Abstract

Background

Preterm birth is a public health concern globally. In low- and middle-income countries, like Ethiopia, preterm birth is under reported and underestimated. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis assessed the pooled prevalence and associated risk factors for preterm birth in Ethiopia.

Methods

In this review the databases used were PubMed, Google scholar, EMBASE, HINARI and African journal online. Publication bias was checked using a funnel plot and Eggers test.

Results

A total of 30 studies were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis. The overall pooled prevalence of preterm birth in Ethiopia was 11.4% (95% CI; 9.04, 13.76). On pooled analysis, preterm birth was associated with pregnancy-induced hypertension being HIV-positive, premature rupture of membrane, rural residence, the mother having a history of abortion, multiple pregnancies, and anemia during pregnancy.

Conclusion

The national prevalence of preterm birth in Ethiopia was low. Early identifying those pregnant women who are at risk of the above determinants and proving quality healthcare and counsel them how to prevent preterm births, which decrease the rate of preterm birth and its consequences. So, both governmental and non-governmental health sectors work on the minimization of these risk factors.

Keywords: Prevalence, pre-term birth, determinants, systematic review, meta-analysis, Ethiopia

Background

According to WHO definition, preterm birth is a birth that occurs before 37 completed weeks of conception or fewer than 259 days from the first date of a woman's last menstrual period for singleton pregnancy. Based on gestational age, it is classified as extremely preterm (<28 weeks), very preterm (28 to < 32 wks.), and moderate to (32 to < 34 weeks) and late preterm (34 to 37 weeks). In other ways on the basis of birth weight, preterm can be classified as low birth weight (1500gm to <2500gm), very low birth weight (<1500 to 1000gm) and extremely very low birth (<1000gm). In addition, on the basis of initiation of labor preterm birth can be categorized into two spontaneous or induced. Spontaneous preterm birth occurs when a pregnant mother goes into labor without the use of drugs or techniques to induce labor before 37 weeks of gestation. Induced preterm birth is a delivery involving labor induction, where drugs or manual techniques are used to initiate the process of labor before 37 weeks of gestation for maternal and fetal indications1.

Globally, different studies reported that more than 15 million (11%) babies are estimated to be PTB each year and about 12 million (more than 81%) of these PTB occur in Sub-Sahara Africa and South Asia. Besides, the burden of Pre-term birth ranges between 5% and 18% in the world. In the lower and middle -income countries, on average, 12% of babies are born premature compared with 9% in higher-income countries2–4.

Studies conducted across the world identified risk factors associated with preterm birth, such as having a history preterm birth, short cervical length, smoking, chronic cough, Short inter-pregnancies interval, anemia, urinary tract infection, certain pregnancy-related complications (such as multiple-pregnancy, pregnancy-induced hypertension, vaginal bleeding, PROM, IUFD, IUGR, polyhydramnios, Oligohydramnious, congenital anomalies of the fetus), lack of antenatal care follow-ups, lifestyle factors (such as low pre-pregnancy weight, and substance use during pregnancy5–8.

Preterm babies can suffer lifelong effects such as cerebral palsy, mental retardation, visual and hearing impairments, poor health, and growth. Their developmental milestones are negatively affected. Preterm babies require prolonged hospital stay after delivery, repeated hospital admissions in the first year of life and increased risk of acute/chronic lung disease and putting their parents in social and financial problems1, 7.

Methods

Reporting

The report was written by using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)) guideline9.

Searching Strategy and Information sources

We have searched the following finding Items for this review (PRISMA) which was strictly followed by systematic review and meta-analysis guidelines. The databases used were PubMed, Google scholar, EMBASE, HINARI AJOL (African journal online). There were no restriction articles based on publication period. Searching engines were based on adapted PICO principles to search through the above-listed databases to access all the essential articles. To conduct a search of the literature databases, we have used Boolean logic, connectors “OR,” “AND” in combinations10. The search strategy for the PubMed database was done as following: Magnitude of preterm birth “OR” prevalence of preterm birth” OR” determinants of preterm birth” OR “ risk factors of preterm birth “OR “magnitude of premature birth “OR “prevalence of premature birth”(MeSH terms) AND birth “OR” parturition “OR” newborn (MeSH terms) “OR” infant AND Ethiopia AND “April 2009(PDat)-April 2020(PDat)”, stated below (Table 1)

Table 1.

Search for MEDLINE/PubMed and Google Scholar databases to assess preterm birth in Ethiopia

| Databases | Searching terms | Number of studies |

| MEDLINE/PubMed | “preterm birth” OR “premature birth” AND “determinants” OR “predictors” OR “risk factors” OR “associated factors” |

303 |

| Google scholar | “preterm birth” or “premature birth” and “determinants” or “associated factors” or risk factors” and “Ethiopia” |

30 |

| From other databases | From hand searching using back and front searching and EMBASE |

207 |

| Total retrieved articles | 540 | |

| Number of included studies | 30 |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Cross-sectional, cohort, and case-control studies were included. Articles included in this review were reported the prevalence, or magnitude and associated factors, or determining factors among mothers who were giving birth. Articles were included that were published only in English language literature, published from 2009–2020. Articles without full text and inaccessibility of abstract, commentaries, letters, duplicated studies, anonymous reports, and editorials were excluded.

Data extraction and Risk of bias

Findings from all databases were exported to Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Two reviewers (FW, GG) independently extracted the data and reviewed the screened articles. Differences were recon reviewers (FY, SA &AA). Finally, the consensus was reached through a discussion between reviewers. Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) for cross-sectional, cohort, and case-control studies were used to assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the extent to which a study addressed the possibility of bias in its design, conduct, and analysis. All reviewers independently assessed the articles which were included in the review. The average mean score for the cross-sectional studies was 8.91 out of 11, for case-control studies 10.66 out of 22 and Cohort study 14 out of 22. No study that scored below the cutoff point was excluded from the review. All of the included articles scored (NOS) 7 and more can be considered a “good” study and have a low risk of bias for cross-sectional studies and 9 or more scores for case-control and cohort chosen to indicate a high standard for comparative observational studies, stated (S1 Table given below, S2 Table and S3 Table). The last search date was Aprl 15,2020.

Data collection process

Two independent reviewers (FW, GG) extracted data by using structured data extraction form. The name of the first author, year of study, year of publication, study of region, study area, study design, sample size, the prevalence rate, determinants of preterm birth, and AOR (95% CI) were extracted.

Outcome of measurement

The measurement outcome of this study had two main outcome variables. The prevalence of preterm birth was the primary outcome of the study, whereas associated factors/determinant for preterm birth were the second outcome variable. The odds ratio was calculated for the common factors of the reported studies. The most common associated factors included in this systematic review and meta-analysis were pregnancy-induced hypertension, being HIV-positive, premature rupture of membrane, rural residence, mother having a history of abortion, anemia during pregnancy and multiple pregnancy.

Publication bias and heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was checked using I2 and its corresponding p-value. A value of 25%, 50%, and 75% was used to state the heterogeneity test as low, moderate and marked heterogeneity, respectively11. The random effect model of analysis was used with the evidence of heterogeneity. Funnel plot and Egger regression test was used to check the existence of publication bias. Sub-group analysis, trim fill and sensitivity analysis were employed to select the most influential risk factors and avoid evidence of publication bias.

Data analysis

Stata 11 software with forest plots were used to report the estimated pooled prevalence and determinants of each study with the 95% confidence interval (CI). We have conducted subgroup analysis by sample size of participants and year of publication of study due to marked heterogeneity I2 =96.3%. We have also conducted Trim fill and sensitivity analysis to see the effects of a single study on the prevalence of preterm birth. Finally, the odds ratio with 95% CI of pregnancy induced hypertension, being HIV-positive, premature rupture of membrane, rural residence, mother having a history of abortion, anemia during pregnancy and multiple pregnancy were computed.

Results

Description of eligible studies

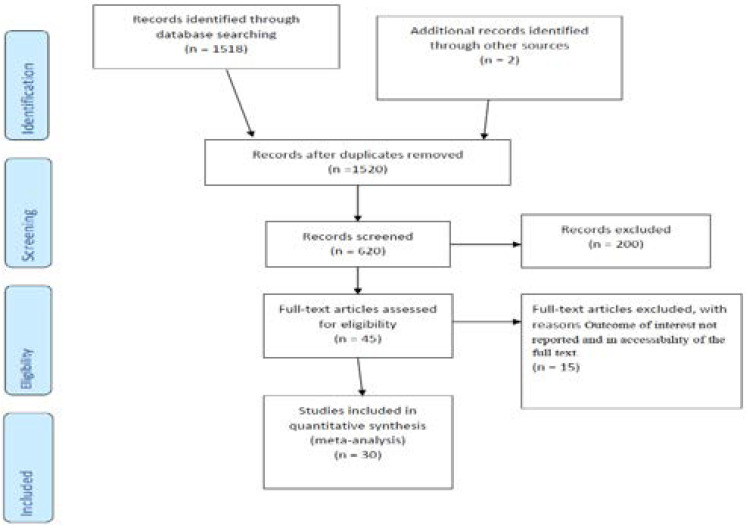

A total of 540 articles were retrieved related to preterm birth through electronic searches. Of those retrieved, 303 papers were from PubMed/MIDLINE, 30 from Google scholars, and 207 from other sources. From the total papers, 88 duplicate and 400 non-eligible papers were identified and excluded during the screening of the titles and abstracts. The remaining 42 articles were given full test review, resulting in 30 papers being considered appropriate and eligible for analysis. Twelve articles were excluded based on the exclusion criteria stated below (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection for systematic review and meta-analysis of preterm birth in Ethiopia.

Characteristics of the included studies

As a result, 30 studies were met the inclusion criteria to undergo the final systematic review and Meta-analysis. This systematic review and Meta-analysis consist of 23 cross-sectional, 6 case-control and 1 cohort studies with total 17,403 study participants in different regions in Ethiopia (Table 2).

Table 2.

Study characteristics included in the systematic review and meta-analysis in Ethiopia (n = 30)

| Authors | Year of study |

Region | Study Design | Sample size | Quality status |

| Abebe T et al. (35) | 2016 | Addis Ababa | Cross-sectional | 384 | Low risk |

| Abebayehu M et al. (36) | 2018 | Amhara | case-control | 405 | Low risk |

| Muluken D et al. (37) | 2017 | Amhara | case-control | 417 | Low risk |

| Gebrekiros A et al. (38) | 2018 | Tigray | Cross-sectional | 472 | Low risk |

| Dawit G et al (39) | 2016 | Amhara | Cross-sectional | 548 | Low risk |

| Demelash W et al(40) | 2017 | Oromia | Cross-sectional | 325 | Low risk |

| Kahsay G et al(41) | 2016 | Amhara | Cross-sectional | 540 | Low risk |

| Bekele I et al(42) | 2015 | Oromia | Cross-sectional | 220 | Low risk |

| Hayelom G et al(43) | 2014 | Tigray | Cohort | 1152 | Low risk |

| Bayew K et al(44) | 2018 | Tigray | Cross-sectional | 325 | Low risk |

| Tesfaye B et al(45) | 2018 | Tigray | Cross-sectional | 413 | Low risk |

| Girmay T et al(46) | 2017/2018 | Tigray | case-control | 264 | Low risk |

| Samuel D et al(47) | 2018 | SNNPR | case-control | 280 | Low risk |

| Melkamu B et al(48) | 2014–2016 | Oromia | Cross-sectional | 1400 | Low risk |

| Sheka Shemisi et al(49) | 2017 | 0romia | case-control | 656 | Low risk |

| Tigist B et al(50) | 2013 | Amhara | Cross-sectional | 422 | Low risk |

| Ayenew E et al(51) | 2018 | Amhara | Cross-sectional | 325 | Low risk |

| Akilew A et al(52) | 2013 | Amhara | Cross-sectional | 481 | Low risk |

| Abdo et al(53) | 2015 | SNNPR | Cross-sectional | 327 | Low risk |

| Abera H et al(54) | 2015–2016 | Tigray | Cross-sectional | 425 | Low risk |

| Cherie N et al (55) | 2017 | Amhara | Cross-sectional | 462 | Low risk |

| Tsegaye and Kassa(56) | 2017 | SNNPR | Cross-sectional | 589 | Low risk |

| Abdo RA et al(57) | 2019 | SNNPR | Cross-sectional | 313 | Low risk |

| Abebe E et al(58) | 2012–2013 | Amhara | Cross-sectional | 3003 | Low risk |

| Tsegaye L et al (59) | 2017 | SNNPR | Cross-sectional | 718 | Low risk |

| Getachew M et al(60) | 2018 | Amhara | Cross-sectional | 1134 | Low risk |

| Eshete A et al(61) | 2009 | Amhara | Cross-sectional | 295 | Low risk |

| Hailemariam Workie(62) | 2015 | Tigray | case-control | 340 | Low risk |

| Eskeziaw A et al(63) | 2017 | Amhara | Cross-sectional | 462 | Low risk |

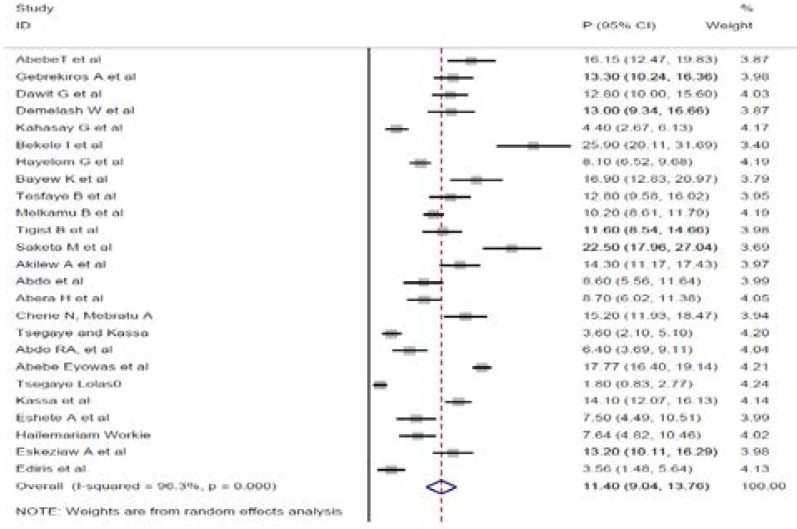

Prevalence of preterm birth among mothers who gave birth at health institutions in Ethiopia

The overall pooled prevalence of preterm birth in Ethiopia is presented with a forest plot (Fig. 2). Therefore, the pooled estimated prevalence of preterm birth in Ethiopia was 11.4% (95% CI; 9.04, 13.76; I2=96.3%, P≤0.001).

Figure 2.

Forest funnel plot of the pooled prevalence of preterm birth in Ethiopia

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis was done with the evidence of heterogeneity. Hence, the Cochrane I2 statistic =96.3%, P≤0.001) with evidence of marked heterogeneity. Therefore, subgroup analysis was conducted using the sample size of participants and year of publication of the articles. Based on the subgroup analysis, the prevalence of preterm birth in Ethiopia was 10.73% (95%CI: 7.67,13.79) I2=97.3%, P≤0.001) in which sample size was≥400 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Subgroup pooled prevalence of preterm birth among mothers who gave birth at health institutions in Ethiopia (n= 25)

| Variables | Subgroup | No of studies | Prevalence% (95%CI) | I2 (%) | P-value |

| Sample size | ≥400 | 15 | 10.73(7.67,13.79) | 97.3 | ≤0.001 |

| <400 | 10 | 12.48(8.56,16.40) | 93.1 | ≤0.001 | |

| Year of publication | 2014–2018 | 16 | 10.98(8.12,13.85) | 95.7) | ≤0.001 |

| ≥2019 | 9 | 12.15(7.74,16.57) | 97.2 | ≤0.001 |

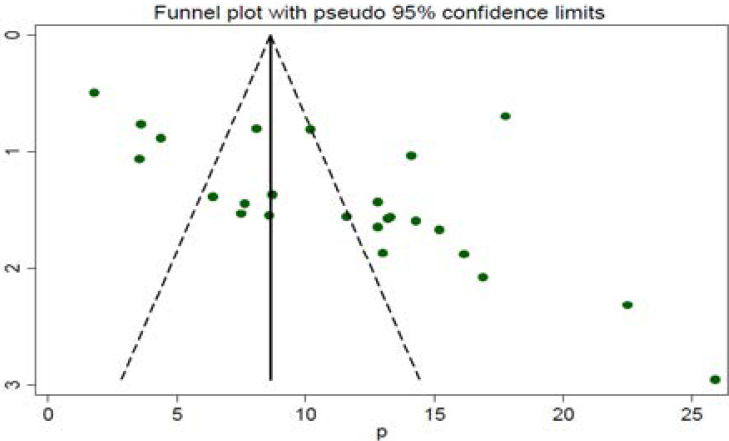

Publication bias

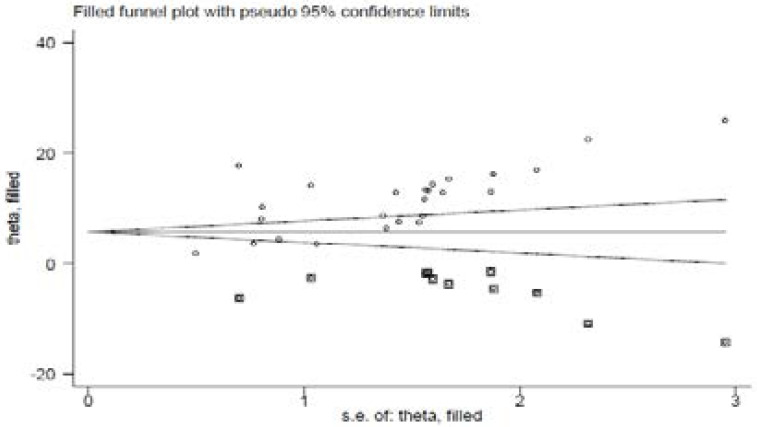

A funnel plot was assessed for the asymmetry distribution of preterm birth among mothers who gave birth at health institutions in Ethiopia by visual inspection. Egger's regression test showed with a p-value of 0.003 indicated for the existence of publication bias. Hence, trim and fill analysis was conducted to overcome the publication bias. Eleven studies filled with 25 studies and overall, 36 studies were enrolled and computed through the trim and fill analysis with a pooled prevalence of 6.52% (95% CI; 3.97–9.07) using a random effect model (Fig. 3 a & b).

Figure 3.

Funnel plot of publication bias a (before an adjustment

Figure 3b.

(after trim-fill analysis was computed)

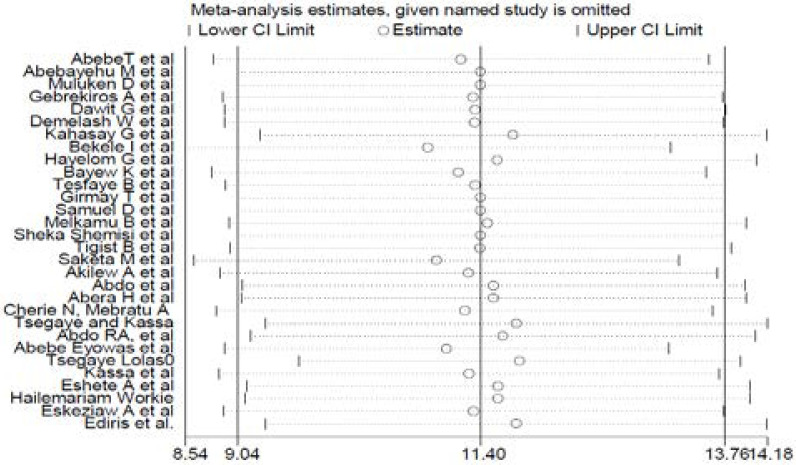

Sensitivity analysis

This review showed that the point estimate of its omitted analysis lies under the confidence interval of the combined analysis (Fig 4).

Figure 4.

Sensitivity analysis of the pooled prevalence of preterm birth in Ethiopia

Risk factors associated with preterm birth among mothers who gave birth at health institutions in Ethiopia

The most common associated factors included in this systematic review and meta-analysis were pregnancy-induced hypertension, being HIV-positive, premature rupture of membrane, rural residence, mother having a history of abortion, multiple pregnancy, and anemia during pregnancy.

Women who have pregnancy-induced hypertension (AOR: 5.11, 95%CI: 3.73, 7.01)) was positively associated with preterm birth. No heterogeneity (I2=0.0%; p-value=0.872) was detected among the included studies; due this reason, the fixed effect model was calculated. Moreover, the possibility of publication bias was not detected using Egger's tests with a p-value of 0.568.

Women who is HIV-positive were the predictors of preterm birth (AOR: 4.74; 95%CI: 2.79, 8.05). No heterogeneity (I2=0.0%; p-value=0.629) was detected among the included studies; for this reason, the fixed effect meta-analysis model was computed. Moreover, no possibility of publication bias was detected using Egger's tests with a p-value of 0.595.

We found that women who had premature rupture of membrane four times (AOR: 5.36, 95%CI: 3.76, 7.64)) greater at increased risk the likelihood of having a preterm birth compared to their counterparts. Moderate heterogeneity (I2=56.8%; p-value=0.031) was detected among the studies. Therefore, random effect model meta-analysis was employed. Furthermore, no possibility of publication bias was detected using Egger's tests with a p-value of 0.762.

Being a rural residency was one the significant risk factor for preterm birth (AOR: 2.35, 95%CI: 1.56, 3.55). No heterogeneity (I2=0.0%; p-value=0.839) was detected among the included studies; for this reason, the Fixed effect meta-analysis model was computed. Moreover, no existence of publication bias was declared d using the Egger's tests with a p-value of 0.314.

Pregnant women who were anemic (AOR: 3.41, 95%CI: 2.1, 5.56)) were positively associated with preterm birth. Low heterogeneity (I2=26.9%; p-value=0.251) was detected among the included studies; for this reason, the random effect meta-analysis model was computed. Furthermore, publication bias was not detected using Egger's tests with a p-value of 0.657.

Pregnant women who have two or more fetus in intrauterine (AOR: 3.60 95%CI:2.49, 5.19) were positively associated with preterm birth. No heterogeneity (I2=0.0%; p-value=0.429) was detected among the included studies; for this reason, the fixed effect meta-analysis model was computed. Furthermore, publication bias was not detected using Egger's tests with a p-value of 0.835.

Women having a history of abortion (AOR: 2.92, 95%CI: 1.91, 4.47) were the determining factor of preterm birth. No heterogeneity (I2=0.0%; p-value=0.726) was detected. Hence, the fixed effect meta-analysis model was computed. Furthermore, the existence of publication bias was not detected using Egger's tests with a p-value of 0.835 (Table. 4).

Table 4.

Summary of associated risk factors with preterm birth in Ethiopia

| Variables | Model | Egger test (P-value) |

Status of heterogeneity | AOR (95%CI) | I2 (%) | P-value |

| PIH | Fixed | 0.568 | No heterogeneity | 5.11(3.73, 7.01) | 0.0 | 0.872 |

| HIV-Positive | Fixed | 0.595 | No heterogeneity | 4.74(2.79, 8.05) | 0.0 | 0.629 |

| PROM | Random | 0.762 | Moderate heterogeneity | 5.36(3.76, 7.64) | 56.8 | 0.031 |

| Rural residence |

Fixed | 0.314 | No heterogeneity | 2.35(1.56, 3.55) | 0.0 | 0.839 |

| Hx of abortion |

Fixed | 0.835 | No heterogeneity | 2.92(1.91, 4.47) | 0.0 | 0.726 |

| Multiple pregnancy |

Fixed | 0.835 | No heterogeneity | 3.60(2.49, 5.19) | 0.0 | 0.429 |

| Anemia during pregnancy |

Random | 0.657 | Low heterogeneity | 3.41(2.1, 5.56) | 26.9 | 0.251 |

Discussion

In this meta-analysis, the overall pooled prevalence of preterm birth among mothers who gave birth at health institutions in Ethiopia was 11.4% (95% CI; 9.04,13.76). This finding agrees with studies conducted in Tanzania 13% 12, India 12.95% 13 and Brazil 13.7% 14. The possible explanation might be due to all the above countries might be implementing the recommendation of comprehensive health-care system for pregnant women.

The finding of this review and meta-analysis was lower than the study done in India 15% 15, Brazil 21.7% 16, Kenya 18.3% 8 and 20.2% 8, India 28.25% 17 and Nigeria 24% 18. This difference could be due to in our country setting having lower risk factors for preterm birth as compared to those countries. For example, in Nigeria, there is the highest rate of multiple gestations. Multiple gestation causes over distended uterus, and can precipitate to preterm birth, and multiple gestations are a known predisposing factor for preterm birth.

The finding of this review was higher than the studies conducted in Kenya 8.3%, two different studies in Iran 6.3% 19 and 8.4% 20 and the United Arab Emires 6.3%21. The possible justification might be due to our country setting having higher risk factors and having lower quality care for pregnant mother during pregnancy, even though there is identified known risk factors for preterm birth as compared to those countries.

The study determined that women who had developed pregnancy-induced hypertension were 5.11-time (AOR: 5.11, 95%CI: 3.73, 7.01)) greater risk with preterm birth than the counterpart. The finding is consistent with the study done in East Africa 22, China23, India 17, Kenya (24), Nigeria 25, Brazil 26, and two different studies in Iran 19,20. The possible explanation might be due to the existing scientific evidence which speculates that Pregnancy induced hypertension is linked to vascular and placental damage, which in turn reduces placental blood flow and leads to uteroplacental insufficiency resulting in obstetric emergencies that require termination of pregnancy as a lifesaving for both the mother and fetus. Abruptio placenta is another complication of pregnancy-induced hypertension that may require termination of pregnancies 27.

This review showed that HIV-positive pregnant mothers were 4.7 times (AOR: 4.74, 95%CI: 2.79, 8.05) more at increased risk of having a preterm birth than negative mothers. This is in agreement with a study conducted in South Africa 28 and Tanzania 29. It could be explained by the effect of ART drugs and have low immunity status of the mother at greater risk for preterm birth.

We found that women who had premature rupture of membrane four times (AOR: 5.36, 95%CI: 3.76, 7.64)) greater at increased risk the likelihood of having preterm birth as compared to their counterparts. This is in agreement with a study done in two different studies in Iran 19,20. Kenya24, Nigeria 25 and India 17. This might be due to the fact that endogenous prostaglandins released after ruptured membrane that initiates the uterine contraction, thereby cause preterm birth.

Pregnant women who are living in rural areas 2.4 times (AOR: 2.35, 95%CI: 1.56, 3.55) more at increased risk for preterm birth than in urban areas, which is consistent with a study conducted in Kenya8. This is the fact that pregnant women who are living in rural areas suffer from different risk conditions like face-unbalanced diet, walk a long distance for fulfilling their family's needs, do extraneous work, and have poor access health care system, thereby distance from health facility that might contribute to preterm birth.

Pregnant women who were anemic (AOR: 3.41, 95%CI: 2.1, 5.56)) were positively associated with preterm birth. This is in agreement a study done in India 17, Malawi 30, China 31 and East Africa 22. This is because of the biological mechanisms of anemia, iron deficiency or both could cause preterm delivery. In fact, anemia and iron deficiency can induce stress and maternal infections, which in turn stimulate the synthesis of Corticotrophin-Releasing Hormone (CRH) that elevated CRH concentrations to be a known risk factor for preterm birth 32.

This review showed that multiple gestation has been associated with the increased likelihood of preterm birth (AOR: 3.60 95%CI:2.49, 5.19). This finding agrees with those studies done in Kenya 8, India 17, Iran 20. This might be due to multiple gestation is associated with uterine over-distension, which causes increased gap junction of myometrial muscles and induce the oxytocin receptors. Finally, it can initiate uterine contraction that is resulting preterm birth 33.

Another risk factor associated with preterm birth had a history of abortion (AOR: 2.92, 95%CI: 1.91, 4.47)), which is consistent those studies done in Brazil 34, Iran17 and Tanzania 12. This is because during surgical evacuation of the uterus mechanically stretches the cervix could cause cervical incompetency, which in turn predispose preterm birth for subsequent pregnancies.

Strength

This review seems to be done first in Ethiopia. In addition, the included studies in this review were cross-sectional, case-control, and cohort show temporal cause effect relationships due to its nature of the design.

Limitation

This review has been limited to articles published only in English languages that cause reporting bias. Data were not found in all regions of the country this can cause representative problems.

Conclusion

The national prevalence of preterm birth in Ethiopia was low. The most common associated factors included in this systematic review and meta-analysis were pregnancy-induced hypertension, being HIV-positive, premature rupture of membrane, rural residence, the mother having a history of abortion, multiple pregnancy, and anemia during pregnancy. This review can be used to base line for health policy makers, clinicians, and program officers to design action plan work for prevention and intervention measures on preterm birth. Early identifying those pregnant women who are at risk of the above determinants and proving quality healthcare and counsel them how to prevent preterm birth which may decrease the rate of preterm birth and its consequences.

Acknowledgment

Not applicable

Abbreviations

AOR-Adjusted Odd Ratio, ART-Anti-Retroviral Therapy, CI- Confidence interval, HIV-Human Immuno Deficiency Virus, PIH-Pregnancy Induced Hypertension, PROMPremature Rupture of membrane.

Declarations

Authors' contribution

FW, GG, and FY participated in the design, selection of articles, and data extraction. FW, SA and GG involved in statistical analysis. FW, SA and AA participated in writing the manuscript and all authors critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the paper.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Availability of data and materials

All related data have been presented within the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.WHO. World Health Organization (WHO), author International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. Geneva: WHO; 2015. [25 Oct 2015]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/Volume-1-2005.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chawanpaiboon JPV S, Moller A-B, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth. The Lancet Global Health. 2014;7(1):37–46. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30451-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stay DW LS, Ana PB, Mario M, Jennifer HR, Craig R, et al. The worldwide incidence of preterm birth: a systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity. Vol. 88. World Health Organization; 2010. pp. 31–38. PubMed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hannah JL HB, Catherine YS, Christopher PH, Sarah CS, Eve ML, et al. Preventing preterm births: analysis of trends and potential reductions with interventions in 39 countries with very high human development index. Lancet. 2013;381(223) doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61856-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(ACOG) ACoOaG, author. Definitions of Preterm (Premature) Labor and Birth. 2016. Available from: https://wwwacogorg/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Obstetric-Practice/Definition-of-Term-Pregnancy.

- 6.BelaYnew W, TA GG, Mohamed K. Effects of inter pregnancy interval on pre term birth and associated factors among post-partum mothers who gave birth at felegehiowt referral hospital. World Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2015;4(4):12–25. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joshua P, Vogel SC, Moller Ann-Beth, Watananirun Kanokwaroon, Bonet Mercedes, Lumbiganon Pisake. The global epidemiology of preterm birth. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2018;04(3):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peter Wagura AW, Laving Ahmed, Wamalwa Dalton, Ng'ang'a Paul. Prevalence and factors associated with preterm birth at kenyatta national hospital, Kenya. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2018;18(1):107. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1740-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D LA, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group TP Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuttle BD IM, Schardt C, Powers A. PubMed instruction for medical students: searching for a better way. Med Ref Serv Q. 2009;28(3):11. doi: 10.1080/02763860903069839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ioannidis J PN, Evangelou E. Uncertainty in heterogeneity estimates meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007;335(10):914–918. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39343.408449.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Temu GM T B, Obure J, Mosha D, Mahande M J. Maternal and obstetric risk factors associated with preterm delivery at a referral hospital in northern-eastern Tanzania. Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction. 2016;5(5):365–370. [Google Scholar]

- 13.TB Preterm Delivery Associated Risk Factor and its Incidence IOSR. Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences. 2018;17(1):51–55. Mahaseth BK PSM, Prof. Das CR, Malla. [Google Scholar]

- 14.al MFe, author. Determinants of preterm birth:pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil, cohort. Cadernos de saude Publica. 2009;26(1):185–194. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2010000100019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shubhada A KS, Phalke BD. Determinants of Preterm Labor in a Rural Medical College Hospital in Western Maharashtra. Nepal J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;8(1):31–33. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miranda A PV, Szwarcwald C, Golub E. Prevalence and correlates of preterm labor among young parturient women attending public hospitals in Brazil. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública. 2012;32(5):330–334. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892012001100002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nandini Kuppusamy AV. Prevalence of Preterm Admissions and the Risk Factors of Preterm Labor in Rural Medical College Hospital, India. International Journal of Scientific Study. 2016;4(9):125–128. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kunle Olowu OE PO, Adeyemi O. Prevalence and outcome of preterm admissions at the Neonatal Unit of a Tertiary Health Center in Southern Nigeria. Open J Pediatr. 2014;4(1):67–75. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Najmeh Tehranian MRM, PhD, Fatemeh Shobeiri., PhD The Prevalence Rate and Risk Factors for Preterm Delivery in Tehran, Iran. J Midwifery Reprod Health. 2016;4(2):600–660. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohsenzadeh Azam, (MD) SSM, Karimi Atusa., (MD) Prevalence of Preterm Neonates and Risk Factors, Iran. Iranian journal of Neonatology. 2011;2(2):38–42. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taha AAH Zainab, Wikkeling-Scott Ludmilla, Papandreou Dimitrios. Factors Associated with Preterm Birth and Low Birth Weight in Abu Dhabi, the United Arab Emirates. International Journal of Enviromental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(4):1382. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17041382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laelago TY Tariku, Tsige Gulima. Determinants of preterm birth among mothers who gave birth in East Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis. Italian Journal of Pediatrics. 2020;46(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s13052-020-0772-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang YZ J, Ni Z, et al. Risk factors for low birth weight and preterm birth: a population-based case-control study in Wuhan, China. Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology. 2017;37(2):286–292. doi: 10.1007/s11596-017-1729-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okube LMS OT. Determinants of preterm birth at the postnatal ward of Kenyatta national hospital, Nairobi, Kenya. Open Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2017;7(9):973. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butali CE A, Ekhaguere O, et al. Characteristics and risk factors of preterm births in a tertiary center in Lagos Nigeria. Pan African Medical Journal. 2016;24(1):1. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2016.24.1.8382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silveira CGV M F, Barros A J D, Santos I S, et al. Determinants of preterm birth: Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil. Public Health Notebooks. 2010;26(1):185–194. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2010000100019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sivakumar S VBB, Badhe BA. Effect of Pregnancy Induced Hypertension on Mothers and Their Babies. Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2007;74(6):623–625. doi: 10.1007/s12098-007-0110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naidooa M SB, Tshimanga-Tshikalaa G. Maternal HIV infection and preterm delivery outcomes at an urban district hospital in KwaZulu-Natal South Africa. Journal of Infecious Disease. 2016;31(1):4. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zack RM GJ, Aboud S, Msamanga G, Spiegelman D, Fawzi W. Risk Factors for Preterm Birth among HIV-Infected Tanzanian Women: A Prospective Study. Hindawi Publishing Corporation; 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van den Broek RJ-B N R, Neilson J P. Factors associated with preterm, early preterm and late preterm birth in Malawi. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e90128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang CVA Q, Li Z, Smulian J C. Maternal anaemia and preterm birth: a prospective cohort study, East China. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;38(5):1380–1389. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allen LH. Biological mechanisms that might underlie iron's effects on fetal growth and preterm birth. The Journal of Nutrition. 2001;131(2):581–589. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.2.581S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buxton IL SC, Tichenor JN. Expression of stretch-activated twopore potassium channels in human myometrium in pregnancy and labor. PLoS One. 2010;5(8):e12372. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Passini Jr JGC R, Lajos G J, et al. Brazilian multicentre study on preterm birth (EMIP): prevalence and factors associated with spontaneous preterm birth. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e109069. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deressa AT, Cherie A, Belihu TM, Tasisa GG. Factors associated with spontaneous preterm birth in Addis Ababa public hospitals, Ethiopia: cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2018;18(1):332. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1957-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mekuriyaw AM, Mihret MS, Yismaw AE. Determinants of Preterm Birth among Women Who Gave Birth in Amhara Region Referral Hospitals, Northern Ethiopia, 2018: Institutional Based Case Control Study. International Journal of Pediatrics. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/1854073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woday A, Muluneh MD, Sherif S. Determinants of preterm birth among mothers who gave birth at public hospitals in the Amhara region, Ethiopia: A case-control study. PLoS One. 2019;14(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aregawi G, Assefa N, Mesfin F, Tekulu F, Adhena T, Mulugeta M, et al. Preterm births and associated factors among mothers who gave birth in Axum and Adwa Town public hospitals, Northern Ethiopia, 2018. BMC Research Notes. 2019;12(1):640. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4650-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mekonen DG, Yismaw AE, Nigussie TS, Ambaw WM. Proportion of Preterm birth and associated factors among mothers who gave birth in Debretabor town health institutions, northwest, Ethiopia. BMC Research Notes. 2019;12(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-4037-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woldeyohannes D, Kene C, Gomora D, Seyoum K, Assefa T. Factors Associated with Preterm Birth among Mothers Who gave Birth in Dodola Town Hospitals, Southeast Ethiopia: Institutional Based Cross Sectional Study. Clinics Mother Child Health. 2019;16(317):2. [Google Scholar]

- 41.K G, author. Preterm Birth and Associated Factors among Mothers Who Gave Birth in Gondar Town Health Institutions Advances in Nursing. Hindawi Publishing coorporation; 2016. 2016(2016) [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bekele I, Demeke T, Dugna K. Prevalence of preterm birth and its associated factors among mothers delivered in Jimma university specialized teaching and referral hospital, Jimma Zone, Oromia Regional State, South West Ethiopia. J Women's Health Care. 2017;6:356. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gebrekirstos Mengesha WTL Hayelom, Kidanemariam Abadi, Gebrezgiabher4 Gebremedhin, Berhane Yemane. Pre-term and post-term births: predictors and implications on neonatal mortality in Northern Ethiopia. BMC Nursing. 2016;15(1):48. doi: 10.1186/s12912-016-0170-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kelkay B, Omer A, Teferi Y, Moges Y. Factors associated with singleton preterm birth in Shire Suhul general hospital, Northern Ethiopia, 2018. Journal of Pregnancy. 2019;2019:9. doi: 10.1155/2019/4629101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berhe HGaHD Tesfay. Determinants of preterm birth among mothers delivered in Central Zone Hospitals, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. BMC Research Notes. 2019;12:266. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4307-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Teklay G, Teshale T, Tasew H, Mariye T, Berihu H, Zeru T. Risk factors of preterm birth among mothers who gave birth in public hospitals of central zone, Tigray, Ethiopia: unmatched case-control study 2017/2018. BMC Research Notes. 2018;11(1):571. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3693-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dessu Sifer BSK Samuel, Alemu Demisse Getu, Sisay Yordanos. Determinants of preterm birth in neonatal intensive care units at public hospitals in Sidama zone, South East Ethiopia; case control study. Journal of Pediatrics and Neonatal Care. 2019;9(6):180–186. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berhane NW Melkamu, Girma1 Tsinuel, Lim Ruth, Lee Katherine J, Nguyen Cattram D, Neal Eleanor, Russell Fiona M. Prevalence of Low Birth Weight and Prematurity and Associated Factors in Neonates in Ethiopia: Results from a Hospital-based Observational Study. Ethiopain Journal of Health Science. 29(6):677–680. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v29i6.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abaraya SSS Mohammed, Amme Ibro Shemsedin. Determinants of preterm birth at Jimma University Medical Center, southwest Ethiopia. Pediatric Health, Medicine, and Therapeutics. 9:101–107. doi: 10.2147/PHMT.S174789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bekele T, Amanon A, Gebreslasie K. Preterm birth and associated factors among mothers who gave birth in Debremarkos Town Health Institutions, 2013 institutional based cross sectional study. Gynecol Obstet. 2015;5(5):292–297. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yismaw AE, Tarekegn AA. Proportion and factors of death among preterm neonates admitted in University of Gondar comprehensive specialized hospital neonatal intensive care unit, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Research Notes. 2018;11(1):867. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3970-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Adane AA, Ayele TA, Ararsa LG, Bitew BD, Zeleke BM. Adverse birth outcomes among deliveries at Gondar University hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2014;14(1):90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abdo R, Endalemaw T, Tesso F. Prevalence and associated factors of adverse birth outcomes among women attended maternity ward at Negest Elene Mohammed Memorial General Hospital in Hosanna Town, SNNPR, Ethiopia. J Women's Health Care. 2016;5(4) [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adhena T, Haftu A, Gebre G, Dimtsu B. Assessment of magnitude and associated factors of adverse birth outcomes among deliveries at Suhul Hospital Shire Tigray, Ethiopia from September, 2015 to February, 2016. Res Rev J Med Sci Technol. 2017;6(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cherie N, Mebratu A. Adverse birth out comes and associated factors among delivered mothers in Dessie Referral Hospital, North East Ethiopia. J Women's Health Reprod Med. 2017;1(1):4. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tsegaye B, Kassa A. Prevalence of adverse birth outcome and associated factors among women who delivered in Hawassa town governmental health institutions, south Ethiopia, in 2017. Reproductive Health. 2018;15(1):193. doi: 10.1186/s12978-018-0631-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abdo R, Halil H, Kebede B. Prevalence and Predictors of Adverse Birth Outcome among Deliveries at Butajira General Hospital, Gurage Zone, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People's Region, Ethiopia. J Women's Health Care. 2019;8(474) 2167-0420.19. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eyowas FA, Negasi AK, Aynalem GE, Worku AG. Adverse birth outcome: a comparative analysis between cesarean section and vaginal delivery at Felegehiwot Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: a retrospective record review. Pediatric Health, Medicine and Therapeutics. 2016;7:65. doi: 10.2147/PHMT.S102619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lolaso T, Oljira L, Dessie Y, Gebremedhin M, Wakgari N. Adverse Birth Outcome and Associated Factors among Newborns Delivered In Public Health Institutions, Southern Ethiopia. East African Journal of Health and Biomedical Sciences. 2019;3(2):35–44. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mullu Kassa AOA Getachew, Odukogbe A A, Yalew Alemayehu Worku. Adverse neonatal outcomes of adolescent pregnancy in Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):1–20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eshete A, Birhanu D, Wassie B. Birth outcomes among laboring mothers in selected health facilities of north Wollo zone, Northeast Ethiopia: a facility based cross-sectional study. Health. 2013;5(7):1141–1150. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Workie H. Adverse neonatal outcomes and associated risk factors in public and private hospitals of Mekelle city, Tigray, Ethiopia: Unmatched case-control study. Journal of Pediatrics & Therapeutics. 2018;8(5):39–46. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Abebe Kassahun HDMaMAG Eskeziaw. Adverse birth outcomes and its associated factors among women who delivered in North Wollo zone, northeast Ethiopia: a facility based cross-sectional study. BMC Research Notes. 2019;12(3):357. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4387-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All related data have been presented within the manuscript.