – | – | – |

| RCPSYCH 35 | >1–> 3 yr | – | – | – |

| MoH (SI) 41 | 6 mo–lifelong | Abrupt a >4 wk | – | – |

| NCCMH 36 | >6 mo–>2 yr | Abrupt b –4 wk–longer | Seek advice from practitioner; monitoring and reassurance; resume AD and taper more gradually; start another AD with longer half-life and taper more gradually; counsel patients; abrupt withdrawal | – |

AACAP, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; AAP, American Academy of Pediatrics; ACP, American College of Physicians; AD, antidepressant; AHCPR, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Practice Guidelines; APA, American Psychological Association; BAP, British Association for Psychopharmacology; CANMAT, Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments; HIS, Healthcare Improvement Scotland; HSE, Health Service Executive; ICGP, College of General Practitioners; mADM, maintenance antidepressant medication; mo, months; MoH (Si), Ministry of Health, Singapore; NCCMH, National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NZ, New Zealand; NZGG, New Zealand Guidelines Group; RANZCP, Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists; RCPSYCH, Royal College of Psychiatrists; SIGN, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; VA/DoD, Department of Veteran Affairs and Department of Defense; WFSBP, World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry; WHO, World Health Organization; wk, weeks; yr, years.

‘Fluoxetine dose of 20 mg can be abruptly stopped and doses of above 20 mg recommended to reduce over a period of 2 weeks’.

‘This is not required with fluoxetine because of its long half-life’.

Guidance on duration of tapering period and specific tapering regimen

Discontinuing antidepressants by gradually tapering the dose was recommended in 15 (71%) of the CPGs. Nine (43%) of the CPGs recommended a certain period of time to taper1,2,36,39,41,44,45,47 ranging from at least 4 weeks1,2,39,41,47 to 6 months (Table 4), 44 six (29%) of the CPGs did not specify the duration of taper, but recommended that antidepressants be ‘tapered/discontinued slowly over an extended period of time’,3,26,27,48 or to ‘taper over at least several weeks’,28,37 and the remaining six of the CPGs provided no guidance related to tapering. Rapid or abrupt discontinuation was suggested in two (10%) of the CPGs, either when serious adverse events occurred 2 or for patients experiencing discontinuation symptoms despite a slow taper. 36 Specific guidance for short half-life drugs was provided in four (19%) CPGs, recommending ‘a longer’ taper;1,28,36,41 and one stated that ‘tapering should be guided by the elimination half-life of the medication’, but without providing concrete guidance. 27 Specific guidance for tapering monoamine oxidase inhibitors was provided in one (5%) of the CPGs, recommending ‘tapering over a longer period’, 36 and for tapering tricyclic antidepressants in one (5%) of the CPGs, recommending ‘a slow taper over a longer period of time’. 3

Only two (10%) of the CPGs alluded to some form of guidance based on a specific dose-reduction regimen. Thus, one (5%) of the CPGs recommended halving the dose before discontinuation, 41 and one (5%) of the CPGs suggested that patients in high risk of severe discontinuation symptoms reduce the dose first to the minimal effective dose, then halve that dose, and then ‘reduce more slowly in small decrements, allowing 2 weeks for each dose reduction, according to how the tablet can be divided. [...] once minimum effective dose is achieved, reduce the dose by no more than 50% weekly’. 3

Guidance on when to consider discontinuing antidepressant drug treatment

Maintenance antidepressant treatment after symptomatic remission was recommended in 17 (81%) of the CPGs,1–3,26–28,33,35–37,39,41,42,44,45,47,48 the majority recommending a period of 6 months,1–3,26,27,33,36,37,39,41,42,44,45,48 although some CPGs recommended longer periods depending on the clinical situation and course of the illness. Only two (10%) of the CPGs, however, explicitly recommended that patients should discontinue their antidepressant after maintenance treatment 3 or continuation treatment; 28 the remaining CPGs provided no direct guidance on what to do when maintenance treatment ends. Other potential reasons for considering discontinuing antidepressants were pregnancy in three (14%) of the CPGs,39–41 if symptoms of mania develop in one CPG (5%), 47 and if side effects develop early during treatment in two (10%) of the CPGs.1,36

Guidance on actions if withdrawal symptoms emerge

Some form of guidance on how to manage withdrawal symptoms was mentioned in five (24%) of the CPGs.1,2,28,36,39 These recommendations included single statements on providing an explanation and reassurance (n = 4, 19%),1,2,28,36 monitoring symptoms (n = 2, 10%),1,36 resuming the antidepressant and tapering more slowly (n = 4, 19%),1,2,36,39 tapering more gradually (n = 1, 5%), 28 switching to fluoxetine and stopping after withdrawal symptoms have resolved (n = 2, 10%),2,28 and switching to a similar drug with longer half-life and then taper more gradually while monitoring symptoms (n = 2, 10%).1,36 No other details or elaboration were provided.

Mention of potential benefits and harms associated with tapering and discontinuing antidepressants

The potential for withdrawal symptoms to emerge upon discontinuing or reducing antidepressants was mentioned in 15 of the (71%) CPGs,1–3,26–28,33,36,37,39,41,42,44,45,48 and depressive relapse/recurrence was mentioned as a potential harm in 14 (67%) CPGs.1–3,26–28,36,39–41,44,45,47,48 In 12 (57%) CPGs, both withdrawal symptoms and relapse/recurrence were mentioned as potential harms (Table 3), and of these, 4 (19%) included a specific statement on the risk of misinterpreting withdrawal symptoms as depressive relapse, stating that withdrawal symptoms may ‘mimic’, 48 ‘be misdiagnosed as’, 2 ‘mistaken for’ 28 or ‘be hard to distinguish from’ 36 relapse of depressive symptoms. Two (10%) other CPGs stated that withdrawal symptoms and relapse should be differentiated from each other when discontinuing antidepressants, but without considering the potential overlap of symptoms between these situations.3,44

Potential benefits of coming off antidepressant were not mentioned in any CPG.

Psychological challenges and supportive measures when tapering and discontinuing antidepressants

None of the CPGs mentioned or provided guidance on any psychological challenges to discontinuing antidepressants or mentioned psychological or peer-support measures to support patients coming off antidepressants.

Patients’ views and preferences on tapering and discontinuing antidepressants

None of the CPGs stated having sought patients’ views and preferences on issues related to tapering and discontinuing antidepressants. Qualitative studies on patients’ experiences were similarly not included in any of the CPGs.

AGREE II quality assessment

Outcomes of our AGREE 2 appraisal are presented in Table 5. CPG quality was generally rated as low and varied considerably between CPGs and within the domains. The overall rating of the guidance on tapering and discontinuing antidepressants ranged between 8% and 33% (mean 17%, SD 8%). No CPG reached the pre-defined score of >70% in all domains indicating ‘high quality’. Details on the assessment of each domain are provided in Supplementary Table 4.

Table 5.

Quality appraisal of guidance on stopping and tapering antidepressants in clinical practice guidelines on depression using the AGREE II tool.

| Guideline | AGREE II domain scores (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Overall | |

| BAP 2 | 58 | 44 | 14 | 28 | 0 | 38 | 17 |

| RANZCP 3 | 39 | 39 | 18 | 39 | 0 | 42 | 25 |

| HSE + ICGP 42 | 31 | 25 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| CANMAT 37 | 50 | 28 | 25 | 19 | 6 | 50 | 8 |

| WFSBP 44 | 64 | 22 | 19 | 31 | 0 | 25 | 17 |

| AAP 26 | 78 | 44 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 8 |

| SIGN + HIS 40 | 75 | 50 | 27 | 22 | 0 | 4 | 8 |

| VA/DoD 27 | 78 | 61 | 50 | 17 | 8 | 8 | 17 |

| WHO46,47 | 94 | 69 | 43 | 11 | 27 | 58 | 17 |

| American Psychiatric Association 28 | 42 | 11 | 27 | 19 | 0 | 38 | 25 |

| NZGG + MoH (NZ) 29 | 78 | 47 | 24 | 25 | 17 | 71 | 25 |

| NICE 33 | 92 | 78 | 41 | 17 | 13 | 42 | 25 |

| WFSBP 45 | 58 | 19 | 22 | 19 | 4 | 25 | 17 |

| AACAP 48 | 53 | 14 | 27 | 19 | 0 | 13 | 17 |

| NICE 1 | 83 | 83 | 43 | 33 | 21 | 54 | 33 |

| RCPSYCH 35 | 33 | 3 | 30 | 14 | 0 | 17 | 8 |

| MoH (SI) 41 | 50 | 56 | 18 | 25 | 4 | 0 | 8 |

| NCCMH 36 | 56 | 58 | 36 | 33 | 8 | 50 | 25 |

| Mean (SD) | 62 (20) | 42 (23) | 27 (12) | 21 (10) | 6 (8) | 30 (22) | 17 (8) |

AACAP, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; AAP, American Academy of Pediatrics; APA, American Psychological Association; BAP, British Association for Psychopharmacology; CANMAT, Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments; HIS, Healthcare Improvement Scotland; HSE, Health Service Executive; ICGP, College of General Practitioners; MoH (Si), Ministry of Health, Singapore; NCCMH, National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NZ, New Zealand; NZGG, New Zealand Guidelines Group; RANZCP, Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists; RCPSYCH, Royal College of Psychiatrists; SD, Standard deviation; SIGN, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; VA/DoD, Department of Veteran Affairs and Department of Defense; WFSBP, World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry; WHO, World Health Organization. Values represent the mean of the scores of individual researchers. Domain 1: scope and purpose; domain 2: stakeholder involvement; domain 3: rigour of development; domain 4: clarity of presentation; domain 5: applicability; domain 6: editorial independence.

Discussion

For this first systematic review of guidance on tapering and discontinuing antidepressants in CPGs on depression, we included 21 CPGs issued by national health authorities and major national or international professional organisations or societies in English-speaking high-income countries.

We found that most CPGs recommended that antidepressants are tapered slowly or gradually when discontinued but that very few CPGs specified what was understood by gradual or slow tapering or provided any concrete guidance on a specific dose-reduction regimen. None of the CPGs included the antidepressant discontinuation phase in their treatment algorithms or flow charts, and guidance or considerations on when to discontinue antidepressant treatment was generally scarce with very few CPGs explicitly recommending discontinuing antidepressants after maintenance or continuation treatment. Although most CPGs mentioned that withdrawal symptoms can occur, they rarely considered how to address potential withdrawal symptoms and help patients manage them, and potential psychological challenges were not addressed in any CPG. The quality of the CPGs, as assessed using the AGREE II tool, was overall low and none reached our pre-defined threshold for ‘high-quality’.

Implications

Our findings have several clinical implications. First, the limited and vague guidance on tapering and discontinuation in current CPGs, which was hard to find in many cases, means that they provide little support for clinicians seeking to help patients stop or taper antidepressants. This may have the consequence that clinicians are hesitant to support patients in a process of discontinuing antidepressants. Second, the recommendation in the majority of the CPGs to taper over a given period of time, without considering the specific dosing regimen, implied that the tapering suggested was a linear one and that a proper taper was defined as a slow taper in terms of overall duration. This may be problematic as taper duration is subordinate if the dose reductions involve a high risk of causing withdrawal symptoms. This has been suggested to be the case for antidepressants when tapering using standard available doses, especially for the last reductions before cessation due to the large biological effects even at very low and subtherapeutic doses.12,16,49 Withdrawal symptoms have thus been reported even after very small dose reductions, especially in the lower dose range, 12 which would not be mitigated by even the slowest taper, as what is needed is smaller dose reductions, not longer time. The hyperbolic relationship between antidepressant dose and occupancy of their primary target receptor, the serotonin transporter, 49 suggests that the gradual reduction in the biological effect likely necessary to mitigate withdrawal symptoms requires a hyperbolic dose-reduction regimen. 12 This requires performing multiple dose reductions even below half of the lowest standard manufactured doses, which is practically impossible using standard available doses, as the pills are simply too potent at very low doses and cannot be evenly split into small enough units. Such a regimen was not recommended by any CPG. Third, the symptomatic overlap between potential withdrawal symptoms and depressive symptoms was acknowledged in only very few CPGs, and guidance on how to discern between these two fundamentally different clinical situations was not provided. Lack of such guidance may have the consequence that drug treatment is continued unnecessarily in some patients if withdrawal reactions are misdiagnosed as relapse, potentially leading to resuming drug treatment under the false assumption that the antidepressant was necessary to prevent relapse. Better and more concrete guidance could potentially help distinguish clinically between patients who deteriorate due to withdrawal from those with genuine relapse. Finally, the lack of guidance on supporting patients manage withdrawal symptoms, including psychological- and peer-support measures, may lead some patients experiencing such symptoms to stop ongoing efforts to discontinue antidepressants. Recommendations in CPGs on various supportive measures and their implementation could provide valuable help for clinicians aiming to support patients discontinuing or tapering antidepressants just as guidance on helping patients minimise potential psychological dependency of antidepressants treatment would be helpful.

Our findings also have implications for research and the possibility to provide evidence-based guidance for clinicians. First, the limited clinical evidence-base for any tapering or discontinuation regimen poses a challenge for guideline developers wishing to provide concrete, evidence-based recommendations. Thus, randomised clinical trials (RCTs) investigating interventions for tapering and discontinuing antidepressants are few and have important methodological limitations, and the certainty of the evidence is, taken together, very low. 20 These limitations in the supporting evidence-base were largely unacknowledged in the CPGs, however. In the absence of RCTs, tapering guidance could be informed by other types of evidence such as non-randomised and retrospective studies of tapering strips,17,18 pharmacologically rational theory on withdrawal symptoms and dose-reduction regimens,12,49 patients’ experiences of undergoing withdrawal, 50 and expert knowledge, 51 which could be synthesised for that purpose. Until RCT data become available, such lines of evidence could potentially support recommendations to clinicians on how to help patients taper antidepressants; importantly, while emphasising the inherent limitations of such types of evidence. Generally, an approach to tapering of trial and error with shared decision-making, acknowledging the many uncertainties of antidepressant tapering and withdrawal symptoms, may be recommended at this stage. Second, the low quality of the guidelines as assessed using AGREE II point to a need for future CPGs to improve in several areas, especially those concerning the rigour of development and the clarity of presentation, including clearly linking supporting evidence with recommendations and to make clear when recommendations are based on low certainty evidence and to make recommendations on tapering and discontinuation clear and readily accessible.

Limitations

Our study has several review-level limitations. First, we only included CPGs published in English and may thus have missed CPGs that impact clinical practice in non-English-speaking countries, where we encourage a similar systematic review to be conducted. However, given our inclusion criteria, we believe we are likely to have included those CPGs that internationally have the most impact on clinical practice. Second, there are no validated threshold in the AGREE II tool to distinguish between high- and low-quality CPGs and the cutoff we used, while suggested in the AGREE II guidance, may by some be considered too conservative. Third, the categorisation of recommendations and the quality appraisal using AGREE II involves subjective judgements, and it is possible that others would have interpreted the data differently than we did. We adhered to prespecified methods outlined in our protocol with two independent researchers doing duplicate data extraction and quality appraisal and feel confident that most readers would arrive at the same conclusions we did; our judgements and other extracted data, including supporting statements pertaining to guidance on stopping or tapering in the CPGs and AGREE II assessment forms, are provided as Supplementary Tables.

Conclusion

Current major CPGs provide only scarce and vague guidance to clinicians on how to help patients taper and discontinue antidepressants safely. The guidance provided, which often implied the use of linear tapering of antidepressants, could potentially increase the risk of withdrawal symptoms, and the lack of guidance on the practical distinction between withdrawal and relapse could lead to unnecessary long-term treatment in some patients. Better guidance requires better randomised trials investigating interventions for discontinuing or tapering antidepressants.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tpp-10.1177_20451253211067656 for Clinical practice guideline recommendations on tapering and discontinuing antidepressants for depression: a systematic review by Anders Sørensen, Karsten Juhl Jørgensen and Klaus Munkholm in Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology

Footnotes

Author contributions: Anders Sørensen: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Validation; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing

Karsten Juhl Jørgensen: Conceptualization; Methodology; Supervision; Validation; Writing – review & editing

Klaus Munkholm: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Supervision; Validation; Writing – review & editing.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Anders Sørensen  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5850-7854

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5850-7854

Data availability: All data is available in the published article and the accompanying online supplemental material.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Anders Sørensen, Copenhagen Trial Unit, Centre for Clinical Intervention Research, The Capital Region, Copenhagen University Hospital – Rigshospitalet, Blegdamsvej 9, 2100 København Ø, Denmark.

Karsten Juhl Jørgensen, Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Odense (CEBMO) and Cochrane Denmark, Department of Clinical Research, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark; Open Patient data Explorative Network (OPEN), Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark.

Klaus Munkholm, Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Odense (CEBMO) and Cochrane Denmark, Department of Clinical Research, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark; Open Patient data Explorative Network (OPEN), Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark.

References

- 1. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Depression in adults: recognition and management, 2009, https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90/resources/depression-in-adults-recognition-and-management-pdf-975742636741 [PubMed]

- 2. Cleare A, Pariante CM, Young AH, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating depressive disorders with antidepressants: a revision of the 2008 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines. J Psychopharmacol 2015; 29: 459–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Malhi GS, Bell E, Bassett D, et al. The 2020 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2021; 55: 7–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Davies J, Read J. A systematic review into the incidence, severity and duration of antidepressant withdrawal effects: are guidelines evidence-based? Addict Behav 2019; 97: 111–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lerner A, Klein M. Dependence, withdrawal and rebound of CNS drugs: an update and regulatory considerations for new drugs development. Brain Commun 2019; 1: fcz025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nielsen M, Hansen EH, Gøtzsche PC. What is the difference between dependence and withdrawal reactions? A comparison of benzodiazepines and selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors: SSRi and dependence. Addiction 2012; 107: 900–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fava GA, Gatti A, Belaise C, et al. Withdrawal symptoms after selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation: a systematic review. Psychother Psychosom 2015; 84: 72–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maund E, Dewar-Haggart R, Williams S, et al. Barriers and facilitators to discontinuing antidepressant use: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. J Affect Disord 2019; 245: 38–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Leydon GM, Rodgers L, Kendrick T. A qualitative study of patient views on discontinuing long-term selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Fam Pract 2007; 24: 570–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Verbeek-Heida PM, Mathot EF. Better safe than sorry – why patients prefer to stop using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants but are afraid to do so: results of a qualitative study. Chronic Illn 2006; 2: 133–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eveleigh R, Speckens A, van Weel C, et al. Patients’ attitudes to discontinuing not-indicated long-term antidepressant use: barriers and facilitators. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2019; 9: 2045125319872344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Horowitz MA, Taylor D. Tapering of SSRI treatment to mitigate withdrawal symptoms. Lancet Psychiatry 2019; 6: 538–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Geffen EC, Hugtenburg JG, Heerdink ER, et al. Discontinuation symptoms in users of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in clinical practice: tapering versus abrupt discontinuation. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2005; 61: 303–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Murata Y, Kobayashi D, Imuta N, et al. Effects of the serotonin 1A, 2A, 2C, 3A, and 3B and serotonin transporter gene polymorphisms on the occurrence of paroxetine discontinuation syndrome. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2010; 30: 11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Himei A, Okamura T. Discontinuation syndrome associated with paroxetine in depressed patients: a retrospective analysis of factors involved in the occurrence of the syndrome. CNS Drugs 2006; 20: 665–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ruhe HG, Horikx A, van Avendonk MJP, et al. Tapering of SSRI treatment to mitigate withdrawal symptoms. Lancet Psychiatry 2019; 6: 561–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Groot PC, van Os J. Outcome of antidepressant drug discontinuation with tapering strips after 1-5 years. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2020; 10: 2045125320954609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Groot PC, van Os J. Successful use of tapering strips for hyperbolic reduction of antidepressant dose: a cohort study. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2021; 11: 20451253211039327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Maund E, Stuart B, Moore M, et al. Managing antidepressant discontinuation: a systematic review. Ann Fam Med 2019; 17: 52–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Van Leeuwen E, van Driel ML, Horowitz MA, et al. Approaches for discontinuation versus continuation of long-term antidepressant use for depressive and anxiety disorders in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021; 4: CD013495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ 2010; 182: E839–E842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015; 4: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Johnston A, Kelly SE, Hsieh S-C, et al. Systematic reviews of clinical practice guidelines: a methodological guide. J Clin Epidemiol 2019; 108: 64–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zuckerbrot RA, Cheung A, Jensen PS, et al. Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC): part I. Practice preparation, identification, assessment, and initial management. Pediatrics 2018; 141: e20174081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cheung AH, Zuckerbrot RA, Jensen PS, et al. Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC): part II. Treatment and ongoing management. Pediatrics 2018; 141: e20174082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Department of Veteran Affairs (VA), Department of Defense (DoD). VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of major depressive disorder, 2016, https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/mdd/VADoDMDDCPGFINAL82916.pdf

- 28. American Psychiatric Association (APA). Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29. American Psychological Association (APA). Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of depression across three cohorts. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Qaseem A, Barry MJ, Kansagara D. Nonpharmacologic versus pharmacologic treatment of adult patients with major depressive disorder: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2016; 164: 350–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP). Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. AACAP. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998; 37: 63S–83S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schulberg HC, Katon W, Simon GE, et al. Treating major depression in primary care practice: an update of the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Practice Guidelines. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55: 1121–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Depression in children and young people – identification and management, 2019, www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng134 [PubMed]

- 34. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Depression: evidence update April 2012: a summary of selected new evidence relevant to NICE clinical guideline 90 ‘The treatment and management of depression in adults’ (2009). London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Baldwin RC, Anderson D, Black S, et al. Guideline for the management of late-life depression in primary care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003; 18: 829–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCCMH). Depression – the NICE guideline on the treatment and management of depression in adults. Updated ed., https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90/evidence/full-guideline-pdf-4840934509

- 37. Kennedy SH, Lam RW, McIntyre RS, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: section 3. Can J Psychiatry 2016; 61: 540–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lam RW, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: introduction and methods. Can J Psychiatry 2016; 61: 506–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. New Zealand Guidelines Group. Identification of common mental disorders and management of depression in primary care. An evidence-based best practice guideline, 2008, https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/depression_guideline.pdf

- 40. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Management of perinatal mood disorders, 2012, www.sign.ac.uk

- 41. Ministry of Health, Singapore. Depression. MOH clinical practice guidelines, 2012, https://www.moh.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider4/guidelines/depression-cpg_r14_final0147b0b18c63417ebd084c2d613dc83d.pdf

- 42. Health Service Executive (HSE), Irish College of General Practitioners (ICGP). Guidelines for the management of depression and anxiety disorders in primary care, 2006, https://www.icgp.ie/go/courses/mental_health/articles_publications/77EDAF46-04AE-0864-D254112C3BA5A247.html

- 43. Bauer M, Pfennig A, Severus E, et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of unipolar depressive disorders, part 1: update 2013 on the acute and continuation treatment of unipolar depressive disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry 2013; 14: 334–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bauer M, Severus E, Köhler S, et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of unipolar depressive disorders. Part 2: maintenance treatment of major depressive disorder-update 2015. World J Biol Psychiatry 2015; 16: 76–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bauer M, Bschor T, Pfennig A, et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of unipolar depressive disorders in primary care. World J Biol Psychiatry 2007; 8: 67–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. World Health Organization (WHO). WHO mhGAP guideline update – update of the mental health gap action programme (mhGAP) guideline for mental, neurological and substance use disorders, 2015, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549417 [PubMed]

- 47. World Health Organization (WHO). mhGAP intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings, version 2.0, 2016, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549790 [PubMed]

- 48. American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP). Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007; 46: 1503–1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sørensen A, Ruhé HG, Munkholm K. The relationship between dose and serotonin transporter occupancy of antidepressants – a systematic review. Mol Psychiatry. Epub ahead of print 21 September 2021. DOI: 10.1038/s41380-021-01285-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. White E, Read J, Julo S. The role of Facebook groups in the management and raising of awareness of antidepressant withdrawal: is social media filling the void left by health services? Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2021; 11: 2045125320981174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Framer A. What I have learnt from helping thousands of people taper off antidepressants and other psychotropic medications. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2021; 11: 2045125321991274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tpp-10.1177_20451253211067656 for Clinical practice guideline recommendations on tapering and discontinuing antidepressants for depression: a systematic review by Anders Sørensen, Karsten Juhl Jørgensen and Klaus Munkholm in Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology