Abstract

Objective:

To compare interpretability of two intrapartum abdominal fetal heart rate monitoring strategies. We hypothesized that an external fetal electrocardiography monitoring system, a newer technology using wireless abdominal pads, would generate more interpretable fetal heart rate data compared to standard external Doppler fetal heart rate monitoring (standard external monitoring).

Study Design:

We conducted a randomized controlled trial at four Utah hospitals. Patients were enrolled at labor admission and randomized in blocks based on body mass index to fetal electrocardiography or standard external monitoring. Two reviewers, blinded to study allocation, reviewed each fetal heart rate tracing. The primary outcome was the percentage of interpretable minutes of fetal heart rate tracing. An interpretable minute was defined as >25% fetal heart rate data present and no more than 25% continuous missing fetal heart rate data or artifact present. Secondary outcomes included the percentage of interpretable minutes of fetal heart rate tracing obtained while on study device only, the number of device adjustments required intrapartum, clinical outcomes, and patient/provider device satisfaction. We determined that 100 patients per arm (200 total) would be needed to detect a 5% difference in interpretability with 95% power.

Results:

218 women were randomized, 108 to fetal electrocardiography and 110 to standard external monitoring. Device set up failure occurred more often in the fetal electrocardiography group (7.5% (8/107) versus 0% (0/109) for standard external monitoring). There were no differences in the percent of interpretable tracing between the two groups. However, fetal electrocardiography produced more interpretable fetal heart rate tracing in subjects with body mass index ≥30. When considering the percentage of interpretable minutes of fetal heart rate tracing while on study device only, fetal electrocardiography outperformed standard external monitoring for all subjects, regardless of maternal body mass index. Maternal demographics and clinical outcomes were similar between arms. In the fetal electrocardiography group, more device changes occurred compared to standard external monitoring (51% vs. 39%), but there were fewer nursing device adjustments (2.9 vs. 6.2 mean adjustments intrapartum, p<0.01). There were no differences in physician device satisfaction scores between groups, but fetal electrocardiography generated higher patient satisfaction scores.

Conclusion:

Fetal electrocardiography performed similarly to standard external monitoring when considering percentage of interpretable tracing generated in labor. Furthermore, patients reported overall greater satisfaction with fetal electrocardiography in labor. Fetal electrocardiography may be particularly useful in patients with body mass index ≥30.

Keywords: fetal electrocardiography, fetal electrocardiogram, fetal heart rate monitoring, intrapartum fetal monitoring, fetal ECG, labor monitoring, external monitoring

Introduction

Electronic fetal heart rate (FHR) monitoring in labor is a common intrapartum obstetric procedure1. Continuous FHR monitoring is used to identify fetuses at risk for intrapartum metabolic compromise and allow for intervention 2,3. The quality of the FHR signal is critical for appropriate interpretation of characteristics that identify a fetus at risk.

Electronic FHR monitoring devices commonly used in current obstetric practice have several limitations, in particular that the quality of the data obtained is dependent on fetal position, maternal position, and maternal body habitus. Continuous, high quality data are difficult to obtain in women with high body mass index (BMI). Studies have described the average percent of time during labor with Doppler ultrasound FHR signal loss to range from 10–40%4–7. The variation in signal loss is attributed to changes in maternal and fetal position, stage of labor, and improvement in FHR Doppler signal acquisition over time.

Internal fetal monitors (i.e. the fetal scalp electrode) may only be used when amniotic membranes are ruptured and the cervix is sufficiently dilated. These devices are contraindicated in the setting of certain maternal infections and fetal conditions (e.g. fetal bleeding diathesis2).

These device characteristics may limit utility of internal monitoring device use in certain patient populations. Similar problems are encountered during attempts to monitor the frequency, strength and duration of uterine contractions.

Newer devices such as fetal electrocardiography (ECG) and electromyography (EMG) are available that utilize technology to capture both the electrical activity of the fetal heart and uterine contractions8,9. These devices assess the fetal R-R interval utilizing wireless, adhesive pads (like ECG pads) in 4–5 locations on the maternal abdomen. This wireless method for FHR monitoring is not dependent upon maternal position, body habitus or fetal position; thus, the patient may theoretically move to any position without loss of signal10,11. An additional benefit to this type of device is the continuous maternal heart rate display simultaneous with FHR tracing, thus decreasing maternal and fetal heart rate confusion8,12. Uterine contraction electrical activity is recorded to determine contraction frequency and duration utilizing an external EMG13. These new monitors may require less nursing intervention, avoid invasive monitoring, and may allow for freedom of maternal movement and positioning, which may increase patient satisfaction with their labor experience. A recent, small qualitative study has suggested that the external fetal ECG may be an acceptable method for longer term fetal monitoring in the ambulatory setting14. Whether this translates to the labor unit is unknown.

The objective of this study was to compare the percentage of interpretable FHR tracing data generated by a wireless fetal ECG device (fECG) to standard external monitoring (SEM) approaches (i.e. external fetal Doppler ultrasound and tocometer). Our primary hypothesis was that use of fECG would produce more interpretable FHR data when compared with SEM in term, laboring, singleton pregnancies.

Materials and Methods Study setting and patients

We conducted a pragmatic, randomized controlled trial comparing two FHR monitoring strategies: fECG (the Monica Novii™ Wireless Patch System (GE Healthcare), an FDA approved and commercially available device) and conventional Doppler external FHR monitoring and tocometry (standard external monitoring or SEM). We compared the percentage of interpretable FHR generated from the time of randomization until delivery using both monitoring strategies at four Intermountain Healthcare hospitals in Utah, USA (Intermountain Medical Center, LDS Hospital, McKay Dee Hospital, Utah Valley Hospital).

Patients eligible for enrollment included pregnant women ≥ 18 years of age with singleton gestation ≥37 weeks’ gestation admitted to labor and delivery for planned vaginal delivery. Patients were excluded if the initial triage assessment revealed fetal distress (Category II tracing based on National Institutes of Health consensus criteria), excessive or abnormal vaginal bleeding prior to monitor placement, a history of a prior cesarean delivery, cardiac pacemaker, or skin sensitivity to adhesive. Patients were screened for possible study enrollment at the time of labor and delivery admission or at the time of a routine prenatal care clinic visit. Written informed consent was obtained.

The protocol was approved by the Intermountain Healthcare Institutional Review Board (Salt Lake City, UT, USA) IRB Number: 1050411 and was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov number: NCT03156608).

Randomization and blinding

Randomization occurred in blocks based on BMI (BMI <30 or BMI ≥ 30) to control for the potential effect of BMI. Women were randomized to either the fECG device or SEM (external Doppler and tocometry) using a computer-generated randomization scheme through REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), an electronic data collection tool hosted at Intermountain Healthcare15.

Given the distinctly different appearance of the fetal monitoring devices utilized in this study, participants and respective healthcare providers were not blinded to study device during data collection. However, de-identified FHR tracings were similar in appearance (Supplementary Figure 1). Members of the Intermountain Healthcare Maternal-Fetal Medicine division assigned to review FHR tracings for interpretability were blinded to participant study arm allocation, intrapartum monitor changes and labor outcomes.

Study Outcomes

The primary outcome was the percentage of interpretable minutes generated on study device during the entire intrapartum period [number of interpretable minutes on study device/total minutes in labor], where any time spent on an alternative, non-study device was considered not-interpretable (an intention to treat analysis). Secondary outcomes included the percentage of interpretable minutes generated on study device while on study device only [number of interpretable minutes on study device/total minutes on study device only]. The percentage of interpretable 10 minute FHR tracing segments generated in labor and on study device only was also assessed (e.g. [number of interpretable 10-minute segments on study device/total 10-minute segments in labor] and [number of interpretable 10-minute segments on study device/number 10-minute FHR segments on study device only]).

Additional secondary outcomes included the number of study device adjustments by nursing; the need for an alternative monitoring device; and physician, nursing, and patient satisfaction with study device as determined by immediate post-delivery Likert scale survey. Maternal outcomes (labor length, labor analgesia, delivery mode) and neonatal outcomes (birth weight, neonatal sex, Apgar score (1 and 5 minute), NICU admission, and umbilical cord blood gases (when available)) were abstracted from the medical chart following delivery.

Procedures

Maternal demographic information was collected at study enrollment. Study device was placed following randomization, with assigned device remaining in place until delivery or until provider request for device change. In our study, only nurses were trained in study device placement. In the fECG group, providers could transition to SEM or internal monitoring at their discretion. In the SEM group, providers could switch to internal monitoring (fetal scalp electrode and/or intrauterine pressure catheter) at their discretion. Reason for device change was not protocolized, but was recorded via short provider questionnaire. Device setup was considered successful if the device was placed, initiated appropriately, and no device change was required prior to delivery. Device set up failure occurred when assigned study device did not generate any interpretable tracing at the time of placement despite troubleshooting. All subjects with device set up failures required an alternative monitoring device intrapartum.

Labor nurses recorded the total number of monitor adjustments performed to improve signal quality while on study device. A Likert scale survey assessing user satisfaction with the assigned device was distributed to staff and study participants following delivery.

A complete copy of the intrapartum FHR tracing was collated and de-identified following delivery. A study ID assigned at enrollment was associated with each FHR tracing and was used to link FHR tracing data and clinical data. All FHR tracings were reviewed in blinded fashion by at least two members of the Maternal-Fetal Medicine division.

Each minute of FHR tracing was considered individually. An interpretable minute was defined as >25% FHR data present with no more than 25% continuous missing FHR data or artifact present (Supplementary Figure 2). The FHR tracing was also evaluated in 10-minute segments, where a 10-minute segment was considered interpretable if baseline heart rate, variability and periodic changes could be adequately determined by the reviewer. These definitions of interpretable minute and 10-minute segment terminologies were determined via a priori consensus.

Maternal and neonatal outcome data were abstracted from the medical records by trained research staff.

Statistical Analysis

Sample Size and Power Estimates

A sample size calculation was performed using the assumption that SEM would yield an average of 90% interpretable tracing. This value was based on previously published literature4 and after review of 30 complete FHR tracings from our own institution. We assumed fECG would generate 95% interpretable tracing based on preliminary observational data11. We determined that a sample size of 100 subjects per group (200 total) would result in 95% power to detect a difference in the percentage of interpretable tracing both devices generated.

Data Analysis

Outcomes in the fECG and SEM groups were compared using both univariate and multivariate analysis as appropriate. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables, and student’s t test was utilized for comparison of continuous variables. A generalized linear mixed effects model was employed for comparing individual FHR tracing interpretations using binomial outcomes for readability and other binary outcomes and normal outcomes for numerical responses. The fixed effect was defined as the device that the patient was randomly assigned, and random effects included the patient and reader providing FHR interpretation in order to account for correlation within those groupings. The intraclass correlation coefficient was measured to evaluate FHR tracing reviews for inter-observer variability. All analyses were performed using R statistical software (version 3.4.3) with lme4 package for R16, 17.

A brief post-hoc analysis of device success plotted across the study period was performed to evaluate for study device “learning curve.”

Role of the funding source

This was an investigator initiated, industry-sponsored study (GE Healthcare). GE Healthcare played no role in data collection, analysis or presentation of results.

Results

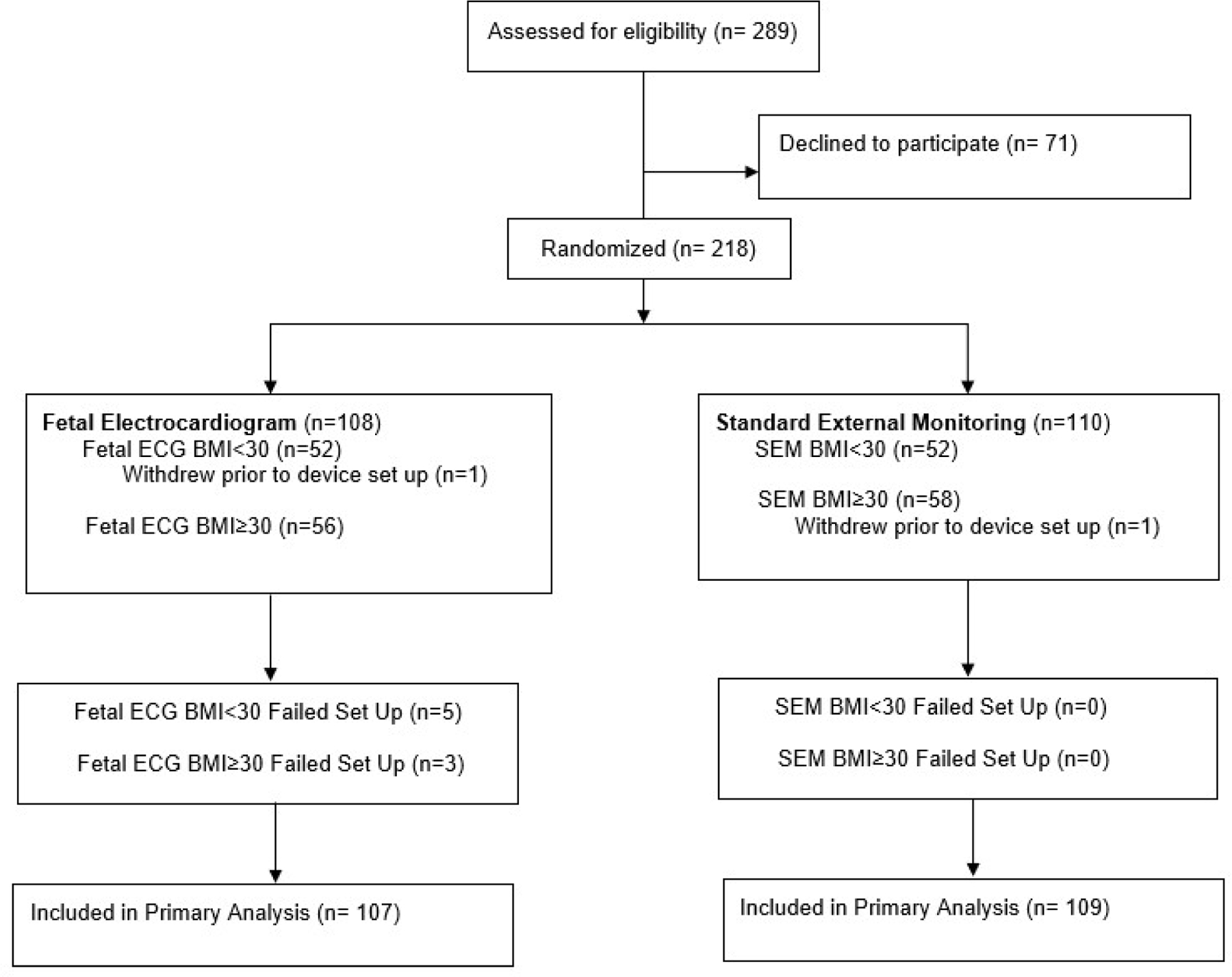

Study enrollment occurred between March 6th and June 28th of 2017. Of the 289 eligible women approached, 218 women consented to the study. 108 women were randomized to fECG and 110 to SEM as depicted in the trial flow chart (Figure 1). In both groups, a single study participant withdrew prior to device set up. These participants were excluded from final analysis.

Figure 1. Randomization and Flow of Participants Through the Trial.

This figure demonstrates a flow diagram of study participant enrollment, randomization and participation during the study period. Abbreviations: ECG, electrocardiogram; SEM, standard electronic monitoring; BMI, body mass index.

There were no statistical differences in maternal demographics between study arms (Table 1). Mean BMI in both groups was approximately 32kg/m2 and labor induction occurred in 80% and 79% of subjects randomized to fECG and SEM, respectively. There were no differences in maternal or neonatal clinical outcomes between study arms including length of labor, delivery mode and previously defined maternal or fetal complications (Table 2).

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| Participant Characteristics | Fetal ECG n=107 |

Standard External Monitoring n=109 |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 29.2 (4.9) | 28.6 (4.9) |

|

| ||

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 31.7 (5.7) | 31.7 (5.9) |

|

| ||

| Gestational Age (weeks), mean (SD) | 39.4 (1.1) | 39.4 (1.0) |

|

| ||

| First Pregnancy (%) | 27.8% | 37.3% |

|

| ||

| Race (%) | ||

| Caucasian | 87.96% | 91.82% |

| Asian | 2.78% | 0.91% |

| Pacific Islander | 4.63% | 4.55% |

| African American | 0.93% | 0.0% |

| Other | 3.7% | 2.73% |

|

| ||

| Ethnicity (%) | 9.3% Hispanic | 9.1% Hispanic |

|

| ||

| Pregnancy complications (%) | ||

| None | 83% | 81% |

| Preeclampsia | 1.9% | 1.8% |

| Chronic Hypertension | 2.8% | 2.7% |

| Gestational Hypertension | 9.3% | 6.4% |

| Gestational Diabetes | 3.7% | 6.4% |

| Preexisting Diabetes | 0% | 0% |

| Intrauterine Growth Restriction | 0.93% | 1.8% |

| Oligohydramnios | 9.3% | 1.8% |

|

| ||

| Labor Type | ||

|

| ||

| Induced | 86 (80%) | 87 (79%) |

Abbreviations: ECG, electrocardiogram; BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation

Table 2.

Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes

| Fetal ECG n=107 |

Standard External Monitoring n=109 |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal outcomes | |||

|

| |||

| Length of labor | 761.8 (482.2) | 679.0 (420.9) | 0.18 |

| Minutes admit to delivery (SD) | |||

|

| |||

| Labor Analgesia | |||

| Epidural, n(%) | 78 (72%) | 81 (74%) | 0.88 |

|

| |||

| Delivery Type | 0.25 | ||

|

| |||

| Spontaneous Vaginal, n(%) | 90 (83%) | 101 (92%) | |

|

| |||

| Operative Vaginal, n(%) | 4 (3.7%) | 4 (3.6%) | |

|

| |||

| Cesarean, n(%) | 11 (10%) | 5 (4.5%) | |

|

| |||

| Indication for Operative | 0.31 | ||

| Vaginal or Cesarean | |||

| Delivery | 53% | 33% | |

| Non-reassuring FHR Tracing | 27% | 56% | |

| Labor Dystocia | 7% | 0% | |

| Fetal Malpresentation | 0% | 11% | |

| Placental Abruption | 13% | 0% | |

| Other | |||

|

| |||

| Fetal Outcomes | |||

|

| |||

| APGAR | |||

|

| |||

| 1 minute, median (IQR) | 7.6 (1.4) | 7.8 (0.9) | 0.41 |

|

| |||

| 5 minutes, median (IQR) | 8.9 (0.5) | 8.9 (0.3) | 0.36 |

|

| |||

| NICU admission (Yes), n(%) | 8 (7.4%) | 7 (6.4%) | 0.79 |

|

| |||

| Birthweight (g), mean (SD) | 3438 (435) | 3495 (458) | 0.36 |

|

| |||

| Neonatal Sex, n(%) | 59 M 46 F (56%, 46%) | 60 M 50 F (55%, 45%) | 0.89 |

|

| |||

| Cord blood gases (if applicable) | 7.2 (0.076) | 7.2 (0.062) | 0.39 |

| Arterial pH, mean (SD) | 7.3 (0.083) | 7.3 (0.047) | 0.19 |

| Venous pH, mean (SD) | |||

Abbreviations: ECG, electrocardiogram; FHR, Fetal Heart Rate; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; NICU, Newborn intensive care unit.

Interpretable Minutes

Approximately 49,000 minutes of FHR tracing in labor were generated and evaluated for both groups. We found no difference in the primary outcome, the percentage of interpretable minutes of FHR tracing produced in labor for all subjects (58.0% in fECG arm vs 58.1% in SEM arm, p= 0.821). In stratified analysis, fECG generated fewer interpretable minutes in subjects with BMI<30 compared with SEM (61.1% vs 66.5% (p<0.001)). However, fECG generated significantly more interpretable minutes compared to SEM in subjects with BMI ≥30, 55.3% vs 51.5% (p<0.001) (Table 3). Of note, there was no significant inter-observer variation with respect to reviewer minute-to-minute FHR tracing interpretation (reviewer to reviewer variance component of 0.012 (SD=0.112)).

Table 3.

Primary Outcome

| % Interpretable Tracing (Interpretable FHR minutes/Total minutes in labor) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcome | ||

| Percentage of interpretable FHR minutes generated in labor | ||

| All Subjects | ||

| Fetal ECG | 58.0% (28,689/49,480) | 0.821 |

| Standard electronic monitoring | 58.1% (28,394/48,911) | |

| Subjects with BMI<30 | ||

| Fetal ECG | 61.1% (13,761/22,506) | < 0.001a |

| Standard electronic monitoring | 66.5% (14,145/21,265) | |

| Subjects with BMI≥ 30 | ||

| Fetal ECG | 55.3% (14,928/26,974) | < 0.001a |

| Standard electronic monitoring | 51.5% (14,249/27,646) | |

Abbreviations: FHR, Fetal Heart Rate; ECG, electrocardiogram; BMI, body mass index

Significant P values (<0.05)

In a secondary analysis of interpretable minutes while on study device, fECG generated significantly more interpretable minutes of FHR tracing compared to SEM for all subjects, regardless of maternal BMI (Table 4). The percentages of interpretable FHR tracing generated by fECG vs. SEM broken down by BMI category during total labor course and on study device only are shown in Supplemental Figure 3.

Table 4.

Secondary Outcomes

| Secondary Outcomes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Percentage of interpretable FHR minutes generated while on study device only | ||

| % Interpretable Tracing (Interpretable FHR minutes/Total minutes on study device) |

p value | |

| All Subjects | ||

| Fetal ECG | 94.5% (28,689/30,355) | <0.001a |

| Standard electronic monitoring | 86.2% (28,394/32,936) | |

| Subjects with BMI<30 | ||

| Fetal ECG | 95.5% (13,761/14,410) | < 0.001a |

| Standard electronic monitoring | 89.3% (14,145/15,840) | |

| Subjects with BMI≥ 30 | ||

| Fetal ECG | 93.6% (14,928/15,945) | < 0.001a |

| Standard electronic monitoring | 83.3% (14,249/17,096) | |

| Percentage of interpretable 10-minute segment generated in labor | ||

| % Interpretable 10-minute blocks (Interpretable 10-minute FHR blocks/Total 10-minute blocks in labor) |

p value | |

| All Subjects | ||

| Fetal ECG | 62.7% (3,321/5,296) | <0.001a |

| Standard electronic monitoring | 58.2% (2,833/4,867) | |

| Subjects with BMI<30 | ||

| Fetal ECG | 73.8% (1,603/2,172) | <0.001a |

| Standard electronic monitoring | 67.2% (1,388/2,066) | |

| Subjects with BMI≥ 30 | ||

| Fetal ECG | 55% (1,718/3,124) | 0.009a |

| Standard electronic monitoring | 51.6% (1,445/2,801) | |

| Percentage of interpretable 10-minute segment generated while on study device only | ||

| % Interpretable 10-minute blocks (Interpretable 10-minute FHR blocks/Total 10-minute blocks on study device) |

p value | |

| All Subjects | ||

| Fetal ECG | 94.9% (3,321/3,499) | <0.001a |

| Standard electronic monitoring | 79.9% (2,833/3,545) | |

| Subjects with BMI<30 | ||

| Fetal ECG | 94.9% (1,603/1,690) | <0.001a |

| Standard electronic monitoring | 82.6% (1,388/1,681) | |

| Subjects with BMI≥ 30 | ||

| Fetal ECG | 95% (1,718/1,809) | <0.001a |

| Standard electronic monitoring | 77.5% (1,445/1,864) | |

Abbreviations: FHR, Fetal Heart Rate; ECG, electrocardiogram; BMI, body mass index

Significant P values (<0.05)

10-Minute Segments

When considering 10-minute segment analysis over the entire labor course, fECG generated more interpretable 10-minute segments than SEM for all subjects, regardless of maternal BMI (Table 4). These findings were magnified in the 10-minute segment analysis while on study device only, where fECG generated significantly more interpretable FHR tracing compared to SEM, regardless of maternal BMI, with approximately 95% interpretable 10-minute segments of tracing generated in fECG for all participants.

Device Set-Up and Change

Device set-up failures were more frequent in the fECG device arm compared to SEM, 7.5% (8/107) vs. 0% (0/109), respectively. All device failures in the fECG arm were secondary to inability to obtain a signal at the time of device set up. Device success was plotted across the study period, where we observed no demonstrable “learning curve” that would suggest that more experience with the “new fetal ECG” device improved successful device placement rates.

Approximately 51% (55/107) of fECG participants switched devices before delivery (21% (23/107) to SEM, 30% (32/107) to internal monitoring), whereas only 39% (43/109) of subjects transitioned to internal monitoring in the SEM group (p=0.12). The most frequently cited reasons for device change for both groups were “gapping or loss of FHR signal” and “need for contraction strength assessment.” Loss of contraction signal was not a commonly cited reason for device switch for either study group.

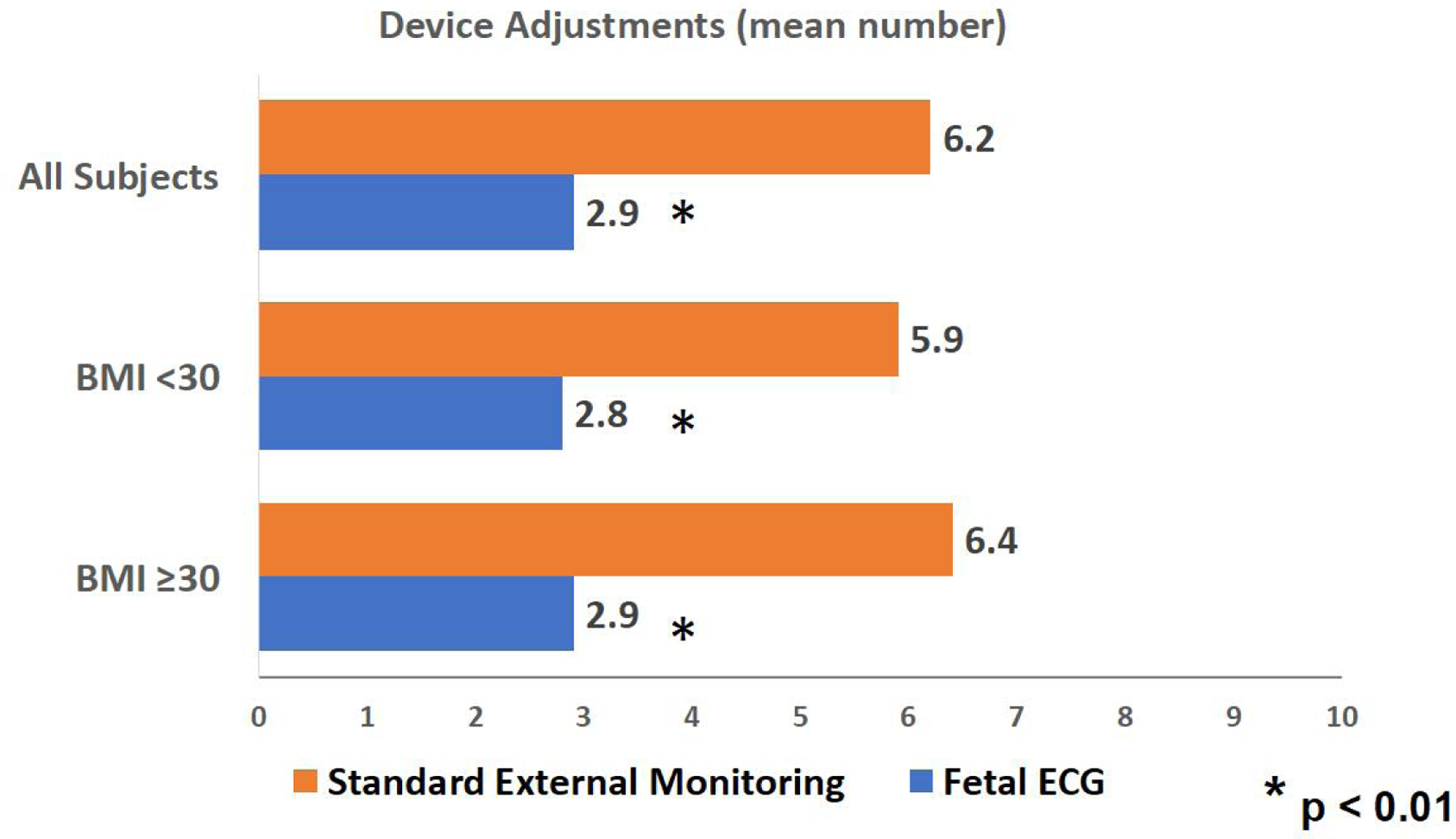

Participants in the fECG group required significantly fewer device adjustments by nursing, less than half the number of device adjustments compared to participants in SEM group, regardless of maternal BMI (2.9 vs. 6.2 mean adjustments intrapartum, p<0.01) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Comparison of device adjustments required intrapartum.

Mean number of device adjustments for all subjects as well as subjects stratified by BMI are shown. Asterisk indicates significant difference between study groups (P value <0.01 where P value <0.05 is considered significant). Abbreviations: ECG, electrocardiogram; BMI, body mass index

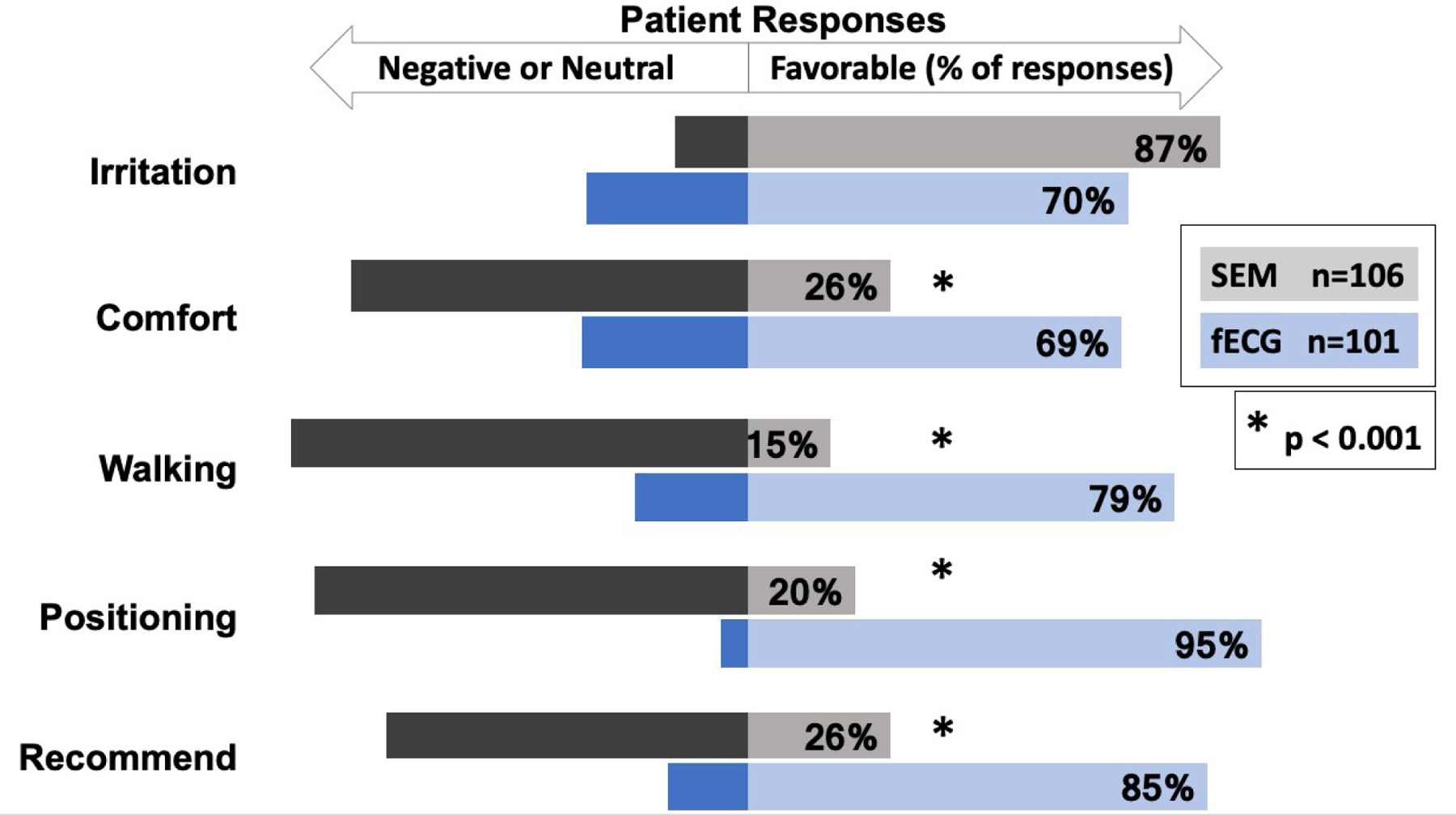

Patient and Provider Satisfaction

Two-hundred and five nursing and 114 provider survey responses were obtained for analysis (Supplementary Figure 4). Nursing and provider satisfaction scores were generally high for both study arms, but nurses reported greater satisfaction with fECG for ease of use for contraction monitoring (p<0.05). Two-hundred and seven patient satisfaction surveys were analyzed and are depicted in Figure 3. Patients reported similar, favorable satisfaction scores regarding skin irritation on assigned device. However, patients reported more favorable satisfaction scores with fECG when considering device comfort, ease of walking and re-positioning in labor (p<0.001). Patients were also more likely to recommend fECG to others in the future compared to patients randomized to SEM (p=0.001).

Figure 3. Patient Device Satisfaction Survey.

Comparison of patient satisfaction scores on assigned study device is shown, where bars oriented to the right indicate a favorable satisfaction score. Neutral and negative responses are indicated with bars oriented to the left. Survey gauged patient satisfaction with respect to skin “Irritation” on assigned device, overall device “Comfort,” ease of “Walking,” Re-“Positioning” in labor as well as whether the patient would be likely to “Recommend” the device to others in the future. Asterisk indicates significant difference between study groups. (P value <0.001 where P value <0.05 is considered significant). Abbreviations: SEM, Standard Electronic Monitoring; ECG, electrocardiogram

Comments

Principal Findings

Our trial demonstrated that fECG matched SEM performance in labor overall, but was superior to SEM in obese (BMI ≥ 30) patients in terms of amount of interpretable FHR tracing generated in labor. When successfully placed, fECG generated more interpretable FHR tracing compared to SEM, regardless of maternal BMI, while on study device only. Our observation of deterioration in SEM performance as maternal BMI increases, is consistent with prior studies4–7. In our study, when considering the quality of the tracing in 10-minute segments in the BMI ≥ 30 category, the percentage of interpretable tracing yielded with SEM was as low as 52%, which highlights SEM’s poor performance in this patient population.

The fECG device appears to be well accepted by providers and nursing staff, and patient satisfaction scores were significantly higher with fECG use compared to SEM secondary to device comfort, ease of positioning and ambulation with the device in place. One particularly appealing feature of the fECG device included the decreased need for device adjustments by nursing staff compared to SEM. However, the fECG device can be difficult to set up as evidenced by our higher device set-up failure rate in the fECG group, ultimately necessitating an alternative FHR monitor, which may make its use less attractive. It is possible that for some patients, the combination of set-up failure and patient factors will result in individual patients being best monitored by SEM or fECG preferentially. Of note, the rate of device set up failure observed in our study is comparable to manufacturer guidelines.

Clinical Implications

Our results highlight the potential clinical utility of the use of fECG systems in the general obstetric population at term, and potential advantage in patients with a BMI over 30. Although the issue of having to switch from fECG to either SEM or internal monitoring may be a barrier to use in some settings, this device may also offer advantages for those with contraindications to internal monitoring or in patients who desire ambulation or frequent position changes in labor. The decreased need for device adjustment suggests the fECG could improve nursing or staffing workflow on labor units. The device also appears to have a positive impact on the patient experience.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this study include the following: (1) Randomized, prospective data collection method; (2) blinded FHR tracing review and interpretation; and (3) intention to treat analysis utilized to determine primary outcome. This study adds to the very limited data available comparing the performance of a new FHR monitoring device (fECG) to SEM in a clinical setting.

Limitations of the study include the intrinsic differences in the appearance of both monitoring devices, which limited blinding. As such, we cannot eliminate the possibility that provider or nursing bias may have played a role in the decision to switch device intrapartum. This may have altered device success rates, thus driving results for all subjects towards the null. Additionally, the unblinded nature of the patient, provider and nursing experience may have also impacted device satisfaction survey scores. Finally, while no adverse maternal or neonatal outcomes were identified with fECG use, this study was not powered to assess device impact on birth outcomes.

Research Implications

Future research should address the impact on birth outcomes, cost analysis for routine or case by base use, the impact of patient ambulation on device performance, device performance in a preterm population, and exploration of issues related to fECG device set up failure.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that the fECG device may generate more interpretable FHR data compared to SEM in traditionally difficult to monitor patients (BMI >30), and is well accepted by patients and staff, suggesting that fECG may be particularly appropriate for use in specific patient populations. FHR tracings can only be evaluated when the signal is adequate and interpretable. SEM techniques have several limitations as previously described. The optimal method for FHR monitoring intrapartum would be easy to use, provide high-quality data, be well accepted by providers and patients, improve clinical outcomes (or at least convey no increased risk for poor outcome), and would not significantly increase the cost of patient care. Limitations with respect to device use and set up exist and should be explored in future studies.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Fetal Heart Rate Tracing Examples

Legend: a. Standard External Monitoring b. Fetal Electrocardiogram (ECG) c. Internal Monitoring. This figure demonstrates a representative tracing from all three fetal heart rate monitoring devices utilized throughout this study (standard external monitoring, fetal electrocardiogram and internal monitoring device). These interpretable tracing examples are similar in appearance and bear no identifying or distinguishing features.

Supplementary Figure 2. Fetal heart rate tracing interpretation example

Legend: This figure depicts a fetal heart rate tracing interpretation example. In this example, the reviewer marked the minutes denoted with “X’s” as “not-interpretable.” In this study, an “interpretable minute” was defined as follows: >25% Fetal Heart Rate data were present, there were <25% continuous missing Fetal Heart Rate data, and artifact was present for <25% of minute.

Supplementary Figure 3. Fetal heart rate tracing interpretation by body mass index category

Supplementary Figure 3a.

This figure demonstrates the percentage of interpretable minutes in labor (intention to treat) generated by both study arms, stratified by body mass index category. Abbreviations: ECG, electrocardiogram; BMI, body mass index

Supplementary Figure 3b.

This figure depicts the percentage of interpretable minutes generated by both study arms while on study device only, stratified by body mass index category. Abbreviations: ECG, electrocardiogram; BMI, body mass index

Supplementary Figure 4. Nursing and Provider Satisfaction Survey Responses

Supplementary Figure 4a.

This figure demonstrates Nursing staff Likert scale satisfaction survey responses for assigned study device. Survey responses were obtained following study subject delivery. A total of 205 nursing staff responses were received at study conclusion.

Supplementary Figure 4b.

This figure shows delivery Provider Likert scale satisfaction survey responses for assigned study device. Survey responses were obtained following study subject delivery. A total of 114 delivery provider responses were received at study conclusion.

AJOG at a Glance.

To compare the interpretability of two abdominal fetal heart rate monitoring devices (fetal electrocardiography versus standard external monitoring).

In this randomized clinical comparison, fetal heart rate interpretability was similar between groups, but fetal electrocardiography generated more interpretable data compared to standard external monitoring in women with BMI ≥30 and resulted in higher patient satisfaction.

Fetal electrocardiography was better accepted by patients, and may be a preferable fetal monitoring device in obese patients.

Acknowledgments

This research was sponsored by Intermountain Healthcare and funded in part by GE Healthcare. Date of Registration: March 14, 2017

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

ClinicalTrials.gov number: NCT03156608

Conflict of Interes

Authors report no conflict of interest.

Disclosure Statement

Presented in part at the 2019 Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine Meeting, Las Vegas, NV on February 15, 2019

Condensation

External fetal ECG system generated similar interpretable fetal heart rate tracing data overall compared to standard external Doppler, but was superior in women with BMI≥30.

References

- 1.Chen H-Y, Chauhan SP, Ananth CV, et al. Electronic fetal heart rate monitoring and its relationship to neonatal and infant mortality in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;204:491.e1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinas A and Chandraharan E. Continuous cardiotocography during labour: Analysis, classification and management. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2016;30:33–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ayres-de-Campos D Introduction: Why is intrapartum foetal monitoring necessary – Impact on outcomes and interventions. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2016;30:3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakker PCAM, Colenbrander GJ, Verstraeten AA, Van Geijn HP. The quality of intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2004;116:22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dawes GS. Numerical analysis of the human fetal heart rate: the quality of ultrasound records. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1981;141:43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rooth G, Huch A, Huch R. FIGO news: guidelines for the use of fetal monitoring. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1987;25:159–167. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spencer JAD, Belcher R, Dawes GS. The influence of signal loss on the comparison between computer analyses of the fetal heart rate in labour using pulsed Doppler ultrasound (with autocorrelation) and simultaneous scalp electrocardiogram. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1987;25:29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen WR, Ommani S, Hassan S, et al. Accuracy and reliability of fetal heart rate monitoring using maternal abdominal surface electrodes. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2012;91:1306–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reinhard J, Hayes-Gill BR, Yi Q, Hatzmann H, Schiermeier S. Comparison of non-invasive fetal electrocardiogram to Doppler cardiotocogram during the first stage of labor. J Perinat Med 2010. Mar;38(2): 179–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen WR, Hayes-Gill B. Influence of maternal body mass index on accuracy and reliability of external fetal monitoring techniques. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2014;93:590–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graatsma EM, Miller J, Mulder EJ, Harman C, Baschat AA, Visser GH. Maternal body mass index does not affect performance of fetal electrocardiography. Am J Perinatol 2010. Aug;27(7):573–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Euliano TY, Darmanjian S, Nguyen MF, Busowsi JD, Euliano N, Gregg AR. Monitoring Fetal Heart Rate during Labor: A Comparison of Three Methods. J Pregnancy 2017;2017:8529816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayes-Gill B, Hassan S, Mirza FG, et al. Accuracy and Reliability of Uterine Contraction Identification Using Abdominal Surace Electrodes. Clin Med Insights Womens Health 2012;5:65–75. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kapaya H, Dimelow E, Anumba D. Women’s experience of wearing a portable fetal electrocardiogram device to monitor small-for-gestational age fetus in their home environment. Womens Health (Lond) 2018;14:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.R Core Team (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available from: URL https://www.R-Project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. J Stat Softw 2015;67(1):1–48. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Fetal Heart Rate Tracing Examples

Legend: a. Standard External Monitoring b. Fetal Electrocardiogram (ECG) c. Internal Monitoring. This figure demonstrates a representative tracing from all three fetal heart rate monitoring devices utilized throughout this study (standard external monitoring, fetal electrocardiogram and internal monitoring device). These interpretable tracing examples are similar in appearance and bear no identifying or distinguishing features.

Supplementary Figure 2. Fetal heart rate tracing interpretation example

Legend: This figure depicts a fetal heart rate tracing interpretation example. In this example, the reviewer marked the minutes denoted with “X’s” as “not-interpretable.” In this study, an “interpretable minute” was defined as follows: >25% Fetal Heart Rate data were present, there were <25% continuous missing Fetal Heart Rate data, and artifact was present for <25% of minute.

Supplementary Figure 3. Fetal heart rate tracing interpretation by body mass index category

Supplementary Figure 3a.

This figure demonstrates the percentage of interpretable minutes in labor (intention to treat) generated by both study arms, stratified by body mass index category. Abbreviations: ECG, electrocardiogram; BMI, body mass index

Supplementary Figure 3b.

This figure depicts the percentage of interpretable minutes generated by both study arms while on study device only, stratified by body mass index category. Abbreviations: ECG, electrocardiogram; BMI, body mass index

Supplementary Figure 4. Nursing and Provider Satisfaction Survey Responses

Supplementary Figure 4a.

This figure demonstrates Nursing staff Likert scale satisfaction survey responses for assigned study device. Survey responses were obtained following study subject delivery. A total of 205 nursing staff responses were received at study conclusion.

Supplementary Figure 4b.

This figure shows delivery Provider Likert scale satisfaction survey responses for assigned study device. Survey responses were obtained following study subject delivery. A total of 114 delivery provider responses were received at study conclusion.