ABSTRACT

Objective

Fatigue is a common symptom in somatic and mental illness. Musculoskeletal pain and psychological distress have in turn frequently been shown to be associated with fatigue across clinical conditions and in the general population. The study aims to disentangle direct effects from those due to mere confounding from shared etiologies.

Design

The study used genetically informative longitudinal twin data, through a co-twin control design with an additional within-person dimension.

Methods

Data on fatigue, pain and distress from 2196 mono – and dizygotic twins from the Norwegian Twin Registry examined at two time points five years apart was analyzed using multilevel generalized linear regression modeling. Fatigue was regressed on pain and distress, with further controls added for confounding from genetic and stable non-shared environmental sources.

Results

Pain and distress had a significant impact on fatigue at genetic, stable non-shared environmental and time-varying levels, even when controlling for somatic comorbidity.

Conclusion

The findings indicate that a significant proportion of the association between fatigue, pain and distress is due to genetic and environmental confounding. Pain and distress exert significant, albeit smaller effects on fatigue even when controlling for genetic and stable environmental contributions, indicating direct effects. Potential etiological pathways and underlying mechanisms are discussed.

KEYWORDS: Fatigue, pain, psychological distress, behavioral genetics

The experience of fatigue involves strong sensations of mental and physical tiredness, weakness, exhaustion, and difficulty with concentration. One definition conceptualizes fatigue as an awareness of a decreased capacity for physical or mental activity due to an imbalance in the availability, utilization or restoration of resources needed to perform an activity (Aaronson et al., 1999). Life stressors and homeostatic factors (i.e. overexertion) may contribute to acute fatigue in otherwise healthy individuals (Finsterer & Mahjoub, 2014). For some, however, the symptom may linger and take on a persistent, chronic form (Duncan, Wu, & Mead, 2012; Mollayeva et al., 2014), which is the case in, e.g. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) (also denoted Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME)) (Cortes Rivera, Mastronardi, Silva-Aldana, Arcos-Burgos, & Lidbury, 2019). Fatigue is frequently reported in general primary care and community studies, and the exact threshold between common fatigue (e.g. ‘feeling tired and weak’) and diagnosable CFS can be arbitrary. Fatigue is therefore presumably best conceptualized as a continuously distributed symptom in the general population (Bültmann, Kant, Kasl, Beurskens, & van den Brandt, 2002; Loge, Ekeberg, & Kaasa, 1998).

While the exact pathogenesis of acute and chronic fatigue conditions remains unexplained, several biomedical, psychological, and social risk factors are associated with fatigue onset and maintenance (Cortes Rivera et al., 2019; Penner & Paul, 2017). Associations have, e.g. previously been established with symptoms of depression and anxiety (Bültmann et al., 2002; Hickie, Bennett, Lloyd, Heath, & Martin, 1999; Vassend, Røysamb, Nielsen, & Czajkowski, 2018), pain (Reyes-Gibby, Mendoza, Wang, Anderson, & Cleeland, 2003; Vassend et al., 2018), inflammatory processes (Matura, Malone, Jaime-Lara, & Riegel, 2018; Patejdl, Penner, Noack, & Zettl, 2016), metabolic dysfunction (Freidin et al., 2018; Manjaly et al., 2019) and personality (Henderson & Tannock, 2004; Nater et al., 2010; Poeschla, Strachan, Dansie, Buchwald, & Afari, 2013; Vassend et al., 2018). However, biomedical markers and processes such as viral infection, mitochondrial or metabolic dysfunction, and fatigue-related cytokines are only weakly related (or unrelated) to subjective symptom levels, and studies have often been inconclusive when appropriate controls were included (Kristiansen et al., 2019). While disease-specific processes might contribute to fatigue, there are strong indications of the existence of transdiagnostic mechanisms which may overlap in their associations with fatigue across disorders (Menting et al., 2018).

Musculoskeletal pain is one subjective complaint most commonly co-occurring with fatigue in both clinical and non-clinical populations (Van Damme, Becker, & Van der Linden, 2018). One study conducted in a large community sample revealed that as many as 60% of those who reported chronic widespread pain, also reported persistent fatigue (Creavin, Dunn, Mallen, Nijrolder, & van der Windt, 2010). Furthermore, psychological distress (i.e. symptoms of depression and anxiety) has been established as a significant risk factor for fatigue in both medical disorders and the general population (Bower, 2014; Corfield, Martin, & Nyholt, 2016a; Lamers, Hickie, & Merikangas, 2013; Menting et al., 2018; Ormstad & Eilertsen, 2015; Penner & Paul, 2017; Schreiber, Lang, Kiltz, & Lang, 2015).

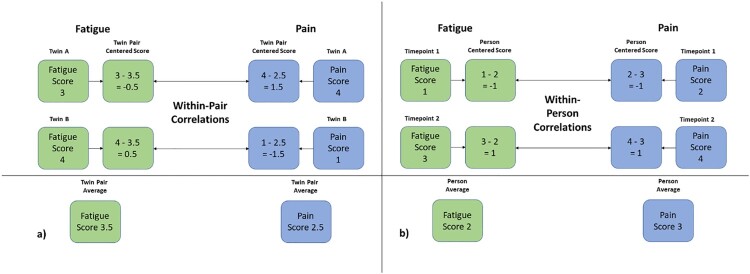

While associative studies allow for the examination of covariation between fatigue, pain and psychological distress, causality or direct effects can rarely be inferred from conventional observational research, due to potential unmeasured confounding factors and lack of experimental control. Shared genetic etiology between phenotypes, also known as pleiotropy, is one such potential confounder in observational studies (McAdams, Rijsdijk, Zavos, & Pingault, 2020). The relatively few published twin studies of the genetic susceptibility for fatigue, based on both continuous and dichotomous (CFS/CFS-like) phenotype definitions, have generally found best fit for models incorporating additive genetic and non-shared environmental effects, with heritability estimates between 0.30 and 0.53, indicating moderate genetic and non-shared environmental effects underlying fatigue (Corfield, Martin, & Nyholt, 2017; Hickie, Kirk, & Martin, 1999; Sullivan, Evengård, Jacks, & Pedersen, 2005; Vassend et al., 2018). A twin study conducted with data from a Sri Lankan twin sample provides incremental support for the generalizability of the heritability of fatigue also within a non-western culture (Ball et al., 2010), as heritability estimates of 30% were found for continuous fatigue severity, and 39% for severe, abnormal fatigue in their best-fitting models including only additive genetic and non-shared environmental effects . Interestingly, Ball et al. (2010) investigated specific life exposures which might underlie environmental influences on fatigue, and found that leaving school early, poor standards of living, negative life events and poor parental care mediated fatigue through non-shared, but primarily shared environmental influences. Thus, while the shared environment generally does not explain a significant proportion of phenotype fatigue, there might exist some slight cultural variations. Furthermore, previous studies have revealed a considerable overlap in genetic and non-shared environmental dispositions for pain and fatigue (Hickie et al., 1999; Vassend et al., 2018), and likewise between fatigue and psychological distress (Ball et al., 2010; Corfield, Martin, & Nyholt, 2016b; Vassend et al., 2018). Pain and psychological distress thus seem to be interrelated with fatigue at both a phenotypic, genetic and environmental level, yet the causal nature of these relationships remain largely unknown. Twin studies allow for some control over genetic contributions to phenotypic associations, through the use of a genetically matched co-twin control condition (McGue, Osler, & Christensen, 2010), with the ability to measure within-pair effects of predictors when genetic and shared environmental factors are held constant. In twin studies, this can be evaluated by centering each twin's phenotype scores (e.g. pain and fatigue) around a twin pair average, and test for correlations between the centered scores. See Figure 1(a) for a simplified illustration of this process. As noted above, pain and distress are correlated with fatigue in the population. Should, however, the within-pair correlation in monozygotic twins be zero, this would indicate complete genetic confounding, because there would be no residual correlation when the effects of genes have been controlled for. Specifically, this would mean that there would be no pattern indicating that the twin with higher levels of pain and distress also tends to report higher levels of fatigue, given their completely shared genetic makeup. If, however, there is a within-pair tendency for a correlation between these symptoms within the monozygotic twin pair, this would indicate either direct effects, or effects attributable to some confounding from the non-shared environment (McGue et al., 2010).

Figure 1.

(a & b). A visual illustration of the co-twin and within-person procedures. The demonstrated procedures are simplified for ease of comprehension, and we refer to the Supplemental data for a review of the specific centering techniques applied in our study. Figure 1(a) demonstrates how within-pair correlations are calculated, by subtracting the twin pair average phenotype scores from the score of each twin. The resulting centered score provides a measure of each twin's distance from the twin pair average, which is then free from genetic influences. Likewise, Figure 1(b) demonstrates the application of the same procedure to two measurement timepoints within one individual. The within-person correlations are calculated by subtracting the person average phenotype scores from the phenotype scores at each timepoint. The resulting person centered scores provides a measure of each timepoint's distance from the person average, which is then free from influences from the stable non-shared environment.

While twin studies do allow for control over genetic confounding and environment shared by siblings, they still cannot account for potential confounding from the non-shared environment. Life experiences, educational attainment, spousal influences, somatic illness, and stochastic biological processes unique to the individual's life course may be common causal factors underlying associations. Such individual-specific events and processes pose as major causal and confounding factors in epidemiology and behavioral genetics (Smith, 2011; Tikhodeyev & Shcherbakova, 2019). Smith (2011) emphasized confounding from the non-shared environment, such as gene-by-environment interactions and stochastic events ranging across the sub-cellular and cellular levels, as particularly problematic in epidemiology and behavioral genetics, in that they are generally neither epidemiologically tractable nor available for intervention.

One way of dealing with the problem of the non-shared environment, is to consider that it has both stable and time-varying components. When examining adults who have lived long lives full of unique experiences, it is difficult to measure all specific life events and stochastic biological processes that have occurred throughout their lives unique to them. Indeed, as Tikhodeyev and Shcherbakova (2019) emphasize, attempts at identifying the specific contents of the non-shared environment have been futile. One conceptual way to capture the effects of the unique life experiences thus far, is to introduce a longitudinal element to co-twin models, and use the stability within individuals to capture stability in phenotypes not otherwise explained by genetic factors. By applying the same procedure as that applied within co-twin studies describes above, but instead using each person as their own control, within-person correlation can be calculated to evaluate if there remains a residual effect across time within individuals. See Figure 1(b) for a simplified visual presentation of this procedure. If pain and distress are correlated with fatigue within twin pairs, but the within-person correlation across time is zero, this would indicate additional confounding from stable environmental influences not shared between twins, but exerting equal influences on all within-person measurements. Specifically, this would be the case if there was no pattern indicating that the timepoint with higher levels of pain and distress also coincides with the timepoint with higher levels of fatigue. If, however, there remains a significant within-person correlation across time, this would indicate direct associations free from genetic and stable non-shared environmental contributions.

Such dispositional stability within individuals could thus be conceptually construed as caused by factors in the stable non-shared environment, containing the effects of all the unique life events experienced by the individual prior to our measurements. Genetically informative longitudinal research is one way of examining the underlying genetic, stable and time-varying architecture of risk factors and their potentially causal relationships to fatigue symptoms. Ascertaining whether fatigue is causally linked with psychological distress and pain over time, or merely associated through genetic and environmental confounding, is essential to our understanding of fatigue, and contribute to future attempts at developing etiological models.

Aims

The present study aims to examine the contribution of psychological distress and musculoskeletal pain to fatigue, controlling for genetic confounding through the utilization of a co-twin control condition. The longitudinal dimension of the data allows for additional control over stable non-shared environmental confounding through a within-person control condition. Based on previous research, we expect to find strong pleiotropic effects between fatigue and pain, as well as between fatigue and distress, indicative of shared genetic susceptibility between them. Furthermore, if there exists additional environmental factors contributing to a stable risk for fatigue and pain, and fatigue and distress, we expect to find significant effects also at the stable non-shared environmental level. Finally, if pain and distress contribute significantly to fatigue even when controlling for genetic and environmental factors shared between these constructs, we expect to find significant effects at the time-varying non-shared environmental level.

Methods

Study design

The following study employed a co-twin control design, with an additional within-person dimension through the inclusion of two time points. The standard co-twin control design is a variant of the case–control design, where each participant is matched with their own twin. The addition of the within-person dimension to the design adds another case–control condition, whereby each participant is matched with themselves across time.

Sample

The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics, South-East Norway (project 2015/958), and informed consent was obtained from all participants. Data was sampled from a subset of the Norwegian Twin Registry (Nilsen et al., 2013), collected at two time points (in 2011 and 2016). To be included in our study, one of the twins had to have responded to the questionnaires regarding both fatigue, pain and distress on at least one occasion. Zygosity was determined by response to a questionnaire item at earlier timepoints, which has previously been shown to identify approximately 98% correctly as either di – or monozygotic (Magnus, Berg, & Nance, 1983). The age range of the cohort was between 50–65 at the first measurement point, with a mean age of 57.1 (SD = 4.5). The sample consisted of 40.7% male and 59.3% female same-sex twin pairs. The sample included 2196 participants belonging to 609 monozygotic (Mz) and 759 dizygotic (Dz) twin pairs. For a complete overview of responders sorted by their own and their co-twin's contribution to the study, see Table 1.

Table 1.

The distribution of responders organized by their own contribution to the study as well as their co-twins’, separated by zygosity.

| Single responder, single occasion | Single responder, both occasions | One occasion with one co-twin occasion | One occasion with two co-twin occasions | Two occasions with one co-twin occasion | Two occasions with two co-twin occasions | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monozygotic | 172 | 22 | 340 | 113 | 113 | 264 | 1024 (46.6%) |

| Dizygotic | 297 | 49 | 326 | 143 | 143 | 214 | 1172 (53.4%) |

| Total | 469 (21.4%) | 71 (3.2%) | 666 (30.3%) | 256 (11.7%) | 256 (11.7%) | 478 (21.8%) | 2196 (100%) |

The lowest degree of contribution to the study is represented by the leftmost column, showing participants who only responded to one occasion (either 2011 or 2016), without a co-twin observation. The highest degree of contribution to the study is represented by the rightmost column, showing participants who responded at both occasions, and whose co-twin also responded at both occasions.

Procedure

Two subscales from the self-report questionnaire Giessen Subjective Complaints List (GSCL) were used as a measure of fatigue and pain. The GSCL has been used extensively in epidemiological research, and has been validated in a Norwegian sample (Vassend, Lian, & Andersen, 1992). The fatigue subscale includes the following six items: 1. Physical weakness; 2. Excessive need for sleep; 3. Rapid exhaustion; 4. Tiredness or drowsiness; 5. Feeling distant and difficulty concentrating; 6. Feeling of listlessness. The respondents are asked to rate the degree to which they ‘generally’ suffer from the symptoms on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (strongly). The fatigue subscale demonstrated good internal consistency when measured both in 2011 (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88) and in 2016 (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90). Included in the subscale for musculoskeletal pain are the following six items: 1. Pain in joints or limbs; 2. Backache; 3. Neck and shoulder pain; 4. Headache; 5. Heaviness in legs; 6. Feeling of pressure in the head. The pain subscale also showed good internal consistency both in 2011 (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.79) and in 2016 (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.78). Psychological distress was measured using two abbreviated versions of the Symptoms Checklist (Derogatis, Lipman, Rickels, Uhlenhuth, & Covi, 1974). In 2011, a five item version (SCL-5) was used, asking the participants whether they over the last two weeks had experienced: 1. Feeling fearful; 2. Feelings of nervousness or inner turmoil; 3. Feeling hopeless about the future; 4. Feeling blue; and 5. Worrying too much about things. In 2016, the three following items were added to the scale (SCL-8): 6. Feeling that everything is an effort; 7. Feeling tense or keyed up; and 8. Feeling suddenly fearful without a reason. Each item was rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Internal consistency was deemed acceptable for both the 5-item version (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87) and the 8-item version (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90). Short versions of this questionnaire have been shown to have good psychometric properties in the general Norwegian population (Strand, Dalgard, Tambs, & Rognerud, 2003). Comorbidity indicators were generated through the summation of dichotomous responses (yes / no) to questions regarding various disease categories in 2011 (see Supplemental data for details).

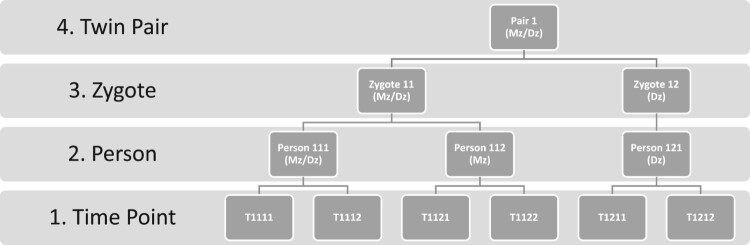

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata Statistical Package: Release 16 (StataCorp, 2019). Preliminary bivariate phenotypic correlation analyses were conducted between distress, pain and fatigue, separated by timepoints. For the multilevel generalized modeling, data was structured in a long format with hierarchical leveling of timepoints (Level 1) nested within individuals (Level 2), within zygote (Level 3), within twin pairs (Level 4). The theoretical basis for application of multilevel modeling to biometrical analyses of twin data has been previously established, and the parameterization of such an approach within a multilevel framework is described in further detail in Rabe-Hesketh, Skrondal & Gjessing (Rabe-Hesketh, Skrondal, & Gjessing, 2008). Figure 2 illustrates the hierarchical structure of the data. The multilevel approach considers that there are dependent observations in the data, and a structure inherent in the degree of dependency. Fatigue reported on two occasions (level 1) by the same individual (nested at level 2) should be more correlated than between two individual Mz-twins, and two observations in Mz-twins (nested at level 3) should correlate more than two observations in Dz-twins (nested at level 4).

Figure 2.

The hierarchical data structure to which the multilevel modeling was adapted. The numbering at the various levels indicate allocation of timepoints within persons within zygotes within twin pairs. Monozygotic (Mz) twins are nested together at both level 3 & 4, while dizygotic twins (Dz) are nested together only at level 4.

The use of multilevel generalized linear regression models using the ‘meglm’ command in Stata allows for variance compartmentalization into variance components at separate nested levels (Rabe-Hesketh & Skrondal, 2012). Variance components at level 3 and 4 were constrained to be equal, meaning that the 50% shared genes in Dz-twins must exert the same effect as the additional 50% shared genes in Mz-twins. The Supplemental data provides further details on the specific variable and model parameterization employed, along with explanations of the multilevel approach for the uninitiated. Models with an additional component for the effects of the shared environment (i.e. residual variance at the twin pair level) was estimated to evaluate the best fit of models incorporating either (1) additive genetic; or (2) additive genetic & shared environmental familial components. Aggregate variables were generated to control the time-varying effect from confounding from genetic and stable non-shared environment. Aggregate variables are essentially averaged scores within the nested level. For clarity, this means that a level 1 variable varies with each measurement point, a level 2 variable is constant within the individual (e.g. the average of reported pain across both time points), and that level 3 & 4 variables are constant within the twin pair (e.g. the average of reported pain across both time points in both twins). Cluster mean centering was performed to allow for non-dependency in the hierarchical variables (see Supplemental data for exact centering strategy). The inclusion of such aggregate variables in the fixed part of the regression model, allows us to control for and single out the confounding effects of genetics and stable non-shared environment.

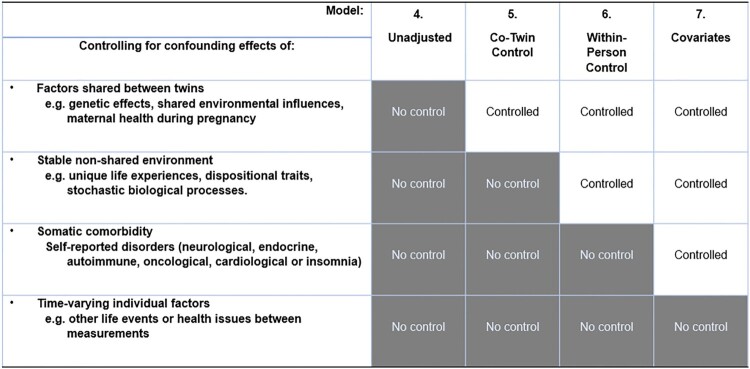

A blockwise approach was applied during the estimation of the multilevel model, beginning from a baseline model including the fixed effect of female gender (Model 1). Further modeling was performed by adding fixed effects of (2) psychological distress (Level 1); (3) musculoskeletal pain (Level 1); (4) distress and pain (Level 1); (5) aggregate variables for pain and distress at the zygote and twin pair level (3 & 4) with co-twin control constraints, with level 1 variables centered around the zygote/pair aggregate variables; (6) aggregate variable for the individual (level 2) centered around the zygote/pair aggregate variables (level 3 & 4), with level 1 variables centered around the initial aggregate variable for the individual (level 2), to control for within-person stability, and (7) comorbidity indicators as observed covariates. The rationale for the final three model adjustments is demonstrated visually in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Adjustments made in the final four models estimated, showing each incremental control condition. Model 5 adjusts the main effects with a co-twin condition, while model 6 adjusts the main effects through a within-person control condition. Model 7 includes comorbidity indicators as observed covariates, to evaluate confounding from somatic illness. While the model adjustsments allow for a comprehensive control, they do not, however, allow for the control of potential confounding by unmeasured time-varying factors such as the effects of life events in between measurements.

Missing observations at either timepoint or in a person's co-twin were modeled as missing-at-random, and the estimation was performed using full information maximum likelihood to allow for the utilization of data from participants without complete data in the likelihood estimation. Full information maximum likelihood has been shown to estimate unbiased parameter estimates and standard errors when data is missing-completely-at-random or missing-at-random (Newman, 2014).

Results

Phenotypic correlations

Bivariate correlation analyses were conducted to ascertain phenotypic correlations between the included phenotypes (see Table 2). As expected, fatigue shows a strong and significant positive association with musculoskeletal pain (r = .58 to .71 depending on time point) and psychological distress (r = .46 to .62 depending on time point). These correlations within individuals across time indicate considerable intra-individual stability in the three phenotypes across time.

Table 2.

Phenotypic correlations between included variables at both time points, T1 = 2011 and T2 = 2016.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Fatigue T1 | 1 | |||||

| 2. Fatigue T2 | .74** | 1 | ||||

| 3. Musculoskeletal Pain T1 | .69 ** | .58 ** | 1 | |||

| 4. Musculoskeletal Pain T2 | .61 ** | .71 ** | .73 ** | 1 | ||

| 5. Psychological Distress T1 | .50 ** | .46 ** | .38 ** | .39 ** | 1 | |

| 6. Psychological Distress T2 | .49 ** | .62 ** | .36 ** | .47 ** | .65 ** | 1 |

Note: Correlations marked in bold indicate within-phenotype correlation across timepoints. ** = p < .001.

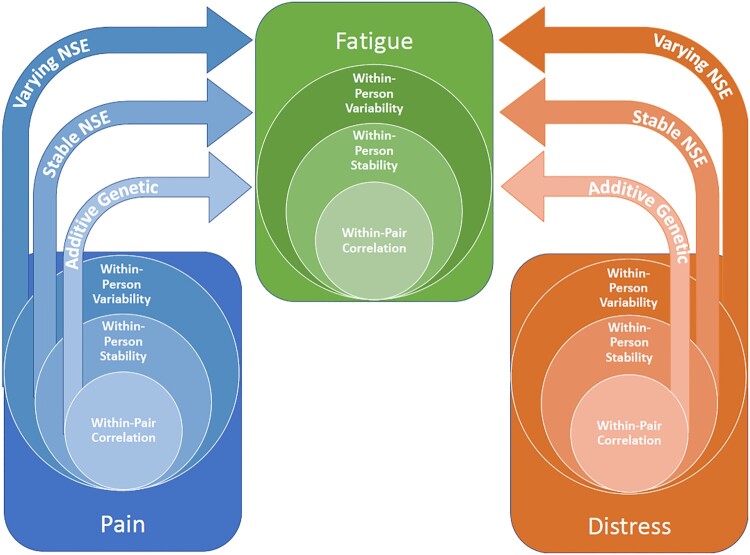

Variance component models

Multilevel variance component models with a fixed effect of female gender were constructed for all included phenotypes. Preliminary analyses confirmed best fit for models not incorporating the shared environment as an isolated component, and any potential effects of the shared environment is thus included in the additive genetic components. Due to the standardization of all variables, the variance components can be interpreted as percentages, although the inclusion of gender as a baseline covariate explains some variance in all three phenotypes, resulting in some variation in variance compositions. Table 3 lists the variance components for fatigue, pain and distress. Fatigue had a heritability (h²) of 45%. Furthermore, 22% of the variance in phenotype fatigue was attributable to stable non-shared environment. Finally, 27% of the variance was estimated as time-varying, residual variance. Female gender was significantly associated with fatigue (β = 0.17, p < 0.001). All predictor variables included show a moderate degree of heritability. Musculoskeletal pain had a heritability of 47%, while 14% of the variance was attributable to the stable non-shared environment, and 28% of the variance was estimated as time-varying, residual variance. Female gender had a significant effect on pain (β = 0.28, p < 0.001). Psychological distress was estimated with a heritability of 36%, a stable non-shared environmental component of 27%, and a time-varying, residual component of 38%. Female gender showed a significant positive association with distress (β = 0.19, p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Variance component models of all included variables, with variance compartmentalized into levels of additive genetic variance, stable non-shared environmental variance and varying non-shared environmental variance, with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

| Variance component models | Additive genetics (95% CI) | Stable non-shared environment (95% CI) | Varying non-shared environment (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | 0.45 (.39 - .53) | 0.22 (.17 - .28) | 0.27 (.25 - .30) |

| Psychological Distress | 0.36 (.29 – .44) | 0.27 (.20 - .35) | 0.38 (.35 - .42) |

| Musculoskeletal Pain | 0.47 (.41 – .54) | 0.14 (.10 - .20) | 0.28 (.26 - .31) |

Note: Due to best fit for models excluding the shared environment as a separate component, potential effects of environmental influences shared between twins are included within the additive genetic component. The additive genetic component nevertheless provides an estimate of the heritability (h²) of the constructs, while the stable non-shared environmental components provide an estimate of stability within individuals not otherwise accounted for by additive genetics. The time-varying environment component includes variance not otherwise explained, i.e fluctuations in phenotype within individuals, and measurement error.

Multilevel model fitting

Each modeling step led to an increase in model fit according to Log Likelihood in comparison to the previous one. Models 5–7 apply control conditions for confounding and lose some model fit in the process, which is to be expected given data loss when centering level 1 predictor variables. The fixed effects of musculoskeletal pain and psychological distress at all included levels across the models estimated are shown in Table 4 along with residual variance components and model fit indicators (log likelihood and Akaike Information Criterion (AIC)). A visual aid for the interpretation of the various level-specific coefficients is presented in Figure 4.

Table 4.

Fixed effects with (95% Confidence Intervals) of level-specific coefficients for psychological distress and musculoskeletal pain, and residual variance components for each incremental modeling step with percentages of explained variance.

| Fixed effects | 1. Baseline | 2. Distress | 3. MS-pain | 4. Distress & MS-Pain | 5. Co-twin control | 6. Within-person control | 7. Observed covariates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female Gender (95% CI) | 0.17 (0.08–0.26) | 0.09 (0.01–0.16) | −0.03 (−0.07–0.05) | −0.03 (−0.08–0.02) | −0.02 (−0.08–0.04) | −0.02 (−0-09 - 0.03) | −0.02 (−0.08–0.03) |

| Psychological Distress (Varying Non-Shared Environment) (95% CI) | – | 0.46 (0.43–0.49) | – | 0.28 (0.25–0.31) | 0.14 (0.11–0.18) | 0.08 (0.03–0.14) | 0.09 (0.03–0.14) |

| Psychological Distress (Additive Genetics) (95% CI) | – | – | – | – | 0.38 (0.33–0.43) | 0.39 (0.34–0.44) | 0.37 (0.32–0.42) |

| Psychological Distress (Stable Non– Shared Environment) (95% CI) | – | – | – | – | – | 0.30 (0.26–0.35) | 0.29 (0.25–0.34) |

| Musculoskeletal Pain (Varying Non– Shared Environment) (95% CI) | – | – | 0.67 (0.64–0.70) | 0.55 (0.53–0.58) | 0.28 (0.24–0.32) | 0.21 (0.15–0.27) | 0.22 (0.16–0.28) |

| Musculoskeletal Pain (Additive Genetics) (95% CI) | – | – | – | – | 0.70 (0.65–0.75) | 0.72 (0.67–0.77) | 0.67 (0.62–0.72) |

| Musculoskeletal Pain (Stable Non-Shared Environment) (95% CI) | – | – | – | – | – | 0.53 (0.48–0.59) | 0.50 (0.44–0.55) |

| Residual Variance Component (% explained variance) | |||||||

| Additive Genetics | 0.45 | 0.24 (46%) | 0.12 (74%) | 0.09 (80%) | 0.11 (75%) | 0.11 (72%) | 0.10 (75%) |

| Stable Environmental | 0.22 | 0.16 (28%) | 0.13 (40%) | 0.10 (56%) | 0.12 (47%) | 0.09 (54%) | 0.11 (58%) |

| Residual | 0.27 | 0.27 (2%) | 0.24 (13%) | 0.23 (17%) | 0.22 (19%) | 0.22 (20%) | 0.22 (20%) |

| Model Fit Indicators | Obs. 3001. df = 5 | Obs. 3001. df = 6 | Obs. 3001. df = 6 | Obs. 3001. df = 7 | Obs. 3001. df = 9 | Obs. 3001. df = 11 | Obs. 3001. df = 17 |

| Log Likelihood | −3804.03 | −3416.83 | −3029.52 | −2822.46 | −2915.14 | –2887,774 | −2823,923 |

| Akaike Information Criterion | 7618.06 | 6845.663 | 6071.042 | 5658.915 | 5848.283 | 5797.547 | 5681.847 |

Note: Each modeling step from 1–4 led to an increase in model fit (higher Log Likelihood and lower AIC) and explained variance, while models 5–7 aim primarily to add incremental control for confounders rather than increase model fit.

Figure 4.

The multilevel regression model separates the additive genetic, stable non-shared environmental (Stable NSE) and varying non-shared environmental (varying NSE) components of the included phenotypes, and provides level-specific coefficients of distress and pain on fatigue. This is estimated through genetically weighted within-pair correlation, within-person stability and within-person variability. The model is strictly illustrative, and it should be noted that other possible models of the relationships between fatigue, pain and distress cannot be eliminated based on our findings.

Firstly, model 2 includes distress as a predictor at each timepoint. Distress shows a significant effect on fatigue, and explains 46% of the additive genetic variance, 28% of the variance attributable to stable non-shared environment and 2% of the variance in varying non-shared environment. Model 3 includes solely musculoskeletal pain as a predictor at each timepoint. Pain has a strong effect on fatigue, and explains 74% of the additive genetic variance, 40% of the variance in fatigue due to stable non-shared environment, and 13% of the variance in fatigue due time-varying non-shared environment. Model 4 includes both musculoskeletal pain and distress (level 1), and in combination they explain 80% of the additive genetic variance, 56% of the variance due to stable non-shared environment, and 17% of the residual variance. The subsequent model steps are aimed at controlling the effects of pain and distress for confounding from genetic and non-shared environment. Model 5 adds a co-twin control to isolate the effects of shared genetics from the main effects. This leads to a reduction in the main effects of pain and distress, due to the compartmentalization of the main effect into genetic and time-varying effects. Model 6 finally adds a within-person control for stable non-shared environment, leading again to a decrease in the time-varying effects of distress and pain. Model 7 adds comorbidity indicators as observed covariates to control for confounding from somatic illness burden, which might underlie shared genetic variance, with resulting slight reductions in the additive genetic and stable non-shared environment effects of pain and distress. In the final adjusted model, both musculoskeletal pain and psychological distress (Level 1) show significant effects on fatigue even when controlling for confounding from shared genetic effects and stable non-shared environment, with pain showing a more robust effect than distress. The time-varying effect size of pain has been reduced from 0.55 in model 4 (controlling for distress) to 0.22 in model 7 (controlling for genetic and stable non-shared environmental confounding as well as comorbidity). Likewise, the time-varying effect size of distress has been reduced from 0.28 in model 4 (controlling for pain) to 0.09 in model 7 (controlling for genetic and dispositional confounding as well as comorbidity). For other fixed effects included in the final model, see Table 5.

Table 5.

Fixed effects for the final model with observed comorbidity covariates (Model 7), with estimated regression coefficients (β), standard errors of the estimates (S.E.) and p-values generated from Wald-tests of significance.

| Fixed effects | Psychological distress | Musculoskeletal pain | Intercept | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Varying NSE | Stable NSE | Additive Genetic | Varying NSE | Stable NSE | Additive Genetic | ||

| β | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0.37 | 0.22 | 0.49 | 0.67 | −0.05 |

| S.E. | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| p > |Z| | 0.002 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.024 |

| Comorbidity indicators | Female gender | ||||||

| Neurological | Endocrine | Autoimmune | Sleep Disorders | Cancer | Coronary | ||

| β | 0.23 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.43 | 0.27 | 0.17 | −0.03 |

| S.E. | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.03 |

| p > |Z| | < 0.001 | 0.030 | 0.008 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.064 | 0.374 |

Note: Psychological distress and musculoskeletal pain have level-specific regression coefficients for varying non-shared environment (NSE), stable NSE and additive genetics, while regression coefficients of comorbidity indicators are included as level 2 variables (i.e. stable within each individual across timepoints).

Due to the potential construct overlap between item #6 on the depression scale (feeling that everything is an effort) and fatigue, all analyses were also repeated with this item removed from the depression scale. There were minimal changes in explained variance and fixed coefficients across all modeling steps, with discrepancy of maximum 0.01 in fixed effects of distress at all levels. The item was thus retained in the reported analyses.

Discussion

Through this study, we found that pain and psychological distress are associated with fatigue due to a considerable common genetic and stable non-shared environmental susceptibility, but also through direct within-person effects across time. The findings demonstrate the considerable relevance of pain and distress for a comprehensive understanding of the fatigue phenomenon, and may inform research on etiological and symptom-maintaining mechanisms. The empirical demonstration of direct within-person effects, untangled from genetic and stable environmental confounders, provides support for the necessity of addressing pain and distress as comorbidities in the management of fatigue, and may inform further research into clinical treatment options. While the exact pathogenesis and the comprehensive understanding of potential causal mechanisms of fatigue remains elusive, and the relationships with pain and distress remain outside of experimental control, our findings nevertheless suggest a complex causal structure underlying these associations.

Phenotype fatigue was shown to have a considerable heritable component of 45%, in line with earlier estimates (Hickie et al., 1999; Vassend et al., 2018), with a stable non-shared environmental component of 22%, and a time-varying component of 27%. The non-shared environmental component demonstrates that there is additional stability within individuals not attributable to additive genetic effects. Pain and distress showed moderate heritable components within the range of heritability estimates from earlier studies on pain (Williams, Spector, & MacGregor, 2010) and distress (Agrawal, Jacobson, Gardner, Prescott, & Kendler, 2004; Rijsdijk et al., 2003), but also considerable stable non-shared environmental components, albeit to a lesser degree for pain (14%) than for distress (27%).

The regression models indicate that both musculoskeletal pain and psychological distress have significant effects on fatigue through shared genetic causes, in line with previous research, which has shown that an abundance of the covariance between these phenotypes can be attributed to pleiotropic effects (i.e. shared genetic susceptibility) (Corfield et al., 2016b; Vassend et al., 2018). An epistemic challenge in understanding these relationships has, however, been to control for the effects of additional environmental confounders which might mediate or moderate these associations. By using a within-person control condition, we isolated the effects of the non-shared environment, and pain and distress showed significant and strong effects on fatigue also at this level. This, in turn, indicates that intra-individual stability in pain and distress is associated with fatigue, beyond the effects of having the same genetic material. Following these control conditions, comorbidity indicators were employed to control for somatic illness burden, which could potentially explain some of the genetic or environmental covariance between these phenomena. Most illness categories showed significant effects, but did not reduce the time-varying effects of distress and pain considerably. This indicates that while there are evidently shared etiological influences underlying these phenotypes, these associations are not merely due to shared genetic and environmental causes, or due to somatic illness. Of interest to future studies that do not contain genetically informed data, the mere inclusion of pain as a time-varying predictor explains 74% of the additive genetic variance in fatigue, and this could conceptually entail that controlling for pain in models of fatigue could serve to eliminate a great deal of genetic confounding, and serve as a quasi-co-twin-control method.

While the longitudinal co-twin design employed in this study provides opportunities for inference of effects free from genetic and dispositional confounding, the effects may, however, be bidirectional (McAdams et al., 2020; McGue et al., 2010), and the exact direction of the relationships between pain, distress and fatigue cannot be inferred from our results. An earlier review of studies examining the associations between pain and fatigue, found that there was ample evidence for an etiological association between them (Fishbain et al., 2003), but as later pointed out by Lenaert, Meulders, and van Heugten (2018), there was at that time insufficient evidence to establish unidirectional causality. More recent studies have attempted to investigate directional influences between these symptoms. One recent study investigated the temporal patterns of fatigue, pain and depression in multiple sclerosis, and found a strong bidirectional influence between pain and fatigue, while depression showed no significant temporal association with fatigue (Kratz, Murphy, & Braley, 2017). A study on patients with traumatic brain injury found that pain was linked to fatigue only in the first months following injury, whereas depression remained a strong correlate of fatigue across the first year post-injury (Beaulieu-Bonneau & Ouellet, 2017). A longitudinal study of primary care patients presenting with fatigue examined the temporal relation between fatigue and pain, and found best support for a model of synchronous changes in fatigue and pain across time (Nijrolder, van der Windt, Twisk, & van der Horst, 2010). The results from our study establishes similar and robust synchronous changes in pain and fatigue across time, and furthermore provides a hierarchical overview of stable genetic and environmental contributions to susceptibility for fatigue and pain in general. When examining the impact of pain on fatigued versus non-fatigued adolescents with Epstein–Barr infection, both the number of pain symptoms and pain severity were elevated in the fatigued group, and pain had a significant negative impact on quality of life for those suffering from chronic fatigue following infection (Brodwall, Pedersen, Asprusten, & Wyller, 2020). The authors concluded that pain in chronic fatigue is essential to clinical management and further research into interventions for fatigue. The findings from our study illustrate that a considerable degree of the co-occurrence of pain and fatigue is due to genetic and stable environmental influences contributing to vulnerability for both, but additionally that there is also a relationship between them over time. This strengthens the proposal from Brodwall et al. (2020) that pain should be construed as a candidate for treatment in conjunction with chronic fatigue.

These studies, along with our findings, seem to converge towards an understanding of pain and fatigue as particularly intertwined symptoms across time in a variety of clinical conditions, even though our findings does indicate overlap in genetic and environmental causes for both. This is in line with more recent proposals for understanding pain and fatigue as expressions of similar systems with overlapping biological, psychological and social mechanisms with bidirectional influences (Lenaert et al., 2018; Van Damme et al., 2018; Wyller, 2019).

Mechanisms of underlying associations

Earlier studies of the genetic contributions to fatigue have primarily focused on biological mechanisms, and according to a review by Landmark-Høyvik et al. (2010) the progress has been hindered by a lack of statistical power and inconsistent phenotype definitions. A recent review of studies examining specific genetic polymorphisms underlying chronic fatigue conditions, implicates single nucleotide polymorphisms related to HPA-axis regulation, immune-mediated inflammatory processes and various neurotransmitter regulation (Wang, Yin, Miller, & Xiao, 2017). Interestingly, HPA axis dysregulation and inflammatory processes have also been pathophysiologically linked to depression and chronic pain disorders (Pariante & Lightman, 2008; Woda, Picard, & Dutheil, 2016), which might explain the shared genetic vulnerability between pain, distress and fatigue. Boksem and Tops (2008) proposed a model for fatigue as an initially adaptive response to unconscious evaluations of reward and energetical costs in activity, with reward circuits including such neural structures as nucleus accumbens, orbitofrontal cortex, amygdala, insula and anterior cingulate cortex. Within this theoretical framework, HPA axis dysregulation, inflammatory processes and neurotransmitter imbalances (dopamine systems in particular) are hypothesized to contribute to chronification of fatigue. Later proposals for understanding the role of pain in fatigue build upon this conceptualization of fatigue as a homeostatic signal, and suggest that pain may interfere with the balance between perceived rewards and energetical costs (Van Damme et al., 2018; Wyller, 2019). Furthermore, biological underpinnings of central sensitization may be implied as a common genetic basis for fatigue, pain and distress, and has been increasingly implicated as a candidate mechanism for the chronification of pain, including in CFS (Meeus & Nijs, 2007). Central sensitization has been closely linked with stress dysregulation and psychological distress (Yunus, 2007), although it is unlikely that central sensitization in isolation can explain the development and exacerbation of fatigue (Yunus, 2015).

When considering stable (dispositional) environmental factors which might underlie the associations between pain, distress and fatigue, neuroticism or trait negative affectivity warrants some attention. Previous twin studies have found evidence for a common heritable factor underlying both neuroticism and psychological distress (Kendler et al., 2019), through an individual tendency for experiencing negative affectivity. Trait neuroticism is also associated with catastrophizing and avoidance in pain disorders, two widely implicated mechanisms in the chronification of pain (Goubert, Crombez, & Van Damme, 2004; Leeuw et al., 2007).

Lastly, the current results indicate that pain and distress exert significant time-varying effects on fatigue. Through controlling for genetic and stable environmental confounding between them, these findings are highly suggestive of direct effects within time, with a particularly robust effect of pain. This establishes that changes in distress and particularly pain are associated with changes in fatigue within individuals, beyond that attributable to genetic or stable environmental predispositions.

Conclusions: implications for clinical understanding of fatigue

This study provides incremental evidence for the genetic, environmental and time-varying architecture underlying the relationship between musculoskeletal pain, psychological distress and fatigue. More research is needed to disentangle the exact genetic, epigenetic, and environmental mechanisms in the development of fatigue, and translational research is warranted to better understand the implications of these causal relations. While genetic and stable non-shared environmental factors may not be viable targets for treatment as of yet, due to their relatively stable nature, the demonstration that pain and distress are causally linked with fatigue indicates that comorbid complaints of pain and distress should be construed as important and viable targets for clinical interventions in persons with clinical levels of fatigue. Pain showed particularly robust time-varying effects, and should always be assessed and addressed in the presence of fatigue complaints. Furthermore, somatic comorbidity also showed significant effects on fatigue, but did not reduce the effects of pain and distress, supporting the notion that pain and distress may represent transdiagnostic mechanisms for maintenance and exacerbation of fatigue (Menting et al., 2018). Further research is warranted to examine the disease-specific relevance of these factors, and other potential factors contributing to the both phenotypically and etiologically heterogenous fatigue symptom.

Limitations

One underlying assumption for valid estimation of heritability and heritability-based statistics is the equal environments assumption. This assumption holds that monozygotic and dizygotic twins are influenced in a similar manner by their shared environment. While the assumption may not hold as universally valid, violations from the assumption are unlikely to bias the result considerably (Felson, 2014). Specific directional paths between distress, pain and fatigue cannot be isolated based on our findings, but the confounding-free effects evidently show covariation across time, supportive of presumably bidirectional or synchronous effects, in line with earlier research. One limitation, however, is that our design does not eliminate all confounding from the non-shared environment (see Figure 3), and that life events in between measurement timepoints might exert influences on fatigue, distress and pain that explain some proportion of the time-varying association between them. Further longitudinal studies with closer spaced measurement intervals and control over other potential moderators and mediators might contribute to a better understanding of this dynamic.

Supplementary Material

Glossary

Abbreviations: AIC: Akaike Information Criterion; CFS: Chronic Fatigue Syndrome; Dz: Dizygotic; GSCL: Giessen Subjective Complaints List; ME: Myalgic Encephalomyelitis; Mz: Monozygotic; NSE: Non-Shared Environment; SCL: Symptoms Checklist

Funding Statement

The corresponding author was funded by Stiftelsen Dam, grant FO202360. EY was supported by the Research Council of Norway, grant 288083.

Data availability statement

The relevant estimates and data for this study have been made available in this manuscript. Due to restrictions from the Norwegian Twin Registry (organized by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health) and privacy restrictions, individual twin data is unavailable for the public. Information on applications for data access can be found here: https://www.fhi.no/en/more/health-studies/norwegian-twin-registry/

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aaronson, L. S., Teel, C. S., Cassmeyer, V., Neuberger, G. B., Pallikkathayil, L., Pierce, J., … Wingate, A. (1999). Defining and measuring fatigue. Image--the Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 31(1), 45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, A., Jacobson, K. C., Gardner, C. O., Prescott, C. A., & Kendler, K. S. (2004). A population based twin study of sex differences in depressive symptoms. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 7(2), 176–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball, H. A., Siribaddana, S. H., Sumathipala, A., Kovas, Y., Glozier, N., McGuffin, P., & Hotopf, M. (2010a). Environmental exposures and their genetic or environmental contribution to depression and fatigue: A twin study in Sri Lanka. BMC Psychiatry, 10(1), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball, H. A., Sumathipala, A., Siribaddana, S. H., Kovas, Y., Glozier, N., McGuffin, P., & Hotopf, M. (2010b). Aetiology of fatigue in Sri Lanka and its overlap with depression. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 197(2), 106–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu-Bonneau, S., & Ouellet, M.-C. (2017). Fatigue in the first year after traumatic brain injury: Course, relationship with injury severity, and correlates. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 27(7), 983–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boksem, M. A., & Tops, M. (2008). Mental fatigue: Costs and benefits. Brain Research Reviews, 59(1), 125–139. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bower, J. E. (2014). Cancer-related fatigue—mechanisms, risk factors, and treatments. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 11(10), 597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodwall, E. M., Pedersen, M., Asprusten, T. T., & Wyller, V. B. B. (2020). Pain in adolescent chronic fatigue following Epstein-Barr virus infection. Scandinavian Journal of Pain, 20(4), 765–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bültmann, U., Kant, I., Kasl, S. V., Beurskens, A. J., & van den Brandt, P. A. (2002). Fatigue and psychological distress in the working population: Psychometrics, prevalence, and correlates. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 52(6), 445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corfield, E. C., Martin, N. G., & Nyholt, D. R. (2016a). Co-occurrence and symptomatology of fatigue and depression. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 71, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corfield, E. C., Martin, N. G., & Nyholt, D. R. (2016b). Shared genetic factors in the co-occurrence of depression and fatigue. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 19(6), 610–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corfield, E. C., Martin, N. G., & Nyholt, D. R. (2017). Familiality and heritability of fatigue in an Australian twin sample. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 20(3), 208–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes Rivera, M., Mastronardi, C., Silva-Aldana, C. T., Arcos-Burgos, M., & Lidbury, B. A. (2019). Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: A comprehensive review. Diagnostics, 9(3), 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creavin, S. T., Dunn, K. M., Mallen, C. D., Nijrolder, I., & van der Windt, D. A. (2010). Co-occurrence and associations of pain and fatigue in a community sample of Dutch adults. European Journal of Pain, 14(3), 327–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis, L. R., Lipman, R. S., Rickels, K., Uhlenhuth, E. H., & Covi, L. (1974). The hopkins symptom checklist (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventory. Behavioral Science, 19(1), 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, F., Wu, S., & Mead, G. E. (2012). Frequency and natural history of fatigue after stroke: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 73(1), 18–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felson, J. (2014). What can we learn from twin studies? A comprehensive evaluation of the equal environments assumption. Social Science Research, 43, 184–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finsterer, J., & Mahjoub, S. Z. (2014). Fatigue in healthy and diseased individuals. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 31(5), 562–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbain, D. A., Cole, B., Cutler, R. B., Lewis, J., Rosomoff, H. L., & Fosomoff, R. S. (2003). Is pain fatiguing? A structured evidence-based review. Pain Medicine, 4(1), 51–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freidin, M. B., Wells, H. R., Potter, T., Livshits, G., Menni, C., & Williams, F. M. (2018). Metabolomic markers of fatigue: Association between circulating metabolome and fatigue in women with chronic widespread pain. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease, 1864(2), 601–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goubert, L., Crombez, G., & Van Damme, S. (2004). The role of neuroticism, pain catastrophizing and pain-related fear in vigilance to pain: A structural equations approach. Pain, 107(3), 234–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, M., & Tannock, C. (2004). Objective assessment of personality disorder in chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 56(2), 251–254. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00571-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickie, I., Bennett, B., Lloyd, A., Heath, A., & Martin, N. (1999a). Complex genetic and environmental relationships between psychological distress, fatigue and immune functioning: A twin study. Psychological Medicine, 29(2), 269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickie, I., Kirk, K., & Martin, N. (1999b). Unique genetic and environmental determinants of prolonged fatigue: A twin study. Psychological Medicine, 29(2), 259–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler, K. S., Gardner, C. O., Neale, M. C., Aggen, S., Heath, A., Colodro-Conde, L., … Gillespie, N. A. (2019). Shared and specific genetic risk factors for lifetime major depression, depressive symptoms and neuroticism in three population-based twin samples. Psychological Medicine, 49(16), 2745–2753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratz, A. L., Murphy, S. L., & Braley, T. J. (2017). Pain, fatigue, and cognitive symptoms are temporally associated within but not across days in multiple sclerosis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 98(11), 2151–2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen, M. S., Stabursvik, J., O'Leary, E. C., Pedersen, M., Asprusten, T. T., Leegaard, T., … Godang, K. (2019). Clinical symptoms and markers of disease mechanisms in adolescent chronic fatigue following Epstein-Barr virus infection: An exploratory cross-sectional study. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 80, 551–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers, F., Hickie, I., & Merikangas, K. R. (2013). Prevalence and correlates of prolonged fatigue in a U.S. sample of adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(5), 502–510. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12040454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landmark-Høyvik, H., Reinertsen, K. V., Loge, J. H., Kristensen, V. N., Dumeaux, V., Fosså, S. D., … Edvardsen, H. (2010). The genetics and epigenetics of fatigue. PM&R, 2(5), 456–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeuw, M., Goossens, M. E., Linton, S. J., Crombez, G., Boersma, K., & Vlaeyen, J. W. (2007). The fear-avoidance model of musculoskeletal pain: Current state of scientific evidence. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 30(1), 77–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenaert, B., Meulders, A., & van Heugten, C. M. (2018). Tired of pain or painfully tired? A reciprocal relationship between chronic pain and fatigue. Pain, 159(6), 1178–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loge, J. H., Ekeberg, Ø, & Kaasa, S. (1998). Fatigue in the general Norwegian population: Normative data and associations. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 45(1), 53–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnus, P., Berg, K., & Nance, W. E. (1983). Predicting zygosity in Norwegian twin pairs born 1915-1960. Clinical Genetics, 24(2), 103–112. <Go to ISI>://WOS:A1983RF13100004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manjaly, Z. M., Harrison, N. A., Critchley, H. D., Do, C. T., Stefanics, G., Wenderoth, N., … Stephan, K. E. (2019). Pathophysiological and cognitive mechanisms of fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 90(6), 642–651. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-320050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matura, L. A., Malone, S., Jaime-Lara, R., & Riegel, B. (2018). A systematic review of biological mechanisms of fatigue in chronic illness. Biological Research for Nursing, doi: 10.1177/1099800418764326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams, T. A., Rijsdijk, F. V., Zavos, H. M., & Pingault, J.-B. (2020). Twins and causal inference: Leveraging nature's experiment. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, 11(6), Article a039552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue, M., Osler, M., & Christensen, K. (2010). Causal inference and observational research: The utility of twins. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(5), 546–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeus, M., & Nijs, J. (2007). Central sensitization: A biopsychosocial explanation for chronic widespread pain in patients with fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome. Clinical Rheumatology, 26(4), 465–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menting, J., Tack, C. J., Bleijenberg, G., Donders, R., Droogleever Fortuyn, H. A., Fransen, J., … van der Werf, S. P. (2018). Is fatigue a disease-specific or generic symptom in chronic medical conditions? Health Psychology, 37(6), 530–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollayeva, T., Kendzerska, T., Mollayeva, S., Shapiro, C. M., Colantonio, A., & Cassidy, J. D. (2014). A systematic review of fatigue in patients with traumatic brain injury: The course, predictors and consequences. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 47, 684–716. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nater, U. M., Jones, J. F., Lin, J. M., Maloney, E., Reeves, W. C., & Heim, C. (2010). Personality features and personality disorders in chronic fatigue syndrome: A population-based study. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 79(5), 312–318. doi: 10.1159/000319312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman, D. A. (2014). Missing data: Five practical guidelines. Organizational Research Methods, 17(4), 372–411. [Google Scholar]

- Nijrolder, I., van der Windt, D. A., Twisk, J. W., & van der Horst, H. E. (2010). Fatigue in primary care: Longitudinal associations with pain. Pain, 150(2), 351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen, T. S., Knudsen, G. P., Gervin, K., Brandt, I., Røysamb, E., Tambs, K., … Magnus, P. (2013). The Norwegian twin registry from a public health perspective: A research update. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 16(1), 285–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormstad, H., & Eilertsen, G. (2015). A biopsychosocial model of fatigue and depression following stroke. Medical Hypotheses, 85(6), 835–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pariante, C. M., & Lightman, S. L. (2008). The HPA axis in major depression: Classical theories and new developments. Trends in Neurosciences, 31(9), 464–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patejdl, R., Penner, I. K., Noack, T. K., & Zettl, U. K. (2016). Multiple sclerosis and fatigue: A review on the contribution of inflammation and immune-mediated neurodegeneration. Autoimmunity Reviews, 15(3), 210–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penner, I. K., & Paul, F. (2017). Fatigue as a symptom or comorbidity of neurological diseases. Nature Reviews Neurology, 13(11), 662–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poeschla, B., Strachan, E., Dansie, E., Buchwald, D. S., & Afari, N. (2013). Chronic fatigue and personality: A twin study of causal pathways and shared liabilities. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 45(3), 289–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabe-Hesketh, S., & Skrondal, A. (2012). Multilevel and longitudinal modeling using stata (3rd ed.). College Station, TX: STATA press. [Google Scholar]

- Rabe-Hesketh, S., Skrondal, A., & Gjessing, H. K. (2008). Biometrical modeling of twin and family data using standard mixed model software. Biometrics, 64(1), 280–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Gibby, C. C., Mendoza, T. R., Wang, S., Anderson, K. O., & Cleeland, C. S. (2003). Pain and fatigue in community-dwelling adults. Pain Medicine, 4(3), 231–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijsdijk, F., Snieder, H., Ormel, J., Sham, P., Goldberg, D., & Spector, T. (2003). Genetic and environmental influences on psychological distress in the population: General health questionnaire analyses in UK twins. Psychological Medicine, 33(5), 793–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, H., Lang, M., Kiltz, K., & Lang, C. (2015). Is personality profile a relevant determinant of fatigue in multiple sclerosis? Frontiers in Neurology, 6, 2. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2015.00002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G. D. (2011). Epidemiology, epigenetics and the ‘gloomy prospect’: Embracing randomness in population health research and practice. International Journal of Epidemiology, 40(3), 537–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. (2019). Stata Statistical software: Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Strand, B. H., Dalgard, O. S., Tambs, K., & Rognerud, M. (2003). Measuring the mental health status of the Norwegian population: A comparison of the instruments SCL-25, SCL-10, SCL-5 and MHI-5 (SF-36). Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 57(2), 113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, P. F., Evengård, B., Jacks, A., & Pedersen, N. L. (2005). Twin analyses of chronic fatigue in a Swedish national sample. Psychological Medicine, 35(9), 1327–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikhodeyev, O. N., & Shcherbakova, ОV. (2019). The problem of non-shared environment in behavioral genetics. Behavior Genetics, 49(3), 259–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme, S., Becker, S., & Van der Linden, D. (2018). Tired of pain? Toward a better understanding of fatigue in chronic pain. Pain, 159(1), 7–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassend, O., Lian, L., & Andersen, H. T. (1992). Norske versjoner av NEO-personality inventory, Symptom Checklist 90 revised og Giessen subjective complaints list. Del I. Tidsskrift for Norsk Psykologforening, 29(12), 1150–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Vassend, O., Røysamb, E., Nielsen, C. S., & Czajkowski, N. O. (2018). Fatigue symptoms in relation to neuroticism, anxiety-depression, and musculoskeletal pain. A longitudinal twin study. Plos One, 13(6), e0198594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T., Yin, J., Miller, A. H., & Xiao, C. (2017). A systematic review of the association between fatigue and genetic polymorphisms. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 62, 230–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, F. M., Spector, T. D., & MacGregor, A. J. (2010). Pain reporting at different body sites is explained by a single underlying genetic factor. Rheumatology, 49(9), 1753–1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woda, A., Picard, P., & Dutheil, F. (2016). Dysfunctional stress responses in chronic pain. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 71, 127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyller, V. B. B. (2019). Pain is common in chronic fatigue syndrome–current knowledge and future perspectives. Scandinavian Journal of Pain, 19(1), 5–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yunus, M. B. (2007). Fibromyalgia and overlapping disorders: The unifying concept of central sensitivity syndromes. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism, 36(6), 339–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yunus, M. B. (2015). Editorial review (thematic issue: An update on central sensitivity syndromes and the issues of nosology and psychobiology). Current Rheumatology Reviews, 11(2), 70–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The relevant estimates and data for this study have been made available in this manuscript. Due to restrictions from the Norwegian Twin Registry (organized by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health) and privacy restrictions, individual twin data is unavailable for the public. Information on applications for data access can be found here: https://www.fhi.no/en/more/health-studies/norwegian-twin-registry/