Abstract

Cancer is a mortality contributor worldwide, and breast cancer is the most common among women. Despite the numerous breast cancer therapeutic strategies, they either have limitations or sometimes are resisted by cancer, so new approaches are needed to tackle those restrictions. Nanotechnology offers exciting leaps in the diagnosis and treatment of cancer, especially breast cancer. The main objective of this study was to investigate the effect of the newly synthesized gallium nanoparticles coated by Ellagic acid (EA-GaNPs) on the induced mammary gland carcinogenesis in female rats and their antibacterial activities comparison with standard antibiotics (Ketoconazole (100 μg/ml) and Gentamycin (4 μg/ml)) by disc diffusion method using eight different microbial species. The antitumor efficacy of EA-GaNPs was conducted both in vitro and in in vivo. The result of antimicrobial activity of EA-Ga NPs (1 mg/1 mL) revealed moderate toxicity behavior against Gram-positive {Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus cereus) and Gram-negative pathogenic bacteria {Escherichia coli, Proteus vulgarfs) also, antifungal activity was detected against {Aspergillus terreus). In vitro study showed that EA-GaNPs inhibited human breast cancer cell line (MCF-7) proliferation with IC50 of 2.86 μg/ml. Although in vivo; the administration of EA-GaNPs to DMBA-treated rats ameliorated the hyperplastic state of mammary gland carcinogenesis induced by DMBA. Additionally, EA-GaNPs administration significantly modulated the activities of ALT and AST, as well as the levels of urea and creatinine in serum. Also, EA-GaNPs administration improved the antioxidant state by increasing Superoxide dismutase activity and GSH content, and decreasing malondialdehyde content in the mammary tissue, besides enhancing the apoptotic activity through elevating the levels of caspase-3 and decreasing the protein intensities of protein kinase B & phosphatidyl inositide 3-kinases. Furthermore, a significant decrease in serum Total iron-binding capacity accompanied by a significant increase in the level of calcium was noted. So, it can be concluded that the newly synthesized nanoparticles EA-GaNPs have an efficient antitumor activity that was manifested by reduction of the viability on the human breast cancer cell line (MCF-7) in vitro. Also, in vivo against the chemically induced mammary gland carcinogenesis in a female rat model. Histopathological findings were in harmony with biochemical and molecular results showing the effectiveness of EA-GaNPs against mammary carcinogenesis. Therefore, EA-GaNPs could be a promising, potent anti-cancer compound.

Keywords: EA-GaNPs; 7, 12-Dimethy1benz[a] Anthracene; protein kinase B; phosphatidyl inositide 3-kinases; Caspase-3; antioxidants

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer among women worldwide accounting for almost 1 in 4 female cancer cases and is considered as the second leading cause of cancer death with nearly 2.1 million new cases diagnosed in 2018, accounting for 11.6% of all newly diagnosed cancer cases and 6,6 % of all Cancer Deaths in 2018. 1

Increasing incidence and mortality of breast cancer ascribed to various risk factors, the predominant LSD factors are genetic vulnerability (mutations in BRCA 1 and BRCA 2), exposure to radiation, overweight and obesity, and alcohol addiction. Furthermore, breast cancer is associated with age and estrogen exposure. Asteroidal hormone, principally estrogen, can cause the induction and growth of breast cancer. 2

Breast cancer is usually treated with surgery, which may be followed by chemotherapy or radiation therapy, or both. Those conventional breast cancer therapies have limitations as they are not usually successful in curing metastatic stages. 3 Also, radio or chemotherapeutic agents are not targeted sufficiently; cause systemic effects and have poor penetration at the intended treatment site. 4

Pathogenic microbes are considered a serious problem as cancer may be stimulated by microbial infection and remain a serious problem in patients with advanced cancer. Thus, most patients treated with antineoplastic drugs are potential recipients of antimicrobial drugs. Very often these drugs have to be given in combination. Although synergistic and antagonistic actions between antibacterial drugs have been well documented, that raised the need for anticancer drugs to have the activity against bacterial infections, which enhanced researchers for repurposing of anticancer drugs for the treatment of bacterial infections. 5

Therefore, there is a need for new strategies or a new generation of drugs that can overcome those limitations. Nanotechnology, through using nanoparticles, offers exciting leaps forward in the diagnosis and treatment of cancer which tackles the limitations of conventional therapeutic strategies. The therapeutic approaches of nanoparticles are based on rectifying the damaging mechanism of the genes or by stopping the blood supply to the cancer cells or destroying the cancer cells themselves. 6 Due to the advantages of nanoparticles as they have a high surface area to volume ratio which allows many functional groups to be attached to a nanoparticle, which also can seek out and bind to certain tumor cells. 7

Additionally, the small size of nanoparticles (1 to 100 nm), allows them to accumulate at tumor sites. 8 Recently and because of the medical importance of nanoparticles, they have been synthesized biologically via eco-friendly, cost-effective methods using microorganisms, enzymes, fungus and plants or plant extracts. 9

Gallium (Ga) is considered the second metal after platinum with clinical antitumor activity. 10 The antiproliferative activity of Ga depends mainly on the mimic action of Ga3+ with Fe3+, so Ga acts on cellular iron-dependent processes at various points in the cell to disrupt tumor growth. 11

Ellagic acid (EA) naturally occurring polyphenolic constituent that is contained in many fruits and nuts as grapes, pomegranate, red raspberry, strawberry, blueberry, walnuts, and cashew nuts, 12 is known for its potent antioxidant activity, radical scavenging capacity, chemopreventive and antiapoptotic properties. 13 In vitro and in vivo experiments have revealed that EA elicits anticarcinogenic effects by inhabiting tumor cell proliferation, inducing apoptosis, breaking DNA binding to carcinogens, blocking virus infection, and disturbing inflammation, angiogenesis, and drug-resistance processes required for tumor growth and metastasis. 12

Accordingly, the main object of this study was to investigate the effect of the newly synthesized gallium nanoparticles coated by Ellagic acid (EA-GaNPs) on the induced mammary gland carcinogenesis in female rats.

Due to the fact of relying on the basic mechanism of cancer development primarily on DNA damage-induced through several protein clusters and pathways (signaling pathways), the present work studied the antitumor effect of the newly synthesized nanoparticles through proteomic quantitation of two selected candidate proteins (phosphatidyl inositide 3-kinases (PI3K) and protein kinase B (AKT)) by western blot, as the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway is one of the most frequently deregulated pathways in cancer as it controls key cellular processes, such as metabolism, motility, growth, and proliferation, that support the survival, expansion and dissemination of cancer cells, in addition to the oncogenic activation of the PI3K—AKT—mTOR pathway often occurs alongside pro-tumorigenic aberrations in other signaling networks. 14 Also, the antimicrobial activity of the newly synthesized gallium nanoparticles coated by Ellagic acid (EA-GaNPs) was also evaluated in comparison with standard antibiotics (Ketoconazole (100 μg/ml) and Gentamycin (4 μg/ml)) by disc diffusion method using eight different microbial species.

Methods

Chemicals

7, 12-Dimethy1benz[a] Anthracene (DMBA) Was Purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Company, Saint Louis, Missouri, USA. Gallium Nitrate and Ellagic Acid Were Purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Company, Saint Louis, Missouri USA.

Cell Line

Human breast cancer (MCF-7) cell line was obtained from VACSERA Tissue Culture Unit.

Experimental Animals

Female Swiss albino rats (50-60 days old) weighing (120 ± 20 gm.) were obtained from the breeding unit of the National Research Centre (NRC), Cairo, Egypt. They were used for the in vivo study to determine the median lethal dose (LD50) and antitumor efficacy of the EA-GaNPs. The animals were housed in the animal house of the National Center for Radiation Research and Technology (NCRRT), Cairo, Egypt under standard laboratory conditions. Animals were maintained on a high protein commercial diet and water ad libitum and they were maintained for one week before starting the experiment as an acclimatization period.

Ethics Statement

The study was conducted by international guidelines for animal experiments and approved by the Ethical Committee at the National Center for Radiation Research and Technology (NCRRT), Atomic Energy Authority, Cairo, Egypt.

Chemical Study

Synthesis and Characterization of EA-GaNPs:

Gallium nanoparticles coated by Ellagic acid were synthesized (EA-GaNPs) referring to the method in the literature of Li,. 15 First, 2 mL of (Ga (NO3)3) (20 mM) was added to 46 mL of double-distilled water under magnetic stirring at room temperature. Then 2 mL of EA (10 mM) was added, and the pH value was adjusted to 11.0 with 1.0 M NaOH. Then the reaction was maintained at room temperature for 30 min. The nanoparticles were condensed and purified by centrifugation at 15 000 r.p.m for 10 min. and washed with double-distilled water three times.

Characterization of the EA-GaNPs:

Dynamic light scattering (DLS):

Sample of EA-GaNPs was analyzed for size dimensions by (DLS Zetasizer Nano ZS ZEN 3600, Malvern, UK).

Ultraviolet-visible absorption (UV/VIS) Spectroscopy:

The ultraviolet-visible spectrum of EA-GaNPs was analyzed using (the computerized double-beam ultraviolet-visible Jenway 6505 spectrophotometer, Keison, UK). The ultraviolet spectrum for EA-GaNPs sample was obtained by exposing the sample to visible light at a range of 200–900 nm. Deionized water was used for background correction of all ultraviolet-visible spectra.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) Analysis:

A scanning electron microscope (SEM) was used to identify the size, shape and morphology of EA-GaNPs using (JEOL, JSM-5400 Scanning Microscope, FEJ EUROPE, Benelux). The sample was prepared and allowed to evaporate before analysis using JEOL, JFC-1100E Ion Sputtering Device.

Fourier transforms infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR):

Samples of EA-GaNPs and EA used for the nanoparticle synthesis were analyzed for the functional group using (VERTEX 70 FT- IR Spectrometer, BRUKER) scanned in the range of 4000–400 cm−1.

Antimicrobial Assay of EA-GaNPs

The antibacterial activities of biosynthesized EA-GaNPs and standard antibiotics, including Ketoconazole (100 μg/mL), Gentamycin (4 μg/mL), were evaluated by disc diffusion method by using eight different microbial species: Aspergillus flavus, Candida albicans, Aspergillus terreus, Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus cereus, Escherichia coli, and Proteus vulgaris. Fungi strains were cultured on Sabouraud Dextrose broth at 25° C for 48 hs, while, bacteria strains were cultured in Müller-Hinton broth.

At 37°C for 20 h before the test. 100 μL of standardized suspensions for each culture, according to Mc-Farland scale (1.3 × 106 CFU/mL) of fungi were placed on Sabouraud Dextrose plate and the same cell count of bacteria were placed on Müller-Hinton agar plates using sterile cotton swab Discs of sterilized filter paper (6 mm) were loaded with tested compound and subjected to the inhibition zone tests. The discs were aseptically placed on Aspergillus flavus, Candida albicans, Aspergillus terreus, Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus cereus, Escherichia coli, P vulgaris culture plates. The agar plates of fungi were incubated for 48 h at 25°C, on the other hand, agar plates of bacteria were incubated for 24 hours at 37°C. The relative antimicrobial effect was obtained by measuring the clear zones of inhibition formed around the discs using a Vernier caliper instrument. Sabouraud Dextrose broth, Sabouraud Dextrose agar, Müller-Hinton broth, and Müller-Hinton agar media were prepared by dis. water. The antimicrobial test for all microorganisms was made in triplicate. 16

Biochemical Studies

This study was designed to involve a series of in vitro and in vivo investigations as follows.

In vitro study

EA-GaNPs cytotoxicity on MCF-7 cell line cytotoxicity of EA-GaNPs was evaluated on the human breast cancer (MCF-7) cell line using the 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-dipheny1tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay 17 which based on the mitochondrial dehydrogenase conversion of the MTT to a blue formazan product in the viable cells by an enzyme present in the mitochondria of viable cells. The colorimetric changes of blue formazan dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were measured spectrophotometrically at 570 nm using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plate reader DV990BV4 microplate reader from Gio. de Vita E C. S.r.1 (Rome, Italy) and data were analyzed using 990-win 6 software.

In vivo study

EA-GaNPs LD50

The median lethal dose which caused death to 50% of the population of the experimental animals was determined according to Bass 18 by administration of ascending doses of the EA-GaNPs ranging from 1.5 to 50 mg/kg b.w. with an increasing factor (2.0) by oral gastric intubation to female Swiss albino rats (weighing about 120 ± 20 gm), mortality was recorded after 24 hours and LD 50 was calculated as following:

Log LD50= Log LD next below 50% + (Log increasing factor x proportionate distance).

Proportionate distance

| (1) |

Experimental Design

Sixty Female Swiss albino rats weighing (120 ± 20 gm) are equally divided randomly into the following 4 groups:

Group I: Rats Were Served as Normal control

Group II: Rats were received a single dose of DMBA (20 mg/kg b.w. dissolved in 1.0 mL of olive oil) by oral gastric intubation according to Tabaczar 19 , then animals were left till the end of the experiment (8 months) for carcinogenesis induction and they were palpated weekly to monitor changes in the mammary glands.

Group III: Rats have received a daily oral dose of 1.0 mg of EA-GaNPs/kg b.w. (1/10 of LD50) at the seventh month, by gastric intubation for one month.

Group VI: Rats received a single dose of DMBA as in group II at the seventh-month rats received EA-GaNPs daily for one month as in group III.

Samples Collection:

At the end of the experiment (after 8 months), rats were fasted overnight then anesthetized using diethyl ether. Blood samples were obtained via heart puncture and collected in plain vacutainer tubes. Immediately after blood sampling, animals were sacrificed and Mammary glands were excised from animals in all groups. A portion of mammary glands was homogenized (10% w/v) in phosphate-buffered-saline (.02 M sodium phosphate buffer with .15 M sodium chloride, pH7.4) using glass homogenizer producing homogenates which were used for biochemical and molecular analysis. The other portion was quickly rinsed in 10% formalin for histopathological examination.

Biochemical Analysis

The activity of alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were estimated by the procedure described by Reitman and Frank 20 using diagnostic kits purchased from Biodiagnostic Company, Egypt. Serum creatinine and urea were determined by procedures described by Bartels 21 and Patton and Crouch, 22 respectively, using diagnostic kits purchased from Diamond Company, Egypt. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was determined according to the method of Minami and Yoshikawa 23 and reduced glutathione (GSH) was determined according to the method of Beutler. 24 Lipid peroxidation was evaluated by the determination of malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration according to the method of Yoshioka 25 . Total iron-binding capacity (TIBC) and serum calcium were measured according to the methods described by Bauer 26 and Shin, 27 respectively, using diagnostic kits purchased from Spectrum Company, Egypt. Concentration of caspase-3 was determined using an ELISA kit from Biomatik Company (Biomatik, Ontario, Canada) which based on Sandwich-ELISA principle.

Western Blotting for Quantifying of Phosphatidyl Inositide 3-kinases and Protein Kinase B in Mammary Gland Tissue

Mammary gland content of PI3K and AKT was evaluated by western blot technique according to Towbin 28 . Tissue protein was extracted using TRIzol reagent according to Wu, 29 then protein concentration was estimated according to Lowry 30 using the Thermo Scientific Modified Lowry Protein Assay kit, and β-actin antibody (Proteintech, USA) as a loading control.

Histopathological Findings

Mammary glands were fixed in 10% formalin, dehydrated using gradient alcohol concentrations and embedded in paraffin wax. Sections of 5 mm thickness were cut off paraffin wax cubs and stained with hematoxylin and eosin 33 and examined by light microscope Banchroft. 31

Gamma Irradiation Facility

Nanoparticle synthesis mixture was irradiated at a dose level of 50 kGy in the Gamma chamber 4000—A India, irradiation facility, at the National Center for Radiation Research and Technology (NCRRT), Atomic Energy Authority, Cairo, Egypt at a dose rate (1.170 kGy/h).

Statistical Analyses

Data analyses were performed using the SPSS (version 20). Data were analyzed with a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a post hoc test (LSD) for multiple comparisons. The results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for n = 6. Results were considered statistically significant at P values ≤.05.

Results

Characterization of EA-GaNPs

Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

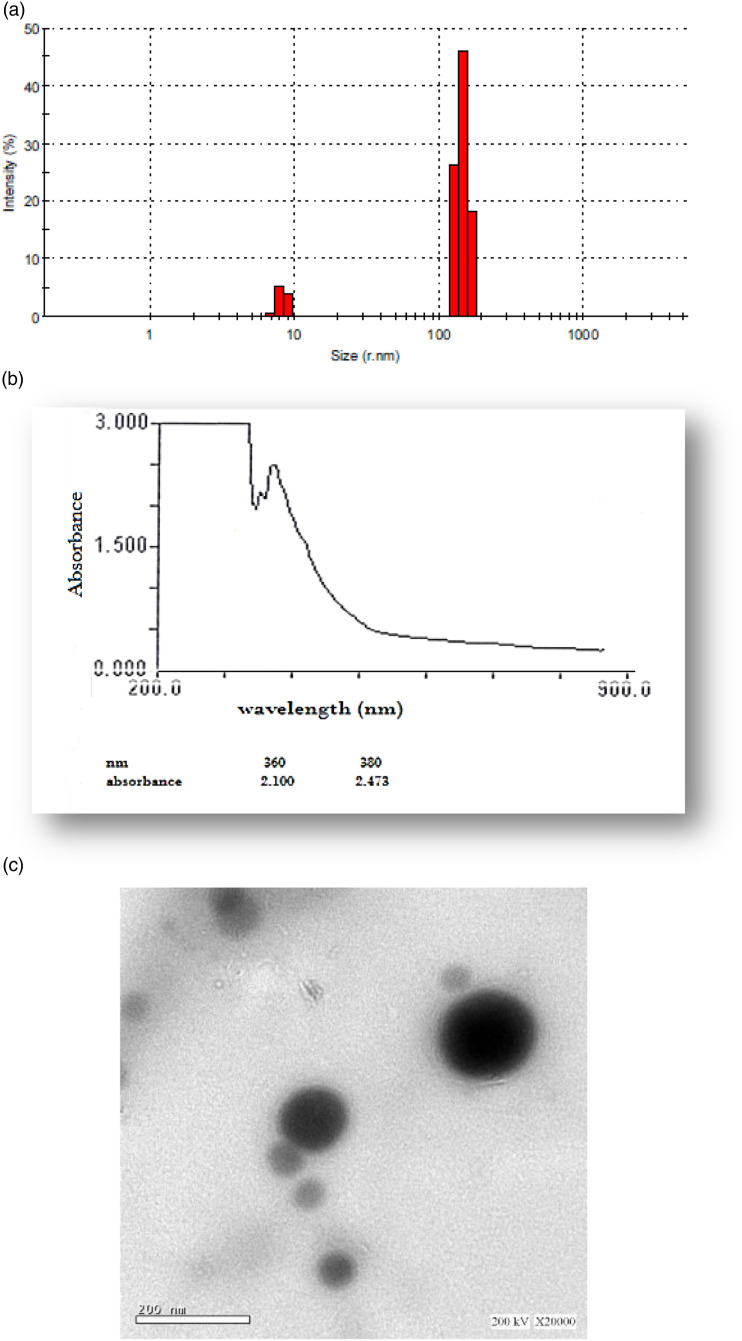

Sample of EA-GaNPs was analyzed by (DLS Zetasizer Nano ZS ZEN 3600, Malvern, UK) for size determination and the results revealed that EA-GaNPs size ranged from 5.8-10.5 nm, (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Characterization of synthesized EA-Ga NPs. (A) DLS analysis, (B) Ultraviolet-visible absorption (UV-VIS), (C) Transmission electron microscope with a magnification ×20,000, bar =200 nm.

Ultraviolet-visible Absorption (UV/VIS) Spectroscopy

UV/VIS spectroscopy absorbance of EA-GaNPs using the visible range revealed a major peak at 380 assigned to surface plasmon resonance of the nanoparticles and a narrow peak at 360 nm, (Figure lB)

Transmission Electron Microscope Analysis

The physical morphology and size distribution of the EA-GaNPs was visualized by Scanning Microscope and the results revealed that EA-GaNPs were spherical with a relatively narrow particle size distribution range between 50.8 and 100.5 nm (Figure 1C).

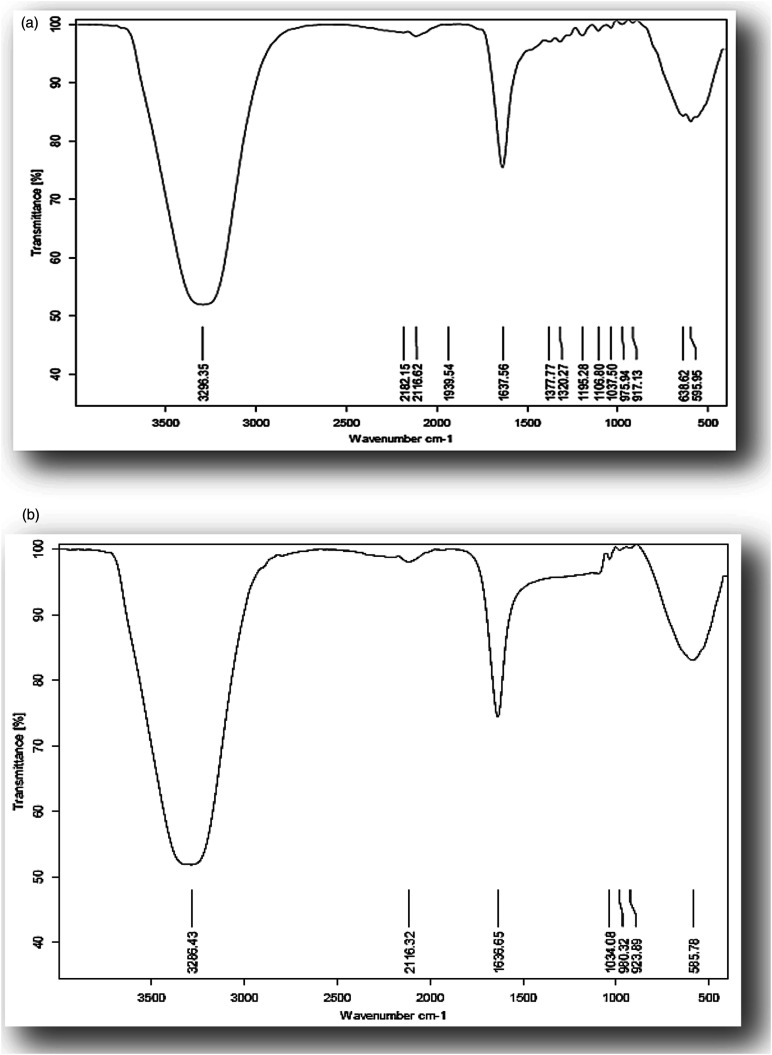

Fourier Transforms Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy

The FT-IR spectra of EA and EA-GaNPs samples are shown in Figure 2A and B, respectively. The spectrum of EA reveals strong broadband at 3286 cm - 1 assigned to the O-H stretch, a weak band at 2116 cm−1 to the aromatic bending mode of C-H, a medium band at 1636 cm−1 to stretching vibration of C=C bond, and a peek at 585 cm−1 to C-H stretching vibration. Meanwhile, the FT-IR spectrum of EA-GaNPs exhibits the same vibrational bands as EA except for a new small peak that appeared around 952 cm−1 that is assigned to the Ga-OH deformation mode of a GaO(OH) moiety. This result can be taken as evidence of the interaction of Ga and EA, that the hydroxyl group of EA acts as a capping agent in controlling the GaNPs size.

Figure 2.

FT-IR spectrum of (A) Ellagic acid, (B) EA-GaNPs.

Antimicrobial Activity of EA-Ga NPs

Evaluating antimicrobial activity of EA-Ga NPs (1 mg/1 mL) revealed moderate toxicity behavior against Gram-positive {Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus cereus) and Gram-negative pathogenic bacteria {Escherichia coli, Proteus vulgarfs) also, antifungal activity was detected against {Aspergillus terreus), (Table.1).

Table 1.

Antimicrobial Activity of EA-Ga NPs.

| Fungi | Inhibition Zone (mm) | Reference Drug Ketoconazole (100 Qg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus fiavus | NA | 16 ± 1.7 |

| Candida albicans | NA | 20 ± 2.1 |

| Aspergillus terreus | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 17 ± 1.9 |

| Gram positive bacteria | Gentamycin (4 pg/mL) | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 14 ± 1.2 | 24 ± 2.3 |

| Bacillus subtilis | 11 ± 1.1 | 26 ± 2.9 |

| Bacillus cereus | 1.2 ± .07 | 21 ± 2.3 |

| Gram negative bacteria | Gentamycin (4 pg/mL) | |

| Escherichia coli | 12 ± 1.5 | 30 ± 2.7 |

| Proteus vulgaris | 10 ± 0.9 | 25 ± 2.1 |

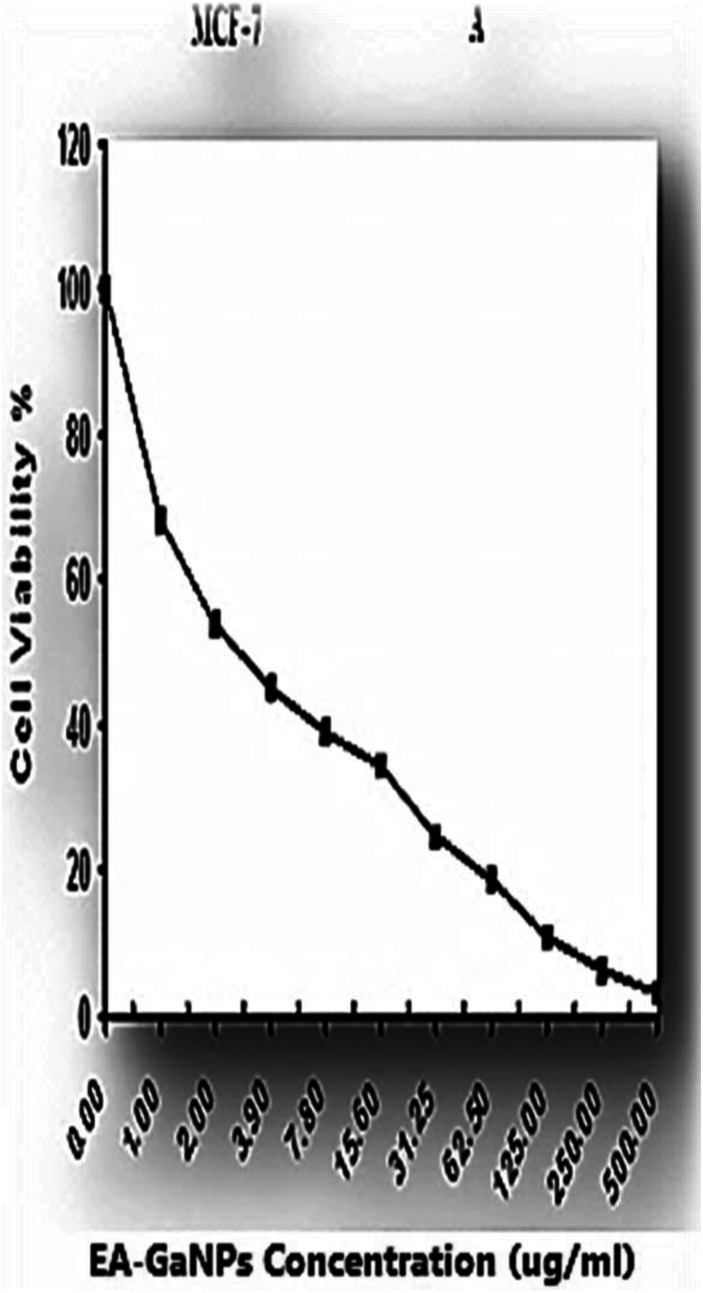

EA-Ga NPs Toxicity Against MCF-7

EA-Ga NPs induce cytotoxicity effect on MCF-7 observed as a reduction in cell viability relative to the control in a dose-response manner. The EA-GaNPs concentration which reduced MCF−7 cell count to 50% (IC50) is 2.86± .3 μg/ml (Figure 3)

Figure 3.

Antitumor efficacy of EA-GaNPs against human breast cancer cell line (MCF-7).

In Vivo Study

The LD50 of EA-GaNPs

Ascending doses of the tested EA-GaNPs ranged from 1.5 to 50.0 mg/kg b.w. With increasing factor (2) were administrated by oral gastric intubation to female Swiss albino rats (weighing about 120 + 20 gm), mortality was recorded after 24 hours. The median lethal dose (LDSO) of EA-GaNPs was approximately 10.0 mg/kg b.w.

Effect of EA-GaNPs on Liver and Kidney Function Markers

DMBA administration resulted in significant elevation of serum levels of ALT, AST, urea, and creatinine compared with the normal healthy control which was reduced significantly by treating with EA-GaNPs and that was shown in (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of EA-GaNPs on Serum Levels of ALT, AST, Urea and Creatinine.

| Groups | ALT (U/L) | AST (U/L) | Urea (mg/dl) | Creatinine (mg/dl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 16.7 ± 4.04 b | 12.2 ± 1.9 b | 41 ± 8.7 b | .14 ± .03 b |

| DMBA | 47.5 ± 5.5 a | 36.3± 4.04 a | 81.3 ± 8.5 a | .89 ± .11 a |

| EA-GaNPs | 18.7 ± 3.05 b | 16.0± 1.7 b | 39.3 ± 9.5 b | .25 ± .04 b |

| DMBA+EA-GaNPs | 31.7±4.5 a,b | 26.7± 2.5 a,b | 57.3 ± 4.04 a,b | .49 ± .04 a,b |

Data are expressed as Mean ± Standard Deviation.

aSignificance versus control group.

bSignificance versus DMBA group.

EA-GaNPs Effect on Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Parameters

The oxidative stress and antioxidant status in the mammary tissues of the DMBA group were disrupted which was noticeable by a significant increase in MDA content and significant decrease of SOD activity and GSH content compared to normal control, the condition which was modified by treating with EA-GaNPs as MDA content was significantly decreased and SOD activity and GSH content were significantly increased (Table 3).

Table 3.

EA-GaNPs Effect on MDA Level, SOD Activity and GSH Content in the Mammary Tissue.

| Groups | MDA (nmol/mg protein) | SOD (U/mg protein) | GSH (mg/mg protein) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 10.9 ± .99 b | 4.23 ± .76 b | 69.8 ± 9.98 b |

| DMBA | 42.9 ± 4.40 a | 1.03 ± .17 a | 30.3 ± 2.70 a |

| EA-GaNPs | 9.6 ± 1.420 b | 3.90 ± .74 b | 72.7 ± 2.96 b |

| DMBA+EA GaNPs | 22.5 ± 2.90 a,b | 2.60± .21 a,b | 51.8 ± 7.80 a,b |

Data are expressed as Mean ± Standard Deviation.

aSignificance versus control group.

bSignificance versus DBMA group.

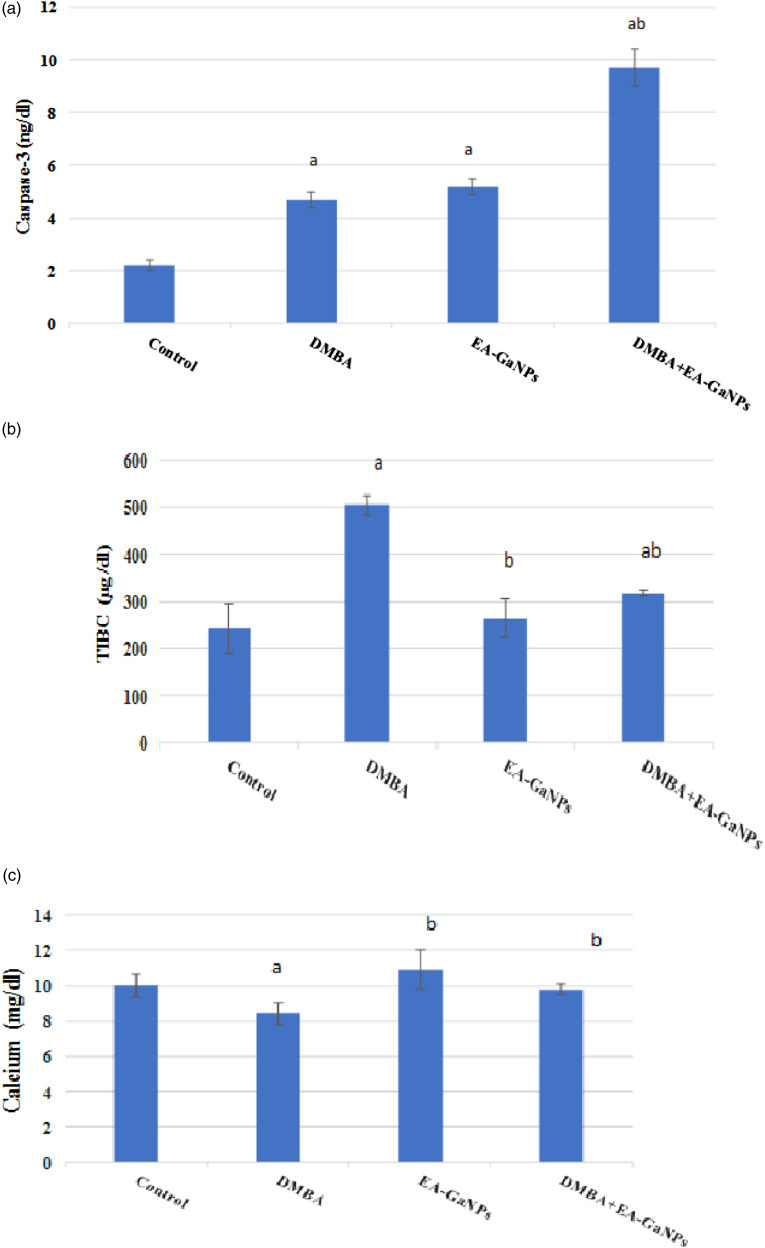

Effect of EA-GaNPs on serum values of TIBC, calcium, and caspase-3

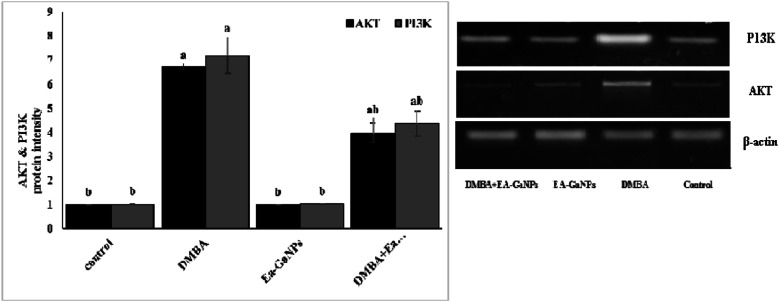

DMBA administration significantly decreased Ca concentration and increased TIBC values compared to healthy control in serum which was reversed by treating with EA-GaNPs. Also, DMBA slightly increase the concentration of caspase-3 and increased AKT & PI3K protein intensity in mammary tissue. Meanwhile, the administration of EA-GaNPs decreased AKT & PI3K protein intensity, while the concentration of caspase-3 was significantly elevated (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4.

EA-Ga NPs effect on (A) mammary tissue caspase-3 concentration, (B) serum TIBC level and (C): serum calcium level.a significance vs the control group.b significance versus DMBA group.

Figure 5.

Western immunoblotting analysis of AKT &PI3K protein intensity in the mammary tissue.

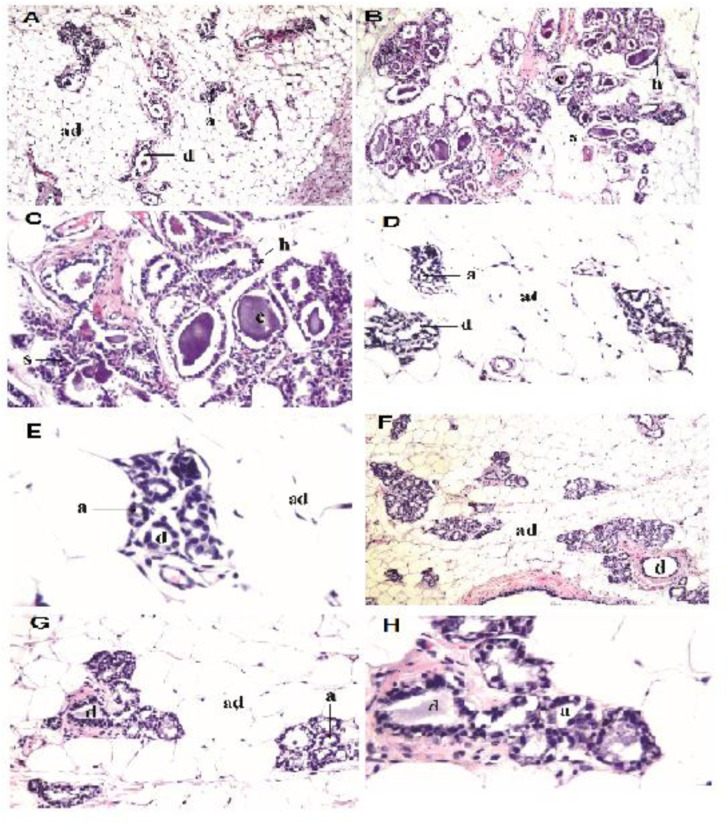

Histopathological Studies

Histopathological examination of mammary gland tissues of DMBA group under light microscope showed alterations in the architecture of the glands as the lining epithelial cells of the acini and lactiferous ducts showed proliferative hyperplasia with cystic dilatation as well as stratification. Treatment of DMBA-induced rats with EA-GaNPs showed a mild recurrence of normal mammary tissue appearance with mild stratification of the acinar lining epithelium (Figure 6)

Figure 6.

Photomicrograph of mammary gland sections in different experimental rat groups. (A) Control group; normal histological structure of the acini (a) and ducts (d) embedded in adipose tissue (ad), (H&E, 16X), (B) DMBA group; histopathological alterations in the architecture of the glands as the lining epithelial cells of the acini and lactiferous ducts showed proliferative hyperplasia (h) with cystic dilatation (c) as well as stratification (s), (H&E, ×16), (C) DMBA group; magnification of the cystic ductal dilatation(c) and the stratification (s) of the lining epithelium of the acini, (H&E, 40X).(D) EA-GaNPs group; normal histological structure of the acini (a) and ducts (d) embedded in adipose tissue, (H&E, 40X)., (E) EAGaNPs group; magnification of the normal histological structure of the acini (a) and ducts (d) embedded in adipose tissue, (H&E, 80X),(F) DMBA+EA-GaNPs group; mild recurrence of normal mammary tissue histological structure with mild stratification of the acinar lining epithelium, (H&E, ×16), (G) DMBA+EA-GaNPs group; magnification of the mild stratification of the acinar lining epithelium, (H&E, ×40) and (H) DMBA+EA-GaNPs group; magnification of the mild stratification of the acinar lining epithelium, (H&E, 80X).

Discussion

The current study was designed aiming to evaluate the antitumor efficacy of gallium nanoparticles coated by ellagic acid (EA-GaNPs) in in vitro on the viability of the human breast cancer cell line (MCF-7) and in in vivo against 7, 12 dimethyl benz[a] anthracene (DMBA)—induced mammary gland carcinogenesis in female Swiss albino rats, as well as its antimicrobial activity, was evaluated in comparison with standard antibiotics.

The biosynthesized EA- GaNPs were characterized via DLS and TEM for size dimension determination and visualization of the physical morphology and size distribution which revealed that EA-GaNPs were of spherical shape with relatively narrow particle size distribution ranged from 50.8–100.5 nm indicating their low scale as the size of nanoparticles is an important factor which significantly influences their biological activity. 32 In addition, ultraviolet-visible (UV/VIS) absorbance spectroscopy showed two narrow peaks at 360 and 380 nm and this result is in agreement with others 33 who found that gallium is sensitive to ultraviolet radiation below 365 nm wavelengths. Also, these results are in line with a previous study 34 who reported that the UV/VIS spectrum for GaNPs showed a peak at 265 nm. Furthermore, the FT-IR spectra of the EA and EA-GaNPs were investigated as FT-IR enables the in-situ analysis of interfaces to investigate the surface adsorption of functional groups on nanoparticles 35 and it can be used to identify the possible biomolecules responsible for capping and efficient stabilization of the synthesized metal NPs, The spectrum of EA reveals strong broadband at 3286 cm - 1 assigned to the O-H stretch, a weak band at 2116 cm−1 to the aromatic bending mode of C-H, a medium band at 1636 cm−1 to stretching vibration of C=C bond, and a peek at 585 cm−1 to C-H stretching vibration. Meanwhile, the FT-IR spectrum of EA-GaNPs exhibits the same vibrational bands as EA except for a new small peak that appeared around 952 cm−1 that is assigned to the Ga-OH deformation mode of a GaO(OH) moiety as reported with others. 36 This result can be taken as evidence of the interaction of Ga and EA, that the hydroxyl group of EA acts as a capping agent in controlling the GaNPs size.

The emerging infectious diseases and the development of multi-drug resistance in the pathogenic bacteria and fungi at an alarming rate is a matter of serious concern. Evaluating antimicrobial activity of EA-Ga NPs (1 mg/1 mL) revealed moderate toxicity behavior against Gram-positive {Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus cereus) and Gram-negative pathogenic bacteria {Escherichia coli, Proteus vulgarfs) also, antifungal activity was detected against {Aspergillus terreus). The NPs are potential broad-spectrum antibiotics because they can inhibit a wide range of multidrug-resistant strains of bacteria that have defied most antibiotic treatment. Nanoparticles are nano-sized molecules (usually less than 100 nm in diameter) with a large surface area to volume ratio, which helps them to easily penetrate bacterial cells. The electrostatic interaction of nanoparticles with negatively-charged bacterial surfaces draw the particles to the bacteria and promotes their penetration into the membrane. The potential of a nanoparticle promotes nanoparticle interactions with cell membranes leading to membrane disruption, bacterial flocculation, and a reduction in viability. The generation of reactive oxygen species is also a mechanism of nanoparticle antibacterial activity. 37

Further mechanisms of action of nanoparticles as antimicrobial agents include disrupting deoxyribonucleic acid during the replication and cell division of microorganisms, compromising the bacterial membrane integrity via physical interactions with the microbial cell (the physical presence of a nanoparticle most likely disrupts cell membranes in a dose-dependent manner), and releasing toxic metal ions and possessing abrasive properties which bring about lysis of cells.

Regarding the in vitro toxicity of EA-GaNPs against MCF-7, the result revealed a significant reduction of cell viability relative to control in a dose-response manner and that was in agreement with several studies in which the activity of gallium compounds has been observed in several cancer cell lines, including those for leukemia, 38 breast cancer, 39 hepatocellular carcinoma 40 and lymphoma. 41 It was found that Ga modifies the three-dimensional structure of DNA and inhibits its synthesis and modulates protein synthesis. Also, it inhibits the activity of several enzymes, such as ATPases, DNA polymerases, ribonucleotide reductase, and tyrosine-specific protein phosphatase. Ga alters plasma membrane permeability and mitochondrial functions. 10 Also, EA was found to induce apoptosis in cancer cells. 42 However, the median Lethal Dose (LD50) of EA−GaNPs did not show any signs of toxicity in normal, healthy female rats.

It was found that DMBA damages many internal organs including the liver, by inducing the production of ROS, DNA adduct formation and affecting the activities of phase I, II, antioxidant and serum enzymes 43 and consequently the activities of ALT and AST were found to be significantly increased in all DMBA—treated groups compared to control groups of several studies 43–46 that have been conducted as that are in line with the current study in which a significant elevation in the activities of ALT& AST in the serum of DMBA treated group was noted compared to the control group. Meanwhile, the administration of EA-GaNPs to the DMBA-treated group improved the elevation in the activities of ALT& AST compared with the DMBA group and that was agreed with others.47,48

DMBA administration also resulted in a significant increase in serum levels of urea and creatinine compared to the control group which was in harmony with previous studies44,45 which indicate damage in kidneys due to DMBA induced toxicity, the effect that was reversed by administration of EA-GaNPs as the results showed a significant decrease of serum urea and creatinine levels compared to the DMBA group which was in line with a previous study 47 in which tumor-induced rat groups treated with their novel compound, Betaine Tetrachloro-Gallate (BTG) complex have displayed significant decreases of plasma urea and creatinine levels with respect to DMBA-treated rats.

Administration of DMBA requires metabolic activation which produces radical cations, free radicals, and oxygenated metabolites, 49 and that was manifested in the current study through the significant increase of the MDA (lipid peroxidation marker) content within the mammary tissue homogenates by DMBA administration compared to the normal control group which was in agreement with others,50,51 this increase is attributed to the induction of DMBA to high levels of oxidative stress which resulted in the peroxidation of cell membrane lipids by generating of lipid peroxides.50,52 On the other hand, treatment with EA-GaNPs in DMBA-treated rats resulted in a significant reduction of MDA content with respect to the DMBA group. The significant reduction in lipid peroxidation level by EA-GaNPs may be attributed to the effect of EA which has been shown to exert a potent scavenging action on superoxide anion and hydroxyl anion in vitro, as well as the protective effect against lipid peroxidation. 53

Additionally, DMBA-treated rats significantly decreased the activity of SOD activity and GSH content compared with the normal group which may be due to their utilization during scavenging of the free radicals produced by DMBA.49,54 While treating of DMBA-group with EA-GaNPs significantly increased SOD activity and GSH content compared to DMBA-group which may be due to the effect of EA. As it was found that the primer mechanism of action of EA has been defined as being able to counter the negative effects of oxidative stress by aiding the regeneration of cellular antioxidants such as GSH and ascorbate and by the activation or the induction of genes responsible for expressing enzymes such as SOD, CAT, GST and NADPH: quinone oxidoreductase. 55 Also, that significant increase of SOD and GSH may be a response to elevated levels of (O2•) as a result of ROS generated by gallium administration. 56

Based on gallium’s action on iron homeostasis due to its irreducible mimic action with Fe+3 which affects several cellular functions, 57 alterations of Fe-binding capacity (TIBC) values were studied whereas the DMBA-treated group showed a significant elevation in the value of TIBC regarding the normal group which attributed to a greater requirement of malignant cells for iron which may result in decreasing of serum iron concentration as shown in previous results of others 58 when 43% of the studied cases with breast cancer had depressed serum iron levels, where the mean serum iron levels in rats with breast cancer were significantly lower than those in the control group. So it has been suggested that the neoplastic process in the organism significantly decreases iron concentration in the serum as it probably directs the iron to the developing tumor. 59 And without any doubt, the reduction of serum iron concentration results in increasing in TIBC values which were obviously in results of others, 47 the study revealed that DMBA-treated rats have a merely significant increase in TIBC mean concentration with respect to normal control rats.

On the other hand, DMBA-induced rats treated with EA-GaNPs showed a significant decrease in TIBC value compared to the DMBA group. Ga can bind to both metal binding sites on transferrin and under physiologic conditions, only about one-third of circulating transferrin is occupied by Fe, leaving the remaining two-thirds free to bind and transport gallium as transferring-gallium complexes. 41 which consequently results in decreasing of TIBC concentration. Our result was in harmony with a previous study 47 in which the administration of their novel compound (BTG) complex to tumor-bearing rats was found to significantly reduce plasma Fe and TIBC compared to the DMBA group.

It was found that calcium plays a dual role by its involvement in both proliferation/activation and apoptosis of both cancer and immune cells. 60 . So it was an important issue to track the alterations of the calcium concentration in our study.

The present study showed that DMBA administration decreased the concentration of serum calcium which may be due to the immunosuppressive effect of DMBA as it was found in several studies that DMBA affect the activation and apoptosis of B and T-cells and natural killer (NK) cells by inhibiting of Ca2+ mobilization inhibiting of Ca+2 mobilization or altering effect on Ca2+ homeostasis which was correlated with an increase in baseline levels of cytoplasmic free Ca2+ (intracellular Ca2+).61,62 That inhibition of Ca2+ mobilization and increasing of intracellular Ca2+ may be the reason for the decreasing of serum calcium level which may mean the importing of Ca2+ into the cytosol to affect the immune cells as transient small elevations (low to medium nM) of cytosolic Ca2+ will increase cell proliferation whereas sustained substantial elevations (high nM to μM) may induce apoptosis. 63

On the other hand, the current results showed that the administration of EA- GaNPs to DMBA-treated rats showed a significant increase in the concentration of serum calcium which reversed the decrease induced by DMBA. For as much the vital role of Ca2+ in the physiology and biochemistry of organisms and the cell and its regulation by various parameters, several researches are needed to study its involvement in each pathological condition.

Considering the central role of caspase-3 in executing apoptosis and the several observations that established breast cancer cell lines exhibit altered caspases-3 expression 64 . Cagnol 65 reported that caspase-3 and 9 levels were significantly decreased in several cancers. Considering the central role caspase-3 plays in executing apoptosis, it has been suggested that the loss of caspase-3 expression represents a selective event or lesion in breast cancer cells. 64 Furthermore, upon determining the levels of caspase-3 in a panel of human mammary cancer cell lines 66 observed that several breast cancer cell lines; MCF-7, BT-20T and ZR-75T, exhibit a complete lack of caspase-3 protein expression. On contrary, the current study showed that challenging female albino rats with DMBA resulted in a slight increase of caspase-3 concentration compared to the normal control, however, this increase is still below the level of significance. This finding would appear to conflict with the widely held belief that apoptosis is reduced in malignancy. The proliferation/apoptosis ratio, however, may be higher in DMBA-treated mammary glands than in the corresponding normal glands, 67 hence this increase in caspase-3 concentration was non-significant.

On the other hand, a noted increase in the concentration of caspase-3 was observed upon the administration of EA-GaNPs to DMBA-treated rats compared to DMBA-treated group and that agreed with others. 47 This result attributed to one of the known apoptotic mechanisms of Ga which are associated with activation of caspase-3 as it was found that the exposing of human leukemia/lymphoma cells to gallium nitrate or gallium maltolate resulted in initial translocation of inositol phosphatidylserine (an early marker of apoptosis) to the cell surface which followed by a loss of mitochondrial membrane potential leading to the release of cytochrome-C from the mitochondria to the cytoplasm and the activation of caspase-3 and morphological changes of apoptosis. 68 Also, the activation of the proapoptotic factor BAX and caspase-3 can be considered as a possible mechanism of cell death induced by Ga. 69

Due to the fact of relying on the basic mechanism of cancer development primarily on DNA damage-induced through several protein clusters and pathways (signaling pathways). Currently, the DMBA-group displayed a significant increase of both of AKT &PI3K protein intensity/§-actin protein expression in the mammary tissue homogenates compared to the normal control group indicating the stuck of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in “on” position which resulting in cellular surviving and that agreed with a previous study 70 who performed whole-exome and RNA sequencing on long latency mammary tumors induced by DMBA and transcriptome profiling indicated a significant activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway.

On the other hand, the treating of DMBA-group with EA-GaNPs revealed a significant decrease of both of AKT & PI3K protein intensity indicating that EA- GaNPs exert antitumor potential via downregulation of that signaling pathway which may be due to the effect of EA which was found to induce apoptosis through reducing of the PI3K/AKT pathway.71,72 And those findings may be due to the effect of EA that decreases cell proliferation through a reduction of phosphorylated STAT3, ERK, and AKT cellular signaling proteins in human prostate cancer cells (PC3) as the Western blot data indicated a decrease in the cellular concentrations of pSTAT3, pAKT, and pERK1/2 signaling pathways in a dose-dependent manner of EA.

Histopathological sections of the mammary gland tissues of the DMBA-treated group showed histopathological alterations in the architecture of the glands with respect to the control group as the lining epithelial cells of the acini and lactiferous ducts showed proliferative hyperplasia with cystic dilatation as well as stratification. This result was agreed with a previous study 73 in which one of the observed histopathological alterations in a Sprague–Dawley (SD) rat model induced (DMBA) and estrogen–progesterone (E-P) was ductal epithelial hyperplasia. While the treating of DMBA-induced rats with EA-GaNPs revealed a mild recurrence of normal mammary tissue appearance as there was no hyperplasia of the lining epithelium of the duct system and cystic ductal dilatation, the alterations that are observed in mammary tissue of DMBA-treated group, but there was a mild stratification of the acinar lining epithelium.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-dos-10.1177_15593258211068998 for Antitumor and Antibacterial Efficacy of Gallium Nanoparticles Coated by Ellagic Acid by Sawsan M El-sonbaty, Fatma SM Moawed, Eman I Kandil, and Amira M in Dose-Response

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the contribution of Dr Adel Bakeer, Professor of Pathology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Cairo University, for assistance in setting up the histopathological study.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iDs

Fatma SM Moawed https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5792-0815

Eman I Kandil https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4731-7315

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2018;68:394-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bishayee A, Mandal A, Thoppil RJ, Darvesh AS, Bhatia D. Chemopreventive effect of a novel oleanane triterpenoid in a chemically induced rodent model of breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2013;133(5):1054-1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skandarajah AR, Bruce Mann G. Selective use of whole breast radiotherapy after breast conserving surgery for invasive breast cancer and DCIS. Surgeon. 2013;11(5):278-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haq AI, Zabkiewicz C, Grange P, Arya M. Impact of nanotechnology in breast cancer. Expet Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9(8):1021-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soo V, Kwan B, Quezada H, et al. Repurposing of anticancer drugs for the treatment of bacterial infections. Curr Top Med Chem. 2017;17(10):1157-1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh OP, Nehru RM. Nanotechnology and cancer treatment. Asian J. Exp. Biol. Sci. 2008;22(2):6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seleci M, Seleci DA, Bongartz R, et al. Smart multifunctional nanoparticles in nanomedicine. BioNanoMaterials. 2016;17(1-2):33W1. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nie S, Xing Y, Kim GJ, Simons JW. Nanotechnology Applications in Cancer. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2007;9(1):257-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hasan S. A review on nanoparticles: their synthesis and types. Res J Recent Sci. 2015;4(ISC-2014):9-11. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collery P, Keppler B, Desoize CB. Gallium in cancer treatment. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2002;42:283-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chitambar CR. The therapeutic potential of iron-targeting gallium compounds in human disease: From basic research to clinical application. Pharmacol Res. 2017;115:56-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang HM, Zhao L, Li H, Xu H, Chen WW, Tao L. Research progress on the anticarcinogenic actions and mechanisms of ellagic acid. Cancer biology & medicine. 2014;11(2):92-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hussein RH, Khalifa FK. The protective role of ellagitannins flavonoids pretreatment against N-nitrosodiethylamine induced-hepatocellular carcinoma. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2014;21:589-596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janku F, Yap TA, Meric-Bernstam F. Targeting the PI3K pathway in cancer: are we making headway? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(5):273-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li D, Liu Z, Yuan Y, et al. Green synthesis of gallic acid-coated silver nanoparticles with high antimicrobial activity and low cytotoxicity to normal cells. Process Biochem. 2015:50:357-366. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pazos-Ortiz E, Roque-Ruiz JH, Hinojos-Marquez EA, et al. Dose- Dependent Antimicrobial Activity of Silver Nanoparticles on Polycaprolactone Fibers against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria. J Nanomater. 2017;2017. Article ID 4752314, 9 pages. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson J, Sargent J, Elgie A, Hill J, Taylor C. A feasibility study of the MTT assay for chemosensitivity testing in ovarian malignancy. Br J Cancer. 1990;62:189-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bass KF, Gunzel P, Henchler D. LD50 versus acute toxicity. Arch Toxicol. 1982;51:183-186. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tabaczar S, Domeradzka K, Czepas J, et al. Anti-tumor potential of nitroxyl derivative Pirolin in the DMBA-induced rat mammary carcinoma model: A comparison with quercetin. Pharmacol Rep. 2015;67:527-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reitman S, Frankel S. A Colorimetric Method for the Determination of Serum Glutamic Oxalacetic and Glutamic Pyruvic Transaminases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1957;28(1):56-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartels H, Böhmer M, Heierli C. Serum kreatininbestimmung ohne enteiweissen. Clin Chim Acta. 1972;37:193-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patton CJ, Crouch SR. Spectrophotometric and kinetics investigation of the Berthelot reaction for the determination of ammonia. Anal Chem. 1977;49:464-469. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minami M, Yoshikawa H. A simplified assay method of superoxide dismutase activity for clinical use. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry. 1979;92:337-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beutler E, Duron O, Kelly BM. Improved method for the determination of blood glutathione. J Lab Clin Med. 1963;61:882-888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshioka T, Kawada K, Shimada T, Mori M. Lipid peroxidation in maternal and cord blood and protective mechanism against activated-oxygen toxicity in the blood. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1979;135(3):372-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bauer JD, Mosby Company. Haemoglobin, porphyrin, and iron metabolism. In: Kaplan LA, Pesce AJ, eds Clinical Chemistry, Theory, Analysis, and Correlation. 1984:611-655. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin DH, Yoon KJ, Kwon SK, et al. Determination of total calcium in serum with Arsenazo III method. Korean J Clin Pathol. 1994;14(1):12-19. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci Unit States Am. 1979;76:4350-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu LC. Isolation and long-term storage of proteins from tissues and cells using TRIzol reagent. Focus. 1997;17:98-100. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lowry O, Rosebrough N, Farr AL, Randall R. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193(1):265-275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Banchroft JD, Stevens A, Turner DR. Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques. 4th edn. London, UK: Churchil Livingstone; 1996:125. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shin S, Song I, Um S. Role of physicochemical properties in nanoparticle toxicity. Nanomaterials. 2015;5:1351-1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eisenberg I, Alpern H, Gutkin V, Yochelis S, Paltiel Y. Dual mode UV/visible-IR gallium-nitride light detector. Sensor Actuator Phys. 2015;233:26-31. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kandil EI, El-sonbaty SM, Moawed FS, Khedr OM. Anticancer redox activity of gallium nanoparticles accompanied with low dose of gamma radiation in female mice. Tumour biology: The Journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. 2018;40(3):1010428317749676-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mudunkotuwa IA, Minshid AA, Grassian VH. ATR-FTIR spectroscopy as a tool to probe surface adsorption on nanoparticles at the liquid-solid interface in environmentally and biologically relevant media. The Analyst. 2014;139:870-881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang J, Zhao Y, Frost RL. Infrared and infrared emission spectroscopy of gallium oxide α-GaO(OH) nanostructures. Spectrochim Acta Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2009;74:398-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thekkae Padil VV, Černík M. Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using gum karaya as a biotemplate and their antibacterial application. Int J Nanomed. 2013;8:889-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bernstein LR. Mechanisms of therapeutic activity for gallium. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:665-82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang F, Jiang X, Yang DC, Elliott RL, Head JF. Doxorubicin-gallium-transferrin conjugate overcomes multidrug resistance: evidence for drug accumulation in the nucleus of drug resistant MCF-7/ADR cells. Anticancer research. 2000;20:799-808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chua MS, Bernstein LR, Li R, So SK. Gallium maltolate is a promising chemotherapeutic agent for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Anticancer research. 2006;26:1739-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chitambar CR. Medical Applications and Toxicities of Gallium Compounds. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2010;7:2337-2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.shirode AB, Bharali DJ, Nallanthighal S, Coon JK, Mousa SA, Reliene R. Nanoencapsulation of pomegranate bioactive compounds for breast cancer chemoprevention. Int J Nanomed. 2015;10:475-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khyade VB. Influence of Sibinin on DMBA induced hepatotoxicity and free radical damage in Norwegian rat, Rattus norvegicus. IJIRSET. 2016;3(12):22-38. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ozdemir I, Selamoglu Z, Ates B, Gok Y, Yilmaz I. Modulation of DMBA-induced biochemical changes by organoselenium compounds in blood of rats. Indian Journal of Biochemistry & Biophysics. 2007;44:257-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bedi PS, Priyanka S. Effects of garlic against 7-12, Dimethyl benzanthracene induced toxicity in Wistar albino rats. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2012;5(4):170-173. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arora R, Bhushan S, Kumar R, et al. Hepatic dysfunction induced by 7, 12-Dimethylbenz(o)anthracene and its obviation with Erucin using enzymatic and histological changes as indicators. PLoS ONE 2014;9(11):e112614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salem A, Noaman E, Kandil E, et al. Crystal structure and chemotherapeutic efficacy of the novel compound, gallium tetrachloride betaine, against breast cancer using nanotechnology. Tumor Biol . 2016; 37(8): 11025-1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moustafa EM, Mohamed MA, Thabet NM. Gallium nanoparticle- mediated reduction of brain specific serine protease-4 in an experimental metastatic cancer model. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2017;18(4):895-903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Batcioglu K, Uyumlu AB, Satilmis B, et al. Oxidative stress in the in vivo DMBA rat model of breast cancer: suppression by a voltage-gated sodium channel inhibitor (RS100642). Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2012;111:137-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moselhy SS, Al mslmani MAB. Chemopreventive effect of lycopene alone or with melatonin against the genesis of oxidative stress and mammary tumors induced by 7, 12dimethyl (a) benzanthracene in Sprague dawely female rats. Mol Cell Biochem. 2008;319(1-2):175-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hamdy SM, Latif AK, Drees EA, Soliman SM. Prevention of rat breast cancer by genistin and selenium. Toxicol Ind Health 2012. Sep;28(8):746-757. doi: 10.1177/0748233711422732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Selamoglu TZ, Yilmaz I, Ozdemir I, et al. Role of synthesized organoselenium compounds on protection of rat erythrocytes from DMBA- induced oxidative stress. Biol Trace Elem Res 2009;128:167-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ozkaya A, $elik S, Yuce A, et al. The effects of ellagic acid on some biochemical parameters in the liver of rats against oxidative stress induced by aluminum. KAFKAS UNIV VET. FAK 2010;16(2):263-268. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Soujanya J, Silambujanaki P, Krishna VL. Anticancer efficacy of holoptelea integrifolia, planch. against 7,12-dimethylbenz(a) anthracene induced breast carcinoma in experimental rats. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci 2011;3:103-106. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vattem DA, Shetty K. Biological functionality of ellagic acid: a review. J Food Biochem 2005(29):234-266. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bériault R, Hamel R, Chenier D, et al. The over expression of NADPH- producing enzymes counters the oxidative stress evoked by gallium, an iron mimetic. Biometals 2007;20:165-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chitambar CR. Gallium and its competing roles with iron in biological systems. Biochim Biophys Acta 2016;1863:2044-2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Elliott RL, Head JE, McCoy JL. Relationship of serum and tumor levels of iron and iron-binding proteins to lymphocyte immunity against tumor antigen in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1994;30:305-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Skrajnowska D, Bobrowska-Korczak B, Tokarz A, et al. Copper and resveratrol attenuates serum catalase, glutathione peroxidase, and element values in rats with DMBA-induced mammary carcinogenesis. Biol Trace Elem Res 2013;156(1-3):271-278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schwarz EC, Qu B, Hoth M. Calcium, cancer and killing: the role of calcium in killing cancer cells by cytotoxic T lymphocytes and natural killer cells. Biochlm Biophys Acta 2013;1833(7):1603-1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Burchiel SW, Davis DA, Ray SD, Barton SL. DMBA induces programmed cell death (apoptosis) in the A20.1 murine B celllymphoma. Fundamental and applled tOXlCOlogy o cfa/Journal Of the. Society of Toxicology 1993;21(1):120-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cao Y, Wang J, Henry-Tillman R, Klimberg VS. Effect of 7, 12- dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA) on gut glutathione metabolism. J Surg Res 2001;100(1):135-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Qu B, Al-Ansary D, Kummerow C, Hoth M, Schwarz EC. ORAI- mediated calcium influx in T cell proliferation, apoptosis and tolerance. Cell Calcium 2011;50:261-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Devarajan E, Sahin AA, Chen JS, et al. Down-regulation of caspase 3 in breast cancer: a possible mechanism for chemoresistance. Oncogene 2002(21):8843-8851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cagnol S, Mansour A, Van Obberghen-Schilling E, et al. Raf-1 activation prevents caspase 9 processing downstream of apoptosome formation. J Signal Transduct 2011;2011:1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jiinicke RU, Sprengart ML, Wati MR. et. a1Caspase-3 is required for DNA fragmentation and morphological changes associated with apoptosis. J Biol Chem 1998;273(16):9357-9360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.O’Donovan N, Crown J, Stunell H, et al. Caspase-3 in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2003;9(2):738-742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chitambar CR. Gallium-containing anticancer compounds. Future Med Chem 2012;4(10):1257-1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chitambar CR, Wereley JP, Matsuyama S. Gallium-induced cell death in lymphoma: role of transferrin Receptor cycling, involvement of Bax and the mitochondria, and effects of proteasome inhibition. Mol Cancer Ther 2006;5:2834-2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abba MC, Zhong Y, Lee J, et al. DMBA induced mouse mammary tumors display high incidence of activating Pik3ca H1047 and loss of function Pten mutations. Oncotarget 2016;7(39):64289-64299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang N, Wang ZY, Mo SL, et al. Ellagic acid, a phenolic compound, exerts anti-angiogenesis effects viaVEGFR-2 signaling pathway in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012;134:943-955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Eskandari E, Heidarian E, Amini SA, et al. Evaluating the effects of Ellagic acid on pSTAT3, pAKT, and pERK1/2 signaling pathways in prostate cancer PC3 cells. J Cancer Res Ther 2016;12:1266-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Feng M, Feng C, Yu Z, et al. Histopathological alterations during breast carcinogenesis in a rat model induced by 7,12-Dimethylbenz (a) anthracene and estrogen-progestogen combinations. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015;8(1):346-357. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-dos-10.1177_15593258211068998 for Antitumor and Antibacterial Efficacy of Gallium Nanoparticles Coated by Ellagic Acid by Sawsan M El-sonbaty, Fatma SM Moawed, Eman I Kandil, and Amira M in Dose-Response