Diabetes Mellitus (DM) likely enhances neurodegeneration via vascular1,2 and non-vascular3,4 mechanisms, but this has not been well-studied in Huntington’s Disease (HD). Therefore, we leveraged the Enroll-HD platform to determine if patients with pre-manifest HD and DM had an increased risk of receiving a motor diagnosis compared to non-diabetic patients with HD.

We included pre-motor-manifest participants with a CAG repeat length of 36–59. A concomitant diagnosis of DM was based on self-reported comorbidity and pharmacotherapy data. We performed a Cox Proportional Hazard Regression survival analysis to compare the risk of receiving a motor diagnosis of HD between the DM and non-DM groups, defined as a diagnostic confidence level rating of four on the Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale during an Enroll-HD visit. DM was treated as a time-dependent risk factor, as previously described.5 We controlled for historical tobacco use, a concomitant diagnosis of hypertension, baseline body mass index, CAG repeat length, baseline age, baseline CAG-Age Product Score6, sex, and region.

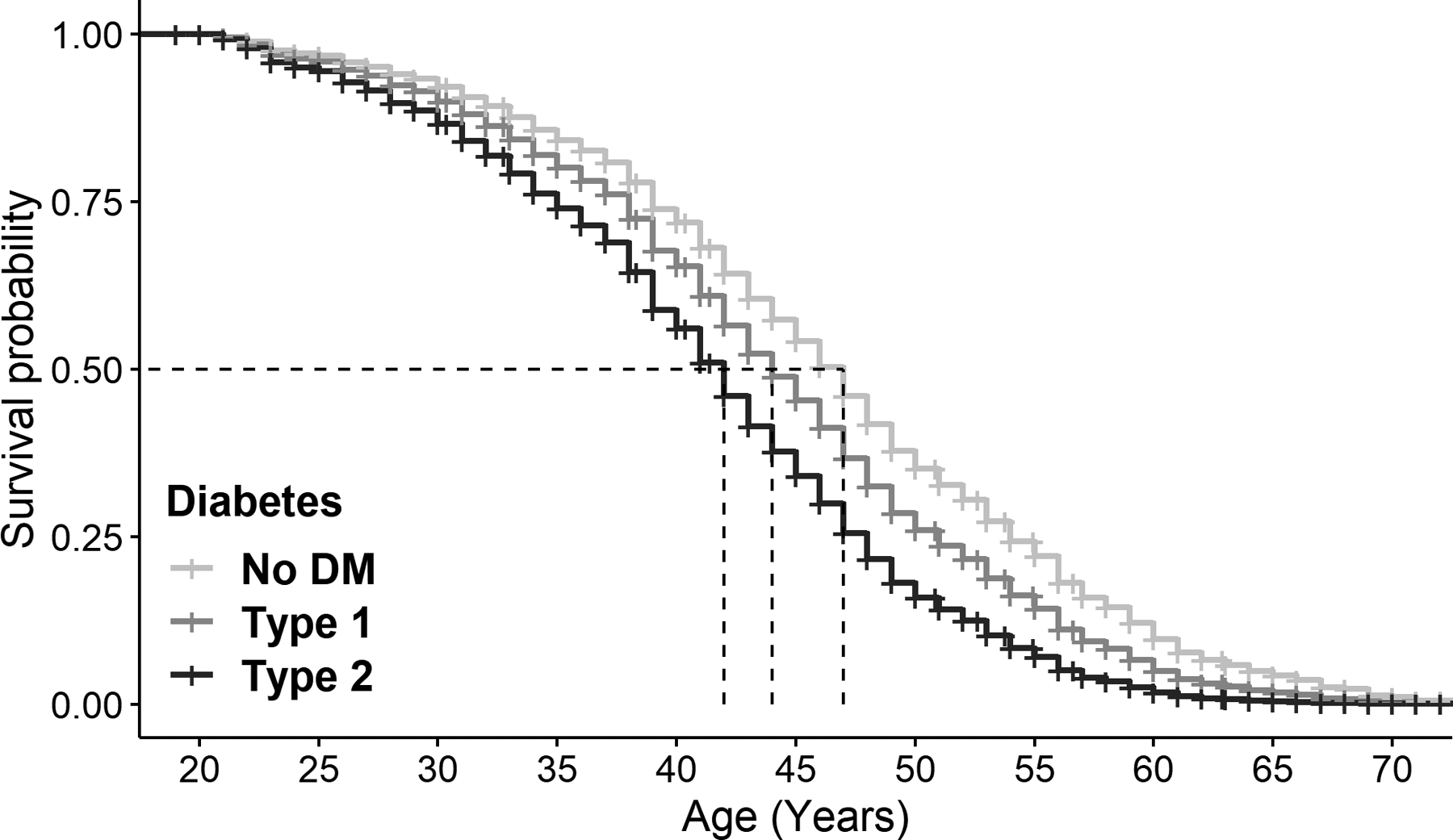

There were 2709 participants without DM and 58 participants with a concomitant diagnosis of DM. Of those 58 participants, 42 had type 2 DM (DM2) and 16 had type 1 DM (DM1). Participants with DM had a significantly increased annualized hazard of receiving a motor diagnosis of HD compared to participants without DM (Hazard Ratio = 1.63, 95% Confidence Interval [1.03 – 2.59], p=0.037). We then repeated this analysis but split the DM group into those with DM1 and those with DM2 and compared them to the non-DM group. We found that those with DM1 did not have a significantly increased annualized hazard of receiving a motor diagnosis of HD (Hazard Ratio = 1.29, 95% Confidence Interval [0.48 – 3.47], p=0.615), but participants with DM2 had a higher annualized risk (Hazard Ratio = 1.76, 95% Confidence Interval [1.05 – 2.94], p=0.033; Figure 1).

Figure 1: Probability of Receiving a Motor Diagnosis Based on Concomitant Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus Type 1 or Diabetes Mellitus Type 2.

Participants with the gene-expansion that causes HD who had a concomitant diagnosis of diabetes mellitus type 2 seemed to have a significantly higher annualized hazard of receiving a motor diagnosis compared to similar participants who did not have a concomitant diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. HD participants with a concomitant diagnosis of diabetes mellitus type 1 had a higher annualized risk of receiving a motor diagnosis compared to those without this diagnosis, but the difference was not statistically significant.

DM: Diabetes Mellitus

HD: Huntington Disease

A limitation of this study is the inability to accurately assess the impact of anti-diabetic medications on these results. Oral hypoglycemics and insulin products have been hypothesized to slow neurodegeneration.7 In this study, more than 95% of participants with DM2 were using an anti-diabetic medication making comparisons between medication users and non-users impractical. If anti-diabetic medications do slow neurodegeneration, participants with DM2 still had earlier onset of their HD despite near-uniform use of anti-diabetic medications indicating that DM2 is an important modifiable risk factor for HD. A further limitation is the lack of clinical data, such as hemoglobin A1c, to determine if better glycemic control is associated with differences in HD-related outcomes. Lastly, participants with DM may see their providers more frequently, which could result in detection bias within this group.

This study provides preliminary evidence that DM2 may be associated with an increased risk of receiving an earlier motor diagnosis of HD. Further prospective studies are necessary to expand on these results. However, because DM2 is a modifiable risk factor that can be prevented with early interventions, these findings may have significant clinical implications. Specifically, placing a larger focus on cardiovascular outcomes in HD may help slow the progression of HD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Enroll-HD is a longitudinal observational study for Huntington’s disease families intended to accelerate progress towards therapeutics; it is sponsored by CHDI Foundation, a nonprofit biomedical research organization exclusively dedicated to developing therapeutics for HD. Enroll-HD would not be possible without the vital contribution of the research participants and their families.

Author Disclosures:

Ms. Ogilvie reports no disclosures.

Dr. Gonzalez-Alegre reports having received consulting fees from Spark Therapeutics, Eisai Therapeutics and NeuExcell Therapeutics, licensing fees from Spark Therapeutics via the University of Iowa, research funding from the NINDS, is the Principal Investigator of a clinical trial (NeuroSEQ) that is sponsored by Illumina, and receives research-related funds from CHDI and BioHaven for serving as site-investigator for sponsored clinical trials

Dr. Schultz is currently supported by a career-development grant through NCATS (KL2TR002536) and receives salary support and research funding from the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Disease Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ott A, Stolk RP, Hofman A, van Harskamp F, Grobbee DE, Breteler MM. Association of diabetes mellitus and dementia: the Rotterdam Study. Diabetologia. 1996;39(11):1392–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seaquist ER. The final frontier: how does diabetes affect the brain? Diabetes. 2010;59(1):4–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bello-Chavolla OY, Antonio-Villa NE, Vargas-Vazquez A, Avila-Funes JA, Aguilar-Salinas CA. Pathophysiological Mechanisms Linking Type 2 Diabetes and Dementia: Review of Evidence from Clinical, Translational and Epidemiological Research. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2019;15(6):456–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farhadi A, Vosough M, Zhang JS, Tahamtani Y, Shahpasand K. A Possible Neurodegeneration Mechanism Triggered by Diabetes. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2019;30(10):692–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schultz JL, Harshman LA, Langbehn DR, Nopoulos PC. Hypertension Is Associated with an Earlier Age of Onset of Huntington’s Disease. Mov Disord. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Long JD, Mills JA, et al. Indexing disease progression at study entry with individuals at-risk for Huntington disease. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2011;156B(7):751–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bendlin BB. Antidiabetic therapies and Alzheimer disease. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2019;21(1):83–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]