Abstract

Objective:

To examine Medicaid expansion (ME) effects on health insurance coverage (HIC) and cost barriers to medical care among people with asthma.

Method:

We analyzed 2012–2013 and 2015–2016 data from low-income adults with current asthma aged 18–64 years in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Asthma Call-Back Survey (state-level telephone survey). We calculated weighted percentages and 95% confidence intervals from ME and non-ME jurisdictions (according to 2014 ME status). Outcomes were HIC and cost barriers to buying asthma medication (MED), seeing a health care provider for asthma (HCP), or any asthma care (AAC). Using SUDAAN, we performed survey-weighted difference-in-differences analyses, adjusting for demographics. Subgroup analyses were stratified by demographics.

Results:

Our study population included 6445 participants from 25 states plus Puerto Rico. In 2015–2016 compared to 2012–2013, HIC was more common in ME jurisdictions (P<0.001) but unchanged in non-ME jurisdictions. Adjusted difference-in-differences analyses showed ME was associated with a statistically significant 13.36 percentage-point increase in HIC (standard error = 0.053). Cost barriers to MED, HCP, and AAC did not change significantly for either group in descriptive and difference-in-differences analyses. In subgroup analyses, we noted variation in outcomes by demographics and 2014 ME status.

Conclusions:

We found ME significantly affected HIC among low-income adults with asthma, but not cost barriers to asthma-related health care. Strategies to reduce cost barriers to asthma care could further improve health care access among low-income adults with asthma in ME jurisdictions.

Keywords: asthma, Medicaid, Medicaid expansion, health insurance, cost, disparities, race, ethnicity, sex, age

INTRODUCTION

The Affordable Care Act expanded eligibility criteria for Medicaid to include nonelderly citizens and permanent residents with incomes below 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL) in participating states (“Medicaid expansion”), effective on or after January 1, 2014.(1, 2) Subsequently, 26 states and the District of Columbia implemented Medicaid expansion (ME) in 2014.(2, 3)

Asthma affects over 19 million U.S. adults, resulting in >8.7 million asthma-related missed work days and >1 million hospitalizations and emergency department (ED) visits among adults each year.(4, 5) Many asthma-related hospitalizations, ED visits, and missed work days can be prevented with guidelines-based preventive care for asthma, including regularly scheduled visits with health care providers and (when indicated) asthma medications intended to prevent asthma symptoms.(6)

The impact of ME has been investigated in the overall population as well as in people with some specific health conditions, such as congestive heart failure (CHF), kidney disease, diabetes, and depression.(7–10) Varied relationships between ME, health care access, health care use, and health outcomes have been reported; for example, one study found ME was associated with increased health insurance coverage among patients admitted for CHF but in-hospital mortality did not change.(7, 10, 11) Also, some studies have suggested the impact of ME can differ by demographic characteristics including race/ethnicity and sex.(12–15) For instance, one report indicated Hispanic participants were least likely to benefit from gains in health insurance coverage and access to doctors after ME.(12)

Understanding of the impact of ME on people with respiratory conditions, including asthma, remains limited.(16, 17) One recent study involving data from seven states found an association between ME and a decline in mechanical ventilation rates for people with asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or CHF.(16) Data on study participants with asthma were not analyzed separately from those with COPD. These investigators did not detect significant relationships between ME and admissions to the intensive care unit or in-hospital mortality.(16) An earlier report showed COPD prevalence did not change after ME.(17) To date, asthma-specific data on the impact of ME have not been published.

Obtaining health insurance coverage through ME could reduce cost barriers to asthma-related health care and thereby reduce asthma morbidity and mortality.(18) We focused this investigation on examining the impact of ME on health insurance coverage and cost barriers to care among low-income adults with asthma. By first elucidating these relationships, we intended to lay a foundation for future study of how ME has affected asthma-related health care use and health outcomes.

Thus, the primary objective of our study was to investigate the impact of ME on health insurance coverage and cost barriers to care among low-income adults with asthma. Our secondary objective was to assess whether the impact of ME on health insurance coverage and cost barriers to care varied by demographic characteristics, within our study population.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Source

We used data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) Adult Asthma Call-Back Survey (ACBS). BRFSS is an ongoing, state-based, random-digit-dialing, cross-sectional telephone (land line and cell phone) survey of non-institutionalized U.S. adults aged ≥18 years; BRFSS is conducted in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and 3 U.S. territories.(19) Details about BRFSS’ disproportionate stratified sample design and sample weighting have been reported elsewhere.(19–21) ACBS is a follow-up telephone survey that some states administer to BRFSS participants who responded that they ever had asthma (i.e., they responded “yes” to the question, “have you ever been told by a doctor, nurse, or other health professional that you had asthma?”). Any state or territory can choose to apply for funds to implement the ACBS for a particular year, but not all do; for example, 28 jurisdictions collected ACBS data from adults during each of the 4 years included in our study period (i.e., 2012, 2013, 2015, and 2016).(22, 23) ACBS is conducted approximately two weeks after BRFSS. Response rates for BRFSS and ACBS in 2016 were 47.1% and 44.5%, respectively(24, 25); response rates were similar across the years of data included in this study. Jurisdiction-specific Institutional Review Board (IRB) requirements apply to each participating jurisdiction(22, 23); informed consent was obtained. Analyses of ACBS data are exempt from review by the IRB at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

We used four years of ACBS data, combining two 2 years of data for each period to obtain a sufficiently large sample to generate stable estimates (i.e., 2012–2013 and 2015–2016). Similar to prior publications on the impact of ME, we excluded 2014 data.(7) Also, we excluded 2014 data to avoid assuming that participants applied for or received Medicaid coverage as soon as ME could be implemented in January 2014.

To estimate the effect of ME, we defined the ME group as participants in jurisdictions that expanded Medicaid in 2014 (Table 1).(26–28) Our comparison group was participants in jurisdictions that did not expand Medicaid in 2014 (“non-ME”).

Table 1.

Definition of Medicaid Expansion and Non-Medicaid Expansion Groups: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Asthma Call-Back Survey, 2012–2013 and 2015–2016

| Medicaid Expansion (ME) Group (15 jurisdictions) |

Non-Medicaid Expansion (Non-ME) Group (11 jurisdictions) |

|---|---|

| • Connecticut | • Florida |

| • Hawaii | • Georgia |

| • Iowa | • Kansas |

| • Massachusetts | • Maine |

| • Michigan | • Mississippi |

| • Nevada | • Missouri |

| • New Hampshire | • Montana |

| • New Jersey | • Nebraska |

| • New Mexico | • Texas |

| • New York | • Utah |

| • Ohio | • Wisconsin |

| • Oregon | |

| • Puerto Rico | |

| • Rhode Island | |

| • Vermont |

Indiana and Pennsylvania were excluded from this analysis because these states expanded Medicaid in 2015. The 23 states not listed in this table were excluded because ACBS data were not available from these states for each of the years included in the study period.

Study Population

Our study population was low-income adult ACBS participants aged 18–64 years with current asthma from jurisdictions (U.S. states or territories) for which ACBS data were available for every year included in our study period (i.e., 2012, 2013, 2015, and 2016). From the 28 jurisdictions that had ACBS data available for these four years, we excluded two states (Indiana and Pennsylvania) because these states implemented ME in 2015(3) (in our study, 2015 was defined as part of our post-ME period). Of the remaining 26 jurisdictions, 15 jurisdictions were included in the ME group (14 states plus Puerto Rico) and 11 jurisdictions/states were represented in the non-ME group. More detail on these 26 jurisdictions is presented in Table 1. We defined low-income as reported annual household income below 138% of the 2016 FPL.(29) Because the survey collected annual household income in categories, we used the midpoints of these categories to calculate household income as a percentage of FPL while accounting for family size, similar to prior analyses.(30) We excluded participants with missing income data (11.3% of the original, entire dataset that contained our final study population as well as respondents who were excluded from our study population), as well as adults aged ≥65 years because of their eligibility for Medicare.(31) To meet our definition of current asthma, participants had to respond “yes” to both of the following questions: “Has a doctor, nurse, or other health professional ever told you that you had asthma?” and “Do you still have asthma?”

Measures

We examined four outcomes: any health insurance coverage (at the time of the survey interview), could not buy asthma medication because of cost during the past 12 months, could not see health care provider for asthma because of cost during the past 12 months, and any cost barrier to asthma care during the past 12 months. For “could not see health care provider for asthma because of cost during the past 12 months”, we classified participants as having this outcome if they answered “yes” to either of these two questionnaire items: “Was there a time in the past 12 months when you needed to see your primary care doctor for your asthma but could not because of the cost?” and “Was there a time in the past 12 months when you were referred to a specialist for asthma care but could not go because of the cost?” We classified participants as having any cost barrier to asthma care during the past 12 months if they reported they could not buy asthma medication, see their primary care doctor for asthma, or go to a specialist for asthma care because of cost in the past 12 months.

Statistical Analysis

We used SAS 9.4-callable SUDAAN (version 11.0.1) to account for the complex survey design of the ACBS. Detailed information on ACBS survey design and analytic methods is publicly available.(22) We calculated weighted percentages and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each variable and each period (i.e., 2012–2013 and 2015–2016), by ME status. According to standard protocols(22, 32), our analyses used ACBS final weights to adjust for loss of sample between the BRFSS interview and the ACBS interview, as well as to compensate for nonresponse during the BRFSS and ACBS interviews. We used these methods to generate data representative of the 26 jurisdictions (25 states and Puerto Rico) included in our analysis. Additional information on weight calculations and response rates is located online and in prior publications.(22, 33–35) Results for which the relative standard error was >0.3 were suppressed, per standard protocol.(22) Within each group (ME and non-ME), we used t-tests (α=0.05) to compare weighted percentages and 95% CIs from 2012–2013 to those from 2015–2016.

Furthermore, we used a quasiexperimental difference-in-differences design to estimate the effect of ME on each of the four outcomes, similar to prior research on ME effects.(8, 9, 12, 17, 27, 30, 36–43) This method contrasts the changes from before to after ME in states that implemented ME and with the changes over the same time period in states that did not implement ME.(8, 9, 17, 30, 36–38) Our linear model was specified as follows:

Outcomeist are binary indicators for responding “Yes” to the outcome of interest (e.g., health insurance coverage or could not buy asthma medication because of cost during the past 12 months) for individual i in state s in year t. Expands is a binary indicator for the 15 ME jurisdictions (14 states plus Puerto Rico) versus the 11 non-ME jurisdictions in our dataset. Yeart is a binary indicator for survey respondents in 2015–2016 versus 2012–2013. Xist is a vector of individual-level characteristics including race/ethnicity, sex, and age category; because we used annual household income to define our study population, we did not include other markers of socioeconomic status in this model. States is the fixed effect for state that captures time-invariant differences between states. β1 is the effect of ME. Identifying this effect assumes that in the absence of ME, the outcome of interest would have changed similarly from 2012–2013 to 2015–2016 in both ME and non-ME jurisdictions, after adjusting for covariates. In our estimates, we adjusted for race/ethnicity, sex, and age category. We report modeling results in percentage-point changes with standard errors (SEs). For all analyses, we excluded observations with missing outcome data. For adjusted analyses, we also excluded observations with missing covariate data.

Because of differences in asthma burden, covered Medicaid benefits, and health care access in Puerto Rico compared to states(44–46), we conducted a sensitivity analysis that excluded participants from Puerto Rico. Also, we conducted subgroup analyses by race/ethnicity, sex, and age category (including an age category for participants aged 18–25 years, who could have been affected by another ACA provision that allowed young adults aged less than 26 years to remain on their parents’ private health insurance plans).

RESULTS

Study Population Characteristics

Our results were based on 6445 survey responses from unique individuals (3346 individuals from 2012–2013 plus 3099 individuals from 2015–2016), representative of approximately 7.0 million low-income adults with current asthma aged 18–64 years in 26 jurisdictions (25 states plus Puerto Rico). Most respondents reported white, non-Hispanic race/ethnicity in both the ME and non-ME groups (Table 2). The percentage of black, non-Hispanic participants was similar in both groups. In contrast, the ME group had a higher percentage of Hispanic participants. COPD appeared more common in the non-ME group, in both 2012–2013 and 2015–2016.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Low-Incomea Adults Aged 18–64 Years With Current Asthma, by 2014 Medicaid Expansion Status: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Asthma Call-Back Survey, 2012–2013

| 2012–2013 | 2015–2016 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | ME Groupb Unweighted n = 1797d (Weighted n = 1 968 161) |

Non-ME Groupc Unweighted n = 1549d (Weighted n = 1 783 699) |

ME Groupb Unweighted n = 1704d (Weighted n = 1 836 183) |

Non-ME Groupc Unweighted n = 1395d (Weighted n = 1 377 922) |

| Weighted % (95% CI) | Weighted % (95% CI) | Weighted % (95% CI) | Weighted % (95% CI) | |

| Male sex | 31.8 (26.1–38.0) | 27.4 (21.6–34.1) | 34.0 (29.4–39.0) | 32.6 (26.4–39.5) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 58.4 (52.3–64.2) | 63.5 (56.4–70.1) | 51.2 (46.3–56.1) | 60.8 (54.0–67.2) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 16.8 (11.8–23.3) | 19.8 (15.0–25.8) | 14.0 (11.0–17.6) | 13.7 (10.0–18.5) |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 5.6 (4.1–7.5) | 3.7 (2.3–6.0) | 11.3 (8.1–15.4) | 7.7 (4.6–12.6) |

| Hispanic | 19.3 (15.6–23.6) | 12.9 (8.5–19.2) | 23.5 (20.0–27.9) | 17.8 (12.8–24.2) |

| Age in years | ||||

| 18–25 | 30.3 (23.9–37.5) | 22.2 (16.2–29.7) | 26.0 (21.4–31.3) | 27.3 (20.9–34.7) |

| 26–44 | 34.9 (29.5–40.6) | 40.3 (33.2–47.8) | 35.9 (31.2–40.9) | 32.2 (26.5–38.5) |

| 45–64 | 34.8 (30.2–39.9) | 37.5 (31.5–44.1) | 38.1 (33.8–42.6) | 40.5 (34.7–46.6) |

| COPD | 35.6 (30.74–40.8) | 43.0 (36.0–50.2) | 33.4 (29.3–37.8) | 41.8 (35.5–48.4) |

| Current smoker | 34.1 (29.0–39.6) | 35.4 (28.7–42.6) | 30.9 (26.6–35.5) | 30.2 (24.7–36.4) |

CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ME, Medicaid expansion.

Low-income was defined as below 138% of the federal poverty level.

Puerto Rico and the following 14 states: CT, HI, IA, MA, MI, NH, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OH, OR, RI, VT.

FL, GA, KS, ME, MS, MO, MT, NE, TX, UT, WI. Indiana and Pennsylvania were excluded from this analysis because these states expanded Medicaid in 2015. The 23 states remaining not represented in this table were excluded because ACBS data were not available from these states for each of the years included in the study period.

Total sample size (N) = 6445, which includes both 2012–2013 and 2015–2016 data.

Ever told by a doctor or other health professional that he or she had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), emphysema, or chronic bronchitis.

Results from Descriptive Analyses

In the ME group, the prevalence of health insurance coverage was higher in 2015–2016 than in 2012–2013 (92.3% [95%CI, 89.2–94.5] vs. 79.8% [95%CI, 74.6–84.1], P<0.001; Table 3). Prevalence of health insurance coverage did not change significantly in the non-ME group. Reports of inability to buy asthma medication or see a health care provider for asthma because of cost were slightly decreased in the ME group in 2015–2016 compared to 2012–2013, but these differences were not statistically significant; we observed a similar pattern for any cost barrier to asthma care. In the non-ME group, inability to buy asthma medication or see a health care provider for asthma because of cost were slightly more prevalent in 2015–2016 than 2012–2013 but these differences were not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Weighted Percentages of Health Insurance Coverage and Cost Barriers to Care Among Low-Incomea Adults Aged 18–64 Years With Current Asthma, by 2014 Medicaid Expansion Status: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Asthma Call-Back Survey, 2012–2013 and 2015–2016

| ME Groupb | Non-ME Groupc | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | 2012–2013 n; Weighted % (95% CI) |

2015–2016 n; Weighted % (95% CI) |

P valued | 2012–2013 n; Weighted % (95% CI) |

2015–2016 n; Weighted % (95% CI) |

P valued |

| Health insurance coveragee | 1788; 79.8 (74.6–84.1) | 1696; 92.3 (89.2–94.5) | <0.001 | 1543; 70.1 (63.1–76.3) | 1383; 69.9 (63.0–75.9) | 0.96 |

| Could not buy asthma medication because of costf | 1795; 25.8 (20.78–31.6) | 1699; 21.7 (17.6–26.4) | 0.25 | 1544; 32.4 (26.1–39.4) | 1385; 36.4 (29.9–43.3) | 0.42 |

| Could not see health care provider for asthma because of costf,g | 1795; 22.1 (17.1–28.0) | 1702; 17.5 (13.5–22.4) | 0.20 | 1548; 29.3 (23.3–36.0) | 1387; 32.9 (26.6–39.9) | 0.44 |

| Any cost barrier to asthma careh | 1797; 30.6 (25.3–36.4) | 1702; 27.3 (22.9–32.2) | 0.37 | 1549; 38.7 (32.1–45.7) | 1388; 40.9 (34.4–47.7) | 0.66 |

CI, confidence interval; ME, Medicaid expansion.

Low-income was defined as below 138% of the federal poverty level.

Puerto Rico and the following 14 states: CT, HI, IA, MA, MI, NH, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OH, OR, RI, VT.

FL, GA, KS, ME, MS, MO, MT, NE, TX, UT, WI. Indiana and Pennsylvania were excluded from this analysis because these states expanded Medicaid in 2015. The 23 remaining states not represented in this table were excluded because ACBS data were not available from these states for each of the years included in the study period.

Comparison between 2012–2013 and 2015–2016 data. Boldface indicates statistical significance (P < .05).

Reported any kind of health care coverage, including health insurance, prepaid plans such as HMOs, or government plans such as Medicare or Medicaid.

During the past 12 months.

Combination of 2 questionnaire items (“Was there a time in the past 12 months when you needed to see your primary care doctor for your asthma but could not because of cost?” and “Was there a time in the past 12 months when you were referred to a specialist for asthma care but could not go because of the cost?”). A cost barrier to asthma-related visit with a health care provider was defined as present if the respondent said “yes” to either questionnaire item.

Combination of “Could not buy asthma medication because of cost” and “Could not see health care provider for asthma because of cost.” Any cost barrier was defined as present if either of these variables was associated with a positive response.

Results from Difference-in-Differences Analyses

In our adjusted difference-in-differences analyses (Table 4), ME was associated with a statistically significant 13.36 percentage-point increase in health insurance coverage (SE=0.053). Also, ME was associated with a 9.53 percentage-point decrease in reported inability to buy asthma medication because of cost (SE=0.056), a 7.67 percentage-point decrease in reported inability to see a health care provider for asthma because of cost (SE=0.055), and a 6.62 percentage-point decrease in any cost barrier to asthma care (SE=0.058); confidence intervals for these cost barrier-related difference-in-differences analyses (unadjusted [Table E1] and adjusted) included the null. We found similar results in a sensitivity analysis that excluded participants from Puerto Rico (Table E2).

Table 4.

Percentage-Point Changes in Health Insurance Coverage and Cost Barriers to Care After Medicaid Expansion in 2014, Among Low-Incomea Adults Aged 18–64 Years With Current Asthma (Difference-in-Differences Analyses): Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Asthma Call-Back Survey, 2012–2013 and 2015–2016

| Difference-in-Differences Estimate (Adjusted)b | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | nc | Percentage-Point Change | Standard Error |

| Health insurance coveraged | 6315 | 13.36e | 0.053 |

| Could not buy asthma medication because of costf | 6337 | −9.53 | 0.056 |

| Could not see health care provider for asthma because of costf,g | 6328 | −7.67 | 0.055 |

| Any cost barrier to asthma careh | 6441 | −6.62 | 0.058 |

Low-income was defined as below 138% of the federal poverty level.

Adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity. These results estimate the change in likelihood of health insurance coverage or cost barriers to care in 2015–2016 versus 2012–2013 as a result of the Medicaid expansion, obtained from difference-in-differences analyses. These estimates are the appropriate coefficients from the regression model, multiplied by 100. The standard error represents the standard error of each coefficient, not multiplied by 100.

Unweighted (n). Total unweighted sample size (N) = 6445. Observations with missing data were excluded from analyses.

Reported any kind of health care coverage, including health insurance, prepaid plans such as HMOs, or government plans such as Medicare or Medicaid.

Significant at P < 0.05.

During the past 12 months.

Combination of 2 questionnaire items (“Was there a time in the past 12 months when you needed to see your primary care doctor for your asthma but could not because of cost?” and “Was there a time in the past 12 months when you were referred to a specialist for asthma care but could not go because of the cost?”). A cost barrier to asthma-related visit with a health care provider was defined as present if the respondent said “yes” to either questionnaire item.

Combination of “Could not buy asthma medication because of cost” and “Could not see health care provider for asthma because of cost.” Any cost barrier was defined as present if either of these variables was associated with a positive response.

Results from Subgroup Analyses

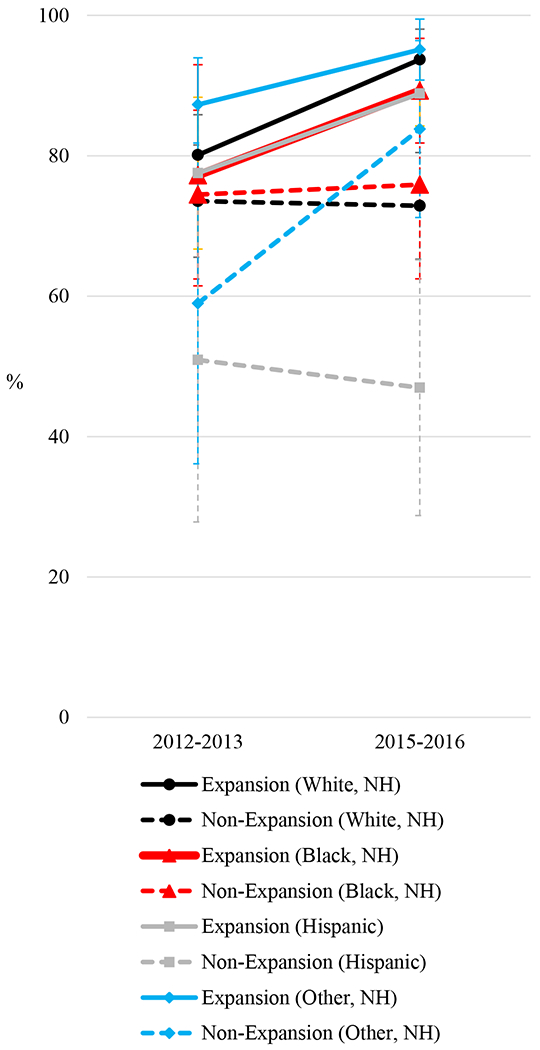

In subgroup analyses, we noted variation by race/ethnicity and 2014 ME status. In the ME group, prevalence of health insurance coverage was higher in 2015–2016 than 2012–2013 for all racial/ethnic categories (Figure 1 and Table E3); we did not see this pattern in the non-ME group. Notably, in the non-ME group, Hispanic participants had the lowest prevalence of health insurance coverage in both 2012–2013 (50.9% [95%CI, 29.2–72.3]) and 2015–2016 (47.0% [95%CI, 29.9–64.8]). Regarding inability to buy asthma medication or see a health care provider for asthma because of cost, we found no statistically significant differences in our analyses stratified by race/ethnicity (Tables E4 and E5). We did observe that Hispanic participants in the non-ME group most frequently indicated they could not see a health care provider for asthma because of cost in both 2012–2013 (53.6% [95%CI, 32.8–73.2]) and 2015–2016 (55.4% [95%CI, 37.7–71.9]).

Figure 1.

Health Insurance Coverage Among Low-Income Adults Aged 18–64 Years With Current Asthma, by Race/Ethnicity and 2014 Medicaid Expansion Status: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Asthma Call-Back Survey, 2012–2013 and 2015–2016

NH, non-Hispanic.

In subgroup analyses by sex, we found health insurance coverage was higher in 2015–2016 than in 2012–2013 among both males and females in the ME group (P=0.07 for males and P<0.001 for females; Table E6). We did not find statistically significant changes in cost barriers to buying asthma medication or seeing a health care provider for asthma in analyses stratified by sex (Tables E7–E8). However, among females in the ME group, we noticed nonsignificant decreases in 2015–2016 (compared to 2012–2013) in the inability to buy asthma medication because of cost (28.1% [95%CI, 21.8–35.3] vs. 21.9% [95%CI, 17.3–27.2], P=0.14) and inability to see a health care provider for asthma because of cost (25.2% [95%CI, 18.9–32.7] vs. 16.5% [95%CI, 12.2–22.1], P=0.05); we did not see a similar pattern among males in the ME group. In the non-ME group, we observed nonsignificant decreases in cost barriers to buying asthma medication or seeing a health care provider for asthma in 2015–2016 compared to 2012–2013 among males but not females.

In subgroup analyses by age category, we found the prevalence of health insurance coverage was significantly higher for all age categories in the ME group in 2015–2016 compared to 2012–2013 (Table E9). In the non-ME group, we found a nonsignificant decrease in prevalence of health insurance coverage among participants aged 18–25 years (82.2% [95%CI, 69.9–90.3] vs. 64.7% [95%CI, 47.8–78.6], P=0.07) that we did not observe among respondents in the two, older age categories. We did not see significant differences in cost barriers to buying asthma medication or seeing a health care provider for asthma in subgroup analyses by age category (Tables E10–E11), but we noted a nonsignificant increase in inability to see a health care provider for asthma because of cost among respondents aged 18–25 years in the non-ME group (22.9% [95%CI, 12.8–37.5] vs. 35.3% [95%CI, 21.1–52.5], P=0.23).

DISCUSSION

In this study of low-income adults with current asthma aged 18–64 years in 25 states and Puerto Rico, we found that ME was significantly associated with increased prevalence of health insurance coverage, but not significantly associated with cost barriers to buying asthma medication or seeing a health care provider for asthma. In subgroup analyses, we found outcomes varied by 2014 ME status and selected demographics.

To our knowledge, this analysis is the first investigation on the impact of ME on health insurance coverage and cost barriers to asthma-related health care among people with asthma. Strengths include our population-based study design and use of weighted statistical analyses to generate results representative of all 26 jurisdictions involved, as well as difference-in-differences analyses to further reduce the potential effect of unmeasured confounding.

Our findings extend prior research on the impact of ME. Knowledge is currently limited regarding the impact of ME on people with respiratory conditions; asthma-specific data are scarce.(16) Beyond the two studies we mentioned in the Introduction (a BRFSS analysis of COPD prevalence before and after ME(17) and a seven-state, hospital-based study that analyzed asthma and COPD data in aggregate(16)), other literature relevant to this topic includes several studies assessing the impact of ME on people who use tobacco.(10, 37, 38)

Although studies have generally reported positive effects of ME on affordability of care for health conditions other than asthma,(10) we observed weak-to-moderate, nonsignificant associations between ME and cost barriers to asthma-related care, despite finding ME and health insurance coverage to be significantly associated. One potential explanation is inadequate study power to detect weak-to-moderate differences between the ME and non-ME group. Another possibility is that required copayments by health insurance plans to access medical care can be a cost barrier.(46) Also, compared to therapies commonly used to treat heart disease, diabetes, and other chronic conditions, relatively few guideline-recommended, first-line treatments for asthma are available in generic formulations, which could contribute to copayment costs. For example, U.S. Food and Drug Administration approvals for the first generic fluticasone propionate/salmeterol inhalation powder and the first generic albuterol metered dose inhaler occurred in 2019 and 2020, respectively(47, 48) — after our study period ending in 2016.

Furthermore, our results support and advance previous investigations of how ME impact might differ by demographics. Prior work has examined how the prevalence of health insurance coverage after 2014 varied across age, sex, and racial/ethnic groups, as well as across specific groups within the Hispanic population (e.g., Mexican American vs. Central American).(10, 12–14) For example, as mentioned earlier, an analysis of 2013 and 2015 BRFSS data found Hispanic participants were least likely to benefit from gains in health insurance coverage and access to doctors after ME.(12) In our data, the low prevalence of health insurance coverage and high frequency of cost barriers to seeing a health care provider for asthma among Hispanic participants in non-ME jurisdictions highlight opportunities to improve health care access and reduce asthma disparities for this population.

Regarding how ME impact might differ by sex, multiple studies have focused on women’s health.(42, 49, 50) Our data suggest males did not experience reductions in cost barriers to asthma care to the same degree as females did in ME jurisdictions (although this decrease among females was not statistically significant). Some studies have reported sex differences in health care access after the Affordable Care Act(14, 15); our investigation adds asthma-specific data to this literature.

Our analysis had limitations. We obtained data from cross-sectional surveys; causality cannot be inferred. The survey did not specifically assess Medicaid coverage. Our study design did not exclude states that expanded Medicaid before 2014(51) or explore how other ACA provisions (e.g., allowing young adults aged less than 26 years to remain on their parents’ private health insurance plans) affected people with asthma.(34) All data were self-reported, including income data. Our definition of low-income was based on the 2016 FPL. Non-response bias was possible, so we conducted sampling and weighting procedures to reduce this possibility. Also, misclassification bias could have occurred; we reduced the likelihood of misclassification in our outcome measurements by excluding 2014 data, because many survey respondents in 2014 would have included 2013 health insurance coverage or cost barriers to care within the 12-month recall period of our outcome variables. Our sample size was not sufficient to perform difference-in-differences analyses by sex, race/ethnicity, or age category. We did not use multiple imputation to account for missing data; because approximately 1% of observations within our study population of 6445 respondents were excluded because of missing data, we do not expect our results would have differed substantially had we used multiple imputation.

CONCLUSION

In summary, we investigated the impact of ME among low-income adults with current asthma aged 18–64 years in 25 states and Puerto Rico, using descriptive and difference-in-differences analyses. We observed ME was significantly associated with increased prevalence of health insurance coverage, but not cost barriers to asthma medication or seeing a health care provider for asthma. These findings highlight opportunities to create and deliver tailored strategies to reduce cost barriers to care among low-income adults with asthma and existing health insurance coverage, as well as to further investigate the potential role of copayments on cost barriers to care among people with asthma who received health insurance coverage because of ME. Future study of the impact of ME on asthma exacerbations and other asthma-related health outcomes could increase understanding of how ME has affected people with asthma.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement:

Data are available at https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/acbs/index.htm

REFERENCES

- 1.Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. Medicaid Expansion to the New Adult Group. [Available from: https://www.macpac.gov/subtopic/medicaid-expansion/]. Accessed June 11, 2020.

- 2.Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid Expansion Spending and Enrollment in Context: An Early Look at CMS Claims Data for 2014. [Available from: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-expansion-spending-and-enrollment-in-context-an-early-look-at-cms-claims-data-for-2014/]. Accessed June 11, 2020.

- 3.Kaiser Family Foundation. Status of State Medicaid Expansion Decisions: Interactive Map. [Available from: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/status-of-state-medicaid-expansion-decisions-interactive-map/]. Accessed June 11, 2020.

- 4.Villarroel MA, Blackwell DL, Jen A. Tables of Summary Health Statistics for U.S. Adults: 2018 National Health Interview Survey National Center for Health Statistics. 2019. [Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/SHS/tables.htm]. Accessed June 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nurmagambetov T, Kuwahara R, Garbe P. The Economic Burden of Asthma in the United States, 2008–2013. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(3):348–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma—Full Report 2007. NIH Publication No. 07–4051. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen H, Sommers BD. Medicaid Expansion and Health: Assessing the Evidence After 5 Years. JAMA. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swaminathan S, Sommers BD, Thorsness R, Mehrotra R, Lee Y, Trivedi AN. Association of Medicaid Expansion With 1-Year Mortality Among Patients With End-Stage Renal Disease. JAMA. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fry CE, Sommers BD. Effect of Medicaid Expansion on Health Insurance Coverage and Access to Care Among Adults With Depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(11):1146–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaiser Family Foundation. The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review. [Available from: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review-august-2019/]. Accessed June 11, 2020.

- 11.Wadhera RK, Joynt Maddox KE, Fonarow GC, Zhao X, Heidenreich PA, DeVore AD, et al. Association of the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid Expansion With Care Quality and Outcomes for Low-Income Patients Hospitalized With Heart Failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(7):e004729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yue D, Rasmussen PW, Ponce NA. Racial/Ethnic Differential Effects of Medicaid Expansion on Health Care Access. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(5):3640–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Commonwealth Fund. Reducing Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Access to Care: Has the Affordable Care Act Made a Difference? [Available from: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2017/aug/reducing-racial-and-ethnic-disparities-access-care-has?redirect_source=/publications/issue-briefs/2017/aug/racial-ethnic-disparities-care]. Accessed June 11, 2020. [PubMed]

- 14.Wehby GL, Lyu W. The Impact of the ACA Medicaid Expansions on Health Insurance Coverage through 2015 and Coverage Disparities by Age, Race/Ethnicity, and Gender. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(2):1248–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manuel JI. Racial/Ethnic and Gender Disparities in Health Care Use and Access. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(3):1407–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Admon AJ, Sjoding MW, Lyon SM, Ayanian JZ, Iwashyna TJ, Cooke CR. Medicaid Expansion and Mechanical Ventilation in Asthma, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, and Heart Failure. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16(7):886–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tumin D, Jackson EJ Jr., Hayes D Jr. Medicaid expansion and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among low-income adults in the United States. Clin Respir J. 2018;12(4):1398–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most Recent National Asthma Data: Mortality. [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_national_asthma_data.htm]. Accessed June 9, 2020.

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Frequently Asked Questions. [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/about/brfss_faq.htm]. Accessed June 11, 2020.

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Overview: BRFSS 2016. [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2016/pdf/overview_2016.pdf]. Accessed June 11, 2020.

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/]. Accessed June 11, 2020.

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Asthma Call-back Survey History and Analysis Guidance. [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/acbs/2016/pdf/acbs_history_2016-final-version-2-508.pdf]. Accessed June 10, 2020.

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2011–2015 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Asthma Call-back Survey History and Analysis Guidance. [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/acbs/2015/pdf/acbs_history_2015-final-version-2-508.pdf]. Accessed June 10, 2020.

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. BRFSS 2016 Summary Data Quality Report. [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2016/pdf/2016-sdqr.pdf]. Accessed June 10, 2020.

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2016 BRFSS Asthma Call-back Survey Summary Data Quality Report. [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/acbs/2016/pdf/sdq_report_acbs_16-508.pdf]. Accessed June 10, 2020.

- 26.Wadhera RK, Bhatt DL, Wang TY, Lu D, Lucas J, Figueroa JF, et al. Association of State Medicaid Expansion With Quality of Care and Outcomes for Low-Income Patients Hospitalized With Acute Myocardial Infarction. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(2):120–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Griffith K, Evans L, Bor J. The Affordable Care Act Reduced Socioeconomic Disparities In Health Care Access. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okoro CA, Zhao G, Fox JB, Eke PI, Greenlund KJ, Town M. Surveillance for Health Care Access and Health Services Use, Adults Aged 18–64 Years - Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66(7):1–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.United States Census Bureau. Poverty Thresholds. [Available from: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-poverty-thresholds.html]. Accessed June 5, 2020.

- 30.Lyu W, Wehby GL. The Impacts of the ACA Medicaid Expansions on Cancer Screening Use by Primary Care Provider Supply. Med Care. 2019;57(3):202–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo H, Chen ZA, Xu L, Bell RA. Health Care Access and Receipt of Clinical Diabetes Preventive Care for Working-Age Adults With Diabetes in States With and Without Medicaid Expansion: Results from the 2013 and 2015 BRFSS. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The BRFSS Data User Guide. [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/data_documentation/pdf/UserguideJune2013.pdf]. Accessed June 10, 2020.

- 33.Hsu J, Chen J, Mirabelli MC. Asthma Morbidity, Comorbidities, and Modifiable Factors Among Older Adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(1):236–43 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsu J, Qin X, Mirabelli MC. Asthma-related impact of extending US parents’ health insurance coverage to young adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(3):1091–3 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. BRFSS Asthma Call-back Survey. [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/acbs/]. Accessed June 11, 2020.

- 36.Courtemanche C, Marton J, Ukert B, Yelowitz A, Zapata D. Effects of the Affordable Care Act on Health Care Access and Self-Assessed Health After 3 Years. Inquiry. 2018;55:46958018796361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown CC, Tilford JM, Bird TM. Improved Health and Insurance Status Among Cigarette Smokers After Medicaid Expansion, 2011–2016. Public Health Rep. 2018;133(3):294–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cotti C, Nesson E, Tefft N. Impacts of the ACA Medicaid expansion on health behaviors: Evidence from household panel data. Health Econ. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang D, Ritchey MR, Park C, Li J, Chapel J, Wang G. Association Between Medicaid Coverage and Income Status on Health Care Use and Costs Among Hypertensive Adults After Enactment of the Affordable Care Act. Am J Hypertens. 2019;32(10):1030–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gonzales S, Sommers BD. Intra-Ethnic Coverage Disparities among Latinos and the Effects of Health Reform. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(3):1373–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sommers BD, Maylone B, Blendon RJ, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Three-Year Impacts Of The Affordable Care Act: Improved Medical Care And Health Among Low-Income Adults. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(6):1119–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sabik LM, Tarazi WW, Hochhalter S, Dahman B, Bradley CJ. Medicaid Expansions and Cervical Cancer Screening for Low-Income Women. Health Serv Res. 2018;53 Suppl 1:2870–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karaca-Mandic P, Norton EC, Dowd B. Interaction terms in nonlinear models. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(1 Pt 1):255–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid in the Territories: Program Features, Challenges, and Changes. [Available from: https://www.kff.org/report-section/medicaid-in-the-territories-program-features-challenges-and-changes-issue-brief/]. Accessed June 10, 2020.

- 45.El Burai Felix S, Bailey CM, Zahran HS. Asthma prevalence among Hispanic adults in Puerto Rico and Hispanic adults of Puerto Rican descent in the United States - results from two national surveys. J Asthma. 2015;52(1):3–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pruitt K, Yu A, Kaplan BM, Hsu J, Collins P. Medicaid Coverage of Guidelines-Based Asthma Care Across 50 States, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, 2016–2017. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;15:E110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves First Generic Advair Diskus. [Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-generic-advair-diskus#:~:text=The%20U.S.%20Food%20and%20Drug%20Administration%20today%20approved,exacerbations%20in%20patients%20with%20chronic%20obstructive%20pulmonary%20]. Accessed July 17, 2020.

- 48.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves First Generic of a Commonly Used Albuterol Inhaler to Treat and Prevent Bronchospasm. [Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-generic-commonly-used-albuterol-inhaler-treat-and-prevent-bronchospasm]. Accessed July 17, 2020.

- 49.Johnston EM, Strahan AE, Joski P, Dunlop AL, Adams EK. Impacts of the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid Expansion on Women of Reproductive Age: Differences by Parental Status and State Policies. Womens Health Issues. 2018;28(2):122–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sabik LM, Tarazi WW, Bradley CJ. State Medicaid expansion decisions and disparities in women’s cancer screening. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(1):98–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaiser Family Foundation. States Getting a Jump Start on Health Reform’s Medicaid Expansion. [Available from: https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/states-getting-a-jump-start-on-health/]. Accessed March 30, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available at https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/acbs/index.htm