Abstract

Background

Without a cure, vaccination is the most reliable means of combating COVID-19 pandemic, since non-pharmacological measures could not prevent its spread, as evidenced in the emergence of a second wave. This study assessed the readiness of pharmacists to receive, recommend and administer COVID-19 vaccines to clients in Nigeria.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study in which responses were collected from pharmacists in Nigeria through Google Form link. A 21-item questionnaire was developed and validated for the study. The link was shared on the WhatsApp groups of eligible respondents. The response was downloaded into Microsoft Excel (2019) and cleared of errors. This was uploaded into KwikTables (Beta Version 2021) for data analysis. Descriptive statistics such as frequencies and percentages were used to describe the data. Chi-squared test was used to determine the relationship between all the responses and the practice areas of the pharmacists.

Results

A total of 509 pharmacists responded to the study, but 507 indicated their areas of practice. The highest response of 247(48.7%) was obtained from hospital pharmacists, then community pharmacists; 157(31.0%). Hospital and community pharmacists accounted for 96 and 66 of the 191(37.7%) pharmacists that would probably accept the vaccine (p=0.126). The Pfizer-bioNTech vaccine was the preferred brand for 275(54.2%) respondents. Healthcare Professionals>Elderly>General Populace>Children was the order of roll-out recommended by 317(62.5%). Adverse-effect-following-immunization was the concern of 330(65.1%) pharmacists. Age was a factor in their likelihood of recommending the COVID-19 vaccine to clients (p=0.001).

Conclusion

This study established that most pharmacists are willing to accept to be vaccinated against COVID-19, recommend and administer it to other citizens. They were impressed by the effectiveness and cost of some of the vaccines, but were concerned about their possible adverse effects. The pharmacists would want the authorities to consider strategies that will make the vaccines accessible to all citizens.

Keywords: COVID-19 vaccine, hesitancy, Pharmacists, recommend, vaccination, virus

Introduction

Nearly all the countries on the globe are battling a resurgence of the COVID-19 infection, commonly termed the second wave of the pandemic. The second wave, like the first, has stretched the healthcare facilities of most nations, with many countries having a shortage of pharmaceuticals for use in intensive care units, especially oxygen1. The global burden of the disease was reported by the World Health Organization to be 103,362,039, with a reported casualty of 2,244,713 deaths as at 3rd February, 20212. Africa is not spared of the challenges of the second wave of the pandemic as well3. With over a year gone since the declaration of COVID-19 as a pandemic, there is no research that has resulted in a definitive curative therapy for the disease4. Rather, symptomatic management has been employed by clinicians in reducing the fatality rate of the disease5. The main strategies that have been used in the control of the pandemic are non-pharmacological prophylactic measures. Examples of such preventive strategies are social distancing and use of facemasks with or without face shields when outdoor, avoidance of touching the mouth, nose and eyes, constant washing of the hands with running water, among others6–8. These non-pharmacological measures seem not to be sufficient to prevent the spread of the infection, as it is obvious from its resurgence after the lockdown orders in many countries were lifted. With the failure of the non-pharmacological measures, the use of vaccines that can prevent the spread of the disease is the obvious and more reliable alternative9. The use of vaccines stand out as a better option, considering the fact that vaccines have proven to be successful in combating the horizontal transmission of communicable diseases10.

With the roll-out of some vaccines for use in the prevention of COVID-19 in some countries11, the focus is now turning to the means of getting the vaccines to the communities and the acceptance of the vaccines by the populace. Healthcare professionals have an important role to play in getting the already available vaccines to the people. The acceptability of the vaccines by the healthcare workers can serve as a boost on its own to the acceptance of the vaccines by the general populace. Likewise, people trust their healthcare professionals and will be more accepting of the vaccines on the recommendations of their healthcare professionals. The administration of the vaccines also rests with well-trained healthcare professionals12.

Among the healthcare professionals, Pharmacists, especially those that practice in the community settings, have been reported to be the most accessible, even in primary healthcare13,14. In the administration of vaccines, those of COVID-19 pandemic inclusive, pharmacists play such roles as maintenance of the cold chain for the vaccines, administration of the vaccines, provision of pharmaceutical care services to clients, and involvement in the training of colleagues15. The provision of COVID-19 vaccines will require the involvement of all healthcare professionals, irrespective of their practice settings. This is because the eradication of the pandemic will require the vaccination of every member of the society. Hence, the participation of pharmacists will require that practitioners from the hospitals, community practice, industry, academia and even those that are in administration and other non-pharmacy areas. It is pertinent to note that the currently available vaccines may not be enough to reach everybody in the community. Thus, it would be study-worthy to know the perception of these critical healthcare professionals about the vaccines.

Aim of the study

The objective of this study was to assess the readiness of pharmacists to be vaccinated against COVID-19 as well as their recommendation and administration of the vaccines to clients, irrespective of their practice areas.

Ethics Approval

An institutional review board approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences of the University of Nigeria (FPSRE/UNN/20/00312), although the study did not involve the use of specific patients of a disease. No identifier information was obtained from the respondents, just as confidentiality was maintained throughout the study. Respondents' consent to participate in the study was obtained by requesting them to compulsorily indicate their willingness to participate in the study after explaining the purpose of the study to them at the beginning of the questionnaire.

Methods

Design

This was a cross-sectional study in which responses were collected online from respondents through Google Form links.

Study Settings and Participants

This study was conducted among registered pharmacists in Nigeria. The study included all pharmacists including those that are not practicing. This was because, in a pandemic, health authorities could choose to involve all qualified personnel in their public health activities (such as recommendations and administration of vaccines) even if those that are not practicing would require short refresher courses. With a population of over 250 million as at 2020, Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa and accounts for the largest population of black people in the world. The Nigerian Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) reported that as at 3rd February 2021, there were 134,690 cases of COVID-19 infections confirmed in Nigeria 16. Although the fatality rate has been low so far, with the number of infected persons who died from COVID-19 disease being 1,618, an uncontrolled infectious rate of COVID-19 in Nigeria poses a risk not only to the African continent but to the whole world. Apart from the issue of Nigerians travelling to and fro different countries, the country shares border with about four countries: the borders are porous and difficult to control by health officials. Pharmacists in Nigeria practise in community pharmacies, hospitals, educational and research institutions, non-governmental organizations, administrative offices, and pharmaceutical industries. There were about 15000 registered pharmacists in Nigeria in 2020, majority of who practice in the community and hospitals settings.

Study Instrument

A 21-item questionnaire was developed and validated for the study. Section A had nine items and inquired about respondents' characteristics. Section B contained 10 questions and assessed the respondents' likelihood (viz.: definitely not, probably and certainly) of receiving, recommending and administering COVID-19 vaccines as well as the preferred order of recipients of the vaccines. Section C comprised a single item which measured the respondents' choice vaccine and their perceived concerns about the currently available vaccines. The questions in the questionnaires were developed from extensive search in paper and electronic literatures. Content validation was done by a group of experts at the University of Nigeria while face validation was conducted using 10 pharmacists who were excluded from the main study's data collection. The final instrument was adopted after obtaining an acceptable Cronbach's alpha value of 0.89.

Data Collection Procedure

The eligibility criterion considered for participation in this study was that respondents were consenting registered pharmacists residing and practising in Nigeria at the time of the study. Using Raosoft online sample size calculator with a margin of error set at 5% and a confidence interval of 95%, the minimum number required for the study sample to be a true representation of the population was 377, with the researchers giving an allowance of 10%. The study instrument was converted into a Google Form and the link was shared on the WhatsApp groups of the national groups of pharmacists in Nigeria. Periodic reminder messages containing the same link to the online form were sent to the individual WhatsApp accounts of the Pharmacists in the groups. The use of WhatsApp in collecting data was to checkmate response from non-pharmacists, as the WhatsApp platforms have administrators that screen participants before including them. However, respondents were requested not to share the link with any other person. The use of WhatsApp also afforded the researchers the ability to determine the number of participants that actually read the message that requested them to complete the study questionnaire. In addition, the use of national associations' platforms would allow the generalization of the findings, as members from all regions of the country across all ages would be reached. At the end of the three-week data collection period, the link was disabled from collecting responses.

Data Management and Analysis

The recorded responses in the Google document was downloaded into Microsoft Excel (2019) and cleared of errors. This was uploaded into KwikTables (Beta Version 2021) for data analysis. Descriptive statistics such as frequencies and percentages were used to describe the data. In the presentation of the results, Chi-squared test was used to indicate the relationship between all the responses and the practice areas of the pharmacists. Thereafter, the socio-demographic characteristics that were related with the likelihood responses were identified. For all statistical analyses, p values less than 0.05 were considered to be significant.

Results

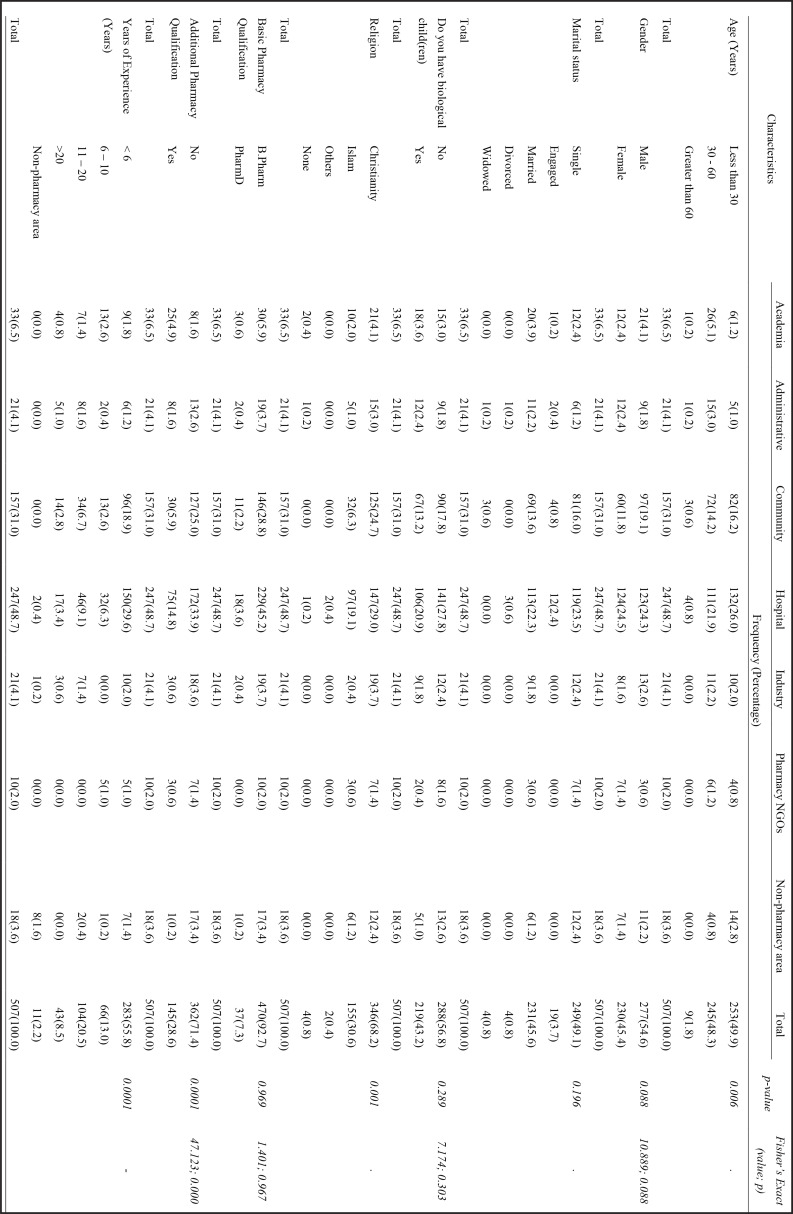

The study had a high response rate that exceeded the target sample size. A total of 509 pharmacists from different practice settings responded to the questionnaire, but 507 indicated their areas of practice. The highest response of 247 (48.7%) was obtained from pharmacists practising in the hospitals, closely followed by 157 (31.0%) from pharmacists in community practice. The respondents were almost age-balanced for ages below 60 years: 253 (49.9%) for those less than 30 years and 245 (48.3%) for those aged between 30 and 60 years. But the age distribution varied across practice settings (p=0.006). About half, 249 (49.1%), of the respondents were single, while 362 (71.4%) did not have an additional postgraduate pharmacy degree (p≤0.0001) and 283 (55.8%) had practised for less than six years (p=≤0.0001). Complete information about the respondents' characteristics is in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants' Sociodemographic Characteristics based on their Practice Area in Nigerian Pharmacy Sector

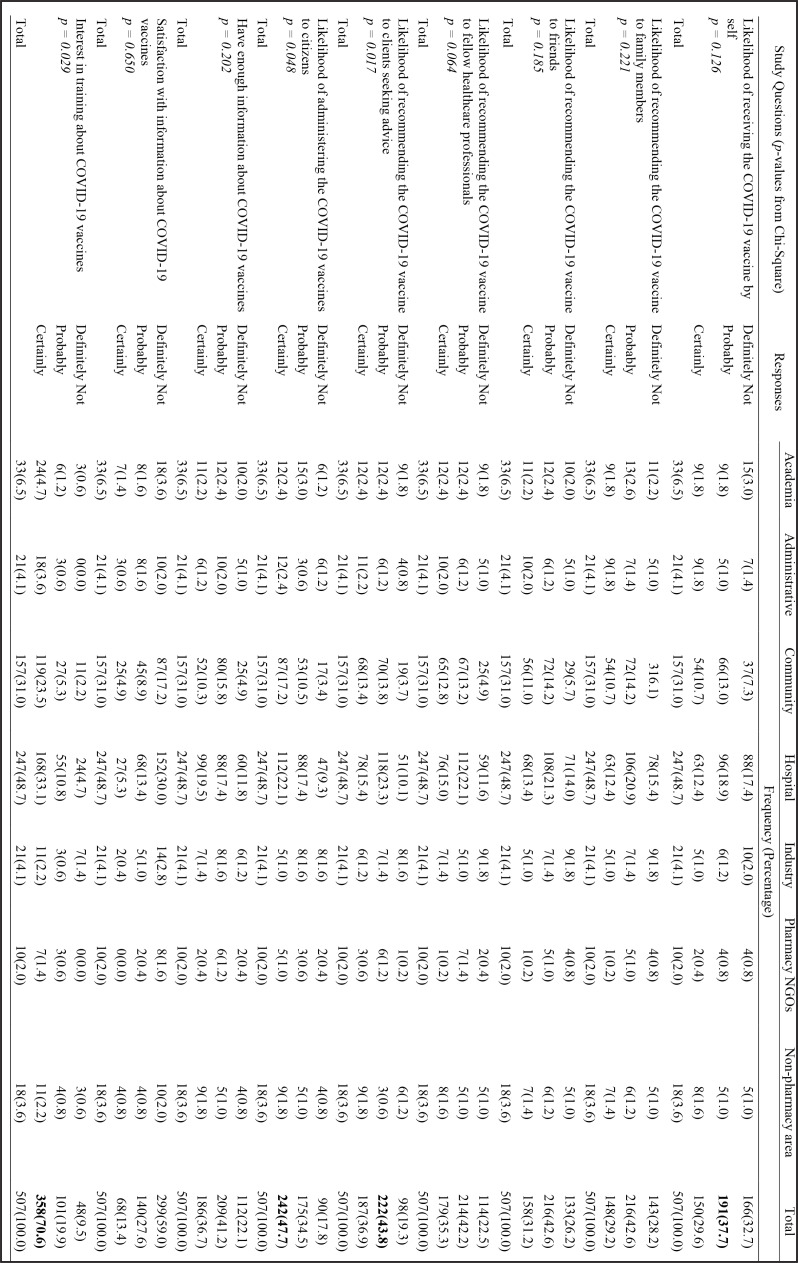

Out of the 507 pharmacists, 191 (37.7%) indicated that they would probably accept to be immunized with the COVID-19 vaccine. Hospital and community pharmacists accounted for 96 (50.26%) and 66 (34.55%) of the 191 pharmacists that would probably accept the vaccine, with the least report being from pharmacists that serve in pharmacy-related non-governmental organization (p = 0.126). There were no significant relationships between the practice areas of the pharmacist and the choices of likelihood of receiving (p = 0.126).

While 216 (42.6%) of the pharmacists would probably recommend the COVID-19 vaccine to their family members, 222 (43.8%) would probably recommend same to their clients. Practice settings did not have a relationship with the choice of recommending the vaccines for family members (p = 0.221), although it did have a relationship with recommending for clients (p = 0.017).

Hospital pharmacists were 112 (46.23%) of 242 respondents that would certainly administer the vaccines to citizens if they are permitted to do so. A total of 90 (17.8%) indicated that they would definitely not administer the vaccines to citizens if they are asked to do so. Practice settings of the pharmacists played a vital role in the likelihood of accepting to administer the vaccines to citizens (p = 0.048). Table 2 has the results of the Pharmacists' readiness to receive, recommend and administer COVID-19 vaccines.

Table 2.

Pharmacists' Readiness to Receive, Recommend and Administer Currently Available COVID-19 Vaccines based on their Practice Areas

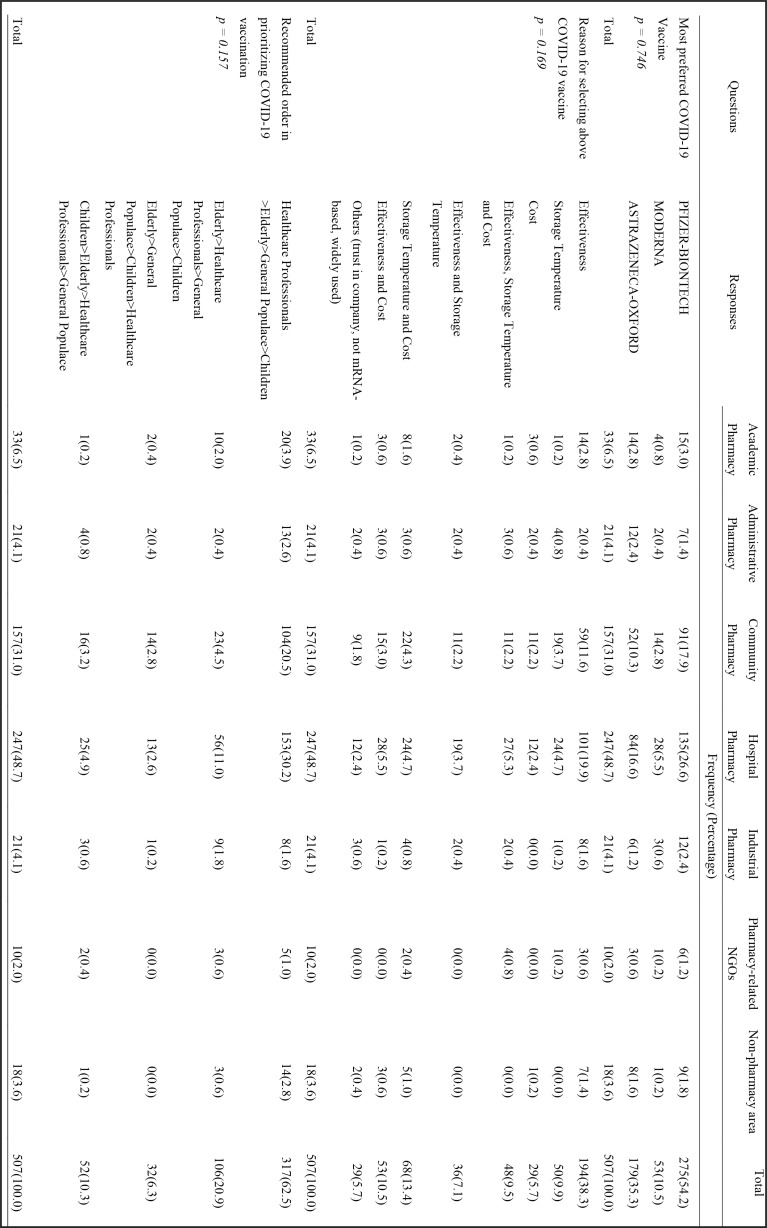

Out of the three COVID-19 vaccines with emergency use permission, 275 (54.2%) of the Nigerian pharmacists in the study preferred the Pfizer-bioNTech brand the most. Out of the 157 community pharmacists, 91 indicated a preference for Pfizer-bioNTech brand while 15 of 33 academic pharmacists preferred the same brand (p = 0.746). The main reason for the preference for Pfizer-bioNTech brand by the pharmacists was effectiveness, indicated by 194 (38.3%). On the recommended order of roll-out of the vaccines, 317 (62.5%) pharmacists chose Healthcare Professionals>Elderly>General Populace>Children, with 20 of the 33 academic pharmacist and 14 of the 18 pharmacists who do not work in a pharmacy area choosing the option (p = 0.157). (Table 3)

Table 3.

Pharmacists' Preferences for Available COVID-19 Vaccines and Recommended Order of Roll-out of the Vaccines in the Community

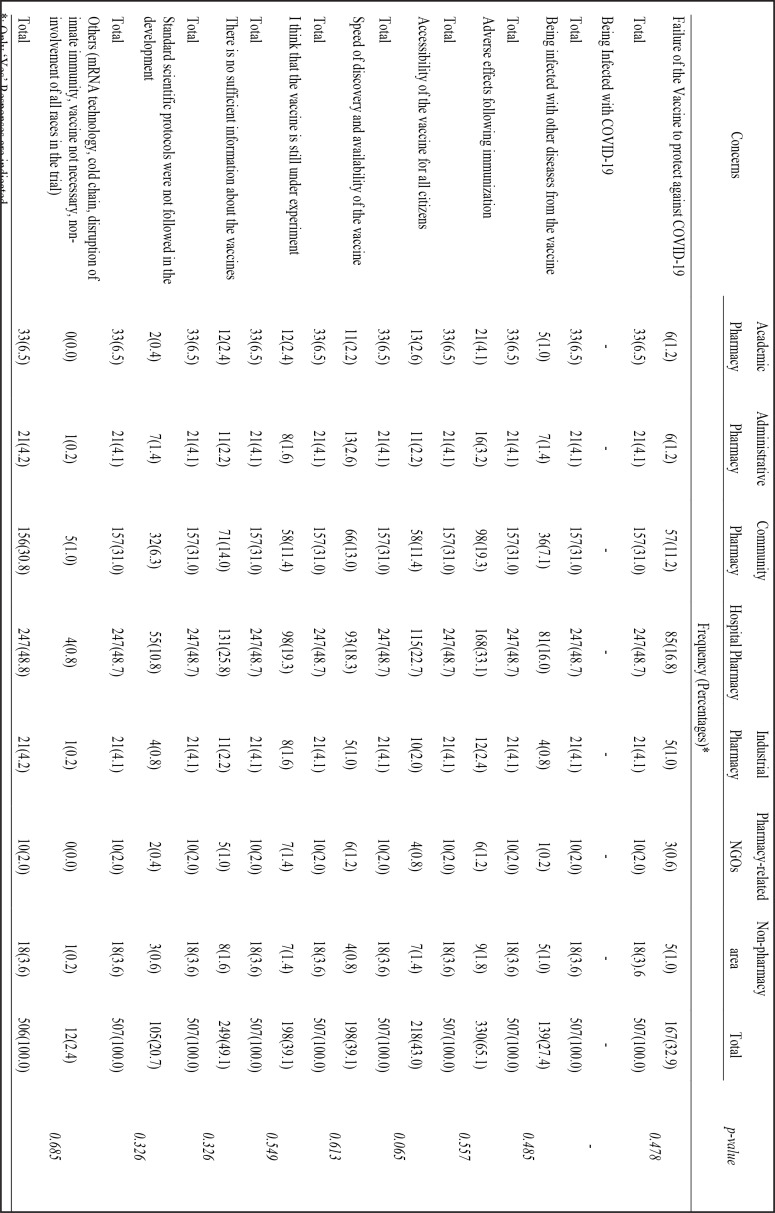

For the perceived concerns about the COVID19 vaccines, the fear of “adverse effect following immunization” was expressed by 330 (65.1%) pharmacists. No pharmacist feared that they could be infected with COVID-19 by the vaccine. Although 105 (20.7%) pharmacists reported that they were concerned that the development of the vaccines did not follow standard scientific procedure, pharmacists practising in the academia accounted for only two (p = 0.326). Twelve pharmacists expressed fears that were not listed in the questionnaire, such as the availability of cold chain for the vaccines and the use of mRNA technology. Table 4 documents all the perceived concerns of Nigerian pharmacists about the COVID-19 vaccines.

Table 4.

Concerns of the Pharmacists about the currently available COVID-19 Vaccines

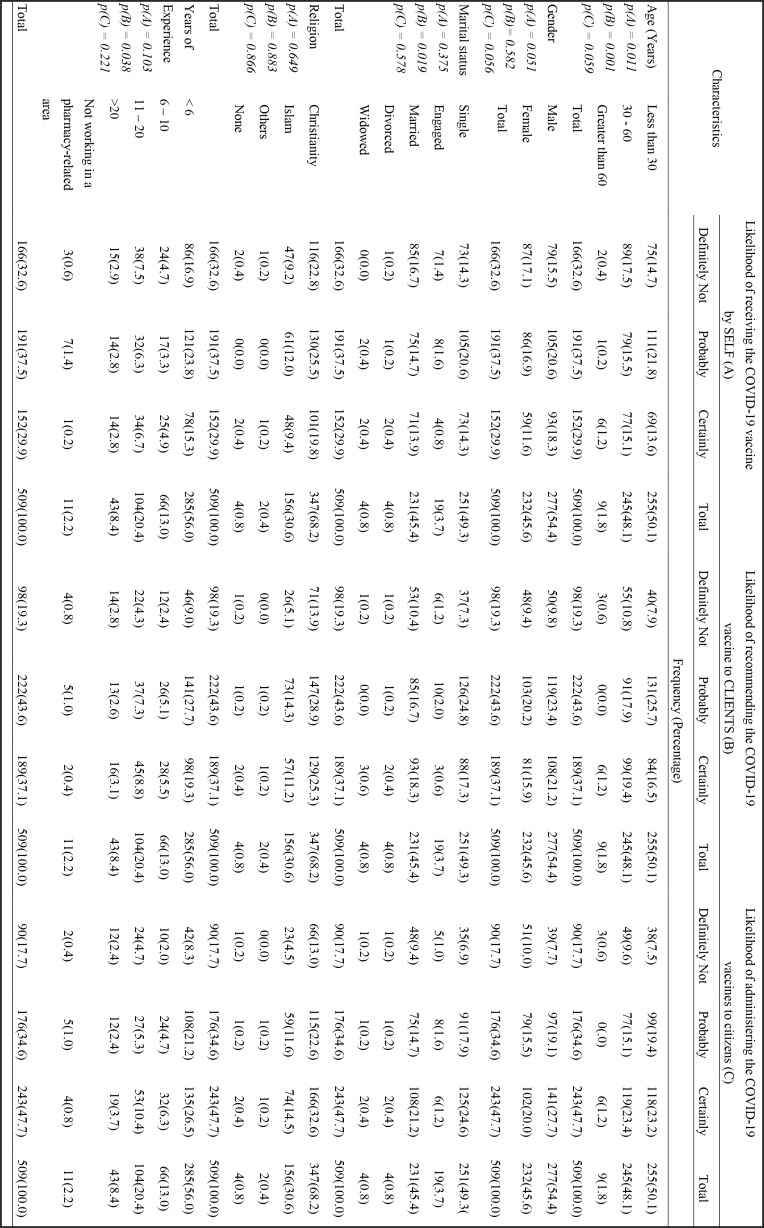

Age was the sociodemographic factor that had a statistically significant relationship with the two variables of likelihood to receive the COVID-19 vaccine by self (p = 0.011) and for clients (p = 0.001), as younger pharmacists were more likely to accept, recommend and administer the vaccine. Of all ages, 111 (21.8%), 131 (25.7%), and 99 (19.4%) respondents who were less than 30 years would probably accept the vaccine, recommend it to clients, and administer it to citizens, respectively. Definitely not was the response of 166 (32.6%) of pharmacists of all ages for accepting to be vaccinated while 222 (43.6%) respondents of all ages would probably recommend the vaccines to their clients. Years of experience had a significant relationship with the likelihood of recommending the vaccines for clients (p = 0.038), with 222 (43.6%) reporting that they would probably recommend it. The relationship between the sociodemographic characteristics and the likelihood of receiving, recommending and administering the vaccines are indicated in Table 5.

Table 5.

Relationship between the Pharmacists' Characteristics and their Likelihood of Receiving, Recommending and Administering COVID-19 Vaccines

Discussion

This study evaluated the willingness of pharmacists in different practice settings in Nigeria to accept to be vaccinated with the available COVID-19 vaccines, as well as their readiness to recommend and administer the vaccines to fellow citizens. More than half of the pharmacists that responded to the study questionnaire practise in the hospitals and community pharmacies, while majority of the respondents were in the ages of active service. The main reason for the unequal distribution could be that employments in those settings (especially the community pharmacies) are driven by the private sectors, unlike most others that would require employment in limited government facilities. Nonetheless, it is a strength to the study, as most pharmacists that would actually recommend and administer vaccines practice in the community and hospital pharmacies.

Principal Findings

The study findings showed that majority of the respondents would accept to be administered the available COVID-19 vaccines, although the level of acceptance varied between the different areas of practice. The respondents expressed similar positions in their willingness to recommend the vaccines to their family members, friends and fellow healthcare workers. However, their practice area played a role in their likelihood of recommending the vaccines to clients who seek their professional advice and their willingness to be involved in the administration of COVID-19 vaccines to citizens. Majority of the pharmacists that practise in the hospitals and community setting were willing to recommend and administer the vaccines to their clients. This could be attributed to the routine service delivery to clients that those groups of pharmacists engage in daily in their practice. In addition, they have the opportunity of directly being in contact with persons that have been diagnosed with the disease and would, thus, appreciate the value of vaccination against COVID-19 infection. The COVID-19 vaccine that was produced by Pfizer-BioNTech had the highest acceptability of the three that are currently in use in most countries by pharmacists in Nigeria. Among the three options that were provided to the respondents as possible reasons for the choice of the preferred vaccine, the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine did not report the highest level of effectiveness, but the respondents still chose it. This could be explained from their choices of other reasons, as the duo of storage condition and cost of the vaccine was the second reason that was preponderant among the pharmacists to account for their choice of the particular vaccine. It is noted that the vaccines are provided to the citizens at no cost, just as the government is also obtaining it at no cost from donor organizations at the moment. It is, however, obvious that the government may not be able to reach its over 200 million citizens with the free provision of the vaccines. Thus, the cost of the vaccines is an important variable, especially if the government would want to purchase the vaccines. The pharmacists in this study prefer that healthcare professionals should be given the highest priority in rolling out the vaccines, followed by the elderly citizens, then the general populace. This is an understandable choice in the order of administering the drugs. Vaccinating health workers, especially those that are at the front line of providing healthcare services to the people will ensure that every society has a reservoir of healthy and fit health service providers. This is in addition to safeguarding the healthcare workers who are at a risk of being infected with the disease by clients who seek their professional service. Many concerns were expressed by the pharmacists about the COVID-19 vaccines, but no choice had a relationship with their areas of practice. This implies that they had equal level of fear that informed the reasons why some may neither receive the vaccine nor recommend it to others. The respondents were most concerned about possible adverse effects that could result from the vaccination, even though specific adverse effects were not mentioned. Perhaps, when they are informed about the adverse effects and the ways of managing them, the likelihood of receiving and recommending the vaccine may be higher. Accessibility of the vaccines by all citizens was understandably a concern of many respondents, considering that many essential pharmaceuticals do not get to rural areas where majority of the citizens reside. The highest degree of likelihood was reported by the elderly respondents to receiving and recommending the vaccine. With the higher chance of being infected with the disease and high mortality rate in that age category, the result was expected.

Comparison with Previous Studies

The accessibility of pharmacists to clients in every community is commonly reported in literatures17–19. Health promotion campaigns succeed very well when they are involved, especially the pharmacists that practise in community premises14,15. Their willingness to participate in vaccination exercises have been reported in many studies. In a survey that was conducted in 2015 among community-based pharmacists in Canada, Edwards et al. found out that community pharmacists were willing to participate in immunization activities if they were licensed, after appropriate training, to do so20. Although the study focused on adult immunization, an acceptance to participate in infant immunization could also be construed, since the adults are the guardians and hold the consent for the infants. It would however require that they are reimbursed for such exercises, while every negative perception of their participation by other healthcare providers is cleared with due sensitizations. It must be noted that studies have proved that fellow healthcare workers in most communities, as well as the public, have accepted that pharmacists' roles should be expanded to include participation in immunization activities. Still in Canada, MacDougall et al. reported that the public and other healthcare providers have a good perception about pharmacists' participation in routine immunization21. One aspect of participation in immunization exercise that the respondents in the study rated the pharmacists to be high was that the pharmacists could be trusted for reliable information about immunization. The onus is thus on the policy makers so ensure that the respondents in the current study are well informed about the COVID-19 vaccines, since many of them reported that they did not have enough information about them, but would be willing to be trained. When pharmacists' involvement in vaccination was instituted in Western Australia, a study by Hattingh et al. reported that vaccine delivery by pharmacists was safe22. They further recommended that the scope of pharmacy practice should be expanded to include involvement in routine vaccination exercises which should be done with appropriate remuneration.

In Nigeria, pharmacists have not been involved by government in any form of community immunization programme, apart from storage and delivery of the vaccines. Oluwadamilola reported in a conference paper that almost all the community pharmacists that she contacted in Lagos, Nigeria, were willing to be trained and licensed to administer routine vaccines to the citizens23. Agbo et al. also reported from Cross River State, Nigeria, that the only form of immunization that community pharmacists were involved in was client-requested prophylaxis that required dispensing of tetanus toxoid, rabies vaccines, and hepatitis B vaccine24. The pharmacists who responded to the study however expressed the readiness to participate in broader immunization services when they are permitted to do so by the appropriate authority.

The role of pharmacists in immunization exercises is further brought to the forefront when the ‘3 Cs’ of vaccine hesitancy identified by the World Health Organization are considered in the light of global COVID-19 vaccines hesitancy, especially in Africa25–27. Confidence, complacency and convenience are concepts that are easily resolved with the use of pharmacists, since majority of them serve as primary care providers, as proven by this study. In African countries, pharmacists are often contacted for healthcare services by the people, primarily because they may not need any form of booking for appointments. The continuous interactions over time confers the reputation of trust on the pharmacists, thus the opportunity to provide verified information about the vaccines, while dispelling commonly-held myths28. Provided the pharmacists are vaccinated, they would be in the right position to advise and vaccinate their clients with COVID-19 vaccines. As a statement by the American Pharmacists Association revealed, the confidence level of the pharmacists increased overtime with their gradual inclusion in COVID-19 vaccines29. This study thus believes that most African countries will attain a very good COVID-19 vaccination coverage if they involve their pharmacists. Pharmacists are already underutilized in COVID-19 response, considering their trainings30, despite their willingness to participate in public health activities including COVID-19 testing31. In Nigeria, the pharmacists that are most likely to be involved in immunization exercise are the community and hospitals pharmacists. They are already currently involved in a weekly clinical training exercise on an array of topics under the auspices of the newly-formed Clinical Pharmacists' Association of Nigeria (CPAN). By that singular practice, CPAN empowers them to be prepared for any clinical service, including the COVID-19 vaccination.

Policy Implications

The current study in a developing country provides a lot of information to governments, multinational health service funders and other policy makers on the rollout of the COVID-19 vaccines. Pharmacists play a lot of roles in the society, and with the findings that they would want to participate in the activities concerning the vaccinations, the appropriate authorities should carry them along.

Strengths and Limitations

No study in the literatures has documented the willingness of pharmacists to receive, recommend or administer COVID-19 vaccines to citizens in any country. Researchers have, however reported that pharmacists are willing to participate in any COVID-19 response activity that they are requested to perform. In a study conducted in Idaho, United States, Nguyen et al. observed that about 70% of the 229 pharmacists that responded to their study questions were willing to provide COVID-19 testing service to their community30. The pharmacists did mention in the study that possible motivators to their full involvement in the COVID-19 response were institution of reimbursement modalities, recruitment of sufficient manpower and organization of work schedule to accommodate their involvement. A systematic review by Lee et al. in reputable databases observed the underutilization of pharmacists in the COVID-19 response31. They concluded that pharmacists will have a lot of roles to play in the roll out of mass immunization against COVID-19.

This study was conducted using WhatsApp social media accounts and that assisted in obtaining the high response rate. The mode of data collection could, however, be a limitation, as some eligible respondents might have been offline at the time that the link to the questionnaire was shared. The use of WhatsApp also predisposed the study to the risk of having non-eligible persons accessing the study link due to the possibility of hacking of the WhatsApp contacts or use of the WhatsApp device with third parties. The limitation is common with online surveys, though the instrument of the present study had an opening remark that requested non-eligible persons not to respond to the questionnaire. In addition, at the time that the study was conducted, no COVID-19 vaccine was available in Nigeria: it is possible that their responses may be different if the reverse was the case. The timeframe of data collection was short, although it was done that way because of the urgency of the contribution that the study findings will have to policymakers in determining how the COVID-19 vaccines will be deployed. A long-time frame would also affect the response as the perceptions of people may change overtime in a pandemic. Also, using a short timeframe was a form of checkmating abuse of the link being shared to non-eligible persons. The study did not request the participants to indicate their states of residence, thus limiting the ability to determine their region of practice. Nonetheless, the collation of their areas of practice gives an idea that they practice in different regions of the country.

Conclusion

This study established that most pharmacists, irrespective of their practice settings are willing to accept to be vaccinated with the currently available COVID-19 vaccines. Majority of them expressed the readiness to recommend and administer the vaccines to their family members, friends, fellow healthcare professionals and clients who seek their advice. They were impressed by the effectiveness and cost of some of the vaccines, but were concerned about the possible adverse effects of the vaccines. The pharmacists would want the authorities to consider strategies that will make the vaccines accessible to all citizens.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Abubakar Sadiq Abdullahi, Ebere Mercy Oparah, Genevieve Ozoh and Puki Mohammed Dauda for their assistance in data collection.

Funding

The authors did not access any funds for this study.

References

- 1.Grech V, Cuschieri S. COVID-19: A global and continental overview of the second wave and its (relatively) attenuated case fatality ratio. Early Hum Dev [Internet] 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105211. [cited 2021 Feb 4]; Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7532352/?report=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization, author. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard [Internet] World Health Organization; 2021. [cited 2021 Feb 4]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/?gclid=EAIaIQobChMIvf6h_uPP7gIVme7tCh0kJAsNEAAYASAAEgILhfD_BwE. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuehn BM. Africa Succeeded against COVID-19's First Wave, but the Second Wave Brings New Challenges [Internet] JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. 2021;325:327–328. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.24288. American Medical Association; [cited 2021 Feb 4]. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization, author. Mythbusters [Internet] World Health Organization; 2020. [cited 2021 Feb 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public/myth-busters. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harvard University, author. Treatments for COVID-19 [Internet] Harvard University; 2021. [cited 2021 Feb 4]. Available from: https://www.health.harvard.edu/diseases-and-conditions/treatments-for-covid-19. [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, author. Guidelines for the implementation of non-pharmaceutical interventions against COVID-19 [Internet] European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; 2020. [cited 2021 Feb 4]. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/covid-19-guidelines-non-pharmaceutical-interventions. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Odusanya O, Odugbemi B, Odugbemi T, Ajisegiri W. COVID-19: A review of the effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions. Niger Postgrad Med J [Internet] 2020;27:261. doi: 10.4103/npmj.npmj_208_20. [cited 2021 Feb 4]; Available from: http://www.npmj.org/text.asp?2020/27/4/261/299904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization, author. Advice for the public [Internet] World Health Organization; 2021. [cited 2021 Feb 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public?gclid=EAIaIQobChMI2-TqhujP7gIVVODtCh19XA6GEAAYASAAEgJpffD_BwE. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, author. Benefits of Getting a COVID-19 Vaccine | CDC [Internet] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2021. [cited 2021 Feb 4]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/vaccine-benefits.html. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization, author. COVID-19 vaccines [Internet] World Health Organization; 2021. [cited 2021 Feb 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/covid-19-vaccines. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Prevention and Prevention, author. Different COVID-19 Vaccines [Internet] Centers for Disease Prevention and Prevention; 2021. [cited 2021 Feb 4]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/different-vaccines.html. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, author. COVID-19 Vaccine Rollout Recommendations [Internet] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2021. [cited 2021 Feb 4]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/recommendations.html. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelling SE. Exploring Accessibility of Community Pharmacy Services. Inov Pharm [Internet] 2015;6:210. [cited 2021 Feb 4]; Available from: http://pubs.lib.umn.edu/innovations/vol6/iss3/6 http://z.umn.edu/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsuyuki RT, Beahm NP, Okada H, Al Hamarneh YN. Canadian Pharmacists Journal. Vol. 151. SAGE Publications Ltd; 2018. Pharmacists as accessible primary health care providers: Review of the evidence [Internet] pp. 4–5. [cited 2021 Feb 4]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5755826/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Public Health Association, author. The Role of the Pharmacist in Public Health [Internet] American Public Health Association; 2006. [cited 2021 Feb 4]. Available from: https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2014/07/07/13/05/the-role-of-the-pharmacist-in-public-health. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nigeria Centre for Disease Control, author. NCDC Coronavirus COVID-19 Microsite [Internet] Nigeria Centre for Disease Control; 2021. [cited 2021 Feb 4]. Available from: https://covid19.ncdc.gov.ng/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martínez-Mardones F, Ahumada-Canale A, Gonzalez-Machuca L, Plaza-Plaza JC. Primary health care pharmacists and vision for community pharmacy and pharmacists in Chile. Pharm Pract (Granada) [Internet] 2020;18:1–7. doi: 10.18549/PharmPract.2020.3.2142. [cited 2021 Feb 28]; Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buss VH, Shield A, Kosari S, Naunton M. Journal of Pharmaceutical Policy and Practice. Vol. 11. BioMed Central Ltd.; 2018. The impact of clinical services provided by community pharmacies on the Australian healthcare system: A review of the literature [Internet] p. 22. [cited 2021 Feb 28]. Available from: https://joppp.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40545-018-0149-7. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hedima EW, Adeyemi MS, Ikunaiye NY. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. Vol. 17. Elsevier Inc.; 2021. Community Pharmacists: On the frontline of health service against COVID-19 in LMICs [Internet] pp. 1964–1966. [cited 2021 Feb 28]. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7162785/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edwards N, Gorman Corsten E, Kiberd M, Bowles S, Isenor J, Slayter K, et al. Pharmacists as immunizers: a survey of community pharmacists' willingness to administer adult immunizations. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37:292–295. doi: 10.1007/s11096-015-0073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacDougall D, Halperin BA, Isenor J, MacKinnon-Cameron D, Li L, McNeil SA, et al. Routine immunization of adults by pharmacists: Attitudes and beliefs of the Canadian public and health care providers. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2016;12:623–631. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1093714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hattingh HL, Sim TF, Parsons R, Czarniak P, Vickery A, Ayadurai S. Evaluation of the first pharmacist-administered vaccinations in Western Australia: a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011948. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oluwadamilola F. Vaccines , Vaccination and Therapeutics. 2016. Immunization services: Involvement of community pharmacies in Lagos State, Nigeria; p. 7560. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agbo BB, Esienumoh E, Inah SA, Eko JE, Nwachukwu EJ. COMMUNITY PHARMACISTS, PARTICIPATION IN IMMUNIZATION SERVICES IN CROSS RIVER STATE, NIGERIA. Int J Public Heal Pharm Pharmacol. 2019;4:11–25. [Google Scholar]

- 25.The Pharmaceutical Journal, author. How to address vaccine hesitancy [Internet] The Pharmaceutical Journal. 2021 [cited 2021 Apr 23]. Available from: https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/ld/how-to-address-vaccine-hesitancy. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lane S, MacDonald NE, Marti M, Dumolard L. Vaccine hesitancy around the globe: Analysis of three years of WHO/UNICEF Joint Reporting Form data-2015-2017. Vaccine. 2018;36:3861–3867. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Violette R, Pullagura GR. Canadian Pharmacists Journal. Vol. 152. SAGE Publications Ltd; 2019. Vaccine hesitancy: Moving practice beyond binary vaccination outcomes in community pharmacy; pp. 391–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terrie CY. The Role of the Pharmacist in Overcoming Vaccine Hesitancy [Internet] US Pharm. 2021:28–31. [cited 2021 Apr 23]. Available from: https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/the-role-of-the-pharmacist-in-overcoming-vaccine-hesitancy. [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Pharmacists Association, author. Pharmacists' Confidence in the COVID-19 Vaccines Continues to Grow [Internet] American Pharmacists Association; 2021. [cited 2021 Apr 23]. Available from: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/pharmacists-confidence-in-the-covid-19-vaccines-continues-to-grow-301265280.html. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nguyen E, Christopher, Owens T, Tayler Daniels, Boyle J, Robinson RF. Pharmacists' Willingness to Provide Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Services and the Needs to Support COVID-19 Testing, Management, and Prevention. J Community Health [Internet] 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00946-1. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee L, Peterson GM, Naunton M, Jackson S, Bushell M. Protecting the Herd: Why Pharmacists Matter in Mass Vaccination. Pharmacy. 2020;8:199. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy8040199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]