Abstract

Background

The use of loop ileostomy or loop transverse colostomy represents an important issue in colorectal surgery. Despite a slight preference for a loop ileostomy as a temporary stoma, the best form for temporary decompression of colorectal anastomosis still remains controversial.

Objectives

To assess the evidence in the use of loop ileostomy compared with loop transverse colostomy for temporary decompression of colorectal anastomosis, comparing the safety and effectiveness.

Search methods

We identified randomised controlled trials from MEDLINE, EMBASE, Lilacs, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. Further, by hand‐searching relevant medical journals and proceedings from major gastroenterological congresses. We did not limit the seaches regarding date and language.

Selection criteria

We assessed all randomised clinical trials, that met the objectives and reported major outcomes: 1. Mortality; 2. Wound infection; 3. Time of formation of stoma; 4. Time of closure of stoma; 5. Time interval between formation and closure of stoma; 6. Stoma prolapse; 7. Stoma retraction; 8. Parastomal hernia; 9. Parastomal fistula; 10. Stenosis; 11. Necrosis; 12. Skin irritation; 13. Ileus; 14. Bowel leakage; 15. Reoperation; 16. Patient adaptation; 17. Length of hospital stay; 18. Colorectal anastomotic dehiscence; 19. Incisional hernia; 20. Postoperative bowel obstruction.

Data collection and analysis

Details of the randomisation, blinding, whether an intention‐to‐treat analysis was done, and the number of patients lost to follow‐up was recorded. For data analysis the relative risk and risk difference were used with corresponding 95% confidence interval; fixed effect was used for all outcomes unless incisional hernia (random effect model). Statistical heterogeneity in the results of the meta‐analysis was assessed by inspection of graphical presentation (funnel plot) and by calculating a test of heterogeneity.

Main results

Five trials were included with 334 patients: 168 to loop ileostomy group and 166 to loop transverse colostomy group. The continuous outcomes could not be measured because of the lack of the data. The outcomes stoma prolapse had statistical significant difference: p=0.00001, but with statistical heterogeneity, p=0,001. When the sensitive analysis was applied excluding the trials that included emergencies surgeries, the result had a discreet difference: p = 0.02 and Test for heterogeneity: chi‐square = 0.78, df = 2, p = 0.68, I2=0%.

Authors' conclusions

The best available evidence for decompression of colorectal anastomosis, either use of loop ileostomy or loop colostomy, could not be clarified from this review. So far, the results in terms of occurrence of postoperative stoma prolapse support the choice of loop ileostomy as a technique for fecal diversion for colorectal anastomosis, but large scale RCT's is needed to verify this.

Plain language summary

Ileostomy or colostomy for temporary decompression of colorectal anastomosis

Anastomotic leakage after left‐sided colorectal resections is a serious complication, which leads to increase morbidity and mortality and prolonged the hospital stay. Proximal fecal diversion may limit the consequences of anastomotic failure. It remains controversial whether a loop ileostomy or a loop transverse colostomy is a better form of fecal diversion. This review included five randomised trials (334 patients), comparing loop ileostomy (168 patients) and loop colostomy (166 patients) used to decompression of a colorectal anastomosis. Except for stoma prolapse, none of the reported outcomes reported were statistically or clinically significant. Continuous outcomes, such as lenght of hospital stay, was not included due to insufficient data reported in the primary studies.

Background

Anastomotic leakage is one of the most important surgical complication of colorectal surgery, and it has been of great concern due to high occurrence of morbidity and mortality, affecting long‐term survival (McArdle 2005). It has been reported as a primary outcome in many reviews (Lustosa 2001, Guenaga 2003). The incidence of clinical anastomotic leakage after resection of the colon and rectum has been reported to vary between 1.8 and 5 percent, and even as high as 15 percent in low rectal anastomosis (Makela 2003). Numerous factors are associated with the occurrence of anastomotic leakage. A protective stoma should be considered relating to specifics conditions involving the operation (low tumour, narrow male pelvis, complications during construction of the anastomosis), or other situationssuch as: poor initial condition of the patient, after neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy, after total mesorectal excision, preoperative steroid use and long duration of operation (Gastinger 2005, Konishi 2006). The proximal diversion, either by a colostomy or an ileostomy, by preventing fecal flow through the anastomosis, minimizes the consequences of the anastomotic leak (Dehni 1998, Rullier 1998, Poon 1999, Alberts 2003, Peeters 2005). Although temporary decompression of colorectal anastomosis delineates a conception accepted by most surgeons, some controversy still remains as to whether loop ileostomy or loop colostomy is the best way of defunctioning such anastomosis. Some randomised controlled trials have been reported but there is still no consensus. In a survey with colorectal surgeons involved in the colorectal residency programs the data obtained showed the preference for a loop ileostomy as a temporary stoma (Hool 1998), as have others (Khoury 1986; Law 2002). Convincingly significant differences of complications rates between the two methods is still to be presented, particularly the stoma‐related ones (Khoury 1986, Gooszen 1998, Edwards 2001). Four randomised controlled trials have compared these two different techniques of defunctioning colorectal anastomosis, two in favour of loop transverse colostomy (Gooszen 1998, Law 2002), and two have recommended ileostomy (Khoury 1986, Williams 1986). In other non randomised publications the construction of a loop ileostomy is the choice of preference unless hard evidence is available in favour of loop colostomy ( Wexner 1993, Torkington 1998, O' Leary 2001). Both types of stoma carry a high complication rate with a considerable mortality rate (Göhring 1988). Usually the interval between stoma construction and closure has a substantial impact on social and economic status. Furthermore, quality of life issues need to be addressed (Silva 2003), as there seems to be a clear relationship between stoma care problems and the degree of social restriction. Thus, not only a careful surgical technique, but also a good choice of stoma type has been advocated for a healthy stoma (Gooszen 2000). Clearly, it remains controversial whether loop ileostomy or loop colostomy is the most favourable proximal diversion of a colorectal anastomosis. The objective of this review was to evaluate the evidence for loop ileostomy compared to loop transverse colostomy for temporary decompression of colorectal anastomosis.

Objectives

To compare safety and effectiveness of loop transverse stoma and loop ileostomy for temporary decompression of colorectal anastomosis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All published and unpublished randomised controlled trials comparing loop ileostomy with loop transverse colostomy for temporary decompression of colorectal anastomosis. Non‐randomised studies will be regarded for descriptive inclusion in order to determinate the rates of adverse events of each operation.

Trials were considered for inclusion if they fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: ‐ Randomised controlled trials that were done to answer the primary question of the review: "loop transverse colostomy or loop ileostomy for temporary decompression for colorectal anastomosis". ‐ No restrictions regarding the language or date of publication. The data from the studies published in full‐text papers, abstracts, as well as, unpublished studies were scrutinized, included and extracted.

Types of participants

Patients submitted to colorectal anastomoses covered by either an ileostomy or a transverse colostomy. No restrictions to age or gender.

Types of interventions

Trials reporting the use of loop transverse colostomy compared with loop ileostomy for temporary decompression to protect a colorectal anastomosis.

Types of outcome measures

1. Mortality ‐ number of death due to formation or closure of the stoma. 2. Wound infection ‐ discharge of pus from the abdominal wound after formation or closure of the stoma. 3. Time of stoma formation ‐ time taken to perform the stoma. 4. Time of stoma closure ‐ time taken to restore the bowel continuity. 5. Time interval between formation and closure of stoma ‐ time taken from construction to closure of the stoma. 6. Stoma prolapse ‐ eversion of the stoma through the abdominal wall. 7. Stoma retraction ‐ deepening of the stoma into the peritoneal cavity. 8. Paraostomal hernia ‐ formation of a hernia beside the stoma. 9. Paraostomal fistula ‐ intestinal leakage from the bowel in the stoma site. 10. Stenosis ‐ narrowing of the stoma lumen. 11. Necrosis ‐ vascular Ischaemic alteration of the bowel in the stoma. 12. Skin irritation ‐ symptomatic alteration of the peristomal skin. 13. Ileus ‐ temporary bowel disfunction after the closure of the stoma. 14. Bowel leakage ‐ leakage from the bowel after the closure of the stoma. 15. Reoperation ‐ need of reoperating on the patient for stoma complication after the formation or closure of the stoma. 16. Patient adaptation ‐ leakage from the appliance, number of appliances changed required per day, alterations in diet, need of medication and degree of odour, flatus from the stoma and psychosocial sequelae. 17. Length of hospital stay ‐ time passed between the surgery of stoma formation or stoma closure and the hospital discharge. 18. Colorectal anastomotic dehiscence ‐ discharge of faeces from the anastomosis site, externalising through the drainage opening or the wound incision; or just the existence of an abscess adjacent to the anastomosis site. The anastomotic leakage was confirmed by either clinical or radiological investigation. 19. Incisional hernia ‐ formation of a hernia after the closure of the stoma site. 20. Postoperative bowel obstruction ‐ any mechanical obstruction of bowel which requires conservative or surgical treatment.

The outcome measures were divided into 4 categories:

A ‐ General outcome measures: mortality, wound infection, time interval between formation and closure of the stoma, length of hospital stay, reoperation and colorectal anastomotic dehiscence.

B‐ Construction of the stoma outcome measures: time of formation, stoma prolapse, stoma retraction, stoma necrosis, parastomal hernia, parastomal fistula and stoma stenosis.

C‐ Closure of the stoma outcome measures: bowel leakage, time of stoma closure, incisional hernia and postoperative bowel obstruction.

D ‐ Functioning stoma outcome measures: patient adaptation, skin irritation and postoperative ileus.

Search methods for identification of studies

See Collaborative Review Group Search Strategy.

The following bibliographic databases were searched in order to identify relevant primary studies:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 2005), MEDLINE (from 1966 to April 2005), EMBASE (from 1980 to April 2005), LILACS (from 1988 to April 2005) and Cochrane Colorectal Cancer Group specialised register SR‐COLOCA.

The bibliographic references of identified RCTs, textbooks, reviews articles and meta‐analyses were checked in order to find RCTs not identified by electronic searches. In addition, randomised clinical trials were searched for by personal communication with colleagues.

The following search strategy was used to search the databases:

#1 Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy for RCTs (Dickersin 1994) #2 Mh COLOSTOM$ OR Tw COLOSTOM$ OR Ti Colostom$ #3 Mh ILEOSTOM$ OR Tw ILEOSTOM$ OR Ti ILEOSTOM$ #4 #2 AND #3 #5 #4 AND #1

Data collection and analysis

The reviewers searched the databases according to the search strategy specified and selected the trials included in this review. Disagreements were solved in consensus. Reviewers were blinded in relation to the report authors, journals, dates of publication and sources of financial support or results.

Location and selecting studies: All identified trials were reviewed independently by the authors in order to evaluate, whether the trial should be included or not. Excluded studies are listed in the table of excluded studies, with reasons for exclusion.

Critical appraisal of studies: The methodological quality of each trial was assessed by the reviewers. The following pre‐specified characteristics of all included RCTs were extracted: ‐ Methods: diagnostic procedures, randomisation procedure, concealment of allocation, sample size calculation and length of follow‐up. ‐ Participants: classification of disease, age, number of patients randomised and reasons for withdrawal from the study will be analysed. ‐ Interventions: loop ileostomy and loop colostomy. When necessary information was missing from a published trial, the primary author were contacted to give the details.

Collecting data: Recorded data was cross‐checked. The data was entered into MetaView in RevMan 4.2.8 for analysis.

Validation study was investigated by analysis of participants, interventions and outcome measures. The studies were stratified for metanalysis according to items above and also the clinical homogeneity. For dichotomous outcome measures metanalysis was performed using risk difference and relative risk, with the corresponding 95% confidence interval. The fixed effect model was used in all outcomes except one, incisional hernia because there was a significant heterogeneity among the trials and the reviewers performed a random effect meta‐analysis.

Statistical heterogeneity in the results of the metanalysis was assessed by inspection of graphical presentation (funnel plot) and by calculating a test of heterogeneity (standard chi‐squared test on N degrees of freedom, where N equals the number of trials minus one). Three possible reasons for trials results heterogeneity were pre‐specified: difference in the methodological quality, sample size and clinical heterogeneity. Clinical heterogeneity was assessed by clinical experts ‐ the reviewers. So clinical evaluation was used for differentiation between specific stoma complication and complication due to systemic changes.

Sensitivity analyses was done excluding studies where there is some ambiguity as to whether they meet the inclusion criteria: excluding studies including emergencies surgeries or higher colorectal anastomosis.

Improving and updating review: At a minimum, updates will be considered on an annual basis. Even if no substantive new evidence is found on annual review and no major amendment is indicated, the date of the latest search for evidence should be made clear in the search strategy section of the review.

Results

Description of studies

Five studies met the inclusion criteria (Edwards 2001; Gooszen 1998; Khoury 1986; Law 2002; Williams 1986) involving 334 patients: 168 in the loop Ileostomy group and 166 in the loop colostomy group.

Two of the trials (Edwards 2001, Law 2002) included only patients underwent anterior resection and total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Three trials (Khoury 1986, Williams 1986, Gooszen 1998) analysed patients submitted to surgery of the left‐sided colon and rectum. One of them (Gooszen 1998) included emergency operations.

Four of the included studies described the technique of the stomas construction, Edwards 2001 did not describe this.

Three studies (Khoury 1986, Williams 1986, Edwards 2001) reported that the deaths were not attributable to either formation or closure of the stoma. One trial (Law 2002) described three deaths in the early postoperative after stoma construction.

One study (Williams 1986) analysed the outcome incisional hernia in the stoma wounds observed up to 2.5 years after closure.

All of the five trials described the statistical analysis.

Only one study (Law 2002) described the sample size calculation with the outcome "small bowel obstruction".

For a detailed description of studies see table of 'Characteristics of included studies.

Five studies (Fasth 1980; Göhring 1988; Lassalle 1990; Popovic 2001; Rutegard 1987) were not included in the review due to reasons specified in the table 'Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

The methodological quality was evaluated independently by the authors. It was assessed by the generation of the allocation sequence and allocation concealment. Allocation sequence was regarded adequate in one study (Khoury 1986), and unclear in the four other (Edwards 2001; Gooszen 1998; Law 2002; Williams 1986) Allocation concealment was regarded as adequate in three trials (Williams 1986, Edwards 2001, Law 2002), and unclear in two trials (Khoury 1986, Gooszen 1998).

Effects of interventions

The results are presented according to the different outcome measures reported: General outcome measures; construction of the stoma; closure of the stoma; stoma functioning. The statistical analysis is presented using Risk Difference and Relative Risk with the corresponding 95% confidence interval. The total number of patients included in the meta‐analysis was 334 patients: 168 in the loop ileostomy group (Group A) and 166 in the loop colostomy group (Group B).

Due to insufficient data, the reported continuous outcomes are presented in a descriptive way. Two summary statistics are commonly used for meta‐analysis of continuous data: the mean difference and the standardised mean difference. These can be calculated whether the data from each individual are single assessments or change from baseline measures. It is also possible to measure effects by taking ratios of means, or by comparing statistics other than means (e.g. medians). The trials did not show the results of each patient and it was not possible to calculate individual data. The following outcomes were described in the five included trials: ‐ Time of formation of stoma (Williams 1986, Edwards 2001); ‐ Time of closure of stoma (Khoury 1986, Williams 1986, Edwards 2001, Law 2002); ‐ Time interval between formation and closure of stoma (Williams 1986, Edwards 2001, Law 2002); ‐ Length of hospital stay: ‐ ‐ Before closure the stoma (Law 2002), ‐ ‐ After closure (Williams 1986, Edwards 2001, Law 2002), ‐ ‐ Total days in hospital (Khoury 1986).

A number of outcomes are not presented graphically, as the event was reported in only one trial, or the fact of the sample size being inadequate: ‐ Stenosis (Gooszen 1998), ‐ Necrosis (Gooszen 1998), ‐ Patient adaptation: Three of the sub‐category patient adaptation: ‐ ‐ Number of appliances changed required per day (Khoury 1986), ‐ ‐ Alteration in diet (Gooszen 1998), ‐ ‐ Need of medication and degree of odour (Williams 1986).

Two of the sub‐category patient adaptation were not analysed in any of the included trials: ‐ ‐ Flatus from the stoma, ‐ ‐ Psychosocial sequelae.

A ‐ General outcome measures:

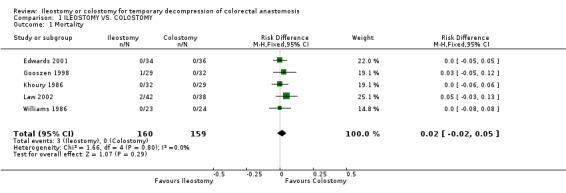

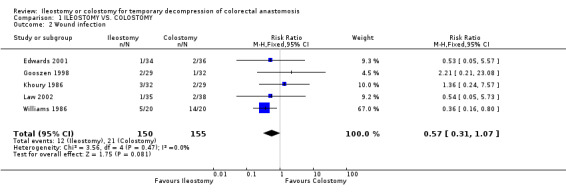

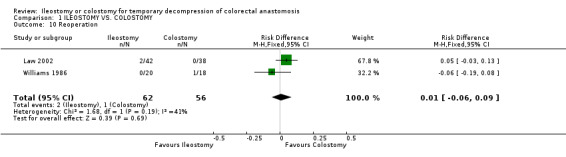

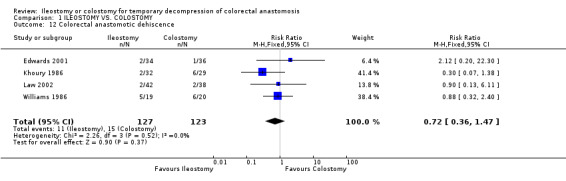

1. Mortality: 2% (3 of 160 patients in Group A) compared to 0% (0 of 159 patients in Group B); RD 0.02, 95% CI: ‐0.02 to 0.05 (non‐significant). There was no statistical heterogeneity in this comparison (Test for heterogeneity chi‐square = 1.66, df = 4, p = 0.80, I2 = 0%). Described in all included trials (Khoury 1986, Williams 1986, Gooszen 1998, Edwards 2001, Law 2002). 2. Wound infection: 8% (12 of 150 patients in Group A) compared to 14% (21 of 155 patients in Group B); RR 0.57, 95% CI: 0.31 to 1.07 (non‐significant; p = 0.08). There was no statistical heterogeneity in this comparison (Test for heterogeneity chi‐square = 3.56, df = 4, p = 0.47, I2 = 0%). Described in all included trials. 3. Colorectal anastomotic dehiscence: 9% (11 of 127 patients in Group A) compared to 12% (15 of 123 patients in Group B); RR 0.72, 95% CI: 0.36 to 1.47 (non‐significant). There was no statistical heterogeneity in this comparison (Test for heterogeneity chi‐square = 2.26, df = 3, p = 0.52, I² = 0%). Described in four included trials (Khoury 1986, Williams 1986, Edwards 2001, Law 2002). 4. Reoperation: 3% (2 of 62 patients in Group A) compared to 2% (1 of 56 patients in Group B); RD 0.01, 95% CI: ‐0.06 to 0.09 (non‐significant). There was no statistical heterogeneity in this comparison (Test for heterogeneity chi‐square = 1.68, df = 1, p = 0.19, I² = 40.6%). Described in two included trials (Williams 1986, Law 2002).

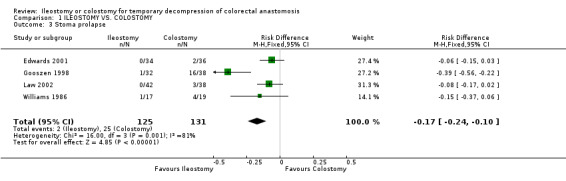

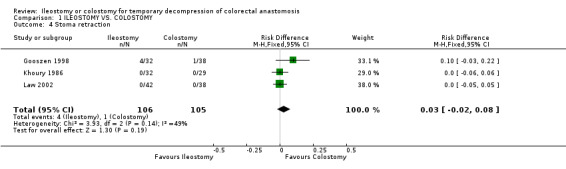

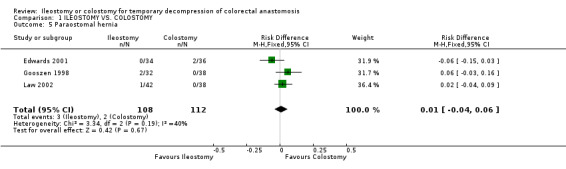

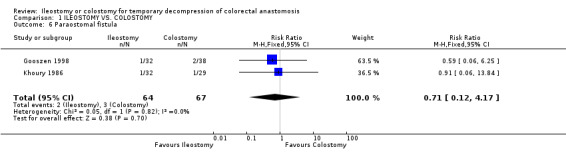

B‐ Outcomes related to the construction of the stoma: 1. Stoma prolapse: 2% (2 of 125 patients in Group A) compared to 19% (25 of 131 patients in Group B); RD ‐0.17, 95% CI: ‐0.24 to ‐0.10 (p<0.00001). There was statistical heterogeneity in this comparison (Test for heterogeneity chi‐square = 15.00, df = 3, p = 0.001, I² = 81.2%). In four studies (Williams 1986, Gooszen 1998, Edwards 2001, Law 2002). 2. Stoma retraction: 4% (4 of 106 patients in Group A) compared to 1% (1 of 105 patients in Group B); RD 0.03, 95% CI: ‐0.02 to 0.08 (non‐significant). There was no statistical heterogeneity in this comparison (Test for heterogeneity chi‐square = 3.93, df = 2, p = 0.14, I² = 49.1%). In three studies (Khoury 1986, Gooszen 1998, Law 2002). 3. Paraostomal hernia: 3% (3 of 108 patients in Group A) compared to 2% (2 of 112 patients in Group B); RD 0.01, 95% CI: ‐0.04 to 0.06 (non‐significant). There was no statistical heterogeneity in this comparison (Test for heterogeneity chi‐square = 3.34, df = 2, p = 0.19, I² = 40.1%). In three studies (Gooszen 1998, Edwards 2001, Law 2002). 4. Paraostomal fistula: 3% (2 of 64 patients in Group A) compared to 4% (3 of 67 patients in Group B); RR 0.71, 95% CI: 0.12 to 4.17 (non‐significant). There was no statistical heterogeneity in this comparison (Test for heterogeneity chi‐square = 0.05, df = 1, p = 0.82, I² = 0%). In two trials (Khoury 1986, Gooszen 1998).

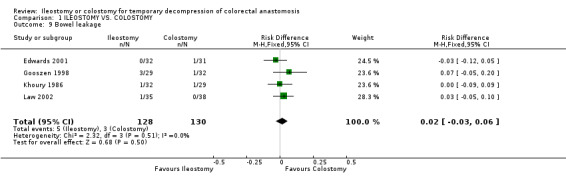

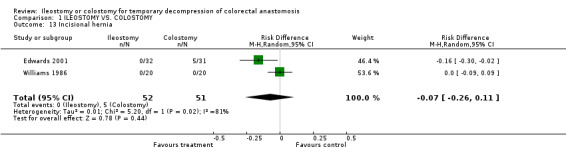

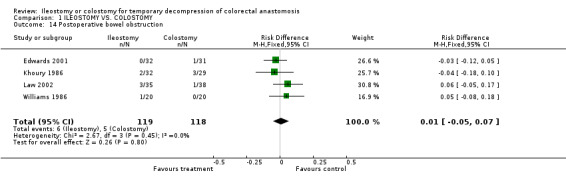

C‐ Outcomes related to the closure of the stoma: 1. Bowel leakage: 4% (5 of 128 patients in Group A) compared to 2% (3 of 130 patients in Group B); RD 0.02, 95% CI: ‐0.03 to 0.06 (non‐significant). There was no statistical heterogeneity in this comparison (Test for heterogeneity chi‐square = 2.32, df = 3, p = 0.51, I² =0%). Described in four trials (Khoury 1986, Gooszen 1998, Edwards 2001, Law 2002). 2. Incisional hernia: 0% (0 of 52 patients in Group A) compared to 10% (5 of 51 patients in Group B); RD ‐0.07, 95% CI: ‐0.26 to 0.11 (non‐significant) in random effect meta‐analysis. There was statistical heterogeneity in this comparison (Test for heterogeneity chi‐square = 5.20, df = 1, p = 0.04, I² = 80.8%). Described in two trials (Williams 1986, Edwards 2001). 3. Postoperative bowel obstruction: 5% (6 of 119 patients in Group A) compared to 4% (5 of 118 patients in Group B); RD 0.01, 95% CI: ‐0.05 to 0.07 (non‐significant). There was no statistical heterogeneity in this comparison (Test for heterogeneity chi‐square = 2.67, df = 3, p = 0.45, I² = 0%). In four studies (Khoury 1986, Williams 1986, Edwards 2001, Law 2002).

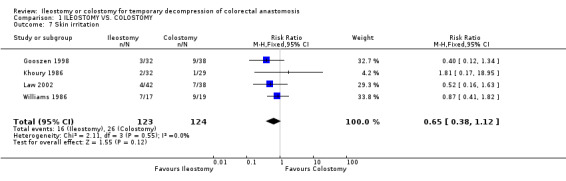

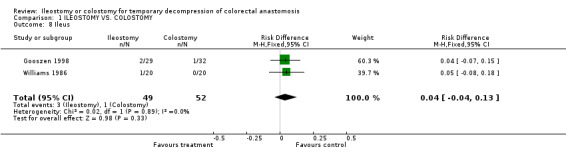

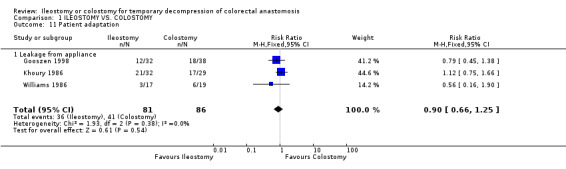

D ‐ Outcomes related to the functioning stoma: 1. Patient adaptation: included six sub‐categories: ‐ Leakage from appliance: 43% (36 of 81 patients in Group A) compared to 48% (41 of 86 patients in Group B); RR 0.90, 95% CI: 0.66 to 1.25 (non‐significant). There was no statistical heterogeneity in this comparison (Test for heterogeneity chi‐square = 1.93, df = 2, p = 0.38, I² = 0%). Described in three studies (Khoury 1986, Williams 1986, Gooszen 1998). 2. Skin irritation: 13% (16 of 123 patients in Group A) compared to 21% (26 of 124 patients in Group B); RR 0.65, 95% CI: 0.38 to 1.12 (non‐significant). There was no statistical heterogeneity in this comparison (Test for heterogeneity chi‐square = 2.11, df = 3, p = 0.55, I² = 0%). Described in four trials (Khoury 1986, Williams 1986, Gooszen 1998, Law 2002). 3. Ileus: 6% (3 of 49 patients in Group A) compared to 2% (1 of 52 patients in Group B); RD 0.04, 95% CI: ‐0.04 to 0.13 (non‐significant). There was no statistical heterogeneity in this comparison (Test for heterogeneity chi‐square = 0.02, df = 1, p = 0.89, I² = 0%).Described in two trials (Williams 1986, Gooszen 1998).

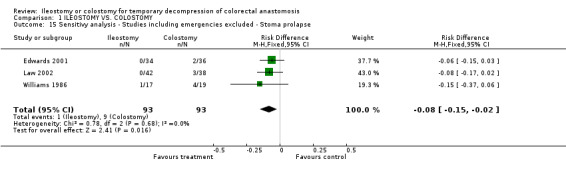

Sensitivity analyses: Studies including emergencies surgery were excluded in the outcome stoma prolapse, that was statistical significant with statistical heterogeneity. ‐ Studies including emergencies excluded (Williams 1986, Edwards 2001, Law 2002) ‐ stoma prolapse: 1% (1 of 93 patients in Group A) compared to 10% (9 of 93 patients in Group B); RD ‐0.08, 95% CI: ‐0.15 to ‐0.02 (p=0.02). There was no statistical heterogeneity in this comparison (Test for heterogeneity chi‐square = 0.78, df = 2, p = 0.68, I² = 0%).

Discussion

The discussion is presented according to the four categories in the result section. The authors believe that this way of presenting the results and the discussion could help to understand the full concept of the entire procedure: from stoma formation, the period with the stoma, to the closure of the stoma.

A ‐ General outcome measures:

Overall analysis of this group of outcomes showed no difference on the mortality, wound infection, colorectal anastomotic dehiscence or reoperation, whether patients were submitted to loop ileostomy or loop colostomy. The inclusion of patients with complications from underlying disease and emergency surgery, is probably not related to a specific type of stoma. This might explain a greater number of deaths reported in one of the trials (Gooszen 1998). As stated in the protocol (Matos 2004), we attempted to extract mortality data associated with stoma formation, but was unable to do this from the study by Gooszen 1998. Colorectal anastomotic dehiscence is considered the most important outcome, once the stoma was created. One of the trials (Gooszen 1998) did not analyse this outcome. Due to a limited number of included participants, we were unable to present meaningful results.

Generally it is accepted that a loop ileostomy is more difficult to construct than a loop colostomy (Hawley 1979, Williams 1986). However this review was unable to show these difficulties in the construction of the stomas, as the mean difference and the standardised mean difference of the continuous data (time of stoma formation) could not be calculated from the results from the trials.

B ‐ Construction of stoma outcome measures: Stoma prolapse has statistical significance but with pronounced heterogeneity between the included trials. The statistical heterogeneity depends on the clinical and methodological differences within the trials. Inevitably, studies brought together in a systematic review will differ. Each of the included trials was quality assessed independently by the reviewers and then compared, trying to distinguish the type of heterogeneity. At this instance, the variability was found in the interventions ‐ emergencies surgeries ‐ included by one of the authors (Gooszen 1998). If we excluded the trial that included emergencies operations, there was no more statistical or clinical heterogeneity among the other trials.

The occurrence of parastomal hernia after the construction of a loop ileostomy or loop colostomy depends upon the same risk factors for stoma prolapse and incisional hernia. Thus the size of fascia defect and wound infection might be the main initial factors for these complications. This review was unable to show significant difference in the incidence of that postoperative complication, which occured in a small number of patients. The available evidence so far does not allow us to conclude for superiority of one faecal diversion procedure when parastomal hernia is taken into account.

C ‐ Closure of stoma outcome measures: For analysis of the outcome 'incisional hernia', the random effect model was applied because the test of heterogeneity using the fixed effect model had a significant difference. Submitting the result to the random effects analysis the reviewers made the assumption that individual studies are estimating different treatment effects, following some distribution. The idea of a random effects meta‐analysis is to learn about this distribution of effects across different studies. The heterogeneity among included trials can be visualised by looking at the inclusion criteria of the participants: one trial (Williams 1986) analyzed all patients who underwent elective colorectal surgery regardless diagnosis, while another (Edwards 2001) only included patients undergoing anterior resection and total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer.

According to one of the authors (Edwards 2001), loop colostomy appears somewhat easier to close than loop ileostomy. The increased risk of deep wound dehiscence, due to greater contamination of the wounds at the time of closure, might be the main factor for this postoperative complication (Lewis 1982). Alternatively the spout of an ileostomy may also reduce the leakage of fecal fluid during mobilization of the ileostomy (Edwards 2001; Williams 1986). The follow‐up of the patients after stoma closure varied among the included trial and must be taking into account when analysing this outcome. Except for one of the trials (Khoury 1986), the others reported follow‐up in various lenght: 1 year (Gooszen 1998), 2,5 years (Williams 1986) and 5 years (Edwards 2001; Law 2002).

One would expect that an advantage in the ease of the closure procedures was reflected in reduction or resection the spout of the ileostomy; along with better access to the peritoneal cavity provided by the greater fascia defect in the colostomy, as reported in the trial by Edwards 2001. We agree with these considerations but the lack of statistical significance does not allow us to conclude anything about superiority of a fecal diversion method over the other.

The presence of a loop ileostomy may increase the chance of twisting the small bowel and the formation of adhesions adjacent to the stoma, which may induce postoperative intestinal obstruction (Metcalf 1986). This review did not show significant difference between the incidence of intestinal obstruction in patients with loop ileostomy and loop colostomy. However, several trials have reported that loop ileostomy is highly associated with this postoperative complication (Feinberg 1987; François 1989; Law 2002; Mann 1991; Metcalf 1986; Phang 1999). Concerning postoperative bowel obstruction there are some evidences that with longer follow‐up adhesion‐related complications might become more frequent, particularly after loop ileostomy closure (Edwards 2001). We also are in according to these reports but further studies have to be done in order to clarify this issue in terms of statistical evidence. The sample size achieved in this review was not great enough to show significant difference between the two methods of diverting the fecal stream for lack of statistical power. Further studies are required to confirm these idea.

D ‐ Functioning stoma outcomes measures: In terms of stoma management there are some evidence, which shows that ileostomy has some theoretical advantages when compared to colostomy. Thus the ileostomy spout makes the collection of the effluent more efficient, induces longer interval of time between changes of appliance, less patients complains of odour and the ileostomy site is more visible for the patient (Williams 1986). However these advantages could not be proven in this review due to most of the studies did not evaluate these variables. The patient adaptation and reduction in serious skin problems may be due to a skilled and intensive stoma care (Khoury 1986), by stoma therapists and specialised nurses in the nursing units.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS:

The results of this review lead us to conclude that loop colostomy has been shown to be a major source of postoperative complications, when stoma prolapse is taken into consideration. If we have the idea that the presence of the stoma is a temporary condition, and the prolapse will be resolved as soon as the stoma will be closure, this complication alone can not influence the choice of the best form for decompression of the colorectal anastomosis.

The lower wound sepsis rate following ileostomy closure, could be related to the fact that anaerobic bacterial counts from ileostomy fluid is less than 1% compared to normal feces, whereas the bacteriology of colostomy effluent is very similar to that of normal feces (Gorbach 1969; Hill 1976).

The overall number of stoma related complications, as outlined in the protocol (Matos 2004), could not be calculated. The information was unclear in the most of the included studies (Edwards 2001; Gooszen 1998; Khoury 1986; Law 2002) and not described in one of them (Williams 1986). The reviews made a draft of these numbers but the result did not show statistical significance even the categories that included stoma prolapse.

A recent review by Lertsithichai et al. (Lertsithichai 2004) described the same studies, but with a slightly different outcome compared to this review. Main difference is that Lertsithichai retrieved the trials from MEDLINE and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and did not include searches from LILACS and EMBASE. Both reviews found pronounced heterogeneity between the included trials. The review by Lertsithichai did not find "superiority of one temporary diverting stoma over another for all colorectal patients".

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

From the current data included in this review, it is not possible to express a preference for use of either loop ileostomy or loop colostomy for fecal diversion from a colorectal anastomosis.

Implications for research.

New randomised controlled trials of good quality are necessary to evaluate the optimal temporary defunctioning stoma. It needs to be established why colostomy have more prolapse and what procedure modifications might lessen this risk. Future randomised controlled trials should address the following aspects:

To compare safety and effectiveness of loop transverse stoma and loop ileostomy for temporary decompression of colorectal and coloanal anastomosis, analyses must focus on: 1. The primary surgery witch the stoma is constructed; 2. The interval between the construction and the closure, with problems and complications; 3. The second operation in which the stoma is closed.

Ideally trials in which patients are undergoing anterior resection and total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. For this clinical question trials should exclude patients with proximal rectal cancer in whom the mesorectal was transected and a higher rectal anastomosis was constructed.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 August 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2004 Review first published: Issue 1, 2007

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 22 September 2006 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Prof. Dr. Alvaro N Atallah, director of UNIFESP ‐ Escola Paulista de Medicina Cochrane Collaboration Unit, for technical support of this review. Furthermore, the Editorial Board and Henning Keinke Andersen from the Cochrane Colorectal Cancer Group for careful evaluation, valuable comments, and for the lingvistic revision of the manuscript.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. ILEOSTOMY VS. COLOSTOMY.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Mortality | 5 | 319 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.02 [‐0.02, 0.05] |

| 2 Wound infection | 5 | 305 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.31, 1.07] |

| 3 Stoma prolapse | 4 | 256 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.17 [‐0.24, ‐0.10] |

| 4 Stoma retraction | 3 | 211 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.03 [‐0.02, 0.08] |

| 5 Paraostomal hernia | 3 | 220 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.01 [‐0.04, 0.06] |

| 6 Paraostomal fistula | 2 | 131 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.12, 4.17] |

| 7 Skin irritation | 4 | 247 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.38, 1.12] |

| 8 Ileus | 2 | 101 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.04 [‐0.04, 0.13] |

| 9 Bowel leakage | 4 | 258 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.02 [‐0.03, 0.06] |

| 10 Reoperation | 2 | 118 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.01 [‐0.06, 0.09] |

| 11 Patient adaptation | 3 | 167 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.66, 1.25] |

| 11.1 Leakage from appliance | 3 | 167 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.66, 1.25] |

| 12 Colorectal anastomotic dehiscence | 4 | 250 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.36, 1.47] |

| 13 Incisional hernia | 2 | 103 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.07 [‐0.26, 0.11] |

| 14 Postoperative bowel obstruction | 4 | 237 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.01 [‐0.05, 0.07] |

| 15 Sensitivy analysis ‐ Studies including emergencies excluded ‐ Stoma prolapse | 3 | 186 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.08 [‐0.15, ‐0.02] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ILEOSTOMY VS. COLOSTOMY, Outcome 1 Mortality.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ILEOSTOMY VS. COLOSTOMY, Outcome 2 Wound infection.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ILEOSTOMY VS. COLOSTOMY, Outcome 3 Stoma prolapse.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ILEOSTOMY VS. COLOSTOMY, Outcome 4 Stoma retraction.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ILEOSTOMY VS. COLOSTOMY, Outcome 5 Paraostomal hernia.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ILEOSTOMY VS. COLOSTOMY, Outcome 6 Paraostomal fistula.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ILEOSTOMY VS. COLOSTOMY, Outcome 7 Skin irritation.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ILEOSTOMY VS. COLOSTOMY, Outcome 8 Ileus.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ILEOSTOMY VS. COLOSTOMY, Outcome 9 Bowel leakage.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ILEOSTOMY VS. COLOSTOMY, Outcome 10 Reoperation.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ILEOSTOMY VS. COLOSTOMY, Outcome 11 Patient adaptation.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ILEOSTOMY VS. COLOSTOMY, Outcome 12 Colorectal anastomotic dehiscence.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ILEOSTOMY VS. COLOSTOMY, Outcome 13 Incisional hernia.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ILEOSTOMY VS. COLOSTOMY, Outcome 14 Postoperative bowel obstruction.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 ILEOSTOMY VS. COLOSTOMY, Outcome 15 Sensitivy analysis ‐ Studies including emergencies excluded ‐ Stoma prolapse.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Edwards 2001.

| Methods | Randomization: no details. Allocation: after the anastomosis was completed and a decision to create a defunctiong stoma made. Withdrawal/dropouts: 2 conversion to end‐colostomy. Follow‐up after closed: 36 (6‐48) months. | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: patients undergoing anterior resection and total mesorectal excision. Exclusion criteria: previous colonic resection. Diseases: rectal cancer. Number: 70 (49 male, 21 female) ‐ Stoma closure: 63. Age: 68 (32‐90 years). | |

| Interventions | Group A (Loop ileostomy): n=34; Group B (Transverse Loop colostomy): n=36. | |

| Outcomes | Mortality: A=0, B=0. Wound infection: A=1, B=2. Time of formation of stoma: A=15 (10‐30), B=16 (5‐30). Time of closure of stoma: 48 (40‐105), B=48 (25‐90). Time interval between formation and closure of stoma: A=62 (17‐120), B=73 (28‐141). Stoma prolapse: A=0, B=2. Paraostomal hernia: A=0, B=2. Ileous: A=2, B=2. Bowel leakage: A=0, B=1. Length of hospital stay: A=6 (4‐13), B=6 (4‐9). Colorectal anastomotic dehiscence: A=2, B=1. Bowel resection: A=6, B=2. Time to first flatus (days): A=2 (1‐5), B=2 (1‐5). Time to first defaecation (days): A=3 (1‐6), B=4 (1‐6). Faecal fistula: A=0, B=1. Incisional hernia: A=0, B=5. High‐output stoma: A=1, B=0. Small bowel obstruction: A=0, B=1. | |

| Notes | Only neoplasms. Incisional hernia was an important outcome. 5 Deaths: 2 myocardial infarction, 1 metastatic disease‐advanced, 1 mesenteric ischaemie, 1 following a stroke. Data are expressed as median (range) and were compared using analysis of variance or x2 test with Yates' correction. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Gooszen 1998.

| Methods | Randomization: no details. Allocation: not related. Withdrawal/Dropouts: no patient was lost to follow‐up. Follow‐up: 1 year after stoma closure. | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: patients undergoing colorectal surgery and construction of a loop ileostomy or loop colostomy and a planned elective stoma closure operation. Diseases: malignacy of the left‐sided colon and rectum; complicatd diverticular disease; colorectal perforation; faecal incontinence; peritoneal abscess. Number: 76 (27 male, 58 female); stoma closure: 61. Age: 63.2 (26‐86 years). | |

| Interventions | Group A (Loop ileostomy): n=37; Group B (Loop Colostomy): n=39. Closure of stoma: A=29; B=32. | |

| Outcomes | Mortality: A=1, B=0. Wound infection: A=2, B=1. Stoma prolapse: A=1, B=16. Stoma retraction: A=4, B=1. Parostomal hernia: A=2, B=0. Parostomal fistula: A=1, B=2. Stenosis: A=0, B=1. Necrosis: A=0, B=1. Skin irritation: A=3, B=9. Ileous: A=2, B=1. Bowel leakage: A=3, B=1. Patient adaptation: 1.Adaptation of clothes: A=8, B=22; 2.Dietary measures: A=23, B=4; 3.Leakage: A=12, B=18. | |

| Notes | 34 emergencies: A=16, B=18. 42 electives: A=21, B=21. Total deaths: 13 (A=8, B=5). All of these patients needed one or more surgical reinterventions. To test for differences between the two groups x2 test t test and Mann‐Whitney U test . | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Khoury 1986.

| Methods | Randomization: table of random numbers. No more details about the other aspects. | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: patients with stoma at the time of colorectal anastomosis if two or more of the following indications were present: poor bowel preparation, colonic obstruction, severe cardiovascular disease, extensive local malignancy, technical problems with the anastomosis. The exclusion criteria was not related. Diseases: carcinoma of the rectum and sigmoide, diverticular disease. Number: 61 (36 male; 25 female). Age: 65 (44 ‐ 86 years). | |

| Interventions | Group A: (Loop Ileostomy) n = 32 Group B: (Transverse Loop Colostomy) n = 29. | |

| Outcomes | Wound infection: A=3, B=2. Time of closure of stoma: A=60 (30‐120), 60 (30‐90). Stoma prolapse: A=0, B=0. Stoma retraction: A=0, B=0. Paraostomal fistula: A=1, B=1. Skin irritation: A=2, B=1. Bowel leakage: A=1, B=1. Length of hospital stay ‐ total: A=29.5 (21‐55), 34 (20‐116). Colorectal anastomosis dehiscence: A=2, B=6. Patient adaptation: 1.Disconfort on change of appliance: A=4, B=2; 2.Number of the bags: A=4, B=3; 3.Leaks from the appliance: A=65%, B=60%. Intestinal obstruction: A=2, B=3. Wound dehiscence: A=0, B=2. Days of first stoma action: A=2 (1‐7), B=4.5 (1‐10). | |

| Notes | Included patients submitted emergence surgeries. Stomas were closed as soon as the patients have recovered from the primary operation. 2 deaths: not attributable to the stoma procedure. Non‐parametric statistical methods (Mann‐Whitney test). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Law 2002.

| Methods | Randomization: no details. Allocation: when the anastomosis was completed. Withdrawal/dropout:: 3 patients preferred not to have the stoma closed. Follow‐up: part of the prospective database of patients with rectal cancer. Sample size calculation: Small bowel obstruction: to reduce the obstruction rate by 15% (to achieve a type I error of 0.05 with a power of 0.8) + assumed that 10% of the patients would not undergo stoma closure = 80 patients. | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: patients underwent low anterior resection for rectal cancer within 12 cm from the anal verge. Exclusion criteria: patients with proximal rectal cancer in whon the mesorectal was transected and a higher rectal anastomosis constructed (more than 5 cm from anal verge). Diseases: rectal cancer. Number: 80 (49 male; 31 female). Stoma closure: n = 73. Age: 66.5 (38‐87 years). | |

| Interventions | Group A (Loop ileostomy): n = 42; Group B (Loop transverse colostomy): n = 38. Closure of stoma: A = 35; B = 38. | |

| Outcomes | Mortality: A=2, B=0. Wound infection: A=1, B=2. Time of closure of stoma: A=61, B=51. Time interval between formation and closure of stoma: A=183, B=180. Stoma prolapse: A=0, B=3. Stoma retraction: A=0, B=0. Paraostomal hernia: A=1, B=0. Skin irritation: A=4, B=7. Ileous: A=4, B=1. Bowel leakage: A=1, B=0. Reoperation: A=1, B=0 ‐ Stoma closure: A=1, B=0. Length of hospital stay: A=9, B=9 ‐ Stoma closure: A=5, B=6. Colorectal anastomotic dehiscence: A=2, B=2. Intestinal obstruction: A=3, B=0 ‐ Stoma closure: A=3, B=1. Incomplete diversion: A=0, B=1. Hogh output: A=1, B=0. | |

| Notes | Only neoplasms. The principal outcome: intestinal obstruction. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Williams 1986.

| Methods | Randomization: no details. Allocation: when the decision to defunction was made. Withdrawal/dropouts: 7 deaths (3 LI, 4 LTC); 4 (3 LI, 1 LTC) had their stoma closed early . | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: patients underwent elective colorectal surgery who were likely to need a defuntioning stoma. Diseases: neoplasm, diverticular disease, others. Number: 47 (23 male; 24 female). Age: 67 (28 ‐ 87 years). | |

| Interventions | Group A (Loop Ileostomy): n = 23 Group B (Transverse Loop Colostomy): n = 24 | |

| Outcomes | Wound infection: A=5 (20), 8 (18); after closure: A=0 (20), B=6 (20). Time to formation of stoma (min): A=15.2 (5‐75), B=20.3 (5‐30). Time of closure of stoma (min): A=45 (35‐60), B=45 (15‐75). Time interval between formation and closure of stomas (weeks): A=11 (4‐24), 12.5 (7‐32). Stoma prolapse: A=1 (17), B=4 (19). Skin irritation: A=7 (17), B=9 (19). Reoperation: A=0 (18), 1 (20). Length of hospital stay ‐ closure of stoma: A=9 (5‐26), B=10 (5‐14). Colorectal anastomotic dhiscence: A= 5 (19), B=6 (20). Intestinal obstruction: A=2, B=2. | |

| Notes | Method of closure; ‐ Resection + end‐to‐end anastomosis: A=17 (20), B=7 (20) ‐ Suture of anterior wall: A=3 (20), B=13 (20). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Fasth 1980 | Consecutive series of patients. The study evaluated the complication rate on construction and closure, and the difficulties associated with stoma care. Favorable to ileostomy. |

| Göhring 1988 | Not randomised. Complications: 22.5% of the ileostomies; 5.6% of the colostomies (closure of the stomas) Favorable to colostomy. |

| Lassalle 1990 | Not randomized. Ileostomy group: shorter duration of postoperative hospital stay, an earlier restoration of bowel transit, lower incidence of wound infections and incisional hernias, frequency of appliance change, easier to construct and take down. Favorable to ileostomy. |

| Popovic 2001 | Not randomised. Complications: 16% in the ileostomy group; 6.8% in the colostomy group. The authors recommended covering colostomy. |

| Rutegard 1987 | Not randomised. The trial reported and compared the results of the two different types of diverting stomas, closure rate and complications. |

Contributions of authors

DM, SASL DM, SASL DM, SSS HS, DM DM, SASL, KFG DM, SASL, KFG DM, SSS, KFG DM, SSS, KFG DM, SSS, KFG DM, SSS, KFG None None Not applicable KFG, DM DM, SSS, KFG, HS HS, DM DM, SSS, KFG DM, SSS, KFG DM, SSS, KFG DM, SSS, KFG DM, SSS None Not applicable

Declarations of interest

None known.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Edwards 2001 {published data only}

- Edwards DP, Leppintgton‐Clarke A, Sexton R, Heald RJ, Moran BJ. Stoma‐related complications are more frequent after transverse colostomy than loop ileostomy: a prospective randomized clinical trial. Br J Surg 2001;88:360‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gooszen 1998 {published data only}

- Gooszen AW, Geelkerken RH, Hermans J, Lagaay MB, Gooszen HG. Temporary decompression after colorectal surgery: randomized comparison of loop ileostomy and loop colostomy. Br J Surg 1998;85:76‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Khoury 1986 {published data only}

- Khoury GA, Lewis MC, Meleagros L, Lewis AA. Colostomy or ileostomy after colorectal anastomosis?: a randomised trial. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1986;69:5‐7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Law 2002 {published data only}

- Law WL, Chu KW, Choi K. Randomized clinical trial comparing loop ileostomy and loop transverse colostomy for faecal diversion following total mesorectal excision. Br J Surg 2002;89:704‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Williams 1986 {published data only}

- Williams NS, Nasmyth DG, Jones D, Smith AH. Defunctioning stomas: a prospective controlled trial comparing loop ileostomy with loop transverse colostomy.. Br J Surg 1986;73:566‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Fasth 1980 {published data only}

- Fasth S, Hultén L, Palselius I. Loop ileostomy ‐ an attractive alternative to a temporary transverse colostomy. Acta Chir Scand 1980;146:203‐207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Göhring 1988 {published data only}

- Göhring U, Lehner B, Schlag P. Ileostomy versus colostomy as temporary deviation stoma in relation to stoma closure. Chirurg 1988;59(12):842‐844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lassalle 1990 {published data only}

- Lassalle FAB, Benati M, Quintana GO, Moscone CJ. Loop ileostomy as alternative to transverse colostomy to protect distal anastomosis. Rev Argent Cirurg 1990;58:160‐164. [Google Scholar]

Popovic 2001 {published data only}

- Popovic M, Petrovic M, Matic S, Milovanovic A. Protective colostomy or ileostomy?. Acta Chir Iugosl 2001;48(3):39‐42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rutegard 1987 {published data only}

- Rutergard J, Dahlgren S. Transverse colostomy or loop ileostomy as diverting stoma in colorectal surgery. Acta Chir Scand 1987;153:229‐232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Alberts 2003

- Alberts JC, Parvaiz A, Moran BJ. Predicting risk and diminishing the consequences of anastomotic dehiscence following rectal resection. Colorectal Dis 2003;5(5):478‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dehni 1998

- Dehni N, Schlegel RD, Cunningham C, Guiguet M, Tiret E, Parc R. Influence of a defunctioning stoma on leakage rates after low colorectal anastomosis and colonic J pouch‐anal anastomosis. Br J Surg 1998;85:1114‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dickersin 1994

- Dickersin K, Scherer R, Lefebvre C. Identifying relevant studies for systematic reviews. BMJ 1994;309(6964):1286‐91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Feinberg 1987

- Feinberg SM, McLeod RS, Cohen Z. Complications of loop ileostomy. Am J Surg 1987;153:102‐107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

François 1989

- François Y, Dozois RR, Kelly KA, Beart RW, Wolff BG, Pemberton JH. Small intestinal obstruction complicating ileal pouch‐anal anastomosis. Ann Surg 1989;209:46‐50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gastinger 2005

- Gastinger I, Marusch F, Steinert R, Wolff S, et al. Protective defunctioning stoma in low anterior resection for rectal carcinoma. British Journal of Surgery 2005;92:1137‐1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gooszen 2000

- Gooszen AW, Geelkerken RH, Hermans J, Lagaay MB, Gooszen HG. Quality of life with a temporary stoma. Ileostomy vs. colostomy. Dis Colon Rectum 2000;43:650‐655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gorbach 1969

- Gorbach SL, Tabaqchali S. Bacteria, bile and the small bowel. Gut 1969;10:693‐972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Guenaga 2003

- Guenaga KF, Matos D, Castro AA, Atallah AN, Wille‐Jorgensen P. Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2003, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001544.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hawley 1979

- Hawley PR, Ritchie JK. The colon. Clin Gastroenterol 1979;8(2):403‐14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hill 1976

- Hill GL. Ileostomy: surgery, physiology and management. New York: Grune & Straton, 1976. [Google Scholar]

Hool 1998

- Hool GR, Church JM, Fazio VW. Decision‐Making in Rectal Cancer Surgery. Disease of Colon an Rectum 1998;41:147‐152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Konishi 2006

- Konishi T, Watanabe T, Kishimoto J, Nagawa H. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after surgery for colorectal cancer: results of prospective surveillance. J Am Coll Surg 2006;202(3):439‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lertsithichai 2004

- Lertsithichai P, Rattanapichart P. Temporary ileostomy vesus temporary colostomy: a meta‐analysis of complications. Asian Journal of Surgery 2004;27(3):202‐210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lewis 1982

- Lewis A, Weeden D. Early closure of transverse loop colostomy. Ann R Surg Engl 1982;64:57‐58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lustosa 2001

- Lustosa SA, Matos D, Atallah AN, Castro AA. Stapled versus handsewn methods for colorectal anastomosis surgery. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2001, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003144] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Makela 2003

- Makela JT, Kiviniemi H, Laitinen S. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after left‐sided colorectal resection with rectal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum 2003;46:653‐660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mann 1991

- Mann LJ, Stewart PJ, Goodwin RJ, Chapuis PH, Bokey EL. Complications following closure of loop ileostomy. Aust N Z J Surg 1991;61:493‐496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Matos 2004

- Matos D, Lustosa SAS. Ileostomy or colostomy for temporary decompression of colorectal anastomosis. Cochrane Database Sys Rev 2004, issue 1. [CD004647] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

McArdle 2005

- McArdle CS, McMillan DC, Hole DJ. Impact of anastomotic leakage on long‐term survival of patients undergoing curative resection for colorectal surgery. Br J Surg 2005;92(9):1150‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Metcalf 1986

- Metcalf AM, Dozois RR, Beart RW, Kelly KA, Wolff BG. Temporary ileostomy for ileal pouch anastomosis. Function and complications. Dis Colon Rectum 1986;29:300‐303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

O' Leary 2001

- O' Leary DP, Fide CJ, Foy C, Lucarotti ME. Quality of life after low anterior resection with total mesorectal excision and temporary loop ileostomy for rectal carcinoma. Br J Surg 2001;88:1216‐1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Peeters 2005

- Peeters KCMJ, Tollenaar RAEM, Marijnen CAM, Kranenbarg EK, et al. Risk factores for anastomotic failure after total mesorectal excision of rectal cancer. Br J Surg 2005;92:211‐216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Phang 1999

- Phang PT, Hain JM, Perez‐Ramirez JJ, Madoff RD, Gemlo BT. Techniques and complications of ileostomy takedown. Am J Surg 1999;177:463‐466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Poon 1999

- Poon RTP, Chu KW, Ho JWC, Chan CW, Law WL, Wong J. Prospective evaluation of selective defunctioning stoma for low anterior resection with total mesorectal excision. World J Surg 1999;23:463‐468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rullier 1998

- Rullier E, Laurent C, Garrelon JL, Michel P, Saric J, Parneix M. . Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after resection of rectal cancer.. Br J Surg 1998;85:355‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Silva 2003

- Silva MA, Ratnayake G, Deen KI. Quality of life of stoma patients: temporary ileostomy versus colostomy. World J Surg 2003;27(4):421‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Torkington 1998

- Torkington J, Khetan N, Jamison MH. Letter: temporary decompression after colorectal surgery: randomized comparison of loop ileostomy and loop colostomy.. Br J Surg 1998; Vol. 85:1450‐2. [PubMed]

Wexner 1993

- Wexner SD, Taranow DA, Johansen OB, et al. Loop ileostomy is a safe option for fecal diversion. Dis Colon Rectum 1993;36:349‐354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]